1. Introduction

The presence of heavy metals in natural waters and soils, resulting from industrial discharges, poses a significant environmental concern. The battery industry is a significant contributor to this phenomenon, given that the effluents from battery manufacturing and recycling facilities commonly contain substantial quantities of these metals. The cathode materials of lithium-ion batteries employed in the automotive sector (e.g., NMC, NCA, and LMO chemistries) incorporate varying ratios of nickel, manganese, and cobalt [

1]. While elevated concentrations of heavy metals exert acute toxic effects on living organisms, even trace levels are hazardous due to their capacity for bioaccumulation and subsequent transfer through the food chain [

2].

A variety of technologies have been employed for the removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewater, including ion exchange, reverse osmosis, electrodialysis, and ultrafiltration [

3]. Despite their efficacy, these methodologies are often accompanied by substantial limitations, including incomplete metal removal, the formation of sludge, elevated reagent and energy utilisation, aggregation of metal precipitates, and membrane fouling. Consequently, there has been an increased focus on alternative treatment strategies, with bioremediation emerging as a highly promising option [

4]. The increasing interest in bioremediation can be attributed to its potential advantages in terms of cost-efficiency, effectiveness, and environmental sustainability [

5]. This approach employs biological systems to reduce pollutant concentrations and toxicity to acceptable levels. The microorganisms, encompassing bacteria, algae, and yeasts, function as the predominant agents in these processes. This is attributable to their ability to adsorb toxic metal ions onto their cell surfaces and accumulating them in substantial amounts within their intracellular spaces [

6,

7]. In this group, the freshwater microalga

Chlorella vulgaris has exhibited remarkable potential for the removal of heavy metals [

8].

The cell wall of

Chlorella vulgaris is primarily composed of complex carbohydrates, consisting of a cellulose fibre framework cross-linked with polysaccharides such as hemicellulose and glycoproteins [

9]. In addition, it contains various monosaccharides, including glucose, mannose, galactose, xylose, fucose, and arabinose, together with lipids and substantial amounts of glucosamines. Functional groups present within these biopolymers play a critical role in metal ion adsorption. Specifically, the algal cell wall incorporates carboxyl (-COOH), hydroxyl (-OH), amino (-NH₂), carbonyl (-C=O), ester (-CO–O–), sulfhydryl (-SH), sulphate (-SO₄²⁻), and phosphate (-PO₄³⁻) groups. Above pH 3, deprotonation of carboxyl, phosphate, and hydroxyl groups imparts a net negative surface charge, which facilitates electrostatic interactions with positively charged heavy metal cations [

11]. Since functional group protonation is pH-dependent, the surface charge of the cell wall varies with pH [

10]. Heavy metal binding to the algal surface biopolymers can proceed through multiple mechanisms, including physisorption, ion exchange, chelation, and complexation [

12].

While the removal of heavy metal ions from industrial wastewater is critical, the subsequent recovery of algal biomass that has accumulated these metals must also be addressed. Conventional harvesting methods include sedimentation, flotation, coagulation–flocculation, filtration, and repeated sedimentation steps [

13]. Among emerging alternatives, magnetic separation offers distinct advantages owing to its rapid operation, cost-effectiveness, and low energy requirements. Algal cells exhibit a strong affinity for magnetisable nanoparticles (MNPs), which readily adsorb onto their cell wall surfaces, thereby allowing efficient recovery under the influence of an external magnetic field [

14,

15,

16]. Compared with conventional sedimentation, which generally requires more than two hours for effective coagulation and settling, magnetic separation achieves comparable efficiencies within approximately 60 seconds [

17].

Maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃) nanoparticles possess stable and strongly magnetic properties, allowing for their rapid and efficient separation from solutions using an external magnetic field [

18]. Their excellent adsorption capacity is due to their high specific surface area and porosity, making them effective at binding cell walls of microalgae [

19]. Compared to other nanoparticles, they are less toxic, making them suitable for both environmental and biomedical applications [

20]. Their surfaces can be easily functionalized, enhancing their selectivity and broadening their range of uses. These characteristics make maghemite nanoparticles a promising alternative, particularly in fields like wastewater treatment [

21].

The aim of this study is to assess the capacity of Chlorella vulgaris cells to adsorb cobalt ions, which are common contaminants found in effluents from battery manufacturing processes. Furthermore, this study investigates the capacity of cobalt-adsorbed algal cells to take up maghemite nanoparticles onto their cell walls and to facilitate sedimentation within a magnetic field. This approach could enable the development of an innovative and environmentally friendly method for the removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewater in a more cost-effective manner, thereby complementing conventional wastewater treatment technologies. The interactions between microalgal cells and magnetic nanoparticles were analysed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with particular attention to identifying the functional groups involved by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements. The particle size and morphology of the magnetic nanoparticles were characterized by HRTEM.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Maghemite Nanoflowers

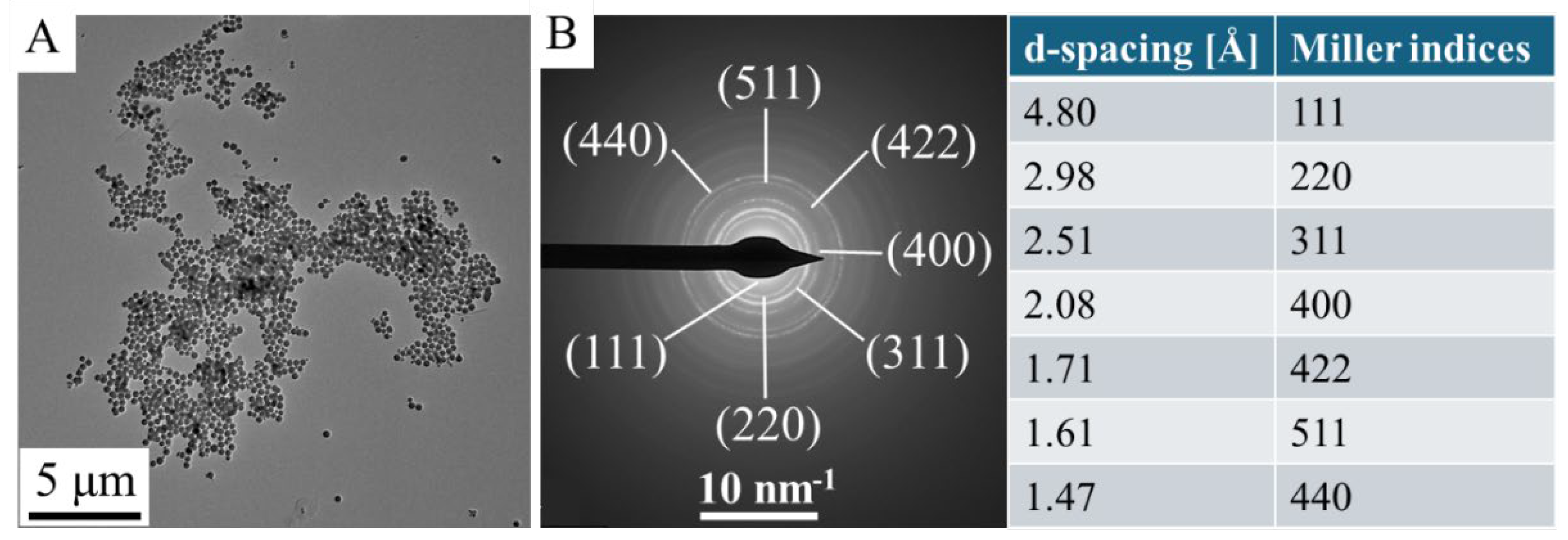

HRTEM measurements were carried out for study of particle size and morphology. In the TEM picture are showed the spherical morphology of the maghemite nanoflowers, at a higher resolution, you can see the characteristic fine structure that gives the name nanoflower (

