Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

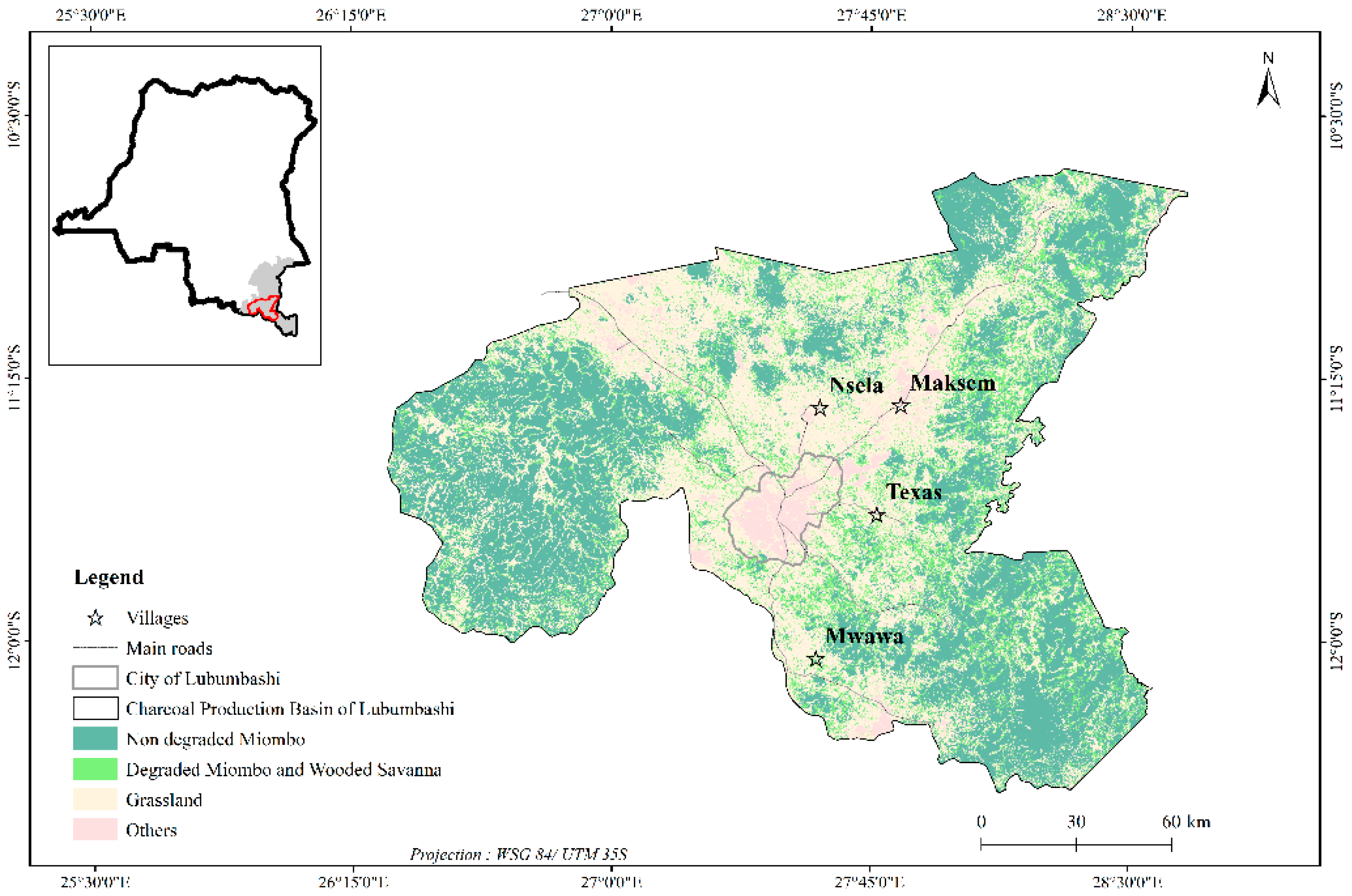

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Site Selection, Sampling, and Data Collection

2.2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Traditional Knowledge, Transmission and the Role of Ceremonials in Biodiversity Conservation and Miombo Woodlands Management

3.1.1. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Practices Related to Biodiversity Conservation and Miombo Woodlands Management

3.1.2. Circumstances of Knowledge Transmission and the Role of Ceremonial in Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management

3.2. Association Between TEK-Elements Variables of the Socio-Demographic Profile and Similarity of Biodiversity Conservation and Miombo Woodlands Management Practices

4. Discussion

4.1. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Practices, Transmission and Role of Ceremonials in Biodiversity Conservation and Miombo Woodlands Management

