Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Data Analysis

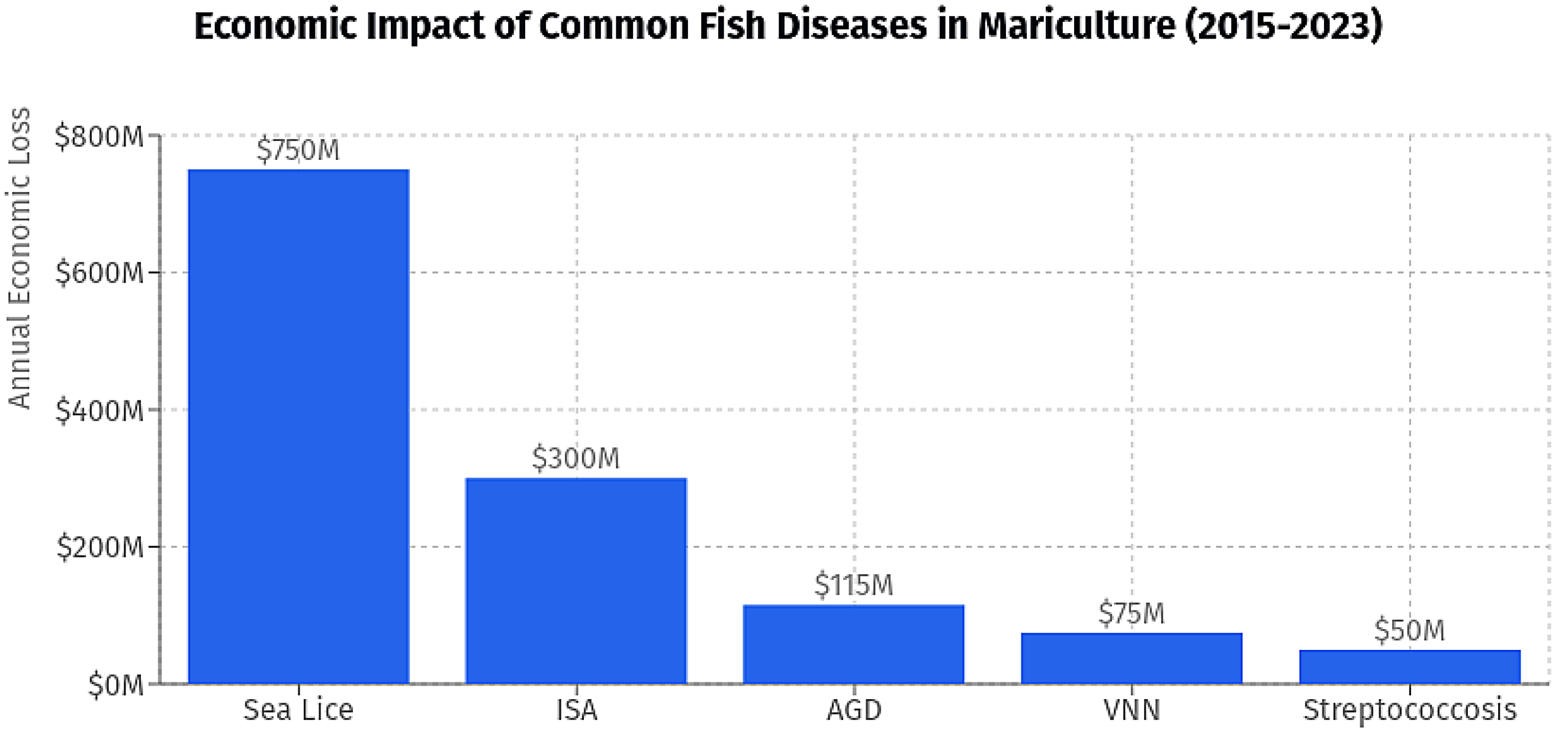

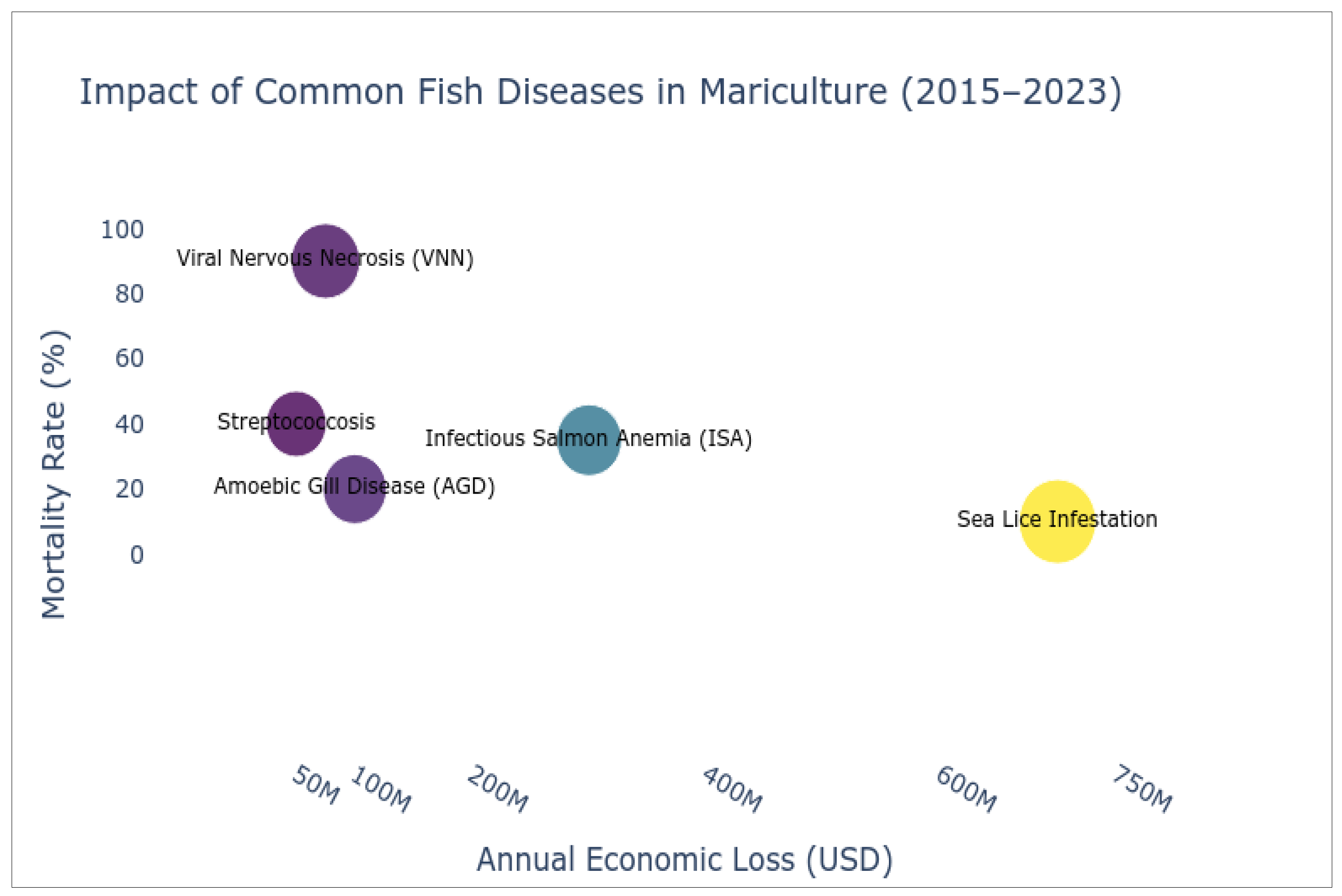

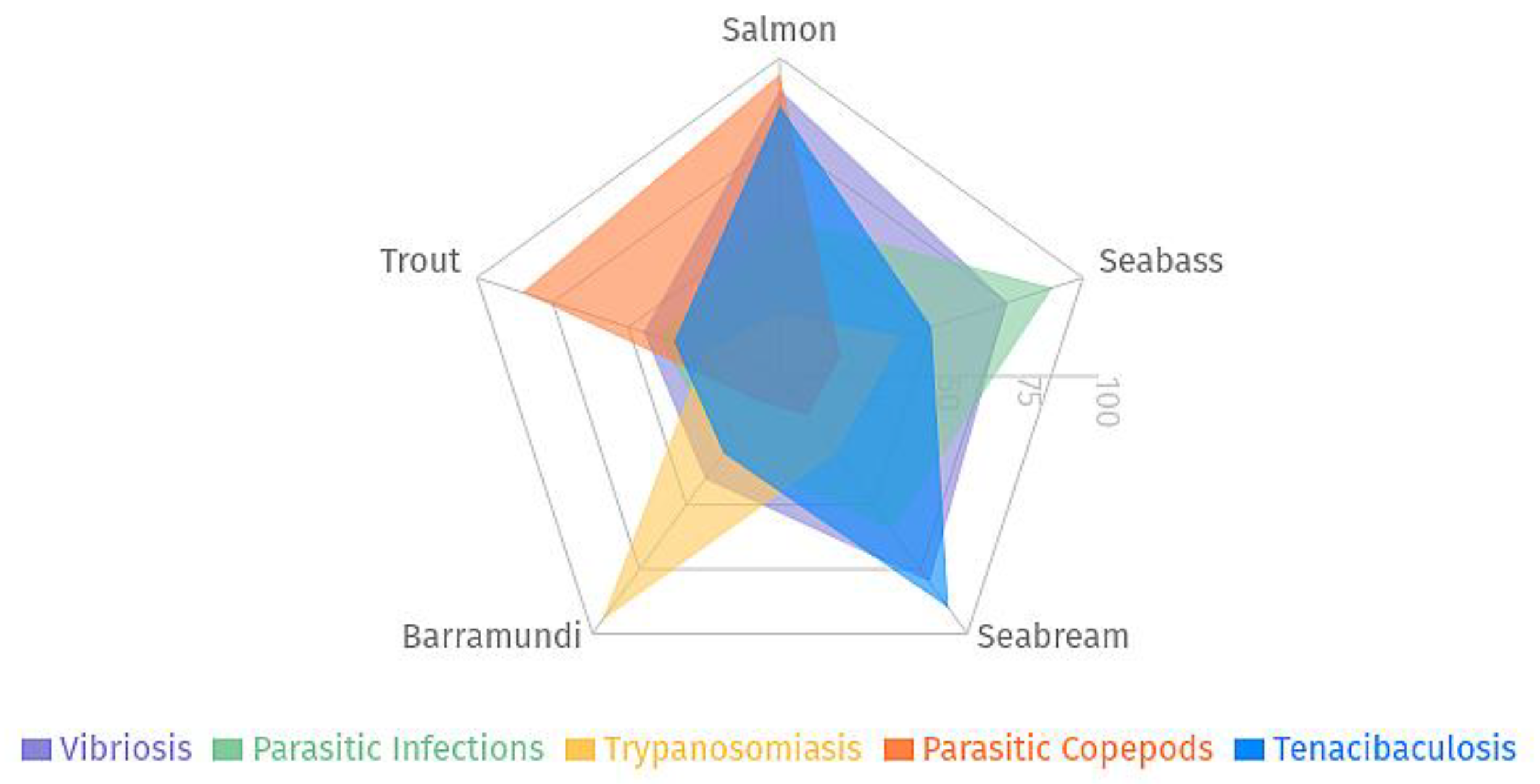

2. Open Sea Cage and Disease Management

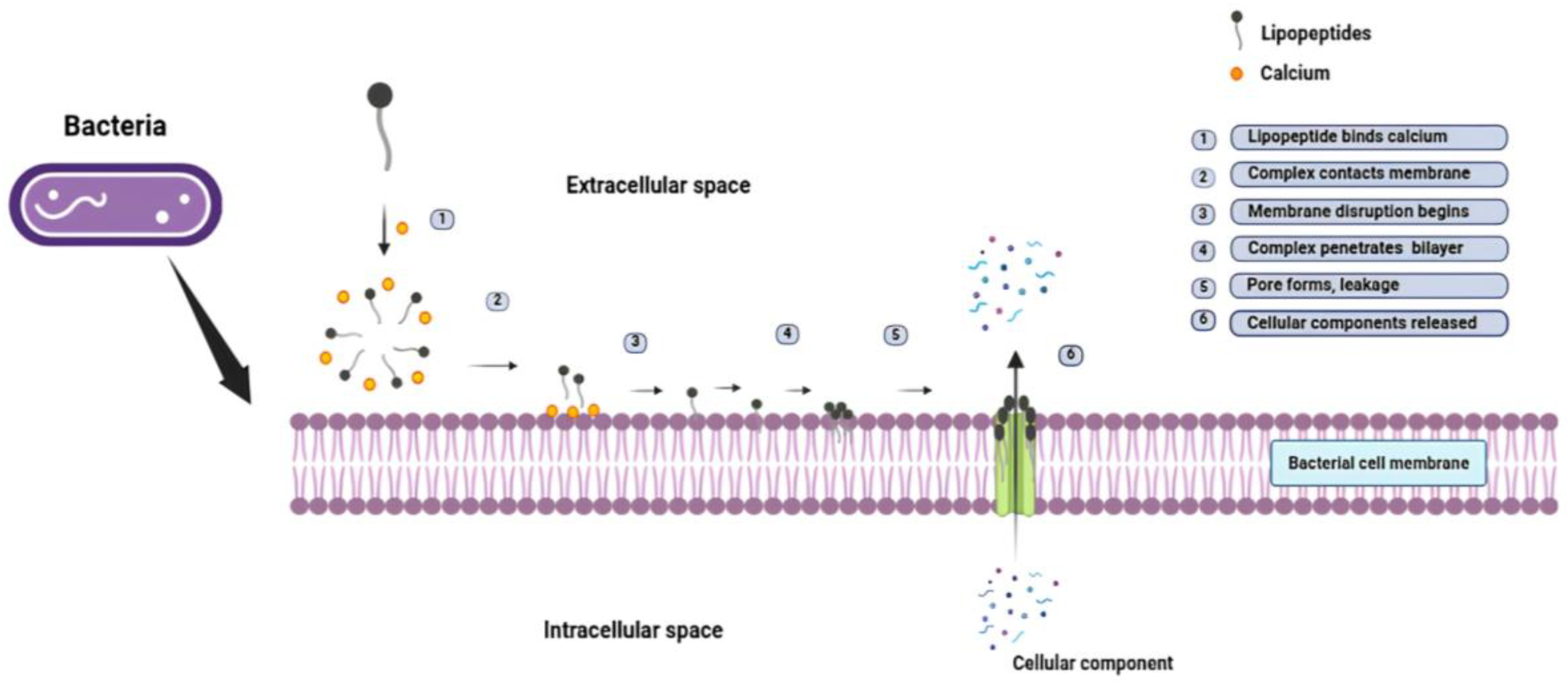

3. Structural Features and Therapeutic Potential of Marine-Derived Lipopeptides

4. Multifunctional Lipopeptides for Health Management in Open-Sea Cage Aquaculture

6. Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Roles of Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides in Sustainable Aquaculture

7. Challenges and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Clinical trial number

Ethics declaration

References

- Oddsson, G.V. A Definition of Aquaculture Intensity Based on Production Functions—The Aquaculture Production Intensity Scale (APIS). Water 2020, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U.R.; Pierruci, A.; Oyinlola, M.A.; Cannas, R.; Froese, R.; Glaser, S.; Jacquet, J.; Kaiser, B.A.; Issifu, I.; Micheli, F.; et al. Aquaculture over-optimism? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, R.; Uehara, M.; Seki, D.; Kinjo, M. Supply Chain-Based Coral Conservation: The Case of Mozuku Seaweed Farming in Onna Village, Okinawa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troell, M.; Costa-Pierce, B.; Stead, S.; Cottrell, R.S.; Brugere, C.; Farmery, A.K.; Little, D.C.; Strand, Å.; Pullin, R.; Soto, D.; et al. Perspectives on aquaculture's contribution to theSustainable Development Goalsfor improved human and planetary health. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 251–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishery and aquaculture statistics – Yearbook 2021. (2024). FAO. [CrossRef]