Figure 1A,B). The average size these maghemite nanoflowers is 226 ± 66 nm but, this is only characteristic of the secondary structure, in fact these aggregate structures are composed of smaller crystallites (

Figure 1C).

The special structure is of great importance, given that the self-assembly of numerous crystallites has resulted in the creation of micropores. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was also performed on the maghemite sample (

Figure 1D). The EDS are found iron and oxygen, those chemical elements that make up maghemite (γ-Fe

2O

3) or magnetite (Fe

3O

4). In addition to the elements oxygen and iron, carbon has also been identified, which is partly due to organic molecules which are adsorbed by the maghemite nanoflowers. The detected presence of copper and carbon is attributable to the composition of the sample holder (copper grid with lacey carbon). The positions of the maghemite elements are clearly visible on the elemental maps (

Figure 1E). It was observed that only the maghemite nanoflowers exhibited detectable traces of iron and oxygen, indicating that iron is not present in its elemental state but occurs in the sample as iron oxide, specifically maghemite. Carbon can also be detected in the micropores of the maghemite nanoparticles and on its surface, due to the adsorbed organic molecules (ethylene glycol and monoethanolamine). During of the transmission electron microscopic examination, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) measurement was applied to study of the crystalline phase in the nanoflowers, (

Figure 2A,B). Based on the SAED results, the d-spacing values were calculated, which corresponds to the values given by the X-ray databases for maghemite (PDF 39-1346).

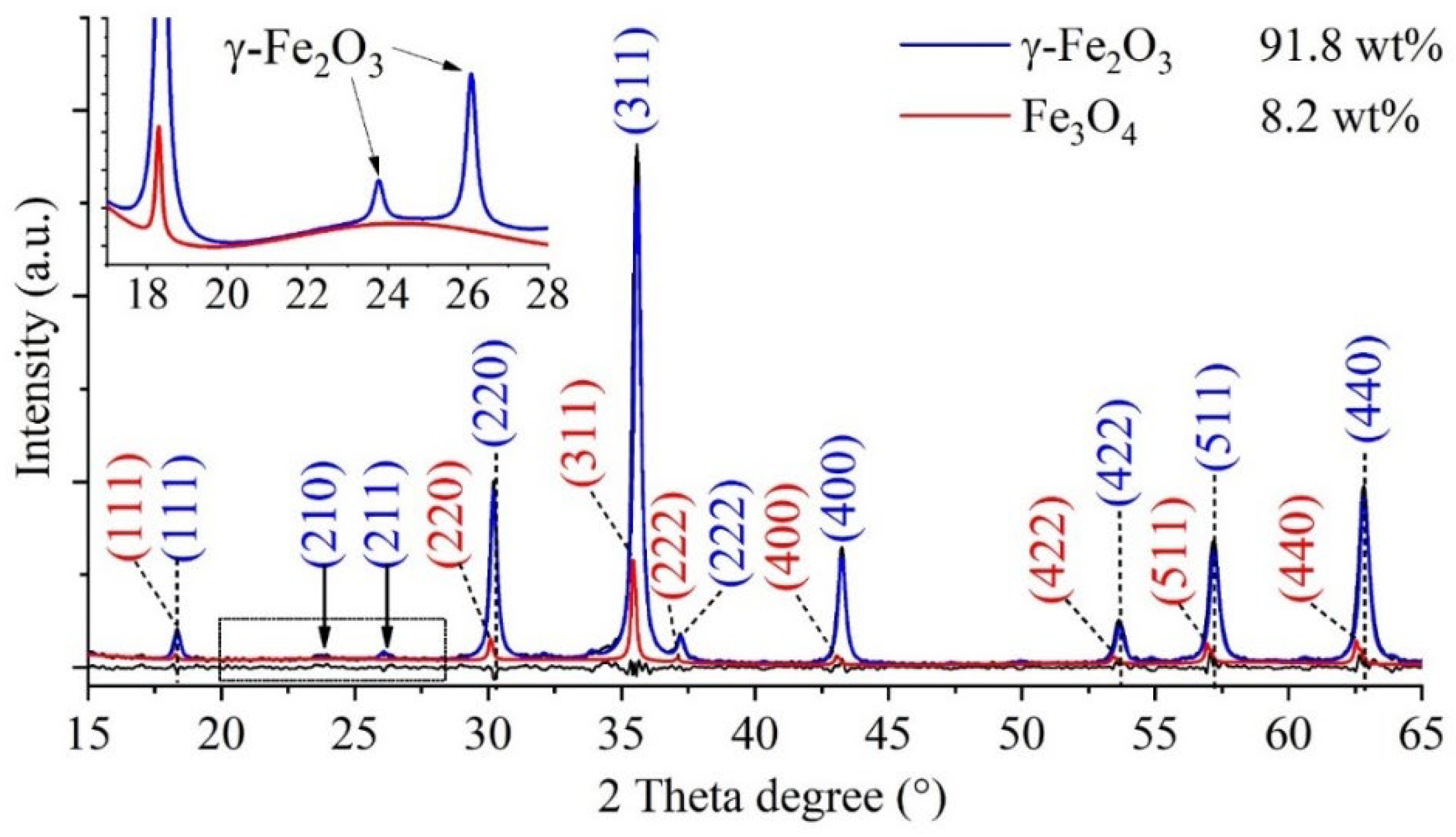

After confirming that the nanoflowers seen in the TEM images were indeed composed of maghemite crystallites, it was necessary to perform powder diffraction (XRD) measurements to rule out the presence of nonmagnetic contaminants. Reflections characteristic of the maghemite and magnetite phases were found on the XRD diffractogram. The Miller indices associated with the reflections were naturally the same as those marked on the SAED image. The XRD pattern of the sample (

Figure 3) shows those reflexions, which are characteristic on the maghemite (γ-Fe

2O

3), these are located at 18.3° (111), 23.8° (210), 26.1° (211), 30.2° (220), 35.6° (311), 37.2 (222), 43.3° (400), 53.7° (422), 57.2° (511) and 62.8° (440) two theta degrees, in agreement with the PDF 39–1346 card. In addition to the 91.8 wt% maghemite, another magnetic iron oxide, namely magnetite (Fe

3O

4), is present in the sample in the amount of 8.2 wt%. The reflections characteristic of magnetite at 18.2° (111), 30.1° (220), 35.4° (311), 37.1 (222), 43.1° (400), 53.4° (422), 56.9° (511) and 62.6° (440) can be found in the diffractogram (PDF 19–0629). Other iron oxide phase (hematite) or other salts (e. g. sodium chloride) as residue were not detected, in this sense that the synthesis method is efficiently usable to the preparation of maghemite nanoflowers.

