1. Introduction

The increasing prevalence of urban risks, encompassing a wide spectrum of hazards ranging from natural disasters to transport accidents, underscores the paramount importance of emergency management in contemporary urban contexts [

1]. In developed countries, the advent of digital technologies and connected infrastructure has precipitated the emergence of smart emergency management systems, which are now being integrated into smart city ecosystems [

2]. These systems are heavily reliant on the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing and advanced computational algorithms to ensure the rapid collection, processing and use of critical data in real time. However, the transposition of these models to sub-Saharan African contexts is impeded by significant structural and operational constraints, including fragmented infrastructure, intermittent connectivity, limited financial resources and insufficient institutional coordination [

3,

4].

In this particular context, the reduction of response times during emergency interventions is a matter of paramount importance [

5]. It is imperative that a suitable digital architecture combines computational efficiency, resilience to resource-constrained environments, and interoperability with heterogeneous systems. The aforementioned requirements necessitate the utilization of cutting-edge technologies such as FPGAs (field-programmable gate arrays), which possess the capacity to deliver high-performance hardware parallelism while maintaining optimal energy efficiency as evidenced by studies like [

6,

7], and distributed shortest path algorithms (Dijkstra, A*), optimized for dynamic urban networks [

8,

9].

An architecture of this type was recently proposed by Assoul et al. [

10], combining IoT sensors, edge servers equipped with FPGAs, and distributed algorithms to optimize response times in urban contexts. Designed for cities in sub-Saharan Africa, this architecture aims to reduce latency, strengthen operational resilience and optimize the management of heterogeneous data flows. However, while the technological foundations of the solution are solid, its relevance and feasibility in the real-world conditions of these environments have not yet been empirically validated.

This article addresses this need by proposing an empirical evaluation of the architecture based on expert opinion. The study is based on a structured questionnaire administered to 78 Cameroonian specialists in software engineering, distributed systems, digital urban planning and emergency technologies. This survey, structured around multiple analytical dimensions, aims to examine the technical viability of the architecture, its adaptability to local constraints and the critical challenges that condition its adoption. The results show a consensus on the technical and operational relevance of the architecture, which is perceived as a lever for reducing response times and optimizing coordination. Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly in terms of interoperability, urban data structuring, financial sustainability and multi-stakeholder governance. These lessons provide insights for research and development, including: field prototyping, the integration of distributed artificial intelligence, the involvement of local communities and the study of the ethical and societal dimensions of the technology.

The rest of the article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a state of the art in existing solutions for distributed emergency management, and summarizes the architecture in [

10] and its fundamental mechanisms.

Section 3 details the evaluation methodology.

Section 4 discusses the obtained results.

Section 5 presents a brief critical analysis of the methodology and the results; it also presents perspective work. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. State of the Art

Emergency management in smart cities has become a priority area of research, driven by increasing urbanization, the complexity of infrastructure and the need to drastically reduce response times [

1,

2]. Research efforts are converging around three main areas: algorithmic optimization of routes and resources, hardware acceleration to improve real-time performance, and the use of distributed computing paradigms such as Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) and Fog Computing.

First, a significant amount of research has focused on the algorithmic optimization of path finding and resource planning. Classic algorithms such as Dijkstra and A* remain at the heart of many solutions, adapted to dynamic contexts such as disaster evacuation or emergency vehicle routing [

8,

9,

11]. Several hybrid approaches integrate complementary techniques to enrich decision-making. For example, Omomule et al. [

12] combine Dijkstra’s algorithm with fuzzy logic to choose not only the optimal route but also the most suitable hospital, taking into account the severity of the accident and the availability of medical resources. Similarly, Chen et al. [

13] apply Dijkstra to urban evacuation scenarios, while others explore heuristic variants more suited to large graphs [

14]. These solutions demonstrate the relevance of algorithmic approaches, but they encounter computational performance limitations when environments become complex and dynamic.

Secondly, hardware acceleration is an essential lever for overcoming the computational constraints associated with large graphs or real-time requirements. Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are widely used to parallelize calculations and reduce energy consumption, two crucial conditions for embedded systems and distributed infrastructures [

6,

7]. Fernandez et al. [

15] propose a parallel implementation of Dijkstra on FPGA, achieving significant acceleration compared to traditional software solutions. Other work, such as that of Zhou et al. [

9] or Esteves et al. [

16], rely on FPGAs to improve the speed of the A* algorithm in robot navigation or real-time planning contexts. This research path confirms the value of the hardware approach but also reveals constraints related to embedded memory and communication between host processors and FPGA modules, which limit scalability to very large graphs.

Thirdly, the use of distributed computing paradigms such as MEC and Fog Computing has attracted growing interest in the field of urban emergency management. These approaches bring computing closer to data sources, thereby reducing latency and improving system resilience [

17,

18]. They have proven effective for real-time monitoring of urban infrastructure [

19], priority routing of emergency vehicles [

20] and coordination of drones in surveillance operations [

21]. However, their implementation faces challenges in terms of interoperability, standardization and data security management, particularly in urban environments characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of actors and infrastructure [

22,

23].

In summary, the state of the art shows that significant advances have been made in algorithmic optimization, the exploitation of hardware parallelism and the integration of distributed computing paradigms. Nevertheless, most of the work remains limited to conceptual models, simulations or experimental prototypes. The issue of validation under real-world conditions therefore remains a key challenge, particularly in resource-constrained contexts such as cities in sub-Saharan Africa, where financial, infrastructural and organizational constraints require technological solutions to be adapted.

2.2. Architecture of Assoul et al. [10] and the Need for Empirical Validation

2.2.1. The Architecture

In a recent article, Assoul et al. [

10] proposed an innovative architecture aimed at improving emergency response management in the context of smart cities. This architecture is based on the coherent integration of advanced technologies: IoT sensors, edge computing, shortest path algorithms (notably Dijkstra) and FPGA-based hardware accelerators. The main objective is to significantly reduce response times in the event of an accident or disaster by harnessing the power of distributed processing as close as possible to the data source.

Three fundamental principles guide its design:

- 1.

Time efficiency: minimizing transmission and processing times to speed up decision-making and the deployment of emergency services.

- 2.

Optimal resource allocation: relying on distributed algorithms and decentralized computing capabilities to efficiently direct available resources (personnel, equipment, vehicles).

- 3.

Adaptability to constrained contexts: taking into account the realities of fragile infrastructure and limited resources by integrating mechanisms such as fault tolerance, low bandwidth requirements, or the ability to operate offline.

