Introduction

Nicotine is a highly addictive chiral alkaloid, comprising 2-8% of dry tobacco leaf mass and serving as the primary active compound in traditional tobacco products, e-cigarettes, and nicotine replacement therapies. Its unique chemical structure (liquid alkaloid lacking oxygen atoms) makes it prone to oxidation when exposed to air. Upon consumption, nicotine rapidly enters the bloodstream, triggers nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain, and stimulates dopamine and endogenous opioid release, reinforcing its addictive properties. It also activates the adrenal medulla, elevating heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration, and reinforcing both its psychoactive and physiological impact [

1].

Historically, nicotine was first isolated in 1828 by chemists Wilhelm Posselt and Karl Reimann, with its molecular formula (C

10H

14N

2) resolved by 1843. Tobacco use, however, traces back millennia and has been recorded as early as 1400 BC, serving social, medicinal, and ritualistic roles among indigenous cultures. Occupational exposure to nicotine, such as through contact with wet tobacco leaves, can result in Green Tobacco Sickness (GTS), a condition characterized by acute nausea, dizziness, and vomiting. In a North Carolina study, 25% of field workers experienced GTS during a single growing season, highlighting the potency of cutaneous nicotine absorption [

2].

Acute nicotine exposure also produces immediate symptoms such as nausea, throat irritation, vomiting, gastrointestinal upsetting, and cardiovascular and metabolic effects, including elevated blood sugar and catecholamine levels. Severe poisoning can induce tremors, cyanosis, respiratory paralysis, and death, with estimated adult LD50 ranging from 30 to 60 mg and significantly lower in children.

Chronic nicotine consumption is associated with a spectrum of withdrawal symptoms, including both physical (nausea, increased salivation, shivering) and psychological (anxiety, insomnia, irritability, impaired concentration). Additionally, a long term use correlates with disrupted sleep patterns, increased cravings during specific circadian phases, and heightened relapse rates, especially among shift workers or those with irregular sleep. This suggests a close link between nicotine dependency and circadian rhythm disturbance [

3,

4,

5].

Fruit flies (

Drosophila melanogaster) offer a powerful model for dissecting nicotine’s neurobehavioral effects due to their genetic tractability, rapid lifecycle, and conserved neurotransmitter systems. Exposing flies to volatilized nicotine elicits locomotor hyperactivity and spasmodic movements at low doses and paralysis at higher doses, mirroring the dose dependent stimulant and toxic effects seen in mammals [

6]. Chronic exposure induces a form of tolerance in flies, and molecular pathways such as Dcp2 have been implicated in mediating conditioned locomotor responses to nicotine [

7].

Drosophila has also been used to model developmental nicotine effects, which impair survivability, brain development, and dopaminergic signaling [

8].

Crucially,

Drosophila has been instrumental in circadian rhythm research. Core clock genes (

period,

timeless,

clock,

cycle) form a transcription-translation feedback loop that orchestrates 24 hour cycles of locomotor activity, sleep, and metabolism [

10,

11]. The neuronal network coordinating these rhythms is well mapped. The pigment-dispersing factor (PDF) neurons act as key pacemakers [

11], making flies an ideal system in which to explore how external stimuli like nicotine influence circadian-driven behavior [

12].

Although nicotine’s effects on mammalian circadian systems, such as melatonin suppression and sleep-wake disruption, have been documented [

13], little is known about how nicotine interacts with circadian-behavioral systems in invertebrate models like

Drosophila. Filling this gap could elucidate fundamental addiction mechanisms and circadian regulation using a high-throughput, genetically modifiable system.

This study aims to investigate how different nicotine exposure patterns (gradual conditioning versus sudden administration) influence larval locomotor behavior, stillness, and growth in Drosophila melanogaster. By linking these phenotypic outcomes to circadian-linked behaviors, we seek to provide a novel behavioral framework for addiction research, with potential translational implications for understanding how nicotine disrupts biological rhythms in higher organisms.