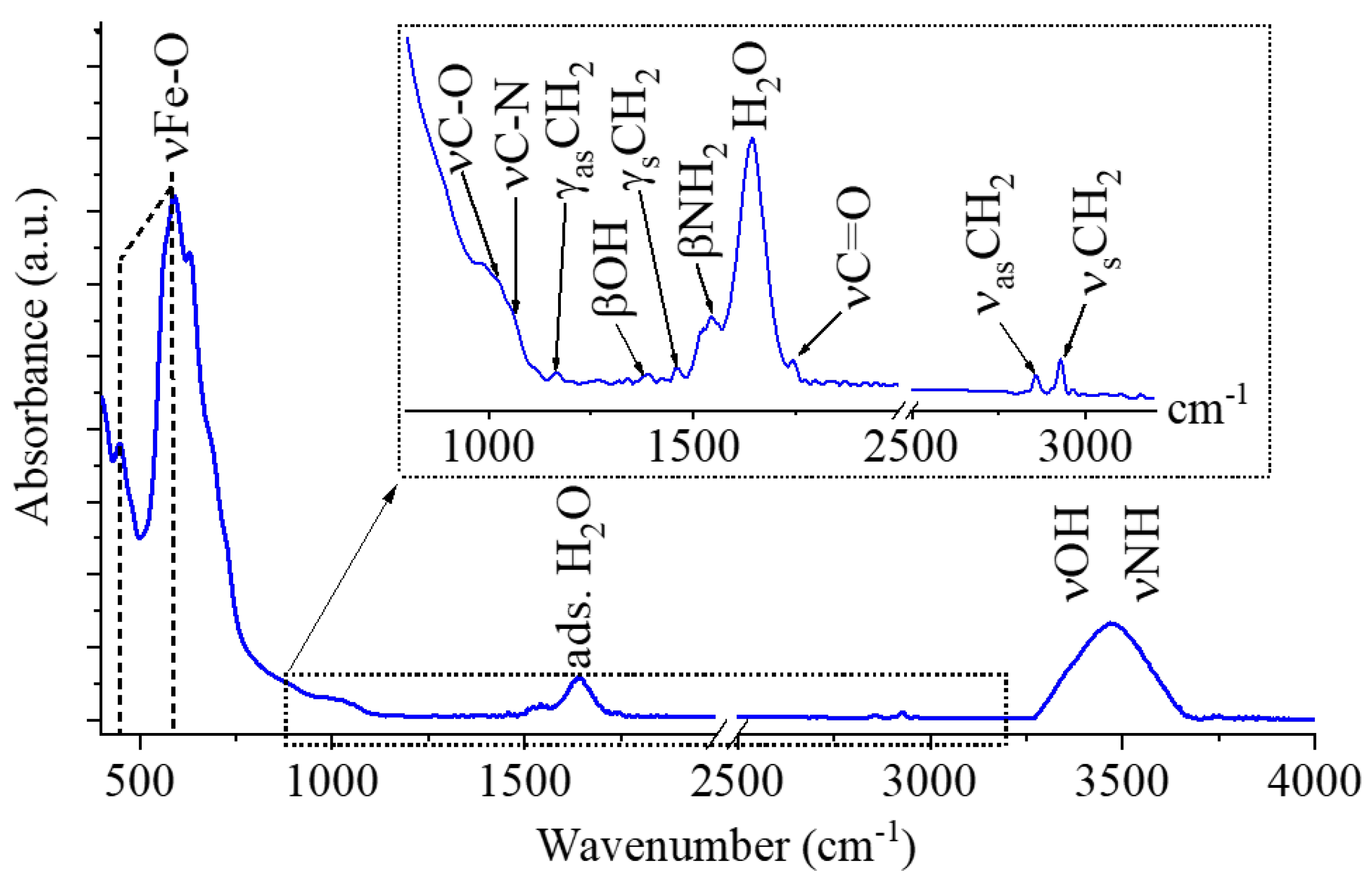

The presence of -NH

2, -OH and -COOH functional groups on the surface of maghemite particles is key important, because these groups contribute to the adsorption processes between the magnetic nanoparticles and algae cells, thus FTIR measurement was carried out (

Figure 4). Two characteristic bands were identified on the FTIR spectrum of maghemite at 52 cm

-1 and 587 cm

-1 wavenumbers, which were assigned to intrinsic stretching vibration modes of the metal-oxygen bonds (νM-O) at the octahedral and tetrahedral sites [

24]. The peaks at 1017 cm

−1 and 1068 cm

−1 belongs to the νC-O and νC-N vibration in the adsorbed monoethanolamine [

25,

26]. Other absorption band was identified at 1163 cm

-1 which can belong to the -CH

2 out of plane deformation (twisting) mode, its asymmetric deformation vibrational counterpart (γ

sCH

2) shows band at 1458 cm

-1. Visible other band at 1391 cm

-1 which can belong to the OH bending vibrations in the adsorbed ethylene glycol molecules. The band βNH

2 vibration mode was found at 1547 cm

-1 wavenumber, it corresponds to the free amine functional groups in MEA [

27]. Strazisar et al. demonstrated that, the bending vibrational mode of the amine groups (between 1580 cm

−1 and 1630 cm

−1) has been shown to interfere with the bending vibration mode of the adsorbed water molecules at 1641 cm

−1 and causes spectral distortion [

28,

29]. The symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibration of the aliphatic C-H bonds resulted peaks at 2857 cm

-1 and 2930 cm

-1, which can be explained by the adsorbed organic molecules of the ethylene glycol and monoethanolamine on the maghemite nanoflowers [

30,

31]. The stretching vibration bands of the hydroxyl and amine groups are overlapping and result in a broad region between 3000 cm

-1 and 3750 cm

-1.

