1. Introduction

Neonatal sepsis (NS) is a life-threatening condition caused by an inappropriate host response to a systemic bacterial, viral, or fungal infection within the first 28 days of life in both normal and premature infants [

1]. NS is the main cause of neonatal mortality in Ghana and the reason for admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [

2]. Depending on when the disease first manifests itself, NS is categorized into two types: early-onset sepsis (EOS) (<72 hours) and late-onset sepsis (LOS) (>72 hours). Pathogens found in the mother's vaginal canal are typically the cause of EOS, while pathogens originating in the community or hospital are the cause of LOS [

3]. Clinicians typically rely on a combination of clinical features, laboratory parameters, and risk factors such as low birthweight, prolonged rupture, and maternal labor to establish a diagnosis. Common clinical indicators include poor feeding, lethargy, temperature instability, respiratory distress, and seizures. Laboratory findings such as abnormal white blood cell counts (<5,000 or >30,000/mm³), elevated immature-to-total neutrophil ratios (>0.2), thrombocytopenia (<150,000/mm³), and increased inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) (>10 mg/L) or procalcitonin (>2 ng/mL) support the diagnosis. Blood culture remains the gold standard, but empirical treatment is often initiated in suspected cases due to the high risk of rapid progression and mortality [

4]

In Africa, the rate of NS is about twenty per thousand live births, mainly due to poor intrapartum and postnatal practices. NS is not only detrimental to the newborn but also places a financial burden on the family [

5]. As the signs and symptoms of NS are non-specific, especially in neonates, the majority of cases are diagnosed clinically and treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The main challenges in the treatment of NS are the increasing emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and the lack of newer effective antibiotics [

6]. While waiting for culture confirmation, broad-spectrum antibiotics are initially used as empirical treatment for NS, which increases the risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [

7]. A growing concern is not only the prevalence of resistance but also the mechanisms driving it. Key contributors include the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), which inactivate third-generation cephalosporins; carbapenemases, which compromise the efficacy of carbapenems; and the emergence of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative

staphylococci (MRCNS) due to altered penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). Additionally, resistance is exacerbated by mechanisms such as efflux pump overexpression and reduced outer membrane permeability in Gram-negative bacteria, further limiting antibiotic effectiveness [

8].

Newborns suspected of having meningitis or septicemia should be treated as soon as culture samples and intravenous access are available [

9]. Identification of the likely pathogens and the susceptibility pattern of the organisms is necessary to make the correct choice of antimicrobial drugs for treatment [

10].

In 2021, Tetteh

et al, 2022 [

11] conducted operational research under the Structured Operational Research and Training IniTiative (SORT-IT) to understand the bacterial profile, antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST), and turnaround times (TAT) in 471 neonates with suspected sepsis admitted to 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, from 2017-2020. According to the study, neonates who were culture-positive had a median TAT of three days, while neonates who were culture-negative had a median TAT of five days. Results showed that half (51%, n=241) received their culture reports after hospital discharge, with 15% (n=37) of reports being positive. Coagulase-negative

staphylococci (CoNS) were the most common, accounting for 55% (n=68) of the isolates, followed by

Staphylococcus aureus at 36% (n=45).

Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common isolate for Gram-negative organisms 40% (n=6). The most common pathogens for LOS (49% and 34%) and EOS (48% and 30%) were CoNS and S.

aureus, respectively.

The principal investigator and the team disseminated the study's results to relevant stakeholders within the hospital. As a result, in December 2022, the hospital management set up a common platform via WhatsApp to share the patient’s culture reports between physicians and laboratory scientists, which is expected to promote the prompt sharing of culture results for appropriate management and treatment. An existing hospital intercom system was also improved to facilitate the prompt sharing of culture results. Aside these interventions, however, the patient’s final reports are uploaded to the electronic medical record (EMR) to enable appropriate diagnosis and treatment of the patient, and for safe record keeping. Additionally, nursing staff were instructed to inform about the availability of Culture and Drug Sensitivity Test (CDST) reports during daily handover meetings, especially for the newborns who were scheduled for discharge.

Following the implementation of recommendations after operational research conducted in 2021, the impact of these interventions on hospital exit outcomes, the effects of the availability of culture reports on NS treatment and readmissions need to be studied. Discharge of neonates before culture reports may lead to re-admission in cases where the culture report turns out to be positive. Hence, this follow-up study is to further assess whether there has been an improvement in the TAT, availability of culture reports, the impact of culture reports on the management of sepsis among neonates in the hospital, and hospital exit outcomes during January 2022- July 2024. Additionally, we aim to describe culture positivity, bacterial profile, antibiotic prescription appropriateness, and antibiotic resistance patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

In this study, a cross-sectional analysis was conducted using routinely collected data from the EMR of neonates admitted with suspected sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, from January 2022 to July 2024.

2.1. Study Setting

The Ghana Health Service (GHS) and the Ministry of Health (MoH) are primarily responsible for the administration of healthcare in Ghana. Ghana's national universal health insurance program, the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), provides primary care, outpatient services, and basic hospital treatment to those insured. All medical treatment must be paid for by people who are not on the scheme.

37 Military Hospital is a level 4 facility with 600 beds, located in the Ayawaso East district of Greater Accra Region The hospital also provides referral services for healthcare in all medical specialties [

11]. All services within the hospital are free for active and retired military officers, civilian staff, and their under-18-year-old dependents (referred to as "entitled"). The services are either paid out of pocket, covered by private insurance, or covered by the NHIS for civilians who are not military employees and non-dependents (also known as "non-entitled") [

12].

