1. Introduction

Gourami aquaculture (Osphronemus goramy) underpins household nutrition and rural livelihoods in Southeast Asia, yet recurrent aeromoniasis caused by A. hydrophila continues to drive acute mortality, growth setbacks, and treatment costs in pond systems [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Across warm-water teleosts, including tilapia, catfish, carp, goldfish, eels, and gourami, motile Aeromonas septicemia (MAS) presents with hemorrhagic septicemia, ulcerative/necrotizing lesions, and high cumulative mortality, depressing pond productivity and encouraging antibiotic reliance [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Within intensive ponds, disease emergence reflects the intersection of host stress, environmental fluctuation, and pathogen virulence, necessitating diagnostics that are both accurate and operational for regional laboratories [15,16,17,18]. While whole-genome sequencing (ANI/dDDH) is the taxonomic gold standard, many laboratories require validated, cost-conscious marker sets for routine identification and surveillance [19,20,21]. Conventional biochemical schemes for Aeromonas show variable performance across facilities, and within Aeromonas, low interstrain divergence and intragenomic rrs heterogeneity can blunt 16S-only calls, motivating faster-evolving, single-copy housekeeping markers [22,23,24]. By contrast, housekeeping genes with a higher evolutionary rate, gyrB and rpoB, provide sharper species discrimination and more stable clades, particularly in concatenated analyses that outperform 16S-only pipelines. Because diagnostics in regional labs must balance accuracy and throughput, we prospectively defined a gyrB-first workflow with rpoB as confirmation and concatenation as an adjudicator for edge cases [24,25,26].

A. hydrophila is a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic freshwater bacterium with opportunistic and zoonotic potential; in fish, clinical syndromes range from peritonitis and bacteremia to ulcerative disease and MAS [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Pathogenicity is multifactorial: lipopolysaccharide and outer-membrane proteins, adhesins (pili, flagella), and a type III secretion system facilitate epithelial invasion and immune evasion, while extracellular products, including aerolysin, hemolysins, and cytotoxic/cytotonic enterotoxins, together with secreted proteases and lipases, drive cytotoxic and hemolytic injury; biofilm formation further sustains persistence and treatment recalcitrance in pond environments [3,4,27,28,29,30]. Given its zoonotic potential and environmental reservoirs, control of A. hydrophila aligns with One-Health objectives linking aquatic animal health, food safety, and environmental stewardship [3,31,32].

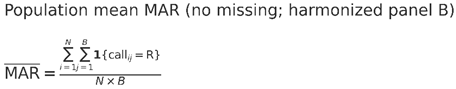

In parallel, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pressure in aquaculture has intensified under therapeutic and prophylactic use, with One-Health implications spanning aquatic reservoirs, food safety, and environmental dissemination [31,32]. The Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index, defined as the proportion of tested agents to which an isolate is resistant, offers a pragmatic indicator of cumulative exposure/selection and is widely applied to Aeromonas under harmonized methods [33,34,35]. For comparability and interpretability, aquatic AST should follow CLSI VET03/VET04 (2020) for test conditions, quality control, and interpretive tables; recent aquaculture studies explicitly implement these standards [33,34,35].

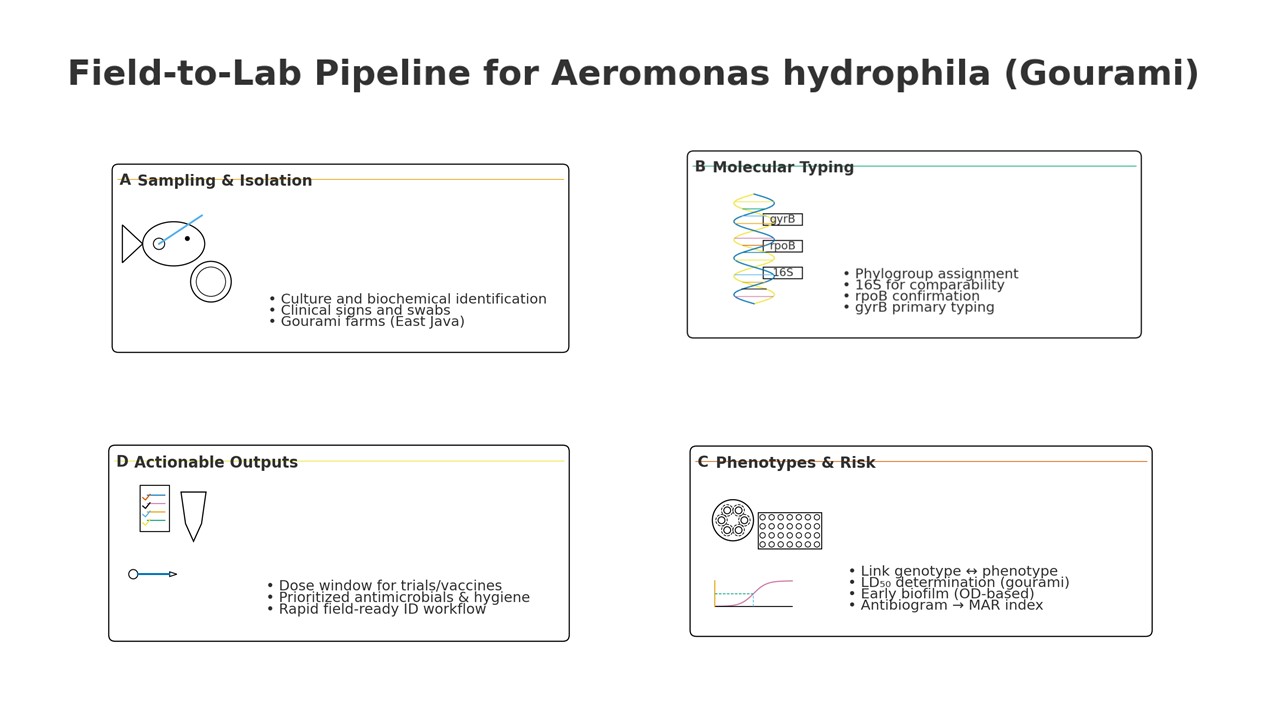

Despite increasing reports of A. hydrophila along Indonesian gourami value chains, few studies benchmark gyrB, rpoB, and 16S rRNA head-to-head using explicit performance metrics (species-level concordance to curated references, node support, within-species subclade counts, misassignment corrections) and then relate marker-defined phylogroups to phenotypes generated under standardized AST [24,25,26]. We hypothesized that gyrB/rpoB would outperform 16S for species assignment and fine-scale resolution, and that MAR, 24-h biofilm attachment, and LD₅₀ would vary by gyrB-defined phylogroups [22,23,24,25,26,32]. To test this, we (i) benchmarked markers against curated references with bootstrap/clade-stability criteria; (ii) evaluated single-locus and concatenated phylogenies (gyrB + rpoB ± 16S); (iii) quantified MAR under CLSI VET03/VET04 (2020); (iv) measured 24-h biofilm attachment (crystal-violet OD₅₉₀); and (v) performed a conspecific gourami LD₅₀ challenge with Reed–Muench estimation (95% CI) [33,34,36,37]. Collectively, this work delivers a practical, cost-conscious genotype–phenotype workflow—gyrB-first, rpoB-reinforced, concatenation-adjudicated—together with MAR/biofilm/LD₅₀ benchmarks that are directly actionable for diagnostics, stewardship, and trial design in gourami aquaculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sites, Sampling, and Isolation

We performed a cross-sectional outbreak investigation at 15 gourami (Osphronemus goramy) farms in Mojokerto, Surabaya, Pasuruan, Blitar, and Sidoarjo (East Java, Indonesia), examining N = 279 fish during suspected aeromoniasis episodes. Fish were eligible if they showed ≥1 predefined external or internal sign (haemorrhagic lesions or dermonecrosis, exophthalmia, fin/tail rot, scale loss, renal swelling, ascites). Fish were humanely euthanized with buffered MS-222 (80–100 mg/L; pH 7.0–7.5) and sampled aseptically from the kidney, liver, spleen, and lesion margins. Swabs were streaked to tryptic soy agar (TSA), Rimler–Shotts medium, and Aeromonas Ampicillin-Dextrin agar, then incubated at 28–30 °C for 24–48 h. Oxidase-positive, Gram-negative facultative rods consistent with Aeromonas were purified and archived at −80 °C (20% glycerol). E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were run as culture QC; a reference A. hydrophila strain (ATCC 35654) served as a positive control in phenotypic/molecular assays with no-template controls in every PCR batch.

