Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Animals and Diets

2.4. Glycemia and Serum and Tissue Free Fatty Acid (FFA) and Triglyceride (TG) Levels

2.5. ELISAs

2.5.1. Adiponectin, Insulin and Leptin

2.5.2. High Molecular Weight (HMW)-Adiponectin

2.5.3. Phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor

2.6. Tissue Homogenization and Protein Quantification

2.7. Western Blotting

2.8. Multiplexed Bead Immunoassays

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

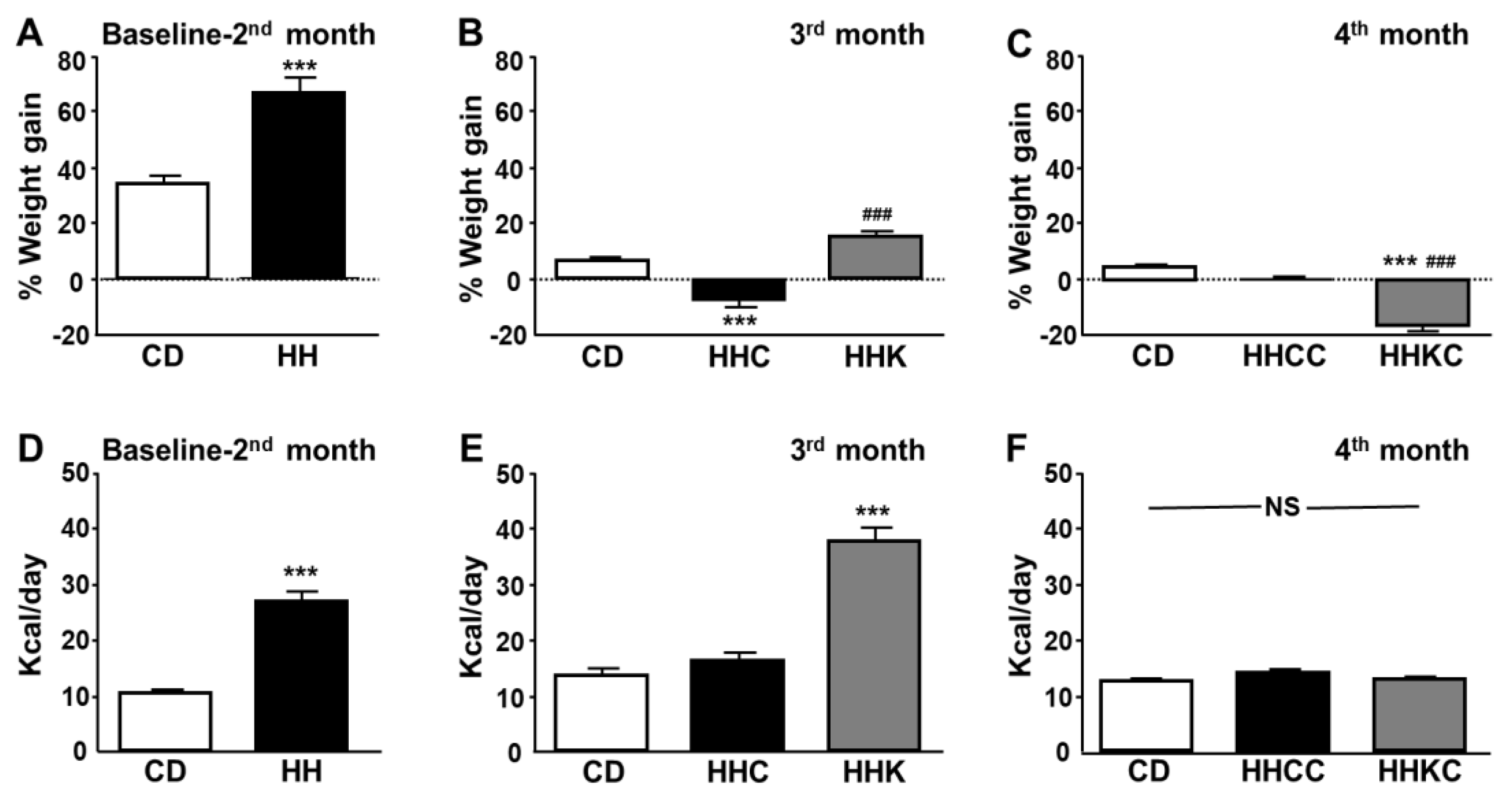

3.1. Weight and Caloric Intake Differ Between KD and CD

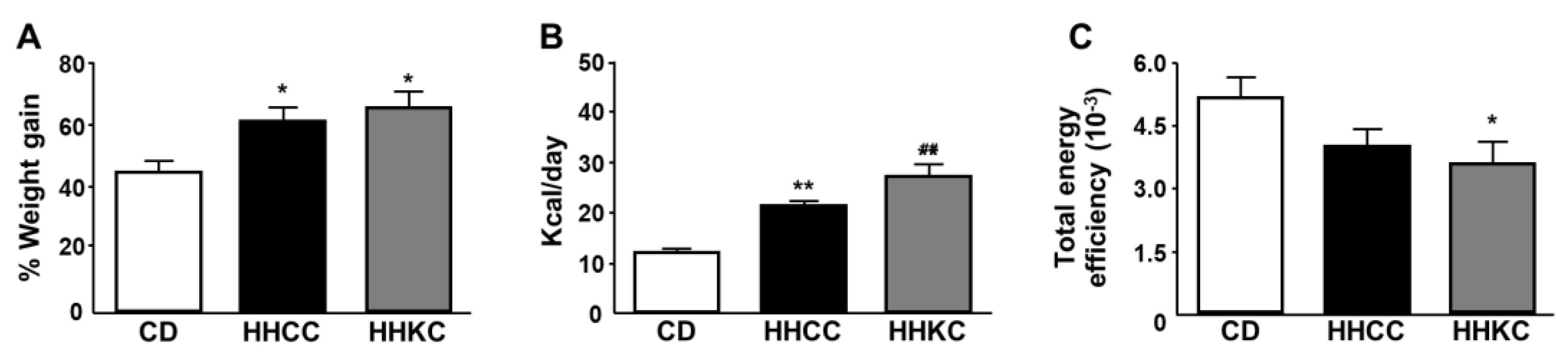

3.2. Differences in Weight Gain, Caloric Intake and Energy Efficiency During the Entire Study Period

3.3. General Characteristics of the Experimental Groups

3.3.1. KD or CD Administration in Obese Mice (3 Months)

