Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

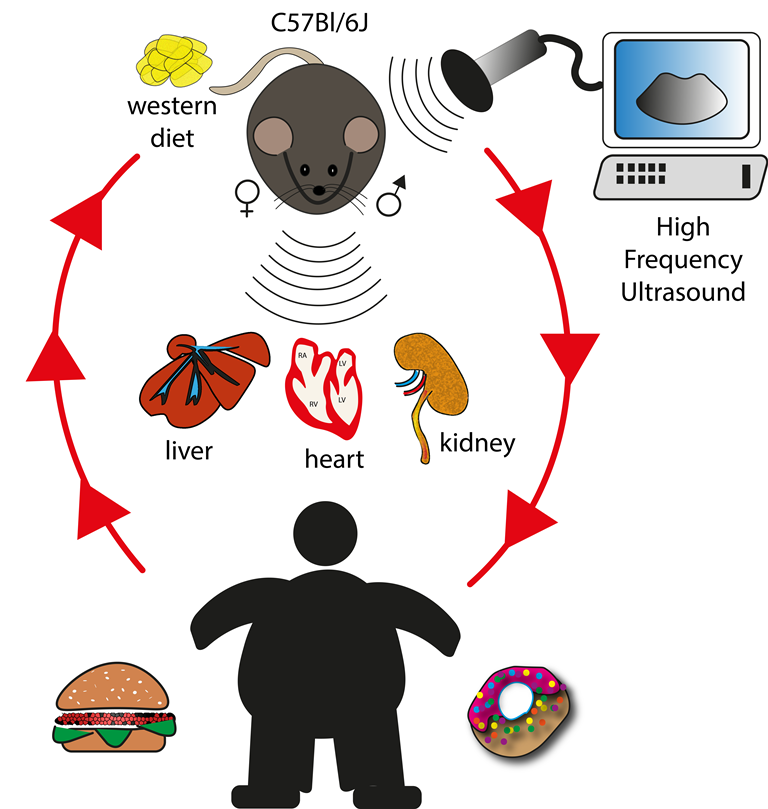

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Study Design and Animals

Biochemical Analysis

Ultrasound Imaging

- Echostructure – score 1: homogenous liver parenchyma and regular hepatic surface; score 2 (mild steatosis): diffuse parenchymal mild heterogeneity, reduced visualization of the diaphragm and small peripheral vessels with no change on liver surface; score 3 (moderate steatosis): discrete coarse and heterogeneous parenchymal echogenicity, dotted or slightly irregular liver surface; score 4 (severe steatosis): extensive coarse and heterogeneous parenchymal echostructure, marked echogenicity, irregular or nodular hepatic surface with underlying regenerative nodules, obscured diaphragm and reduced visibility of kidney.

- Echogenicity (relative to the renal cortex) – score 0: liver less echogenic than the renal cortex; score 1: hepatic echogenicity equal to the renal cortex; score 2: liver more echogenic than the renal cortex.

- Presence of ascites – score 0: absent; score1: present.

- Parametric analysis: The hepatic parenchyma is less echogenic than the right renal cortex in the great majority of rodents, a finding that contrasts with humans [48]. The hepatic echogenicity increases due to the presence of fatty infiltration and/or fibrosis, changing the relation between liver and right renal cortex [9].

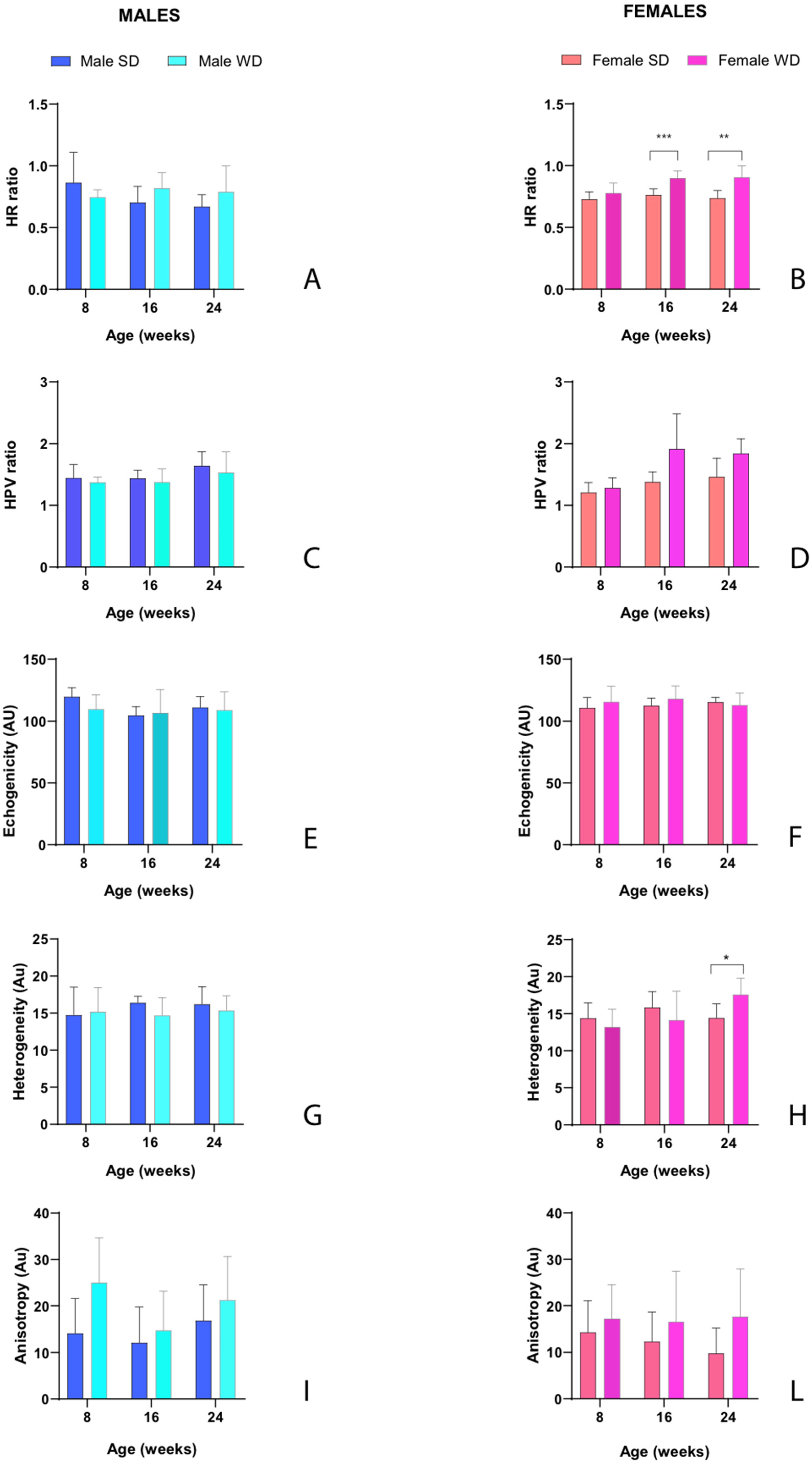

- hepatic-renal ratio (HR): This measurement is based on the hypothesis that a higher liver fat content causes an increase in US liver echogenicity. Longitudinal view was acquired in order to have both the liver (caudate lobe) and the right kidney clearly visualized. Liver echogenicity was compared with that of the renal parenchyma, to normalize differences in the overall US gain value used for the acquisitions. Two regions of interest (ROI, (0.1±0.02 mm2) were manually drawn: the first one was placed in the liver parenchyma avoiding focal hypo and hyperechogenicity; the second was positioned in correspondence with a portion of the renal cortex devoid of large vessels, along the focusing area of the image, at the same distance from the probe and along the focus area of the image to avoid distorting effects in ultrasonic wave patterns. HR values were obtained dividing the mean grey level of the hepatic ROI for that obtained for the renal one (Pixel intensity = average intensity/mm2 [a.u.]) [7,46].

- hepatic-portal vein ratio (HPV): Similarly to HR, liver echogenicity was normalized for that correspondent to the blood within the portal vein. The evaluation of this parameter requires the acquisition of US images in order to correctly visualized a portion of the portal vein in the center of the liver. Two ROIs (0.1±0.02 mm2) were manually drawn: the first one was positioned within the portal vein lumen, while the second was placed at the same depth to keep the ultrasound attenuation comparable of the liver parenchyma, avoiding focal hypo and hyperechogenicity. To avoid effects related to borderline echo distortion, the two ROIs were placed as close as possible to the center of the image [7,46].

- gray-level histogram analysis of echogenicity (GLH): liver images at different scanning planes (left lateral lobe, longitudinal; caudate lobe, longitudinal; right median lobe, axial.) were analyzed using a gray-level histogram to obtain the quantitative mean and standard deviation values of echogenicity of each spatial region. Anatomical landmarks (greater curvature of stomach; cranial pole of the right kidney; porta hepatis, at the level which aorta, portal vein, caudal vena cava are visible in cross-section) were chosen to scan imaging planes reproducible. ROIs (1±0.02 mm2) were manually drawn in the liver parenchyma avoiding focal hypo and hyperechogenicity as close as possible in the center of the image, providing objective values of echointensity and echotexture. This approach is useful to include more representative parts of the hepatic parenchyma and avoid errors due to image artifacts, with good intra-observer reproducibility [49]. Changes in brightness and variance of the liver parenchyma were reported as: i) mean echogenicity of different lobes; ìì) standard deviation of brightness within ROI encompassing right median lobe as measure of tissue heterogeneity; ììì) standard deviation of brightness among ROIs in all planes imaged as measure of anisotropy [49,50].

