Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Evidence Base

2.2. ESC-DAG Protocol Application

2.3. Conceptual Framework and Quality Assurance

3. Results

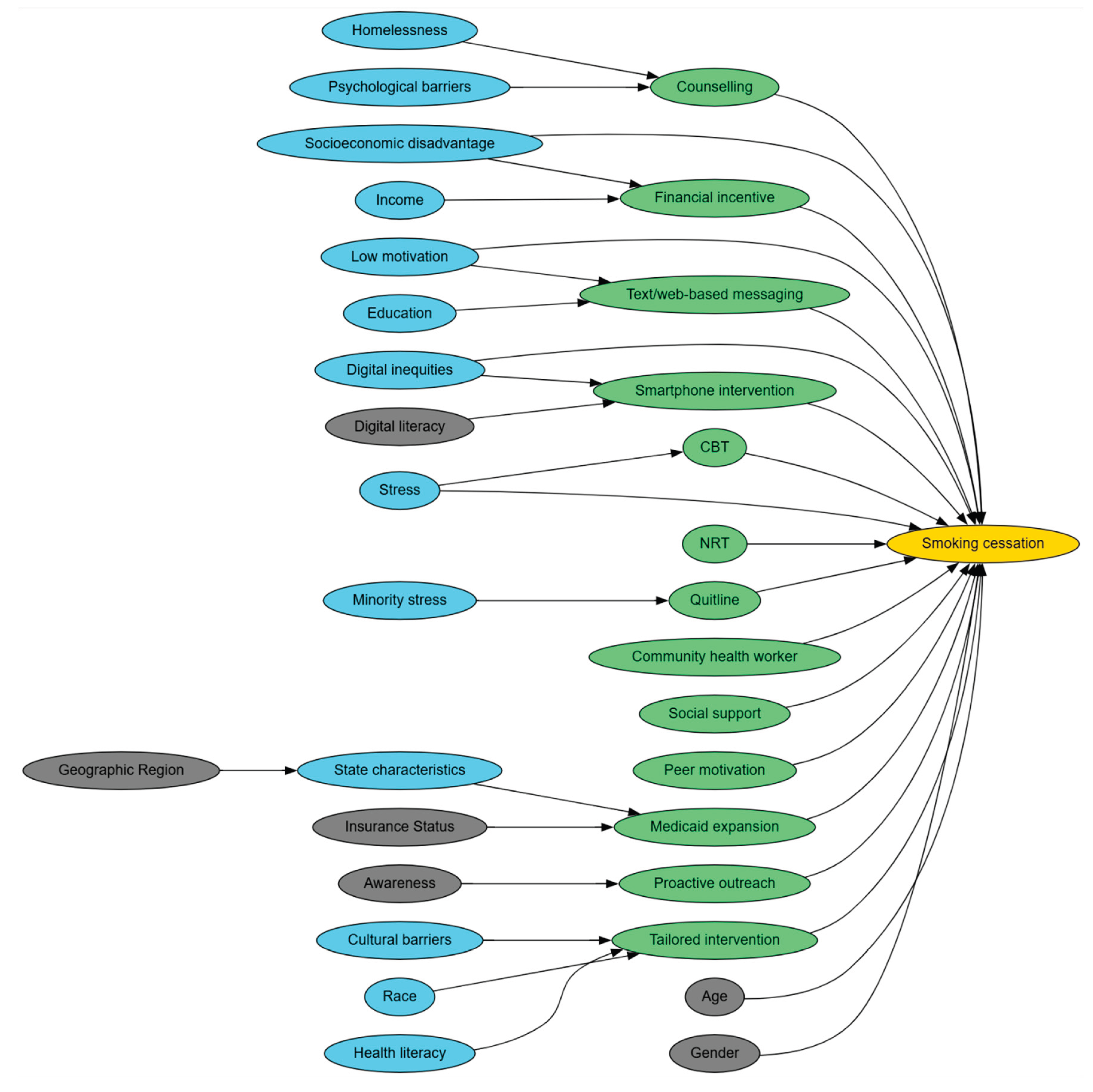

3.1. Mapping Stage Findings

3.2. Translation Stage Synthesis

3.3. Integrated DAG

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of DAG Structures

4.2. Methodological Contributions

4.3. Policy and Practice Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

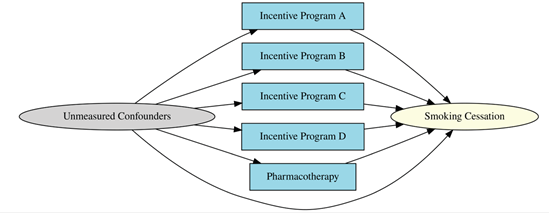

| Study citation number | Edge originates | Edge terminates | Bi directional |

|---|---|---|---|

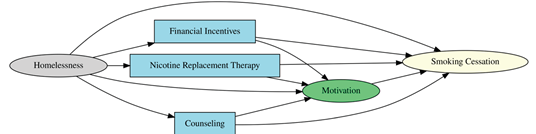

| 23 | Homelessness | Smoking cessation | No |

| Homelessness | Financial incentive | No | |

| Homelessness | NRT | No | |

| Homelessness | Motivation | No | |

| Homelessness | Counselling | No | |

| Financial incentive | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Financial incentive | Motivation | No | |

| NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT | Motivation | No | |

| Counselling | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Counselling | Motivation | No | |

| 12 | State characteristics | Smoking cessation | No |

| State characteristics | Expanded treatment coverage | No | |

| State characteristics | ACA medicaid expansion policy | No | |

| Pre-expansion insurance coverage | ACA medicaid expansion policy | No | |

| Pre-expansion insurance coverage | Expanded treatment coverage | No | |

| Pre-expansion insurance coverage | Smoking cessation | No | |

| ACA medicaid expansion policy | Expanded treatment coverage | No | |

| ACA medicaid expansion policy | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Expanded treatment coverage | Smoking cessation | No | |

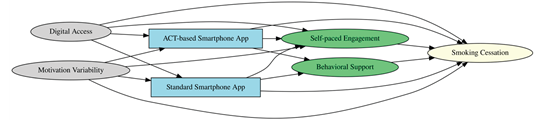

| 31 | Digital Access | Smoking cessation | No |

| Digital Access | Self paced engagement | No | |

| Digital Access | ACT based smartphone app | No | |

| Digital Access | Standard smartphone app | No | |

| Motivation variability | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Motivation variability | Self paced engagement | No | |

| Motivation variability | ACT based smartphone app | No | |

| Motivation variability | Standard smartphone app | No | |

| ACT based smartphone app | Smoking cessation | No | |