4.2. Association Between TEK and Similarity of Implementation of Biodiversity Conservation Practices and Miombo Woodlands Management

4.3. Involvement in Contributing to the Sustainable Management and Restoration of Miombo Woodlands

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gboze, A. E.; Sanogo, A.; Amani, B. H. K. & Kassi, E. N. J. Diversité floristique et valeur de conservation de la forêt classée de Badenou (Corhogo, Cote d’Ivoire). Agr. Afr. 2020, 32, 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Eba’a Atyi, R. ; Hiol Hiol, F. ; Lescuyer, G. ; Mayaux, P. ; Defourny, P. ; Bayol, N. ; Saracco, F. ; Pokem, D. ; Sufo Kankeu, R. & Nasi R. Les forêts du bassin du Congo : état des forêts 2021. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonésie, 2022, 180p. [CrossRef]

- Sivadas, D. Pathways for Sustainable Economic Benefits and Green Economies in Light of the State of World Forests 2022. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 1, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. La Situation des forêts du monde 2022 : Des solutions forestières pour une relance verte et des économies inclusives, résilientes et durables. FAO, Rome, Italie, 2022, 180p. [CrossRef]

- West, P. C.; Narisma, G. T.; Barford, C. C.; Kucharik, C. J. & Foley, J. A. An alternative approach for quantifying climate regulation by ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Envir. 2011, 9, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet, P.; Vermeulen, C.; Feintrenie, L.; Dessard, H. & Garcia, C. Quelles sont les causes de la déforestation dans le bassin du Congo ? Synthèse bibliographique et études de cas. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2016, 20, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M. H.; N’tambwe, N. D.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Kouagou, R. S.; Cabala, K. S.; Munyemba, F. M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J. & Useni, S.Y. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, E.; Okali, D.; Kowero, G. & Larwanou, M. Forêts, faune sauvage et changement climatique en Afrique. African Forest Forum, Nairobi, Kenya, 2011, 344p.

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 – Key findings. Rome, Italie, 2020, 16p. [CrossRef]

- De Wasseige, C.; De Marcken, P.; Bayol, N.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Mayaux, Ph.; Desclée, B.; Nasi, R.; Billand, A.; Defourny, P. & Eba’a Atyi, R. Les forêts du bassin du Congo - Etat des Forêts 2010. Office des publications de l’Union Européenne. Luxembourg, 2012, 276 p. [CrossRef]

- Vancutsem, C.; Achard, F.; Pekel, J-F. ; Vieilledent, G.; Carboni, S.; Simonetti, D.; Gallego, J.; Aragao, L. & Nasi, R. Long-term (1990-2019) monitoring of tropical moist forests dynamics. Sci. Adv. 2020, 7, eabe1603. [Google Scholar]

- Megevand, C. Dynamiques de déforestation dans le bassin du Congo : Réconcilier la croissance économique et la protection de la forêt. Washington D. C.: World Bank, 2013, 201p.

- Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Boisson, S. & Sikuzani, Y. U. La végétation naturelle d’Élisabethville (actuellement Lubumbashi) au début et au milieu du XXième siècle. Géo-Eco-Trop. 2021, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Potapov, P. V.; Turubanova, S. A.; Hansen, M. C.; Adusei, B.; Broich, M.; Altstatt, A.; Mane, L. & Justice, C.O. Quantifying forest cover loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2010, with Landsat ETM+ data. Remote Sens. Envir. 2012, 122, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M. H.; N’tambwe, N. D.; Mwamba, K. F.; Harold, S.; Munyemba, K. F.; Malaisse, F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Useni, S. Y. & Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabala, K. S.; Useni, S. Y.; Amisi, M. Y. A.; Munyemba, K. F. & Bogaert J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers dans les zones territoriales de l’Arc Cuprifère Katangais (RD Congo). Tropicultura 2022, 40(3/4), 2100. [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe, N. D.; Khoji, M. H.; Kasongo, K. B.; Kouagou, S. R.; Malaisse, F.; Useni, S. Y.; Masengo, K. W. & Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023a, 14, 687. [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F. K.; Quinn, C. H.; Dougill, A. J. & Vinya, R. Floristic composition, species diversity and carbon storage in charcoal and agriculture fallows and management implications in Miombo woodlands of Zambia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 304, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P. W.; Larwanou, M.; Syampungani, S. & Babalola, F.D. Management and restoration practices in degraded landscapes of Eastern Africa and requirements for up-scaling. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlee, J. L.; Gonçalves, F. M.; Tchamba, J. J.; Chisingui, A. V.; Muledi, J. I.; Shutcha, M. N.; Ryan, C. M.; Brade, T. K. & Dexter, K. G. Diversity and Structure of an Arid Woodland in Southwest Angola, with Comparison to the Wider Miombo Ecoregion. Diversity 2020, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, T.; Muller, A. & Morris, M. Manuel La Régénération Naturelle Assistée (RNA). Une ressource pour les gestionnaires de projets, les utilisateurs et tous ceux qui ont un intérêt à mieux comprendre et soutenir le mouvement pour la RNA. FMNR Hub, World Vision Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2020, 241p.