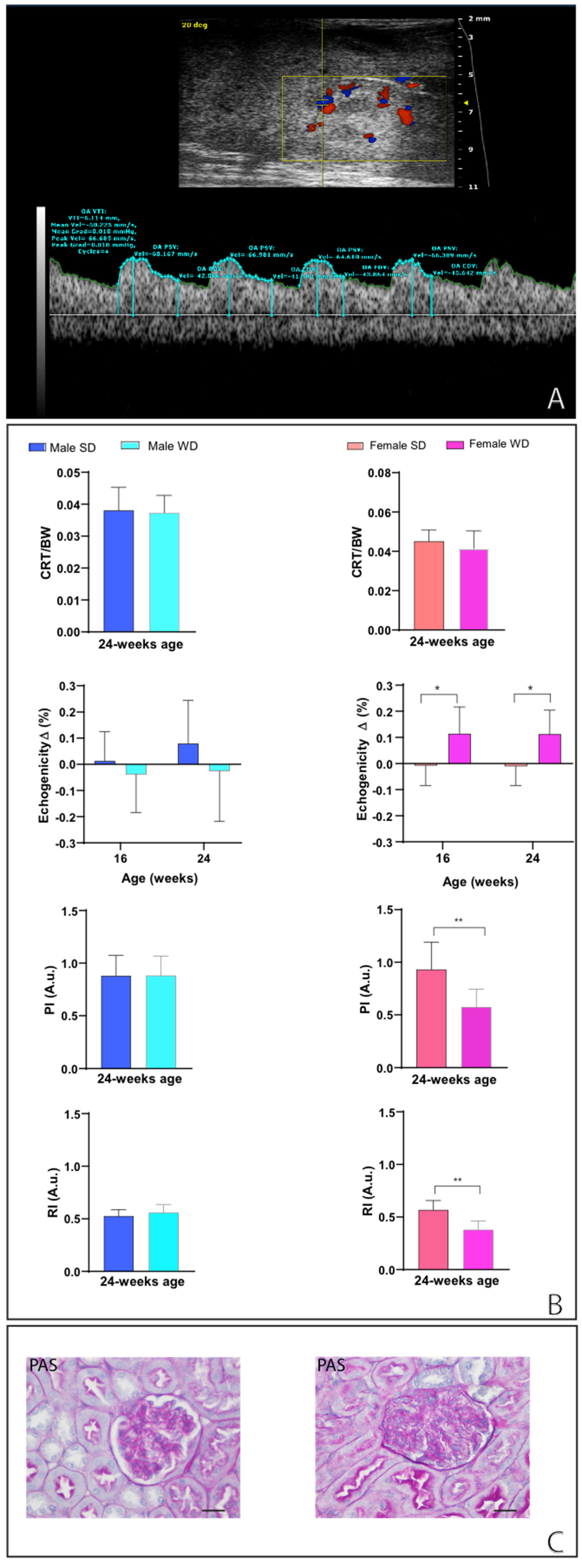

Histological Examination

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

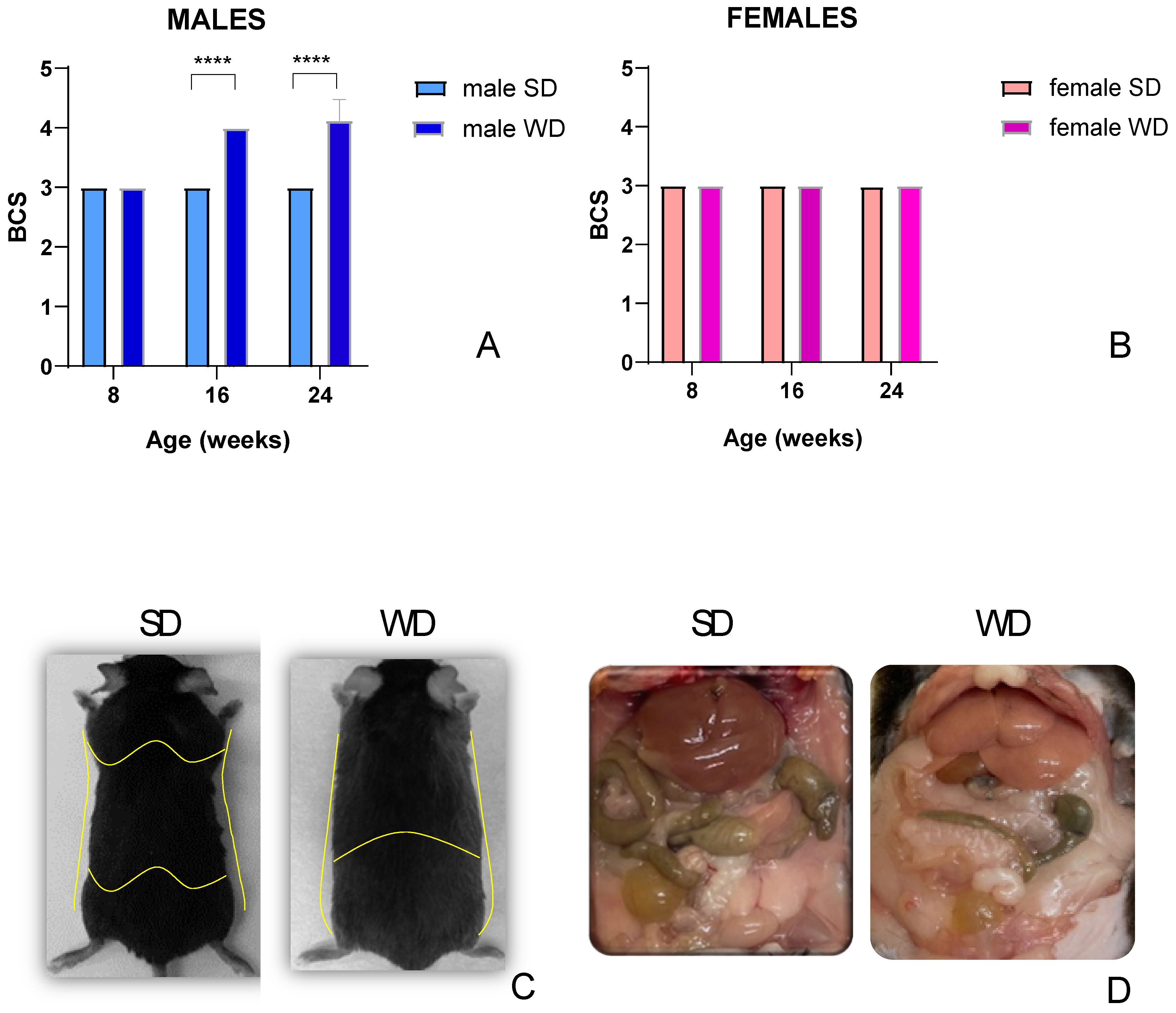

3.1. General Health-Behavioral Status

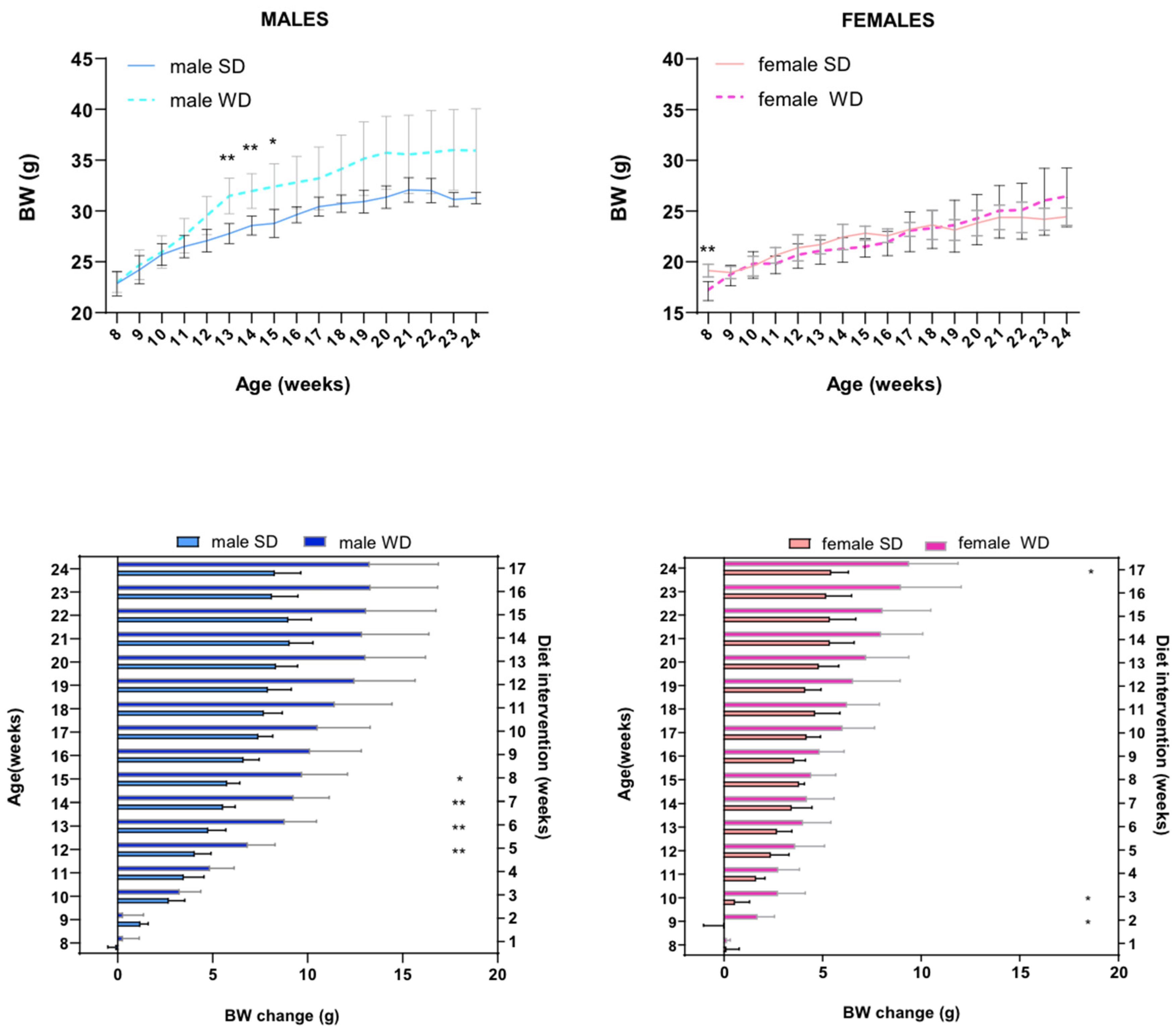

3.2. Growth Metrics

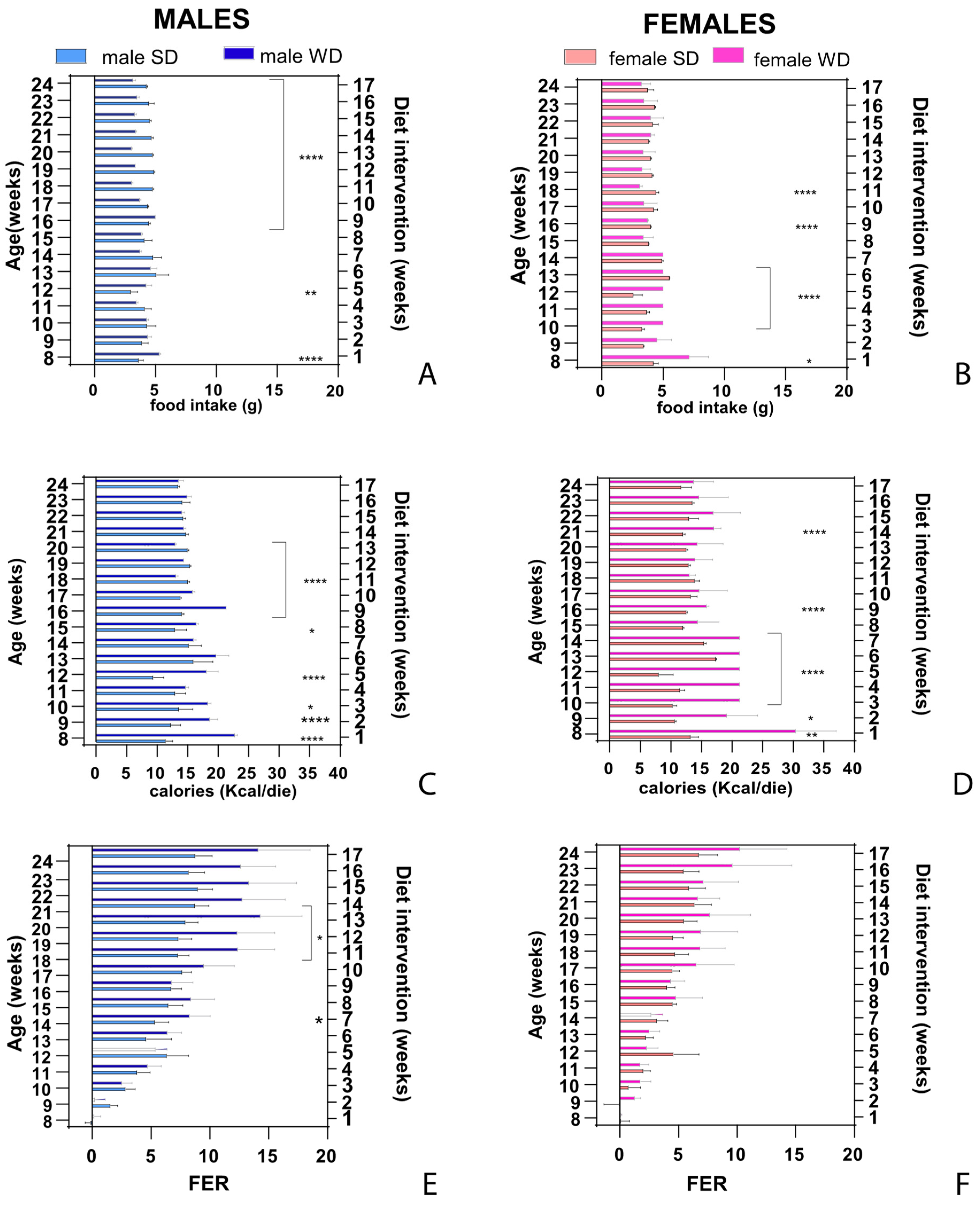

3.3. Feeding Behavior

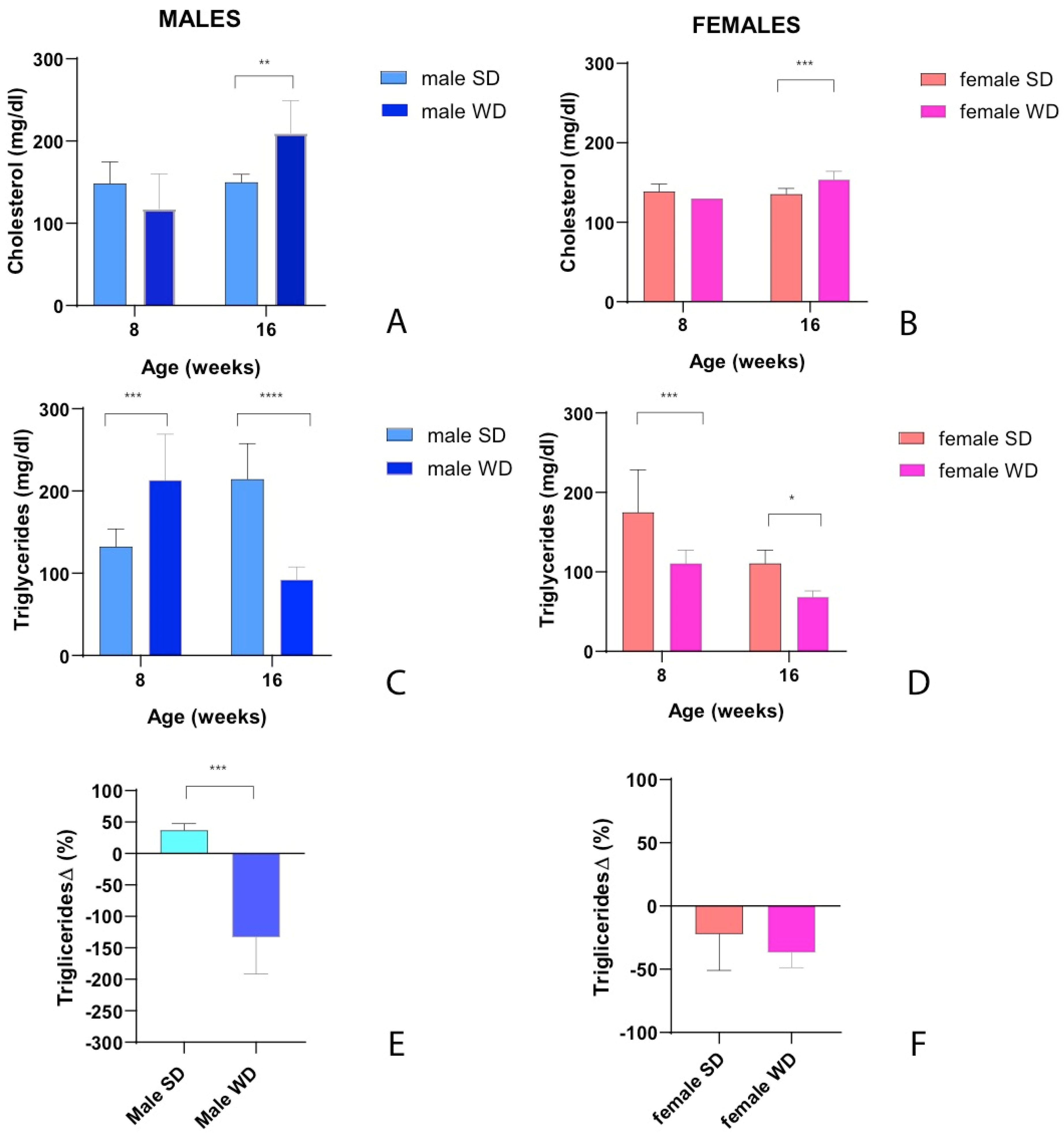

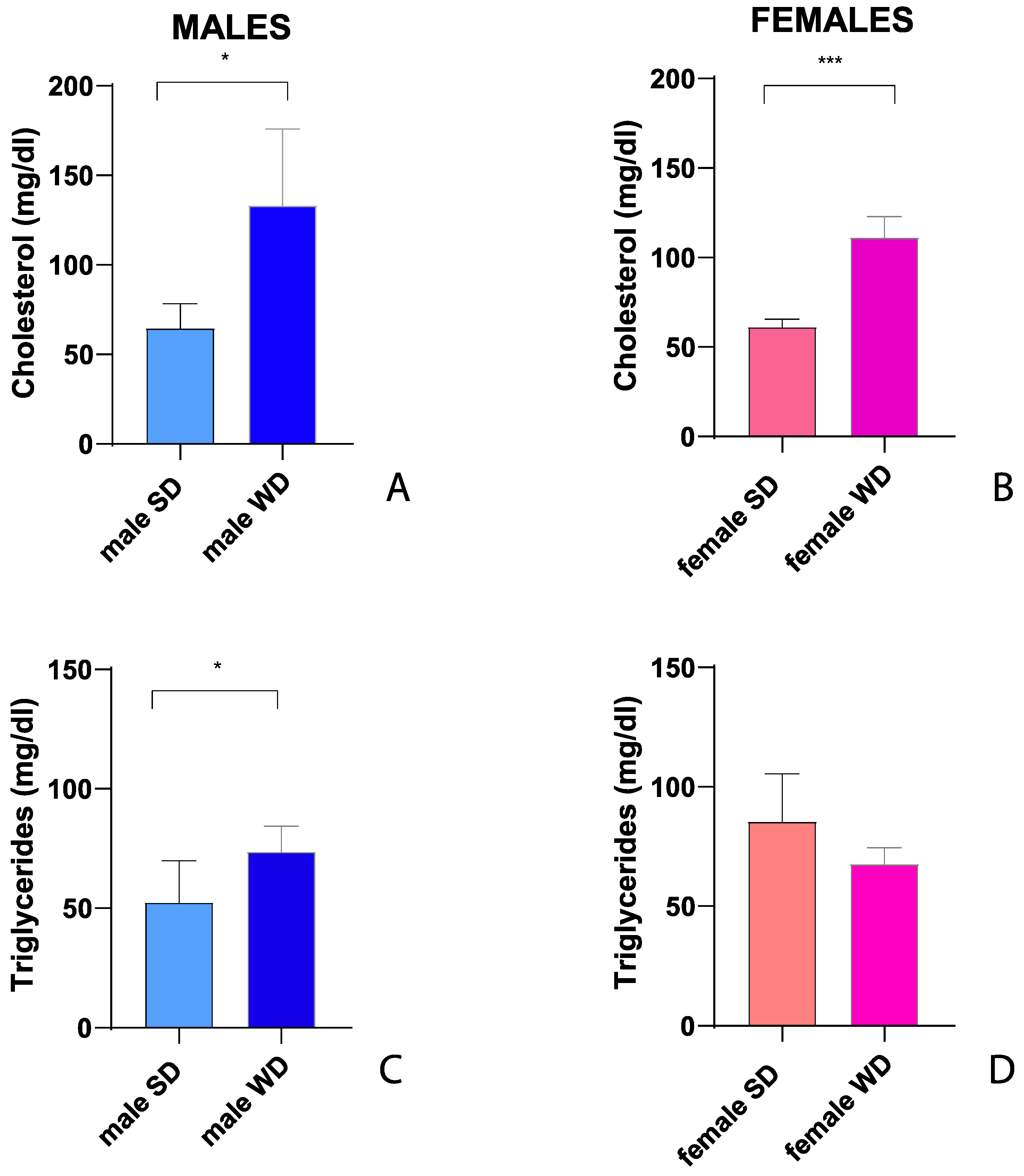

3.4. Lipid Metabolism

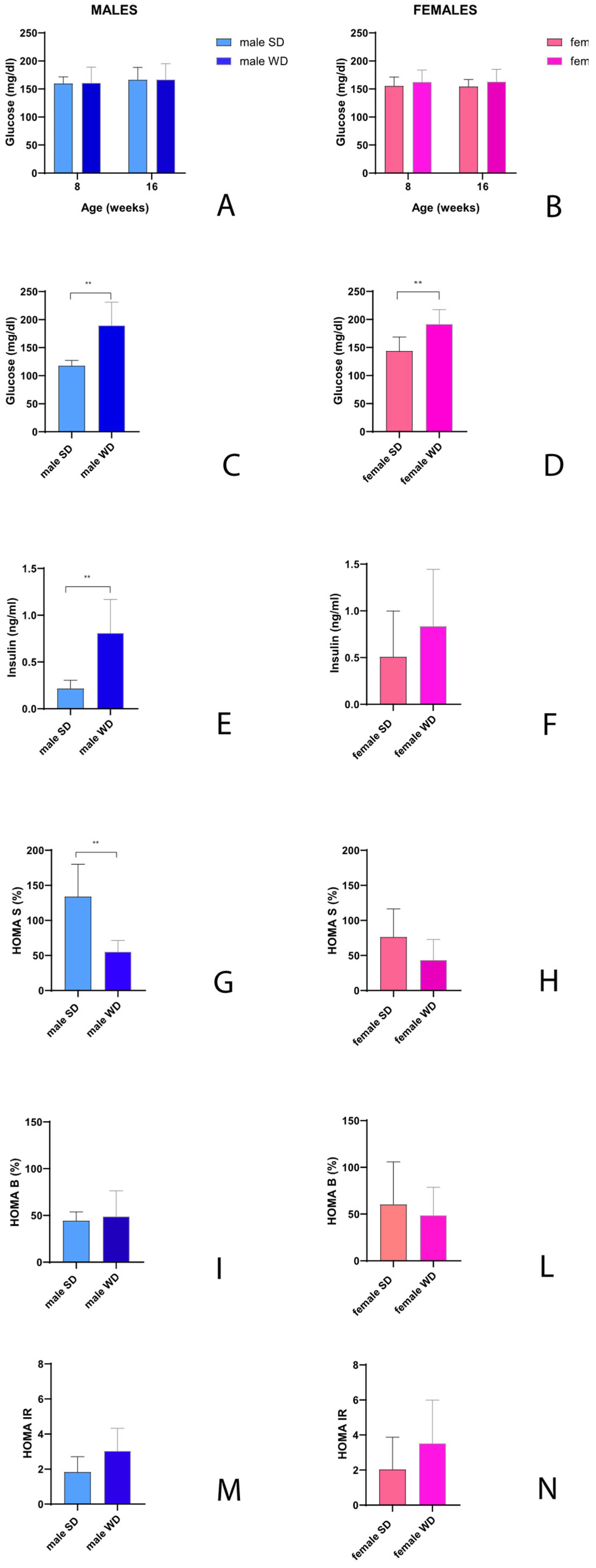

3.5. Glucose Homeostasis

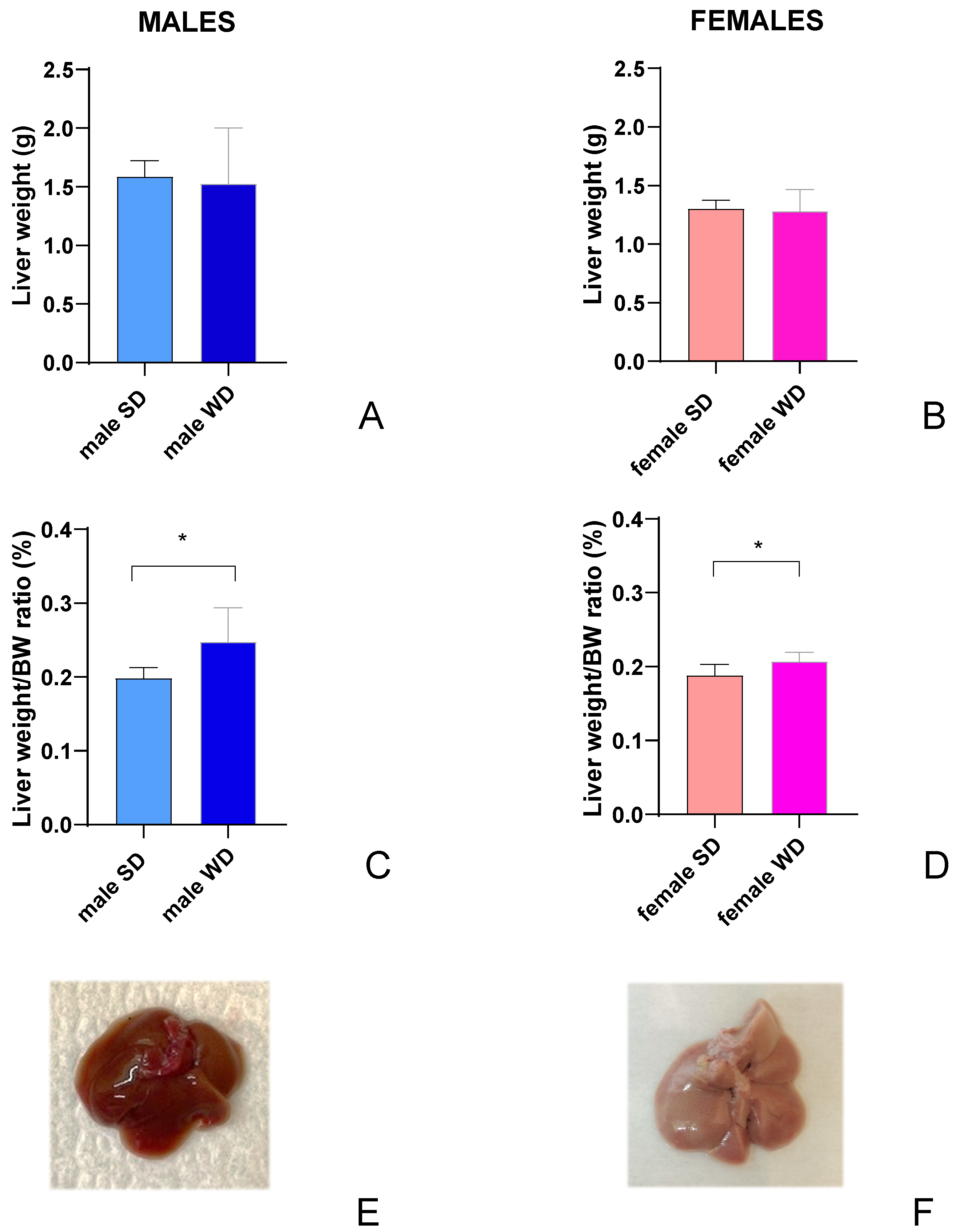

3.6. Liver and Kidneys Function

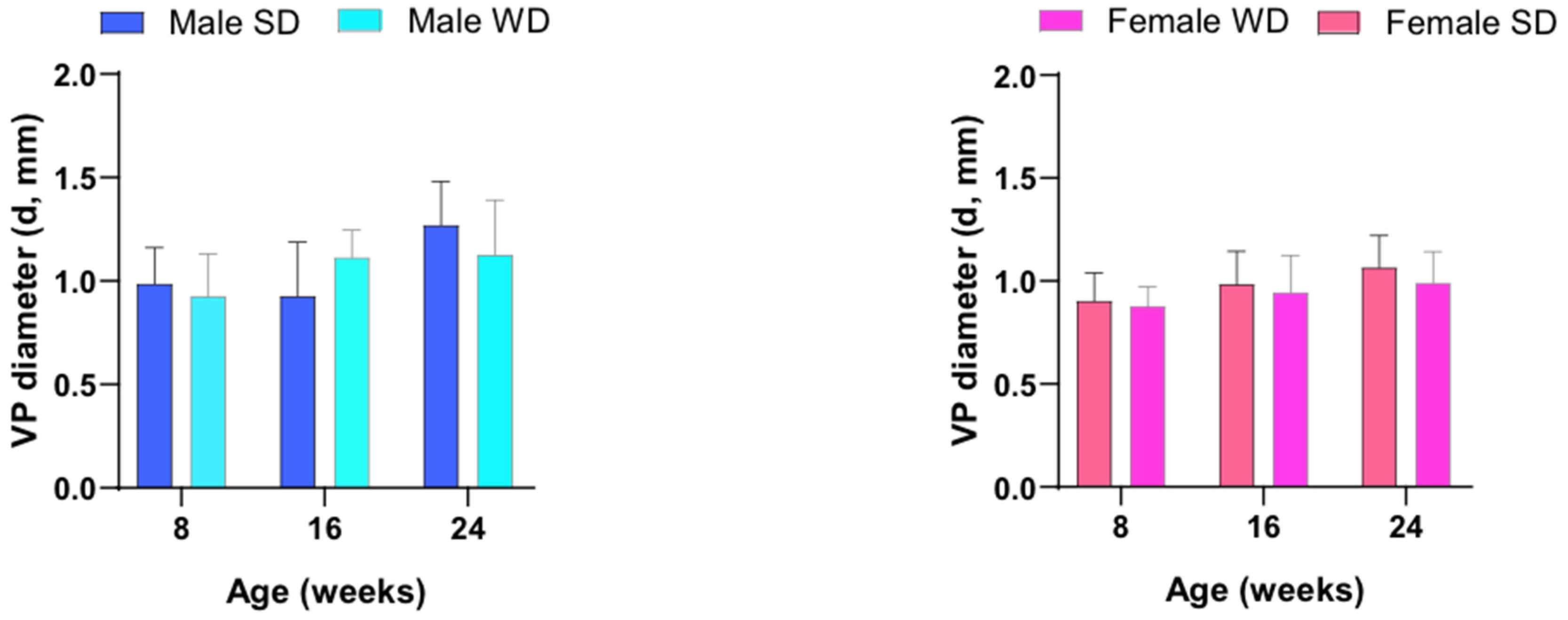

3.7. Ultrasound Imaging

3.7. Histological Examination

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casimiro, I., Stull, N.D., Tersey, S.A., Mirmira, R.G. Phenotypic sexual dimorphism in response to dietary fat manipulation in C57BL/6J mice. J Diabetes Complications. 2021 Feb;35(2):107795. [CrossRef]

- Siersbæk, M.S., Ditzel, N., Hejbøl, E.K., Præstholm, S.M., Markussen, L.K., Avolio, F., Li, L., Lehtonen, L., Hansen, A.K., Schrøder, H.D., Krych, L., Mandrup, S., Langhorn, L., Bollen, P., Grøntved, L. C57BL/6J substrain differences in response to high-fat diet intervention. Sci Rep. 2020 Aug 20;10(1):14052. [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R. Use of high-fat diets to study rodent obesity as a model of human obesity. Int J Obes 43, 1491–1492 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shi, H., Prough, R.A., McClain, C.J., Song, M. Different Types of Dietary Fat and Fructose Interactions Result in Distinct Metabolic Phenotypes in Male Mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2023 Jan;111:109189. [CrossRef]

- Hintze, K.J., Benninghoff, A.D., Cho, C.E., Ward, R.E. Modeling the Western Diet for Preclinical Investigations. Adv Nutr. 2018 May 1;9(3):263-271. [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, S., Gramanzini, M., Mancini, M. Molecular Imaging of Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaques in Animal Models. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Sep 9;17(9):1511. [CrossRef]

