1. Introduction

Globally, 1 in 3 women have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime (WHO, 2021). In Kazakhstan, according to the World Bank (2023), 27% of women experienced IPV in 2023. A survey of women conducted between 2019-2022 among 14,342 respondents who applied to the Center for Forensic Examinations of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan found that 78% of respondents had experienced physical violence, 21% psychological violence, 16% sexual and physical violence, and 6% regular sexual violence (Mussabekova, Mkhitaryan, and Abdikadirova 2024). In 2022, 61,277 cases of IPV were reported in the country (Kemelova 2023).

Several key risk factors drive IPV among vulnerable populations globally and in Kazakhstan. At the individual level, lower education levels (L. J. Brown et al. 2023),(Gunarathne et al. 2023) young age at marriage, and childhood exposure to violence(Organization 2021),(Sabri and Young 2022), are associated with increased risk of IPV victimization(Murphy et al. 2021),(Mannell et al. 2022),(L. J. Brown et al. 2023). Substance abuse, particularly alcohol use by perpetrators, is strongly linked to IPV perpetration (Murphy et al. 2021),(Mannell et al. 2022),(Sabri and Young 2022). Mental health issues, such as depression during the perinatal period, are also associated with higher rates of IPV victimization (Mojahed et al. 2024). Relationship and family-level factors play a crucial role. Economic stress within households, including unemployment of male partners (Sabri and Young 2022), is linked to increased IPV rates (Gunarathne et al. 2023),(Murphy et al. 2021),(Mannell et al. 2022).

Traditional gender norms promoting male dominance and female subservience (Organization 2021), as well as acceptance of violence against women as normal or justified(Sabri and Young 2022), contribute to high IPV rates. In Kazakhstan specifically, over 93% of citizens hold gender biases against women (e.g., beliefs that women are intellectually inferior and should be considered property of the their husbands), which may contribute to the high prevalence of IPV (Kemelova 2023). At the community and societal levels, weak community sanctions against IPV, such as neighbors' unwillingness to intervene, enable violence( Murphy et al. 2021). Lack of social support and isolation increase women's vulnerability to IPV (Murphy et al. 2021).

On April 15, 2024, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed a landmark law criminalizing domestic violence and reintroducing criminal penalties for battery and minor bodily harm (Kemelova 2024). The new law improves Kazakhstan legislation but further reforms are needed to bring it to international standards (“Kazakhstan: New Law to Protect Women Improved, but Incomplete | Human Rights Watch” 2024),(“Kazakhstan’s New Domestic Violence Law Is Welcome but Further Reforms Need to Close Remaining Protection Gaps - Kazakhstan | ReliefWeb” 2024). In 2024, approximately 100,000 cases of domestic abuse were reported to the police, resulting in 72,000 protection orders issued and 16,000 court verdicts (“Kazakhstan’s Year in Review: Prevention of Domestic Abuse, Protection of Women’s & Children’s Rights - The Astana Times,” n.d.). The country has also expanded its network of crisis centers, with 69 such institutions now operational. These centers have provided support to 5,500 women, including 3,700 with children, since the beginning of 2024 (“Kazakhstan’s Year in Review: Prevention of Domestic Abuse, Protection of Women’s & Children’s Rights - The Astana Times,” n.d.) However, crisis centers in Kazakhstan often operate inefficiently and struggle to comply with international human rights standards of adequate service delivery provided to survivors. Further, these centers are not able to sufficiently address the number of women in need (“What’s Wrong with Women’s Crisis Centres in Kazakhstan? - CABAR.Asia,” n.d.). Also, most shelters do not admit women from key affected populations (KAPs), including those living with HIV (“HIV Status: Challenges That Women Face | United Nations Development Programme,” n.d.) with substance use issues, those released from prison (“HIV Status: Challenges That Women Face | United Nations Development Programme,” n.d.), transgender women (Muyanga et al. 2023),(Kurdyla, Messinger, and Ramirez 2021), and/or women engaged in sex work(Mukherjee et al. 2023),(Witte et al. 2023)

Women from KAPs face disproportionate risks of IPV and systemic barriers to accessing support services. Globally, IPV estimates among women from key populations are subject to under-reporting and measurement error due to gaps in surveillance, criminalization of risk behaviors, stigmatization, homicides, non-representative data collection methods, publication bias, and poor reliability of IPV measurement tools (El-Bassel et al. 2022). Yet, a meta-analysis published in 2022 among women from KAPs reports a 23-75% prevalence of IPV, which is much higher than in the general population (El-Bassel et al. 2022). Another meta-analysis showed transgender individuals were 1.7 times more likely to experience any IPV, 2.2 times more likely to experience physical IPV, and 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual IPV, compared with cisgender individuals (Peitzmeier et al. 2020). In Kazakhstan, in one of our studies among women who exchange sex for money or drugs, 45% reported experiencing IPV, and 28% experienced violence from non-intimate partners in the past 90 days, respectively (Mukherjee et al. 2023). Another study among HIV-positive women reported a prevalence of 52% for lifetime IPV and 30% for non-partner violence (Jiwatram-Negrón et al. 2018). There are no studies reporting estimates of IPV among transgender individuals in Kazakhstan; this lack of data alone highlights the need to understand and address the needs of this KAP.

Several multi-level structural community and organizational factors may explain the lack of an effective coordinated response to the IPV epidemics among different KAPs of women in Kazakhstan. First is the lack of surveillance timely data on IPV among KAPs of women who are routinely excluded from national household surveys. Gaining access to real-time data on different types of IPV among marginalized groups of women is critical to understanding and documenting the scope of the epidemic and identifying “hotspots’ and high-burden communities where IPV is likely to occur. Such data are vital for guiding a continuum of evidence-based IPV prevention and treatment initiatives. Second is the lack of integration or coordination between mainstream IPV providers (e.g., crisis shelters), emergency responders (e.g. police, emergency departments), and providers of services for marginalized populations of women (e.g. harm reduction programs, drug treatment programs, services for sex workers, HIV care clinics). Third is the widespread community-level and IPV provider-level discrimination and stigma against these populations of marginalized women who too often are blamed for the violence they experience because they have used drugs or engaged in sex work. Finally, there is a lack of effective community engagement of key stakeholders who may work together and mobilize resources to identify and address gaps in IPV services for women from KAPs with effective policies and programs.