Every month, about 60 newborns are admitted to NICU, which has a bed capacity of 29. The ratio of nursing staff to patients is approximately 1:4. In addition to the NICU, the pediatric department (including the pediatric emergency department, the pediatric outpatient department, and the Nkrumah ward) also receives newborn visits, albeit less frequently. Blood samples from neonates suspected of having sepsis are taken on the first day of admission and sent to the hospital's microbiology laboratory for AST and culture following an electronic laboratory request by an attending physician. In the meantime, newborns with suspected sepsis are prescribed empirical antibiotic treatment with ampicillin (75mg/kg/12 hourly) and ciprofloxacin (10mg/kg/12 hourly) as first-line therapy and meropenem ( 20mg/kg/12 hourly) and amikacin (15mg/kg/24 hourly) as second-line therapy according to local NICU guidelines [

13]. Pediatricians/neonatal nurses make changes in the management of suspected sepsis, including changes in antibiotic prescriptions based on culture reports and clinical status.

2.3. Laboratory Tests for Suspected Sepsis in Newborns

According to the manufacturer's instructions, neonates with suspected sepsis should have 1–3 ml of blood inoculated directly into Pediatric Bactec® Blood Culture Vials and incubated for five days in the Bactec Fx Blood Culture System (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA). An initial Gram staining is performed if bacterial growth is detected during the first five days (on any day). Blood, MacConkey, and Saboraud agar (Oxoid, UK) are used to prepare subcultures, which are then incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18 to 24 hours. The sample is also subcultured on chocolate agar plates and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 18 to 24 hours. Gram staining and standard biochemical methods are used to identify the bacterial isolates. The Phoenix100 Identification System (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) is used for bacterial speciation and AST according to the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

14]. Methicillin-resistant S.

aureus isolates are those that exhibit oxacillin resistance. If no bacterial growth is detected after five days of incubation, a final negative culture report is uploaded electronically to the EMR for access by treating physicians. AST is not performed for certain organisms, such as

Kodamaea ohmeri, Bacillus species,

Cedecea davisae, and

Micrococcus species, as these organisms are classified as contaminants. If an isolate shows resistance to at least one drug from three or more antimicrobial categories, it is classified as MDR. This reflects a clinically significant threshold, as it indicates the organism is no longer susceptible to multiple classes of antibiotics that are commonly used for treatment. Such resistance patterns greatly limit therapeutic options, complicate patient management, and highlight the urgent need for robust antimicrobial stewardship and surveillance programs [

15].

2.4. Dissemination Activities, Recommendations, and Actions Taken Following the Operational Research

We followed the following steps of implementation after the operation research by Tetteh et al in 2022. Step 1: Identify the Problem—The study analyzed 471 neonates (2017–2020), revealing median turnaround times (TAT) of 3 days (culture-positive) and 5 days (culture-negative), emphasizing the need for faster result dissemination. Step 2: Engage Stakeholders—The team engaged the head of pediatric department, hospital administration, physicians, and nurses, sharing findings in monthly meetings at the health facility. In addition, the findings were shared in a national conference in November 2022, ensuring stakeholder buy-in. Step 3: Develop Evidence-Based Interventions—Interventions including a WhatsApp platform for real-time culture report sharing, an upgraded intercom system, EMR integration of CDST reports, and nurse protocols to report results during handovers were developed. Step 4: Implement Interventions—By December 2022, hospital management launched these feasible solutions within existing infrastructure.

2.5. Study Population and Sample Size

From January 2022 to July 2024, 506 newborns were admitted to the hospital with suspected sepsis and had blood cultures performed. The EMR records of all the above neonates were considered for this study. All other newborns admitted to the hospital during the same period for whom no blood culture was requested were excluded.

2.6. Variables, Data Sources, and Data Extraction

Excel 2019 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to extract the following variables from the EMR: Hospital folder number, laboratory IDs, admission date, gender, age in days at admission, birth weight in kilograms, ward admitted to (NICU, pediatric emergency), type of beneficiary (entitled/non-entitled), NS categorization (EOS/LOS), date of culture request, empirical antibiotic prescription (yes/no), date of culture report with AST, culture result (non-contaminated growth, contaminated, no growth), bacterial isolate (species and Gramme +/-), antibiotic susceptibility (sensitive or resistant), changes in prescription after blood culture report (changed/not changed), outcome of hospital discharge (discharge, death) and availability of CDST report at discharge or report and readmission within two weeks of discharge.

Duplicates were eliminated using the laboratory and hospital folder numbers. The first culture was considered for this study when a neonate received multiple blood cultures in a single admission episode. In addition, in cases where a neonate dies before culture results are available, day 4 is reported as the day of culture receipt. We de-identified the blood culture reports during data extraction to ensure complete anonymity from the laboratory archives. Readmission within two weeks was checked using the hospital folder number in the EMR. The appropriateness of the empirical treatment was assessed based on the prescribed medication compared to the hospital’s NICU guidelines.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The patient-level data in Microsoft Excel format were cleaned and imported into Jamovi software (version 2.5) for further cleaning and analysis. The dates of the culture request and the culture report (found in the EMR) were used to calculate the turnaround time (in days). The difference in TAT by hospital outcomes (died or discharged) was assessed using one-way ANOVA. Numbers and proportions were used to summarize categorical variables (culture positivity, AST, readmission, hospital exit outcomes, and empirical treatment). Variables associated with MDR and culture positivity were assessed using Chi square test and P-value<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics, Culture Turnaround Time, Report Availability, and Hospital Exit Outcomes

A total of 506 neonates with suspected sepsis underwent CDST during the study period.