- Di Lascio, N., Kusmic, C., Stea, F., Lenzarini, F., Barsanti, C., Leloup, A., Faita, F. Longitudinal micro-ultrasound assessment of the ob/ob mouse model: evaluation of cardiovascular, renal and hepatic parameters. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018 Mar;42(3):518-524. [CrossRef]

- Pantaleão Jr., A.C.S., de Castro, M.P., Meirelles Araujo, K.S.F., Campos, C.F.F., da Silva, A.L.A., Manso, J.E.F., Machado, J.C. Ultrasound biomicroscopy for the assessment of early-stage nonalcoholic fatty liver disease induced in rats by a high-fat diet. Ultrasonography. 2022;41(4):750-760.

- Resende, C., Lessa, A., Goldenberg, R. C. S. Ultrasonic Imaging in Liver Disease: From Bench to Bedside. In Ultrasound Imaging - Medical Applications. London, United Kingdom: IntechOpen, 2011.

- Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/18256#B23. [CrossRef]

- Cui, G., Martin, R.C., Liu, X., Zheng, Q., Pandit, H., Zhang, P., Li, W., Li, Y. Serological biomarkers associate ultrasound characteristics of steatohepatitis in mice with liver cancer. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018 Oct 5;15:71. [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.M., Brand, S., Giles, A., Kolios, M.C., Czarnota, G.J. Quantitative ultrasound characterization of responses to radiotherapy in cancer mouse models. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Mar 15;15(6):2067-75. [CrossRef]

- Lavarello, R.J., Ridgway, W.R., Sarwate, S.S., Oelze, M.L. Characterization of thyroid cancer in mouse models using high-frequency quantitative ultrasound techniques. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013 Dec;39(12):2333-41. [CrossRef]

- Mirniaharikandehei, S., VanOsdol, J., Heidari, M., Danala, G., Sethuraman, S.N., Ranjan, A., Zheng, B. Developing a Quantitative Ultrasound Image Feature Analysis Scheme to Assess Tumor Treatment Efficacy Using a Mouse Model. Sci Rep 9, 7293 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Liang, W., Menke, A.L., Driessen, A., Koek, G.H., Lindeman, J.H., Stoop, R., Havekes, L.M., Kleemann, R., van den Hoek, A.M. Establishment of a general NAFLD scoring system for rodent models and comparison to human liver pathology. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 23;9(12):e115922. [CrossRef]

