Highlights

Grab samples from four lakes – two highly impacted, two low impact – tested for ESBL-producing E. coli using membrane filtration and Quanti-Tray formats with ceftriaxone

Membrane filtration and Quanti-Tray formats demonstrated qualitative and quantitative agreement for CRO-resistant E. coli measurements from lake water samples

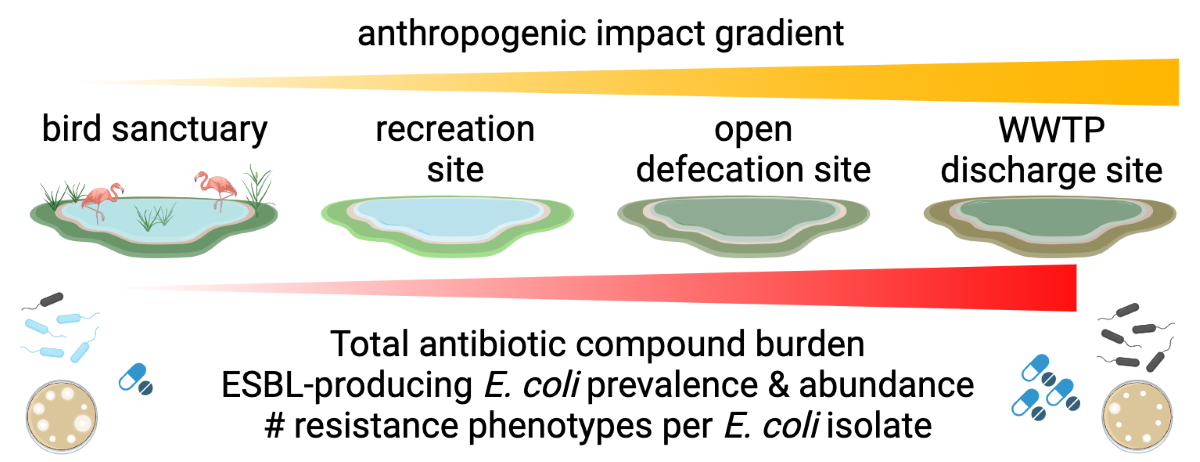

E. coli, ESBL-Ec, ESBL-Ec to E. coli ratio, and antibiotic compound prevalence and abundance trends were consistent with anthropogenic impact gradient

