1. Introduction

The delamination of building facades is a common disease in construction. Insufficient adhesive performance of the adhesive mortar connecting the structural and decorative layers is one of the main causes of shedding. Most of the existing adhesive mortars are made of organic glue mixed with cement mortar, which has the problems of high carbon emission, easy aging, and insufficient water resistance and corrosion resistance. Therefore, it is important to develop inorganic adhesive mortar with low carbon, high adhesion and high durability.

Geopolymer (GP), as a new type of material Geopolymer, as an inorganic material with properties comparable to organic materials [

1], has the advantages of recyclable, high adhesive strength, good resistance to acid and alkali corrosion, and high temperature resistance [

2]. Existing studies have found that the GP matrix has few high-calcium minerals such as tricalcium silicate, which undergoes alkali excitation and polycondensation reactions, and ultimately generates a large number of C-(A)-S-H and N-(A)-S-H substances with spatial reticulation structures [

3]. These substances are more likely to establish a dense transition zone structure with aggregates or old substrates compared to the large amount of calcium hydroxide (CH) first generated by cement hydration [

4].The alkali exciters contained in GP mortar can also react with the Al and Si reactive components in the interfaces of old mortars to further enhance the adhesive properties of the inter-facial transition zones [

5,

6]. Therefore, it is feasible to utilize solid waste through alkali excitation technology to develop environmentally friendly adhesive mortar with high adhesive durability to solve the problem of the delamination of building facades.

Cellulose ether (CE) and dispersible latex powder (VAE) are indispensable additives in existing adhesive mortars. CE is a class of polymeric compounds with an ether structure. Existing studies have shown that CE can be adsorbed on the surface of cement particles, significantly improving the water retention properties of cement-based materials [

7,

8], effectively improving the adhesive and anti-cracking properties of cement mortar [

9]. The inhibitory effect of CE on the generation of C-S-H gel through molecular adsorption is significantly stronger than the effect on the dissolution process of C

3S minerals, and the ether bonds in the molecular chain form a coordination bond with Ca

2+ on the surface of C-S-H, not only altering the hydration process, but also changing the hydration process and the water retention properties. The ether bond in the molecular chain forms a coordination bond with Ca

2+ on the C-S-H surface, which not only changes the morphology of the hydration product, but also inhibits the ion migration rate through the spatial site-barrier effect, leading to the delay of the hydration exothermic peak [

10,

11]. However, the addition of CE increases the porosity, especially the number of macropores, and changes the shape and distribution of pores, resulting in a significant decrease in compressive strength than flexural strength. A comprehensive comparison of different types of CE revealed that Hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC) showed better effect on mortar’s adhesive [

12]. When CE molecules contain methyl groups, their surface activity is higher, but their incorporation leads to a reduction in mortar strength [

8].

VAE is a kind of polymer particles with ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer as the core component with “shell and core” structure [

13], which has excellent film-forming and adhesive properties. The polymer film generated by VAE can effectively fill and seal the pores, enhance the impermeability, and reduce the drying shrinkage [

14,

15]. The appropriate amount of VAE can significantly improve the adhesive strength, shear strength and tensile strength of mortar [

13,

16]. However, the addition of VAE will bring in a certain amount of air bubbles. The uneven distribution of these bubbles leads to the instability of the internal pore structure of mortar, the decrease of compressive strength [

17,

18] and the decrease of durability [

19].

In summary, HPMC and VAE showed good effect on improving the adhesive performance of cement-based mortar. But their influence law and adhesive effect mechanism on GP mortar are not clear. In order to further improve the adhesive durability of GP mortar, it is necessary to establish the adhesive modification mechanism of HPMC and VAE on GP mortar. Based on this, this paper systematically investigates the modification mechanisms of HPMC and VAE on the working, mechanical, and durability properties of GP mortar. It is of great significance to promote the high value-added utilization of solid waste, improve the durability and reduce the cost and carbon emission of adhesive mortar.

2. Materials and experiments

2.1. Materials

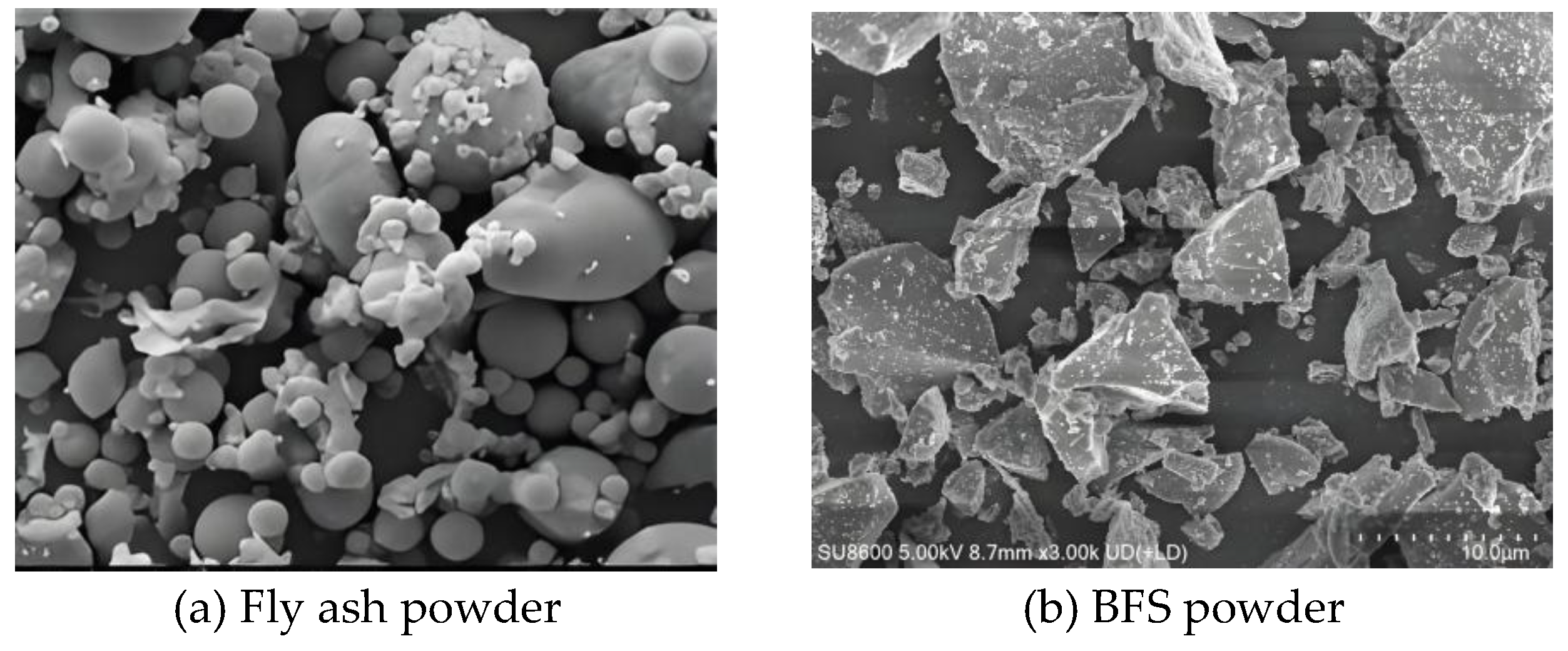

Grade-II Class F fly ash (FA) was supplied by Hebei Kexu Building Materials Co., Ltd. Granulated blast-furnace slag (GBFS) was sourced from Jinghang Mineral Products Co., Ltd., Lingshou County, Shijiazhuang, and classified as high-quality, highly reactive slag, according to GB/T 203-2008. Micrographs and chemical compositions of two binders are provided in

Figure 1 and

Table 1, respectively.

