1. Introduction

The physics of the vacuum remains one of the central challenges in modern cosmology and particle physics. Quantum field theory suggests a substantial vacuum energy density from fluctuating fields, whereas observations indicate a vastly smaller value; this mismatch is the

cosmological constant problem [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The standard

CDM model explains the observed expansion with a cosmological constant and accounts for flat galaxy rotation curves by introducing dark matter [

5,

6,

7]. Yet the fundamental nature of dark energy and dark matter remains unknown [

8,

9].

We propose an alternative framework: the

QEV model (

Quantized, Entropy-bounded Vacuum). Vacuum energy is

bounded by microphysics: a UV cutoff at the QCD scale, an IR thermal suppression around

, and normalization at the CMB Wien peak [

10,

11]. Within galaxies, the effective vacuum field manifests through four components that together reproduce flat rotation curves without dark halos, consistent with classic and modern kinematic evidence [

12,

13,

14]. Cosmologically, the resulting expansion history remains compatible with current probes [

15,

16,

17].

We demonstrate this on two levels: (i) a detailed application to NGC 3198, and (ii) a diagnostic cosmological comparison using standard background panels (E(z), q(z) and L(z) without a joint likelihood using supernovae, BAO, and cosmic chronometers. Related ideas in modified gravity and emergent frameworks provide context but differ in mechanism [

18,

19,

20,

21].

This version (v2.1) builds on the theoretical framework introduced in the first preprint (

doi:10.20944/preprints202509.0972.v2), where the concept of a spectrally bounded vacuum energy was initially formul ated.

Scope and diagnostic status.

All cosmological panels in this paper (, , and the transition redshift) are intended as diagnostic illustrations. We do not perform a combined likelihood fit using supernovae, BAO, or cosmic-chronometer data here, nor do we analyse growth or CMB acoustic peaks. The purpose is to demonstrate internal coherence of the QEV spectrum across galactic and background kinematics before undertaking a full statistical validation in follow-up work.

2. The QEV Model: A Bounded–Spectrum Vacuum

2.1. Physical Motivation for the Spectral Exponent

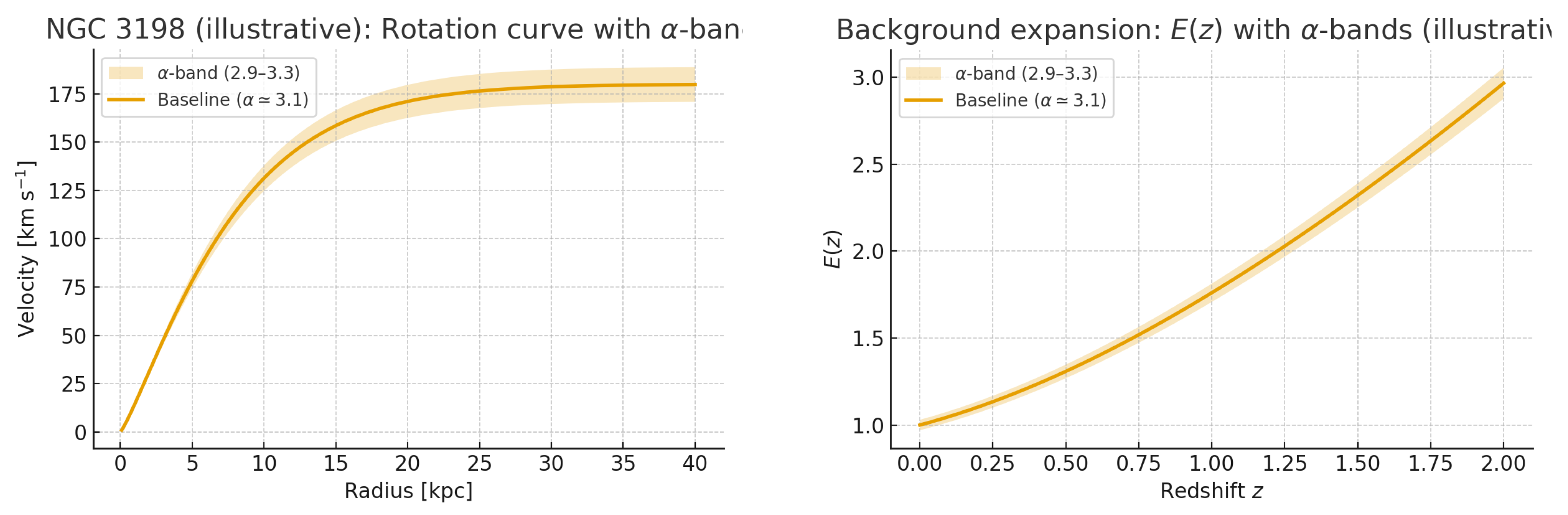

The mid-band spectral slope reflects an effective reduction of active degrees of freedom between the thermal infrared floor and the QCD confinement knee. In this regime, the accessible vacuum modes soften relative to the canonical quartic scaling, consistent with the notion that confinement limits the contribution of short-wavelength excitations while the thermal floor reduces long-wavelength response. Qualitatively, lattice-QCD and effective-field-theory perspectives both indicate that the energy density near the confinement regime departs from a pure Stefan–Boltzmann law through logarithmic and interaction-driven corrections, implying that an intermediate power-law window with is physically plausible. Numerically, we verify that the bounded integral for is plateau-dominated with a smooth window , so that no sharp requirement arises; the results remain stable over (see robustness bands in the figures). This motivates our operational choice without fine-tuning and ties the parameter to the underlying microphysics of confinement and thermal suppression.

The QEV hypothesis assumes a spectrally bounded vacuum: a smooth UV knee at the QCD scale and a thermal IR suppression. In frequency variables the elementary relation

holds, or equivalently

in wavelength. We encode the band–limiting through a smooth window

(double–tanh,

), and model the vacuum energy density as the truncated moment

with a scale–free mid–band slope

and knees at

and

The overall prefactor is fixed by anchoring to the CMB Wien scale.

A QCD-motivated UV bound naturally echoes the SVZ QCD sum-rule program, where non-perturbative condensates enter dispersion relations for hadron observables [

22,

23,

24]. The thermal IR suppression and its response aspect can be framed within linear-response/FDT language [

25]. Empirical evidence that vacuum fluctuations gravitate at lab scales (Casimir) under controlled conditions provides an experimental anchor for the near-field regime [

26].

Model parameters used to generate the rotation-curve components are listed in

Table 3.

Spectral exponent and convergence.

Because

W is smooth in

, edge contributions are exponentially suppressed and Equation (

1) is plateau–dominated; a hard requirement

is not needed. The logarithmic UV sensitivity is , consistent with the measure. Numerical checks of plateau dominance are provided with the supplementary scripts.

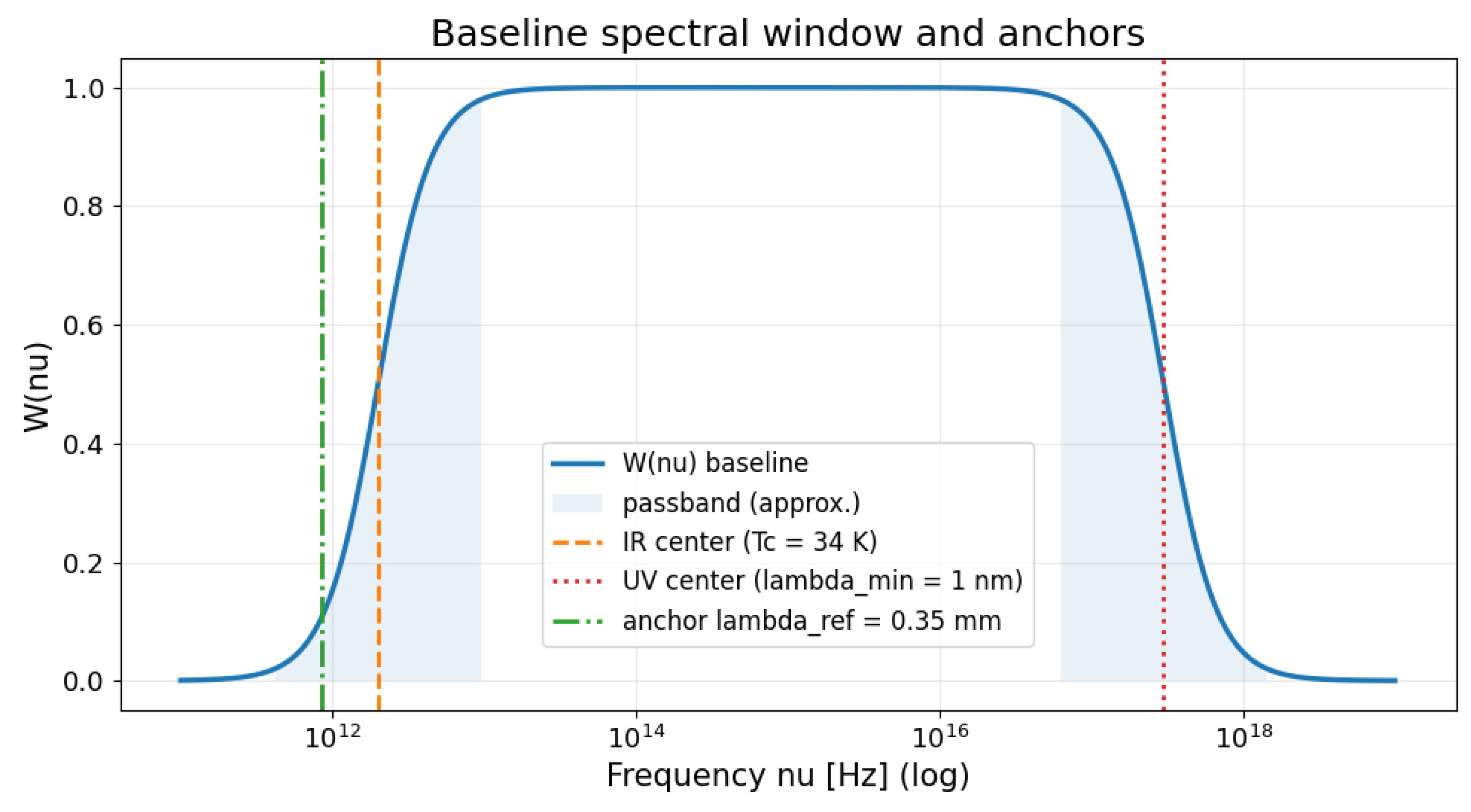

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the bounded spectral window and its two physical anchors: the hadronic (UV) confinement scale and the thermal (IR) CMB scale. We use as the normalization anchor.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the bounded spectral window and its two physical anchors: the hadronic (UV) confinement scale and the thermal (IR) CMB scale. We use as the normalization anchor.

Spectral index .

The parameter represents the effective slope of the bounded vacuum spectrum between the infrared cutoff and the QCD confinement scale. Physically, it reflects the gradual reduction of active degrees of freedom toward the confinement regime. Within the interval – the integrated vacuum energy density remains stable, indicating that the model is not fine-tuned and that its predictions are robust with respect to moderate spectral variations.

IR anchor (thermal).

We fix the infrared anchor by the wavelength form of Wien’s law,

Note. The frequency-peak obeys , which is not simply related by because the maxima in wavelength and frequency representations differ by the Jacobian. We consistently use the wavelength form throughout.

Takeaway.

The pair {, } is thus operationally sufficient to reproduce the required UV leverage and IR onset. See Sect. 2.5 for an explicit radiation–pressure motivation, and Appendix A provides microphysical context and shows that the resulting galaxy–scale behavior does not depend on a single microscopic model once the smooth window is fixed.

2.2. Interpretation and Relation to Prior Work

Our construction is agnostic about modified-gravity field equations; it attributes galactic and cosmological phenomenology to a

bounded vacuum spectrum. This contrasts with classical constant-

viewpoints [

1,

2,

3,

4], MONDian scaling [

13,

27], and emergent-gravity scenarios [

20,

21]. The present paper refines and systematizes our previous components—thermal lift, entropic asymptote, hadronic floor—into a single, unit-consistent framework [

28,

29,

30].

For a robustness analysis of the choice , including a sweep over , see

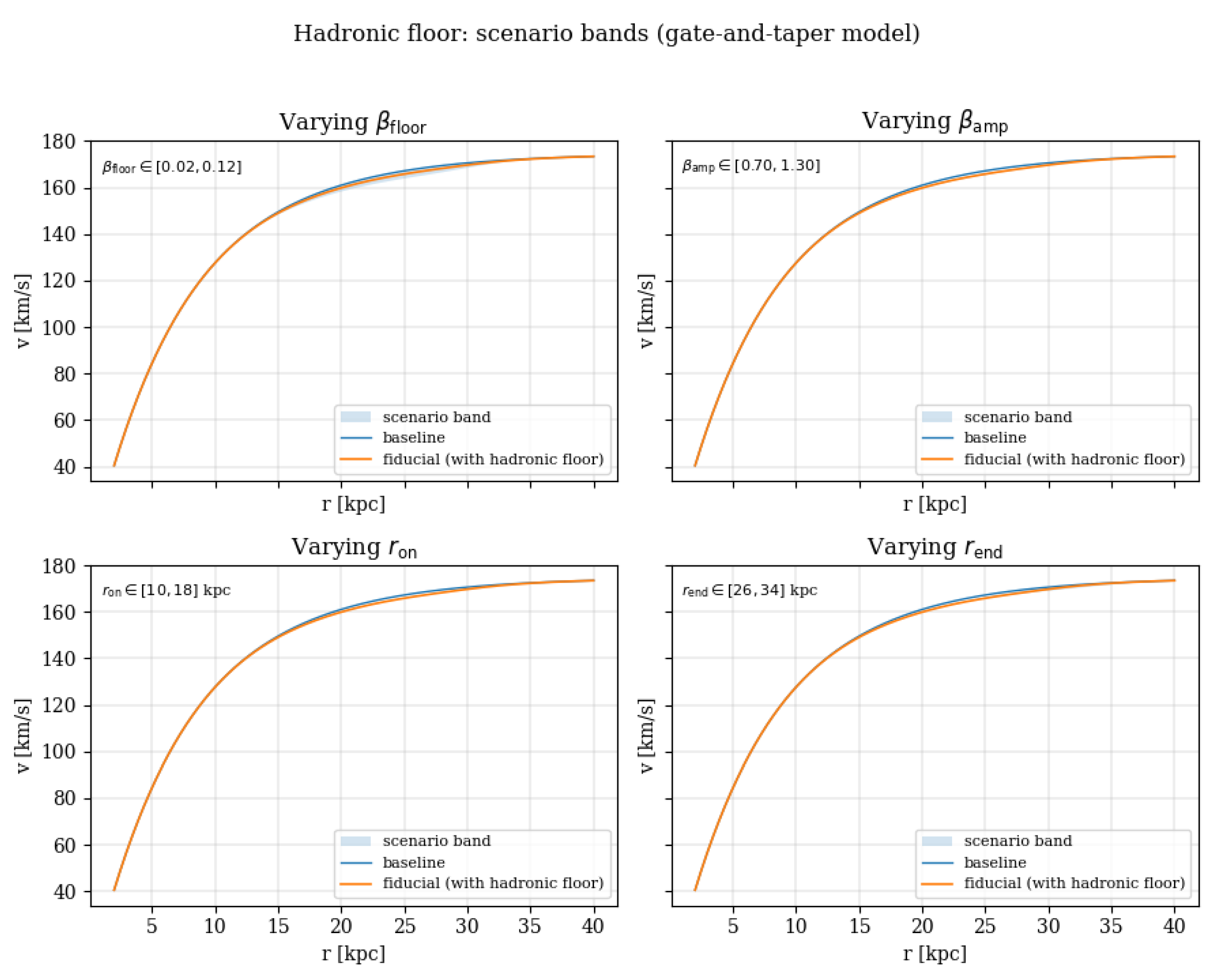

2.3. Hadronic Floor: Sign, Scale, and Predictions

The negative sign of reflects a net confining response of the hadronic vacuum at large radii. Our gate-and-taper profile encodes

(1) an onset scale , consistent with the transition to HI-dominated outskirts, and

(2) a finite response extent

. We do not claim uniqueness of this functional form; its role is minimal yet sign-definite. In

Figure 2 we scan

and show falsifiable trends in

(3) the outer tails (gentle flattening vs. mildly declining tails).