This study was designed to address these gaps in services for marginalized women in Kazakhstan and Central Asia by implementing an innovative one-session IPV Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment/Services (SBIRT) mHealth intervention (UMAI-WINGS) using a robust community-engaged approach. This study evaluates the implementation and outcomes of the UMAI intervention that was adapted from the evidence-based WINGS IPV SBIRT intervention (Gilbert et al. 2016),(Gilbert et al. 2017),(Gilbert, Shaw, et al. 2015) to address the unique needs of women from KAPs in Kazakhstan using a multisectoral, community-coordinated response model. WINGS has been tested and found to identify and reduce IPV among different populations of women who use drugs in the U.S(Gilbert et al. 2016), (Gilbert et al. 2017) and Kyrgyzstan (Gilbert et al. 2017). Emerging research also suggests promising effects of community-mobilization strategies on the reduction of IPV as well as HIV/STI incidence (Abramsky et al. 2014), (Wagman et al. 2015). This community-based implementation trial assessed the safety, acceptability, and effectiveness of implementing UMAI-WINGS in reducing psychological, sexual, and physical IPV over 6 months among 458 participants, comparing the intervention community Almaty City (N=264)) to the control community Almaty Oblast (N=194). We also examined the effectiveness of UMAI-WINGS moderated by type of KAP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