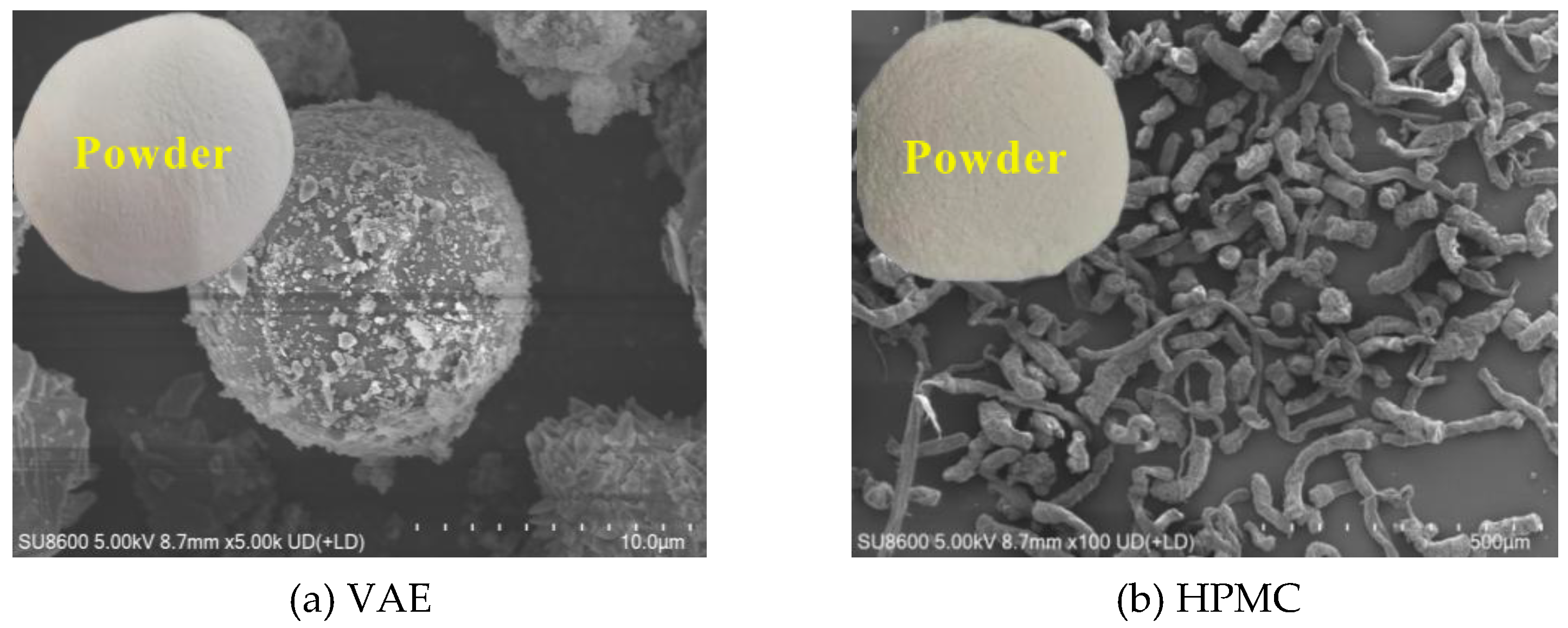

VAE was supplied by Langfang Tianya Energy-Saving Technology Co. HPMC, from Chuangsheng Building Materials Chemical Co., Ltd., exhibits carbonisation and discoloration temperatures of 280-300 °C and 190-200 °C, respectively. As shown in

Figure 2, VAE particles are spheroidal, whereas HPMC adopts a chain-like morphology. Their chemical compositions are listed in

Table 2.

The fine aggregate used in this experiment is Zhengding River sand, with a mud content of less than 1% and a moisture content of less than 0.3%. After screening and grading, the fineness modulus is 2.63, belonging to medium sand and continuous grading in Zone II.

Alkali activated solution (AAS) was prepared by mixing sodium hydroxide and water glass. Sodium hydroxide got from Longbang Chemical in Cangzhou City, Hebei Province, with a purity of ≥99% and a pH greater than 14. Water glass was produced from Bengbu Jingcheng Chemical Co., Ltd., with a pH of 11.3 and a solid content of 34.8%. Both NaOH solution (10 mol/L) and water glass solution need to be prepared one day before experiment. Na2SiO3 solution was prepared by mixing industrial grade water glass and water in a volume ratio of 1:1. Then the two solutions were mixed in proportion according to the experimental design. The water used meets the requirements of the “Standard for Water Used in Concrete Mixing” JGJ 63-2006.

2.2. Experimental Design

Based on the previous research foundation and practical engineering application requirements [

20], this paper designed 7 Mixture proportions as shown in

Table 3. The effects of HPMC and VAE dosage on the working performance, mechanical properties (compressive, flexural, tensile strength and adhesive strength) and durability of GP mortar were systematically investigated.

Considering the non-negligible influence of the environment on the service life of adhesive mortars, this paper designed three curing conditions, namely, standard curing (E1, T≈20℃, RH.≥90%), natural curing (E2, indoor ambient temperature environment) and natural sealing curing (E3, indoor sealing curing), to investigate the influence of curing environment on the mechanical properties of GP mortar. The effects of three unfavorable environments, i.e., water immersion, sulfate attack and high temperature, on the durability of GP-adhesive mortars were further analyzed.

2.3. Experimental Method and Process

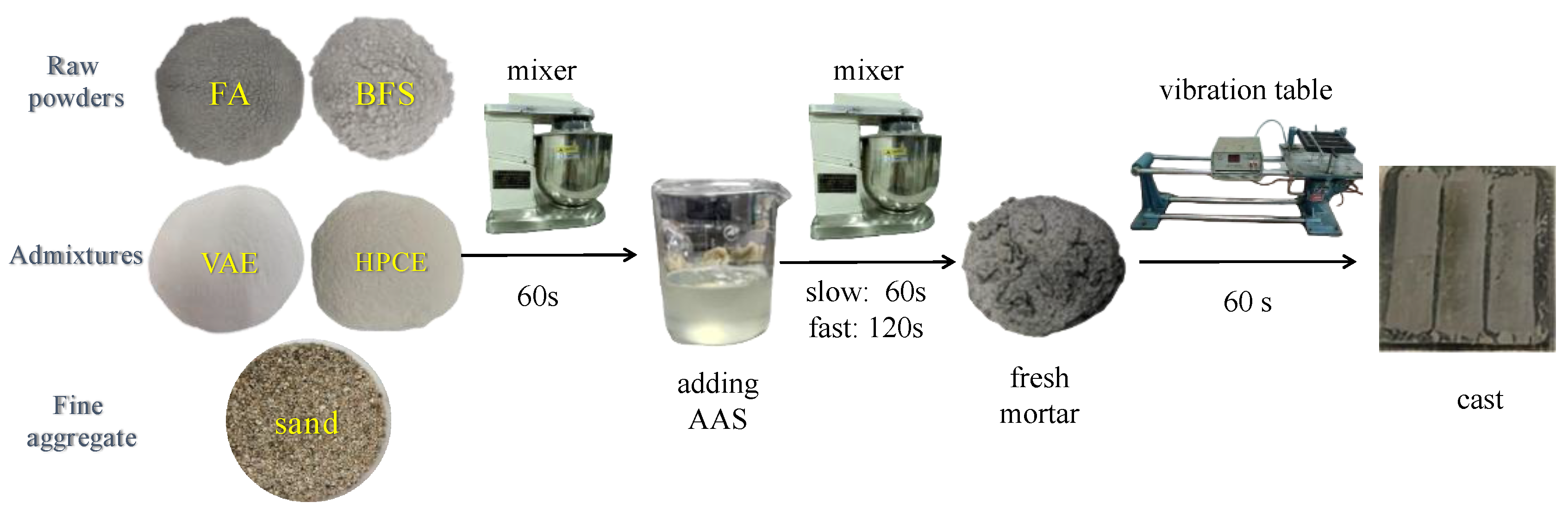

The GP adhesive mortar preparation route is illustrated in

Figure 3. Specimens were demoulded after 24 h and subsequently cured under the designed curing environments until the curing age.

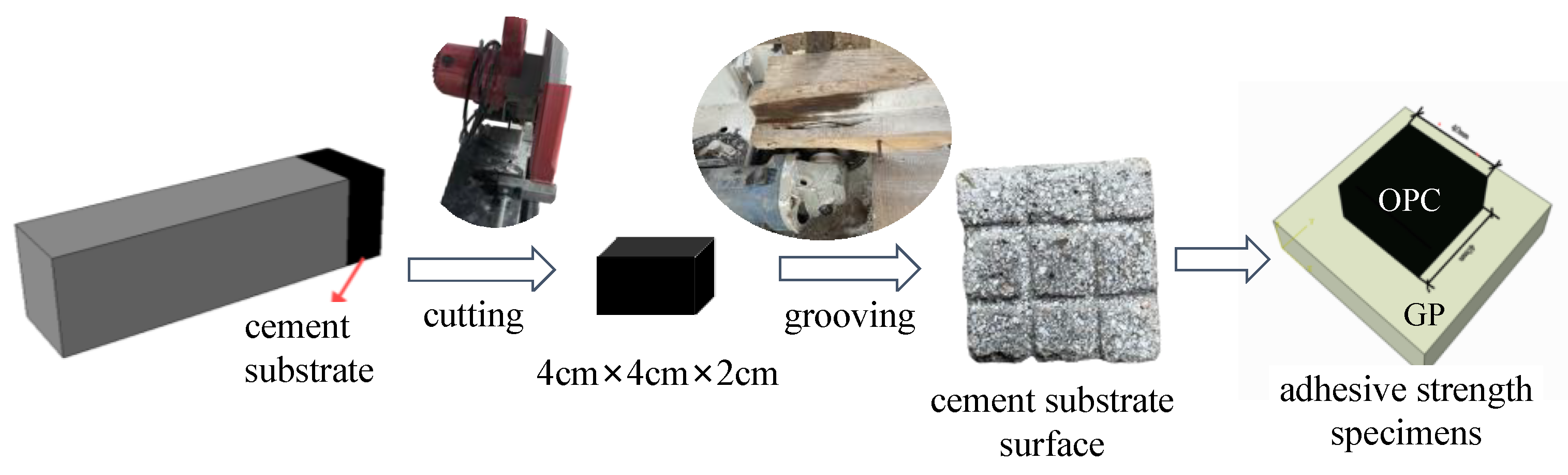

The cement mortar blocks (4cm×4cm×16cm) were cut into 4cm×4 cm×2cm cement substrate with a cutting machine, after 28 days of standard curing. In order to reduce the testing error of tensile adhesive strength, 2 mm depth were grooved on the adhesive surface of the cut off cement substrate blocks, using a custom-fabricated apparatus (

Figure 4). When the fresh GP mortar casting is completed, the cement substrates were placed on the upper surface of the fresh GP mortar, to make the adhesive strength specimens. Then the adhesive strength specimens were placed in different curing environments and cured to age for adhesive strength testing.

