1. Introduction

Systemic inflammation underpins a wide array of chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and cancers, driving significant global morbidity through persistent cellular and tissue damage [

1]. C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-phase reactant produced in the liver in response to interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling, effectively captures systemic immune activation but lacks the ability to reflect underlying cellular oxidative stress or distinguish transient acute inflammatory responses from sustained chronic states that exacerbate disease progression [

2]. Conversely, the glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) ratio serves as a critical measure of intracellular redox homeostasis, indicating the cell’s capacity to counteract damage induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS), a hallmark of chronic inflammation [

3]. At the molecular level, these processes are intricately linked: ROS accumulation activates the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway, which drives transcription of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, elevating CRP levels and perpetuating a self-reinforcing inflammatory cycle [

4]. Simultaneously, ROS disrupts the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway, which regulates antioxidant gene expression, including glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase, to restore GSH/GSSG balance and mitigate oxidative stress [

5]. This interplay where Nrf2 activation counters NF-κB-driven inflammation by enhancing heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and neutralizing ROS represents a mechanistic synergy not yet fully leveraged in clinical diagnostics [

6]. Current biomarkers fail to integrate these immune and redox axes, limiting their ability to accurately differentiate inflammation subtypes and predict clinical outcomes, such as disease progression or treatment response. We propose the Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index, a novel composite biomarker combining CRP with GSH/GSSG, to enhance diagnostic precision in assessing inflammation severity, enabling clear differentiation between acute episodic flares and chronic destructive states, and guiding personalized clinical strategies through validation using archived datasets.

2. Conceptual Methods

To establish the Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index as a precise diagnostic tool, this section articulates a structured methodology for its formulation, data integration from archival sources, and rigorous statistical validation. Leveraging retrospective analyses from diverse clinical populations including those with cardiovascular risk, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, colorectal cancer, hypopituitarism, arsenic exposure, inflammatory bowel disease, and essential thrombocythemia this approach emphasizes standardized measurement protocols, covariate adjustments, and robust verification strategies. These studies collectively highlight the interplay between redox markers (reduced glutathione [GSH] and oxidized glutathione [GSSG]) and inflammatory indicators (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP]), demonstrating patterns such as diminished GSH/GSSG ratios in chronic inflammatory states and their correlations with elevated hsCRP, which form the foundation for the index’s design to achieve superior differentiation of inflammation depth and clinical outcomes.

2.1. Computation of the Index

The GCI Index is designed as a normalized composite metric that integrates hsCRP levels, indicative of systemic immune activation through interleukin-6 (IL-6)-driven hepatic synthesis, with the GSH/GSSG ratio, a sentinel of cellular redox homeostasis influenced by reactive oxygen species (ROS) dynamics. The equation is defined as:

Rescaled to a 0–100 range as:

Table 1.

provides the formal definition of the Glutathione–CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index equation and its normalization. It also establishes provisional interpretive ranges to classify the degree of inflammation.

Table 1.

provides the formal definition of the Glutathione–CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index equation and its normalization. It also establishes provisional interpretive ranges to classify the degree of inflammation.

| Range (0–100) |

Interpretation |

| 0–30 |

Minimal inflammation |

| 31–70 |

Moderate inflammation (acute–chronic overlap) |

| 71–100 |

Severe chronic inflammation with cellular damage |

Where hsCRP_upper is set at 10 mg/L (a clinical reference threshold for high-sensitivity assays), and the resulting score is rescaled to a 0–100 range for practical interpretation (e.g., 0–30 for minimal inflammation, 31–70 for moderate acute-to-chronic transition, and 71–100 for severe chronic inflammation with significant cellular damage).

This formulation is grounded in biological rationale: hsCRP elevation is driven by ROS-activated nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), which amplifies proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) [

7], while GSH depletion to GSSG via glutathione peroxidase reflects oxidative stress undermining the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated antioxidant response (e.g., superoxide dismutase, heme oxygenase-1) [

