Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Treatment

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization

2.2.1. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

2.2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3. Structural and Mechanical Characterization

2.3.1. Macro- and Microphotography

2.3.2. Tensile Testing

3. Results

3.1. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

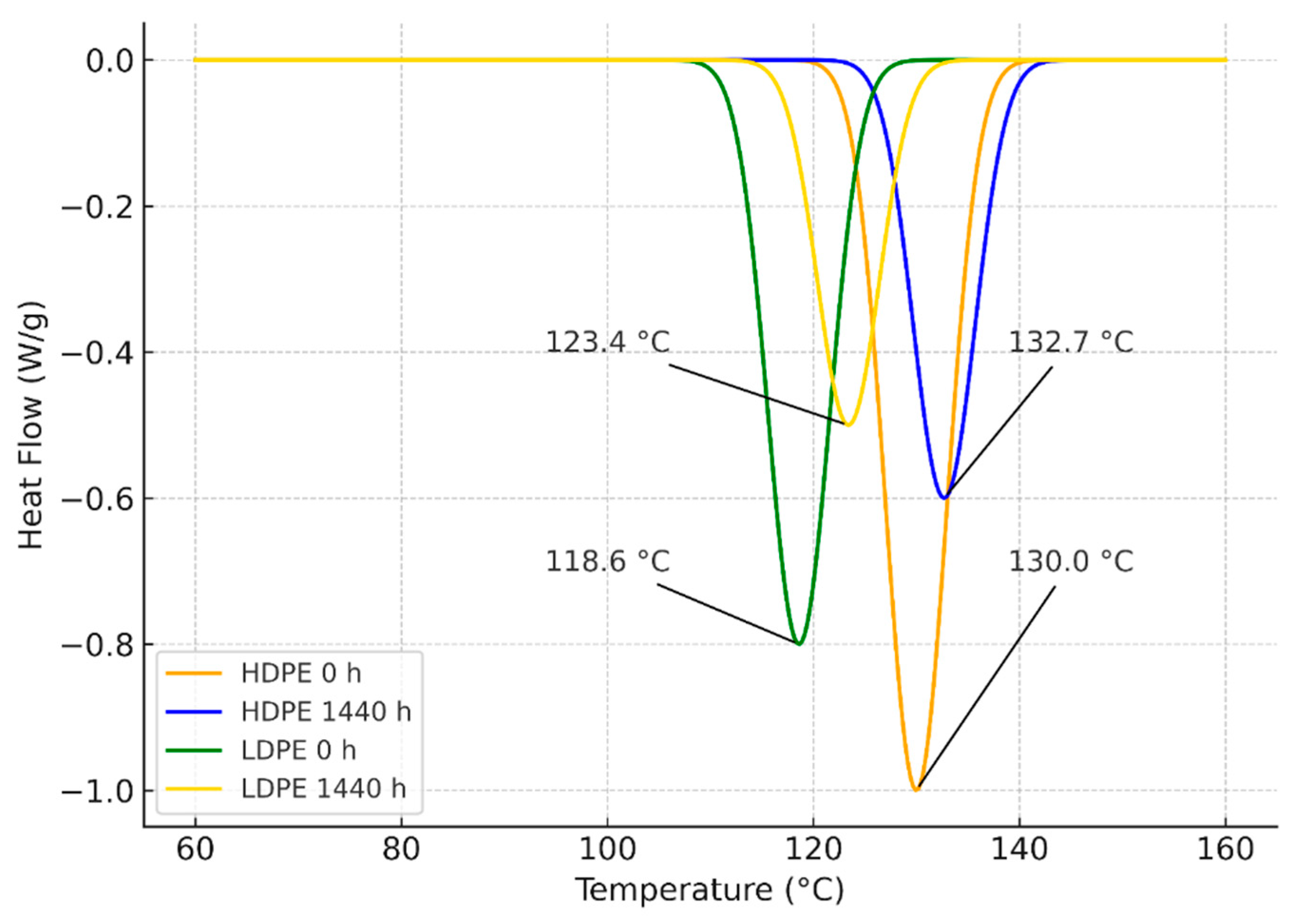

3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

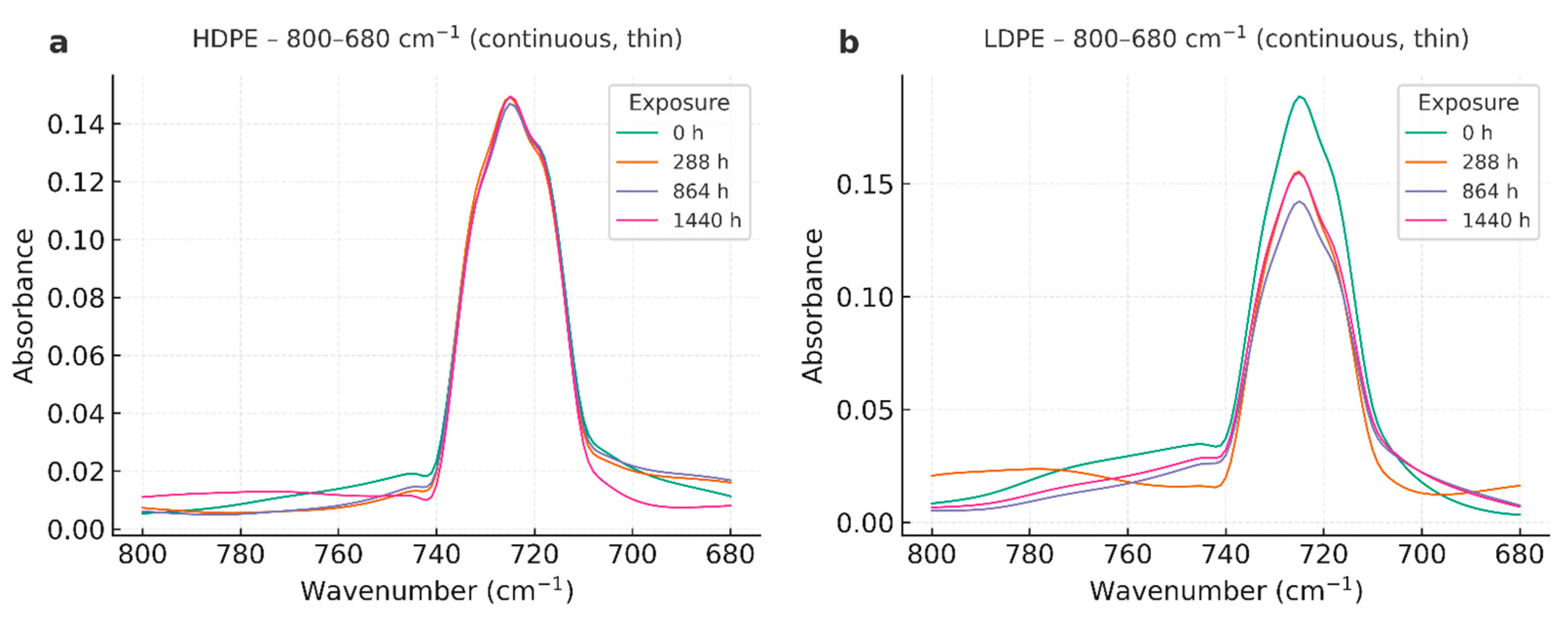

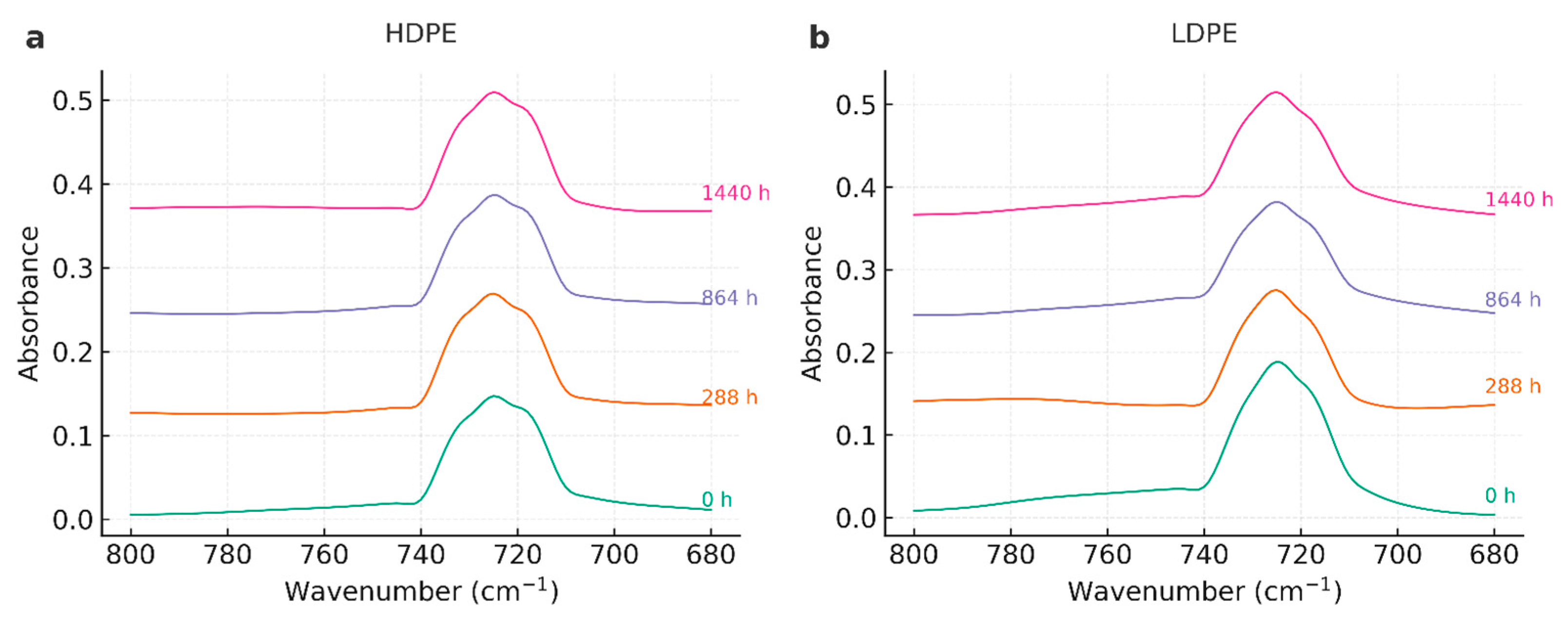

