Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

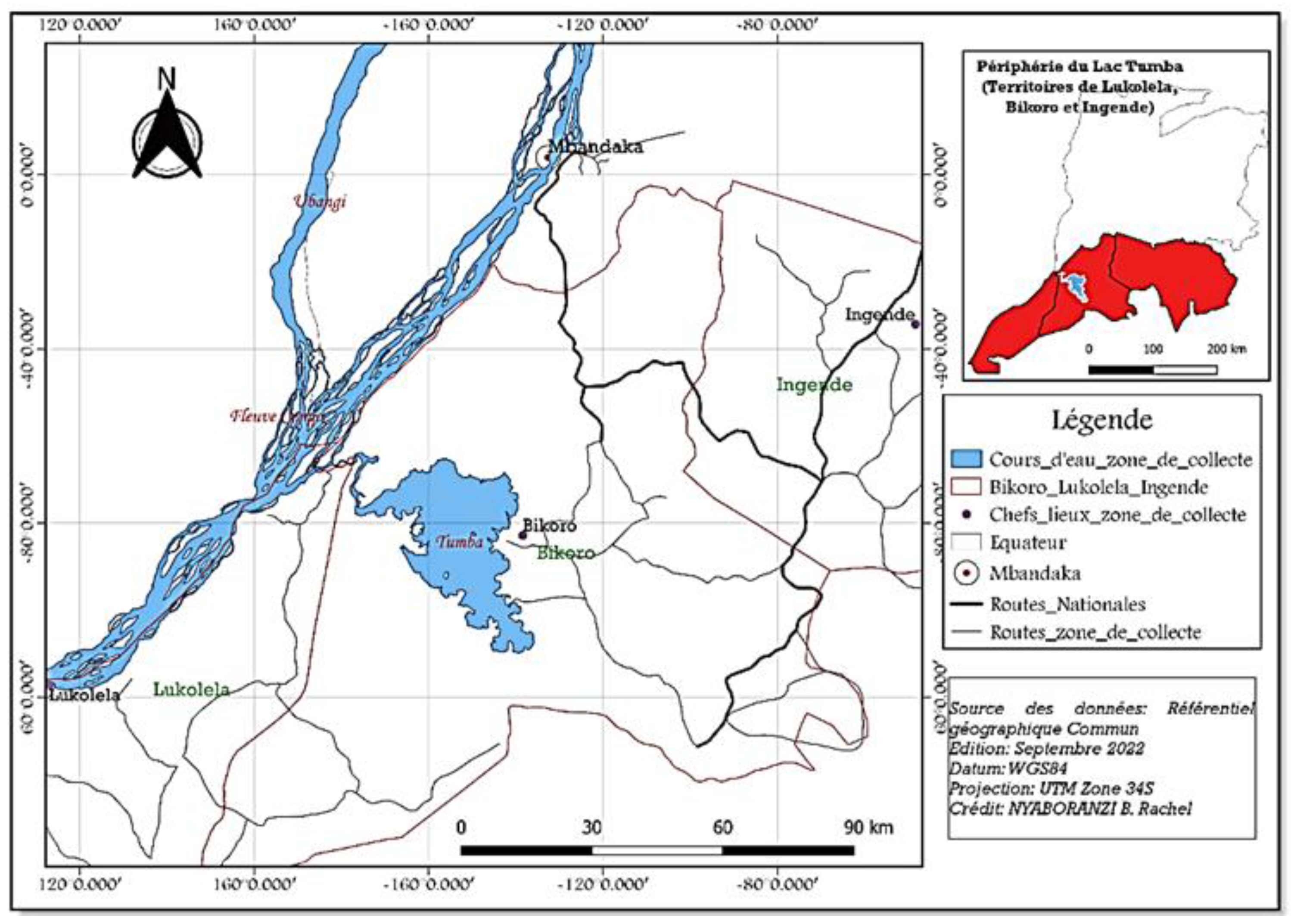

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Methodological Strategy

2.2.1. Choice of Sites, Territories, Villages, and Sample Size

2.2.2. Data Collection Technique

- Sociodemographic data

- Data on the integration of Indigenous knowledge

2.2.3. Data Analysis

2.2.4. Ethics and Results Validation

- -

- Free, prior, and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

- -

- Results were returned to the communities for validation through participatory feedback;

- -

- No protected species were destroyed or collected.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Respondents

