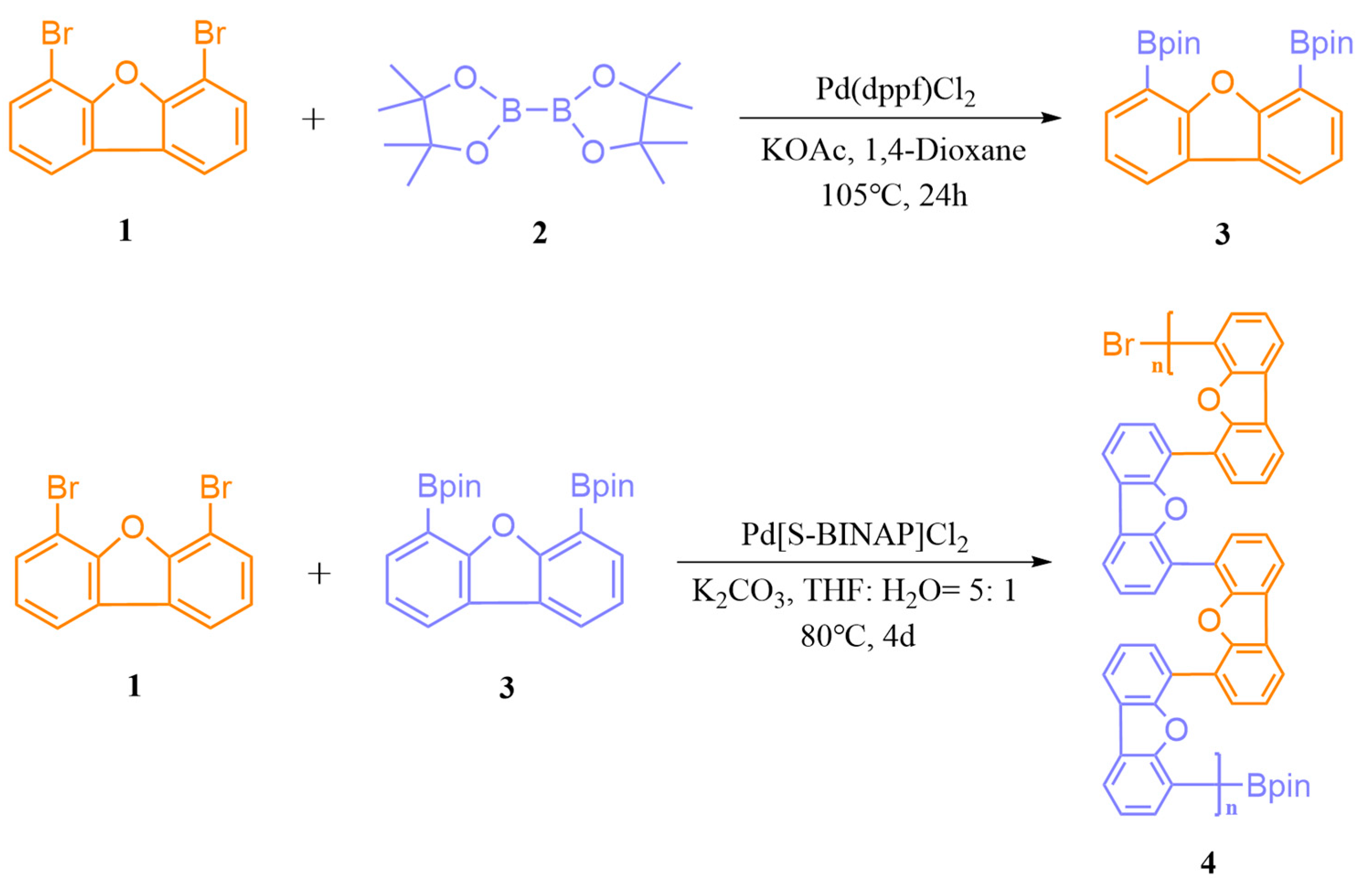

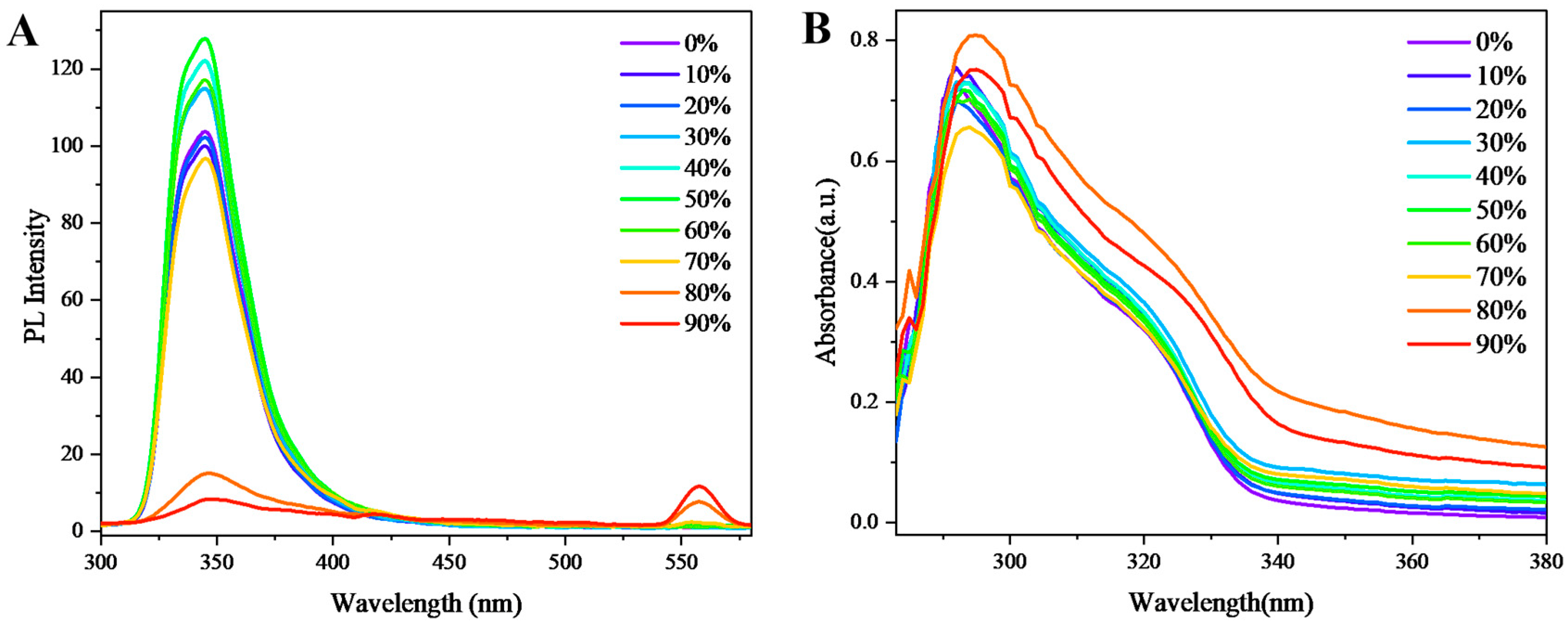

3.2. Characteristics of UV-Vis Absorption and Photoluminescence

Figure 3A presents the fluorescence emission spectra of chiral polymer 4 in mixed solvent systems with varying water/tetrahydrofuran (THF) ratios. The data reveal a distinct aggregation-induced emission (AIE) phenomenon: as the water fraction increases from 0% to 50%, the fluorescence intensity shows a progressive enhancement. This observation can be attributed to restricted aromatic ring rotation upon molecular aggregation, which effectively reduces non-radiative transition pathways while maintaining radiative transition rates, thereby amplifying fluorescence emission. Notably, when the water content exceeds 60%, the fluorescence intensity undergoes gradual attenuation, reaching near-complete quenching at 90% water fraction. This quenching behavior likely results from intermolecular electron coupling in the aggregated state, which facilitates the formation of new excited states that promote non-radiative decay. Interestingly, at water fractions of 80% and 90%, a distinct emission peak emerges at 560 nm, possibly originating from vibronic transitions between different energy levels in the excited state.

