1. Introduction

Caffeine is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances worldwide, naturally present in a variety of foods and beverages. It is rapidly absorbed and distributed throughout the body, reaching peak plasma concentrations 30–120 minutes after oral intake and frequently added to beverages and medications [

1]. The main dietary sources are coffee (robusta and arabica), tea, chocolate, and soft drinks, with coffee being the primary source for adults, while tea and sodas are more common among adolescents [

2]. Besides natural occurrence, caffeine can be synthetically produced, with no molecular difference from the natural form, and is widely added to sodas and energy drinks. It is also found in medications for headaches, colds, and allergies, used in cosmetic treatments, and valued for its ergogenic effects in sports [

3], being also consumed for its effects, including pleasant taste, enhanced focus, and greater physical vitality [

4].

Considered an emerging environmental contaminant and a marker of anthropogenic pollution, caffeine enters sewage systems through widespread use in beverages, personal care products, and pharmaceuticals. It has been detected in treated wastewater, groundwater, drinking water, rainwater, rivers, and lakes, posing a potential threat to aquatic ecosystems [

5].

Caffeine intake is part of daily routines worldwide and has attracted growing scientific interest as a bioactive molecule with both beneficial and adverse effects. It has been shown to influence multiple systems, including the central nervous, urinary, digestive, and respiratory systems [

3]. Some studies indicate that caffeine may reduce levels of anxiety and depression, while other studies have shown that caffeine can enhance learning and memory in tasks where information is passively presented. It has also been found to improve performance in tasks that rely on working memory to some extent [

6]. Moreover, research has shown that caffeine contributes significantly to protecting the brain against different forms of damage, such as neurotoxicity, seizures, and cognitive impairment being rapidly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and distributed throughout the body, including the brain [

7].

Its pervasive use has raised scientific interest due to its complex effects on multiple physiological systems, including the central nervous, cardiovascular, and digestive systems [

8]. While moderate caffeine intake can enhance alertness, cognitive performance, and mood, high doses or chronic exposure have been associated with neurobehavioral disturbances, oxidative stress and developmental toxicity [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Model organisms, particularly zebrafish, have become invaluable for investigating caffeine’s neurotoxic and teratogenic effects due to their genetic similarity to humans, transparent embryos, and rapid development [

13].

The zebrafish is a small freshwater vertebrate, native to the rivers of South Asia [

14], typically 3–4 cm in length, with a lifespan of about two years, whose externally developing, transparent embryos make it genetically accessible and highly versatile as a model organism. Over the past few decades, it has gained popularity in scientific research for studying a wide range of biological processes, particularly in neuroscience [

15].