Methods

Worm Incubation and Care

Larvae were initially split into three groups with four larvae each: a negative control (0% nicotine), a conditioned group exposed to 0.5 mL of 0.01% nicotine for 48 hours, and a sudden-exposure group. All larvae were maintained in petri dishes for 48 hours. During this period, two larvae in the sudden-exposure group escaped and were excluded from the study. Similarly, one larva in the control group died and another escaped. To account for these losses, the remaining two control larvae were combined with the sudden-exposure group to restore a full group of four. Qualitative observations of larval responsiveness to light and touch stimuli were part of this stage and are later summarized in

Table 1.

Treatment Solution Preparation

After the initial 48-hour incubation, both the conditioned and control groups (n = 4 each group) were subdivided into high-dose (2 mL of 0.01% nicotine) and low-dose (1 mL of 0.01% nicotine) groups. Each subgroup contained two larvae and was transferred into new petri dishes. Due to limited recording equipment, the four subgroups did not receive nicotine dosages simultaneously. The conditioned groups received nicotine 24 hours prior to the sudden-exposure groups and were recorded for 2 of those 24 hours.

During this time, both larvae in the sudden-exposure low-dose subgroup entered cocoons and were excluded from further testing. As a result, the high-dose sudden-exposure subgroup was further split: one larva was assigned to high-dose sudden exposure and the other to low-dose sudden exposure.

Experimentation and Observation

After 24 hours of nicotine administration, conditioned groups were transferred to fresh petri dishes and observed for 2 hours to record withdrawal symptoms. Sudden-exposure groups underwent the same procedure: 24 hours of nicotine treatment followed by 24 hours of withdrawal testing.

Behavioral parameters recorded included locomotion time, inactivity (stillness), average movement speed (in mm/sec), feeding, sleep, and responses to light and touch. Larval size was also measured before and after each major phase (initial 48 hours, nicotine exposure, and withdrawal). Measurements were estimated by comparing larval length against the petri dish diameter. Quantitative summaries of locomotion and speed are presented in

Table 2 and Figure 2, and larval size measurements are summarized in

Table 3.

Data Collection and Analysis

Quantitative data included total motion time, total stillness, and average movement speed during conditioning and withdrawal phases. Motion time was calculated by measuring the distance traveled and dividing by the elapsed time. Stillness was recorded as the total minutes larvae remained immobile during observation videos.

Responses to light were tested using a phone flashlight directed over the petri dish lid, while touch responses were assessed by tapping the side of the dish. These qualitative responses were classified as “strong,” “slightly reduced,” or “sluggish” (

Table 1).

Some data loss occurred due to larval mortality, escape, or metamorphosis into cocoons, resulting in smaller sample sizes. In such cases, estimates were made based on the averages of remaining larvae. Quantitative values were expressed in proportions, and results were visualized in graphs (Figure 2). Statistical analyses included one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests to determine significant group differences.

Results

Qualitative Responses

All four larvae in the negative control group displayed strong responses to both light and touch, showing no unusual qualitative behaviors (

Table 1). In contrast, conditioned larvae exhibited slightly reduced responses, along with mild tremors and restlessness. Low dose conditioned larvae demonstrated reduced nicotine sensitivity, paralleling the tolerance observed in human nicotine addicts.

Sudden-exposure larvae were hyperreactive to light and touch immediately after nicotine administration but became sluggish during withdrawal. High-dose sudden-exposure larvae experienced particularly sharp drops in activity post-nicotine. These responses are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning symptoms, including tremors and erratic movement, and highlight the dangers of abrupt nicotine exposure.

