1. Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of the human body and serves as a multifunctional barrier that protects against environmental aggressors while regulating hydration, thermoregulation, and immune responses. Maintaining skin integrity is a primary focus of dermatological and cosmetic research, as consumers increasingly demand products that support resilience, comfort, and overall skin health [

1,

2,

3]. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in multifunctional skincare strategies that combine protection, regeneration, and aesthetic benefits in a single formulation.

Topical formulations enriched with natural bioactives have emerged as promising solutions for skin management. Plant-derived compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, and essential oils, are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative effects, which help maintain skin homeostasis and mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation [

4,

5,

6]. They can also support collagen synthesis and maintain skin elasticity, thereby contributing to healthier, more resilient skin. However, the practical application of these bioactives is often limited by their chemical instability, poor solubility, and difficulty penetrating the stratum corneum [

7].

Lipid nanosystems represent a versatile and effective class of nanocarriers for delivering bioactive compounds to the skin. Liposomes, composed of phospholipid bilayers surrounding aqueous cores, can encapsulate both hydrophilic and lipophilic molecules, protecting them from degradation and enhancing their penetration through the stratum corneum. Transferosomes, or ultra-deformable vesicles, improve skin delivery by adapting their shape to traverse intercellular lipid pathways, facilitating deeper penetration into the epidermis and dermis. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) combine the stability of solid matrices with the biocompatibility of lipids, allowing controlled release, sustained bioavailability, and protection against environmental stressors. When incorporated into gel formulations, these lipid carriers not only enhance solubility and stability but also provide a hydrating, non-greasy, and user-friendly matrix suitable for topical application [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Among medicinal plants,

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench has attracted particular attention due to its high content of caffeic acid derivatives, alkamides, and polysaccharides. These compounds exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and skin-repairing activities [

7,

12,

13]. Studies have also shown that

E. purpurea extracts can modulate inflammatory mediators and growth factors involved in tissue repair, supporting skin homeostasis and regeneration [

9,

14]. Despite these advantages, direct application of

E. purpurea extracts is limited by poor stability, susceptibility to oxidation, and restricted skin permeability.

Encapsulating

E. purpurea extracts within lipid nanosystems, followed by incorporation into gel matrices, represents a promising strategy to overcome these limitations. Lipid-based nanocarriers, such as liposomes, transferosomes, and SLNs, can protect the bioactive compounds from degradation, enhance their solubility, and facilitate penetration through the skin barrier [

15,

16,

17]. Transferosomes, in particular, can deform to traverse intercellular spaces of the stratum corneum, delivering active compounds to deeper skin layers. Incorporating these carriers into gel matrices provides additional advantages: gels maintain a hydrated environment that promotes skin moisture, enable controlled and sustained release of encapsulated bioactives, and can be tuned for optimal rheology, adhesion, and spreadability, improving both therapeutic outcomes and user comfort [

18,

19]. For example, Malang et al. and Sahu et al. demonstrated that nanostructured lipid carrier-based gels provided prolonged transdermal release and enhanced skin interaction for anti-inflammatory drugs, highlighting the potential of this approach for plant-derived compounds [

19,

20].

The originality of this study lies in combining the well-documented bioactivity of E. purpurea with the technological advantages of lipid nanosystems and gel carriers, producing a formulation that addresses both stability and delivery challenges. Such an approach offers potential applications in daily skincare, wound healing, and the management of oxidative or inflammatory skin conditions, bridging the gap between traditional plant-based remedies and advanced topical therapeutics. By integrating nanotechnology with natural bioactives, this research aims to develop formulations that are not only effective and safe but also practical for consumer use, highlighting a sustainable strategy for enhancing skin health.

In this study, we prepared and characterized lipid-based nanosystems incorporating E. purpurea extract and evaluated their potential for topical delivery. The extract was first charaterized in terms of polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity, then incorporated into liposomes and transferosomes, which were assessed in terms of particle size, polydispersity, entrapment efficiency, stability, and release profile. Their cytotoxicity and cytoprotective effects were tested on fibroblast cultures to confirm safety and biological activity. Based on the superior performance of liposomes, we further developed Carbopol-based gels containing these nanocarriers, alongside a comparative gel with free extract, and investigated their physicochemical stability, textural properties, antioxidant capacity, and sustained release behavior. Altogether, this integrated approach allowed us to demonstrate that nanosystem-loaded gels represent an effective and biocompatible strategy for delivering E. purpurea bioactives in dermatocosmetic applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phytochemical Characterization and Antioxidant Properties of E. purpurea Extract

The hydroalchoolic extract of

E. purpurea contained a total polyphenol content of 14.7 ± 0.03 mg GAE/g. HPLC analysis revealed chicoric and caftaric acids as the main constituents. These results highlight the extract’s strong antioxidant potential. Also, the literature reports total polyphenol content values for

E. purpurea leaf extracts, for example, 2.7 ± 0.2 mg GAE/g of dry extract [

21] or 22.3 ± 1.0 mg GAE/g of dry extract [

22]. The observed differences in polyphenol content could be explained by the fact that the plant material used in this study was collected from a different county in Romania, Europe, compared to those in other studies. Agro-climatic conditions, including altitude, rainfall, and soil composition, can influence the amount of polyphenolic compounds even within the same plant species. Similar trends have been reported for other species in several studies [

23,

24].

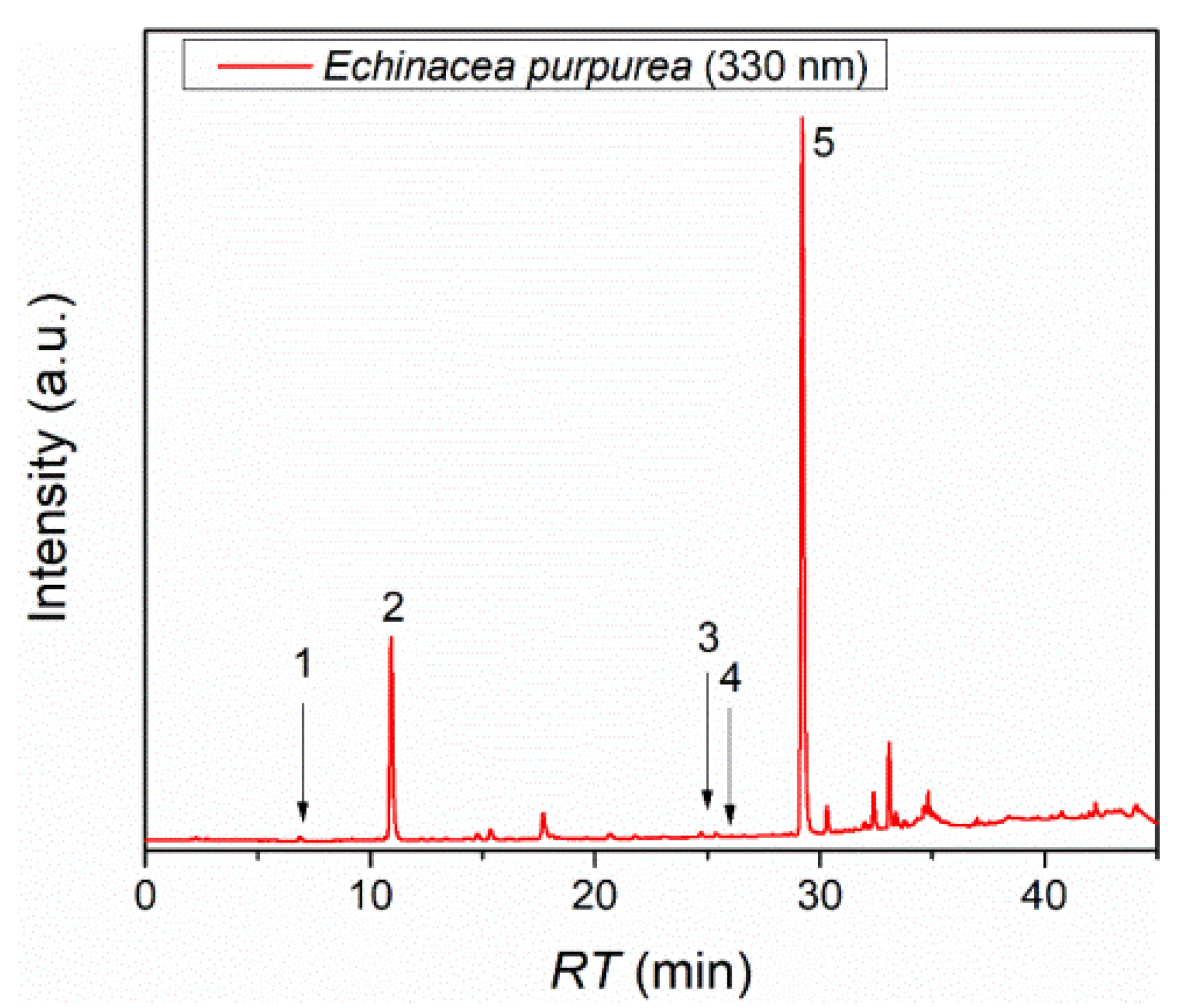

Reffering to the HPLC analysis of

E. purpurea extract, nine reference compounds (protocatechuic acid, caftaric acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, (-)-epicatechin, trans-ferulic acid, ellagic acid dihydrate, rutin hydrate, chicoric acid) were used. Five polyphenolic compounds were identified and quantified, as presented in

Table 1 and the chromatogram (

Figure 1). The predominant compounds in

E. purpurea are chicoric acid, with a concentration of 19.528 ± 0.004 mg compound/g extract, and caftaric acid, with a concentration of 15.423 ± 0.018 mg compound/g extract, both of which exhibit strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cytomodulatory, and cytostimulatory activities.