The setting time and fluidity of the GP mortars were determined according to specifications GB/T 1346-2011 and GB/T 2419-2005 respectively. Flexural and compressive strengths were referred to GB/T 17671-2021. Split tensile strength was obtained according to GB/T29417-2012, and the test methods for tensile adhesive strength were carried out with reference to JGJ/T70-2009 and JC/T 547-2017. The adhesive strength of GP mortar-cement matrix adhesive strength specimens was carried out at different ages, using the adhesive strength apparatus shown in

Figure 5.

The water resistance, acid resistance and high temperature resistance experiments were carried out on GP mortars specimen, after curing for 28 days. The water resistance experiment was carried out in a water tank,in the standard curing room. During the soaking period, the water surface must be always kept above 2cm of the GP specimens. After 14 days of soaking, take the specimens out and wipe off its surface water, then leave it at room temperature for 1 hour for strength testing.

The sulfate corrosion experiment was conducted, according to GB/T50082-2024, as shown in

Figure 6. Thermal aging experiment was carried out according to JC / T 547-2017. The existing results show that the maximum temperature of the exterior wall can reach 88.6°C during the high temperature period in summer [

21]. Therefore, the maximum temperature of the thermal cycle is set to 80°C, and the minimum temperature is 20°C. After 14 days of thermal cycling, the mechanical properties of GP mortar were measured.

In order to clearly characterize the effects of water immersion, sulfate attack, and high temperature on the mechanical properties of GP mortars, the corrosion resistance coefficient

Ki was introduced to characterize the resistance of GP mortars to the environments, as shown below:

Where: Ki - corrosion resistance coefficient (%); fj0 - the strength before erosion, MPa; fjn - the strength after erosion, MPa; “i=w” - immersion in water; “i=s” - sulfate attack; “i=T” - high temperature; fc (j=c) - compressive strength; fcf (j=cf) - flexural strength; ft (j=t) - tensile adhesive strength; fa (j=a) - tensile adhesive strength.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out using a SmartLab 9KW X-ray diffractometer manufactured by Rigaku Corporation of Japan, with a scanning speed of 5°/min, a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning range of 5° to 100°. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) test was conducted by HITACHI, Japan, focusing on the analysis of the microstructure at the interface between the adhesive mortar and the substrate.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Workability

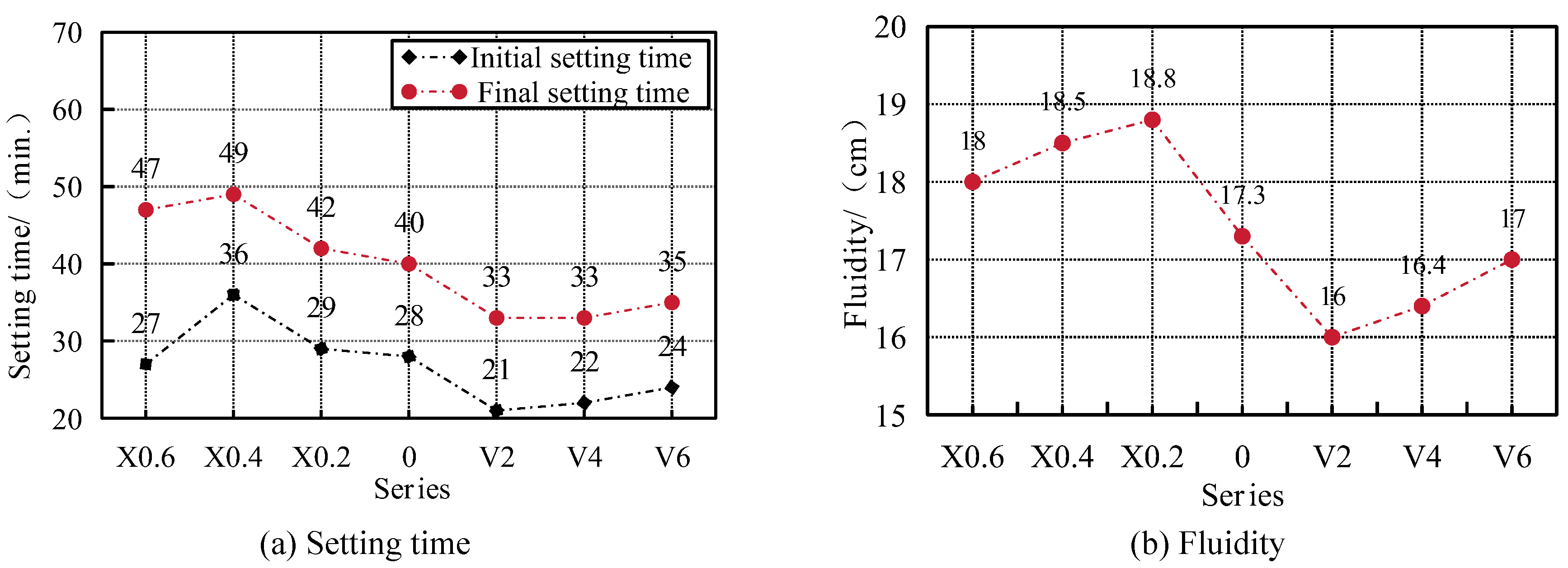

The effects of HPMC and VAE dosage on the working properties of GP mortar are shown in

Figure 7. Comparison of

Figure 7(a) reveals that, with the increase of HPMC dosage, the initial and final setting time of GP mortar shows a tendency of increasing and then decreasing. When 0.4% of HPMC was added, the initial and final setting times were extended by 28.6% and 22.5%, respectively. This indicates that the addition of appropriate HPMC can prolong the initial and final setting time of GP mortar.The effect of VAE on the initial and final setting time of GP mortar showed a tendency of shortening first and then slightly increasing, and its thickening effect was more significant at low dosage, which shortened the setting time. However, with the further increase of VAE dosage, its ability to retain moisture increased, instead of prolonging the hydration reaction time, which led to an increase in the setting time [

22].

The effect of HPMC on the flowability of GP mortar showed a tendency of increasing and then decreasing, and reached the maximum value at a dosage of 0.2% (4.1% increase over the baseline group). This is mainly due to the high water retention of cellulose ether, which helps water to form a water film between mortar particles, reduces the frictional resistance between solid particles, and increases the inter-slurry fluidity. However, too much HPMC will adsorb free water through hydrogen bonding, increasing the viscosity of the slurry and leading to a decrease in flowability. The influence law of VAE on the flowability of GP mortar is similar to that of the setting time, and when the dosage is 2%, the VAE absorbs water within the mortar, resulting in a significant decrease in the flowability, while with the increase in the dosage, the film-forming lubrication of the VAE begins to appear [

23], and the flowability is instead improved.