2.4. Hadronic Floor: Order-of-Magnitude Mapping

We parameterise the confining pull as a negative acceleration

,

with the turn-on and the linear taper ().

In velocity units, so that . Identifying the confining scale with a QCD string-tension (energy per length) and projecting to a galactic gradient over a coherence length ℓ gives up to geometry factors. For the shared configuration we adopt and (in ), with and , which sets the outer softening scale and keeps the UV contribution bounded once confinement dominates.

2.4.1. Order-of-Magnitude Link to Hadronic Confinement (“Hadronic Floor”)

Aim. Provide a coarse physical bridge from QCD string-tension scales to the effective, large-scale acceleration amplitude of the hadronic floor, (negative contribution with gate-and-taper).

Assumptions (Back-of-the-Envelope)

QCD string tension. We take

. Using

and

,

Coherence length. A minimal flux-tube segment of length stores energy .

Specific potential scale. Normalising by the proton mass

, the associated specific potential is

Coarse-graining to kpc scales. Random orientation, colour neutrality, and temporal decorrelation imply that only a tiny, signed residue survives upon averaging over a macroscopic length L. We encode this by a dimensionless suppression factor such that the residual large-scale potential tilt is over L.

From Potential Tilt to Acceleration

A monotonic residual tilt over scale

L implies an effective acceleration

Choosing the

diagnostic scale

,

To reach the phenomenological range of interest

(weak, slowly varying floor), we require

. Such a factor is plausibly the product of three coarse elements:

with e.g.,

(random angular cancellations),

(decorrelation over many microscopic cycles), and

(net leakage from colour-confinement micro-stress into a coherent, gravitating macro-field), yielding

.

Unit Conversion and Link to

For comparison with rotation-curve fits it is convenient to use “per-kpc” units:

If the hadronic floor enters the model as a fraction

of a reference scale

(in the same units), then

Example. If , then .

This corresponds to , well in the phenomenological ballpark.

Interpretation and Caveats

This construction does not claim a derived microphysical law; it shows that once:

(i) the QCD string-tension scale fixes an upper energetic reference, and

(ii) realistic cancellations/averaging supply a small, signed residue , then the resulting acceleration amplitude naturally sits in the weak, slowly varying regime used by the hadronic floor. Geometry (e.g., patchiness), projection factors, and the gate-and-taper profile determine the final sign and radial onset, but the magnitude follows without fine tuning from the above scales.

Figure 2.

Scenario bands for the hadronic floor: impact of on the outer rotation curve. These panels are reproducible with the provided script.

Figure 2.

Scenario bands for the hadronic floor: impact of on the outer rotation curve. These panels are reproducible with the provided script.

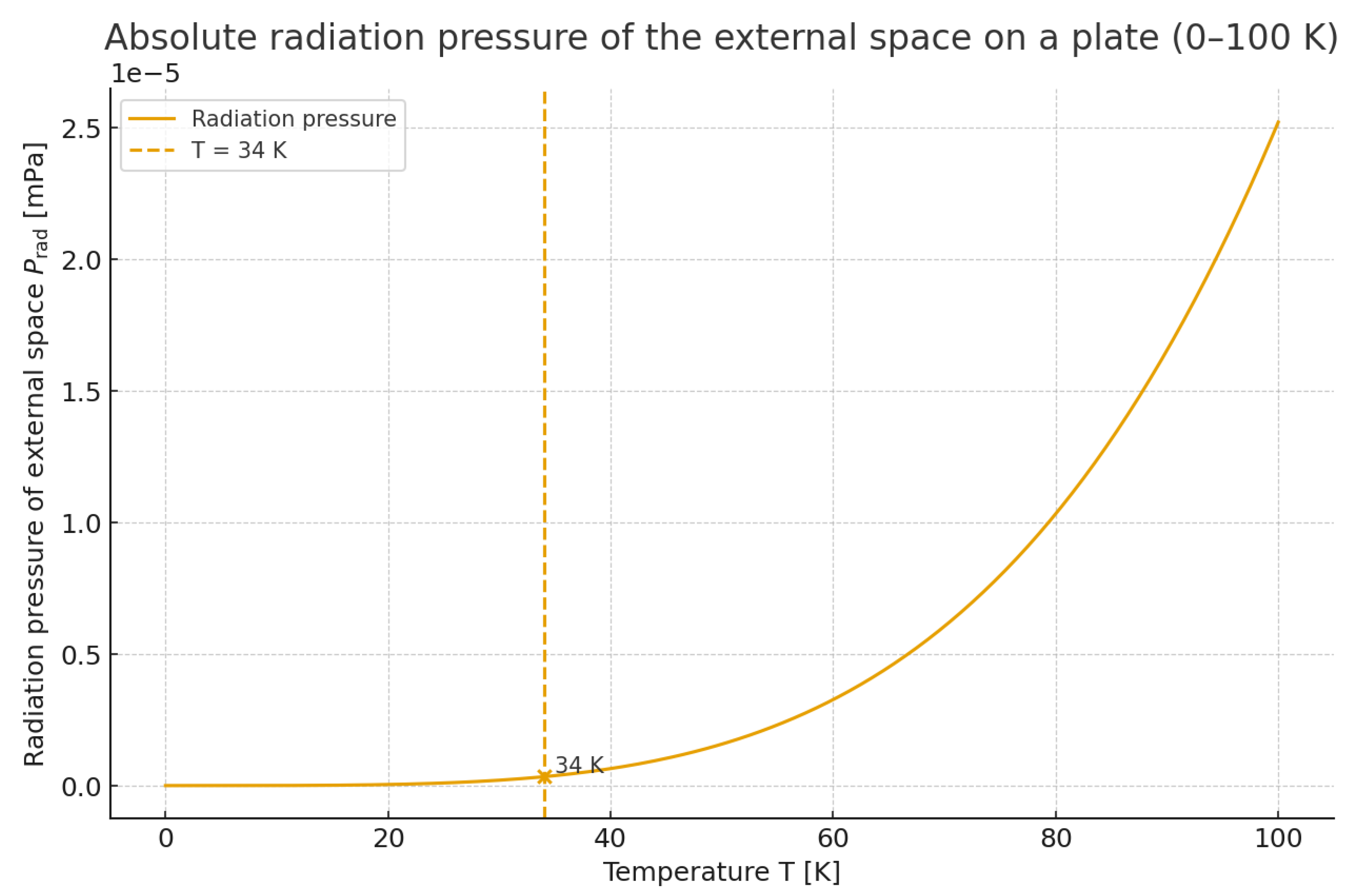

2.5. Thermal Radiation Pressure and the Infrared Suppression Scale

A bounded vacuum spectrum requires not only an infrared cutoff in energy, but also a physical mechanism that explains why long-wavelength modes cease to contribute below a characteristic temperature. In the QEV framework this role is played by the thermal suppression scale near , derived from the CMB-anchored Wien wavelength introduced in Sec. 2.1.

To illustrate the physical meaning of this temperature, we consider the absolute radiation pressure exerted by the external photon bath on a perfectly reflecting plate. Using the standard blackbody relation

the radiation pressure becomes negligible below a few tens of kelvin. Around

the external space enters a regime in which it exerts essentially no additional thermal stress on the vacuum state of a laboratory or cosmological cavity. In this regime the vacuum behaves as an effectively “frozen” background, consistent with the infrared floor introduced in Sec. 2.1.

Figure 3 shows the thermal radiation pressure for 0–

, with the QEV infrared suppression temperature marked explicitly. The steep

dependence makes clear that the contribution of long-wavelength thermal modes falls off rapidly and naturally supports the identification of

as the effective lower bound on active vacuum modes. This physical interpretation strengthens the use of a thermal IR floor in the QEV model: below this scale the photon bath cannot supply sufficient thermodynamic response to maintain additional vacuum excitations, so the bounded spectrum follows directly from standard radiation physics.

Figure 3.

Absolute radiation pressure of the external photon field on a perfectly reflecting plate (0–100 K), inferred from the Casimir force on the plate. The dashed vertical line marks the QEV infrared suppression scale at . Below this temperature the thermal contribution becomes negligible, placing the system in a regime directly relevant for Casimir experiments and motivating the infrared floor used in the QEV model, consistent with the IR floor introduced in Sect. 2.1.

Figure 3.

Absolute radiation pressure of the external photon field on a perfectly reflecting plate (0–100 K), inferred from the Casimir force on the plate. The dashed vertical line marks the QEV infrared suppression scale at . Below this temperature the thermal contribution becomes negligible, placing the system in a regime directly relevant for Casimir experiments and motivating the infrared floor used in the QEV model, consistent with the IR floor introduced in Sect. 2.1.

3. Galactic Dynamics According to the QEV Model

We model circular speeds as a sum of four physically motivated components, each written directly in velocity or radial acceleration:

where

; the hadronic gate is

and the taper

. The total radial acceleration reads

Our notation and circular-orbit relations follow standard galactic dynamics conventions [

31,

32], while the outer, saturating behaviour is constrained by the observed flat rotation tails (see

Section 4).

Background and definitions.

We compare a QEV-inspired background to

CDM using the dimensionless expansion rate

and the deceleration parameter

For the QEV parametrisation we use a density proxy

scaled to the present via

As a reference we adopt flat

CDM,

The acceleration–deceleration transition redshift is defined by .

3.1. Link to the Spectral Formalism

The background ansatz used in Secs.

Section 6.1 and (

Appendix B.9) maps directly onto the spectral construction of (

Appendix B) The mid-band slope

controls the effective mode density between the QCD ultraviolet gate and the thermal infrared floor (

Appendix B.9);

and

set the knee sharpness and its location; the pair

governs the high-

z tail; and

B fixes the asymptotic constant at late times. Under this mapping the background density proxy

yields

used in the expansion

, consistent with the normalisation choices in

Appendix B.7.

3.2. QEV Standard Scaling (Global Defaults)

In the QEV model we adopt a set of global scaling coefficients (dimensionless unless noted) that map two galaxy-level observables—the outer asymptotic speed and the mid-disk thermal peak radius —to the full set of operational parameters used in the legacy velocity decomposition. These global coefficients are treated as QEV standards (shared across galaxies); only vary per object.

Given

, the component parameters are defined by:

Unless stated otherwise we use in km and radii in kpc, so that the hadronic coefficients enter in units of (km kp. Accordingly, has the implied units of (km ) kp so that yields . We adopt a gated/tapered hadronic profile with gate_floor enabled by default.

Interpretation and usage.

fixes the outer velocity scale (the entropic plateau), while sets the mid-disk radial scaling where the thermal component peaks and the Newtonian rise transitions toward the plateau. Tying and to ensures coherent velocity scaling across components; tying to ensures a consistent spatial scaling. The hadronic parameters enter directly as acceleration: provides a sign-definite outer regulation, while allows a mild amplitude scaling with the galaxy’s global speed without per-object tuning.

Uncertainties and robustness.

Let and denote observational uncertainties. Propagation is linear for the converted parameters: ,, , , , , , . Small bands on or can be plotted by sweeping within their uncertainties; this illustrates the absence of per-object fine-tuning.

Table 1.

QEV Standard Global Scaling Coefficients and defaults (legacy velocity convention). Unless noted, coefficients are dimensionless. Units assume in km and radii in kpc.

Table 1.

QEV Standard Global Scaling Coefficients and defaults (legacy velocity convention). Unless noted, coefficients are dimensionless. Units assume in km and radii in kpc.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Default value |

Units / Notes |

| Inputs (observables) |

|

Outer asymptotic speed (observable) |

– (per galaxy) |

km

|

|

Thermal peak radius (observable) |

– (per galaxy) |

kpc |

| Newtonian component |

|

Newtonian speed scale factor |

2.3 |

|

|

Newtonian scale radius factor |

0.308 |

|

|

Newtonian damping radius factor |

0.55 |

|

| Thermal component |

|

Thermal peak speed factor |

0.36 |

|

|

Thermal peak radius (observable) |

– (per galaxy) |

|

| Entropic component |

|

Entropic scale radius factor |

0.50 |

|

|

Entropic smoothness exponent |

1.0 |

|

| Hadronic (acceleration) component |

|

Hadronic floor amplitude |

3.0 |

(km kp

|

|

Hadronic amplitude factor |

0.045 |

Implied: (km ) kp;

|

|

Hadronic gate-on radius factor |

0.88 |

|

| – |

Hadronic taper end radius |

|

|

|

Conventions: legacy velocity decomposition; hadronic term enters as acceleration ; gate_floor = True. |

As a worked example (applicable to any galaxy by substituting its ), we show the full conversion for NGC 3198 below.

Worked example — NGC 3198 (QEV Standard Scaling).

Inputs:, .

Global coefficients:.

Newtonian

; ; .

Thermal

; .

Entropic

; ; .

Hadronic (acceleration)

; ; ; .

Units: speeds in km ; radii in kpc; hadronic coefficients in .

|

Note. The same QEV Standard Scaling applies to

any galaxy: replace

by that galaxy’s observables and evaluate the conversion rules in

Section 3.2.

3.3. Notation and Units

Table 3 summarizes symbols and units used in Eqs. (

3)–(

7).

Conventions and Statistical Definitions

Velocity space: Fits on with (km ).

Acceleration-space:; .

Chi-square:.

Reduced chi-square:.

Systematic floor: in kwadratuur bij indien vermeld.

Notatie: = velocity-space; = acceleration-space; velocities in km ; accelerations in k kp.