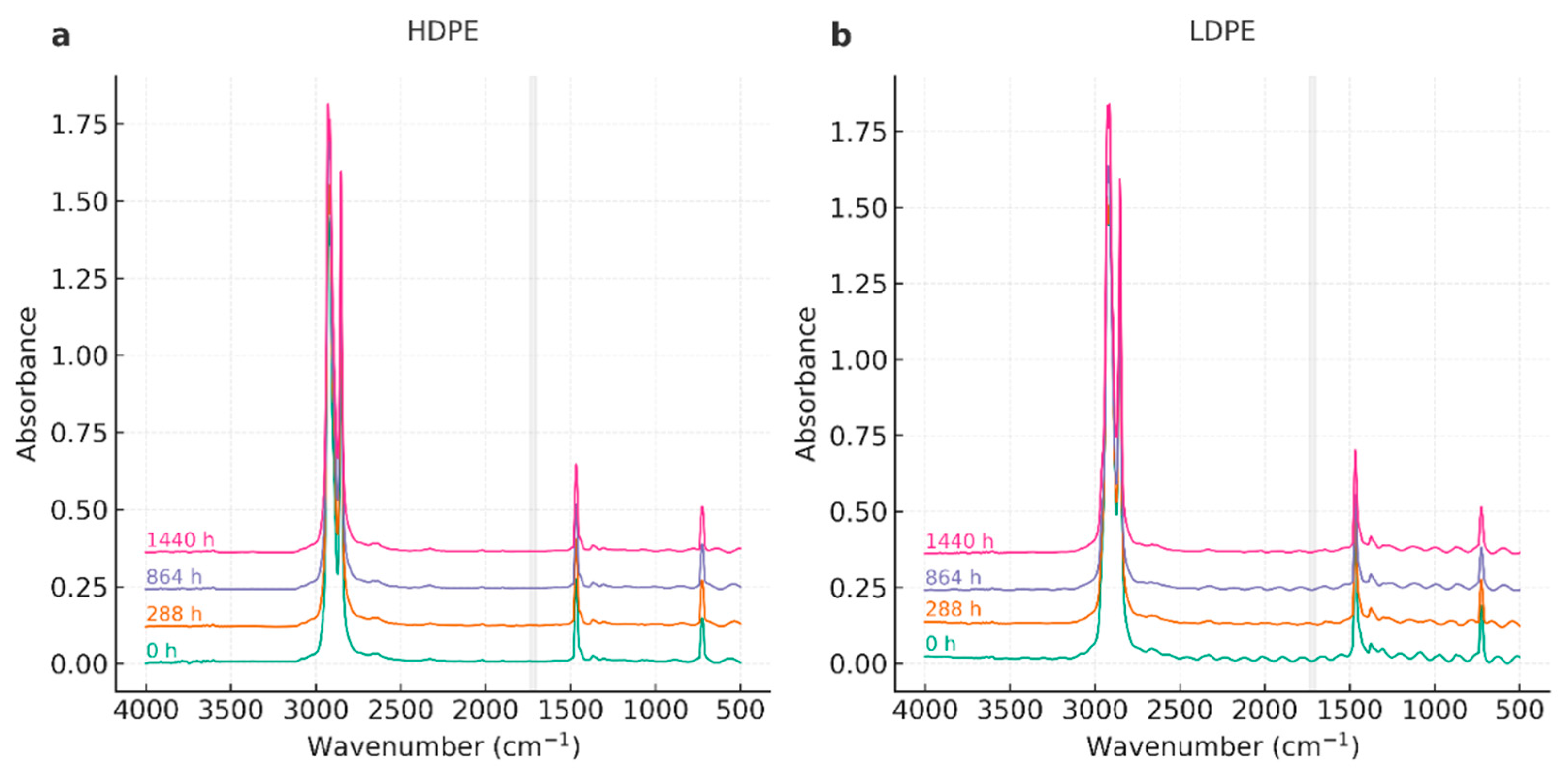

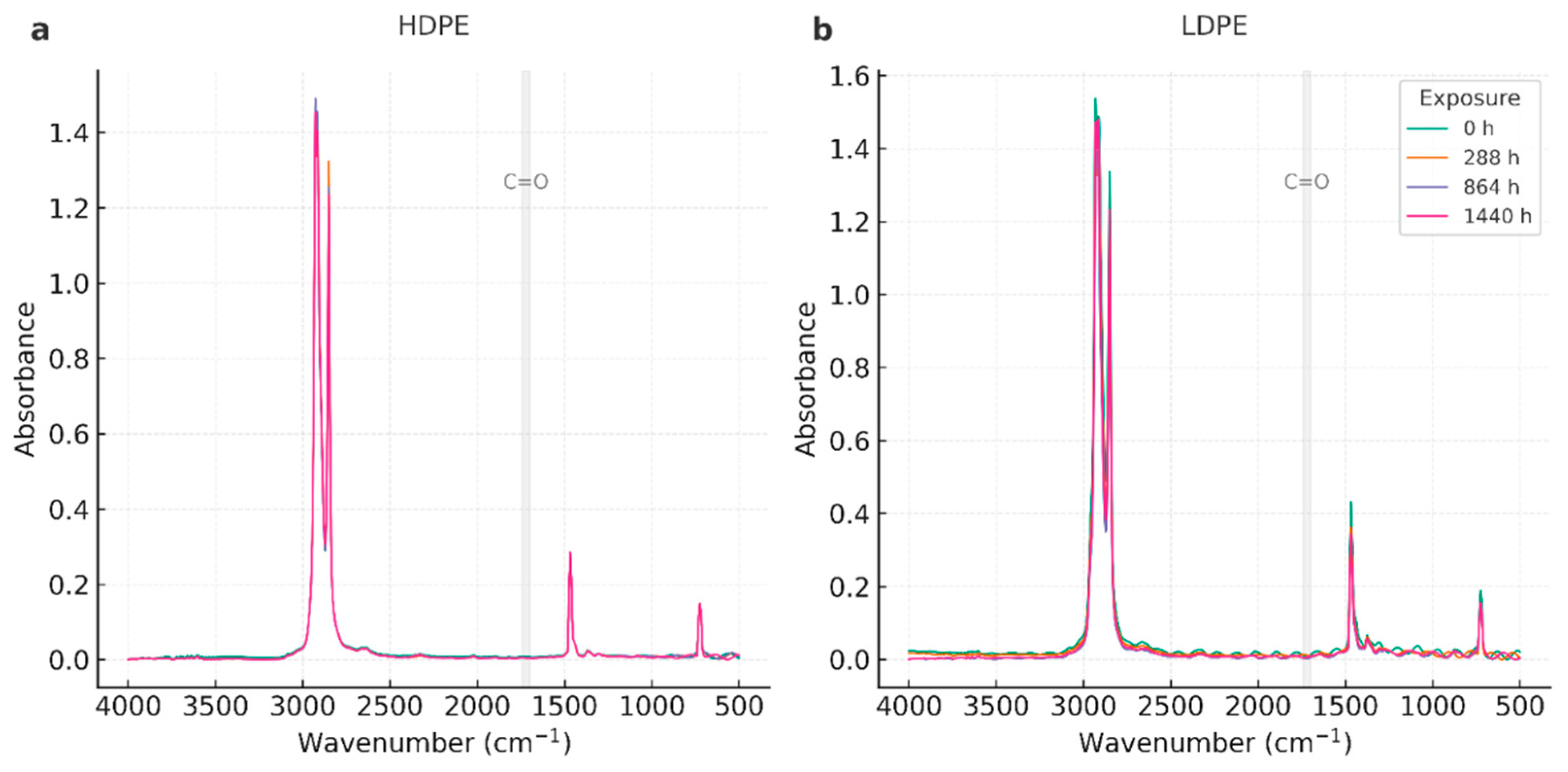

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

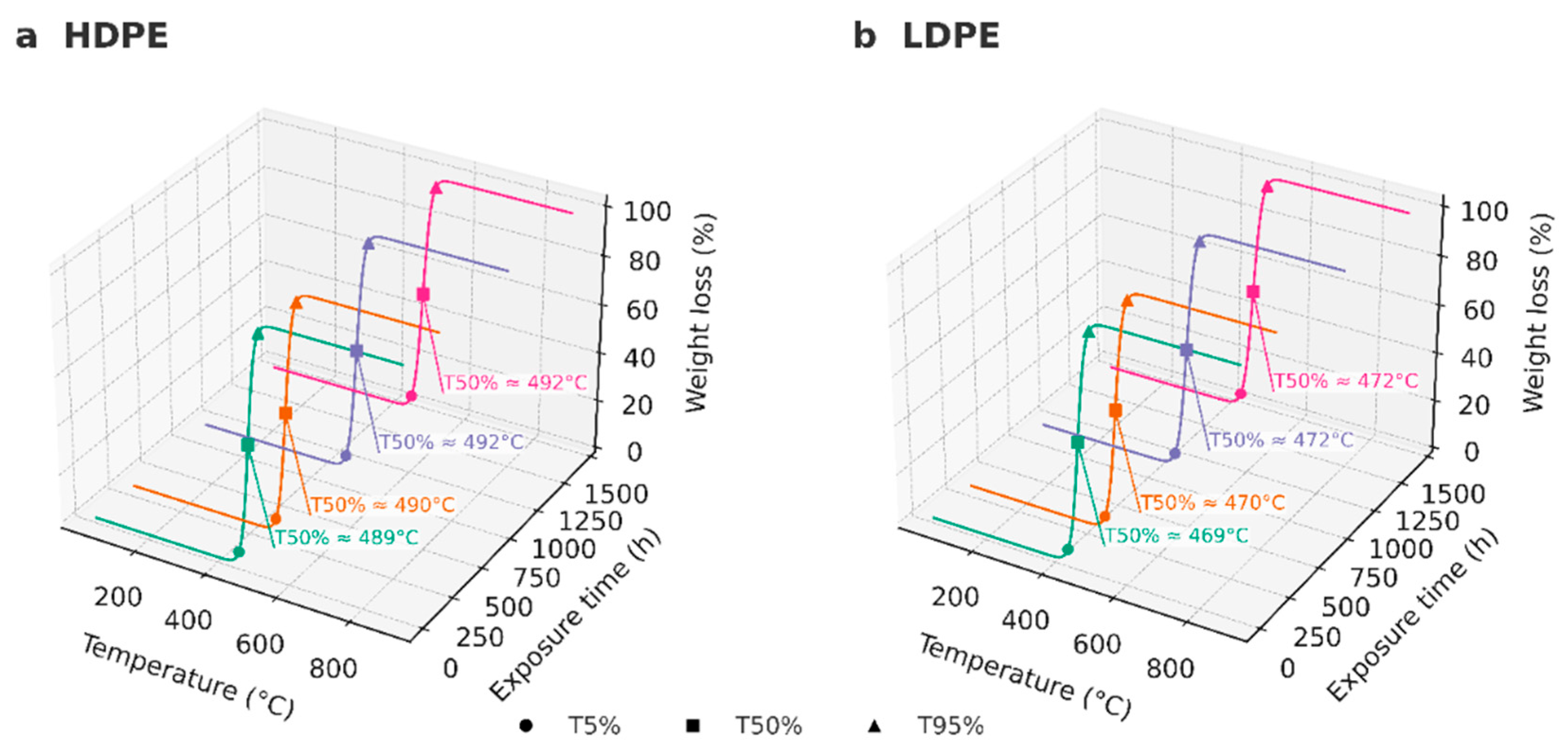

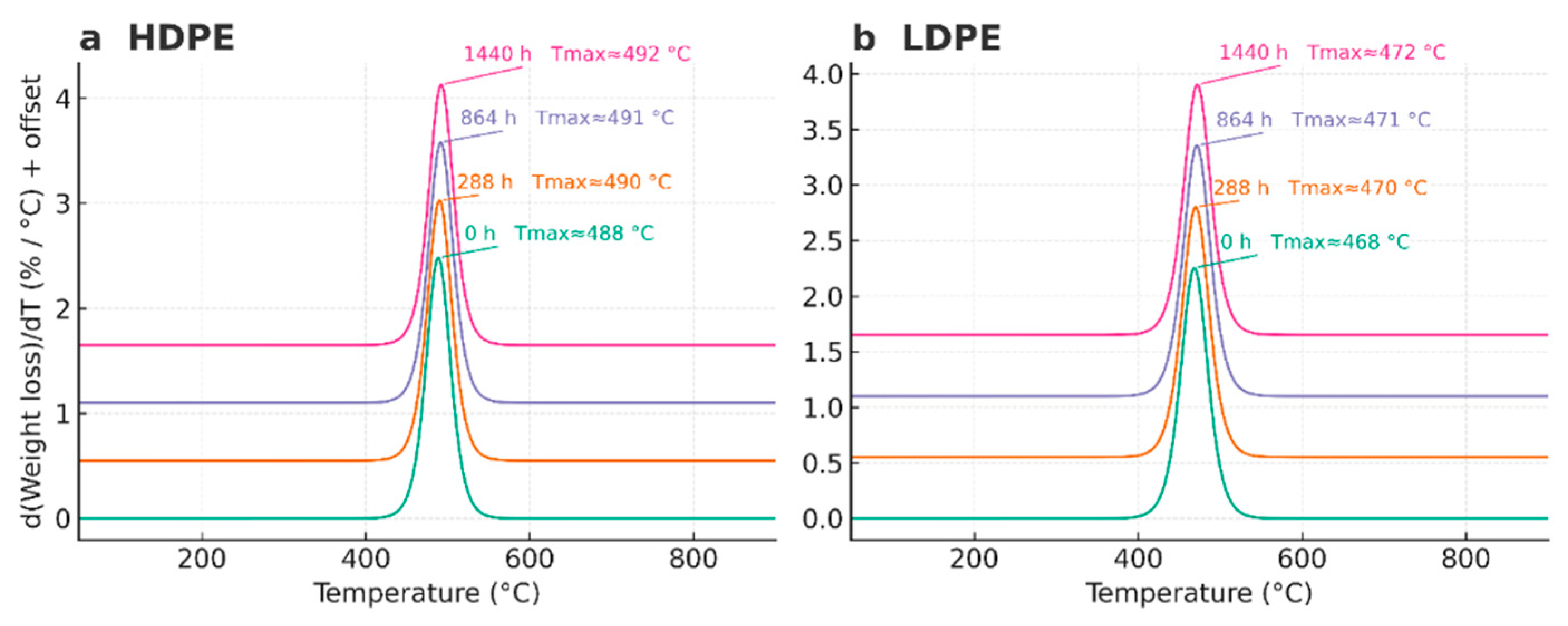

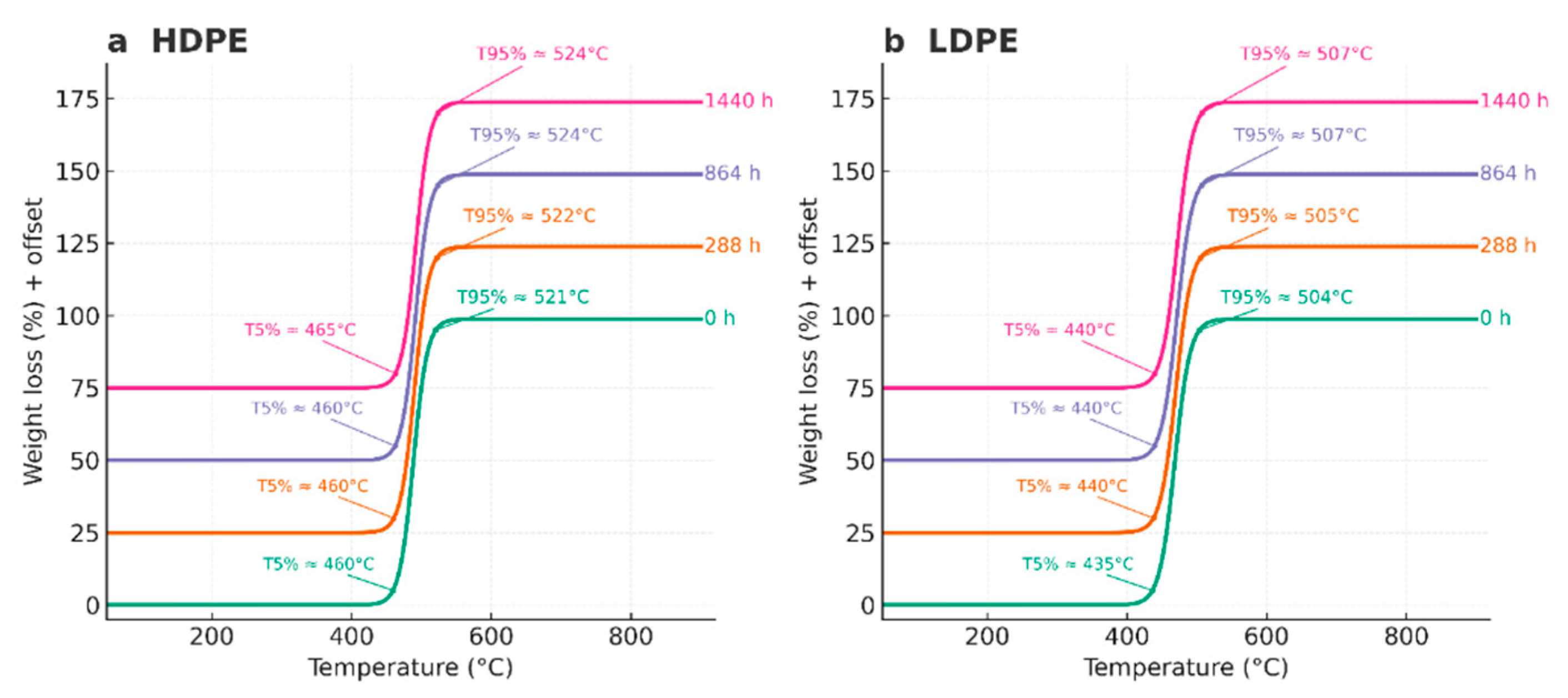

3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

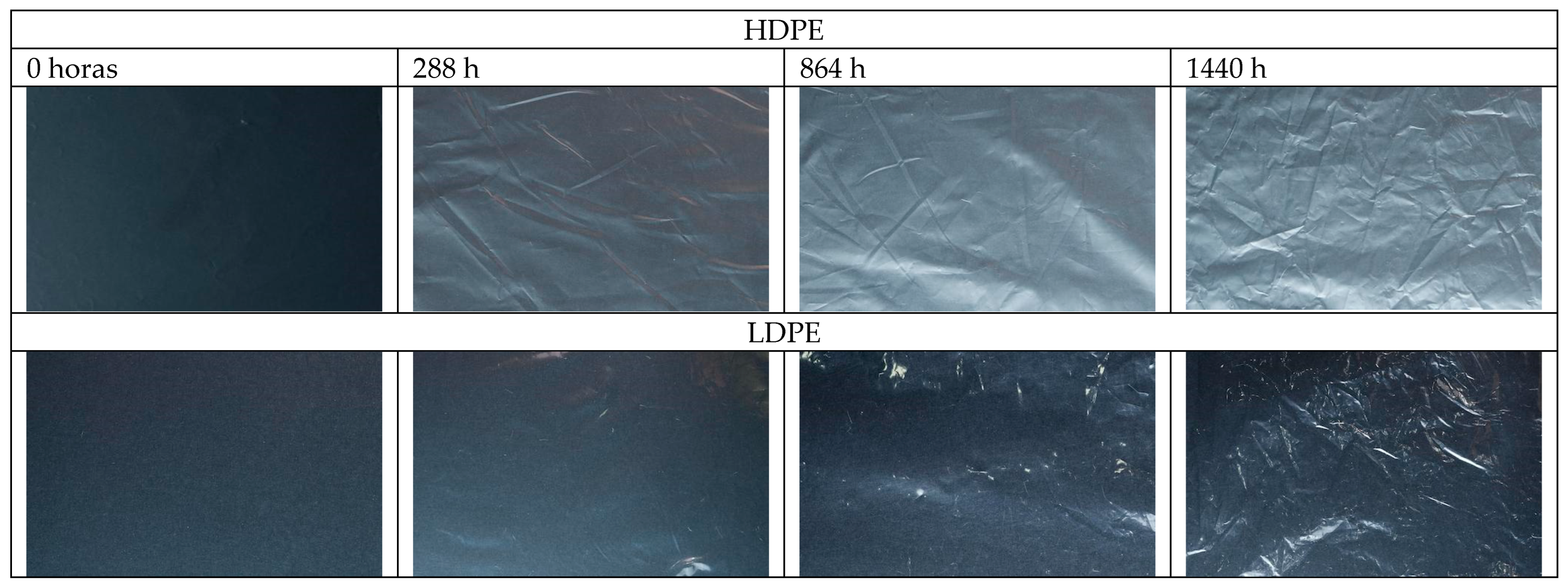

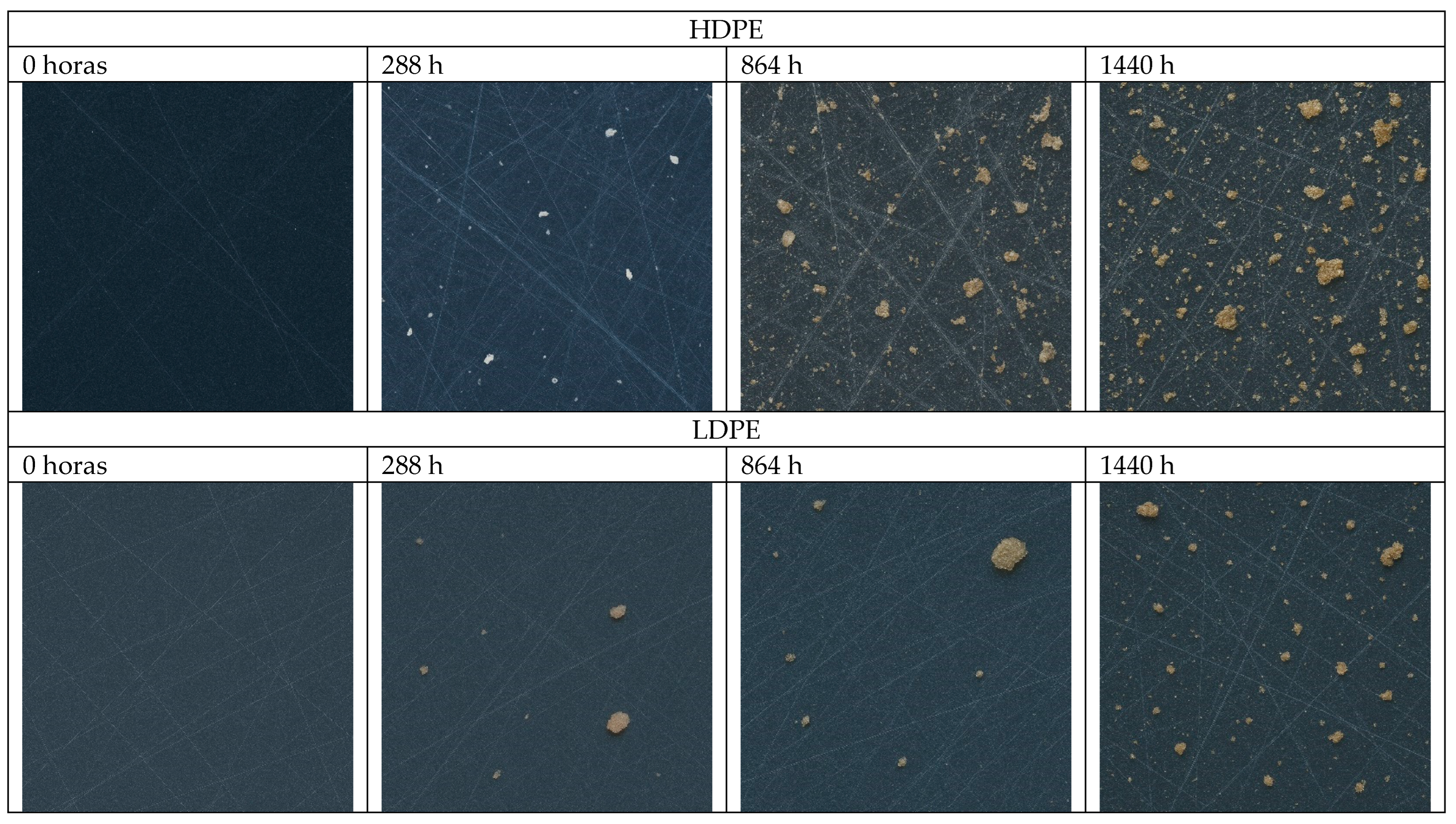

3.5. Macro- and Microphotography

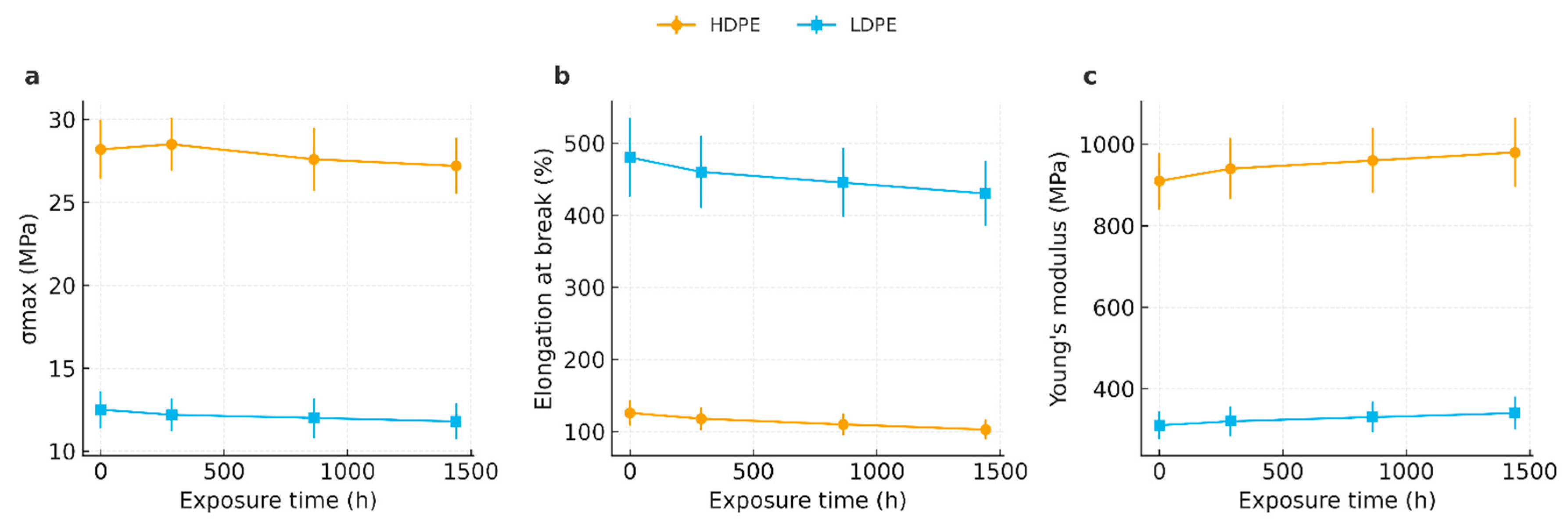

3.6. Tensile Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4.5. Macro- and Microphotography