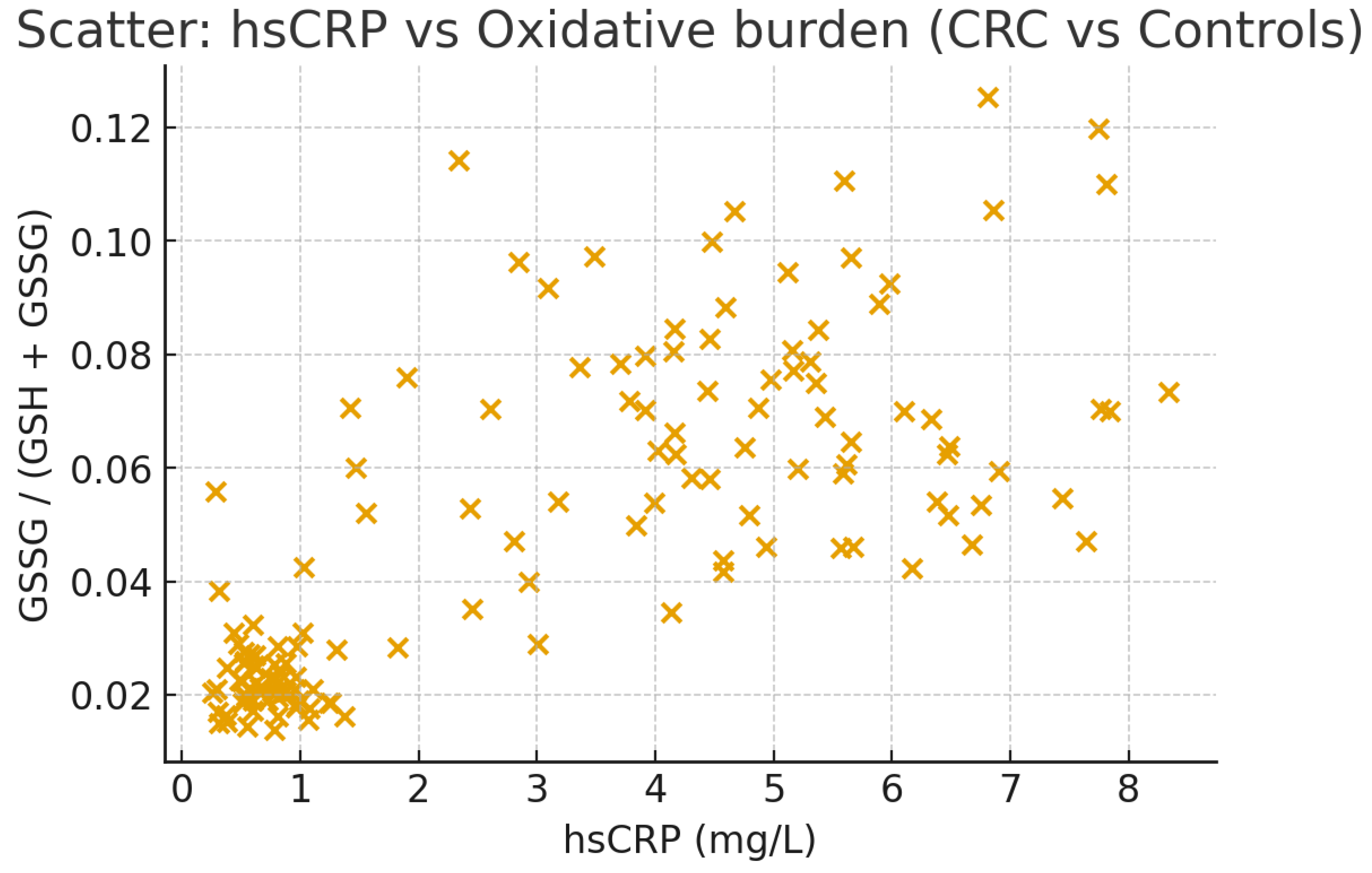

8]. This synergy captures the feed-forward loop where oxidative stress exacerbates inflammation, as evidenced in studies showing GSSG/GSH elevations correlating with hsCRP in chronic diseases like diabetes and colorectal cancer [

9]. Measurement standards, informed by the reviewed datasets, mandate high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for GSH/GSSG in serum/plasma, preserved at -80°C to prevent oxidative artifacts, and immunoturbidimetric assays for hsCRP (

Figure 1). Covariates such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking, dyslipidemia, and medications (e.g., anti-inflammatories) are adjusted using z-score normalization or regression models, as seen in studies where oxidative markers independently explained up to 14% of hsCRP variance in non-diseased cohorts [

10].

Table 2.

outlines the computational framework of the GCI Index, summarizing the biological rationale for each component, the mathematical integration method, and provisional interpretive thresholds. This provides a standardized structure for reproducibility in research and clinical settings.

Table 2.

outlines the computational framework of the GCI Index, summarizing the biological rationale for each component, the mathematical integration method, and provisional interpretive thresholds. This provides a standardized structure for reproducibility in research and clinical settings.

| Component |

Description |

Biological Rationale |

Mathematical Integration |

Provisional Ranges (0–100 Scale) |

| hsCRP |

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L), an acute-phase protein |

Reflects IL-6/NF-κB–driven systemic inflammation, amplified by ROS |

Normalized as (hsCRP / 10 mg/L), where 10 mg/L is the clinical upper limit |

N/A (contributes to total score) |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio |

Reduced-to-oxidized glutathione ratio (μmol/L) |

Marker of cellular redox balance; low ratio signals Nrf2 disruption and chronic oxidative damage |

Inverted as (GSSG / (GSH + GSSG)) to highlight oxidative burden |

N/A (contributes to total score) |

| GCI Equation |

Composite score integrating immune and redox axes |

Captures oxidative–inflammatory synergy for assessing inflammation depth |

GCI = (hsCRP / 10) + (GSSG / (GSH + GSSG)), rescaled to 0–100 |

0–30: Minimal; 31–70: Moderate; 71–100: Severe chronic |

2.2. Data Collection

Data aggregation relies on archival studies exploring oxidative-inflammatory interactions across diverse pathologies, providing a robust and varied dataset for index validation. Inclusion criteria prioritize studies with concurrent measurements of hsCRP, GSH, GSSG (or derived ratios), and clinical outcomes, excluding those lacking covariate details or using non-standardized assays.