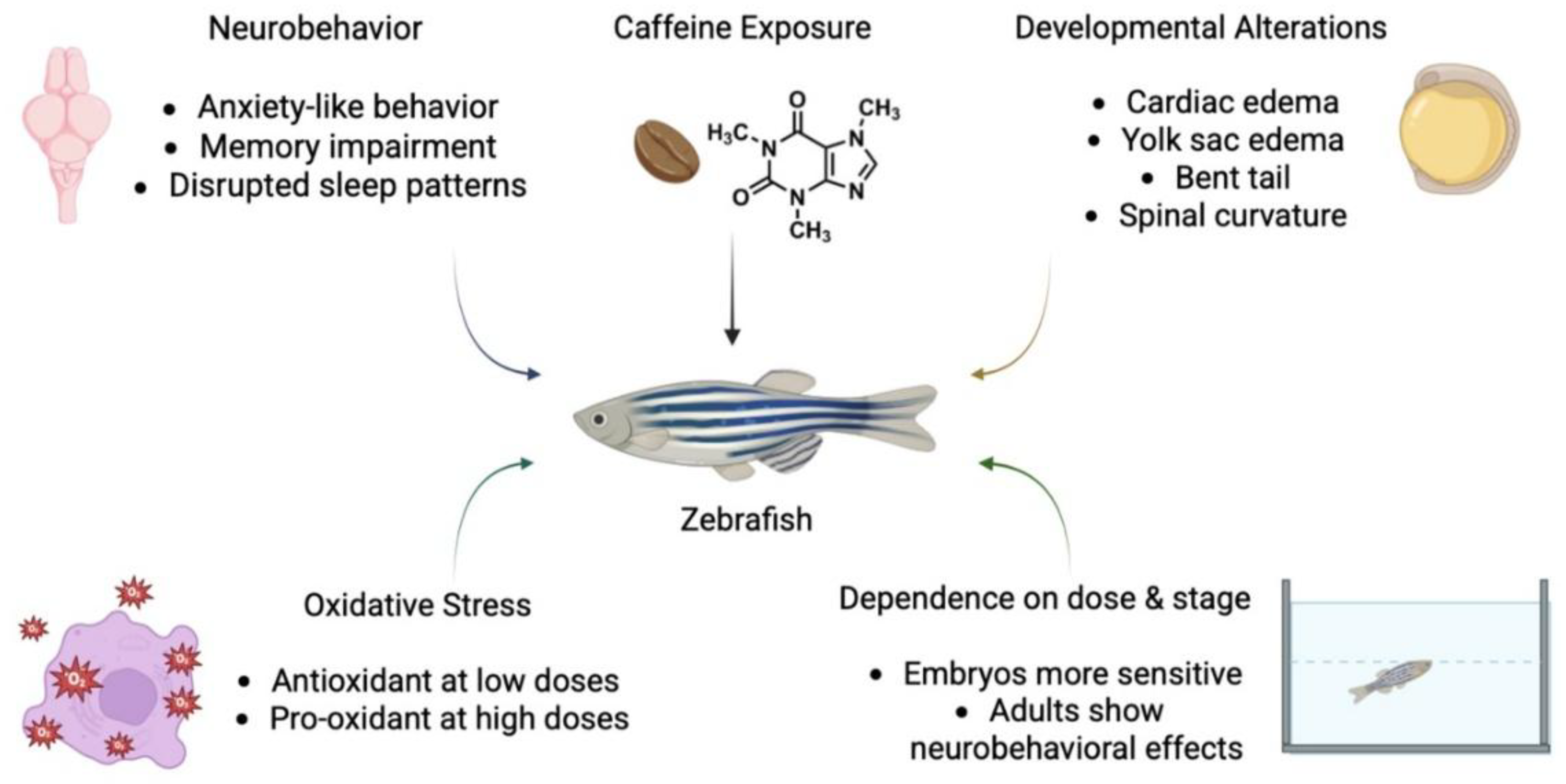

Zebrafish studies have revealed that caffeine can induce anxiety-like behaviors, disrupt sleep patterns, impair memory and neuromuscular development, and cause structural malformations in embryos, highlighting dose-dependent and stage-specific effects [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Caffeine exposure during early zebrafish development can induce a range of dose-dependent alterations, including cardiac and yolk sac edema, bent tails, spinal curvature, and impaired neuromuscular formation. These structural malformations are often accompanied by behavioral deficits such as reduced locomotor activity, disrupted anxiety-like responses, and impaired memory, highlighting the sensitivity of developing embryos to oxidative stress and neurotransmitter imbalances triggered by caffeine [

20,

21].

Moreover, caffeine exposure has been shown to trigger oxidative stress, alter neurotransmitter signaling, and influence developmental pathways, making zebrafish a versatile model for linking molecular mechanisms to observable behavioral and morphological outcomes (

Figure 1) [

22,

23].

This narative rewiew aims to summarize current evidence on caffeine-induced neurobehavioral effects in zebrafish, including anxiety-like behaviors, memory impairment, and disrupted sleep patterns, as well as its impacts on development and oxidative stress, highlighting the dose-dependent effects.

2. Caffeine: Pharmacology and Mechanisms of Action

Caffeine is the most widely consumed stimulant and psychoactive substance, naturally present in more than 60 plant species such as coffee beans, cacao, and tea leaves. Also referred to as guaranine, theine, or mateine depending on its source, caffeine in the form of C

8H

10N

4O

2, chemically known as 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine, is a natural alkaloid from the methylxanthine group, often occurring alongside other bioactive compounds like polyphenols [

7].

Caffeine consumption is an ancient habit, as different cultures historically discovered that chewing seeds, barks, or leaves of caffeine-containing plants alleviated fatigue, enhanced alertness, and elevated mood [

24]. Structurally, caffeine is a heterocyclic organic compound with a purine base called xanthine, composed of a pyrimidine ring linked to an imidazole ring. It is considered a true alkaloid because of the heterocyclic nitrogen atom, although some authors classify it as a pseudo-alkaloid since its biosynthesis does not directly incorporate amino acids [

25].

Caffeine has been shown to improve cognitive performance at low doses, enhancing reaction times and visual information processing. Research indicates that these cognitive benefits can be observed at doses as low as 0.18 mg/kg, with the dose–response relationship plateauing at higher intakes. Furthermore, long-term caffeine consumption appears to induce tolerance, as habitual users often exhibit diminished or absent cognitive effects [

26].

Excessive caffeine consumption can cause health issues such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, hypertension, and gastrointestinal discomfort, emphasizing the need to tailor intake to individual tolerance [

27]. Adverse effects of caffeine increase at high doses (9-13 mg/kg), although physical performance generally remains unaffected [

28]. Intakes around 10-13 mg/kg have been associated with gastrointestinal disturbances, mental confusion, nervousness, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disruption in some individuals [

29], while slightly lower doses (7-10 mg/kg) may cause chills, nausea, flushing, palpitations, headaches, and tremors [

30]. Moderate doses (5-6 mg/kg) preserve ergogenic benefits while reducing, though not completely eliminating, negative side effects and physiological responses. Caffeine doses of 200 mg or higher can lead to toxicosis, presenting as restlessness, insomnia, muscle cramps, and periods of excessive alertness [

31,

32].

Caffeine exerts its effects primarily as a non-selective antagonist of adenosine receptors, which include A

1, A

2A, A

2B, and A

3 subtypes. In the central nervous system, antagonism of A

1 and A

2A receptors reduces inhibitory signaling, leading to increased alertness, decreased fatigue, and enhanced cognitive performance through the indirect facilitation of neurotransmitter release, particularly dopamine and norepinephrine. These mechanisms also modulate mood, attention, and vigilance, while influencing sleep regulation [

33,

34]. Peripherally, caffeine affects cardiovascular and renal function: A1 receptor blockade in the heart increases heart rate, whereas antagonism of renal receptors enhances glomerular filtration and promotes diuresis. A

2A receptor antagonism contributes to coronary vasodilation and can influence pain perception, which is relevant in the context of migraine management [

33]. Beyond these effects, caffeine can activate lipase to promote fat breakdown, modulate muscle contraction to enhance strength, and stimulate gastric acid secretion and gastrin release, supporting digestive processes [

35].

Epidemiological studies further suggest that coffee intake is not associated with increased mortality; on the contrary, modest inverse associations have been described, linked to reduced inflammation, improved endothelial function, and a lower risk of type 2 diabetes [

35,

36]. Regular consumption appears to decrease susceptibility to low-density lipoprotein oxidation, thereby protecting against atherosclerotic plaque formation, while phenolic compounds such as chlorogenic and ferulic acids contribute significant antioxidant capacity. Protective effects have also been observed at the hepatic level, with reduced mortality in women with liver disease or cirrhosis and a lower risk of liver cancer. At the renal level, caffeine enhances natriuresis and diuresis through increased renal blood flow and reduced tubular sodium reabsorption, mechanisms comparable to thiazide diuretics [

35,

37].