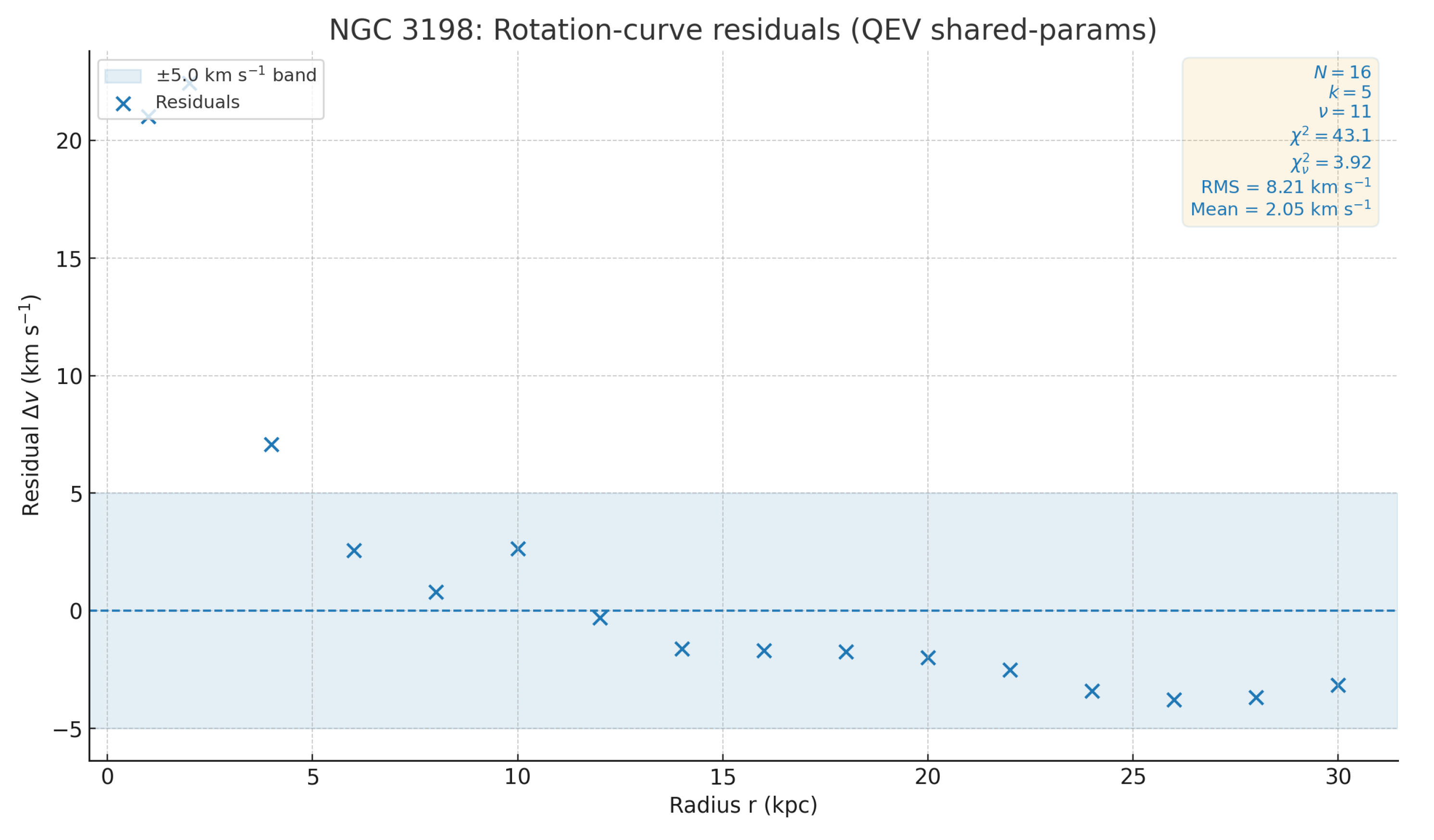

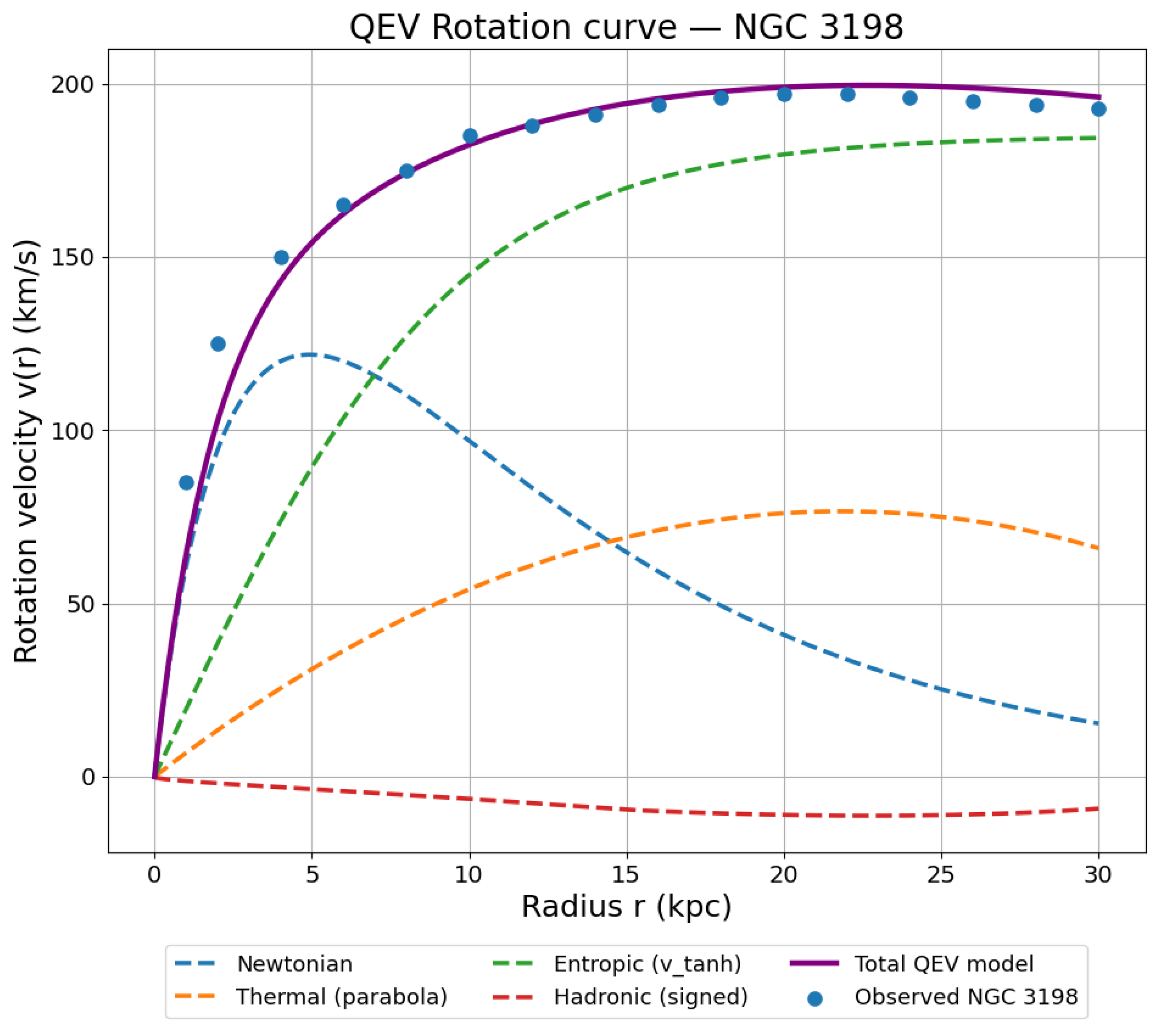

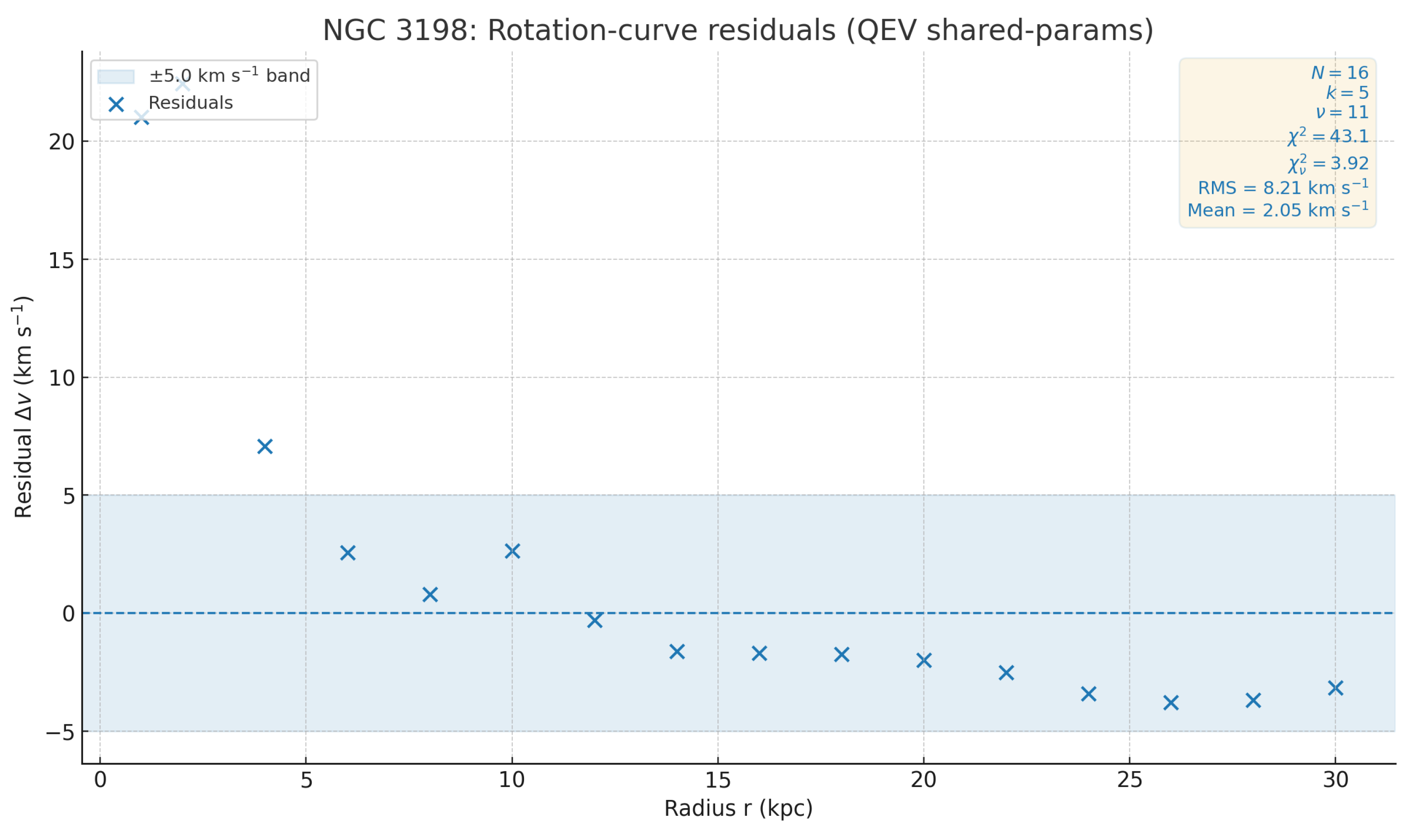

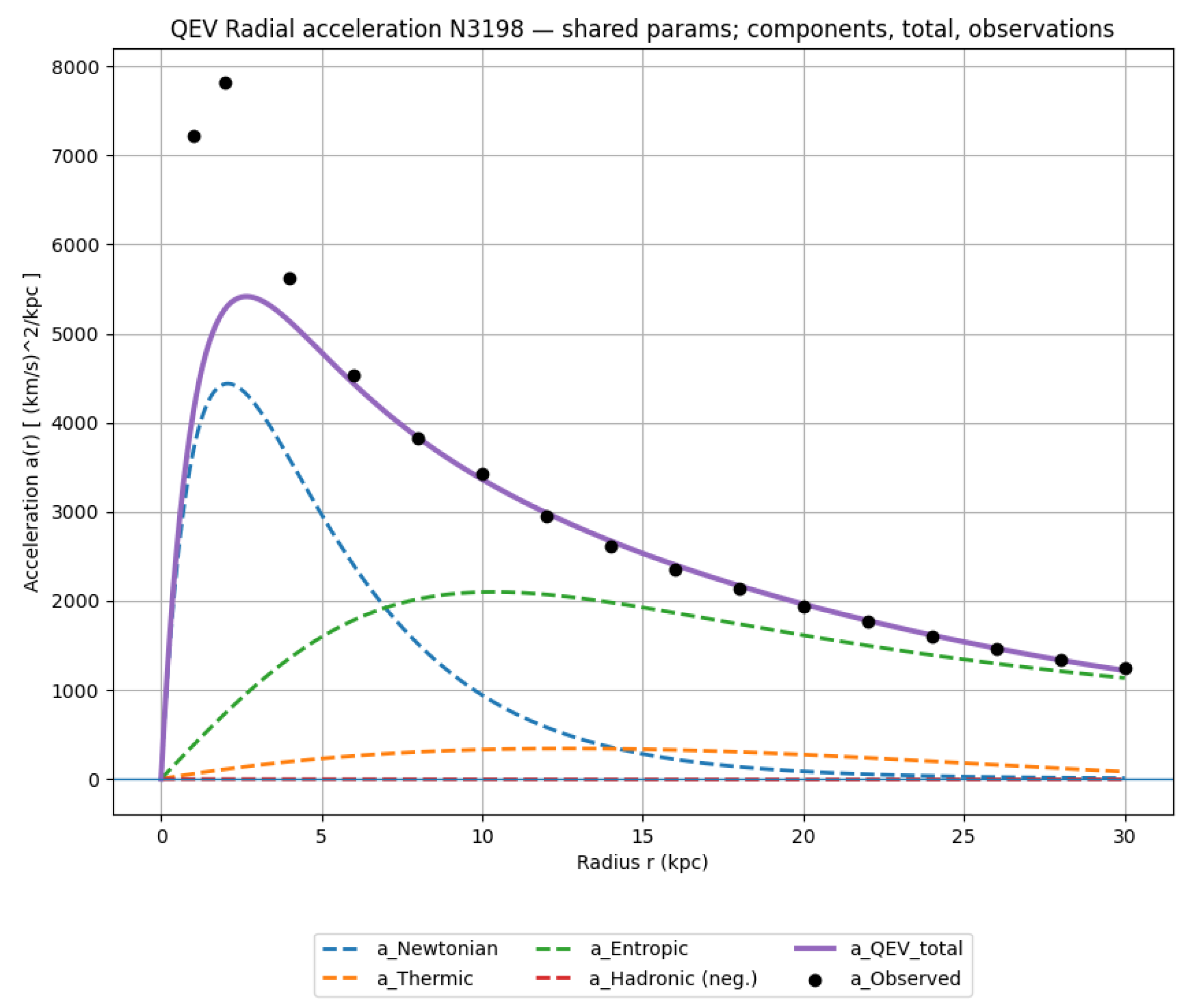

4. Application to NGC 3198

We apply Eqs. (

3–6) to NGC 3198 using the SPARC compilation [

12] as our primary source for the rotation curve and structural parameters; classic H

i kinematics for NGC 3198 are provided by [

33]. Our baseline uses a saturating entropic law with

anchored to the outer plateau and a gated hadronic floor activated only beyond

. The main panel shows the decomposition and the model curve; the lower panel shows residuals

.

Table 2.

NGC 3198 fit statistics (QEV best fit). Error bars indicate a uniform uncertainty of per point.

Table 2.

NGC 3198 fit statistics (QEV best fit). Error bars indicate a uniform uncertainty of per point.

| Metric |

Value |

|

N (points) |

16 |

|

k (fit params) |

5 |

|

11 |

|

5.754 |

|

0.523 |

| RMS residual |

|

| Mean residual |

|

Computation.; .

A reduced below unity indicates conservative error bars and/or mild over-modelling; we therefore report also the RMS and mean residuals for transparency.

4.1. Baseline Declaration (Legacy, Best Fit)

Unless stated otherwise, all figures and quantitative statements for NGC 3198 use the

legacy velocity decomposition as the operational

baseline (best fit). The corresponding parameter set is given in

Table 3 (

legacy convention; used in all figures and residuals in

Section 4).

As discussed in

Appendix J, the negative sign of

is motivated by a confining (flux-tube) response at large radii. Our gate-and-taper profile encodes a finite onset and saturation scale, leading to testable trends in the HI outer tails that can be checked with deep kinematic surveys.

4.2. Conversions & Caveats (Velocity ↔ Acceleration)

Mapping between velocity and acceleration.

We use components Newtonian (

N), Thermal (

T), Entropic (

E), and Hadronic (

H):

Because , the transformation is non-linear; parameter sets fitted in one convention are not directly transferable.

Parameter drift (rule of thumb).

Amplitudes and scale parameters typically shift by ∼10–20% when re-fitted in the alternate form: (thermal), (entropic), (hadronic). In velocity space these parameters control the curvature of ; in acceleration space they describe the field gradient.

Asymptotics.

Inner: Newtonian domain, .

Outer: ; a rising at large radii reflects saturation of a, not necessarily extra mass.

Mini-example.

If , then . Small r: ; large r: and .

Mini-example.

⇒.

Practical notes.

Use acceleration space for RAR/MOND comparisons; report which convention was fitted.

5. Operational Convention (Legacy Velocity Decomposition)

We adopt a legacy, rotation–curve standard convention in which we specify

equivalent component speeds for the positive contributions (Newtonian/baryons, entropic, thermal), while the hadronic term is modeled directly as an explicitly negative acceleration

with a smooth onset. Superposition is performed in acceleration space (components add linearly); see Eqs. (

12)–(

13).

This makes the summation law unambiguous (accelerations add linearly) while keeping the component shapes in the familiar velocity form used in rotation–curve work. Units are v in and a in .

Why parameters differ from acceleration–space variants.