3.3.1. CD Administration to HHC and HHK (4 Months)

3.4. KD Generates a Better Cytokine Profile than CD in the Circulation, but Not in Liver

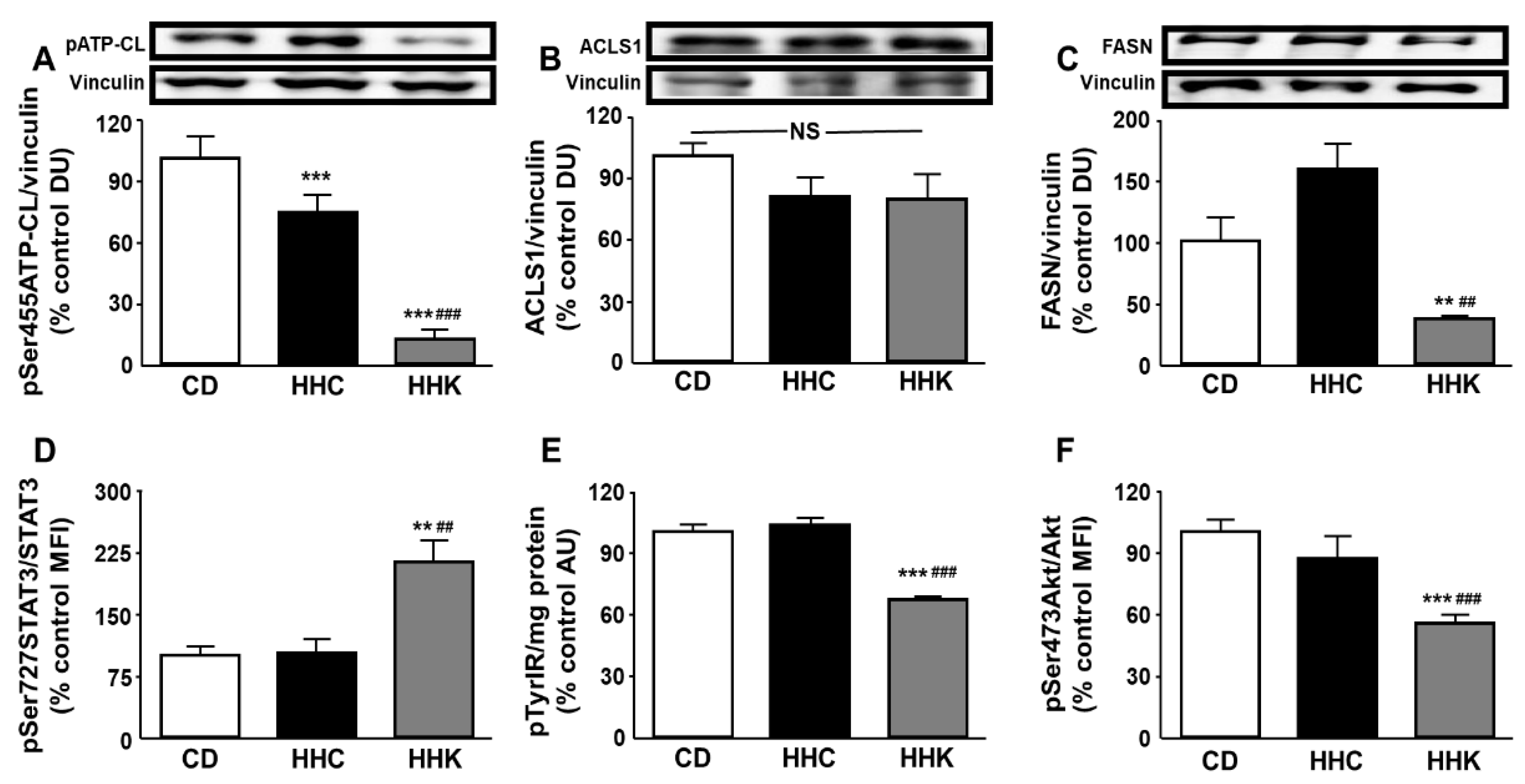

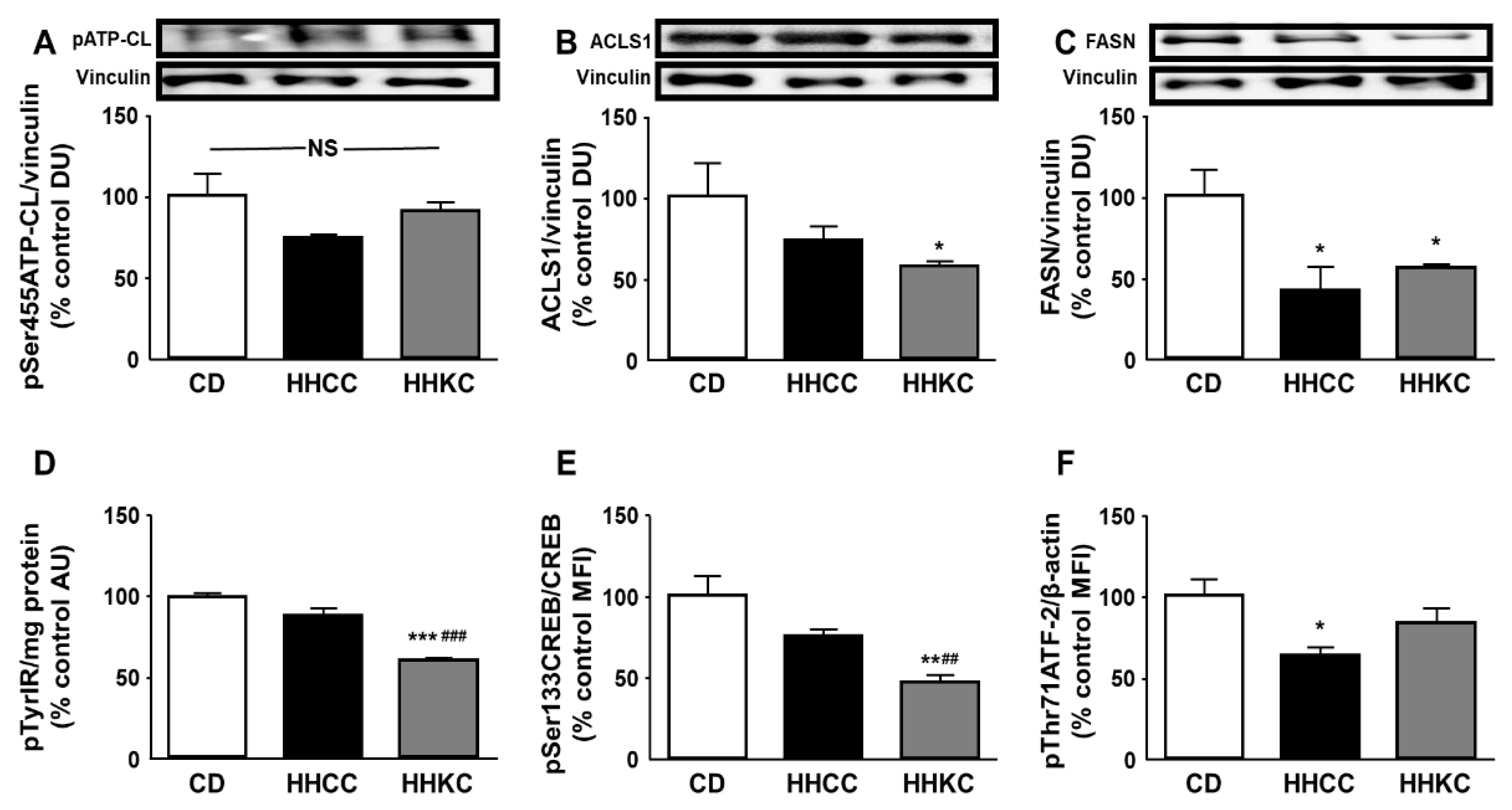

3.5. KD Reduces Activation and Levels of Enzymes of Fatty Acid Anabolism and Akt-Related Signaling in Obese Mice

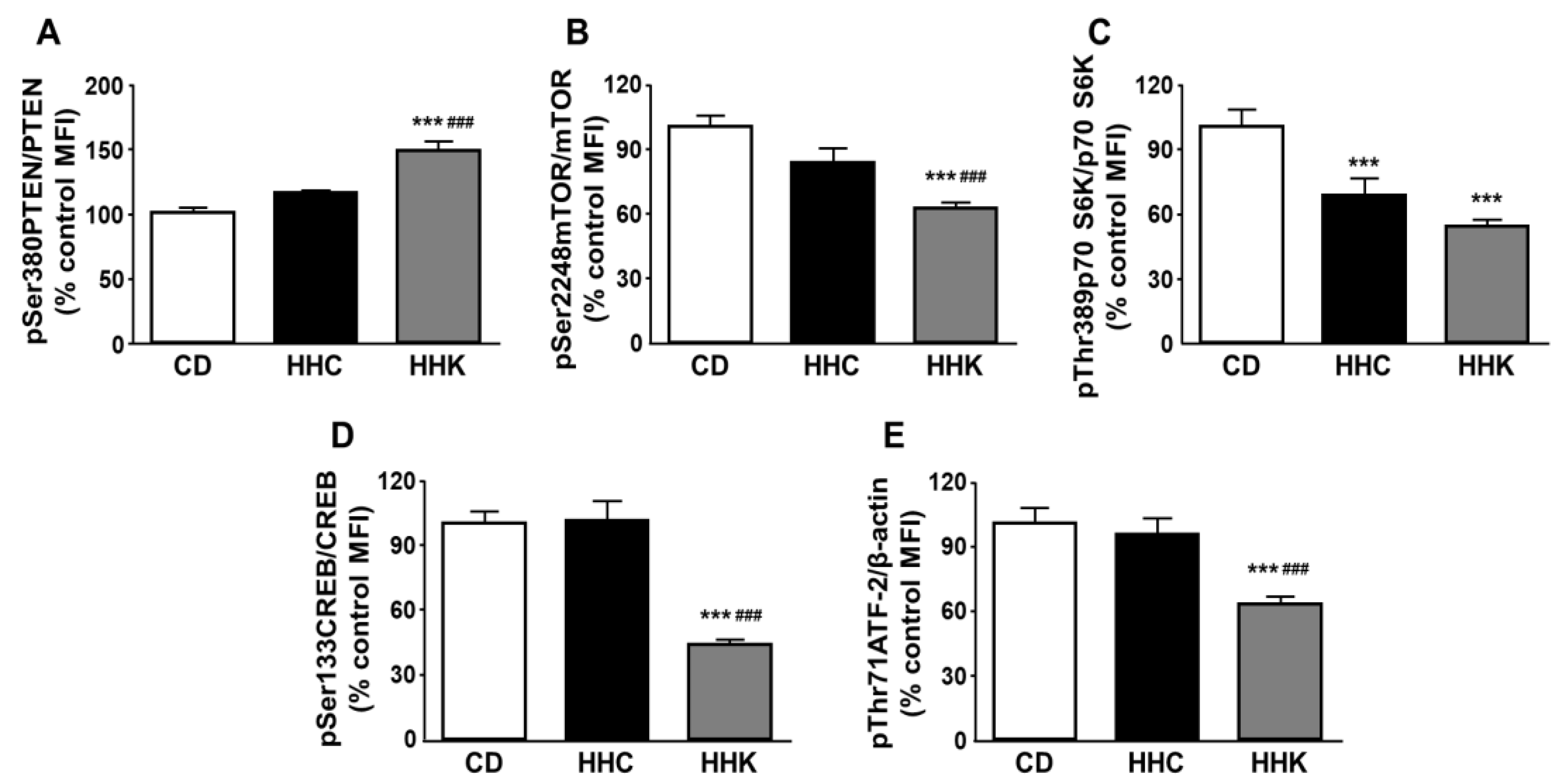

