1. Introduction

Driven by the need for a more sustainable transportation sector, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and dependency on fossil fuels, Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) have gained major recognition in the last decades. Their core component, the battery, is the subject of intensive research and development. The most common battery type in contemporary electric vehicles is lithium-ion, which is adopted due to their high energy density [

1]. While improvements in battery capacity and charging speed are crucial for extending range in transportation to match conventional vehicles, they often lead to an increase in battery, and consequently, vehicle weight. Current BEVs are heavier than their internal combustion engine counterparts, therefore opting for lightweight materials in the design of the vehicle remains crucial [

2]. Composite materials and more specifically, composite battery housings offer an excellent solution, providing superior weight-specific mechanical performance, enhanced corrosion resistance and thermal insulation compared to traditional aluminum alloy or steel housings [

3].

Thermoset matrices have been the state-of-the-art choice compared to their thermoplastic counterparts, due to their easier fiber impregnation, lower processing temperatures, and lower cost [

4]. However, thermoplastic resins present greater fatigue resistance, superior damage tolerance under impact, and shorter processing times. Also, thermosets undergo irreversible chemical formation during curing, which permanently sets their molecular structure, while thermoplastics can be remolded while fully retaining their original composition and properties, offering significant benefits for recyclability [

5]. Essentially, there is a need for a thermoplastic resin that exhibits good mechanical properties and room-temperature curing but also be compatible with liquid processing techniques. These requirements led to the development of a new acrylic resin by Arkema company, called Elium. This low-viscosity, in-situ polymerizable thermoplastic resin effectively cures at room temperature and is suited for both Vacuum Assisted Resin Infusion (VARI), Resin Transfer Moulding (RTM), as well as Sheet Moulding Compound (SMC) processes [

6,

7].

The composite housing design needs to include reliable protection for internal electronics and battery cells. This requires shielding from external loads, e.g. physical impacts, and various environmental influences, such as extreme temperatures, which can cause thermal runaway, the catastrophic overheating of the battery that can lead to fire [

8,

9]. Consequently, the impact safety of Battery Pack Systems (BPS) is of great importance [

10,

11]. Impact events, such as those from road debris, can cause nonvisible internal damage to conventional unidirectional (UD) composites, which reduces their mechanical performance. Discontinuous fiber composites, such as SMCs, appear to be a suitable substitute, providing improved resin flow and complex geometry manufacturing of components at a reduced cost [

12]. Within the existing literature, numerous impact studies have been conducted on continuous carbon and glass fiber composites. Carbon fibers are recognized for their high strength, whereas glass fibers exhibit greater ductility, which allows glass fibers to enhance energy absorption before failure, consequently improving the overall impact tolerance of the composite [

13]. However, a significant gap exists in comprehensive experimental data and numerical simulations needed to thoroughly evaluate the impact resistance of Battery Pack Structures (BPS) [

14,

15]. Research on BPS safety predominantly concentrates on cells and module’s electrochemical degradation. Regarding their mechanical integrity, limited impact scenarios including frontal, side, and rear impacts have been examined [

16]. Chen et al. investigated the dynamic response of lithium-ion battery packs under high-speed impact, developing models to predict internal failure mechanisms under mechanical abuse [

17,

18]. Xu et al. examined the influence of State of Charge (SOC) on the mechanical response of lithium-ion batteries during impact [

19]. More recently, bottom crashworthiness has gained attention, with researchers utilizing composite materials and structures to enhance impact resistance [

10]. Xia et al. introduced a new analysis method designed to evaluate potential damage of battery packs from road debris [

20]. Also, explicit finite element analysis (FEA), using the LS-DYNA software, has been employed to model the response of cylindrical lithium-ion battery cells to lateral impact [

11] and to simulate the ground impact of lithium-ion battery packs in electric vehicles [

21,

22,

23].

Concerning the dynamic response of battery enclosures, numerical simulations to predict the deformation of steel battery housings during frontal low-speed impacts have been employed using LS-DYNA software [

16]. Ground impact simulations have been developed for fiber metal laminate (FML) battery enclosures, investigating various impact velocities (35–41 m/s), with experimental tests carried out to validate these models [

24]. A crash simulation analysis focusing on a battery pack that integrates cylindrical cells within an ABS enclosure has also been carried out using the Radioss solver, aiming to compare the impact responses of the battery pack system both in the presence and absence of shock absorbers [

25]. Also, side pole impact simulations on carbon fiber reinforced battery enclosures, have been carried out, modeled with VPS software and 2D shell elements [

3,

10]. Another study examined the design optimization of a battery pack enclosure (BPE) constructed from steel, aluminum, and carbon fiber composite to enhance its impact resistance. This research used a multi-objective optimization approach, integrating numerical models and analytical methods, to reduce BPE's mass and maximum deformation. For this, a modified TOPSIS method was applied to determine the most important design parameters [

26].

To the authors’ knowledge, a limited number of studies, both numerically and experimentally, focusing on the impact performance of SMCs and discontinuous fiber composites has been investigated and no prior work on the impact response of Elium glass fiber SMC battery housings has been reported. In this work, a novel thermoplastic battery enclosure is subjected to ground and frontal pole impact, with parametrically increasing the impact velocity. In

Section 2, the SMC material is characterized in tension, compression, shear and three-point bending, and its mechanical properties are calculated. Also, the experimental procedure of drop tower impact tests is described, for both thermoplastic plates and the battery housing, conducted at impact energies of 7.5 J and 30 J.

Section 3 outlines the numerical modeling in detail. This includes the development of two models intended to validate the drop tower test results for both the SMC plate and the housing, as well as the development of the parametric ground and crash impact simulations.

Section 4 includes the results of numerical modelling, that validate the impact response of the housing. Using the validated model, the results of the parametric analysis, for ground and pole impact, are discussed. In

Section 5, the work of this paper is summarized.

2. Experimental

2.1. Geometry and Material

The battery housing consists of two primary components—the lid and the main enclosure—both fabricated from a novel thermoplastic composite material. The matrix is based on Arkema Elium MC 590, an acrylic resin, modified with Martinal ATH (aluminum hydroxide) to impart fire resistance. The composite is reinforced with 20 wt% chopped glass fibers (JM Multistar 272), providing mechanical strength and stiffness. The housing has maximum external dimensions of 440 mm × 300 mm × 89 mm and features four symmetrical support legs at the bottom, each measuring 12 mm × 12 mm × 2 mm (width × length × height), as illustrated in the CAD drawing of

Figure 1. Due to the manufacturing process, the wall thickness of the housing varies between 3.0 and 3.5 mm. The material is produced in the form of a Sheet Molding Compound (SMC)—a specialized type of prepreg suitable for compression molding. The complete manufacturing process, from the formulation of semi-finished SMC sheets to the compression molding of flat plates and the final housing component, was carried out at Fraunhofer ICT in Pfinztal, Germany [

2].

2.2. Mechanical Characterization of the SMC Composite

To characterize the short fiber SMC composite, tension, compression, shear and three-point bending tests were conducted in accordance with relevant ASTM standard test methods. For each mechanical test, a minimum of five specimens were prepared and tested under controlled environmental conditions of 23 °C and 50% relative humidity, in compliance with the respective standard procedures. Strain measurements were obtained using bonded strain gauges with a resistance of 350 Ω. All tests were carried out using a 100 kN MTS Universal Testing Machine equipped with hydraulic grips. Consistent with the nature of the composite—comprising randomly oriented short glass fibers—specimens were tested without end tabs, as permitted by the applicable ASTM standards. The testing configurations and the mounted specimens are shown in

Figure 2. A summary of the testing procedures and associated parameters is provided in

Table 1.

Tensile properties of the composite material were evaluated in accordance with ASTM D3039. Flat strip specimens with a constant rectangular cross-section were used, measuring 250 mm × 25 mm × 2.5 mm, with a gage length of 150 mm. The specimens were mounted in the universal testing machine and subjected to tensile loading at a standard crosshead displacement rate of 1 mm/min. Strain gauges with a resistance of 350 Ω were affixed on both faces of the specimen—one aligned in the longitudinal direction and the other in the transverse direction. These measurements enabled the calculation of the tensile modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio, based on the stress–strain data and using equations specified in ASTM D3039. Additionally, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the material was determined as part of the test output.

Compression testing was conducted in accordance with ASTM D3410. Rectangular flat specimens were prepared with dimensions of 140 mm (length) × 25 mm (width) × 2.5 mm (thickness) and a gage length of 12 mm. The gage length was determined based on the specimen thickness to ensure sufficient space for the placement of strain gauges in the longitudinal direction, while also minimizing the risk of Euler buckling within the test section. Specimens were mounted in the testing machine and compressed at a constant crosshead displacement rate of 1 mm/min. The test yielded measurements of ultimate compressive strength and compressive modulus.

Flexural testing was carried out according to ASTM D790, using a three-point bending configuration. Specimens had a rectangular cross-section with dimensions of 95 mm × 18 mm × 4.5 mm and were tested using a support span-to-depth ratio of (16 ± 1):1, as recommended by the standard. The crosshead speed was set to 2.2 mm/min. This procedure enabled the evaluation of key flexural properties, specifically the flexural strength and flexural modulus.

Shear properties were evaluated in accordance with ASTM D7078, which utilizes v-notched rail shear specimens. In this method, the specimens are clamped between two loading fixtures and subjected to tensile loading, which induces a relatively uniform shear stress distribution in the reduced cross-section of the gage area, ultimately resulting in shear failure. To measure shear strain, two strain gauges are applied at ±45° angles relative to the loading direction. The test was performed at a crosshead speed of 2 mm/min. The test results were used to determine the shear modulus and ultimate shear strength of the composite material.

2.2.1. Experimental Results

Figure 3 presents the force–displacement curves obtained from the mechanical testing procedures, while

Table 2 summarizes the corresponding mechanical properties derived from each test. The experimental results demonstrate that the short fiber SMC composite exhibits a transversely isotropic mechanical response, characterized by comparable properties in both the in-plane and through-thickness directions. This behavior is consistent with the random orientation of the chopped glass fibers within the matrix, contributing to a relatively uniform distribution of mechanical performance across different loading directions. The failure modes of the specimens are illustrated in

Figure 4.

