1. Introduction

The Central Valley of California is of continental importance to wintering and migrating waterfowl, shorebirds, and other waterbirds, as well as grassland birds (Shuford 2014, Pandolfino et al. 2022). The Central Valley is about 644 km long by 64 km wide and runs north to south through the heart of the state, where it is surrounded by mountains except at its drainage into the San Francisco Bay estuary. It is divided mainly into the Sacramento Valley, draining southward, the San Joaquin Valley, draining northward, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta (hereafter Delta), where these rivers converge, and Suisun Marsh, where land-locked wetlands merge with tidal-dominated habitats of the San Francisco Bay estuary. The characteristics of the soil, geography, and climate make the Central Valley of California the most agriculturally productive region in the United States (Great Valley 2005).

In 1984, the Greater Sandhill Crane (Grus [Antigone] canadensis tabida) was listed as state threatened, pursuant to Fish and Game Code Sections 2070-2080 and Title 14 of the California Code of Regulations (FGC §2070-2080 and 14 CCR 670.5). The Greater Sandhill Cranes that winter in the Central Valley are members of the Central Valley Population (CVP). The breeding range of the CVP encompasses northeastern California, central and eastern Oregon, south-central Washington and interior British Columbia (Littlefield and Ivey 2002). Additionally, Lesser (G. c. canadensis) and Canadian Sandhill Cranes (G. c. rowani) that breed in Alaska and British Columbia winter in the Central Valley and are considered members of the Pacific Coast Population (PCP). Approximately 50,000 Sandhill Cranes occur in the Pacific Flyway, which include an estimated 35,000 G. c. canadensis, 5,000 G. c. rowani, and up to 10,000 G. c. tabida (Ivey et al. 2014a). The Central Valley hosts 100% of the Central Valley Population (CVP) of Greater Sandhill Cranes and >95% of the Pacific Coast Population (PCP) of Lesser Sandhill Cranes (G. c. canadensis) during the winter (Ivey 2014). Although Sandhill Crane numbers have increased significantly in California over the last century, current population and subspecies trends are uncertain. Considering available secondary data, Caven (2023) suggested that the CVP was probably stable and that apparent regional growth in the abundance of Sandhill Cranes wintering in California likely reflected growth of the PCP.

The loss of foraging habitats for waterbirds in the Central Valley has been a major concern in recent years (Central Valley Joint Venture 2020). Over the past three decades, Central Valley grasslands and other agricultural lands have been urbanized at a rate higher than in any other region of the United States (Johnson and Hayes 2004, Leu et al. 2006), in some cases eliminating Sandhill Crane foraging habitats. Traditional Central Valley crane wintering areas are also being degraded by habitat loss from conversion to incompatible crops (e.g., vineyards and orchards; Ivey 2014) and water development projects (Ivey 2015). Orchards and vineyards represent the fastest growing land use type and they cover approximately 15% of the valley (Pandolfino and Handel 2018). Pacific Flyway conservation plans, covering the CVP and the PCP identify conversion of grasslands and grain crops to permanent woody crops such as orchards and vineyards as a habitat conservation issue (Pacific Flyway Council 1997, 2020). As urbanization and habitat conversion to vineyards and orchards accelerates in the Central Valley, the enhancement and protection of crane roost sites close to wetland and agricultural foraging locations represents a key conservation objective (Shuford and Dybala 2017). Most of the current Sandhill Crane winter roosting sites are on conservation lands which will likely stay protected from long-term land use changes; however, most of their foraging occurs on unprotected private lands, which are adjacent to these protected roost sites (Littlefield 2002, Shaskey 2012). Habitat losses within these landscapes surrounding roost sites could threaten the future welfare of wintering cranes in this region.

Much of the Sandhill Crane’s historic wintering landscape within the Central Valley is no longer available because of the lack of suitable night roost sites. Most available wetlands are used for waterfowl hunting at disturbance levels which preclude crane use, therefore, cranes have developed traditions to use wetlands protected from such disturbance (i.e., mostly on National Wildlife Refuges and habitat conservation sites). It is likely that wintering Sandhill Cranes traditionally depended on the vast floodplain wetlands and the acorn crops provided by the historically extensive valley oak (Quercus lobata) savannahs and grasslands, but Central Valley wetlands have been reduced by over 90% since European settlement (Frayer et al. 1989), and oak savannahs and associated grasslands were similarly reduced. By the 1960s, over half of grasslands in the Central Valley were lost (Pandolfino and Handel 2018). However, like some waterfowl species (e.g., Foster et al. 2010), Sandhill Cranes have adapted to increases in agriculture and commonly feed in specific rowcrops, especially grain fields (Lovvorn and Kirkpatrick 1982, Krapu et al. 1984, Iverson et al. 1985, Reinecke and Krapu 1986; Sparling and Krapu 1994; Ballard and Thompson 2000; Littlefield 2002, Davis 2003). They are now highly dependent on flood-irrigated rowcrops such as rice, corn, and other cereal grains in California (Littlefield and Thompson 1979, Littlefield 2002, Ivey 2015).

Cranes only use a small proportion of the available habitat because they focus their habitat use around traditional night roost sites and show strong inter-annual fidelity to these sites and their associated foraging landscapes (Ivey et al. 2015). The size and bounds of foraging areas are limited by crane energetics, for example, Greater Sandhill Cranes rarely fly more than five kilometers from roost sites to forage (Ivey et al. 2015). These specific landscapes, which we term “cranescapes”, are centered around undisturbed, secure roost sites, or complexes of neighboring roost sites, and include the surrounding agricultural foraging habitats (Ivey et al. 2014b). Given that CVP and PCP Sandhill Cranes exhibit strong fidelity to wintering sites (Ivey et al. 2015), continued loss of foraging habitats within key cranescapes may reduce carrying capacity, and continued habitat loss could ultimately threaten their viability (Ivey et al. 2016). Therefore, it is important to understand the rate of habitat loss in these cranescapes in order to mitigate it through targeted conservation action. In this paper, we assess loss rates of landcover types that serve as suitable Sandhill Crane habitat in Central Valley cranescapes to further habitat conservation planning for the species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Crane Locational Data