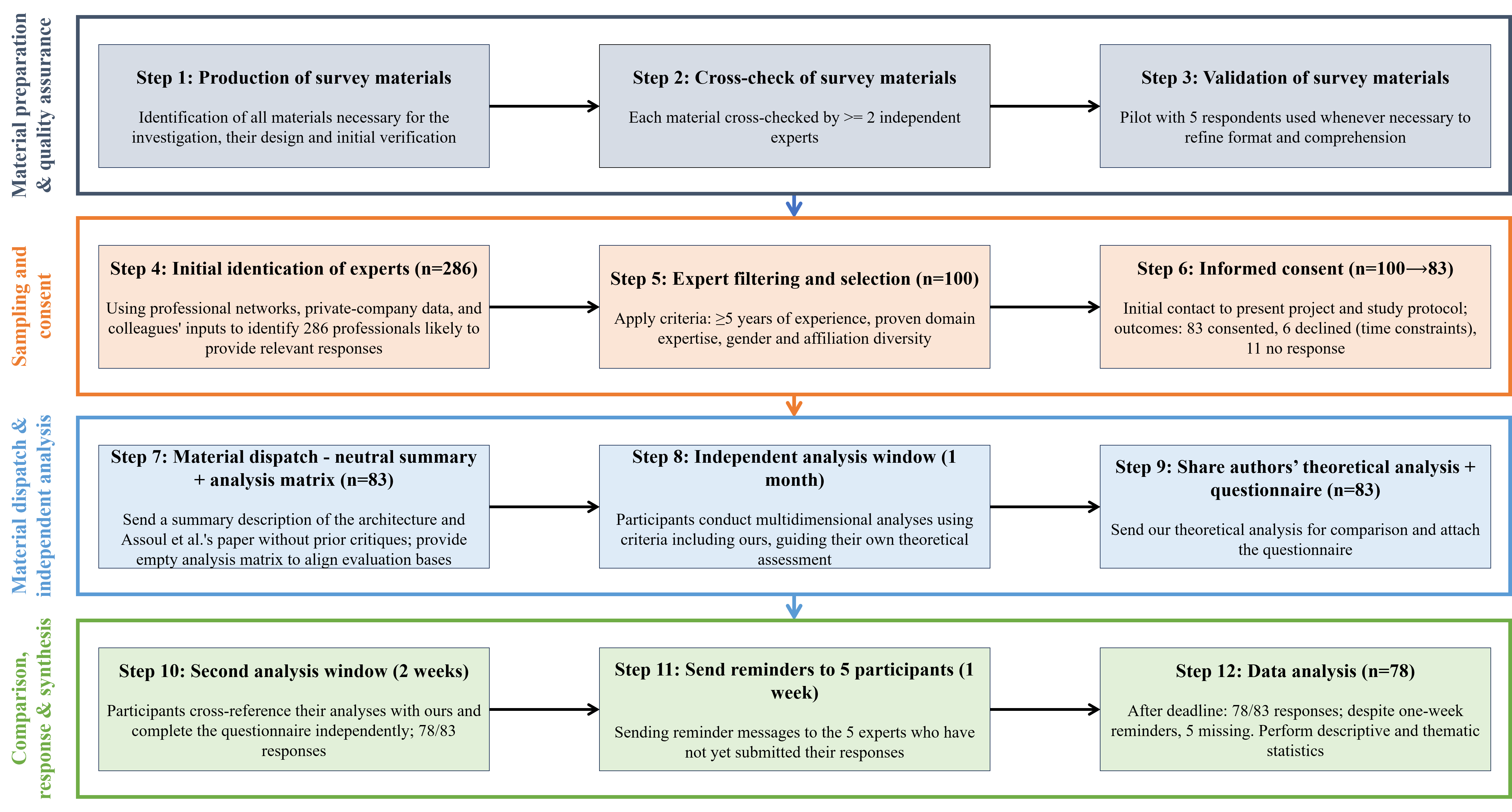

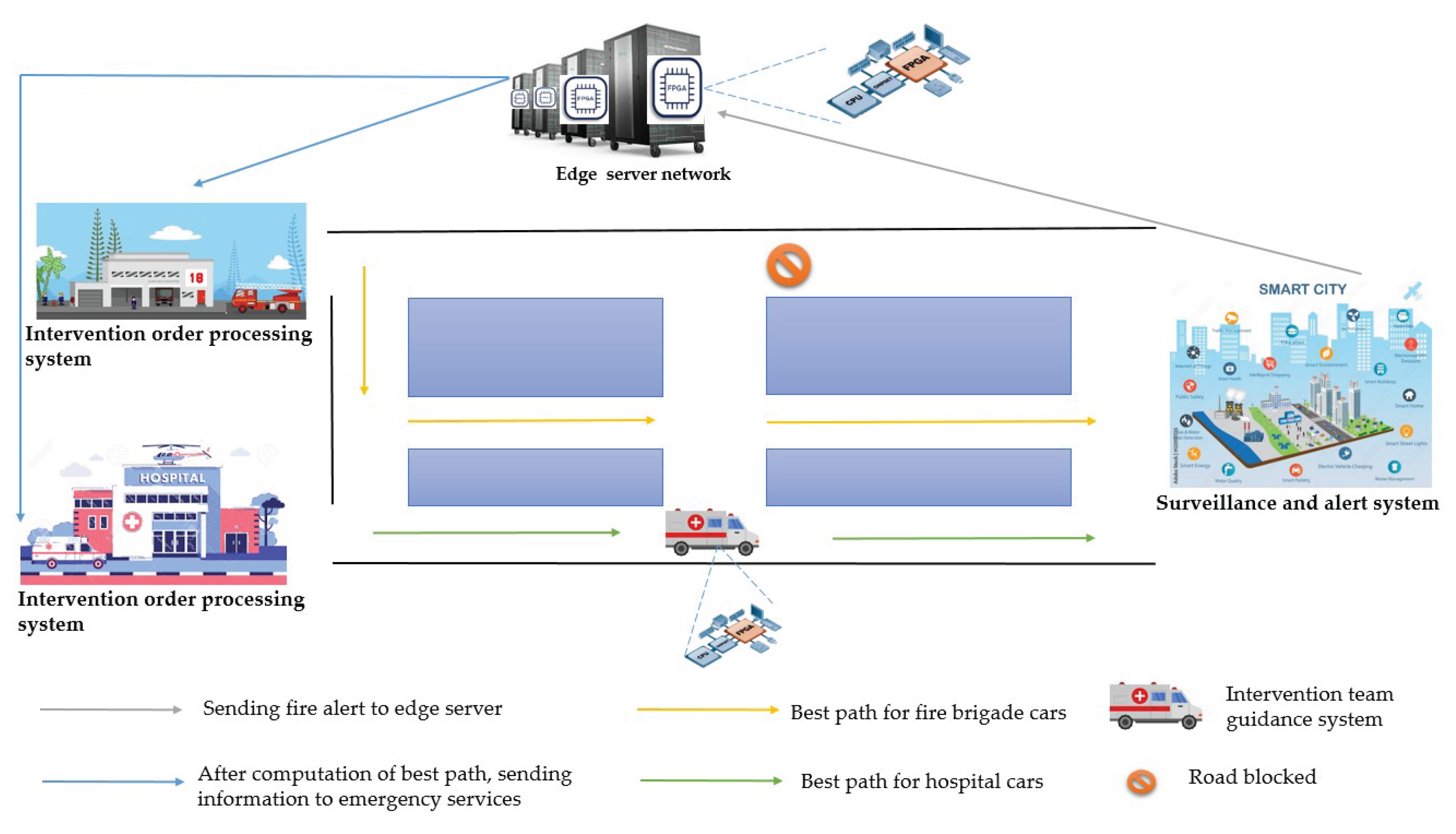

The architecture comprises several complementary subsystems (

Figure 1):

- 1.

The Surveillance and Alerting System (SAS): network of connected objects (IoT) deployed in buildings and strategic areas, equipped with sensors capable of detecting various incidents (fires, accidents, security threats, natural disasters) and automatically generating alerts.

- 2.

The Edge Server Network (ESN): a set of edge servers, each equipped with FPGA cards, responsible for receiving alerts and performing distributed calculations. These servers model the city as a graph and use a distributed version of Dijkstra’s algorithm to calculate the shortest paths to the incident scene in parallel, taking service priorities into account.

- 3.

The Intervention Order Processing System (IOPS): present in every emergency service (police, fire brigade, hospitals, etc.), this module receives alerts from edge servers, prioritizes interventions, prepares teams and coordinates communications with other entities.

- 4.

The Intervention Team Guidance System (ITGS): also based on FPGA, it supports teams in the field by providing optimized routes and dynamically recalculating paths in the event of unforeseen circumstances (traffic jams, road closures, service unavailability).

Figure 1.

Overview of the architecture of Assoul et al. [

10].

Figure 1.

Overview of the architecture of Assoul et al. [

10].

The proposed architecture can be analyzed using a multidimensional grid that combines three operational efficiency criteria (

time efficiency,

resource allocation,

ease of use) with three critical evaluation axes (

contributions,

limitations,

challenges). To this end,

Table 1 presents an analysis matrix summarizing the specific roles, strengths, limitations and challenges for each component of the architecture.

A horizontal reading of the table highlights certain points of convergence:

In terms of temporal efficiency, the system relies on a systemic reduction in latency (detection → calculation → coordination → execution), thanks to the synergy between edge processing and the distribution of decision-making intelligence.

For resource allocation, the optimization (ESN) and decision-making (IOPS) functions are distinct but complementary, allowing the architecture to remain flexible and modular.

In terms of ease of use, the architecture has been explicitly designed for environments with low connectivity and degraded infrastructure, but requires a particular effort in terms of maintenance, training and local supervision.

The robustness of the proposed architecture lies in its distributed cooperative model, which distributes critical responsibilities among the various subsystems. This functional decoupling allows for increased operational flexibility, but also requires rigorous interface design and fault management. The main advantage is the alignment between the distributed software structure and the practical constraints of African urban contexts. The main challenge, however, lies in the transition to real-world deployments: this requires not only technical validation, but also socio-institutional adaptation.

2.2.2. The Need for Validation

Despite its innovative nature, the architecture published by Assoul et al. [