Clinical Examination and Case Definitions

At capture, each fish underwent a standardized external exam under light anaesthesia, followed by necropsy within ≤30 min. Trained assessors recorded presence/absence of haemorrhagic flank ulcers/dermonecrosis, exophthalmia, skin ulcers/open wounds, fin (dorsal/caudal) erosion/tail-rot, scale loss/desquamation, barbel erosion, ventral haemorrhagic swellings, and general signs (sluggish swimming, surface floating, anorexia, opercular bubbling); internal signs included renal swelling, coelomic fluid (ascites), intestinal haemorrhage, and gross digestive-tract damage. Key lesions (ulcer, tail-rot, barbel erosion) were graded on a 0–3 ordinal scale using objective thresholds. Prevalence was computed with Wilson 95% CIs by region and overall. Monte-Carlo χ² tests assessed regional heterogeneity with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR control for multiple comparisons. Blank fields were treated as zero (absent).

2.2. Biochemical Profiling and Phenotypic Validation of A. hydrophila

Pure colonies grown 18–24 h on tryptic soy agar or nutrient agar at 28–30 °C were profiled with a standardized panel: colony morphology; Gram stain; motility (hanging drop/semisolid); oxidase and catalase; O/F (fermentative); growth on MacConkey and Rimler–Shotts; TSI/KIA, Simmons citrate, urea, indole/MR/VP; decarboxylases (lysine, ornithine, arginine dihydrolase); carbohydrate fermentations (glucose, galactose, lactose, maltose, mannitol, mannose, sucrose, inositol; dulcitol, raffinose, sorbitol, xylose, inulin); 6.5% NaCl tolerance; H₂S; and vibriostatic O/129 disks (10 µg and 150 µg). Internal coherence rules were enforced (e.g., if sucrose and/or lactose were positive, TSI had to read A/A with gas; any TSI–sugar or H₂S discrepancies were repeated with fresh 18–24 h cultures and appropriate controls). A reference strain (A. hydrophila ATCC 35654) and routine QC organisms were run in parallel. Novobiocin susceptibility was not used for species identification. The expected determinative traits follow Abbott et al. [11], which document typical variability for certain carbohydrates (lactose, inositol).

2.3. Species Confirmation by Molecular Markers

Definitive identification relied on marker-based PCR/Sanger sequencing of

gyrB and

rpoB (± 16S rRNA). An isolate was designated

A. hydrophila only when ≥ 2 loci met BLASTn identity ≥ 99.0% with query coverage ≥ 95% against type-strain references. Phenotypic screening (

Section 2.2) was used for triage/purity checks and to flag potential inconsistencies (O/129 profile) prior to sequencing. Each PCR batch included a positive control (genomic DNA of

A. hydrophila ATCC® 35654™), a no-template control, and an extraction blank; MALDI-TOF MS served as an orthogonal verification where available.

2.4. Genomic DNA Extraction (G-Spin)

Genomic DNA was extracted from purified Aeromonas-compatible colonies re-streaked on TSA and propagated in TSB (28–30 °C, 18–24 h) using the G-Spin Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Intron, cat. 17121) with minor streamlining: 2.8 mL overnight-culture aliquots (duplicate tubes per isolate) were pelleted (12,000 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C), resuspended in 300 µL G-buffer, lysed at 60 °C for 15 min, bound with 250 µL binding buffer on spin columns, washed with 500 µL Wash A and 500 µL Wash B (each 13,000 rpm, 1 min) plus a dry spin, and eluted in 200 µL elution buffer (RT, 1–2 min; 13,000 rpm, 1 min). Extracts were stored at −20 °C; an extraction blank was processed in parallel. DNA integrity was verified on 1–1.5% agarose (TBE, ~100 V, 15–30 min); concentration/purity were assessed by NanoDrop (A260/280, A260/230 when available) and cross-checked by Qubit as needed. Working stocks were normalized to 5–10 ng/µL.

2.5. PCR Amplification and Sanger Sequencing

Loci 16S rRNA,

gyrB, and

rpoB were amplified with published primers (

Table 1) in 25 µL reactions (1× buffer, 1.5–2.5 mM MgCl₂, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µM each primer, 1–1.25 U hot-start polymerase, 5–10 ng template; [thermocycler model]). Cycling was target-optimized:

gyrB/rpoB (95 °C 3 min; 35× 95 °C 30 s, 54–60 °C 30 s, 72 °C 45–60 s; final 72 °C 5 min) and 16S (95 °C 3 min; 30–35× 95 °C 30 s, 52–58 °C 30 s, 72 °C 45–60 s; final 72 °C 5 min). Amplicons were verified on 1.5% agarose and purified (ExoSAP/columns), then Sanger-sequenced bidirectionally; chromatograms were trimmed at Q ≥ 30, inspected for mixed peaks, and assembled (Geneious/UGENE).

2.6. Molecular Identification (16S rRNA, rpoB, gyrB)

Genomic DNA was extracted from pure colonies (18–24 h), and the 16S rRNA, rpoB, and gyrB loci were PCR-amplified and Sanger-sequenced bidirectionally. Chromatograms were quality-filtered (Q≥30), primers trimmed, forward/reverse reads assembled, and low-quality ends removed. Consensus sequences were queried by BLASTn (NCBI nt/curated Aeromonas set); for each isolate locus, we recorded percent identity and query coverage, and the top hit was restricted to Aeromonas type/reference strains. Species calls followed a conservative rule: 16S ≥ 98.7% plus ≥ 95% identity in at least one housekeeping gene (rpoB/gyrB), or multilocus phylogeny when needed. The reference strain ATCC 35654 was included as a positive control and was expected to return high identity to A. hydrophila across all loci.

2.7. Sequence Curation and Phylogenetic Inference

Per-locus consensus sequences were screened for frameshifts/stop codons (protein-coding genes), dereplicated, and aligned with MAFFT L-INS-i; gap-rich columns were removed with trimAl (gappyout). Best-fit nucleotide models were selected by ModelFinder (BIC). Phylogenies were inferred under maximum likelihood (IQ-TREE2; UFBoot: 1000; SH-aLRT: 1000) and Bayesian inference (MrBayes; two runs × four chains; 5–10 M generations; 25% burn-in; ESS > 200). Concatenated analyses ([

gyrB +

rpoB] ± 16S) used partition-by-locus modeling; trees were midpoint-rooted or rooted to an appropriate

Aeromonas outgroup and visualized in iTOL/FigTree. Species assignment required concordant placement versus the concatenated reference and compliance with the BLAST criteria in

Section 2.3.