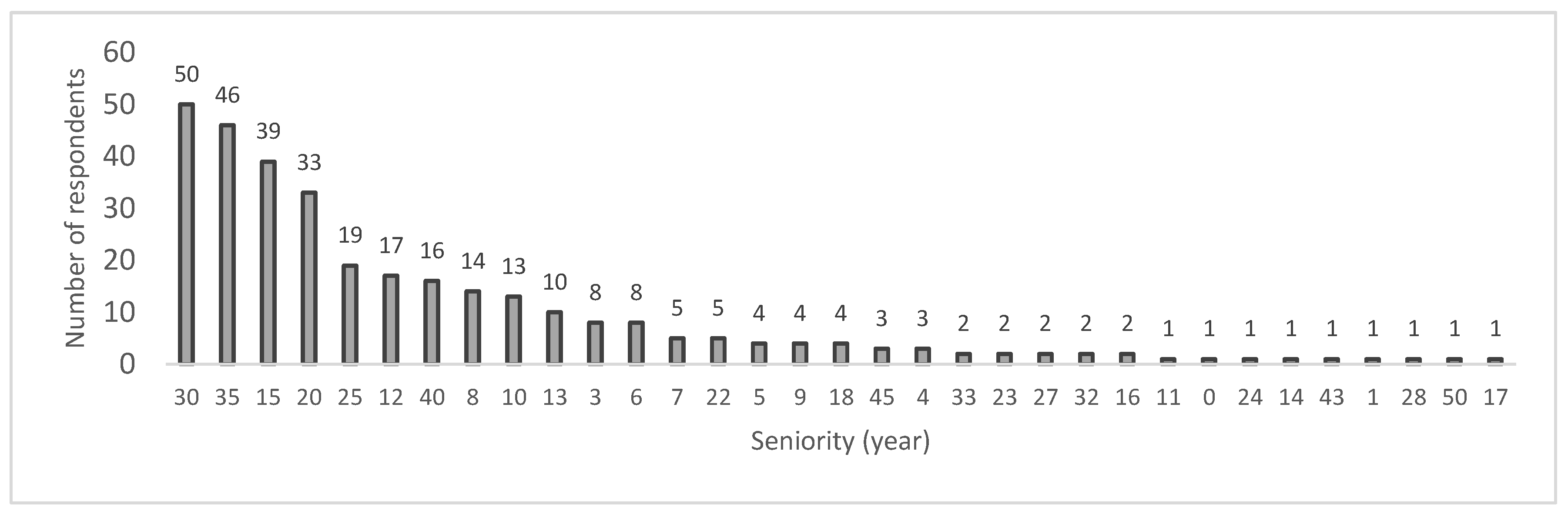

3.1.1. Seniority in the Practiced Activities

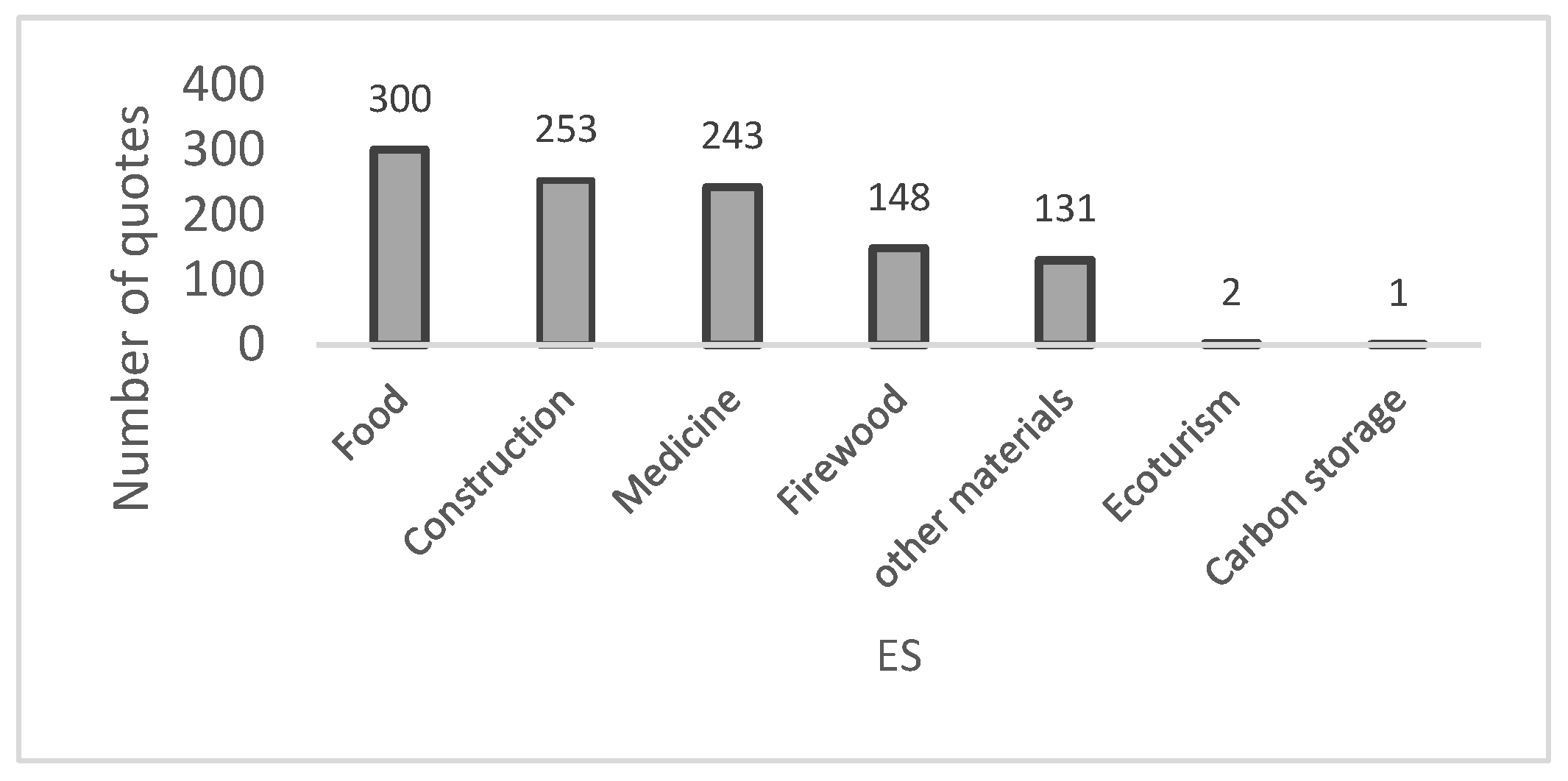

3.2. Peatlands’ Ecosystem Services (ES) Mentioned by LCs and IPs

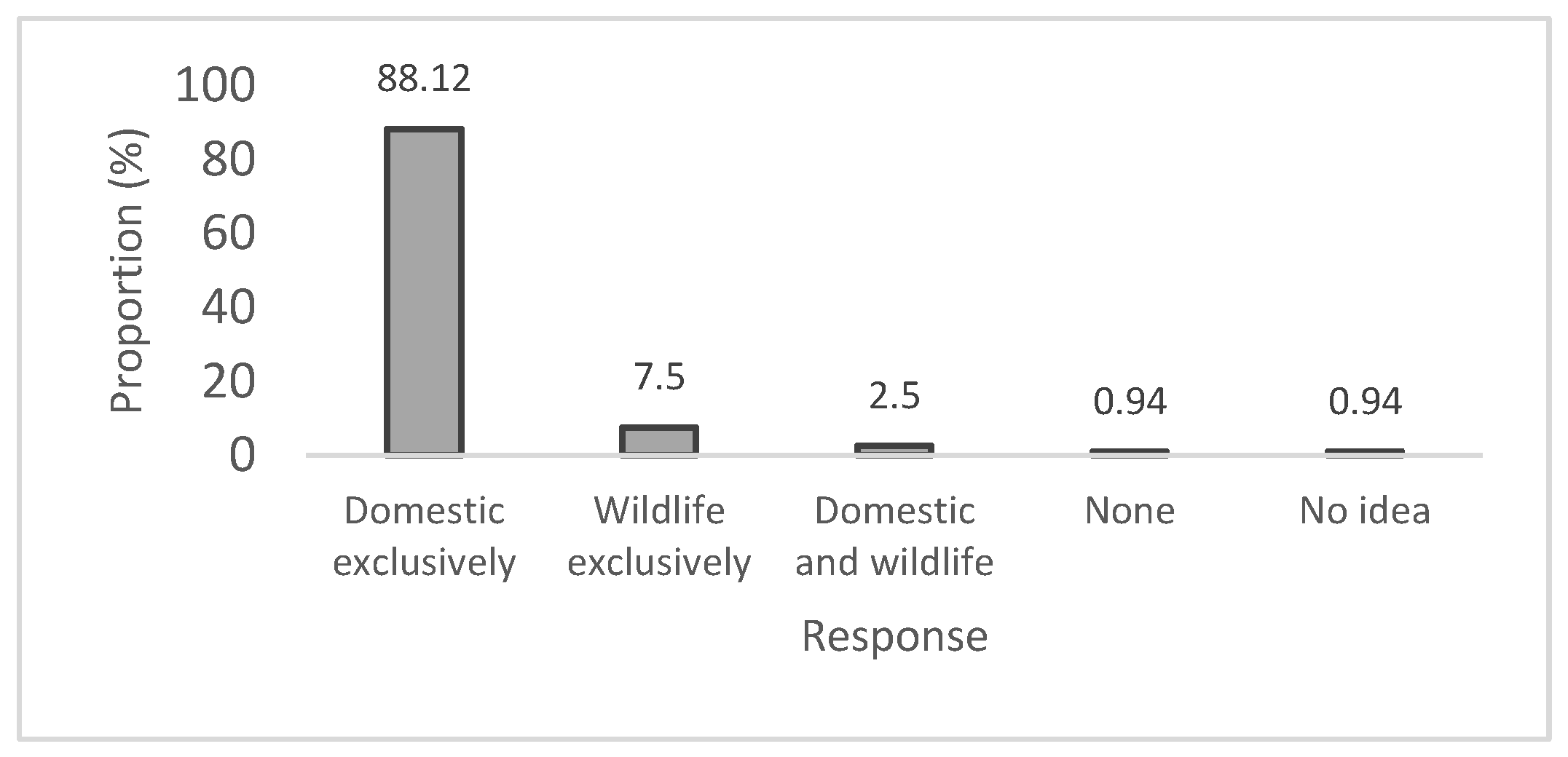

3.3. Traditional Practices and Indigenous Knowledge Related to Peatland Conservation

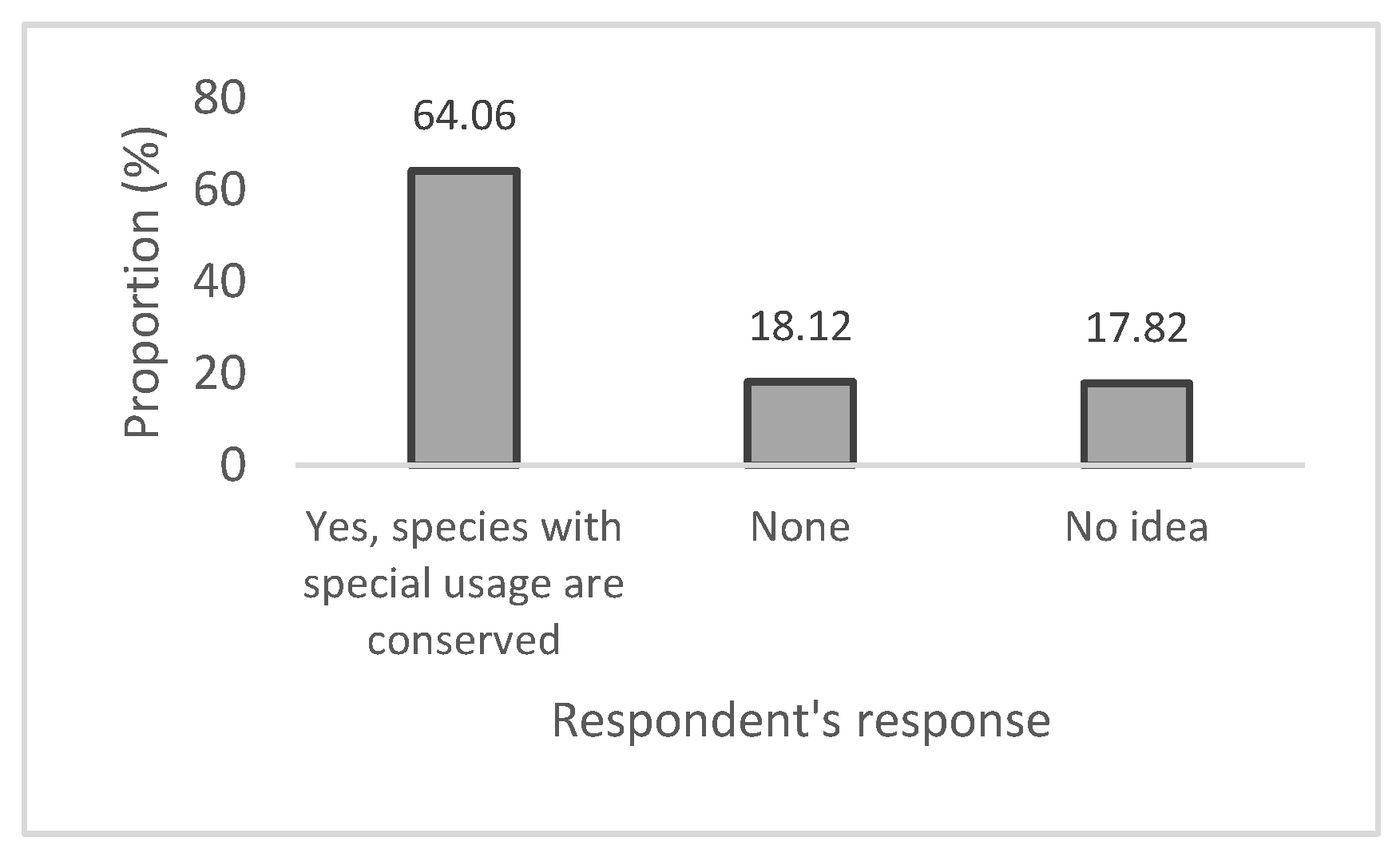

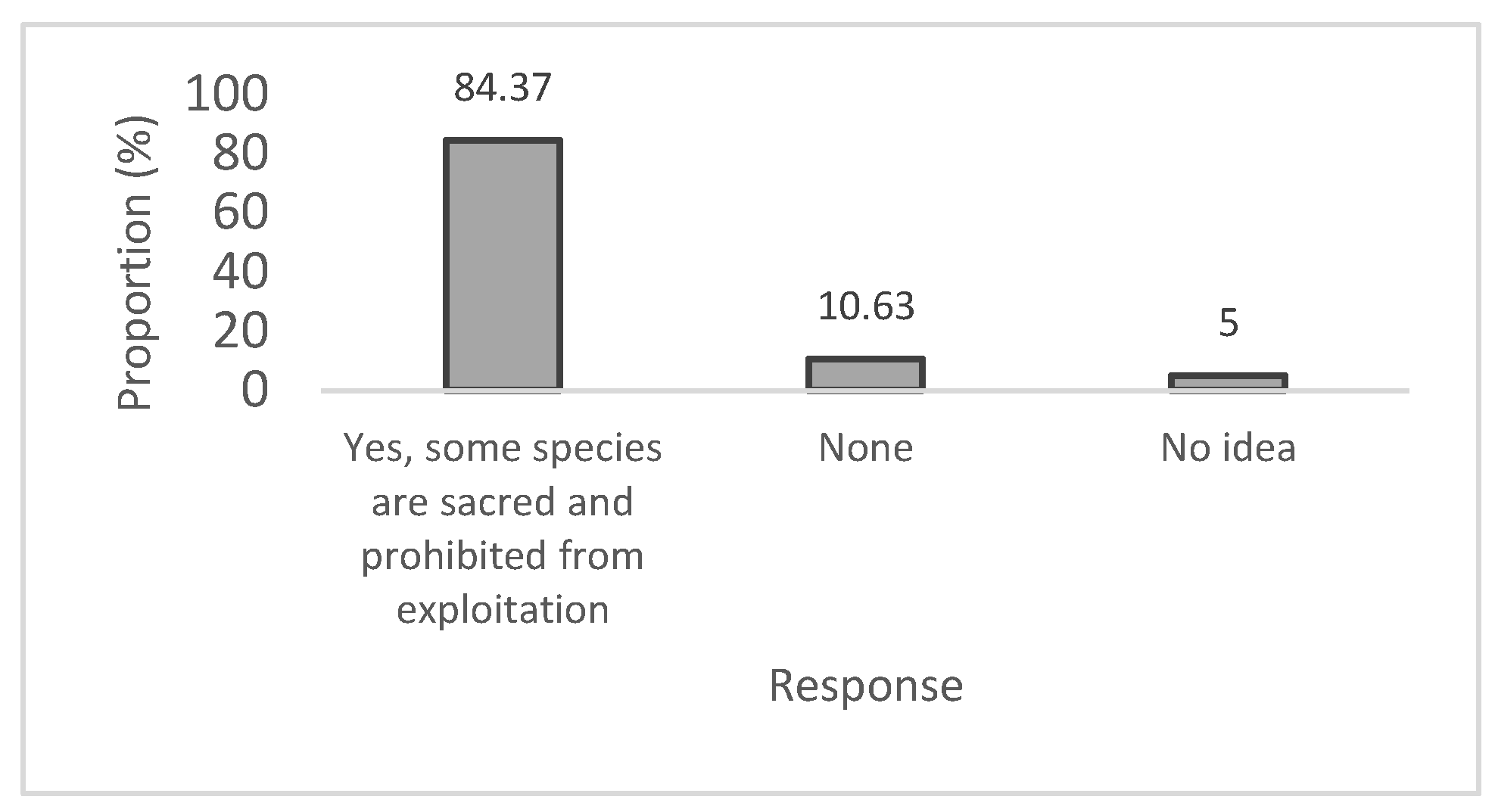

3.3.1. Traditional Perception/Belief Link to Plants and Animal Species Conservation

- Existence of plants and three species conserved for their special usage in yield increase.

- Existence of sacred plants and trees prohibited from exploitation or consumption

- Existence of animals used in traditional rites and beliefs to increase yields in hunting, fishing and agricultural activities.