3.2. Mechanical Strength

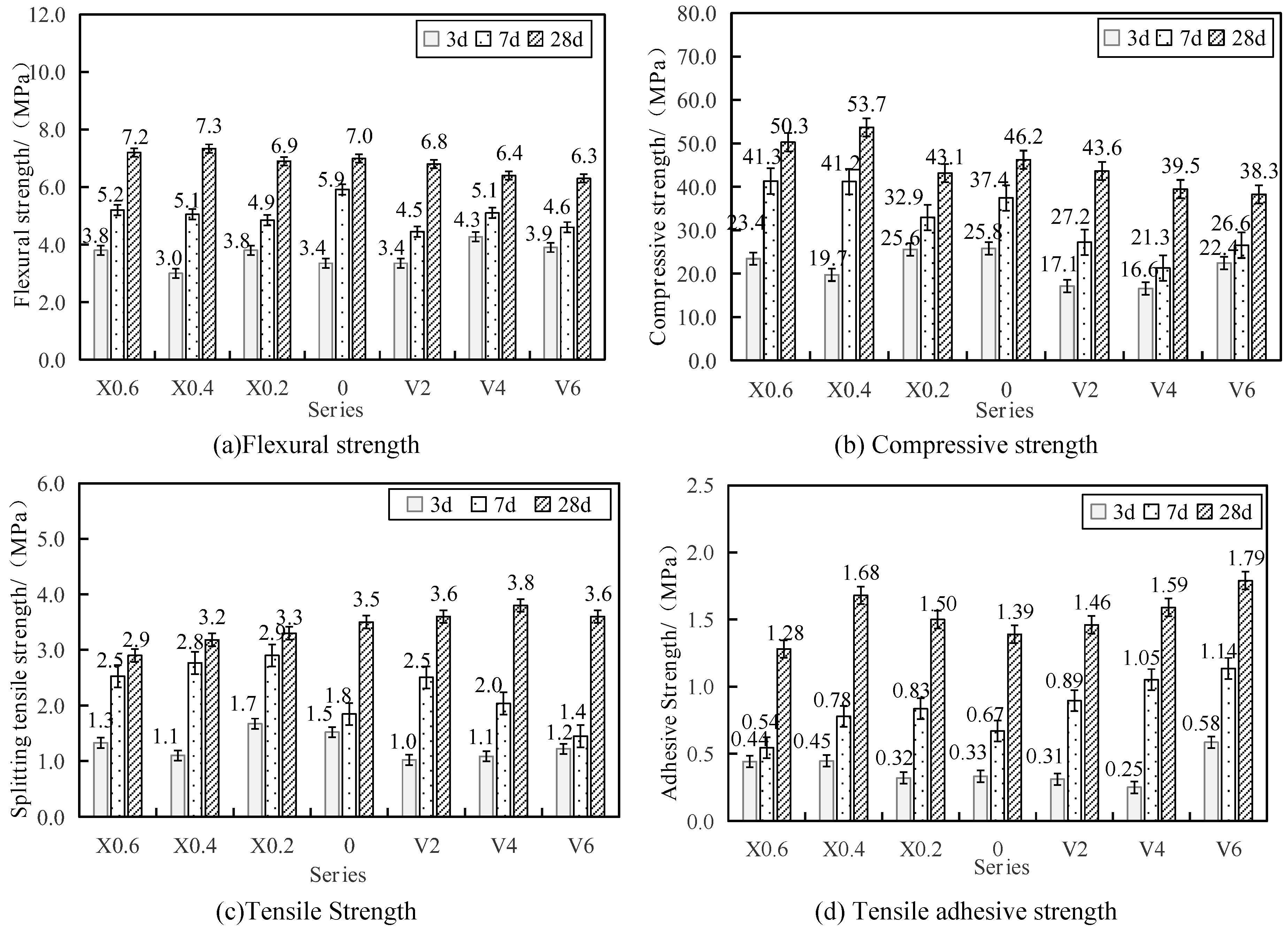

By comparing the mechanical properties of GP mortars with different dosages of HPMC and VAE, as shown in

Figure 8, it was found that with the increase of HPMC dosage, the flexural strength of GP mortar showed a slight upward trend overall, the compressive strength value first increased and then slightly decreased, and the 28 day tensile strength gradually decreased. However, the 7-day tensile strength of GP mortar mixed with HPMC was higher than that of the reference group. The adhesive strength shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. However, excessive HPMC dosage leads to the formation of air bubbles within the mortar due to its air-entraining effect, which reduces the compactness and homogeneity of the mortar, thereby weakening its strength [

24].

The addition of VAE is detrimental to the flexural and compressive strength of GP mortar. With the increase of VAE content, the flexural and compressive strength decrease. But it can slightly improve the tensile strength of GP mortar and significantly enhance the adhesive strength of GP mortar. When the VAE content reaches 0.6%, the adhesive strength increases by over 28% at 7d and 28d. The mechanism of action is that the film-forming process of VAE is synchronized with the hydration reaction of GP mortar [

25]. The film-forming amount of VAE increases with the increase of VAE content, thereby enhancing the adhesive strength and tensile strength of GP mortar. However, the water absorption of VAE may delay the hydration reaction process, leading to incomplete reaction of the cementitious material and resulting in a decrease in the flexural and compressive strength of GP mortar [

17,

26].

3.3. Durability

The Chinese regulations clearly stipulate the adhesive strength limits of adhesive mortar before and after immersion in water. Therefore, the changes in mechanical properties of 7 GP mortar ratios, before and after immersion in water, were compared. At the same time, further research was conducted on the high-temperature aging resistance and sulfate corrosion resistance of GP adhesive mortar.

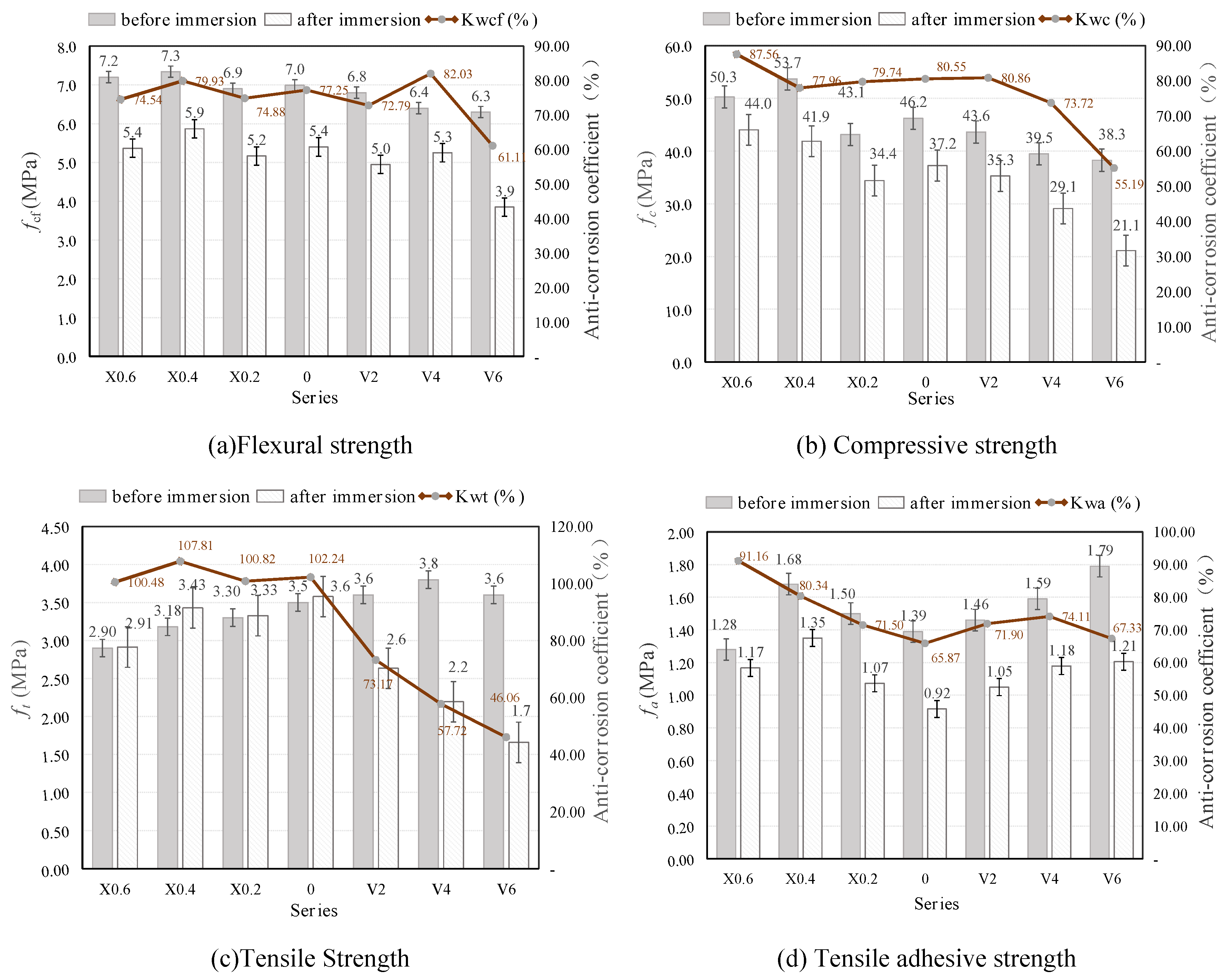

3.3.1. Water Immersion

Figure 9 shows that after immersion, except for a slight increase in tensile strength of the reference group and HPMC group, the mechanical properties of other GP mortars have decreased. By comparing the corrosion resistance coefficients of various series before and after immersion, it can be seen that the corrosion resistance coefficients of GP mortar with HPMC have increased slightly compared to the reference group, in terms of flexural, compressive, and tensile strength. HPMC has a significant effect on improving the adhesion strength-corrosion resistance coefficients of GP mortar, with an increase of over 25%. With the increase of VAE content, the adhesion strength-corrosion resistance coefficient of GP mortar shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. When the content is 4%, it increases by about 8%. However, the addition of VAE is detrimental to the flexural, compressive, and tensile strength of GP mortar after immersion. The decrease in tensile strength-corrosion resistance coefficient is particularly significant. The microstructure changes of GP mortar shown in SEM images can precisely explain the above phenomenon.