10] has not yet been empirically validated. It is presented in a conceptual and theoretical manner, with a discussion of its potential advantages, but without practical evaluation (through simulation, prototyping or experimentation). However, in the field of distributed systems and critical urban infrastructure, validation is an essential step in assessing the feasibility, robustness and adaptability of a solution. An analysis of existing work highlights four main approaches to validating distributed architectures and embedded systems.

The first approach is based on computer simulation, which involves using software tools such as MATLAB, NS3, SUMO or Omnet++ to model the behavior of an architecture and evaluate its performance in simulated scenarios [

24]. This method has the advantage of being flexible, inexpensive and allowing the exploration of a large number of use cases. However, it remains essentially conceptual and depends largely on modeling assumptions, which may deviate from reality. For example, Chen et al. [

13] were able to simulate urban evacuation scenarios using Dijkstra’s algorithm without resorting to actual deployment.

The second approach is prototype manufacturing, which aims to deploy hardware and software, usually on a small scale, to test the technical feasibility of a solution [

25]. This method is more realistic than simulation because it highlights the practical constraints related to hardware, communications and energy consumption. Nevertheless, it remains costly in financial and material terms and is often limited to laboratory environments. A typical example is that of Fernandez et al. [

15], who designed an FPGA-based prototype to accelerate Dijkstra’s algorithm.

The third approach involves implementation and experimentation in real-world conditions, which consists of deploying the architecture in an operational environment, such as a pilot city or an equipped urban area. This method offers the most credible validation and the richest practical lessons, but it is also extremely costly and requires institutional cooperation and existing infrastructure. As a result, it is rarely feasible in an academic setting. However, there are some examples, particularly in work on the management of connected traffic lights, which are sometimes tested in real environments but in limited urban areas [

20].

Finally, a fourth approach is based on empirical evaluation based on expertise, which involves collecting and analyzing the opinions of experts in the field (engineers, urban planners, researchers, civil security practitioners) through surveys or workshops [

26,

27]. This method has the advantage of being more accessible, taking into account the socio-technical context and providing qualitative and quantitative validation based on the experience of local practitioners. However, it does not allow for direct measurement of performance, and the results depend on the profile and representativeness of the experts consulted.

In the case of the architecture proposed by Assoul et al. [

10], simulation was feasible but would have kept the work too conceptual. The manufacture of a prototype or implementation in real conditions would have allowed for robust material validation, but at a financial and logistical cost that was difficult to sustain in the context studied. This is why this work favors an empirical approach based on expert evaluation, adapted to environments with limited resources, and allowing for technical, organizational and contextual feedback on the relevance of the architecture.