The tensile behavior of the composite material exhibits a bi-linear force–displacement response, as illustrated in

Figure 4(a). The initial linear segment of the curve corresponds to the elastic region, primarily governed by the presence of a high concentration of aluminum hydroxide (Al(OH)₃) within the thermoplastic matrix. The Al(OH)₃ filler acts as a stress concentrator, restricting the mobility and alignment of the polymer chains under tensile loading. This interaction results in a stiffening effect, which enhances the initial stiffness and elastic modulus of the composite. However, this same mechanism contributes to a reduction in ductility, as the restricted polymer chain mobility limits the material's ability to undergo plastic deformation. Consequently, the composite exhibits a more brittle response in the post-elastic region, consistent with the reduced strain-to-failure observed in the experimental data [

27]. However, with the increase of the filler content, the continuity of the polymer matrix decreases, resulting more in Al(OH)

3 particle-particle interaction rather than particle-resin interaction [

28]. The formation of particle clusters, also, increases porosity and has a degrading effect on interface adhesion, which accelerates crack propagation and can lead to poor mechanical attributes [

29]. The linear region, following the initial one, shows a drastic drop of the incline of the curve, thus a smaller tangent modulus (3.68 GPa) compared to the elastic modulus (12.26 GPa). This can be attributed to the thermoplastic resin, which gradually becomes less effective as the reinforcements begin to dominate the material's response [

30]. The softening in the mechanical response is also developed due to matrix cracking and poor filler-resin interface bonding. The linear behavior is maintained until the material reaches a brittle failure. As illustrated in

Figure 4(a), the failure mechanisms due to tension exhibit matrix cracking, fiber breakage and fiber pullout.

Under compressive loading, fiber breakage is not the primary failure mode [

6]. Instead, the material tends to undergo degradation due to crack initiation and propagation, as well as debonding between the fibers and matrix. Due to the thermoplastic behavior of the Elium resin, that has a low yield point [

7], the initial elastic region, shown in

Figure 4(b), is not easily noticeable, because of the early development of microcracks resulting in non-linearity. Following the crack propagation, the ultimate compressive strength of the SMC is achieved, and a sudden drop of the load is observed, leading to the ultimate fracture of the composite.

Figure 4(b) displays the specimens after fracture, highlighting matrix cracking and fiber debonding as the main failure mechanisms.

Concerning the shear response of the composite material, as illustrated in

Figure 4(c), the initial behavior is linear elastic, enabling the determination of the shear modulus. As strain increases, the material exhibits a non-linear response, attributed to the initiation and growth of micro-cracks within the thermoplastic resin matrix—a characteristic behavior of Elium-based composites. At higher deformation levels, a visible diagonal crack forms at the notch root, as shown in

Figure 4(c), leading to a slight reduction in the load response just prior to ultimate failure.

Regarding the three-point bending results, the composite exhibits high flexural strength, indicating effective interfacial bonding between the matrix and the reinforcing fibers [

6]. In terms of flexural failure modes,

Figure 4(d) shows that crack initiation consistently occurs on the tension side of the specimen, with fracture localized at the mid-span, corresponding to the region of maximum bending stress.

2.3. Drop Tower Impact Tests

Low-velocity impact tests were conducted using an INSTRON 9250HV drop tower machine, as shown in

Figure 5. A 45 kN load cell was employed to accurately record the force exerted by the impactor during each test. The system is equipped with an anti-rebound mechanism to prevent multiple impacts on the specimen, ensuring consistency in test results. All tests were performed using a steel impactor with a mass of 6.795 kg, while the impact energy was controlled by adjusting the drop height, following the principle of energy conservation. The impactor was fitted with a 16 mm diameter hemispherical tip, in compliance with ASTM D7136 guidelines, to ensure standardized testing conditions. The impactor was mounted on a crosshead, which lifted it to the predetermined height before releasing it for free-fall along two vertical guide columns.

The data acquisition system records the load vs. time response for each impact event. The impact velocity is measured immediately prior to contact using a photoelectric diode and flag system. This system employs a flag attached to the drop weight, consisting of two prongs spaced 1 cm apart. As the prongs pass through the photo-diode sensor, the obstruction of the light beam generates electrical signals. The system calculates the time interval between the leading edges of the two prongs as they interrupt the beam. Given the known distance between prongs (1 cm) and the measured time, the impact velocity of the drop weight is accurately determined using basic kinematic principles. This method ensures precise velocity measurement at the moment just before impact.

Impact tests were performed at two energy levels, 7.5 J and 30 J, corresponding to impact velocities of 1.486 m/s and 2.972 m/s, respectively. Two SMC plate specimens were tested at each energy level. The plates were cut to dimensions of 165 mm × 100 mm × 2.5 mm and positioned on a 250 mm × 250 mm × 30 mm steel support base featuring a 130 mm × 70 mm central opening. The specimens were secured using four symmetrical clamps to ensure proper fixation during impact. For the battery housing, testing was conducted at an impact energy of 30 J. A custom fixture was designed to maintain the housing in a fixed position throughout the test. A steel plate measuring 540 mm × 400 mm was placed beneath the housing to provide structural support, while a second steel plate of the same dimensions, containing a 450 mm × 280 mm cut-out, was positioned on top. The two plates were clamped together using eight bolts, each with an 18 mm diameter, ensuring a rigid and repeatable setup. Following each test, the damage depth was measured at the center of the specimen, where the most significant deformation or damage consistently occurred.

3. Numerical Modeling

In this study, all geometries were designed and meshed using ANSYS Workbench, while the impact simulations were carried out using the LS-DYNA explicit solver. Explicit time integration is particularly well-suited for problems involving significant nonlinearities, such as complex contact interactions and nonlinear material behavior, which are common in impact scenarios. However, explicit methods require a small-time step to maintain numerical stability and ensure accurate results. The time-step size is governed by the transit time of an acoustic wave through the smallest element in the model, as defined by the shortest characteristic length. This is a function of the material’s elastic properties—specifically, the Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, density, and speed of sound [

31]. According to the Courant condition, information should not propagate through more than one element per time step; otherwise, numerical instabilities may arise, leading to spurious oscillations and non-physical results. To enhance stability, the Time Step Scale Factor (TSSFAC), typically set at 0.90, was conservatively reduced to 0.70 in this study. This ensures a safer margin for accurate and stable calculations. For the structural discretization, solid elements were used with ELFORM = 1, a reduced integration formulation featuring a single integration point. While computationally efficient, this formulation is susceptible to hourglass modes, which require stabilization. To address this, stiffness-based hourglass control (Type 4) was employed. This control method is particularly effective in impact simulations involving structural components, especially when used with a reduced hourglass coefficient of 0.05, which minimizes the introduction of artificial stiffness and preserves the physical fidelity of the simulation.

3.1. Drop Tower Impact Models

The development of the drop tower numerical models stems from the need to validate the simulated impact response against experimental data, ensuring that the model reliably captures the physical behavior of the system. Model validation is essential for establishing the credibility and accuracy of the simulation framework. Once validated, the model serves as a powerful tool to significantly reduce testing costs and time, while enabling the prediction of structural performance under conditions that may be difficult, expensive, or unsafe to replicate experimentally. The validated model will be utilized in

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3 to support the numerical analysis of parametric ground and crash impact scenarios, respectively, providing predictive insights into the mechanical performance and crashworthiness of the battery housing system.

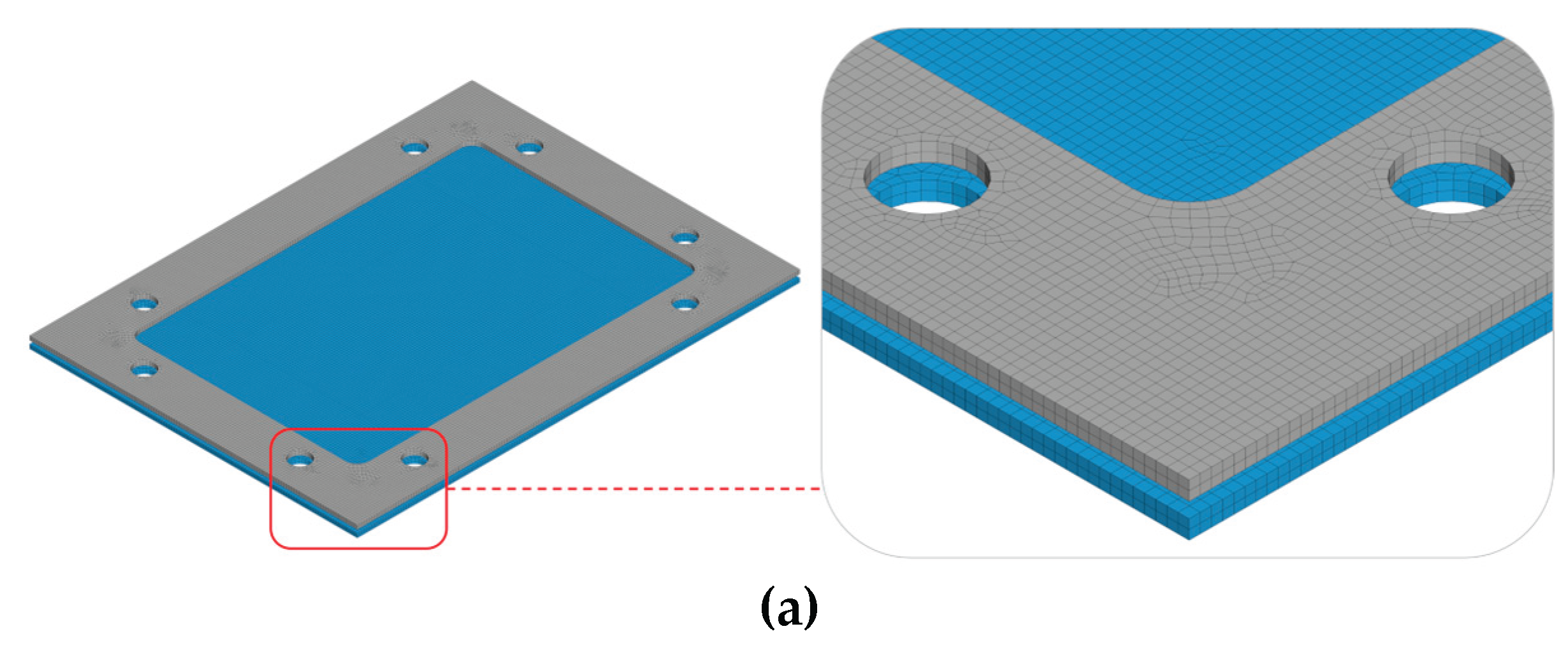

3.1.1. Model of SMC Plate

The first drop tower model simulates the impact event of a projectile striking the SMC composite plates. The setup replicates the configuration of the experimental drop tower apparatus, including the steel support base with a central orthogonal opening, the four clamps, and the steel impactor, as illustrated in

Figure 6. These three components are modeled as rigid bodies using Material Model 20 (MAT_RIGID) in LS-DYNA, with the associated material parameters listed in

Table 3. The MAT_RIGID formulation enables the definition of both translational and rotational constraints for each component. Specifically, the base and clamps are fully constrained in all degrees of freedom, while the impactor is restricted only in the x and y directions and all rotational degrees of freedom, allowing free motion solely in the z-translational direction to simulate the vertical drop impact accurately.