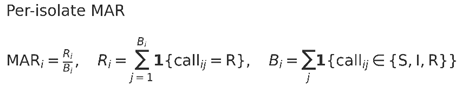

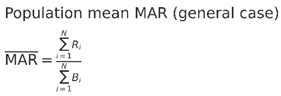

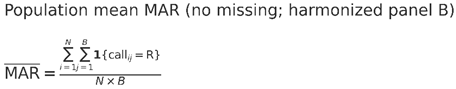

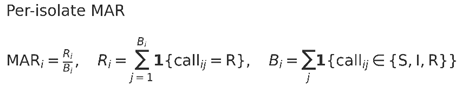

2.8. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and MAR Index

AST used Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) with 0.5 McFarland inocula and incubation at 35 ± 2 °C for 16–18 h. Zone diameters (mm) were interpreted uniformly as S/I/R under a single laboratory standard (CLSI applied consistently); “Intermediate” was not counted as “Resistant.” The 18-agent panel (disk content in µg unless noted) comprised: chloramphenicol 30, streptomycin 10, tetracycline 30, amoxicillin 25, ampicillin 10, ciprofloxacin 5, azithromycin 15, penicillin G 10 U, doxycycline 30, rifampicin 5, erythromycin 15, cefixime 5, clindamycin 2, cefadroxil 30, gentamicin 10, novobiocin 5, vancomycin 30, and oxytetracycline 30 (Table 4). Quality control used E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 with zone diameters within guideline ranges prior to reading test plates. Agents with intrinsic non-susceptibility or limited interpretive utility for Aeromonas (vancomycin, clindamycin, penicillin G, rifampicin, erythromycin, azithromycin, novobiocin) were retained for transparency but excluded from the primary MAR-Relevant endpoint; MAR-All used the full 18-drug panel. Missing measurements were coded NA and excluded from both the numerator and the denominator. Per-isolate MAR was defined as MARᵢ = Rᵢ/Bᵢ, where Rᵢ is the number of drugs called Resistant for isolate i and Bᵢ the number tested for that endpoint; the population mean MAR was (ΣRᵢ)/(ΣBᵢ) (which reduces to ΣR/(N×B) when no values are missing; N = isolates, B = intended panel size). Drug classes followed Table 6; multidrug resistance (MDR) was resistance to ≥1 agent in ≥3 classes. For summary metrics, a population mean multiple-antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was calculated as the number of resistant results divided by the total number of tests:

Notes:

“I” (Intermediate) is not counted as “R”; missing values are excluded from Bi.

Apply the same formulas per endpoint E ∈ {MAR-Relevant, MAR-All} by restricting call ij to drugs in endpoint E.

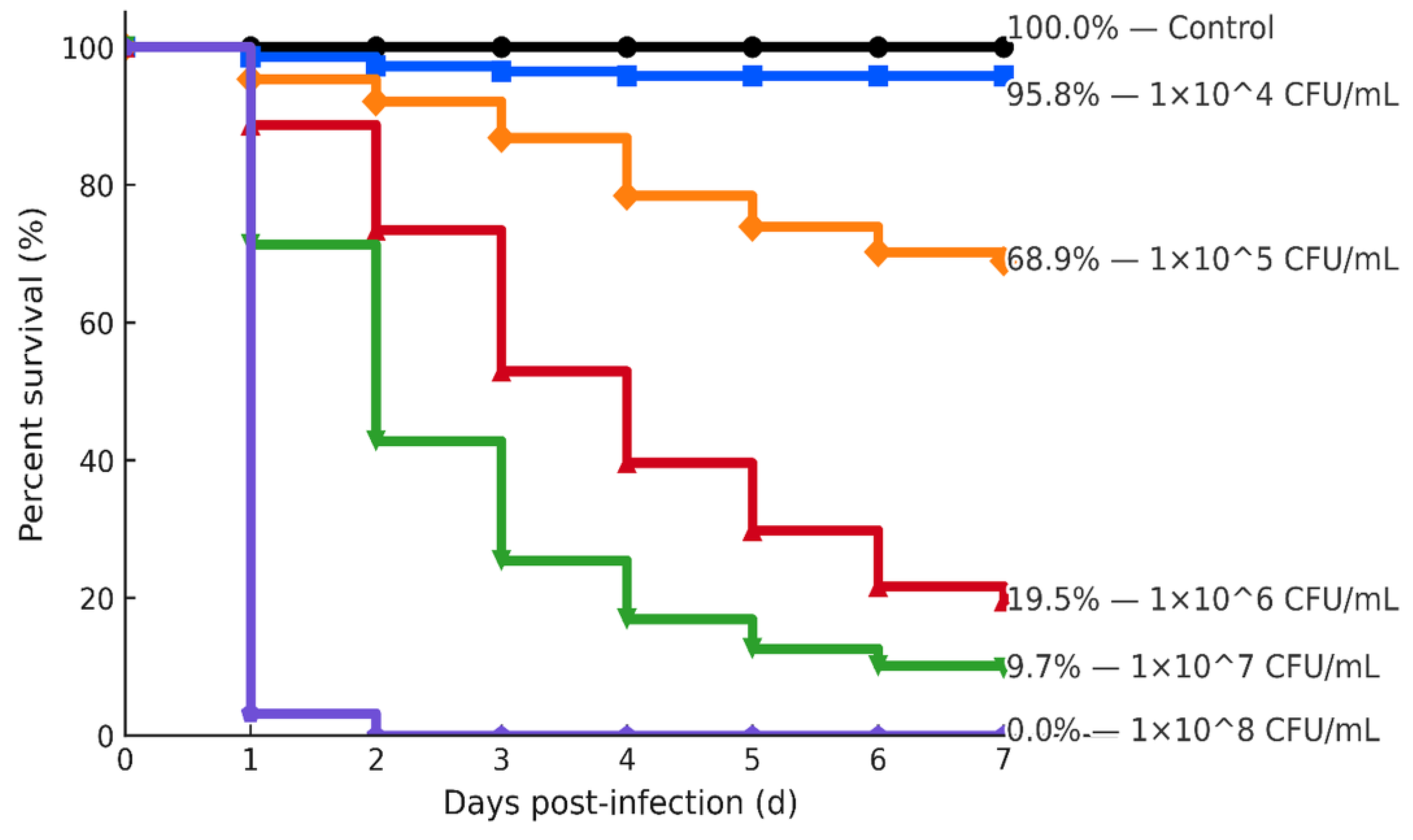

2.9. Experimental Infection and LD₅₀ Determination

Challenge cultures were prepared from ten well-isolated colonies grown 24 h on TSA and inoculated into TSB (30 °C, 24 h), then ten-fold serially diluted in sterile PBS. Viable counts were verified by spread-plate enumeration. Juvenile gourami (Osphronemus goramy) were acclimated for 7 days under standardized water quality (28–30 °C; dissolved oxygen ≥5 mg/L; pH 6.8–7.5; unionized NH₃ <0.02 mg/L), fasted 12 h pre-challenge, and randomly allocated to six dose groups plus one control, with three replicate tanks per group and 10 fish per tank. Fish were anaesthetized in buffered MS-222 and injected intraperitoneally (0.1 mL/fish) with suspensions spanning 1×10⁴ to 1×10⁸ CFU/mL; controls received PBS. Mortality/clinical signs were recorded twice daily for 7 days with predefined humane endpoints. From moribund/dead fish, the kidney and spleen were swabbed for re-isolation and molecular confirmation. Survival across doses was compared by log-rank tests. LD₅₀ (95% CI) was estimated by Reed–Muench and probit regression; concordance within ≤0.30 log₁₀ CFU was required, otherwise a consensus was adjudicated by predefined rules.g.