Alongside adenosine receptor antagonism, caffeine inhibits phosphodiesterase enzymes, elevating intracellular levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate and cyclic guanosine monophosphate , thereby producing additional effects such as mild bronchodilation, lipolysis, and modulation of intracellular signaling pathways. Following absorption, caffeine is rapidly distributed throughout the body, metabolized primarily in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes, and excreted in the urine as multiple metabolites. Collectively, these central and peripheral actions underlie both the cognitive-enhancing and physiological effects of caffeine, illustrating its complex pharmacological profile [

2,

38].

3. Zebrafish as a Model Organism in Neurotoxicology: Assessing Anxiety, Memory and Sleep Alterations

The use of model organisms has been crucial for advancing both biological and medical sciences. These species are extensively studied to understand specific biological processes, with the expectation that insights gained from the model can be applied to other organisms, including humans [

39].

Zebrafish have proven especially valuable in investigating rare neurological disorders, highlighting their unique advantages compared to other vertebrate models [

15]. Over the past decade, the zebrafish has also emerged as a popular tool for investigating the neurotoxicity of drugs and environmental chemicals. There are many advantages to using zebrafish as an in vivo model, including external fertilization and the transparency of embryos and early larvae, which allow for direct microscopic observation during early developmental stages. External embryonic development also facilitates precise determination of chemical doses at all stages. Furthermore, the rapid growth and high fecundity of zebrafish enable high-throughput toxicity testing of multiple chemicals [

40,

41].

Caffeine exerts neuroactive effects primarily through antagonism of adenosine receptors, which regulate neuronal excitability, sleep, and mood. In zebrafish, as in mammals, caffeine can induce anxiogenic behavior, disrupt sleep homeostasis, and alter circadian rhythms. These disruptions affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal (HPI) axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels, which, depending on duration and intensity, can have adaptive or maladaptive consequences. Short-term caffeine exposure in zebrafish has been shown to increase anxiety, reduce exploratory behavior, elevate aggression, and impair HPI axis regulation. Long-term exposure further affects neurobehavioral functions, including swimming activity, social behavior, and memory, with high doses causing cognitive deficits that may persist or emerge during withdrawal [

9,

17,

42,

43].

3.1. Anxiety

Anxiety is a neuropsychiatric disorder that significantly impacts quality of life and remains a challenging medical issue. Studies indicate that caffeine can induce anxiety-related behaviors, with high caffeine exposure linked to increased anxiety levels in zebrafish [

44].

Zebrafish exhibit robust anxiety-like behaviors in response to environmental stressors and display complex social interactions, making them ideal for studying neuropsychiatric disorders and pharmacological interventions [

45]. Naturally, they exhibit anxiety when introduced to a novel environment. The Novel Tank Test (NTT) is commonly used to assess this behavior by measuring the fish’s innate diving response. This test has good face validity and construct validity, as anxiolytic drugs reduce the diving response while anxiogenic compounds exacerbate it [

46].

Caffeine has been shown to induce anxiety-like behaviors in zebrafish across developmental stages and experimental contexts. In larvae, exposure to concentrations ranging from 100 to 1000 µg/L provoked bradycardia, increased mortality, and heightened anxiety-like responses [

47]. In a study using the Larval Diving Response test, 7-day-old zebrafish larvae exposed to caffeine (100 mg/L for 30 minutes) showed increased anxiety-like behavior, spending less time at the bottom of the tank. This study demonstrates that caffeine acts as an anxiogenic agent in zebrafish larvae [

48]. In adults, short-term exposure to environmental concentrations of caffeine (0.5-200 µg/L) reduced exploratory behavior and enhanced stress responses in the NTT, confirming that acute exposure is sufficient to induce anxiogenic effects [

5]. Sex-specific differences have also been reported, with male and female zebrafish showing distinct anxiety responses and physiological reactions under caffeine exposure [

49,

50]. High caffeine intake (100 mg/kg) has also been associated with oxidative stress-mediated anxiety, which can be mitigated by antioxidants such as alpha-tocopherol [

51]. Environmental and social contexts further modulate these effects, with altered anxiety-like behaviors observed depending on social stimuli. In a study on adult zebrafish, exposure to caffeine at 25 mg/L (low dose) and 60 mg/L (moderate dose) for 10 minutes modulated anxiety-like behavior depending on social context. Anxiety-like effects were observed as increased bottom-dwelling and freezing behavior, assessed using the NTT. Social behavior was evaluated with a Social Preference Test, showing reduced time spent near conspecifics at the higher dose. This study demonstrates that both anxiety and social responses to caffeine are influenced by dose and social stimuli [

19]. In another study on adult zebrafish, caffeine exposure for 10 minutes induced anxiety-like behavior, with increased bottom-dwelling and freezing observed in the NTT. Social behavior was also affected, as fish spent less time near conspecifics in the Social Preference Test, showing reduced social interaction [

45] (

Table 1).

Together, these findings indicate that caffeine acts as an anxiogenic agent in zebrafish, with effects influenced by dose and developmental stage.

3.2. Memory

Zebrafish exhibit strong neuroanatomical and neurotransmitter similarities with humans, including homologues of the hippocampus, amygdala, and isocortex, as well as conserved glutamatergic, GABAergic, and cholinergic signaling. These features support complex neurobehaviors such as learning, memory retention, spatial and object recognition, and fear responses. As a result, zebrafish serve as a valuable vertebrate model for studying memory and cognitive function, including research on cognitive decline and drug discovery [

52].

Caffeine has been shown to affect memory function in zebrafish, particularly under stress or at varying doses. Juvenile zebrafish exposed to caffeine under unpredictable chronic stress conditions exhibited impairments in working memory, suggesting that caffeine can exacerbate stress-induced cognitive deficits [

53]. Memory performance in these studies was assessed using tasks such as the T-maze and novel object recognition, which evaluate spatial learning and short-term memory. Conversely, low doses of caffeine were found to enhance attention and focus in adult zebrafish, leading to improved performance in memory-related tasks, indicating a dose-dependent effect of caffeine on cognitive function [

54]. These findings highlight that caffeine can exert both beneficial and detrimental effects on memory in zebrafish, depending on the developmental stage, stress exposure, and administered dose.