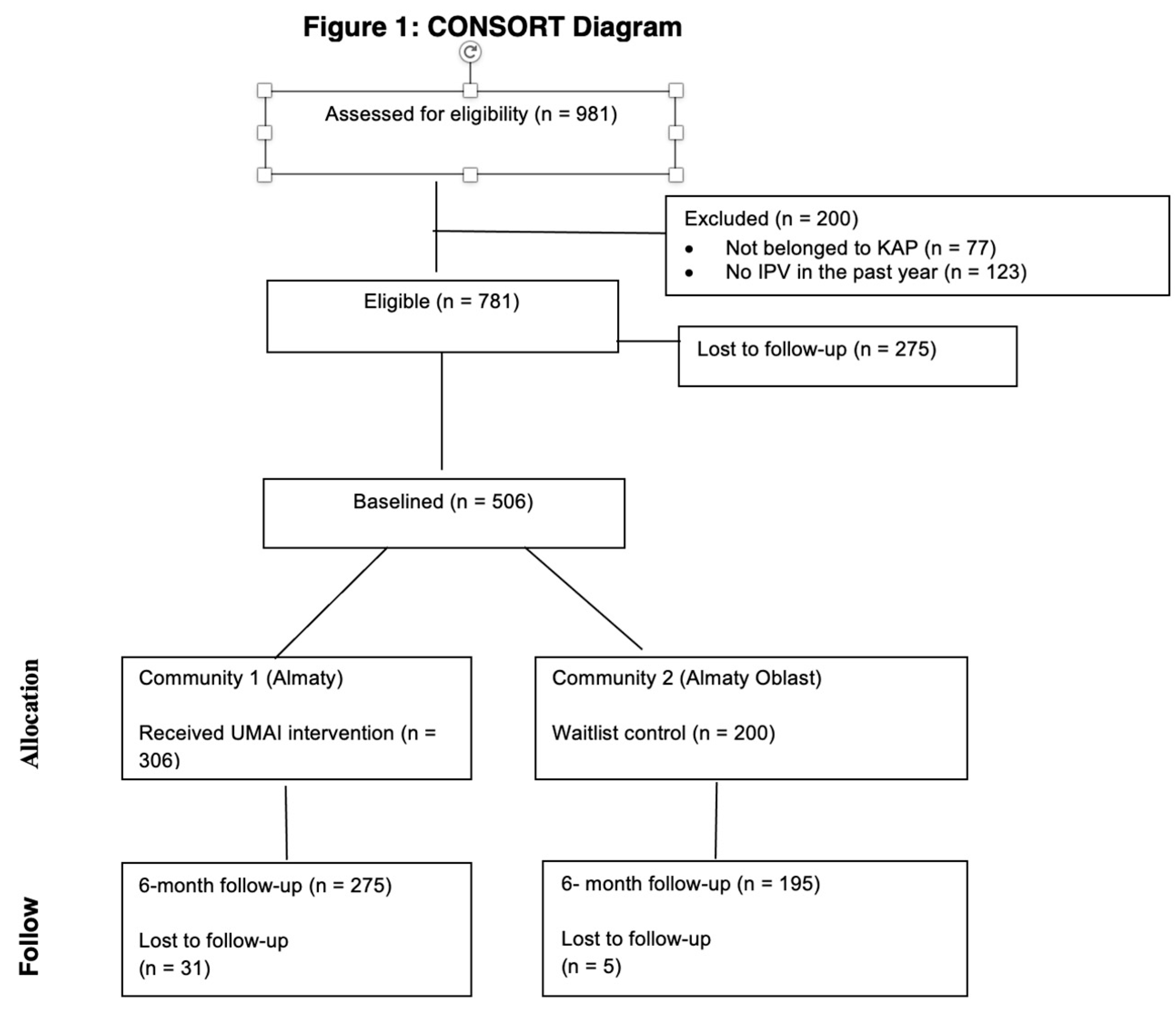

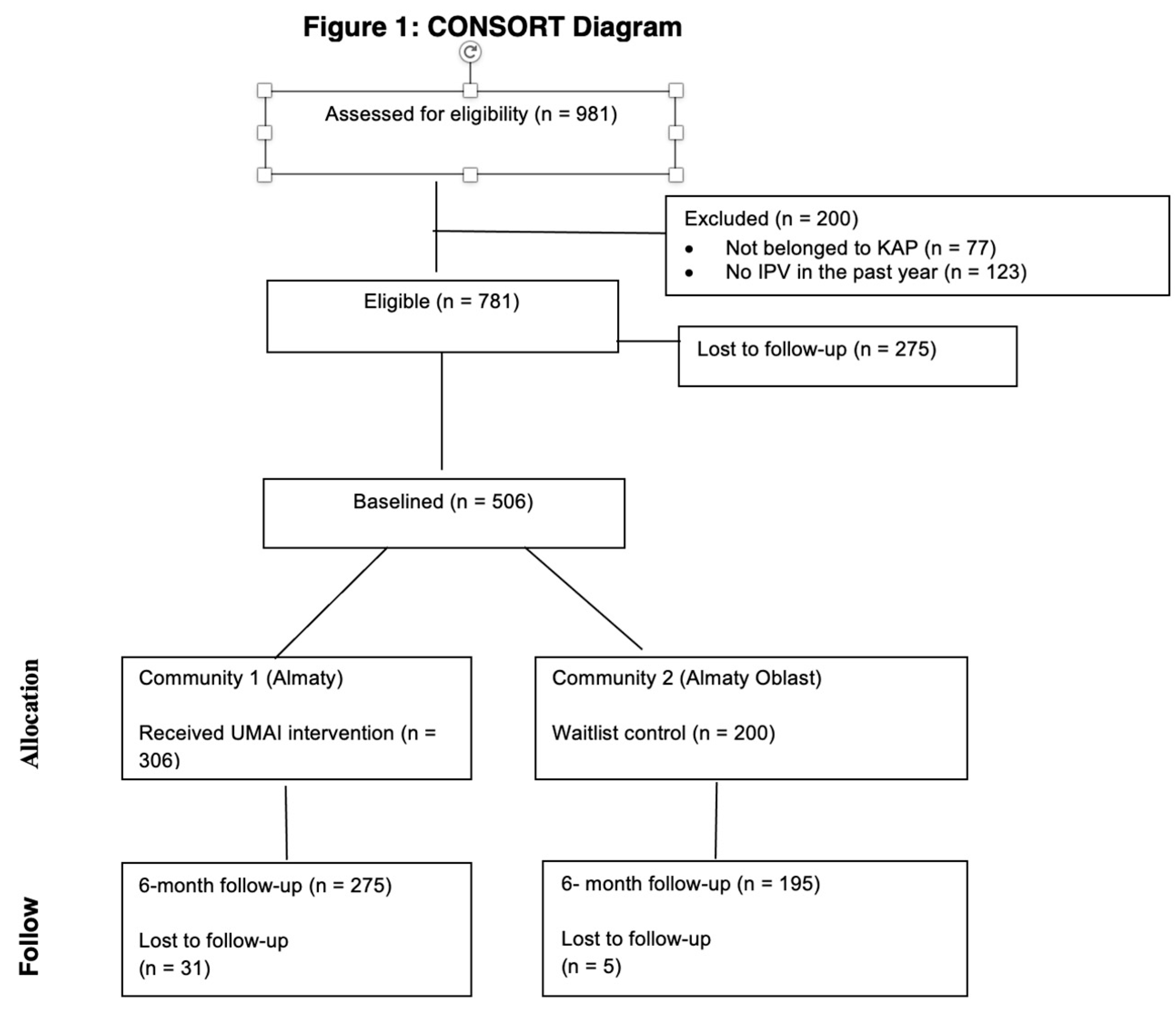

This waitlist control community trial was conducted between April 2022 and December 2024 in Almaty and Almaty region, Kazakhstan. The UMAI-WINGS intervention was conducted in Almaty City (intervention community) and then provided to participants from Almaty oblast or state outside of Almaty City (control community). Study participants completed quantitative assessments at baseline and 6-month follow-up. After the 6-month follow up, the waitlist control community received the intervention. Pre-post outcomes were compared between the intervention community and the waitlist control community. See CONSORT diagram (Figure 1). We opted for a community-level implementation trial rather than an individual-level randomized controlled trial because we wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-level engagement approach to implementing the intervention and building a network of services for women from KAPs with partner organizations. The Al-Farabi Kazakh National University Ethics Committee (IRB00010790) and the Columbia University Institutional Review Board (IRB-AAAU4607) reviewed and approved this study.

2.2. Study Participants

This study included women who: 1) were at least 18 years old; 2) identified as KAP by either (a) having exchanged sex for money, alcohol, drugs, or other goods/resources in the past year; and/or (b) reported living with HIV/AIDS; (c) reported having injected or used drugs and/or binge drinking (4+drinks in one sitting) in the past year; and/or (d) reported identifying as a transgender woman; and 6) reported experiencing IPV in the past year. Women were ineligible if they (1) had cognitive/psychiatric impairment that would prevent comprehension of study procedures as assessed during informed consent; (2) did not speak and understand Russian at a conversational level; or (3) were unwilling or unable to complete informed consent or the study.

Participants were recruited in-person by outreach workers of community-based organizations and health care clinics serving KAPs (i.e., Revansh, Community Friends, Transdocha, Amelia) in two communities: Almaty and Almaty oblast. Potential clients were screened for eligibility and willingness to share their contact information for the study. After confirming eligibility and completing informed consent, participants completed a baseline survey via computer-assisted self-interviews (CASI) at the community-based organizations. After baseline, participants in Almaty (intervention community) immediately proceeded to receive the UMAI–WINGS mhealth self-paced intervention. Participants from intervention and control communities completed a 6-month follow-up via CASI. Waitlist control condition participants (Almaty oblast) were provided the intervention after 6-month follow-up.

2.3. Intervention

The UMAI-WINGS intervention is a combined screening, brief intervention, and referral (SBIRT) that was implemented using a community-coordinated response model. UMAI-WINGS SBIRT is guided by the social cognitive theory and was adapted from the evidence-based intervention WINGS (Gilbert, Shaw, et al. 2015), successfully implemented in lower middle income countries, such as Kyrgyzstan, India, and Ukraine. WINGS has been translated into eight languages and is currently being used in six countries in a wide range of low-resource settings including mainstream GBV services, harm reduction programs, sex work advocacy services, HIV care clinics, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that serve transgender women. UMAI-WINGS SBIRT core components were adapted from the original WINGS 7 Core components: (1) Raising awareness about different types of IPV and risk factors (i.e., substance abuse) for IPV; (2) Screening to identify different types of IPV in women and provide individualized feedback (no, some, high risk); (3) Eliciting motivation to address IPV and relationship conflict, Safety Planning using Motivational Interviewing; (4) Conducting Safety Planning to reduce risks off exposure to IPV; (5) Enhancing Social Support to address relationship conflict and IPV; (6) Setting goals to improve relationship safety and reduce risks of IPV; (7) Identifying and prioritizing Service Needs, Linkage to IPV and other Services. UMAI-WINGS intervention was delivered by staff at partner organizations that serve women from KAPs. This mHealth tool was adjusted to be accessible via mobile devices, allowing women to engage with IPV-related education, safety planning, and support resources at their own convenience and without requiring face-to-face interactions. This digital approach enhances privacy, reduces logistical barriers, and ensures scalability for reaching marginalized women who might otherwise face challenges in accessing traditional IPV services. Nevertheless, some participants preferred to go through the intervention at our partner organizations. To ensure the participant’s safety while using the tool, participants were instructed to do the intervention alone in a private space and to exit the tool using a “safe and save exit button” if they were interrupted. Participants were given options about how to receive their safety plan and service referrals (email, mail, in person).