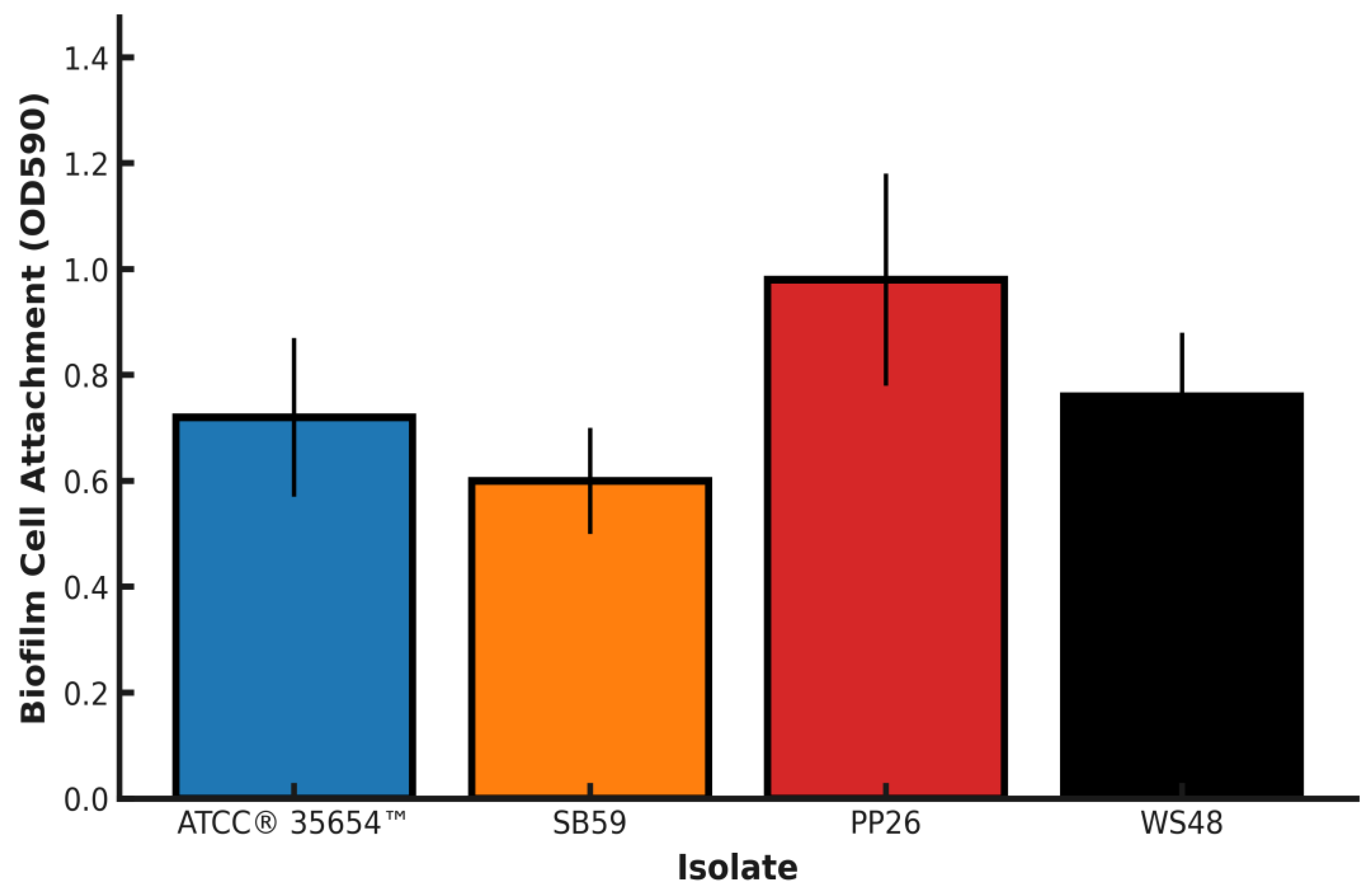

2.10. Quantification of Biofilm Formation

Overnight cultures (TSB, 28–30 °C, 18–24 h) were adjusted to OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.1 and diluted 1:100 in TSB supplemented with 0.25% (w/v) glucose. For each isolate, 200 µL were dispensed into eight technical replicate wells (flat-bottom polystyrene 96-well plate) and incubated statically at 28–30 °C for 24 h. Medium-only wells served as negative controls; A. hydrophila ATCC® 35654™ was included as a positive control. After incubation, wells were gently washed 3× with PBS, air-dried for 30 min, and stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet for 15 min. Excess stain was rinsed off with distilled water (3–4 rinses), and plates were air-dried. Bound dye was solubilized with 200 µL of 95% ethanol (or 30% acetic acid) for 15 min, and the optical density was read at OD590. For each plate, the cut-off (ODc) was defined as the mean OD of negative controls + 3×SD. Isolates were classified per Stepanović criteria: non-adherent (OD ≤ ODc), weak (ODc < OD ≤ 2×ODc), moderate (2×ODc < OD ≤ 4×ODc), strong (OD > 4×ODc). Three independent biological replicates were performed per isolate on different days.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in R (≥4.3) and Python (fixed seed = 12345). Prevalence (%) was estimated under the STRICT denominator (N = 279) with Wilson 95% CIs. Regional heterogeneity was screened by χ² tests with Monte Carlo p-values (20,000 simulations; two-sided), with multiplicity across clinical signs controlled by Benjamini–Hochberg FDR at q = 0.10. Marker performance was compared within fish using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (reporting the median paired difference and effect size r) for continuous/ordinal metrics and McNemar’s tests (exact binomial when sparse) for paired binary outcomes; estimates are accompanied by 95% CIs. Associations between phylogroups (from concatenated trees) and MAR categories used χ²/Fisher’s exact with Cramér’s V; MAR as a proportion was modeled with mixed-effects beta regression (Smithson–Verkuilen adjustment for 0/1), and MAR categories with proportional-odds (ordinal) logistic regression, both including farm as a random intercept and adjusting a priori covariates (fish age, clinical status, prior antimicrobial exposure, water parameters). Biofilm OD₅₉₀ was summarized as median [IQR]; group differences used Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc (BH-FDR), and the odds of high MAR (>0.30) for moderate/strong versus none/weak biofilm were modeled by mixed-effects logistic regression (farm random intercept). Spearman’s ρ quantified correlations between continuous MAR and OD₅₉₀. Finally, survival across doses was compared by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) tests with BH-FDR control across multiple contrasts (q = 0.10), and LD₅₀ (95% CI) was estimated by both Reed–Muench and probit (binomial GLM), with a consensus LD₅₀ reported when the two estimates agreed within 0.30 log₁₀ CFU.