3. Materials and Methods

The validation was conducted through a survey administered to a panel of Cameroonian experts in software engineering, distributed systems, urban planning and emergency technologies. The survey aimed to obtain structured feedback on:

The consistency and robustness of the proposed architecture, given the actual constraints in the field;

The

validity of the theoretical analyses summarized in

Table 1;

Expert opinion on the viability and feasibility of the project in the short, medium and long term in contexts comparable to that of Chad;

The prioritization of tasks to be undertaken for the effective implementation of the system;

Strategic recommendations for researchers, engineers, public decision-makers and institutions involved in urban crisis management.

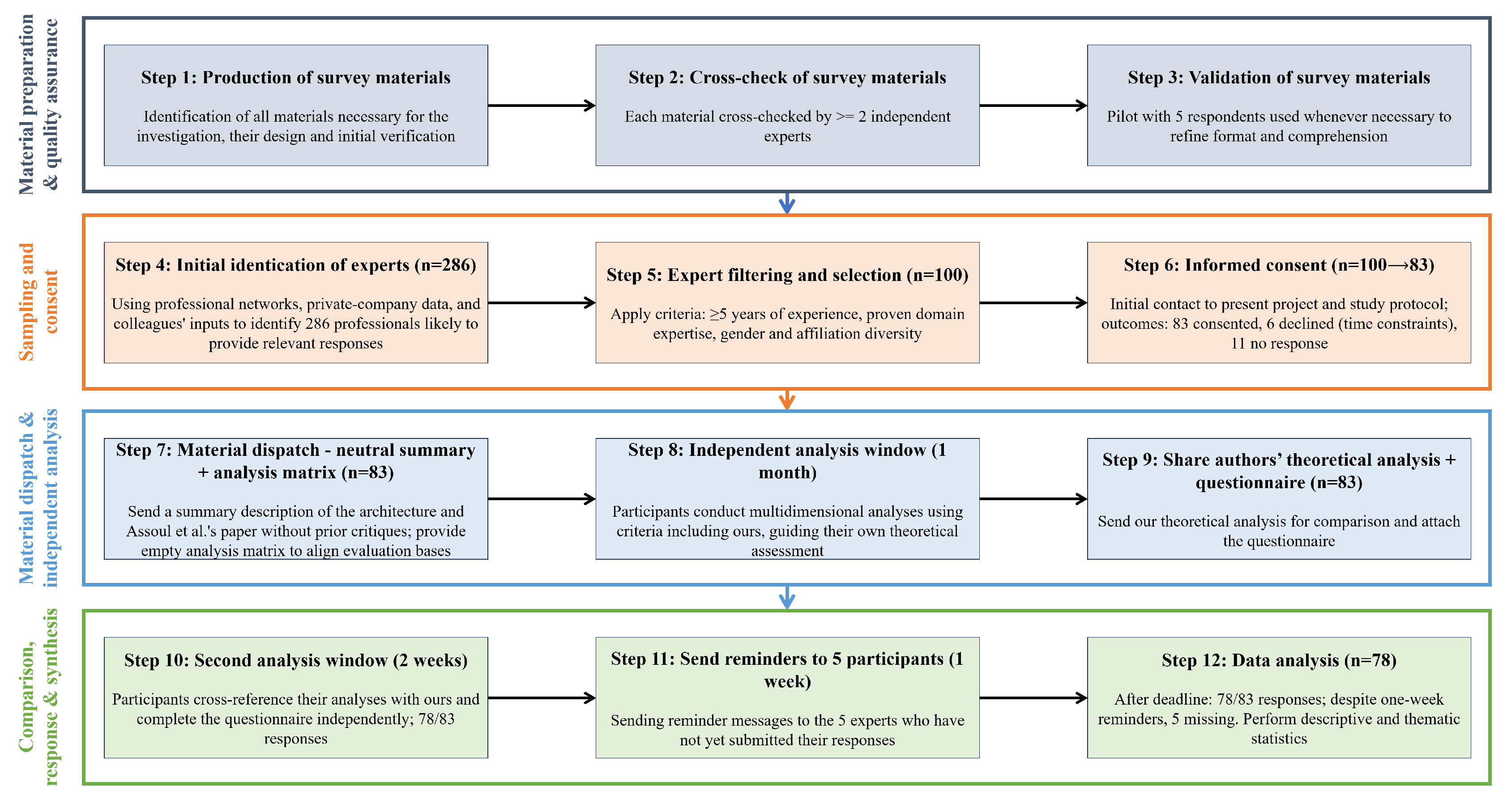

The questionnaire was designed to operationalize the theoretical analysis criteria (temporal efficiency, resource allocation, ease of use) by translating them into indicators that could be assessed by experienced practitioners. The structure of the form included closed-ended Likert scale questions for quantifying perceptions, as well as open-ended questions for gathering qualitative comments and suggestions. The survey was conducted following the methodology summarized in

Figure 2 and described below:

We started by producing all the survey materials (project description, consent form, questionnaire, etc.). Each produced material was then cross-checked by at least two independent experts to ensure their neutrality and accessibility. Each time it was necessary, a pilot phase with five respondents allowed for adjustments to be made to the format and comprehension of the material. (see steps 1 to 3 in

Figure 2)

Using data from professional networks such as LinkedIn

1, Malt

2, etc., data on private companies, and data provided by colleagues, we identified an initial set of 286 professionals likely to provide relevant responses to the survey (step 4);

We then filtered this list to retain only the experts whose profiles met well-defined criteria (including at

least five years of professional experience,

proven expertise in the relevant fields,

diversity of gender and affiliation), as presented in

Section 3.2. A total of 100 experts were selected (step 5);

An initial contact was made with the 100 experts to present the project and the study protocol to them in order to obtain their explicit consent. We obtained the consent of 83 experts; 06 others explicitly stated that they did not have time to participate in the study, while the remaining 11 simply did not respond (step 6);

A summary description of the architecture and the paper of Assoul et al. were sent to the 83 participants without including the critical analyses previously formulated, in order to avoid confirmation bias. However, our analysis matrix was provided to them as an empty form so that they could study the architecture on the same basis as us (step 7);

Participants had one month to study the proposal and carry out their own multidimensional analyses using criteria including those we had selected and which guided our own theoretical analysis (step 8);

We then sent our theoretical analysis to the participants so that they could compare it with their own. We have also attached the questionnaire (step 9);

Participants had an additional two weeks to cross-reference the analyses and complete the questionnaire independently (step 10);

After this new deadline, 78 of the 83 participants submitted their responses to the questionnaire. Despite several reminders over an additional week (step 11), we were unable to obtain responses from the remaining 05 experts. Once the data had been collected, a descriptive and thematic statistical analysis was used to assess the level of validation of the initial hypotheses, draw up a feasibility profile, prioritize the critical steps to be taken for deployment, and identify sectoral recommendations (step 12).