- Vorona, N.; Iegorov, B. FISH FARMING IS A PROMISING BRANCH OF ENSURING FOOD SECURITY OF THE EARTH'S POPULATION. Grain Prod. Mix. Fodder’s 2023, 23, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintola, S.L.; Chávez-Chong, C.O.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Chong-Carrillo, O.C.-C.; García-Guerrero, M.U.; Michán-Aguirre, L.; Nolasco-Soria, H.; Cupul-Magaña, F.; Vega-Villasante, F. The prawns of the genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) with commercial importance: a patentometric view. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2017, 44, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Asche, F.; Garlock, T. Economics of Aquaculture Policy and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Aquaculture: A Boon to Today’s World-A Review. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.F.; Yacout, D.M.M. Aquaculture in Egypt: status, constraints and potentials. Aquac. Int. 2016, 24, 1201–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickney, R. R., & Treece, G. D. (2012). History of aquaculture. In J. H. Tidwell (Ed.), Aquaculture production systems (1st ed., pp. 15–50). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Allan, G. L., Fielder, D. S., Fitzsimmons, K. M., Applebaum, S. L., & Raizada, S. (2009). Inland saline aquaculture. In New technologies in aquaculture (pp. 1119–1147). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y. Freshwater Aquaculture Mapping in “Home of Chinese Crawfish” by Using a Hierarchical Classification Framework and Sentinel-1/2 Data. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Study on Water Purification of Freshwater Aquaculture Pond based on Correlation Analysis. Front. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Vaishnav, A.; Deb, S.; Kashyap, S.; Debbarma, P.; Devati; Gautam, P. ; Pavankalyan, M.; Kumari, K.; Verma, D.K. Re-Circulatory Aquaculture Systems: A Pathway to Sustainable Fish Farming. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2024, 24, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Deng, J.; Ye, Z.; Gan, M.; Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Yang, W.; Xiao, G. Coastal Aquaculture Mapping from Very High Spatial Resolution Imagery by Combining Object-Based Neighbor Features. Sustainability 2019, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, D.; Ottinger, M.; Leinenkugel, P. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Coastal Aquaculture Derived from Sentinel-1 Time Series Data and the Full Landsat Archive. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.R.; Alleway, H.K.; McAfee, D.; Reis-Santos, P.; Theuerkauf, S.J.; Jones, R.C. Climate-Friendly Seafood: The Potential for Emissions Reduction and Carbon Capture in Marine Aquaculture. BioScience 2022, 72, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azra, M.N.; Okomoda, V.T.; Tabatabaei, M.; Hassan, M.; Ikhwanuddin, M. The Contributions of Shellfish Aquaculture to Global Food Security: Assessing Its Characteristics From a Future Food Perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, T. (2002). Yellowtail, Seriola quinqueradiata. In C. D. Webster & C. Lim (Eds.), Nutrient requirements and feeding of finfish for aquaculture (1st ed., pp. 131–146). CABI Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Frazer, L.N. Sea-Cage Aquaculture, Sea Lice, and Declines of Wild Fish. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatak, G.; Das, B.K.; Parida, P.; Roy, A.; Das, A.K.; Lianthuamluaia, L.; Ekka, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Mondal, K.; Debnath, S. Effectiveness of pen aquaculture in enhancing small scale fisheries production and conservation in a wetland of India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 8, 1506096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Lee, H.B. Commercial marine fish farming in Singapore. Aquac. Res. 1997, 28, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, W.M.A.; Huallpa, L.; Zúñiga, A. Development of a Technological System of Floating Cages in the Sea for the Farming of Marine Fish Within the Coastline of ILO. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heungwoo Nam, Sunshin An, Chang-Hwa Kim, Soo-Hyun Park, Yong-Whan Kim, & Seok-Ho Lim. (2014). Remote monitoring system based on ocean sensor networks for offshore aquaculture. 2014 Oceans - St. John’s, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Xiaomei Xu, & Zhang, X. (2007). A remote acoustic monitoring system for offshore aquaculture fish cage. 2007 14th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice, 86–90. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wei, Q.; An, D. Intelligent monitoring and control technologies of open sea cage culture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.R.K.; Rathore, G.; Verma, D.K.; Sadhu, N.; Philipose, K.K. Vibrio alginolyticusinfection in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer, Bloch) reared in open sea floating cages in India. Aquac. Res. 2011, 44, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milich, M.; Drimer, N. Design and Analysis of an Innovative Concept for Submerging Open-Sea Aquaculture System. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 44, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A., Sánchez, P., Armesto, J. A., Guanche, R., Ondiviela, B., & Juanes, J. A. (2018). Experimental and numerical modelling of an offshore aquaculture cage for open ocean waters. Volume 7A: Ocean Engineering, V07AT06A053. [CrossRef]

- Moe, H.; Dempster, T.; Sunde, L.M.; Winther, U.; Fredheim, A. Technological solutions and operational measures to prevent escapes of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) from sea cages. Aquac. Res. 2007, 38, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milich, M.; Drimer, N. Design and Analysis of an Innovative Concept for Submerging Open-Sea Aquaculture System. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 44, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T., Arai, K., & Kobayashi, T. (2019). Smart aquaculture system: A remote feeding system with smartphones. 2019 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Consumer Technologies (ISCT), 93–96. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wei, Q.; An, D. Intelligent monitoring and control technologies of open sea cage culture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divu, D.; Mojjada, S.K.; Muktha, M.; Azeez, P.A.; Tade, M.S.; Subramanian, A.; Shree, J.; Anulekshmi, C.; Babu, P.P.S.; Anuraj, A.; et al. Mapping of potential sea-cage farming sites throughspatial modelling: Preliminary operative suggestionsto aid sustainable mariculture expansion in India. Indian J. Fish. 2023, 70, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, G.; Guan, C.-T. Numerical and experimental investigations of hydrodynamics of a fully-enclosed pile-net aquaculture pen in regular waves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, C.; Bearzi, G.; Christensen, V. Marine open cage aquaculture in the eastern Mediterranean Sea: a new trophic resource for bottlenose dolphins. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 440, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Ahmed, M.; Ullah, A.; Albeshr, M.F.; Arai, T. Growth, Yield and Profitability of Major Carps Culture in Coastal Homestead Ponds Stocked with Wild and Hatchery Fish Seed. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsoglou, S.; Costello, M.J.; &, E.S.; Tziha, G.; , E. S.; Tziha, G. Environmental conditions at sea-cages, and ectoparasites on farmed European sea-bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.), and gilt-head sea-bream, Sparus aurata L., at two farms in Greece. Aquac. Res. 1996, 27, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickney, R. R., & Gatlin III, D. (2022). Aquaculture: An introductory text (4th ed.). CABI. [CrossRef]