4.6. Tensile Testing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lennert J, Kovács K, Koós B, Swain N, Bálint C, Hamza E, et al. Climate Change, Pressures, and Adaptation Capacities of Farmers: Empirical Evidence from Hungary. Horticulturae 2024;10:56. [CrossRef]

- Doyeni MO, Stulpinaite U, Baksinskaite A, Suproniene S, Tilvikiene V. The Effectiveness of Digestate Use for Fertilization in an Agricultural Cropping System. Plants 2021;10:1734. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Post-Harvest Alternatives in Banana Cultivation. Agronomy 2024;14:2109. [CrossRef]

- Kikulwe EM, Okurut S, Ajambo S, Nowakunda K, Stoian D, Naziri D. Postharvest Losses and their Determinants: A Challenge to Creating a Sustainable Cooking Banana Value Chain in Uganda. Sustainability 2018;10:2381. [CrossRef]

- Rodov V, Porat R, Sabag A, Kochanek B, Friedman H. Microperforated Compostable Packaging Extends Shelf Life of Ethylene-Treated Banana Fruit. Foods 2022;11:1086. [CrossRef]

- Shinga MH, Silue Y, Fawole O. Recent Advancements and Trends in Postharvest Application of Edible Coatings on Bananas: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2025;14.

- Ruiz Medina MD, Quimbita Yupangui Y, Artés-Hernández F, Ruales J. Combined Effect of Antifungal Coating and Polyethylene Packaging on the Quality of Banana During Storage. Agronomy 2025;15:2028. [CrossRef]