The

E. purpurea extract shows a significant ability to scavenge free radicals, with an IC₅₀ of 56.890 ± 0.056 µg/mL. This value is substantially within the range recorded for

E. purpurea extracts in the literature and shows significant antioxidant potency (lower IC₅₀ , higher activity); however, direct comparisons should take into account the plant component, solvent, extraction/standardization, and test conditions. Sudeep et al. reported a value of IC

50 ≈ 106.7 µg/mL for a standardized hydroalcoholic extract of

E. purpurea enriched to 4% chicoric acid; this is a weaker activity than ours, which is probably due to composition and extraction details [

25]. According to Russo et al., methanolic extracts of

E. purpurea exhibited IC₅₀ = 139 ± 0.9 µg/mL, which was once more weaker than our extract [

26]. However, other studies have reported values of IC

50 about 15.7 µg/mL for specific ethanolic extracts indicating a greater antioxidant activity and showing how the choice of solvent, plant part, and phenolic composition can shape the results [

27]. Our result is consistent with the range reported for other

E. purpurea preparations, where DPPH IC₅₀ values have been estimated between about 65 and 92 µg/mL [

27,

28]. Overall, our IC

50 of 56.890 µg/mL aligns with previously reported data for

E. purpurea, showing that the extract has strong antioxidant activity. The recovery of caffeic-acid derivatives (caftaric, chlorogenic, and chicoric acids) and other phenolic compounds is influenced by (i) the polarity of the extraction solvent and the optimization of extraction conditions (e.g., hydroalcoholic versus methanol, ultrasound-assisted extraction), and (ii) specific assay parameters such as DPPH concentration, incubation time, and matrix/blank corrections, all of which can affect the observed IC₅₀. These factors likely account for the variations reported across different studies [

26].

2.2. Characterisation of Lipid Nanosystems Loaded with E. purpurea

The size, polydispersity index (PDI) and entrapment efficiency (EE) of transferosomes and liposomes loaded with

E. purpurea extract, are presented in

Table 2. Empty transferosomes displayed an average particle size of 102.2 ± 1.10 nm with a PDI of 0.398 ± 0.03, while the incorporation of the extract (EP_T) led to a significant increase in particle size (156.3 ± 1.08 nm) and an improvement in homogeneity, as indicated by a lower PDI value (0.083 ± 0.02). For liposomes, the empty nanosystems exhibited an average particle size of 63.2 ± 0.44 nm and a PDI of 0.421 ± 0.02. After loading with

E. purpurea extract (EP_L), their size increased substantially to 199.1 ± 0.22 nm, while the PDI remained relatively high (0.442 ± 0.01), suggesting a broader size distribution compared with transferosomes. Empty liposomes exhibited a smaller size (63.2 ± 0.44 nm) compared to empty transferosomes (102.2 ± 1.10 nm), maybe due to the intrinsic nature of liposomes, in which bioactive molecules form structured complexes with phospholipid heads, resulting in more compact vesicular assemblies [

29]. In contrast, transferosomes, due to the presence of edge activators, form more loosely organized vesicles [

30,

31]. After loading with

E. purpurea extract, both nanosystems increased in size (to 156.3 ± 1.08 nm for EP_T and 199.1 ± 0.22 nm for EP_L), consistent with the incorporation of active compounds into the vesicles. Also, loading enhanced the uniformity of transferosomes significantly, as shown by a dramatic decrease in PDI (from 0.398 ± 0.03 to 0.083 ± 0.02), suggesting that the extract reinforces membrane cohesion and promotes uniform vesicle formation. In contrast, liposomes maintained a uniformly broad size distribution (PDI 0.421 ± 0.02– 0.442 ± 0.01) regardless of loading.

The EE for EP_T was 63.10 ± 1.03 %, suggesting a great incorporation of polyphenolic compounds within the lipid nanosystems. Liposomes achieved a higher EE (75.15 ± 1.24%) than transferosomes, confirming the strong affinity and complexation between phytochemicals and phospholipids, which promotes better entrappment [

32].

In terms of stability, the results shown in

Table 2 indicated that the lipid nanosystems containing plant extract remained stable for at least three months, with only minimal loss of phytoconstituents.

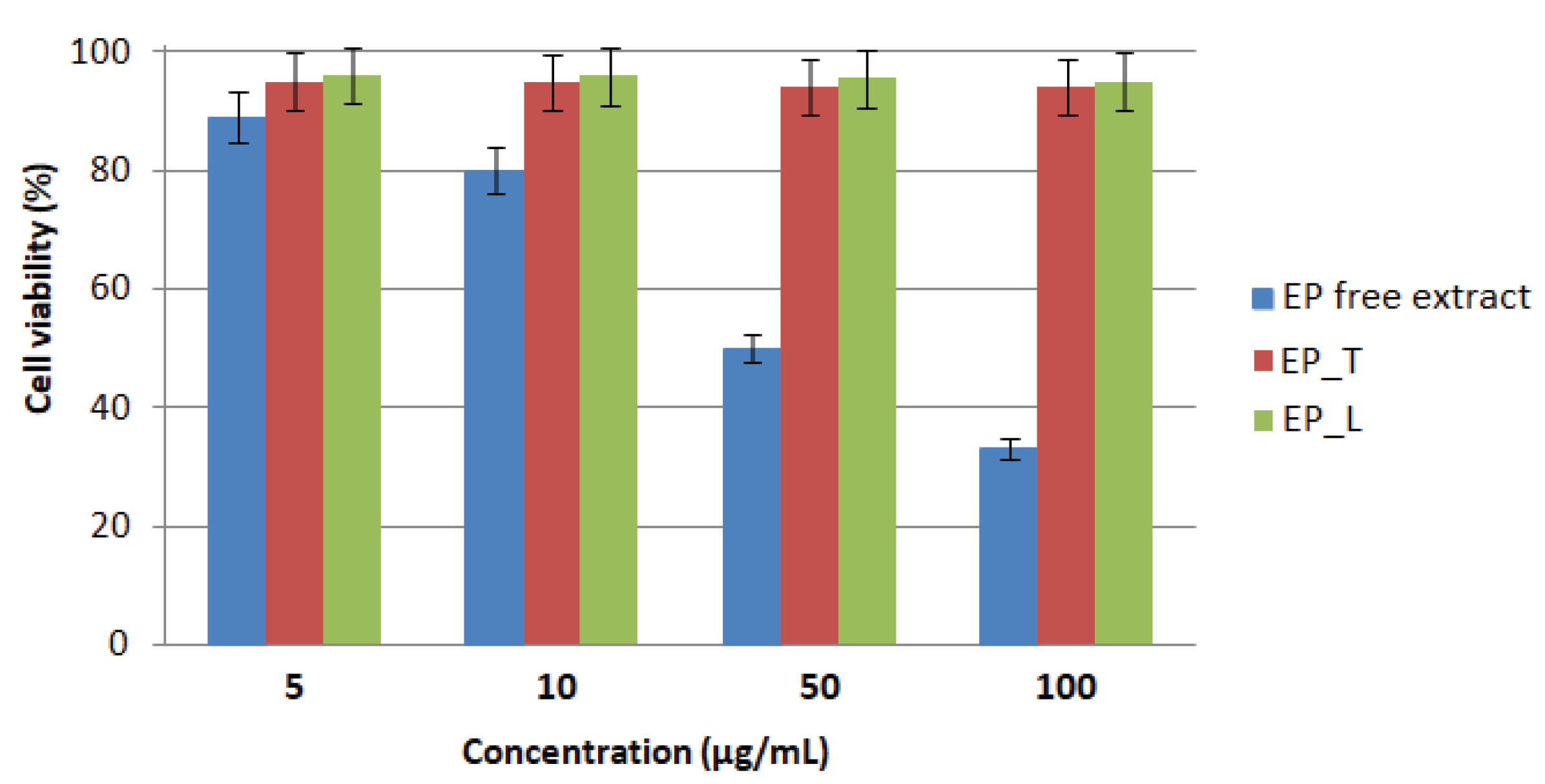

2.3. Biocompatibility of the E. purpurea Extract and Its Lipid-Based Nanosystems Evaluated by Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of