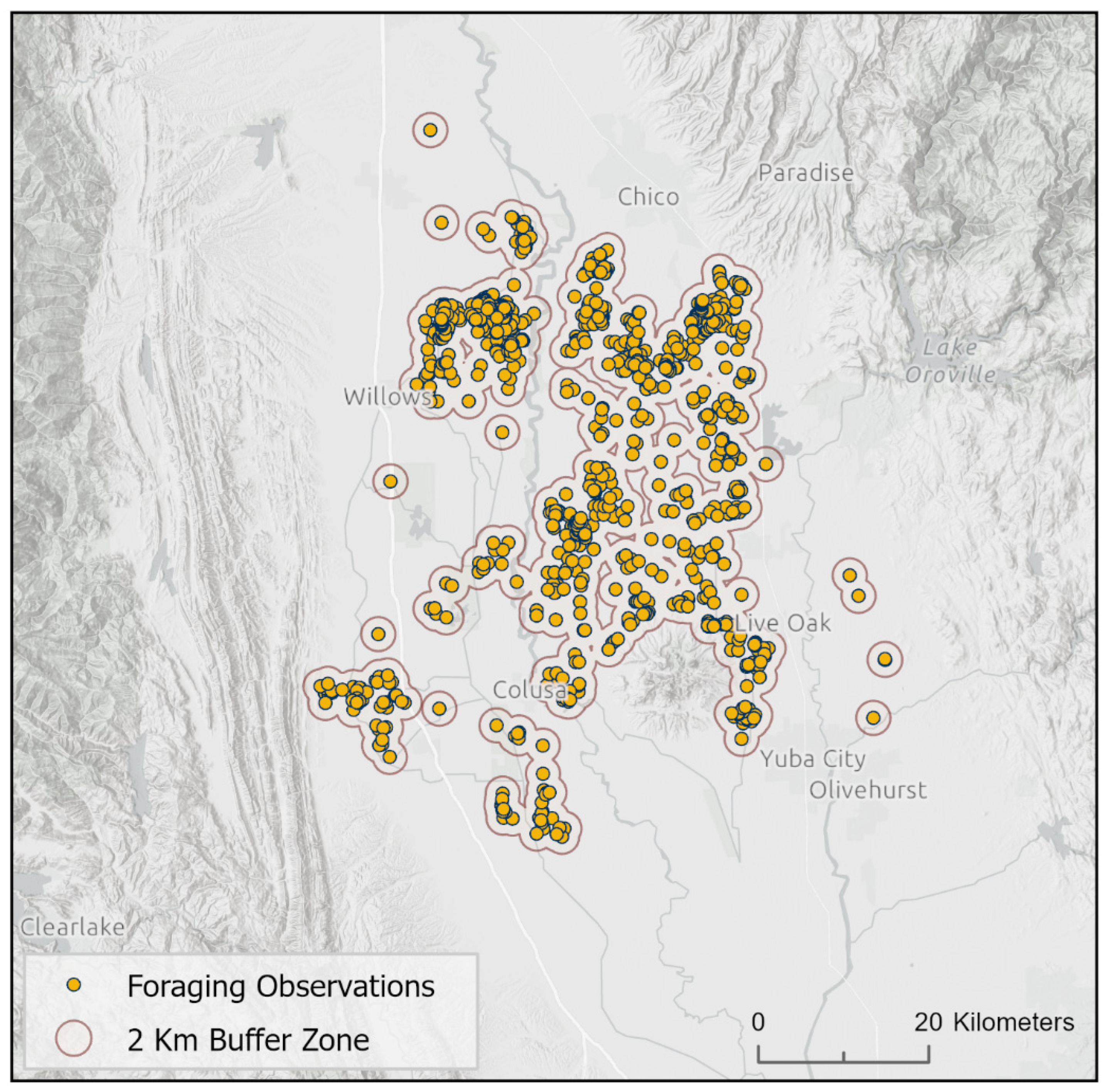

We used 7,187 crane foraging locations from multiple previous survey efforts (1991-2013) to define our study area. We included data from radio telemetry locations (77 radio-marked cranes) and field observations from a 2008-2009 study in the Delta (Ivey et al. 2015). Additionally, we used data from winter foraging flock surveys conducted from December 2012 through February 2013 on private lands throughout the Central Valley. Finally, we included 2012-13 reports of flocks on the ground from eBird (Sullivan et al. 2009) in our dataset, as described in Ivey et al. (2016). These survey efforts informed the four priority Central Valley wintering areas assessed in this study: 1) the Sacramento Valley between Marysville and Chico; 2) Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta; 3) northern San Joaquin Valley (San Joaquin River NWR and Grasslands Region); and 4) southern San Joaquin Valley (Pixley NWR area;

Figure 1).

Sandhill Cranes forage in a wide range of habitats, including grasslands, wetlands, and a variety row crops; however, use of orchards, vineyards, blueberries, or nursery areas was never documented in a study of crane foraging in the Delta (Ivey et al. 2025). Cranes likely avoid these habitats because trees and shrubs make it difficult to see approaching predators and offer limited food value. For the sake of simplicity, and based on crane foraging choices (see Ivey et al. 2025), we categorized landcover types, including crops, as compatible with Sandhill Crane habitat use (e.g., cereal grains and grasslands) or incompatible (e.g., woody crops and forests). We also assessed annual trends in demonstrably important foraging and roosting landcovers.

2.2. Geospatial Data

Using the crane location data described above, we created a 2-kilometer buffer around all confirmed crane observation points to capture nearby foraging and roosting habitat, consistent with daily dispersal patterns for Sandhill Cranes in this region (i.e., mean foraging flight distance for the greater subspecies; Ivey et al. 2015). The resulting shapefile defined the spatial extent of our study area. We did not modify the polygons to fill gaps or smooth the edges (see

Figure 2).

Annual land cover data were obtained from the USDA Cropland Data Layer (CDL) for the years 2008 through 2023 (USDA 2024). The CDL is a 30-meter resolution, satellite-derived raster dataset that provides detailed crop classification across U.S. agricultural landscapes. Each year’s CDL raster was clipped to the 2-kilometer buffered crane use polygons. These steps reduced the spatial extent of analysis to only those portions of the landscape (cranescapes) likely to influence crane winter habitat availability. This resulted in a total study area of 4,260 km2, which was divided into four aforementioned units including the Sacramento Valley (1,827 km2), the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta (1,430 km2), the Northern San Joaquin River Valley (738 km2), and the Southern San Joaquin River Valley (265 km2).

Two classification crosswalks were developed to support habitat interpretation:

The first grouped CDL crop codes into ecologically meaningful landcover categories (e.g., “Alfalfa,” “Rice,” “Orchard and Vineyard”) based on similarities in crop taxonomy, structure, and phenology (

Table A1).

The second assigned each CDL code as either

compatible or

incompatible with winter habitat use by cranes, informed by expert knowledge of crane behavior, foraging ecology, and prior regional studies (

Table A2).

All geospatial processing and raster summarization steps were performed in Python 3.11.10 using the ArcPy site package from ArcGIS Pro (version 3.5.0). Raster clips and reclassifications were created using the 2-km buffered extent of observations from all years, and annual summaries of total area (in hectares) were extracted for each reclassified landcover type and habitat compatibility class.

2.3. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the open-source statistical software program R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team 2024). We determined whether a trend in landcover suitability or the proportional cover of relevant classes was present from 2008 to 2023 with a Mann-Kendall Trend Test (τ) using the “Kendall” package in R (Mann 1945, Kendall 1975, McLeod 2022). This test determines if there is a consistent monotonic upward or downward trend in a variable through time; it can accommodate non-linear trends and non-normal data and it is generally robust to temporal autocorrelation (Kendall 1975). However, this analytical approach does not estimate periodic (e.g., annual) rates of change. Therefore, if a monotonic trend was detected per the Mann-Kendall Test, we subsequently estimated annual rates of change (B) with 95% confidence intervals using Generalized Linear Models with a Gaussian distribution and an “identity” link function (GLMs; Nelder and Wedderburn 1972; Venables and Ripley 2002). Finally, to ensure we also had a strong non-linear interpretation of temporal trends in landcover we assessed trendlines using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing regression (LOESS; Cleveland et al. 1992). Local regression, as the technique is often termed, allowed us to predict landcover values using LOESS trendlines based on our landcover data. A mixed methods approach to trend analysis is regularly employed as the various approaches provide differing products, are generally robust to different analytical assumptions, and ultimately provide validation and additional description of documented trends (e.g., Rehman 2013). Finally, we employed a Kruskal-Wallis H test including a Dunn post hoc test (Z) with a Benjamini-Hochberg p-value correction to discern differences in landcover composition across major CVP wintering regions using the “FSA” package (Kruskal and Wallis 1952, Benjamini and Hochberg 1995, Ogle et al. 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Cranescape Suitability

On average, about 75.7% of landcover was compatible with crane habitat (i.e., “suitable”) across priority wintering areas and years (range = 62.1% to 88.7%). Suitability varied significantly across priority cranescapes (H = 18.05, p<0.001) from 2008 to 2023. Suitability was highest in the Southern San Joaquin Valley (78.7%±4.3%; x̄±95% C.I.), closely followed by the Sacramento Valley (78.6±1.9%). The Northern San Joaquin Valley (75.3±3.3%) was lower than the aforementioned priority wintering areas but had higher crane landcover suitability than the Delta (70.1±2.1%). Ultimately, all other priority wintering areas had significantly higher cranescape habitat compatibility than the Delta (Z >2.4 & p<0.03 across Dunn post-hoc tests), but these areas did not differ significantly from each other.

