Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

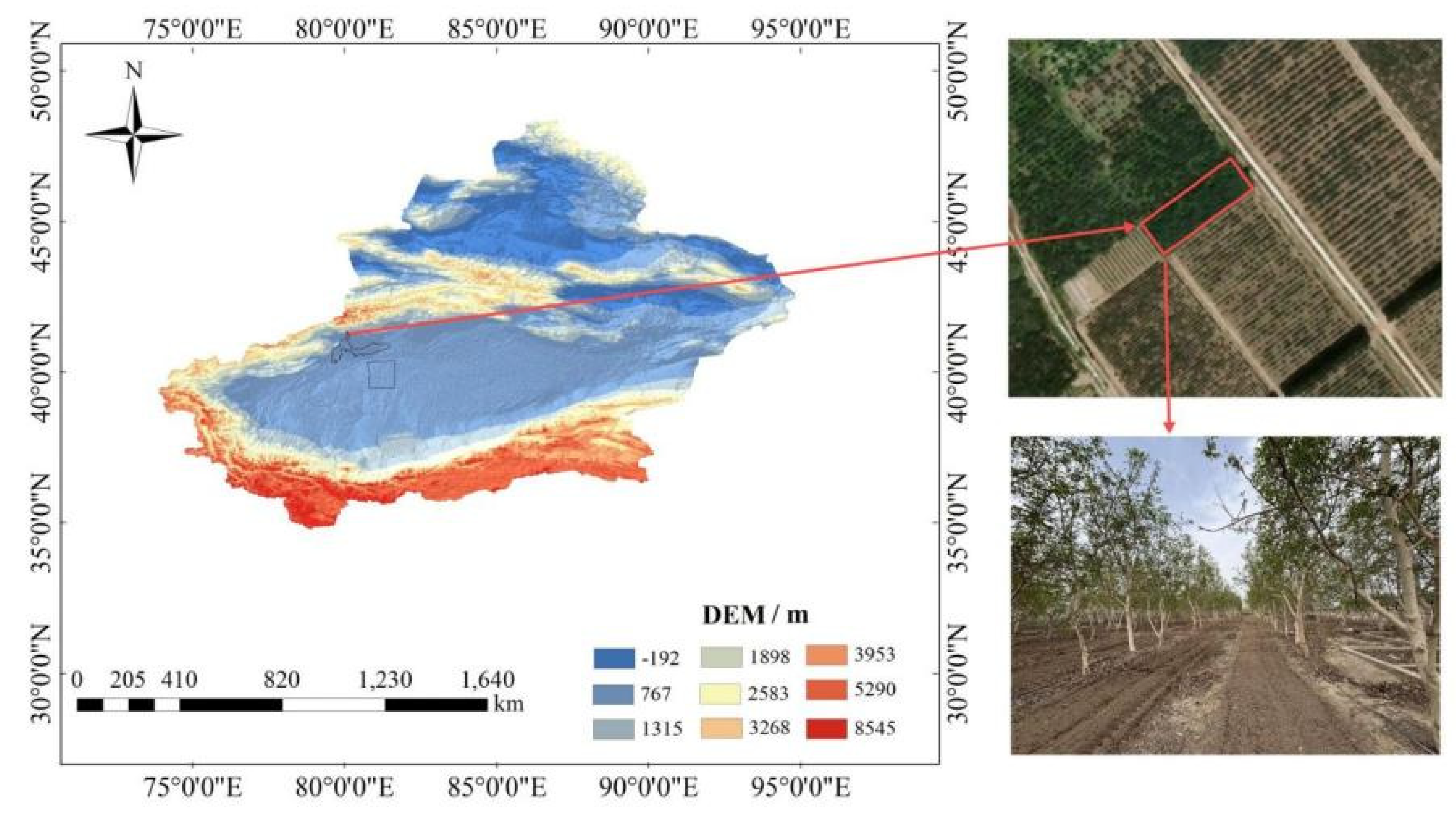

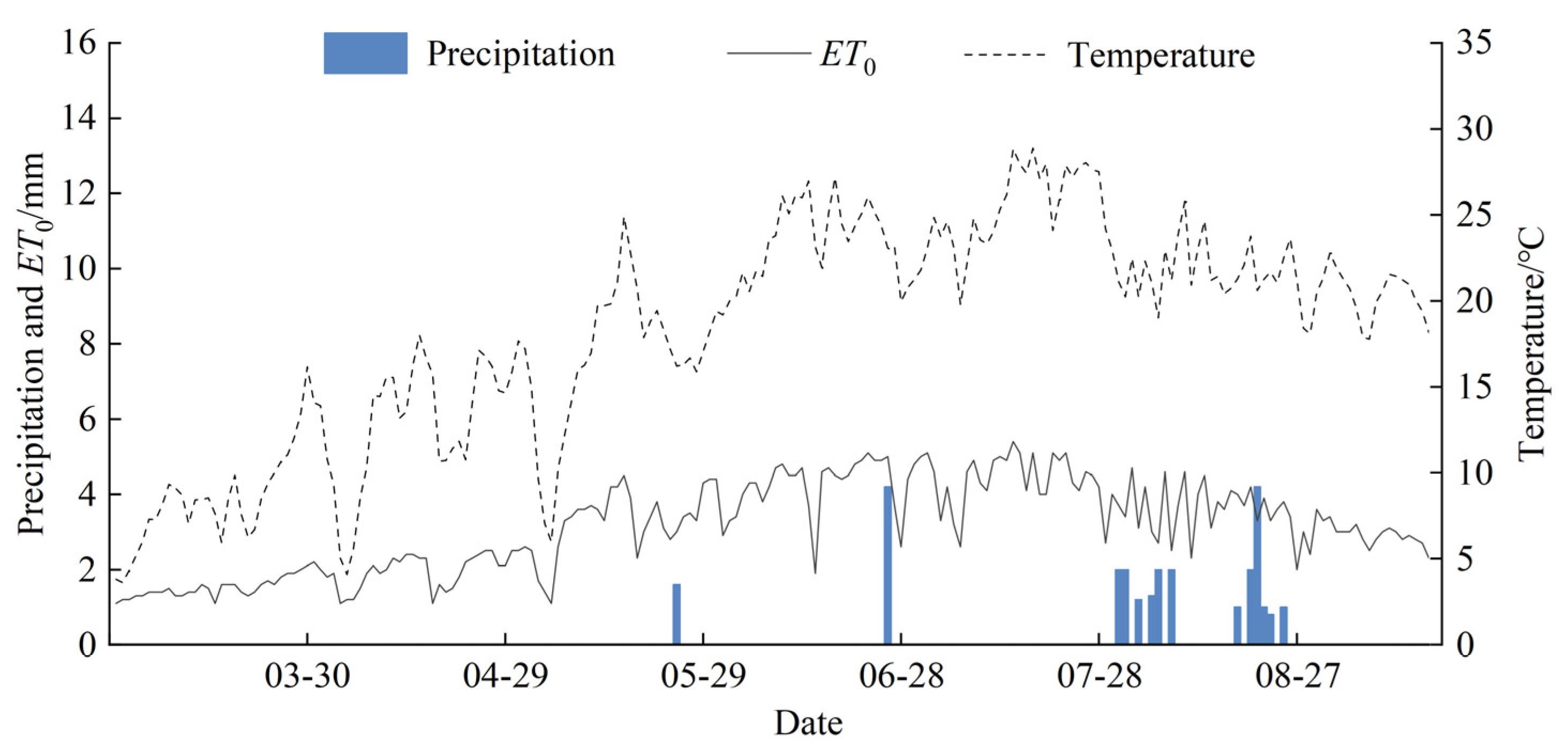

2.1. Site Description

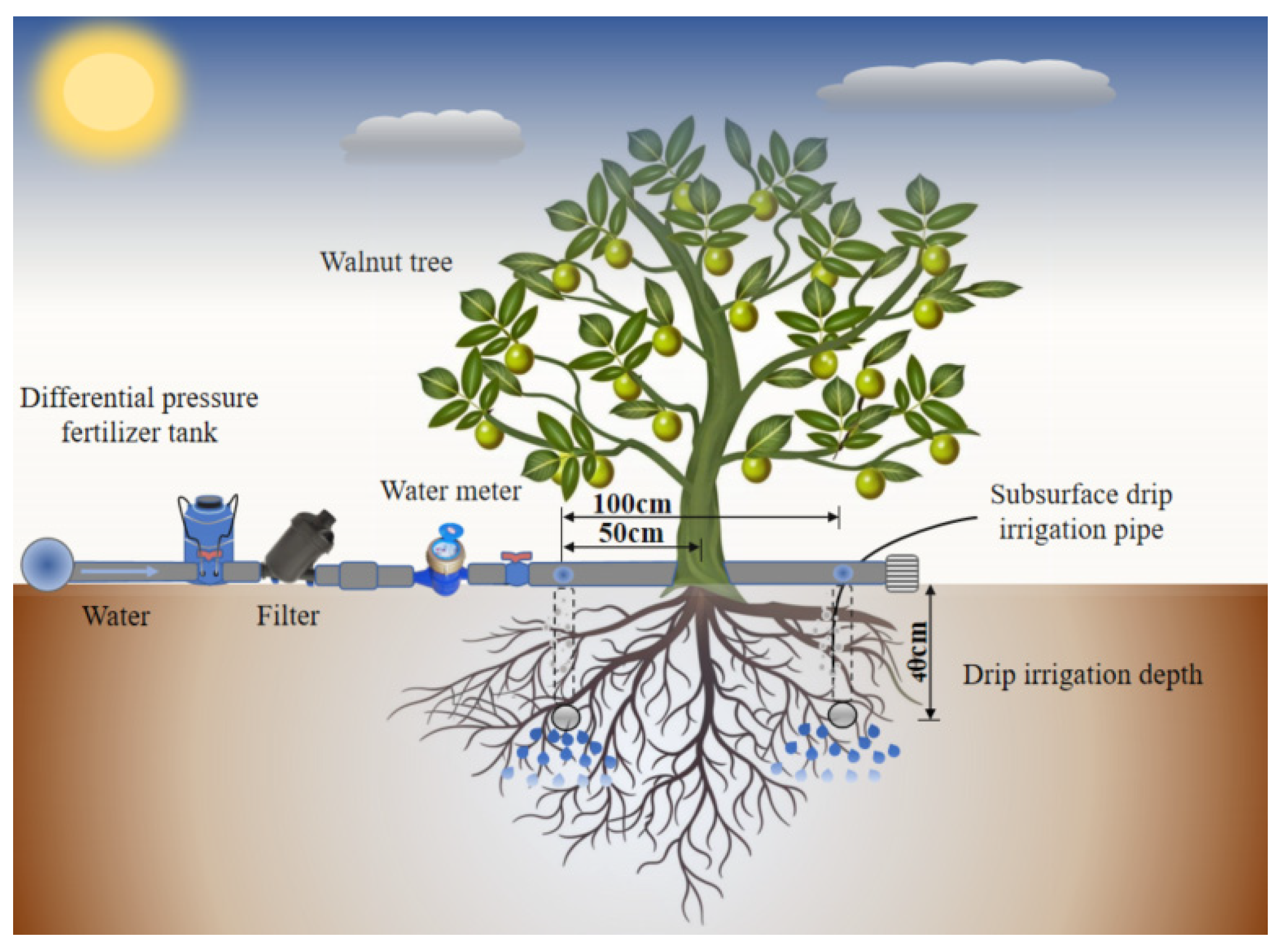

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Data Measurement and Method

2.3.1. Measurement of Growth Indicators

2.3.2. Measurement of Photosynthetic Parameters

2.3.3. Fruit Quality Indicators