EP extract and its lipid-based nanosystems was evaluated on L-929 murine fibroblasts using the MTS assay. The free extract showed an IC

50 value of 64.12 ± 2.88 µg/mL, indicating a moderate decrease in fibroblast viability at higher concentrations (

Figure 2). At low concentrations (5–10 µg/mL), the extract maintained high cell viability, while higher doses caused a significant decline, reaching only 33% viability at 100 µg/mL, and confirming the concentration-dependent nature of the response. This finding is in line with previous studies demonstrating that polyphenol-rich

Echinacea extracts may exert dose-dependent cytostatic or cytotoxic effects, largely through redox modulation and the regulation of signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK [

33,

34]. The biocompatibility profile of the lipid nanosystems, on the other hand, was noticeably superior. Transferosomes and liposomes maintained fibroblasts viability at about 94% and 96%, respectively, over a 24-hour incubation period. This is significantly higher than the 70% criterion for non-cytotoxic materials specified by ISO 10993-5. This excellent tolerance implies that the edge activators and phospholipid bilayers used in the nanosystems are intrinsically safe and do not inhibit the proliferation of fibroblasts. Similar outcomes have been reported for various lipid vesicles filled with plant extracts, where nanocarriers enhanced the stability and prolonged release of bioactives while reducing cytotoxicity [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The encapsulation of polyphenolic compounds within the lipid bilayers is responsible for the nanosystems' improved biocompatibility when compared to the free extract. Encapsulation provides a controlled release of bioactive compounds, ensuring a consistent therapeutic effect while preventing cellular stress that could occur from sudden high local concentrations. This protective role of nanosystems has also been widely reported for other phytochemicals and is considered a major benefit for topical use [

39]. These results show that transferosomes and liposomes are safe, biocompatible carriers for

E. purpurea extract. Their ability to maintain fibroblast viability demonstrates their strong potential for use in topical gels targeting infectious skin diseases, where protecting skin cell integrity is essential for effective therapy.

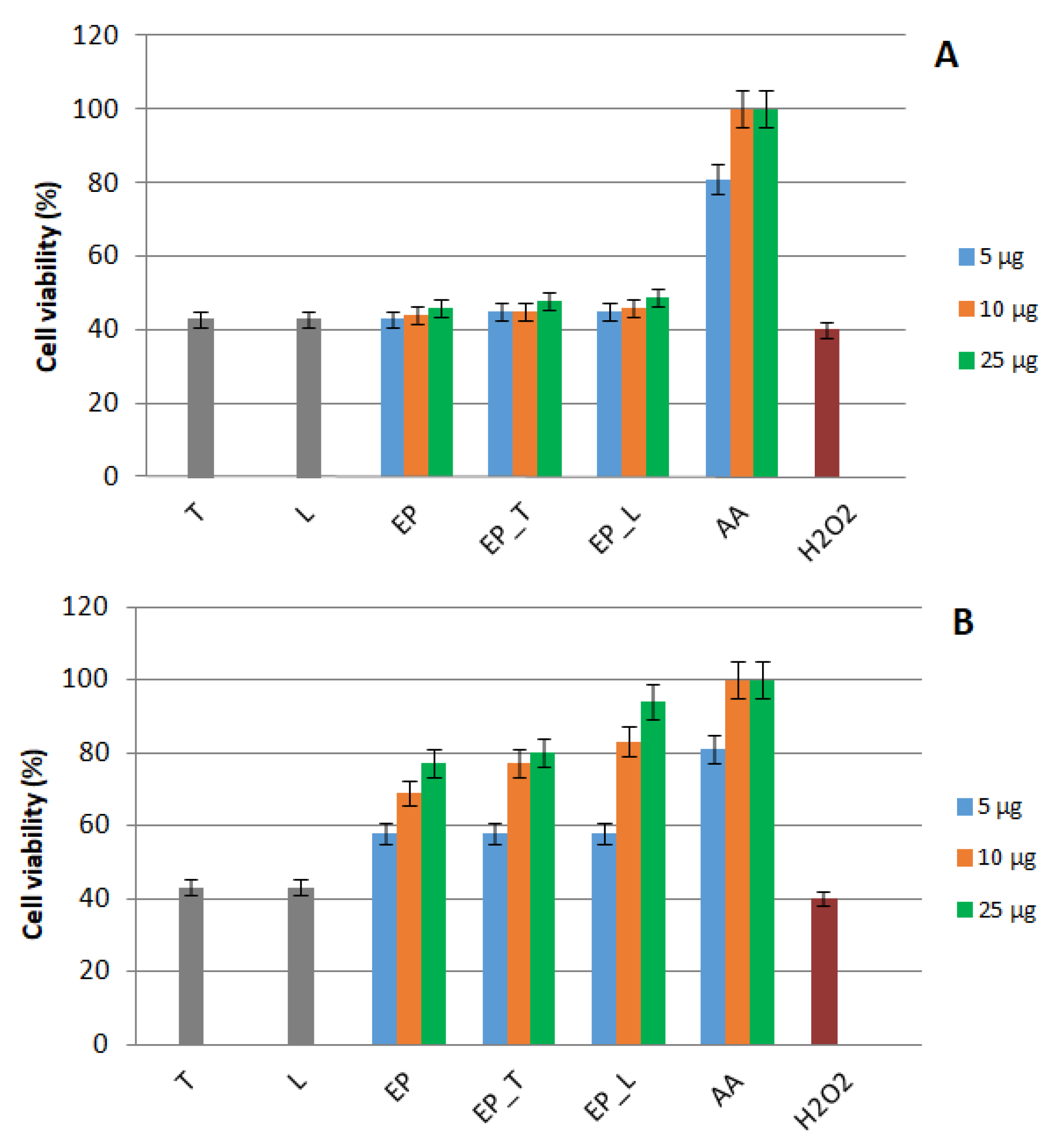

2.4. Enhanced Cytoprotection by E. purpurea Nanosystems Against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress

The cytoprotective activity of the

E. purpurea extract and its lipid formulations (transferosomes and liposomes) was evaluated in an oxidative stress model using L929 fibroblasts. Exposure to 50 mM H₂O₂ reduced fibroblast viability to ~40%, providing a reliable condition for testing protection. Cells were pretreated with the free extract or nanosystems for either 1 h or 24 h, followed by 4 h H₂O₂ exposure and viability assessment by MTS assay. Only the 24 h pretreatment significantly improved fibroblast survival, whereas 1 h exposure did not provide protection. This indicates that a longer incubation period is necessary, likely because internalization and cellular responses (e.g., antioxidant enzyme activation) are required for protection. Among the tested samples,

E. purpurea-loaded transferosomes and liposomes showed stronger protective effects than the free extract as shown in

Figure 3. This is consistent with their superior biocompatibility, as the nanosystems preserved about 94–96% cell viability over 24 h, well above the ISO 10993-5 threshold of 70% for non-cytotoxic materials [

40]. The improved performance of nanosystems can be attributed to the encapsulation of polyphenols, which enables gradual release, prevents harmful concentration spikes, and maintains a steady supply of bioactives that support antioxidant defenses and cell survival. In comparison with other plant extracts tested under similar conditions,

E. purpurea displayed a lower intrinsic antioxidant and protective activity (e.g., compared to

Lycium barbarum extract) [

41]. However, encapsulation markedly enhanced its effect, demonstrating the added value of lipid nanocarriers for extracts with moderate activity. Our findings corroborate earlier studies on lipid vesicles containing phytochemicals. For instance, nanocarriers with

Rosa canina extract, genistein or thymoquinone considerably improved cell survival while mitigating oxidative or chemical stress compared to the free compounds [

35,

36,

42]. Likewise, quercetin niosomes exhibited improved delivery and antioxidant activity on the skin [

39]. More recent reviews have noted lipid-based nanocarriers as having particular efficacy in stabilizing and extending the antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds [

38]. For Echinacea, in particular, there have been other studies that have connected its protective, and wound healing properties to the modulation of NF-κB, MAPK, TGF-β, and VEGF signaling pathways [

14]. This aligns with our observation that only long-term (24 h) pretreatment was protective, suggesting that

E. purpurea’s cytoprotective effect depends not only on direct radical scavenging but also on modulation of intracellular signaling and gene expression.

In conclusion, transferosomes and liposomes loaded with E. purpurea showed stronger cytoprotection against oxidative stress than the free extract. These nanosystems, along with their excellent safety profile, represent promising carriers for topical applications targeting infectious skin diseases, where oxidative stress is a major contributor to tissue damage and impaired healing.