Memory formation is strongly influenced by sleep, during which neural connections in the brain are strengthened. This reinforcement enhances the ability to retain and consolidate memories into long-term storage. Sleep deprivation or insomnia weakens these neural connections, leading to reduced memory retention. In general, insufficient sleep is associated not only with impaired memory but also with other negative outcomes, including increased risk of maladaptive behaviors [

55].

3.3. Sleep

Sleep is a fundamental and conserved feature of animal life, primarily serving brain functions such as energy replenishment and memory consolidation. Its timing and intensity are regulated by circadian rhythms and homeostatic sleep pressure, which reflects prior neuronal activity. Studies in zebrafish have shown that increasing neuronal activity with arousing drugs like caffeine induces rebound sleep, independent of prior wake duration or physical activity, suggesting that sleep need is closely tied to overall brain activity [

56]. The noradrenergic system, particularly the locus coeruleus, plays a key role in maintaining wakefulness and modulating sleep pressure, with changes in its activity influencing both arousal and subsequent sleep [

57]. Animal models, including zebrafish, have greatly contributed to understanding sleep mechanisms. Unlike nocturnal rodents, zebrafish exhibit diurnal sleep patterns similar to humans [

58]. Their pineal gland is fully developed by 19-20 hours post-fertilization (hpf) and produces melatonin at night under circadian control [

59]. Zebrafish larvae can display complex sleep behaviors as early as 4 days post-fertilization, and their small size allows for detailed monitoring using videography in a 96-well plate format. One study investigated the effects of caffeine on sleep and behavior in zebrafish larvae. Exposure to caffeine at 31.25-120 μM for 48 hours disrupted normal sleep patterns, significantly reducing total sleep time and sleep efficiency. These findings highlight the impact of caffeine on larval zebrafish sleep and behavior, with potential relevance to human sleep regulation [

18].

Caffeine has been shown to counteract cognitive deficits caused by sleep deprivation in adult zebrafish. This effect is mediated through activation of protein kinase A, which regulates O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine cycling, highlighting a molecular mechanism by which caffeine can mitigate sleep-related memory impairments [

60].

4. Developmental Alterations Induced by Caffeine in Zebrafish

Studying developmental alterations in zebrafish is crucial because their rapid embryonic development, genetic similarity to humans, and transparent embryos allow for precise observation of morphological, cardiovascular, and neurobehavioral effects, making them an ideal model to investigate the potential toxicity and teratogenicity of compounds [

41,

61].

Previous studies have shown that caffeine can induce teratogenic and long-term neurodevelopmental effects in zebrafish embryos via oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis. In this study conducted by Felix et al., embryos (~2 hpf) were exposed to 0.5 mM caffeine, either alone or in combination with 24-epibrassinolide (24-EPI) at 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μM, for 96 hours. Caffeine exposure alone caused a significant increase in developmental malformations, including edema and tail curvature, as well as locomotor deficits such as decreased speed and distance traveled, along with disrupted anxiety-like and avoidance behaviors [

62]. Another study revealed that exposure of zebrafish embryos to caffeine caused dose-dependent developmental alterations. At 0.05 mg/mL (50 mg/L), embryos developed normally with high survival rates and no noticeable deformities. Increasing the concentration to 0.25 mg/mL (250 mg/L) resulted in visible developmental defects, including edema in the heart and yolk sac, bent tails, and curved spinal columns, although most embryos survived. At the highest concentration tested, 1 mg/mL (1000 mg/L), survival dropped drastically, and embryos exhibited severe malformations such as pronounced edema, tail bending, and spinal curvature. These findings indicate that caffeine can significantly disrupt normal embryonic development in zebrafish at moderate to high concentrations, affecting both morphology and viability [

63]. High doses of caffeine have been shown to cause significant developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Exposure starting at 2–24 hpf to concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 500 μM resulted in dose-dependent developmental defects, including low morphological scores affecting the notochord and heart, general malformations, reduced normal phenotypes, disrupted sleep rhythms, and altered locomotor activity. Wei at al., found that moderate concentrations such as 31.25 μM, 62.5 μM, and 125 μM exhibited a favorable safety profile with high survival rates, whereas higher concentrations (250–500 μM) caused pronounced teratogenic effects. These findings suggest that caffeine exposure during early-life stages can severely impact structural and functional development in zebrafish, highlighting the importance of carefully considering dose and exposure time in neurodevelopmental and behavioral studies [

18]. Moreover, exposure of zebrafish embryos to caffeine at concentrations of 250–350 ppm caused significant developmental alterations, primarily affecting vascular formation, as suggested by Yeh et al., in their investigation. The embryos displayed abnormal development of intersegmental vessels, dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels, and subintestinal vein sprouting, indicating impaired angiogenesis [

20]. Some findings suggested that exposure of zebrafish embryos to caffeine at concentrations ranging from 17.5 to 150 mg/L caused significant neuromuscular and developmental alterations. At the highest concentration (150 mg/L), embryos exhibited reduced body length (2.67 ± 0.03 mm compared to 3.26 ± 0.01 mm in controls) and a marked decrease in touch-induced movement, dropping from 9.93 ± 0.77 in controls to 0.10 ± 0.06. Immunostaining revealed misalignment of muscle fibers and defects in primary and secondary motor axon projections, indicating impaired neuromuscular development, in the study by Chen et al. These results demonstrate that caffeine at moderate to high doses disrupts normal motor function and neuromuscular formation in zebrafish embryos, highlighting its potential impact on early motor behavior and structural development [

64]. Moreover, exposure to caffeine has been shown to affect early developmental processes in zebrafish larvae. In the study by Chakraborty et al., 2011, caffeine treatment significantly increased heart rate, reaching 125–140 beats per minute, while simultaneously reducing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, a key regulator of angiogenesis. These findings suggest that high caffeine doses can disrupt normal vascular development and potentially lead to developmental defects in zebrafish embryos, highlighting the sensitivity of early developmental stages to chemical exposure [

65] (

Table 2).

5. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Responses

Oxidative stress arises when the production of reactive species exceeds the capacity of cellular defenses to neutralize them. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, can generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals in the presence of transition metals. Additionally, interactions between superoxide and nitric oxide produce reactive nitrogen species like peroxynitrite, which can also form •OH radicals [

33].

Caffeine can influence oxidative stress in the brain by modulating ROS and neurotransmitter systems such as glutamate. While oxidative stress is known to contribute to neurobehavioral alterations, its role as a mechanism underlying caffeine-induced behavioral changes remains to be fully elucidated [

66].

Coffee is considered one of the main dietary sources of antioxidant compounds, which can neutralize ROS, the primary contributors to oxidative stress [

67]. While caffeine is often regarded for its antioxidant properties, some studies suggest that it can also act as a prooxidant under certain conditions In particular, the study by Gülçin, 2008 demonstrated that caffeine promoted linoleic acid peroxidation in emulsions at concentrations of 15, 30, and 45 µg/mL, resulting in oxidation levels of 32.5%, 48.9%, and 54.3%, respectively. These findings support the idea that, depending on the environment and concentration, caffeine may contribute to oxidative processes rather than exclusively neutralizing free radicals. Such dual behavior highlights the complexity of caffeine’s biological effects and suggests that its role in oxidative stress may be context-dependent [

68].

Research on coffee consumption and antioxidant effects has yielded mixed findings. Some studies have shown that coffee intake can significantly increase plasma antioxidant capacity [

69,

70,

71,

72]. For example, a single serving of 200-400 mL of coffee raised plasma antioxidant markers by 2-7% [

71,

73], although long-term interventions often showed inconsistent effects [

69,

72]. Chronic trials also examined endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, GPx, GSR, and GSTs, with some studies documenting increases up to 75% for SOD and around 60% for GPx [

72]. In contrast, other studies found reduced enzyme activity [

74], and results on glutathione (GSH) were also variable, with several studies reporting increases [

75,

76], while others found no effect [

77,

78]. Overall, coffee can enhance antioxidant defenses, but the extent of the effect depends on the type of coffee, dose, and study design.

In one study by Abdelkader et al., 2013 it was observed that prolonged exposure to caffeine induced oxidative stress in zebrafish embryos. This was evidenced by increased gene expression related to cell damage and apoptosis, as well as mitochondrial dysfunction. These findings suggest that caffeine exposure during early development stages can compromise cellular integrity and function in zebrafish embryos [

79]. Moreover, another study conducted on zebrafish, the subjects were exposed for 28 days to caffeine concentrations ranging from 0.16 to 50 μg/L. The results showed increased activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione reductase (GRed) and a reduction in glutathione levels, while lipid peroxidation remained unchanged. Metabolic alterations were observed, with decreased LDH activity and higher lipid content, and at the highest doses (19.23 and 50 μg/L) a reduction in acetylcholinesterase activity suggested possible neurotoxic effects. Overall, the findings highlight that even low, environmentally relevant concentrations of caffeine can interfere with oxidative balance, metabolism, and neural function in fish [

80]. Another study conducted on zebrafish demonstrated that high doses of caffeine induce oxidative stress in the brain, evidenced by a significant increase in lipid peroxidation, measured as elevated MDA levels. Interestingly, treatment with the antioxidant alpha-tocopherol prevented this biochemical alteration and also reduced anxiety-like behaviors induced by caffeine, suggesting that oxidative stress plays a key role in mediating the neurobehavioral effects of caffeine in zebrafish [

51] (

Table 3).

6. Conclusions

Evidence from zebrafish studies highlights that caffeine exerts complex, dose-dependent neurobehavioral effects, particularly on anxiety, memory, and sleep. At low doses, caffeine may enhance attention and memory-related performance, but higher concentrations consistently induce anxiety-like behaviors, reduce exploratory activity, and disrupt normal social interactions. Sleep regulation is also profoundly affected, with larval zebrafish exposed to caffeine showing reduced total sleep time and efficiency, while in adults, caffeine can temporarily mitigate memory impairments caused by sleep deprivation through molecular pathways such as protein kinase A activation. These findings underscore caffeine’s dual role as both a cognitive enhancer and a neurobehavioral disruptor, depending on developmental stage, dose, and exposure context.

Beyond behavioral outcomes, caffeine exposure during early zebrafish development produces clear morphological and structural alterations. Embryos and larvae exposed to moderate and high doses exhibit dose-dependent malformations including cardiac and yolk sac edema, spinal curvature, impaired angiogenesis, and neuromuscular defects. These alterations not only compromise survival but also translate into long-term functional deficits, such as reduced locomotor activity and impaired anxiety or avoidance behaviors. Such teratogenic outcomes emphasize the heightened vulnerability of embryonic and larval stages to caffeine and position zebrafish as a sensitive model for developmental neurotoxicology.

Mechanistically, many of these effects are mediated through oxidative stress pathways. Caffeine can act as both an antioxidant and a prooxidant, with studies in zebrafish showing upregulation of oxidative stress-related genes, mitochondrial dysfunction, lipid peroxidation, and reductions in glutathione levels. At the same time, compensatory activation of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and GRed suggests an adaptive response to redox imbalance. Importantly, antioxidant supplementation, such as alpha-tocopherol, has been shown to mitigate both oxidative stress and caffeine-induced anxiety behaviors, linking redox regulation to neurobehavioral outcomes.