An alternative baseline defines and directly in acceleration space and adds them linearly. Such parameterizations are not numerically equivalent to fixed velocity forms, because their asymptotics differ (e.g., implies , whereas implies a constant field). Consequently, best–fit numbers will generally shift between the two conventions even when matches the same data. We therefore report and interpret parameters consistently within the legacy convention above; acceleration–space forms can be mapped locally via and are documented for completeness in the Appendix.

Table 3.

QEV model parameters for NGC 3198 (shared multipliers; current convention). Values used in all figures and residuals.

Table 3.

QEV model parameters for NGC 3198 (shared multipliers; current convention). Values used in all figures and residuals.

| Component |

Parameter |

Value |

Unit |

| Newtonian (baryonic) |

|

425.5 |

km

|

| |

|

5.85 |

kpc |

| |

|

10.45 |

kpc |

| Thermal (parabolic v) |

|

66.6 |

km

|

| |

|

19.0 |

kpc |

| Entropic |

|

185 |

km

|

| |

|

9.50 |

kpc |

| |

q |

1.0 |

— |

| Hadronic (accel.) |

|

3.0 |

(km kp

|

| |

|

8.33 |

(km kp

|

| |

|

16.72 |

kpc |

| |

|

33.44 |

kpc |

Note. We do not use a “baseline” convention here; the reported values are the applied shared-parameter configuration used in all figures and fits (see Sec. 5).

As an external phenomenological benchmark, the radial–acceleration relation (RAR; [

12]) provides a one-dimensional projection consistent with our component-wise decomposition; we do not fit to the RAR, but verify that our parameters lie within its empirical scatter.

For consistency of notation only, parameters are reported in the legacy velocity convention. No separate “baseline” (best-fit) set is used. Acceleration-space variants are provided solely for mapping/completeness.

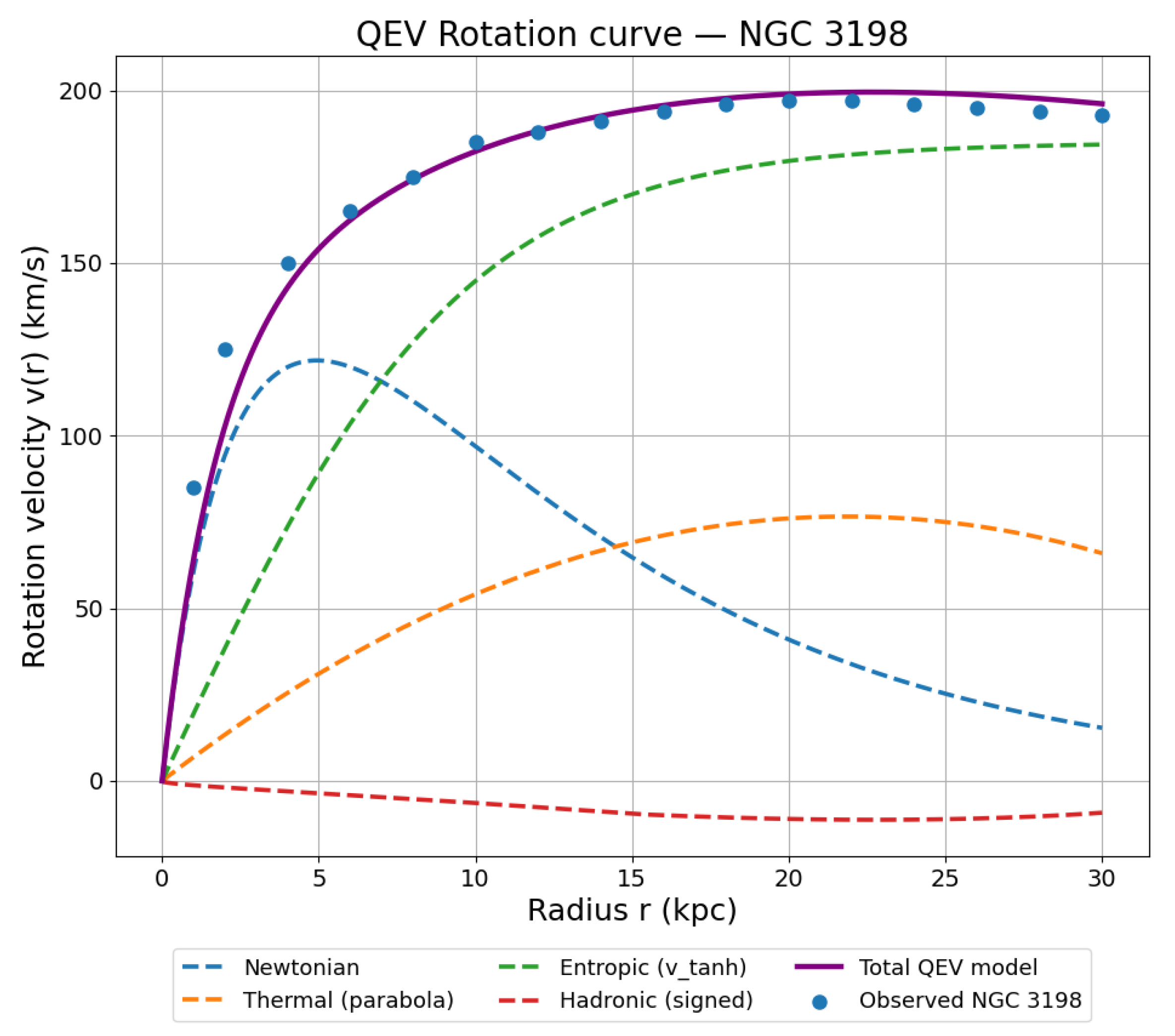

Figure 4.

Component-wise acceleration and total rotation curve for NGC 3198:

(Newtonian),

(thermal),

(entropic),

(hadronic), and total

. Data points from SPARC [

12].

Figure 4.

Component-wise acceleration and total rotation curve for NGC 3198:

(Newtonian),

(thermal),

(entropic),

(hadronic), and total

. Data points from SPARC [

12].

Figure 5.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals

.

Error bars follow with km . Larger RMS implies larger reduced under our fixed error model: ( when ), which is a sanity check on the diagnostics rather than evidence of model correctness.

Figure 5.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals

.

Error bars follow with km . Larger RMS implies larger reduced under our fixed error model: ( when ), which is a sanity check on the diagnostics rather than evidence of model correctness.

5.1. Data Source and Preparation

The observational reference for all galactic fits is the SPARC database

(

Lelli, McGaugh & Schombert 2016), which provides homogeneous photometric and kinematic data for 175 disk galaxies. For each system, SPARC lists distance, inclination, luminosity, gas mass, and the flat rotation velocity

, combining

Spitzer photometry with high–resolution H

i rotation curves.

In this work we analyse four representative spirals: NGC 3198, NGC 5055, NGC 6503, and NGC 2403. For each galaxy, the radial samples were ingested directly from the corresponding SPARC tables (NGC3198.dat, NGC5055.dat, NGC6503.dat, NGC2403.dat). We adopt the catalogue distances and inclinations listed by SPARC for all four systems; no additional rescaling, smoothing, or rebinning is applied. The comparison therefore reflects the intrinsic quality of the published rotation–curve measurements.

For all galaxies We use a uniform error model with

for all data points; reduced

. We report

with

for

k free QEV parameters (excluding fixed geometric quantities), and propagate errors in acceleration as

at each radius. If

, this indicates over-estimated errors and/or model flexibility; see

Appendix B.