Figure 2.

Methodology used for this study.

Figure 2.

Methodology used for this study.

3.1. Presentation of the Questionnaire and the Evaluated Dimensions

The questionnaire was rigorously designed to ensure the representativeness of responses, the explicit operationalization of key concepts and the comparability of results. It comprised a total of 31 items, organized into six thematic sections, combining closed questions (using Likert scales) and open questions as presented in

Table 2.

The closed questions were mainly formulated as five-point Likert scales (1: "Strongly disagree" to 5: "Strongly agree"), which allowed for the quantification of expert perceptions. The open questions gave respondents the opportunity to explain their answers or make specific recommendations. The content of the questionnaire was developed based on the main focuses of the work presented in [

10], in order to ensure consistency between the initial research objectives formulated by Assoul et al. and the collected data.

Table 3 shows the correspondences between the dimensions evaluated and the elements of the studied system.

The questions were cross-checked by two independent experts before distribution. A pilot phase with five respondents allowed for adjustments to be made to the format and comprehension of the items. The questionnaire was finally anonymized and no data that could personally identify respondents was collected.

3.2. Survey Participant Profiles

The relevance and robustness of empirical validation depend largely on the quality of the respondent panel: its diversity, level of expertise and grounding in the relevant technological contexts. For this study, particular attention was paid to the selection of experts, their representativeness and the institutional and geographical context in which the survey was conducted.

This survey was conducted in Cameroon with the help of some Cameroonian collaborators. This context provided particularly favorable conditions for carrying out this study:

The dense professional network of our Cameroonian collaborators as well as certain professional social media platforms, made it possible to identify and contact experts from various backgrounds (academics, industrialists, practitioners in the field), accelerating the mobilization of participants within a reasonable time-frame;

Cameroon benefits from a dynamic technological ecosystem, including numerous academic institutions, recognized research centers and a network of qualified professionals, often from various African countries and beyond;

These characteristics make it a credible testing ground for evaluating the viability of architectures designed for constrained environments, while offering a variety of perspectives and usage contexts.

A total of 100 experts were initially invited to participate in the survey. Of these, 78 finally responded within the deadline (a response rate of 78%), which is an excellent level of participation for a voluntary qualitative survey. The selection criteria were as follows:

At least five years of professional experience in a relevant field (software engineering, distributed systems, embedded computing, critical architecture, etc.);

Affiliation with a Cameroonian institution at the time of the study (university, technology company, public administration, specialized NGO);

Expertise in technological and organizational issues related to low-infrastructure information systems, particularly in African urban environments.

Table 4 shows the distribution of experts by gender, age group, field of activity, and area of expertise.

Although reflecting an imbalance that is still typical of the technology sector in Africa (30.8% of females vs 69.2% of males), this distribution allows for the inclusion of important female perspectives in the areas of design, deployment and management of technical systems. The overwhelming majority (nearly 75%) are professionals in their active maturity phase, which guarantees feedback based on years of field experience and structured reflection. The panel also covers the entire spectrum of technical disciplines involved in the proposed architecture, which reinforces the methodological validity of the feedback obtained on the technical, functional and operational dimensions. It combines:

Professional and disciplinary diversity, guaranteeing a plurality of analyses;

Considerable cumulative experience, ensuring a critical assessment based on practice;

Direct proximity to the contexts targeted by the architecture, ensuring that the feedback is rooted in the reality of potential uses.

This configuration gives the survey considerable scientific and operational weight in the architecture validation process and is an important lever for formulating appropriate recommendations.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Validation of the Architecture and Its Theoretical Analysis

Analysis of the responses collected from the 78 experts provided robust validation of a set of hypotheses formulated in the architectural proposal, while also revealing certain tensions and suggestions for adjustments. This section presents the aggregated results, distinguishing between:

Feedback on the understanding and structural consistency of the architecture;

Technical validation elements (relevance of choices, consistency of modules, contextual feasibility);

Assessment of the validity of the theoretical analysis presented in

Table 1 of

Section 2.2.1 (strengths, weaknesses, challenges).

4.1.1. Clarity and Understanding of the Architecture

Of the 78 respondents, 72 (92.3%) stated that the summary description provided was clear or very clear, and 69 (88.5%) indicated that they had correctly understood the functional distribution of the four subsystems (SAS, ESN, IOPS, ITGS). Among the few comments made:

12 respondents suggested including graphic illustrations to enhance understanding of the interactions;

6 mentioned a need for concrete examples or usage scenarios to contextualize the orchestration mechanisms.

Conclusion: the architecture is generally perceived as readable, well-structured and intelligible, which confirms its suitability for presentation to technical or institutional stakeholders.

4.1.2. Technical Validation of the Architecture

The assessments of the various technical aspects, collected on a Likert scale (1 to 5: 1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Somewhat agree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree), are summarized in

Table 5.

The arithmetic mean is used to obtain a central measure of participants’ perceptions on each item (column Mean in

Table 5). For a given item, the formula is:

where:

n is the number of experts that responded to the item,

is the given mark to the item by the i-th expert.

The standard deviation shows differences in responses around the average (Standard deviation column in

Table 5). It helps us figure out if respondents are pretty much in agreement or if they have different opinions:

where:

n the number of experts that responded to the item,

is the mean of the item,

is the response of the i-th expert,

A low standard deviation (< 0.5) indicates that the responses are very consistent around the mean,

A higher standard deviation (> 0.8) indicates greater variability in opinions.

Conclusion: these results highlight strong technical validation, with average scores all above 4/5. The architecture is perceived as technologically credible, consistent and adaptable to other African contexts. However, several respondents pointed out:

The potential complexity of deploying edge servers, particularly in terms of maintenance and energy resilience;

The need to calibrate the technological choice to local constraints, for example by suggesting hybrid configurations combining edge/fog and lightweight cloud.

4.1.3. Validation of Theoretical Analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Challenges)

The responses to the section devoted to theoretical analysis confirmed most of the hypotheses formulated in

Table 1 of

Section 2.2.1, but also highlighted certain differences in perception or gaps to be filled.