4. Discussion

The external lesion complex documented here, hemorrhagic flank ulcers with erythematous margins, epidermal sloughing/dermonecrosis, fin-margin erosion, diffuse scale loss, and unilateral exophthalmia, aligns closely with canonical motile Aeromonas septicemia (MAS) in warm-water teleosts and with the toxin-protease paradigm of A. hydrophila skin–eye pathology [3,4,7]. Clinically similar constellations have been reported across carp, tilapia, and gourami, with small variations in the frequency of ulcers versus exophthalmia attributable to environmental stressors (temperature spikes, handling, water quality) and host condition [2,10,14,35]. Our field case definition and sampling of lesion margins and kidney/spleen, therefore, follow best-practice diagnostic pathways in which gross recognition initiates, but does not substitute for, culture and gene-target confirmation [11,17,24,25,26]. The advantage of this approach is rapid triage in the face of outbreaks; its limitation is the non-pathognomonic nature of the signs, which overlap with other Gram-negative septicemias, reinforcing the necessity of microbiological and molecular verification [4,11,24,25,26]. Practically, early recognition of this MAS-like presentation enables timely submission for culture/AST and immediate husbandry corrections to reduce mortality while confirmatory work proceeds [17,31,35].

The rank order of signs in gourami (hemorrhagic lesions > exophthalmia > renal swelling > skin ulcers > scale loss) falls within the prevalence envelopes reported for MAS in intensifying aquaculture, supporting the ecological plausibility of A. hydrophila as the principal aetiology in these outbreaks [3,4,7,35]. Inter-district heterogeneity—e.g., elevated skin-ulcer prevalence in Pasuruan and scale-loss clustering in Surabaya—likely reflects differences in water quality, organic loading, stocking density, and handling frequency, all recognized drivers of MAS morbidity gradients at farm scale [3,4,31,35]. Methodologically, our use of Wilson confidence intervals for proportions, Monte-Carlo χ² for sparse/uneven strata, and Benjamini–Hochberg FDR for multiplicity is consistent with surveillance analytics for aquaculture disease mapping and improves inference under unbalanced site sizes [38,39,40]. The principal constraint is limited n at some sites, which widens interval estimates and reduces power for small between-region effects; the management implication is to tailor biosecurity and stress-reduction to local risk profiles while maintaining system-level surveillance for progression to septicemia [3,4,35].

The concordant phenotypic profile across all nine isolates, Gram-negative motile rods, oxidase(+)/catalase(+), fermentative O/F, growth on MacConkey, O/129 resistance, failure to grow at 6.5% NaCl, A/A with gas on TSI (H₂S−), and a canonical carbohydrate panel, matches reference descriptions for A. hydrophila sensu stricto [3,4,11]. Internal coherence checks (TSI–sugar agreement, repeat H₂S) and a reference-strain control mitigate known plasticity in Aeromonas biochemical traits, reducing false assignment among oxidase-positive rods with overlapping reactions [4,11]. Nevertheless, phenotype alone is insufficient for robust species delimitation within Aeromonas because interspecific reaction profiles overlap and laboratory conditions introduce variance; hence the rationale for our combined phenotypic–molecular workflow [4,24,25,26]. Operationally, this tiered scheme preserves turnaround for routine fish-health labs while retaining the specificity required for epidemiology and stewardship decisions [11,24,25,26,33,34].

Single, discrete amplicons at the expected sizes for

16S (~1,505 bp),

rpoB (~558 bp), and

gyrB (~1,103 bp), together with high-identity BLASTn matches to type/reference strains, provide convergent molecular confirmation of

A. hydrophila [22,24,25,26]. Against this backdrop, the three-marker benchmarks (

Table 5) display a consistent performance hierarchy that supports a

gyrB-first strategy [3,24,25,26]. First,

gyrB yields the most reliable species boundaries (95–100% concordance), very strong node support (UFBoot 95–100; BPP 0.98–1.00), and the highest within-species resolution (3–5 subclades) with minimal misassignment correction (0–1/N) (

Table 5) [24,25]. Second, rpoB is nearly comparable at species boundaries (90–97%), with similarly high statistical supports and adequate fine-scale structure (3–4 subclades), making it an ideal confirmatory and complementary marker to reinforce phylogroup calls and test inter-locus concordance [24,26]. By contrast, 16S lags on every metric (70–85% concordance; lower UFBoot/BPP; only 1–2 subclades; more corrections), reflecting its reduced resolving power within this genus [3,4,22,23]. In line with these patterns, within-species structure is richer for gyrB and rpoB, three well-supported subclades versus one for 16S in our material, consistent with broader evidence that rapidly evolving, single-copy housekeeping markers offer superior taxonomic and epidemiologic resolution in Aeromonas, whereas

16S can be confounded by low interstrain divergence and intragenomic

rrs heterogeneity [4,23,24,25,26]. Crucially, misplacements flagged by

16S are fully corrected by concatenation, while gyrB shows no misassignments (0/9), underscoring a pragmatic “

gyrB-first,

rpoB-reinforced” workflow with a concatenated arbiter reserved for edge cases [24,25,26]. These data accord with prior literature demonstrating that housekeeping loci evolving faster than 16S sharpen species-level discrimination in Aeromonas, and that multilocus/concatenated frameworks mitigate locus-specific artifacts and stabilize internal nodes [24,25,26]. Operationally, the resulting hierarchy (

gyrB ≥

rpoB ≫

16S) matches clinical practice that either sequences gyrB/rpoB directly or deploys

gyrB/

rpoB-informed multiplex PCR panels, and aligns with newer multiplex assays that reinforce moving beyond

16S-only workflows [24,25,26,33,34]. Taken together, the evidence justifies

gyrB-based screening and mapping, complemented by

rpoB for edge cases or when higher topological confidence is needed, while retaining

16S solely for cross-study comparability [22,24,25,26].

The susceptibility pattern, uniform activity of ciprofloxacin, partial retention for doxycycline, attenuated activity of oxytetracycline/tetracycline, and broad non-susceptibility to early β-lactams, macrolide/lincosamide, rifamycin, glycopeptide, aminocoumarin, and several aminoglycosides mirrors genus-level pharmacodynamics and AMR landscapes reported for aquaculture-associated Aeromonas [4,31,35,38,47]. High MAR values (median 0.778; range 0.556–0.944) are consonant with contemporary reports linking multidrug resistance to antibiotic exposure histories, environmental reservoirs, and mobile resistomes in pond systems [28,31,35,42]. Strengths include a broad agent panel and transparent counting rules; limitations include reliance on disk diffusion without MIC corroboration and the use of surrogate rather than Aeromonas-specific breakpoints, which can complicate inter-study comparability and stewardship translation [33,34,35].

Programmatically, ciprofloxacin emerges as the only consistently active agent in this panel and doxycycline as a conditional option, but both warrant MIC confirmation and stewardship guardrails to minimize quinolone/tetracycline resistance selection; at farm level, reducing non-therapeutic antibiotic pressure and improving hygiene to disrupt biofilm-mediated persistence are immediate priorities [31,33,34,35,37,39,40]. Our use of MAR-Relevant as the primary endpoint avoids inflation from agents with intrinsic non-susceptibility in Aeromonas, yielding a conservative yet operational estimate of resistance burden (mean 0.646, median 0.636; range 0.364–0.909) [4,32]. Despite this conservative framing, the cohort still exhibits high multidrug resistance, ciprofloxacin is the only uniformly active agent, and tetracycline activity remains partial (doxycycline > oxytetracycline ≥ tetracycline), supporting immediate stewardship adjustments (de-emphasizing aminopenicillins/early cephalosporins and macrolide/lincosamide classes) and genotype-aware interventions aligned to gyrB-defined phylogroups [31,35]. Beyond drug susceptibility, 24-h biofilm attachment differed across

gyrB-defined phylogroups, indicating that lineage structure may modulate surface persistence and treatment recalcitrance in pond environments (

Figure 5) [38,39,40,47]. In the conspecific gourami challenge, a clear dose–response yielded an LD₅₀ of ~3–5 × 10⁵ CFU mL⁻¹ with no mortality in PBS controls, providing calibrated sublethal/lethal doses for downstream vaccine or therapeutic trials (

Figure 6) [37]. Together, these phenotype linkages

, high MAR, variable biofilm, and calibrated LD₅₀

, support a control framework that prioritizes (i) stewardship built around agents with retained activity, (ii) biofilm-targeted husbandry and sanitation, and (iii) challenge models tuned to field-realistic virulence for product evaluation

[39,40].