Figure 3B displays the UV-vis absorption spectra of polymer 4 under identical solvent conditions while maintaining constant polymer concentration. The spectra demonstrate remarkable consistency across different water fractions, with negligible variations in both absorbance and spectral profile. This consistency indicates that the polymer's fundamental conformation remains largely unaffected by solvent composition. However, careful examination reveals two subtle yet significant trends: (1) a minor bathochromic shift of the absorption maximum with increasing water content, suggesting slight electronic structure modifications and reduced molecular orbital energies; and (2) a modest absorbance enhancement beyond 300 nm at higher water fractions, reflecting weak AIE behavior through enhanced molecular packing. These spectroscopic changes collectively reflect the unique structural characteristics of polymer 4. Particularly, the strategic arrangement of benzofuran units in its multilayer architecture facilitates strong intermolecular interactions and efficient π-stacking, which are crucial for promoting the observed AIE effects.

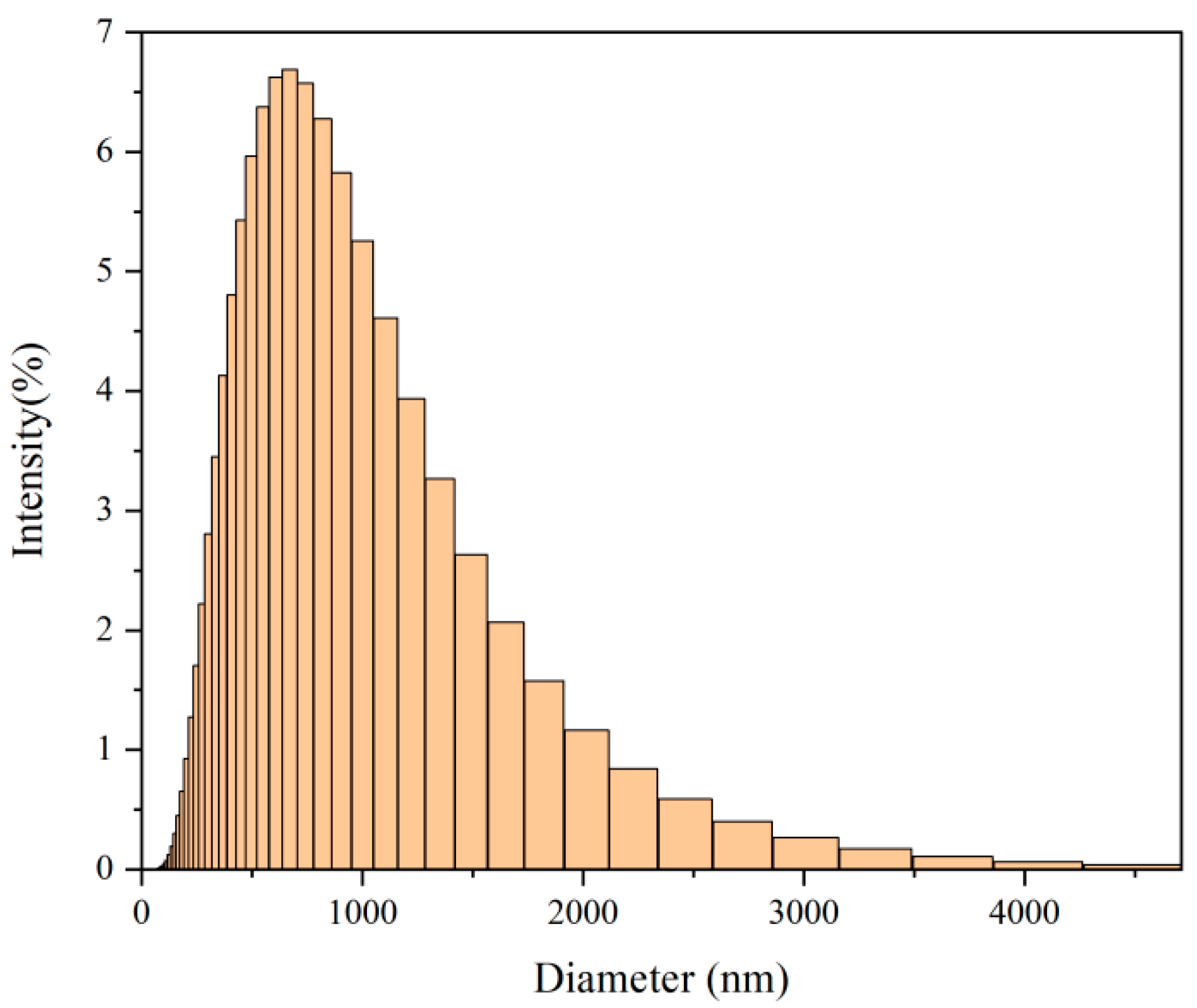

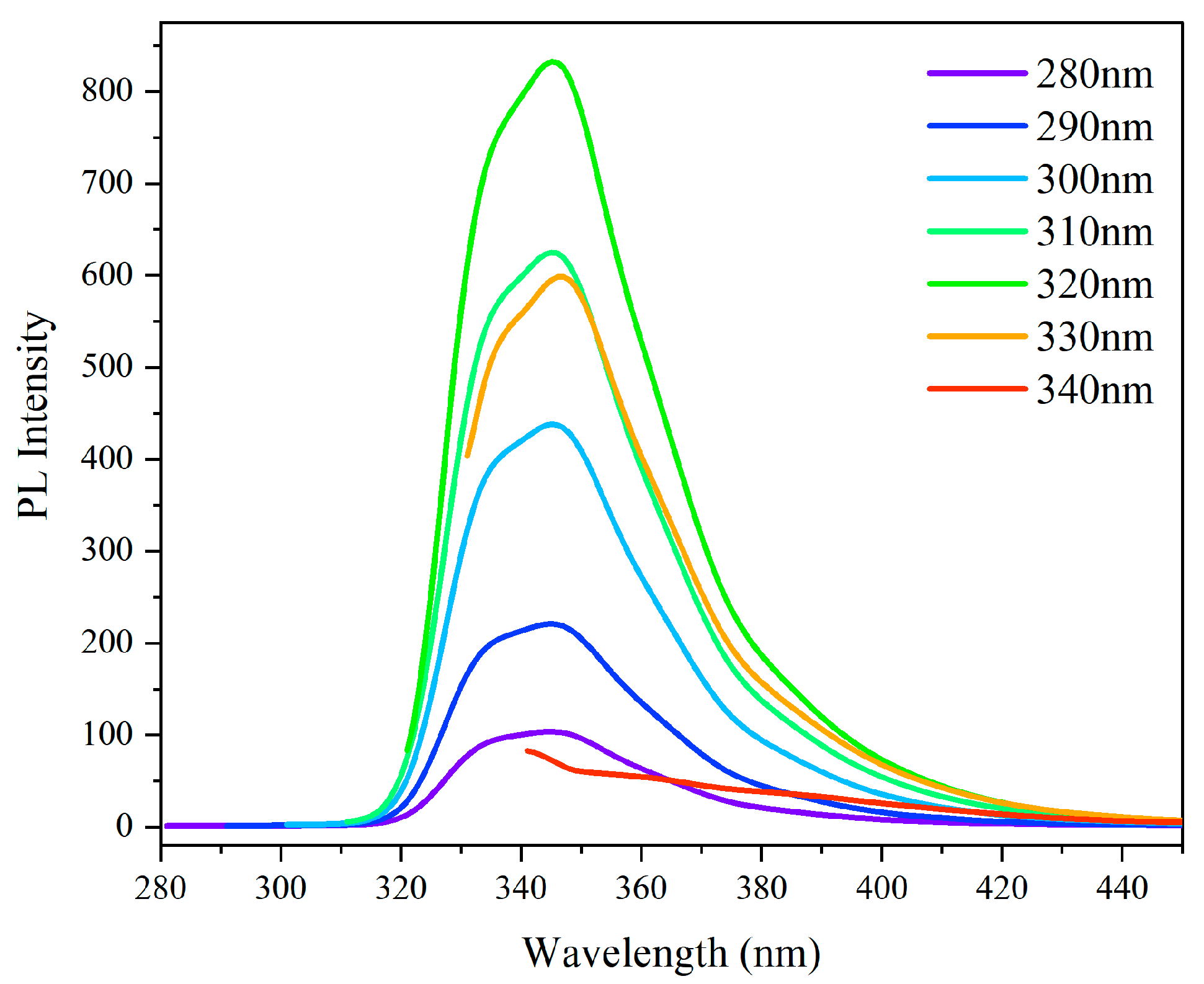

Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy is a versatile analytical technique with high sensitivity and selectivity, enabling real-time metal ion detection in complex matrices and advancing applications in environmental monitoring and biomedical imaging. The integration of chiral polymers enhances its specificity and responsiveness, fostering innovations in sensing platforms and expanding its potential in materials science and photonics. The analysis presented in

Figure 3 demonstrates that Polymer 4 displays distinct aggregation-induced emission (AIE) characteristics under specific conditions. Photoluminescence spectral analysis was conducted across an excitation wavelength range of 280-340 nm. As illustrated in

Figure 4, Polymer 4 exhibits maximum emission intensity at approximately 340 nm, with the absorption peak position remaining constant regardless of excitation wavelength (i.e., neither significant red-shift nor blue-shift is observed). Notably, the fluorescence intensity shows a progressive enhancement as the excitation wavelength increases from 280 nm to 320 nm, followed by a sharp decrease at longer wavelengths, reaching its minimum at 340 nm. These collective observations conclusively demonstrate the AIE properties of Polymer 4, which are specifically characterized by enhanced absorption and photoluminescence under particular excitation conditions. This systematic investigation provides fundamental insights into the photophysical mechanisms underlying the AIE phenomenon in this polymeric system.