Table 1 summarizes their baseline characteristics, report availability, and discharge outcomes. Most admissions occurred in 2023 (n=296; 58.5%), followed by 2022 (n=112; 22.1%) and the first half of 2024 (n=98; 19.4%). Most neonates were admitted within the first week of life (1–7 days; n=474; 93.7%), with a mean age at admission of 1.6 days (SD=4.7)

Among neonates admitted with suspected sepsis, males accounted for a slightly higher proportion than females (54.7% vs. 45.3%). Birth weight distribution showed that 273 neonates (55.3%) had normal birth weight (≥2.5 kg), 150 (30.3%) had low birth weight (1.5–2.49 kg), and 72 (14.5%) had very low birth weight (1.0–1.49 kg), with a mean birth weight of 2.5 kg (SD 0.9). Most neonates were admitted to the NICU (n=453; 89.5%), while the rest were managed in the pediatric emergency unit (n=53; 10.5%). EOS (<3 days of age) was seen in 372 cases (73.5%), whereas LOS (3–28 days) occurred in 134 cases (26.5%). No neonates were readmitted after discharge.

Almost all neonates (n=500, 98.8%) were on empirical antibiotic treatment upon admission. The most prescribed empirical treatment combination for a neonate with suspected sepsis is gentamicin (4mg/kg/24-36 hourly) and penicillin (50,000units/kg/12 hourly) 63.6% (n=318), penicillin (50,000units/kg/12 hourly) and amikacin (15mg/kg/24 hourly) 8% (n=40), ciprofloxacin (10mg/kg/12 hourly) and piperacillin-tazobactam ( 90mg/kg/8-12 hourly) 7.8% (n=39), and amikacin (15mg/kg/24 hourly) and piperacillin-tazobactam ( 90mg/kg/8-12 hourly). The median (interquartile range) TAT turnaround time for culture report was 5 (5-5) days and did not differ significantly across baseline characteristics. At discharge, 470 neonates (92.9%) were clinically fit and discharged. Of these, 324 neonates (64.0%) received their culture reports before discharge, while 146 (28.9%) received their culture reports after discharge. Of the 36 (7.1%) neonates who died in the hospital, 11 (30.5%) culture reports were available after the death (

Table 1).

3.2. Early and Late Onset Sepsis

Among the 506 neonates, EOS predominated, affecting 372 (73.5%), while LOS occurred in 134 (26.5%). The proportion of EOS rose steadily over the study period, increasing from 59.8% (n=67) in 2022 to 75.3% (n=223) in 2023 and 83.7% (n=82) in the first half of 2024 (

Table 2). EOS was more frequent in males (76.5%, n=212) than females (69.9%, n=160) and was observed in 74.0% (n=335) of NICU admissions compared with 69.8% (n=53) in the pediatric emergency unit. A slightly higher proportion was also noted among entitled neonates (76.9%, n=93) versus non-entitled neonates (72.5%, n=279).

3.3. Culture Positivity and Multidrug Resistance

Of the 506 neonates admitted with suspected sepsis, 69 (13.6%; 95% CI: 10.7–16.9) were confirmed to have sepsis by culture. Out of these, 37 (53.6%; 95% CI: 41.2–65.7) were identified as MDR. MDR was observed in 56.4% of Gram-positive isolates (22 of 39) and 50% of Gram-negative isolates (15 of 30). CoNS were predominant, among the gram-positive isolates, with 57.7% (15 of 26) demonstrating resistance to three or more antibiotic classes, as shown in

Table 3. Similarly, multidrug resistance was detected in 55.6% of S

. aureus isolates (5 of 9). Among Gram-negative isolates, MDR was observed in 42.9% of both

Klebsiella pneumoniae (6/14) and

Escherichia coli (3/7) isolates.

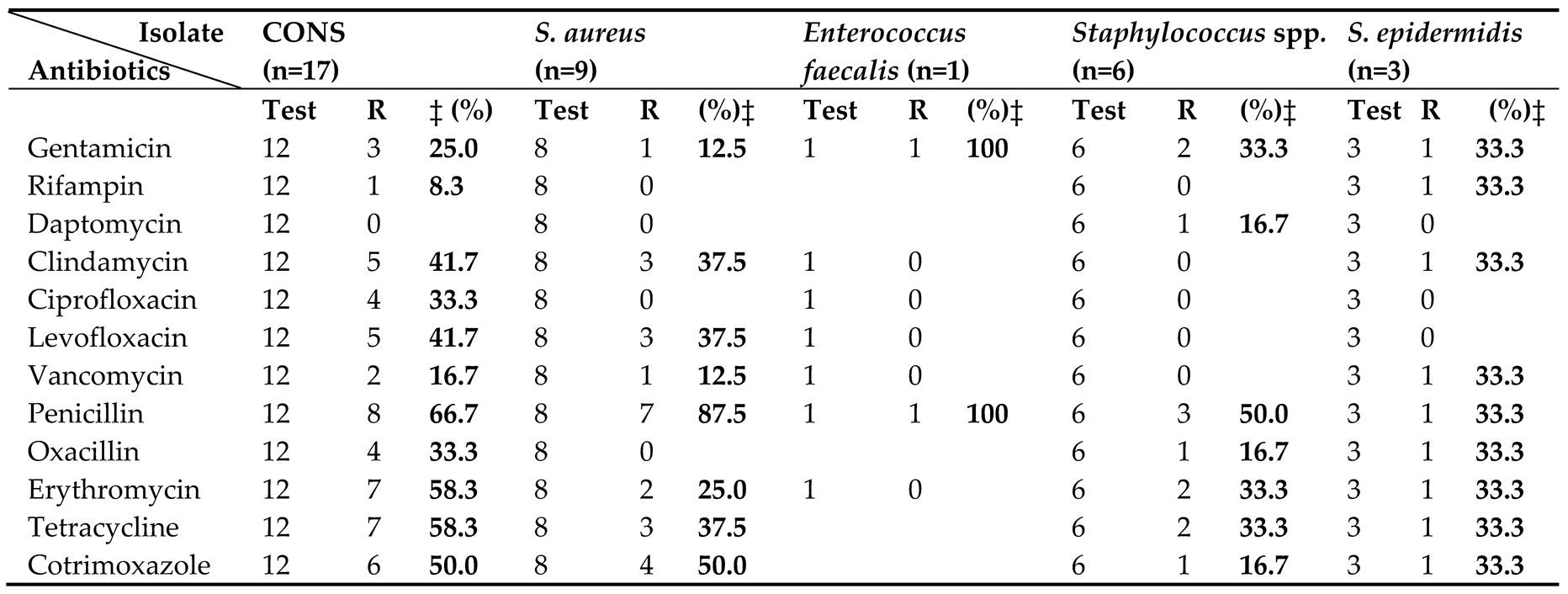

3.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of bacterial isolates from neonates with suspected sepsis. Among 36 Gram-positive isolates, CoNS were most frequent (n=17), followed by