- Schipper, L., van Heijningen, S., Karapetsas, G., van der Beek, E.M., van Dijk, G. Individual housing of male C57BL/6J mice after weaning impairs growth and predisposes for obesity. PLoS One. 2020 May 26;15(5):e0225488. [CrossRef]

- Olga, L., Bobeldijk-Pastorova, I., Bas, R.C., Seidel, F., Snowden, S.G., Furse, S., Ong, K.K., Kleemann, R., Koulman, A. Lipid profiling analyses from mouse models and human infants. STAR Protoc. 2022 Dec 16;3(4):101679. [CrossRef]

- Ellacott, K.L., Morton, G.J., Woods, S.C., Tso, P., Schwartz, M.W. Assessment of feeding behavior in laboratory mice. Cell Metab. 2010 Jul 7;12(1):10-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y., Liao, J.K. A mouse model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;821:421-33. [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.K., Zhang, X., Yu, J. Animal models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current perspectives and recent advances. J Pathol 2017;241:36–44.

- Ali, M.A., Kravitz, A.V. Challenges in quantifying food intake in rodents. Brain Res. 2018 Aug 15;1693(Pt B):188-191. [CrossRef]

- Cowley, P.M., Roberts, C.R., Baker, A.J. Monitoring the Health Status of Mice with Bleomycin-induced Lung Injury by Using Body Condition Scoring. Comp Med. 2019 Apr 1;69(2):95-102. [CrossRef]

- Siriarchavatana, P., C.Kruger, M., & M.Wolber, F. Correlation between body condition score and body composition in a rat model for obesity research: Veterinary Integrative Sciences. 2022; 20(3), 531–545. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/vis/article/view/258598. [CrossRef]

- Hoggatt, J., Hoggatt, A.F., Tate, T.A., Fortman, J., Pelus, L.M. Bleeding the laboratory mouse: Not all methods are equal. Exp Hematol. 2016 Feb;44(2):132-137.e1. [CrossRef]