Stillness Patterns

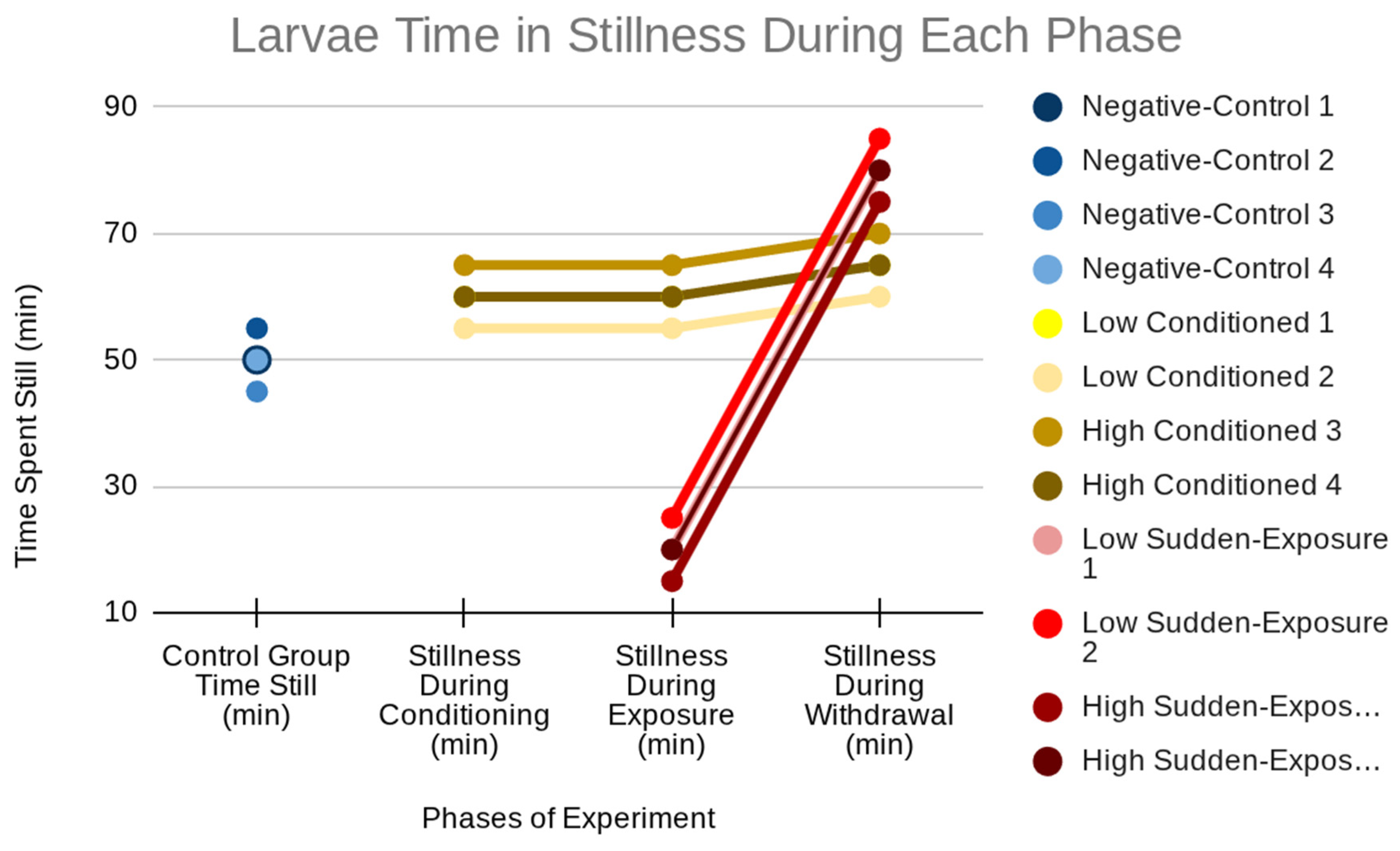

The total time larvae spent in stillness across conditioning, exposure, and withdrawal phases is graphically summarized in

Figure 1. Control larvae maintained relatively consistent stillness (~50–55 minutes) throughout, reflecting stable baseline inactivity. Conditioned larvae showed slightly elevated stillness (~55–65 minutes), particularly during withdrawal, indicating mild suppression from prolonged nicotine exposure. Sudden-exposure larvae, however, displayed a biphasic pattern: stillness dropped dramatically during exposure (~15–25 minutes), consistent with hyperactivity, but increased sharply during withdrawal (~70–90 minutes), surpassing both controls and conditioned larvae. This contrast underscores nicotine’s destabilizing effect, with initial overstimulation followed by pronounced withdrawal-induced inactivity.