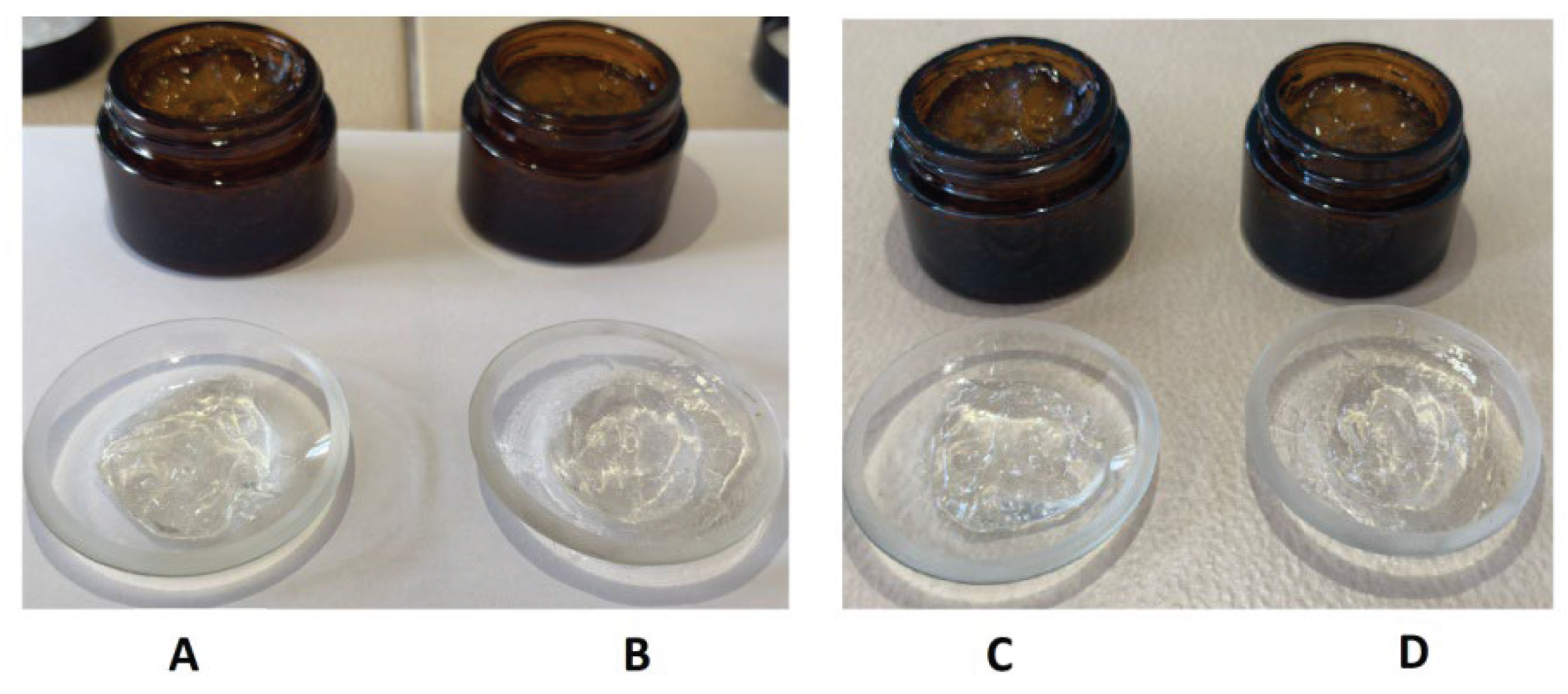

2.5. Physicochemical and Textural Stability of Gels

The components of the gel formulations were selected to provide both structural stability and functional benefits. Carbopol 940 acted as the gelling agent, creating a stable matrix suitable for topical delivery. Glycerin served as a humectant, promoting uniform mixing of the components and contributing to skin hydration. Sodium hydroxide had a dual role: inducing gelation and adjusting the pH to values compatible with skin application. Liposomes containing E. purpurea were chosen for the gel formulation because they showed better entrapment efficiency, promoted higher cell proliferation, and exhibited lower cytotoxicity than the transferosomes, thereby improving the delivery of bioactive compounds. Eucalyptus essential oil, included at a 0.1% concentration, not only imparted a refreshing aroma but also contributed functional benefits, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and soothing effects, making it a valuable component in the formulation. Vitamin E, fat soluble antioxidant, played a key role in protecting sensitive ingredients like polyphenols and essential oils from oxidative degradation during storage and use. This helps keep the formulation stable, prevents it from rancidity, and extends its overall shelf life. Additionally, vitamin E brings added benefits to the skin, thanks to its soothing, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative properties, making it a valuable ingredient for both product stability and skin health.

The physicochemical properties of gels were assessed initially (after 1 day) and following a 2-month storage period at 4

0C (

Table 3 and

Figure 4). Both formulations maintained a homogeneous, visually transparent appearance with a specific aromatic odour throughout the evaluation period. No signs of phase separation, sedimentation, or texture alteration were observed after two months, indicating excellent physical stability of both gels. The pH values of the formulations remained relatively stable over time, with only minor increases observed (

Table 3). These values fall within the skin-compatible pH range (approximately 4.5–6.0) [

43], supporting their suitability for topical application.

Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) revealed for both gels excellent textural stability, with the liposomal formulation offering initially higher elasticity and firmness, which may translate into improved application properties. Springiness and cohesiveness remained relatively stable for both formulations, with small fluctuations that do not appear to compromise product integrity.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity of Gels (DPPH Assay)

The antioxidant capacity of the gels was evaluated using the DPPH assay and quantified in terms of Trolox equivalents (TE, mM/g gel). The gel containing free extract EP exhibited a slightly higher radical scavenging activity (75.15 ± 0.15% inhibition, corresponding to 1.41 ± 0.003 mM TE/g) compared to the EP_L gel (72.69 ± 0.41% inhibition, 1.37 ± 0.008 mM TE/g). As shown in

Table 4, both formulations demonstrated good antioxidant activity and the similar values suggest that encapsulation preserved the antioxidant properties of EP, supporting the protective effect of liposomes on sensitive phytochemicals.

