1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that infects epithelial cells and is recognized as a major etiological factor in several human malignancies, most notably cervical cancer, which remains the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide [

1]. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2022 estimates, cervical cancer accounted for over 600,000 new cases and 340,000 deaths globally, with the highest burden in low- and middle-income countries [

2]. Beyond the cervix, high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, are also implicated in the development of anogenital cancers (including vulvar, vaginal, penile, and anal cancers) and a growing proportion of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC), particularly in high-income countries [

3,

4].

The oncogenic potential of high-risk HPV is largely driven by the persistent expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, which disrupt host tumor suppressor pathways. E6 promotes degradation of the tumor suppressor p53 via the E6AP ubiquitin ligase, while E7 inactivates the retinoblastoma protein (pRb), leading to uncontrolled cell cycle progression and inhibition of apoptosis [

5,

6]. These viral-mediated mechanisms contribute to genomic instability, deregulation of the DNA damage response, and accumulation of somatic mutations that drive carcinogenesis [

7]. While the nuclear genomic consequences of HPV infection have been extensively studied, emerging evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction and alterations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) may also play a critical role in HPV-associated tumorigenesis [

8,

9].

Mitochondria are essential organelles involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), ATP production, regulation of apoptosis, calcium signaling, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [

10]. Unlike nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA is a circular, double-stranded molecule that encodes 13 essential protein subunits of the electron transport chain, along with 22 tRNAs and 2 rRNAs [

11]. mtDNA is particularly vulnerable to damage due to its proximity to the inner mitochondrial membrane where ROS are generated, the absence of protective histones, and limited DNA repair mechanisms [

12]. Alterations in mtDNA such as point mutations, large deletions, copy number changes, and transcriptional dysregulation—have been increasingly associated with various cancers, including breast, colorectal, and head and neck cancers [

13,

14].

Recent studies have begun to reveal a link between HPV infection and mitochondrial dysfunction. HPV oncoproteins have been shown to interact with mitochondrial pathways, leading to increased ROS production, metabolic reprogramming, and resistance to apoptosis [

15,

16,

17] . Notably, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of HPV-positive cancers have identified significant changes in mitochondrial gene expression profiles, suggesting a potential role for mtDNA alterations in HPV-mediated oncogenesis [

8,

18,

19]. These findings align with the broader concept that mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to cancer progression through the Warburg effect, redox imbalance, and evasion of cell death [

20].

Given the central role of mitochondria in cellular homeostasis and stress responses, understanding mtDNA alterations in HPV-related cancers offers a promising yet underexplored avenue for biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting. mtDNA mutations and copy number variations may serve as indicators of mitochondrial stress and tumor aggressiveness, while altered expression of mitochondria-encoded genes could inform patient stratification or predict treatment responses [

21]. Furthermore, with the advent of high-throughput sequencing and advanced model systems such as 3D organoids and patient-derived spheroids, it is now feasible to investigate mtDNA changes in a biologically relevant context [

22].

This review aims to summarize current knowledge on mitochondrial DNA alterations in HPV-related cancers, with a focus on their biological consequences, clinical implications, and future potential as therapeutic targets. By integrating recent findings from transcriptomics, mitochondrial biology, and HPV research, we seek to provide a comprehensive perspective on this emerging field and highlight opportunities for translational research.

2. HPV and Mitochondrial Function

Human papillomavirus (HPV) oncoproteins, particularly E6 and E7, exert multifaceted effects on mitochondrial function that contribute to carcinogenesis [

18]. Beyond their role in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and ATP production, mitochondria are central regulators of apoptosis, redox homeostasis, and metabolic adaptation. By targeting these organelles, HPV reshapes cellular metabolism, survival capacity, and stress responses to support persistent infection and malignant transformation. HPV oncoproteins’ interaction with mitochondrial function are given in

Table 1.

2.1. Modulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics

Mitochondrial dynamics, namely the coordinated balance between fission and fusion, is essential for maintaining mitochondrial morphology, distribution, and function. These processes are regulated by GTPases such as dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) and fission protein 1 (FIS1) for fission, and mitofusins (MFN1, MFN2) and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1) for fusion [

23,

24]. Evidence from HPV-positive models indicates that infection can alter mitochondrial function and homeostasis, including changes in bioenergetic efficiency and apoptotic susceptibility, potentially affecting the balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion [

18]. While the detailed molecular connection between E6 and the fission–fusion machinery remains unresolved, E6’s capacity to destabilize mitochondrial integrity indirectly through p53 degradation and suppression of mitochondrial biogenesis regulators like PGC-1α suggests a plausible mechanism of influence [

9,

25]. In this context, studies in cervical cancer cells have shown that pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial dynamics, like silibinin treatment, can induce excessive mitochondrial fragmentation, upregulate DRP1 expression without altering FIS1, and promote mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced ATP production, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and increased ROS generation [

26]. These mitochondrial changes were accompanied by G2/M cell cycle arrest, and DRP1 knockdown was able to reverse both the mitochondrial fragmentation and cell cycle effects, underscoring the central role of DRP1-mediated fission in regulating cervical cancer cell proliferation and survival.E7 exerts its effects more clearly through degradation of pRb and activation of E2F-responsive genes, which can alter the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins and regulators of organelle morphology [

27]. Notably, E2F1 has been shown to bind to the promoter of MFN2 and activate its transcription, with transcription factor SP1 also binding to the same promoter region. E2F1 and SP1 can form a complex at the MFN2 promoter, and E2F1-mediated regulation of MFN2 appears to influence both mitochondrial fusion and mitophagy, potentially linking E7-driven transcriptional reprogramming to the control of mitochondrial quality and turnover [

28]. In some settings, E7 has also been associated with increased mitophagy, leading to selective removal of mitochondria and reshaping of the cellular mitochondrial pool [

29]. Together, these alterations create a fragmented and metabolically reprogrammed mitochondrial network that supports the energetic and biosynthetic demands of HPV-transformed cells.

2.2. Impact on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation and Oxidative Stress

Disruption of mitochondrial dynamics in HPV-positive cells is closely linked to altered redox homeostasis, with fragmented mitochondria and compromised electron transport chain (ETC) integrity, particularly at complexes I and III, increasing electron leakage and driving excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

30]. While physiological ROS levels act as secondary messengers that activate pro-survival and pro-proliferative pathways, including NF-κB and HIF-1α signaling, chronic overproduction of ROS imposes sustained oxidative stress that damages nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), lipids, and proteins, thereby fostering genomic instability [

31]. The E6 oncoprotein exacerbates this oxidative environment by impairing p53-mediated transcription of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and catalase, weakening the cell’s ability to neutralize ROS [

32]. E7 contributes indirectly, as its dysregulation of cell cycle progression and metabolic flux increases mitochondrial workload, further promoting electron leakage [

33]. Persistent oxidative stress not only accelerates mutagenesis but also reinforces malignant progression by activating redox-sensitive transcription factors and survival pathways, creating a tumor-favorable oxidative environment that supports both HPV persistence and oncogenic transformation [

34].