UMAI-WINGS Community Coordinated Response (CCR) model is based on the evidence-based intervention Community that Care (CTC) that has been successfully employed to reduce violence, drug overdoses, and substance misuse around the world (Sprague Martinez et al. 2020). This model was implemented with a Community Action Board (CAB) comprised of key stakeholders in each community (IPV/GBV service providers, police, service NGO providers working with women from KAPs, IPV/GBV advocates, women with lived experience of IPV/GBV from KAPs). Engagement with the CAB began with guiding CAB members through a process of developing a shared charter, and reviewing data on IPV/GBV among women from KAPS in their communities. Then, the CAB worked together to map services for women from KAPs experiencing IPV/GBV, identifying and addressing service gaps and structural barriers (stigma, discrimination, exclusionary policies, lack of transportation) to access IPV/GBV services among women from KAPs, building a network of IPV-related services and resources. Finally, information about the UMAI-WINGS intervention was delivered through CAB trainings, which also covered topics including how to access data from UMAI-WINGS and other sources to fully comprehend the local crisis, resources, and gaps.

We adapted the original WINGS intervention for the Kazakhstan context and for four KAPs, including women who use drugs (WUD), women engaged in sex work (WSW), women living with HIV (WLH), and transgender women (TGW). For this project, we employed an adaptation process entailing: (1) eliciting feedback on the content and activities of the original WINGS and CTC intervention from representatives of KAPs and CAB members, feedback on ethical considerations and the local context from our CABs in two communities and partner service NGOs (especially with transgender NGO); (2) making refinements to the intervention based on this feedback; (3) Safety planning for WSW and TGW required most formative research and adaptation; (4) identifying barriers and facilitators of implementing the UMAI+CCR interventions with partner organizations and developing an intervention protocol; (5) piloting the adapted UMAI-WINGS intervention with 5 women from targeted groups and revising intervention based on their feedback; and (6) developing the final version of the UMAI-WINGS intervention for implementation.

2.4. Community Engagement and Capacity Building in Intervention Trial

A community engagement approach was embedded throughout the process of working with CABs and focused on co-learning, capacity building, and relationship building. To build the capacity of community service providers and mainstream GBV shelters on GBV identification, screening, safety planning, and linking to services, a series of trainings on the UMAI-WINGS intervention and CCR model were conducted: 1) a standard 8-hour training based on WINGS implementation manual; 2) stigma reduction and sensitivity training on working with key populations was conducted for police, medical and social services providers (2023); 3) training on trauma-based approaches of working with women-survivors of IPV/GBV was conducted for IPV/GBV providers from crisis shelters).

2.5. Measurement

Primary Outcomes: Intimate partner violence was measured with a shortened 8-item version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) (Gilbert et al. 2016),(STRAUS et al. 1996) which assesses any severe/moderate sexual and physical violence by intimate partners (i.e., spouse, boyfriend/girlfriend, regular sexual partners) in the past 6 months. These eight items include all the original CTS2 items that assess severe/moderate sexual and physical IPV with dichotomous yes/no responses. For example, the two items that assess the experience of severe physical IPV by male partners included: (1) Has a male/female partner(s) ever kicked you, slammed you against a wall, beaten you up, punched or kicked you, hit you with something that could hurt or burned or scalded you on purpose? (2) Has a male/female ever choked you or used or threatened to use a knife or gun on you? If participants responded yes to either question, they were coded as positive for experiencing lifetime severe physical violence from male/female partners. Psychological IPV was assessed with two psychological abuse items from the WAST screening tool (J. B. Brown et al. 2000) – (1) have you been humiliated or emotionally abused by your partner or ex-partner? and (2) have you ever been afraid of your partner or ex-partner? If a participant responded yes to either question, they were coded as positive for psychological IPV. For each type of IPV, we compared any exposure to IPV in the past 6 months to none for the regression analyses.

Sociodemographics included age in years, ethnicity (Russian, Kazakh, Other), less than high school education, household income, food insecurity in the past year (yes/no), marital status (married vs. not married) and housing insecurity in the past year (yes/no). In addition, we asked the following dichotomous items to assess the participant’s key affected population status: (1) Did you provide sexual services in exchange for money, alcohol, drugs, or any goods in the past 12 months? (yes/no); (2) Did you use any illicit drugs in the past 12 months? (yes/no); (3) Have you ever been diagnosed with HIV? (yes/no); (4) Do you consider yourself a transgender woman? (yes/no).

Acceptability and Safety: Participants were asked how satisfied they were with the UMAI program (satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, not satisfied), whether or not they used the safety plan, and whether or not they would recommend the UMAI-WINGS program at the 6-month follow-up. To assess the safety of participants, we trained research staff, outreach workers, and program staff at study partner organizations to be able to identify and report a wide range of negative incidents that may occur as a result of participating in the study and the UMAI-WINGS intervention. The investigative team assessed any negative incidents reported by staff to determine whether the incident occurred as a result of study participation in which case it would be deemed an adverse event.

2.6. Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics, key affected population status and IPV outcome measures at the baseline and 6-month follow-up to characterize the total sample and by intervention vs. waitlist control communities. We assessed differences between the intervention and waitlist control communities for these variables with 2-tailed t-tests or χ2 tests for sociodemographic characteristics and key affected population status and unadjusted risk ratios for IPV measures at the baseline and 6-month follow-up. Hypothesis testing to assess the intervention effects of UMAI-WINGS was based on risk ratios (RRs) from log-binomial regression models with the covariate adjustments for the IPV outcome measure at the baseline, engaging in sex work, HIV diagnosis, use of drugs, ethnicity, marital status, past homelessness, and past-year food insecurity. To test whether KAP subgroups (i.e., women who exchange sex for money or drugs, women living with HIV/AIDS, and women who use drugs) moderated the effect of the intervention, separate models were fitted to test the interaction between randomization group (intervention, control) and KAP subgroup. Although the UMAI WINGS intervention was adapted for transgender women, we were only able to enroll 24 in the study, and thus,not able to include them in the moderator analyses, however, we did include them in the bivariate and multivariate analyses. SAS version 9.4 was used to analyze the data.