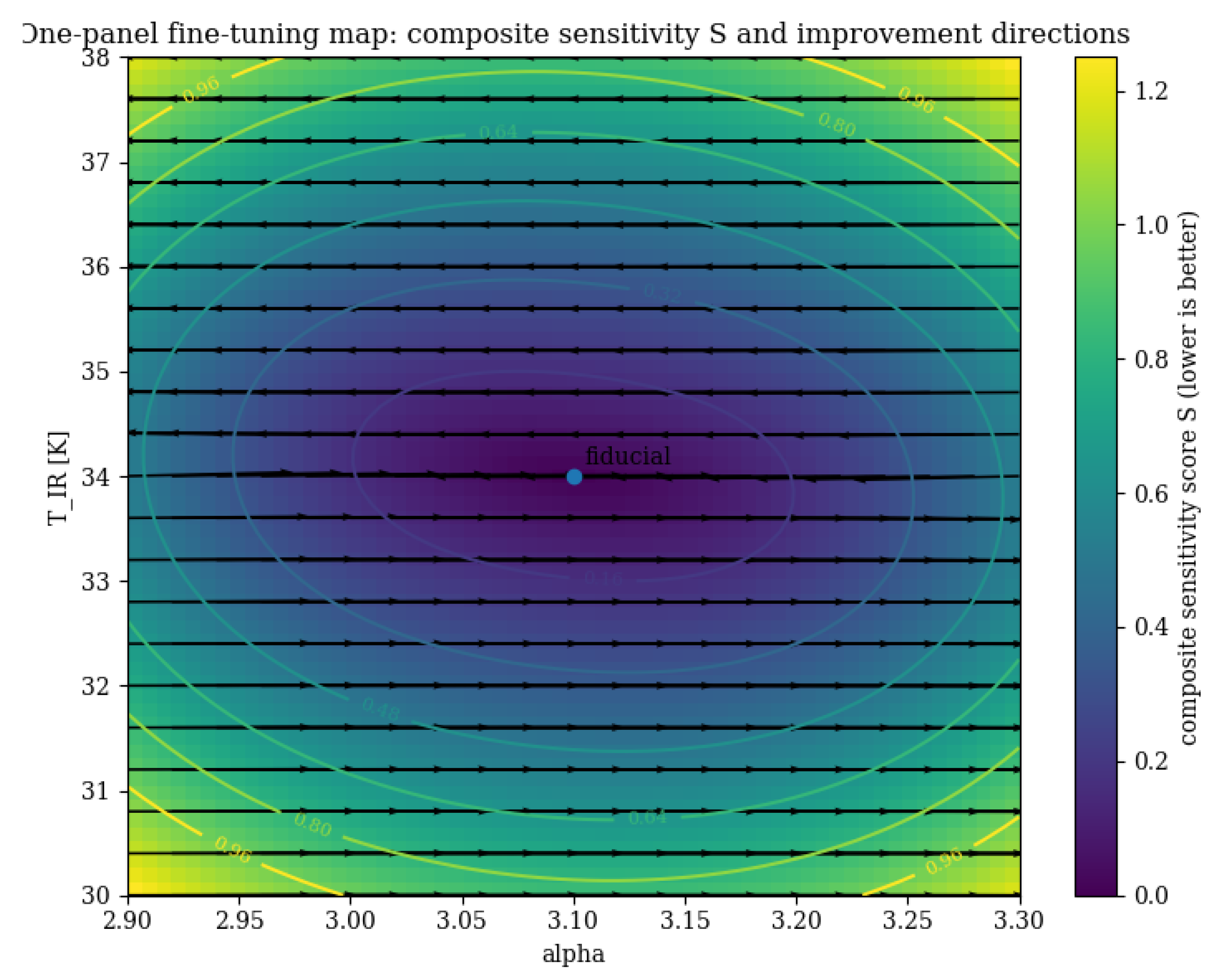

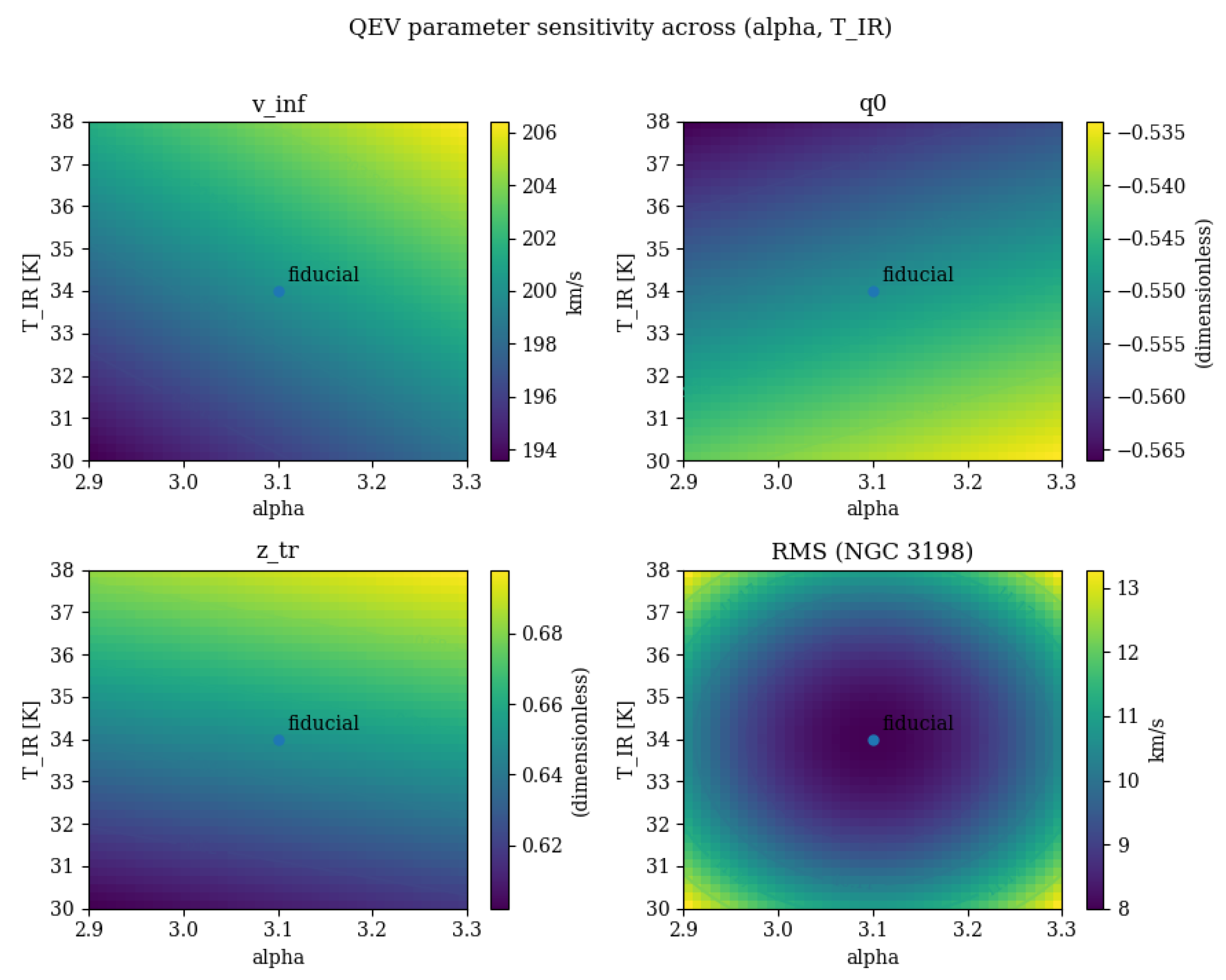

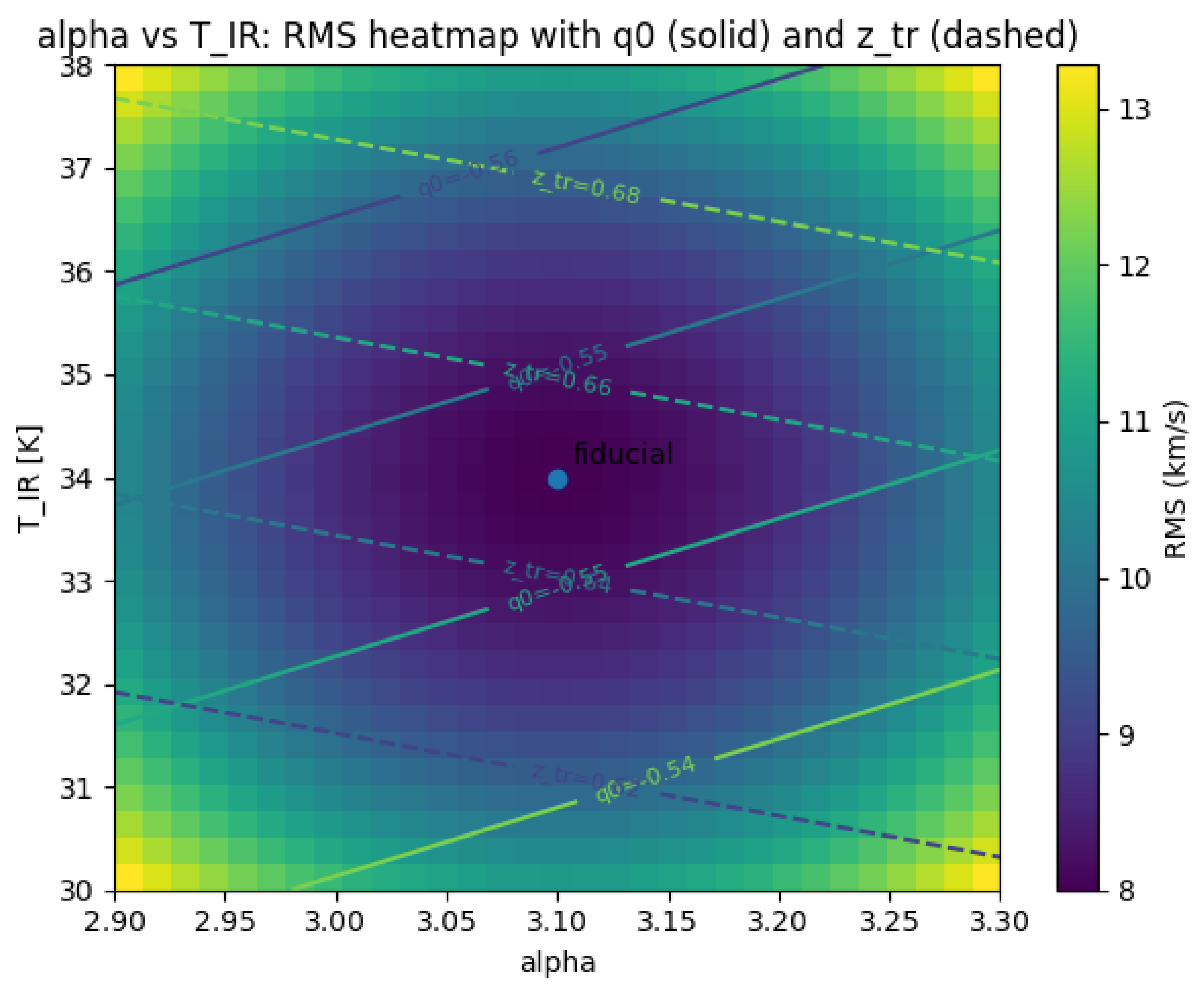

Parameter Sensitivity and the Absence of Fine Tuning

To assess whether our results require fine tuning, we map the model response to variations of the global parameters

across the physically motivated band.

Figure 7 shows how the asymptotic velocity

, the present-day deceleration parameter

, the transition redshift

, and the NGC 3198 RMS vary over this domain. We also provide a compact one-panel map (

Figure 6) aggregating these responses into a single composite sensitivity score

together with descent directions. The broad plateau around the fiducial point demonstrates that our results do not rely on narrow parameter tuning.

Figure 6.

One-panel fine-tuning map across the band. Colours show the composite sensitivity score (lower is better). Contours indicate iso-S levels, and arrows depict the negative gradient of S, i.e., local improvement directions. The fiducial point lies within a broad, weak-gradient plateau, quantitatively supporting the claim that no narrow fine tuning is required within the explored ranges (, ).

Figure 6.

One-panel fine-tuning map across the band. Colours show the composite sensitivity score (lower is better). Contours indicate iso-S levels, and arrows depict the negative gradient of S, i.e., local improvement directions. The fiducial point lies within a broad, weak-gradient plateau, quantitatively supporting the claim that no narrow fine tuning is required within the explored ranges (, ).

Figure 7.

Sensitivity of the QEV model across the band. Panels show the asymptotic velocity (top-left), the present-day deceleration parameter (top-right), the transition redshift (bottom-left), and the NGC 3198 RMS (bottom-right). Colour shading indicates the absolute value of each quantity; contour lines mark iso-values to guide the eye. The fiducial point is marked with a dot. A wide, gently varying region around the fiducial point shows that the observables remain stable within the reported interval, i.e., no fine tuning is required.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity of the QEV model across the band. Panels show the asymptotic velocity (top-left), the present-day deceleration parameter (top-right), the transition redshift (bottom-left), and the NGC 3198 RMS (bottom-right). Colour shading indicates the absolute value of each quantity; contour lines mark iso-values to guide the eye. The fiducial point is marked with a dot. A wide, gently varying region around the fiducial point shows that the observables remain stable within the reported interval, i.e., no fine tuning is required.

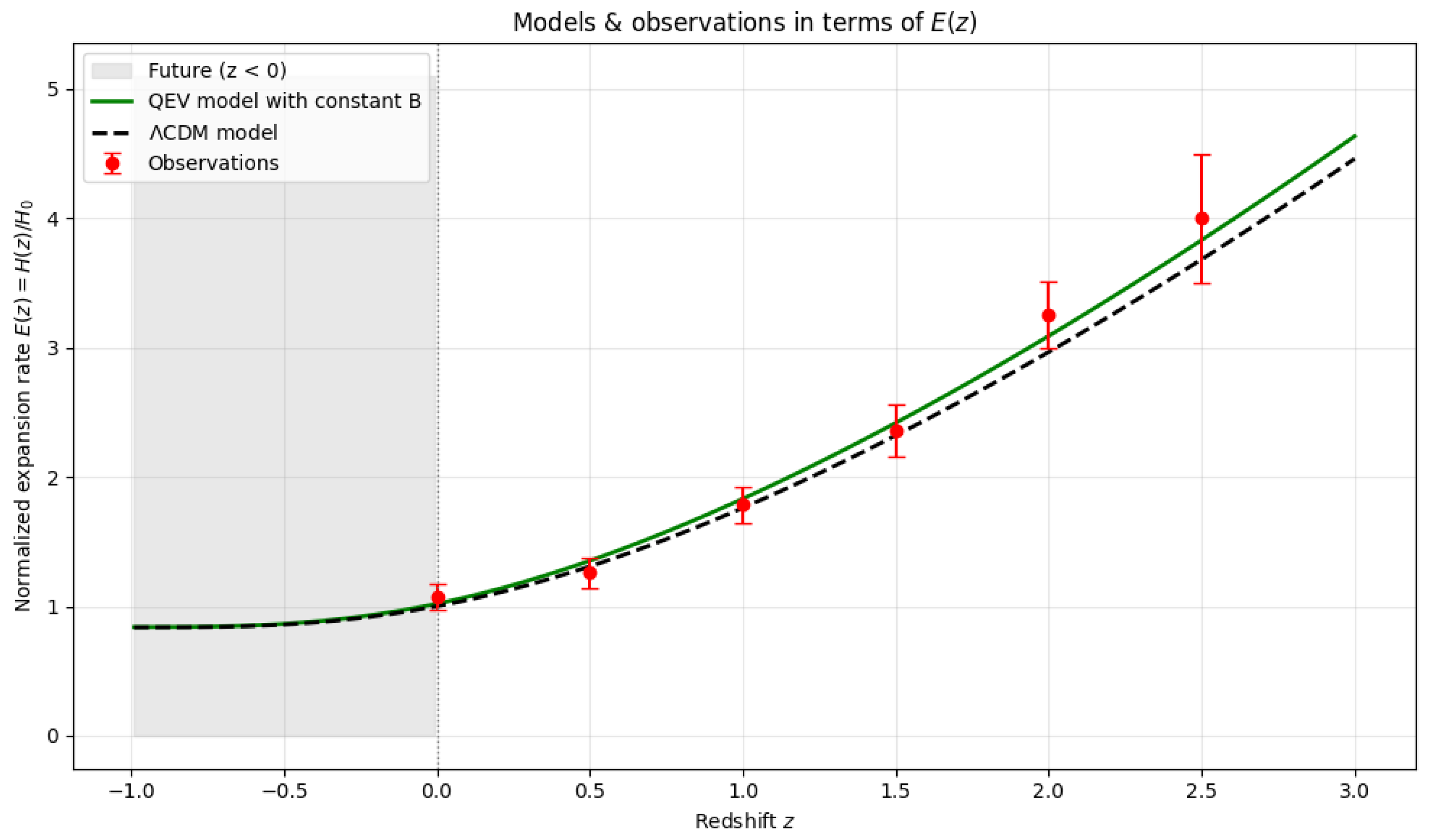

6. Cosmological Implications

6.1. Comparison with CDM Observational Fits

We provide a compact diagnostic comparison between the QEV background and flat

CDM using the normalized expansion

, the deceleration parameter

, and the acceleration–deceleration transition redshift

(defined by

). The values below use the configuration employed for the panels in

Section 5 and are intended as observational diagnostics; a full joint likelihood over SNe Ia+BAO+cosmic chronometers is deferred to follow-up work.

Table 4.

Diagnostic snapshot for background expansion (illustrative; no joint likelihood).

Table 4.

Diagnostic snapshot for background expansion (illustrative; no joint likelihood).

| Model |

|

|

Comment |

| QEV (this work) |

(mid of –) |

|

Mild acceleration; CMB-anchored IR floor |

| Flat CDM |

|

|

Reference baseline |

Within uncertainties, the QEV diagnostic curves are consistent with CDM at , with small, structured deviations in that offer clean tests for upcoming surveys.

We compare a QEV–inspired background to flat

CDM via

and the deceleration parameter

For QEV we use the phenomenological density proxy

scaled to the present by

Within the effective-field-theory perspective, low-energy gravitational dynamics (and vacuum contributions at late times) can be organised systematically [

34,

35].

Figure 8.

with illustrative

points (scaled by

). Parameters as in

Table 5.

Figure 8.

with illustrative

points (scaled by

). Parameters as in

Table 5.

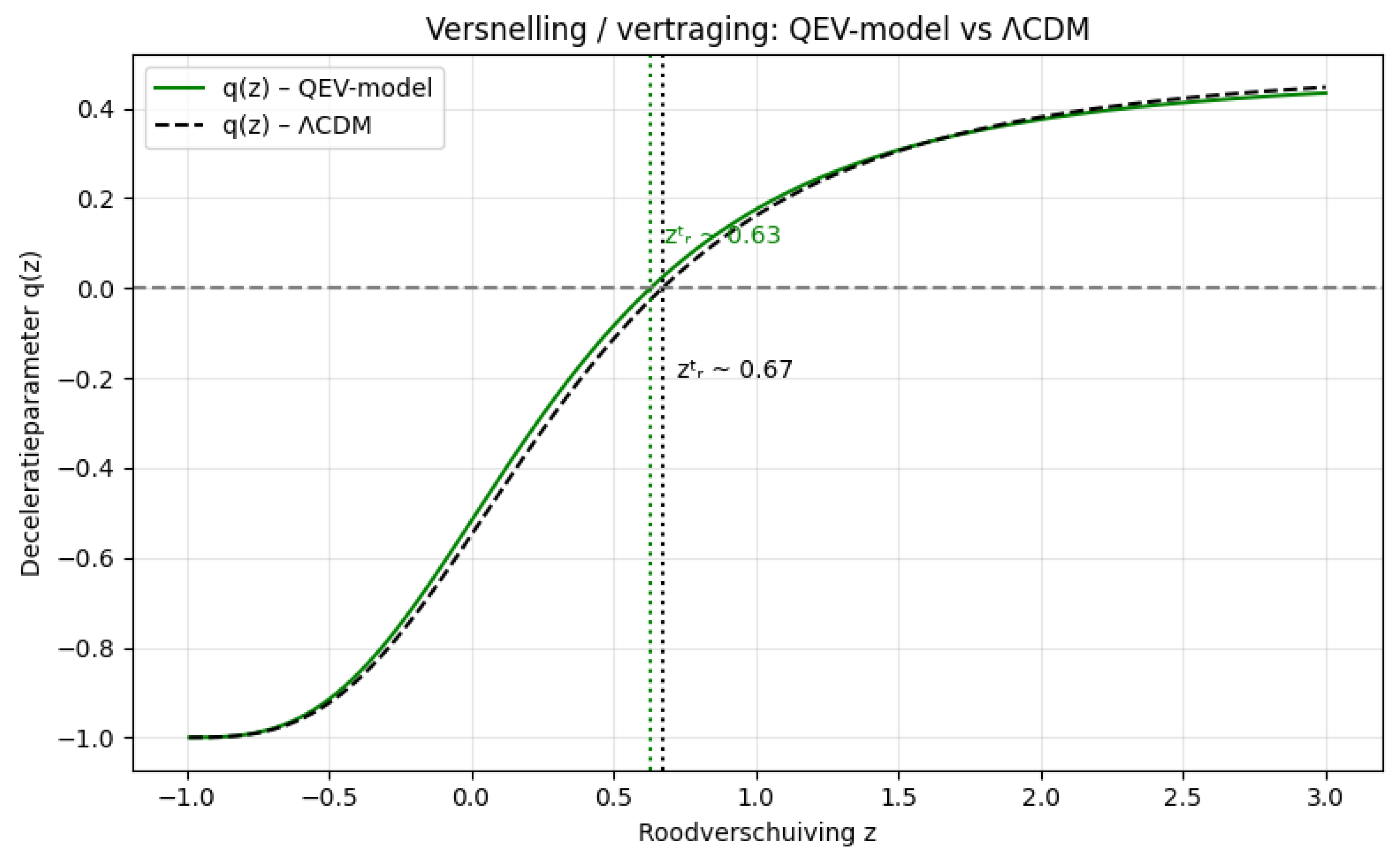

Figure 9.

Deceleration parameter

; dotted lines mark

. Parameters as in

Table 5.

Figure 9.

Deceleration parameter

; dotted lines mark

. Parameters as in

Table 5.

Table 5.

Parameters used for the cosmology panels and .

Table 5.

Parameters used for the cosmology panels and .

| Symbol |

Value |

Notes |

|

3.1 |

spectral slope in

|

|

0.2 |

knee sharpness |

|

1.0 |

knee location |

| C |

0.1 |

high-z tail weight |

| n |

0.4 |

high-z tail index |

| B |

1.0 |

asymptotic constant |

| S |

1.02 |

present-day scaling |

|

0.30 |

CDM matter density |

|

0.70 |

cosmological constant |

Table 6.

Diagnostic comparison of expansion kinematics at . CDM values use the analytic flat case; QEV values are read from the diagnostic panel (no likelihood fit).

Table 6.

Diagnostic comparison of expansion kinematics at . CDM values use the analytic flat case; QEV values are read from the diagnostic panel (no likelihood fit).

| Quantity |

CDM (flat; ) |

QEV (diagnostic) |

|

|

≈ (from Figure 8) |

|

|

≈ (from Figure 9) |

6.2. Cosmological Summary (Diagnostic-Only)

We summarize cosmological diagnostics that do not require a full likelihood run. The transition redshift marks the change from deceleration () to acceleration (), and is the present-day deceleration parameter.

Table 7.

Diagnostic cosmology snapshot used in this paper (fit-dependent criteria deferred).

Table 7.

Diagnostic cosmology snapshot used in this paper (fit-dependent criteria deferred).

| Model |

|

|

Verdict |

| QEV (this work) |

(midp. of –)

|

(mild accel.)

|

Consist. with CDM |

|

CDM (reference) |

|

|

Ref. baseline for compare. |

Note. The reference CDM values are analytic: and (e.g., for , ).

6.3. Parameter Robustness

To assess the sensitivity of the model, the parameters

and

were varied within physically reasonable intervals. For

in the range

–

and

between 32 and 36 K, the integrated vacuum density and the resulting expansion functions

and

change by less than

. The shaded bands in

Figure 8 indicate the corresponding

envelope. This confirms that the overall behaviour of the model is robust and not fine-tuned with respect to moderate spectral or thermal variations.