A refined mesh was employed to ensure numerical stability and capture local effects with high accuracy. Specifically, 1 mm solid elements were used for the impactor and the clamps, while a 2 mm element size was applied to the composite plate, as shown in

Figure 7(a),(b),(d). This mesh resolution was selected to minimize the influence of nonlinearities that could introduce numerical instabilities during the simulation. The specimen, representing the SMC composite plate, was modeled using Material Model 162 (MAT_COMPOSITE_MSC_DMG) in LS-DYNA. This material model enables progressive failure analysis of composite materials, incorporating the Hashin failure criteria and a damage mechanics-based softening behavior following damage initiation [

32]. Given the randomly oriented chopped glass fibers in the SMC, the composite exhibits transversely isotropic behavior, with identical in-plane properties and reduced out-of-plane strength—effectively mimicking a unidirectional (UD)-like response. This behavior is implemented in the model using option 1 of the AMODEL keyword, which assumes transverse isotropy. The material properties were derived from experimental mechanical tests presented in

Section 2, and the full list of input parameters is provided in

Table 4. The SMC plate was meshed using 1 mm solid elements, as illustrated in

Figure 7(c).

In impact simulations, automatic contact definitions are preferred due to the continuously changing relative orientations and the large deformations that typically occur during the event. Accordingly, CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE was selected in LS-DYNA to define the interactions between the composite specimen and both the steel base plate and the impactor. According to the literature, static friction coefficients for contact between glass fiber-reinforced polymers (GFRPs) and steel typically range from 0.2 to 0.5, while dynamic friction coefficients are generally 30%–40% lower [

33]. In this study, the static and dynamic friction coefficients for the contact between the GF composite and steel components (impactor and base) were set to 0.4 and 0.2, respectively, to reflect realistic interaction conditions and ensure numerical stability.

To accurately model the interaction between the composite specimen and the clamps, a tied contact approach was implemented. Specifically, CONTACT_TIED_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE_OFFSET was used, which is well-suited for interactions involving rigid bodies, such as the clamps in this setup. In this configuration, the slave nodes (clamps) are constrained to follow the motion of the master surface (specimen), ensuring consistent boundary conditions and preventing relative motion at the interface.

The projectile was assigned an initial impact velocity using the INITIAL_VELOCITY_GENERATION keyword in the z-direction, corresponding to the experimental impact energy levels. For the low-velocity impact simulations, two energy levels were investigated: 7.5 J and 30 J, which correspond to initial velocities of 1486 mm/s and 2972 mm/s, respectively.

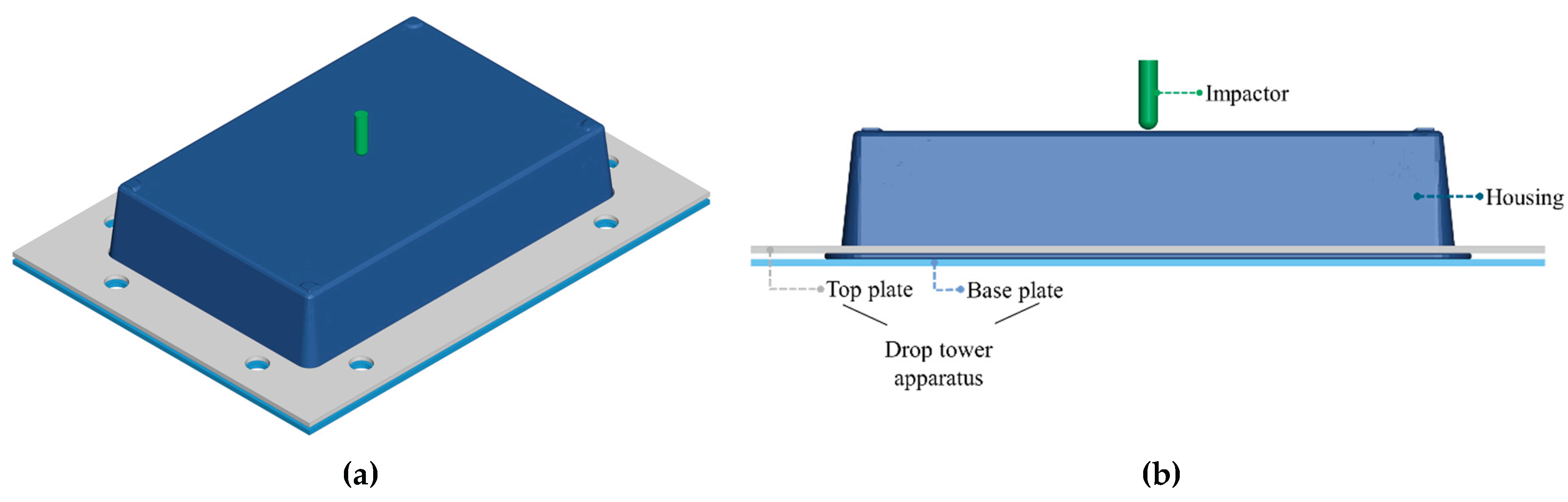

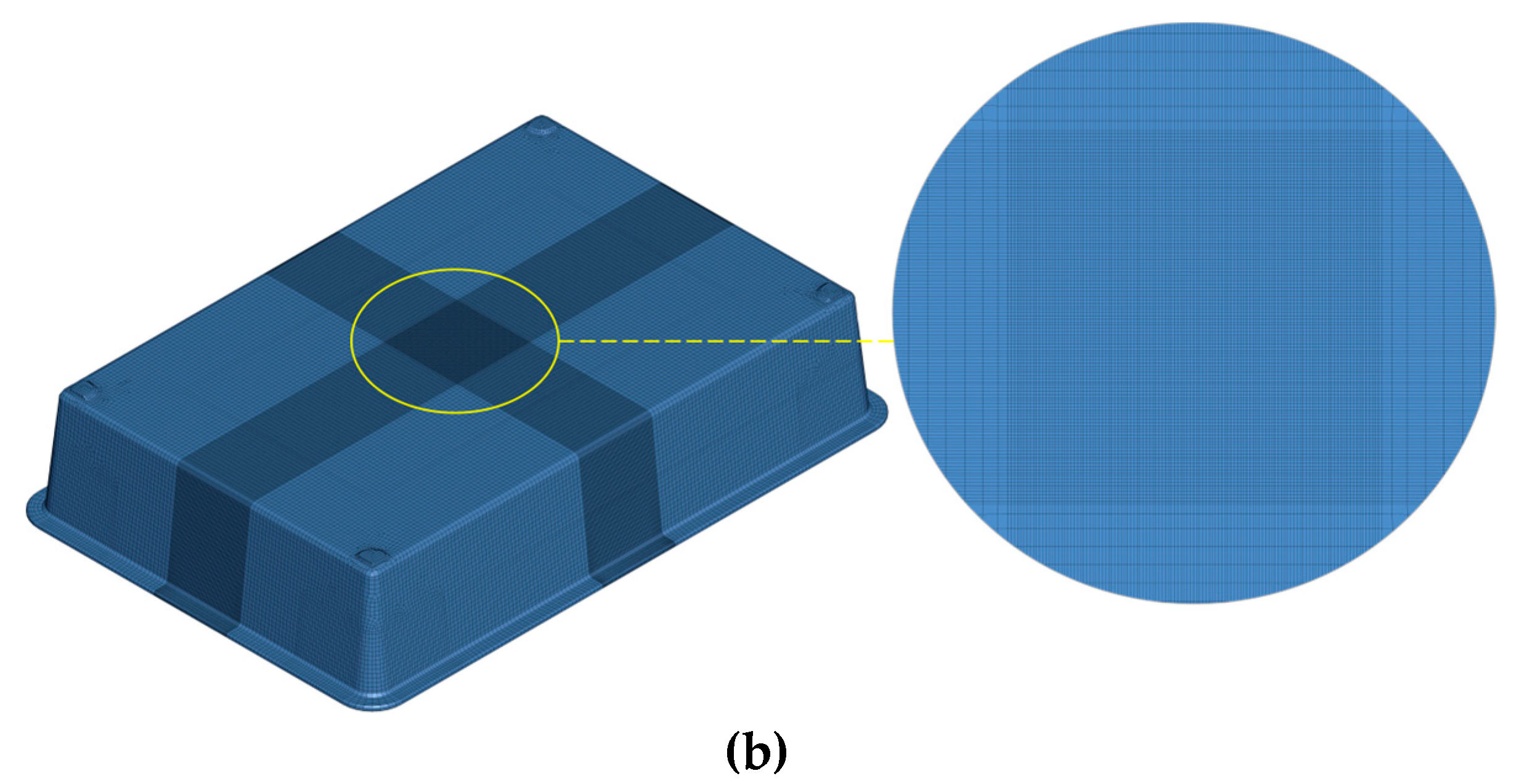

3.1.2. Model of SMC Battery Housing

The second drop tower simulation model replicates the impact event of a projectile striking the SMC composite housing. To constrain the housing’s movement and suppress rebound during the impact event, two steel plates are implemented: one with a rectangular opening matching the dimensions of the housing (positioned on top), and a solid plate (placed underneath). This setup is designed to secure the specimen while allowing localized deformation at the impact site. The projectile is positioned to strike the center of the housing’s upper surface, as shown in

Figure 8. All three components—the projectile and the upper and lower plates—are modeled as rigid bodies using LS-DYNA’s MAT_RIGID material model, with corresponding parameters listed in

Table 3. The steel plates are fully constrained in all degrees of freedom, while the projectile is restricted to translational motion along the z-axis. In terms of meshing, the steel plates are discretized with 3 mm elements, while the projectile is refined with 0.5 mm elements, as illustrated in

Figure 9(a). The housing is modeled using MAT_162, as previously detailed in

Section 3.1.1. To mitigate hourglass effects and improve contact stability, a localized mesh refinement is applied to the impact zone. Specifically, a 60 mm × 60 mm central area is meshed with 0.5 mm elements, while the remainder of the housing is meshed with 2 mm elements to optimize computational efficiency, as shown in

Figure 9(b).

An automatic surface-to-surface contact algorithm was employed to define the interactions between the projectile, steel plates, and the SMC composite housing. This contact type was selected to ensure accurate handling of impact events, sliding, and separation between rigid and deformable bodies. As previously specified, the static and dynamic friction coefficients for the steel–composite interfaces were set to 0.4 and 0.2, respectively, to reflect realistic interaction conditions observed in experimental testing. The projectile was assigned an initial velocity in the z-direction, calibrated to match an impact energy of 30 J. This corresponds to an initial impact velocity of 2972 mm/s, derived from the kinetic energy equation and consistent with experimental conditions.