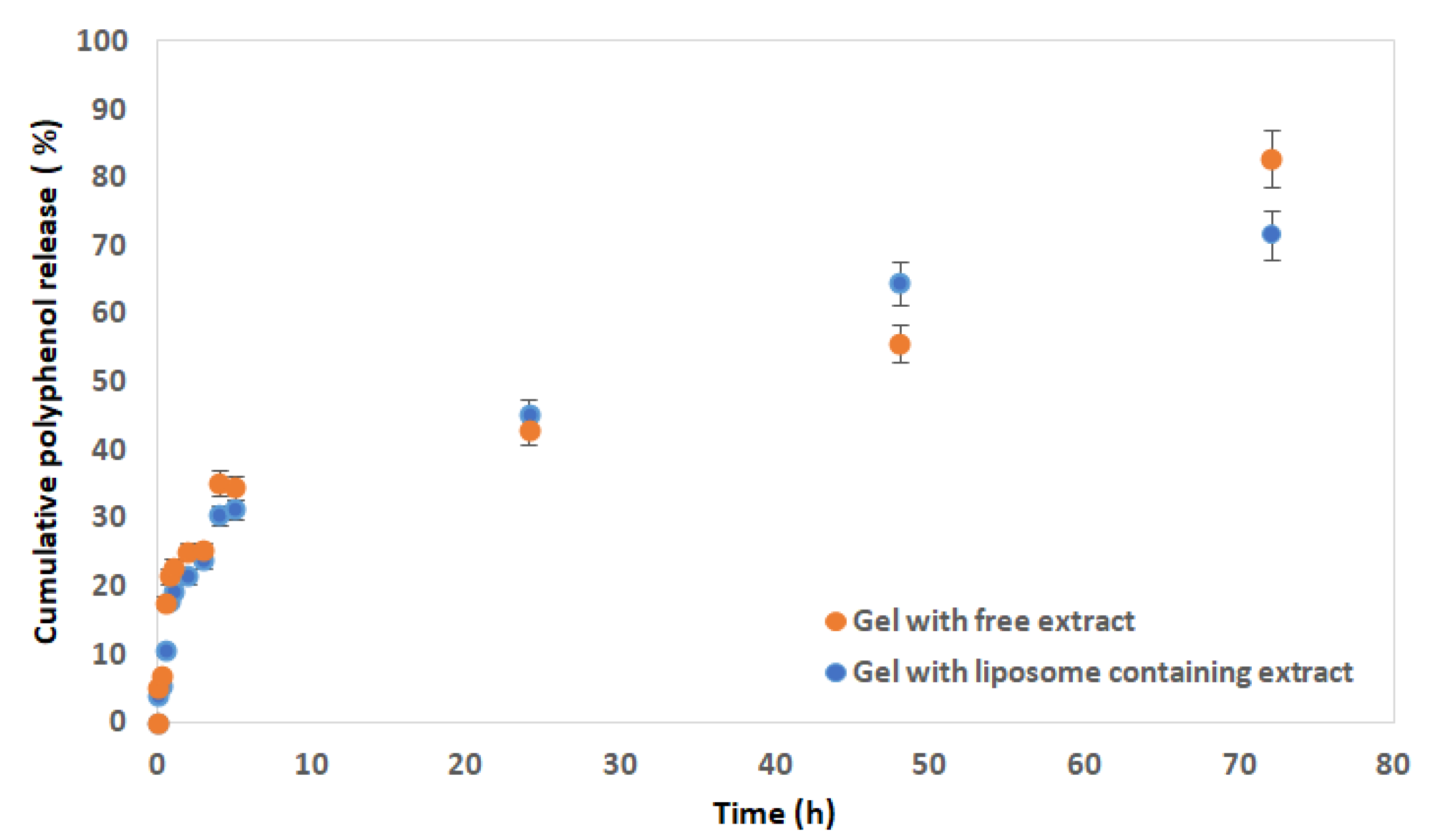

2.7. Cumulative Release and Kinetic Modeling of Polyphenols from Free and Liposome-Encapsulated E. purpurea Gels

The cumulative release profile of polyphenols from gels containing

E. purpurea showed distinct differences between formulations with free extract and those with liposome-loaded extract (

Figure 5). In the initial phase, the gel with free extract exhibited a slightly more rapid release, reaching 22.8% at 1 h compared to 19.2% from the liposomal gel. After 24 h, release from the free extract gel progressed more slowly, with 43.0% at 24 h, whereas the liposomal formulation surpassed it with 45.2%, indicating enhanced sustained release. Notably, at 48 h the liposomal gel released 64.5%, markedly higher than the 55.7% from the free extract gel, demonstrating the ability of liposomes to prolong release. However, by 72 h the free extract gel reached a higher cumulative release (82.7%) compared to 71.5% for the liposomal system, suggesting that encapsulation delays complete release but maintains more controlled kinetics over time. Overall, these results confirm that liposomal incorporation reduces the initial burst, enhances sustained release, and modifies the overall release kinetics of polyphenols from the gel matrix.

To better understand the release mechanisms of polyphenols from dermatocosmetic gels, the experimental data were subjected to kinetic modeling using several mathematical approaches, including zero-order, first-order, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull and Hixson-Crowell equations. Model fitting was carried out with the KinetDS 3 software package. Model performance was evaluated through the correlation coefficient (R²), root mean square error (RMSE), and the Akaike information criterion (AIC). An optimal model was defined as having an R² value close to 1 together with lower RMSE and AIC values. The statistical indices for each model are summarized in

Table 5.

The mathematical models equations used are:

where

Mt is the amount of polyphenols released at time t, K0 is the zero-order model constant, k is the first-order model constant, Kp is the Korsmeyer-Peppas constant, n is an exponential factor, a and b are Weibull parameters, M0 represents the total initial amount of polyphenols present in the gel before any release occurs (t = 0), KHC is the Hixson-Crowell release rate constant.

For plain gel, the Weibull model (R2= 0.919, RMSE = 6.32, AIC = 78.08) gives the best fit, closely followed by Korsmeyer-Peppas (R2 = 0.897, RMSE = 6.64, AIC = 79.24), while for liposomal gel, the Weibull model again is the best (R2 = 0.963, RMSE = 3.38, AIC = 63.04), and Korsmeyer-Peppas. Weibull fit suggests a time-dependent release with a flexible curve shape. The release exponent a around 0.44–0.49 indicates Fickian diffusion-dominated release. Korsmeyer-Peppas model shows n values of approximately 0.36 (Gel with EP) and 0.42 (Gel with EP_L), which are consistent with diffusion-controlled drug release.

Both formulations follow diffusion-controlled release, best described by the Weibull model. Incorporating liposomes significantly improves control and predictability of E. purpurea release, likely due to their ability to modulate drug diffusion and retention in the gel.

3. Conclusions

This study shows that topical gels incorporating lipid nanosystems extract can be considered promising candidates for the dermal delivery of Echinacea purpurea extract. Both transferosomes and liposomes demonstrated successful entrappment of the bioactive compounds, with liposomes offering higher entrapment efficiency, while transferosomes exhibited superior size uniformity. These complementary properties underscore their suitability as delivery platforms, allowing for strategic selection based on specific therapeutic goals. The gel formulations showed excellent physical, chemical, and textural stability over a two-month period. Notably, the incorporation of Echinacea purpurea in liposomes enhanced the gel’s elasticity and firmness, attributes that may improve user experience through better skin feel and spreadability. The antioxidant activity of the incorporated Echinacea purpurea remained comparable to that of the free extract, affirming the protective role of the lipid carriers in preserving bioactivity. In vitro release studies confirmed that both systems follow a diffusion-controlled release pattern, best described by the Weibull model. The presence of liposomes contributed to a more controlled and predictable release profile, likely improving skin retention and therapeutic efficacy. In conclusion, these results highlight the potential of nanosystem-based topical gels as innovative and effective solutions for modern skincare. However, in vivo and clinical studies—along with scale-up research—are needed to fully confirm their therapeutic potential and practical use in commercial skincare products.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Standard phenolic compounds used for identification and quantification in Echinacea purpurea extract included: protocatechuic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, TCI, Japan >98%), caftaric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany, ≥ 98%), vanillic acid (TCI, >98%, GC-grade), syringic acid (Molekula GmbH, Munich, Germany, >98.5%), (–)-epicatechin (TCI, >98%), trans-ferulic acid (TCI, >98%), ellagic acid dehydrate (TCI, >98%), rutin hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, 95%), and cichoric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 95%). The mobile phases and sample preparations used acetonitrile (Riedel-de Haën, Honeywell, Seelze, Germany), ethanol (Riedel-de Haën), and formic acid (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany), along with ultrapure water obtained from a Millipore Direct-Q3UV system (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with a Biopack UF cartridge.

For the obtaining of lipid nanosystems loaded with Echinacea purpurea extract, phosphatidylcholine (from egg yolk, Sigma-Aldrich), and sodium cholate (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Organic solvents, methanol and ethanol, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich.

For the preparation of the gel formulations, Carbopol 940, glycerin, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, vitamin E (α-tocopherol) from TCI, and Eucalyptus essential oil from Fares, Romania.

The antioxidant activity was assessed through the DPPH assay, using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (TCI) prepared in methanol.

For cytotoxicity and cytoprotective assays were used: murine fibroblast cell line (L-929) obtained from ATCC®CRL-6364™ (Manassas, Virginia, US), penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin solution (PSN), trypsin-ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic-acid (EDTA) solution, Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM), hydrogen peroxide 30% (w/w) (H2O2), L-ascorbic acid, fetal bovine serum (FBS) – all acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). CellTiter96®aqueous non-radioactive cell proliferation assay was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

4.2. Plant material

E. purpurea leaves were harvested at maturity from Dâmbovița County, Romania (latitude: 45° 18’15.4’’ N, longitude: 25°23’28.4’’ E) and identified by the Extractive Biotechnologies team of the National Institute for Chemical-Pharmaceutical Research and Development – ICCF, Bucharest, Romania.

E. purpurea leaves were selected as plant material based on its bioactive phytoconstituents, including polyphenolic compounds, whose cell-protective property against reactive oxygen species has been demonstrated. The extraction technique using 50% ethanol (v/v) as the solvent to optimize polyphenol recovery was previously described in our earlier publication [

44]. The resulting extract was concentrated and standardized based on its total polyphenol content, expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

4.3. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

This analysis was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Shimadzu Nexera 2) equipped with a photodiode array detector (SPD-M30A) operating over a wavelength range of 250–650 nm, a quaternary pump LC-20ADXR, a vacuum degasser DGU-20A5R, an autosampler SIL-30AC, and a column oven CTO-20AC. Chromatograms were processed using LabSolutions software. Separation was achieved via gradient elution on a Nucleoshell® C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 × 100 mm, 2.7 µm) using two mobile phases: 2.5% aqueous formic acid (mobile phase A) and 90% aqueous acetonitrile with 2.5% formic acid (mobile phase B). The elution program was adapted from Nicoletti et al. [

45]: an isocratic elution for 1.5 min with 5% mobile phase B, followed by a 6 min linear gradient to 9% B and another 6 min linear gradient to 13.5% B, then an isocratic elution at 13.5% B for 2.5 min, a 5 min linear gradient to 18.5% B, followed by a 1 min linear gradient to 22.5% B, isocratic elution at 22.5% B for 3.5 min, a 4.5 min linear gradient to 35% B, a 5 min linear gradient to 100% B, and isocratic elution for 5 min with 100% B. Finally, the gradient was returned to the initial concentration, and the column was equilibrated for 10 min before the next injection. The flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min, separation was carried out at 20 °C, and the injection volume was 1 µL. All solvents used for the mobile phases were previously filtered through 0.45 µm nylon membranes. The chromatogram of

E. purpurea extract was recorded at 330 nm. Polyphenolic compounds were identified by comparing retention times and the similarity of UV–Vis spectra with those of standard substances. Each HPLC standard was dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 100 mg/L, and calibration curves for quantifying the phenolic compounds were obtained by injecting five solutions with concentrations ranging from 0.5–100 mg/L for each standard.