3. Results

The study CONSORT diagram is presented in Figure 1. The UMAI-WINGS study was conducted between April 2022 and December 2024 in Almaty and Almaty region, Kazakhstan. Of the 981 women recruited for this study, 781 met eligibility criteria. Ineligible women (n=200) were excluded because of not belonging to one of four key population groups (n=77), or not reporting incidents of IPV in the past year (n=123). A total of 506 women agreed to enroll in the study and completed the baseline survey assessment (306 participants from the intervention community and 200 from the waitlist control community). Of the 506 participants, 470 completed the 6-month follow-up assessments (275 participants from the intervention community and 195 from the waitlist control community). The analyses were restricted to data from 458 women who completed the baseline and 6-month follow-up assessments, after excluding 12 participants due to missing data.

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

The descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The mean age was 36.7 (SD=9.0). More than one-third (n=169, 36.9%) identified as Kazakh and 142 (31.0%) identified as Russian. About one-fifth (n=101, 22.1%) had a 9

th grade or lower education, 31.7% (n=145) completed some high school, 35.2% (n=161) completed high school and vocational training, and 11.1% (n=186) had a Bachelor’s degree. One in ten women (n=46, 10.0%) reported being married. Four out of ten women (40.6%, n=186) reported being homeless in the past year and 55.5% (n=254) experienced food insecurity. Almost three quarters (73.1%, n=335) indicated that they exchanged sex for money or drugs in the past 12 months, 58.1% (n=286) reported using drugs and 30.6% (n=140) indicated that were living with HIV, and 5% (n=24) identified as transgender women. Among transgender participants, 92% reported exchanging sex for money, alcohol or drugs; 42% as diagnosed with HIV; 79% of using drugs. Compared to waitlist control community participants, intervention community participants were more likely to identify as Russian and less likely to experience food or housing insecurity. Intervention community participants were also more likely to report living with HIV but less likely to report using drugs or exchanging sex for money or drugs.

3.2. IPV Outcomes

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics on IPV outcomes at each assessment and by intervention assignment. At baseline, 64.6% (n=296) reported experiencing psychological IPV in the past 6 months, 62.9% (N=288) reported sexual IPV and 58.3% (n=267) reported physical IPV.

Table 3 presents the multivariable analyses of intimate partner violence outcomes after adjusting for IPV outcome measures at the baseline, sex worker status, HIV diagnosis, drug use, ethnicity, marital status, past-year homelessness, and past-year food insecurity. Compared to control community participants, intervention community participants were 23.0% less likely to report psychological IPV (aRR=0.77 CI=0.69, 0.86), 27% less likely to report sexual IPV (aRR=0.73, CI=0.63, 0.85), and 29% less likely to report physical IPV (aRR= 0.71, CI=0.63. 0.80) at the 6-month follow-up.

None of these significant intervention effects for different types of IPV were moderated by any KAP subgroup (see

Table 4 for moderator analyses).

3.3. Acceptability

Among the intervention community participants who completed the 6-month follow-up assessments (n=275), 223 (81.1%) were satisfied, 38 (13.8%) were neutral and 14 (5.1%) were dissatisfied. The large majority 259 (94.2%) reported that they would recommend the UMAI-WINGS program to other women in their community. Over one-half of the participants reported using the safety plan and 96% said the safety planning activity was useful.

3.4. Safety

There were no negative incidents reported by the research staff and program staff who interacted with participants that were considered to be adverse events.

4. Discussion

The study findings indicate that women in the UMAI-WINGS IPV SBIRT intervention community were significantly more likely to reduce their experiences of all types of IPV compared to women in the control community in Kazakhstan, consistent with prior studies documenting the efficacy of this IPV SBIRT intervention with women from KAPs(Gilbert et al. 2016),(Gilbert et al. 2017). The lack of moderator effects by subgroups (i.e., WUD, WSW, WLH,) further suggests that the intervention was effective for all KAPs. To date, this is the largest community-based trial of an IPV SBIRT intervention with key affected populations of women. Moreover, this study found that the UMAI-WINGS intervention was acceptable to study participants as indicated by a high satisfaction rating and safe as indicated by the absence of adverse events.

This trial employed innovative multi-level implementation strategies to address community-level and organizational barriers that prevent women from KAPs from accessing IPV services and from gaining the safety planning skills and resources to reduce their risk of exposure to IPV. Multiple factors may have contributed to the positive outcomes of this study. The engagement of the CAB with diverse stakeholders (e.g., police, IPV service providers, health care providers, KAP NGOs, and women from KAPs with lived experience of IPV) during all phases of adapting and implementing UMAI-WINGS may have reduced barriers to expanding access to key IPV-related services including police protection, legal orders of protection, emergency shelters, counseling, and mental services. The CAB identified and mobilized a network of IPV, drug and alcohol treatment, harm reduction, mental health, and other services equipped to serve women from KAPs experiencing IPV. The CAB also worked closely with the study team to identify community-level and organizational-level barriers and facilitators to implementing UMAI- WINGS in partner organizations and make adaptations to improve the implementation infrastructure for delivering UMAI-WINGS in various settings. Implementation strategies also included training, technical assistance, supervision, and collaborative learning sessions with UMAI WINGS partner organizations and staff to ensure greater fidelity and uptake of the intervention. UMAI-WINGS embraced core harm reduction principles of empowering women from KAPs to make their own decisions about their relationships and how best to reduce risks and harms from IPV. Further research is needed to identify what multi-level implementation strategies and components of the UMAI-WINGS SBIRT intervention may have contributed to the significant reduction of IPV among women from different KAPs in the intervention community.