S. aureus (n=9),

Staphylococcus spp. (n=6),

S. epidermidis (n=3), and

Enterococcus faecalis (n=1). High rates of penicillin resistance were observed across species, affecting 100% of

Enterococcus faecalis, 87.5% of

S. aureus, and 66.7% of CoNS isolates. Resistance to erythromycin was also common, and was observed in 58.3% of CoNS, 25.0% of

S. aureus, and 33.3% of both

S. epidermidis and

Staphylococcus spp. Tetracycline resistance was notable in CoNS (58.3%) and

S. aureus (37.5%).

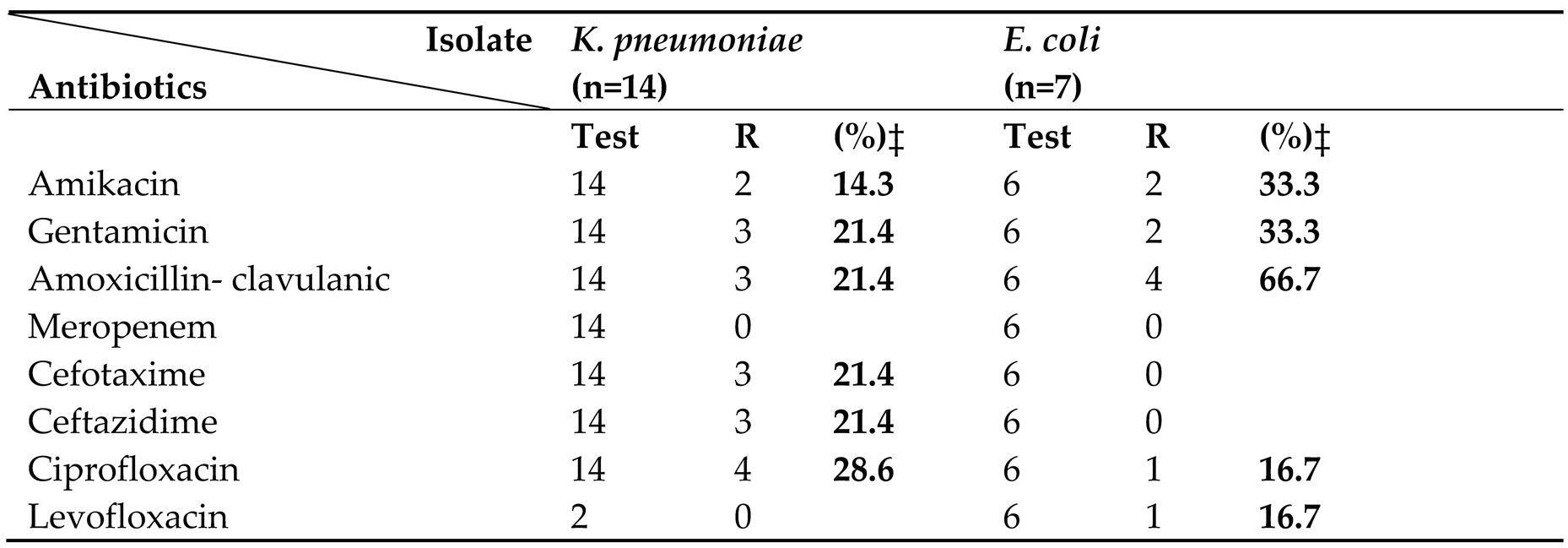

Among the 21 Gram-negative isolates, K. pneumoniae (n=14) and E. coli (n=7) predominated. Both species remained uniformly susceptible to meropenem, levofloxacin, and ceftazidime, while all E. coli isolates were fully susceptible to cefotaxime. In contrast, K. pneumoniae exhibited low-level resistance to amikacin (14.3%) and gentamicin (21.4%).

3.5. Factors Associated with Culture Positivity and Multidrug Resistance

Culture positivity varied significantly across years of admission (

p=0.001), with the highest rate observed in 2023 (17.6%), followed by the first half of 2024 (13.3%), and the lowest in 2022 (3.6%), as shown in

Table 6. Neonates admitted to the pediatric ward demonstrated a significantly higher culture positivity rate (26.4%) compared with those admitted to the NICU (12.1%) (

p=0.004). In contrast, the prevalence of multidrug resistance (MDR) did not differ significantly by ward type (

p=0.761), age group (<7 days vs. 8–28 days,

p=0.214), sex (

p=0.161), birth weight category (

p=0.750), beneficiary status (

p=0.879), sepsis classification (

p=0.709), or empirical antibiotic use at admission (

p=0.587).