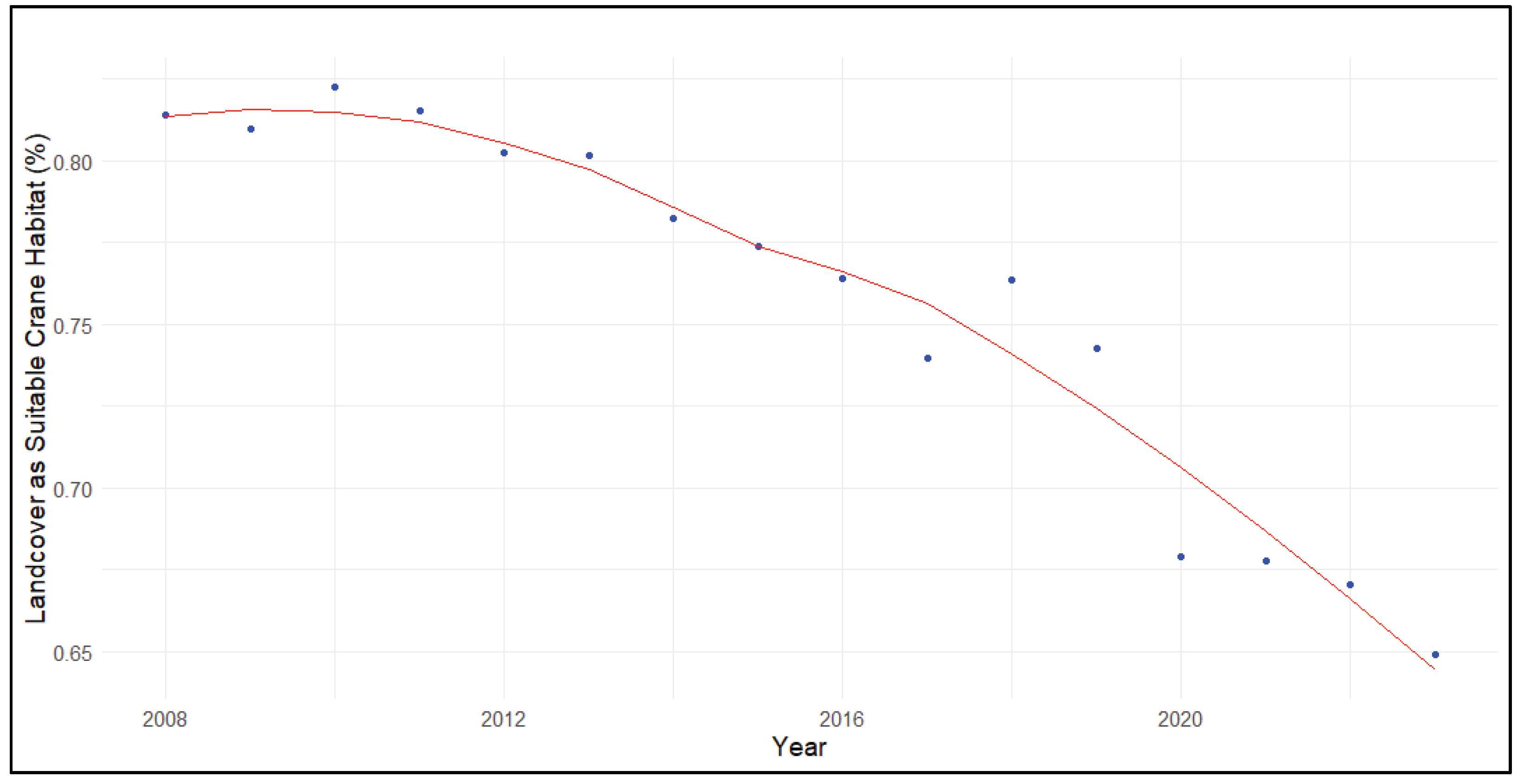

Landcover compatible with crane habitat declined from 2008 to 2023 (

τ = -0.90,

p< 0.001) across priority Sandhill Crane wintering areas at a rate of about -1.15±0.21% annually (

B±95% C.I.). On average, suitable landcover was >80.0% from 2008 to 2013, >73.0% from 2014 to 2019, and <68% since 2020 across priority wintering areas. The best fit LOESS trendline demonstrated that cranescape suitability for habitat use declined from >81% in 2008 to <65% in 2023 on average across priority wintering areas (

Figure 3). This decline was present within individual priority crane wintering areas to varying degrees. In the Sacramento Valley (

τ = -0.70,

p< 0.001) habitat compatibility declined at an estimated rate of -0.69±0.21% annually from about 80% in 2008 to about 71% in 2023. Landcover providing apparently suitable crane habitat in the Delta area declined (

τ = -0.83,

p< 0.001) at a rate of -0.84±0.17% annually from about 75% to about 62% per LOESS trendline. The decline in habitat compatibility in the Northern San Joaquin Valley was comparatively steep (

τ = -0.88,

p< 0.001; -1.31±0.26% annually) and declined from about 83% to about 63% from 2008 to 2023. Finally, cranescape suitability within the Southern San Joaquin River Valley declined most steeply on an annual basis (

τ = -0.88,

p< 0.001; -1.77±0.28%) from about 88% in 2008 to 62% in 2023 per LOESS trendline.

3.2. Key Landcover Trends

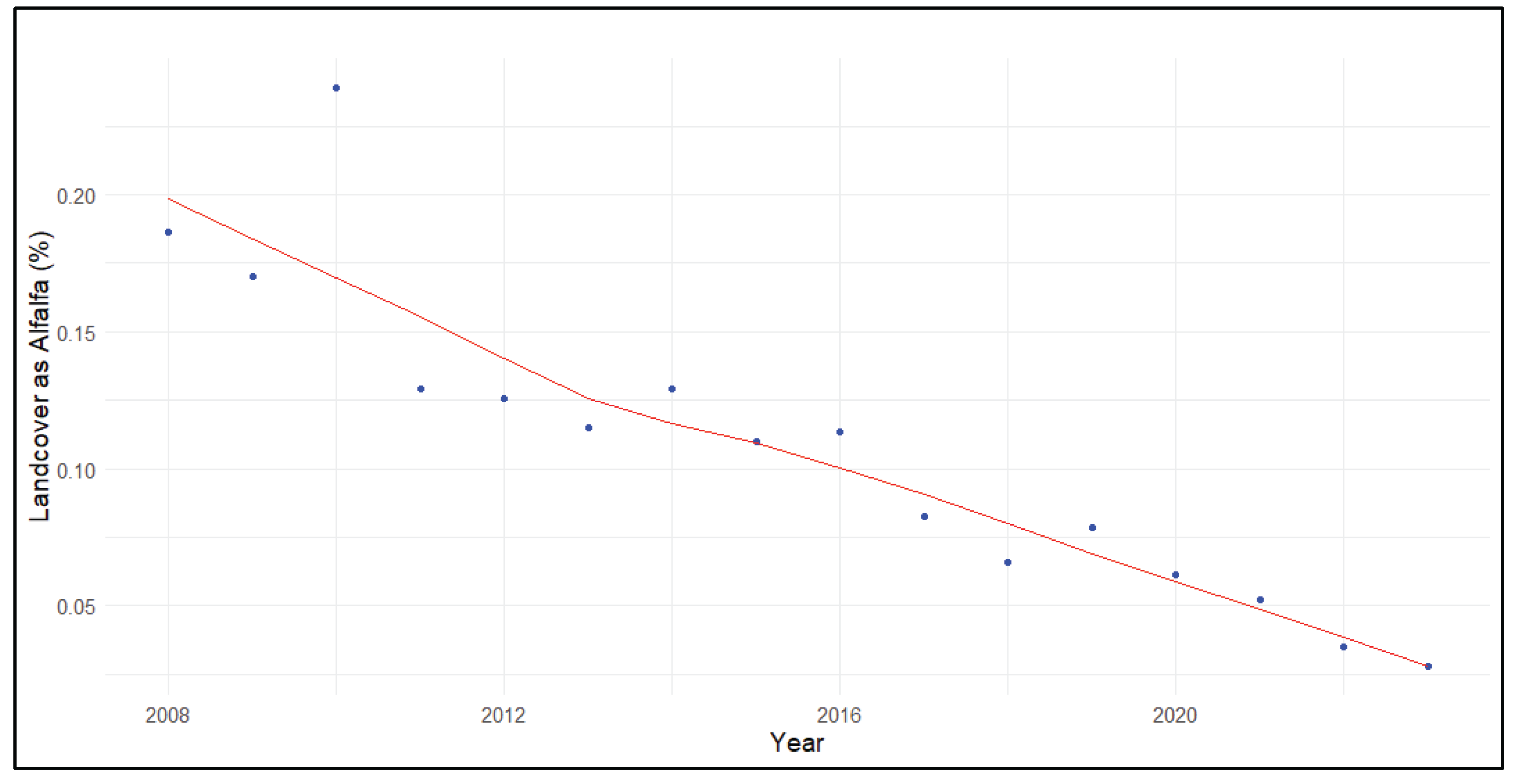

Alfalfa declined across priority cranescapes (

τ = -0.72,

p<0.001) at a rate of about -0.51±0.12% annually from 2008 to 2023. The decline was detected at all priority wintering areas with the exception of the Delta, where there was no monotonic trend over time. The decline in alfalfa landcover was steepest in the South San Joaquin Valley (

τ = -0.90,

p<0.001) where it disappeared at a rate of -1.10±0.24% annually. The LOESS trendline demonstrated that alfalfa declined from nearly 20% landcover in 2008 to <3% landcover in 2023 in the Southern San Joaquin Valley (

Figure 4).