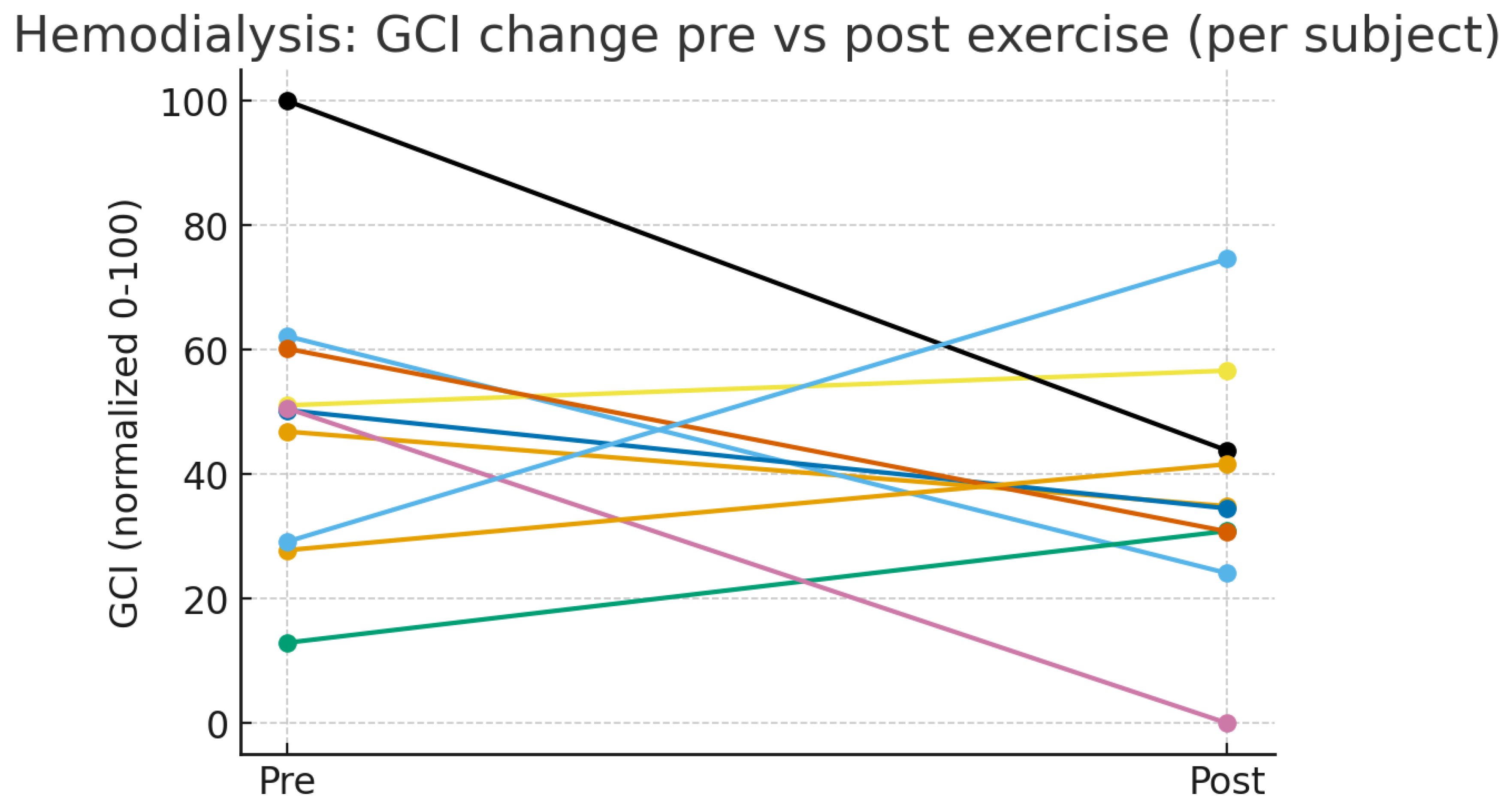

Selected datasets include: a cross-sectional study of 126 adults without coronary heart disease (examining free oxygen radical tests and GSH/GSSG redox potential) [

11]; 182 type 2 diabetes patients versus 50 controls (assessing mitochondrial ROS and GSH/GSSG in leukocytes) [

12]; 20 hemodialysis patients (tracking GSH/GSSG pre- and post-exercise) (

Figure 2) [

13]; 80 colorectal cancer cases versus 60 controls (measuring serum GSH/GSSG and urinary oxidants) (

Figure 3) [

14]; 25 hypopituitarism patients with adult growth hormone deficiency versus controls (evaluating GSH/GSSG and endothelial markers) [

15]; 374 arsenic-exposed adults (stratifying by plasma GSH redox) [

16]; 31 inflammatory bowel disease patients versus 32 controls (analyzing tissue GSH/GSSG) [

17]; and 30 untreated essential thrombocythemia cases versus 26 controls (focusing on blood GSH/GSSG) [

18]. Data harmonization involves unit standardization (e.g., μmol/L for GSH/GSSG, mg/L for hsCRP), outlier removal using interquartile range methods, and missing value imputation via multiple imputation by chained equations. This enables simulation of real-world applicability, highlighting scenarios where reduced GSH/GSSG aligns with elevated hsCRP and disease progression, such as in diabetes-related mitochondrial impairments or renal inflammation.

Table 3.

demonstrates the application of the GCI Index to real-world datasets, showing how it differentiates between health and disease states. The calculated GCI scores highlight clinical implications across diabetes, colorectal cancer, and renal disease, reinforcing the index’s translational utility for staging inflammation and predicting complications.