2.3. Links Between HPV Infection, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

HPV-induced mitochondrial alterations are closely intertwined with metabolic reprogramming, a hallmark of HPV-associated cancers. Both E6 and E7 promote a shift away from oxidative phosphorylation toward aerobic glycolysis, enabling rapid ATP production while redirecting metabolic intermediates toward biosynthetic pathways that support proliferation [

35,

36]. This metabolic shift is reinforced by oxidative stress–mediated stabilization of HIF-1α, which upregulates key glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), along with glucose transporters like GLUT1, thereby increasing glucose uptake and glycolytic flux [

37,

38,

39]. Reduced mitochondrial respiratory efficiency, which is stemming from structural damage to cristae, disruption of the electron transport chain, and altered expression of mitochondrial proteins, diminishes ATP yield from oxidative pathways and increases the cell’s dependency on glycolysis [

40]. (Hongxiang Du et al. 2025) The resulting excess lactate production acidifies the tumor microenvironment, a change that facilitates immune evasion, promotes extracellular matrix remodeling, and supports angiogenesis [

41,

42]. Furthermore, E6/E7-mediated modulation of mitochondrial biogenesis regulators such as PGC-1α and TFAM can alter mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number and transcription, exacerbating the loss of oxidative capacity and contributing to long-term mitochondrial dysfunction. Together, these changes integrate mitochondrial impairment into the broader oncogenic program of HPV, coupling metabolic flexibility with tumor-promoting adaptations in the microenvironment [

25,

43].

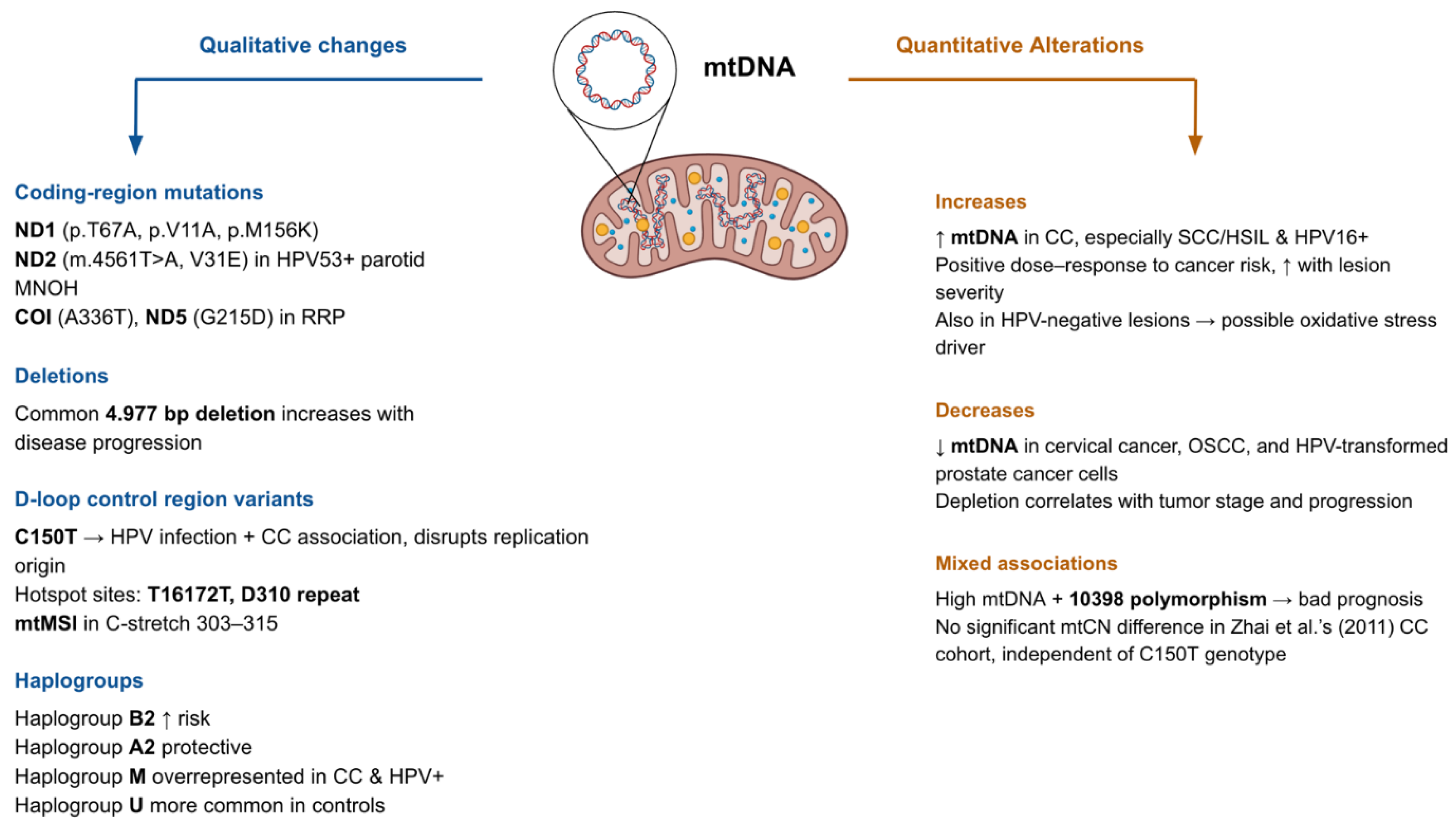

3. Qualitative and Quantitative Alterations in the Mitochondrial Genome

Susceptibility to HPV infection and progression of malignancies associated with HPV seem to rely on the mitochondrial genetic background, both qualitative and quantitative. In their study, Feng et al. (2016) stratified cervical cancer patients by both mtDNA content and the mtDNA 10398 polymorphism. The presence of the 10398 polymorphism and elevated mtDNA content exhibited the worst prognosis, relating to 5 to 8 years lower overall survival (OS). While the 10398A allele itself was not associated with OS, it was linked to increased mtDNA content, and the 10398G allele was found more frequently in HPV-positive patients. Notably, a positive correlation between HPV-18 infection and mtDNA content was found in patients aged < 45 years [

44].

Guardado-Estrada et al. (2012) investigated the role of mtDNA haplogroups in CC. In the Amerindian mtDNA haplogroups, B2 conferred increased risk especially for HPV-related CC cases and A2 exerted a protective effect. This was accompanied by haplogroup-specific overexpression of mitochondrial tRNA genes and regulatory polymorphisms like 6183C and 16189C that may influence replication and transcription [

45]. Likewise, Zhai et al. (2011) found that the C150T polymorphism was significantly associated with HPV infection and CC among the 90 identified polymorphic sites in the D-loop control region. The authors believe this change disrupts the origin of replication in the heavy strand of mtDNA and modifies the mitochondrial replication and OXPHOS, leading to increased malignant transformative capacity. Interestingly, for the mtDNA copy number, there was no significant relationship between CC patients. It was also found to be independent of the C150T genotype [

46].

Sharma et al. (2005) also reported 55 novel mutations within the D-loop in cervical tumors, primarily base substitutions and indels, with significant correlation with HPV infection (p < 0.05). mtDNA microsatellite instability (mtMSI) was also detected in 12 out of 19 tumors, located mostly in the C-stretch in positions 303–315 (11/19), a known replication primer binding site [

47]. Warowicka et al. (2013) identified a total of 62 nucleotide changes across L-SIL (n=28), H-SIL (n=30), CC (n=29), and control (n=29) tissues, where 13 mutations were uniquely present in all disease stages but absent in controls, suggesting a role in early to progressive carcinogenesis. The accumulation of a common 4.977 bp deletion was also described related with disease progression, suggesting that HPV infection may either promote mtDNA damage or choose to persist in cells with compromised mitochondrial genomes [

19].