Motion and Speed

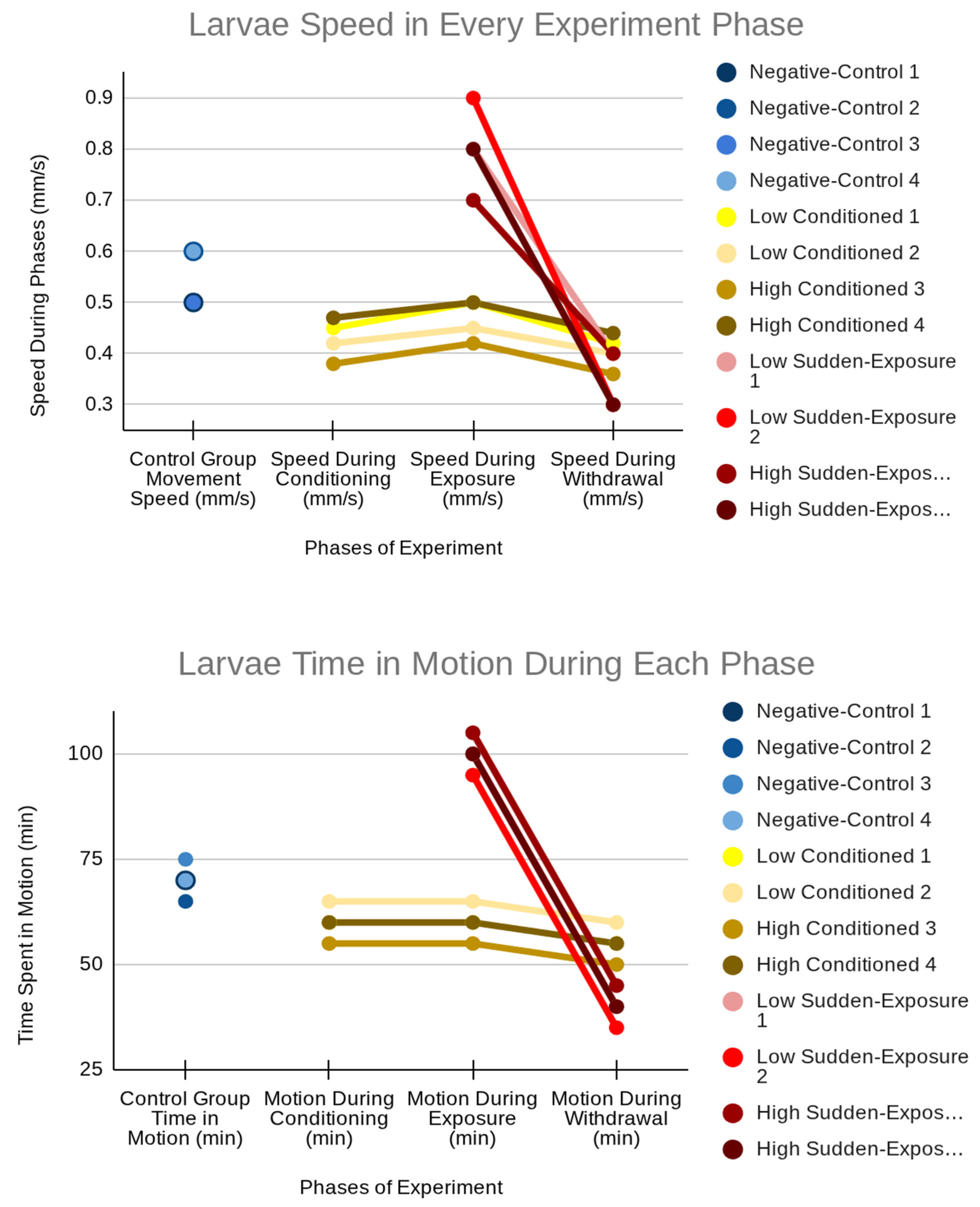

Stillness and movement speed varied substantially across phases of conditioning, exposure, and withdrawal. Control larvae maintained consistent activity, with no stillness observed and stable average speeds (about 0.50 mm/s). Conditioned larvae displayed progressive increases in stillness and modest decreases in speed, especially during withdrawal (

Table 2 and

Figure 2). These findings suggest a cumulative sedative effect of chronic nicotine exposure and tolerance development.