3.6. Decreased Hepatic FASN Levels in KD-Fed Mice Are Associated with Changes in Activation of Downstream Akt Signaling

3.7. Effect of Reintroduction of a CD to Obese Mice previously Fed a KD on Lipid Anabolism Enzymes and Insulin-Related Signaling

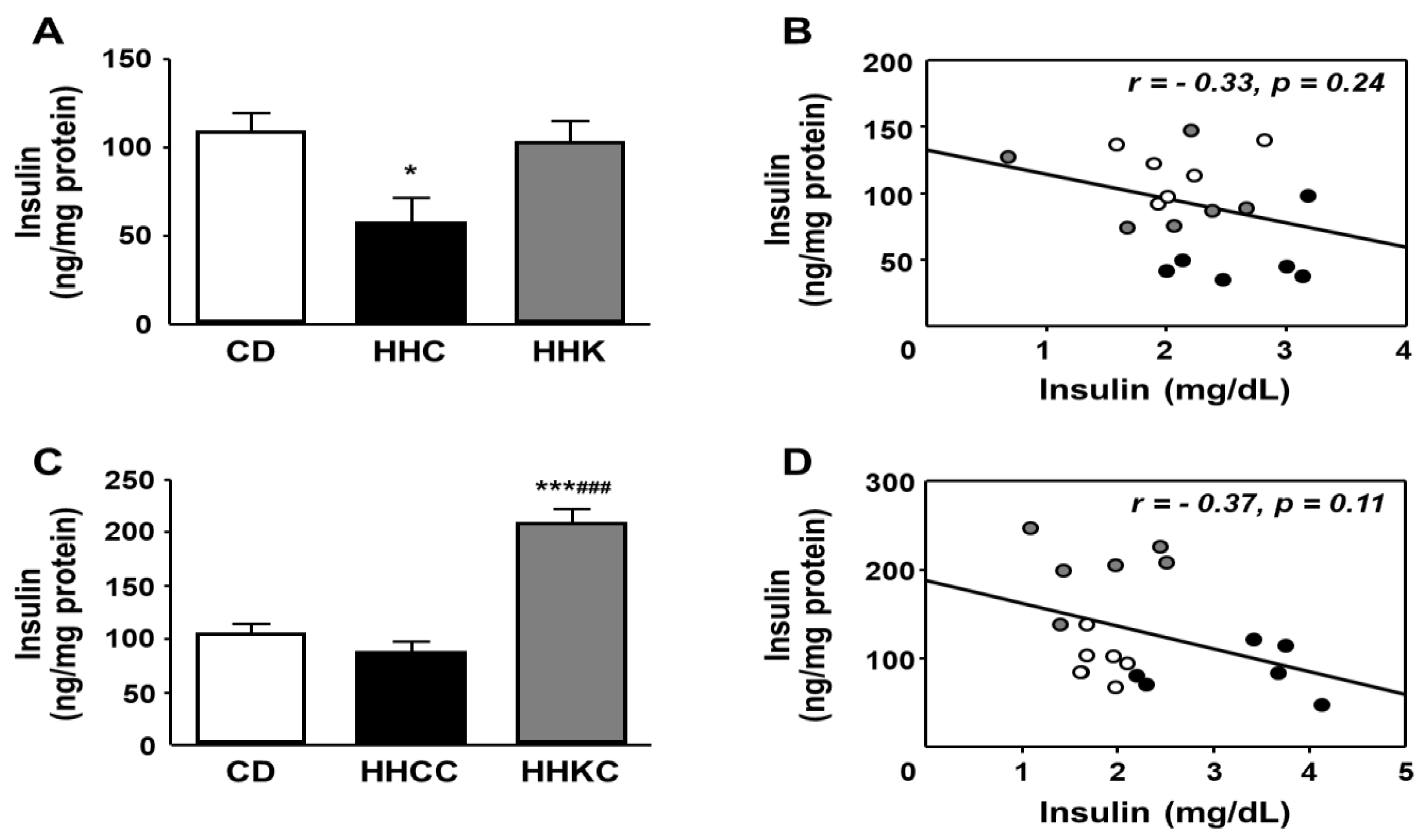

3.8. Changes in Hepatic Insulin Content After CD or KD Intake in Obese Mice and Reintroduction of CD to Both Groups of Mice