- Awono, A.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; Tsanga, R.; Guizol, P. & Peroches, A. Restauration des paysages forestiers et régimes fonciers au Cameroun : Acquis et handicaps. Document Occasionnel 10. Bogor, Indonésie : Centre de recherche forestière internationale (CIFOR) ; et Nairobi, Kenya : Centre international de recherche en agroforesterie (ICRAF), 2023, 43 p. [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D. & Aide, T.M. When and where to actively restore ecosystems? For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R. & Honnay, O. Forest restoration, biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. BioMed. Central Ecol. 2011, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, M. L. “Yo soy indígena”: identifying and using traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) to make the teaching of science culturally responsive for Maya girls. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2013, 8, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, W. M. & Larigauderie, A. A Rosetta Stone for nature’s benefits to people. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. & Gavin, M. C. A classification of threats to traditional ecological knowledge and conservation responses. Conserv. Soc. 2016, 14, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, S. Roles of Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2017, 7(15), 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R. Human Dimensions: Traditional Ecological Knowledge—Finding a Home in the Ecological Society of America. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2021, 102(3), e01892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganka, G.; Fandohan, A. B. & Salako, K. V. Impacts des tabous et des cérémonies rituelles sur la structure des peuplements de Triplochiton scleroxylon K. Schum., un arbre sacré au Bénin. Bois For. des Trop. 2023, 357, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, Y.; Asselin, H.; Bergeron, Y.; Doyon, F. & Boucher, J-F. Contribution of traditional knowledge to ecological restoration: Practices and applications, Écoscience 2012, 19, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takako, H. Savoirs écologiques traditionnels : de la boîte noire sacrée à la politique de conservation de la biodiversité locale. Policy Sci. 2002, 10, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hens, L. Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity conservation and management in Ghana. J. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 20 (1), 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Ntoko, V. N. & Schmidt, M. Indigenous knowledge systems and biodiversity conservation on Mount Cameroon. For. Trees Livelihoods 2021, 30 (4): 227–241. [CrossRef]

- Taremwa, N. K.; Gasingirwa, M. C. & Nsabimana, D. Unleashing traditional ecological knowledge for biodiversity conservation and resilience to climate change in Rwanda. African J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2022, 14, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Traditional ecological knowledge and its role in biodiversity conservation: a systematic review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1164900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milupi, D. I. & Sampa, M. M. Transmission mechanisms of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and sustainable management of natural resources among the Lozi-speaking people in Barotse floodplain of Zambia. Multidscip. J. Lang. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2020, 3, 216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Malekani, A. W. Indigenous Knowledge acquisition and sharing on wild mushroom among local communities in selected districts in Tanzania. J. Indig. Knowl. Dev. Stud. 2022, 4(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yanou, M. P.; Ros-Tonen, M.; Reed, J. & Sunderland, T. Local knowledge and practices among Tonga people in Zambia and Zimbabwe: A review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 142, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syampungani, S.; Chirwa, P. W.; Akinnifesi, F. K.; Ajayi, O. C. & Sileshi, G. The miombo woodlands at the cross roads: Potential threats, sustainable livelihoods, policy gaps and challenges. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisse, F. How to live and survive in Zambezian open forest (Miombo ecoregion). Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2010, 424 p.

- Hick, A.; Hallin, M. Tshibungu, N. A. & Mahy, G. La place de l’arbre dans les systèmes agricoles de la région de Lubumbashi. In : Bogaert, J. ; Colinet, G. & Mahy, G. (Eds), Anthropisation des paysages katangais. Les Presses Universitaires de Liège, Liège, Belgique, 2018, 111–123.

- Kalombo, K. D. Caractérisation de la répartition temporelle des précipitations à Lubumbashi (Sud-Est de la RDC) sur la période 1970-2014. XXIII Colloque de l’Association Internationale de Climatologie, Liege, 2015, 531–536.

- Mutondo, G. T.; Kamutanda, D. K. & Numbi, A. M. Evaluation du bilan hydrique dans les milieux anthropisés de la forêt claire (région de Lubumbashi, Province du Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo). Méthodologie adoptée pour l’estimation de l’évapotranspiration potentielle. Geo-Eco-Trop. 2018, 42, 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kalombo, K. D. Évolution des éléments du climat en RDC : Stratégies d'adaptation des communautés de base, face aux événements climatiques de plus en plus fréquents. Éditions universitaires européennes, Sarrebruck, Germany, 2016, 220p.