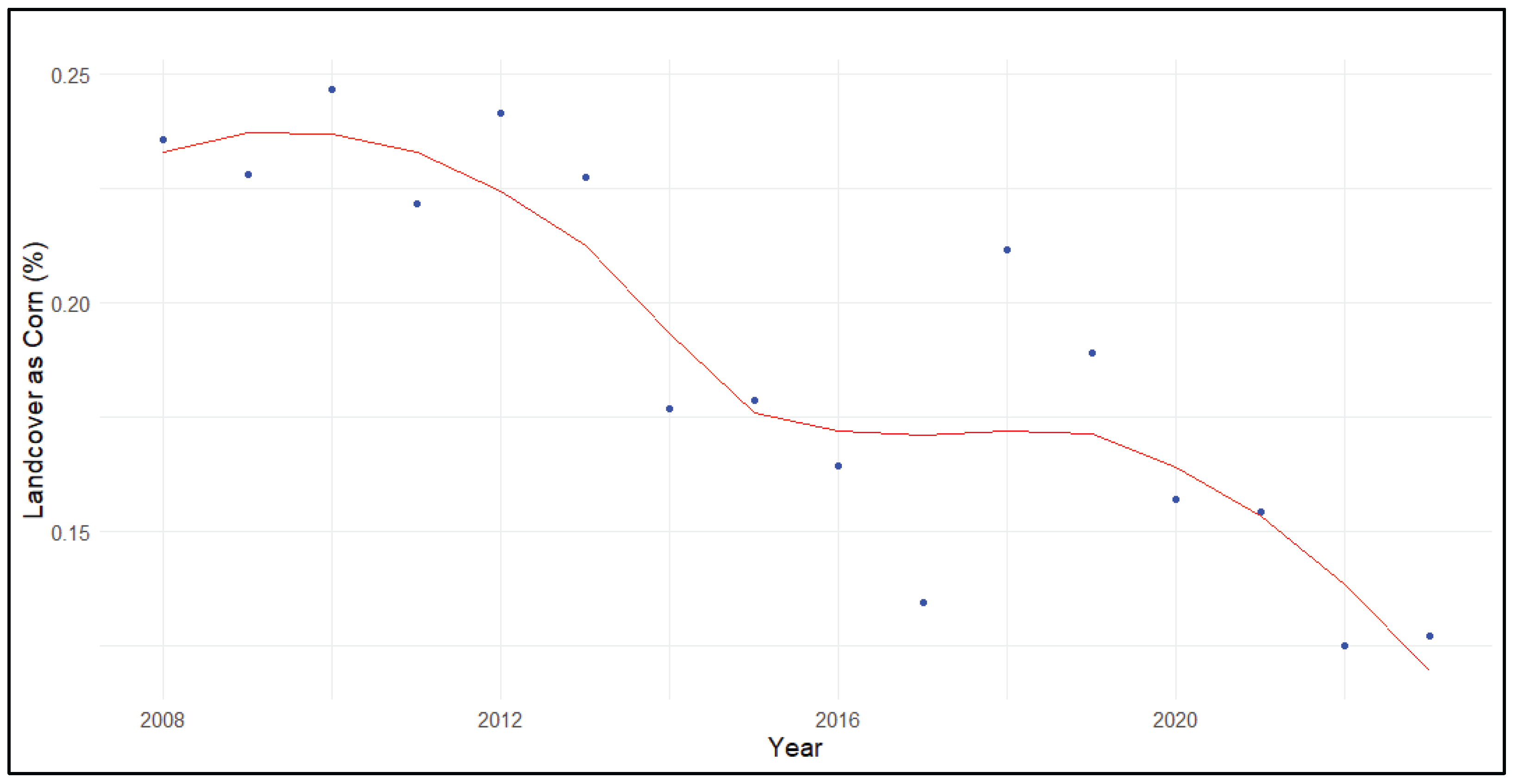

The decline in corn rotations was only marginally significant across priority wintering areas (τ = -0.37,

p=0.053) with a predicted annualized trend of -0.25±0.24%. A declining trend was significant but modest in the Sacramento Valley (τ = -0.58,

p=0.002;

B= -0.06±0.03%). A declining trend in corn rotations was most apparent in priority wintering areas in the Delta (τ = -0.70,

p<0.001;

B= -0.76±0.24%) where the corn landcover declined from >23% in 2008 to <12% in 2023 per LOESS trendline (

Figure 5). There was no significant trend in corn rotation landcover in the Northern or Southern San Joaquin Valley.

Overall, there was no trend in developed landcover across priority Sandhill Crane wintering areas. However, trends were significant within particular priority areas. For instance, developed landcover increased (τ = 0.57, p=0.003; B = 0.16±0.06%) in the Southern San Joaquin Valley wintering area and actually decreased modestly in the Sacramento Valley (τ = -0.53, p=0.005; B = -0.05±0.02%) and the Northern San Joaquin Valley (τ = -0.53, p=0.005; B = -0.06±0.03%). There was no significant trend in the Delta. Developed landcover in the Southern San Joaquin Valley increased from <4% in 2008 to >6% in 2023.

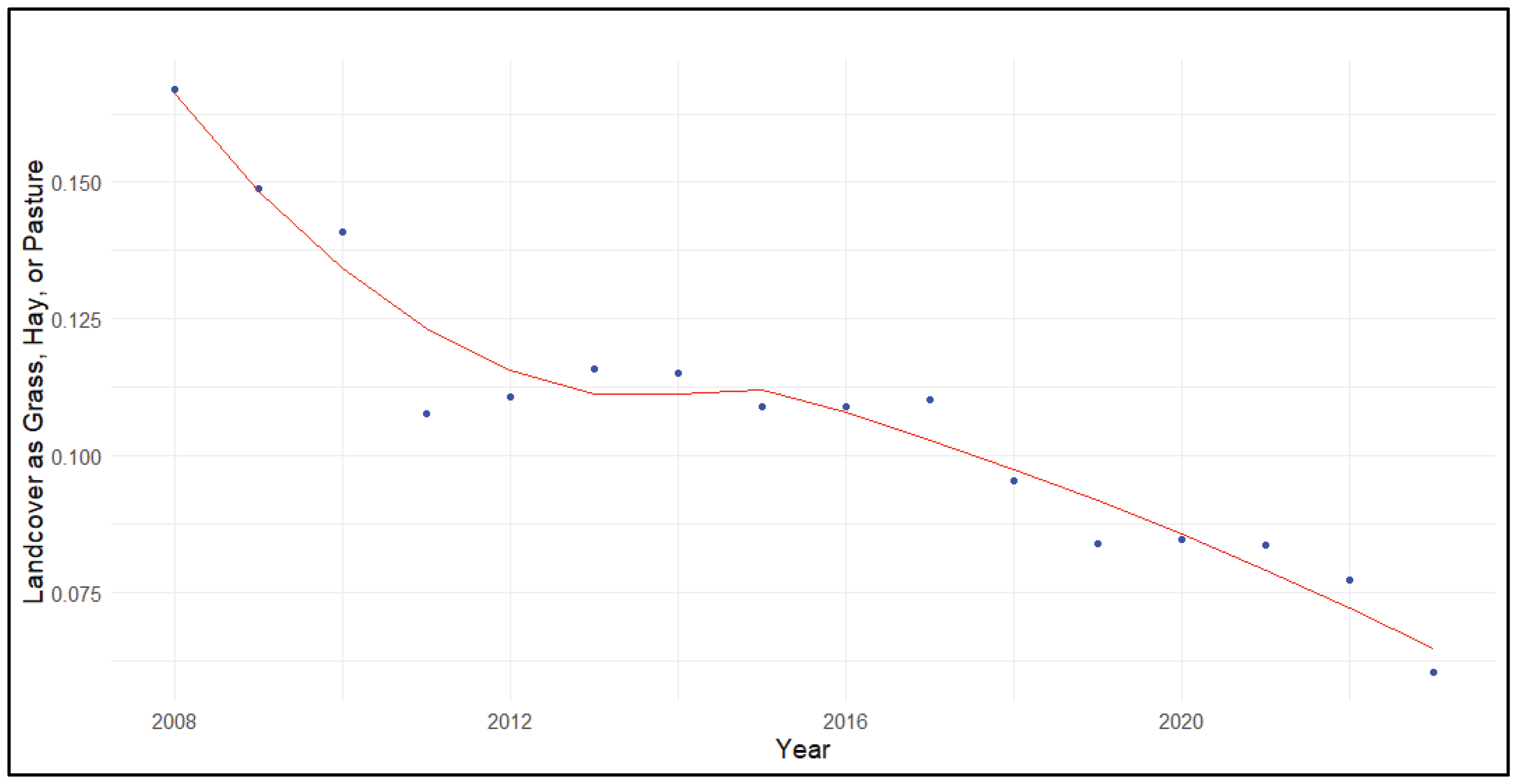

The decline in grassland landcovers, including hay meadow and pasture, was significant across priority wintering areas (τ = -0.70,

p<0.001;

B = -0.36±0.16%). This declining trend was pronounced and significant in the Delta (τ = -0.90,

p<0.001;

B = -0.46±0.15%) and the Northern San Joaquin Valley (τ = -0.82,

p<0.001;

B = -0.54±0.11%;

Figure 6). However, the negative trend was only marginally significant and more modest in the Sacramento Valley (τ = -0.35,

p= 0.065;

B = -0.13±0.07) and the Southern San Joaquin Valley (τ = -0.32,

p=0.096;

B = -0.30±0.47).

Rice landcover declined across priority wintering areas (τ = -0.43, p=0.022; B = -0.20±15%). However, trends varied across specific regions. For instance, rice landcover increased marginally in the Delta area (τ = 0.33, p=0.079; B = 0.10±0.07%) as well as within the Southern San Joaquin Valley (τ = 0.41, p=0.061; B = 5.8e-05±5.5e-05%) but declined significantly in the Sacramento Valley (τ = -0.48, p=0.010; B = -0.88±0.58%). There was no apparent trend in the Northern San Joaquin Valley.