2.3.4. Yield Measurement

2.3.5. Walnut Water Consumption

2.3.6. Efficiency Indicators

2.3.7. Soil Nitrate Nitrogen Residue

2.3.8. Meteorological Data

2.4. Development of Comprehensive Growth Index (CGI) and Comprehensive Photosynthesis Index (CPI)

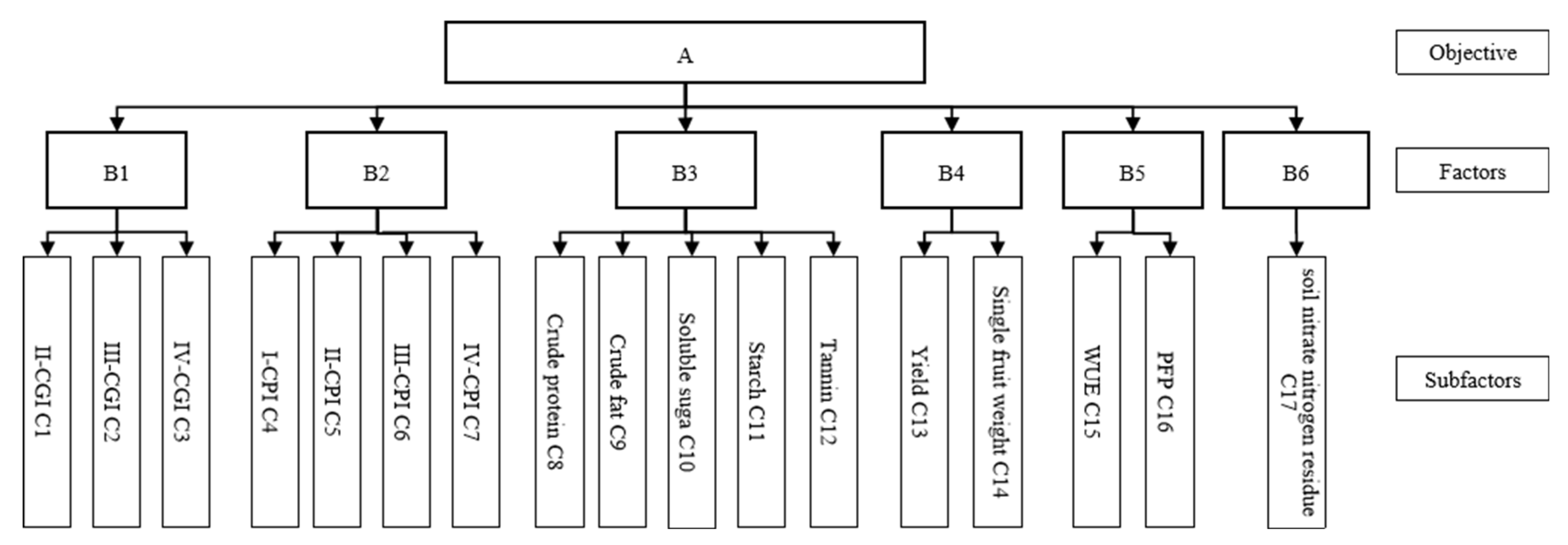

2.5. Comprehensive Growth Evaluation of Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts Using TOPSIS-GRA Methodology