74 respondents (94.9%) consider that the strengths identified in the analysis (reduced response time, modularity, adaptability to limited infrastructure) are realistic and well formulated;

Several respondents emphasized that the system’s ability to operate autonomously at the local level, thanks to edge computing, was a major technological advantage;

65 respondents (83.3%) consider the weaknesses identified to be accurate and well defined;

-

However, some suggested adding:

- –

Dependence on accurate and up-to-date mapping data;

- –

The hidden costs of inter-system synchronization;

- –

The management of decision-making conflicts in the event of partial failures.

The majority (89.7%) considered that human, logistical and political challenges had been adequately addressed, particularly those related to training, maintenance and inter-institutional integration;

A few suggestions were made to further explore the regulatory dimension, particularly with regard to data protection, the regulation of emergency communications, and the legality of autonomous sensor deployments in public spaces.

Conclusion: the survey confirmed that the proposed architecture is:

Technically sound and functionally understandable;

Compatible with environments with limited infrastructure, subject to certain adaptations;

Adequately analysed in terms of strengths, weaknesses and challenges.

Feedback from experts reinforces the scientific and operational legitimacy of the approach, while calling for the gradual refinement of certain aspects (e.g., regulatory aspects, technological calibration, dynamic mapping).

4.2. Project Feasibility and Viability Assessment

Beyond the conceptual and technical validity of the architecture, it is essential to examine its practical feasibility and socio-economic viability in the context of sub-Saharan African countries. This section analyses expert feedback on the actual possibility of implementing, supporting and maintaining such a solution in an institutional, economic, human and technological framework similar to that of Cameroon or Chad.

4.2.1. General Perception of Feasibility

When asked directly about the feasibility of implementing the system in the short or medium term:

19 respondents (24.4%) believe that the system is entirely feasible with current resources;

45 respondents (57.7%) consider it to be partially feasible, but only with gradual adjustments;

14 respondents (17.9%) consider its implementation to be difficult or even unlikely in the short term due to structural constraints.

Conclusion: a large majority (over 80%) consider the project feasible, although the gradual nature of its implementation is unanimously recommended. The modular deployment strategy is considered to be in line with this logic of incremental adaptation.

4.2.2. Identified Barriers to Implementation

The main obstacles identified to the feasibility of the project are summarized in

Table 6 below, based on the multiple choices offered to respondents.

The financial aspect is by far the most frequently cited, particularly in relation to the acquisition, integration and maintenance of on-board equipment. The shortage of local specialist skills is also seen as a major obstacle, highlighting the need to train and retain engineers locally.

4.2.3. Identified Facilitating Factors

Despite the identified obstacles, experts also highlighted promising factors that could facilitate the project’s implementation:

The existence of dynamic academic pools training high-level engineers;

The growing capacity of certain local companies to integrate IoT and cloud technologies;

Growing openness of public authorities to intervention technologies (video surveillance systems, SMS alerts, GIS systems, etc.);

Growing inter-institutional collaboration between universities, start-ups and local authorities.

These factors argue in favor of implementation in a pilot environment, supported by partnership-based governance (university – city – businesses).

4.2.4. Economic Sustainability and Long-Term Viability

With regard to economic viability, the responses are more nuanced:

29 respondents (37.2%) consider the system to be economically viable provided it is rolled out in a modular and gradual manner;

21 respondents (26.9%) consider it to be viable if supported by public or international funding;

28 respondents (35.9%) express doubts about economic viability without a clear business model or recurring subsidies.

In terms of technical sustainability, a majority agree that technical resilience depends on the establishment of a local maintenance structure (FPGA engineers, edge specialists, etc.), hence the importance of creating national or regional centers of expertise.

4.2.5. Mentioned Conditions for Success

The respondents identified several levers to maximize the feasibility and viability of the system:

Rapid prototyping of a use case in a medium-sized city (e.g. Douala, Maroua, N’Djamena);

Deployment using public funds or through public-private partnerships;

Integration into a multidisciplinary action research project to bring together expertise (urban planning, IT, law, health);

Capitalization on existing resources (GIS mapping, 4G/5G networks, geolocation systems);

Institutional support with a communication and training strategy for decision-makers.

The survey reveals that the project is perceived as generally feasible, subject to phased planning and strong local anchoring in terms of training, governance and engineering. Potential failure factors have been identified and can be mitigated through a realistic, gradual and partnership-based approach. Long-term viability will depend on the ability to create a resilient technical and institutional ecosystem and to mobilize appropriate financial and human resources on a sustainable basis.

4.3. Task Prioritization for Operationalization

One of the fundamental objectives of the survey was to identify, through expert feedback, the critical and priority steps to be taken to make the proposed architecture operational. The aim here was to move from conceptual validation to a pragmatic roadmap, structured around technical, organizational and institutional tasks.

Section 6.1 of the questionnaire provided respondents with a list of 15 key tasks, divided into four categories: technological development (SAS, ESN, IOPS, ITGS, interoperability), operational preparation (infrastructure, data, mapping), organizational structuring (human resources, maintenance, training) and institutional support (legal framework, awareness-raising, partnership). It should be noted that these 15 tasks were intended to be large enough to constitute an entire project or a significant phase of the main project; and thus, each of them can be refined into several thousand tasks. Respondents were asked to assign each task a priority rating on a scale of 1 (high priority) to 5 (low priority). The analysis consisted of calculating the following for each task:

Table 7 shows all the tasks submitted for evaluation by the experts, along with statistics on their opinions regarding the priority level of each task.

The results reveal a clear hierarchy of initial priorities around the following areas:

- 1.

Rapid implementation of a minimum technological foundation, with an emphasis on SAS, ESN and FPGA-based modules;

- 2.

Availability of reliable mapping data, an essential requirement for route calculation and navigation;

- 3.

Formalization of orchestration and communication protocols between subsystems (functional interoperability);

- 4.

Structuring of the project team, with cross-functional skills (sensors, edge, algorithms, user interface);

- 5.

Real-world testing through a limited but representative pilot program.

Tasks with moderate priority are more related to the supporting environment (legal framework, training, governance). This reflects a vision in which technological initiation determines institutional acceptance. It should be noted that even the lowest priority tasks exceed 50% high priority rate, reflecting their strategic importance over time, albeit less immediate.

Based on these results, it is possible to propose an initial roadmap for operationalization:

- 1.

Short term: formation of the project team, data structuring, development of the SAS, edge deployment, prototyping of the ESN modules;

- 2.