Key limitations include the modest sample size (n = 9), disk diffusion without MIC/E-test validation for key agents, and reliance on surrogate breakpoints where Aeromonas-specific criteria are unavailable. As the dataset expands, adding rpoB, validating subclades by cgMLST/shallow WGS, and incorporating MIC-based confirmation for ciprofloxacin/doxycycline will strengthen inference; public deposition of sequences, alignments, and trees will facilitate reproducibility and independent re-analysis [21,33,34]. Inter-isolate variation in early biofilm attachment (crystal-violet OD₅₉₀: PP26 > ATCC 35654 ≈ WS48 > SB59) is biologically credible and consistent with evidence that stronger early adhesion predicts persistence, tolerance, and opportunities for horizontal gene transfer in biofilm communities [38,39,40,41]. Our static 96-well assay and the planned ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis with multiplicity control follow accepted methodological standards [19,41], but translation to ponds should account for the sensitivity of OD-based readouts to substratum/material properties and hydrodynamics; confirmatory assays under flow or on relevant aquaculture substrates are warranted [38,39,40]. In the conspecific gourami challenge, a clear dose–response yielded LD₅₀ ≈ 3–5 × 10⁵ CFU mL⁻¹ with no mortality in PBS controls, providing calibrated sublethal/lethal doses for downstream vaccine or therapeutic trials. The inoculum-dependent survival gradient—rapid mortality at ≥10⁷–10⁸ CFU mL⁻¹, aligns with dose–mortality envelopes reported for warm-water teleost challenges with pathogenic A. hydrophila [13,42]. Together with the biofilm findings, these data delineate both persistence and lethality axes for Indonesian isolates and specify evidence-based windows (~10⁵ CFU mL⁻¹ sublethal; 10⁶–10⁷ CFU mL⁻¹ lethal) for product evaluation and pathophysiology studies [33,34,38].

Across clinical, molecular, phylogenetic, resistance, biofilm, and challenge analyses, the data converge on the conclusion that A. hydrophila is the principal aetiology of the investigated gourami outbreaks and that circulating Indonesian isolates combine high multidrug resistance with variable biofilm capacity and a lethal challenge window centered on 10⁶–10⁷ CFU mL⁻¹ [44,45,46]. These findings endorse a gyrB-first, rpoB-reinforced, concatenation-adjudicated diagnostic pipeline and support stewardship and husbandry measures targeted to lineage-specific risks, including sanitation/engineering controls focused on strong biofilm formers [43,47]. Actionable implications and next steps and support the a priori hypothesis while yielding actionable implications: (i) adopt a gyrB-first genotyping workflow with rpoB confirmation and concatenation for edge cases; (ii) implement stewardship that de-emphasizes aminopenicillins/early cephalosporins and macrolide/lincosamide classes, while verifying ciprofloxacin and doxycycline activity by MIC before field use [48]; (iii) prioritize sanitation/engineering controls targeted at strong biofilm formers [43,47]; and (iv) standardize efficacy trials within the calibrated windows (~10⁵ CFU mL⁻¹ sublethal; 10⁶–10⁷ CFU mL⁻¹ lethal) [44,45,46]. Remaining gaps—already noted above—map directly to near-term workstreams that will improve precision in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention: MIC/Etest confirmation and breakpoint harmonization (CLSI VET03/VET04 (2020) alignment) [48]; WGS-level epidemiology with resistome/virulome and recombination analyses [44,46]; biofilm validation under flow/on relevant aquaculture substrates [43,47]; multi-route challenge harmonization (to benchmark route/stress effects on LD₅₀) [45]; and integrated farm-level covariates (water quality, management, antimicrobial use) to refine risk models and intervention targeting.

Figure 1.

External clinical signs in farmed gourami (Osphronemus goramy). (a) Haemorrhagic flank ulcer with hyperaemic margins and erosion of the adjacent dorsal fin (red arrow). (b) Longitudinal epidermal sloughing forming a pale necrotic plaque along the dorsal flank with adjacent scale loss and dorsal-fin base erosion (red arrow). (c) Severe unilateral exophthalmia with multifocal cutaneous erosions and scale loss (red arrow). (d–e), d = frayed dorsal/caudal/anal fins (tail-rot); e = diffuse integument pallor with scale loss; no overt exophthalmia or large haemorrhagic ulcer visible.

Figure 1.

External clinical signs in farmed gourami (Osphronemus goramy). (a) Haemorrhagic flank ulcer with hyperaemic margins and erosion of the adjacent dorsal fin (red arrow). (b) Longitudinal epidermal sloughing forming a pale necrotic plaque along the dorsal flank with adjacent scale loss and dorsal-fin base erosion (red arrow). (c) Severe unilateral exophthalmia with multifocal cutaneous erosions and scale loss (red arrow). (d–e), d = frayed dorsal/caudal/anal fins (tail-rot); e = diffuse integument pallor with scale loss; no overt exophthalmia or large haemorrhagic ulcer visible.

Figure 2.

(A) Heatmap of regional prevalence (%) of clinical signs in gourami (STRICT case definition). Cell values are point estimates; ● denotes signs with a significant between-region effect by omnibus Monte-Carlo χ² with BH–FDR correction (q < 0.05). Color scale fixed to 0–50% from orange (low) to red (high). (B) Region-specific adjusted odds ratios (aOR) versus Blitar for scale loss/desquamation (left) and skin ulcers/open wounds (right). Points show aOR and bars the 95% CI on a log scale; the vertical dashed line marks aOR = 1. Estimates are from logistic models on regional aggregates with Haldane–Anscombe correction for zero cells.

Figure 2.

(A) Heatmap of regional prevalence (%) of clinical signs in gourami (STRICT case definition). Cell values are point estimates; ● denotes signs with a significant between-region effect by omnibus Monte-Carlo χ² with BH–FDR correction (q < 0.05). Color scale fixed to 0–50% from orange (low) to red (high). (B) Region-specific adjusted odds ratios (aOR) versus Blitar for scale loss/desquamation (left) and skin ulcers/open wounds (right). Points show aOR and bars the 95% CI on a log scale; the vertical dashed line marks aOR = 1. Estimates are from logistic models on regional aggregates with Haldane–Anscombe correction for zero cells.

Figure 3.

Endpoint PCR confirmation of A. hydrophila isolates targeting (A) 16S rRNA (~1,505 bp), (B) rpoB (~558 bp), and (C) gyrB (~1,103 bp). M: 1-kb DNA ladder. Lanes 1–9: 1 = WS38, 2 = TM25, 3 = KS77, 4 = PP26, 5 = GB59, 6 = SB59, 7 = SB66, 8 = SS26, 9 = WS48.

Figure 3.