3.2. Ground Impact Model

Investigating ground impact scenarios in battery housing simulations is critical for ensuring the safety and structural integrity of electric vehicles (EVs) under real-world operating conditions. Battery housings play a key role in protecting lithium-ion battery packs, which are highly sensitive due to their high energy density and potential for hazardous failure modes. In typical driving environments, vehicles are routinely subjected to impacts from road debris, curbs, or other low-lying obstacles—especially at high speeds. A severe impact to the underside of the vehicle can inflict mechanical damage on the battery housing, which may propagate to the battery cells, resulting in internal short circuits, electrolyte leakage, or thermal runaway. These failure modes can lead to fires, explosions, and the release of toxic gases, posing a direct threat to both occupant safety and public health. Even when catastrophic failure is avoided, sub-critical impacts can still induce internal damage to the battery structure, leading to performance degradation, reduced driving range, and shortened battery lifespan. Consequently, numerical simulations are indispensable for evaluating the crashworthiness of battery housings, allowing engineers to predict mechanical response, optimize designs, and implement effective countermeasures to prevent both catastrophic and progressive damage.

The FE model developed to simulate ground impact, as shown in

Figure 10, includes three main components: the composite battery housing, the lid, and a spherical steel impactor with a diameter of 20 mm and mass of 0.3 kg, representing a road debris impact scenario. The enclosure assembly—comprising the housing and lid—is modeled using the short fiber SMC composite material and is assumed to be adhesively bonded. A hexagonal mapped mesh was generated for all components to ensure mesh quality and accuracy. The battery housing and lid were discretized using 2 mm solid elements, while the impactor was meshed with 1 mm elements to capture detailed contact behavior. The projectile is modeled as a rigid body using MAT_RIGID, constrained to move only in the z-direction to replicate vertical impact. The composite components are defined using MAT_162, as described in

Section 3.1.1. To simulate fixed support conditions, the four bottom legs of the battery housing are fully constrained in the z-direction using BOUNDARY_SPC_SET.

An automatic surface-to-surface contact was employed to define the interaction between the impactor and the SMC composite housing, enabling accurate simulation of dynamic contact behavior during impact. Given that the lid and main enclosure are adhesively bonded, a cohesive zone modeling (CZM) approach was adopted to represent the bonded interface. Specifically, the CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE_TIEBREAK option was used, which activates only for nodes initially in contact. In this study, Tiebreak Option 9 was selected, which is based on the cohesive material model MAT_138 (MAT_COHESIVE_MIXED_MODE). This option implements a bilinear traction–separation law and a quadratic mixed-mode delamination criterion, along with a progressive damage formulation to simulate interfacial failure mechanisms [

31,

32]. In CZM, traction stresses develop as bonded nodes begin to separate. Once the predefined maximum traction strength is reached, interfacial failure occurs. This approach effectively captures debonding behavior while maintaining computational efficiency. As demonstrated in the research of Dogan et al. [

34], the tiebreak contact model—with appropriately chosen parameters—has shown strong correlation with experimental results and offers a computationally efficient alternative to full CZM implementation. Accordingly, this method was chosen for the current study to balance accuracy and simulation performance. The tiebreak failure parameters used here are representative of typical structural adhesive films and are summarized in

Table 5.

Four cases of impact are examined, with a parametric increase of velocity between 10 and 25 m/s, as described in

Table 6, which corresponds to a wide range of realistic speeds, 36 to 90 km/h, a vehicle can travel with.

3.2.1. Models of Cells and Cell Pack

The primary objective of battery housing design is to ensure the protection of individual cells, which significantly influences the overall stiffness, mass, and energy absorption capacity of the battery pack. During an impact event, the housing serves as the first line of defense, transmitting forces directly to the cell pack. Therefore, accurately modeling the cell pack is essential to realistically predict load distribution, deformation behavior, and energy dissipation throughout the system. This level of fidelity is critical for achieving compliance with safety standards and regulations. Omitting the cell pack from the simulation would likely result in an overestimation of the housing’s protective capabilities, leading to a misleading evaluation of the battery system’s crashworthiness. As such, the inclusion of the cell pack in the numerical model is vital for assessing the structural integrity of the entire assembly and for ensuring the reliable protection of its most critical components under impact conditions.

In this study, a thermoplastic cell pack is placed inside the composite housing, with outer dimensions of 230 mm × 288 mm × 81 mm, as illustrated in

Figure 11(a). The pack encapsulates five solid-state pouch cells, each measuring 280 mm in length and 195 mm in width, utilizing aluminum–plastic enclosures and Li/Advanced LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate) battery chemistry. As the focus of this study lies in evaluating the mechanical response rather than the electrochemical behavior, the pouch cells are simplified for modeling purposes. Each cell is represented by a 0.1 mm thick aluminum foil shell, which simulates the outer casing, and an 8 mm thick polymer gel core, serving as a surrogate for the internal active components—including the anode, cathode, and electrolyte. To limit uncontrolled motion of the cells during impact scenarios, plastic cell frames are introduced between each pouch cell. These frames have an orthogonal geometry of 270 mm × 210 mm, with a 4 mm thickness, and feature a central 236 mm × 175 mm opening to permit controlled deformation of the cells in the middle of the configuration, as shown in

Figure 11(b),(c). For the finite element model, a mapped mesh was applied across all components to ensure mesh regularity and accuracy. The cell pack structure is discretized using 3 mm solid elements, while both the pouch cells and intermediate frames are meshed with a finer 2 mm element size, as depicted in

Figure 12.

Both the cell pack and the intermediate frames are composed of ABS plastic, a material commonly used for structural and protective components in battery systems. In the finite element model, ABS is represented using the MAT_24 (MAT_ISOTROPIC_ELASTIC_PLASTIC) material model in LS-DYNA, which accounts for isotropic plasticity without built-in failure or erosion capabilities. This model is selected for its computational efficiency and ability to capture basic plastic deformation behavior under impact loading. To enable failure within this framework, the ADD_EROSION option is activated. This enhancement allows for element deletion when a predefined failure criterion is met. In this study, the Von Mises stress criterion is employed, and failure is initiated when the equivalent stress reaches a specified threshold, as detailed in

Table 7. For the cell components, an isotropic elastic material, with the specialization of allowing the modeling of fluids (MAT_ELASTIC), is employed. The input parameters for the aluminum foil and the polymer gel are stated in

Table 8.

To accurately capture the mechanical interactions within the battery system, automatic surface-to-surface contact is defined between the cell pack and both the upper and lower support frames, as well as between the frames and individual pouch cells. This contact setup allows for realistic relative motion and stress transfer between components during impact loading. The internal cell structure, comprising the aluminum foil shell and the polymer gel core, is modeled using CONTACT_TIED_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE. In this constraint-based formulation, the slave nodes (assigned to the foil shell) remain fully attached to the master surface (the gel core), ensuring kinematic compatibility and preventing artificial separation or delamination during deformation. Additionally, the entire cell pack is assumed to be adhesively bonded to the composite housing via a tiebreak contact formulation. This is implemented using CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE_TIEBREAK, allowing for the simulation of interface failure between the cell pack and the housing. The relevant interfacial strength and failure criteria are described in

Section 3.2, enabling the model to realistically predict debonding or delamination under severe loading conditions.

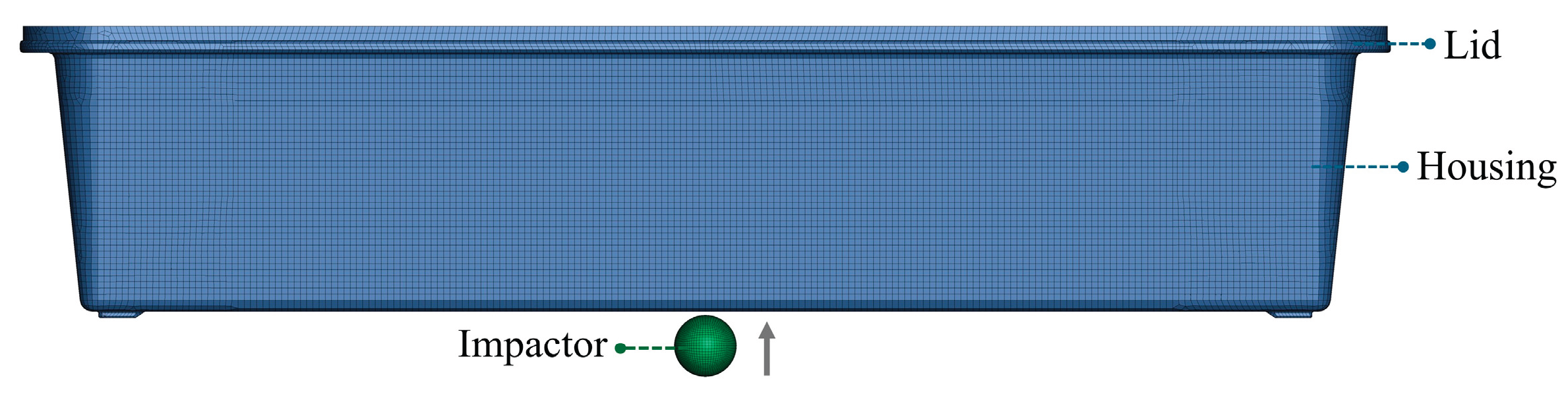

3.3. Crash (Pole) Model

Crash simulations, especially those involving pole impacts, represent some of the most demanding and safety-critical load cases for battery enclosures. These scenarios are vital for evaluating the enclosure’s ability to withstand localized, high-energy impacts—conditions commonly encountered in real-world vehicle collisions. Such analyses are crucial for assessing the enclosure’s performance in terms of impact energy absorption, structural integrity preservation, and protection of the internal cell pack, while also considering material efficiency and weight optimization. In this study, a parametric analysis is performed to examine the impact response of the SMC composite battery housing across a range of impact energy levels. The simulations involve a cylindrical pole impactor striking the enclosure at various initial velocities, carefully selected to replicate realistic crash conditions observed in full-scale vehicle tests. These velocities, detailed in

Table 9, correspond to practical, high-risk scenarios and offer valuable insights into the crashworthiness and structural resilience of the composite housing design.