- Bordón P, Paz R, Peñalva C, Vega G, Monzón M, García L. Biodegradable Polymer Compounds Reinforced with Banana Fiber for the Production of Protective Bags for Banana Fruits in the Context of Circular Economy. Agronomy 2021;11:242. [CrossRef]

- Esguerra E, Del Carmen D, Reyes RD, Lualhati RA. Vacuum Packaging Controlled Crown Rot of Organically-Grown Balangon (Musa acuminata AAA Group) Banana. Horticulturae 2017;3:14. [CrossRef]

- Hu L, Li Y, Zhou K, Shi K, Niu Y, Qu F, et al. Postharvest Application of Myo-Inositol Extends the Shelf-Life of Banana Fruit by Delaying Ethylene Biosynthesis and Improving Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2025;14:2638. [CrossRef]

- Xiao L, Jiang X, Deng Y, Xu K, Duan X, Wan K, et al. Study on Characteristics and Lignification Mechanism of Postharvest Banana Fruit during Chilling Injury. Foods 2023;12:1097. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina M, Ávila J, Ruales J. DISEÑO DE UN RECUBRIMIENTO COMESTIBLE BIOACTIVO PARA APLICARLO EN LA FRUTILLA (Fragaria vesca) COMO PROCESO DE POSTCOSECHA. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología Postcosecha 2016;17:276–87.