Overall, zebrafish studies indicate that caffeine’s influence on anxiety, memory, sleep, and development is tightly interconnected with its oxidative stress-modulating properties, highlighting the importance of dose, exposure time, and developmental stage in determining its beneficial versus detrimental effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I. and P.-F.L.; methodology, C.I. and V.R.; validation, V.R. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.I. and P.-F.L.; writing—review and editing, V.R., M.V. and G.-I.P.; supervision, G.-I.P. and A.C.; project administration, C.I. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saraiva, S.M.; Jacinto, T.A.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Gaspar, D.; Silva, L.R. Overview of Caffeine Effects on Human Health and Emerging Delivery Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.S.; Shiva, S.; Manikantan, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Pharmacology of Caffeine and Its Effects on the Human Body. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čižmárová, B.; Kraus, V.; Birková, A. Caffeinated Beverages—Unveiling Their Impact on Human Health. Beverages 2025, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.R.; Giles, G.E.; Marriott, B.P.; Judelson, D.A.; Glickman, E.L.; Geiselman, P.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Intake of Caffeine from All Sources and Reasons for Use by College Students. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.; Picolo, V.; Domingues, I.; Perillo, V.; Villacis, R.A.R.; Grisolia, C.K.; Oliveira, M. Effects of Environmental Concentrations of Caffeine on Adult Zebrafish Behaviour: A Short-Term Exposure Scenario. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaiescu, T.; Turti, S.; Souca, M.; Muresan, R.; Achim, L.; Prifti, E.; Papuc, I.; Munteanu, C.; Marza, S.M. Caffeine and Taurine from Energy Drinks—A Review. Cosmetics 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Agriantonis, G.; Dawson-Moroz, S.; Brown, R.; Simon, W.; Ebelle, D.; Chapelet, J.; Cardona, A.; Soni, A.; Siddiqui, M.; et al. Caffeine: A Neuroprotectant and Neurotoxin in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Nutrients 2025, 17, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.Q.; Sharma, L.; Essiet, E.; Elhassan, O.; Fahim, R.; Irem-Oko, F.; Sreedharan, J. Caffeine Consumption Patterns, Health Impacts, and Media Influence: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahdouzan, M.; Hamadeh, M.J. The Neuroprotective Effects of Caffeine in Neurodegenerative Diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, F. Caffeine Induces Neurobehavioral Effects through Modulating Neurotransmitters. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, R.P.; Lima, F.D.; Carvalho, N.R.; Bresciani, G.; Royes, L.F. Caffeine Effects on Systemic Metabolism, Oxidative-Inflammatory Pathways, and Exercise Performance. Nutrition Research 2020, 80, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, R.L.; Christian, M.S.; Diener, R.M. Evaluation of the Reproductive and Developmental Risks of Caffeine. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 2011, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teame, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ran, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Xie, M.; Gao, C.; Ye, Y.; Duan, M.; et al. The Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) as Biomedical Models. Animal Frontiers 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.-Y.; Choi, T.-I.; Lee, Y.-R.; Choe, S.-K.; Kim, C.-H. Zebrafish as an Animal Model for Biomedical Research. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Don, D.W.; Choi, T.-I.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lee, K.-H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C.-H. Using Zebrafish as an Animal Model for Studying Rare Neurological Disorders: A Human Genetics Perspective. Journal of Genetic Medicine 2024, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.; Lobato-Freitas, C.; Monteiro, S.M.; Venâncio, C. 24-Epibrassinolide Modulates the Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of High Caffeine Exposure in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology 2021, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.V.; Ardais, A.P.; Costa, F.V.; Fontana, B.D.; Quadros, V.A.; Porciúncula, L.O.; Rosemberg, D.B. Different Effects of Caffeine on Behavioral Neurophenotypes of Two Zebrafish Populations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2018, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Miao, Z.; Ye, H.; Wu, M.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, L. The Effect of Caffeine Exposure on Sleep Patterns in Zebrafish Larvae and Its Underlying Mechanism. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.C.; Lyttle, M.; Kanan, A.; Le, A. Social Stimuli Impact Behavioral Responses to Caffeine in the Zebrafish. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Liao, Y.-F.; Chang, C.-Y.; Tsai, J.-N.; Wang, Y.-H.; Cheng, C.-C.; Wen, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-H. Caffeine Treatment Disturbs the Angiogenesis of Zebrafish Embryos. Drug Chem Toxicol 2012, 35, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, R.M.; Zizioli, D.; Muscò, A.; Finazzi, D.; Sigala, S.; Rossini, E.; Tobia, C.; Guerra, J.; Presta, M.; Memo, M. Caffeine Inhibits Direct and Indirect Angiogenesis in Zebrafish Embryos. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, C.L.; Connaughton, V.P. Neurochemical and Behavioral Consequences of Ethanol and/or Caffeine Exposure: Effects in Zebrafish and Rodents. Curr Neuropharmacol 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, N.O.; de Sousa Andrade, T.; Santos, V.L.; Galvino, P.; Suares-Rocha, P.; Domingues, I.; Grisolia, C.K.; Oliveira, R. Neuromotor Activity Inhibition in Zebrafish Early-Life Stages after Exposure to Environmental Relevant Concentrations of Caffeine. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2021, 56, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B. Notes on the History of Caffeine Use. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2011, 200. [Google Scholar]