The crash simulation model consists of the main enclosure (housing) and lid, which are adhesively bonded, a rigid cylindrical impactor, and a base plate that simulates the vehicle floor, as depicted in

Figure 13. The housing is made from SMC composite material, while both the impactor and base plate are modeled with steel properties. The impactor is modeled as a rigid body, measuring 120 mm in length, 50 mm in diameter, and weighing 7 kg. It is constrained to move exclusively in the x-direction, replicating a lateral impact scenario. The base plate, with dimensions of 440 mm × 300 mm, is also defined as a rigid body, with all translational and rotational degrees of freedom fully constrained. All components are meshed with solid elements using a uniform element size of 2 mm, ensuring sufficient resolution for capturing local deformations. Contact between the impactor and the housing/lid assembly is defined using CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE, allowing accurate simulation of force transmission during the impact event. To represent the adhesive bonding between the lid and housing, a tiebreak contact formulation is used, enabling simulation of potential debonding or failure under high loads. Additionally, the bottom surface of the housing is bonded to the base plate using adhesive film properties consistent with those defined in

Table 5, ensuring realistic interface behavior during impact loading.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact performance of an innovative SMC-based thermoplastic battery housing under both ground and frontal pole impact scenarios. The mechanical behavior of the composite material was experimentally characterized through tensile, compressive, shear, and three-point bending tests. Drop tower impact experiments were conducted on flat SMC plates and the housing itself at 7.5 J and 30 J, providing the foundation for validating the corresponding finite element models.

Numerical simulations, developed using the LS-DYNA material model MAT_162, demonstrated strong correlation with experimental results, accurately predicting peak impact forces, global stiffness, and energy absorption. While the simulations offered smoother representations of localized failure phenomena—such as matrix cracking and fiber fracture—they still reliably captured key metrics including displacement, indentation depth, and overall damage extent.

Parametric analyses of ground impacts revealed a progressive failure mechanism: at low velocities, both the housing and cell pack provided effective isolation and protection for the battery cells. However, as velocity increased, the cell pack experienced greater displacement, leading to localized deformation in the first, and subsequently the second, cell layer—highlighting a critical velocity threshold beyond which internal damage becomes probable.

In frontal pole impact simulations, increasing impact energy resulted in pronounced deformation of the housing and lid. Although the enclosure initially dissipated energy effectively, its protective function diminished at higher energy levels, allowing mechanical intrusion into the cell pack. This observed degradation in performance under high-severity conditions provides valuable insights into the structural limits of the system.

From a safety standpoint, the structural integrity of the housing is correlated to battery safety, since deformation of the pouch cells may cause separator penetration and lead to internal short-circuit that can potentially trigger thermal runaway. The parametric studies indicate that up to 15 m/s ground impact and 10 m/s pole impact, the Elium SMC housing successfully prevents contact between the impactor and the cell pack, ensuring that the cells remain mechanically isolated, maintaining their electrochemical safety. However, beyond these thresholds, the first pouch cells in the stack begin to deform. While the deformation observed in this study is not sufficient to cause immediate rupture, it highlights a critical transition point for defining safe operating conditions for battery housing design.

In summary, the thermoplastic battery housing demonstrates robust impact resistance within defined energy thresholds. The validated numerical models offer a reliable framework for structural evaluation and future design optimization. Enhancing the predictive fidelity of these models, particularly regarding composite failure mechanisms and thermal effects, will support the development of safer and more resilient battery systems for transport applications.

Figure 1.

Geometry and dimensions (in mm) of the housing (a) x-y plane, (b) y-z plane.

Figure 1.

Geometry and dimensions (in mm) of the housing (a) x-y plane, (b) y-z plane.

Figure 2.

Testing configuration and mounted specimens of (a) tension test, (b) compression test, (c) shear test, and (d) three-point bending test.

Figure 2.

Testing configuration and mounted specimens of (a) tension test, (b) compression test, (c) shear test, and (d) three-point bending test.

Figure 3.

Force - displacement curves of the SMC specimens subjected to (a) tension, (b) compression, (c) shear, d) three-point bending.

Figure 3.

Force - displacement curves of the SMC specimens subjected to (a) tension, (b) compression, (c) shear, d) three-point bending.

Figure 4.

Failure modes of the SMC specimens subjected to (a) tension, (b) compression, (c) shear, d) three-point bending.

Figure 4.

Failure modes of the SMC specimens subjected to (a) tension, (b) compression, (c) shear, d) three-point bending.

Figure 5.

Instron drop tower testing setup.

Figure 5.

Instron drop tower testing setup.

Figure 6.

Configuration of the drop tower model for the plate.

Figure 6.

Configuration of the drop tower model for the plate.

Figure 7.

FE mesh of the drop tower model components for the plate: (a) clump, (b) impactor, (c) plate, and (d) base.

Figure 7.

FE mesh of the drop tower model components for the plate: (a) clump, (b) impactor, (c) plate, and (d) base.

Figure 8.

Configuration of the drop tower model for the housing: (a) isometric view and (b) side view.

Figure 8.

Configuration of the drop tower model for the housing: (a) isometric view and (b) side view.

Figure 9.

FE mesh of (a) the apparatus of the drop tower model for the housing, and b) the housing.

Figure 9.

FE mesh of (a) the apparatus of the drop tower model for the housing, and b) the housing.

Figure 10.

FE mesh of the housing and the impactor of the ground impact model.

Figure 10.

FE mesh of the housing and the impactor of the ground impact model.

Figure 11.

Geometry of (a) the cell pack, (b) the cell frames, and (c) the cells.

Figure 11.

Geometry of (a) the cell pack, (b) the cell frames, and (c) the cells.

Figure 12.

FE mesh of (a) the cell frame, (b) the cell pack, and (c) the cell.

Figure 12.

FE mesh of (a) the cell frame, (b) the cell pack, and (c) the cell.

Figure 13.

FE mesh of the housing and the impactor of the pole impact/ crash model.

Figure 13.

FE mesh of the housing and the impactor of the pole impact/ crash model.

Figure 14.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 7.5J impact of the drop tower impact on the plate.

Figure 14.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 7.5J impact of the drop tower impact on the plate.

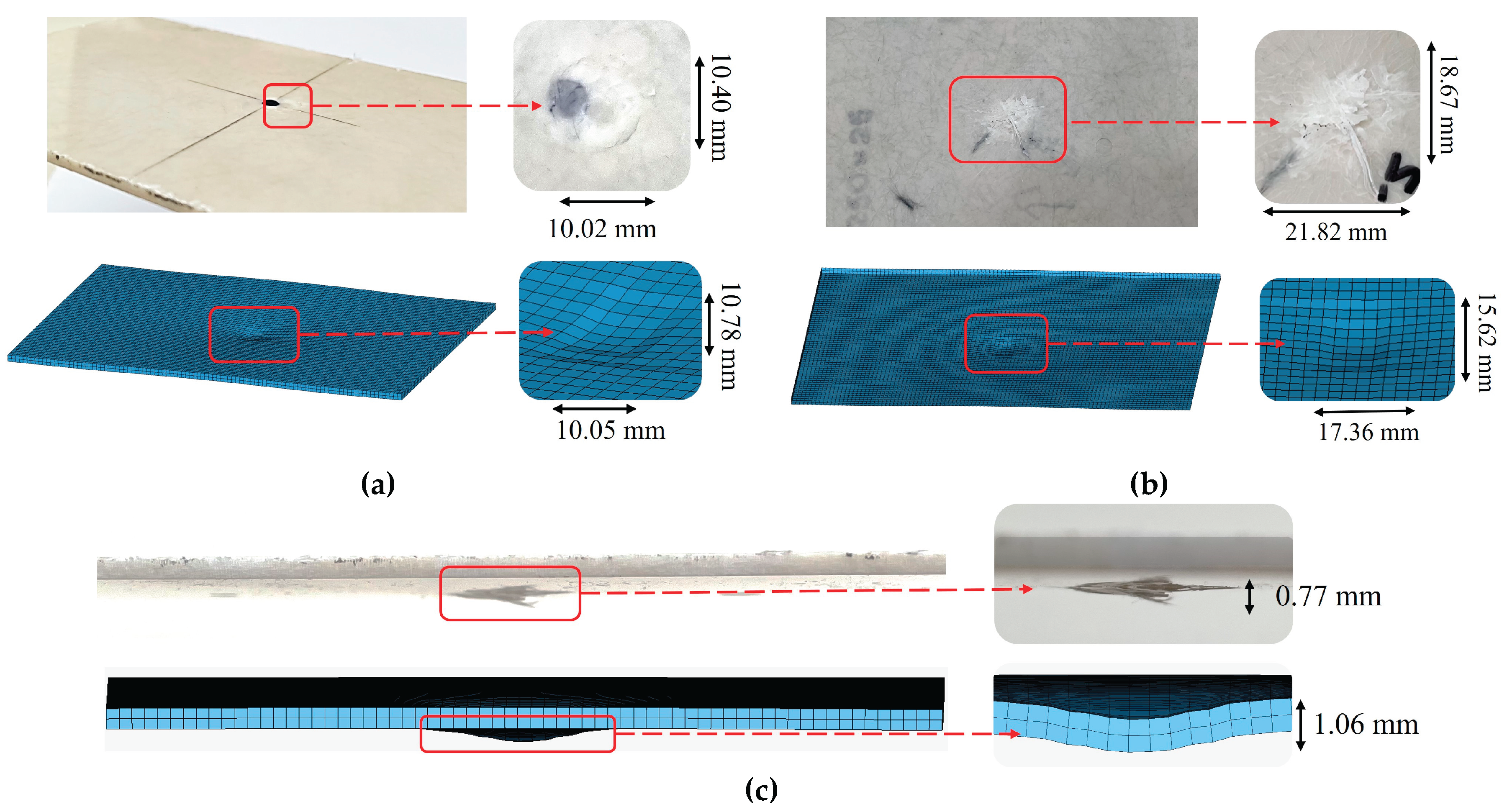

Figure 15.

Experimental versus numerical results of the SMC plate subjected to 7.5 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

Figure 15.