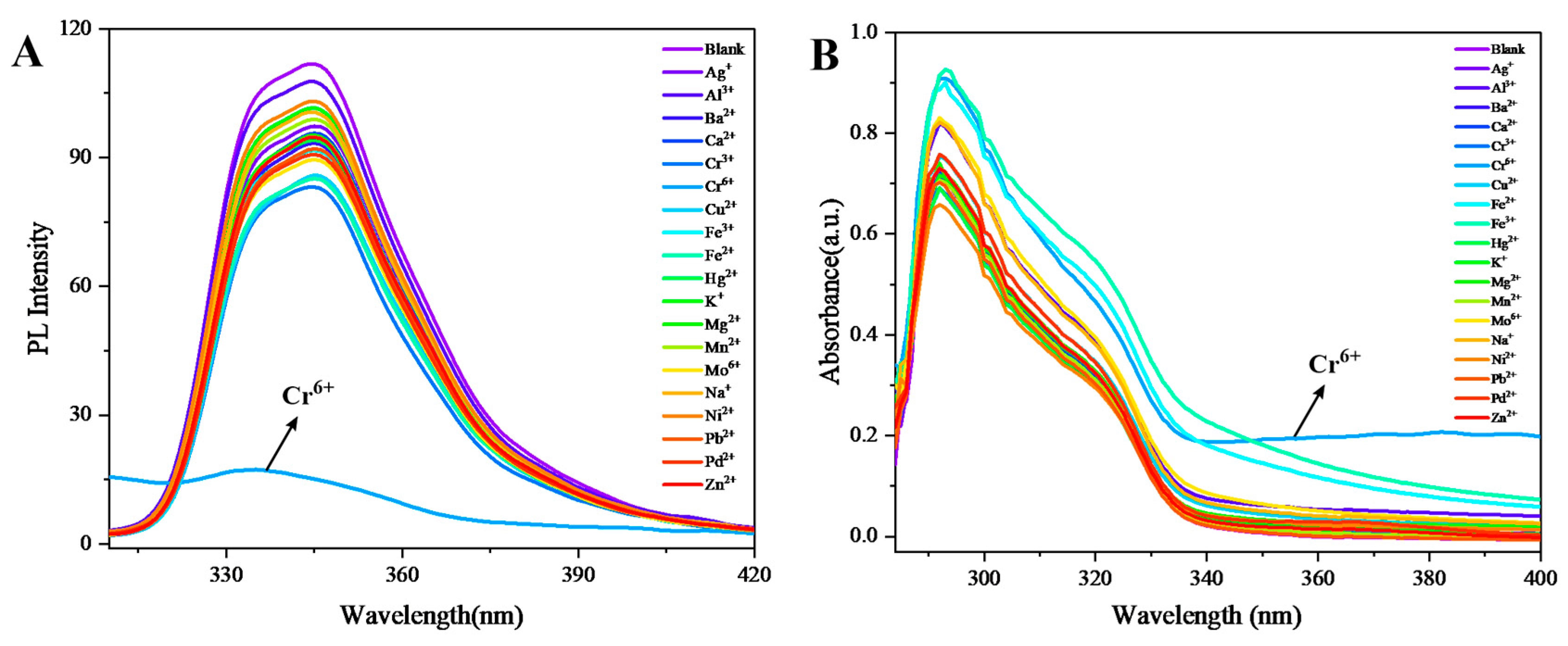

In the investigation of fluorescent probes, the photoluminescence (PL) response of multilayer three-dimensional polymer 4 toward diverse metal ions was systematically assessed (

Figure 5A). Notably, the PL intensity of polymer 4 remained largely unaffected in the presence of multiple metal ions, including Ag⁺, Al³⁺, Ba²⁺, Ca²⁺, Cr³⁺, Cu²⁺, Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺, Hg²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺, Mo⁶⁺, Na⁺, Ni²⁺, Pb²⁺, Pd²⁺, and Zn²⁺, demonstrating its stable emission properties under various ionic conditions. However, a distinct fluorescence quenching effect was observed upon the introduction of Cr⁶⁺ ions, leading to a pronounced decrease in emission intensity. This quenching phenomenon can be attributed to the selective complexation between Cr⁶⁺ and polymer 4, which perturbs the molecular energy level transitions. Specifically, the interaction facilitates non-radiative decay pathways, thereby suppressing fluorescence emission. These results highlight the differential influence of metal ions on the photophysical behavior of polymer 4, with Cr⁶⁺ exhibiting a unique quenching capability. Such selectivity underscores the potential of polymer 4 as a sensitive probe for Cr⁶⁺ detection in analytical applications.

To assess the fluorescent probe characteristics of multilayer 3D polymer 4, its optical properties were examined via UV-Vis spectroscopy (