- Ngongo, M. L.; Van Ranst, E.; Baert, G.; Kasongo, E. L.; Verdoodt, A.; Mujinya, B. B. & Mukalay, J. M. Guide des sols en République Démocratique du Congo, tome I : étude et gestion. Ed. Salama, Lubumbashi, République Démocratique du Congo, 2009, 260p.

- Munyemba, K. F. & Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique spatiotemporelle de l’occupation du sol dans la région de Lubumbashi entre 1956 et 2009. E-revue Unilu 2014, 1, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, S. Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K. S.; Munyemba, K. F. & Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo) : Synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, S. Y.; Mpibwe, K. A.; Yona, M. J.; N’tambwe, N. D.; Malaisse, F. & Bogaert, J. Assessment of Street Tree Diversity, Structure and Protection in Planned and Unplanned Neighborhoods of Lubumbashi City (DR Congo). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S. Y.; Khoji, M. H. & Bogaert, J. Miombo woodland, an ecosystem at risk of disappearance in the Lufira Biosphere Reserve (Upper Katanga, DR Congo)? A 39-years analysis based on Landsat images. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biloso, M. A. Valorisation des produits forestiers non ligneux des plateaux de Batéké en périphérie de Kinshasa (R. D. Congo). Acta Bot. Gall. 2009, 156, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khaddar, H. & Elbouyahyaoui, L. La démarche scientifique en mathématiques, en sciences expérimentales et en sciences sociales. Rech. Cognit. 2019, 11, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L. G. & Sabin, K. Échantillonnage déterminé selon les répondants pour les populations difficiles à joindre. Methodol. Innov. 2010, 5(2), 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marpsat, M. & Razafindratsima, N. Les méthodes d’enquêtes auprès des populations difficiles à joindre : Introduction au numéro spécial. Methodol. Innov. 2010, 5, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traoré, L.; Hien, M. & Ouédraogo, I. Usages, disponibilité et stratégies endogènes de préservation de Canarium schweinfurthii (Engl.) (Burseraceae) dans la région des Cascades (Burkina Faso) Uses, availability and endogenous conservation strategies of Canarium schweinfurthii (Engl.) (Burseraceae) in the Cascades region (Burkina Faso). Ethnobot. Res. App. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E. & Michaux, E. Étalonnages à l’aide d’enquêtes de conjoncture : de nouveaux résultats. Écon. Prévis. 2006, 172, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieng, K.; Kalandi, M.; Sow, A.; Millogo, V.; Ouedraogo, G. A. & Sawadogo, G. J. Profil socio-économique des acteurs de la chaine de valeur lait local à Kaolack au Sénégal. Rev. Afr. Sant. Product. Anim. 2014, 12(3-4), 161–168.

- Smith, P. & Allen Q. Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of the Miombo Woodlands; Royal Botanic Gardens: Brussels, Belgium, 2010, 176p.

- Meerts, P. J. & Hasson, M. Arbres et arbustes du Haut-Katanga. 386 p. Editions Jardin Botanique de Meise : Brussels, Belgium, 2016, 386p.

- Vollesen, K. Woodland. In Based on Plants from the Mutinondo Wilderness Area, Northern Zambia; Lari Merret: Lusaka, Zambia, 2020; 1200p. [Google Scholar]

- Badjaré, B.; Kokou, K.; Bigou-laré, N.; Koumantiga, D. & Akpakouma, A. Étude ethnobotanique d’espèces ligneuses des savanes sèches au Nord-Togo : diversité, usages, importance et vulnérabilité. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2018, 22, 152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Confais, J. ; Grelet, Y. & Monique, L.G. La procédure FREQ de SAS. Tests d’indépendance et mesures d’association dans un tableau de contingence. MODULAD 2005, 33,188–242. ⟨halshs-00287397⟩.

- Causton, D. R. An introduction to vegetation analysis. Principes, practice and interpretation. Springer Science & Business Media, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2012, 363p. [CrossRef]

- Kindo, A. I.; Abasse, T.; Soumana, I.; Bogaert, J. & Mahamane, A. Perception locale et facteurs de mutation de la flore ligneuse d’une aire protégée d’Afrique de l’Ouest : cas de la Réserve Partielle de Faune de Dosso, Niger. Afr. Sci. 2019, 15( 6), 229–249.