Experimental versus numerical results of the SMC plate subjected to 7.5 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

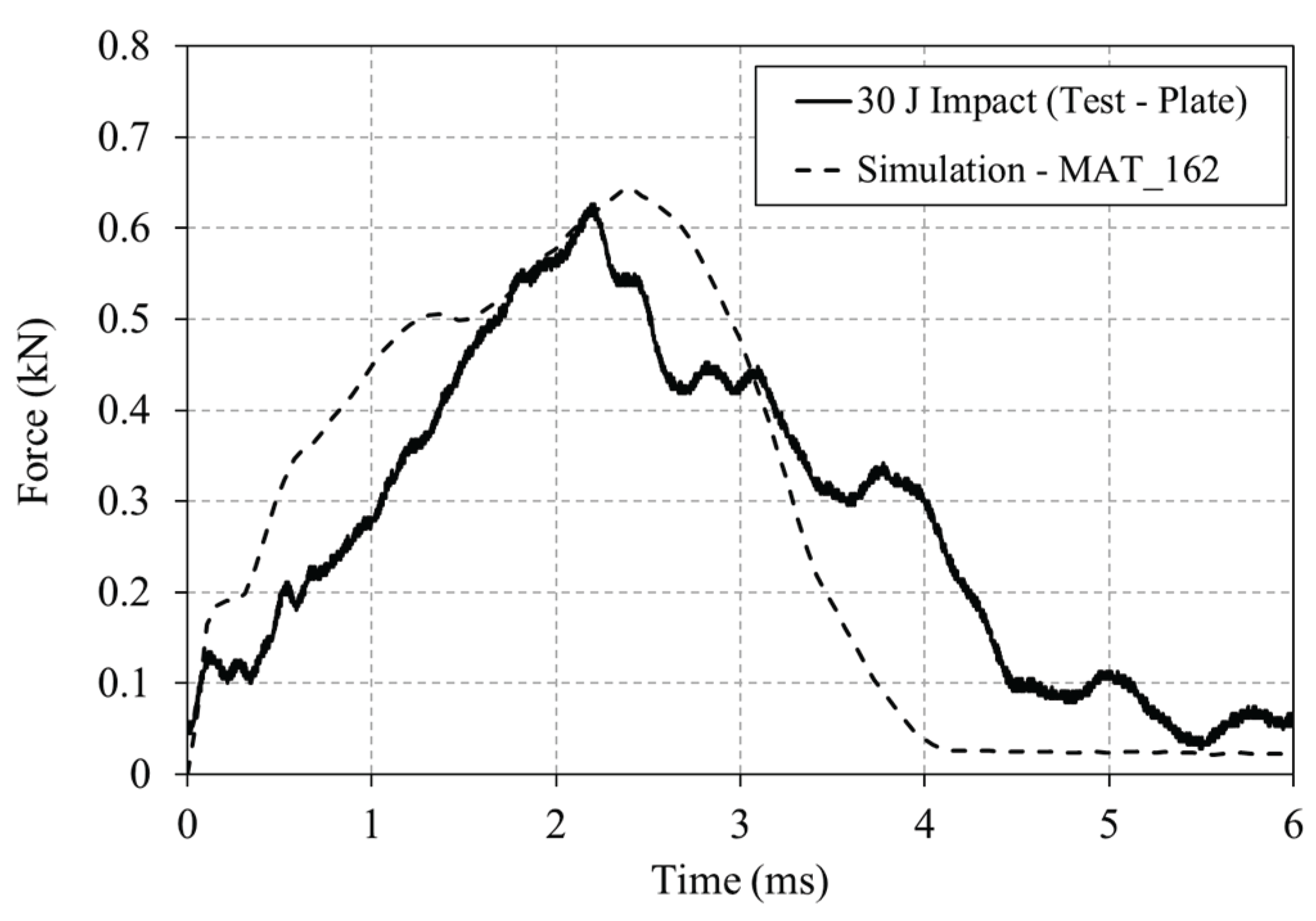

Figure 16.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 30 J impact of the drop tower impact on the plate.

Figure 16.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 30 J impact of the drop tower impact on the plate.

Figure 17.

Experimental versus numerical results of the SMC plate subjected to 30 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

Figure 17.

Experimental versus numerical results of the SMC plate subjected to 30 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

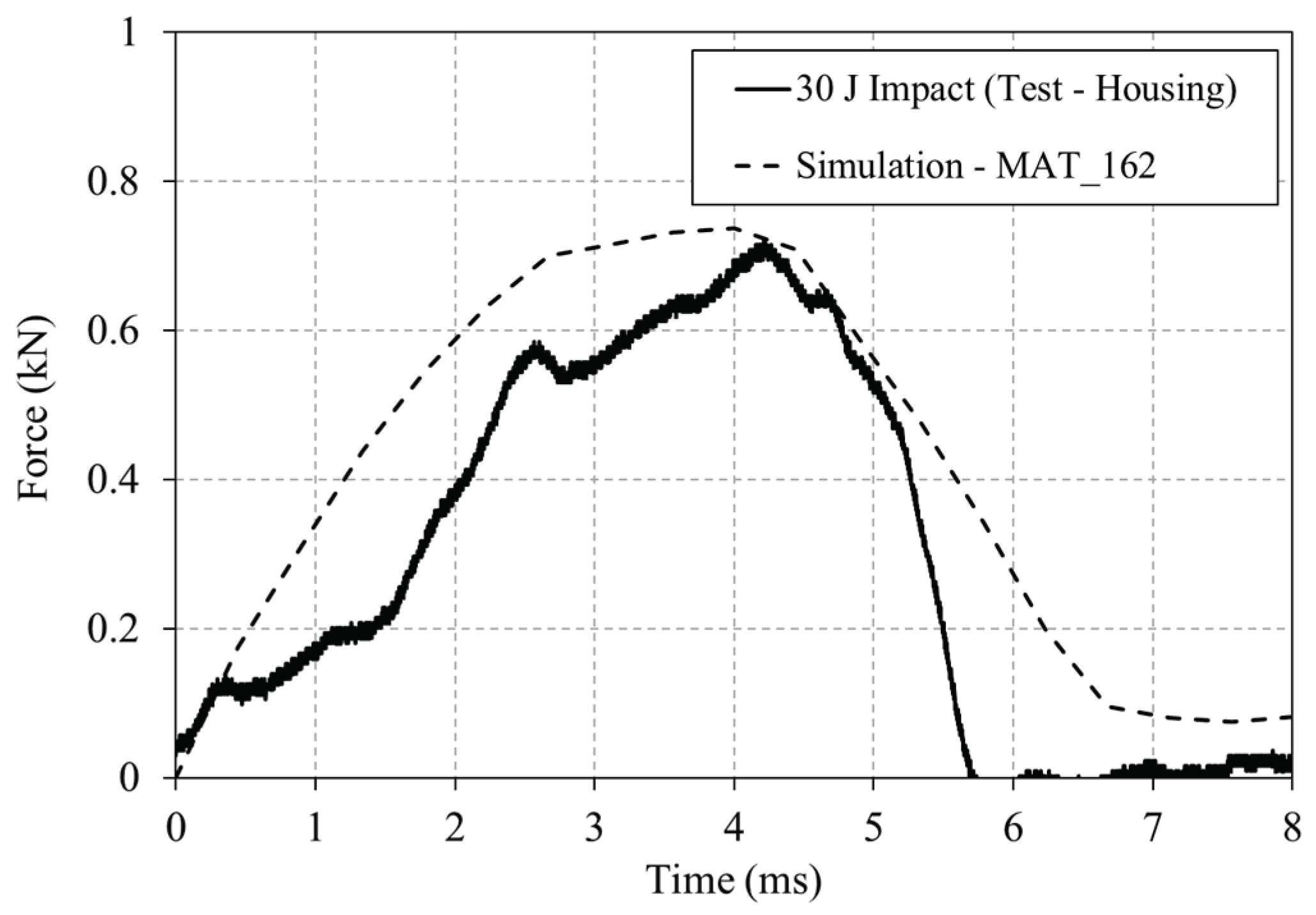

Figure 18.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 7.5J impact of the drop tower impact on the housing.

Figure 18.

Experimental and numerical force-time curves for the 7.5J impact of the drop tower impact on the housing.