Figure 5B). The UV-Vis spectra revealed minimal alterations in absorbance and spectral profile upon the introduction of various metal ions, including Ag⁺, Al³⁺, Ba²⁺, Ca²⁺, Cr³⁺, Cu²⁺, Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺, Hg²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺, Mo⁶⁺, Na⁺, Ni²⁺, Pb²⁺, Pd²⁺, and Zn²⁺, with the spectra closely resembling that of the blank sample. In contrast, a distinct spectral modification was observed upon the addition of Cr⁶⁺, characterized by a pronounced tailing effect beyond 340 nm and a marked increase in absorbance. This phenomenon likely arises from valence electron transitions induced by the interaction between Cr⁶⁺ and polymer 4, suggesting a selective perturbation of the electronic structure. These findings underscore the unique responsiveness of polymer 4 to Cr⁶⁺, highlighting its potential as a selective optical sensor for hexavalent chromium detection.

In addition to Cr⁶⁺, the selectivity of polymer 4 was investigated by introducing a Cr⁶⁺ solution into systems containing various competing metal ions, including Ag⁺, Al³⁺, Ba²⁺, Ca²⁺, Cr³⁺, Cu²⁺, Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺, Hg²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺, Mo⁶⁺, Na⁺, Ni²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Zn²⁺ (

Figure 6). Upon addition of Cr⁶⁺ to these metal ion solutions, all systems exhibited a significant reduction in fluorescence intensity. This observation suggests a strong interaction between polymer 4 and Cr⁶⁺, which interferes with molecular energy-level transitions. Specifically, the excited-state molecular transitions were perturbed, leading to fluorescence quenching.