2.6. Data processing

3. Results

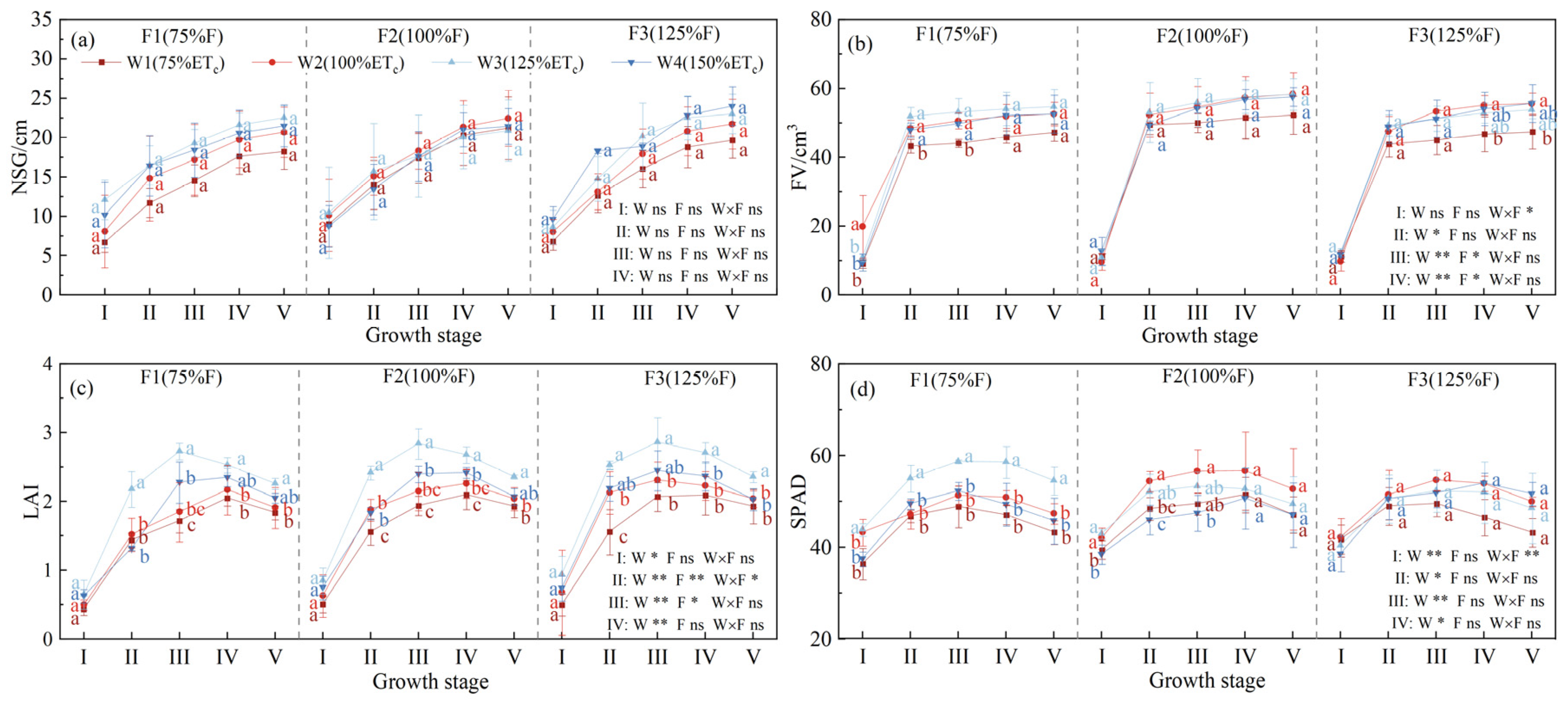

3.1. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Growth Indicators in Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

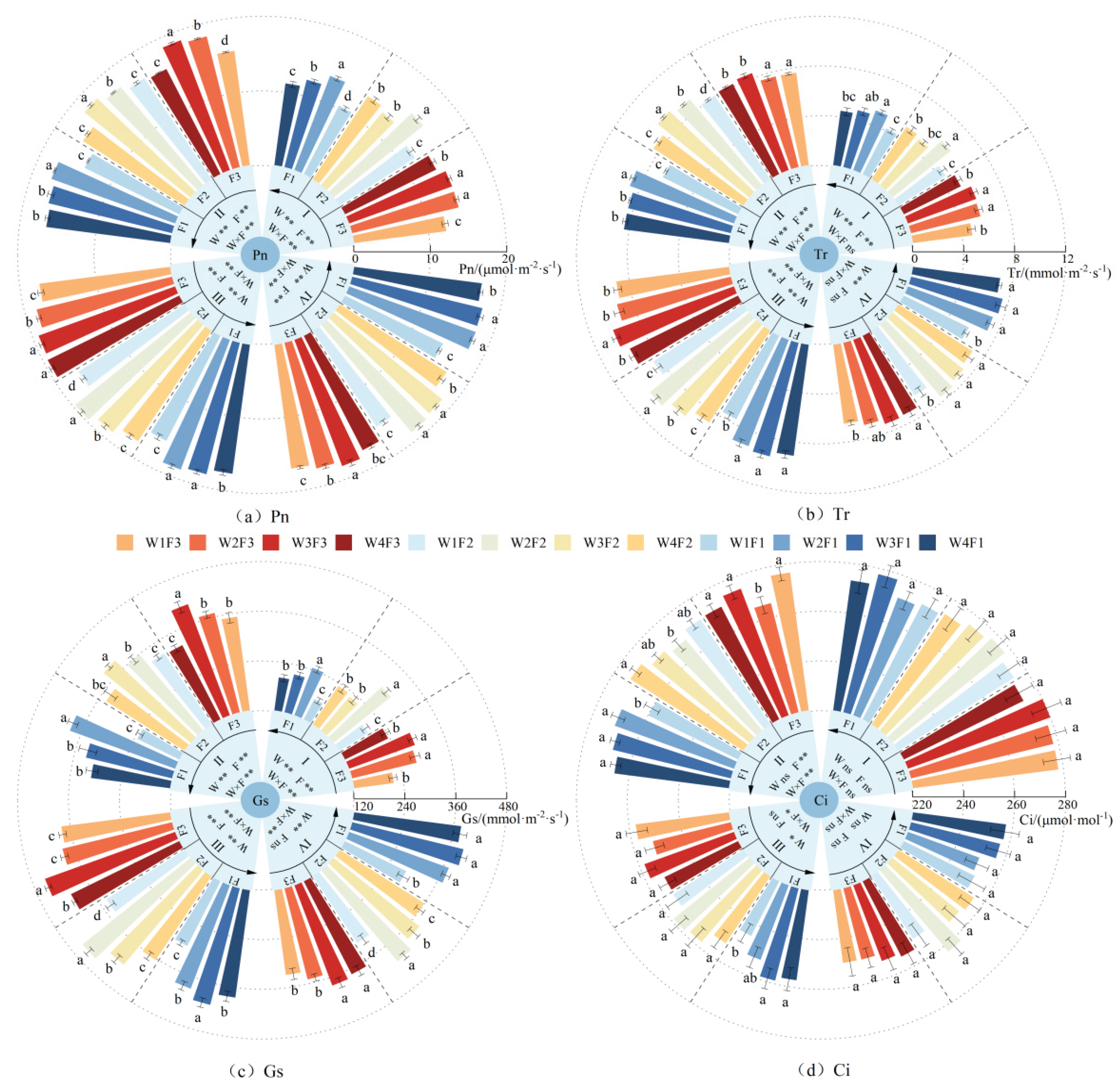

3.2. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Photosynthetic Indicators in Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

3.3. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Fruit Quality in Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

3.4. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Yield Components, Water Use Efficiency, and Partial Factor Productivity of Fertilizer in Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