Changes in mtDNA copy number are a recurring but context-dependent feature. In cervical cancer, Sun et al. (2020) and Al-Awadhi et al. (2023) reported significantly elevated mtDNA copy numbers (mtCN), particularly in high-grade lesions (highest in SCC/HSIL cases) and HPV16-positive cases, with a dose-response relationship to cancer risk and suggesting a correlation of mtCN with lesion severity. This increase was also seen in HPV-negative lesions, suggesting oxidative stress may be an additional driver [

48,

49]. In contrast, Kabekkodu et al. (2014) and Mondal et al. (2013) observed mtDNA depletion in cervical and oral squamous cell carcinomas, respectively, where depletion correlated with tumor stage [

50,

51]. Mizumachi et al. (2008) similarly found reduced and more variable mtDNA content in HPV-transformed prostate cancer cells compared to HPV-transformed normal epithelial cells [

52]. Mondal et al (2013) showed that a significant difference between the mtDNA content was present between HPV-positive & negative individuals, but the depletion of mtDNA in OSCC was associated with tumor progression and risk regardless of HPV status, similar to the mentioned findings in prostate cancer [

51].

Kabekkodu et al. (2014) also revealed that 65% of mtDNA from CC samples belonged to haplogroup M, compared to 16% in non-malignant tissues. In contrast, haplogroup U was more common in controls (50% vs. 10%). The D-loop region exhibited 216 variants, including 29 novel and 4 disease-associated mutations. Alterations were predominantly base substitutions and indels, with T16172T and D310 repeat as hotspot sites. Overall mutational burden was not directly associated with HPV status, but specific variants such as A73G were significantly more common in HPV-positive samples and haplogroup M was overrepresented among HPV-positive individuals. They also reported 59 non-synonymous and 136 synonymous variants in mtDNA coding genes. Synonymous changes were common in ND5, ND4, Cytb, ND2, and ND1; while non-synonymous changes clustered in ATP6, Cytb, ND5, and ND3. These were predicted to destabilize the structure of Complex I, III, and V subunit proteins [

50].

In addition, Hao et al (2019) identified somatic mtDNA mutations in all six HPV-positive recurrent recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) tissue samples, averaging 1.8 mutations per sample (all heteroplasmic). Among the nine total mutations two were previously unreported, nonsynonymous mutations: A336T in COI and G215D in ND5. The authors claim these could be functionally significant due to the evolutionary conservation of the affected residues [

53]. Likewise, Warowicka et al. (2020) detected 12 somatic point mutations in the mitochondrial ND1 gene in HPV-positive precancerous and cancerous cervical tissues. No mutations were observed in control tissues and were present only in HPV+ cases. 8/12 mutations were missense, altering protein function (p.T67A, p.V11A, p.M156K). All mutations were homoplasmic, suggesting complete dominance of mutated mtDNA in affected cells. A novel mutation, p.M156K, was identified in the transmembrane domain IV [

54].

In a case study of HPV53-positive bilateral multinodular oncocytic hyperplasia (MNOH) of the parotid glands, Kurelac et al (2014) revealed the bilateral presence of a novel homoplasmic mtDNA mutation located in the ND2 subunit of complex I, m.4561T>A [

55]. These observations suggest that the mtDNA copy number and qualitative mtDNA alterations such as base substitutions, indel mutations, and haplogroups are interconnected and may contribute to persistent HPV infection and disease progression. Findings on the changes in mtDNA in HPV-related cancers is summarized in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 1.

Coding-region mutations (e.g., ND1, ND2, COI, ND5), deletions (such as the common 4.977 bp deletion), D-loop variants (C150T, T16172T, D310 repeat), and haplogroup associations contribute to HPV-driven carcinogenesis. Quantitative alterations include both increases and decreases in mtDNA copy number, with changes correlating with cancer risk, tumor stage, and progression. Mixed associations, such as the 10398 polymorphism, further highlight the prognostic complexity of mtDNA alterations in HPV-related disease.

4. Functional Consequences of mtDNA Alterations

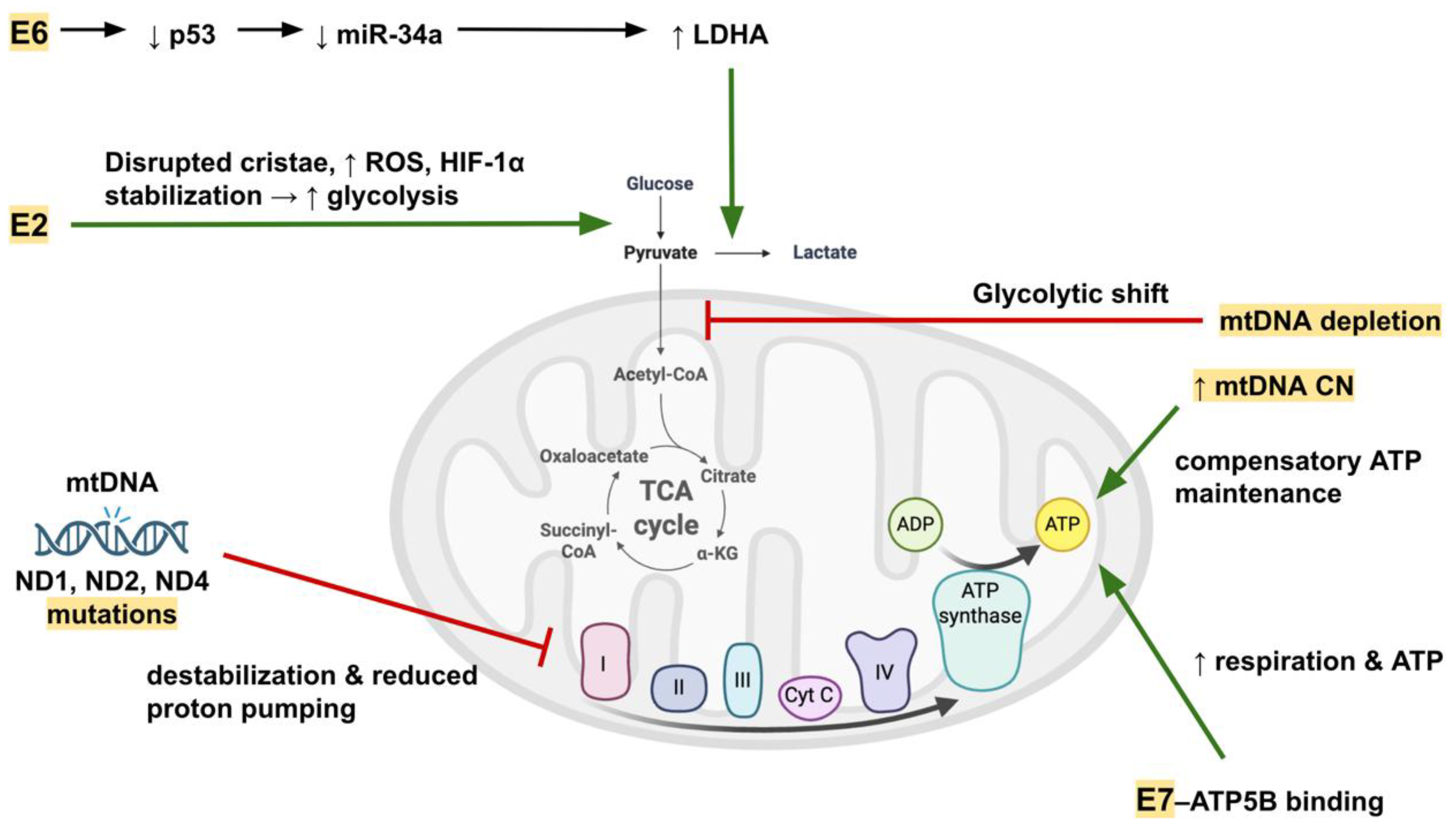

4.1. Effects on Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and Cellular Energy Metabolism

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) alterations in HPV-associated disease often affect genes encoding key components of the electron transport chain (ETC), disrupting oxidative phosphorylation. Pathogenic coding-region mutations such as ND1 p.M156K, ND4 T170P, and ND2 V31E impair structural stability of Complex I subunits, leading to reduced proton pumping efficiency and compromised ATP synthesis. Such defects can decrease respiratory chain capacity and promote compensatory metabolic shifts [

50,

54,

55].