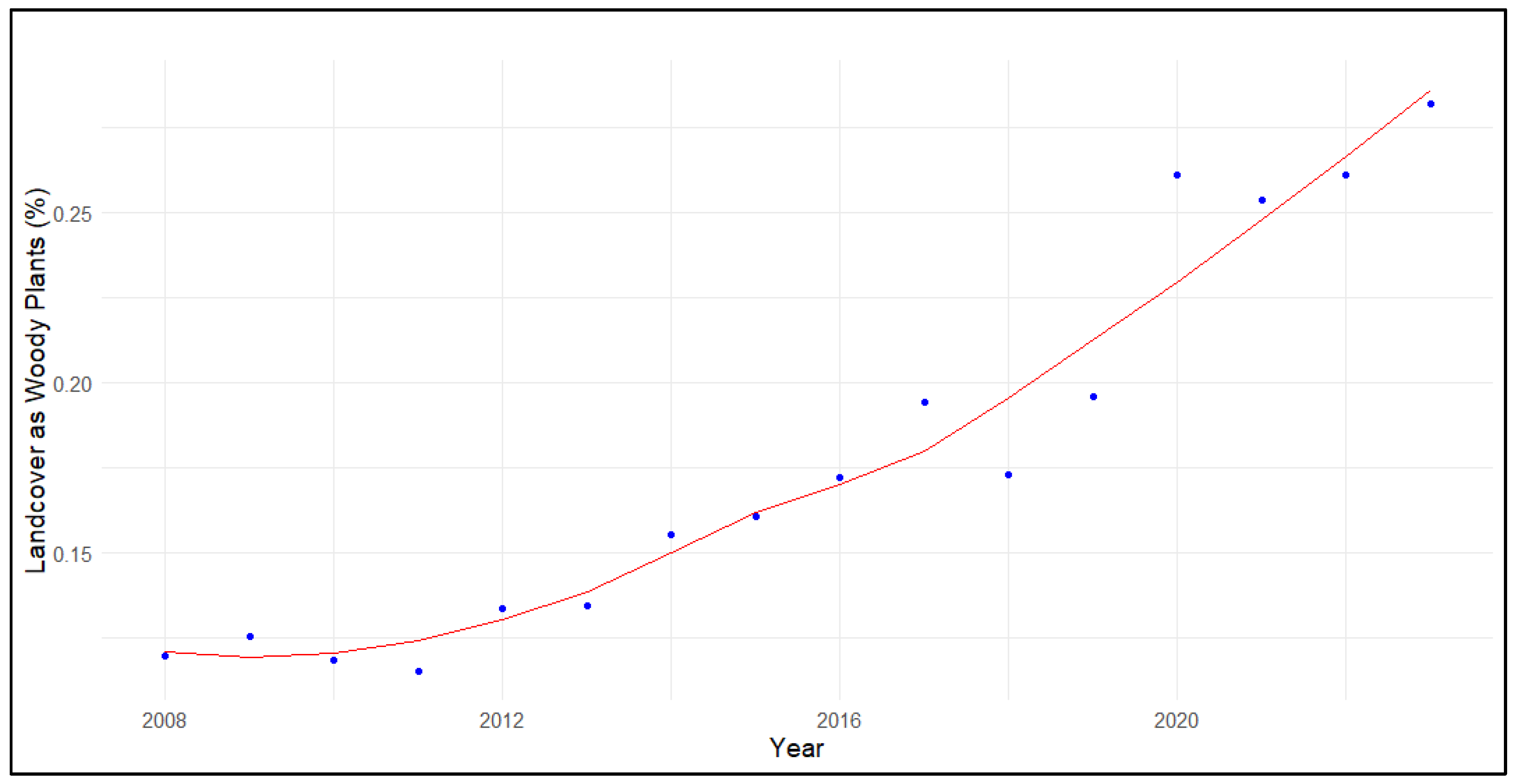

There was a significant increase in the proportional landcover of woody species across priority crane wintering areas (τ = -0.88,

p<0.001;

B = 1.14±0.20%) including natural forests and shrublands (e.g., deciduous forest) as well as cultivated analogs (e.g., almonds, olives, grapes, etc.). The increasing trend was relatively consistent across priority wintering areas with a predicted value of about 12% woody landcover in 2008 and 29% across sites in 2023 per LOESS trendline (

Figure 7).

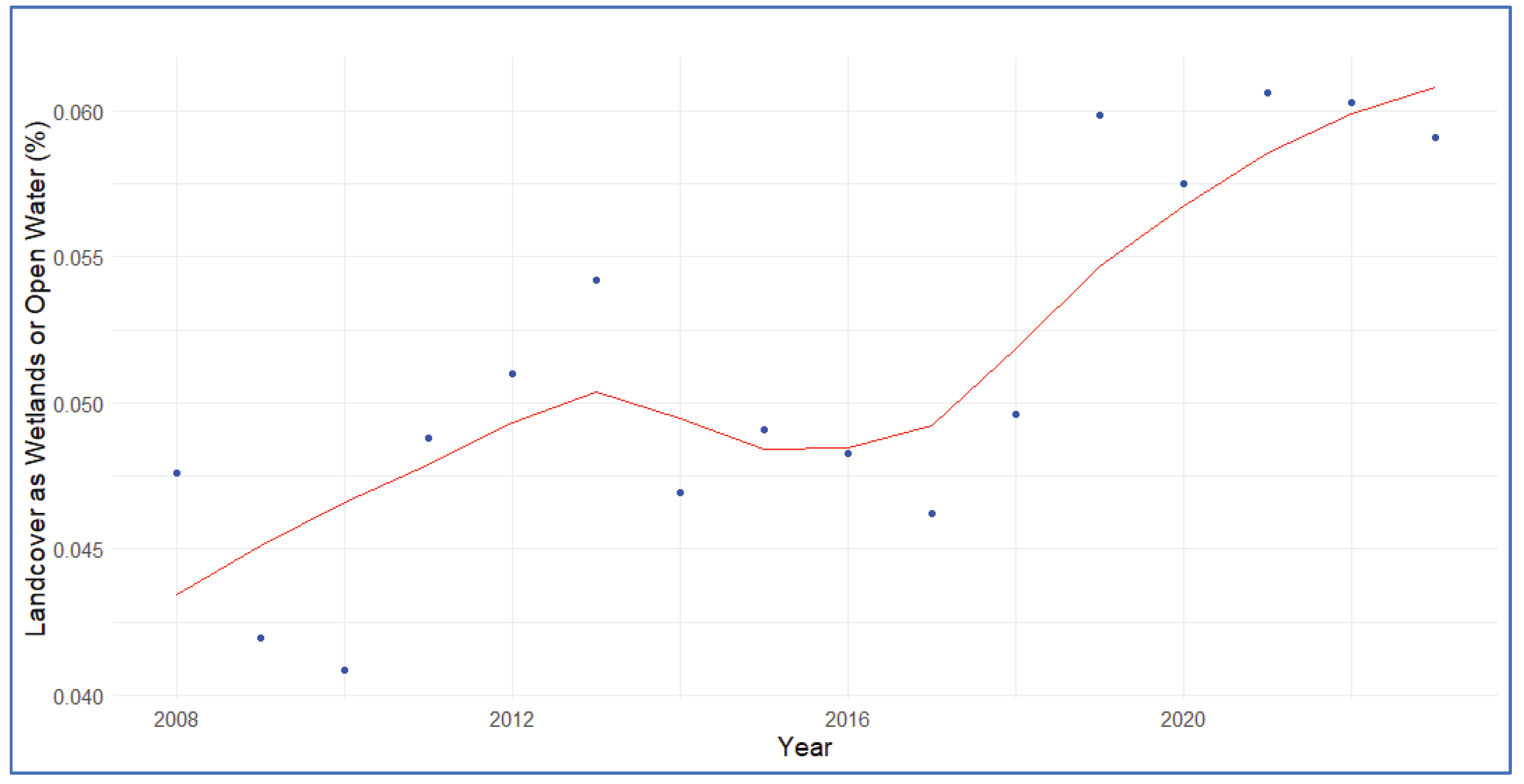

Wetland landcover, including open water, emergent wetlands, and aquicultural systems, generally increased across priority wintering areas for Sandhill Cranes in California (τ = 0.55,

p=0.003;

B = 0.11±0.04%;

Figure 8). Looking at specific priority areas, the North (τ = 0.57,

p=0.003;

B = 0.31±0.10%) and South (τ = 0.48,

p=0.010;

B = 0.03±0.02%) San Joaquin Valley sites saw significant increases in wetland landcover. There was a marginally significant increase in wetland landcover within the Sacramento Valley (τ = 0.32,

p=0.096;

B = 0.08±0.07%) and no trend in the Delta.

4. Discussion

Suitable landcover is decreasing for Sandhill Crane populations that winter in California. However, the impacts are likely more pronounced for foraging than roosting sites. The data indicate that roosting options (i.e., wetlands and open water) may have increased marginally over time. By contrast, natural and agricultural foraging areas including row crop agriculture (e.g., corn, rice) and grassland habitats (e.g., pastures) have declined steadily since 2008. Such declines in suitable foraging habitats may eventually reduce the carrying capacity of these important Central Valley cranescapes.

Other avian species are also vulnerable to habitat declines in California. One study documented that 97% of 61 bird taxa studied there are threatened by habitat loss (Shuford and Gardali 2008), while a similar study reported that 97% of 92 bird taxa are threatened by habitat loss in California (Wiens and Gardali 2013). Also, grassland bird abundance in California has been declining more rapidly than the net loss of grassland habitat (Pandolfino and Douglas 2022). Although Pacific Flyway populations of Sandhill Cranes have increased markedly from historic lows in the 1940s (Ivey et al. 2014a), their current population status and trends are relatively unknown. The only comprehensive Sandhill Crane survey conducted in the Pacific Flyway annually in January, is the Mid-Winter Waterfowl Survey. However, that survey of the Central Valley historically focused on counting waterfowl, which causes the crane estimates to be highly variable and somewhat unreliable (Ivey et al. 2014a). That survey was standardized in 2016 by California Department of Fish and Wildlife and is now more statistically valid in tracking wintering Sandhill Crane population trends.