| ACT based smartphone app | Self paced engagement | No | |

| ACT based smartphone app | Behavioral support | No | |

| Standard smartphone app | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Standard smartphone app | Self paced engagement | No | |

| Standard smartphone app | Behavioral support | No | |

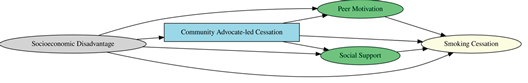

| 8 | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Smoking cessation | No |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Social support | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Community led cessation | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Peer motivation | No | |

| Community led cessation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Community led cessation | Social support | No | |

| Community led cessation | Peer motivation | No | |

| Social support | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Peer motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

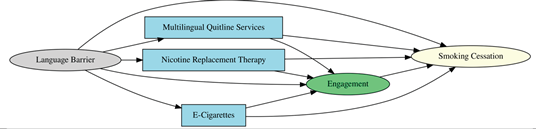

| 24 | Language barrier | Smoking cessation | No |

| Language barrier | Multilingual quitline service | No | |

| Language barrier | NRT | No | |

| Language barrier | Engagement | No | |

| Language barrier | E-cigarrettes | No | |

| Multilingual quitline service | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Multilingual quitline service | Engagement | No | |

| NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT | Engagement | No | |

| E-cigarrettes | Smoking cessation | No | |

| E-cigarrettes | Engagement | No | |

| Engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 36 | Low motivation | Smoking cessation | No |

| Low motivation | Brief community intervention | No | |

| Low motivation | Community support | No | |

| Brief community intervention | Community support | No | |

| Brief community intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Community support | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 37 | Household smoking exposure | Indoor smoking restrictions | No |

| Household smoking exposure | Behavioral counselling | No | |

| Household smoking exposure | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Behavioral counselling | Indoor smoking restrictions | No | |

| Behavioral counselling | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Indoor smoking restrictions | Smoking cessation | No | |