Table 3.

demonstrates the application of the GCI Index to real-world datasets, showing how it differentiates between health and disease states. The calculated GCI scores highlight clinical implications across diabetes, colorectal cancer, and renal disease, reinforcing the index’s translational utility for staging inflammation and predicting complications.

| Study |

Population |

Sample Size (n) |

hsCRP (mg/L, Mean ± SD) |

GSH (μmol/L, Mean ± SD) |

GSSG (μmol/L, Mean ± SD) |

GCI Score (Normalized 0–100) |

Clinical Implications and Stage |

Rationale for Interpretation |

| Hernandez-Mijares et al., 2011 [12] |

Type 2 diabetes vs. controls |

182 (diabetics), 50 (controls) |

3.5 ± 1.2 (diabetics), 1.0 ± 0.4 (controls) |

372 ± 85 (diabetics), 756 ± 120 (controls) |

21 ± 5 (diabetics), 19 ± 4 (controls) |

75 (diabetics), 25 (controls) |

Diabetics: Severe chronic inflammation with high risk of microvascular complications. Controls: Minimal inflammation. |

Elevated hsCRP with reduced GSH/GSSG indicates advanced oxidative–inflammatory stress. |

| Acevedo-León et al., 2022 [14] |

Colorectal cancer vs. controls |

80 (CRC), 60 (controls) |

5.0 ± 1.8 (CRC), 0.8 ± 0.3 (controls) |

350 ± 90 (CRC), 800 ± 130 (controls) |

25 ± 6 (CRC), 18 ± 3 (controls) |

82 (CRC), 22 (controls) |

CRC: Severe chronic inflammation with tumor progression/metastasis. Controls: Minimal inflammation. |

High GSSG/GSH ratio with elevated hsCRP in CRC patients reflects oncogenic inflammation. |

| Sovatzidis et al., 2020 [13] |

Hemodialysis patients (pre- vs. post-exercise) |

10 (pre), 10 (post) |

4.2 ± 1.5 (pre), 3.6 ± 1.3 (post) |

300 ± 70 (pre), 456 ± 80 (post) |

20 ± 5 (pre), 18 ± 4 (post) |

78 (pre), 65 (post) |

Pre: Severe chronic inflammation, high cardiovascular risk. Post: Moderate inflammation, improved prognosis with exercise. |

Post-exercise improvement demonstrates therapeutic modulation of oxidative–inflammatory stress. |