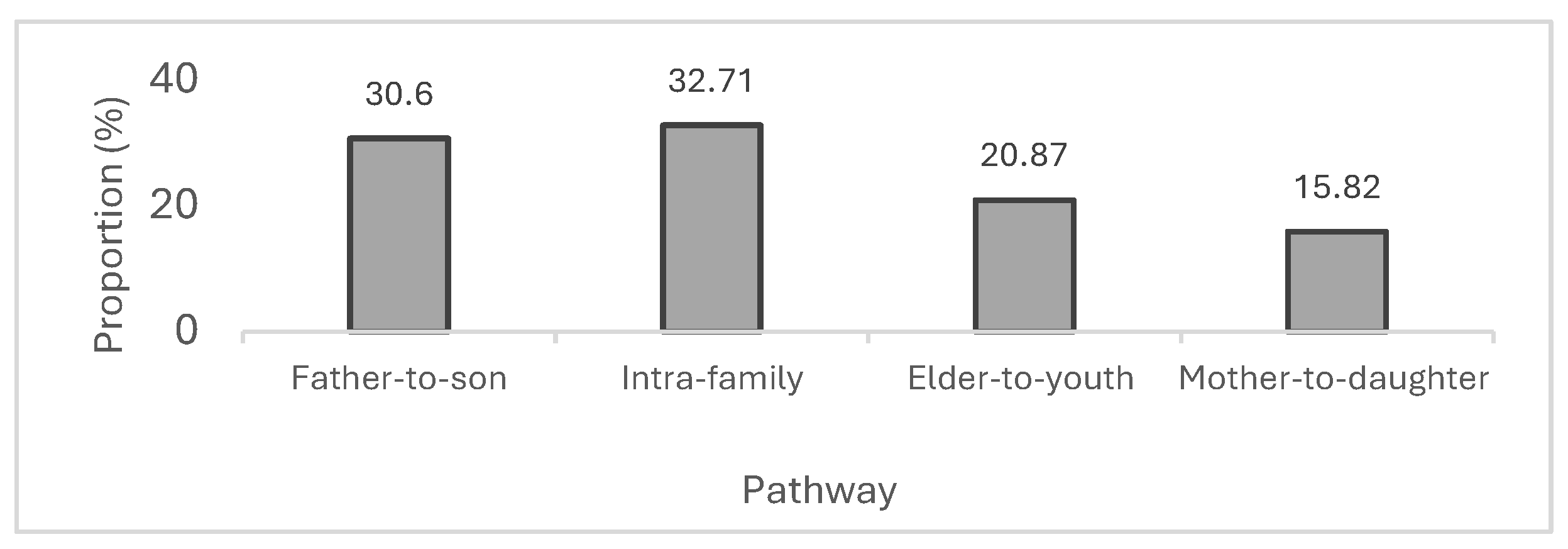

3.4. Intergenerational transmission pathways of traditional knowledge and practices

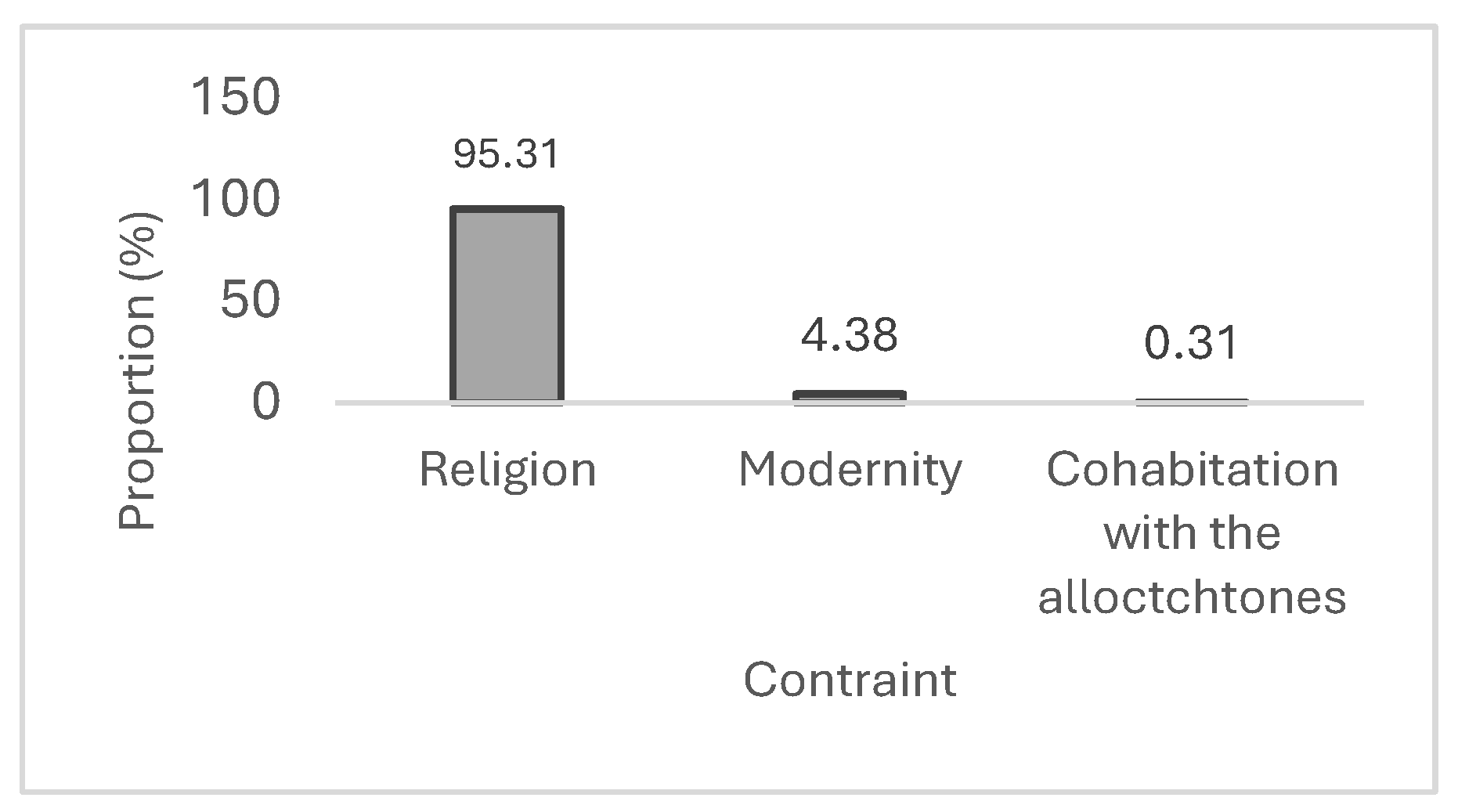

3.5. Constraints to the Intergenerational Transmission of Traditional Knowledge and Practices

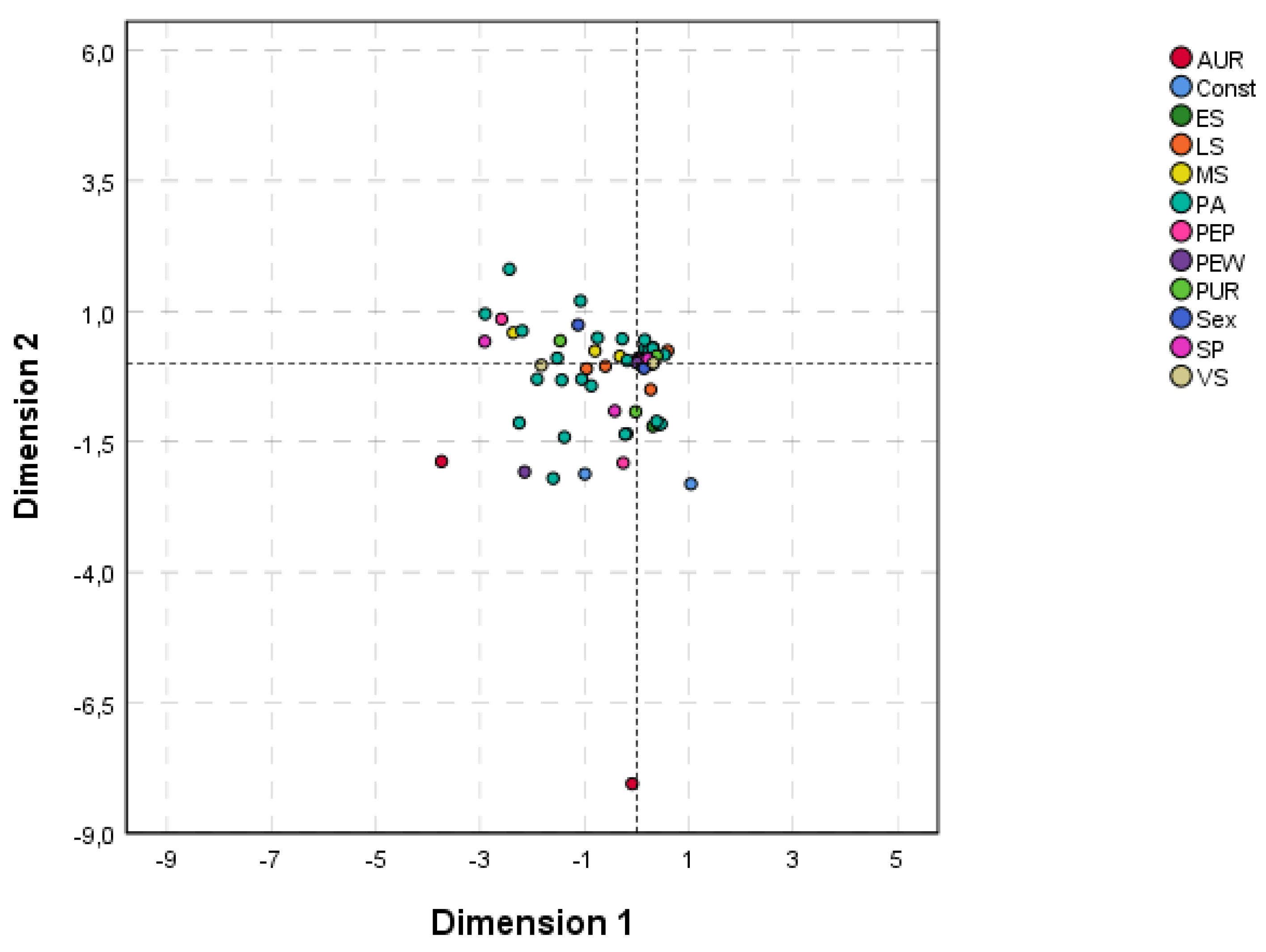

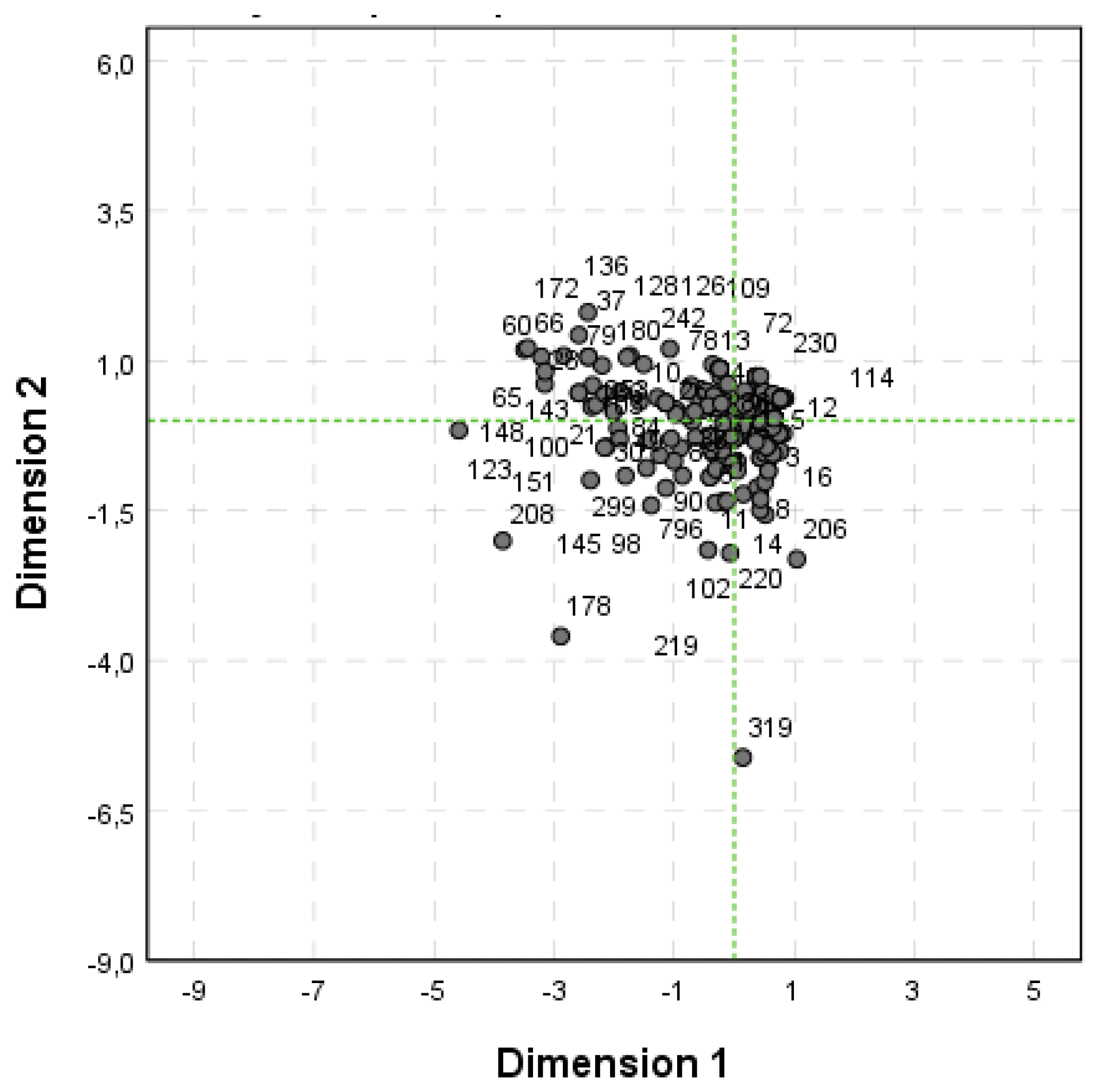

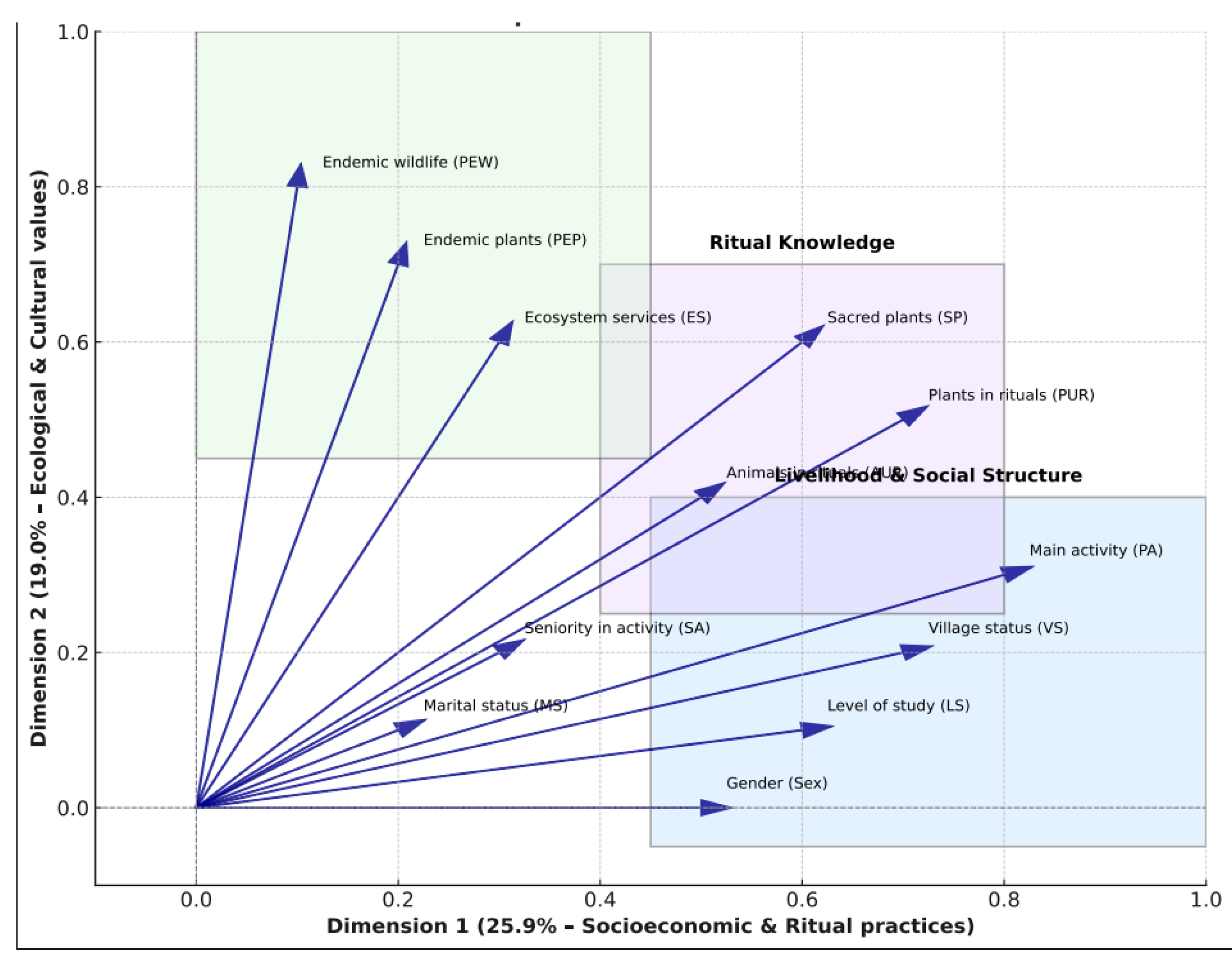

3.5.1. Associations Between the Variables and Among the Respondents

- Socio-demographics and livelihoods

- Livelihoods, biocultural practice, and biodiversity presence

- Cultural safeguards and constraints

- Non-associations (informative nulls)

4. Discussion

4.4. Disruption of Intergenerational Transmission

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- -

- Integrate traditional and Indigenous knowledge into Management Plans: Conservation strategies must actively document, respect, and integrate the existing traditional knowledge and practices that are compatible with peatland health. This includes recognizing and legally supporting communitybased governance systems that enforce taboos and sustainable practices.

- -

- Bridge the perception gap: Conservation education and outreach programs must be designed to explain the global importance of carbon storage and other regulating services in the context of local benefits. Demonstrating how intact peatlands ensure clean water, stable fish stocks, and flood prevention can align local and global interests [43].