Altered mtDNA copy number also impacts OXPHOS. In cervical lesions, elevated mtDNA content may represent a compensatory mechanism to maintain ATP production despite accumulating mutations or deletions [

19,

48,

49]. In contrast, mtDNA depletion observed in cervical and oral squamous cell carcinomas, as well as in HPV-transformed prostate cancer cells, can impair oxidative capacity and favor a glycolytic phenotype [

50,

51,

52].

Viral oncoproteins directly modulate mitochondrial metabolism. The E7-ATP5B interaction enhances mitochondrial respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and ATP production in HPV-positive cancers, potentially improving cellular fitness [

56]. Conversely, HPV-18 E2 disrupts mitochondrial cristae, increases ROS, and promotes a shift toward aerobic glycolysis via HIF-1α stabilization [

57]. E6-mediated p53 degradation reduces miR-34a, derepressing LDHA and enhancing glycolysis at the expense of oxidative metabolism [

58].

Figure 2 shows how HPV oncoproteins contribute to mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction.

E6 promotes glycolytic shift through p53/miR-34a–mediated upregulation of LDHA, while E2 disrupts cristae integrity, increases ROS, and stabilizes HIF-1α. E7 interacts with ATP5B to influence ATP production. mtDNA mutations (ND1, ND2, ND4) destabilize Complex I and impair proton pumping, whereas mtDNA copy number changes (depletion or compensatory increase) alter ATP synthesis. These alterations collectively shift energy metabolism toward glycolysis while maintaining ATP levels.

4.2. Mitochondrial-Driven Apoptosis Resistance and Cancer Progression

HPV exploits mitochondrial pathways to inhibit apoptosis and promote cancer cell survival. E6 targets and degrades Bak, preventing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), cytochrome c release, and activation of both caspase-dependent and independent death pathways [

59]. Accumulated mtDNA mutations and deletions exacerbate ROS production, creating a self-reinforcing loop of oxidative stress and genomic instability [

54]. This pro-oxidant environment can activate antioxidant transcription factors such as Nrf2 and FoxO3a, with increased expression of downstream enzymes (SOD1, SOD2, catalase) in HPV16 E6 cells, enhancing stress tolerance [

60]. Mitochondrial function also influences apoptosis sensitivity in a cell line–specific manner. In oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, SiHa cells release cytochrome c and activate caspase-9/3, while CaSki cells exhibit Bax/Bcl-XL modulation without cytochrome c release, suggesting differences in mitochondrial permeabilization threshold [

61]. Progressive accumulation of large deletions, such as the common 4.977 bp loss, correlates with transition from low-grade SIL to cervical cancer, implicating mitochondrial genome damage in disease progression [

19].

4.3. Crosstalk Between mtDNA Changes and Nuclear Gene Expression

Mitochondrial dysfunction can trigger retrograde signaling to the nucleus, altering gene expression programs relevant to cancer progression and therapy response. ETC impairment and mtDNA mutations can activate nuclear-encoded antioxidant defenses or repress mitochondrial biogenesis regulators such as PGC-1α and its co-activator ERRα, modulating oxidative metabolism and redox homeostasis [

25,

60]. ROS overproduction can stabilize HIF-1α, driving nuclear expression of glycolytic (PDK1, CAIX) and angiogenic (VEGF) genes that facilitate adaptation to hypoxia. Viral interference with microRNA networks also connects mtDNA status to nuclear metabolism: E6-driven p53 loss downregulates miR-34a, releasing repression of LDHA and reinforcing glycolytic programming [

57,

58,

62]. Mitochondrial non-coding RNAs participate in this crosstalk. E2-mediated downregulation of antisense mitochondrial RNAs (ASncmtRNAs) and induction of SncmtRNA-2 may influence cell cycle regulation and indirectly affect nuclear transcription through miRNA sponging (e.g., miR-620 targeting PML) [

63]. Finally, mitochondrial metabolic state directly influences nuclear programs controlling therapy sensitivity: high OXPHOS activity and antioxidant capacity predict cisplatin and radiation resistance, while high full-length E6 expression suppresses these pathways, increasing sensitivity [

25].

The functional consequences of mtDNA changes are presented in

Table 3.

5. Mitochondria-Directed Therapeutic Strategies and Translational Opportunities in HPV-Associated Cancers

5.1. Mitochondria-Targeted Delivery and Metabolic Modulation

Mitochondria-targeted therapeutics are emerging as a promising strategy in HPV-related and other cancers, with several delivery approaches under development. Liposomes, polymeric and organic nanoparticles that are functionalized using moieties with mitochondrial tropism like triphenylphosphonium (TPP), dequalinium (DQA), and mitochondrial penetrating peptides (MPPs), are demonstrating better pharmacological efficacy than their untargeted counterparts. Their advantage derives from being able to overcome the otherwise impermeable mitochondrial membrane [

64]. A green, carrier-free nanoparticle platform was also developed by co-assembling berberine and catechin (BBR-CC NPs), which exhibited not only improved cellular uptake but also showed synergistic enhancement of ROS accumulation, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and apoptotic signaling in HeLa cells. This highlights the potential of self-assembled phytochemical nanotherapeutics [

65].

Metabolic vulnerabilities in tumors can also be exploited using complementary drugs such as sorafenib and metformin through inhibiting mitochondrial respiratory complexes, reducing ATP synthesis and inducing apoptosis, while also exerting immunomodulatory effects on the tumor microenvironment [

66]. Metabolic addictions such as glutamine, arginine, fatty acid, and glycolytic pathways can also be targeted as parallel approaches. In head and neck cancers, strategies ranging from amino acid depletion therapies to hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) inhibitors and hypoxia-responsive nanocarriers resulted in impaired tumor growth and enhanced radiosensitivity or chemosensitivity [

67]. Supporting this approach, metabolic profiling of HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC cells by Li et al. (2023) revealed that HPV-positive tumors (e.g., HNSCC26) exhibit lower oxidative phosphorylation capacity compensated by glycolysis and an increased kynurenine/tryptophan ratio, implying therapeutic vulnerabilities in glycolytic and IDO pathways, whereas HPV-negative tumors displayed greater metabolic flexibility [

68]. Together, these diverse interventions emphasize the importance of mitochondrial function in cancer therapy, highlighting both novel delivery technologies and metabolic pathway modulation as convergent strategies for overcoming resistance and improving therapy outcomes.