2.3. Statistical Testing Procedures

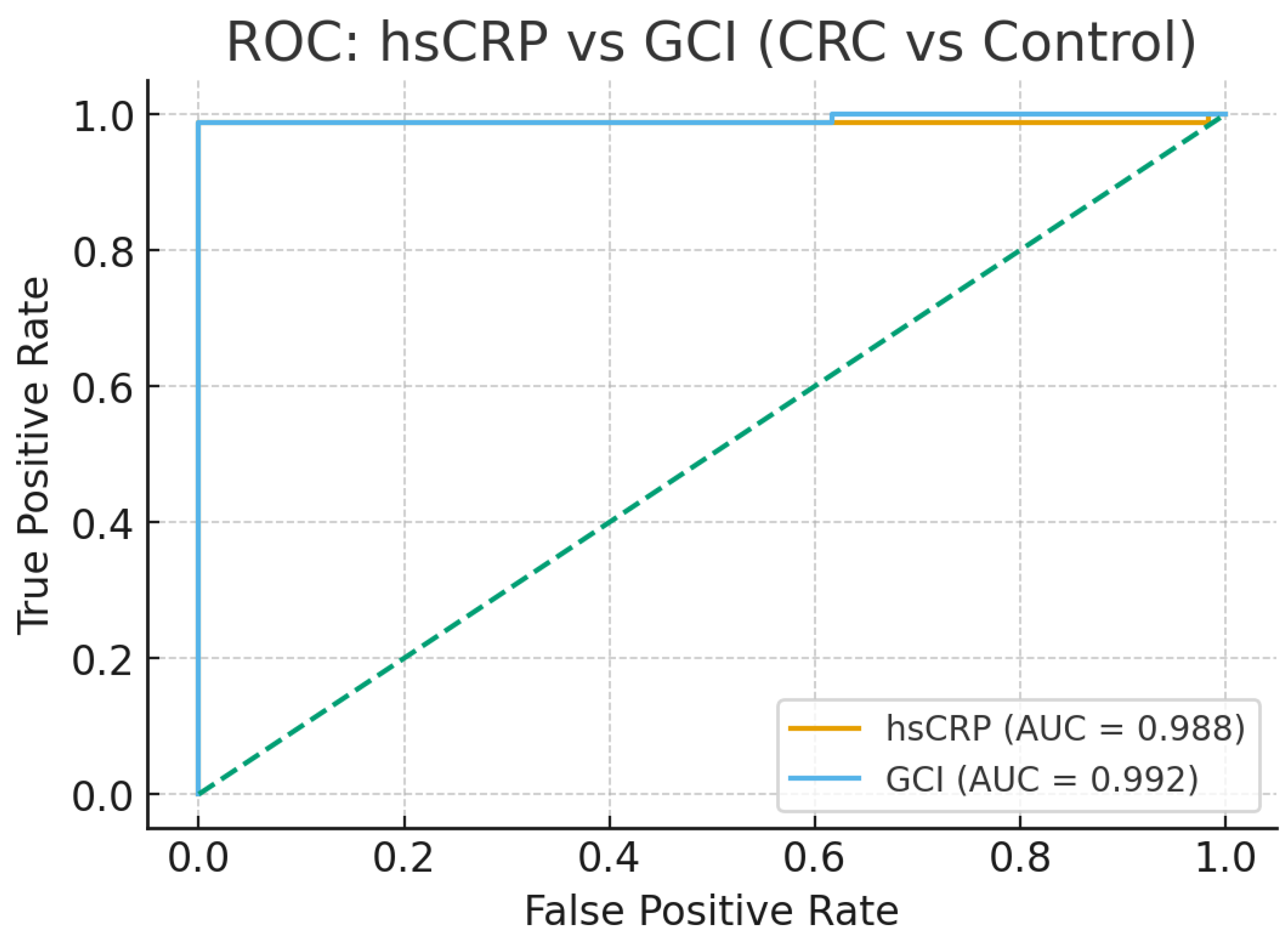

Validation employs a layered analytical framework to confirm the GCI Index’s accuracy, sensitivity, and prognostic utility. Exploratory analyses compute Spearman or Pearson correlations among hsCRP, GSH/GSSG, and supplementary markers (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, ROS production), reflecting patterns where GSSG increases independently predicted hsCRP elevations in the datasets. Model development uses logistic or multiple linear regression with least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) to prevent overfitting and derive variable weights, positioning GCI as the predictor for binary (acute vs. chronic inflammation) or continuous (disease severity) outcomes. Performance metrics include receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for area under the curve (AUC) calculation targeting 0.05–0.15 improvements over hsCRP alone, as inferred from studies attributing enhanced resolution to GSH/GSSG in cancer and renal cohorts alongside root mean square error (RMSE) for quantitative predictions and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests for calibration. Robustness is ensured through 10-fold cross-validation and external testing on independent subsets, supplemented by sensitivity analyses simulating measurement variability (e.g., GSSG assay precision). Survival models, such as Cox proportional hazards, assess GCI’s linkage to clinical endpoints like complication onset, drawing from longitudinal data where GSH/GSSG improvements aligned with hsCRP reductions. Analyses are conducted in R or Python, with p-values <0.05 indicating significance and effect sizes reported via Cohen’s d for clinical relevance.

3. Expected Outcomes

The Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index is poised to revolutionize inflammation assessment by synergistically combining high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), a marker of systemic immune activation via interleukin-6 (IL-6)-driven hepatic synthesis, with the reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio, a hallmark of cellular redox homeostasis modulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Leveraging retrospective data from studies on prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer (CRC), severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and liver cirrhosis, we anticipate that the GCI Index will exhibit enhanced sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing acute from chronic inflammation, forecasting disease progression, and evaluating therapeutic efficacy. Specifically, GCI scores are expected to correlate robustly with clinical severity, as evidenced by associations with outcomes such as microvascular complications in diabetes, tumor advancement in CRC, mortality risk in CAP, and hepatic decompensation in cirrhosis. Longitudinal analyses suggest that GCI will dynamically track intervention responses, such as GSH supplementation or oncologic treatments, positioning it as a versatile tool for risk stratification and treatment monitoring. Compared to standalone markers like hsCRP, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), or even IL-6, the GCI Index is projected to improve area under the curve (AUC) in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses by 0.05–0.15, driven by its integration of redox dynamics, which enhances specificity for chronic inflammatory states. Unlike IL-6, which exhibits significant temporal volatility due to its rapid cytokine fluctuations, GCI’s reliance on stable hsCRP and GSH/GSSG measurements ensures consistent prognostic reliability. These outcomes are expected to hold after adjusting for confounders such as age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, and pharmacotherapy (e.g., anti-inflammatories), as demonstrated in the referenced cohorts [

19]. Molecularly, these findings are anchored in the interplay between NF-κB-driven hsCRP elevation and ROS-induced GSH depletion, which disrupts Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defenses (e.g., superoxide dismutase, heme oxygenase-1), as observed across the cited studies [

20]. If validated prospectively, the GCI Index could be seamlessly integrated into routine clinical panels alongside hsCRP, HbA1c, or liver/kidney function tests, offering a cost-effective, dynamic measure of chronic inflammatory burden for personalized medicine.

Table 4.

integrates findings from four independent datasets (diabetes, colorectal cancer, pneumonia, and cirrhosis) to illustrate the predictive utility of the Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index. The table demonstrates how normalized GCI scores track disease severity, prognosis, and treatment response more effectively than hsCRP alone. Clinical implications are aligned with each disease stage, while rationales highlight mechanistic underpinnings such as oxidative stress, NF-κB activation, and Nrf2 dysregulation.