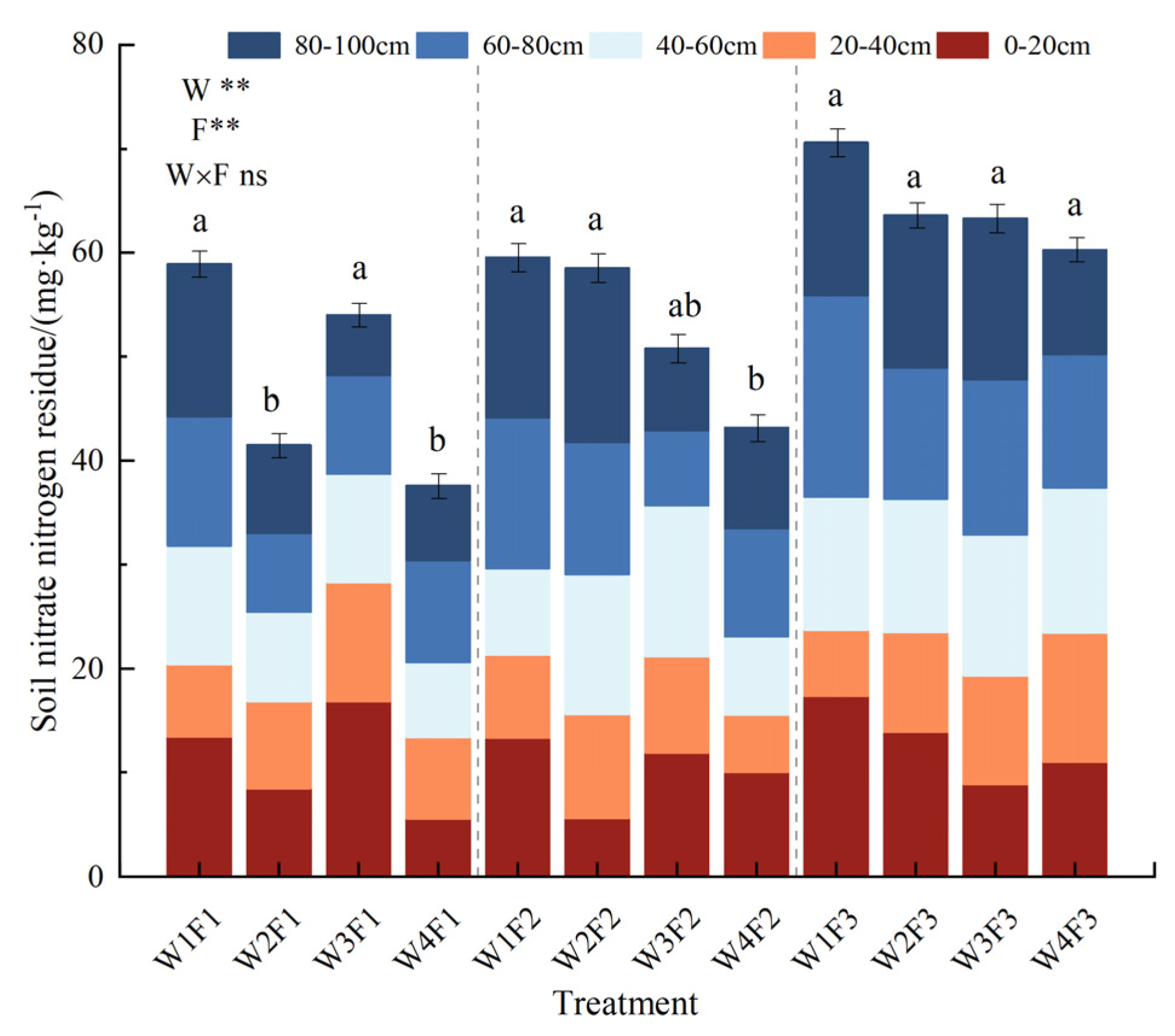

3.5. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Soil Nitrate Nitrogen Residue in Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