- -

- Safeguard cultural transmission: Addressing the threat to knowledge transmission is perhaps the most complex challenge. Engaging with religious leaders to foster dialogue and find synergies between faith and environmental stewardship could be a potential pathway. Furthermore, supporting informal, communityled education where elders teach the young within their cultural framework is crucial.

- -

- Secure land tenure: The strong link between Indigenous village status and conservationoriented practices underscores the importance of securing land and resource rights for IPs and LCs. Secure tenure provides the stability needed for communities to continue their traditional stewardship practices [44].

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNEP. Global peatlands assessment – The state of the world’s peatlands: Evidence for action toward the conservation, restoration, and sustainable management of peatlands. UNEP 2022.

- Clarke, D.; Rieley, J.O. Strategy for responsible peatland management (6th ed.). International Peatland Society 2019.

- Dargie, G.C.; Lewis, S.L.; Lawson, I.T.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Page, S.E.; Bocko, Y.E.; Ifo, S.A. Age, extent and carbon storage of the central Congo Basin peatland complex. Nature 2017, 542, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crezee, B.; Dargie, G.C.; Ewango, C.E.N.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Emba, B.O.; Kanyama, T.J.; Bola, P.; ... & Lewis, S.L. Mapping peat thickness and carbon stocks of the Central Congo Basin using field data. Nature Geoscience 2022, 15, 639–644. [CrossRef]

- Garcin, Y.; Schefuß, E.; Dargie, G.C.; Hawthorne, D.; Lawson, I.T.; Sebag, D.; Biddulph, G.E.; ... & Lewis, S.L. Hydroclimatic vulnerability of peat carbon in the central Congo Basin. Nature 2022, 612, 277–282. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, I.T.; Honorio Coronado, E.N.; Andueza, L.; ... & Mitchard, E.T.A. The vulnerability of tropical peatlands to oil and gas exploration and extraction. Progress in Environmental Geography 2022, 1, 84–114. [CrossRef]

- Dargie, G.C.; Lawson, I.T.; Rayden, T.J.; Page, S.E.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Bocko, Y.E.; Ifo, S.A. Congo Basin peatlands: Threats and conservation priorities. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2018, 24, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonwa, D.; Bambuta, J.J.; Siewe, R.; Pongui, B. Framing the peatlands governance in the Congo Basin. CIFOR-ICRAF 2022.

- Congo Peat Consortium. Value and vulnerability of the central Congo Basin peatlands. UNEP-WCMC 2023.

- CIESIN. Gridded population of the world, version 4 (GPWv4): Population density (Revision 11), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Brncic, T.M.; Willis, K.J.; Harris, D.J.; Washington, R. Culture or climate? The relative influences of past processes on the composition of the lowland Congo rainforest. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2007, 362, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslisly, R.; Doutrelepont, H.; Fontugne, M.; ... & White, L. Premiers résultats pluridisciplinaires d’une stratigraphie vieille de plus de 40.000 ans du site de Maboué 5 dans la réserve de la Lopé au Gabon. In Actes du XIVe Congrès de l’UISPP, Liège 2–8 September 2001, Préhistoire en Afrique (pp. 189–198). BAR International Series 2006.

- World Bank. République Démocratique du Congo: Cadre stratégique pour la préparation d’un programme de développement des Pygmées (Rapport n° 51108-ZR), 2009. World Bank.

- Kipalu, P.; Kiyulu, J.; Uwimana, A. Les peuples autochtones et les forêts : Vers une reconnaissance légale en RDC. RFUK/Forest Peoples Programme 2016.

- Initiative Interreligieuse pour les Forêts Tropicales. Peuples autochtones et forêts: Alliés dans la conservation mondiale. UNEP 2019.

- Kama, F. Géographie 3e secondaire. Hatier 1971.

- Mumbanza mwa Bawele, J.; Stroobant, E.; Tshonda, J.O.; Krawczyk, J.; Lomboto, G.L.; Empengele, J.L.; ... & Verhegghen, A. Projet « Provinces ». Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale. http://www.africamuseum.be/research/publications/rmca/online/2016.

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling techniques (3rd ed.), 1977, John Wiley & Sons.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Island Press 2005.

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Angelesen, A.; Belcher, B.; Burgers, P.; Nasi, R.; Santoso, L.; Wunder, S. Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in developing countries: An overview. World Development 2005, 33, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Sacred ecology 2012. Routledge.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Corbera, E.; Reyes-García, V. Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecology and Society 2013, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colding, J.; Folke, C. Social taboos: “Invisible” systems of local resource management and biological conservation. Ecological Applications 2001, 11, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhem, K. The human environment: Knowledge and learning in the African landscape. In The Ecology of Practice. Routledge, 2016, pp. 39–56.

- Ellen, R.; Harris, H. Introduction. In Ellen, R.; Parkes, P. & Bicker, A. (Eds.), Indigenous environmental knowledge, and its transformations. Harwood Academic Publishers, 2000, pp. 1–33.

- Howard, P. Women and plants: Gender relations in biodiversity management and conservation. Zed Books, 2003.

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Langton, M. The ‘wild’, the market and the native: Indigenous people face new forms of global colonization. In The future of Indigenous peoples: Strategies for survival and development. UCLA American Indian Studies Center, 2002, pp. 1–30.

- Verschuuren, B.; Wild, R.; McNeely, J.A.; Oviedo, G. (Eds.) 2010. Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. Earthscan.

- Berkes, F.. Sacred ecology (4th ed.). Routledge, 2018.

- Reyes-García, V.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; McElwee, P.; Molnár, Z.; Östergren, P.O.; Wilson, S.J.; Brondizio, E.S. Indigenous peoples and local communities, nature, and society: New perspectives on the human–nature nexus. Ecology and Society 24, 14.

- Golden, J.; Comaroff, J. The role of taboos in conserving wildlife. Nature Sustainability, 2015, 1, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Crona, B.; Nyström, M.; Folke, C.; Jiddawi, N. Middlemen, a critical social–ecological link in coastal communities of Kenya and Zanzibar. Marine Policy, 2010, 34, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier-Salem, M.-C.; Roussel, B. From livelihoods to collective action: Tidal ecosystems and the politics of mangrove conservation in West Africa. African Journal of Marine Science, 2012, 34, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, J.; Gavin, M.C. Perceptions of the value of traditional ecological knowledge to formal school curricula: Opportunities and challenges from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2015, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheil, D.; Lawrence, A. Tropical biocultural diversity: A wider perspective. Ambio, 2004, 33, 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society, 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffi, L.; Woodley, E.. Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook. Routledge, 2010.

- Zanotti, L.; Chernela, J. Cultural keystone places: Conservation and social–ecological resilience. Human Ecology, 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; ... & Shirayama, Y. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science, 2018, 359, 270–272. [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; ... & Shirayama, Y. Biodiversity and equity: Aligning conservation with social justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2021, 46, 465–493.