Antibiotic resistance patterns are highlighted in

Table 7 across the AWaRe classification categories by the WHO. Several key antibiotics showed high resistance rates to most drugs in the Access group; these include penicillin (66.7%), gentamicin (35.3%), tetracycline (43.3%), and cotrimoxazole (41.4%). Despite this, certain antibiotics in the Watch and Reserve category, such as daptomycin (3.4%) and vancomycin (13.3%), had less resistant levels. The performance of amikacin and meropenem was excellent, with no resistance detected.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

The current study examined changes in selected indicators during 2022-2024 as a result of operational research at the 37 Military Hospital from 2017 to 2020. The key findings observed show: 1) Culture confirmation declined from 29% (2017-2020) to 13.6% (2022-2024), 2) High antibiotic and multidrug resistance.

4.2. Culture Confirmation Declined from 29% (2017-2020) to 13.6% (2022-2024),

In the present study, culture confirmation of clinical sepsis from the same study site decreased from 29% in 2017-2019 to 13.6% in 2022-2024. Low culture positivity rates in NS are attributed to several contributing factors, such as maternal antibiotic use before delivery [

16], Early antibiotic therapy before sample collection [

17], sampling outside bacteremia episodes, inherent difficulties in obtaining neonatal specimens, clinical complexity of diagnosing sepsis in newborns, and lack of specialized culture systems or expertise, particularly in resource-limited settings like Ghana [

18]. Our findings suggest that some of these factors, including maternal antibiotic use before delivery and early antibiotic therapy before sample collection, may have contributed to the low culture confirmation rate. This is evident from our findings, where majority of neonates with confirmed sepsis (14%) were classified as EOS. This pattern suggests that maternal antibiotic exposure, whether administered intrapartum or during pregnancy, may persist in the neonate, suppressing bacterial proliferation and potentially leading to underestimation of pathogen presence in culture-based diagnostics.

The most common pathogen isolated in the culture-confirmed cases was CoNS (37.5%); this finding is relatively comparable to the previous study (55%). CoNS has been implicated as one of the main etiologies of EOS among neonates, which corroborates with our findings. It may be pathogenic in very low birth weight infants [

3], however, their high isolation rates often reflect contamination rather than true infection. In the present study, the proportion of CoNS isolates aligns with previous findings, supporting the observation that while many cases may be due to contamination, the potential for true infection, particularly in vulnerable subgroups like these neonates, should not be overlooked [

19]. High rate of MDR among neonates with CoNS infections (57.7%) was recorded, slightly higher than the previous study (52%), even though lower than a study from Myanmar (70%) [

20]. This finding supports the need for improved infection prevention and control practices, including hand hygiene, aseptic techniques, disinfection, and sterilization among health care providers and mothers [

21,

20]. Similar MDR proportions (53%) were shown in a study from Ghana [

22].

4.3. Antibiotic Resistance Trends and Multidrug Resistance Among Bacterial Isolates in Neonates at 37 Military Hospital

Resistance among

S. aureus isolates in our study showed notable temporal trends. Penicillin resistance increased from 80% during 2017–2020 to 87.5% in 2022–2024, while levofloxacin resistance rose from 18% to 33.3% over the same period. In contrast, tetracycline resistance declined from 49% to 37.5%. These findings align with research findings showing a reduction in tetracycline resistance from 36% in 2010 to 12.8% in 2019 [

23], and are comparable to studies documenting lower resistance rates to tetracycline (4%) and penicillin (74%) [

24]. According to the WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS), penicillin resistance in

S. aureus has exceeded 85% in several countries as of 2022 [

25]. Similarly, a multicenter study in sub-Saharan Africa observed a marked rise in fluoroquinolone resistance, with levofloxacin resistance increasing from 20% in 2015 to over 35% by 2023 [

26]. In contrast, a study from Ethiopia reported penicillin resistance of 94.6% (35/37) among

S. aureus isolates [

27].

S. aureus also experienced an upward trend in MDR, rising from 51.1% (2017-2020) to 55.6% (2022-2024).

K. Pneumoniae, on the other hand, showed no change, maintaining a steady MDR rate of 33.3% across both study periods in our setting. However, this figure is significantly lower than a report from India, where 65.76% of

K. pneumoniae isolates were classified as multidrug-resistant. Of particular concern is the emergence of MDR in

E. coli. While no MDR was recorded during 2017-2020, the current study shows that 42.9% of

E. coli isolates now meet MDR criteria. Resistance rates in

E. coli have also increased notably: penicillin 66.7%, ciprofloxacin 33.3%, and amikacin (2nd generation) 14.3%. These findings are especially worrying, as highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) report emphasizing the rising burden of AMR in sub-Saharan Africa. Of particular concern is the increasing resistance of

S. species to last-resort antibiotics daptomycin, which has a resistance rate of 16.7%. similarly to a study from also shows resistance to carbapenems (56%), third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins (95%), and aminoglycosides (74%) [

28].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

One of the study's main strengths is that it minimizes the possibility of selection bias by providing data on all blood samples submitted for all neonates with suspected sepsis at a single hospital during the three-year study period. All patients were included in this study, regardless of payer source. The main drawback was relying on retrospective data, which limits the ability to gather additional patient and provider-specific information. We could not determine the percentage of newborns with suspected sepsis who did not undergo culture and AST because we depended on laboratory data from the EMR instead of clinical data. Additionally, this study was conducted in only one hospital, which does not give a total representation of Ghana. Finally, we were unable to analyze the proportion of neonates on antibiotics before culture samples were taken.

4.5. Recommendations

Our study has a few recommendations. Firstly, to optimize empirical therapy and preserve antibiotic efficacy, healthcare facilities should regularly review local antibiograms and implement or revise antibiotic stewardship programs guided by up-to-date, locally generated antimicrobial resistance data. We recommend standardizing clinical protocols for early-onset sepsis (EOS) cases to account for maternal antibiotic exposure that can suppress bacterial growth in neonates. Secondly, it is crucial to enhance training for neonatal and perinatal healthcare providers on best practices in infection prevention, early sepsis recognition, and rational antimicrobial prescribing. Thirdly, we must establish routine antimicrobial resistance surveillance reporting at both national and hospital levels to inform policy development and guide treatment protocols. Finally, a centralized national neonatal health database system should be developed to allow clinicians to access patient records across facilities, ensuring continuity of care, especially in cases where neonates are discharged before culture results are available.