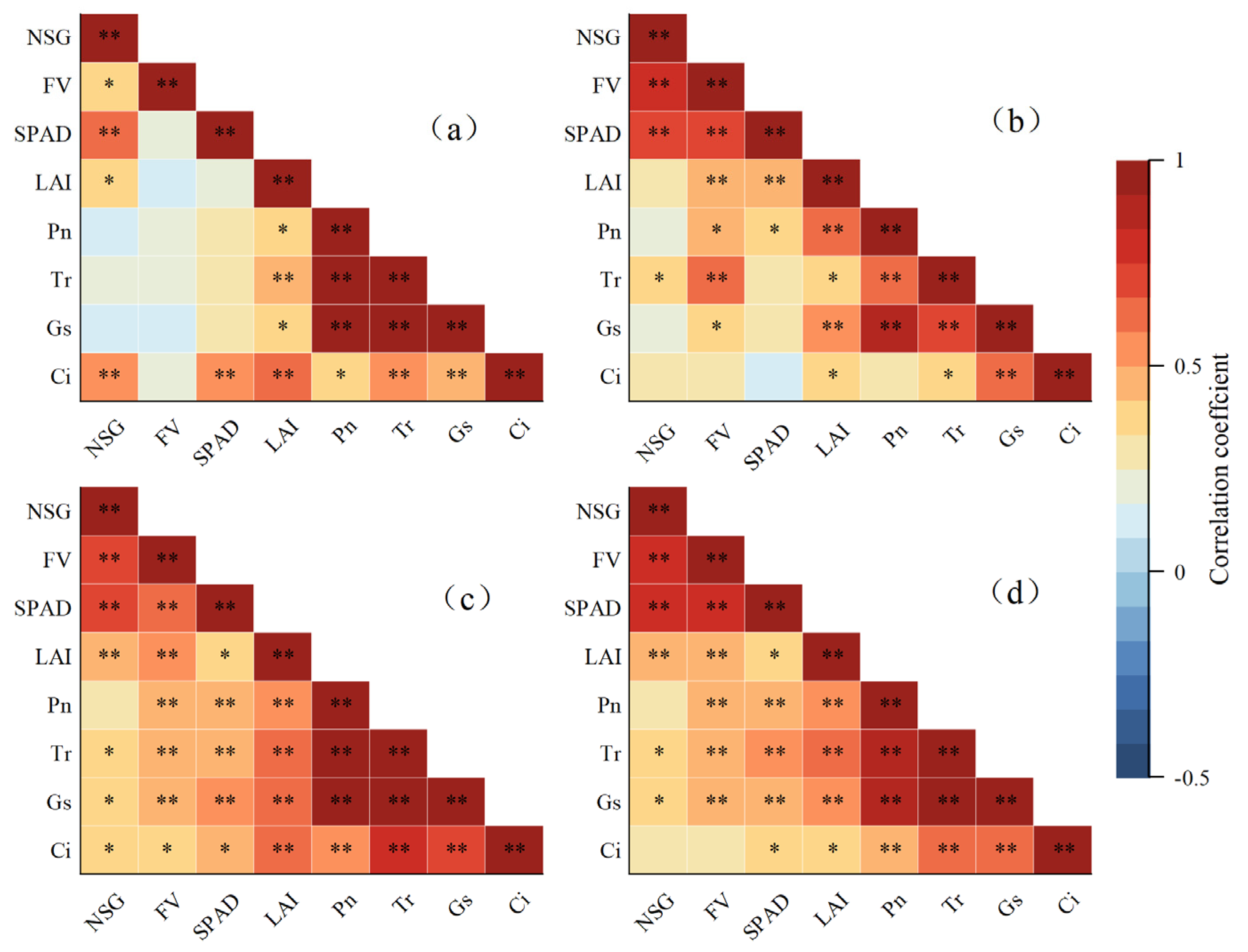

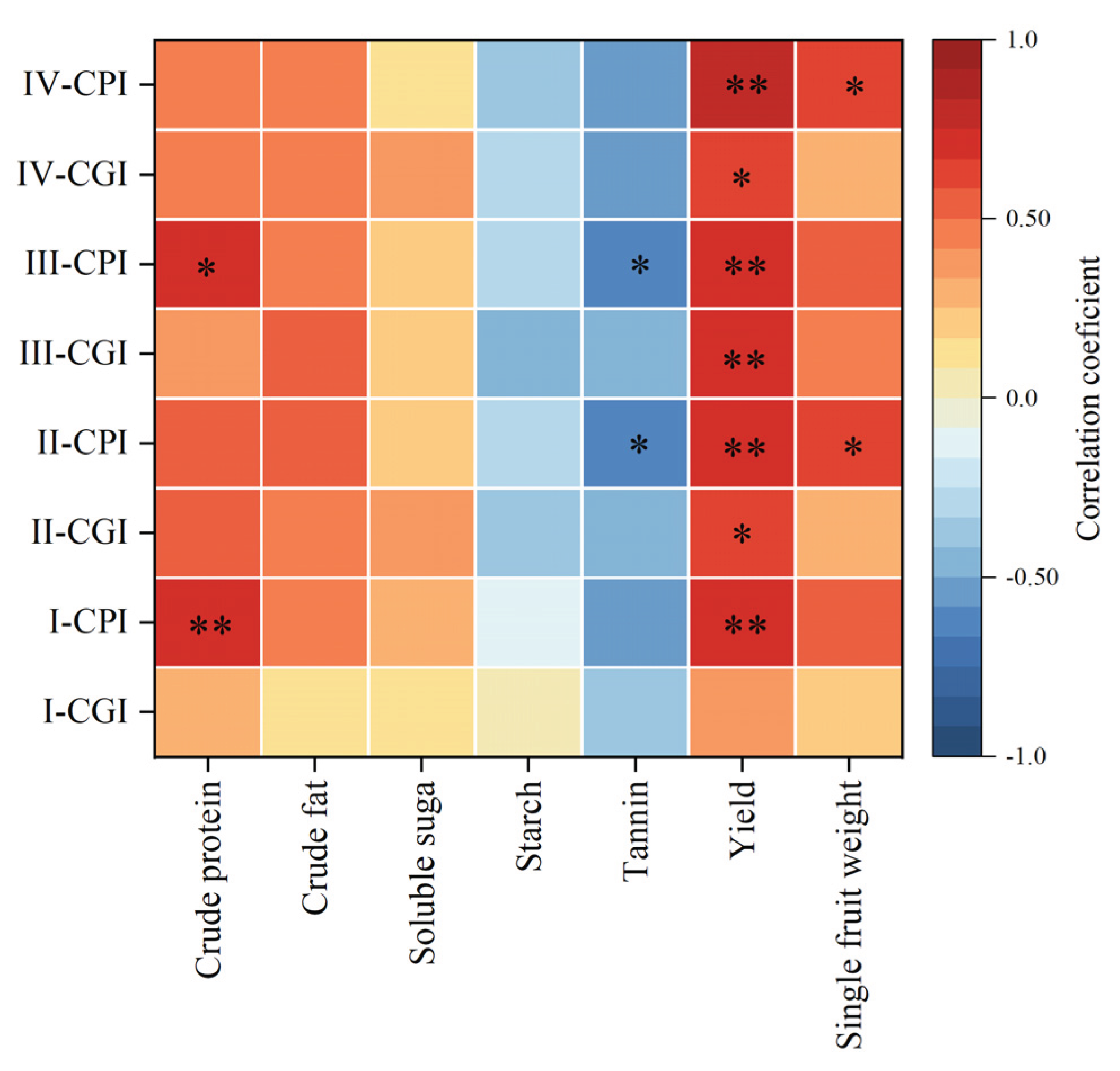

3.6. Effects of the Comprehensive Growth Index (CGI) and Comprehensive Photosynthesis Index (CPI) on Yield and Quality Across Walnut Growth Stages

3.7. Comprehensive Growth Evaluation of Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts Based on TOPSIS-GRA Coupled Model

3.7.1. Determination of Indicator Weights in the Comprehensive Evaluation System for Walnut Growth Stages

3.7.2. Comprehensive Growth Assessment of Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts Using the TOPSIS-GRA Method