Our analyses indicates the availability of suitable foraging habitat was variable across priority Sandhill Crane wintering areas. The percentage of suitable landcover was lowest in the two regions that support the highest numbers of wintering cranes; the Delta and Northern San Joaquin Valley (Ivey et al. 2014a), making cranes wintering in these two areas more vulnerable to continued foraging habitat losses. Habitat loss rates varied by region. From 2008-2023, the Sacramento Valley lost 9%, the Delta lost 13%, the Northern San Joaquin Valley lost 20%, and the Southern San Joaquin Valley lost 26% of suitable foraging habitat. Corn is among the most selected crops by foraging Sandhill Cranes and is particularly important in the Delta (Ivey et al. 2025). Our results show an approximate 11% decline in corn in the Delta. Our results indicate that the main conservation challenge for Sandhill Cranes in the Central Valley, at the current time, is ensuring sufficient foraging habitat within each cranescape to support wintering populations.

Grassland birds and shorebirds, which require shallow wetlands, are facing some of the steepest declines among all North American avian taxa (Rosenberg et al. 2019). The Central Valley of California represents a highly important wintering site for these taxa within the Pacific Flyway, and local habitat loss rates, projected forward, could have flyway- and population-level impacts on key species of concern, especially considering additional stressors related to climate change (Wilson et al. 2022). Cranes have the capacity to serve as a “flagship” or “umbrella” species as meeting their habitat needs will benefit a range of other wetland- and grassland-dependent species (Kim et al. 2021, Xu et al. 2025). Developing robust goals for Sandhill Crane habitat conservation and clearly identifying the ancillary benefits of key actions for other taxa may present an effective conservation strategy for developing partnerships and administering priority conservation actions for the CVP and PCP. Our work highlights the vulnerability of the Greater Sandhill Cranes within the state of California and indicates that clear habitat objectives should be met before any change is made in the species’ protected status at the state level.

Our results do not reflect the state as a whole, but a limited area encompassing 4,260 km2 that is important to Sandhill Cranes. We examined trends in landcover that represent appropriate (i.e., “suitable” or “compatible”) habitat for Sandhill Cranes and not trends in habitat quality or availability as estimated per models. Therefore, we provide a relatively direct assessment of change in landcover relevant to Sandhill Cranes. Habitat selection models provide an approximation of static habitat preferences at a point in time yet Sandhill Cranes are very flexible and can adapt to a range of herbaceous agricultural landcovers (Hemminger et al. 2022). Additionally, we already have a strong understanding of Sandhill Crane habitat use patterns in a variety of contexts (Lovvorn and Kirkpatrick 1982, Krapu et al. 1984, Iverson et al. 1985, Reinecke and Krapu 1986, Sparling and Krapu 1994, Ballard and Thompson 2000, Littlefield 2002, Davis 2003). Finally, measuring changes in landcover categories that provision Sandhill Crane roosting and foraging habitat, and those that are antithetical to it, more directly informs conservation actions for priority Sandhill Crane wintering areas. For instance, based on our analysis, grassland conservation efforts should likely be a key priority in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, where grassland landcover has declined most steeply. However, supporting rice agriculture may be a higher priority in the Sacramento Valley where that crop type, which provides both roosting and foraging benefits when managed correctly, has declined most sharply. Given our contexts, we ultimately felt that the tracking of landcover change provided more pertinent information for Sandhill Crane conservation than a habitat modeling approach extrapolated through time.

5. Conclusions

Our research documented a broad decline in the landcover of suitable habitats for Greater Sandhill Cranes within their core wintering range in the Central Valley of California. This introduces the key question of how to combat these habitat losses for the benefit of Greater Sandhill Cranes and other wetland and grassland-dependent avifauna that utilize the region. Within the Central Valley, beyond our study area, there are more suitable Sandhill Crane foraging habitats, predominantly on private farms. Our study area only encompassed approximately 24% of the Central Valley’s agricultural lands. However, due to the species’ energetic constraints and the limited availability of suitable roosting sites, many potential alternative foraging areas in the region are not available to cranes (Pearse et al. 2017, Collins et al. 2023, Ivey et al. 2014b). Because cranes are so loyal to traditional winter roosting sites in the Central Valley, they generally do not readily pioneer into new areas (Ivey et al. 2014b, Collins et al. 2023). Therefore, we suggest that an assessment of priorities for Sandhill Crane habitat conservation should first consider whether the roost site distribution is adequate within a given region, and secondly whether the associated foraging landscapes around those roosts are adequate to support cranes. Conservation strategies for each major crane wintering region should likely include: (1) conservation of existing unprotected roost sites through easements or fee-title acquisitions from willing sellers; (2) safeguarding foraging landscapes around these roosts, primarily via easements that restrict incompatible crops and development; (3) enhancing food availability within these landscapes by improving management on conservation lands and providing annual incentives for private land improvements; and (4) establishing additional and secure roosting sites along the edges of the species’ current wintering range to expand access to foraging areas (Ivey et al. 2015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our manuscript is based on secondary data including a significant amount of visual survey data that would not require approval by an Animal Care and Use Committee, much of which was described in Ivey et al. (2016; see literature cited). However, we do include data from 77 tracked cranes, which was originally described by Ivey et al. (2015; see literature cited). Regarding this data, the “...handling of cranes was conducted under the guidelines of the Oregon State University Animal Care and Use Committee (project no. 3605) to ensure that methods were in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and U.S. Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training policies.” Cranes were captured under California Department of Fish and Wildlife permit no. SC-803070-02 and United States Geological Survey federal banding permit no. MB 21142.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the International Crane Foundation’s Conservation Impact Fund, project number 1047. We want to thank anonymous reviewers and the editorial team at Birds for their helpful edits. We awant to thank the myriad of parterns working on Sandhill Crane conservation issues in California including but not limited to the Friends of Stone Lakes, Sacramento Audubon, Sacramento Chapter of the Sierra Club, Sacramento Zoo, Motherlode Chapter of the Sierra Club, International Crane Foundation, Save our Sandhill Cranes, Sacramento Shasta Chapter of The Wildlife Society, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, the California Department of Water Resources, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Central Valley Joint Venture.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Grouped Crop Type Reclassification Table.

Table A1.

Grouped Crop Type Reclassification Table.

| class_name |

attribute |

reclassified_name |

| Alfalfa |

36 |

Alfalfa |

| Corn |

1 |

Corn_rotations |

| Sweet Corn |

12 |

Corn_rotations |

| Pop or Orn Corn |

13 |

Corn_rotations |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Corn |

225 |

Corn_rotations |

| Dbl Crop Oats/Corn |

226 |

Corn_rotations |

| Dbl Crop Triticale/Corn |

228 |

Corn_rotations |

| Dbl Crop Corn/Soybeans |

241 |

Corn_rotations |

| Developed |

82 |

Developed |

| Developed/Open Space |

121 |

Developed |

| Developed/Low Intensity |

122 |

Developed |

| Developed/Med Intensity |

123 |

Developed |

| Developed/High Intensity |

124 |

Developed |

| Sod/Grass Seed |

59 |

Grass_hay |

| Switchgrass |

60 |

Grass_hay |

| Pasture/Grass |

62 |

Grass_hay |

| Grassland/Pasture |

176 |

Grass_hay |

| Cotton |

2 |

Other |

| Sunflower |

6 |

Other |

| Peanuts |

10 |

Other |

| Tobacco |

11 |

Other |

| Mint |

14 |

Other |

| Canola |

31 |

Other |

| Flaxseed |

32 |

Other |

| Safflower |

33 |

Other |

| Brassica napus |

34 |

Other |

| Mustard |

35 |

Other |

| Other Hay/Non Alfalfa |

37 |

Other |

| Camelina |

38 |

Other |

| Sugarbeets |

41 |

Other |

| Dry Beans |

42 |

Other |

| Potatoes |

43 |

Other |

| Other Crops |

44 |

Other |

| Sugarcane |

45 |

Other |

| Sweet Potatoes |

46 |

Other |

| Misc Vegs & Fruits |

47 |

Other |

| Watermelons |

48 |

Other |

| Onions |

49 |

Other |

| Cucumbers |

50 |

Other |

| Chick Peas |

51 |

Other |

| Lentils |

52 |

Other |

| Peas |

53 |

Other |

| Tomatoes |

54 |

Other |

| Caneberries |

55 |

Other |

| Hops |

56 |

Other |

| Herbs |

57 |

Other |

| Clover/Wildflowers |

58 |

Other |

| Fallow/Idle Cropland |

61 |

Other |

| Barren |

65 |

Other |

| Clouds/No Data |

81 |

Other |

| Nonag/Undefined |

88 |

Other |

| Perennial Ice/Snow |

112 |

Other |

| Barren |

131 |

Other |

| Carrots |

206 |

Other |

| Asparagus |

207 |

Other |

| Garlic |

208 |

Other |

| Cantaloupes |

209 |

Other |

| Honeydew Melons |

213 |

Other |

| Broccoli |

214 |

Other |

| Greens |

219 |

Other |

| Strawberries |

221 |

Other |

| Squash |

222 |

Other |

| Vetch |

224 |

Other |

| Lettuce |

227 |

Other |

| Pumpkins |

229 |

Other |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Cantaloupe |

231 |

Other |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Cotton |

232 |

Other |

| Cabbage |

243 |

Other |

| Cauliflower |

244 |

Other |

| Celery |

245 |

Other |

| Radishes |

246 |

Other |

| Turnips |

247 |

Other |

| Eggplants |

248 |

Other |

| Gourds |

249 |

Other |

| Cranberries |

250 |

Other |

| Rice |

3 |

Rice |

| Other Small Grains |

25 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Oats |

28 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Buckwheat |

39 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Sorghum |

4 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Millet |

29 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Soybeans |

5 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Soybeans |

26 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Dbl Crop Soybeans/Cotton |