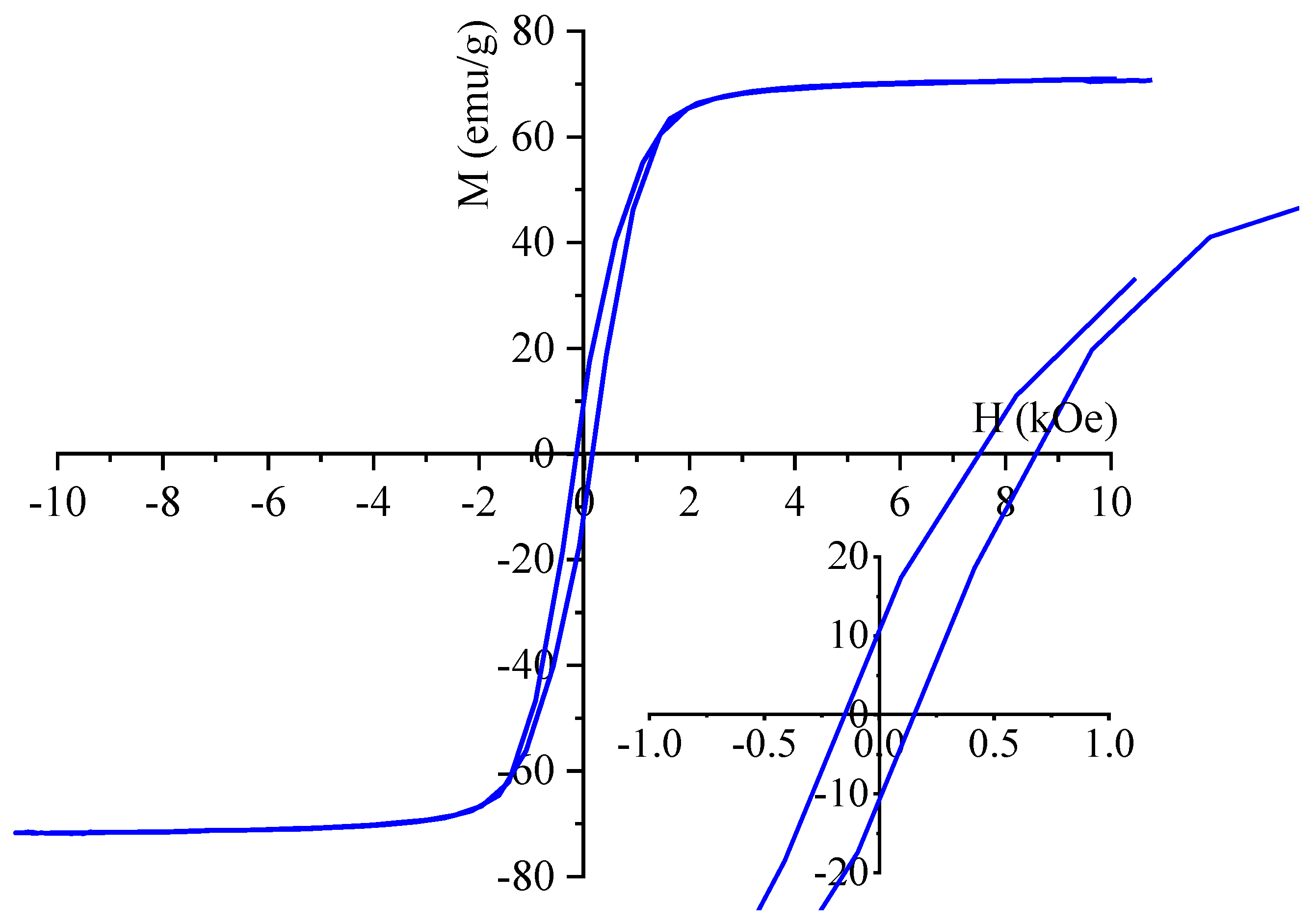

For characterization of the magnetic behaviour of the maghemite sample, VSM measurement was used at room temperature. The saturation magnetization (Ms) of sample was 71.1 emu/g at 10 kOe magnetic field (

Figure 5). A comprehensive review of the extant literature reveals a broad spectrum of Ms values ranging from 10 to 90 emu/g. Our maghemite nanoflowers are commensurate with this range. [

32,

33]. Our Ms value is slightly smaller than the reported Ms value of the bulk maghemite is 75–92 emu g

−1 at room temperature [

34]. On the magnetization curve is visible narrow hysteresis loop with low coercivity (Hc: 160 Oe) and low remanent magnetization (Mr: 10.8 emu/g) which are small values, which indicate the ferromagnetic nature of the synthesized particles at room temperature. The narrow hysteresis loops also indicate that the prepared samples can be easily demagnetised, as is clearly shown in

Figure 5.