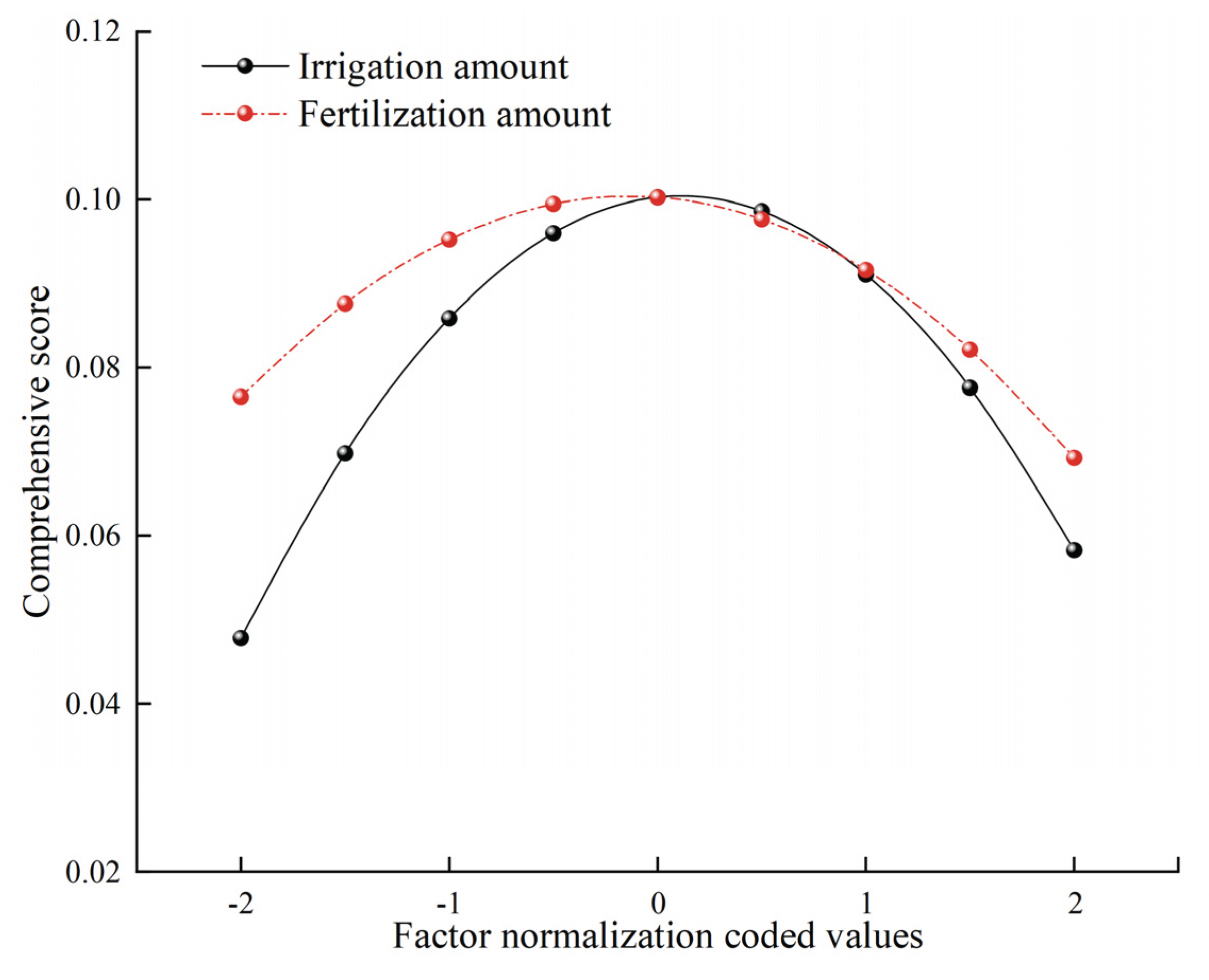

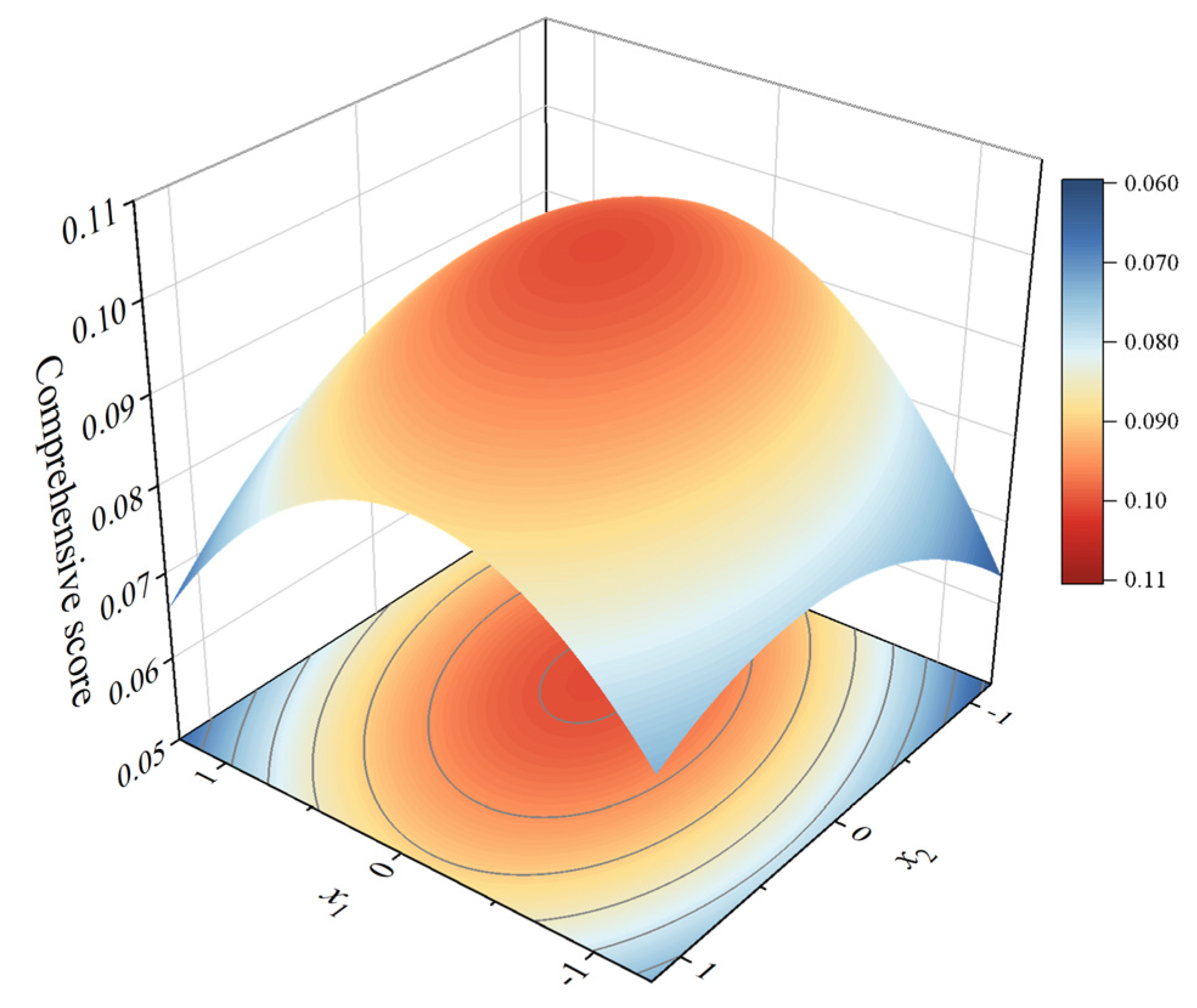

3.8. Water and Fertilizer Regulation Model for Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts Based on Comprehensive Evaluation

3.8.1. Analysis of Univariate and Marginal Effects of Water and Fertilizer

3.8.2. Optimal Water and Fertilizer Application Rates for Comprehensive Growth of Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Walnut Growth and Photosynthetic Parameters

4.2. Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Walnut Quality

4.3. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Interaction on Walnut Yield Components, Water and Partial Factor Productivity of Fertilizer, and Soil Nitrate Nitrogen

4.4. Comprehensive Growth Evaluation of Subsurface Drip-Irrigated Walnuts Based on the TOPSIS-GRA Coupled Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mortier, E., Lamotte, O., Martin-Laurent, F., Recorbet, G. Forty years of study on interactions between walnut tree and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Ni, Z., Wang, R., Zhao, B., Han, Y., Zheng, Y., Liu, F., Gong, Y., Tang, F., Liu, Y. The effects of cultivar and climate zone on phytochemical components of walnut (Juglans regia L.). Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, 2. [CrossRef]

- Guiqing, X., Jinyao, L., Haifang, H., Tuqiang, C. Effect of deficit irrigation on physiological, morphological and fruit quality traits of six walnut tree cultivars in the inland area of Central Asia. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 112951. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., He, X., Gong, P., Heng, T., Zhao, D., Wang, C., Chen, Q., Wei, J., Lin, P., Yang, G. Response of fragrant pear quality and water productivity to lateral depth and irrigation amount. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108652. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Zhang, J., Pei, D., Yu, L. Combined effects of water stress and salinity on growth, physiological, and biochemical traits in two walnut genotypes. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 176–187. [CrossRef]

- You, Y., Tian, H., Shi, H., Xu, R., Pan, S., Ren, W., Lu, C., Zhang, J., Yang, J., Miao, R., Pan, N., Bian, Z., Huang, Y., Yu, Q. Improving Crop Yield Simulation by Better Representing the Dynamic Crop Growth Processes and Management Practices. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2021, pp. GC25D-0688). [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W., Zhao, J. H., Fu, Q. P., Hong, M., Ma, Y. J. Effects of regulated deficit irrigation on the growth and yield of drip-irrigated walnut trees. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 186–190. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y. Study on the Effects of Regulated Deficit Irrigation on Physio-Ecological Characteristics and Root System Simulation of Drip-Irrigated Walnut Trees. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.Y. Soil Microbiological Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Long-Term Fertilization on Walnut Yield and Quality. PhD Dissertation, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W., Sun, J., Zhang, K., Mao, L., Gao, L., Hou, X., Cui, N., Kang, W., Gong, D. Optimizing drip fertigation management based on yield, quality, water and fertilizer use efficiency of wine grape in North China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108188. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Yu, S., Zhang, H., Lei, L., Liang, C., Chen, L., Su, D., Li, X. Deficit mulched drip irrigation improves yield, quality, and water use efficiency of watermelon in a desert oasis region. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 277, 108103. [CrossRef]

- ZHA, Y., CHEN, F., WANG, Z., JIANG, S., CUI, N. Effects of water and fertilizer deficit regulation with drip irrigation at different growth stages on fruit quality improvement of kiwifruit in seasonal arid areas of Southwest China. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 3042–3058. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Ding, G., Quan, W., Zhao, X., Tao, Q. Coupling optimization of water-fertilizer for coordinated development of the environment and growth of Pinus massoniana seedlings. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 300, 108895. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Y., Zhao, J. H., Pang, Y., Liao, K. Effects of regulated deficit irrigation on water consumption and yield of drip-irrigated walnut trees. Acta Agric. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2021, 30, 1674–1684. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G., Chen, S., Zhang, S., Chen, S., Liu, J., He, Q., Hu, T., Zhang, F. Responses of leaf nitrogen status and leaf area index to water and nitrogen application and their relationship with apple orchard productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 296, 108810. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. S., Karlen, D. L., Mitchell, J. P. A comparison of soil quality indexing methods for vegetable production systems in Northern California. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 25–45. [CrossRef]