Endpoint PCR confirmation of A. hydrophila isolates targeting (A) 16S rRNA (~1,505 bp), (B) rpoB (~558 bp), and (C) gyrB (~1,103 bp). M: 1-kb DNA ladder. Lanes 1–9: 1 = WS38, 2 = TM25, 3 = KS77, 4 = PP26, 5 = GB59, 6 = SB59, 7 = SB66, 8 = SS26, 9 = WS48.

Figure 4.

PCR amplification and phylogenetic placement (top panels) of A. hydrophila isolates. (A) 16S rRNA (~1,505 bp), (B) rpoB (~558 bp), and (C) gyrB (~1,103 bp). Gels: M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1–10: 1 = A. hydrophila ATCC® 35654™ (positive control), 2 = TM25, 3 = KS77, 4 = PP26, 5 = GB59, 6 = SB59, 7 = SB66, 8 = SS26, 9 = WS48, 10=WS38. All isolates produced a single band at the expected size; no bands were observed in the no-template control (not shown). Trees: maximum-likelihood; scale bar = substitutions/site; node support shown as UFBoot (1,000)/SH-aLRT (1,000). Study isolates are highlighted in blue, the ATCC reference in red, and outgroups in orange. bp, base pairs.

Figure 4.

PCR amplification and phylogenetic placement (top panels) of A. hydrophila isolates. (A) 16S rRNA (~1,505 bp), (B) rpoB (~558 bp), and (C) gyrB (~1,103 bp). Gels: M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1–10: 1 = A. hydrophila ATCC® 35654™ (positive control), 2 = TM25, 3 = KS77, 4 = PP26, 5 = GB59, 6 = SB59, 7 = SB66, 8 = SS26, 9 = WS48, 10=WS38. All isolates produced a single band at the expected size; no bands were observed in the no-template control (not shown). Trees: maximum-likelihood; scale bar = substitutions/site; node support shown as UFBoot (1,000)/SH-aLRT (1,000). Study isolates are highlighted in blue, the ATCC reference in red, and outgroups in orange. bp, base pairs.

Figure 5.

Early biofilm cell attachment (OD590) of A. hydrophila isolates. Bar heights represent mean crystal-violet absorbance at 590 nm after incubation on polystyrene; whiskers denote SD. Isolates: ATCC® 35654™, SB59, PP26, WS48. Replication, inoculum density, incubation time/temperature, and wash/fix/stain parameters are reported in Methods.

Figure 5.

Early biofilm cell attachment (OD590) of A. hydrophila isolates. Bar heights represent mean crystal-violet absorbance at 590 nm after incubation on polystyrene; whiskers denote SD. Isolates: ATCC® 35654™, SB59, PP26, WS48. Replication, inoculum density, incubation time/temperature, and wash/fix/stain parameters are reported in Methods.

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier survival across inoculum doses of A. hydrophila. Lines show survival over 7 days for control and 10⁴–10⁸ CFU/mL; right labels indicate day-7 survival (%). n per group, route, and environmental parameters are in Methods.

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier survival across inoculum doses of A. hydrophila. Lines show survival over 7 days for control and 10⁴–10⁸ CFU/mL; right labels indicate day-7 survival (%). n per group, route, and environmental parameters are in Methods.

Table 1.

Housekeeping gene primers and cycling parameters.

Table 1.

Housekeeping gene primers and cycling parameters.

| Target |

Primer

(name) |

Sequence (5′→3′) |

Amplicon (bp) |

Annealing (°C) |

Reference† |

| gyrB |

Forward (gyrB3F) |

TCCGGCGGTCTGCACGGCGT |

~1100 |

55 |

Yáñez et al., [25]; Korczak et al., [26] |

| Reverse (gyrB14R) |

TTGTCCGGGTTGTACTCGTC |

| rpoB |

Forward (PasrpoB-L) |

GCAGTSGAAAGARTTCTTTGTTC |

~560 |

54 |

Korczak et al., [26] |

Reverse

(RpoB-R) |

GTTGCATGTTNGNACCCAT |

| 16S rRNA |

Forward (27F/27f-CM) |

AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG |

~1500 |

56 |

Morandi et al [23] |

| Reverse (1492R) |

TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT |

Table 2.

Regional prevalence of clinical signs in gourami (STRICT main analysis).

Table 2.

Regional prevalence of clinical signs in gourami (STRICT main analysis).

| Clinical sign |

Mojokerto x/N (%) |

Surabaya x/N (%) |

Pasuruan x/N (%) |

Blitar x/N (%) |

Sidoarjo x/N (%) |

Monte Carlo p (FDR q) |

Overall (x/N, % [95% CI]) |

| N (fish examined) |

N = 20 |

N = 35 |

N = 20 |

N = 164 |

N = 40 |

, |

N = 279 |

| Hemorrhagic lesions |

5/20 (25.0%) |

7/35 (20.0%) |

6/20 (30.0%) |

29/164 (17.7%) |

10/40 (25.0%) |

0.6222 (0.6283) |

57/279 (20.4%) [16.1–25.5] |

| Exophthalmia |

4/20 (20.0%) |

5/35 (14.3%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

28/164 (17.1%) |

9/40 (22.5%) |

0.2588 (0.3926) |

46/279 (16.5%) [12.6–21.3] |

Skin ulcers/

open wounds |

1/20 (5.0%) |

4/35 (11.4%) |

8/20 (40.0%) |

20/164 (12.2%) |

2/40 (5.0%) |

0.0031 (0.0132) |

35/279 (12.5%) [9.2–16.9] |

| Fin erosion |

0/20 (0.0%) |

0/35 (0.0%) |

2/20 (10.0%) |

15/164 (9.1%) |

6/40 (15.0%) |

0.1021 (0.2211) |

23/279 (8.2%) [5.6–12.1] |

Scale loss/

desquamation |

0/20 (0.0%) |

10/35 (28.6%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

21/164 (12.8%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.0004 (0.0059) |

31/279 (11.1%) [7.9–15.3] |

| Renal swelling |

6/20 (30.0%) |

0/35 (0.0%) |

3/20 (15.0%) |

22/164 (13.4%) |

7/40 (17.5%) |

0.0305 (0.0991) |

38/279 (13.6%) [10.1–18.1] |

| Intestinal hemorrhage |

0/20 (0.0%) |

3/35 (8.6%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

18/164 (11.0%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.0505 (0.1312) |

21/279 (7.5%) [5.0–11.2] |

| Ascites (abdominal fluid) |

1/20 (5.0%) |

1/35 (2.9%) |

1/20 (5.0%) |

9/164 (5.5%) |

5/40 (12.5%) |

0.4428 (0.5233) |

17/279 (6.1%) [3.8–9.5] |

| Digestive-tract damage |

0/20 (0.0%) |

1/35 (2.9%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

0/164 (0.0%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.1298 (0.2412) |

1/279 (0.4%) [0.1–2.0] |

| Sluggish swimming |

2/20 (10.0%) |

0/35 (0.0%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

0/164 (0.0%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.0027 (0.0132) |

2/279 (0.7%) [0.2–2.6] |

| Anorexia (loss of appetite) |

1/20 (5.0%) |

2/35 (5.7%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

3/164 (1.8%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.2996 (0.3926) |

6/279 (2.2%) [1.0–4.6] |

| Surface floating tendency |

0/20 (0.0%) |

0/35 (0.0%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

3/164 (1.8%) |

0/40 (0.0%) |

0.6283 (0.6283) |

3/279 (1.1%) [0.4–3.1] |

| Bubbling via operculum |

0/20 (0.0%) |

2/35 (5.7%) |

0/20 (0.0%) |

2/164 (1.2%) |

1/40 (2.5%) |

0.3020 (0.3926) |

5/279 (1.8%) [0.8–4.1] |

Table 3.