2.2. Results of the Cobalt Adsorption Tests by Using of Chlorella vulgaris

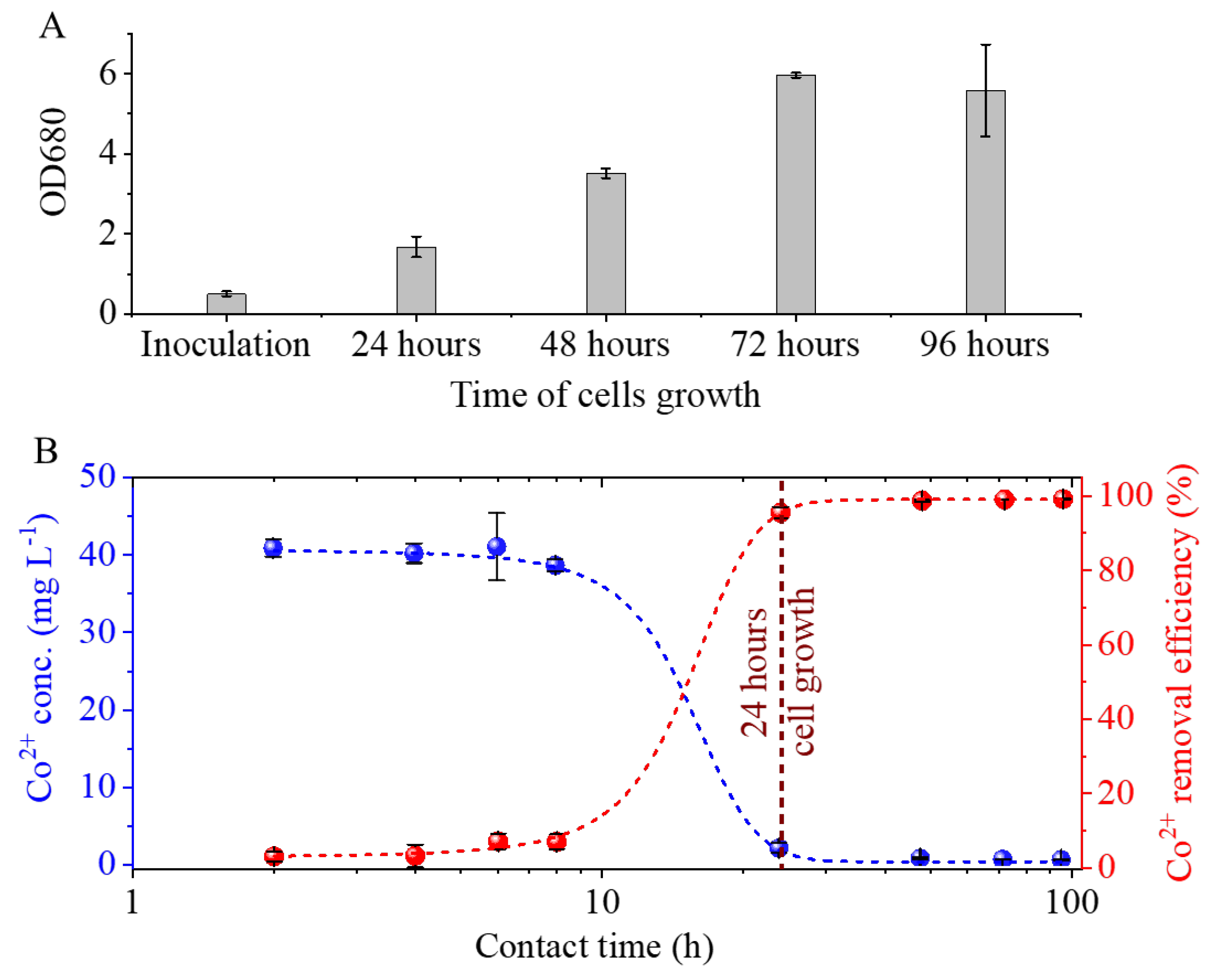

Cobalt elicited only a marginal, non-significant inhibition of growth relative to the control. Following a 24-hour period of inoculation, there was an observed increase in the initial OD680 values from 0.5 to 1.67 (

Figure 6A). The exponential phase was observed to last for a period of 72 hours following inoculation, at which point it transitioned into the plateau phase. The highest OD680 value recorded was 6 at this time point. The cobalt concentration does not exhibit a significant decrease during the eight-hour period of algal cell growth because the number of cells available for bioaccumulation is insufficient to take up the cobalt ions (

Figure 6A,B). Following a 24-hour period of inoculation, a substantial increase in the quantity of algae binding significant amounts of cobalt is observed. The initial concentration of Co

2+ in the medium was 41.3 mg/L, which decreased to 1.8 ± 0.6 mg/L within 24 hours. This result indicates a removal efficiency of 96 ± 2%.

2.3. Results of Magnetic Separation of Cobalt Adsorbed Chlorella vulgaris

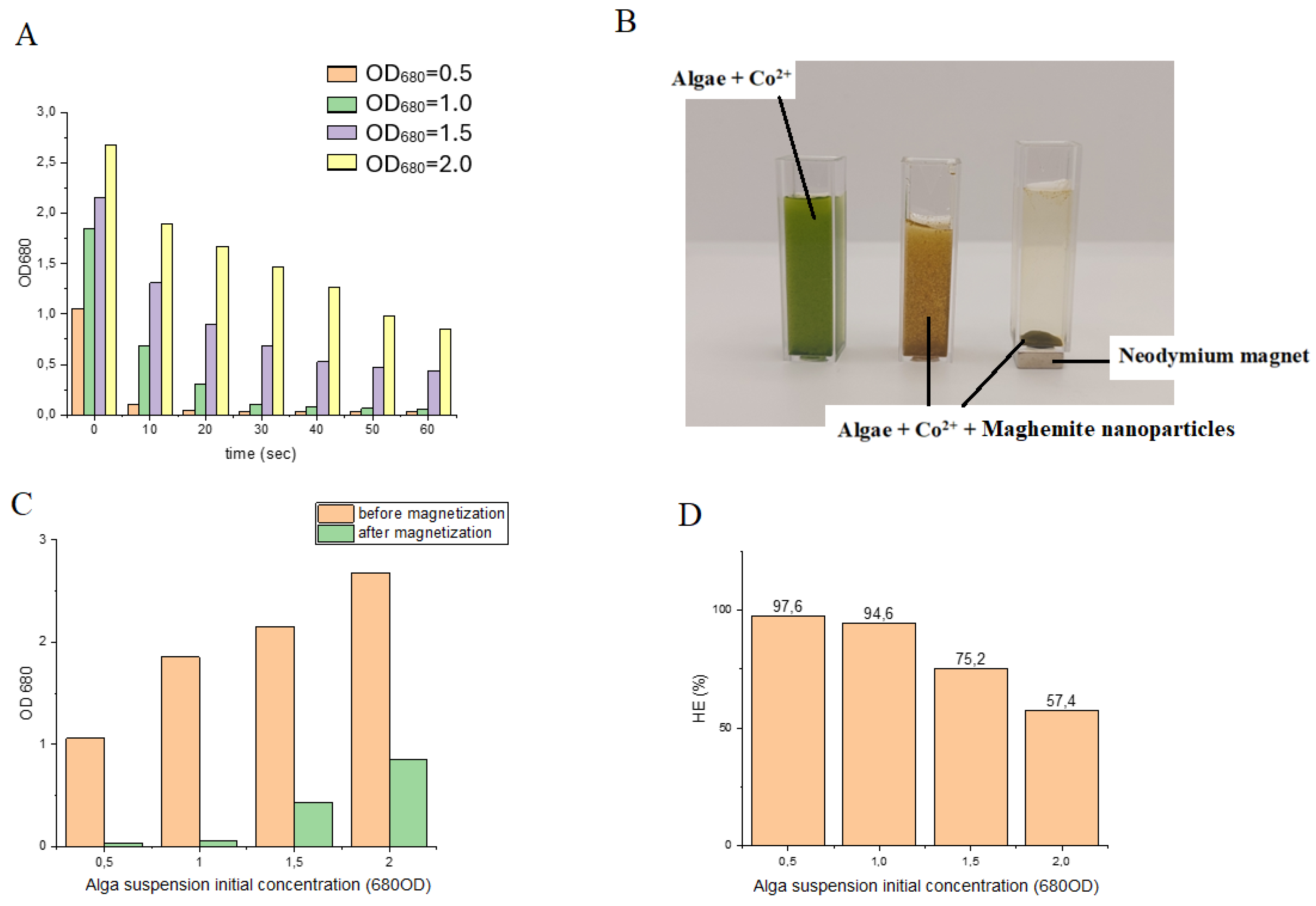

Magnetic separation was accomplished with high efficiency at low algal biomass concentrations, specifically 0.9 g/L (OD₆₈₀ = 0.5) and 1.8 g/L (OD₆₈₀ = 1.0), using 4 mL suspensions (

Figure 7A). Under these conditions, harvesting efficiencies of 97.64% and 94.61% were obtained, respectively. In contrast, at higher algal biomass concentrations, the recovery rates within 60 s decreased to 75.25% and 57.43% (

Figure 7C,D). Extending the magnetization time did not improve the separation efficiency, indicating that binding between nanoparticles and algal cells rapidly reached equilibrium. These observations suggest that, at low cell densities, maghemite nanoparticles readily interact with and adhere to the algal cell surfaces, resulting in near-complete recovery. At higher algal concentrations, however, the reduced efficiency is likely attributable to the limited availability of nanoparticles relative to cell surface binding sites. Consequently, it can be anticipated that increasing the nanoparticle concentration would enhance recovery efficiency under these conditions.