- Windeløv, J.A., Pedersen, J., Holst, J.J. Use of anesthesia dramatically alters the oral glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in C57Bl/6 mice. Physiol Rep. 2016 Jun;4(11):e12824. [CrossRef]

- Valladolid-Acebes, I., Daraio, T., Brismar, K., Harkany, T., Ögren, S.O., Hökfelt, T.G., Bark, C. Replacing SNAP-25b with SNAP-25a expression results in metabolic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Aug 4;112(31):E4326-35. [CrossRef]

- Pauter, A.M., Fischer, A.W., Bengtsson, T., Asadi, A., Talamonti, E., Jacobsson, A. Synergistic Effects of DHA and Sucrose on Body Weight Gain in PUFA-Deficient Elovl2 -/- Mice. Nutrients. 2019 Apr 15;11(4):852. [CrossRef]

- Carper, D., Coué, M., Laurens, C., Langin, D., Moro, C. Reappraisal of the optimal fasting time for insulin tolerance tests in mice. MOLECULAR METABOLISM. 2020, 42, 101058. [CrossRef]

- Fraulob, J.C., Ogg-Diamantino, R., Fernandes-Santos, C., Aguila, M.B., Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. A Mouse Model of Metabolic Syndrome: Insulin Resistance, Fatty Liver and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Pancreas Disease (NAFPD) in C57BL/6 Mice Fed a High Fat Diet. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;46(3):212-223. [CrossRef]

- Knopp, J.L., Holder-Pearson, L., Chase, J.G. Insulin Units and Conversion Factors: A Story of Truth, Boots, and Faster Half-Truths. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019 May;13(3):597-600. [CrossRef]

- Diabetes Trials Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Available online: https://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Avtanski, D., Pavlov, V.A., Tracey, K.J., Poretsky, L. Characterization of inflammation and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced male C57BL/6J mouse model of obesity. Animal Model Exp Med. 2019 Sep 25;2(4):252-258. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Hansson, G. K. Effect of Sex and Age on Serum Biochemical Reference Ranges in C57BL/6J Mice. Comparative Medicine 2004. Vol 54, No 2 April 2004, Pages 176-178.