- Moupela, C.; Vermeulen, C.; Daïnou, K. & Doucet, J.-L. Le noisetier d’Afrique (Coula edulis Baill.). Un produit forestier non ligneux méconnu. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2011, 15, 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, N. S.; Katerere, Y.; Chirwa, P. W. & Grundy, I.M. Miombo Woodlands in a Changing Environment: Securing the Resilience and Sustainability of People and Woodlands. Springer International Publishing, Cham., Switzerland, 2020, 269p. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J. & Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, S. T.; Burgess, N. D.; Fa, J. E.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C. J.; Watson, J. E. M.; Zander, K. K.; Austin, B.; Brondizio, E. S.; French Collier, N.; Duncan, T.; Ellis, E.; Geyle, H.; Jackson, M. V.; Jonas, H.; Malmer, P.; McGowan, B.; Sivongxay, A. & Leiper, I. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 369–374.

- Juhé-Beaulaton, D. Bois sacrés et conservation de la biodiversité (sud Togo et Bénin). In : Deslaurier C., Juhé-Beaulaton, D. (Eds). Afrique, terre d’histoire. Karthala, Paris, France, 2007, 115–129.

- Sinthumule, N.I. & Mashau, M.L. Traditional ecological knowledge and practices for forest conservation in Thathe Vondo in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, E. A.; Ababio, S. & Boadu, K. B. The use of indigenous cultural practices by the Ashantis for the conservation of forests in Ghana. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 215824401668761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhura, E. & Mushure, S. Forest and wildlife resource-conservation efforts based on indigenous knowledge: The case of Nharira community in Chikomba district, Zimbabwe. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 105: 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Mota, L.; Rogério, M.; Lauer-Leite, I. D. & De Novais, J. S. Intergenerational transmission of traditional ecological knowledge about medicinal plants in a riverine community of the Brazilian Amazon. Polibot. 2023, 56, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, F. Analyzing knowledge as part of a cultural framework: the case of traditional ecological knowledge. Environ. 2008, 36(2), 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; Huanca, T.; Vadez, V.; Leonard, W. & Wilkie, D. Cultural, Practical, and Economic Value of Wild Plants: a Quantitative Study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Biloso, M. A.; Vranken, I. & André, M. Peri-urban dynamics: landscape ecology perspectives. In : Bogaert, J.& Halleux, J. M. (Eds), Territoires périurbains : Développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du Sud. Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2015, 63-73.

- Patricia, L. Women and Plants: Gender Relations in Biodiversity Management and Conservation. J. Ethnobiol. 2005, 25, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zent, S. Acculturation and ethnobotanical knowledge loss among the Piaroa of Venezuela: Demonstration of a quantitative method for the empirical study of TEK change. In: Maffi, L. (Eds.), On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C, USA, 2001, 190–211.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E. & Reyes-García, V. Reinterpreting Change in Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyniers, C. Agroforesterie et déforestation en République démocratique du Congo. Miracle ou mirage environnemental ? Mond. en Dév. 2019, 187, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schure, J.; Ingram, V.; Assembe, S.M.; Mvula, E.M. & Levang, P. La filière bois-énergie des villes de Kinshasa et Kisangani (RDC). In : Marien, J.- N. ; Dubiez, E. ; Louppe, D. & Larzillière, A. (Eds.), Quand la ville mange la forêt : Les défis du bois-énergie en Afrique centrale. Edition Quae, Paris, France, 2013, 27–44.

- N’tambwe, N. D., Biloso, M. A. Malaisse, F., Useni, S. Y., Masengo, K.W., Bogaert, J. Socio-Economic Value and Availability of Plant-Based Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) within the Charcoal Production Basin of the City of Lubumbashi (DR Congo). Sustainability 2023b, 15, 14943. [CrossRef]

- Kyale, K. J. & Maindo, M. N. A. Pratiques Traditionnelles de Conservation de la Nature à L’épreuve des Faits Chez Les Peuples Riverains de la Réserve de Biosphère de Yangambi (RDC). Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 328–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley, S.; Fischer, A. P. & Jones, E. T. Integrating Traditional and Local Ecological Knowledge into Forest Biodiversity Conservation in the Pacific Northwest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 246, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diawuo, F. & Issifu, A. K. Exploring the African traditional belief systems (totems and taboos) in natural resources conservation and management in Ghana. In: Chimakonam, J. (Eds.), African Philosophy and Environmental Conservation. 1st Ed., Routledge, New York, USA, 2017, 209–221.