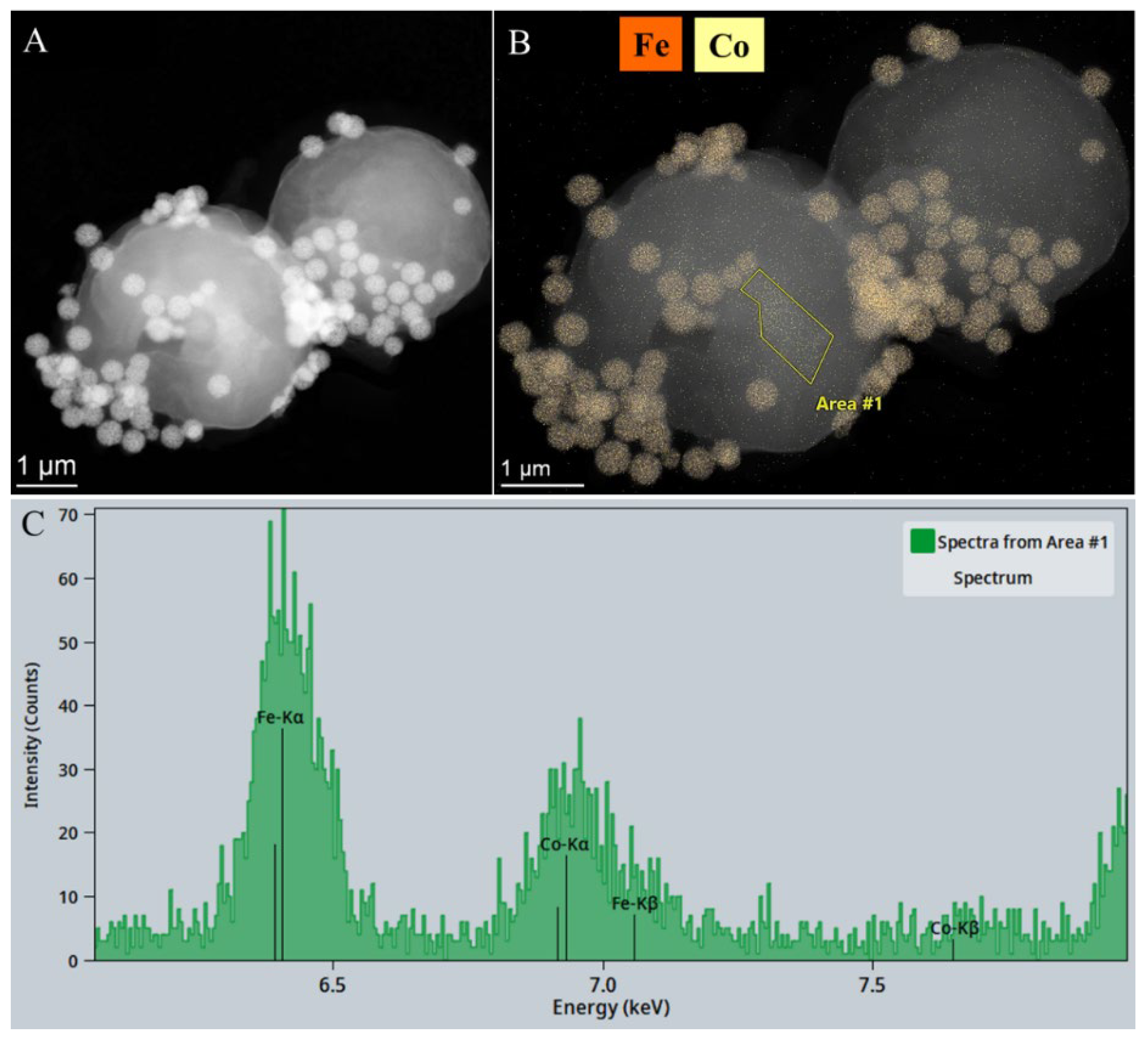

The addition of maghemite nanoparticles to the cobalt-binding algae was followed by a separation process from the purified water sample via magnetic separation. The presence of cobalt was confirmed through a combination of electron microscopic examination, elemental mapping and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). As illustrated in the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image, the maghemite nanoparticles are distinguished by a heightened level of contrast (

Figure 8A). The element map shows iron enrichment, which corresponds to the location of the maghemite nanoparticles on the algae cells (

Figure 8B). The elemental map shows the position of cobalt also, indicating that cobalt is detectable across the entire surface of the algae cells, which also confirms that

Chlorella vulgaris is an excellent choice for removing cobalt through bioaccumulation (

Figure 8B). The presence of cobalt on the surface of the algae was also confirmed by EDS measurements (

Figure 8C). Furthermore, maghemite was also well bound on the surface of the algae, and therefore, by applying a magnetic field, the algae could be effectively recovered from the purified water sample.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The maghemite nanoflowers were synthesized from iron (II) chloride tetrahydrate, FeCl2 ∙ 4 H2O, MW: 198.81 g/mol (VWR Int. Ltd., B-3001 Leuven, Belgium) and iron (III) chloride, anhydrous, FeCl3, MW: 162.20 g/mol (VWR Int. Ltd., B-3001 Leuven, Belgium). Ethylene glycol, HOCH2CH2OH, (VWR Int. Ltd., F-94126 Fontenay-sous-Bois, France) was applied as solvent. For amine functionalization and for coprecipitation of the nanoparticles, monoethanolamine (MEA), NH2CH2OH (Merck KGaA, D-64271 Darmstadt, Germany) and sodium acetate, CH3COONa (ThermoFisher GmbH, D-76870 Kandel, Germany) were used.

3.2. Synthesis of the Amine Functionalized Maghemite Nanoflowers

The solvothermal synthesis of the maghemite happened in Teflon lined hydrothermal autoclave (with 150 mL volume), at 200 °C, 12 hours. In first step iron (II) chloride tetrahydrate (18 mmol) and anhydrous iron (III) chloride (36 mmol) was solved in ethylene glycol (100 mL). In a second step, sodium acetate (90 mmol) was added in the solution of iron precursors and stirred at room temperature until dissolution of the CH3COONa, followed by the addition of 60 mL (0.9921 mol) monoethanolamine. The solution was transferred in autoclave, after it was heat at 200 °C, 12 hours. After, from the cooled dispersion the solid phase was separated by magnet from the ethylene glycol phase, and it was washed by distilled water, finally rinsed with ethanol (96 Vol%). The maghemite nano powder was dried 90 °C overnight.