5.2. Oxidative Stress, ROS, and Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis

Beyond biomarkers, mitochondria are now targeted directly with a wide arsenal of natural and synthetic agents, as comprehensively summarized by Cruz-Gregorio et al. (2023), who highlighted compounds such as rotenone, berberine, curcumin, EGCG, and staurosporine, along with synthetic derivatives like TPT-benzimidazolethiol and atovaquone, all of which induce mitochondrial apoptosis through mechanisms including ROS generation, ΔΨm loss, cytochrome c release, and caspase activation, while mitochondrial transplantation was suggested as a futuristic biotherapy [

30]. Krishnamoorthy et al. (2024) also introduced plumbagin as a promising lead compound that disrupted mitochondrial membrane potential, induced apoptosis, blocked EMT and clonogenesis, and sensitized HPV-positive and HPV-negative cervical carcinoma cells to radiotherapy by binding stably to EGFR and attenuating EGF-driven resistance mechanisms [

69]. Other small molecules, such as gamitrinibs (mitochondria-targeted HSP90 inhibitors), imipridones, and pro-oxidants like elesclomol, further disrupt mitochondrial bioenergetics or promote ROS-mediated apoptosis, offering potential to sensitize resistant glioblastoma cells to chemotherapy [

70]. Findings such as these have the potential to be applied into different types of tumors. Additional evidence highlights how mitochondrial dynamics can be therapeutically manipulated in HPV-related cancers and their models. In cervical carcinoma cells, metabolic stress combined with complex I inhibition using low-dose rotenone enhanced ROS generation, stabilized p53, and shifted HeLa cells toward either senescence or apoptosis depending on glucose availability, underscoring the potential of combining metabolic restriction with mitochondria-targeting agents as a context-dependent therapeutic approach [

71]. Complementing experimental plant-based mitochondrial inhibitors, Sharafabad et al. (2024) demonstrated the efficacy of Clostridium novyi-NT spores in HPV-positive cervical cancer models, where spore germination selectively colonized hypoxic tumor regions, triggered cytochrome c release, Bax upregulation, caspase-3 activation, and reduced HIF-1α/VEGF expression, ultimately inducing mitochondrial apoptosis and tumor regression [

72]. Adding to these findings, Mishra et al. (2025) reviewed the critical role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in the pathogenesis and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer. They demonstrated that both enzymatic (SOD, CAT, GPx) and non-enzymatic (GSH, vitamins, polyphenols) antioxidants modulate ROS homeostasis, with compounds like quercetin, resveratrol, and curcumin showing potent pro-apoptotic and anti-HPV effects via regulation of mitochondrial and signaling pathways [

73]. Their findings highlight how antioxidant-rich interventions can both alleviate therapy-induced toxicity and serve as adjuvant or preventive strategies in HPV-driven malignancies. Together, these studies reinforce the multifaceted potential of mitochondria-centered ROS manipulation through synthetic mitochondrial inhibitors, phytochemicals, bacterial oncolytic agents and antioxidants as a versatile approach to promote apoptosis and overcome resistance with the aim of improving therapeutic outcomes in HPV-associated cancers.

5.3. Translational and Advanced Therapeutic Platforms

Recent advances continue to broaden the therapeutic and diagnostic landscape of mitochondria in HPV-related cancers. Van der Pol et al. (2023) demonstrated that circulating tumor-derived mtDNA can be detected in plasma and that its abundance and fragmentation patterns differ from normal mtDNA, with correlations to tumor fraction and potential for improving cancer detection when combined with copy number or mutation data [

74]. Likewise, on a biomarker level, a meta-analysis has confirmed that altered mtDNA copy number is associated with increased head and neck squamous cell carcinoma risk, with a non-linear dose–response pattern, supporting the use of mitochondrial genomic alterations as predictive markers for HPV-associated cancers [

75]. At a broader translational level, Aminuddin et al. (2025) emphasized the significance of mtDNA alterations in HNSCC, highlighting therapeutic strategies such as metformin, dichloroacetate, melatonin, mitochondrial transplantation, and mitoCas9-based genome editing, while stressing the importance of integrating mtDNA datasets into precision oncology [

76]. Preclinical models of HPV-related head and neck cancers further demonstrate that chemoradiation, while suppressing tumor volume and inflammatory cytokine expression, induces broad alterations in mitochondrial respiratory chain gene expression and hypoxia signaling in both liver and brain, suggesting systemic mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to treatment-related morbidity and could be a target for supportive therapies [

77].

Organoid and tumoroid platforms derived from patient cervical tissue and Pap smear samples now provide powerful ex vivo systems to test interventions like the ones mentioned before. HPV-driven oncogenesis, viral integration, and treatment responses including resistance to platinum analogs and sensitivity to agents like gemcitabine can be monitored through these platforms, possibly serving as precision tools for mitochondrial therapy discovery [

78]. Mitochondria can be viewed as both targets and indicators in HPV-related oncogenesis and therapy, bridging metabolic interventions, systemic treatment responses, and personalized organoid testing.