Sudden exposure larvae demonstrated distinct behavioral dynamics: acute hyperactivity during exposure (speeds up to 0.8-0.9 mm/s and motion times of approximately 100 minutes) followed by pronounced suppression in withdrawal (speed about 0.35 mm/s; motion times 35-45 minutes). This biphasic pattern mirrors the human responses to abrupt nicotine intake, signifying an initial hyperactive effect followed by withdrawal lethargy.

Larval Growth

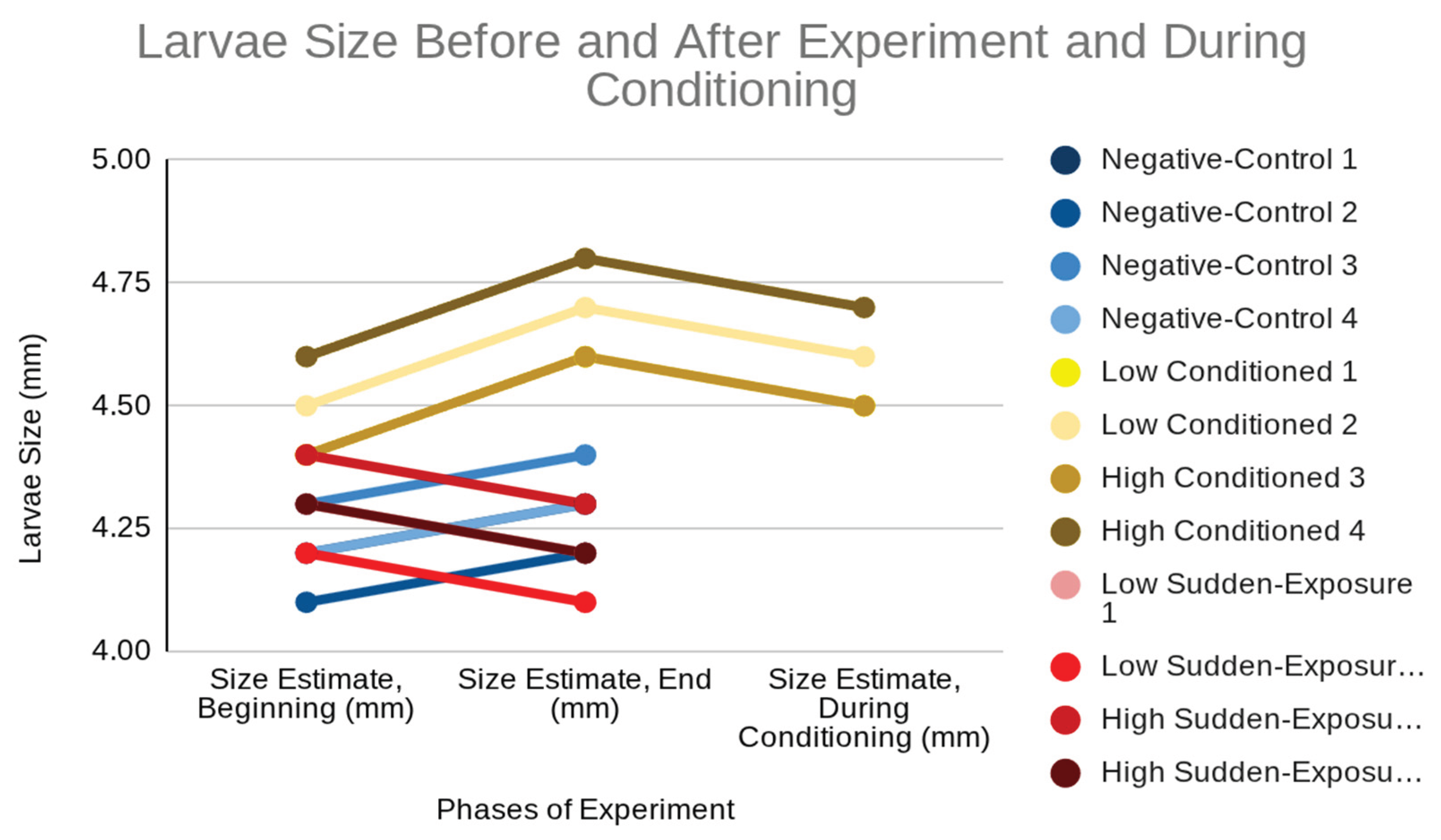

Size measurements revealed consistent growth in control larvae, modest increases in conditioned larvae, and reduced or negative growth in sudden-exposure larvae (

Table 3). The conditioned groups showed increases from about 4.45 mm to 4.65 mm, while sudden exposure larvae decreased slightly in size after treatment, reflecting metabolic stress and impaired development.

Figure 3 visually illustrates these size trends: control larvae maintain steady growth, conditioned larvae increase in size across conditioning and exposure phases, and sudden exposure larvae show flat or downward trajectories after treatment. This visualization shows nicotine’s inhibitory effect on development when administered suddenly, compared to the partial tolerance that allows for modest growth in conditioned larvae.

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA tests confirmed significant group effects for motion and speed during both exposure and withdrawal phases. During exposure, sudden-exposure larvae moved on average 40 minutes longer than both conditioned and control groups (F(2, 9) = 192.000, p < 0.001). During withdrawal, they moved 15 minutes less than conditioned and 20 minutes less than control (F(2, 9) = 39.000, p < 0.001).

Speed analyses showed that sudden-exposure larvae moved significantly faster than both other groups during exposure (F(2, 9) = 49.024, p < 0.001) but became significantly slower during withdrawal (F(2, 9) = 15.356, p = 0.0013). Together, these results confirm robust, phase-specific behavioral effects of nicotine.

Discussion

This study examined how different patterns of nicotine exposure, conditioned versus sudden, affect Drosophila melanogaster larval behavior, locomotion, and development. The results reveal distinct phase-specific outcomes, emphasizing that exposure method and dose crucially influence both behavioral and developmental trajectories.