4.4. Total Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Activity of E. purpurea Extract

The total polyphenol amount of

E. purpurea extract was measured using the method of Folin-Ciocalteu [

46]. The concentration of total polyphenolic compounds was quantified using a gallic acid standard curve (concentration range: 0.01–0.1 mg/mL; calibration equation: y = 0.01332x + 0.0262; R² = 0.99584). Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g).

Antioxidant activity was evaluated using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay. 50 µL of extract was mixed with a 2950 µL DPPH methanolic solution (0.025 g/L) and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 517nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Jasco V-630, Portland, Oregon, USA). The antioxidant activity was calculated as the percentage of DPPH radical inhibition. As positive controls, quercetin (0.0001–1 mg/mL) and caffeic acid (0.0001–1 mg/mL) were used. Five replicates were carried out in the experiments to evaluate the antioxidant activity.

4.5. Preparation of Lipid Nanosystems Loaded with E. purpurea Extract

The lipid nanosystems containing

E. purpurea extract were prepared following the method described by Pavaloiu et al. [

44], which is based on thin-film hydration combined with sonication and extrusion. For the present work, this protocol was slightly modified, mainly by adjusting the concentrations of phosphatidylcholine and sodium cholate, and other formulation parameters, in order to obtain the nanosystems investigated here. Briefly, a standardized quantity of plant extract (25 mg) was added to the lipid phase, which was created by dissolving phosphatidylcholine (100 mg) in ethanol (10 mL), for obtaining liposomes, and phosphatidylcholine and sodium cholate (10:2, w/w) in ethanol (10 mL) for obtaining transferosomes. To promote phospholipid swelling and guarantee consistent extract inclusion, the mixture was kept at room temperature. A thin, uniform lipid film was obtained by removing the organic solvent at 35 °C under decreased pressure using a rotary evaporator (Laboranta 4000, Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Kelheim, Germany). To help stabilize the vesicles, these films was hydrated with bidistilled water at a temperature higher than the lipid phase-transition point (35 °C). The resultant suspensions were then maintained at 25 °C for two hours. The lipid suspensions were put through to sonication for 20 minutes at 50% amplitude (Sonorex-Digital-10P, Bandelin-Electronic, Berlin, Germany) in order to decrease the size of the vesicles and achieve a uniform dispersion. This was followed by seven separate extrusions through polycarbonate membranes with pore sizes of 0.4 µm and 0.2 µm. Centrifugation was used to separate the resulting lipid nanosystems from the unentrapped extract for 20 minutes at 12,000 rpm and 5 °C. Distilled water was used to properly redistribute the pellet that contained the encapsulated vesicles. The formulations were prepared in triplicate and stored at 4 °C until further analysis.

4.6. Characterization of Lipid Nanosystems Loaded with E. purpurea Extract

Particle size, PDI, EE, and release profile were used to describe the nanosystems. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to measure particle size and PDI. To minimize multiple scattering effects, the lipid suspensions were diluted with distilled water at a 1:10 ratio. EE was determined as a ratio between the encapsulated polyphenols in the lipid nanosystem and the initial amount of extract added. The total polyphenol content encapsulated in the lipid nanosystems was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, following the procedure reported in the literature [

41]. The stability of the lipid nanosystems loaded with

E. purpurea was evaluated by monitoring their characteristics over time (3 months of storage at 4 °C).

4.7. In vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

The MTS test was used to assess the cytotoxicity of both free plant extract and its corresponding vesicular formulation on murine fibroblast L929 cells. L-929 fibroblasts were cultured in 25 cm² flasks in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PSN. At approximately 75% confluence (~48 h), cells were detached with trypsin-EDTA, neutralized with fetal bovine serum, pelleted by centrifugation (1200 rpm, 10 min), and resuspended in culture medium at 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 7,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Cells were exposed to different concentrations of samples (5, 10, 50, and 100 µg/mL) for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Cells incubated only with medium were used as a negative control. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS, Promega, USA). After washing twice with serum-free EMEM, 100 µL of MTS reagent (1:10 in medium) was added per well, and plates were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Chameleon V, LKB Instruments). Viability was expressed as a percentage of untreated controls (100% viability). All samples were sterilized by exposure to ultraviolet light for three hours. The cytotoxicity assay was carried out in triplicate.

4.8. Evaluation of Cytoprotective Effect Under Oxidative Stress

The cytoprotective effect of the samples was evaluated using an in vitro oxidative stress challenge model in L-929 fibroblast cultures, with cell viability (MTS assay) as the endpoint. This cell line was selected considering the intended topical application of the final products. The tested samples were: lipid nanosystems without extract, free extract, lipid nanosystems loaded with E. purpurea.

Determination of the H₂O₂ Concentration Reducing Cell Viability

L-929 fibroblasts were cultured in EMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 10⁵ cells/mL. Exposure was carried out at a minimum confluence of about 80%, in medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum for 12 h. Untreated cells serve as control. Cell viability was measured using the MTS assay. The concentrations of H₂O₂ tested were 1, 10, 20, 50, and 100 mM.

Evaluation of the Antioxidant Effect of Extract and Extract-Loaded Lipid Nanosystems

Cells were pre-incubated for 1 or 24 h before the oxidative challenge with different concentrations (5, 10 and 25 µg/mL) of the test samples (free extract, empty transferosomes, empty liposomes, transferosomes loaded with extract, liposomes loaded with extract). Oxidative stress was induced by exposure to 50 mM H₂O₂ for 4 h. After treatment, cell viability was determined using the MTS assay. Controls included untreated cells and cells exposed only to H₂O₂. Cells incubated with ascorbic acid with the same concentrations as test samples were used as positive control. All the samples used in these tests were treated to UV light for three hours for sterilization. Oxidative stress induction assay was conducted in triplicate.

4.9. Preparation and Characterization of Gels Containing Liposomes Loaded with E. purpurea

4.9.1. Formulation of Gels with Liposomes Loaded with E. purpurea

Two gel formulations were prepared to enable a comparative evaluation of the release profile of

E. purpurea extract: one gel containing the free hydroalcoholic extract, and a second gel incorporating liposomes loaded with the same extract (

Table 6). The gel was prepared by first allowing the Carbopol to fully hydrate in distilled water for 24 hours. Glycerin was then added, and gelation was induced by the gradual addition of 5% sodium hydroxide solution under constant stirring, until a homogeneous gel was obtained. Eucalyptus essential oil (

Eucalyptus globulus L.) and liposomes loaded with

E. purpurea extract were incorporated afterward, with gentle and continuous mixing. Vitamin E (α-tocopherol acetate) was also added. We used 1.5% hydroalcoholic extract in the conventional gel and 2% liposomes in the liposomal gel to make sure both formulations contained the same amount of

E. purpurea extract, allowing for a direct and meaningful comparison of their release profiles.

4.9.2. Characterization of Gels with Liposomes Loaded with E. purpurea

Gel formulations were first visually evaluated by placing a small amount on a glass slide and examining it under a 4.5x magnifying lens to assess texture, color uniformity, homogeneity, and fragrance.

The pH of the gels were determined using a calibrated digital pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) after thorough homogenization. Measurements were taken once the reading stabilized for 30 seconds, with three readings recorded at different locations; if differences exceeded ± 0.2 units, the measurement was repeated to ensure accuracy.

Texture profiling of the gel was performed using a TX-700 texture analyzer (Lamy Rheology, Champagne-au-Mont-d’Or, France) equipped with a 10 kg force sensor. A two-cycle compression test, simulating product application, was conducted to evaluate firmness (maximum force for initial deformation), cohesiveness (ratio of energy between successive compressions, reflecting structural integrity), and springiness (ability to regain shape after compression). For each test, 40 g of gel was placed in cylindrical containers with leveled surfaces, and a hemispherical probe was used. Compression speed was set at 0.8 mm/s, deformation depth at 10 mm, trigger force at 5 g (0.05 N), with a 5-second interval between cycles. All measurements were conducted at ambient temperature, and each formulation was tested in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

The stability of the gels was evaluated over a 60-day period, during which samples were stored in amber glass containers at 4°C. After this period, assessments of visual appearance, pH, and fragrance were conducted to identify any indications of degradation or instability.

4.9.3. Free Radical Scavenging Capacity of Gels

The free radical scavenging capacity of the gels was assessed using the DPPH assay to confirm that the bioactive compounds remained intact after formulation. About 1 gram of each gel was mixed with 10 mL of ethanol to extract the active ingredients. The mixture was vigorously vortexed for 5 minutes, followed by sonication for 20 minutes and double filtration. Then, 0.6 mL of the filtered extract was added to 2.4 mL of a 0.025 g/L DPPH ethanol solution. The samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. The scavenging effect on DPPH radicals was quantified by monitoring absorbance changes at 517 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Jasco V-630, Portland, OR, USA). The results were expressed as %Inhibition (Mean ± SD) and Trolox Equivalent (mM/g) ± SD) using Trolox calibration curve (y = 51.705x + 1.670; R2 = 0.9985).