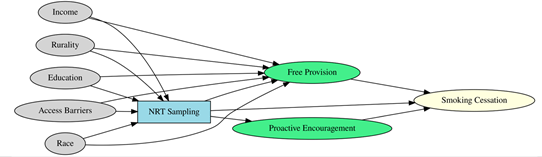

| 40 | Income | Free provision | No |

| Income | NRT sampling | No | |

| Rurality | Free provision | No | |

| Rurality | NRT sampling | No | |

| Education | Free provision | No | |

| Education | NRT sampling | No | |

| Access Barriers | Free provision | No | |

| Access Barriers | NRT sampling | No | |

| Race | Free provision | No | |

| Race | NRT sampling | No | |

| NRT sampling | Free provision | No | |

| NRT sampling | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT sampling | Proactive encouragement | No | |

| Free provision | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Proactive encouragement | Smoking cessation | No | |

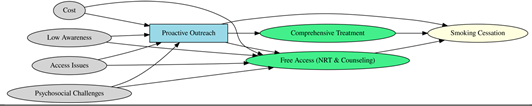

| 41 | Cost | Proactive outreach | No |

| Cost | Free NRT and counselling access | No | |

| Low awareness | Proactive outreach | No | |

| Low awareness | Free NRT and counselling access | No | |

| Access issues | Proactive outreach | No | |

| Access issues | Free NRT and counselling access | No | |

| Psychosocial challenges | Proactive outreach | No | |

| Psychosocial challenges | Free NRT and counselling access | No | |

| Proactive outreach | Free NRT and counselling access | No | |

| Proactive outreach | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Proactive outreach | Comprehensive treatment | No | |

| Free NRT and counselling access | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Comprehensive treatment | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 42 | Stress | Smoking cessation | No |

| Stress | Clinic support | No | |

| Stress | Medication | No | |

| Stress | Public housing tobacco clinic | No | |

| Socioeconomic status | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Socioeconomic status | Clinic support | No | |

| Socioeconomic status | Medication | No | |

| Socioeconomic status | Public housing tobacco clinic | No | |

| Medication | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Medication | Clinic support | No | |

| Public housing tobacco clinic | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Public housing tobacco clinic | Clinic support | No | |

| Clinic support | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 38 | Low Motivation | Mobile engagement | No |

| Low Motivation | Vaping cessation text messaging | No | |

| Low Motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Vaping cessation text messaging | Mobile engagement | No | |

| Vaping cessation text messaging | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Mobile engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 27 | Minority stress and stigma | Smoking cessation | No |

| Minority stress and stigma | Web and text based intervention | No | |

| Web and text based intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

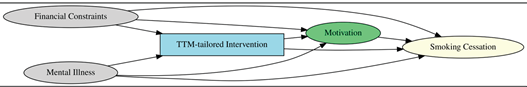

| 33 | Financial constraints | TTM tailored intervention | No |

| Financial constraints | Motivation | No | |

| Financial constraints | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Mental illness | TTM tailored intervention | No | |

| Mental illness | Motivation | No | |

| Mental illness | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 10 | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Smoking cessation | No |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Best practice | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Financial incentive | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | NRT | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Motivation | No | |

| Best practice | Motivation | No | |

| Best practice | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Financial incentive | Motivation | No | |

| Financial incentive | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT | Motivation | No | |

| NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

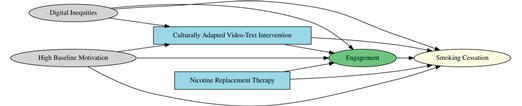

| 25 | Digital inequities | Culturally adapted video text intervention | No |

| Digital inequities | Engagement | No | |

| Digital inequities | Smoking cessation | No | |

| High baseline motivation | Culturally adapted video text intervention | No | |

| High baseline motivation | Engagement | No | |

| High baseline motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Culturally adapted video text intervention | Engagement | No | |

| Culturally adapted video text intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT | Engagement | No | |

| NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 26 | Education | Smoking cessation | No |

| Race | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Daily smoking | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Education | Text based cessation | No | |

| Race | Text based cessation | No | |

| Daily smoking | Text based cessation | No | |

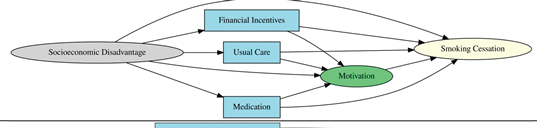

| 39 | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Smoking cessation | No |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Financial incentive | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Usual care | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Motivation | No | |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | Medication | No | |