Biochemical characteristics of A. hydrophila.

Table 3.

Biochemical characteristics of A. hydrophila.

| Parameter |

Result of biochemical test |

| Colony morphology |

Cream, Circular, Convex, Entire, Echinulate |

| Gram stain |

Gram Negative |

| Shape |

rod |

| O/F |

Fermentative |

| Motility |

motile |

| Oxidase, Catalase, Methyl Red (MR), Simmons citrate, Gelatinase, Arginine dihydrolase (ADH), Lysine decarboxylase (LDH). |

+ |

| 6.5% NaCl growth, Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), Urease, H₂S production; Vibriostatic O/129 (10/150 µg) |

- |

| TSIA |

A/A, G |

| Acid production from: |

|

- D - Glucose, D-Galaktose, Lactose, Maltose,

D-Mannitol, D-Mannose, and Sucrose |

+ |

- Dulcitol, Raffinose, D-Sorbitol, D-Xylose, Inositol,

and Inulin |

- |

Table 4.

Gene-based identification of Aeromonas isolates: percent identity and coverage across three loci (Species call = A. hydrophila).

Table 4.

Gene-based identification of Aeromonas isolates: percent identity and coverage across three loci (Species call = A. hydrophila).

| Isolate |

16S rRNA (%ID) |

16S (%Cov) |

rpoB (%ID) |

rpoB (%Cov) |

gyrB (%ID) |

gyrB (%Cov) |

Species call |

| WS38 |

99.49 |

99 |

99.24 |

99 |

98.23 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| TM25 |

99.58 |

99 |

99.05 |

99 |

98.88 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| KS77 |

99.59 |

99 |

99.85 |

99 |

98.25 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| PP26 |

99.38 |

99 |

99.43 |

99 |

98.3 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| GB59 |

99.29 |

99 |

99.64 |

99 |

98.98 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| SB59 |

99.35 |

99 |

99.45 |

99 |

98.05 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| SB66 |

99.44 |

99 |

99.8 |

99 |

98.75 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| SS26 |

99.18 |

99 |

99.1 |

99 |

98.3 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

| WS48 |

99.63 |

99 |

99.6 |

99 |

98.2 |

98 |

A. hydrophila |

Table 5.

Comparative performance benchmarks for gyrB, rpoB, and 16S rRNA in species-level concordance and fine-scale phylogenetic resolution (A. hydrophila).

Table 5.

Comparative performance benchmarks for gyrB, rpoB, and 16S rRNA in species-level concordance and fine-scale phylogenetic resolution (A. hydrophila).

| Metric |

gyrB |

16S rRNA |

rpoB |

| Species-level concordance to reference (%) |

≥95–100 |

70–85 |

90–97 |

| Median UFBoot at species node (ML) |

95–100 |

70–90 |

93–100 |

| Median BPP at species node (BI) |

0.98–1.00 |

0.85–0.98 |

0.98–1.00 |

| No. of well-supported subclades |

3–5 |

1–2 |

3–4 |

| Misassignment correction (n/N) |

0–1/N |

1–3/N |

0–1/N |

Table 6.

Aggregate antimicrobial susceptibility of A. hydrophila isolates (n=9) from giant gourami (Osphronemus goramy).

Table 6.

Aggregate antimicrobial susceptibility of A. hydrophila isolates (n=9) from giant gourami (Osphronemus goramy).

| Antimicrobial agent (number of strains tested) |

Abbrev |

Drug class |

AST disk content |

Susceptible n (%) |

Intermediate n (%) |

Resistant n (%) |

| Chloramphenicol (9) |

CHL |

Amphenicol |

30 µg |

0 (0.00) |

3 (33.33) |

6 (66.67) |

| Streptomycin (9) |

STR |

Aminoglycoside |

10 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Tetracycline (9) |

TET (TE) |

Tetracycline |

30 µg |

4 (44.44) |

0 (0.00) |

5 (55.56) |

| Amoxicillin (9) |

AMX (AML) |

β-lactam – Aminopenicillin |

25 µg |

1 (11.11) |

4 (44.44) |

4 (44.44) |

| Ampicillin (9) |

AMP |

β-lactam – Aminopenicillin |

10 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Ciprofloxacin (9) |

CIP |

Fluoroquinolone |

5 µg |

9 (100.00) |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

| Azithromycin (9) |

AZM |

Macrolide (Azalide) |

15 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Penicillin G (benzylpenicillin) (9) |

PEN (P) |

β-lactam – Natural penicillin |

10 U |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Doxycycline (9) |

DOX (DO) |

Tetracycline |

30 µg |

7 (77.78) |

0 (0.00) |

2 (22.22) |

| Rifampicin (9) |

RIF |

Rifamycin |

5 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Erythromycin (9) |

ERY (E) |

Macrolide |

15 µg |

2 (22.22) |

2 (22.22) |

5 (55.56) |

| Cefixime (9) |

CFM |

Cephalosporin |

5 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Clindamycin (9) |

CLI (DA) |

Lincosamide |

2 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Cefadroxil (9) |

CFD |

Cephalosporin |

30 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Gentamicin (9) |

GEN (CN) |

Aminoglycoside |

10 µg |

2 (22.22) |

0 (0.00) |

7 (77.78) |

| Novobiocin (9) |

NB |

Aminocoumarin (GyrB inhibitor) |

5 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Vancomycin (9) |

VAN (VA) |

Glycopeptide |

30 µg |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (100.00) |

| Oxytetracycline (9) |

OXT (OT) |

Tetracycline |

30 µg |

5 (55.56) |

0 (0.00) |

4 (44.44) |

Table 7.

Distribution of antibiotic resistance (%) of A. hydrophila isolates and MAR index.

Table 7.

Distribution of antibiotic resistance (%) of A. hydrophila isolates and MAR index.

| Bacterial Code |

Isolates Source |

No. of Resistant Antibiotics |

Resistance Profile |

Number of Antibiotic Classes |

MAR Index |

Stance Level |

| WS38 |

Gouramy |

10 |

STR, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, CFM, CLI, CFD, NB, VAN |

9 |

0.556 |

MDR |

| TM25 |

Gouramy |

10 |

STR, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, CFM, CLI, CFD, NB, VAN |

9 |

0.556 |

MDR |

| KS77 |

Gouramy |

11 |

STR, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN |

9 |

0.611 |

MDR |

| PP26 |

Gouramy |

12 |

CHL, STR, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN |

10 |

0.667 |

MDR |

| GB59 |

Gouramy |

14 |

CHL, STR, TET, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, ERY, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN |

12 |

0.778 |

MDR |

| SB59 |

Gouramy |

16 |

CHL, STR, TET, AMX, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, ERY, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN, OXT |

12 |

0.889 |

MDR |

| SB66 |

Gouramy |

16 |

CHL, STR, TET, AMX, AMP, AZM, P, RIF, ERY, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN, OXT |

12 |

0.889 |

MDR |

| SS26 |

Gouramy |

17 |

CHL, STR, TET, AMX, AMP, AZM, P, DOX, RIF, ERY, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN, OXT |

12 |

0.944 |

MDR |

| WS48 |

Gouramy |

17 |

CHL, STR, TET, AMX, AMP, AZM, P, DOX, RIF, ERY, CFM, CLI, CFD, GEN, NB, VAN, OXT |

12 |

0.944 |

MDR |