4.10. In Vitro Evaluation of Polyphenol Release from Lipid Nanosystems-Loaded Dermatocosmetic Gel

The release behavior of polyphenols from the dermatocosmetic gel containing liposome loaded with E. purpurea was studied using a Franz diffusion cell apparatus. 0.5 g of gel was placed in the donor compartment, while the receptor compartment was filled with 100 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) to mimic physiological conditions. The system was maintained at 32°C to simulate skin temperature, with continuous stirring at 100 rpm to ensure uniform mixing in the receptor phase.

Samples of 1 mL were withdrawn from the receptor medium at predetermined intervals—5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes and 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours—and immediately replaced with fresh PBS to maintain sink conditions. Polyphenol concentrations in each sample were measured using UV–Vis spectrophotometry. This approach enabled tracking the cumulative release of polyphenols over time, providing insight into the sustained release potential of the liposome gel compared to the gel containing free extract.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.P. and F.S.; methodology, R.D.P., F.S., C.B., M.D. and G.N.; software, R.D.P. and A.L.P.; validation, R.D.P., F.S., G.N., A.A., M.D., C.B. and A.L.P.; formal analysis, R.D.P. and F.S.; investigation, R.D.P., F.S., G.N., A.A., M.D., C.B. and A.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.P., F.S., G.N., A.A., M.D., C.B. and A.L.P.; writing—review and editing, R.D.P. and F.S.; visualization, R.D.P. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CCCDI - UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P7-7.1-PTE-2024-0317, within PNCDI IV.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CCCDI - UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P7-7.1-PTE-2024-0317, within PNCDI IV.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hwang, B.K.; Lee, S.; Myoung, J.; Hwang, S.J.; Lim, J.M.; Jeong, E.T.; Park, S.G.; Youn, S.H. Effect of the skincare product on facial skin microbial structure and biophysical parameters: A pilot study. Microbiol. Open 2021, 10, e1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranduca, M.A.; Hurjui, L.; Branisteanu, D.C.; Serban, D.N.; Branisteanu, D.E.; Dima, N.; Serban, I.L. Skin – a vast organ with immunological function (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, K.; Fields, K.; Majewski, G.; Falla, T. Skincare Bootcamp: The evolving role of skincare. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant-derived antioxidants: Significance in skin health and the ageing process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivero-Verbel, J.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Caballero-Gallardo, K. Aromatic plants as cosmeceuticals: Benefits and applications for skin health. Planta 2024, 260, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarek, P.; Kowalczyk, T.; Wieczfinska, J.; Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Górski, K.; Śliwiński, T.; Skała, E. Plant extracts as a natural source of bioactive compounds and potential remedy for the treatment of certain skin diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 2859–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadvaja, N.; Gautam, S.; Singh, H. Natural polyphenols: A promising bioactive compounds for skin care and cosmetics. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sguizzato, M.; Cortesi, R. Liposomal and ethosomal gels: From design to application. Gels 2023, 9, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, E.; Nastruzzi, C.; Sguizzato, M.; Cortesi, R. Nanomedicines to treat skin pathologies with natural molecules. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 2323–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanov, S.R.; Andonova, V.Y. Lipid nanoparticulate drug delivery systems: Recent advances in the treatment of skin disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, V.H.S.; Delello Di Filippo, L.; Duarte, J.L.; Spósito, L.; Camargo, B.A.F.; da Silva, P.B.; Chorilli, M. Exploiting solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for drug delivery against cutaneous fungal infections. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağci, E.; Ercisli, S.; Karaoğlu, Ş.A.; Duralija, B.; Jurišić Grubešić, R.; Alibabić, V. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of essential oils from Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 2745–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, P.; Hrabal, R.; Ebringerová, A.; Hříbalová, V.; Paulsen, B.S. Polysaccharides from Echinacea purpurea cell cultures and their immunomodulatory properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 310, 120654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.-R.; Lin, C.-N.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chou, C.-J. Wound healing activity of Echinacea purpurea ethanol extract via modulation of TGF-β/VEGF/NF-κB signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 315, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: Applications, advantages and disadvantages. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, I.; Yasir, M.; Verma, M.; Singh, A.P. Nanostructured lipid carriers: A groundbreaking approach for transdermal drug delivery. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 10, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isopencu, G.O.; Covaliu-Mierlă, C.-I.; Deleanu, I.-M. From plants to wound dressing and transdermal delivery of bioactive compounds. Plants 2023, 12, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Fonseca, L.P.; de Barros, D.P.C. Dermal delivery of lipid nanoparticles: Effects on skin and assessment of absorption and safety. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1357, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malang, S.D.; Shambhavi; Sahu, A.N. Transethosomal gel for enhancing transdermal delivery of natural therapeutics. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 1801–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.N.; Mohapatra, D.; Acharya, P.C. Nanovesicular ultraflexible invasomes and invasomal gel for transdermal delivery of phytopharmaceuticals. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pașca, C.; Mărghitaș, L. Al.; Bobiș, O.; Dezmirean, D. S.; Mărgaoăn, R.; Mureșan, C. Total content of polyphenols and antioxidant activity of different melliferous plants. Bul. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca, Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 73 (1). [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-T.; Huang, C.-C.; Shieh, X.-H.; Chen, C.-L.; Chen, L.-J.; Yu, B. Flavonoid, Phenol and Polysaccharide Contents of Echinacea purpurea L. and Its Immunostimulant Capacity In Vitro. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2010, 1, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, M.H.; Tyler, H.L.; Chandra, S.; Moraes, R.M.; Jackson, C.R.; Pugh, N.D.; Pasco, D.S. Plant Microbiome-Dependent Immune Enhancing Action of Echinacea purpurea Is Enhanced by Soil Organic Matter Content. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, C.A.; Dziadek, K.; Sadowska, U.; Skoczylas, J.; Kopeć, A. Analytical Assessment of the Antioxidant Properties of the Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L. Moench) Grown with Various Mulch Materials. Molecules 2024, 29, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudeep, H.V.; Gouthamchandra, K.; Ramanaiah, I.; Raj, A.; Naveen, P.; Shyamprasad, K. A Standardized Extract of Echinacea purpurea Containing Higher Chicoric Acid Content Enhances Immune Function in Murine Macrophages and Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression Mice. Pharm. Biol. 2023, 61, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Lela, L.; Benedetto, N.; Faraone, I.; Paternoster, G.; Valentão, P.; Milella, L.; Carmosino, M. Phytochemical Composition and Wound Healing Properties of Echinacea angustifolia DC. Root Hydroalcoholic Extract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić, H.; Habeš, S.; Aldžić, A.; Durgo, K.; Kosalec, I. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Activities of Phenolic Compounds of the Extracts of Echinacea purpurea (L.). Bull. Chem. Technol. Bosnia Herzegovina 2015, 44, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, P.F.; Assa, T.I.Y.; Nora, A.; Wisastra, R. Evaluating the Antioxidant Activity of Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench Ethanol Extract. Indones. J. Biotechnol. Biodivers. 2022, 6, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, J.J.; Bhusnure, O.G.; Jagtap, S.R.; Gholve, S.B.; Wale, R.R. Liposomes: A Novel Drug Delivery for Herbal Extracts. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharoo, N.; Mohd, H.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Transferosomes as a transdermal drug delivery system: Dermal kinetics and recent developments. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 16, e1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Alim, S. H.; Kassem, A. A.; Basha, M.; Salama, A. Comparative Study of Liposomes, Ethosomes and Transfersomes as Carriers for Enhancing the Transdermal Delivery of Diflunisal: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 563, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Qiu, Q.; Luo, X.; Liu, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Lin, X.; Deng, Y.; Song, Y. Phyto-phospholipid complexes (liposomes): A novel strategy to improve the bioavailability of active constituents. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 14, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Shao, C.; Geng, P.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J. Polyphenols targeting NF-κB pathway in neurological disorders: What we know so far? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1332–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, P.; Paulovičová, E.; Paulovičová, L. Effectivity of polyphenolic polysaccharide-proteins isolated from medicinal plants as potential cellular immune response modulators. Biologia (Bratislava) 2022, 77, 3581–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallustio, V.; Chiocchio, I.; Mandrone, M.; Cirrincione, M.; Protti, M.; Farruggia, G.; Abruzzo, A.; Luppi, B.; Bigucci, F.; Mercolini, L.; Poli, F.; Cerchiara, T. Extraction, encapsulation into lipid vesicular systems, and biological activity of Rosa canina L. bioactive compounds for dermocosmetic use. Molecules 2022, 27, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motawea, A.; Maria, S.N.; Maria, D.N.; Jablonski, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.M. Genistein transfersome-embedded topical delivery system for skin melanoma treatment: In vitro and ex vivo evaluations. Drug Deliv. 2024, 31, 2372277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd, H.; Dopierała, K.; Zidar, A.; Virani, A.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Effect of edge activator combinations in transethosomal formulations for skin delivery of thymoquinone via Langmuir technique. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeva-Grigorova, S.; Ivanova, N.; Sotirova, Y.; Radeva-Ilieva, M.; Hvarchanova, N.; Georgiev, K. Lipid-based nanotechnologies for delivery of green tea catechins: Advances, challenges, and therapeutic potential. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ye, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Long, X. Niosomal nanocarriers for enhanced skin delivery of quercetin with functions of anti-tyrosinase and antioxidant. Molecules 2019, 24, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 10993-5:2009—Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Păvăloiu, R.-D.; Sha’at, F.; Neagu, G.; Deaconu, M.; Bubueanu, C.; Albulescu, A.; Sha’at, M.; Hlevca, C. Encapsulation of polyphenols from Lycium barbarum leaves into liposomes as a strategy to improve their delivery. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, E.A.; Hamza, G.; El-Shafai, N.M.; Ghanem, N.F.; Mahmoud, S.; Sayed, S.M.; Alshehri, M.A.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Ghamry, H.I.; Mahfouz, M.E.; Shukry, M. Thymoquinone-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Combat Testicular Aging and Oxidative Stress Through SIRT1/FOXO3a Activation: An In Vivo and In Vitro Study. Pharmaceutics. 2025, 17(2), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, M. Towards Optimal pH of the Skin and Topical Formulations. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păvăloiu, R.D.; Sha’at, F.; Bubueanu, C.; Neagu, G.; Albulescu, A.; Hlevca, C.; Nechifor, G. Release of polyphenols from liposomes loaded with Echinacea purpurea. Rev. Chim. (Bucharest) 2018, 69, No. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, I.; Bello, C.; De Rosii, A.; Corradini, D. Identification and quatification of phenolic compounds in grapes by HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS on a semimicro separation scale. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 8801–8808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Chromatogram of the E. purpurea extract at 330 nm.