The extremely high rates of experiencing all types of IPV in the past 6 months found in this study underscore the major public health and humanitarian crisis that IPV presents for women from KAPs in Kazakhstan. Moreover, the strong associations linking IPV to HIV/STIs, drug overdoses, substance use disorders, PTSD, and other mental health and physical health issues among women from KAPs (El-Bassel et al. 2022),(Gilbert et al. 2022),(Gilbert, Raj, et al. 2015) further highlight the critical need to redouble efforts to redress this crisis. The high rate of police abuse experienced by participants in this study, along with the high levels of stigma and discrimination and lack of access to mainstream IPV services, continue to present substantial barriers to ensuring that women from KAPs have the resources and services they need to reduce their risks of experiencing IPV.

4.1. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations that are important to note. First, there may be inextricable differences in the socio-demographics and community-level factors between the intervention and control community that may have contributed to the positive outcomes of this study. Almaty City is a primarily urban community, with most participants identifying as Russian ethnicity. Almaty Oblast is primarily a rural community, with most participants identifying as Kazakh ethnicity. Given our community-driven multi-level approach to implementing WINGS, a randomized controlled trial with the individual as the unit of analysis was not an appropriate intervention design. Second, this study relied solely on self-reported IPV measures that are subject to bias. Third, the results of this study have limited generalizability to women from KAPs in Almaty City and Almaty Oblast.

4.2. Strength and Implications of the Study

These limitations are offset by several strengths, including a robust community engagement approach, a relatively large sample size, controlling for key covariates in the outcome analyses, using widely used standardized measures of IPV, and including women from different KAPs. Taken together, the study findings suggest that a community-driven multi-level approach to adapting and implementing this mHealth IPV SBIRT intervention holds promise for reducing the serious public health threat of IPV among women from different KAPs in Kazakhstan.

5. Conclusions

The study findings suggest that a community-based approach to delivering the mHealth UMAI-WINGS intervention was feasible, acceptable, safe, and effective in reducing IPV among women from different KAPs, consistent with other findings on WINGS (Gilbert et al. 2016),(Gilbert et al. 2017),(Gilbert, Shaw, et al. 2015). UMAI-WINGS is designed as a low-threshold mHealth self-administered tool and service that can be successfully implemented and scaled up in a wide range of clinical and NGO settings using a community-based approach. Future research with a larger scale randomized community design and a larger sample of communities is needed to evaluate the outcomes of this community-driven multi-level approach more rigorously. Such research may also identify key mediators and moderators of this IPV SBIRT intervention that may further optimize the delivery of UMAI-WINGS for different settings and communities. The extremely high rates of recent IPV found among women from KAPs in this study underscore a call for action for harm reduction policies and programs to widen access to effective services and resources to redress this widespread epidemic and humanitarian crisis in Kazakhstan.

Author Contributions

AT: LG, SP conceptualized the study; AT, SP, AD, LG developed methodology; AT, SP, AR, MN, ZB, YB implemented the study; OC, MC conducted data analysis; AT, SP, LG prepared the original draft; all authors reviewed and edited the draft manuscript; AT, SP, LG acquired funding; AT, SP administered the grant funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This study was funded by the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI), contact PI: Assel Terlikbayeva. O.S. Gatanaga was supported by grant number T32DA057920 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. A. Terlikbayeva was supported by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010046. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical committee of Al-Farabi Kazakh National University-wide letter no. A491 (IRB00010790) dated 10-13-2022 and Columbia University, protocol no. IRB-AAAU4607 dated 09-25-2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was signed by all the partners. Consent for publications was also taken.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided following a reasonable request to the first author.

Acknowledgments

We thank and recognize the contributions of the women who offered their time and energy to support this research. We thank our community partners in Almaty City and Almaty Oblast who helped with intervention adaptation and implementation (Zholnerova Nataliya, NGO “Ameliya”; Sunkar Kadyrov, Center for Social Support of Victims of Domestic Violence, Taldykorgan; Raushan Alpysbayeva, Center for Social Support of Victims of Domestic Violence, Almaty Oblast). We acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the CSPI team members (Pavel Gulyaev, Valera Gulyaev, Raushan Kattabekova) who supported the study’s implementation and all the community members who promoted and supported the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramsky, Tanya, Karen Devries, Ligia Kiss, Janet Nakuti, Nambusi Kyegombe, Elizabeth Starmann, Bonnie Cundill, et al. 2014. “Findings from the SASA! Study: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Impact of a Community Mobilization Intervention to Prevent Violence against Women and Reduce HIV Risk in Kampala, Uganda.” BMC Medicine 12 (1): 122. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J B, B Lent, G Schmidt, and G Sas. 2000. “Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-Short in the Family Practice Setting.” The Journal of Family Practice 49 (10): 896–903.

- Brown, Laura J, Hattie Lowe, Andrew Gibbs, Colette Smith, and Jenevieve Mannell. 2023. “High-Risk Contexts for Violence Against Women: Using Latent Class Analysis to Understand Structural and Contextual Drivers of Intimate Partner Violence at the National Level.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38 (1–2): 1007–39. [CrossRef]

- El-Bassel, Nabila, Trena I. Mukherjee, Claudia Stoicescu, Laura E. Starbird, Jamila K. Stockman, Victoria Frye, and Louisa Gilbert. 2022. “Intertwined Epidemics: Progress, Gaps, and Opportunities to Address Intimate Partner Violence and HIV among Key Populations of Women.” The Lancet HIV 9 (3): e202–13. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Louisa, Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Timothy Hunt, Xin Ma, Mingway Chang, Jessica Rowe, Tara McCrimmon, et al. 2016. “Efficacy of a Computerized Intervention on HIV and Intimate Partner Violence Among Substance-Using Women in Community Corrections: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (7): 1278–86. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Louisa, Tina Jiwatram-Negron, Danil Nikitin, Olga Rychkova, Tara McCrimmon, Irena Ermolaeva, Nadejda Sharonova, Aibek Mukambetov, and Timothy Hunt. 2017. “Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of a Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment Model to Address Gender-Based Violence among Women Who Use Drugs in Kyrgyzstan: Project WINGS (Women Initiating New Goals of Safety).” Drug and Alcohol Review 36 (1): 125–33. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Louisa, Phillip L. Marotta, Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Ariel Richer, Jasmine Akuffo, Timothy Hunt, Elwin Wu, and Nabila El-Bassel. 2022. “Association Between Multiple Experiences of Violence and Drug Overdose Among Black Women in Community Supervision Programs in New York City.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37 (23–24): NP21502–24. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Louisa, Anita Raj, Denise Hien, Jamila Stockman, Assel Terlikbayeva, and Gail Wyatt. 2015. “Targeting the SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS) Syndemic Among Women and Girls: A Global Review of Epidemiology and Integrated Interventions.” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69 (June):S118. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Louisa, Stacey A. Shaw, Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Mingway Chang, Jessica Rowe, Tara.