| Financial incentive | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Usual care | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Medication | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Financial incentive | Motivation | No | |

| Usual care | Motivation | No | |

| Medication | Motivation | No | |

| Motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

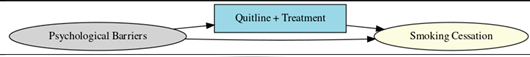

| 28 | Psychological barriers | Quitline plus treatment | No |

| Psychological barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Quitline plus treatment | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 44 | Smartphone based financial incentive | Smoking cessation | No |

| Incentive engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Smartphone based financial incentive | Incentive engagement | No | |

| 11 | Provider engagement | Cessation advice reciept | No |

| Provider engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Cessation advice reciept | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 43 | Psychological stress | Smoking cessation | No |

| Psychological stress | Cognitive behavioral counselling | No | |

| Psychological stress | Stress reduction | No | |

| 35 | Low motivation | Motivational support | No |

| Low motivation | Tailored mobile messaging | No | |

| Low motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Tailored mobile messaging | Motivational support | No | |

| Tailored mobile messaging | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Motivational support | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 34 | Behavioral health condition | Community based cessation program | No |

| Behavioral health condition | Integrated treatment services | No | |

| Behavioral health condition | Medication(NRT/other) | No | |

| Behavioral health condition | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Community based cessation program | Integrated treatment services | No | |

| Medication(NRT/other) | Integrated treatment services | No | |

| Community based cessation program | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Medication(NRT/other) | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Integrated treatment services | Smoking cessation | No | |

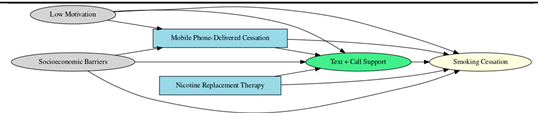

| 29 | Low motivation | Mobile phone delivered cessation | No |

| Low motivation | Text plus call support | No | |

| Low motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Socioeconomic barriers | Mobile phone delivered cessation | No | |

| Socioeconomic barriers | Text plus call support | No | |

| Socioeconomic barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Mobile phone delivered cessation | Text plus call support | No | |

| Mobile phone delivered cessation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| NRT | Text plus call support | No | |

| NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Text plus call support | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 30 | Digital literacy barriers | Personalized engagement | No |

| Digital literacy barriers | Tailored text and web intervention | No | |

| Digital literacy barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Tailored text and web intervention | Personalized engagement | No | |

| Tailored text and web intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Personalized engagement | Smoking cessation | No | |

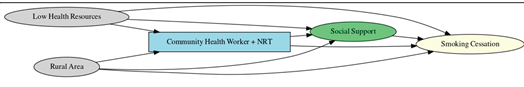

| 32 | Low health resource | Community health worker plus NRT | No |

| Low health resource | Social support | No | |

| Low health resource | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Rurality | Community health worker plus NRT | No | |

| Rurality | Social support | No | |

| Rurality | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Community health worker plus NRT | Social support | No | |

| Community health worker plus NRT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Social support | Smoking cessation | No | |

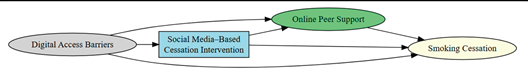

| 45 | Digital access barriers | Social media based cessation intervention | No |

| Digital access barriers | Online peer support | No | |

| Digital access barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Social media based cessation intervention | Online peer support | No | |

| Social media based cessation intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Online peer support | Smoking cessation | No | |

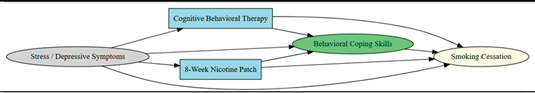

| 9 | Stress | CBT | No |

| Stress | Behavioral coping skills | No | |

| Stress | 8 week nicotine patch | No | |

| Stress | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Depressive symptoms | CBT | No | |

| Depressive symptoms | Behavioral coping skills | No | |

| Depressive symptoms | 8 week nicotine patch | No | |

| Depressive symptoms | Smoking cessation | No | |

| CBT | Behavioral coping skills | No | |

| CBT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 8 week nicotine patch | Behavioral coping skills | No | |

| 8 week nicotine patch | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Behavioral coping skills | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 46 | Access barriers | EHR enabled smoking treatment program | No |

| Access barriers | Automated provider prompts | No | |

| Access barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| EHR enabled smoking treatment program | Automated provider prompts | No | |

| EHR enabled smoking treatment program | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Automated provider prompts | Smoking cessation | No | |