239 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Dbl Crop Soybeans/Oats |

240 |

Soy_Sorghum_SmallGrains |

| Water |

83 |

Wetlands_water |

| Wetlands |

87 |

Wetlands_water |

| Aquaculture |

92 |

Wetlands_water |

| Open Water |

111 |

Wetlands_water |

| Herbaceous Wetlands |

195 |

Wetlands_water |

| Barley |

21 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Durum Wheat |

22 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Spring Wheat |

23 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Winter Wheat |

24 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Rye |

27 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Speltz |

30 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Triticale |

205 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Durum Wht |

230 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Barley |

233 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Durum Wht/Sorghum |

234 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Sorghum |

235 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Sorghum |

236 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Corn |

237 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Cotton |

238 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Soybeans |

254 |

Wheat_barley_relatives |

| Forest |

63 |

Woody |

| Shrubland |

64 |

Woody |

| Cherries |

66 |

Woody |

| Peaches |

67 |

Woody |

| Apples |

68 |

Woody |

| Grapes |

69 |

Woody |

| Christmas Trees |

70 |

Woody |

| Other Tree Crops |

71 |

Woody |

| Citrus |

72 |

Woody |

| Pecans |

74 |

Woody |

| Almonds |

75 |

Woody |

| Walnuts |

76 |

Woody |

| Pears |

77 |

Woody |

| Deciduous Forest |

141 |

Woody |

| Evergreen Forest |

142 |

Woody |

| Mixed Forest |

143 |

Woody |

| Shrubland |

152 |

Woody |

| Woody Wetlands |

190 |

Woody |

| Pistachios |

204 |

Woody |

| Prunes |

210 |

Woody |

| Olives |

211 |

Woody |

| Oranges |

212 |

Woody |

| Avocados |

215 |

Woody |

| Peppers |

216 |

Woody |

| Pomegranates |

217 |

Woody |

| Nectarines |

218 |

Woody |

| Plums |

220 |

Woody |

| Apricots |

223 |

Woody |

| Blueberries |

242 |

Woody |

Table A2.

Crop Compatibility Reclassification Table.

Table A2.

Crop Compatibility Reclassification Table.

| class_name |

attribute |

reclassified_nam |

| Corn |

1 |

compatible |

| Cotton |

2 |

compatible |

| Rice |

3 |

compatible |

| Sorghum |

4 |

compatible |

| Soybeans |

5 |

compatible |

| Sunflower |

6 |

compatible |

| Peanuts |

10 |

compatible |

| Tobacco |

11 |

compatible |

| Sweet Corn |

12 |

compatible |

| Pop or Orn Corn |

13 |

compatible |

| Mint |

14 |

compatible |

| Barley |

21 |

compatible |

| Durum Wheat |

22 |

compatible |

| Spring Wheat |

23 |

compatible |

| Winter Wheat |

24 |

compatible |

| Other Small Grains |

25 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Soybeans |

26 |

compatible |

| Rye |

27 |

compatible |

| Oats |

28 |

compatible |

| Millet |

29 |

compatible |

| Speltz |

30 |

compatible |

| Canola |

31 |

compatible |

| Flaxseed |

32 |

compatible |

| Safflower |

33 |

compatible |

| Brassica napus |

34 |

compatible |

| Mustard |

35 |

compatible |

| Alfalfa |

36 |

compatible |

| Other Hay/Non Alfalfa |

37 |

compatible |

| Camelina |

38 |

compatible |

| Buckwheat |

39 |

compatible |

| Sugarbeets |

41 |

compatible |

| Dry Beans |

42 |

compatible |

| Potatoes |

43 |

compatible |

| Other Crops |

44 |

compatible |

| Sugarcane |

45 |

incompatible |

| Sweet Potatoes |

46 |

compatible |

| Misc Vegs & Fruits |

47 |

compatible |

| Watermelons |

48 |

compatible |

| Onions |

49 |

compatible |

| Cucumbers |

50 |

compatible |

| Chick Peas |

51 |

compatible |

| Lentils |

52 |

compatible |

| Peas |

53 |

compatible |

| Tomatoes |

54 |

compatible |

| Caneberries |

55 |

incompatible |

| Hops |

56 |

incompatible |

| Herbs |

57 |

compatible |

| Clover/Wildflowers |

58 |

compatible |

| Sod/Grass Seed |

59 |

compatible |

| Switchgrass |

60 |

compatible |

| Fallow/Idle Cropland |

61 |

compatible |

| Pasture/Grass |

62 |

compatible |

| Forest |

63 |

incompatible |

| Shrubland |

64 |

incompatible |

| Barren |

65 |

compatible |

| Cherries |

66 |

incompatible |

| Peaches |

67 |

incompatible |

| Apples |

68 |

incompatible |

| Grapes |

69 |

incompatible |

| Christmas Trees |

70 |

incompatible |

| Other Tree Crops |

71 |

incompatible |

| Citrus |

72 |

incompatible |

| Pecans |

74 |

incompatible |

| Almonds |

75 |

incompatible |

| Walnuts |

76 |

incompatible |

| Pears |

77 |

incompatible |

| Clouds/No Data |

81 |

incompatible |

| Developed |

82 |

incompatible |

| Water |

83 |

compatible |

| Wetlands |

87 |

compatible |

| Nonag/Undefined |

88 |

incompatible |

| Aquaculture |

92 |

incompatible |

| Open Water |

111 |

incompatible |

| Perennial Ice/Snow |

112 |

incompatible |

| Developed/Open Space |

121 |

incompatible |

| Developed/Low Intensity |

122 |

incompatible |

| Developed/Med Intensity |

123 |

incompatible |

| Developed/High Intensity |

124 |

incompatible |

| Barren |

131 |

incompatible |

| Deciduous Forest |

141 |

incompatible |

| Evergreen Forest |

142 |

incompatible |

| Mixed Forest |

143 |

incompatible |

| Shrubland |

152 |

incompatible |

| Grassland/Pasture |

176 |

compatible |

| Woody Wetlands |

190 |

incompatible |

| Herbaceous Wetlands |

195 |

compatible |

| Pistachios |

204 |

incompatible |

| Triticale |

205 |

compatible |

| Carrots |

206 |

compatible |

| Asparagus |

207 |

compatible |

| Garlic |

208 |

compatible |

| Cantaloupes |

209 |

compatible |

| Prunes |

210 |

incompatible |

| Olives |

211 |

incompatible |

| Oranges |

212 |

incompatible |

| Honeydew Melons |

213 |

compatible |

| Broccoli |

214 |

compatible |

| Avocados |

215 |

incompatible |

| Peppers |

216 |

compatible |

| Pomegranates |

217 |

incompatible |

| Nectarines |

218 |

incompatible |

| Greens |

219 |

compatible |

| Plums |

220 |

incompatible |

| Strawberries |

221 |

compatible |

| Squash |

222 |

compatible |

| Apricots |

223 |

incompatible |

| Vetch |

224 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Corn |

225 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Oats/Corn |

226 |

compatible |

| Lettuce |

227 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Triticale/Corn |

228 |

compatible |

| Pumpkins |

229 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Durum Wht |

230 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Cantaloupe |

231 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Cotton |

232 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Lettuce/Barley |

233 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Durum Wht/Sorghum |

234 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Sorghum |

235 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Sorghum |

236 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Corn |

237 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop WinWht/Cotton |

238 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Soybeans/Cotton |

239 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Soybeans/Oats |

240 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Corn/Soybeans |

241 |

compatible |

| Blueberries |

242 |

incompatible |

| Cabbage |

243 |

compatible |

| Cauliflower |

244 |

compatible |

| Celery |

245 |

compatible |

| Radishes |

246 |

compatible |

| Turnips |

247 |

compatible |

| Eggplants |

248 |

compatible |

| Gourds |

249 |

compatible |

| Cranberries |

250 |

compatible |

| Dbl Crop Barley/Soybeans |

254 |

compatible |

References

- Ballard, B. M., and J. E. Thompson. 2000. Winter diets of sandhill cranes from central and coastal Texas. The Wilson Bulletin 112:263-268. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Methodological 57(1):289-300. <. [CrossRef]

- Caven, A.J. 2023. An updated minimum estimate of the global Sandhill Crane population. Platte River Natural Resources Reports eJournal 2:1-14.

- Cleveland, W. S., E. Grosse, and W. M. Shyu. 1992. Local regression models. Chapter 8 in S. J.M. Chambers and T.J. Hastie, editors, Statistical Models. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Collins, D. P., M. A. Boggie, K. L. Kruse, C. M. Conring, J. P. Donnelly, W. C. Conway, and B. A. Grisham. 2023. Roost sites influence habitat selection of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis tabida) in Arizona and California. Waterbirds 45(4):428-439. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. A. 2003. Habitat use and migration patterns of sandhill cranes along the Platte River, 1998-2001. Great Plains Research 13:199-216.