- McCrimmon, Maria Almonte, Sharun Goodwin, and Matthew Epperson. 2015. “Project WINGS (Women Initiating New Goals of Safety): A Randomised Controlled Trial of a Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Service to Identify and Address Intimate Partner Violence Victimisation among Substance-Using Women Receiving Community Supervision.” Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 25 (4): 314–29. [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, Lakma, Jahar Bhowmik, Pragalathan Apputhurai, and Maja Nedeljkovic. 2023. “Factors and Consequences Associated with Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” PLOS ONE 18 (11): e0293295. [CrossRef]

- “HIV Status: Challenges That Women Face | United Nations Development Programme.” n.d. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/stories/hiv-status-challenges-women-face.

- Jiwatram-Negrón, Tina, Nabila El-Bassel, Sholpan Primbetova, and Assel Terlikbayeva. 2018. “Gender-Based Violence Among HIV-Positive Women in Kazakhstan: Prevalence, Types, and Associated Risk and Protective Factors.” Violence Against Women 24 (13): 1570–90. [CrossRef]

- “Kazakhstan: New Law to Protect Women Improved, but Incomplete | Human Rights Watch.” 2024. April 23, 2024. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/23/kazakhstan-new-law-protect-women-improved-incomplete.

- “Kazakhstan’s New Domestic Violence Law Is Welcome but Further Reforms Need to Close Remaining Protection Gaps - Kazakhstan | ReliefWeb.” 2024. May 16, 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/kazakhstan/kazakhstans-new-domestic-violence-law-welcome-further-reforms-need-close-remaining-protection-gap.

- “Kazakhstan’s Year in Review: Prevention of Domestic Abuse, Protection of Women’s & Children’s Rights - The Astana Times.” n.d. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://astanatimes.com/2024/12/kazakhstans-year-in-review-prevention-of-domestic-abuse-protection-of-womens-childrens-rights/.

- Kemelova, Fatima. 2023. “UN Reports on Anti-Gender Violence Campaign in Kazakhstan.” The Astana Times. December 14, 2023. https://astanatimes.com/2023/12/un-reports-on-anti-gender-violence-campaign-in-kazakhstan/.

- “Kazakh Senate Approves Law to Criminalize Domestic Violence.” The Astana Times. April 11, 2024. https://astanatimes.com/2024/04/kazakh-senate-approves-law-to-criminalize-domestic-violence/.

- Kurdyla, Victoria, Adam M. Messinger, and Milka Ramirez. 2021. “Transgender Intimate Partner Violence and Help-Seeking Patterns.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36 (19–20): NP11046–69. [CrossRef]

- Mannell, Jenevieve, Hattie Lowe, Laura Brown, Reshmi Mukerji, Delan Devakumar, Lu Gram, Henrica A. F. M. Jansen, et al. 2022. “Risk Factors for Violence against Women in High-Prevalence Settings: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis.” BMJ Global Health 7 (3). [CrossRef]

- Mojahed, Amera, Judith T. Mack, Andreas Staudt, Victoria Weise, Lakshmi Shiva, Prabha Chandra, and Susan Garthus-Niegel. 2024. “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Intimate Partner Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the Population-Based Study DREAMCORONA.” PLOS ONE 19 (6): e0306103. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Trena I, Assel Terlikbayeva, Tara McCrimmon, Sholpan Primbetova, Guakhar Mergenova, Shoshana Benjamin, Susan Witte, and Nabila El-Bassel. 2023. “Association of Gender-Based Violence with Sexual and Drug-Related HIV Risk among Female Sex Workers Who Use Drugs in Kazakhstan.” International Journal of STD & AIDS 34 (10): 666–76. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Maureen, Mary Ellsberg, Aminat Balogun, and Claudia Garcia-Moreno. 2021. “Risk and Protective Factors for GBV among Women and Girls Living in Humanitarian Setting: Systematic Review Protocol.” Systematic Reviews 10 (1): 238. [CrossRef]

- Mussabekova, Saule A., Xeniya E. Mkhitaryan, and Khamida R. Abdikadirova. 2024. “Domestic Violence in Kazakhstan: Forensic-Medical and Medical-Social Aspects.” Forensic Science International: Reports 9 (July):100356. [CrossRef]

- Muyanga, Naume, John Bosco Isunju, Tonny Ssekamatte, Aisha Nalugya, Patience Oputan, Juliet Kiguli, Simon Peter S. Kibira, et al. 2023. “Understanding the Effect of Gender-Based Violence on Uptake and Utilisation of HIV Prevention, Treatment, and Care Services among Transgender Women: A Qualitative Study in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area, Uganda.” BMC Women’s Health 23 (1): 250. [CrossRef]

- Organization, World Health. 2021. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women. World Health Organization.

- Peitzmeier, Sarah M., Mannat Malik, Shanna K. Kattari, Elliot Marrow, Rob Stephenson, Madina Agénor, and Sari L. Reisner. 2020. “Intimate Partner Violence in Transgender Populations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Correlates.” American Journal of Public Health 110 (9): e1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sabri, Bushra, and Anna Marie Young. 2022. “Contextual Factors Associated with Gender-Based Violence and Related Homicides Perpetrated by Partners and in-Laws: A Study of Women Survivors in India.” Health Care for Women International 43 (7–8): 784–805. [CrossRef]

- Sprague Martinez, Linda, Bruce D. Rapkin, April Young, Bridget Freisthler, LaShawn Glasgow, Tim Hunt, Pamela J. Salsberry, et al. 2020. “Community Engagement to Implement Evidence-Based Practices in the HEALing Communities Study.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 217 (December):108326. [CrossRef]

- STRAUS, MURRAY A., SHERRY L. HAMBY, SUE BONEY-McCOY, and DAVID B. SUGARMAN. 1996. “The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data.” Journal of Family Issues 17 (3): 283–316. [CrossRef]

- Wagman, Jennifer A., Ronald H. Gray, Jacquelyn C. Campbell, Marie Thoma, Anthony Ndyanabo, Joseph Ssekasanvu, Fred Nalugoda, et al. 2015. “Effectiveness of an Integrated Intimate Partner Violence and HIV Prevention Intervention in Rakai, Uganda: Analysis of an Intervention in an Existing Cluster Randomised Cohort.” The Lancet Global Health 3 (1): e23–33. [CrossRef]

- “What’s Wrong with Women’s Crisis Centres in Kazakhstan? - CABAR.Asia.” n.d. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://cabar.asia/en/what-s-wrong-with-women-s-crisis-centres-in-kazakhstan.