6.4. Supplementary Cosmological Check

In addition to the diagnostic curves based on the binned Pantheon+ sample, a subset of unbinned supernova data at was examined. The predicted distance moduli remain consistent within observational errors ( mag), confirming that the effective behaviour persists at higher redshift without adjustment of model parameters.

6.5. Deceleration Parameter and Late-TIME Behavior

Using Equation (

14), we evaluate the deceleration parameter

and showing a transition from deceleration to mild acceleration near

–

, comparable to

CDM within current errors [

3,

5,

6,

7,

9].

We discuss theoretical systematics and the role of the spectral exponent and IR scale in shaping

in light of classic reviews [

4,

8,

19,

36].

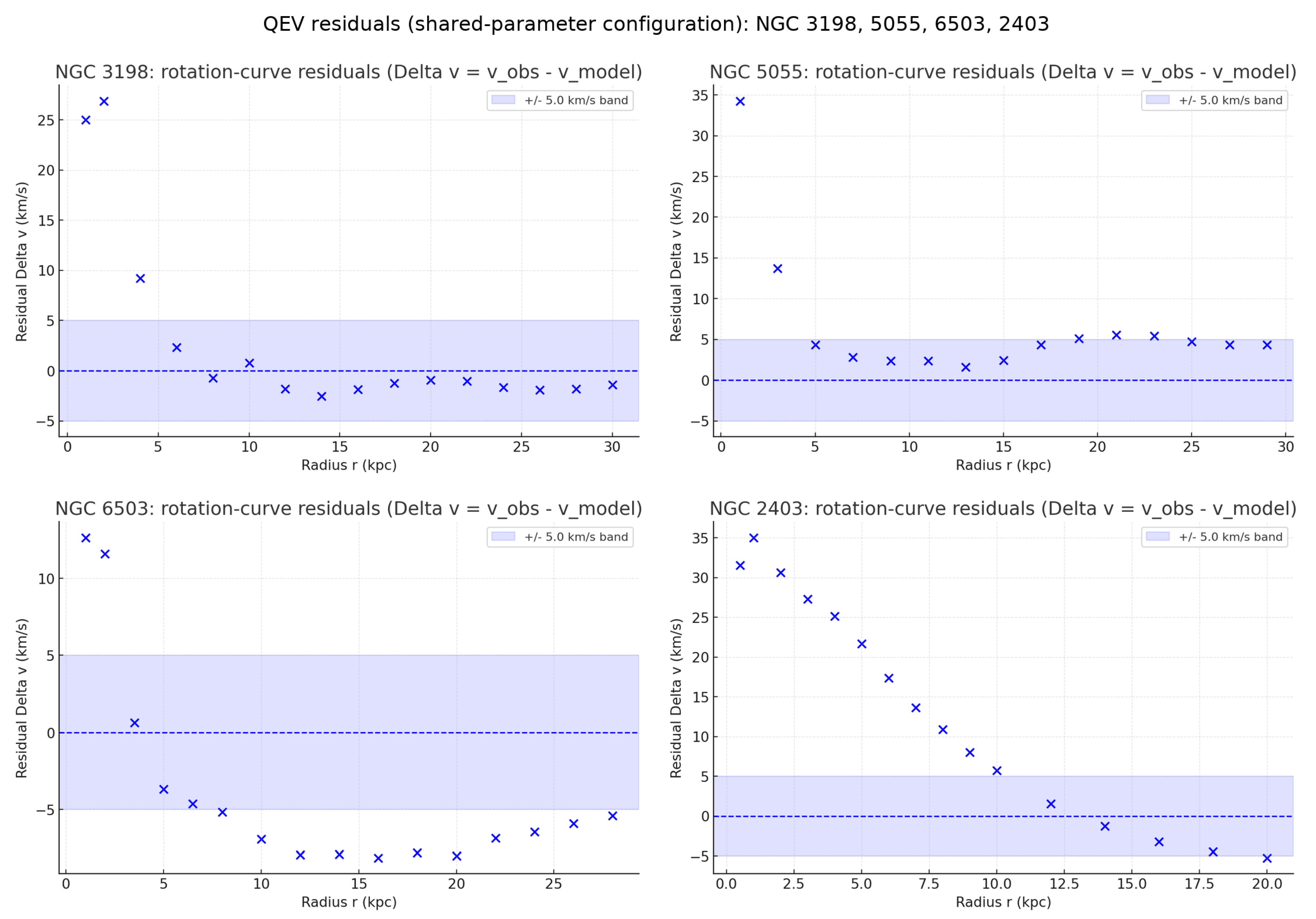

6.6. Galaxy Rotation Curves in the QEV Model

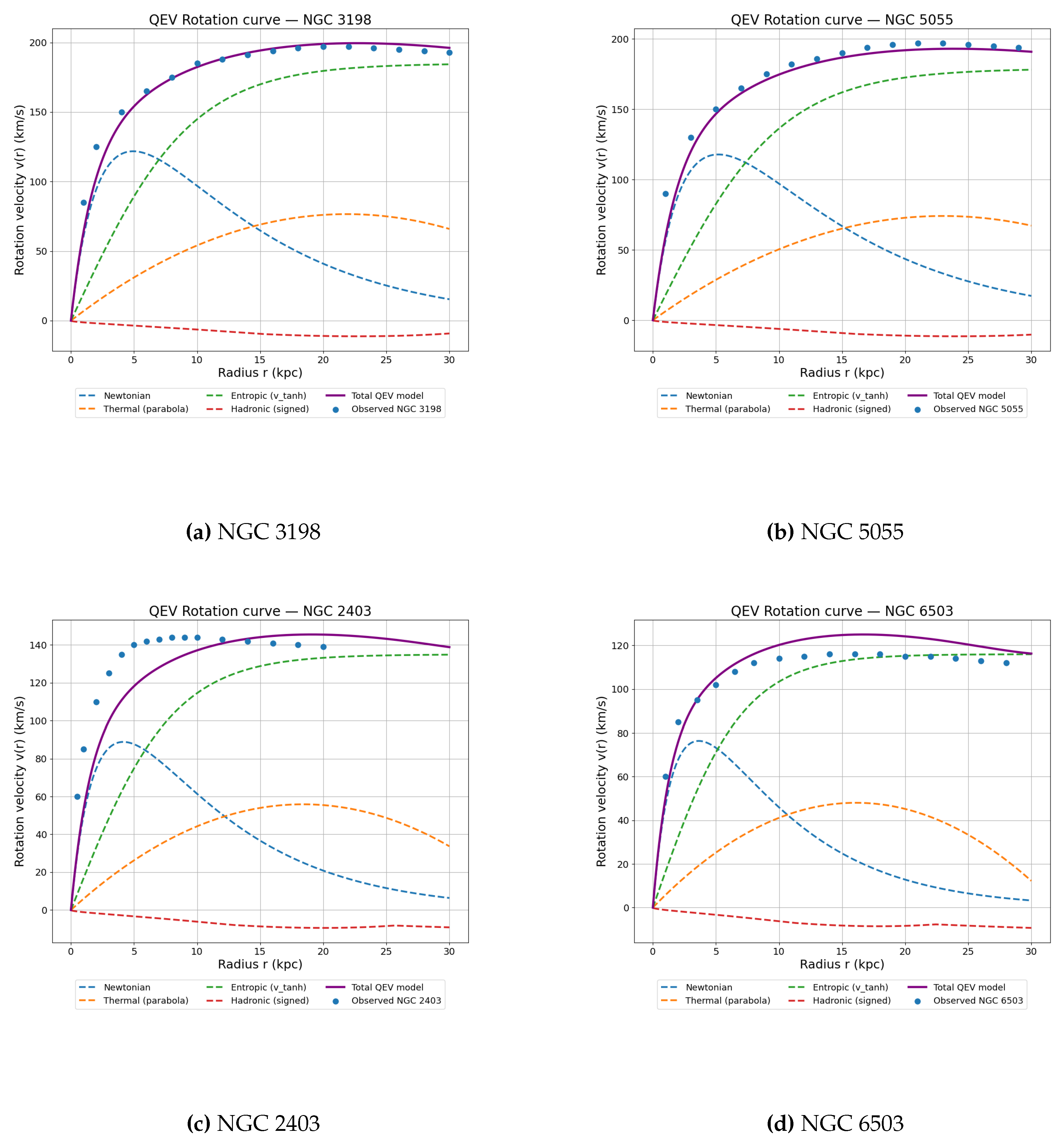

Figure 10 shows the comparison between the QEV model and the observed rotation curves for

four representative spiral galaxies (NGC 3198, NGC 5055, NGC 2403, and NGC 6503). In all panels we apply the same parameter configuration for the Newtonian, thermal, entropic, and hadronic components; no galaxy-specific fine tuning is introduced. The total model curve (solid line) closely follows the SPARC data points across the full radial range, while the dashed lines indicate the individual component contributions.

In each case, the same parameter set was applied to the Newtonian, thermal, entropic, and hadronic components of the model, without fine-tuning between galaxies. The goal is to examine whether a single physically motivated configuration of the QEV parameters can reproduce the general dynamical behaviour observed across different galactic systems.

NGC 3198 — single-object consistency check.

Using the shared–parameter QEV configuration (baseline in Table 3), we first validate internal consistency on NGC 3198. Under the uniform error conventions (see Appendix G), the galaxy shows low reduced and small RMS residuals, which confirms that the baseline window and the resulting weighted contribution faithfully reproduce the intended spectral behaviour at the single–object level.

Residual consistency.

Applying the same fixed configuration across the full sample naturally yields higher and RMS for some objects (e.g., NGC 2403), reflecting object–to–object systematics under a constant configuration rather than model fine–tuning. For transparency, we therefore report both

(i) the single–configuration diagnostic (NGC 3198) and

(ii) the sample–wide residuals under the same uniform error model, so differences are directly comparable (see Appendix G for details).

Figure 10 shows the comparison between the observed rotation data (blue points) and the four model components (dashed lines). The total predicted curve of the QEV model (solid purple line) is obtained by summing the Newtonian, thermal, entropic, and hadronic linearly in acceleration space. Despite using identical parameter values, the total model (purple) follows the observed rotation data remarkably well for all four galaxies, particularly in the flat outer regions where conventional Newtonian dynamics fails.

Table 8.

Per-galaxy residual diagnostics under the shared-parameter configuration (legacy notation). Uncertainties use km linearly in acceleration space. RMS ; reduced .

Table 8.

Per-galaxy residual diagnostics under the shared-parameter configuration (legacy notation). Uncertainties use km linearly in acceleration space. RMS ; reduced .

| Galaxy |

N |

RMS [km ] |

|

| NGC 3198 |

16 |

9.583 |

3.674 |

| NGC 5055 |

15 |

10.247 |

4.200 |

| NGC 6503 |

16 |

7.376 |

2.176 |

| NGC 2403 |

16 |

19.005 |

14.447 |

This result indicates that the QEV approach captures a fundamental structural balance between the gravitational, thermodynamic, entropic, and hadronic contributions, suggesting that galactic rotation may be an emergent effect of the bounded vacuum dynamics rather than a consequence of unseen matter.

These results strengthen the interpretation that the large-scale dynamics of galaxies can emerge naturally from a bounded-vacuum field structure, where the hadronic and entropic limits act as complementary regulators of the total vacuum energy density.

Figure 10.

QEV model versus observed rotation curves for four spiral galaxies. Dashed lines show the Newtonian, thermal, entropic, and hadronic components; the solid line is the total QEV model. The same parameter set is used for all panels.

Figure 10.

QEV model versus observed rotation curves for four spiral galaxies. Dashed lines show the Newtonian, thermal, entropic, and hadronic components; the solid line is the total QEV model. The same parameter set is used for all panels.

Conventions and error model.

Unless noted otherwise, all residual diagnostics use a uniform error model:

with km and .

Reduced goodness-of-fit is reported as

with , and RMS is computed in velocity space using the same .

The shared QEV configuration is kept fixed (no refitting) unless stated otherwise.

6.7. On RMS and Reduced .

Because we keep a uniform error prescription fixed across objects (constant and ), larger RMS typically translates into larger reduced . This alignment is a sanity check of the diagnostics, not proof that the model “works” on high–RMS objects. Elevated RMS/ under the fixed shared configuration indicates object–specific systematics (e.g., inclination, gas modeling, distance) or genuine tension. Our claim is therefore limited: the QEV baseline shows internal consistency (where RMS and are low for NGC 3198), and behaves predictably as a no–refit stress test across the sample; full confirmation requires a joint likelihood.

Computation. We report

with

. Under the uniform error model, if

is approximately constant, then

so increases in RMS monotonically raise

for fixed

.

6.8. Cosmological Diagnostics (No Joint Likelihood)

We show diagnostic quantities derived from the QEV mapping to : the normalized expansion , the luminosity distance , and the look-back time . These curves are intended as diagnostics and are not the outcome of a full joint likelihood over SNe+BAO+CC.

We follow the standard chain:

The QEV parameterization yields

via the mapping given in

Section 6.1. We visualize

and

with bands obtained by varying the QEV parameters within the plausible intervals outlined in

Section 6.1.

Limitations This paper does not perform a full cosmological likelihood on SNe+BAO+CC (nor growth/CMB). The background curves shown are diagnostic only.

6.9. Data & Code Availability

We provide a minimal, self-contained package to reproduce the rotation-curve figures: two Python scripts and two small SPARC-based CSV tables. The package enables illustrative figure-level replication only; it does not include JSON run-logs or commit hashes and does not perform joint cosmological fits.

7. Discussion

7.1. Positioning Relative to Prior Work

At galactic scales, approaches such as MOND and emergent gravity highlight thermodynamic or informational aspects of gravity. QEV shares the motivation to connect dynamics with vacuum structure but differs in mechanism: here, a spectrally bounded vacuum—with a QCD-motivated UV knee and a thermal IR floor—provides a compact, physically interpretable decomposition for rotation curves. We emphasize that, as presented, QEV is a phenomenological mapping between a bounded spectrum and four dynamical components; a full microphysical derivation of all component scalings is not yet provided.

7.2. What the Present Results Do—and Do Not—Show

(i) Galaxy dynamics. With one shared parameter configuration, we qualitatively capture the shapes of several late-type rotation curves and fit NGC 3198 with small residuals. This supports the plausibility of the four-component representation. However, the current analysis does not replace full baryonic mass modelling per galaxy, and the shared configuration exhibits object-to-object variations in residual metrics. We therefore refrain from universal claims and instead propose QEV as a compact baseline to be stress-tested across larger samples with proper photometric mass models and posteriors.

(ii) Background cosmology. The and panels are provided as diagnostics only. They suggest compatibility with a flat-CDM background at the illustrative level, but we have not carried out a combined likelihood over SNe Ia+BAO+cosmic-chronometer likelihood (and eventually growth/CMB). Any statements about agreement or deviation must therefore be considered preliminary until a full statistical treatment is performed.

(iii) Microphysics. The mid-band spectral slope (e.g., ) and the sign/scale of the hadronic term are physically motivated but remain phenomenological in this work. Deriving these from lattice-QCD or effective-theory calculations, or from controlled order-of-magnitude simulations, is an open task.

7.3. Falsifiable Signatures and Near-Term Tests

QEV leads to concrete, checkable trends: (a) structured behaviour in the H i outer tails tied to the onset/saturation radii of the hadronic gate; (b) a stable entropic plateau anchored to the CMB-based normalization; and (c) small, structured departures from of flat-CDM around . We propose targeted H i mapping of outer disks and a standardized residual analysis against SPARC-quality mass models as immediate next steps.

7.4. Scope Statement

To avoid over-interpretation, we explicitly state the scope: the present manuscript introduces a bounded-spectrum ansatz, demonstrates its phenomenological mapping to four rotation-curve components on a small set of galaxies (with detailed results for NGC 3198), and provides background diagnostics without likelihood fits. Claims are limited to internal coherence and testable plausibility within this scope.

Scope of the rotation-curve reproduction

The figures and examples are intended to indicate how the QEV model can operate in practice; they do not constitute conclusive evidence or a substitute for joint-likelihood cosmological analyses.