- Mazzaccara, C., Labruna, G., Cito, G., Scarfò, M., De Felice, M., Pastore, L., Sacchetti, L. Age-Related Reference Intervals of the Main Biochemical and Hematological Parameters in C57BL/6J, 129SV/EV and C3H/HeJ Mouse Strains PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3772. [CrossRef]

- The Jackson Laboratory online resource library. Available online: http://jackson.jax.org/rs/444-BUH-304/images/physiological_data_000664.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Jensen, T., Kiersgaard, M., Sørensen, D., Mikkelsen, L. Fasting of mice: a review. Laboratory Animals. 2013;47(4):225-240. [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, C., Mean, R., Janssen, B.J. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the cardiovascular function of the C57BL/6 mouse. ILAR J. 2011, 52: 21-31.

- Sørensen, L.L., Bedja, D., Sysa-Shah, P., Liu, H., Maxwell, A., Yi, X., Pozios, I., Olsen, N.T., Abraham, T.P., Abraham, R., Gabrielson, K. Echocardiographic Characterization of a Murine Model of Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy Induced by Cardiac-specific Overexpression of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2. Comp Med. 2016;66(4):268-77.

- Andorko, J.I., Tostanoski, L.H., Solano, E., Mukhamedova, M., Jewell, C.M. Intra-lymph node injection of biodegradable polymer particles. J Vis Exp. 2014 Jan 2;(83):e50984. [CrossRef]

- Stypmann, J., Engelen, M.A., Troatz, C., Rothenburger, M., Eckardt, L., Tiemann, K. Echocardiographic assessment of global left ventricular function in mice. Laboratory Animals 2009; 43: 127–137. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Ho, D., Vatner, D.E., Vatner, S.F. Echocardiography in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2011 Mar 1; 1: 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Zacchigna, S., Paldino, A., Falcão-Pires, I., Daskalopoulos, E.P., Dal Ferro, M., Vodret, S., Lesizza, P., Cannatà, A., Miranda-Silva, D., Lourenço, A.P., Pinamonti, B., Sinagra, G., Weinberger, F., Eschenhagen, T., Carrier, L., Kehat, I., Tocchetti, C.G., Russo, M., Ghigo, A., Cimino, J., Hirsch, E., Dawson, D., Ciccarelli, M., Oliveti, M., Linke, W.A., Cuijpers, I., Heymans, S., Hamdani, N., de Boer, M., Duncker, D.J., Kuster, D., van der Velden, J., Beauloye, C., Bertrand, L., Mayr, M., Giacca, M., Leuschner, F., Backs, J., Thum, T. Towards standardization of echocardiography for the evaluation of left ventricular function in adult rodents: a position paper of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Cardiovasc Res. 2021 Jan 1;117(1):43-59. [CrossRef]

- IBB CNR Vevo 2100 manual. Available online: https://www.ibb.cnr.it/img/Vevo2100-manual.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Foppa, M., Duncan, B.B., Rohde, L.E. Echocardiography-based left ventricular mass estimation. How should we define hypertrophy? Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2005 Jun 17;3:17. [CrossRef]

- Hubesch, G., Hanthazi, A., Acheampong, A., Chomette, L., Lasolle, H., Hupkens, E., Jespers, P., Vegh, G., Wembonyama, C.W.M., Verhoeven, C., Dewachter, C., Vachiery, J.L., Entee, K.M., Dewachter, L. A Preclinical Rat Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction With Multiple Comorbidities. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Jan 13;8:809885. [CrossRef]

- Hagdorn, Q.A.J., Bossers, G.P.L., Koop, A.C., Piek, A., Eijgenraam, T.R., van der Feen, D.E., Silljé, H.H.W., de Boer, R.A., Berger, R.M.F. A novel method optimizing the normalization of cardiac parameters in small animal models: the importance of dimensional indexing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019 Jun 1;316(6):H1552-H1557. [CrossRef]

- Mancini M, Prinster A, Annuzzi G, Liuzzi R, Giacco R, Medagli C, Cremone M, Clemente G, Maurea S, Riccardi G, Rivellese AA, Salvatore M. Sonographic hepatic-renal ratio as indicator of hepatic steatosis: comparison with (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metabolism. 2009 Dec;58(12):1724-30. Epub 2009 Aug 28. [CrossRef]

- Pagliuca C, Cicatiello AG, Colicchio R, et al. Novel Approach for Evaluation of Bacteroides fragilis Protective Role against Bartonella henselae Liver Damage in Immunocompromised Murine Model. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7:1750. [CrossRef]

- Lessa, A.S., Paredes, B.D., Dias, J.V., Carvalho, A.B., Quintanilha, L.F., Takiya, C.M., Tura, B.R., Rezende, G.F., Campos de Carvalho, A.C., Resende, C.M., Goldenberg, R.C. Ultrasound imaging in an experimental model of fatty liver disease and cirrhosis in rats. BMC Vet Res. 2010 Jan 29;6:6. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.C., Sultan, L.R., Hunt, S.J., Schultz, S.M., Brice, A.K., Wood, A.K.W., Sehgal, C.M. B-mode ultrasound for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis: a quantitative multiparametric analysis for a radiomics approach. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 8708. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, M.C.R., de Campos Vettorato, M., Fogaça, J.L., Puoli Filho, J.N.P., de Vasconcelos Machado, V.M. Quantitative Ultrasound of Kidneys, Liver, and Spleen: a Comparison Between Mules and Horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, Volume 70, 2018, Pages 71-75, ISSN 0737-0806. [CrossRef]

- Beland, M.D., Walle, N.L., Machan, J.T., Cronan, J.J. Renal cortical thickness measured at ultrasound: is it better than renal length as an indicator of renal function in chronic kidney disease? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Aug;195(2):W146-9. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, N.C., Rebelo, M.A.P., da Silveira Rioja, L. et al. Sonographically determined kidney measurements are better able to predict histological changes and a low CKD-EPI eGFR when weighted towards cortical echogenicity. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 123. [CrossRef]

- Xu. H., Ma, Z., Lu, S., Li, R., Lyu, L., Ding, L., Lu, Q. Renal Resistive Index as a Novel Indicator for Renal Complications in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42(6):1128-1140. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., Lu, S., Ding, L., Lu, Q. Renal resistive index in mouse model. Exp Tech Urol Nephrol. 2018, 1(4). ETUN.000522.2018. [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, A.A.A., Sharara, S.M., Nanda, A., Khouzam, R.N. The renal resistive index as a new complementary tool to predict microvascular diabetic complications in children and adolescents: a groundbreaking finding. Ann Transl Med. 2019 Sep;7(17):422. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S., Fuchs, D., and Meier, M. Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Imaging of the Kidney: Basic Concepts and Protocols. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021. 2216, 109–130. [CrossRef]

- Cauwenberghs, N., Kuznetsova, T. Determinants and Prognostic Significance of the Renal Resistive Index. Pulse (Basel). 2016 Apr;3(3-4):172-8. [CrossRef]

- Tublin, M., Bude, R., Platt, J. The resistive index in renal Doppler sonography: where do we stand? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003. 180: 885–892. [CrossRef]

- Lubas, A., Kade, G., Niemczyk, S. Renal resistive index as a marker of vascular damage in cardiovascular diseases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014 Feb;46(2):395-402. [CrossRef]

- K C, T., Das, S.K., Shetty, M.S. Renal Resistive Index: Revisited. Cureus. 2023 Mar 13;15(3):e36091. [CrossRef]

- Westergren, H.U., Grönros, J., Heinonen, S.E., Miliotis, T., Jennbacken, K., Sabirsh, A., Ericsson, A., Jönsson-Rylander, A.C., Svedlund, S., Gan, L.M. Impaired Coronary and Renal Vascular Function in Spontaneously Type 2 Diabetic Leptin-Deficient Mice. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 22;10(6):e0130648. [CrossRef]

- Faita, F., Di Lascio, N., Rossi, C., Kusmic, C., Solini, A. Ultrasonographic Characterization of the db/db Mouse: An Animal Model of Metabolic Abnormalities. J Diabetes Res. 2018 Mar 8;2018:4561309. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E., Brunt, E.M., Van Natta, M., Behling, C., Contos, M.J., Cummings, O.W., Ferrell, L.D., Liu, Y.C., Torbenson, M.S., Unalp-Arida, A., Yeh, M., McCullough, A.J., Sanyal, A.J. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005 Jun;41(6):1313-21. [CrossRef]

- Barone, V., Borghini, A., Tedone, C. E., Aglianò, M., Gabriele, G., Gennaro, P., Weber, E. New Insights into the Pathophysiology of Primary and Secondary Lymphedema: Histopathological Studies on Human Lymphatic Collecting Vessels. Lymphat Res Biol. 2020, ISSN: 1539-6851. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W., Menke, A.L., Driessen, A., Koek, G.H., Lindeman, J.H., Stoop, R., Havekes, L.M., Kleemann, R., van den Hoek, A.M. Establishment of a general NAFLD scoring system for rodent models and comparison to human liver pathology. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 23;9(12):e115922. [CrossRef]

- Bedossa, P., FLIP Pathology Consortium. Utility and appropriateness of the fatty liver inhibition of progression (FLIP) algorithm and steatosis, activity, and fibrosis (SAF) score in the evaluation of biopsies of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2014 Aug;60(2):565-575. [CrossRef]

- Glastras, S.J., Chen, H., The, R., McGrath, R.T., Chen, J., Pollock, C.A., Wong, M.G., Saad, S. Mouse Models of Diabetes, Obesity and Related Kidney Disease. PLoS One. 2016 Aug 31;11(8):e0162131. [CrossRef]

- Søgaard, S.B., Andersen, S.B., Taghavi, I., Schou, M., Christoffersen, C., Jacobsen, J.C.B., Kjer, H.M., Gundlach, C., McDermott, A., Jensen, J.A., Nielsen, M.B., Sørensen, C.M. Super-Resolution Ultrasound Imaging of Renal Vascular Alterations in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats during the Development of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Oct 12;13(20):3197. [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C., Cihan, M., Yücel, D., Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2021 Feb 15;31(1):010502. [CrossRef]

- Weber, C. Diet effects on stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2021 Aug;23(8):811. [CrossRef]

- Sargent, J.L., Koewler, N.J., Diggs, H.E. Systematic Literature Review of Risk Factors and Treatments for Ulcerative Dermatitis in C57BL/6 Mice. Comp Med. 2015 Dec;65(6):465-72.