Interpretation of Behavioral Effects

The qualitative and quantitative behavioral data (Tables 1,2 and Figures 1,2) consistently demonstrated that sudden nicotine exposure caused hyperreactivity during administration followed by lethargy in withdrawal, while conditioned larvae developed partial tolerance with less dramatic shifts. These observations align closely with mammalian studies, where nicotine initially produces stimulant effects via nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation and dopamine release [

1]. Over time, receptor desensitization and homeostatic adaptations reduce sensitivity, explaining the muted responses in conditioned larvae [

14].

In

Drosophila, acute nicotine has been repeatedly shown to increase locomotor activity, while chronic exposure attenuates this effect [

15,

16]. This suggests that the biphasic pattern we observed is evolutionarily conserved across species. Additionally, withdrawal induced sluggishness in larvae parallels reduced motor activity and fatigue in human nicotine withdrawal syndromes [

17]. These parallels strengthen the utility of the fruit fly model for dissecting addiction-related behaviors and tolerance mechanisms.

Developmental and Growth Effects

Growth measurements (

Table 3,

Figure 3) showed clear differences between treatment groups. Control larvae increased steadily in size across the experimental period, while conditioned larvae demonstrated modest but consistent gains. In contrast, sudden exposure larvae exhibited reduced or even negative growth, suggesting that acute nicotine administration disrupts development.

These findings align with prior research showing that developmental nicotine exposure in

Drosophila reduces survival rates, delays pupation, and lowers adult fitness [

8,

16]. Similar results have been observed in vertebrate models, where prenatal nicotine restricts intrauterine growth and impairs organ development [

18]. Mechanistically, nicotine induced oxidative stress and interference with metabolic regulation have been implicated in these outcomes. For example, nicotine has been shown to disrupt mitochondrial function, thereby reducing energy availability for growth [

19].