3.3. Cobalt Adsorption Tests

The

Chlorella vulgaris strain was obtained from the Advanced Materials and Intelligent Technologies Higher Education and Industrial Cooperation Centre at the University of Miskolc.

C. vulgaris strain was maintained in modified “endo” medium [

22] containing KNO

3 3 g/L, KH

2PO

4 1.2 g/L, MgSO

4·7H

2O 1.2 g/L, citric acid 0.2 g/L, FeSO

4·7H

2O 0.016 g/L, CaCl

2·2H

2O 0.105 g/L, trace element stock solution 1mL/L. For trace elements a stock solution has been prepared containing Na

2EDTA 2.1 g/L, H

3BO

3 2.86 g/L, ZnSO

4·7H

2O 0.222 g/L, MnCl

2·4H

2O 1.81 g/L, Na

2MoO

4·2H

2O 0.021g/L, and CuSO

4·5H

2O 0.07g/L. After solution of all components of the medium the pH was adjusted to 6.5±0,2 and the temperature was controlled at 24 °C.

For growing of C. vulgaris a glass tubular air lift photo-bioreactor system was constructed, which consisted of Hailea V20 membrane compressor with a capacity of 20 L/min air flow with electric power 15 W. The reactor system contained 9 pieces of glass vessel with a volume of 500 mL. The air flow rate was 4,5 L/min in each reactor vessel. Reactors were illuminated with. LED lamps with a light intensity of 3000 lumen. Inoculation of reactors were carried out with concentrated Chlorella v. culture containing 5x108 cell/mL with an inoculation ratio of 1%. Initial cell density at inoculation could have been characterized by 5x107 cell/mL in the reactor vessels.

To study the cobalt bioaccumulation process with C. vulgaris microalga, cobalt stock solution was measured into the culture medium prior to inoculation. Thus, the initial Co2+ concentration of the medium reached 41.3mg/L ±3.6. After cobalt addition the medium was inoculated with C. vulgaris culture with 2% inoculation volume ratio. The initial cell density could be characterized by OD680 value 0.5±0.06.

To study the cobalt removal kinetics samples were taken for Co2+analysis immediately after cobalt addition from the uninoculated medium, then 2., 4., 6., 8., 24., 48., 72., and 96. hours after inoculation. The algae that bound cobalt (II) ions were removed from the suspension using a syringe filter (0.2 micron) after sampling.

The concentration of cobalt ions in the supernatant was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES). The ICP instrument was a Varian 720-ES simultaneous multielement spectrometer with axial plasma view. The analytical parameters were as follows: RF generator frequency, 40 MHz; sample introduction device, V-groove nebulizer with Sturman–Masters spray chamber; sample uptake rate, 2.1 mL/min; signal integration time, 8 s; number of readings, 3 per sample. Calibration was performed using a series of standard solutions prepared from a 1000 mg/L single-element cobalt stock solution (Certipur, Merck Ltd.).

Co

2+ removal efficiency was calculated by the following equation:

[Co2+]t0 = initial concentration of Co2+ given in mg/L,

[Co2+]t1 = Co2+ concentration of the given time point after cobalt addition of the cell free supernatant.

3.4. Magnetic Separation Tests of the Cobalt Bonded Algae

In the experiments, the time and efficiency of magnetic separation of cobalt-adsorbed algal biomass at different algal concentrations were measured. Concentrated Chlorella v. culture containing 4,2 mg/L dry biomass was diluted. Different concentrations of algal suspension were used: 3,6 mg/L (= 2,0±0,1 OD680), 2,7 mg/L (= 1,5±0,1 OD680), 1,8 mg/L (= 1,0±0,1 OD680), 0,9 mg/L (= 0,5±0,1 OD680), while the concentration of maghemite nanoparticles was fixed at 0.511 g/L. 100 mL alga suspension of different concentrations a cobalt solution of 60 mg/L was added, and it was mixed with air bubbling for 30 min. Subsequently, the algal biomass was treated with maghemite nanoparticles at a concentration of 0.511 g/L for 10 min using the air bubbling compressor. The pH was adjusted to 6,5 with phosphate buffer and the temperature was 24 °C.

To evaluate the binding efficiency of nanoparticles to the surface of cobalt-loaded algal cells, the sedimentation rate in a magnetic field was determined. An aliquot of 4 mL algal suspension was placed into a custom cuvette (10 × 10 × 3 mm) equipped with an N45 neodymium magnet fixed to its base. The cuvette was positioned in the spectrophotometer holder, and sedimentation was monitored by recording the change in optical density over time. Optical density was measured at 680 nm using a UV1100/UV-1200 Double beam spectrophotometer (Frederiksen).

The harvesting efficiency (HE%) of the process was calculated from Equation:

OD0 is the initial absorbance of microalgae cultivation at a wavelength of 680 nm,

OD1 is the absorbance at the same wavelength of the supernatant liquid that separates from the microalgae-particles flocs after the application of the magnetic field.

3.5. Characterization Technics

The morphological and fine structural characterization and measurements of the particle’s sizes of the maghemite nanoflower were carried by High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, Talos F200X G2 electron microscope with field emission electron gun, X-FEG, accelerating voltage: 20-200 kV, ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The sizes of maghemite particles were determined using the scalebar in the TEM images, based on pixel ratios using Image J software [

23]. Crystalline phase identification of the individual nanoparticles was carried by selected area electron diffraction (SAED), in which SmartCam digital search camera (Ceta 16 Mpixel, 4k x 4k CMOS camera, Thermo Scientific, Wal-tham, MA, USA) was used with a high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector. For the electron microscopy examination, the maghemite particles were suspended in dist. water, then dropped onto a copper grid and dried. (Ted Pella Inc., 4595 Redding, CA 96003, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement and Rietveld analysis was used to identification of the phase composition of the maghemite sample. The XRD examination by Bruker D8 diffractometer (Cu-Kα source) was carried in parallel beam geometry (Göbel mirror) with Vantec detector. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to investigate the amine-functionalized maghemite nanoflowers, with the aim of identifying the surface functional groups. The spectroscopic measurement was performed with Bruker Vertex 70 instrument (Bruker Optics GmbH & Co. KG, 76275 Ettlingen, Germany) in transmission mode, in KBr pellet (10 mg maghemite in 200 mg KBr). The electrokinetic potential measurements of the maghemite particles were carried based on electrophoretic mobility by applying laser Doppler electrophoresis with an Anton Paar Litesizer DLS 500 (Anton Paar GmbH, 8054 Graz, Austria). The magnetization properties of the sample, i.e., saturation magnetization (Ms), residual magnetization (Mr) and the coercivity (Hc) were studied by self-developed vibrating-sample magnetometer (VSM) with water-cooled Weiss-type electromagnet (by University of Debrecen). For the VSM test the sample was pelletized with mass of 20 mg. The magnetization (M) was measured as a function of magnetic field (H) up to 150,000 A/m field strength at room temperature.