- dePaula, J.; Farah, A. Caffeine Consumption through Coffee: Content in the Beverage, Metabolism, Health Benefits and Risks. Beverages 2019, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Singh, M.; Lee, K.E.; Vinayagam, R.; Kang, S.G. Caffeine: A Multifunctional Efficacious Molecule with Diverse Health Implications and Emerging Delivery Systems. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembiałkowska, N.; Demiy, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Mastalerz, J.; Szlasa, W. Caffeine as a Modulator in Oncology: Mechanisms of Action and Potential for Adjuvant Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Marques-Jiménez, D.; Refoyo, I.; Del Coso, J.; León-Guereño, P.; Calleja-González, J. Effect of Caffeine Supplementation on Sports Performance Based on Differences between Sexes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soós, R.; Gyebrovszki, Á.; Tóth, Á.; Jeges, S.; Wilhelm, M. Effects of Caffeine and Caffeinated Beverages in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults: Short Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, C. The Clinical Toxicology of Caffeine: A Review and Case Study. Toxicol Rep 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsunni, A.A. Energy Drink Consumption: Beneficial and Adverse Health Effects. International Journal of Health Science 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Singh, M.; Lee, K.E.; Vinayagam, R.; Kang, S.G. Caffeine: A Multifunctional Efficacious Molecule with Diverse Health Implications and Emerging Delivery Systems. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ősz, B.E.; Jîtcă, G.; Ștefănescu, R.E.; Pușcaș, A.; Tero-Vescan, A.; Vari, C.E. Caffeine and Its Antioxidant Properties—It Is All about Dose and Source. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-K.; Ahn, H.-S.; Kim, D.-E.; Lee, D.-S.; Park, C.-S.; Kang, C.-K. Effects of Varying Caffeine Dosages and Consumption Timings on Cerebral Vascular and Cognitive Functions: A Diagnostic Ultrasound Study. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, D.; Montes, F.R.; Cabrera, M.; Galán, A.; Prieto, A. Caffeine’s Vascular Mechanisms of Action. Int J Vasc Med 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Garcia, E.; Van Dam, R.M.; Li, T.Y.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Hu, F.B. The Relationship of Coffee Consumption with Mortality. Ann Intern Med 2008, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolignano, D.; Coppolino, G.; Barillà, A.; Campo, S.; Criseo, M.; Tripodo, D.; Buemi, M. Caffeine and the Kidney: What Evidence Right Now? Journal of Renal Nutrition 2007, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodak, K.; Kokot, I.; Kratz, E.M. Caffeine as a Factor Influencing the Functioning of the Human Body—Friend or Foe? Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blechman, J.; Levkowitz, G.; Gothilf, Y. The Not-so-Long History of Zebrafish Research in Israel. International Journal of Developmental Biology 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Freeman, J.L. Zebrafish as a Model for Developmental Neurotoxicity Assessment: The Application of the Zebrafish in Defining the Effects of Arsenic, Methylmercury, or Lead on Early Neurodevelopment. Toxics 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugel, S.M.; Tanguay, R.L.; Planchart, A. Zebrafish: A Marvel of High-Throughput Biology for 21st Century Toxicology. Curr Environ Health Rep 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.; Picolo, V.; Domingues, I.; Sousa-Moura, D.; Grisolia, C.K.; Oliveira, M. Behavioral and Biochemical Effects of Environmental Concentrations of Caffeine in Zebrafish after Long-Term Exposure. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2024, 59, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alia, A.O.; Petrunich-Rutherford, M.L. Anxiety-like Behavior and Whole-Body Cortisol Responses to Components of Energy Drinks in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). PeerJ 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; Lu, Z.; Li, K. Zebrafish Gender-Specific Anxiety-like Behavioral and Physiological Reactions Elicited by Caffeine. Behavioural Brain Research 2024, 472, 115151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.S.; Olary, L.; Sivarajan, D.; Amar, A.; Ramachandran, B. Caffeine Bidirectionally Regulates Social Preference and Anxiety-like Behavior in Zebrafish. Brazilian Journal of Development 2025, 11, e81087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, B.D.; Parker, M.O. The Larval Diving Response (LDR): Validation of an Automated, High-Throughput, Ecologically Relevant Measure of Anxiety-Related Behavior in Larval Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). J Neurosci Methods 2022, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Hasumi, A.; Yoshida, K. ichi Caffeine-Induced Bradycardia, Death, and Anxiety-like Behavior in Zebrafish Larvae. Forensic Toxicol 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, B.D.; Parker, M.O. The Larval Diving Response (LDR): Validation of an Automated, High-Throughput, Ecologically Relevant Measure of Anxiety-Related Behavior in Larval Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). J Neurosci Methods 2022, 381, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, A.; Ramachandran, B. Environmental Stressors Differentially Modulate Anxiety-like Behaviour in Male and Female Zebrafish. Behavioural Brain Research 2023, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; Lu, Z.; Li, K. Zebrafish Gender-Specific Anxiety-like Behavioral and Physiological Reactions Elicited by Caffeine. Behavioural Brain Research 2024, 472, 115151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, T.S.; Cardoso, P.B.; Santos-Silva, M.; Lima-Bastos, S.; Luz, W.L.; Assad, N.; Kauffmann, N.; Passos, A.; Brasil, A.; Bahia, C.P.; et al. Oxidative Stress Mediates Anxiety-Like Behavior Induced by High Caffeine Intake in Zebrafish: Protective Effect of Alpha-Tocopherol. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.K.; Nazar, F.H.; Makpol, S.; Teoh, S.L. Zebrafish: A Pharmacological Model for Learning and Memory Research. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazkia, A.A.; Nugraha, Z.S. The Effect of Caffeine towards Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Juvenile Working Memory Exposed by Unpredictable Chronic Stress (UCS).; 2021.