- Guo J, Duan J, Yang Z, Karkee M. De-Handing Technologies for Banana Postharvest Operations—Updates and Challenges. Agriculture 2022;12:1821. [CrossRef]

- Gouda MHB, Duarte-Sierra A. An Overview of Low-Cost Approaches for the Postharvest Storage of Fruits and Vegetables for Smallholders, Retailers, and Consumers. Horticulturae 2024;10:803. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Song Y, Lai L, Fang D, Li W, Cao F, et al. Sustaining freshness: Critical review of physiological and biochemical transformations and storage techniques in postharvest bananas. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2024;46:101386. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Quimbita Yupangui Y, Ruales J. Effect of a Protein–Polysaccharide Coating on the Physicochemical Properties of Banana (Musa paradisiaca) During Storage. Coatings 2025;15:812. [CrossRef]

- Katsarov P, Shindova M, Lukova P, Belcheva A, Delattre C, Pilicheva B. Polysaccharide-Based Micro- and Nanosized Drug Delivery Systems for Potential Application in the Pediatric Dentistry. Polymers 2021;13:3342. [CrossRef]

- An W, Hu K, Wang T, Peng L, Li S, Hu X. Effects of Overlap Length on Flammability and Fire Hazard of Vertical Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) Plate Array. Polymers 2020;12:2826. [CrossRef]

- Lin C-L, Cheng T-L, Wu N-J. Micropatterned Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) Thin Films with Improved Color-Switching Rates and Coloration Efficiency. Polymers 2022;14:2951. [CrossRef]

- Arman Alim AA, Baharum A, Mohammad Shirajuddin SS, Anuar FH. Blending of Low-Density Polyethylene and Poly(Butylene Succinate) (LDPE/PBS) with Polyethylene–Graft–Maleic Anhydride (PE–g–MA) as a Compatibilizer on the Phase Morphology, Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Polymers 2023;15:261. [CrossRef]

- Tarani E, Pušnik Črešnar K, Zemljič LF, Chrissafis K, Papageorgiou GZ, Lambropoulou D, et al. Cold Crystallization Kinetics and Thermal Degradation of PLA Composites with Metal Oxide Nanofillers. Applied Sciences 2021;11:3004. [CrossRef]

- Rubiano-Navarrete AF, Rodríguez Sandoval P, Torres Pérez Y, Gómez-Pachón EY. Effect of Fiber Loading on Green Composites of Recycled HDPE Reinforced with Banana Short Fiber: Physical, Mechanical and Morphological Properties. Polymers 2024;16:3299. [CrossRef]

- Lynch JM, Corniuk RN, Brignac KC, Jung MR, Sellona K, Marchiani J, et al. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC): An important tool for polymer identification and characterization of plastic marine debris. Environmental Pollution 2024;346:123607. [CrossRef]

- Leyva C, Cruz-Alcantar P, Espinoza-Solis V, Martínez-Guerra E, Piñon-Balderrama C, Compean I, et al. Application of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC) in Food and Drug Industries. Polymers 2020;12:1:5.

- Heimowska, A. Environmental Degradation of Oxo-Biodegradable Polyethylene Bags. Water 2023;15:4059. [CrossRef]

- Campanale C, Savino I, Massarelli C, Uricchio VF. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to Assess the Degree of Alteration of Artificially Aged and Environmentally Weathered Microplastics. Polymers 2023;15:911. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk P, Kadac-Czapska K, Grembecka M. Polyethylene Packaging as a Source of Microplastics: Current Knowledge and Future Directions on Food Contamination. Foods 2025;14:2408. [CrossRef]

- Rampazzo F, Calace N, Formalewicz M, Noventa S, Gion C, Bongiorni L, et al. An FTIR and EA-IRMS Application to the Degradation Study of Compostable Plastic Bags in the Natural Marine Environment. Applied Sciences 2023;13:10851. [CrossRef]

- Henn AS, Frohlich AC, Pedrotti MF, Cauduro VH, Oliveira MLS, Flores EM de M, et al. Microwave-Assisted Solid Sampling Analysis Coupled to Flame Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry for Cd and Pb Determination in Food-Contact Polymers. Sustainability 2022;14:291. [CrossRef]

- Di Duca F, Montuori P, De Rosa E, De Simone B, Scippa S, Dadà G, et al. Advancing Analytical Techniques in PET and rPET: Development of an ICP–MS Method for the Analysis of Trace Metals and Rare Earth Elements. Foods 2024;13:2716. [CrossRef]

- Nhanga MC, Geraldo D, Nhapulo SL, João AF, Carneiro J, Costa MFM. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Content in Plastic Bags Used as Improvised Food Cooking Covers: A Case Study from the Mozambican Community. Sustainability 2025;17:964. [CrossRef]

- Shah YA, Bhatia S, Al-Harrasi A, Afzaal M, Saeed F, Anwer MK, et al. Mechanical Properties of Protein-Based Food Packaging Materials. Polymers 2023;15:1724. [CrossRef]

- Ballestar de las Heras R, Colom X, Cañavate J. Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Incorporating Post-Industrial Recycled LLDPE and Post-Consumer PE in Films: Macrostructural and Microstructural Perspectives in the Packaging Industry. Polymers 2024;16:916. [CrossRef]

- de Souza AMN, Avila LB, Contessa CR, Valério Filho A, de Rosa GS, Moraes CC. Biodegradation Study of Food Packaging Materials: Assessment of the Impact of the Use of Different Biopolymers and Soil Characteristics. Polymers 2024;16:2940. [CrossRef]

- Perera KY, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S. Biopolymer-Based Sustainable Food Packaging Materials: Challenges, Solutions, and Applications. Foods 2023;12:2422. [CrossRef]

- Fedotova O, Myalenko D, Pryanichnikova N, Yurova E, Agarkova E. Microscopic and Structural Studies of an Antimicrobial Polymer Film Modified with a Natural Filler Based on Triterpenoids. Polymers 2022;14:1097. [CrossRef]

- Breheny C, Colbert DM, Bezerra G, Geever J, Geever LM. Towards Sustainable Food Packaging: Mechanical Recycling Effects on Thermochromic Polymers Performance. Polymers 2025;17:1042. [CrossRef]

- Yetgin S, Ağırsaygın M, Yazgan İ. Smart Food Packaging Films Based on a Poly(lactic acid), Nanomaterials, and a pH Sensitive Dye. Processes 2025;13:1105. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Liao Y, Zhu G, Wang L, Chen Z, Li X, et al. Development of Double-Film Composite Food Packaging with UV Protection and Microbial Protection for Cherry Preservation. Foods 2025;14:2283. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Feng G, Lin N, Lan H, Li Q, Yao D, et al. A Review of Degradation and Life Prediction of Polyethylene. Applied Sciences 2023;13:3045. [CrossRef]

- Suraci SV, Fabiani D, Mazzocchetti L, Giorgini L. Degradation Assessment of Polyethylene-Based Material Through Electrical and Chemical-Physical Analyses. Energies 2020;13:650. [CrossRef]

- Frigione M, Rodríguez-Prieto A. Can Accelerated Aging Procedures Predict the Long Term Behavior of Polymers Exposed to Different Environments? Polymers 2021;13:2688. [CrossRef]

- Plota A, Masek A. Lifetime Prediction Methods for Degradable Polymeric Materials—A Short Review. Materials 2020;13:4507. [CrossRef]

- Picuno C, Godosi Z, Santagata G, Picuno P. Degradation of Low-Density Polyethylene Greenhouse Film Aged in Contact with Agrochemicals. Applied Sciences 2024;14:10809. [CrossRef]

- Biale G, La Nasa J, Mattonai M, Corti A, Vinciguerra V, Castelvetro V, et al. A Systematic Study on the Degradation Products Generated from Artificially Aged Microplastics. Polymers 2021;13:1997. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Chen J, Jia W, Huang K, Ma Y. Comparing the Aging Processes of PLA and PE: The Impact of UV Irradiation and Water. Processes 2024;12:635. [CrossRef]