- Phuthego, T. C. & Chanda, R. Traditional ecological knowledge and community-based natural resource management: Lessons from a Botswana wildlife management area. Appl. Geogr. 2004, 24, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- imoh S. O.; Ikyaagba E. T.; Alarape A. A.; Obioha E. E. & Adeyemi A. A. The role of traditional laws and taboos in wildlife conservation in the oban hill sector of cross river national park (CRNP), Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 39 (3), 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Kosoe, E. A.; Adjei, P. O. W. & Diawuo, F. From sacrilege to sustainability: The role of indigenous knowledge systems in biodiversity conservation in the upper west region of Ghana. GeoJournal 2020, 85 (4), 1057–1074. [CrossRef]

- Maffi, L. & Woodley, E. Biocultural diversity conservation: a global sourcebook. Earthscan, London & Washington D.C., UK & USA, 2012, 304p.

- Sutherland, W. J.; Gardner, T. A.; Haider, L. J. & Dicks, L. V. How can local and traditional knowledge be effectively incorporated into international assessments? Oryx 2014, 48, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Austin, B. J.; Danielsen, F. & Fernández-Llamazares, Á. Creating Synergies between Citizen Science and Indigenous and Local Knowledge. BioScience 2021, 71, 503–518. [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe, N. D.; Khoji, M. H.; Salomon, W.; Cuma, M. F.; Malaisse, F.; Ponette, Q.; Useni, S. Y.; Masengo, K. W. & Bogaert, J. Floristic Diversity and Natural Regeneration of Miombo Woodlands in the Rural Area of Lubumbashi, D.R. Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Sacred natural sites: conserving nature and culture, edited by Bas Verschuuren, Robert Wild, Jeffrey McNeely and Gonzalo Oviedo. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, S. A.; Kushalappa, C. G.; Williams, P. H. & Brown, N. D. A landscape approach to biodiversity conservation of sacred groves in the Western Ghats of India. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, D. J.; Galloway McLean, K.; Thulstrup, H. D.; Ramos Castillo, A. & Rubis, J. T. Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation. UNESCO, Paris, and United Nations University, Darwin, Australia, 2012, 120p.

| Villages | Population size | Forests availability | Focus group participant | Number of people surveyed for validation | Gender (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | |||||

| Maksem | 356 | Limited | 8 | 50 | 8 | 92 |

| Texas | 333 | 12 | 50 | 48 | 52 | |

| Mwawa | 163 | Available | 11 | 50 | 24 | 76 |

| Nsela | 126 | 12 | 50 | 36 | 64 | |

| Types | Beliefs | Taboos | VRFMD & HE | VRFD & HF | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maksem n=50 | Texas n=50 |

Mwawa n=50 | Nsela n=50 | |||||

| Cemeteries | Ancestors' rest | Tree cutting, | 92.00 (90.00) | 78.00 (78.00) | 74.00 (74.00) | 62.00 (62.00) | 0.007* (0.013*) |

|

| Bush fires, | ||||||||

| Collects NTFPs, | ||||||||

| Access (authorization) | ||||||||

| Pregnant women, | ||||||||

| Children | ||||||||

| Mountain | Dwelling of spirits & divinities; place of prayer & exorcism |

Access (except for insiders), Bush fires | - | - | 8.00 (8.00) | - | 0.121 (0.121) | |

| Dense dry forests | Bush fires | - | - | 6.00 (4.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.121 (0.246) | ||

| River sources | Bush fires, Tree cutting, Access |

8.00 (2.00) | 22.00 (6.00) | 10.00 (6.00) | 28.00 (4.00) | 0.573 (1.000) | ||

| Termite mounds | - | - | 8.00 (6.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.059 (0.121) | |||

| Scientific names | Families | Availability in the forest | Beliefs about species | VRFMD & HE | VRFD & HF | p | ||||

| Maksem n=50 |

Texas n=50 |

Mwawa n=50 |

Nsela n=50 |

|||||||

| Afzelia quanzensis Welw. | Fabaceae | Rare | Ancestral habitat, medicinal species | 4.00 (4.00) |

- | 36.00 (36.00) |

22.00 (22.00) |

0.000* (0.000*) |

||

|

Anisophyllea boehmii Engl. |

Anisophylleaceae | Available | Food, medicinal species, customary chief's establishment | 10.00 | 32.00 | 10.00 | 12.00 | 0.081 | ||

| Annona senegalensis Pers. | Annonaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 2.00 | - | 2.00 | - | 1.000 | ||

| Bobgunnia madagascariensis (Desv.) J.H. Kirkbr. & Wiersama | Fabaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | - | - | 4.00 | 10.00 (6.00) |