3.3.2. Sulphate Attack

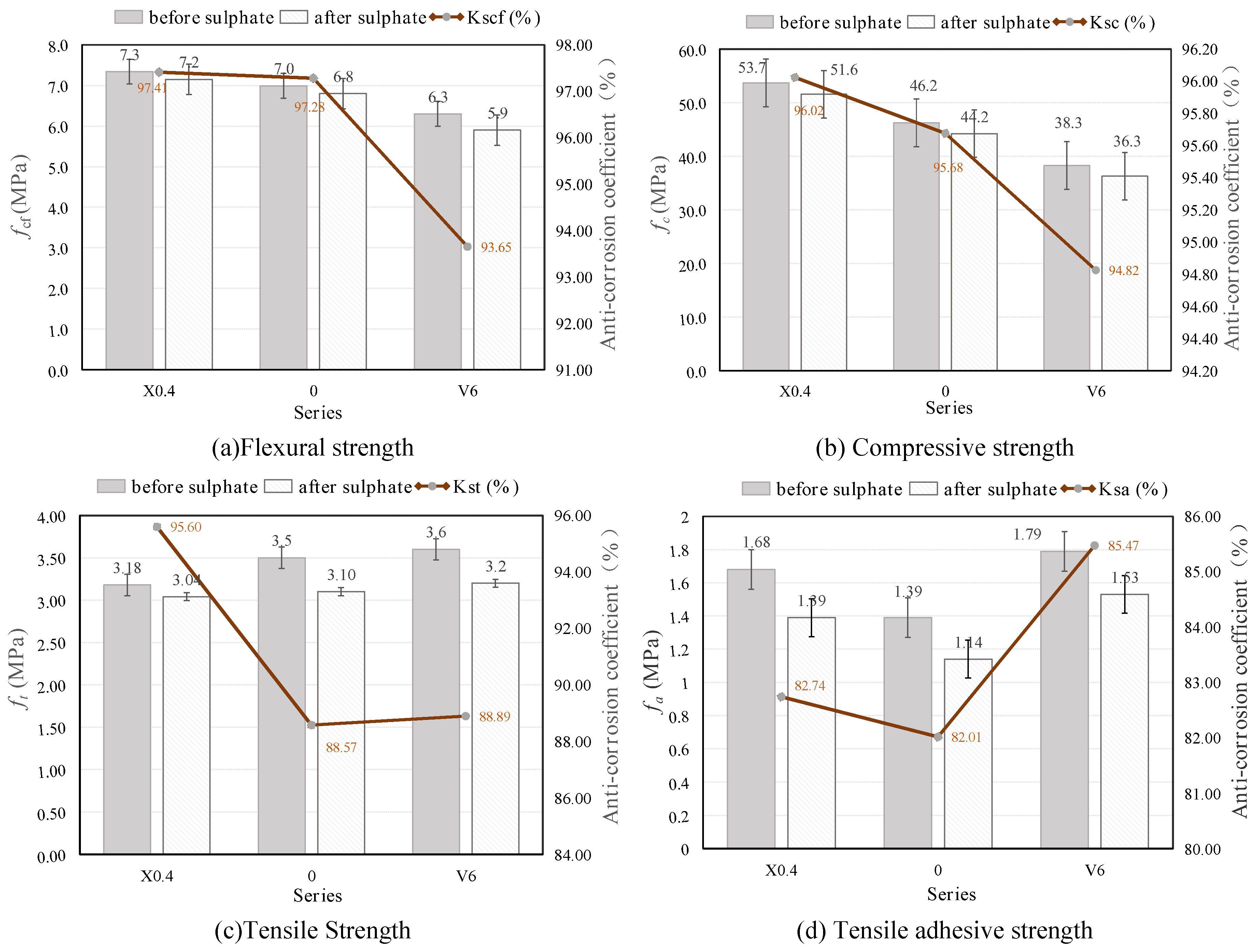

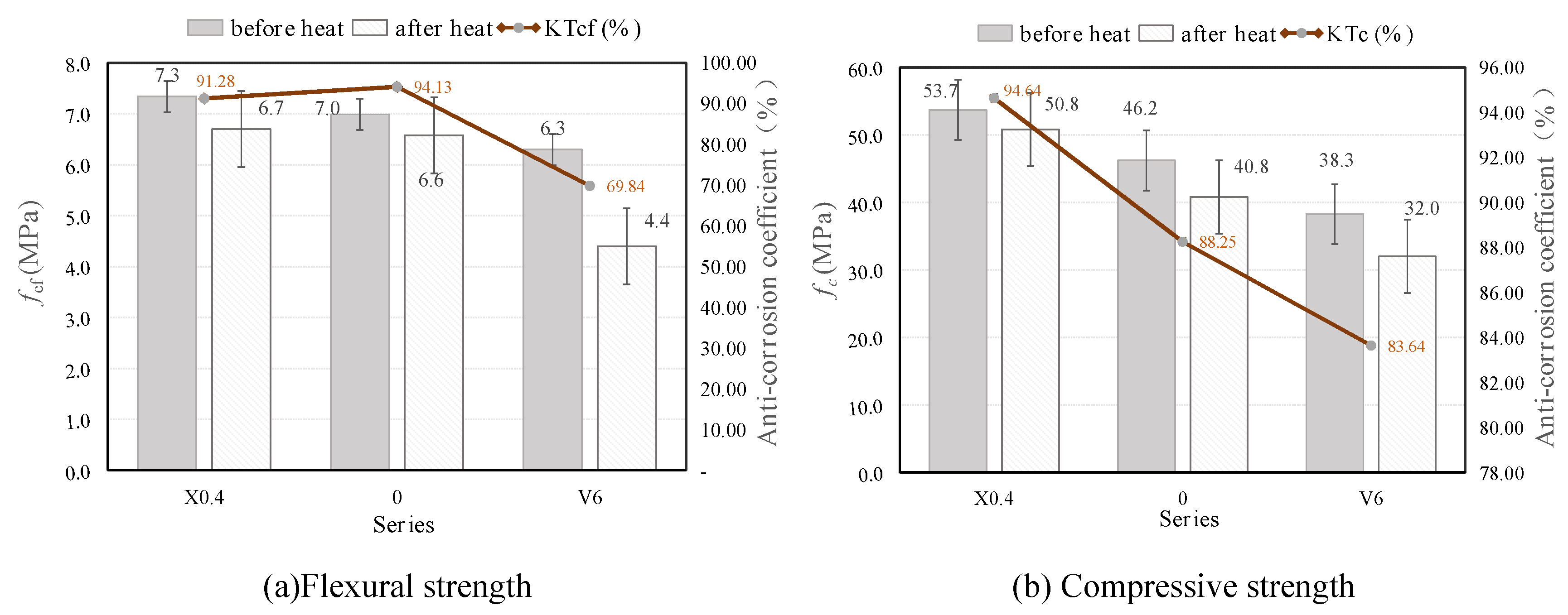

In order to further compare the effects of HPMC and VAE content to GP mortar on its resistance to sulfate attack and high temperature resistance, this paper selected the X0.4 and V6 series with good adhesion, based on the previous experimental results, and compared them with the reference group to evaluate the improvement effect of HPMC and VAE on the durability of GP mortar.

Figure 10 compares the mechanical property changes before and after sulfate attack of X0.4, V6 and reference group. It can be clearly seen that HPMC helps to improve the ability of GP mortar to resist sulfate attack, and the coefficients of various mechanical properties against sulfate attack are larger than those of the reference group, especially the enhancement effect on tensile strength. In contrast, the improvement effect of VAE was not ideal. The addition of VAE had a negative effect on the sulfate corrosion resistance of all mechanical properties of GP mortar, except for the resistance of adhesion strength of GP mortar. This is related to its loose microstructure, and sulfate ions are more likely to enter the interior of the GP matrix, resulting in a decrease in acid resistance.

3.3.3. High Temperature

The changes in the mechanical properties of X0.4, V6 and the reference group before and after high temperature cycling at 80°C-20°C are shown in

Figure 11. The addition of 0.4% HPMC not only did not obviously reduce the mechanical properties of GP mortar after high temperature, but even increased the high-temperature corrosion resistance coefficient of GP mortar’s flexural and tensile strength by about 6%. The addition of VAE significantly reduced the high-temperature resistance of GP mortar, especially for its flexural and adhesive strength. After high temperature, the corrosion resistance coefficient of flexural and adhesive strength decreased by about 24% and 13%, respectively. It is speculated that the above results are related to the structural damage of VAE polymer film. Existing research has confirmed that the polymer film formed by VAE in cement mortar undergoes structural damage after a 70 degree heat aging test [

27].