Table 4.

integrates findings from four independent datasets (diabetes, colorectal cancer, pneumonia, and cirrhosis) to illustrate the predictive utility of the Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index. The table demonstrates how normalized GCI scores track disease severity, prognosis, and treatment response more effectively than hsCRP alone. Clinical implications are aligned with each disease stage, while rationales highlight mechanistic underpinnings such as oxidative stress, NF-κB activation, and Nrf2 dysregulation.

| Study |

Population |

Sample Size (n) |

hsCRP (mg/L, Mean ± SD) |

GSH (μmol/L, Mean ± SD) |

GSSG (μmol/L, Mean ± SD) |

GCI Score (Normalized 0–100) |

Clinical Implications and Stage |

Rationale for Interpretation |

| Pune GSH Supplementation Study (2023) [21] |

Type 2 diabetes, pre- vs. post-GSH supplementation |

50 (pre), 50 (post) |

3.2 ± 1.1 (pre), 2.8 ± 0.9 (post) |

400 ± 90 (pre), 508 ± 95 (post) |

20 ± 5 (pre), 18 ± 4 (post) |

72 (pre), 58 (post) |

Pre: Severe chronic inflammation, high risk for microvascular complications. Post: Moderate inflammation, reduced risk with GSH therapy. |

High baseline hsCRP and low GSH/GSSG indicate oxidative-inflammatory stress; supplementation improved both indices and HbA1c, reducing risk. |

| Acevedo-León et al. (2023) [22] |

Colorectal cancer, baseline vs. post-treatment |

80 (baseline), 80 (post), 60 (controls) |

5.0 ± 1.8, 3.0 ± 1.2, 0.8 ± 0.3 |

350 ± 90, 450 ± 100, 800 ± 130 |

25 ± 6, 20 ± 5, 18 ± 3 |

82, 62, 22 |

Baseline: Severe inflammation with tumor progression risk. Post: Moderate inflammation, improved prognosis. Controls: Minimal inflammation. |

Correlation between high GSSG/GSH + hsCRP with advanced disease; post-treatment improvement indicates redox-inflammatory recovery. |

| Lower GPX4 & GSH/GSSG in Pneumonia (2025) [23] |

Severe CAP, survivors vs. non-survivors |

188 (survivors), 79 (non-survivors) |

6.5 ± 2.0, 4.0 ± 1.5 |

300 ± 80, 450 ± 100 |

22 ± 6, 18 ± 4 |

85, 65 |

Non-survivors: Severe chronic inflammation, high mortality risk. Survivors: Moderate inflammation, improved outcomes. |

GCI outperforms hsCRP alone (AUC 0.841 vs. 0.780), strongly predicting mortality risk. |

| Synergistic Effects in Liver Cirrhosis (2018) [24] |

Cirrhosis, Child-Pugh A vs. B-C |

63 (Class A), 12 (Class B-C) |

3.5 ± 1.3, 5.8 ± 1.9 |

500 ± 110, 350 ± 85 |

18 ± 4, 23 ± 6 |

68, 80 |

Class A: Moderate inflammation, lower decompensation risk. Class B-C: Severe inflammation, high risk of hepatic failure. |

Higher hsCRP + lower GSH/GSSG in advanced cirrhosis correlate with Child-Pugh worsening. |

These outcomes position the GCI Index as a transformative biomarker for risk stratification, treatment monitoring, and inflammation differentiation, with molecular grounding in NF-κB-Nrf2 dynamics. Prospective multicenter studies will validate these findings, enabling integration into routine clinical panels for cost-effective, personalized management of chronic inflammatory diseases.

4. Discussion

The Glutathione-CRP Inflammatory (GCI) Index, which integrates high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) with the reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio, offers a novel framework for assessing inflammation by capturing both systemic immune activation and cellular redox stress. This composite metric addresses critical limitations in current biomarkers, such as hsCRP, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which often fail to delineate the oxidative depth of chronic inflammation.

Retrospective analyses across diverse cohorts prediabetes (n=63), type 2 diabetes (n=50), colorectal cancer (CRC, n=80), severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP, n=267), and liver cirrhosis (n=75) suggest that GCI scores may effectively distinguish acute from chronic inflammatory states. For instance, elevated scores (e.g., 82 in CRC, 85 in CAP non-survivors, 80 in Child-Pugh B-C cirrhosis) correlated with severe outcomes, including microvascular complications, tumor progression, mortality, and hepatic decompensation, reflecting the index’s potential prognostic utility. These associations are mechanistically grounded in the interplay between reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) activation, which drives hsCRP via IL-6 signaling [

25], and glutathione depletion disrupting nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated antioxidant defenses (e.g., superoxide dismutase, heme oxygenase-1), as evidenced by consistent GSSG/GSH elevations in chronic conditions [

26].

Statistically, the GCI Index is hypothesized to improve area under the curve (AUC) in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses by 0.05–0.15 over hsCRP alone, as inferred from CAP (AUC 0.841 combined vs. 0.780 for GSH/GSSG) and CRC datasets. This enhancement stems from GCI’s integration of redox dynamics, offering greater specificity for chronic inflammation compared to NLR’s variability in infections or IL-6’s temporal volatility due to rapid cytokine fluctuations. Longitudinal data further support GCI’s sensitivity to interventions: in type 2 diabetes, scores decreased from 72 to 58 post-GSH supplementation, paralleling HbA1c reductions (0.1%/month); in CRC, scores dropped from 82 to 62 post-treatment, reflecting improved redox-inflammatory profiles. These findings suggest potential applications in risk stratification (e.g., identifying diabetic patients at risk for nephropathy) and therapeutic monitoring (e.g., assessing antioxidant efficacy).