The fluorescence quenching ratio (FQR), defined as the ratio of fluorophore intensity in the presence versus absence of a quencher, was quantitatively determined through spectral analysis. This parameter, which depends on experimental conditions and fluorophore characteristics, is widely employed in materials science to optimize fluorescent probe performance and detection limits. As shown in

Figure 6B, the FQR of polymer 4 was evaluated both in the presence of different metal ions and after subsequent introduction of Cr⁶⁺. All measured FQR values were below 1, indicating varying degrees of fluorescence quenching across the tested metal ions. Notably, upon Cr⁶⁺ addition, the FQR dropped below 0.2, reflecting a dramatic decrease in fluorescence intensity and demonstrating pronounced quenching. This result confirms the exceptional selectivity of polymer 4 for Cr⁶⁺, consistent with its ability to disrupt molecular energy-level transitions, as previously discussed.

The remarkable selectivity of Polymer 4 for Cr⁶⁺ ions stems from the distinctive structural characteristics of its multi-layered three-dimensional polymeric architecture. Experimental and computational studies reveal that benzofuran units play a pivotal role in this selective recognition process. The heterocyclic oxygen atom in the benzofuran ring not only provides additional coordination sites but also enables specific binding to Cr⁶⁺ through combined steric and electronic effects. In aqueous media, when these functional units are covalently incorporated into the polymer backbone, Cr⁶⁺ ions preferentially form stable coordination complexes with benzofuran moieties, leading to characteristic fluorescence quenching. This exceptional selective recognition capability endows such polymers with significant application potential in environmental heavy metal monitoring, particularly for distinguishing Cr⁶⁺ from other coexisting metal ions in complex aqueous systems. The successful design of this polymeric system provides a novel molecular platform for developing highly selective and sensitive heavy metal ion sensors, representing an important advancement in the application of functional polymers in environmental analytical chemistry.