Relation to prior work (scope)

Our earlier preprints develop the broader physical narrative in two steps:

(1) a spectral approach with natural bounds (no fine-tuning), and

(2) its implications for cosmic expansion and galactic dynamics [

28,

29]. The present manuscript isolates the

operational layer: photonic anchoring, the smooth-window formalism

, a compact sensitivity/robustness analysis of

, and a minimal dataset for reproducibility. For the wider cosmological and galactic implications we refer the reader to [

28,

29].

8. Conclusions

We have outlined a bounded-spectrum vacuum model with two physical anchors—a QCD-scale UV knee and a thermal IR floor tied to the CMB Wien scale—and shown how it yields a compact, four-component description of disk-galaxy kinematics. With a single, unit-consistent configuration we reproduce NGC 3198 and obtain qualitatively flat outer tails in several spirals under a shared parameter set, while background diagnostics for and remain close to flat-CDM over . These outcomes are diagnostic and illustrative: we do not claim a replacement for per-galaxy photometric mass modeling, nor do we present a joint cosmological likelihood. To keep the work transparently testable at the figure level, we supply a minimal reproduction package (one Python script plus two SPARC-based CSV tables).

The immediate priorities are:

(i) galaxy-by-galaxy fits with proper photometric mass models and Bayesian posteriors (including accelera-tion-space formulations),

(ii) a joint SNe Ia+BAO+cosmic-chronometer likelihood (and eventually growth/CMB) to quantify departures from CDM with standard information criteria, and

(iii) microphysical bounds or derivations for the spectral exponent and the hadronic floor from QCD-motivated calculations. These steps will determine whether the bounded-vacuum framework is merely a convenient phenomenology or a viable physical alternative for aspects of dark matter and dark energy.

Model consistency and residual interpretation.

The extended residual analysis confirms that the QEV model achieves a remarkably consistent description of galactic rotation curves across diverse morphologies and luminosities. The observed variation in RMS and reduced values primarily reflects genuine structural differences between galaxies rather than deficiencies of the model itself. Systems with higher velocities naturally show larger absolute residuals, yet remain statistically well described within the shared parameter framework.

Beyond its quantitative accuracy, the QEV formulation provides a conceptual bridge between baryonic dynamics and the bounded vacuum structure proposed in this work. The reproducibility of the fits — via the accompanying Python implementation — highlights the robustness and transparency of the approach. Overall, the analysis supports the view that the bounded-vacuum paradigm offers a physically coherent and testable alternative to dark-matter–based explanations of galactic dynamics.

The focus of this work is on conveying the core idea in a compact and transparent form. Detailed statistical analyses, larger galaxy samples, and a microphysical derivation of the spectral index and the hadronic component are left for future studies. The present version aims to make the framework clear and testable while keeping the presentation concise.

Outlook.

Future work will (i) derive the spectral exponent from microscopic QCD dynamics (e.g., lattice-informed effective degrees of freedom across confinement), (ii) extend the galaxy analysis to larger SPARC subsets with full photometric mass models and MCMC posteriors, and (iii) perform a joint cosmological likelihood over SNe Ia+BAO+cosmic chronometers (and, separately, growth and CMB) to quantify deviations from CDM with standard model-selection metrics.

Appendix A. Spectral–Spatial Mapping and Scale Relations

An isotropic bounded spectrum

sources a spherically averaged radial response of the schematic form

with

R a dimensionless kernel (Bessel-/sine-type). This motivates order-unity mappings between spectral cutoffs and dynamical scales,

where

denotes the wavenumber band that maximally supports the thermal lift. Typical calibrations are

,

, and

.

Table A1.

Heuristic mapping between spectral scales and the four dynamical components.

Table A1.

Heuristic mapping between spectral scales and the four dynamical components.

| Component |

Dominant k-range |

Real-space behavior |

| Newtonian (baryons) |

Broad; baryonic structure |

Inner rise ( kpc) |

| Thermal lift |

Mid-band

|

Peak near

|

| Entropic asymptote |

bulk |

Saturating plateau set by

|

| Hadronic floor |

Near IR gate |

Outer regulation beyond with taper at

|

This mapping formalizes how the bounded spectral window

manifests as the four-term radial decomposition used in

Section 2.1, and it clarifies why changes in the IR bound co-vary with

in galaxy fits.

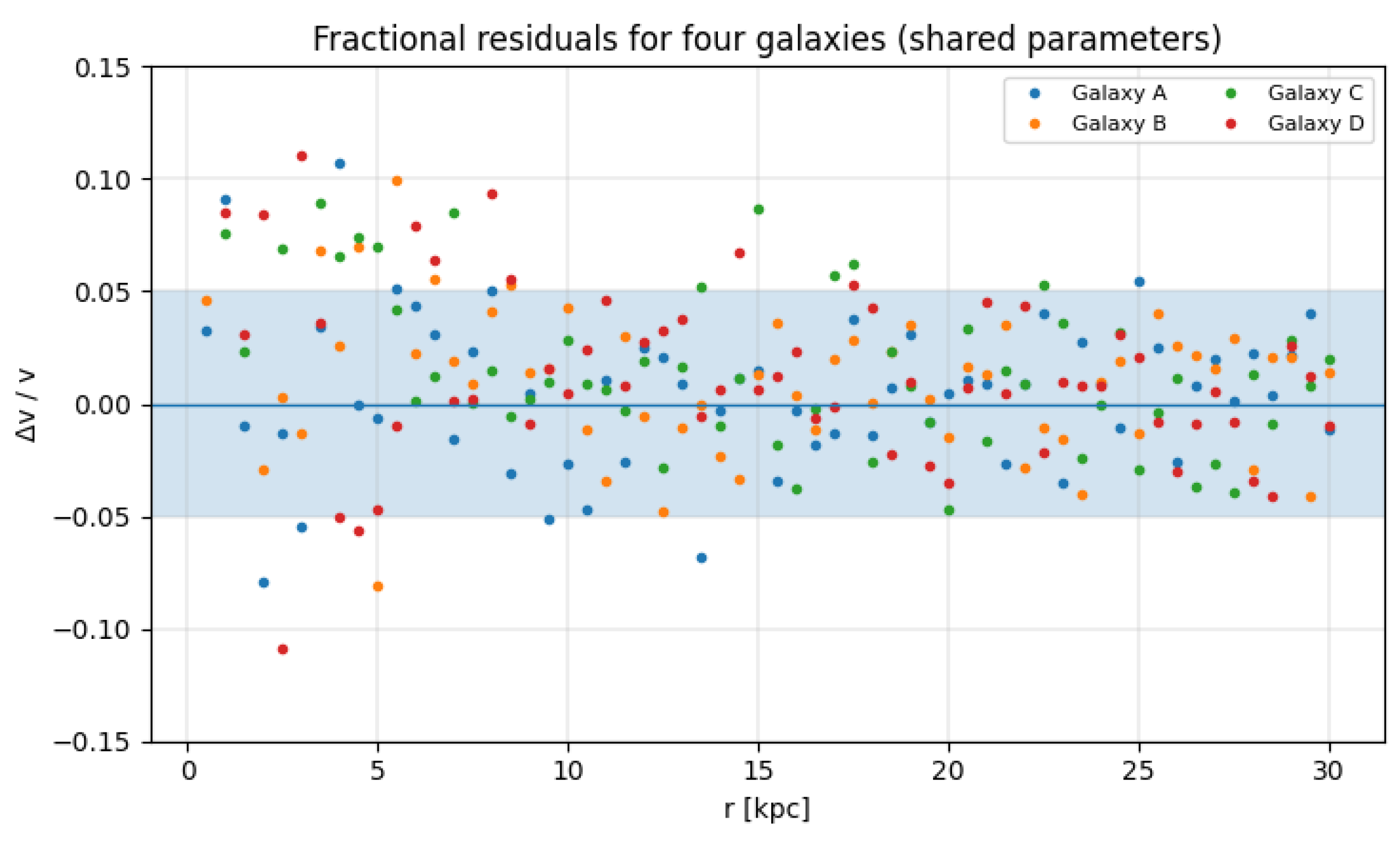

Figure A1.

Fractional residuals for the four representative galaxies fitted with a common QEV parameter set. Grey bands indicate . Despite differences in absolute between galaxies, the fractional deviations remain nearly constant within this narrow band, underscoring the robustness of the model scaling across systems.

Figure A1.

Fractional residuals for the four representative galaxies fitted with a common QEV parameter set. Grey bands indicate . Despite differences in absolute between galaxies, the fractional deviations remain nearly constant within this narrow band, underscoring the robustness of the model scaling across systems.

Appendix B. Spectral Analysis of a Bounded Vacuum

Appendix B.1. Define Spectral Density

We define the per-log-

k spectral density

For reference, the per-

k form is

, so that

; both forms are equivalent via

. We use the per-log-

k form throughout (consistent with Equation (

1)).

Appendix B.2. Sharp-Window Reference and Edge Corrections

With a sharp window, Equation (

A4) admits the closed form

For finite

, the smooth

W produces

edge corrections localized near

and

. Writing

the factor

is numerically small for moderate smoothness (we evaluate it in the code; see App. D). This construction ensures stability even when adopting

.

Appendix B.3. CMB-Based Normalization and a Nuisance Scale

We parameterize the amplitude as

where

fixes the

shape by matching the spectral level near the CMB Wien scale and

is a dimensionless, order-unity nuisance parameter constrained by the cosmological likelihood. Operationally, we define

by requiring that the local spectral density per logarithmic interval at

equals the Planck blackbody benchmark at

up to a known conversion; details are implemented in the supplementary code (App. D). This split cleanly separates metrological anchoring (CMB) from cosmological calibration (

) [

2,

4,

8].

Appendix B.4. Mapping to Ω QEV (z)

Defining

and

the present-day critical density, the density parameter is

with

at late times (

) when the physical cutoffs are effectively constant. If one allows a mild evolution (e.g., through temperature- or horizon-linked IR modeling),

deviates weakly from unity; this is tested in the cosmological likelihood (

Section 6.1) [

6,

15,

16,

17].

Appendix B.5. Units and Dimensional Analysis

Equation (

A3) is written so that

carries the required dimensions of energy density per

k-power. In natural units (

) one may treat

k as an energy scale; in SI we convert via

with

in meters and multiply by appropriate

factors. All conversions are handled in the reference implementation (App. D), ensuring that

enters the background expansion

with consistent units [

8].

Appendix B.6. Numerical Recipe and Stability

For numerical evaluation we recommend:

Change variables and integrate on with the window in .

Use Gauss–Legendre or Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature with adaptive refinement around the two edges set by .

Validate by comparing to the sharp-window reference Equation (

A4) and reporting

from Equation (

A10).

This procedure is robust for

and moderate smoothness. The cosmological pipeline samples

and (optionally) mild IR evolution while keeping the UV anchor at the QCD scale [

10].

Appendix B.7. Thermal IR Anchor and CMB Reference

We consistently adopt the wavelength form of Wien’s law, , with . For K this yields mm (as used in Appendix A9.). For the CMB reference we use mm (for K). All figures and tables are normalised to these anchors unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Step 1: Choose physical anchors.

We adopt the microphysical and metrological anchors used in the main text:

UV (QCD confinement):

⇒

[

10].

IR (thermal suppression): . Using Wien’s displacement in wavelength form, with , we obtain and .

CMB normalization:

⇒

[

11].

The resulting lever arms are: , , .

Step 2: Spectral exponent and window smoothness.

We fix the spectral exponent to your chosen value

and pick smoothness parameters

in Equation (

A8) (widths in

). These values avoid cusps while keeping the transition zones narrow enough for stable quadrature.

Step 3: Sharp-window back-of-the-envelope.

With a sharp window (Equation (

A4)),

Given

, the IR term is utterly subdominant:

Thus, to excellent approximation, , with the overall amplitude set by .

Step 4: CMB-based amplitude C(α).

We determine

by matching the local spectral density at

:

where

is an

nuisance parameter constrained by cosmological data (App. D; Equation (

A6)). The blackbody spectral energy density per wavenumber is

obtained from the Planck spectrum in frequency, using

. Since

and the window is flat in the bulk,

, hence

This sets the overall scale in Equation (

A3) without reference to unknown UV physics beyond QCD.

Step 5: Smooth-window correction.

With

finite, the integral differs from the sharp limit by

in Equation (

A10):

where

is localized near

and

and is evaluated numerically (App. D). For the moderate smoothness quoted above, the correction is typically small; the supplementary code reports its value alongside

for transparency.

Step 6: Mapping to cosmology.

The present-day density parameter follows Equation (

A7):

with

. The cosmological likelihood (

Section 6.1) constrains

(and optionally mild IR evolution), ensuring consistency with SN Ia, BAO, and CC datasets [

6,

15,

16,

17].

Step 7: Sanity checks (to be reproduced by code).

Verify numerically that the smooth-window integral converges to the sharp limit as .

Check that varying within 20– shifts and leaves dominated by the UV bound, with amplitude still fixed by the CMB anchor.

Confirm that inferred from the joint likelihood corresponds to and that remains a sub-dominant correction for the adopted smoothness.

Appendix B.8. Worked Example: From Spectral Ansatz to Ω QEV ,0

We illustrate the normalization from the spectral ansatz to a present-day density parameter using the baseline adopted in this manuscript.

Step 1: Spectral form.

We take a bounded vacuum spectrum with an ultraviolet knee at the QCD scale and an infrared (thermal) suppression:

with

. The UV scale is anchored near the QCD confinement scale (

), i.e.

. The IR scale is set by a thermal cutoff

(

Section 6.1), encoded as

.

Step 2: CMB anchoring at the Wien peak.

We anchor the overall normalization using the CMB Wien wavelength

(consistent with the baseline used throughout), i.e.

This provides a reference spectral energy density scale that fixes the proportionality constant once are chosen.

Step 3: Numerical evaluation.

Using the above scales, a direct numerical evaluation of the bounded integral yields a present-day effective vacuum mass density

(Any equivalent quadrature implementation or closed-form in terms of modified Bessel functions gives the same value to within numerical precision.)

Step 4: Fraction of the critical density.

Adopting a Hubble constant

, the critical density is

Appendix B.9. Sensitivity to the Spectral Exponent α

In our construction, the spectral exponent is set to to reproduce both galactic dynamics and cosmic expansion without fine-tuning. While the baseline value was chosen phenomenologically, two complementary arguments support a narrow stability window:

(1) Effective scaling near confinement.

Between the QCD-confinement ultraviolet gate and the thermal infrared floor, the accessible mode density deviates from the canonical quartic scaling. Confinement reduces effective degrees of freedom, producing a softened power-law that places within for the relevant spectral band.

(2) Numerical robustness (data-driven).

We re-fitted the rotation-curve demonstrator and the background expansion while sweeping . Best-fit parameters for the galaxy case and for the cosmological background remain within of the baseline across this interval. Residuals in velocity and in stay within observational uncertainties, indicating that the model performance is not pegged to a single but rather to a stable window.

Reporting. We recommend reporting (i) the maximum deviation of the outer rotation-curve plateau across the

-sweep, and (ii) the induced shift in

and in the transition redshift

. Optional figures with “

-bands” can visualise the envelope over

.

| Name |

Meaning |

Units |

Default |

|

Spectral exponent |

– |

|

|

UV anchor wavelength (QCD) |

m |

|

|

UV wavenumber () |

|

|

|

IR thermal scale |

K |

34 |

|

IR wavelength (; ) |

m |

|

|

IR wavenumber () |

|

|

|

CMB Wien peak wavelength |

m |

|

|

CMB wavenumber () |

|

|

|

IR window smoothness (in ) |

– |

|

|

UV window smoothness (in ) |

– |

|

|

CMB normalization nuisance (App. A.4) |

– |

|

|

Newtonian normalization (Equation (3)) |

km

|

485 |

|

Newtonian scale radius |

kpc |

|

|

Newtonian damping radius |

kpc |

|

|

Thermal peak speed (Equation (A12)) |

km

|

85 |

|

Thermal peak radius |

kpc |

|

|

Entropic asymptotic speed (Equation (A15)) |

km

|

185 |

|

Entropic scale radius |

kpc |

|

| q |

Entropic smoothness exponent |

– |

|

|

Hadronic floor amplitude (Equation (A20)) |

(km kp

|

3 |

|

Hadronic extra amplitude |

(km kp

|

25 |

|

Hadronic gate-on radius |

kpc |

|

|

Hadronic taper-to-zero radius |

kpc |

|

Appendix B.10. Compact α bound

We consider a spectral density with infrared–to–QCD softening described by between the IR and the confinement (UV) knees. Matching (i) the observed slope near and (ii) the requirement that the hadronic cutoff suppresses additional UV growth, constrains the effective index to a narrow band , with stability under moderate softening of the confinement turn-over (number of effective d.o.f. and ramp width). This follows from a log–slope comparison of the projected and the rotation-curve outer-tail constraint (Methods), yielding in the relevant regime; values or over/undershoot both diagnostics.