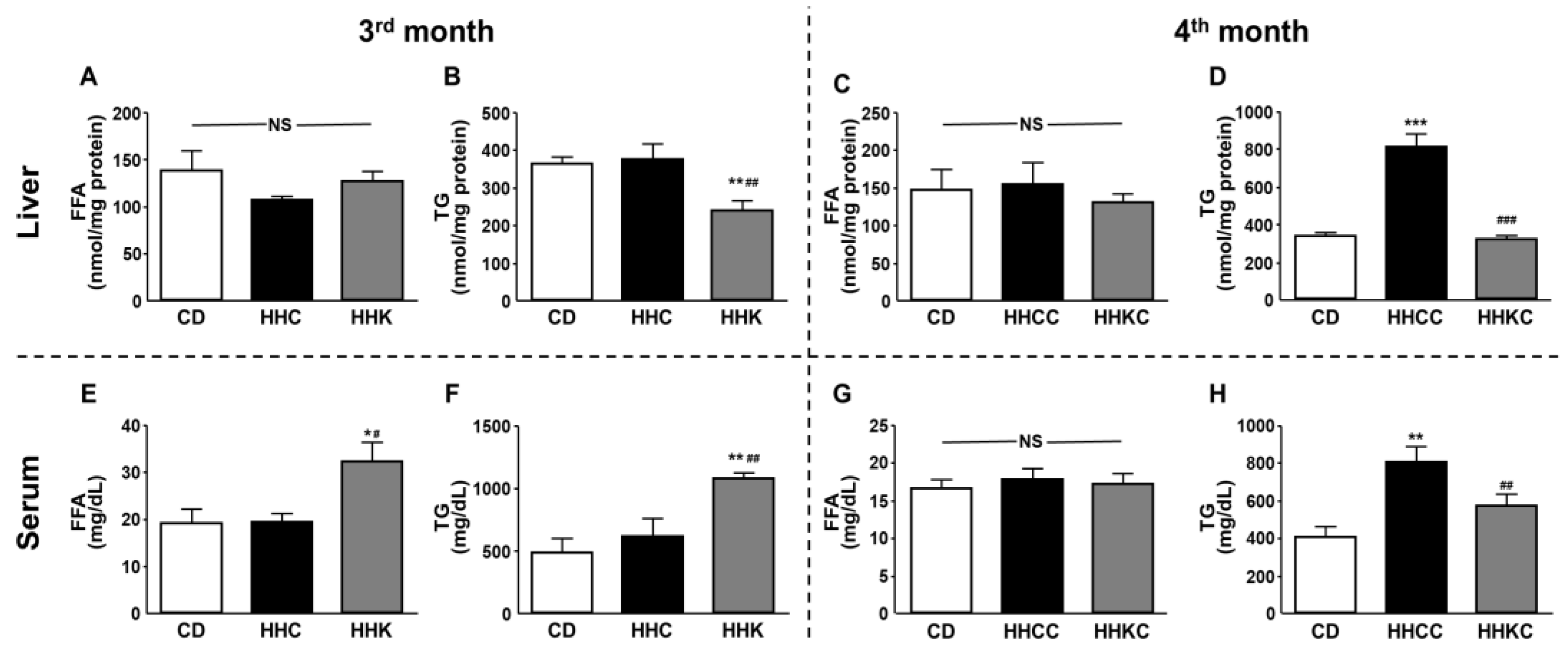

3.9. KD Causes a Reduction in Hepatic TG Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSL1 | long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| ATF-2 | Activating transcription factor 2 |

| ATP-CL | ATP citrate lyase |

| AU | Absorbance units |

| CD | Chow diet |

| CEACAM1 | Carcino-embryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| DU | Densitometry units |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HHC | HFD plus CD |

| HHCC | HHC plus CD |

| HHK | HFD plus KD |

| HHKC | HHK plus CD |

| HMW | High molecular weight |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IR | Insulin receptor |

| KD | Ketogenic diet |

| MFI | Median fluorescence intensity |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NS | Non-significant |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| p70 S6K | p70 S6 kinase |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 |