- Müller M, Kolář V, Mishra RK. Mechanical and Thermal Degradation-Related Performance of Recycled LDPE from Post-Consumer Waste. Polymers 2024;16:2863. [CrossRef]

- Burelo M, Hernández-Varela JD, Medina DI, Treviño-Quintanilla CD. Recent developments in bio-based polyethylene: Degradation studies, waste management and recycling. Heliyon 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Ncube LK, Ude AU, Ogunmuyiwa EN, Zulkifli R, Beas IN. Environmental Impact of Food Packaging Materials: A Review of Contemporary Development from Conventional Plastics to Polylactic Acid Based Materials. Materials 2020;13:4994. [CrossRef]

- Yan H, Li W, Chen H, Liao Q, Xia M, Wu D, et al. Effects of Storage Temperature, Packaging Material and Wash Treatment on Quality and Shelf Life of Tartary Buckwheat Microgreens. Foods 2022;11:3630. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Skirtach AG. Nanoarchitectonics of Sustainable Food Packaging: Materials, Methods, and Environmental Factors. Materials 2025;18:1167. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Hao Y, Liu B, Chen Y, Li L. Development and Application of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Poly (Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate)/Thermoplastic Starch Film Containing Salicylic Acid for Banana Preservation. Foods 2023;12:3397. [CrossRef]

- Kossalbayev BD, Belkozhayev AM, Abaildayev A, Kadirshe DK, Tastambek KT, Kurmanbek A, et al. Biodegradable Packaging from Agricultural Wastes: A Comprehensive Review of Processing Techniques, Material Properties, and Future Prospects. Polymers 2025;17:2224. [CrossRef]

- Panou A, Lazaridis DG, Karabagias IK. Application of Smart Packaging on the Preservation of Different Types of Perishable Fruits. Foods 2025;14:1878. [CrossRef]

- Muthu A, Nguyen DHH, Neji C, Törős G, Ferroudj A, Atieh R, et al. Nanomaterials for Smart and Sustainable Food Packaging: Nano-Sensing Mechanisms, and Regulatory Perspectives. Foods 2025;14:2657. [CrossRef]

- Dash KK, Deka P, Bangar SP, Chaudhary V, Trif M, Rusu A. Applications of Inorganic Nanoparticles in Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2022;14:521. [CrossRef]

- Shankar VS, Thulasiram R, Priyankka AL, Nithyasree S, Sharma AA. Applications of Nanomaterials on a Food Packaging System—A Review. Engineering Proceedings 2024;61:4. [CrossRef]

- Kuan HTN, Tan MY, Hassan MZ, Zuhri MYM. Evaluation of Physico-Mechanical Properties on Oil Extracted Ground Coffee Waste Reinforced Polyethylene Composite. Polymers 2022;14:4678. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J, Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Essential Oils as an Antifungal Alternative for the Control of Various Species of Fungi Isolated from Musa paradisiaca: Part I. Microorganisms 2025;13:1827. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Essential Oils as an Antifungal Alternative to Control Several Species of Fungi Isolated from Musa paradisiaca: Part III. Microorganisms 2025;13:1663. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Essential Oils as an Antifungal Alternative to Control Several Species of Fungi Isolated from Musa paradisiaca: Part II. Microorganisms 2025;13:1663. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3418-21. Standard Test Method for Transition Temperatures and Enthalpies of Fusion and Crystallization of Polymers by Differential Scanning Calorimetry n.d. https://store.astm.org/d3418-21.html (accessed September 1, 2025).

- Suárez F, Conchillo JJ, Gálvez JC, Casati MJ. Macro Photography as an Alternative to the Stereoscopic Microscope in the Standard Test Method for Microscopical Characterisation of the Air-Void System in Hardened Concrete: Equipment and Methodology. Materials 2018;11:1515. [CrossRef]

- de las Heras RB, Ayala SF, Salazar EM, Carrillo F, Cañavate J, Colom X. Circular Economy Insights on the Suitability of New Tri-Layer Compostable Packaging Films after Degradation in Storage Conditions. Polymers 2023;15:4154. [CrossRef]

| Code | Polyethylene type | Exposure time (h) | Condition / Series |

| T01 | HDPE (high-density) | 0 | Initial control |

| T02 | HDPE (high-density) | 288 | ≈12 days |

| T03 | HDPE (high-density) | 864 | ≈36 days |

| T04 | HDPE (high-density) | 1440 | ≈60 days |

| T05 | LDPE (low-density) | 0 | Initial control |

| T06 | LDPE (low-density) | 288 | ≈12 days |

| T07 | LDPE (low-density) | 864 | ≈36 days |

| T08 | LDPE (low-density) | 1440 | ≈60 days |

| Polyethylene type | Exposure time (h) | Condition / Series | Tm (°C) | Tonset (°C) | ΔHf (J/g) | Xc (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | HDPE (high-density) | 0 | Initial control | 130.0 ± 1.5 | 128.0 ± 1.0 | 3.20 ± 0.50 | 1.09 ± 0.17 |

| T02 | HDPE (high-density) | 288 | ≈12 days | 129.8 ± 1.2 | 128.5 ± 1.1 | 3.05 ± 0.90 | 1.04 ± 0.31 |

| T03 | HDPE (high-density) | 864 | ≈36 days | 137.5 ± 2.5 | 136.9 ± 2.8 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.05 ± 0.03 |

| T04 | HDPE (high-density) | 1440 | ≈60 days | 132.7 ± 2.1 | 131.1 ± 2.6 | 1.40 ± 0.55 | 0.48 ± 0.19 |

| T05 | LDPE (low-density) | 0 | Initial control | 118.6 ± 2.1 | 116.9 ± 2.0 | 1.40 ± 0.80 | 0.48 ± 0.27 |

| T06 | LDPE (low-density) | 288 | ≈12 days | 123.7 ± 0.9 | 122.3 ± 1.0 | 1.55 ± 0.75 | 0.53 ± 0.25 |

| T07 | LDPE (low-density) | 864 | ≈36 days | 125.4 ± 1.6 | 123.6 ± 1.7 | 2.35 ± 0.95 | 0.80 ± 0.32 |

| T08 | LDPE (low-density) | 1440 | ≈60 days | 123.4 ± 0.8 | 122.0 ± 0.7 | 1.15 ± 0.65 | 0.39 ± 0.22 |

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Assignment | Observation across time |

|---|---|---|

| ~2918, ~2848 | ν_as/ν_s(CH₂) | Stable positions and relative intensities in all series. |

| ~1472, ~1463 | δ(CH₂) (scissoring) | Stable; used as internal reference for qualitative indices. |

| ~730, ~720 | ρ_r(CH₂) (orthorhombic) | Doublet preserved; no systematic loss—consistent with modest crystallinity changes. |

| 1700–1740 | C=O (carbonyl) | Not detected; Carbonyl Index effectively ~0 within noise. |

| 910–990 | =CH₂ / vinyl | Not evident; no unsaturation growth. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).