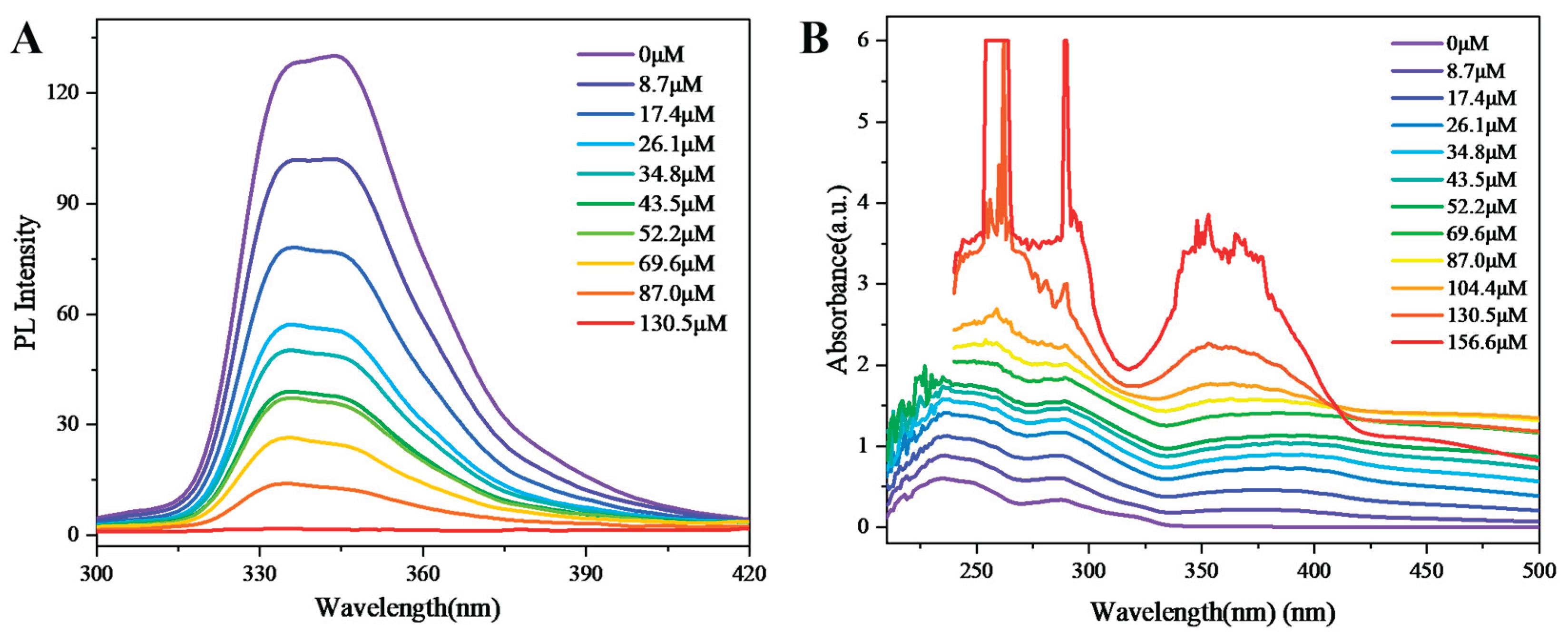

The comprehensive analysis reveals that chiral multilayer 3D polymer 4 demonstrates high sensitivity toward Cr⁶⁺ ions, as evidenced by concentration-dependent fluorescence quenching studies (

Figure 7). Upon incremental addition of Cr⁶⁺ (0–130.5 μM), the fluorescence intensity of polymer 4 progressively decreases, reaching near-complete quenching at 130.5 μM (

Figure 7A). The quenching profile exhibits a nonlinear Stern-Volmer relationship, characterized by a steep initial response at low Cr⁶⁺ concentrations (<50 μM), followed by a plateau at higher concentrations. This biphasic behavior suggests static quenching via ground-state complexation, likely due to coordination between Cr⁶⁺ and electron-rich functional groups within the polymer scaffold. The rapid initial quenching indicates strong binding affinity, consistent with Cr⁶⁺-selective chelation, while the subsequent saturation reflects limited binding-site availability. Notably, the detection threshold (<1 μM) aligns with environmental Cr⁶⁺ limits, highlighting polymer 4’s potential for real-world monitoring. The retained chirality during quenching further supports structural stability, a critical feature for reproducible sensing.

Figure 7B demonstrates that the absorbance of polymer 4 increases progressively with rising Cr⁶⁺ concentration. Notably, above 130.5 μM, distinct high-intensity absorption peaks emerge, accompanied by a pronounced decline in absorbance beyond 400 nm compared to lower concentrations. This trend aligns with the overall concentration-dependent response observed in Figure 9D. At low Cr⁶⁺ concentrations (<69.6 μM), the absorbance exhibits a near-linear correlation with concentration, where increased chromophore interactions enhance photon absorption. Beyond 69.6 μM, the incremental absorbance diminishes, likely due to detector saturation or near-complete incident light absorption, limiting measurable signal amplification. The emergence of intense peaks at high concentrations suggests aggregation-induced spectral shifts or excitonic coupling, phenomena documented in π-conjugated polymer-metal systems.

Conclusion

This study successfully constructed a novel three-dimensional chiral polymer material with aggregation-induced emission characteristics via Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions. Comprehensive structural characterization and photophysical measurements (including steady-state/time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy and UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy) demonstrated that this material exhibits a unique "off-on" fluorescence response to heavy metal ions (especially Cr6+), with a detection limit reaching nanomolar levels while maintaining excellent selectivity in the presence of various interfering ions. These outstanding detection capabilities highlight its significant potential for complex environmental sample analysis, providing new perspectives for developing green analytical technologies.

Mechanistic studies reveal that the sensing performance originates from the precisely regulated molecular conformation and electronic structure of this AIE-active polymer. Compared with conventional sensors, this material not only offers advantages of operational simplicity and rapid response but also demonstrates good environmental compatibility. More importantly, the design strategy provides theoretical guidance for developing new-generation environmental monitoring sensors, enabling accurate pollutant detection while offering technical support for ecological protection and public health. The functional polymer materials developed in this work show broad application prospects in both environmental analytical chemistry and biomedical detection fields.