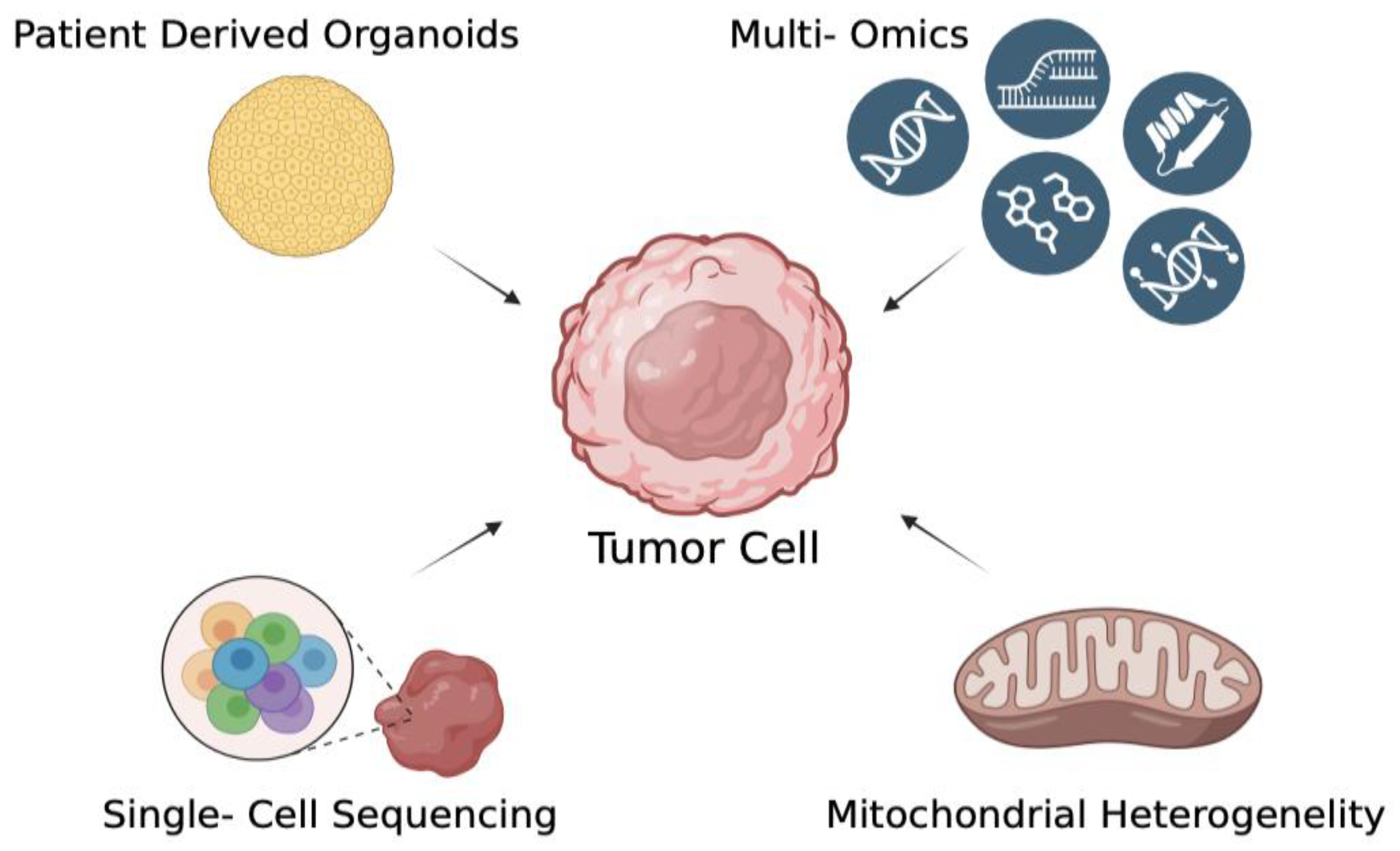

Figure 3.

Advanced modeling strategies for studying mtDNA alterations in HPV-related cancers. A central tumor cell is depicted surrounded by advanced methodologies that enable in-depth characterization of cancer biology. Patient-derived organoids provide physiologically relevant three-dimensional models to recapitulate tumor architecture and microenvironment. Multi-omics strategies (including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) allow for comprehensive profiling of tumor molecular landscapes. Single-cell sequencing resolves intratumoral heterogeneity by capturing genomic and transcriptomic variation at the single-cell level. Finally, the assessment of mitochondrial heterogeneity sheds light on metabolic diversity and mitochondrial dynamics within tumor populations. Together, these complementary approaches offer a multidimensional understanding of tumor development, progression, and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Figure 3.

Advanced modeling strategies for studying mtDNA alterations in HPV-related cancers. A central tumor cell is depicted surrounded by advanced methodologies that enable in-depth characterization of cancer biology. Patient-derived organoids provide physiologically relevant three-dimensional models to recapitulate tumor architecture and microenvironment. Multi-omics strategies (including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) allow for comprehensive profiling of tumor molecular landscapes. Single-cell sequencing resolves intratumoral heterogeneity by capturing genomic and transcriptomic variation at the single-cell level. Finally, the assessment of mitochondrial heterogeneity sheds light on metabolic diversity and mitochondrial dynamics within tumor populations. Together, these complementary approaches offer a multidimensional understanding of tumor development, progression, and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

6. Conclusions

Mitochondrial dysfunction and alterations in mitochondrial DNA are increasingly recognized as active contributors to HPV-driven oncogenesis rather than secondary byproducts of cellular stress. High-risk HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis through multiple, interconnected mechanisms through modulation of biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, oxidative metabolism, and redox balance, thereby promoting metabolic reprogramming, resistance to apoptosis, and tumor adaptability. Qualitative and quantitative changes in mtDNA, including point mutations, insertion-deletions, and copy number variations further strengthen and complicate these effects, influencing both the cellular behavior of HPV-positive tumors and the clinical outcomes.

The evidence highlights the potential of mtDNA alterations as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, as well as therapeutic targets in HPV-associated cancers. Advances in multi-omics profiling, high-throughput sequencing, and physiologically relevant model systems such as patient-derived organoids have provided valuable opportunities for an insight into the structural link between HPV and mitochondrial dysfunction. These platforms, coupled with novel strategies to target mitochondrial bioenergetics and redox homeostasis, show promise for the development of more effective and personalized treatments.