- Qu, F., Zhang, Q., Jiang, Z., Zhang, C., Zhang, Z., Hu, X. Optimizing irrigation and fertilization frequency for greenhouse cucumber grown at different air temperatures using a comprehensive evaluation model. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 273, 107876. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Cai, Y. A Flexible Decision-Making Method for Green Supplier Selection Integrating TOPSIS and GRA Under the Single-Valued Neutrosophic Environment. IEEE Access. 2021, 9, 83025–83040. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, H., Li, J., He, X., Gong, P., Lin, E., Li, K., Li, L., Binley, A. Experimental study and multi–objective optimization for drip irrigation of grapes in arid areas of northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 232, 106039. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Ji, X., Li, A., Zheng, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. Effect of Persistent Salt Stress on the Physiology and Anatomy of Hybrid Walnut (Juglans major × Juglans regia) Seedlings. Plants.2024, 13, 1840. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Ma, L., Zhang, S., Zhao, L., Niu, X., Qin, L., Xiang, Y., Guo, J., Wu, Q. Effect of Water-Fertilizer Coupling on the Growth and Physiological Characteristics of Young Apple Trees. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 2506. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, P., Orsucci, S., Moser, M., Brilli, M., Giongo, L., Si-Ammour, A. Gene expression and metabolite accumulation during strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruit development and ripening. Planta. 2018, 248, 1143–1157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q., Li, H., Chen, J., Du, T. Fruit cracking in muskmelon: Fruit growth and biomechanical properties in different irrigation levels. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 293, 108672. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.R. Study on the Coupling Effects of Water and Fertilizer on Yield and Quality of Drip-Irrigated Walnut Trees. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T., Xu, G., Li, J., Hu, H. Hydraulic Trait Variation with Tree Height Affects Fruit Quality of Walnut Trees under Drought Stress. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 1647. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. F., Hao, H. L., Wang, S. W., Xing, C. J., Guo, T. Characteristics of Photoassimilares in Walnut Leaves and Their Transport to Fruit. Erwerbs-Obstbau. 2023, 65, 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Liang, Z., Li, Y., Wang, K., Nangia, V., Mo, F., Liu, Y. Advantageous spike-to-stem competition for assimilates contributes to the reduction in grain number loss in wheat spikes under water deficit stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108675. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q. Effects of Different Water and Fertilizer Combinations on the Growth, Yield, and Quality of ‘Centennial Seedless’ Grapevines in Yutian County. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C., Batke, S. P., Yiotis, C., Caballero, R., Soh, W. K., Murray, M., McElwain, J. C. (2018). Increasing stomatal conductance in response to rising atmospheric CO2. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 1137–1149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Q. Effects of Different Water and Fertilizer Combinations on the Ratio of Female to Male Inflorescences and Fruit Yield and Quality in Chestnut. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, W. Amino acid transport in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W., Zhang, C., Zhang, P., Zhao, Y., Guo, M., Li, Y., Chi, R., Chen, Y. Optimized Fertilizer–Water Management Improves Carrot Quality and Soil Nutrition and Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the North China Plain. Horticulturae. 2024, 10, 151. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Chen, X., Zhang, J., Yao, Y. Nitrogen-rich animal and plant wastes as fertilizer improve the soil carbon/nitrogen ratio and plant branching and thickening of young walnut trees under deficit irrigation conditions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 2966–2981. [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.P. Effects of Coupled Water-Fertilizer-Heat under Furrow Drip Irrigation on Yield Increase, Quality Improvement, Water Saving, and Salt Control in Oil Sunflower. Master’s Thesis, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C., Pang, X., Chen, K., Gong, R., Xu, G., Wang, X. The water adaptability of Jatropha curcas is modulated by soil nitrogen availability. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012, 47, 71–81. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. M., Ma, L. S., Sun, Q. L., Chen, J. G., Li, J. C., Su, Y. M.,... Wu, Q. Comprehensive regulation of water and nitrogen for apple based on multi-objective comprehensive evaluation. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 3654–3670. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, Y., Xu, Y., Zheng, Y., Liu, B., Li, Q. Alternate drip irrigation with moderate nitrogen fertilization improved photosynthetic performance and fruit quality of cucumber in solar greenhouse. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 308, 111579. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zhang, Q., Chen, J. L., Zhang, H., Gao, S., Xu, C. Z. Effects of water and fertilizer coupling on photosynthetic characteristics and quality of walnut. J. Fruit Sci. 2015, 32, 1170–1178. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Z. Study on the Coupling Effects of Water and Fertilizer under Subsurface Drip Irrigation for Labor-Saving Cultivation of Korla Fragrant Pear. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E., Liu, H., He, X., Li, X., Gong, P., Li, L. Water–Nitrogen Coupling Effect on Drip-Irrigated Dense Planting of Dwarf Jujube in an Extremely Arid Area. Agronomy. 2019, 9, 561. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J., Xue, Z., Shen, X., Yi, R., Chen, J., Li, Q., Hou, X., Miao, H. Effects of Different Water and Nitrogen Supply Modes on Peanut Growth and Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiency under Mulched Drip Irrigation in Xinjiang. Effects of Different Water and Nitrogen Supply Modes on Peanut Growth and Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiency under Mulched Drip Irrigation in Xinjiang. Plants. 2023, 12, 3368. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., Wang, H., Zhang, F., Wang, X., Liao, Z., Zhang, S., Yang, Q., Fan, J. Effects of irrigation and fertilization regimes on tuber yield, water-nutrient uptake and productivity of potato under drip fertigation in sandy regions of northern China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108459. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X., Fan, J., Zhang, F., Hu, W., Xiang, Y. Optimization of water and nitrogen management to improve seed cotton yield, water productivity and economic benefit of mulched drip-irrigated cotton in southern Xinjiang, China. Field Crops Res. 2024, 308, 109301. [CrossRef]

- Abudurezike, A., Liu, X., Aikebaier, G., Shawuer, A., Tian, X. Effect of different irrigation and fertilizer coupling on the liquiritin contents of the licorice in Xinjiang arid area. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111451. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T., Zhang, J., Du, L., Ding, L., Zhang, R., Liu, X., Ren, F., Yin, M., Yang, R., Tian, P., Gan, K., Yong, T., Li, Q., Li, F., Li, X. Comprehensive evaluation of the water-fertilizer coupling effects on pumpkin under different irrigation volumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Irmak, S., Mohammed, A. T., Drudik, M. Maize nitrogen uptake, grain nitrogen concentration and root-zone residual nitrate nitrogen response under center pivot, subsurface drip and surface (furrow) irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108421. [CrossRef]

- LU, Y., KANG, T., GAO, J., CHEN, Z., ZHOU, J. Reducing nitrogen fertilization of intensive kiwifruit orchards decreases nitrate accumulation in soil without compromising crop production. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1421–1431. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Feng, Z., Kong, T., Xie, J., Zhang, Z. Optimal water and fertilizer amount for balancing greenhouse melon production efficiency and soil ecology based on TOPSIS-GRA coupling model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109797. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Xiang, L., Liu, Y., Jing, D., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Li, W., Wang, X., Li, T., Li, J. Optimizing irrigation schedules of greenhouse tomato based on a comprehensive evaluation model. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108741. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M., Zhao, J., Yang, T., Liu, F., Yuan, Y., Ma, S., Chang, Z. Estimating comprehensive growth index for drip-irrigated spring maize in junggar basin via satellite imagery and machine learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109651. [CrossRef]

- Effects of Different Water and Nitrogen Supply on Yield and Quality of Oasis Jujube under Sand Tube Irrigation. PhD Dissertation, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., Zuo, D., Wang, H., Xu, Z., Wang, G., Yang, H. Assessment of agricultural drought based on multi-source remote sensing data in a major grain producing area of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 278, 108142. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z. K., Zhao, J. H., Wang, F., Hua, J. D. Comprehensive evaluation of water-fertilizer coupling effects for walnut under subsurface drip irrigation. J. Northwest A&F Univ. 2025, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H. Research on Micro-Irrigation Technology and Root Zone Soil Moisture Simulation for Mature Walnut Trees in Arid Regions. PhD Dissertation, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q. P., Zhao, J. H., Ma, L., Ma, Y. J. Optimal drip irrigation water and fertilizer amounts for densely planted walnut in the northwest margin of Tarim Basin. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 40, 253–259. [CrossRef]

- Piao, H.Q. Water and Fertilizer Coupling Parameters for Increasing Yield and Improving Quality of ‘Wen 185’ Walnut. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y., Chen, M., Wang, X. Enhancing water use efficiency and fruit quality in jujube cultivation: A review of advanced irrigation techniques and precision management strategies. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109243. [CrossRef]

| Experimental treatment |

Irrigation allowance/ (m3·hm-2) |

Irrigation quota/ (m3·hm-2) |

Fertilizer application amount/(kg·hm-2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P2O5 | K2O | |||

| W1F1 | 75%ETc | 3 993 | 270 | 240 | 300 |

| W2F1 | 100%ETc | 5 328 | 270 | 240 | 300 |

| W3F1 | 125%ETc | 6 656 | 270 | 240 | 300 |

| W4F1 | 150%ETc | 6 985 | 270 | 240 | 300 |

| W1F2 | 75%ETc | 3 993 | 360 | 320 | 400 |

| W2F2 | 100%ETc | 5 328 | 360 | 320 | 400 |

| W3F2 | 125%ETc | 6 656 | 360 | 320 | 400 |

| W4F2 | 150%ETc | 6 985 | 360 | 320 | 400 |

| W1F3 | 75%ETc | 3 993 | 450 | 400 | 500 |

| W2F3 | 100%ETc | 5 328 | 450 | 400 | 500 |

| W3F3 | 125%ETc | 6 656 | 450 | 400 | 500 |

| W4F3 | 150%ETc | 6 985 | 450 | 400 | 500 |

| Irrigation treatment | Fertilization treatment | Crude protein /(g·kg-1) |

Crude fat /(g·kg-1) |

Soluble sugar /(g·kg-1) |

Starch /(g·kg-1) |

Tannin /(g·kg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | W1 | 183.79±2.73d | 8.40±1.14c | 23.52±1.06a | 12.40±0.45a | 20.47±0.73a |

| W2 | 205.47±2.61a | 10.08±1.07bc | 18.69±1.16b | 10.94±0.31b | 16.06±0.93b | |

| W3 | 196.33±2.81b | 16.05±1.48a | 17.40±1.18b | 5.43±0.49d | 15.59±0.96b | |

| W4 | 189.19±2.64c | 11.16±1.19b | 17.57±1.15b | 9.97±0.51c | 13.03±0.74c | |

| F2 | W1 | 222.03±2.95b | 12.48±1.40a | 25.04±1.34a | 8.36±0.32b | 11.73±0.68b |