- Esri. 2025. ArcGIS Pro (version 3.5). Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, California, USA.

- Central Valley Joint Venture. 2020. Central Valley Joint Venture 2020 Implementation Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, CA, USA. <. www.centralvalleyjointventure.org>.

- Foster, M. A., M. J. Gray, and R. M. Kaminski. 2010. Agricultural seed biomass for migrating and wintering waterfowl in the Southeastern United States. Journal of Wildlife Management 74:489-495. [CrossRef]

- Great Valley Center. 2005. The state of the Great Central Valley of California: the economy. Great Valley Center, Modesto, CA, USA. <http://www.greatvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/2nd_2005_Economy.pdf>.

- Hemminger, K., H. König, J. Månsson, S. D. Bellingrath--Kimura, and L. Nilsson. 2022. Winners and losers of land use change: A systematic review of interactions between the world’s crane species (Gruidae) and the agricultural sector. Ecology and Evolution 12(3):e8719. [CrossRef]

- Iverson, G. C., P. A. Vohs and T. C. Tacha. 1985. Habitat use by sandhill cranes wintering in western Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management 49:1074–1083. [CrossRef]

- Ivey, G.L. 2014. Greater Sandhill Crane; Lesser Sandhill Crane. Pages 96-97 (appendix 4) in Shuford, W. D., editor, Coastal California (BCR 32) Waterbird Conservation Plan: Encompassing the coastal slope and coast ranges of central and southern California and the Central Valley. A plan associated with the Waterbird Conservation for the Americas initiative. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Ivey, G. L. 2015. Comparative wintering ecology of two subspecies of sandhill crane: informing conservation planning in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta Region of California. Ph.D. dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

- Ivey, G. L., B. D. Dugger, C. P. Herziger, M. L. Casazza, and J. P. Fleskes. 2014b. Characteristics of sandhill crane roosts in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta of California. Proceedings of the North American Crane Workshop 12:12-19.

- Ivey, G. L., C. P. Herziger, and D. A. Hardt. 2014a. Conservation priorities and best management practices for wintering Sandhill Cranes in the Central Valley of California. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy of California. International Crane Foundation. Baraboo, WI, USA.

- Ivey, G. L., B. D. Dugger, C. P. Herziger, M. L. Casazza, and J. P. Fleskes. 2015. Wintering ecology of sympatric subspecies of sandhill crane: Correlations between body size, site fidelity, and movement patterns. Condor 117:518-529. [CrossRef]

- Ivey, G. L., B. D. Dugger, C. P. Herziger, M. L. Casazza, and J. P. Fleskes. 2025. Habitat use by sandhill cranes wintering in the agricultural landscape of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta of California. Proceedings of the North American Crane Workshop 16:14-34.

- Ivey, G.L., C.P. Herziger, D.A. Hardt, and G.H. Golet. 2016. Historic and recent winter sandhill crane distribution in California. Proceedings of the North American Crane Workshop 13:54-66.

- Johnson, H. P., and Hayes, J. M. 2004. The Central Valley at a crossroads: Migration and its implications. Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco, CA, USA. <www.dcfn.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_1104HJR.pdf>.

- Kendall, M. 1975. Rank correlation measures. Charles Griffin and Company, London, England.

- Kim, J. H., S. Park, S. H. Kim, and E. J. Lee.2021. Identifying high-priority conservation areas for endangered waterbirds using a flagship species in the Korean DMZ. Ecological Engineering 159:106080. [CrossRef]

- Krapu, G. L., D. E. Facey, E. K. Fritzell and D. H. Johnson. 1984. Habitat use by migrant sandhill cranes in Nebraska. Journal of Wildlife Management 48:407–417. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W. H., and W. A. Wallis. 1952. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 47:583-621. [CrossRef]

- Leu, M., Hanser, S. E., and Knick, S. T. 2006. The human footprint in the West: A large-scale analysis of anthropogenic impacts. Ecological Applications 18:1119–1139. [CrossRef]

- Littlefield, C. D. 2002. Winter foraging habitat of greater sandhill cranes in northern California. Western Birds 33:51-60.

- Littlefield, C. D., and G. L. Ivey. 2002. State of Washington Sandhill Crane Recovery Plan. Prepared for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Program, Wildlife Diversity Division, Olympia, WA. 48 pp. + appendices. https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/00396.

- Littlefield, C. D., and S. P. Thompson. 1979. Distribution and status of the Central Valley Population of greater sandhill cranes. Pages 113-120 in Proceedings 1978 Crane Workshop. J. C. Lewis, editor. Colorado State University Print Services, Fort Collins, CO, USA.

- Lovvorn, J. R. and C. M. Kirkpatrick. 1982. Field use by staging eastern greater sandhill cranes. Journal of Wildlife Management 46:99–108. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. 1945. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13:245-259.

- McLeod, A. 2022. Kendall: Kendall Rank Correlation and Mann-Kendall Trend Test. R package version 2.2.1, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Kendall>.

- Nelder, J. A., and R. W. Wedderburn. 1972. Generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 135(3):370-384.

- Ogle, D.H., J.C. Doll, A.P. Wheeler, A. Dinno. 2025. _FSA: Simple Fisheries Stock Assessment Methods_. R package version 0.10.0. <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FSA>.

- Pacific Flyway Council. 1997. Pacific Flyway management plan for the Central Valley population of greater sandhill cranes. Pacific Flyway Study Committee, (c/o Division of Migratory Bird Management, Pacific Flyway Representative USFWS], Vancouver, WA. USA.

- Pacific Flyway Council. 2020. Status Review for the Pacific Coast Population of Sandhill Cranes. Pacific Flyway Council, (c/o Division of Migratory Bird Management, Pacific Flyway Representative USFWS], Vancouver, WA. USA.

- Pandolfino, E.R., and L.A. Douglas. 2022. Continuing declines of grassland birds in California’s Central Valley. Central Valley Birds 25:93-111.

- Pandolfino, E. R., and C. M. Handel. 2018. Population trends of birds wintering in the Central Valley of California, in Trends and traditions: Avifaunal change in western North America. Pages 215–235 in W. D. Shuford, R. E. Gill Jr., and C. M. Handel, editors, Studies of Western Birds 3. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, CA, USA.

- Pearse, A. T., G. L. Krapu, and D. A. Brandt. 2017. Sandhill crane roost selection, human disturbance, and forage resources. The Journal of Wildlife Management 81(3):477-486. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2024. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/>.

- Rehman, S. 2013. Long-term wind speed analysis and detection of its trends using Mann–Kendall test and linear regression method. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 38:421-437. [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, K. J., and G. L. Krapu. 1986. Feeding ecology of sandhill cranes during migration in Nebraska. Journal of Wildlife Management 50:71-79. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R.Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P.P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366(6461):120-124. [CrossRef]

- Shaskey, L. E. 2012. Local and landscape influences on sandhill crane habitat suitability in the northern Sacramento Valley, CA. M.S Thesis, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA, USA.

- Shuford, W. D., and Gardali, T., editors. 2008. California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California, and California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Sacramento, California, USA.

- Shuford, W. D., author and editor. 2014. Coastal California (BCR 32) Waterbird Conservation Plan: Encompassing the coastal slope and Coast Ranges of central and southern California and the Central Valley. A plan associated with the Waterbird Conservation for the Americas initiative. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Shuford, W.D. and Dybala, K.E., 2017. Conservation objectives for wintering and breeding waterbirds in California’s Central Valley. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 15(1):4. <https://escholarship.org/content/qt5tp5m718/qt5tp5m718.pdf>. [CrossRef]

- Sparling, D. W., and G. L. Krapu. 1994. Communal roosting and foraging behavior of staging sandhill cranes. Wilson Bulletin 106:62-77.

- Sullivan, B. L., C. L. Wood, M. J. Iliff, R. E. Bonney, D. Fink, and S. Kelling. 2009. eBird: a citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation 142:2282-2292. [CrossRef]

-

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), 20240131, Cropland Data Layer: USDA NASS, USDA NASS Marketing and Information Services Office, Washington, D.C., USA. <https://croplandcros.scinet.usda.gov/> .

- Venables, W. N., and B. D. Ripley. 2002. Modern Applied Statistics with S. New York: Springer.

- Wiens, J.A., and T. Gardali. 2013. Conservation reliance among California’s at-risk birds. Condor 115:456-464. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. S., E. Matchett, K. B. Byrd, E. Conlisk, M. E. Reiter, C. Wallace, L. E. Flint, A. L. Flint, B. Joyce, and M. M. Moritsch. 2022. Climate and land change impacts on future managed wetland habitat: a case study from California’s Central Valley. Landscape Ecology 37(3):861-881. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., R. Jia, H. Lv, G. Sun, D. Liu, H. Yu, H., C. Ma, T. Ma, W. Deng, and G. Zhang. 2025. Habitat suitability and influencing factors of a threatened highland flagship species, the Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis). Avian Research16(2):100243. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).