Ceftriaxone performed poorly for screening ESBL-Ec from lake water samples

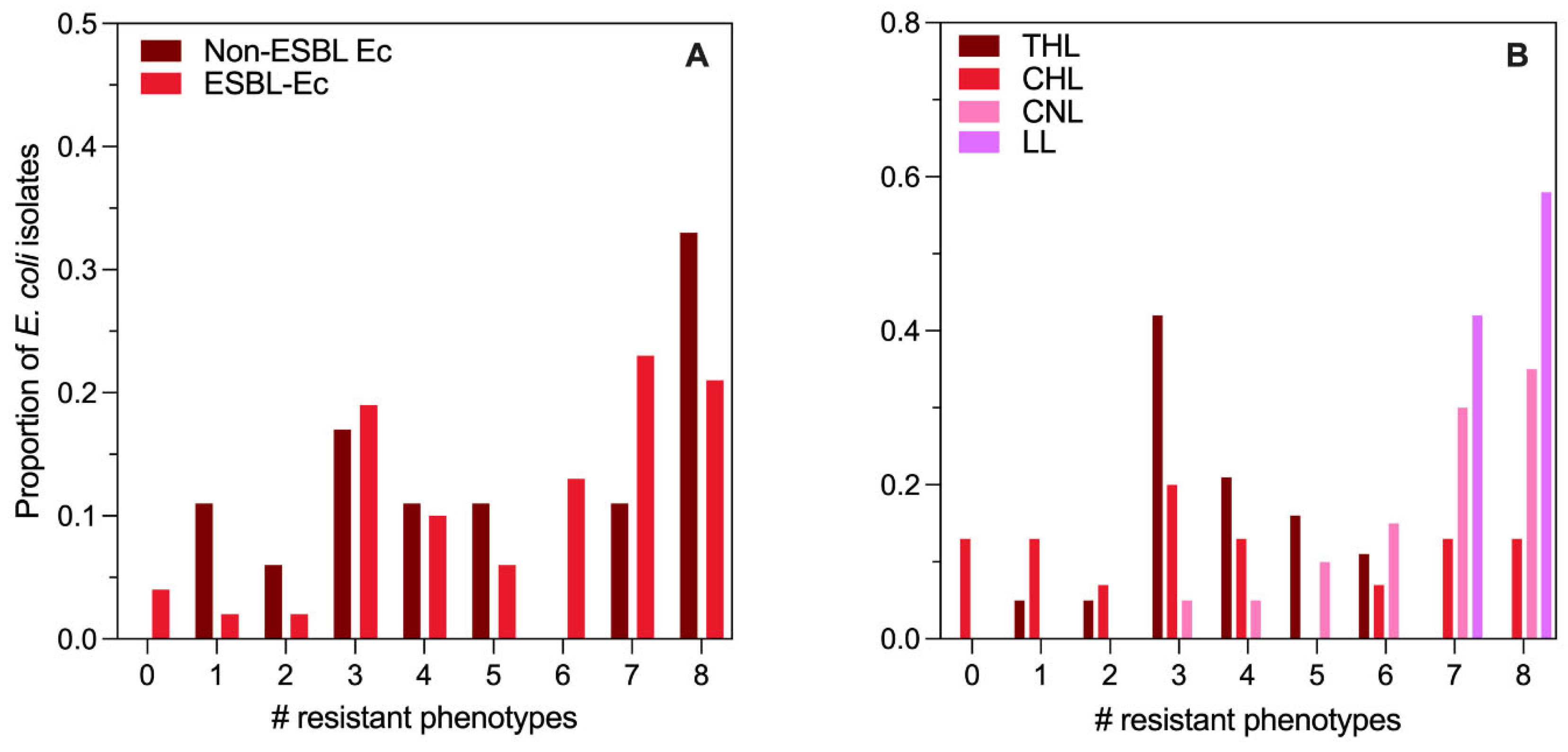

Number of antibiotic resistance phenotypes was driven by lake rather than ESBL versus non-ESBL status

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens public health worldwide. As antibiotic usage has become essentially ubiquitous among humans and animals, the selective pressure of such compounds has enriched populations of bacteria capable of resisting their effects (Munita and Arias, 2016). Since antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARBs) are less susceptible to treatment, infections with ARBs are causing greater morbidity, mortality, and economic burdens associated with infectious disease (WHO, 2023). In 2019 alone, there were an estimated 1.3 million deaths directly attributable to ARBs and an additional 3.7 million deaths associated with complications from ARBs (Murray et al., 2022). Simultaneously, the antibiotic development pipeline has become insufficient to safeguard human health (IFPMA, 2024). Mitigating threat posed by AMR is complicated by the ability of bacteria to exchange genetic information both vertically and horizontally. Bacterial habitats characterized by the intersection of selective pressure and horizontal exchange of genetic material are key venues to mitigate the spread of AMR. Such habitats include humans, animals, and the environment. The interlinked nature of AMR dissemination is encapsulated in the “One Health” paradigm that has been proposed as a framework for managing the multi-sectoral challenge posed by AMR (WHO, 2023). Owing to its complexity and the increasing burden, which is disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared AMR to be among the top ten global public health threats of the century (Nadimpalli et al., 2020; WHO, 2023).

Among the many ARBs in existence, the WHO has defined a group of critical pathogens that pose a significant threat to public health due to limited treatment options, high disease burden, and increasing prevalence (WHO, 2024). This critical group includes members of the order Enterobacterales (E) that are carbapenem-resistant (CREs) and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GCRE). Beta-lactam antibiotics, such as carbapenems and cephalosporins, are crucial for the treatment of gram-negative bacterial infections (Doi et al., 2017). Within the order Enterobacterales, Escherichia coli that produce beta-lactamase enzymes, especially extended-spectrum enzymes that confer resistance to a broad range of beta-lactam antibiotics, are leading pathogens for AMR-associated deaths and disease (Bush and Bradford, 2020; Murray et al., 2022). Community and hospital-acquired infections with extended-spectrum beta-lactamse-producing E. coli (ESBL-Ec) have increased rapidly in most WHO regions with an estimated increase of 5% each year (Castanheira et al., 2021; Doi et al., 2017). Pooled prevalence estimates suggest the fecal carriage rate of ESBL-Ec among healthy individuals increased from 2.6% in the early 2000s to 21.1% by 2018, with the highest prevalences observed in Southeast Asia (27%) and the lowest in Europe (6%) (Bezabih et al., 2021; Bush and Bradford, 2020). While disentangling the precise epidemiology of ESBL-Ec spread is complicated by the existence of 3,000 different genes encoding beta-lactamase enzymes, the global increase was primarily driven by the dissemination of CTX-M genes (Castanheira et al., 2021).