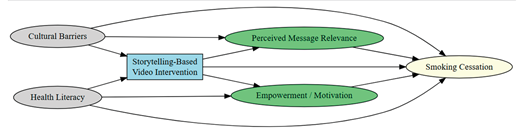

| 47 | Cultural barriers | Smoking cessation | No |

| Cultural barriers | Percieved message relevance | No | |

| Cultural barriers | Storytelling based video intervention | No | |

| Health literacy | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Health literacy | Storytelling based video intervention | No | |

| Health literacy | Motivation | No | |

| Storytelling based video intervention | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Storytelling based video intervention | Percieved message relevance | No | |

| Storytelling based video intervention | Motivation | No | |

| Percieved message relevance | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

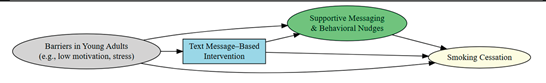

| 14 | Stress | Supportive messaging and behavioral nudges | No |

| Stress | Text based cessation | No | |

| Stress | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Low motivation | Supportive messaging and behavioral nudges | No | |

| Low motivation | Text based cessation | No | |

| Low motivation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Text based cessation | Supportive messaging and behavioral nudges | No | |

| Text based cessation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Supportive messaging and behavioral nudges | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 13 | Cultural barriers | Acceptance of sensations, emotions, and thoughts | No |

| Cultural barriers | ACT based indigenous tailored app | No | |

| Cultural barriers | Smoking cessation | No | |

| ACT based indigenous tailored app | Acceptance of sensations, emotions, and thoughts | No | |

| ACT based indigenous tailored app | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Acceptance of sensations, emotions, and thoughts | Smoking cessation | No | |

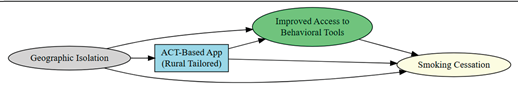

| 48 | Geographic isolation | Improved access to behaviorla tools | No |

| Geographic isolation | ACT based rural tailored app | No | |

| Geographic isolation | Smoking cessation | No | |

| ACT based rural tailored app | Improved access to behaviorla tools | No | |

| ACT based rural tailored app | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Improved access to behaviorla tools | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 49 | Depression and stress | CBT | No |

| Depression and stress | Improved coping skills | No | |

| Depression and stress | 8 week nicotine patch | No | |

| Depression and stress | Smoking cessation | No | |

| CBT | Improved coping skills | No | |

| 8 week nicotine patch | Improved coping skills | No | |

| CBT | Smoking cessation | No | |

| 8 week nicotine patch | Smoking cessation | No | |

| Improved coping skills | Smoking cessation | No |

References

- Leventhal AM, Dai H, Higgins ST. Smoking Cessation Prevalence and Inequalities in the United States: 2014-2019. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 19];114:381.

- Maki KG, Volk RJ. Disparities in Receipt of Smoking Cessation Assistance Within the US. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 19];5:e2215681–e2215681. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2792846.

- LAPOINT DN, QUIGLEY B, MONEGRO AF. HEALTH CARE DISPARITIES AND SMOKING CESSATION COUNSELING: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY ON URBAN AND NON-URBAN POPULATIONS. Chest [Internet]. Elsevier BV; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 19]. p. A6390. Available online: https://journal.chestnet.org/action/showFullText?pii=S0012369223051565.

- VanFrank B, Malarcher A, Cornelius ME, Schecter A, Jamal A, Tynan M. Adult Smoking Cessation — United States, 2022 [Internet]. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Centers for Disease Control MMWR Office; 2024 Jul. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7329a1.

- Goodin A, Talbert J, Freeman PR, Hahn EJ, Fallin-Bennett A. Appalachian disparities in tobacco cessation treatment utilization in Medicaid. Subst Abus Treat Prev Policy [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 19];15:1–6. Available online: https://substanceabusepolicy.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13011-020-0251-0.

- Sultana S, Inungu J, Jahanfar S. Barriers and Facilitators of Tobacco Cessation Interventions at the Population and Healthcare System Levels: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2025, Vol 22, Page 825 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 30];22:825. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/22/6/825/htm.