Future research should focus on uncovering the functional consequences of mtDNA heteroplasmy, validating mitochondrial targets in clinically relevant models and integrating mitochondrial profiling into patient stratification studies. Exploiting mitochondrial vulnerabilities as a novel way of intervention in HPV-related cancers could possibly be achieved by bridging the gap between fundamental mitochondrial biology and translational oncology, with the aim of improving outcomes for patients worldwide.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.C., M.S., and G.H.A.; methodology, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., G.K, G.H.A.; software, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O.,G.K..; validation, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; formal analysis, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; investigation, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., G.K.,resources, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; data curation, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.C., M.S.,G.K., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; writing—review and editing, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; visualization, M.O.C., M.S., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; supervision, M.O.C., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; project administration, M.O.C., B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A.; funding acquisition, B.Y., M.O., and G.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- de Sanjosé, S.; Brotons, M.; Pavón, M.A. The Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infection. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018, 47, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, M.L.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Anderson, W.F.; Fakhry, C. Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus–Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, G.; Wentz, A.; Kluz, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sugar, E.; Youngfellow, R.M.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, W.; Gillison, M.L. Sex Differences in Risk Factors and Natural History of Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2016, 213, 1893–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin-Drubin, M.E.; Münger, K. Oncogenic Activities of Human Papillomaviruses. Virus Res 2009, 143, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Banks, L. Inhibition of Bak-Induced Apoptosis by HPV-18 E6. Oncogene 1998, 17, 2943–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.A.; Laimins, L.A. Human Papillomavirus Oncoproteins: Pathways to Transformation. Nature Reviews Cancer 2010, 10, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, I.O.A.; Silva, N.N.T.; Lima, A.A.; da Silva, G.N. Qualitative and Quantitative Changes in Mitochondrial DNA Associated with Cervical Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Environ Mol Mutagen 2024, 65, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Roviello, G.N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Targeting Mitochondrial Therapy in the Regulation of HPV Infection and HPV-Related Cancers. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigis, M.C. The Multifaceted Contributions of Mitochondria to Cellular Metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppen, H.A.L.; Blakely, E.L.; Turnbull, D.M.; Taylor, R.W. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and Human Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2010, 1797, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeyev, M.; Shokolenko, I.; Wilson, G.; LeDoux, S. The Maintenance of Mitochondrial DNA Integrity—Critical Analysis and Update. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5, a012641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reznik, E.; Miller, M.L.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Riaz, N.; Sarungbam, J.; Tickoo, S.K.; Al-Ahmadie, H.A.; Lee, W.; Seshan, V.E.; Hakimi, A.A.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Variation across Human Cancers. Elife 2016, 5, e10769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Ju, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yoon, C.J.; Yang, Y.; Martincorena, I.; Creighton, C.J.; Weinstein, J.N.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Mitochondrial Genomes in Human Cancers. Nat Genet 2020, 52, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindle, R.W. Immune Evasion in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cervical Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2002, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Gong, S.; Singh, P.; Lyu, J.; Bai, Y. The Interaction between Mitochondria and Oncoviruses. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1864, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, D.M.; Bernardi, P.; Chieco-Bianchi, L.; Ciminale, V. Mitochondria as Functional Targets of Proteins Coded by Human Tumor Viruses. Adv Cancer Res 2005, 94, 87–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancers and Mitochondria. Virus Res 2020, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warowicka, A.; Kwasniewska, A.; Gozdzicka-Jozefiak, A. Alterations in MtDNA: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study Associated with Cervical Cancer Development. Gynecol Oncol 2013, 129, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Zaganjor, E.; Haigis, M.C. Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell 2016, 166, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Mambo, E.; Sidransky, D. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in Human Cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4663–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, G.; Hedayat, S.; Vatsiou, A.; Jamin, Y.; Fernández-Mateos, J.; Khan, K.; Lampis, A.; Eason, K.; Huntingford, I.; Burke, R.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Model Treatment Response of Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancers. Science 2018, 359, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losó n, O.C.; Song, Z.; Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 Mediate Drp1 Recruitment in Mitochondrial Fission. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkowska, A.; Domańska-Senderowska, D.; Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K.H.; Pikus, E.; Zielińska, A.; Biskup, L.; Kołodziejska, A.; Madura, P.; Możdżan, M.; Załuska, U.; et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannigrahi, M.K.; Rajagopalan, P.; Lai, L.; Liu, X.; Sahu, V.; Nakagawa, H.; Jalaly, J.B.; Brody, R.M.; Morgan, I.M.; Windle, B.E.; et al. HPV E6 Regulates Therapy Responses in Oropharyngeal Cancer by Repressing the PGC-1α/ERRα Axis. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; He, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Lu, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, D.; et al. Silibinin Induces G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest by Activating Drp1-Dependent Mitochondrial Fission in Cervical Cancer. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 514620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Liu, J.; Fan, W.; Li, R.; Cui Zifeng and Jin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xie, H.; Li, L.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Z.; et al. Gene Knock-out Chain Reaction Enables High Disruption Efficiency of HPV18 E6/E7 Genes in Cervical Cancer Cells. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2022, 24, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucha, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Bhattacharyya, N.P. E2F1 Activates MFN2 Expression by Binding to the Promoter and Decreases Mitochondrial Fission and Mitophagy in HeLa Cells. FEBS Journal 2019, 286, 4525–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Oleinik, N.; Ogretmen, B. HPV16-E7 Oncoprotein Enhances Ceramide-Mediated Lethal Mitophagy by Regulating the Rb/E2F5/Drp1 Signaling Axis. The FASEB Journal 2016, 30, 872.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Roviello, G.N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Targeting Mitochondrial Therapy in the Regulation of HPV Infection and HPV-Related Cancers. Pathogens 2023, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaziu-Todosia Anton, E.; Anton, G.I.; Scripcariu, I.S.; Dumitrașcu, I.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Balmus, I.M.; Ionescu, C.; Visternicu, M.; Socolov, D.G. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Antioxidant Strategies in Cervical Cancer—A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letafati, A.; Taghiabadi, Z.; Zafarian, N.; Tajdini, R.; Mondeali, M.; Aboofazeli, A.; Chichiarelli, S.; Saso, L.; Jazayeri, S.M. Emerging Paradigms: Unmasking the Role of Oxidative Stress in HPV-Induced Carcinogenesis. Infectious Agents and Cancer 2024, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, M.; Kabekkodu, S.P.; Chakrabarty, S. Exploring the Metabolic Alterations in Cervical Cancer Induced by HPV Oncoproteins: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2025, 1880, 189292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, A.J.; Park, J.; Shin, J.M.; Kim, T.H. Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Head and Neck Cancer. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yao, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Liu, C. Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming in Gynecologic Malignant Tumors. J Cancer 2024, 15, 2627–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Liu, T.; Han, C.; Xuan, Y.; Jiang, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. HPV E6/E7 Promotes Aerobic Glycolysis in Cervical Cancer by Regulating IGF2BP2 to Stabilize M6A-MYC Expression. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe-Seyler, K.; Honegger, A.; Bossler, F.; Sponagel, J.; Bulkescher, J.; Lohrey, C.; Hoppe-Seyler, F. Viral E6/E7 Oncogene and Cellular Hexokinase 2 Expression in HPV-Positive Cancer Cell Lines. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 106342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasam, G.; Iqbal, M.A.; Srivastava, A.; Bamezai, R.N.K.; Singh, R.K. HPV18 Oncoproteins Driven Expression of PKM2 Reprograms HeLa Cell Metabolism to Maintain Aerobic Glycolysis and Viability. Virusdisease 2022, 33, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizmendi-Izazaga, A.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Jiménez-Wences, H.; Mendoza-Catalán, M.A.; Martínez-Carrillo, D.N.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Olea-Flores, M.; Dircio-Maldonado, R.; Torres-Rojas, F.I.; Soto-Flores, D.G.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: Role of HPV 16 Variants. Pathogens 2021, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramírez, I.; Carrillo-García, A.; Contreras-Paredes, A.; Ortiz-Sánchez, E.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Lizano, M. Regulation of Cellular Metabolism by High-Risk Human Papillomaviruses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Chai, P.; Shen, Y.; Yao, Y.; Xu, S.; Ge, S.; Jia, R. Lactate and Lactylation in Cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-López, K.G.; Castro-Muñoz, L.J.; Reyes-Hernández, D.O.; García-Carrancá, A.; Manzo-Merino, J. Lactate in the Regulation of Tumor Microenvironment and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1α Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, H.; Xu, H.; Luo, A.; Zhou, F. An Association Analysis between Mitochondrial DNA Content, G10398A Polymorphism, HPV Infection, and the Prognosis of Cervical Cancer in the Chinese Han Population. Tumor Biology 2016, 37, 5599–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardado-Estrada, M.; Medina-Martínez, I.; Juárez-Torres, E.; Roman-Bassaure, E.; MacÍas, L.; Alfaro, A.; Alcántara-Vázquez, A.; Alonso, P.; Gomez, G.; Cruz-Talonia, F.; et al. The Amerindian MtDNA Haplogroup B2 Enhances the Risk of HPV for Cervical Cancer: De-Regulation of Mitochondrial Genes May Be Involved. J Hum Genet 2012, 57, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Chang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y. Mitochondrial C150T Polymorphism Increases the Risk of Cervical Cancer and HPV Infection. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Singh, A.; Sharma, C.; Jain, S.K.; Singh, N. Mutations in the Mitochondrial DNA D-Loop Region Are Frequent in Cervical Cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Zhou, J.; Xu, M.; Lyu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Dai, M.; Li, N.; Hang, D. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Cervical Exfoliated Cells and Risk of Cervical Cancer among HPV-Positive Women. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-awadhi, R.; Alroomy, M.; Al-Waheeb, S.; Alwehaidah, M.S. Altered Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Cervical Exfoliated Cells among High-risk HPV-positive and HPV-negative Women. Exp Ther Med 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabekkodu, S.P.; Bhat, S.; Mascarenhas, R.; Mallya, S.; Bhat, M.; Pandey, D.; Kushtagi, P.; Thangaraj, K.; Gopinath, P.M.; Satyamoorthy, K. Mitochondrial DNA Variation Analysis in Cervical Cancer. Mitochondrion 2014, 16, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R.; Ghosh, S.K.; Choudhury, J.H.; Seram, A.; Sinha, K.; Hussain, M.; Laskar, R.S.; Rabha, B.; Dey, P.; Ganguli, S.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Risk of Oral Cancer: A Report from Northeast India. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumachi, T.; Muskhelishvili, L.; Naito, A.; Furusawa, J.; Fan, C.Y.; Siegel, E.R.; Kadlubar, F.F.; Kumar, U.; Higuchi, M. Increased Distributional Variance of Mitochondrial DNA Content Associated with Prostate Cancer Cells as Compared with Normal Prostate Cells. Prostate 2008, 68, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Ruiz, R.; Yang, L.; Neto, A.G.; Amin, M.R.; Kelly, D.; Achlatis, S.; Roof, S.; Bing, R.; Kannan, K.; et al. Mitochondrial Somatic Mutations and the Lack of Viral Genomic Variation in Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warowicka, A.; Wołuń-Cholewa, M.; Kwaśniewska, A.; Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Alternations in Mitochondrial Genome in Carcinogenesis of HPV Positive Cervix. Exp Mol Pathol 2020, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurelac, I.; Salfi, N.C.; Ceccarelli, C.; Alessandrini, F.; Cricca, M.; Caliceti, U.; Gasparre, G. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Pathogenic Mitochondrial DNA Mutation in Bilateral Multinodular Oncocytic Hyperplasia of the Carotid. Pathology 2014, 46, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschberg, M.; Heuser, S.; Marcuzzi, G.P.; Hufbauer, M.; Seeger, J.M.; Đukić, A.; Tomaić, V.; Majewski, S.; Wagner, S.; Wittekindt, C.; et al. ATP Synthase Modulation Leads to an Increase of Spare Respiratory Capacity in HPV Associated Cancers. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.; Tan, C.L.; Gunaratne, J.; Quek, L.S.; Nei, W.; Thierry, F.; Bellanger, S. Localization of HPV-18 E2 at Mitochondrial Membranes Induces ROS Release and Modulates Host Cell Metabolism. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Su, J.; Xue, S.-L.; Yang, H.; Ju, L.-L.; Ji, Y.; Wu, K.-H.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Hu, J.-F.; et al. HPV E6/P53 Mediated down-Regulation of MiR-34a Inhibits Warburg Effect through Targeting LDHA in Cervical Cancer; 2016; Vol. 6.