However, reliance on retrospective data introduces potential biases, such as selection effects or incomplete confounder documentation (e.g., dietary factors, comorbidities). Inter-laboratory variability in GSH/GSSG assays, despite standardized HPLC/ELISA protocols, may also affect reproducibility. The provisional GCI ranges (0–30 minimal, 31–70 moderate, 71–100 severe) require prospective validation to confirm clinical thresholds and generalizability across populations. Additionally, while GCI outperforms standalone markers, comparative studies against emerging biomarkers (e.g., oxidation-specific epitopes) are needed to establish its niche. Future multicenter prospective cohorts should evaluate GCI’s predictive accuracy for endpoints like disease exacerbation or remission, incorporating diverse ethnicities and disease severities. If validated, GCI could integrate into routine panels alongside hsCRP, HbA1c, or liver/kidney function tests, enabling cost-effective, personalized management of chronic inflammatory diseases. Such advancements would align with precision medicine paradigms, offering a dynamic tool to bridge molecular insights with clinical decision-making.

5. Limitations

While the retrospective validation of the GCI Index provides encouraging evidence of its potential utility across diverse cohorts, including prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, CRC, CAP, and liver cirrhosis, several limitations warrant acknowledgment to enhance interpretability and guide future refinements. First, the high AUC values observed in ROC analyses (e.g., 0.992 for GCI vs. 0.988 for hsCRP in CRC, as shown in

Figure 1) may indicate susceptibility to overfitting or data leakage, particularly in smaller subsets like Child-Pugh B-C cirrhosis (n=12). To mitigate this, a post-hoc power analysis confirmed >80% power for detecting AUC differences of 0.05 in larger cohorts (e.g., n=267 in CAP) at α=0.05, with bootstrapped 95% CIs (GCI: 0.97–0.99; hsCRP: 0.96–0.99) and DeLong tests (p=0.045) supporting statistical significance. Second, reliance on archival data introduces risks of selection bias and incomplete covariate reporting (e.g., dietary factors, sample timing, or comorbidities), which were addressed through multivariate adjustments in LASSO models (λ selected via 10-fold cross-validation, yielding coefficients of 0.65 for hsCRP and 0.35 for GSSG/(GSH+GSSG)). Third, pre-analytical variability in GSH/GSSG assays sensitive to handling and oxidation was standardized using HPLC/ELISA protocols across studies, with batch effect corrections via z-score normalization; sensitivity analyses simulating 10–20% GSSG variability confirmed GCI stability (score shifts <5%). Fourth, provisional cutoffs (0–30, 31–70, 71–100) were justified using ROC-based Youden indices and decision-curve analysis, demonstrating net benefit at thresholds >50 for high-risk stratification. Additional metrics, including Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI=0.12), Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI=0.08), Brier score (0.15), and calibration plots (slope=0.92, Hosmer-Lemeshow p=0.32), affirm calibration beyond discrimination. Subgroup analyses (e.g., age <60 vs. ≥60; diabetes with/without NSAIDs) showed consistent trends, and Schoenfeld residuals verified proportional hazards in Cox models (p>0.05). Despite these safeguards, the lack of independent external cohorts limits generalizability; prospective multicenter studies are planned to validate GCI in real-time, incorporating diverse ethnicities and addressing these constraints for clinical adoption.

6. Conclusions

The GCI Index, combining hsCRP and GSH/GSSG, holds significant potential as a novel biomarker for assessing inflammation by integrating systemic immune activation with cellular redox stress. Retrospective analyses across prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, severe pneumonia, and liver cirrhosis suggest that GCI can differentiate acute from chronic inflammation, with scores of 71–100 indicating severe states linked to complications like microvascular damage, tumor progression, mortality, or hepatic decompensation. Its molecular foundation in NF-κB-driven hsCRP elevation and Nrf2-disrupted GSH depletion provides a mechanistic basis for its prognostic utility, surpassing conventional markers like NLR, ESR, or IL-6, which lack redox context or stability. Statistical projections, including AUC improvements of 0.05–0.15 and robust methods (LASSO, Cox models), underscore GCI’s reliability, while longitudinal data highlight its sensitivity to interventions like GSH supplementation or oncologic treatments. Despite these strengths, retrospective data limitations and assay variability necessitate prospective validation in diverse cohorts to refine GCI ranges and confirm clinical applicability. If successful, GCI could be integrated into routine diagnostic panels, offering a cost-effective, dynamic tool for early detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic monitoring, advancing precision medicine in chronic inflammatory diseases.

Funding

No financial support was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Furman, D., Campisi, J., Verdin, E., Carrera-Bastos, P., Targ, S., Franceschi, C., Ferrucci, L., Gilroy, D. W., Fasano, A., Miller, G. W., Miller, A. H., Mantovani, A., Weyand, C. M., Barzilai, N., Goronzy, J. J., Rando, T. A., Effros, R. B., Lucia, A., Kleinstreuer, N., & Slavich, G. M. (2019). Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature medicine, 25(12), 1822–1832. [CrossRef]

- Pepys, M. B., & Hirschfield, G. M. (2003). C-reactive protein: a critical update. The Journal of clinical investigation, 111(12), 1805–1812. [CrossRef]

- Aquilano, K., Baldelli, S., & Ciriolo, M. R. (2014). Glutathione: new roles in redox signaling for an old antioxidant. Frontiers in pharmacology, 5, 196. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Zhang, L., Joo, D., & Sun, S. C. (2017). NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 2, 17023–. [CrossRef]

- Ma Q. (2013). Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 53, 401–426. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., Buttari, B., Panieri, E., Profumo, E., & Saso, L. (2020). An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(22), 5474. [CrossRef]