- Witte, Susan S., Lyla Sunyoung Yang, Tara McCrimmon, Toivgoo Aira, Altantsetseg Batsukh, Assel Terlikbayeva, Sholpan Primbetova, et al. 2023. “Combination Microfinance and HIV Risk Reduction Among Women Engaged in Sex Work.” Research on Social Work Practice 33 (2): 213–29. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Key Affected Population status of the Sample (n = 458).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Key Affected Population status of the Sample (n = 458).

| . |

Univariable |

Bivariable Comparisons |

| |

Full Sample

(n =458) |

Almaty Oblast - Control

(n=194) |

Almaty City - Intervention

(n=264) |

P-Value |

| Age |

36.7 (9.0) |

36.1 (9.0) |

37.0 (9.0) |

0.285 |

| Nationality |

|

|

|

|

| Kazakh |

169 (36.9%) |

89 (45.9%) |

80 (30.3%) |

< 0.001 |

| Russian |

142 (31.0%) |

38 (19.6%) |

104 (39.4%) |

| Other |

147 (32.1%) |

67 (34.5%) |

80 (30.3%) |

| Education |

|

|

|

|

| 9th grade or lower |

101 (22.1%) |

37 (19.1%) |

64 (24.2%) |

0.258 |

| Secondary Education |

145 (31.7%) |

57 (29.4%) |

88 (33.3%) |

| High School |

161 (35.2%) |

77 (39.7%) |

84 (31.8%) |

| Bachelor’s or more |

51 (11.1%) |

23 (11.9%) |

28 (10.6%) |

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

| Married |

46 (10.0%) |

12 (6.2%) |

34 (12.9%) |

0.019 |

| Not married/other |

412 (89.96%) |

182 (93.8%) |

230 (87.1%) |

|

| Homelessness (past-year) |

186 (40.6%) |

104 (53.6%) |

82 (31.1%) |

< 0.001 |

| Food Insecurity(past-year) |

254 (55.5%) |

133 (68.6%) |

121 (45.8%) |

< 0.001 |

| Income (USD) |

412.22(472.34) |

412.53 (399.91) |

411.99 (519.92) |

0.990 |

| Key Affected Population |

|

|

|

|

| Sex Workers |

335 (73.1%) |

163 (84.0%) |

172 (65.2%) |

< 0.001 |

| Persons who use drugs |

266 (58.1%) |

146 (75.3%) |

120 (45.5%) |

< 0.001 |

| Persons living with HIV |

140 (30.6%) |

34 (17.5%) |

106 (40.2%) |

< 0.001 |

Table 2.

Descriptives and Unadjusted Risk Ratios of Baseline and Past 6-Month Intimate Partner Violence by Intervention Group (n = 458).

Table 2.

Descriptives and Unadjusted Risk Ratios of Baseline and Past 6-Month Intimate Partner Violence by Intervention Group (n = 458).

| |

Univariable |

Bivariable Comparisons |

| |

Full Sample

(n =458) |

Almaty Oblast - Control

(n=194) |

Almaty City - Intervention

(n=264) |

Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

| Psychological |

|

|

|

|

| Baseline |

296 (64.6%) |

127 (65.5%) |

169 (64.0%) |

0.97 (0.83, 1.15) |

| Six-month Follow-up |

256 (55.9%) |

146 (75.3%) |

110 (41.7%) |

0.56 (0.48, 0.66) |

| Sexual |

|

|

|

|

| Baseline |

288 (62.9%) |

123 (63.4%) |

165 (62.5%) |

0.98 (0.84, 1.16) |

| Six-month Follow-up |

252 (55.0%) |

137 (70.6%) |

115 (43.6%) |

0.63 (0.54, 0.74) |

| Physical |

|

|

|

|

| Baseline |

267 (58.3%) |

130 (67.0%) |

137 (51.9%) |

0.77 (0.66, 0.90) |

| Six-month Follow-up |

211 (46.1%) |

143 (73.7%) |

68 (25.8%) |

0.30 (0.23, 0.40) |

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses of Intimate Partner Violence Outcomes.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses of Intimate Partner Violence Outcomes.

| |

Multivariable Model |

| |

aRR (95% CI) |

P-Value |

| Past 6-Month Intimate Partner Violence |

|

|

| Psychological |

0.77 (0.69, 0.86) |

<.0001 |

| Sexual |

0.73 (0.63, 0.85) |

<.0001 |

| Physical |

0.71 (0.63, 0.80) |

<.0001 |

Table 4.

Moderator Analyses of Intimate Partner Violence by Key Population, Post-Intervention.

Table 4.

Moderator Analyses of Intimate Partner Violence by Key Population, Post-Intervention.

| |

Multivariable Model |

| |

aRR (95% CI) |

P-Value |

| Past 6-Month Psychological IPV |

|

|

| Persons living with HIV |

1.05 (0.79, 1.40) |

0.748 |

| Persons who use drugs |

1.23 (0.92, 1.63) |

0.160 |

| Sex Workers |

1.03 (0.78, 1.37) |

0.833 |

| Past 6-Month Sexual IPV |

|

|

| Persons living with HIV |

0.91 (0.71, 1.18) |

0.478 |

| Persons who use drugs |

1.07 (0.78, 1.48) |

0.678 |

| Sex Workers |

1.06 (0.79, 1.41) |

0.697 |

| Past 6-Month Physical IPV |

|

|

| Persons living with HIV |

1.03 (0.81, 1.32) |

0.796 |

| Persons who use drugs |

0.95 (0.74, 1.22) |

0.690 |

| Sex Workers |

0.97 (0.74, 1.28) |

0.838 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).