Medium term: field testing, development of the IOPS, ITGS integration, securing exchanges, initial institutional partnerships;

- 3.

Long term: regulation, shared governance, continuing education, maintenance, industrialization of the system.

Qualitative feedback indicates that certain tasks are interdependent: for example, data collection and inter-module orchestration cannot be separated. This calls for a partial coupling approach rather than a strict, linear hierarchy.

4.4. Strategic Recommendations from the Experts

The responses to the open-ended questions in the sixth section of the questionnaire provided a wealth of rich, nuanced and contextualized recommendations. These recommendations are aimed at several categories of stakeholders: design engineers, researchers and academics, and institutional decision-makers. These recommendations were analyzed using an inductive thematic coding method, followed by categorization by type and recipient.

Table 8 summarizes these recommendations for each intended audience. The experts’ recommendations go beyond simple technical advice: they form a collective strategy for realistic implementation, rooted in contemporary African constraints. They call for joint mobilization: engineers, to ensure technical robustness and frugality; researchers, to structure innovation and promote its transfer; and finally, decision-makers, to create an institutional environment conducive to adoption. This convergence highlights the systemic relevance of the project, at the crossroads of technology, research, and governance.

5. Critical Analysis and Perspectives

5.1. Critical Analysis of the Methodology

The applied methodology in this study has several strengths. First, the involvement of experts from various disciplines enabled a multidimensional assessment of the studied architecture. This interdisciplinary approach enriched the analysis by covering technical, organizational, and societal aspects. Another important advantage lies in the operationalization of abstract theoretical criteria such as temporal efficiency, resource allocation, and ease of use, into measurable indicators integrated into the questionnaire. This methodological choice facilitated the collection of structured opinions and the comparison of responses. In addition, the combination of closed questions (Likert scales) and open questions made it possible to obtain both quantitative data and qualitative recommendations, thus enhancing the depth of the evaluation. The initial selection of a large pool of 286 professionals, who were then filtered according to explicit criteria, contributed to the credibility of the final sample. Finally, the anchoring in local contexts ensured the strong contextual relevance of the results obtained.

However, certain limitations should be highlighted with a view to improvement. The selection of participants, based on online professional networks and institutional contacts, may have introduced a representativeness bias by under-exposing relevant practitioners who are less visible on these platforms. In addition, while the aggregation of responses reveals an overall positive consensus, the study does not highlight any significant differences between subgroups of experts (e.g., by discipline or level of experience), which would have allowed for a more refined interpretation of the results. Finally, the exclusive use of the questionnaire, without methodological triangulation (e.g., through in-depth interviews, simulations or an iterative Delphi approach), limits the consolidation of a robust consensus among experts.

5.2. Critical Analysis of the Obtained Results

The results of this survey of 78 experts make an important contribution to the validation of the architecture. A large majority of respondents found the description clear and understandable (over 90%), confirming the model’s readability and its potential for dissemination among technical and institutional stakeholders. The technical evaluation of the various modules also led to generally favorable assessments of the internal consistency of the architecture and its feasibility in the context under consideration. These findings reinforce the soundness of the initial theoretical analyses. In addition, the qualitative comments significantly enrich the validation by highlighting concrete areas for improvement.

However, certain limitations should be noted. The external validity of the results can be strengthened: while the conclusions are particularly relevant to the Cameroonian and Chadian contexts, their generalization to other urban environments with different infrastructures and modes of governance should be approached with caution. In addition, although based on recognized expertise, the judgments collected are essentially subjective perceptions. Their value therefore remains indicative and would benefit from being supplemented by empirical validation, for example through experiments on prototypes or case studies. Finally, several respondents pointed out that the architecture remains relatively abstract and would benefit from being supported by concrete examples or realistic use cases, which would be more likely to convince practitioners and decision-makers.

5.3. Perspectives

The findings of this study point to several avenues for further research and development. From a methodological perspective, one initial approach would be to supplement the validation process with complementary methods, such as prototype testing, real-world case studies, or iterative Delphi-type exercises aimed at strengthening consensus among experts. These extensions would make it possible to go beyond the perceptual dimension of the evaluation to test the robustness and operational effectiveness of the architecture in realistic urban crisis management scenarios. A differentiated analysis of responses, taking into account the profiles of the experts (disciplines, years of experience, sectors of activity), would also be a way of identifying the most significant convergences and divergences.

On a technical level, several avenues can be explored based directly on participants’ suggestions. The integration of more detailed graphical representations, as well as the development of usage scenarios or practical cases, would promote understanding and adoption of the system by a variety of stakeholders, ranging from engineers to public decision-makers. In addition, the feasibility of the architecture would benefit from being tested through the implementation of modular prototypes, allowing the effective performance of each subsystem (SAS, ESN, IOPS, ITGS) to be evaluated in simulated or controlled environments. Such experiments would pave the way for gradual adjustments, while validating theoretical assumptions on a solid empirical basis. Finally, studying the transferability of the architecture to other urban contexts with different infrastructures or governance constraints is a necessary extension. Overall, these perspectives demonstrate the relevance of the developed framework and highlight the need to continue working toward applied and broader validation.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we conducted an empirical evaluation of an architecture that uses IoT sensors, edge servers with FPGAs, and distributed algorithms to optimize emergency response in an resource-constrained urban areas. The survey of 78 experts confirmed the technical and operational relevance of this approach, particularly in terms of reducing response times and strengthening coordination between actors, while identifying critical challenges related to interoperability, urban data structuring, financial viability, and multi-stakeholder governance. Methodologically, the study demonstrated the value of a multidimensional assessment based on interdisciplinary expertise and the transformation of theoretical criteria into concrete indicators. However, the results remain subject to subjective perceptions and would benefit from being consolidated through empirical experimentation, using prototypes, case studies, or Delphi-type approaches. Ultimately, this contribution emphasizes that the effectiveness of emergency systems’ architectures does not rely solely on technological innovations, but also on their adaptation to local realities and on consistent integration with organizational, economic and societal dimensions. The identified perspectives pave the way for future work aimed at implementing robust and truly operational solutions for resource-constrained African cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zekeng; methodology, Zekeng, Jagho and Nguimeya; validation, Zekeng, Nguimeya, Jagho, Tahir, Mahmoud and Assoul; formal analysis, Assoul, Zekeng, Jagho and Nguimeya; investigation, Assoul, Zekeng and Jagho; resources, Nguimeya, Assoul and Zekeng; data curation, Jagho, Zekeng, Nguimeya and Assoul; writing—original draft preparation, Zekeng, Jagho, Nguimeya and Assoul; writing—review and editing, Zekeng, Jagho, Nguimeya and Assoul; visualization, Assoul, Zekeng, Nguimeya and Jagho; supervision, Zekeng; project administration, Tahir and Mahmoud; funding acquisition, Assoul, Zekeng, Tahir and Mahmoud. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in this survey was entirely voluntary. All invited experts were informed of the purpose of the study, the type of data collected, and the intended use of the results for scientific research. Prior to completing the questionnaire, participants were provided with an information sheet outlining their rights, including the right to withdraw at any point without providing justification. Consent was obtained from all participants before submission of their responses. No personally identifying information was collected, and all data were analyzed in aggregate to preserve confidentiality and anonymity.