| W2 | 238.64±2.54a | 13.51±1.21a | 25.54±1.07a | 7.54±0.23c | 10.35±0.82c | |

| W3 | 214.76±3.00c | 12.51±1.37a | 24.19±1.38a | 8.38±0.43b | 14.50±0.68a | |

| W4 | 193.02±2.86d | 9.40±1.11b | 17.26±1.06b | 13.29±0.28a | 15.04±0.67a | |

| F3 | W1 | 214.21±2.78b | 15.15±1.22ab | 14.47±1.21d | 8.68±0.31b | 15.86±0.55a |

| W2 | 219.44±2.60b | 16.73±1.28a | 21.43±1.03c | 8.57±0.42b | 16.11±0.72a | |

| W3 | 240.44±3.01a | 14.29±1.22bc | 27.86±1.15a | 11.45±0.21a | 9.35±0.53c | |

| W4 | 241.72±2.85a | 12.02±1.20c | 24.74±1.33b | 11.53±0.50a | 14.51±0.73b | |

| F | W | 57.82** | 13.32** | 12.49** | 40.02** | 23.48** |

| F | 498.74** | 21.50** | 32.30** | 186.52** | 65.57** | |

| W×F | 96.29** | 10.55** | 54.13** | 52.67** | 55.32** |

| Irrigation treatment | Fertilization treatment | Yield /kg·hm-2 |

Water use efficiency/kg·m-3 | Partial fertilizer productivity | Single fruit weight/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | W1 | 2776.23±248.23b | 0.75±0.08b | 3.43±0.31b | 7.94±0.71b |

| W2 | 3163.21±146.06a | 0.89±0.02a | 3.91±0.18a | 10.87±0.19a | |

| W3 | 3205.16±95.34a | 0.89±0.03a | 3.96±0.12a | 10.28±0.26a | |

| W4 | 3223.42±222.94a | 0.88±0.06a | 3.98±0.28a | 10.79±0.9a | |

| F2 | W1 | 3113.77±193.53b | 0.92±0.06a | 2.88±0.18b | 10.32±0.73b |

| W2 | 3801.4±51.56a | 0.86±0.04ab | 3.52±0.05a | 11.73±0.12a | |

| W3 | 3796.44±303.76a | 0.8±0.07b | 3.52±0.28a | 11.56±0.41a | |

| W4 | 3287.71±218.64b | 0.68±0.05c | 3.04±0.2b | 10.91±0.44ab | |

| F3 | W1 | 3012.84±123.16b | 0.82±0.03a | 2.23±0.09b | 10.4±0.41ab |

| W2 | 3708.15±460.05a | 0.74±0.08a | 2.75±0.34a | 11.64±1.38a | |

| W3 | 3325.78±228.47ab | 0.59±0.03b | 2.46±0.17ab | 9.31±0.6b | |

| W4 | 3279.75±151.21ab | 0.53±0.03b | 2.43±0.11ab | 9.64±0.81b | |

| F | W | 11.43** | 13.94** | 11.63** | 11.52** |

| F | 9.70** | 39.88** | 123.19** | 9.79** | |

| W×F | 1.53 | 11.01** | 1.58 | 5.46** |

| Growth stage | Principal component | Variance | Contribution rate | NSG | FV | SPAD | LAI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | PC1 | 39.51 | 39.51 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.17 | |

| PC2 | 26.26 | 65.77 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||

| PC3 | 25.68 | 91.45 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.98 | ||

| II | PC1 | 43.62 | 43.62 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 0.16 | |

| PC2 | 26.91 | 70.52 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.97 | ||

| PC3 | 23.81 | 94.33 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 0.18 | ||

| III | PC1 | 33.79 | 33.79 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.19 | |

| PC2 | 32.80 | 66.60 | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 0.24 | ||

| PC3 | 26.46 | 93.05 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.95 | ||

| IV | PC1 | 35.19 | 35.19 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.19 | |

| PC2 | 33.11 | 68.30 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.16 | ||

| PC3 | 26.78 | 95.08 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.97 | ||

| I-CGI | CGI=0.432×SPAD+0.287×FV+0.281×LAI | |||||||

| II-CGI | CGI=0.462×NSG+0.285×LAI+0.252×SPAD | |||||||

| III-CGI | CGI=0.363×SPAD+0.353×FV+0.284×LAI | |||||||

| IV-CGI | CGI=0.370×NSG+0.348×SPAD+0.282×LAI | |||||||

| Growth stage | Principal component | Variance | Contribution rate | Pn | Tr | Gs | Ci |

| I | PC1 | 70.46 | 70.46 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.24 |

| PC2 | 28.60 | 99.07 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.97 | |

| II | PC1 | 57.35 | 57.35 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.21 |

| PC2 | 31.39 | 88.74 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.98 | |

| III | PC1 | 62.93 | 62.93 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.34 |

| PC2 | 35.29 | 98.22 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.94 | |

| IV | PC1 | 65.30 | 65.30 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.28 |

| PC2 | 32.12 | 97.42 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.96 | |

| I-CPI | CPI=0.711×Pn+0.289×Ci | ||||||

| II-CPI | CPI=0.646×Pn+0.354×Ci | ||||||

| III-CPI | CPI=0.641×Pn+0.359×Ci | ||||||

| IV-CPI | CPI=0.670×Pn+0.330×Ci | ||||||

| Consistency test parameter |

Local weights |

Subjective weight |

Objective weight |

Combination weight |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CR=0.034<0.1 | 0.075 | 0.075 | — | — |

| 0.108 | 0.108 | ||||

| 0.193 | 0.193 | ||||

| 0.352 | 0.352 | ||||

| 0.211 | 0.211 | ||||

| 0.061 | 0.061 | ||||

| B1 | CR=0.051<0.1 | 0.159 | 0.012 | 0.052 | 0.016 |

| 0.589 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.045 | ||

| 0.252 | 0.019 | 0.048 | 0.022 | ||

| B2 | CR=0.012<0.1 | 0.229 | 0.025 | 0.049 | 0.027 |

| 0.137 | 0.015 | 0.038 | 0.017 | ||

| 0.556 | 0.060 | 0.040 | 0.058 | ||

| 0.079 | 0.009 | 0.038 | 0.011 | ||

| B3 | CR=0.017<0.1 | 0.219 | 0.042 | 0.069 | 0.045 |

| 0.109 | 0.021 | 0.063 | 0.025 | ||

| 0.190 | 0.037 | 0.078 | 0.041 | ||

| 0.190 | 0.037 | 0.059 | 0.039 | ||

| 0.291 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 0.055 | ||

| B4 | CR=0.000<0.1 | 0.667 | 0.235 | 0.045 | 0.215 |

| 0.333 | 0.117 | 0.051 | 0.111 | ||

| B5 | CR=0.000<0.1 | 0.667 | 0.140 | 0.094 | 0.136 |

| 0.333 | 0.070 | 0.098 | 0.073 | ||

| B6 | CR=0.000<0.1 | 1.000 | 0.061 | 0.088 | 0.064 |

| Treatment | TOPSIS | TOPSIS-GRA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| W1F3 | 0.369 | 10 | 0.069 | 11 |

| W2F3 | 0.493 | 7 | 0.086 | 5 |

| W3F3 | 0.471 | 8 | 0.085 | 7 |

| W4F3 | 0.354 | 11 | 0.073 | 10 |

| W1F2 | 0.526 | 5 | 0.085 | 8 |

| W2F2 | 0.679 | 1 | 0.104 | 1 |

| W3F2 | 0.596 | 3 | 0.095 | 3 |

| W4F2 | 0.403 | 9 | 0.074 | 9 |

| W1F1 | 0.301 | 12 | 0.059 | 12 |

| W2F1 | 0.516 | 6 | 0.085 | 6 |

| W3F1 | 0.605 | 2 | 0.096 | 2 |

| W4F1 | 0.565 | 4 | 0.089 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).