- Reshma, B., & Kumar, S. S. (2016). Precision aquaculture drone algorithm for delivery in sea cages. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICETECH), 1264–1270. [CrossRef]

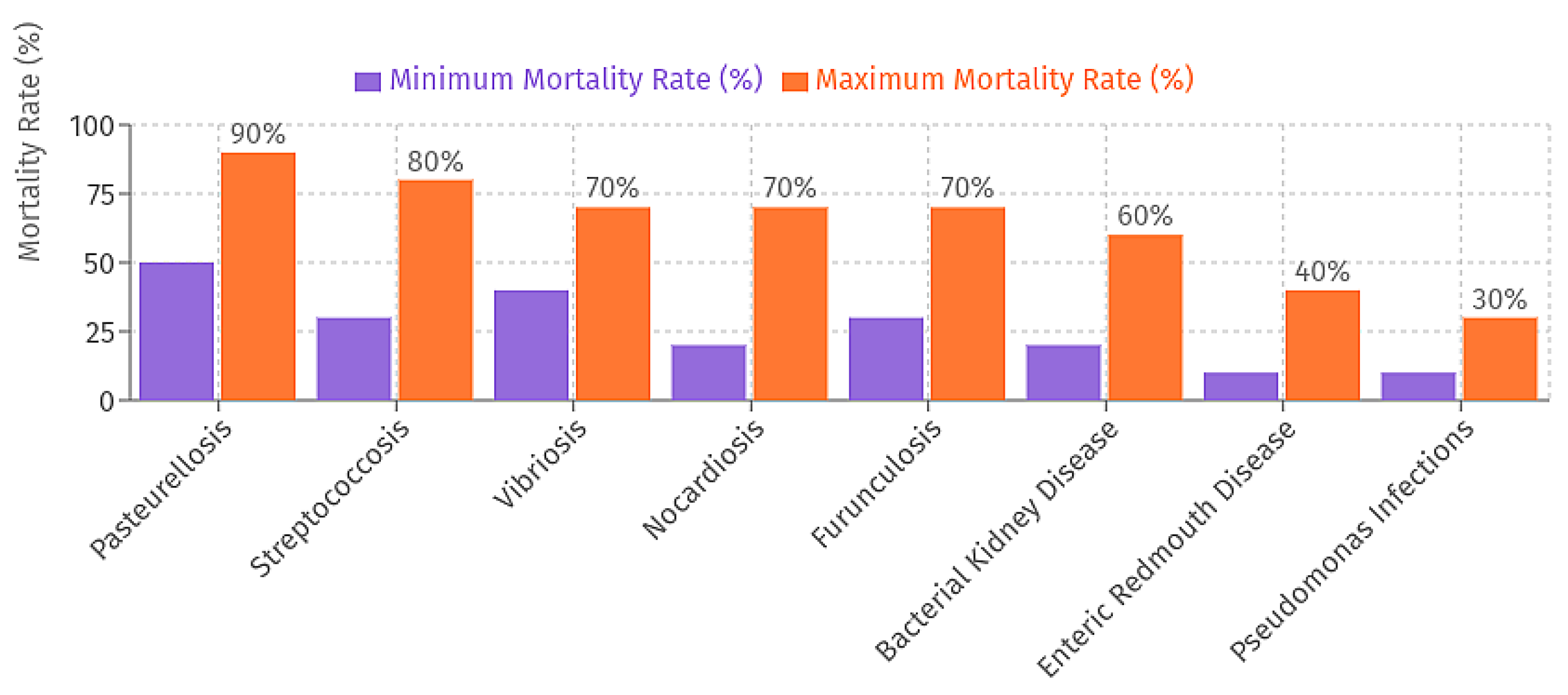

- Jahangiri, L.; MacKinnon, B.; St-Hilaire, S. Infectious diseases reported in warm-water marine fish cage culture in East and Southeast Asia—A systematic review. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 2081–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Sato, H.; Zhang, J. Outbreak of trypanosomiasis in net-cage cultured barramundi, Lates calcarifer (Perciformes, Latidae), associated with Trypanosoma epinepheli (Kinetoplastida) in South China Sea. Aquaculture 2019, 501, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, M.; Kazlari, Z.; Papanna, K.; Papaharisis, L.; Oikonomou, S.; Manousaki, T.; Loukovitis, D.; Kottaras, L.; Dimitroglou, A.; Gourzioti, E.; et al. On the trail of detecting genetic (co)variation between resistance to parasite infections (Diplectanum aequans and Lernanthropus kroyeri) and growth in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquac. Rep. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannoy, C.M.; Houghton, J.D.; Fleming, N.E.; Ferguson, H.W. Mauve Stingers (Pelagia noctiluca) as carriers of the bacterial fish pathogen Tenacibaculum maritimum. Aquaculture 2011, 311, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenen, O.; Evans, J.; Berthe, F. Bacterial infections from aquatic species: potential for and prevention of contact zoonoses. Rev. Sci. et Tech. de l'OIE 2013, 32, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantrakajorn, S.; Maisak, H.; Wongtavatchai, J. Comprehensive Investigation of Streptococcosis Outbreaks in Cultured Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, and Red Tilapia, Oreochromis sp., of Thailand. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2014, 45, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, C.R.; Collins, M.D.; Toranzo, A.E.; Barja, J.L.; Romalde, J.L. 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis of Photobacterium damselae and Nested PCR Method for Rapid Detection of the Causative Agent of Fish Pasteurellosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2942–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Fernández, E.; Chinchilla, B.; Rebollada-Merino, A.; Domínguez, L.; Rodríguez-Bertos, A. An Outbreak of Aeromonas salmonicida in Juvenile Siberian Sturgeons (Acipenser baerii). Animals 2023, 13, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobback, E.; Decostere, A.; Hermans, K.; Haesebrouck, F.; Chiers, K. Yersinia ruckeri infections in salmonid fish. J. Fish Dis. 2007, 30, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Eissa, A.E. DIAGNOSTIC TESTING PATTERNS OF RENIBACTERIUM SALMONINARUM IN SPAWNING SALMONID STOCKS IN MICHIGAN. J. Wildl. Dis. 2009, 45, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, T. Pseudomonas anguilliseptica infection as a threat to wild and farmed fish in the Baltic Sea. Microbiol. Aust. 2016, 37, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itano, T.; Kawakami, H.; Kono, T.; Sakai, M. Experimental induction of nocardiosis in yellowtail, Seriola quinqueradiata Temminck & Schlegel by artificial challenge. J. Fish Dis. 2006, 29, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesintha, N.; Jayakumar, N.; Karuppasamy, K.; Madhavi, K. Demographic characteristics and stock assessment of the giant tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon Fabricius, 1798 (Decapoda, Dendrobranchiata) in Pulicat Lake, southeast coast of India. Crustaceana 2022, 95, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, D.V. Biosecurity in Shrimp Farming: Pathogen Exclusion through Use of SPF Stock and Routine Surveillance. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2007, 36, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marana, M.H.; Jørgensen, L.V.G.; Skov, J.; Chettri, J.K.; Mattsson, A.H.; Dalsgaard, I.; Kania, P.W.; Buchmann, K. Subunit vaccine candidates against Aeromonas salmonicida in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0171944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, F.; Islam, S.M.; Hossain, K.; Ferdous, Z.; Siddik, M.A.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Padeniya, U.; Brown, C. ; Shahjahan Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics improved the functionality of aquafeed: Upgrading growth, reproduction, immunity and disease resistance in fish. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2022, 120, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougin, J.; Joyce, A. Fish disease prevention via microbial dysbiosis-associated biomarkers in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 15, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.F.; Santos, E.B.; Esteves, V.I. Oxytetracycline in intensive aquaculture: water quality during and after its administration, environmental fate, toxicity and bacterial resistance. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 11, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Sutherland, I.H.; Sommerville, C.S.; Richards, R.H.; Varma, K.J. The efficacy of emamectin benzoate as an oral treatment of sea lice, Lepeophtheirus salmonis (KrÒyer), infestations in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. J. Fish Dis. 1999, 22, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.R.S.; Madaro, A.; Nilsson, J.; Stien, L.H.; Oppedal, F.; Øverli, Ø.; Korzan, W.J.; Bui, S. Comparison of non-medicinal delousing strategies for parasite (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) removal efficacy and welfare impact on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) hosts. Aquac. Int. 2023, 32, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjøglum, S.; Henryon, M.; Aasmundstad, T.; Korsgaard, I. Selective breeding can increase resistance of Atlantic salmon to furunculosis, infectious salmon anaemia and infectious pancreatic necrosis. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.N.; Banerjee, G. Recent studies on probiotics as beneficial mediator in aquaculture: a review. J. Basic Appl. Zoöl. 2020, 81, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.K.; Chu, J.; Do, N.T.; Brose, F.; Degand, G.; Delahaut, P.; De Pauw, E.; Douny, C.; Van Nguyen, K.; Vu, T.D.; et al. Monitoring Antibiotic Use and Residue in Freshwater Aquaculture for Domestic Use in Vietnam. Ecohealth 2015, 12, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M. A., Ren, H., Ahmed, T., Luo, J., An, Q., Qi, X., & Li, B. (2022). Recent advances in the fabrication, functionalization, and bioapplications of peptide hydrogels. Soft Matter, 18(47), 8809–8832. (Note: Citation [65] was not explicitly in the text but was included in the original references. Assigned based on alphabetical order.).

- Kim, P.I.; Ryu, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Chi, Y.-T. Production of Biosurfactant Lipopeptides Iturin A, Fengycin and Surfactin A from Bacillus subtilis CMB32 for Control of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