- Ruiz-Oliveira, J.; Silva, P.F.; Luchiari, A.C. Coffee Time: Low Caffeine Dose Promotes Attention and Focus in Zebrafish. Learn Behav 2019, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almosawi, S.; Baksh, H.; Qareeballa, A.; Falamarzi, F.; Alsaleh, B.; Alrabaani, M.; Alkalbani, A.; Mahdi, S.; Kamal, A. Acute Administration of Caffeine: The Effect on Motor Coordination, Higher Brain Cognitive Functions, and the Social Behavior of BLC57 Mice. Behavioral Sciences 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, E.; Lyons, D.G.; Rihel, J. Noradrenergic Tone Is Not Required for Neuronal Activity-Induced Rebound Sleep in Zebrafish. J Comp Physiol B 2024, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Van Bockstaele, E.J. The Locus Coeruleus- Norepinephrine System in Stress and Arousal: Unraveling Historical, Current, and Future Perspectives. Front Psychiatry 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanova, I. V. Sleep and Its Regulation in Zebrafish. Rev Neurosci 2011, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimi, N.; Cahill, G.M. Development of a Circadian Melatonin Rhythm in Embryonic Zebrafish. Developmental Brain Research 1999, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.D.T.; Park, J.; Kim, D.Y.; Han, I.O. Caffeine-Induced Protein Kinase A Activation Restores Cognitive Deficits Induced by Sleep Deprivation by Regulating O-GlcNAc Cycling in Adult Zebrafish. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2024, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoriello, C.; Zon, L.I. Hooked! Modeling Human Disease in Zebrafish. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2012, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.; Lobato-Freitas, C.; Monteiro, S.M.; Venâncio, C. 24-Epibrassinolide Modulates the Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of High Caffeine Exposure in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2021, 249, 109143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, C. The Effect of Caffeine on Zebrafish Embryo Development.

- Chen, Y.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Wen, C.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, W.L.; Chen, L.C.; Tsay, H.J. Movement Disorder and Neuromuscular Change in Zebrafish Embryos after Exposure to Caffeine. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2008, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, C.; Hsu, C.H.; Wen, Z.H.; Lin, C.S.; Agoramoorthy, G. Effect of Caffeine, Norfloxacin and Nimesulide on Heartbeat and VEGF Expression of Zebrafish Larvae. J Environ Biol 2011, 32. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, T.S.; Cardoso, P.B.; Santos-Silva, M.; Lima-Bastos, S.; Luz, W.L.; Assad, N.; Kauffmann, N.; Passos, A.; Brasil, A.; Bahia, C.P.; et al. Oxidative Stress Mediates Anxiety-Like Behavior Induced by High Caffeine Intake in Zebrafish: Protective Effect of Alpha-Tocopherol. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Tassotti, M.; Riso, P.; Rio, D. Del; Brighenti, F.; Porrini, M. Coffee Consumption and Oxidative Stress: A Review of Human Intervention Studies. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçİn, İ. In Vitro Prooxidant Effect of Caffeine. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2008, 23, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Ochoa, G.M.; Pulgarín-Zapata, I.C.; Velásquez-Rodriguez, C.M.; Duque-Ramírez, M.; Naranjo-Cano, M.; Quintero-Ortiz, M.M.; Lara-Guzmán, O.J.; Muñoz-Durango, K. Coffee Consumption Increases the Antioxidant Capacity of Plasma and Has No Effect on the Lipid Profile or Vascular Function in Healthy Adults in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Nutrition 2016, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura-Nunes, N.; Perrone, D.; Farah, A.; Donangelo, C.M. The Increase in Human Plasma Antioxidant Capacity after Acute Coffee Intake Is Not Associated with Endogenous Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Components. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009, 60, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natella, F.; Nardini, M.; Giannetti, I.; Dattilo, C.; Scaccini, C. Coffee Drinking Influences Plasma Antioxidant Capacity in Humans. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.A.F.; Monteiro, M.P.; Mendes, T.M.N.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Rogero, M.M.; Benites, C.I.; Vinagre, C.G.C. de M.; Mioto, B.M.; Tarasoutchi, D.; Tuda, V.L.; et al. Medium Light and Medium Roast Paper-Filtered Coffee Increased Antioxidant Capacity in Healthy Volunteers: Results of a Randomized Trial. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2012, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura-Nunes, N.; Perrone, D.; Farah, A.; Donangelo, C.M. The Increase in Human Plasma Antioxidant Capacity after Acute Coffee Intake Is Not Associated with Endogenous Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Components. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009, 60, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyczka, C.; Boettler, U.; Lang, R.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; Hofmann, T.; Marko, D.; Somoza, V. Dark Roast Coffee Is More Effective than Light Roast Coffee in Reducing Body Weight, and in Restoring Red Blood Cell Vitamin E and Glutathione Concentrations in Healthy Volunteers. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakuradze, T.; Boehm, N.; Janzowski, C.; Lang, R.; Hofmann, T.; Stockis, J.P.; Albert, F.W.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; et al. Antioxidant-Rich Coffee Reduces DNA Damage, Elevates Glutathione Status and Contributes to Weight Control: Results from an Intervention Study. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, F.; Morisco, F.; Verde, V.; Ritieni, A.; Alezio, A.; Caporaso, N.; Fogliano, V. Moderate Coffee Consumption Increases Plasma Glutathione but Not Homocysteine in Healthy Subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelzl, C.; Knasmüller, S.; Wagner, K.H.; Elbling, L.; Huber, W.; Kager, N.; Ferk, F.; Ehrlich, V.; Nersesyan, A.; Neubauer, O.; et al. Instant Coffee with High Chlorogenic Acid Levels Protects Humans against Oxidative Damage of Macromolecules. Mol Nutr Food Res 2010, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišík, M.; Hoelzl, C.; Wagner, K.-H.; Cavin, C.; Moser, B.; Kundi, M.; Simic, T.; Elbling, L.; Kager, N.; Ferk, F.; et al. Impact of Paper Filtered Coffee on Oxidative DNA-Damage: Results of a Clinical Trial. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2010, 692, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, T.S.; Chang, S.N.; Kim, T.H.; Song, J.; Kim, D.S.; Park, J.H. Exposure Time to Caffeine Affects Heartbeat and Cell Damage-Related Gene Expression of Zebrafish Danio Rerio Embryos at Early Developmental Stages. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2013, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, B.S.; Antunes, S.C.; Pinto, I.; Amorim, J.; Teixeira, C.; Teles, L.O.; Golovko, O.; Žlábek, V.; Carvalho, A.P.; Rodrigues, S. Insights into Environmental Caffeine Contamination in Ecotoxicological Biomarkers and Potential Health Effects of Danio Rerio. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).