- Leverrier, S.; Bergamaschi, D.; Ghali, L.; Ola, A.; Warnes, G.; Akgül, B.; Blight, K.; García-Escudero, R.; Penna, A.; Eddaoudi, A.; et al. Role of HPV E6 Proteins in Preventing UVB-Induced Release of pro-Apoptotic Factors from the Mitochondria. Apoptosis 2007, 12, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; Coronado-Martínez, I.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Lizano, M. E6 Oncoproteins from High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Induce Mitochondrial Metabolism in a Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Model. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, N. Induction of Apoptosis by Hydrogen Peroxide in HPV 16 Positive Human Cervical Cancer Cells: Involvement of Mitochondrial Pathway. Mol Cell Biochem 2008, 310, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara Matei 1, I.N. 2, M.I.M. 3,*, C.I.M. 3,*, C.D.E. 4,5, G.N. 6, S.R.G. 1,2 and M.T. Biomolecular Dynamics of Nitric Oxide Metabolites and HIF1α in HPV Infection. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Villota, C.; Campos, A.; Vidaurre, S.; Oliveira-Cruz, L.; Boccardo, E.; Burzio, V.A.; Varas, M.; Villegas, J.; Villa, L.L.; Valenzuela, P.D.T.; et al. Expression of Mitochondrial Non-Coding RNAs (NcRNAs) Is Modulated by High Risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Oncogenes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 21303–21315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Tao, X.; Dong, D.; Liu, J. Targeted Mitochondrial Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Transl Oncol 2025, 54, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, A.; Guan, F.; Li, W.; Han, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D. A Novel Supramolecule Combining the Pharmacological Benefits of Berberin and Catechin for the Prevention and Treatment of Cervical Cancer. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2024, 698, 134555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih Matar Alsehli; Omar Abdullah Almutairi; Sati Musaad Almutairi; Muqren Geri Almutairi; Salem Ayad Aljohani; Majed Abdullah Alharbi; Najeh Saud Alanazi; Faisal Fahad Almutiri; Yousef Aziz Aloufi; Abdullah Saad Algohani; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Insights into the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications. Evol Stud Imaginative Cult. 2024; pp. 2825–2846. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. jing; Yang, X. xin; Meng, H. xue Mitochondrial Metabolism in Laryngeal Cancer: Therapeutic Mechanisms and Prospects. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2025, 1880, 189335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Chamkha, I.; Verma, G.; Swoboda, S.; Lindstedt, M.; Greiff, L.; Elmér, E.; Ehinger, J. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells Rely on Glycolysis and Display Reduced Oxidative Phosphorylation. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1304106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Sabanayagam, R.; Periyasamy, L.; Muruganantham, B.; Muthusami, S. Plumbagin as a Preferential Lead Molecule to Combat EGFR-Driven Matrix Abundance and Migration of Cervical Carcinoma Cells. Medical Oncology 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, M.; Bamaga, A.; Alkhotani, A.; Alsharif, T.; Abdel-Hamid, G.A.; Selim, M.E.; Alsinani, T.; Albeshri, A.; Badahdah, A.; Basheikh, M.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Alterations in Glioblastoma and Current Therapeutic Targets. Frontiers in Bioscience - Landmark 2024, 29, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.R.; Maurya, N.; Pawar, J.S.; Ghosh, I. A Combined Approach against Tumorigenesis Using Glucose Deprivation and Mitochondrial Complex 1 Inhibition by Rotenone. Cell Biol Int 2016, 40, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafabad, B.E.; Abdoli, A.; Jamour, P.; Dilmaghani, A. The Ability of Clostridium Novyi-NT Spores to Induce Apoptosis via the Mitochondrial Pathway in Mice with HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer Tumors Derived from the TC-1 Cell Line. BMC Complement Med Ther 2024, 24, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Mishra, P.; Dhiman, R.; Bhutia, S.K. The Dual Role of Mitophagy in Cancer and Its Targeting for Effective Anticancer Therapy. Mitophagy in Health and Disease: Mechanisms, Health Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities, 2025; 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, Y.; Moldovan, N.; Ramaker, J.; Bootsma, S.; Lenos, K.J.; Vermeulen, L.; Sandhu, S.; Bahce, I.; Pegtel, D.M.; Wong, S.Q.; et al. The Landscape of Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA in Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Detection. Genome Biol 2023, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, H. Association between Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Medical Science Monitor 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminuddin, A.; Wong, P.K.; Masre, S.F.; Ng, P.Y.; Zakaria, M.A.; Chua, E.W. The Significance of Mitochondrial DNA Changes during the Onset and Progression of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Future Oncology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichaya, E.G.; Molkentine, J.M.; Vermeer, D.W.; Walker, A.K.; Feng, R.; Holder, G.; Luu, K.; Mason, R.M.; Saligan, L.; Heijnen, C.J.; et al. Sickness Behavior Induced by Cisplatin Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy in a Murine Head and Neck Cancer Model Is Associated with Altered Mitochondrial Gene Expression. Behavioural Brain Research 2016, 297, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõhmussaar, K.; Oka, R.; Espejo Valle-Inclan, J.; Smits, M.H.H.; Wardak, H.; Korving, J.; Begthel, H.; Proost, N.; van de Ven, M.; Kranenburg, O.W.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Model Cervical Tissue Dynamics and Viral Oncogenesis in Cervical Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1380–1396.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).