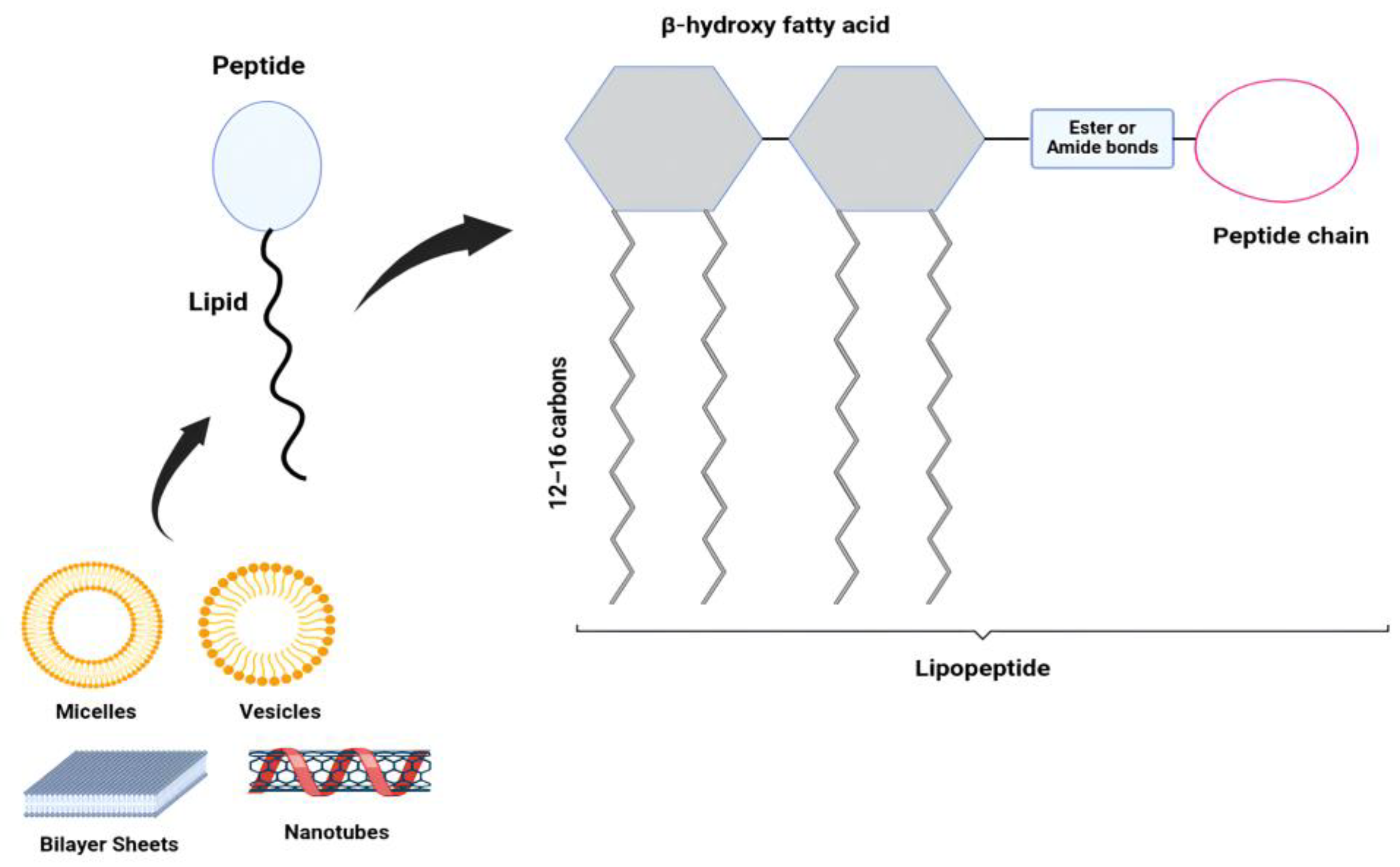

- Mnif, I.; Ghribi, D. Review lipopeptides biosurfactants: Mean classes and new insights for industrial, biomedical, and environmental applications. Pept. Sci. 2015, 104, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Yousef, A.E.; Kivisaar, M. The Lipopeptide Antibiotic Paenibacterin Binds to the Bacterial Outer Membrane and Exerts Bactericidal Activity through Cytoplasmic Membrane Damage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2700–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A., Das, G., Bharti, V. K., & Pandey, N. N. (2024). Lipopeptides as therapeutics: applications and recent advancements. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 50(1), 85–106. (Note: Citation [69] was not explicitly in the text but was included in the original references. Assigned based on alphabetical order.).