This study extends these observations by demonstrating that the pattern of nicotine administration (sudden versus conditioned) plays a critical role. Conditioned larvae retained some developmental progress despite nicotine exposure, consistent with partial tolerance or metabolic adaptation. Sudden exposure larvae, however, showed developmental stagnation, emphasizing the heightened toxicity of abrupt high-dose exposure.

Mechanistic and Circadian Context

The disruption of locomotor patterns in this study has significant implications for circadian biology. In

Drosophila, circadian rhythms are tightly linked to locomotor activity through the action of clock genes such as period and timeless [

20]. Nicotine’s ability to elevate or suppress movement at different phases suggests that it may interact with circadian controlled neuronal circuits. Prior research in mammals shows nicotine alters melatonin secretion, disrupts sleep-wake cycles, and modifies clock gene expression [

21]. This raises the possibility that the behavioral changes we observed are not merely motor effects, but also reflect circadian misalignment.

Sleep and circadian disruptions have been extensively documented in human smokers and adolescents who vape nicotine-containing products [

22].

Drosophila provides a genetically tractable system for probing these interactions: previous studies show that disrupting clock neurons alters both nicotine sensitivity and withdrawal responses [

23]. Therefore, our findings may indicate that nicotine contributes to circadian rhythm disorder by acting directly on conserved neuronal pathways that regulate daily cycles of activity.

Comparison with Developmental Nicotine Models

The growth findings in this study (

Table 3,

Figure 3) align with both insect and vertebrate models of developmental nicotine exposure. In

Drosophila, nicotine exposure during larval stages reduces survival, delays pupation, and diminishes adult fitness [

16,

24]. In vertebrates, prenatal nicotine exposure is strongly associated with intrauterine growth restriction, altered lung and brain development, and long term metabolic consequences [

18,

19]. The observation that sudden nicotine exposure caused negative or absent growth, while conditioned larvae maintained modest developmental gains, suggests that tolerance may partially buffer against nicotine’s metabolic toxicity.

This highlights the dual role of the exposure pattern. While gradual conditioning fosters some resilience, abrupt high dose nicotine is particularly detrimental to development. Similar findings in rodent models show that intermittent high-dose nicotine impairs neurodevelopment more severely than low-dose chronic exposure [

25]. Thus, this study adds nuance to the broader literature by emphasizing that the pattern of nicotine administration is as important as the administered volume. This distinction has public health relevance, especially in understanding adolescent initiation of nicotine use, which often involves abrupt, high dose exposures from vaping devices.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The small sample size (n = 4 per group) limits generalizability and statistical power. Larval mortality and unsynchronized metamorphosis further reduced group sizes, requiring averaged estimations. Behavioral and size measurements were taken under controlled laboratory conditions, and size estimates relied on petri dish diameters, which may introduce measurement error. Finally, while locomotor behavior is a useful proxy, direct circadian measurements such as clock gene expression or activity rhythms over multiple days were not assessed. Future work should employ larger sample sizes, automated tracking, and molecular assays to strengthen inference.

Broader Implications

Taken together, these results demonstrate that nicotine’s behavioral and developmental impacts are strongly shaped by the mode of exposure. Conditioned larvae displayed tolerance and modest growth, while sudden exposure larvae exhibited extreme biphasic behavioral shifts and developmental suppression. These findings reinforce the translational utility of Drosophila larvae for modeling nicotine’s addictive and toxic properties, and they point to nicotine as a disruptor of circadian-regulated behavior and growth. Future research should extend these results by examining molecular circadian markers and testing whether protective interventions, such as melatonin supplementation, can buffer the nicotine’s effects.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that nicotine exposure in Drosophila melanogaster larvae produces distinct phase specific effects, with sudden administration leading to acute hyperactivity and withdrawal suppression, and conditioned exposure yielding partial tolerance with modest developmental resilience. Growth inhibition in sudden exposure groups highlights nicotine’s developmental toxicity, while altered locomotor activity underscores its potential to disrupt circadian linked behaviors. These findings validate Drosophila as a model for studying nicotine’s addictive and toxic effects, and future work should investigate molecular circadian pathways and long-term developmental consequences.