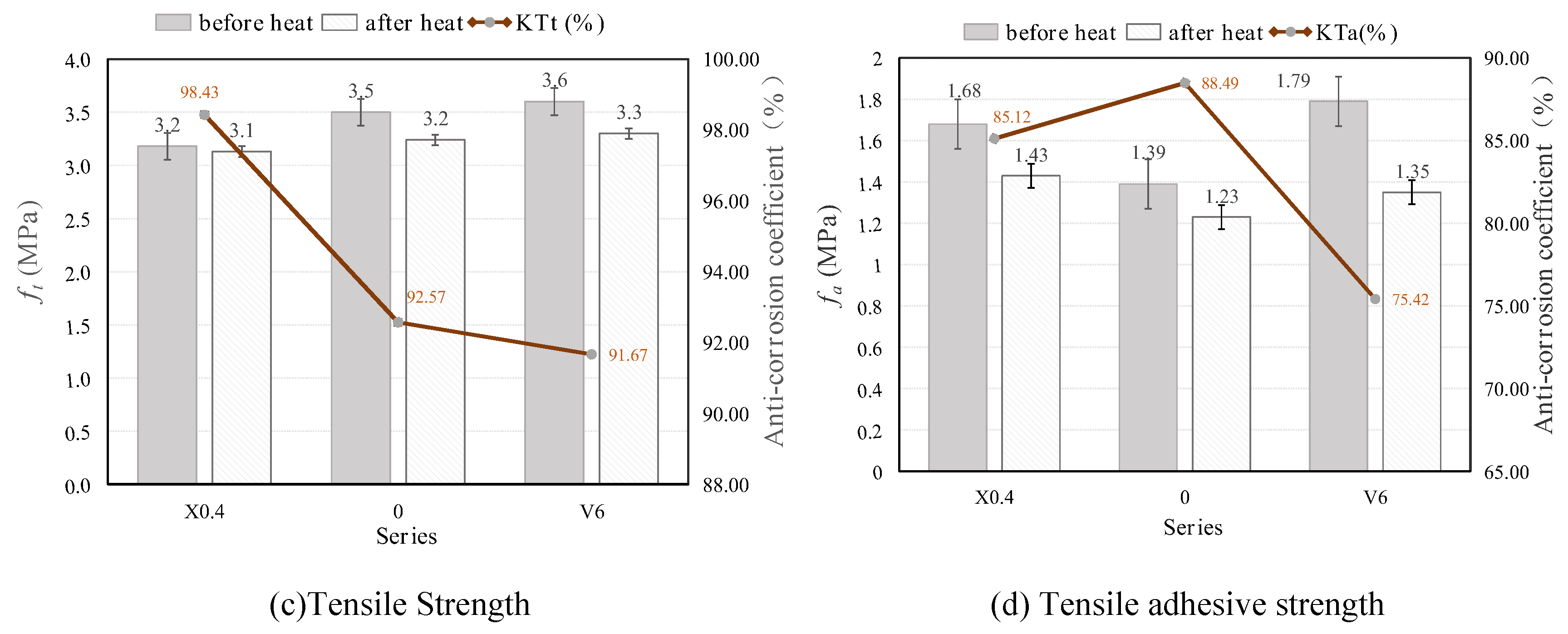

3.3.4. Effect of Curing Conditions

The effects of three curing environments, E1 (standard curing), E2 (natural curing) and E3 (natural sealing curing), on the flexural, compressive, tensile, and adhesive strengths of the reference, X0.4, and V6 series, at the ages of 3d, 7d, and 28d are shown in

Figure 12. The results reveals that the standard curing and natural sealing curing conditions are more favorable to the development of the mechanical properties of GP mortar. With the increase of age, the natural sealing curing can achieve the effect of equaling or even exceeding the standard curing. This is consistent with the results of the current study [

28]. It is impossible to achieve a standard curing environment during on-site construction. Therefore, the mechanical properties of GP mortar can be guaranteed by sealing during construction.