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

4. Conclusions

We have prepared maghemite nanoparticles that can be effectively used to magnetically separate bioaccumulating algae that have bound toxic heavy metal ions from water. The bioaccumulation study of the algae demonstrates their ability to bind large amounts of cobalt from water samples, reducing the Co²⁺ concentration from 41.3 mg/L to 0.5 ± 0.1 mg/L within 48 hours achieving a 99 ± 0.2 % removal efficiency. Analysis of the maghemite nanoflowers with a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) revealed that they can be easily separated with the algae together due to their high saturation magnetization (Mr: 71.1 emu/g). Magnetic deposition studies of the algae also confirmed the rapid magnetic separation; the algal biomass attached to maghemite nanoparticles was separated from the nutrient solution with an efficiency of 57.43-97.64 % within 60 seconds. This efficiency was found to be concentration-dependent, i.e., it varied according to the initial biomass concentration. The elemental maps obtained from electron microscopy studies show that the adsorbed cobalt is homogeneously distributed on the surface of the algae and maghemite nanoparticles were also identified on their surface.

These results highlight the potential of low-cost, biocompatible, and widely available magnetic nanoparticles in wastewater treatment, particularly for the removal of heavy metals, offering a promising approach for sustainable environmental remediation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T. F., L. V. and B. V.; methodology, T. F., K. G., A. M.I., L. D., P.K. and F. K; software, M. N. and B. V.; formal analysis, F. K., P. K., T.F., A. M.I. and L. D.; resources, T. F., P.K., L.V. and B. V.; data curation, K. G., L.V., M.N., and T.F.; writing—original draft preparation T.F., P.K., L. V. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, M. N., L. V., B.V. and B.V.,; visualization, T. F. and L.V.; supervision, L. V. and B.V.

Funding

The creation of this scientific communication was supported by the University of Miskolc with funding granted to the author László Vanyorek within the framework of the institution’s Scientific Excellence Support Program. (Project identifier: ME-TKTP-2025-027).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The creation of this scientific communication was supported by the University of Miskolc with funding granted to the author László Vanyorek within the framework of the institution’s Scientific Excellence Support Program. (Project identifier: ME-TKTP-2025-027).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HRTM |

High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| VSM |

Vibrating Sample Magnetometry |

| NMC |

Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide |

| NCA |

Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide |

| LMO |

Lithium Manganese Oxide |

| PDDA |

poly diallyldimethylammonium chloride |

| PEI |

polyethylenimine |

| APTES |

3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane |

| SAED |

Selected Area Electron Diffraction |

| HAADF |

High-Angle Annular Dark-Field |

| ICP-AES |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry |

References

- Battery University. Types of Lithium-Ion. Available online: https://batteryuniversity.com/article/bu-205-types-of-lithium-ion (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology. 2012, 101, 133–164.

- Gunatilake, S.K. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science Studies. 2015, ISSN 2912-1309.

- Barakat, M.A. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2011, 4, 361–377. [CrossRef]

- Noman, E.A.; Al-Gheethi, A.A.; Al-Sahari, M.; et al. Applied Water Science. 2024, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.; Scheufele, F.B.; Espinoza-Quiñones, F.R.; et al. Journal of Materials Science. 2018, 53(11), 7976–7995. [CrossRef]

- Balzano, S.; Sardo, A.; Blasio, M.; et al. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, E.R.S.; Nuravivah, R. E3S Web of Conferences. 2018, 31, 05010. [CrossRef]

- Je, J.; Yang, C.; Xia, L. Microorganisms. 2023, 1(2), 538.

- Kőnig-Péter, A.; Kilár, F.; Felinger, A.; Pernyeszi, T. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society. 2014, Paper 5988-EC.

- Veglio, F.; Beolchini, F. Hydrometallurgy. 1997, 44, 301–316.

- Ahalya, N.; Ramachandra, T.V.; Kanamadi, R.D. Research Journal of Chemistry and Environment. 2003, 7(4), 71–79.

- Abdelfattah, A.; Ali, S.S.; Ramadan, H.; El-Aswar, E.I.; Eltawab, R.; Ho, S.-H.; Elsamahy, T.; Li, S.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Schagerl, M.; Kornaros, M.; Sun, J. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. 2023, 13(6), 100205.

- Markeb, A.A.; Llimós-Turet, J.; Ferrer, I.; Blánquez, P.; Alonso, A.; Sánchez, A.; Moral-Vico, J.; Font, X. Water Research. 2019, 159, 490–500. [CrossRef]

- Markeb, A.A.; Llimós-Turet, J.; Ferrer, I.; Blánquez, P.; Alonso, A.; Sánchez, A.; Moral-Vico, J.; Font, X. Water Research. 2019, 159, 490–500.

- Procházková, G.; Podolová, N.; Safarik, I.; Zachleder, V.; Brányik, T. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2013, 112, 213–218. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Suh, H.; Chang, T. Environmental Engineering Research. 2012, 17(3), 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Ramos Guivar, J.A.; et al. RSC Advances. 2017, 7, 28763–28779. [CrossRef]

- Meftah, S.; et al. Langmuir. 2024, 40(43), 22673–22683. [CrossRef]

- Teja, A.S.; Koh, P.Y. Progress in Crystal Growth and Characterization of Materials. 2009, 55(1–2), 22–45. [CrossRef]

- Kuchma, E.A.; et al. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2022, 24, 25. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; et al. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2021, 9, 774854. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Rana, N. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology. 2015, 4(11). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, Y.W.; Liao, C.S.; Yan, C.H.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, S.Y. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2004, 280, 327–333. [CrossRef]

- Tavan, Y.; Hosseini, S.H.; Olazar, M. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2015, 54(51), 12937–12947.

- Strazisar, B.R.; Anderson, R.R.; White, C.M. Energy & Fuels. 2003, 17(4), 1034–1039.

- Melhi, S. Crystals. 2023, 13, 1301. [CrossRef]

- Strazisar, B.R.; Anderson, R.R.; White, C.M. Energy & Fuels. 2003, 17(4), 1034–1039.

- Rose, A.N.; Hettiarachchi, E.; Grassian, V.H. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2022, 614, 75–83.

- Wang, H.; Su, W.; Tan, M. Innovation. 2020, 1(1), 100020.

- Bruce, I.J.; et al. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2004, 284, 145–160.

- Nuryono, N.; Rosiati, N.M.; Rusdiarso, B.; et al. SpringerPlus. 2014, 3, 515. [CrossRef]

- El-Dib, F.I.; et al. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum. 2020, 29(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Dresco, P.A.; et al. Langmuir. 1999, 15(6), 1945–1951. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).