Data Availability Statement

The survey data underlying this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costa, D.G.; Peixoto, J.P.J.; Jesus, T.C.; Portugal, P.; Vasques, F.; Rangel, E.; Peixoto, M. A Survey of Emergencies Management Systems in Smart Cities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 61843–61872. [CrossRef]

- Elvas, L.B.; Mataloto, B.M.; Martins, A.L.; Ferreira, J.C. Disaster Management in Smart Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 819–839. [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, A.M.; Alsmadi, M.K.; Baareh, A.K.; Almarashdeh, I.; Abouelmagd, H.; Ahmed, O.S.S. Emergent situations for smart cities: A survey. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2019, 9, 4777–4787. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, P. Smart Cities: A Global Perspective. India Quarterly 2016, 72, 177–191. [CrossRef]

- Jagho Mdemaya, G.B.; Foko Sindjoung, M.L.; Zekeng Ndadji, M.M.; Velempini, M. HERCULE: High-Efficiency Resource Coordination Using Kubernetes and Machine Learning in Edge Computing for Improved QoS and QoE. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 72153–72168. [CrossRef]

- Boutros, A.; Betz, V. FPGA Architecture: Principles and Progression. IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 2021, 21, 4–29. [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, M.; Del Sozzo, E.; Rabozzi, M.; Di Tucci, L.; Williams, S.; Sciuto, D.; Santambrogio, M.D. A Comprehensive Methodology to Optimize FPGA Designs via the Roofline Model. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2022, 71, 1903–1915. [CrossRef]

- Eneh, A.; Arinze, U.C. Comparative analysis and implementation of Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm for emergency response and logistic planning. Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) 2017, 36, 876–888. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, T. FPGA Implementation of A* Algorithm for Real-Time Path Planning. International Journal of Reconfigurable Computing 2020, 2020, 8896386. [CrossRef]

- Aziz Assoul, M.A.; Tahir, A.M.; Mahmoud, T.; Jagho Mdemaya, G.B.; Zekeng Ndadji, M.M. A Comprehensive System Architecture using Field Programmable Gate Arrays Technology, Dijkstra’s Algorithm, and Edge Computing for Emergency Response in Smart Cities. ParadigmPlus 2024, 5, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Wang, X. Dijkstra Algorithm Based Building Evacuation Edge Computing and IoT System Design and Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Progress in Informatics and Computing (PIC), 2021, pp. 281–287. [CrossRef]

- Omomule, T.G.; Durodola, B.L.; Orimoloye, S.M. Shortest route analysis for road accident emergency using dijkstra algorithm and fuzzy logic. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing 2019, 8, 64–73.

- Chen, Y.Z.; Shen, S.F.; Chen, T.; Yang, R. Path Optimization Study for Vehicles Evacuation based on Dijkstra Algorithm. Procedia Engineering 2014, 71, 159–165. [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Dou, Y.; Li, R.; Xia, F. An FPGA Implementation for Solving the Large Single-Source-Shortest-Path Problem. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2016, 63, 473–477. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, I.; Castillo, J.; Pedraza, C.; Sanchez, C.; Martinez, J.I. Parallel Implementation of the Shortest Path Algorithm on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2008 4th Southern Conference on Programmable Logic, 2008, pp. 245–248. [CrossRef]

- Esteves, L.T.C.; Oliveira, W.L.A.d.; Farias, P.C.M.d.A. Analysis and Construction of Hardware Accelerators for Calculating the Shortest Path in Real-Time Robot Route Planning. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayanan, M. The Emergence of Edge Computing. Computer 2017, 50, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Zhang, Y.; Taherkordi, A.; Skeie, T. Mobile Edge Computing: A Survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 5, 450–465. [CrossRef]

- McEnroe, P.; Wang, S.; Liyanage, M. A Survey on the Convergence of Edge Computing and AI for UAVs: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 15435–15459. [CrossRef]

- Rosayyan, P.; Paul, J.; Subramaniam, S.; Ganesan, S.I. An optimal control strategy for emergency vehicle priority system in smart cities using edge computing and IOT sensors. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 26, 100697. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Han, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Li, J. A Survey on UAV Applications in Smart City Management: Challenges, Advances, and Opportunities. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 8982–9010. [CrossRef]

- Seong, K.; Jiao, J. Is a Smart City Framework the Key to Disaster Resilience? A Systematic Review. Journal of Planning Literature 2024, 39, 62–78. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Ye, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, Y.; Shen, X.S. Edge Graph Intelligence: Reciprocally Empowering Edge Networks With Graph Intelligence. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2025, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Jagho Mdemaya, G.B.; Zekeng Ndadji, M.M.; Foko Sindjoung, M.L.; Velempini, M. Efficient Load-Balancing and Container Deployment for Enhancing Latency in an Edge Computing-Based IoT Network Using Kubernetes for Orchestration. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zekeng Ndadji, M.M.; Tchoupé Tchendji, M. A Software Architecture for Centralized Management of Structured Documents in a Cooperative Editing Workflow. In Proceedings of the Innovation and Interdisciplinary Solutions for Underserved Areas. Springer, 2018, pp. 279–291. [CrossRef]

- Rodak, A.; Jamson, S.; Kruszewski, M.; Pędzierska, M. User requirements for autonomous vehicles–A comparative analysis of expert and non-expert-based approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 AEIT International Conference of Electrical and Electronic Technologies for Automotive (AEIT AUTOMOTIVE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Tora, T.T.; Andarge, L.T.; Abebe, A.T.; Utallo, A.U.; Meshesha, D.T.; Wubie, A.F. An expert-based assessment of early warning systems effectiveness in South Ethiopia Regional State. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6, 188. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).