| SREBP-1c | Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TMB | Tetramethylbenzidine |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Islam, M.S.; Wei, P.; Suzauddula, M.; Nime, I.; Feroz, F.; Acharjee, M.; Pan, F. The interplay of factors in metabolic syndrome: Understanding its roots and complexity. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddu, S.K.; Giannini, C.; Marcovecchio, M.L. Metabolic disorders in young people around the world. Diabetologia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou, I.A.; Argyrakopoulou, G.; Dalamaga, M.; Kokkinos, A. Dual and Triple Gut Peptide Agonists on the Horizon for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. An Overview of Preclinical and Clinical Data. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidou, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Fasoulas, A.; Papaliagkas, V.; Alexatou, O.; Chatzidimitriou, M.; Mentzelou, M.; Giaginis, C. Diabesity and Dietary Interventions: Evaluating the Impact of Mediterranean Diet and Other Types of Diets on Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Management. Nutrients 2023, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accacha, S.; Barillas-Cerritos, J.; Srivastava, A.; Ross, F.; Drewes, W.; Gulkarov, S.; De Leon, J.; Reiss, A.B. From Childhood Obesity to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Hyperlipidemia Through Oxidative Stress During Childhood. Metabolites 2025, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badman, M.K.; Kennedy, A.R.; Adams, A.C.; Pissios, P.; Maratos-Flier, E. A very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet improves glucose tolerance in ob/ob mice independently of weight loss. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 297, E1197–E1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Lenzen-Schulte, M.; Schloot, N.C.; Martin, S. Ketone bodies: From enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A. The Influence of Physical Exercise, Ketogenic Diet, and Time-Restricted Eating on De Novo Lipogenesis: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandivada, P.; Fell, G.L.; Pan, A.H.; Nose, V.; Ling, P.R.; Bistrian, B.R.; Puder, M. Eucaloric Ketogenic Diet Reduces Hypoglycemia and Inflammation in Mice with Endotoxemia. Lipids 2016, 51, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, K.; Barzegar, M.; Nezamdoost, E.; Shoaran, M.; Abbasi, M.M.; Ghasemi, B.; Madadi, S.; Raeisi, S. Hepatic toll of keto: Unveiling the inflammatory and structural consequences of ketogenic diet in rats. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Vetrani, C.V.; Caprio, M.; Cataldi, M.; Ghoch, M.E.; Elce, A.; Camajani, E.; Verde, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; et al. From the Ketogenic Diet to the Mediterranean Diet: The Potential Dietary Therapy in Patients with Obesity after CoVID-19 Infection (Post CoVID Syndrome). Curr. Obes. Rep. 2022, 11, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, E.; Chen, W.; Dodd, G.T.; Conductier, G.; Coppari, R.; Tiganis, T.; Cowley, M.A. Leptin Signaling in the Arcuate Nucleus Reduces Insulin’s Capacity to Suppress Hepatic Glucose Production in Obese Mice. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 346–355.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.E.; Liu, H.Y.; Cao, W.; Chen, J. Regulation of interleukin-6-induced hepatic insulin resistance by mammalian target of rapamycin through the STAT3-SOCS3 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, M.; Mazur, W.; Bułdak, R.J.; Zwirska-Korczala, K. Potential role of leptin, adiponectin and three novel adipokines -- visfatin, chemerin and vaspin -- in chronic hepatitis. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 1397–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachithanandan, N.; Fam, B.C.; Fynch, S.; Dzamko, N.; Watt, M.J.; Wormald, S.; Honeyman, J.; Galic, S.; Proietto, J.; Andrikopoulos, S.; et al. Liver-specific suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 deletion in mice enhances hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipogenesis resulting in fatty liver and obesity. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbhuiya, P.A.; Yoshitomi, R.; Pathak, M.P. Understanding the Link Between Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein (SREBPs) and Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perianes-Cachero, A.; Burgos-Ramos, E.; Puebla-Jiménez, L.; Canelles, S.; Viveros, M.P.; Mela, V.; Chowen, J.A.; Argente, J.; Arilla-Ferreiro, E.; Barrios, V. Leptin-induced downregulation of the rat hippocampal somatostatinergic system may potentiate its anorexigenic effects. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, V.; Campillo-Calatayud, A.; Guerra-Cantera, S.; Canelles, S.; Martín-Rivada, Á.; Frago, L.M.; Chowen, J.A.; Argente, J. Opposite Effects of Chronic Central Leptin Infusion on Activation of Insulin Signaling Pathways in Adipose Tissue and Liver Are Related to Changes in the Inflammatory Environment. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Smith, M.S.; Reda, D.; Suffredini, A.F.; McCoy, J.P. Jr. Multiplex bead array assays for detection of soluble cytokines: Comparisons of sensitivity and quantitative values among kits from multiple manufacturers. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2004, 61, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partsalaki, I.; Karvela, A.; Spiliotis, B.E. Metabolic impact of a ketogenic diet compared to a hypocaloric diet in obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 25, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.; Seo, D.S.; Jang, Y. Metabolic Effects of Ketogenic Diets: Exploring Whole-Body Metabolism in Connection with Adipose Tissue and Other Metabolic Organs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchgessner, M.; Müller, H.L. Thermogenesis from the breakdown of a ketogenic diet in an experimental model using swine. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1984, 54, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basolo, A.; Magno, S.; Santini, F.; Ceccarini, G. Ketogenic Diet and Weight Loss: Is There an Effect on Energy Expenditure? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, J.A.; Fu, P.P.; Kumar, P.; Mells, J.E.; Sharma, S.; Saxena, N.K.; Anania, F.A. Adiponectin inhibits leptin signalling via multiple mechanisms to exert protective effects against hepatic fibrosis. Biochem. J. 2011, 440, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, H.M.; Abdelmageed, M.E.; Suddek, G.M. Molsidomine ameliorates DEXA-induced insulin resistance: Involvement of HMGB1/JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1002, 177832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, J.J.; Klover, P.J.; Nowak, I.A.; Zimmers, T.A.; Koniaris, L.G.; Furlanetto, R.W.; Mooney, R.A. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3), a potential mediator of interleukin-6-dependent insulin resistance in hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 13740–13746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.A. Calorie restriction and glucose regulation. Epilepsia 2008, 49 (Suppl 8), 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douris, N.; Melman, T.; Pecherer, J.M.; Pissios, P.; Flier, J.S.; Cantley, L.C.; Locasale, J.W.; Maratos-Flier, E. Adaptive changes in amino acid metabolism permit normal longevity in mice consuming a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 2056–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, S.M.; Perdomo, G. Hepatic Insulin Clearance: Mechanism and Physiology. Physiology (Bethesda) 2019, 34, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ke, B.; Zhao, Z.; Ye, X.; Gao, Z.; Ye, J. Regulation of insulin degrading enzyme activity by obesity-associated factors and pioglitazone in liver of diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.M.; Mathew, T.C.; Hussein, T.; Asfar, S.K.; Behbahani, A.; Khoursheed, M.A.; Al-Sayer, H.M.; Bo-Abbas, Y.Y.; Al-Zaid, N.S. Long-term effects of a ketogenic diet in obese patients. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2004, 9, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellanti, F.; Losavio, F.; Quiete, S.; Lo Buglio, A.; Calvanese, C.; Dobrakowski, M.; Kasperczyk, A.; Kasperczyk, S.; Vendemiale, G.; Cincione, R.I. A multiphase very-low calorie ketogenic diet improves serum redox balance by reducing oxidative status in obese patients. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbow, J.R.; Doherty, J.M.; Schugar, R.C.; Travers, S.; Weber, M.L.; Wentz, A.E.; Ezenwajiaku, N.; Cotter, D.G.; Brunt, E.M.; Crawford, P.A. Hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and ER stress in mice maintained long term on a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 300, G956–G967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari, C.; Murdun, C.; Koutnik, A.P.; Goldhagen, C.R.; Rogers, C.; Park, C.; Bharwani, S.; Diamond, D.M.; Kindy, M.S.; D’Agostino, D.P.; et al. Exogenous Ketones Lower Blood Glucose Level in Rested and Exercised Rodent Models. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, N.; Curatolo, N.; Benoist, J.F.; Auvin, S. Ketogenic diet exhibits anti-inflammatory properties. Epilepsia 2015, 56, e95–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, L.d.F.; Compri, C.M.; Fornari, J.V.; Bartchewsky, W.; Cintra, D.E.; Trevisan, M.; Carvalho, P.d.O.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Velloso, L.A.; Saad, M.J.; et al. The immunosuppressant drug, thalidomide, improves hepatic alterations induced by a high-fat diet in mice. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premeti, K.; Tsipa, D.; Nadalis, A.E.; Papanikolaou, M.G.; Syropoulou, V.; Karagkiozeli, K.D.; Aggelis, G.; Iordanidou, E.; Labrakakis, C.; Pappas, P.; et al. First generation vanadium-based PTEN inhibitors: Comparative study in vitro and in vivo and identification of a novel mechanism of action. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 233, 116756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkani, R.; Adeli, K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, A.; Hu, J.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Inhibition of neuropilin-1 improves non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat-diet induced obese mouse. Minerva Endocrinol. (Torino) 2023, 48, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodsky, L.; Wilson, M.; Rathinasabapathy, T.; Komarnytsky, S. Triptolide Administration Alters Immune Responses to Mitigate Insulin Resistance in Obese States. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornayvaz, F.R.; Jurczak, M.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Frederick, D.W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.M.; Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. A high-fat, ketogenic diet causes hepatic insulin resistance in mice, despite increasing energy expenditure and preventing weight gain. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E808–E815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, F.; Bhatti, M.R.; Kellenberger, A.; Sun, W.; Modica, S.; Höring, M.; Liebisch, G.; Krieger, J.P.; Wolfrum, C.; Challa, T.D. A low-carbohydrate diet induces hepatic insulin resistance and metabolic associated fatty liver disease in mice. Mol. Metab. 2023, 69, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Che, L.; Li, L.; Pilo, M.G.; Cigliano, A.; Ribback, S.; Li, X.; Latte, G.; Mela, M.; Evert, M.; et al. Co-activation of AKT and c-Met triggers rapid hepatocellular carcinoma development via the mTORC1/FASN pathway in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, M.J.; Wong, R.H.; Pandya, N.; Sul, H.S. Direct interaction between USF and SREBP-1c mediates synergistic activation of the fatty-acid synthase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 5453–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, G.; Guethlein, L.A.; Rössler, O.G. Insulin-Responsive Transcription Factors. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Shao, Z.; Jiang, E.; Zhou, X.; Shang, Z. Enhanced lipid biosynthesis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cancer-associated fibroblasts contributes to tumor progression: Role of IL8/AKT/p-ACLY axis. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Ding, D.; Li, Y. Regulation of Hepatic Metabolism and Cell Growth by the ATF/CREB Family of Transcription Factors. Diabetes 2021, 70, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Patil, I.Y.; Jiang, T.; Sancheti, H.; Walsh, J.P.; Stiles, B.L.; Yin, F.; Cadenas, E. High-fat diet induces hepatic insulin resistance and impairment of synaptic plasticity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, D.J.; Leitner, J.W.; Watson, P.; Nesterova, A.; Reusch, J.E.; Goalstone, M.L.; Draznin, B. Insulin-induced adipocyte differentiation. Activation of CREB rescues adipogenesis from the arrest caused by inhibition of prenylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 28430–28435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.C.; Hyun, C.G. Inhibitory Effects of Pinostilbene on Adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes: A Study of Possible Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Zhou, J.; Amin, S.A.; Imir, A.G.; Yilmaz, M.B.; Lin, Z.; Bulun, S.E. A novel role of sodium butyrate in the regulation of cancer-associated aromatase promoters I.3 and II by disrupting a transcriptional complex in breast adipose fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2585–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppelreuther, M.; Lundsgaard, A.M.; Mensberg, P.; Sjøberg, K.; Vilsbøll, T.; Kiens, B.; Füllekrug, J. Acyl-CoA synthetase expression in human skeletal muscle is reduced in obesity and insulin resistance. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Surbhi; Goraya, S.; Byun, J.; Pennathur, S. Fatty acids and inflammatory stimuli induce expression of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 to promote lipid remodeling in diabetic kidney disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105502. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ren, C.; Dong, Y.; Wali, J.A.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Kou, G.; Raubenheimer, D.; Cui, Z. Ketogenic Diet Combined with Moderate Aerobic Exercise Training Ameliorates White Adipose Tissue Mass, Serum Biomarkers, and Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, S.; Da Eira, D.; Stefanovic, M.; Ceddia, R.B. The ketogenic diet prevents steatosis and insulin resistance by reducing lipogenesis, diacylglycerol accumulation and protein kinase C activity in male rat liver. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 4137–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, B.; Peraldi, P.; Filloux, C.; Sawka-Verhelle, D.; Hilton, D.; Van Obberghen, E. SOCS-3 is an insulin-induced negative regulator of insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15985–15991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benomar, Y.; Wetzler, S.; Larue-Achagiotis, C.; Djiane, J.; Tomé, D.; Taouis, M. In vivo leptin infusion impairs insulin and leptin signalling in liver and hypothalamus. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2005, 242, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, F.K.; Levi, J.; Denroche, H.C.; Gray, S.L.; Voshol, P.J.; Neumann, U.H.; Speck, M.; Chua, S.C.; Covey, S.D.; Kieffer, T.J. Disruption of hepatic leptin signaling protects mice from age- and diet-related glucose intolerance. Diabetes 2010, 59, 3032–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter (3 months) | CD | HHC | HHK |