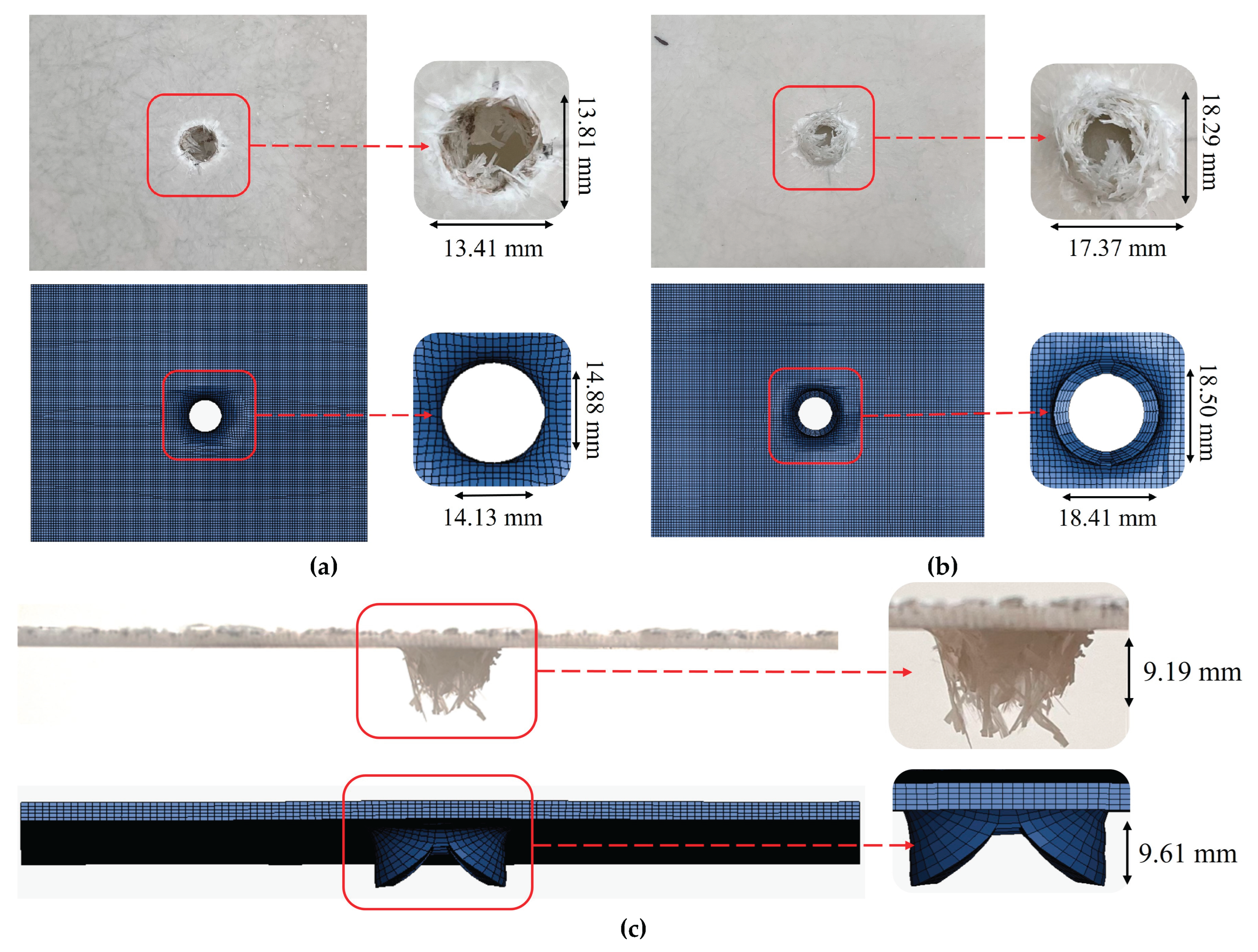

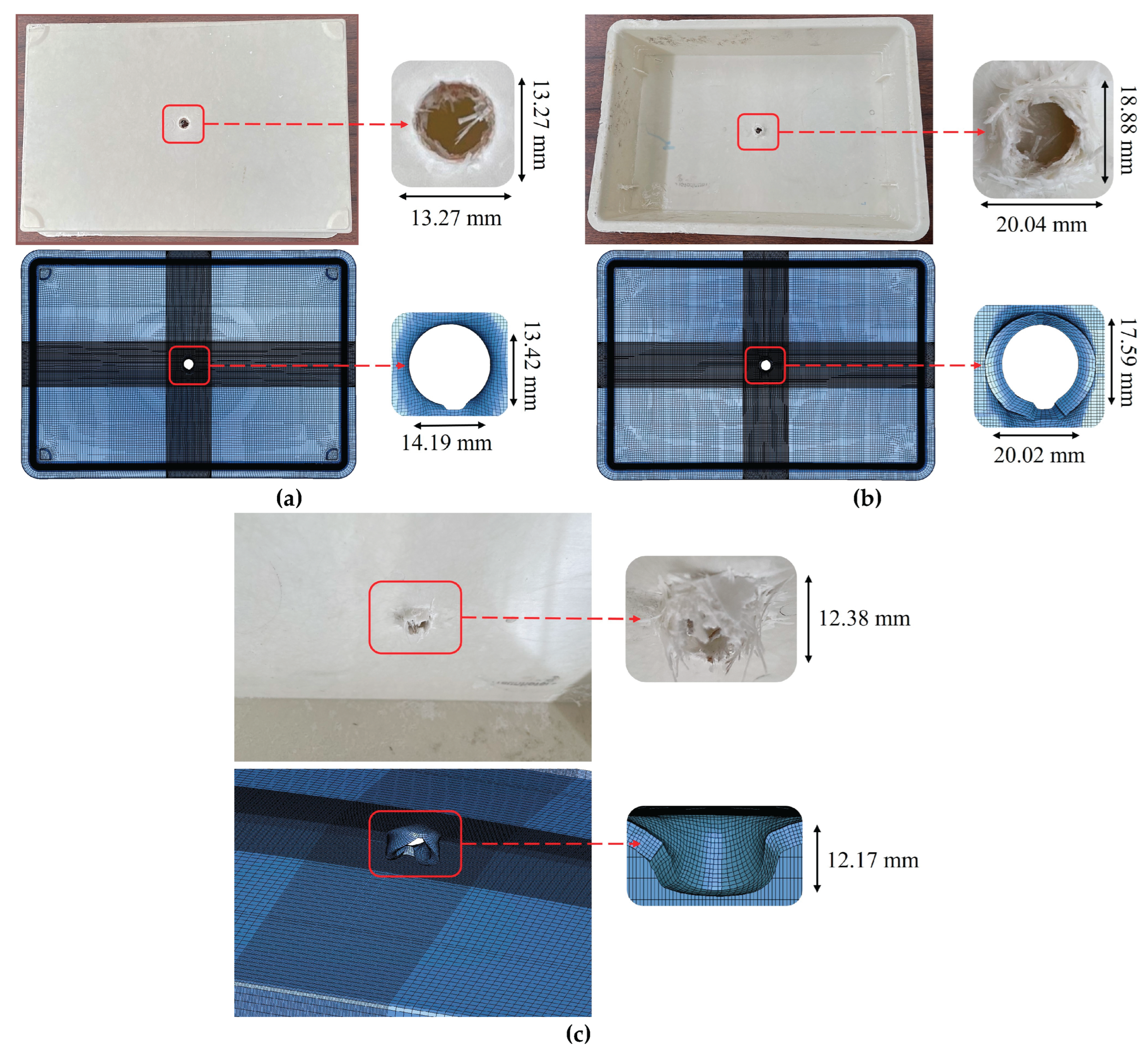

Figure 19.

Experimental versus numerical results of SMC housing subjected to 30 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

Figure 19.

Experimental versus numerical results of SMC housing subjected to 30 J impact. a) Front face, b) back face, c) side profile comparison.

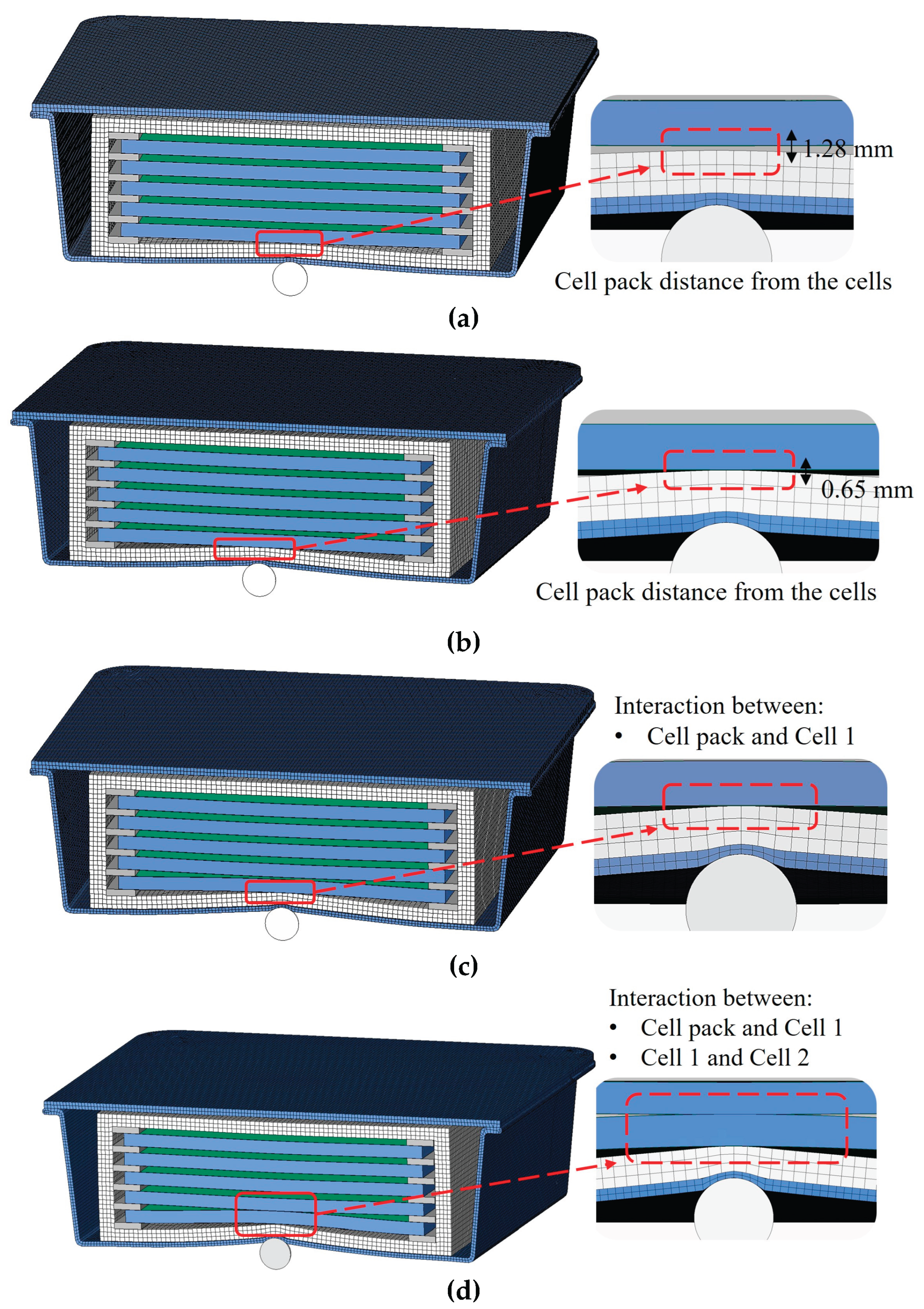

Figure 20.

Interaction of the housing and the cells/cell pack at the maximum displacement of the impactor for the impact cases of (a) 10 m/s, (b) 15 m/s, (c) 20 m/s, and (d) 25 m/s.

Figure 20.

Interaction of the housing and the cells/cell pack at the maximum displacement of the impactor for the impact cases of (a) 10 m/s, (b) 15 m/s, (c) 20 m/s, and (d) 25 m/s.

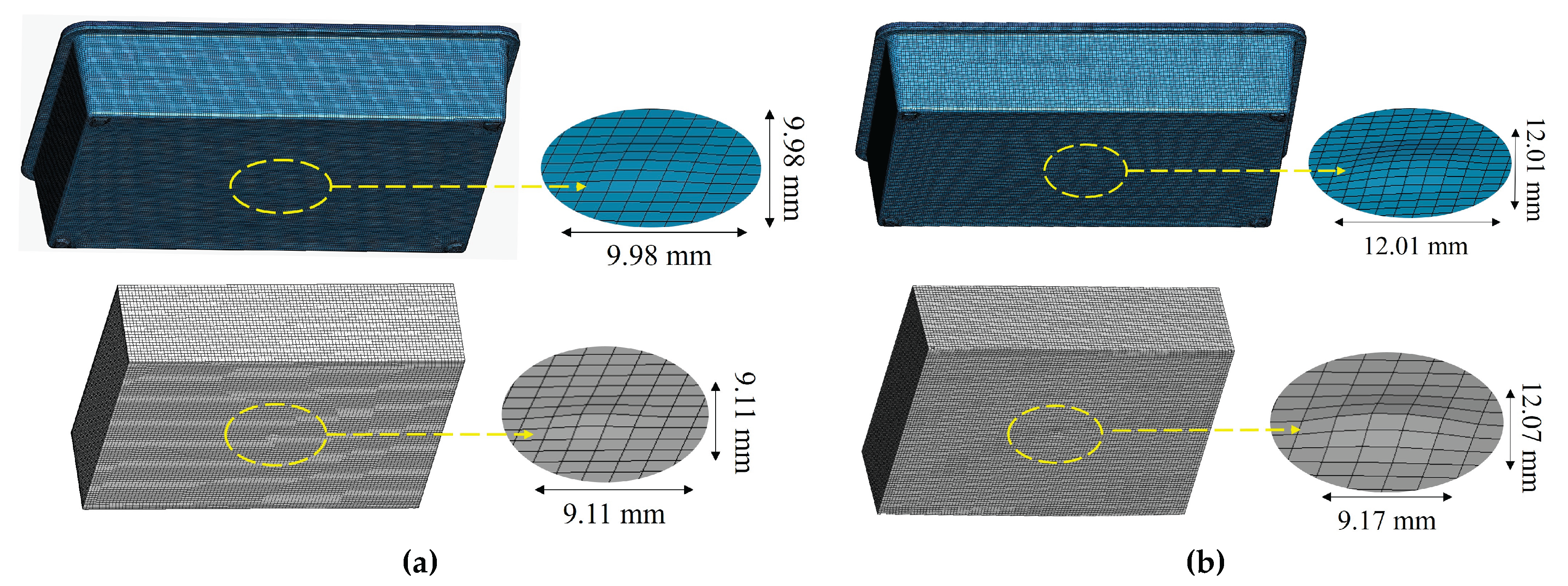

Figure 21.