- De Biase, D., Esposito, F., De Martino, M., Pirozzi, C., Luciano, A., Palma, G., Raso, G.M., Iovane, V., Marzocco, S., Fusco, A., Paciello, O. Characterization of inflammatory infiltrate of ulcerative dermatitis in C57BL/6NCrl-Tg(HMGA1P6)1Pg mice. Lab Anim. 2019 Oct;53(5):447-458. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.M., Speakman, J.R. The extent and function of ‘food grinding’ in the laboratory mouse (Mus musculus). Lab Anim. 2010 Oct;44(4):298-304. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett-Corning, K.R., Keefe, R., Garner, J.P., Gaskill, B.N. Can seeds help mice with the daily grind? Lab Anim. 2013 Oct;47(4):312-5. [CrossRef]

- Charles River online resource library. Available online: https://www.criver.com/products-services/find-model/c57bl6j-mice-jax-strain?region=27 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Gargiulo, S., Gramanzini, M., Megna, R., Greco, A., Albanese, S., Manfredi, C., Brunetti, A. Evaluation of growth patterns and body composition in C57Bl/6J mice using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:253067. [CrossRef]

- Breslin, W.L., Strohacker, K., Carpenter, K.C., Esposito, L., Mcfarlin, B.K. Weight gain in response to high-fat feeding in CD-1 male mice. Laboratory Animals. 2010;44(3):231-237. [CrossRef]

- Siriarchavatana, P., C. Kruger, M., M.Wolber, F. Correlation between body condition score and body composition in a rat model for obesity research. Veterinary Integrative Sciences. 2022;20(3), 531–545. [CrossRef]

- Keirns, B. H., Sciarrillo, C. M., Koemel, N. A., Emerson, S.R. Fasting, non-fasting and postprandial triglycerides for screening cardiometabolic risk. J Nutr Sci. 2021 Sep 14;10:e75. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., An, Z., Hou, X., Guan, Y., Song, G. A bibliometric analysis and visualization of literature on non-fasting lipid research from 2012 to 2022. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Apr 19;14:1136048. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, A. M., Shi, L. J., Lee, R. N., Chen, M.-H., Shi, W. Phenotypic and Genetic Evidence for a More Prominent Role of Blood Glucose than Cholesterol in Atherosclerosis of Hyperlipidemic Mice. Cells. 2022; 11(17):2669. [CrossRef]

- Eisinger, K., Liebisch, G., Schmitz, G., Aslanidis, C., Krautbauer, S., Buechler, C. Int J Mol Sci. 2014 Feb 20;15(2):2991-3002. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.M., Tu, Y., Beigneux, A.P., Davies, B.S., Gin, P., Voss, C., Walzem, R.L., Reue, K., Tontonoz, P., Bensadoun, A., Fong, L.G., Young, S.G. Cholesterol intake modulates plasma triglyceride levels in glycosylphosphatidylinositol HDL-binding protein 1-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010 Nov;30(11):2106-13. [CrossRef]

- Mekada, K., Yoshiki, A. Substrains matter in phenotyping of C57BL/6 mice. Exp Anim. 2021 May 13;70(2):145-160. [CrossRef]

- Otto, G.P., Rathkolb, B., Oestereicher, M.A., Lengger, C.J., Moerth, C., Micklich, K., Fuchs, H., Gailus-Durner, V., Wolf, E., Hrabě de Angelis, M. Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for C57BL/6J, C57BL/6N, and C3HeB/FeJ Mice (Mus musculus). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2016;55(4):375-86.

- Toita, R., Kawano, T., Fujita, S., Murata, M., Kang, J.H. Increased hepatic inflammation in a normal-weight mouse after long-term high-fat diet feeding. J Toxicol Pathol. 2018 Jan;31(1):43-47. [CrossRef]

- Quesenberry, K. E., & Carpenter, J. W. Ferrets, rabbits, and rodents: clinical medicine and surgery: includes sugar gliders and hedgehogs. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo., Saunders, 2004; p 290.

- Hosten, A.O. BUN and Creatinine. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 193. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305/.

- Wang, K., Peng, X., Yang, A., Huang, Y., Tan, Y., Qian, Y., Lv, F., Si, H. Effects of Diets With Different Protein Levels on Lipid Metabolism and Gut Microbes in the Host of Different Genders. Front Nutr. 2022 Jun 15;9:940217. [CrossRef]

- Imamura, Y., Mawatari, S., Oda, K., Kumagai, K., Hiramine, Y., Saishoji, A., Kakihara, A., Nakahara, M., Oku, M., Hosoyamada, K., Kanmura, S., Moriuchi, A., Miyahara, H., Akio, Ido. Changes in body composition and low blood urea nitrogen level related to an increase in the prevalence of fatty liver over 20 years: A cross-sectional study. Hepatol Res. 2021 May;51(5):570-579. [CrossRef]

- Thoolen, B., Maronpot, R.R., Harada, T., Nyska, A., Rousseaux, C., Nolte, T., Malarkey, D.E., Kaufmann, W., Küttler, K., Deschl, U., Nakae, D., Gregson, R., Vinlove, M.P., Brix, A.E., Singh, B., Belpoggi, F., Ward, J.M. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol Pathol. 2010 Dec;38(7 Suppl):5S-81S. [CrossRef]

- Löwen, J., Gröne, E.F., Groß-Weißmann, M.L., Bestvater, F., Gröne, H.J., Kriz, W. Pathomorphological sequence of nephron loss in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021 Nov 1;321(5):F600-F616. Epub 2021 Sep 20. Erratum in: Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2022 Mar 1;322(3):F308. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00669.2020_COR. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, C.R., Leite, A.P.O., Yokota, R., Pereira, R.O., Americo, A.L.V., Nascimento, N.R.F., Evangelista, F.S., Farah, V., Fonteles, M.C., Fiorino, P. Post-weaning Exposure to High-Fat Diet Induces Kidney Lipid Accumulation and Function Impairment in Adult Rats. Front Nutr. 2019 May 3;6:60. [CrossRef]

- Prem, P.N., Kurian, G.A. High-Fat Diet Increased Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat. Front Physiol. 2021 Sep 3;12:715693. [CrossRef]

- Hoffler, U., Hobbie, K., Wilson, R., Bai, R., Rahman, A., Malarkey, D., Travlos, G., Ghanayem, B.I. Diet-induced obesity is associated with hyperleptinemia, hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and glomerulopathy in C57Bl/6J mice. Endocrine. 2009 Oct;36(2):311-25. [CrossRef]

- Oraha, J., Enriquez, R.F., Herzog, H. et al. Sex-specific changes in metabolism during the transition from chow to high-fat diet feeding are abolished in response to dieting in C57BL/6J mice. Int J Obes 46, 1749–1758 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.K., Carley, A.N., Maurya, C.K., Lewandowski, E.D. Western Diet Causes Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Metabolic Shifts After Diastolic Dysfunction and Novel Cardiac Lipid Derangements. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023 Jan 25;8(4):422-435. Erratum in: JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023 Jun 26;8(6):753. 10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.04.007. [CrossRef]

- Withaar, C., Lam, C.S.P., Schiattarella, G.G., de Boer, R.A., Meems, L.M.G. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in humans and mice: embracing clinical complexity in mouse models. Eur Heart J. 2021 Nov 14;42(43):4420-4430. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2022 May 21;43(20):1940. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab883. [CrossRef]

- Grabysa, R., Wańkowicz, Z. Echocardiographic markers of left ventricular dysfunction among men with uncontrolled hypertension and stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Med Sci Monit. 2013 Oct 9;19:838-45. [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M., Luisi, G.A., Pastore, M.C. et al. New perspectives in the echocardiographic hemodynamics multiparametric assessment of patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 29, 799–809 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, I.F., Lin, T.C., Wang, S.C., Yen, C.H., Li, C.Y., Kuo, H.F., Hsieh, C.C., Chang, C.Y., Chang, C.R., Chen, Y.H., Liu, Y.R., Lee, T.Y., Huang, C.Y., Hsu, C.H., Lin, S.J., Liu, P.L. Long-term administration of Western diet induced metabolic syndrome in mice and causes cardiac microvascular dysfunction, cardiomyocyte mitochondrial damage, and cardiac remodeling involving caveolae and caveolin-1 expression. Biol Direct. 2023 Mar 6;18(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Milhem, F.; Hamilton, L.M.; Skates, E.; Wilson, M.; Johanningsmeier, S.D.; Komarnytsky, S. Biomarkers of Metabolic Adaptation to High Dietary Fats in a Mouse Model of Obesity Resistance. Metabolites 2024, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadori, P., Weiskirchen, R., Trebicka, J., Streetz, K. Mouse models of metabolic liver injury. Lab Anim. 2015 Apr;49(1 Suppl):47-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, R.K., Kadatz, M., Rohling, R., Nguan, C. Kidney Ultrasound for Nephrologists: A Review. Kidney Med. 2022 Apr 7;4(6):100464. [CrossRef]