0.498 (0.331) |

||

| Brachystegia boehmii Taub. | Fabaceae | Available | Helps make incantations underfoot to heal or get rid of evil spirits | - | - | 10.00 | - | 0.059 | ||

| Brachystegia spp. and Julbernardia spp. | Fabaceae | Available | Shelters ancestral spirits | 8.00 | 6.00 | 22.00 | 20.00 | 0.007* | ||

| Cassia abbreviata Oliv. | Fabaceae | Rare | Sacred, medicinal species | - | 6.00 (6.00) |

12.00 (12.00) |

6.00 (6.00) |

0.134 (0.003*) |

||

| Combretum molle Engl. & Diels | Combretaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 4.00 | - | 12.00 | 8.00 | 0.035* | ||

| Diplorhynchus condylocarpon (Müll. Arg.) Pichon | Apocynaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | - | 2.00 | - | - | 1.000 | ||

| Entandrophragma delevoyi De Wild. | Meliaceae | Rare | Sacred species, medicinal, prediction of future events | 44.00 (44.00) |

20.00 (20.00) |

40.00 (40.00) |

40.00 (40.00) |

0.302 (0.302) |

||

| Erythrina abyssinica Lam. ex DC. | Fabaceae | Available | Medicinal species, herald the good rainy season | 4.00 | - | 12.00 (2.00) |

12.00 | 0.010* (1.000) |

||

| Ficus spp | Moraceae | Available | Shelters ancestral spirits, medicinal | 14.00 (6.00) |

26.00 (12.00) |

32.00 (18.00) |

12.00 (10.00) |

0.862 (0.376) |

||

| Isoberlinia spp | Fabaceae | Rare | Prayers of traditional chiefs, medicinal plants | 8.00 | - | 6.00 | 10.00 | 0.373 | ||

| Lannea discolor (Sond.) Angl. | Anacardiaceae | Available | Ancestral prayers, Enthronement of the chief | - | - | 6.00 | - | 0.246 | ||

| Marquesia macroura Gilg | Dipterocarpaceae | Available | Representation of ancestors, medicinal | - | - | 12.00 (10.00) |

8.00 (2.00) |

0.002* (0.029*) |

||

| Parinari curatellifolia Planch. ex Benth. | Chrysobalanaceae | Available | Food, medicinal, establishment of a traditional chief | 14.00 | 26.00 | 32.00 | 12.00 | 0.862 | ||

| Pericopsis angolensis (Boulanger) Meeuwen | Fabaceae | Available | Representation of ancestors, medicinal, dispels curse | - | 8.00 | 6.00 | 10.00 | 0.373 | ||

| Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh. | Fabaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 2.00 | - | 16.00 | - | 0.035* | ||

| Psorospermum febrifugum Spach | Hypericaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 2.00 | - | - | - | 1.000 | ||

| Pterocarpus angolensis DC. | Fabaceae | Available | Sacred medicinal species | - | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.246 | |||

| Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. | Fabaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 6.00 | - | 14.00 | 8.00 | 0.049* | ||

| Rothmannia engleriana (K. Schum.) Keay | Rubiaceae | Available | Medicinal species, create disputes between partners | 2.00 | - | - | 2.00 | 1.000 | ||

| Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen. | Polygalaceae | Available | Medicinal species, home to the spirits | - | - | - | 2.00 (2.00) |

1.000 (1.000) |

||

| Sterculia quinqueloba (Garcke) K. Schum. | Malvaceae | Rare | Sacred species, medicinal, discover hidden events, luck tree, frighten away sorcerers, destroy the power of gris-gris, save poultry from epidemics | 40.00 (40.00) |

12.00 (12.00) |

30.00 (30.00) |

58.00 (58.00) |

0.012* (0.012*) |

||

| Strychnos cocculoides Delile | Loganiaceae | Available | Food and medicinal species | 18.00 | 12.00 | 30.00 | 14.00 | 0.275 | ||

| Syzygium guineense DC. Subsp macrocarpum | Myrtaceae | Available | Food and medicinal species | - | 4.00 | - | - | 0.498 | ||

| Terminalia mollis M.A.Lawson | Combretaceae | Available | Sacred, medicinal species | 2.00 (2.00) |

- | - | 6.00 (4.00) |

0.621 (1.000) |

||

| Uapaca kirkiana Müll.Arg. | Phyllanthaceae | Available | Food species, ceremony before ploughing, medicinal | 22.00 | 14.00 | 26.00 | 8.00 | 1.000 | ||

| Zanha africana (Radlk.) Exell | Fabaceae | Rare | Sacred, medicinal species | - | - | 2.00 (2.00) |

- | 1.000 (1.000) |

||

| Zanthoxylum chalybeum Engl. | Rutaceae | Rare | Sacred, medicinal species | 2.00 (2.00) |