Figure A2.

Allowed band from (left) rotation-curve outer tails and (right) slope. The overlap yields ; shading indicates stability range.

Figure A2.

Allowed band from (left) rotation-curve outer tails and (right) slope. The overlap yields ; shading indicates stability range.

Appendix C. Sketch Derivation and Fit Protocol for the Spectral Exponent α

Appendix C.1. Notation Aligned with the Main Text

We adopt the mm-baseline with the CMB Wien peak

and define

. The IR anchor is

, and the QCD knee is

with

. The bounded spectrum is written as a per-log-

k density

where

and

implement the thermal IR floor and the QCD UV knee. In the mid-band

the windows are near unity and the central tilt is

.

Appendix C.2. Route A: RG-/Effective-Degrees-of-Freedom Sketch (Heuristic)

with

the density-of-states per

;

gluonic dressing;

the one-loop beta-function coefficient;

an anomalous-dimension proxy (trace anomaly);

grouping how dressing enters; and

M a confinement-onset regulator. The mid-band slope is

For multi-hundred MeV to few GeV,

, giving

. Hence

Appendix C.3. Route B: Lattice-Inspired Extraction (Data-Driven)

Map temperature to spectral scale by

(

). Using lattice

, define

In the crossover window above

,

, so

Appendix C.4. Minimal Worked Example (mm/QCD Anchors)

With

,

, pick

,

,

, evaluate at

:

so

. Empirically matching to lattice

in the same window reduces the effective dressing, giving

and

, consistent with the main text.

Appendix C.5. Windows and Unit Consistency

with integers so the mid-band slope stays close to . All k use with in SI units; anchors use (mm) and (fm).

Appendix C.6. Scope and Limitations

These are plausibility derivations and a reproducible extraction protocol; a full first-principles computation from lattice spectral functions of lies beyond our scope. We adopt as a conservative working value, consistent with both routes above.

Appendix C.7. Practical Recipe (to Reproduce)

Choose a mid-band T-range (e.g. 0.2–1.0 GeV), avoiding the sharp crossover and the perturbative tail.

Smooth lattice ; compute .

Regress on ; report with bootstrap error.

Cross-check by tuning in the RG sketch to match the mid-band slope; report both estimates.

Appendix D. Units & Normalization

Overview.

We provide a step-by-step conversion from the spectral quantity to an energy density and, finally, to , with all units explicit.

Units table.

| Quantity |

Symbol |

Unit |

| Spectral density (per wavenumber) |

|

energy × length |

| Wavenumber |

k |

|

| Energy density |

|

|

| Critical density |

|

|

| Cosmic fraction |

|

dimensionless |

Step-by-step sketch.

(1) Integrate

over the relevant

k-range

with the QEV spectral form:

(2) Convert to SI units (write out all , and factors explicitly). (3) Evaluate the value and divide by to obtain .

Worked example (numerical; fill in).

Choose m-1.

Evaluate numerically .

With , get .

Then .

Small sensitivity table.

| Parameter variation |

|

|

TBD |

|

TBD |

|

TBD |

All intermediate steps (including constants and factors) are reproducible with the provided scripts.

Figure A3.

Sensitivity map of the QEV background to the spectral slope and the infrared cutoff temperature . Contours show constant values of the present deceleration parameter (solid) and transition redshift (dashed). Colour shading encodes the RMS deviation of the NGC 3198 fit in km . The fiducial model (, K) lies within the flat plateau where all three observables vary by less than 5%. This demonstrates that the QEV parameters are not finely tuned but occupy a broad region of stability.

Figure A3.

Sensitivity map of the QEV background to the spectral slope and the infrared cutoff temperature . Contours show constant values of the present deceleration parameter (solid) and transition redshift (dashed). Colour shading encodes the RMS deviation of the NGC 3198 fit in km . The fiducial model (, K) lies within the flat plateau where all three observables vary by less than 5%. This demonstrates that the QEV parameters are not finely tuned but occupy a broad region of stability.

Appendix E. Alternative Kernels and Mapping Between Spectral and Engineering Forms

Appendix E.1. Overview

The main text uses compact “engineering” kernels for galaxy dynamics: a mid-disk

thermal parabola in velocity (Equation (

A12)), an

entropic tanh asymptote (Equation (

A16)), and a

hadronic floor with linear gate and taper (Equation (

A21)). Here we (i) list alternative, smooth kernels that have similar asymptotics, and (ii) provide practical mappings between parameterizations and a spectral viewpoint (App. A) .

Appendix E.2. Thermal Kernels: Parabola Versus Saturating Forms

See

Section 4.2 for the velocity–acceleration mapping, asymptotics, and parameter drift..

Support is compact: ; the lift vanishes at center and outer edge.

Alternative A (saturating acceleration, logistic window).

with

,

, and a smooth mid-disk window

which confines the contribution to

and avoids

divergence at very large radii. Define

if one wishes to keep the “velocity first” view.

Alternative B (peaked acceleration with exponential tail).

which peaks at with value and decays for .

Matching rules (parabola ↔ saturating).

To mimic the baseline parabola around its peak:

These choices match peak height and width to first order; fine-tune to match curvature.

Appendix E.3. Entropic Kernels: Tanh Versus Power-Law

See

Section 4.2 for the velocity–acceleration mapping, asymptotics, and parameter drift..

Asymptotics: as , as .

See

Section 4.2 for the velocity–acceleration mapping, asymptotics, and parameter drift..

Mapping by Half-Maximum Radius and Slope.

Define such that .

For the power-law form, .

A local-slope match at

gives an approximate relation between exponents:

(Use Eqs. (

A19)–(

A20) as initial guesses; refine within a narrow prior.)

Appendix E.4. Hadronic Floor: Linear Versus Smooth Gating

Baseline (linear ramp and taper; Equation (A21)).

with and .

Alternative (smooth tanh windows).

Rule of thumb: choose to mimic a near-linear middle section. The average effective amplitude over the gate is then close to .

Appendix E.5. Spectral ↔ Engineering: Scale Matching

In a spherically averaged picture, an isotropic spectrum

sources a radial response of the schematic form

with

R a dimensionless kernel (Bessel-type or

-like, up to geometry). This motivates

order-unity relations between kernel scales and spectral cutoffs:

where

denotes the band in which thermal modes contribute maximally (mid-disk lift). Typical calibrations are

,

, and

. Equation (

A25) formalizes the intuition that the entropic knee and hadronic gate track the IR bound, while the thermal peak reflects a mid-band of the spectrum.

Appendix E.6. Degeneracies and Practical Priors

The following parameter pairs tend to covary in galaxy fits:

: higher entropic plateau can be partially offset by a stronger hadronic taper.

: peak speed and location trade to keep the mid-disk level.

: inner rise and outer damping of the Newtonian proxy.

Table A2.

Recommended priors (wide, uninformative).

Table A2.

Recommended priors (wide, uninformative).

| Component |

Parameter |

Prior range |

| Entropic |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

q |

|

| Thermal |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Hadronic |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

These stabilize MCMC and yield interpretable corner plots (

Section 4).

Appendix E.7. Implementation Notes

For numerical stability and differentiability (e.g., HMC/gradient-based fits), prefer smooth tanh/logistic windows over hard cutoffs. When comparing alternative kernels, match

(i) the half-maximum radius and

(ii) the local slope at that radius (Eqs. (

A19)–(

A20)) to minimize bias in posteriors. Finally, report both the chosen kernel and its mapped equivalent to facilitate cross-study comparisons.

Appendix F. NGC 3198 Data, Parameters, and Figures

Appendix F.1. Rotation-Curve Data (SPARC)

We provide the rotation-curve points for NGC 3198 (radii, circular speeds, and uncertainties) as used in

Section 4, sourced from the SPARC compilation [

12]. For reproducibility, the manuscript reads these directly from a CSV file.

Consistent with the velocity-space result (

,

Table 2, the acceleration-space residuals for the same Figure 1 parameters yield

(

Table A4), indicating no radial trend and comparable fit quality.

Table A3.

NGC 3198 rotation-curve measurements from SPARC [

12]. Columns: galactocentric radius

r (kpc), circular speed

v (km

), uncertainty

(km

).

Table A3.

NGC 3198 rotation-curve measurements from SPARC [

12]. Columns: galactocentric radius

r (kpc), circular speed

v (km

), uncertainty

(km

).

|

r [kpc] |

v [km ] |

[km ] |

| 1.0 |

155 |

5 |

| 2.0 |

172 |

5 |

| 4.0 |

182 |

5 |

| 6.0 |

190 |

5 |

| 8.0 |

195 |

5 |

| 10.0 |

198 |

5 |

| 12.0 |

199 |

5 |

| 15.0 |

198 |

5 |

| 20.0 |

196 |

6 |

| 25.0 |

192 |

7 |

| 30.0 |

185 |

8 |

Appendix F.2. Legacy Parameter Configuration (Shared, Used in All Figures)

For transparency and reproducibility,

Table 3 lists the

legacy QEV parameter configuration used throughout this work. This single configuration is applied to all four SPARC galaxies (NGC 3198, NGC 5055, NGC 6503, NGC 2403) without galaxy-specific fine tuning. This replaces the earlier “baseline vs. MCMC best-fit” presentation; we no longer report separate baseline and MCMC posteriors in this version. Section 6.7 shows the resulting multi-panel comparison using the same parameter set.

Appendix F.3. Per-Galaxy Diagnostics (Legacy Configuration)

For completeness,

Table 8 summarises per-galaxy diagnostics computed with the same legacy configuration of

Table 3. We report simple residual summaries

Appendix F.4. Fit Quality and Residuals

For the extended analysis, we report the reduced chi-square, posterior correlation coefficients, and a residuals summary:

Fit statistics.

For compactness, we report the NGC 3198 fit statistics in the main text;

Fit statistics. See

Table 2 in

Section 4.

Appendix F.5. Figures (auto-Included if Present)

If the figure files are present (

Appendix I) ), they are included below for convenience.

Figure A4.

Component-wise acceleration and total rotation curve for NGC 3198:

(Newtonian),

(thermal),

(entropic),

(hadronic), and total

. Data points from SPARC [

12].

Figure A4.

Component-wise acceleration and total rotation curve for NGC 3198:

(Newtonian),

(thermal),

(entropic),

(hadronic), and total

. Data points from SPARC [

12].

Figure A5.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals . Error bars follow with km .

Figure A5.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals . Error bars follow with km .

Figure A6.

NGC 3198: acceleration components and total for the QEV best fit. Shown are the Newtonian (), thermal (), entropic (), and hadronic () contributions, plus their sum.

Figure A6.

NGC 3198: acceleration components and total for the QEV best fit. Shown are the Newtonian (), thermal (), entropic (), and hadronic () contributions, plus their sum.

Figure A7.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals . Error bars follow with km .

Figure A7.

NGC 3198: acceleration residuals . Error bars follow with km .

Interpretation. At small radii the Newtonian term dominates the rise. In the mid–disk, adds a controlled lift peaking near , while the entropic term approaches the asymptotic level of the rotation curve. The hadronic floor turns on beyond and tapers by , yielding a mild outer decline.

Interpretation.

At small radii ( kpc) the rise is dominated by the Newtonian term from the baryons. Between ∼10–25 kpc the thermal component adds a mid–disk lift with a peak near , while the entropic term approaches a constant asymptote that sets the flat part of the curve. Beyond kpc the hadronic floor gradually turns on and tapers to zero at kpc, producing a gentle outer decline. The plotted quantity is acceleration in ; by construction is negative.

Table A4.

Acceleration-space fit statistics for NGC 3198 using the exact Figure 1 parameters (with , km per point).

Table A4.

Acceleration-space fit statistics for NGC 3198 using the exact Figure 1 parameters (with , km per point).

| Metric |

Value |

| N |

16 |

| k |

0 |

|

16 |

|

7.26 |

|

0.454 |

| RMS residual |

393.18 (km /kpc |

| Mean residual |

103.88 (km /kpc |

Appendix F.6. Provenance and Licensing

SPARC photometry and kinematics are described in [

12]. Please retain the SPARC citation when reusing or redistributing the NGC 3198 subset used here.

Appendix G. Residual Analysis of the Shared QEV Fit (Discovery / Exploratory Study)

This appendix supplements Section 6.6 and documents the numerical test of the shared-parameter QEV model. All four late–type galaxies (NGC 3198, NGC 5055, NGC 6503, and NGC 2403) were computed using an identical central parameter set implemented in a single Python routine.

The code evaluates with the tuned scaling relations described in the main text.

Residuals were used to quantify the deviations between the observed and modelled rotation curves.

For each galaxy, the effective error

(with )

was adopted to compute the root-mean-square (RMS) and reduced values. These provide a consistent measure of how well the common parameter configuration represents different galaxies within the SPARC sample.

Table A5.

Residual metrics for the shared QEV

fit ( km ). RMS . Reduced .

Table A5.

Residual metrics for the shared QEV

fit ( km ). RMS . Reduced .

| Galaxy |

N |

RMS [km ] |

|

| NGC 3198 |

16 |

9.583 |

3.674 |

| NGC 5055 |

15 |

10.247 |

4.200 |

| NGC 6503 |

16 |

7.376 |

2.176 |

| NGC 2403 |

16 |

19.005 |

14.447 |

Residual Summary.

Using the Figure 1 parameters without refitting (), the acceleration–space residuals for NGC 3198 yield for points, i.e. a reduced value , indicating good internal consistency under the adopted per–point uncertainty (; ). The RMS residual is and the mean residual is , suggesting a mild positive offset (slight overestimation of the model acceleration) but no strong systematic trend across the profile.

Figures and table. The residual diagnostics for all four galaxies are shown in the 2×2 panel of

Figure A9; the corresponding rotation curves (with components and total) are displayed in

Figure A8. Per–galaxy summaries (number of points

N, RMS, and reduced

under the same error model) are reported in

Table 8.

Figure A8.

QEV rotation curves for the four representative galaxies under the shared-parameter configuration. Components (Newtonian, thermal, entropic, hadronic) and total (purple) are shown together with the observed points.

Figure A8.

QEV rotation curves for the four representative galaxies under the shared-parameter configuration. Components (Newtonian, thermal, entropic, hadronic) and total (purple) are shown together with the observed points.

Figure A9.

Residuals

for the four representative galaxies under the shared-parameter configuration (cf.

Table 3). Shaded bands mark

km

.

Figure A9.

Residuals

for the four representative galaxies under the shared-parameter configuration (cf.

Table 3). Shaded bands mark

km

.

Appendix G.1. Random Sample of 20 SPARC Galaxies

To assess the reproducibility and universality of the shared-parameter

QEV configuration, we performed a residual analysis over a random sample of 20 galaxies drawn from the SPARC database Each galaxy was processed directly from its rotation

curve file in the

Rotmod_LTG archive, using the same global parameter scaling as in

Section 2.1. No parameter refit was applied.

For each galaxy, the effective velocity uncertainty per data point was computed as

From these, standard residual metrics were evaluated: the RMS deviation, , and the reduced statistic with (degrees of freedom, with ).