| Liver weight (% BW) | 4.50 ± 0.12 | 4.44 ± 0.24 | 3.91 ± 0.20 * |

| Inguinal fat (% BW) | 1.15 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.19 | 2.94 ± 0.81 * # |

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 130.3 ± 5.9 | 105.3 ± 5.2 | 89.6 ± 7.8 ** |

| Serum insulin (ng/mL) | 2.07 ± 0.26 | 2.91 ± 0.27 | 1.92 ± 0.21 # |

| HOMA-IR | 16.03 ± 2.42 | 19.67 ± 2.63 | 10.93 ± 1.57 # |

| Serum leptin (ng/ml) | 3.77 ± 0.36 | 2.84 ± 0.45 | 15.91 ± 4.18 * # |

| Serum ADP (µg/mL) | 3.88 ± 0.17 | 2.92 ± 0.43 | 3.58 ± 0.19 |

| Serum HMW-ADP (µg/mL) | 1.87 ± 0.11 | 1.57 ± 0.32 | 2.94 ± 0.05 *** ### |

| Parameter (4 months) | CD | HHCC | HHKC |

| Liver weight (% BW) | 4.53 ± 0.12 | 5.08 ± 0.25 | 4.34 ± 0.07 # |

| Inguinal fat (% BW) | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 2.24 ± 0.41 ** ## |

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 113.1 ± 3.8 | 102.6 ± 8.00 | 117.8 ± 7.3 |

| Serum insulin (ng/mL) | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 3.05 ± 0.33 ** | 1.68 ± 0.23 ## |

| HOMA-IR | 12.59 ± 0.87 | 21.21 ± 3.44 * | 12.54 ± 1.73 # |

| Serum leptin (ng/ml) | 3.40 ± 0.79 | 4.82 ± 0.72 | 6.26 ± 1.22 |

| Serum ADP (µg/mL) | 3.02 ± 0.13 | 2.75 ± 0.17 | 2.89 ± 0.12 |

| Serum HMW-ADP (µg/mL) | 1.60 ± 0.28 | 1.51 ± 0.25 | 1.93 ± 0.42 |

| Parameter (3 months) | CD | HHC | HHK |

| Liver IL-1β (ng/mg protein) | 21.76 ± 2.67 | 21.14 ± 3.54 | 19.61 ± 2.50 |

| Liver IL-6 (ng/mg protein) | 22.52 ± 4.83 | 22.94 ± 1.68 | 17.83 ± 4.01 |

| Liver TNF-α (ng/mg protein) | 6.41 ± 0.54 | 7.92 ± 1.01 | 16.33 ± 2.28 ** ## |

| Serum IL-1β (pg/mL) | 108.1 ± 19.0 | 152.4 ± 25.5 | 69.6 ± 18.2 # |

| Serum IL-6 (pg/mL) | 16.07 ± 2.54 | 23.76 ± 8.95 | 20.0 ± 4.16 |

| Serum TNF-α (pg/mL) | 9.87 ± 1.10 | 20.77 ± 1.91 *** | 11.38 ± 1.24 ### |

| Parameter (4 months) | CD | HHCC | HHKC |

| Liver IL-1β (ng/mg protein) | 8.58 ± 2.27 | 17.31 ± 1.23 ** | 16.26 ± 1.02 ** |

| Liver IL-6 (ng/mg protein) | 12.85 ± 1.50 | 16.37 ± 0.63 | 19.34 ± 1.18 ** |

| Liver TNF-α (ng/mg protein) | 5.57 ± 1.97 | 5.12 ± 1.74 | 3.83 ± 1.35 |

| Serum IL-1β (pg/mL) | 145.8 ± 21.7 | 152.3 ± 25.7 | 62.3 ± 7.9 ** ## |

| Serum IL-6 (pg/mL) | 18.20 ± 3.24 | 21.13 ± 5.06 | 12.84 ± 3.53 |

| Serum TNF-α (pg/mL) | 11.29 ± 0.85 | 20.63 ± 3.29 ** | 9.54 ± 2.02 ## |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).