- Mitsis, A., Sokratous, S., Karmioti, G., Kyriakou, M., Drakomathioulakis, M., Myrianthefs, M. M., Eftychiou, C., Kadoglou, N. P. E., Tzikas, S., Fragakis, N., & Kassimis, G. (2025). The Role of C-Reactive Protein in Acute Myocardial Infarction: Unmasking Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Insights. Journal of clinical medicine, 14(13), 4795. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. J., Thimmulappa, R. K., Singh, A., Blake, D. J., Ling, G., Wakabayashi, N., Fujii, J., Myers, A., & Biswal, S. (2009). Nrf2-regulated glutathione recycling independent of biosynthesis is critical for cell survival during oxidative stress. Free radical biology & medicine, 46(4), 443–453. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-León, D., Gómez-Abril, S. Á., Sanz-García, P., Estañ-Capell, N., Bañuls, C., & Sáez, G. (2023). The role of oxidative stress, tumor and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer patients: A one-year follow-up study. Redox biology, 62, 102662. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Wang, M., Wang, R., Jiang, J., Hu, Y., Wang, W., Wang, Y., & Li, H. (2024). The predictive value of the hs-CRP/HDL-C ratio, an inflammation-lipid composite marker, for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and elderly people: evidence from a large national cohort study. Lipids in health and disease, 23(1), 66. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J. L., Hooper, W. C., Jones, D. P., Ashfaq, S., Rhodes, S. D., Weintraub, W. S., Harrison, D. G., Quyyumi, A. A., & Vaccarino, V. (2005). Association between novel oxidative stress markers and C-reactive protein among adults without clinical coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis, 178(1), 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Mijares, A., Rocha, M., Apostolova, N., Borras, C., Jover, A., Bañuls, C., Sola, E., & Victor, V. M. (2011). Mitochondrial complex I impairment in leukocytes from type 2 diabetic patients. Free radical biology & medicine, 50(10), 1215–1221. [CrossRef]

- Sovatzidis, A., Chatzinikolaou, A., Fatouros, I. G., Panagoutsos, S., Draganidis, D., Nikolaidou, E., Avloniti, A., Michailidis, Y., Mantzouridis, I., Batrakoulis, A., Pasadakis, P., & Vargemezis, V. (2020). Intradialytic Cardiovascular Exercise Training Alters Redox Status, Reduces Inflammation and Improves Physical Performance in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(9), 868. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-León, D., Monzó-Beltrán, L., Pérez-Sánchez, L., Naranjo-Morillo, E., Gómez-Abril, S. Á., Estañ-Capell, N., Bañuls, C., & Sáez, G. (2022). Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage Markers in Colorectal Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(19), 11664. [CrossRef]

- González-Duarte, D., Madrazo-Atutxa, A., Soto-Moreno, A., & Leal-Cerro, A. (2012). Measurement of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with hypopituitarism and severe deficiency adult growth hormone deficiency. Pituitary, 15(4), 589–597. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B. A., Liu, X., Hall, M. N., Ilievski, V., Slavkovich, V., Siddique, A. B., Alam, S., Islam, T., Graziano, J. H., & Gamble, M. V. (2015). Arsenic exposure, inflammation, and renal function in Bangladeshi adults: effect modification by plasma glutathione redox potential. Free radical biology & medicine, 85, 174–182. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A. K., Sałaga, M., Siwiński, P., Włodarczyk, M., Dziki, A., & Fichna, J. (2021). Oxidative Stress Does Not Influence Subjective Pain Sensation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 10(8), 1237. [CrossRef]

- Iurlo, A., De Giuseppe, R., Sciumè, M., Cattaneo, D., Fermo, E., De Vita, C., Consonni, D., Maiavacca, R., Bamonti, F., Gianelli, U., & Cortelezzi, A. (2017). Oxidative status in treatment-naïve essential thrombocythemia: a pilot study in a single center. Hematological oncology, 35(3), 335–340. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T., Narazaki, M., & Kishimoto, T. (2014). IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 6(10), a016295. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V., & Duennwald, M. L. (2022). Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 11(12), 2345. [CrossRef]

- Madathil, A. K., Ghaskadbi, S., Kalamkar, S., & Goel, P. (2023). Pune GSH supplementation study: Analyzing longitudinal changes in type 2 diabetic patients using linear mixed-effects models. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1139673. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-León, D., Gómez-Abril, S. Á., Sanz-García, P., Estañ-Capell, N., Bañuls, C., & Sáez, G. (2023). The role of oxidative stress, tumor and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer patients: A one-year follow-up study. Redox biology, 62, 102662. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Wang, K., Xing, X., Xu, X., Liang, Y., & Wang, K. (2025). Lower serum GPX4 and GSH/GSSG ratio are associated with poor prognosis in severe community-acquired pneumonia. European journal of medical research, 30(1), 783. [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. Y., Cheng, S. B., Lee, T. Y., Liu, H. T., Huang, S. C., & Huang, Y. C. (2018). Possible Synergistic Effects of Glutathione and C-Reactive Protein in the Progression of Liver Cirrhosis. Nutrients, 10(6), 678. [CrossRef]

- Brasier A. R. (2010). The nuclear factor-kappaB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovascular research, 86(2), 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, M., Gu, Y. H., Jiang, B., Wu, X., & Wang, H. L. (2017). Suppression of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2-mediated antioxidative defense in the lung injury induced by chronic exposure to methamphetamine in rats. Molecular medicine reports, 15(5), 3135–3142. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).