- Hanif, A.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zubair, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J.; et al. Fengycin Produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 Inhibits Fusarium graminearum Growth and Mycotoxins Biosynthesis. Toxins 2019, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, S.S.; Baindara, P.; Sharma, S.; Khatri, N.; Grover, V.; Patil, P.B.; Korpole, S. Surfactin Like Broad Spectrum Antimicrobial Lipopeptide Co-produced With Sublancin From Bacillus subtilis Strain A52: Dual Reservoir of Bioactives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janek, T.; Drzymała, K.; Dobrowolski, A. In vitro efficacy of the lipopeptide biosurfactant surfactin-C15 and its complexes with divalent counterions to inhibit Candida albicans biofilm and hyphal formation. Biofouling 2020, 36, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbroich, D.; Özel, M.; Vater, J.; Kamp, R.M.; Pauli, G. Mechanism of Inactivation of Enveloped Viruses by the Biosurfactant Surfactin fromBacillus subtilis. Biologicals 1997, 25, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farace, G.; Fernandez, O.; Jacquens, L.; Coutte, F.; Krier, F.; Jacques, P.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A.; Jacquard, C.; Dorey, S. Cyclic lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis activate distinct patterns of defence responses in grapevine. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 16, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Master, E.R. Fengycins, Cyclic Lipopeptides from Marine Bacillus subtilis Strains, Kill the Plant-Pathogenic Fungus Magnaporthe grisea by Inducing Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Chromatin Condensation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneja, N.; Kaur, H. Insights into Newer Antimicrobial Agents against Gram-negative Bacteria. Microbiol. Insights 2016, 9, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemil, N.; Ben Ayed, H.; Manresa, A.; Nasri, M.; Hmidet, N. Antioxidant properties, antimicrobial and anti-adhesive activities of DCS1 lipopeptides from Bacillus methylotrophicus DCS1. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 144–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricknell, I.; Dalmo, R. The use of immunostimulants in fish larval aquaculture. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2005, 19, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; González-Mazo, E.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Degradation kinetics of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in surface waters: photolysis vs biodegradation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 590-591, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Zhou, S.; Sha, Z.; Sun, C. Characterization of Antifungal Lipopeptide Biosurfactants Produced by Marine Bacterium Bacillus sp. CS30. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, P.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Sun, C.; Nojiri, H. Pumilacidin-Like Lipopeptides Derived from Marine Bacterium Bacillus sp. Strain 176 Suppress the Motility of Vibrio alginolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00450–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Oladipo, A.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Agu, C.V.; Okoye, C.O. Antibiotic resistance in aquaculture and aquatic organisms: a review of current nanotechnology applications for sustainable management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 69241–69274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Yu, X.; Wan, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, Q. Sources of Lipopeptides and Their Applications in Food and Human Health: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Ashouri, G.; Marisaldi, L.; Candelma, M.; Basili, D.; Zimbelli, A.; Notarstefano, V.; Salvini, L.; Randazzo, B.; Zarantoniello, M.; et al. Reducing the Use of Antibiotics in European Aquaculture with Vaccines, Functional Feed Additives and Optimization of the Gut Microbiota. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Sen, R. Antimicrobial potential of a lipopeptide biosurfactant derived from a marine Bacillus circulans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-M.; Rong, Y.-J.; Zhao, M.-X.; Song, B.; Chi, Z.-M. Antibacterial activity of the lipopetides produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M1 against multidrug-resistant Vibrio spp. isolated from diseased marine animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 98, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, K.V.; Bose, A.; Keharia, H. Identification and characterization of novel surfactins produced by fungal antagonist Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 6B. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2013, 61, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathiviraj, R.; Rajeev, R.; Fernandes, H.; Rathna, K.; Lipton, A.N.; Selvin, J.; Kiran, G.S. A gelatinized lipopeptide diet effectively modulates immune response, disease resistance and gut microbiome in Penaeus vannamei challenged with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2021, 112, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Kim, K., Han, H. S., Moniruzzaman, M., Yun, H., Lee, S., & Bai, S. C. (2016). Optimum dietary protein level and protein-to-energy ratio for growth of juvenile parrot fish, Oplegnathus fasciatus. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 48(3), 467–477, (Note: This citation [84] was used for Kim et al. (2018) in-text as no 2018 paper was found in references. Assigned based on content match.). [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L.; Rombaut, G.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W. Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussert, E.; Tourret, M.; Dupuis, C.; Noblecourt, A.; Behra-Miellet, J.; Flahaut, C.; Ravallec, R.; Coutte, F. Evaluation of Antiradical and Antioxidant Activities of Lipopeptides Produced by Bacillus subtilis Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 914713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlayavattanakul, M.; Lourith, N. Lipopeptides in cosmetics. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2010, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, S.; Oz, F.; Bekhit, A.E.A.; Carne, A.; Agyei, D. Production, characterization, and potential applications of lipopeptides in food systems: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaraguppi, D.A.; Bagewadi, Z.K.; Patil, N.R.; Mantri, N. Iturin: A Promising Cyclic Lipopeptide with Diverse Applications. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amillano-Cisneros, J.M.; Fuentes-Valencia, M.A.; Leyva-Morales, J.B.; Savín-Amador, M.; Márquez-Pacheco, H.; Bastidas-Bastidas, P.d.J.; Leyva-Camacho, L.; De la Torre-Espinosa, Z.Y.; Badilla-Medina, C.N. Effects of Microorganisms in Fish Aquaculture from a Sustainable Approach: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Borah, P.; Bordoloi, R.; Pegu, A.; Dutta, R.; Baruah, C. Probiotic bacteria as a healthy alternative for fish and biological control agents in aquaculture. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2024, 16, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter |

Molecular/Technical Characteristics |

Significance for Aquaculture | Sources |

| I. Structural Diversity of Marine Lipopeptides | ||||

| Fatty Acid Chain Variants | Surfactin CS30-1 | C13 β-hydroxy fatty acid; [M+H]+ m/z 1022.71 | Higher antifungal activity against Magnaporthe grisea (induces ROS generation) | [80] |

| Surfactin CS30-2 | C14 β-hydroxy fatty acid; [M+H]+ m/z 1036.72 | Lower bioactivity than CS30-1 despite similar mechanism | [80] | |

| Pumilacidin Homologs | CLP-1 (Bacillus sp. 176) |

C57H101N7O13; targets flagellar genes (flgA, flgP) in Vibrio alginolyticus | Suppresses motility & biofilm formation without cell death | [81] |

| CLP-2 (Bacillus sp. 176) |

C58H103N7O13; differs by -CH2 group from CLP-1 | Reduces pathogen adherence by 70% | [81] | |

| II. Antibiotic Use & Environmental Persistence | ||||

| Global Antibiotic Regulation |

Vietnam | 30 authorized antibiotics (e.g., danofloxacin, sulfadiazine) | High regulatory complexity; favors resistance development | [82] |

| Brazil | Only 2 authorized (florfenicol, oxytetracycline) | Strict control reduces resistance risks | [82] | |

| III. Lipopeptide Delivery Innovations | ||||

| Nano-Encapsulation | Chitosan Nanoparticles | Enhance surfactin stability in seawater by 40%; sustain release >72 hrs | Prevents rapid dilution in open-sea cages | [83] |

| Surface Functionalization | Dopamine-AMPs Coatings | Antibacterial peptides bound to 304 SS/nylon; inhibit S. aureus biofilms by 88.68% | Anti-fouling for cage nets; reduces pathogen colonization | [83] |

| V. Economic & Regulatory Landscape | ||||

| Production Costs | Surfactin Purification | Yield recovery: 3–9% after HPLC; $120–150/kg production cost | Scalability barrier for commercial use | [83] |

| EU Regulatory Status | Lipopeptide Biosurfactants | Classified as “Advanced Bioagents” under EC No 1107/2009 | Fast-track approval for aquaculture biologics | [84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).