References

- Benowitz, N. L. (2010). Nicotine addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(24), 2295–2303. [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T. A., Quandt, S. A., Preisser, J. S., & Norton, D. (2001). The incidence of green tobacco sickness among Latino farmworkers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 43(7), 601–609. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, F. (2019). Smoking, nicotine, and sleep: A review of interrelated mechanisms. Sleep Health, 5(2), 124–131. [CrossRef]

- Ahare, R. (2017). Nicotine use and circadian rhythm disruption. Journal of Substance Use, 22(3), 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., Ryu, S.-H., Lee, B. R., Kim, K. H., Lee, E., & Choi, J. (2019). Effects of smoking and nicotine dependence on sleep quality in young adults. Chronobiology International, 36(5), 634–641. [CrossRef]

- Kaun, K. R., Azanchi, R., Maung, Z., Hirsh, J., & Heberlein, U. (2012). A Drosophila model for alcohol reward. Nature Neuroscience, 15(12), 1546–1551. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q., Zhang, Z., & He, Y. (2012). The Dcp2 gene mediates nicotine-induced locomotor effects in Drosophila. Neuroscience Letters, 528(2), 111–116. [CrossRef]

- Morris, H. R., Rangel, D. R., & Velazquez-Ulloa, N. A. (2018). Chronic developmental nicotine exposure alters dopaminergic signaling in Drosophila. Developmental Neurobiology, 78(8), 847–865. [CrossRef]

- Rosbash, M., Hall, J. C., & Kyriacou, C. P. (1984). Genetic and molecular analysis of circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 49, 213–225. [CrossRef]

- Dubowy, C., & Sehgal, A. (2017). Circadian rhythms and sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics, 205(4), 1373–1397. [CrossRef]

- Helfrich-Förster, C., et al. (1998). The neuroanatomy of the circadian clock in Drosophila. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 402(4), 501–526. [CrossRef]

- De Nobrega, A. K., & Lyons, L. C. (2017). Drosophila as a model for circadian rhythm research. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 965. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K., et al. (2023). Nicotine exposure disrupts melatonin and circadian function. Chronobiology International, 40(5), 620–631. [CrossRef]

- Lotfipour, S., & Leonard, G. (2006). Mechanisms of tolerance in chronic nicotine exposure. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 83(1), 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al. (2016). Nicotine-induced behavioral sensitization in Drosophila. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 145, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Ulloa, N. A. (2017). Developmental nicotine exposure and effects in Drosophila. Journal of Experimental Biology, 220(24), 4351–4361. [CrossRef]

- Heishman, S. J., et al. (2010). Tobacco withdrawal symptoms and behavioral impacts. Psychopharmacology, 210(4), 453–467. [CrossRef]

- Wickström, R. (2007). Effects of nicotine during pregnancy: Human and experimental evidence. Current Neuropharmacology, 5(3), 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Slotkin, T. A. (2004). Cholinergic systems and nicotine toxicity. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 26(5), 609–620. [CrossRef]

- Hardin, P. E. (2011). Molecular genetic analysis of circadian timekeeping in Drosophila. Advances in Genetics, 74, 141–173. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M., et al. (2014). Nicotine alters circadian clock gene expression. Neuropharmacology, 76(Pt B), 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, A. G., Ferro, G. A., & Croft, J. B. (2016). Tobacco use and sleep disturbances among U.S. adults. Preventive Medicine, 93, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J. C., et al. (2010). Disruption of circadian neurons alters nicotine sensitivity in Drosophila. PLoS Genetics, 6(11), e1001149. [CrossRef]

- Riemensperger, T., et al. (2011). Behavioral consequences of developmental nicotine exposure in Drosophila. PLoS ONE, 6(1), e15735. [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Villaça, Y., Seidler, F. J., Qiao, D., & Slotkin, T. A. (2011). Adolescent nicotine exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Brain Research Bulletin, 86(1–2), 25–30. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).