- Darabont, R., Mihalcea, D., Vinereanu, D. Current Insights into the Significance of the Renal Resistive Index in Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 May 10;13(10):1687. [CrossRef]

- Sowers, J.R., Whaley-Connell, A., Hayden, M.R. The Role of Overweight and Obesity in the Cardiorenal Syndrome. Cardiorenal Med. 2011;1(1):5-12. [CrossRef]

- Whaley-Connell, A., Pulakat, L., DeMarco, V.G., Hayden, M.R., Habibi, J., Henriksen, E.J., Sowers, J.R. Overnutrition and the Cardiorenal Syndrome: Use of a Rodent Model to Examine Mechanisms. Cardiorenal Med. 2011;1(1):23-30. [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, T., Pardal, M.A.E., Herdy, S.A., Muzi-Filho, H., Mello, D.B., Takiya, C.M., Luzes, R., Vieyra, A. Liver steatosis, cardiac and renal fibrosis, and hypertension in overweight rats: Angiotensin-(3-4)-sensitive hepatocardiorenal syndrome. Metabol Open. 2022 Mar 18;14:100176. [CrossRef]

- Aroor, A.R., Habibi, J., Nistala, R., Ramirez-Perez, F.I., Martinez-Lemus, L.A, Jaffe, I.Z., Sowers, J.R., Jia, G., Whaley-Connell, A. Diet-Induced Obesity Promotes Kidney Endothelial Stiffening and Fibrosis Dependent on the Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Hypertension. 2019 Apr;73(4):849-858. [CrossRef]

- Hoi, S., Takata, T., Sugihara, T., Ida, A., Ogawa, M., Mae, Y., Fukuda, S., Munemura, C., Isomoto, H. Predictive Value of Cortical Thickness Measured by Ultrasonography for Renal Impairment: A Longitudinal Study in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med. 2018 Dec 7;7(12):527. [CrossRef]

- Murawski, I.J., Maina, R.W., Gupta, I.R. The relationship between nephron number, kidney size and body weight in two inbred mouse strains. Organogenesis. 2010 Jul-Sep;6(3):189-94. [CrossRef]

| Age (weeks) | Groups | IVS/LVAW; d (mm) |

IVS/LVAW; s (mm) |

LVID; d (mm) |

LVID; s (mm) |

LVPW;d (mm) | LVPW;s (mm) | LV mass corr (mg) | LV vol; d (uL) |

LV vol; s (uL) | LV SV (uL) | HR (bpm) | LV CO (ml/min) | EF (%) | FS (%) | RWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | ♂ SD | 0.126± 0.020 | 0.175± 0.028 | 0.461± 0.037 | 0.333± 0.036 | 0.129± 0.027 | 0.175± 0.025 | 4.446± 0.755 | 2.277± 0.381 | 1.04± 0.279 | 1.234± 0.195 | 497.71±52.29 | 0.61± 0.13 | 54.67± 6.68 | 27.78± 4.17 | 0.557± 0.107 |

| ♂ WD | 0.095± 0.014 | 0.14± 0.023 | 0.48± 0.069 | 0.33± 0.054 | 0.104± 0.012 | 0.147± 0.021 | 3.42± 0.83 | 2.60± 0.83 | 1.03± 0.39 | 1.56± 0.61 | 499.2±25.45 | 0.77± 0.29 | 59.70± 10.01 | 31.49± 6.82 | 0.42± 0.08 | |

| 16 | ♂ SD | 0.112± 0.011 | 0.152± 0.017 | 0.347± 0.034 | 0.254± 0.018 | 0.123± 0.015 | 0.150± 0.023 | 4.19± 0.45 | 1.63± 0.32 | 0.75± 0.10 | 0.87± 0.35 | 484.28±42.14 | 0.43± 0.17 | 51.87± 13.26 | 26.34± 8.10 | 0.68± 0.12 |

| ♂ WD | 0.094± 0.015 | 0.14± 0.016 | 0.35± 0.060 | 0.23± 0.058 | 0.097± 0.015 | 0.130± 0.017 | 4.20± 1.13 | 2.15± 0.85 | 0.83± 0.46 | 1.32± 0.49 | 420.7±36.12 | 0.54± 0.16 | 63.04± 10.22 | 34.10± 7.21 | 0.54± 0.11 | |

| 24 | ♂ SD | 0.120± 0.013 | 0.159± 0.007 | 0.330± 0.035 | 0.23± 0.040 | 0.116± 0.017 | 0.146± 0.012 | 4.46± 0,69 | 1.57 ± 0.39 | 0.73± 0.30 | 0.84± 0.19 | 501.42±45.06 | 0.42± 0.10 | 54.41± 10.02 | 27.73± 6.36 | 0.73± 0.14 |

| ♂ WD | 0.092± 0.012 | 0.12± 0.019 | 0.32± 0.064 | 0.22± 0.076 | 0.088± 0.012 | 0.125± 0.034 | 3.75± 0.90 | 1.80± 0.71 | 0.86± 0.62 | 0.94± 0.24 | 500.8±46.25 | 0.47± 0.12 | 56.08± 17.84 | 30.23± 13.40 | 0.58± 0.12 | |

| 8 | ♀ SD | 0.141± 0.012 | 0.183± 0.028 | 0.541± 0.036 | 0.419± 0.057 | 0.137± 0.013 | 0.167± 0.025 | 4.44± 0.44 | 2.56± 0.40 | 1.39± 0.44 | 1.17± 0.47 | 498.5±38.58 | 0.58± 0.24 | 45.35± 15.57 | 22.52± 8.78 | 0.51± 0.055 |

| ♀ WD | 0.115± 0.021 | 0.173± 0.022 | 0.61± 0.084 | 0.43± 0.082 | 0.135± 0.017 | 0.190± 0.027 | 3.85± 0.92 | 3.06± 0.81 | 1.32± 0.55 | 1.73± 0.35 | 389.6±36.95 | 0.67± 0.14 | 57.77± 7.81 | 29.91± 5.39 | 0.41± 0.08 | |

| 16 | ♀ SD | 0.119± 0.015 | 0.176± 0.013 | 0.471± 0.032 |

0.31± 0.029 | 0.131± 0.014 | 0.182± 0.021 | 4.41± 0.52 | 2.36± 0.34 | 0.93± 0.17 | 1.43± 0.34 | 471.87±42.60 | 0.68± 0.18 | 60.20± 8.29 | 31,66± 5.75 | 0.53± 0.08 |

| ♀ WD | 0.126± 0.018 | 0.174± 0.029 | 0.447± 0.027 | 0.322± 0.051 | 0.146± 0.029 | 0.176± 0.028 | 4.31± 0.96 | 1.99± 0.38 | 0.92± 0.38 | 1.07± 0.14 | 362.12±75.27 | 0.39± 0.10 | 55.28± 11.57 | 28.32± 7.33 | 0.61± 0.12 | |

| 24 | ♀ SD | 0.139± 0.014 | 0.186± 0.017 | 0.38± 0.030 | 0.25± 0.019 | 0.144± 0.024 | 0.190± 0.008 | 4.52± 0.43 | 1.61± 0.32 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 1.01± 0.39 | 486±31.88 | 0.49± 0.19 | 61.26± 12.42 | 32.50± 9.00 | 0.75± 0.15 |

| ♀ WD | 0.114± 0.023 | 0.168± 0.035 | 0.387± 0.024 | 0.267± 0.042 | 0.135± 0.040 | 0.180± 0.051 | 4.21± 1.03 | 1.77± 0.26 | 0.75± 0.31 | 0.72± 0.30 | 407.2±38.39 | 0,29± 0,12 | 59.11± 13.05 | 31.17± 9.02 | 0.64± 0.13# | |

| US findings/Time of experiment | SD ♂ mice | WD ♂ mice | ||||

| 8 weeks (n=7) |

16 weeks (n=7) |

24 weeks (n=7) |

8 weeks (n=8) |

16 weeks (n=8) |

24 weeks (n=8) |

|

| Homogeneous liver parenchyma of medium level echogenicity | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Diffusely increased parenchymal echogenicity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Discrete coarsened and heterogeneous parenchyma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Extensive coarsened and heterogeneous parenchyma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| L-Echo<R-Echo | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| L-Echo=R-Echo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| L-Echo>R-Echo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Presence of Ascites | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SD ♀ mice | WD ♀ mice | |||||

| 8 weeks (n=8) |

16 weeks (n=8) |

24 weeks (n=8) |

8 weeks (n=8) |

16 weeks (n=8) |

24 weeks (n=8) |

|

| Homogeneous liver parenchyma of medium level echogenicity (pattern 1) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Diffusely increased parenchymal echogenicity (pattern 2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 |

| Discrete coarsened and heterogeneous parenchyma (pattern 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Extensive coarsened and heterogeneous parenchyma (pattern 4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L-Echo<R-Echo | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 |

| L-Echo=R-Echo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| L-Echo>R-Echo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Presence of Ascites | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Histological features scoring system | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAF score grading: percentage of the total area affected | NAFLD score grading: percentage of the total area affected | Fibrosis score grading: qualitative/semiquantitative visual evaluation | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | absent | mild | moderate | severe | |

| SD♂ mice (n=7) | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WD♂ mice(n=8) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| SD♀ mice (n=8) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WD♀ mice (n=8) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Histological features scoring system | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal score grading: percentage of the glomeruli altered | Bowman’s capsule and space score grading: percentage of the glomeruli with narrowed/collapsed Bowman’s space | ||||||||||||||

| 0 (<30%) |

1 (30-70%) |

2 (>70%) |

0% | 1-5% | 6-10% | 11-15% | 19-20% | 21-25% | 26-30% | 31-40% | 41-50% | 51-60% | 61-70% | >70% | |

| SD♂ mice (n=7) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WD♂ mice(n=7)* | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| SD♀ mice (n=8) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| WD♀ mice (n=7)* | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).