5.0. Conclusions

Following the operational research in 2021 and after implementation of selected interventions in a tertiary care setting, there was a notable decrease in culture positivity rates and a stable mortality rate from 2017 to 2024; however, significant challenges remain in the management of neonatal sepsis at this military hospital. The prolonged turnaround times for culture results, coupled with a high rate of patient discharge before results are available, compromise evidence-based treatment decisions. The alarming prevalence of multidrug-resistant Gram-positive organisms, including CoNS, necessitates a re-evaluation of current diagnostic protocols and empirical antibiotic regimens. These findings underscore the critical need for implementing an antimicrobial stewardship program tailored to the local resistance patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D. F.K.M.T. P. C and E. A. P. Methodology, B.D. P.C. and F.K.M.T. Software, B.D. P.C. and I.A. validation, B.D. P.C. F.K.M.T. and I.A. formal analysis, B.D. P.C. and I.A. investigation, B.D. P.C. and F.K.M.T. resources, D.B. P.C. F.K.M.T. R.N.Y. O. E.A.P. and. I.A. data curation, B.D. R.N.Y.O. and I.A. writing—original draft preparation, B.D. P.C. F.K.M.T I.A. and E.A.P. writing—review and editing, B.D. P.C. F.K.M.T. and E.A.P. visualization, B.D. P.C. F.K.M.T. and I.A. supervision, B.D. E.A.P. P.C. and F.K.M.T. project administration, B.D. R.N.Y.O. and I.A.

Funding

Without any additional funding, this operational research was carried out in standard operational environments. Nonetheless, the proposal and paper were created while the principal (corresponding) author was enrolled in a SORT IT course. This SORT IT-AMR effort, known as the NIHR-TDR partnership, has received specified money from the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The dedication and assistance of numerous funders enable TDR to carry out its activities. As of July 18, 2022, the complete list of TDR donors can be seen at: https://tdr.who.int/about-us/our-donors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was received from the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease's Ethics Advisory Group (EAG) in Paris, France (EAG 17/24, dated 22 August 2024) and the Institutional Review Board of the 37 Military Hospital in Accra (37MH-IRB/NF/IPN/936/2024, dated 25 April 2025). Data gathering was preceded by obtaining administrative approvals.

Informed Consent Statement

The ethical committee(s) requested and authorized a waiver for written informed consent because the study utilized secondary data.

Data Availability Statement

The data and codebook used in this study have been shared as Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

TDR, the World Health Organization's Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, oversaw the global collaboration known as the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), which was used to carry out the research. Among the specific SORT IT program that resulted in these publications was a collaboration between TDR and the WHO Country Office in Ghana, as well as the following organizations: Medecins Sans Fron-tières—Luxembourg, Luxembourg; ICMR–National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai, India; the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; the University of Washington, USA; Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER); The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Paris and South East Asia offices; A particular thank you to the 37 Military Hospital's commander and commanding officer in Accra, Ghana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kariniotaki, C., et al., Neonatal sepsis: a comprehensive review. Antibiotics, 2024. 14(1): p. 6.

- Brotherton, H.C., Early Kangaroo mother care for mild-moderately unstable neonates<2000g in The Gambia. 2022, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Bader, R.S., et al., Identification of bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility of early-onset sepsis (EOS) among neonates in Palestinian hospitals: a retrospective observational study. BMC pediatrics, 2025. 25(1): p. 118.

- Simonsen, K.A., et al., Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014. 27(1): p. 21-47.

- Wondifraw, E.B., et al., The burden of neonatal sepsis and its risk factors in Africa. a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 2025. 25(1): p. 847.

- Raturi, A. and S. Chandran, Neonatal Sepsis: Aetiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Advances and Management Strategies. Clin Med Insights Pediatr, 2024. 18: p. 11795565241281337.

- Hassall, J., et al., Limitations of current techniques in clinical antimicrobial resistance diagnosis: examples and future prospects. npj Antimicrobials and Resistance, 2024. 2(1): p. 16.

- Vivekanandan, K.E., et al., Exploring molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in bacteria and progressions in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome expurgation solutions. Glob Med Genet, 2025. 12(2): p. 100042.

- Ferrieri, P. and L.D. Wallen, Newborn sepsis and meningitis, in Avery's Diseases of the Newborn. 2018, Elsevier. p. 553-565. e3.

- Bader, R.S., et al., Identification of bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility of early-onset sepsis (EOS) among neonates in Palestinian hospitals: a retrospective observational study. BMC Pediatrics, 2025. 25(1): p. 118.

- Tetteh, F.K.M., et al., Sepsis among Neonates in a Ghanaian Tertiary Military Hospital: Culture Results and Turnaround Times. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(18).

- Akweongo, P., et al., Insured clients out-of-pocket payments for health care under the national health insurance scheme in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 2021. 21(1): p. 440.

- Abia, A.L.K. and S.Y. Essack, Antimicrobial research and one health in Africa. 2023: Springer.

- Wilson, M.L., M.P. Weinstein, and L.B. Reller, Laboratory detection of bacteremia and fungemia. Manual of clinical microbiology, 2015: p. 15-28.

- Arman, G., et al., Frequency of microbial isolates and pattern of antimicrobial resistance in patients with hematological malignancies: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2022. 22(1): p. 146.

- Klingenberg, C., et al., Culture-negative early-onset neonatal sepsis—at the crossroad between efficient sepsis care and antimicrobial stewardship. Frontiers in pediatrics, 2018. 6: p. 285.