- Patel N, Karimi SM, Little B, Egger M, Antimisiaris D. Applying Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs to Identify Causal Pathways Affecting U.S. Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment Receipt and Overall Survival. Ther 2024, Vol 1, Pages 64-94 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 12];1:64–94. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2813-9909/1/2/8/htm.

- Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48.

- Ferguson KD, McCann M, Katikireddi SV, Thomson H, Green MJ, Smith DJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for constructing directed acyclic graphs (ESC-DAGs): a novel and systematic method for building directed acyclic graphs. Int J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 22];49:322. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7124493/.

- Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, Liśkiewicz M, Ellison GT. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package “dagitty.” Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1887–94.

- Aday LA, Begley CE, Larison DR, Slater CH, Richard AJ, Montoya ID. A framework for assessing the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of behavioral healthcare - PubMed. Am J Manag Care [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2025 May 7];5:25–44. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10538859/.

- Baggett TP, Chang Y, Yaqubi A, McGlave C, Higgins ST, Rigotti NA. Financial Incentives for Smoking Abstinence in Homeless Smokers: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2018;20:1442–50.

- Bailey SR, Marino M, Ezekiel-Herrera D, Schmidt T, Angier H, Hoopes MJ, et al. Tobacco Cessation in Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion States Versus Non-expansion States. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2020;22:1016–22.

- Bricker JB, Santiago-Torres M, Mull KE, Sullivan BM, David SP, Schmitz J, et al. Do medications increase the efficacy of digital interventions for smoking cessation? Secondary results from the iCanQuit randomized trial. ADDICTION. 2024;119:664–76.

- Brooks DR, Burtner JL, Borrelli B, Heeren TC, Evans T, Davine JA, et al. Twelve-Month Outcomes of a Group-Randomized Community Health Advocate-Led Smoking Cessation Intervention in Public Housing. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2018;20:1434–41.

- Chen C, Anderson CM, Babb SD, Frank R, Wong S, Kuiper NM, et al. Evaluation of the Asian Smokers’ Quitline: A Centralized Service for a Dispersed Population. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60:S154–62.

- Christiansen BA, Reeder KM, TerBeek EG, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Motivating Low Socioeconomic Status Smokers to Accept Evidence-Based Smoking Cessation Treatment: A Brief Intervention for the Community Agency Setting. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2015;17:1002–11.

- Collins BN, Nair US, Davis SM, Rodriguez D. Increasing Home Smoking Restrictions Boosts Underserved Moms’ Bioverified Quit Success. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43:50–6.

- Dahne J, Wahlquist AE, Smith TT, Carpenter MJ. The di fferential impact of nicotine replacement therapy sampling on cessation outcomes across established tobacco disparities groups. Prev Med (Baltim). 2020;136.

- Fu SS, van Ryn M, Nelson D, Burgess DJ, Thomas JL, Saul J, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: a randomised clinical trial. Thorax [Internet]. 2016;71:446–53. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatos P, Soybel A, Jassal M, Cruz SAP, Spartin C, Shaw K, et al. Tobacco treatment clinics in urban public housing: feasibility and outcomes of a hands-on tobacco dependence service in the community. BMC Public Health. 2021;21.

- Graham AL, Papandonatos GD, Cha S, Erar B, Amato MS. Improving Adherence to Smoking Cessation Treatment: Smoking Outcomes in a Web-based Randomized Trial. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52:331–41.

- Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, Saulsgiver K, Harhay MO, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2015;372:2108–17. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L604555159&from=export.

- Heffner JL, Mull KE, Watson NL, McClure JB, Bricker JB. Long-Term Smoking Cessation Outcomes for Sexual Minority Versus Nonminority Smokers in a Large Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Web-Based Interventions. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2020;22:1596–604.

- Hickman III NJ, Delucchi KL, Prochaska JJ. Treating Tobacco Dependence at the Intersection of Diversity, Poverty, and Mental Illness: A Randomized Feasibility and Replication Trial. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2015;17:1012–21.

- Higgins ST, Plucinski S, Orr E, Nighbor TD, Coleman SRM, Skelly J, et al. Randomized clinical trial examining financial incentives for smoking cessation among mothers of young children and possible impacts on child secondhand smoke exposure. Prev Med (Baltim). 2023;176.