- Gavin, M.C.; McCarter, J.; Mead, A.T.P.; Berkes, F.; Stepp, J.R.; Peterson, D.; Tang, R. Defining biocultural approaches to conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2015, 30, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Bates, P.; Carino, J.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Ferrari, M.F.; ... & Shrestha, U.B. Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: Indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2021, 46, 481–509. [CrossRef]

- Rights and Resources Initiative, 2015. Who owns the world’s land? A global baseline of formally recognized Indigenous and community land rights. RRI.

| Vegetation type | Equateur | Equateur/DRC | DRC | |

| surface area (ha) | surface area (%) | surface area (%) | surface area (ha) | |

| Dense rain forest | 4 537 687 | 44.88 | 4.85 | 93 517 825 |

| Forest on hydromorphic soil | 4 768 070 | 47.15 | 31.40 | 15 183 214 |

| Swampy vegetation | 85 551 | 0.85 | 15.97 | 535 714 |

| Shrub savannah | 2 477 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 15 335 810 |

| grassy savanna | 57 084 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 14 881 257 |

| Total natural vegetation | 9 450 870 | 93.46 | 5.44 | 173 855 384 |

| Permanent agriculture | 1 421 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1 555 849 |

| Agricultural complex | 659 449 | 6.52 | 1.23 | 53 576 845 |

| Total anthropized area | 660 870 | 6.54 | 0.38 | 55 132 694 |

| Territory | Hydrography | Soil |

| Ingende | Ingende Territory is characterized by a hydrological network dominated by the Ruki River, which receives its main tributaries, the Momboyo and the Busira, before discharging into the Congo river; the Ingende town, the territorial administrative center, is situated at their confluence. | The soil in the region is moist and sandy-clayey. This soil’s type is conducive to the fruiting of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis). This explains the presence of a large oil palm plantation in Boteka. |

| Bikoro | The Bikoro region’s hydrography is dominated by Lake Ntomba (surface area: 765 km2) in its western sector. Downstream of the lake, toward the Lukolela Territory (Irebu), significant watercourses are present, which frequently transform the area into vast wetlands (Lolo, Lolambo, Bituka, Boloko), along with (the smaller) Lake Mpaku, connected to the Ruki River. | The soil in the Bikoro region is characterized by a sandy-clay composition. This edaphic type is particularly suitable for slash-and-burn agricultural practices in the Ekonda and Elanga sectors. In the Lac sector, the soil frequently exhibits hydromorphic properties with wetland characteristics. |

| Territories | Sectors | Villages | Number of households | Total number |

| Ingende | Dwali | Ingende centre | 27 | 150 |

| Boteka | 20 | |||

| Makako | 20 | |||

| Bofalamboka | 20 | |||

| Ntomba | 20 | |||

| Bofekalasumba | 20 | |||

| Ilambasa | 20 | |||

| Ingende | 3 | |||

| Bokatola | Bongongo | 10 | 20 | |

| Ilanga | 10 | |||

| Total Ingende | 170 | |||

| Bikoro | Lac Ntomba | Bikoro centre | 20 | 80 |

| Ntondo | 20 | |||

| Moheli | 10 | |||

| Iyembe moke | 10 | |||

| Lokando | 10 | |||

| Mpabolia | 9 | |||

| Mpa bolia | 1 | |||

| Ekonda | Ikoko impenge | 12 | 30 | |

| Mekakalaka | 8 | |||

| Itipo | 8 | |||

| Ngeli alingo/maringo | 1 | |||

| Ngeli alingo | 1 | |||

| Elanga | Elanga | 10 | 40 | |

| Baolongo | 10 | |||

| Beambo | 8 | |||

| Lokolama | 7 | |||

| Penzele | 3 | |||

| Nkalamba | 2 | |||

| Total | 150 | |||

| General total | 320 | |||

| Variable | Classification | Number | Proportion (%) |

| Sex | Women | 38 | 11.88 |

| Men | 282 | 88.12 | |

| Status in the village | Indigenous | 272 | 85 |

| Non-Indigenous (Bantu) | 48 | 15 | |

| Level of study | Illiterate | 132 | 41.25 |

| Primary | 48 | 15 | |

| High school | 120 | 37.5 | |

| University | 20 | 6.25 | |

| Age | 18-25 years | 18 | 5.63 |

| 26-40 years | 148 | 46.25 | |

| >40 years | 154 | 48.12 | |

| Marital status | Married | 277 | 86.56 |

| Single | 19 | 5.94 | |

| Divorced | 13 | 4.06 | |

| Widow | 11 | 3.44 | |

| Main activity | Agriculture | 175 | 54.69 |

| Teacher | 56 | 17.50 | |

| Trade | 19 | 5.94 | |

| Health personnel | 21 | 6.56 | |

| Fishing | 15 | 4.69 | |

| Administration | 14 | 4.38 | |

| Civil service | 4 | 1.25 | |

| Pastor | 1 | 0.31 | |

| Hunting | 2 | 0.63 | |

| Livestock | 1 | 0.31 | |

| Study | 5 | 1.56 | |

| Work in the oil mill of Boteka | 3 | 0.94 | |

| Lawyer | 1 | 0.31 | |

| Logging | 3 | 0.94 |

| VS | MS | LS | PA | PEW | PEP | ES | SP | PUR | AUR | Const | |

| SEX | 4.1265 * | 10.22 * | 3.0654 Ns | 128.85 ** | 1.89 10-30 Ns | 7.5381 * | 0.90717 Ns | 7.7557 * | 52.774 ** | 3.3942 Ns | 0.37881 Ns |

| VS | - | 9.6102 * | 41.988 ** | 145.43 ** | 0.15785 Ns | 7.3409 * | 0.18961 Ns | 85.751 ** | 62.764 ** | 11.902 ** | 9.0591 * |

| MS | - | - | 14.074 Ns | 175.35 ** | 0.31242 Ns | 2.6145 Ns | 3.4747 Ns | 10.314 Ns | 13.053 Ns | 7.4972 Ns | 3.1537 Ns |

| LS | - | - | 385.14 ** | 3.3543 Ns | 11.669 Ns | 3.5414 Ns | 22.218 ** | 21.023 ** | 14.201 ** | 4.7081 Ns | |

| PA | - | - | - | -- | 96.38 ** | 200.89 ** | 47.019 Ns | 200.15 ** | 157.05 ** | 403.39 * | 126.54 ** |

| PEW | - | - | - | - | - | 11.934 ** | 0.04501 Ns | 9.3153 ** | 1.7431 Ns | 0.031946 Ns | 10.016 ** |

| PEP | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28.765 ** | 4.7013 Ns | 11.187, * | 7.4564 Ns | 4.694 Ns |

| ES | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.67882 Ns | 4.8929 Ns | 0.1136 Ns | 55.012 ** |

| SP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 66.834 ** | 15.207 ** | 0.61246 Ns |

| PUR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22.945 ** | 7.7582 Ns |

| AUR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 64.00Ns |

| Dimension | Cronbach’s alpha |

Represented variance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (eigenvalue) | Inertia | % of the variance | ||

| 1 | 0.740 | 3.108 | 0.259 | 25.897 |

| 2 | 0.614 | 2.285 | 0.190 | 19.044 |

| Total | 5.393 | 0.449 | ||

| Mean | 0.686a | 2.696 | 0.225 | 22.470 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).