- Scheer, C., et al., Impact of antibiotic administration on blood culture positivity at the beginning of sepsis: a prospective clinical cohort study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2019. 25(3): p. 326-331.

- Klingenberg, C., et al., Culture-Negative Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis - At the Crossroad Between Efficient Sepsis Care and Antimicrobial Stewardship. Front Pediatr, 2018. 6: p. 285.

- Cortese, F., et al., Early and late infections in newborns: where do we stand? A review. Pediatrics & Neonatology, 2016. 57(4): p. 265-273.

- Oo, N.A.T., et al., Neonatal Sepsis, Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern, and Treatment Outcomes among Neonates Treated in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Yangon, Myanmar from 2017 to 2019. Trop Med Infect Dis, 2021. 6(2).

- Zaidi, A.K., et al., Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries. Lancet, 2005. 365(9465): p. 1175-88.

- Labi, A.-K., et al., Neonatal bloodstream infections in a Ghanaian Tertiary Hospital: Are the current antibiotic recommendations adequate? BMC Infectious Diseases, 2016. 16(1): p. 598.

- Yang, F., et al., Antimicrobial resistance and virulence profiles of staphylococci isolated from clinical bovine mastitis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2023. 14: p. 1190790.

- Congdon, S.T., et al., Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus associated with a college-aged cohort: life-style factors that contribute to nasal carriage. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2023. 13: p. 1195758.

- Organization, W.H., Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report 2022. 2022: World Health Organization.

- Gouleu, C.S., et al., Temporal trends of skin and soft tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Gabon. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control, 2024. 13(1): p. 68.

- Deress, T., et al., Bacterial profiles and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns in neonatal sepsis at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Front Microbiol, 2024. 15: p. 1461689.

- Urban-Chmiel, R., et al., Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics, 2022. 11(8): p. 1079.

Table 1.

lists the baseline characteristics, report availability, and hospital exit outcomes for neonates suspected of having sepsis who were tested for antibiotic sensitivity and culture at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, between 2022, 2023, and 2024.

Table 1.

lists the baseline characteristics, report availability, and hospital exit outcomes for neonates suspected of having sepsis who were tested for antibiotic sensitivity and culture at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, between 2022, 2023, and 2024.

| Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

| Total |

n=506 |

% |

| Year of admission |

|

|

| 2022 (January-December) |

112 |

22.1 |

| 2023 (January-December) |

585 |

58.5 |

| 2024 (January-July) |

98 |

19.4 |

| Age in days |

|

|

| 1-7 |

474 |

93.7 |

| 8-28 |

32 |

6.3 |

| Mean age (SD) in days |

1.6 |

4.7 |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

227 |

54.7 |

| Female |

229 |

45.3 |

| Birth weight in kilograms |

|

|

| Very low (1.00–1.49) |

72 |

14.5 |

| Low (1.50–2.49) |

150 |

30.3 |

| Normal (≥2.50) |

273 |

55.3 |

| Mean birth weight (SD) |

2.5 |

0.9 |

| Name of Ward |

|

|

| NICU |

453 |

89.5 |

| PEU |

53 |

10.5 |

| Type of beneficiary |

|

|

| Entitled |

121 |

23.9 |

| Non-entitled |

385 |

76.1 |

| Onset of sepsis |

|

|

| Early (<3 days) |

372 |

73.5 |

| Late (3–28 days) |

134 |

26.5 |

| Hospital exit outcome |

|

|

| Clinically fit and discharged |

470 |

92.9 |

| Died |

36 |

7.1 |

| Empirical treatment |

|

|

| On Antibiotics upon admission |

500 |

98.8 |

| Not on Antibiotics upon admission |

6 |

1.2 |

| Culture Reports (For discharged only, n=470 |

|

|

| Received report Before discharge |

324 |

64.0 |

| Received Report After discharge |

146 |

28.9 |

Table 2.

shows the baseline characteristics of neonates with culture-confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, categorized by early and late onset sepsis (2022–2024).

Table 2.

shows the baseline characteristics of neonates with culture-confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, categorized by early and late onset sepsis (2022–2024).

| Characteristics |

Total |

Early onset |

Late onset |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

n=506 |

n=372 |

73.5%

|

n=134 |

26.5%

|

| Year of admission |

| |

2022 (January-December) |

112 |

67 |

59.8 |

45 |

40.2 |

| |

2023 (January-December) |

296 |

223 |

75.3 |

73 |

24.7 |

| |

2024 (January-July) |

98 |

82 |

83.7 |

16 |

16.3 |

| Sex |

| |

Male |

277 |

212 |

76.5 |

65 |

23.5 |

| |

Female |

229 |

160 |

69.9 |

69 |

30.1 |

| Birth weight in kilograms |

| |

Very low (1.00-1.49) |

72 |

54 |

75.0 |

18 |

25.0 |

| |

Low (1.50-2.49) |

153 |

105 |

68.6 |

48 |

31.4 |

| |

Normal (≥2.50) |

273 |

208 |

76.2 |

65 |

23.8 |

| Name of ward |

| |

NICU |

453 |

335 |

74.0 |

118 |

26.0 |

| |

PEU |

53 |

37 |

69.8 |

16 |

30.2 |

| Type of beneficiary |

| |

Entitled |

121 |

93 |

76.9 |

28 |

23.1 |

| |

Non-entitled |

385 |

279 |

72.5 |

106 |

27.5 |

Table 3.

shows the multidrug resistance and culture positivity of neonates suffering from suspected sepsis who had their culture tested at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022-24).