- | 14.00 (14.00) |

10.00 (10.00) |

0.003* (0.003*) |

||

| Traditional practices | VRFMD & HE | VRFD & HF | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maksem n=50 |

Texas n=50 |

Mwawa n=50 |

Nsela n=50 |

|||

| Leaving large trees and sacred trees standing | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 8.00 | 0.498 | |

| Rare and sacred medicinal trees left standing | (8.00) | (10.00) | (4.00) | (16.00) | (0.435) | |

| Small-scale farming | 16.00 | 32.00 | 14.00 | 16.00 | 0.153 | |

| Agriculture without stump grubbing | 4.00 (4.00) |

- | 6.00 (6.00) |

8.00 (8.00) |

0.170 (0.170) |

|

| Charcoal for domestic use | 6.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.683 | |

| Intercropping | 12.00 (34.00) |

4.00 (40.00) |

6.00 (20.00) |

10.00 (10.00) |

1.000 (0.000*) |

|

| Selective cutting | 6.00 | 8.00 | 2.00 (2.00) |

2.00 (2.00) |

0.170 (0.498) |

|

| Progressive operation | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 (16.00) |

4.00 (22.00) |

1.000 (0.498) |

|

| Tree-cutting banned in sacred places | 20.00 (36.00) |

26.00 (20.00) |

14.00 (8.00) |

14.00 (14.00) |

0.145 (0.004*) |

|

| Defending concessions | - | - | (12.00) | - | (0.029*) | |

| Short fallow/rotation period (3-5 years) | (10.00) | (20.00) | (6.00) | (4.00) | (0.032*) | |

| Long fallow/rotation period (15-20 years) | 12.00 (2.00) |

6.00 (6.00) |

18.00 (16.00) |

10.00 (10.00) |

0.376 (0.040*) |

|

| Optimum bushfire period | - | 4.00 | 6.00 | - | 1.000 | |

| Use of dead wood | 18.00 (6.00) |

12.00 (4.00) |

24.00 (10.00) |

26.00 (14.00) |

0.111 (0.126) |

|

| Elements | VRFMD & HE | VRFD & HF | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maksem n=50 | Texas n=50 |

Mwawa n=50 | Nsela n=50 |

|||

| Transmission modes (%) | ||||||

| Songs | 44.00 | 62.00 | 58.00 | 52.00 | 0.887 | |

| Riddles & puzzles | 8.00 | - | 6.00 | 10.00 | 0.373 | |

| Fables, tales & stories | 36.00 | 28.00 | 10.00 | 20.00 | 0.007* | |

| Scenes | - | - | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.246 | |

| Proverbs | 12.00 | 10.00 | 24.00 | 14.00 | 0.165 | |

| Circumstances of transmission (%) | ||||||

| Family advice (around the fire) | 28.00 | 40.00 | 46.00 | 50.00 | 0.254 | |

| Bereavement | 32.00 | 22.00 | 20.00 | 24.00 | 0.511 | |

| Weddings | 22.00 | 26.00 | 12.00 | 10.00 | 0.025* | |

| Newborn births | 6.00 | 8.00 | 12.00 | 8.00 | 0.613 | |

| Enthronement of a village chief | 12.00 | 6.00 | 10.00 | 8.00 | 1.000 | |

| Ceremonials | VRFMD & HE | VRFD & HF | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maksem n=50 | Texas n=50 | Mwawa n=50 | Nsela n=50 | |||

| Funeral of a loved one | 84.00 | 86.00 | 72.00 | 80.00 | 0.153 | |

| Exorcism | - | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 0.065 | |

| Induction of the new chief | 16.00 | 12.00 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 0.051 | |

| Prayers to the gods (ancestors) | - | - | 14.00 | 10.00 | 0.000* | |

| Traditional practices | Type | Age ranges |

Education level |

Main occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare and sacred medicinal trees left standing | 0.054 | 0.012* | 0.095 | 0.000* |

| Agriculture without stump grubbing | 0.297 | 0.297 | 0.053 | 0.504 |

| Intercropping | 0.006* | 0.040* | 0.004* | 0.000* |

| Selective cutting | 0.457 | 0.148 | 0.737 | 0.221 |

| Progressive operation | 0.596 | 0.022* | 0.303 | 0.887 |

| Tree-cutting banned in sacred places | 0.334 | 0.714 | 0.983 | 0.002* |

| Defending concessions | 1.000 | 0.027* | 0.346 | 0.619 |

| Short fallow/rotation period (3-5 years) | 0.027* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.915 |

| Long fallow/rotation period (15-20 years) | 0.694 | 0.637 | 0.700 | 0.211 |

| Use of dead wood | 0.051 | 0.006* | 0.545 | 0.227 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).