Permanent deformation in the x and y directions for the housing and the cell pack after being subjected to ground impact of (a) 15 m/s, (b) 20 m/s, (c) 25 m/s.

Figure 21.

Permanent deformation in the x and y directions for the housing and the cell pack after being subjected to ground impact of (a) 15 m/s, (b) 20 m/s, (c) 25 m/s.

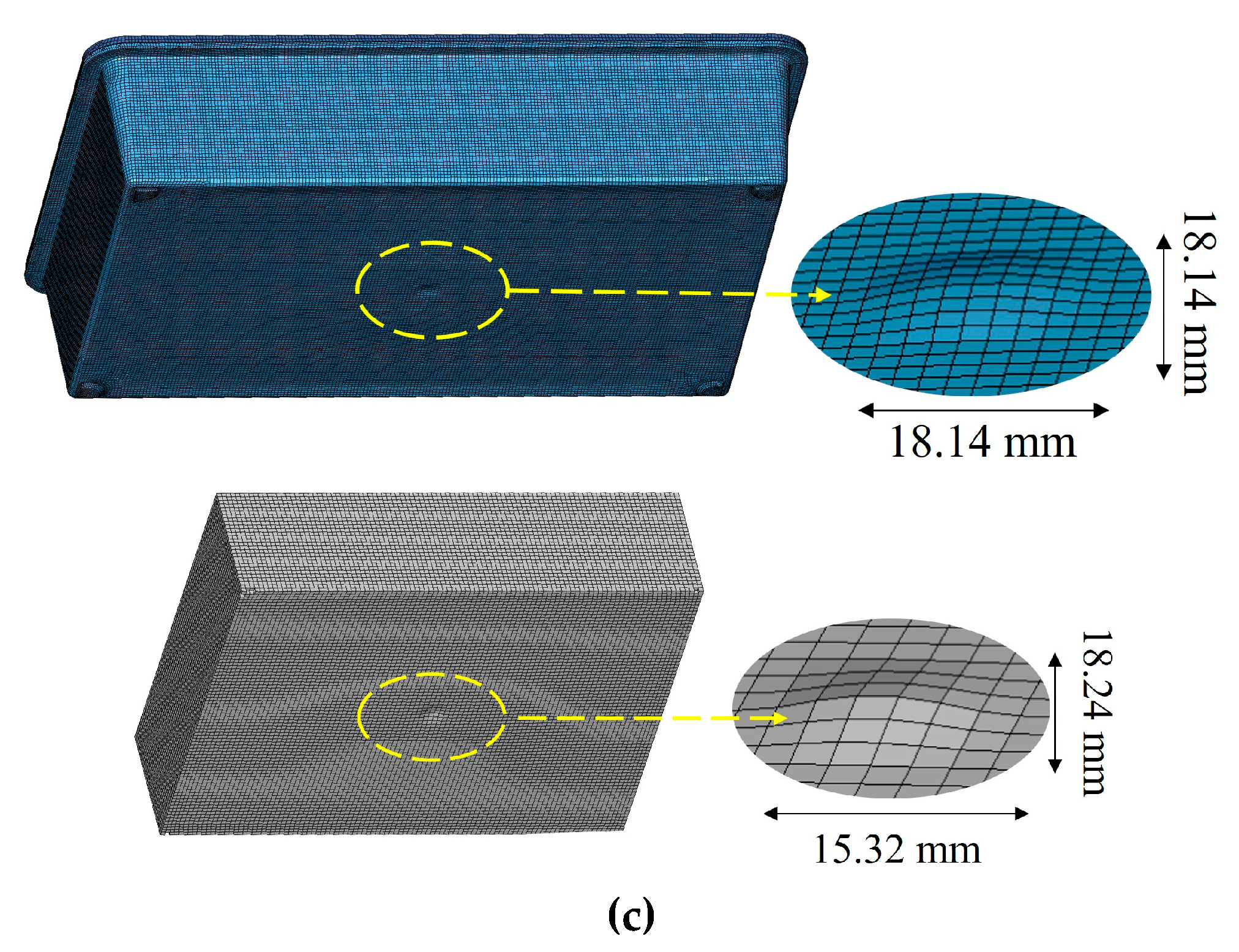

Figure 22.

Maximum displacement of the housing and cell pack after the event of (a) 10 m/s, (b) 12.5 m/s and (c) 15 m/s pole impact.

Figure 22.

Maximum displacement of the housing and cell pack after the event of (a) 10 m/s, (b) 12.5 m/s and (c) 15 m/s pole impact.

Figure 23.

Interaction of the housing and the cell pack / lid at the maximum displacement of the impactor after the event of the 15 m/s pole impact: (a) left view (intersection), (b) right view.

Figure 23.

Interaction of the housing and the cell pack / lid at the maximum displacement of the impactor after the event of the 15 m/s pole impact: (a) left view (intersection), (b) right view.

Table 1.

Mechanical testing parameters.

Table 1.

Mechanical testing parameters.

| Test |

Standard |

Specimen dimensions |

Speed of testing |

| Tension |

ASTM D3039 |

250 × 25 × 2.5 mm3

|

1 mm/min |

| Compression |

ASTM D3410 |

140 × 25 × 2.5 mm3

|

1 mm/min |

| Three-point bending |

ASTM D790 |

95 × 18 × 4.5 mm3

|

2.2 mm/min |

| Shear |

ASTM D7078 |

76 × 56 × 4.5 mm3

|

2 mm/min |

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the SMC composite derived from standardized testing.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the SMC composite derived from standardized testing.

| Property |

Value |

| Modulus of Elasticity |

12.26 GPa |

| Tensile strength |

94.99 MPa |

| Poisson’s ratio |

0.15 (-) |

| Compressive modulus |

13.61 GPa |

| Compressive strength |

133.83 MPa |

| Flexural modulus |

12.91 GPa |

| Flexural strength |

190.31 MPa |

| Shear modulus |

5.8 GPa |

| Shear strength |

76.92 MPa |

Table 3.

Steel input parameters for MAT_20.

Table 3.

Steel input parameters for MAT_20.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Density, RO |

7580 kg/m3

|

| Young’s modulus, E |

200 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio, PR |

0.33 (-) |

Table 4.

SMC input parameters for MAT_162.

Table 4.

SMC input parameters for MAT_162.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Density, RO |

1878 kg/m3 |

| Young’s modulus - longitudinal direction, Ea |

12.2 GPa |

| Young’s modulus - transverse direction, Eb |

12.2 GPa |

| Young’s modulus - through thickness direction, Ec |

5 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio, vba |

0.15 (-) |

| Poisson’s ratio, vca, vcb |

0.18 (-) |

| Shear modulus, Gab |

5.8 GPa |

| Shear modulus, Gbc, Gca |

3.5 GPa |

| Longitudinal tensile strength, SaT |

95 MPa |

| Transverse tensile strength, SbT |

95 MPa |

| Through thickness tensile strength, ScT |

75 MPa |

| Longitudinal compressive strength, SaC |

133 MPa |

| Transverse compressive strength, SbC |

133 MPa |

| Matrix mode shear strength, Sab, Sbc, Sca |

76 MPa |

Table 5.

Delamination damage model input data for Tiebreak contact.

Table 5.

Delamination damage model input data for Tiebreak contact.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Normal failure stress (peak traction), NFLS |

40 MPa |

| Shear failure stress (peak traction), SFLS |

60 MPa |

| Exponent of the mixed mode criterion (Power law), PARAM |

2 |

| Normal energy release rate, ERATEN |

1.7 MPa·mm |

| Shear energy release rate, ERATES |

0.789 MPa·mm |

| Tangential stiffness to normal stiffness, CT2CN |

1 |

| Normal stiffness, CN |

106 MPa/mm |

Table 6.

Ground impact parameters.

Table 6.

Ground impact parameters.

| |

Impactor’s initial velocity |

Total energy |

| i. |

10 m/s |

15 J |

| ii. |

15 m/s |

33.75 J |

| iii. |

20 m/s |

60 J |

| iv. |

25 m/s |

93.75 J |

Table 7.

Material input data for ABS properties.

Table 7.

Material input data for ABS properties.

| Parameter |

Value |

| |

MAT_12 |

| Density, RO |

1040 kg/m3

|

| Shear modulus, G |

0.85 GPa |

| Yield stress, SIGY |

41.5 MPa |

| Bulk modulus, BULK |

3.94 GPa |

| |

MAT_ADD_EROSION |

| Equivalent stress at failure, SIGVM |

55 MPa |

Table 8.

Material parameters of the cell components implemented in MAT_01.

Table 8.

Material parameters of the cell components implemented in MAT_01.

| Parameter |

Value |

| |

Aluminum foil |

Polymer gel |

| Density, RO |

2700 kg/m3

|

900 kg/m3

|

| Young’s modulus, E |

69 GPa |

1.5 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio, PR |

0.33 (-) |

0.45 (-) |

Table 9.

Pole impact model parameters.

Table 9.

Pole impact model parameters.

| |

Impactor’s initial velocity |

Total energy |

| i. |

10 m/s |

350 J |

| ii. |

12.5 m/s |

547 J |

| iii. |

15 m/s |

787 J |

Table 10.

Permanent deformation of the housing and the cell pack in the z direction after ground impact of 10, 15, 20, 25 m/s.

Table 10.

Permanent deformation of the housing and the cell pack in the z direction after ground impact of 10, 15, 20, 25 m/s.

| Impact velocity |

Permanent deformation |

| |

|

Housing |

Cell pack |

| i. |

10 m/s |

0.07 mm |

0.01 mm |

| ii. |

15 m/s |

0.57 mm |

0.72 mm |

| iii. |

20 m/s |

1.01 mm |

1.25 mm |

| iv. |

25 m/s |

1.07 mm |

1.32 mm |