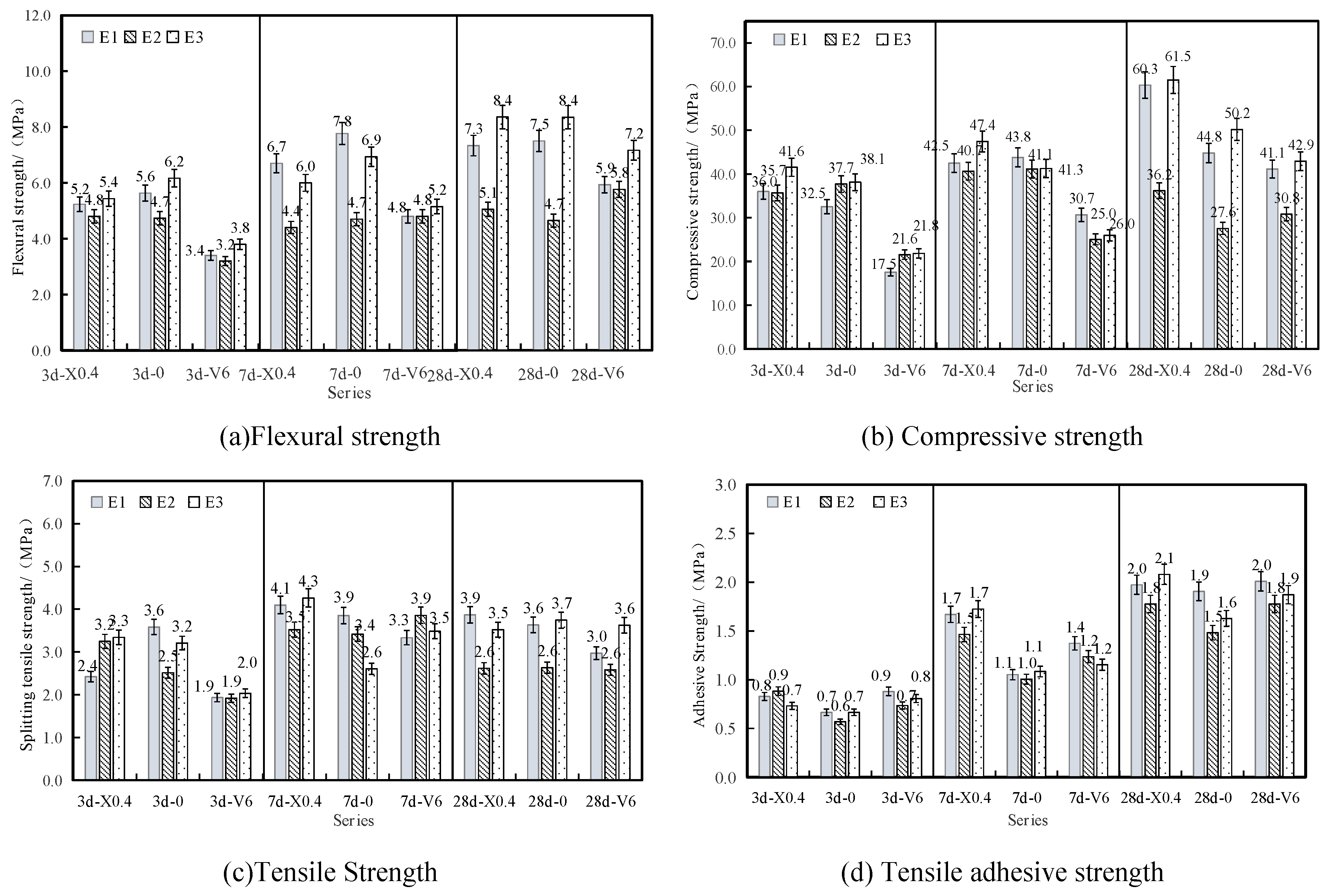

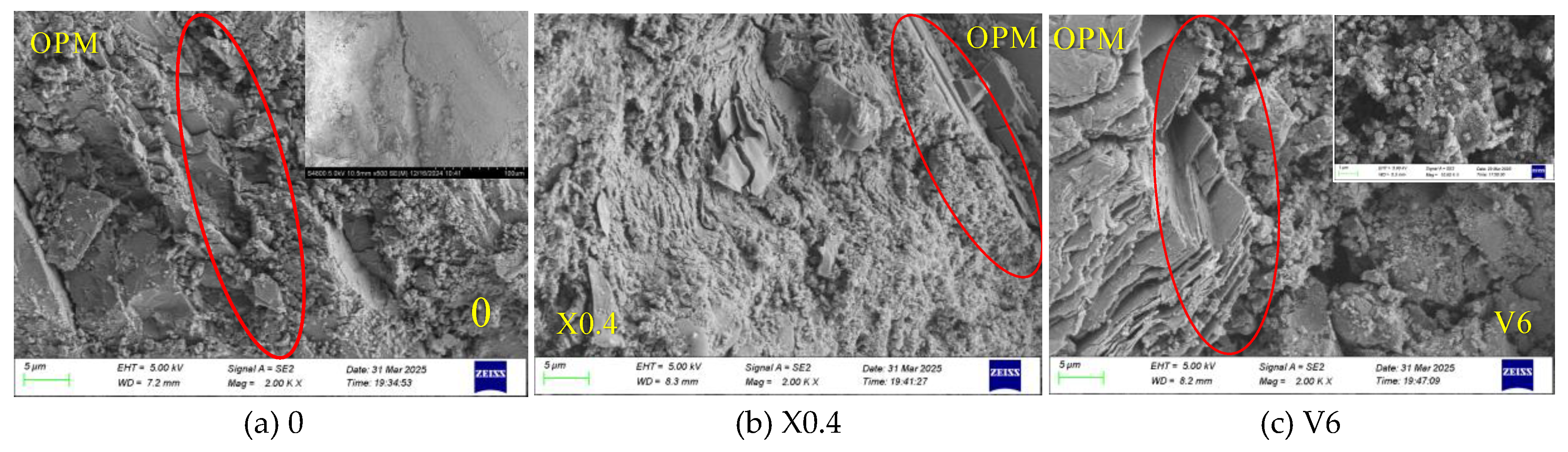

3.4. SEM Analysis

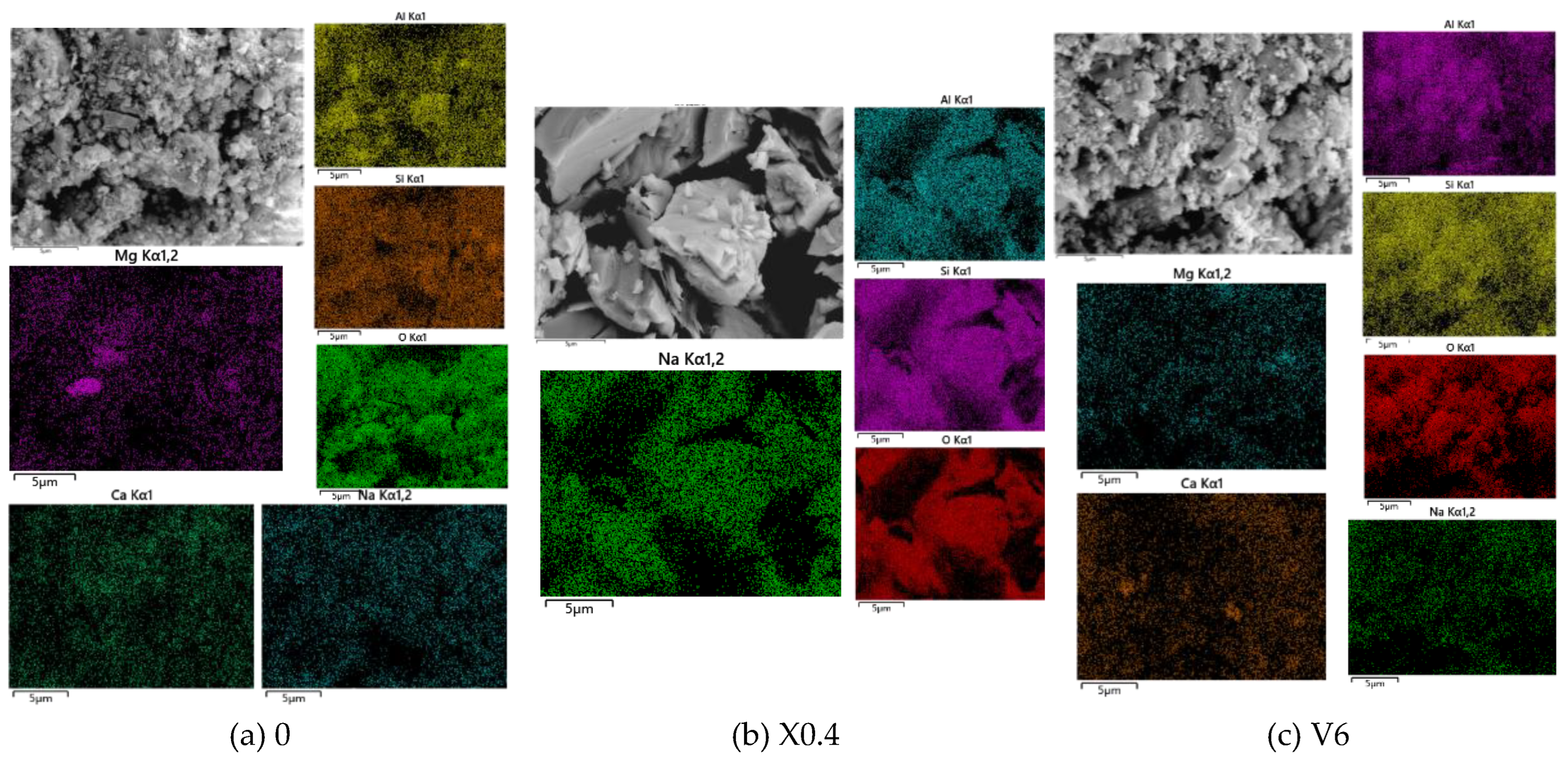

A comparison of the SEM micrographs for sample X0.4 (with 0.4% HPMC), sample V6 (with 6% VAE), and the reference group (

Figure 13) reveals distinct microstructural features. The micrograph of the reference group, shown in

Figure 13(a), displays a relatively dense matrix structure. However, prominent cracks are observable at the adhesive interface with the cement mortar substrate. This observation is consistent with the mechanical property results for the reference group, which exhibited higher compressive strength but lower tensile and adhesive strengths. In contrast, the inter-facial transition zones between X0.4/V6 series and the cement-based substrate exhibited a more continuous and compact structure compared to the reference group, with no obvious cracks observed. This precisely explained why the adhesive strengths of X0.4 and V6 were higher than that of the reference group.

Further examination of the V6 sample, specifically through a high-magnification (10,000x) SEM image, revealed that its inter-facial surface was covered by a distinct, film-like material. This polymer film, formed by the VAE emulsion, is understood to substantially enhance the inter-facial adhesive performance through two key mechanisms. Firstly, it creates a physical “bridging effect” that spans across microcracks at the interface, effectively stitching the matrix together. Secondly, it promotes chemical adhesion through the bonding of hydroxyl (-OH) groups within the polymer with the hydration products of the cementitious substrate [

29,

30].However, while beneficial for adhesion, the presence of this polymer film introduces a “soft interlayer effect,” which consequently limits the potential gains in the compressive strength of the geopolymer (GP) mortar [

23,

31]. This trade-off is corroborated by the bulk microstructure of the V6 mortar, as shown in

Figure 13(c). Compared to both the X0.4 and reference samples, the V6 matrix appears visibly looser and more porous. It is characterized by the presence of multiple irregular cracks and a higher volume of unreacted substances. This less-dense internal structure can be attributed to the retarding effect of VAE on the geopolymerization and hydration reactions. The addition of the VAE polymer slows the reaction kinetics, leading to an incomplete reaction and a subsequent increase in unreacted precursor materials within the final hardened matrix.

According to the mapping diagrams of the three samples (

Figure 14), more Na, Al, Si and O substances (presumably N-A-S-H gel) were generated in X0.4 sample (with 0.4% HPMC), while the signal of calcium containing substances was weak and could not be clearly shown in the spectrum. It can be seen that the addition of HPMC is more conducive to the generation of N-A-S-H. It is believed to be related to the high content of sodium sulfate in HPMC. Existing research shows that sodium sulfate can promote the formation of N-A-S-H gels [

32]. This conclusion was also confirmed in XRD images.

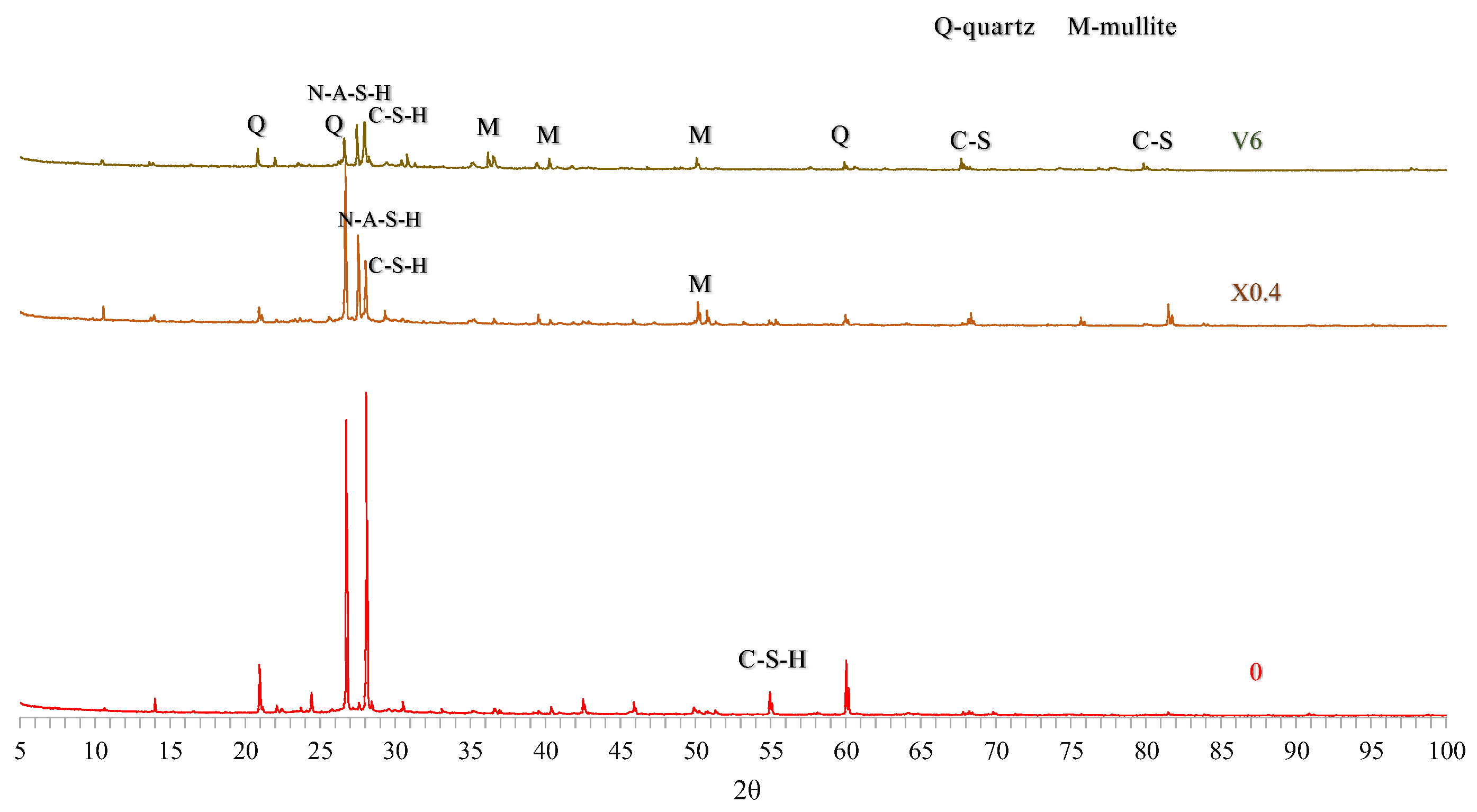

3.5. XRD Analysis

The XRD patterns of X0.4, V6, and reference group samples after 28 days of curing are shown in