Table 3.

shows the multidrug resistance and culture positivity of neonates suffering from suspected sepsis who had their culture tested at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022-24).

| Bacteria isolates |

Number of isolates |

MDR isolates |

Percentage |

| |

|

|

|

| Total |

n=69 |

n=37 |

53.6 |

| |

|

|

|

| Gram-positive isolates |

39 |

22 |

56.4 |

| Coagulase Negative Staphylococcus* |

26 |

15 |

57.7 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

9 |

5 |

55.6 |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

1 |

0 |

0.0 |

Gram-positive cocci

GPC in cluster

Streptococcus acidominus

|

1

1

1 |

01

1 |

0.0

100.

100 |

| |

|

|

|

| Gram-negative isolates |

30 |

15 |

50.0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

14 |

6 |

42.9 |

| Escherichia coli |

7 |

3 |

42.9 |

Gram-negative rod

Yersinai pseudotuberclosis

Shigella |

5

3

1 |

4

1

1 |

80.0

33.3

100 |

Table 4.

shows the trends of antibiotic susceptibility testing for Gram-positive isolates (n = 36) in neonates at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, who had culture-confirmed sepsis between 2022 and 2024.

Table 4.

shows the trends of antibiotic susceptibility testing for Gram-positive isolates (n = 36) in neonates at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana, who had culture-confirmed sepsis between 2022 and 2024.

Table 5.

shows Patterns of Gram-negative isolates' antibiotic susceptibility testing (n=21) in neonates with culture-confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022-24).

Table 5.

shows Patterns of Gram-negative isolates' antibiotic susceptibility testing (n=21) in neonates with culture-confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022-24).

Table 6.

lists the variables associated with MDR and culture positivity in newborns with suspected sepsis who had blood culture and antibiotic sensitivity done at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022–2024).

Table 6.

lists the variables associated with MDR and culture positivity in newborns with suspected sepsis who had blood culture and antibiotic sensitivity done at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana (2022–2024).

| Characteristics |

Total |

Bacterial yield |

Total Isolates |

MDR |

| |

|

|

(%)* |

P-value# |

|

|

(%)* |

P-value# |

| Total |

n=506 |

n=69 |

13.6 |

|

n=69 |

n=37 |

53.6 |

|

| Year of admission |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2022 (January-December) |

112 |

4 |

3.6 |

0.001 |

4 |

4 |

100 |

0.052 |

| 2023 (January-December) |

296 |

52 |

17.6 |

52 |

24 |

46.2 |

| 2024 (January-July) |

98 |

13 |

13.3 |

13 |

9 |

69.2 |

| Age in days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1-7 |

474 |

62 |

13.1 |

0.214 |

62 |

34 |

54.8 |

0.413 |

| 8-28 |

32 |

7 |

21.9 |

7 |

3 |

42.9 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

277 |

33 |

11.9 |

0.161 |

33 |

16 |

48.5 |

0.696 |

| Female |

229 |

36 |

15.7 |

36 |

21 |

58.3 |

| Birthweight in kilograms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Very low (1.00-1.49) |

72 |

12 |

13.6 |

0.750 |

12 |

6 |

50 |

0.792 |

| Low (1.50-2.49 |

153 |

37 |

13.6 |

20 |

12 |

60 |

| Normal ≥ 2.50 |

273 |

20 |

16.7 |

37 |

19 |

51.4 |

| Ward name |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NICU |

453 |

55 |

12.1 |

0.004 |

55 |

30 |

54.5 |

0.761 |

| PEU |

53 |

14 |

26.4 |

14 |

7 |

50 |

| Type of beneficiaries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Entitled |

121 |

17 |

14.0 |

0.879 |

17 |

8 |

47.1 |

0.532 |

| Non-entitled |

385 |

52 |

13.5 |

52 |

29 |

55.8 |

| Categories of sepsis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Early onset |

372 |

52 |

14.0 |

0.709 |

52 |

29 |

55.8 |

0.532 |

| Late onset |

134 |

17 |

12.7 |

17 |

8 |

47.1 |

| Empirical treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On antibiotic |

500 |

68 |

13.6 |

0.587 |

68 |

37 |

54.4 |

0.279 |

| Not on antibiotics |

6 |

1 |

16.7 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Table 7.

shows the resistance of isolates to antibiotics, stratified by AWaRe category, among Neonates with confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital, Accra, Ghana (2022-2024).

Table 7.

shows the resistance of isolates to antibiotics, stratified by AWaRe category, among Neonates with confirmed sepsis at the 37 Military Hospital, Accra, Ghana (2022-2024).

| Classes of Antibiotics |

Antibiotics |

AWaRe Category |

Test |

Resistance |

| |

|

|

N |

n (%) |

| Aminoglycosides |

Amikacin |

Access |

20 |

4 (0.0) |

| Aminoglycosides |

Gentamicin |

Access |

50 |

13 (35.3) |

| Beta-lactams Beta-lactamase inhibitor |

Amoxicillin- clavulanic |

Access |

20 |

7 (35.0) |

| Carbapenems |

Meropenem |

Watch |

20 |

0 (0.0) |

| Cephalosprins-3nd Generation |

Cefotaxime |

Watch |

50 |

7 (14.0) |

| Fluoroquinolones |

Ciprofloxacin |

Watch |

20 |

5 (25.0) |

| Fluoroquinolones |

Levofloxacin |

Access |

8 |

1 (12.5) |

| Glycopeptides |

Vancomycin |

Watch |

30 |

4 (13.3) |

| Penicillin |

Penicillin |

Access |

30 |

20 (66.7) |

| Penicillin |

Oxacillin |

Access |

29 |

4 (13.8) |

| Macrolides |

Erythromycin |

Watch |

30 |

4 (13.3) |

| Tetracyclines |

Tetracycline |

Access |

30 |

4 (13.3) |

| Sulfonamides |

Cotrimoxazole |

Access |

29 |

12 (41.4) |

| Lipopeptide |

Daptomycin |

Reserve |

29 |

1 (3.4) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).