Figure 1.

Chromatogram of the E. purpurea extract at 330 nm.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity profiles of E. purpurea extract and its lipid nanosystems (EP_T – transferosomes loaded with E. purpurea, EP_L – liposomes loaded with E. purpurea).

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity profiles of E. purpurea extract and its lipid nanosystems (EP_T – transferosomes loaded with E. purpurea, EP_L – liposomes loaded with E. purpurea).

Figure 3.

Comparative effect of the free extract and its lipid nanosystems on L-929 cells - pretreatment for 1 h (A) or 24 h (B) followed by H₂O2 exposure. T- empty transferosomes, L – empty liposomes, EP – E. purpurea free extract, EP_T – transferosomes loaded with E. purpurea, EP_L - liposomes loaded with E. purpurea, AA – ascorbic acid.

Figure 3.

Comparative effect of the free extract and its lipid nanosystems on L-929 cells - pretreatment for 1 h (A) or 24 h (B) followed by H₂O2 exposure. T- empty transferosomes, L – empty liposomes, EP – E. purpurea free extract, EP_T – transferosomes loaded with E. purpurea, EP_L - liposomes loaded with E. purpurea, AA – ascorbic acid.

Figure 4.

Visual comparison of gel formulations containing E. purpurea extract: freshly prepared - (A) Gel_EP, (B) Gel_EP_L versus after 2 months at 40C - (C) Gel_EP, (D) Gel_EP_L).

Figure 4.

Visual comparison of gel formulations containing E. purpurea extract: freshly prepared - (A) Gel_EP, (B) Gel_EP_L versus after 2 months at 40C - (C) Gel_EP, (D) Gel_EP_L).

Figure 5.

Cumulative release profiles of polyphenols from E. purpurea gels: comparison between free extract and liposome-encapsulated formulations over 72 h.

Figure 5.

Cumulative release profiles of polyphenols from E. purpurea gels: comparison between free extract and liposome-encapsulated formulations over 72 h.

Table 1.

Retention times and concentrations of the compounds identified in the E. purpurea extract.

Table 1.

Retention times and concentrations of the compounds identified in the E. purpurea extract.

| Compound |

Retention time (min) |

Concentration (mgcompound/gextract) |

| Protocatechuic acid |

7.013 ± 0.001 |

0.022 ± 0.005 |

| Caftaric acid |

10.937 ± 0.002 |

15.423 ± 0.018 |

| Trans-ferulic acid |

24.992 ± 0.001 |

0.099 ± 0.002 |

| Rutin hydrate |

26.007 ± 0.001 |

0.313 ± 0.001 |

| Chicoric acid |

29.215 ± 0.004 |

19.528 ± 0.004 |

Table 2.

Physicochemical parameters of transferosomes and liposomes.

Table 2.

Physicochemical parameters of transferosomes and liposomes.

| Sample |

Particle size (nm) |

PDI |

EE (%) |

| Empty transferosomes |

102.2 ± 1.10 |

0.398 ± 0.03 |

- |

| EP_T |

156.3 ± 1.08 |

0.083 ± 0.02 |

63.10 ± 1.03 |

| Empty liposomes |

63.2 ± 0.44 |

0.421 ± 0.02 |

- |

| EP_L |

199.1 ± 0.22 |

0.442 ± 0.01 |

75.15 ± 1.24 |

Table 3.

Features of gels containing liposomes loaded with E. purpurea (EP) and free extract.

Table 3.

Features of gels containing liposomes loaded with E. purpurea (EP) and free extract.

| Features |

Gel with EP |

Gel with EP_L |

| Features after 1 day |

| Organoleptic evaluation |

Homogeneous, visually transparent, aromatic odour |

Homogeneous, visually transparent, aromatic odour |

| pH |

5.15 ± 0.11 |

5.17 ± 0.10 |

| TPA profile |

Firmness (hardness): 0.427 ± 0.017 N

Cohesiveness: 0.587 ± 0.011

Springiness: 0.741 ± 0.024 |

Firmness (hardness): 0.503 ± 0.011 N

Cohesiveness: 0.597 ± 0.015

Springiness: 0.852 ± 0.021 |

| Features after 2 months |

| Organoleptic evaluation |

Homogeneous, visually transparent, aromatic odour

No evidence of phase separation, sediment formation, or changes in texture was observed |

Homogeneous, visually transparent, aromatic odour

No evidence of phase separation, sediment formation, or changes in texture was observed |

| pH |

5.25 ± 0.02 |

5.28 ± 0.03 |

| TPA profile |

Firmness (hardness): 0.540 ± 0.011 N

Cohesiveness: 0.614 ± 0.012

Springiness: 0.869 ± 0.024 |

Firmness (hardness): 0.495 ± 0.013 N

Cohesiveness: 0.603 ± 0.015

Springiness: 0.799 ± 0.022 |

Table 4.

Antioxidant activity of gels containing free extract (EP) and liposomes loaded with EP (EP_L).

Table 4.

Antioxidant activity of gels containing free extract (EP) and liposomes loaded with EP (EP_L).

| Sample code |

%Inhibition (Mean ± SD) |

Trolox Eq. (mM/g) ± SD |

| Gel with EP |

75.15 ± 0.15% |

1.41 ± 0.003 |

| Gel with EP_L |

72.69 ± 0.41% |

1.37 ± 0.008 |

Table 5.

Kinetic modeling parameters for polyphenol release from gels, including R², RMSE, and AIC values for zero-order, first-order, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, and Hixson-Crowell models.

Table 5.

Kinetic modeling parameters for polyphenol release from gels, including R², RMSE, and AIC values for zero-order, first-order, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, and Hixson-Crowell models.

| |

Gel with EP |

Gel with EP_L |

| Model |

R2

|

RMSE |

AIC |

R2

|

RMSE |

AIC |

| Zero order |

0.860 |

7.72 |

82.87 |

0.858 |

7.82 |

83.19 |

| First order |

0.492 |

10.36 |

89.93 |

0.501 |

13.59 |

96.44 |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas |

0.897 |

6.64 |

79.24 |

0.939 |

5.74 |

75.75 |

| Weibull |

0.919 |

6.32 |

78.08 |

0.963 |

3.38 |

63.04 |

| Hixson-Crowell |

0.638 |

8.69 |

85.71 |

0.642 |

10.34 |

89.88 |

Table 6.

Composition of gels containing free extract and liposomes loaded with EP.

Table 6.

Composition of gels containing free extract and liposomes loaded with EP.

| Component |

Gel with EP |

Gel with EP_L |

| Carbopol 940 |

1% |

1% |

| Glycerin |

8% |

8% |

| EP |

1.5 % |

- |

| EP_L |

- |

2% |

| Vitamin E |

0.1 % |

0.1% |

| Eucalyptus essential oil |

0.1% |

0.1% |

| Sodium hydroxide 5 % |

q.s |

q.s |

| Purified water |

Up to 100% |

Up to 100% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).