Figure 15. The results indicate that, compared to the reference group without additives, the diffraction peaks of amorphous silica and C-S-H gel in X0.4 and V6 samples were significantly weakened. The increase in sodium aluminium silica [

33] is more pronounced in the X0.4 samples’ XRD pattern. Combined with the mapping results, it is speculated that the sodium aluminium silica is N-A-S-H gel. These microstructural changes explain why the durability of the X0.4 specimen is higher compared to the reference group and V6. Additionally, mullite and silicate (C-S) unreacted phases were observed in the XRD spectra of X0.4 and V6. The presence of unreacted phases confirms the delayed hydration process of geopolymers due to the addition of HPMC and VAE, consistent with mechanical, durability, and SEM observations.

The mechanisms of HPMC and VAE differ significantly. For VAE, the effect arises from the hydrolysis of acetate ester groups (-OCOCH

3) in the VAE copolymer under alkaline conditions, forming acetate ions (CH

3COO

−) and polyvinyl alcohol chains. The CH

3COO

− then complex with Ca

2+, forming less soluble calcium acetate (Ca(CH

3COO)

2), altering the ionic concentration and equilibrium, thereby inhibiting the nucleation of C-S-H gel [

34]. HPMC, on the other hand, operates through multiple mechanisms: its large molecular chains with strong hydrophilicity and adsorption capacity adsorb onto the surfaces of cementitious materials, forming a physical barrier that delays the reaction between alkaline activators and reactive particles. Additionally, HPMC’s excellent water-retaining ability prevents premature water loss, promoting sustained hydration. This “internal curing” effect supports long-term hydration and enhances the development of later strength [

35]. The air-entraining effect of HPMC also improves workability and reduces setting time, leading to a denser microstructure and enhanced mechanical and durability performance.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the influence and mechanism of HPMC and VAE on the performance of industrial solid waste based GP mortar. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) The appropriate amount of HPMC (such as 0.4%) can promote geopolymer reaction and optimize the microstructure by virtue of its water retention, thereby enhancing the compressive and adhesive strength of GP mortar. However, excessive HPMC will reduce the compactness of mortar due to significant thickening and excessive air entrainment, which will have adverse effects on the flexural and splitting tensile strength.

(2) Although the addition of VAE continuously reduces compressive and flexural strength, it significantly improves the splitting tensile strength and adhesive strength, with a peak adhesive strength of 1.79MPa at a dosage of 6%. At the micro level, VAE consumes OH- and Ca2+ in alkaline environment, inhibits geopolymerization reaction and the formation of C-S-H gel, resulting in loose matrix structure. But the polymer film formed by it can effectively bridge the reaction products, enhance the inter-facial adsorption force, and is the key to improving the adhesive strength.

(3) In terms of durability, HPMC can significantly improve the water and acid resistance of GP mortar, and can still enhance the compressive and tensile corrosion resistance coefficients at high temperatures. On the contrary, VAE exhibits adverse effects on the long-term durability of mortar. In addition, research has shown that sealed curing can achieve comparable results to standard curing and has engineering application value.

Both HPMC and VAE effectively improved the adhesion performance of GP mortar, but showed antagonistic for other mechanical properties of GP mortar. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct research on the composite system of the two polymers to synergistically optimize the comprehensive performance of GP mortar.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Hebei Province Department of Education Fund (QN2025425), Hebei Province Foundation for Returned Scholars (C20220320), Dr. startup funds (1181389), and Sub project of China Construction Engineering Corporation’s Technology Research and Development Project (CSCEC-PT-015-203).

References

- Majhi, R.; Nayak, A.; Mukharjee, B. Characterization of lime activated recycled aggregate concrete with high-volume ground granulated blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cheng, G.D.; Huang, T.Y.; et al. Study on properties of fly ash-slag based geopolymer mortar. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 38, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wu, B. Study on shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with textile-reinforced geopolymer mortar. J. Eng. Mech. 2019, 36, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.Y.; Yang, J.S. Overview of cementitious properties of geopolymer mortar and its concrete. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.L. Study on Mechanical Properties and Durability of Basalt Fiber Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.H. Preparation and Performance of Na-Fly Ash Geopolymer. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ohama, Y. Polymer-based admixtures. Cem. Concr. Res 1998, 20, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.H.; Ma, B.G.; Jian, S.W.; et al. Influence of cellulose ether molecular parameters on mechanical properties of cement paste. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 35, 2371–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, K.; Ma, K.; Wang, J.; et al. Influence of cellulose ethers on rheological properties of cementitious materials: A review. J. Build. Eng 2024, 95, 110347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourchez, J.; Grosseau, P.; Ruot, B. Changes in C3S hydration in the presence of cellulose ethers. Cem. Concr. Res 2010, 40, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Research on Formula Optimization of Self-Compacting Concrete Admixtures. Master’s Thesis, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brachaczek, W. Influence of Cellulose Ethers on the Consistency, Water Retention and Adhesion of Renovating Plasters. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Wroclaw, Poland, 2019.

- Wang, P.M.; Zhao, G.R.; Zhang, G.F. Action mechanism of redispersible polymer powder in cement mortar. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 46, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.J.; Zhang, L.L.; Liu, Y.X.; et al. Comparative study on properties of cement-based pervious concrete modified by redispersible latex powder and silica fume. Concr. Cem. Prod 2018, 12, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Q.; Chai, H.C.; Zhang, X.T.; et al. Study on redispersible latex powder modified cement-based thin spray materials. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 41, 3394–3402. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H.; Zhao, W.J. Research progress on redispersible latex powder. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 35, 4038–4043. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.N.; Liang, J.F.; Chen, L. Study on mechanical properties of recycled powder-redispersible latex powder composite cement mortar. Concrete 2023, 2, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.H.; Mao, J.B.; Zhang, J.X.; et al. Modification effect of redispersible latex powder on cement mortar. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 30, 915–919. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.L.; Liu, B.; Ma, L.G.; et al. Experimental study on working performance of modified high-performance polymer cement mortar. Concrete 2022, 1, 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, C.W. Study on adhesive strength and Durability of Geopolymer Mortar. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Science and Technology, Shijiazhuang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, P.; Wang, L.L. Interfacial temperature of EPS external wall insulation system in high temperature environment in summer. Urbanism Archit. 2019, 16, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, L.; Yanmin, J. Effect of Redispersible Latex Powder and Fly Ash on Properties of Mortar. Coatings 2022, 12, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Feng, H.C.; Zhou, K. Mix ratio optimization and frost resistance of VAE latex powder modified cement mortar. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 42, 3462–3469. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.M. Effect of emulsion compounding on polymer cement waterproof coating film in tile adhesive system. Mater. Rep. 2022, 36, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Ning, B.; Na, F.; et al. Study on properties of re-dispersible latex powder and polypropylene fiber-reinforced lightweight foam concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Bai, E.L.; Zhou, J.P.; et al. Mechanical properties of VAE latex powder/carbon fiber composite modified concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2024, 27, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, P.Y.; Wang, D.M.; Wang, Q. Effects of Polymers on Waterproofing and Mechanical Properties of Mortar after Heat Treatment. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 42, 2703. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.K. Investigation on Alkali Activated Materials: Materials to Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Xu, L.L.; Feng, T.; et al. Research progress on waterborne polymer emulsion modified cement mortar. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 40, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Shiao, Y.; Lu, H.N.; Zhang, L.; et al. A polymer latex modified superfine cement grouting material for cement-stabilized macadam: Experimental and simulation study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 413, 134893. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.D.; Chen, W.D.; Zhong, S.Y. Effect of latex particle size on properties of polymer-modified cement-based materials. J. Build. Mater. 2017, 20, 943–949. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Q.F.; Wang, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effect of sodium sulfate on strength and microstructure of alkali-activated fly ash based geopolymer. J. Cent. South Univ. 2020, 27, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.-I.; Song, J.-K. Carbonation characteristics of alkali-activated blast-furnace slag mortar. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 326457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Wang, P.M.; Zhao, G.R. Calorimetric study on the influence of redispersible E/VC/VL terpolymer on the early hydration of Portland cement. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 124, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.Y.; et al. Study on thermal conductivity and pore structure of foamed concrete based on orthogonal test. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 43, 2888–2896. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).