- Hooper MW, Miller DB, Saldivar E, Mitchell C, Johnson L, Burns M, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial Testing a Video-Text Tobacco Cessation Intervention Among Economically Disadvantaged African American Adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 2021;35:769–77.

- Kamke K, Grenen E, Robinson C, El-Toukhy S. Dropout and Abstinence Outcomes in a National Text Messaging Smoking Cessation Intervention for Pregnant Women, SmokefreeMOM: Observational Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth [Internet]. 2019;7:e14699. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L629551580&from=export.

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Frank-Pearce SG, Waring JJC, Chen S, Hebert ET, et al. Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Adults A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw OPEN. 2024;7.

- Kerkvliet JL, Wey H, Fahrenwald NL. Cessation Among State Quitline Participants with a Mental Health Condition. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2015;17:735–41.

- Kurti AN, Tang K, Bolivar HA, Evemy C, Medina N, Skelly J, et al. Smartphone-based financial incentives to promote smoking cessation during pregnancy: A pilot study. Prev Med (Baltim). 2020;140.

- Lee J, Contrera Avila J, Ahluwalia JS. Differences in cessation attempts and cessation methods by race/ethnicity among US adult smokers, 2016–2018. Addict Behav [Internet]. 2023;137. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L2020808761&from=export.

- Lee M, Miller SM, Wen K-Y, Hui SA, Roussi P, Hernandez E. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to promote smoking cessation for pregnant and postpartum inner city women. J Behav Med. 2015;38:932–43.

- Mays D, Johnson AC, Phan L, Sanders C, Shoben A, Tercyak KP, et al. Tailored Mobile Messaging Intervention for Waterpipe Tobacco Cessation in Young Adults: A Randomized Trial. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2021;111:1686–95. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L636002421&from=export.

- Meernik C, McCullough A, Ranney L, Walsh B, Goldstein AO. Evaluation of Community-Based Cessation Programs: How Do Smokers with Behavioral Health Conditions Fare? Community Ment Health J. 2018;54:158–65.

- Vidrine JI, Sutton SK, Wetter DW, Shih Y-CT, Ramondetta LM, Elting LS, et al. Efficacy of a Smoking Cessation Intervention for Survivors of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Cervical Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2779-+.

- Wewers ME, Shoben A, Conroy S, Curry E, Ferketich AK, Murray DM, et al. Effectiveness of Two Community Health Worker Models of Tobacco Dependence Treatment Among Community Residents of Ohio Appalachia. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2017;19:1499–507.

- Lyu JC, Meacham MC, Nguyen N, Ramo D, Ling PM. Factors Associated With Abstinence Among Young Adult Smokers Enrolled in a Real-world Social Media Smoking Cessation Program. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2024;26:S27–35.

- Hooper MW, Calixte-Civil P, Verzijl C, Brandon KO, Asfar T, Koru-Sengul T, et al. ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN PERCEIVED RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AND TOBACCO CESSATION AMONG DIVERSE TREATMENT SEEKERS. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:411–20.

- McCarthy DE, Baker TB, Zehner ME, Adsit RT, Kim N, Zwaga D, et al. A comprehensive electronic health record-enabled smoking treatment program: Evaluating reach and effectiveness in primary care in a multiple baseline design. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet]. 2022;165. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L2018636055&from=export.

- Kreuter MW, Garg R, Fu Q, Caburnay C, Thompson T, Roberts C, et al. Helping low-income smokers quit: findings from a randomized controlled trial comparing specialized quitline services with and without social needs navigation. Lancet Reg Heal - Am [Internet]. 2023;23. Available online: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L2025307733&from=export.

- Santiago-Torres M, Mull KE, Sullivan BM, Ferketich AK, Bricker JB. Efficacy of an acceptance and commitment therapy-based smartphone application for helping rural populations quit smoking: Results from the iCanQuit randomized trial. Prev Med (Baltim). 2022;157.

- Santiago-Torres M, Mull KE, Sullivan BM, Kwon DM, Henderson PN, Nelson LA, et al. Efficacy and Utilization of Smartphone Applications for Smoking Cessation Among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Results From the iCanQuit Trial. NICOTINE Tob Res. 2022;24:544–54.

- Webb Hooper M, Kolar SK. Distress, race/ethnicity and smoking cessation in treatment-seekers: implications for disparity elimination. ADDICTION. 2015;110:1495–504.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).