The environment is an important venue for the dissemination of AMR among bacteria and exposure to ARBs. Risk assessments suggest environmental sources of AMR pose a higher risk in LMICs, with the highest risk in Southeast Asia (Chereau et al., 2017). India is among the top-ranked countries in the world for antibiotic consumption by humans and animals and for the manufacture of antibiotic compounds (Das et al., 2023; Taneja and Sharma, 2019). Many of these domestic, agricultural, and industrial waste streams enter the aquatic environment with minimal treatment. Antibiotic compounds and ARBs have been detected in aquatic environments throughout India, and AMR rates among bacteria in India are among the highest observed (Das et al., 2023; Taneja and Sharma, 2019). ESBL-producing bacteria are no exception. A meta-analysis suggested that the prevalence of ESBL-Ec among clinical isolates in South Asia was 33%, and more than 50% of clinical E. coli isolates collected from patients in India have been classified as ESBL-producing (Doi et al., 2017; Islam et al., 2021). Animals fare no better, with average ESBL-Ec carriage rates of 9% among livestock across India (Kuralayanapalya et al., 2019). ESBL-producing bacteria, including E. coli, are also prevalent in wastewaters and surface waters throughout India (Taneja and Sharma, 2019). ESBL-Ec have been documented in many significant rivers including the Yamuna (Gehlot and Hariprasad, 2024; Singh et al., 2021), Ganga (Johnson et al., 2020), Kshipra (Diwan et al., 2018), and in lakes in both northern and southern India (Sultan et al., 2022; Vaiyapuri et al., 2021).

Given the multi-sectoral and global nature of AMR dissemination, integrated, harmonized, and scalable surveillance methods are critical to best inform One Health mitigation efforts (Calarco et al., 2024; Pruden et al., 2021). To this end, the WHO and the Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance on AMR developed the Tricycle Protocol to monitor ESBL-Ec as a simple, feasible, and harmonized proxy indicator of AMR trends across the human, animal, and environmental sectors (WHO, 2021). The environmental component of the Tricycle Protocol consists of measuring ESBL-Ec in hotspot sources and receiving waters upstream and downstream of major settlements, with the goal being to monitor the proportion of total E. coli that are ESBL-Ec over time (WHO, 2021). To date, 19 countries have begun implementing the Tricycle Protocol and pilot data has been published from three – Ghana, Indonesia, and Madagascar (Ruppé, 2023).

In the current study, we implemented two versions of the Tricycle Protocol to examine the prevalence, abundance, and resistance phenotypes of ESBL-Ec in four freshwater lakes near Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. Importantly, the four lakes in the study are characterized by a gradient of anthropogenic impacts. This design is consistent with a previous AMR workshop that recommended pristine areas, areas in proximity to informal slums, and areas of high impact, all of which are included in the current study, as high priority opportunities (Sano et al., 2020). In addition to the examination of ESBL-Ec, we have also measured antibiotic residues in the same lakes. Our results suggest the Tricycle Protocol accurately discerns differences in the environmental AMR situation across the anthropogenic activity gradient. However, there are important limitations and caveats that must be acknowledged when interpreting the data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Sites

Grab samples were collected from four freshwater lakes located in the vicinity of Ahmedabad and within the Mehsana district in Gujarat, India (

Figure S1). The first site, Thol Lake (THL), is located about 30 km northwest of Ahmedabad (23°22.50′N 72°37.50′E) and is a migratory bird wildlife refuge located on the Central Asian Flyway. THL has been preserved as a Ramsar Site since 1988 and is known to host more than 320 bird species, including 110 water bird species (

https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/2458). In 2013, the Union Ministry of Forests and Environment declared the area surrounding THL to be an Eco-Sensitive Zone. THL is well-kept and strictly maintained, with visitors only coming to observe the bird life (

Figure S2 A). The second site, Chharodi Lake (CHL), is a peri-urban waterbody located adjacent to National Highway 147E, approximately 16 km north of Ahmedabad (23.1227° N, 72.5408° E). CHL is adjacent to residential developments and serves as a park and recreation site with walking and pedal boating available. The area surrounding CHL has been subject to increasing urbanization and development, and several pipe outfalls are within the periphery of the lake (

Figure S2 B). The third sampling site, Chandola Lake (CNL), is a prominent waterbody located in a densely populated area approximately 5 km south of Ahmedabad (22.9879° N, 72.5870° E). The lake's size fluctuates seasonally owing to large inputs from monsoon rains. The lake is surrounded by informal human settlements, and the shoreline is a site for open defecation and laundering clothes (

Figure S2 C). Livestock such as buffalo also use the lake for drinking and soaking. The fourth and final sampling site, Lambha Lake (LL), is located 13 km south of Ahmedabad (22.9363° N, 72.5743° E). LL has historically been heavily contaminated with the inflowing canals being filled with garbage. LL also receives effluent discharges from nearby industries and receives effluent from a 5 million liter per day sewage treatment plant (STP) (

Figure S2 D). We hypothesized that the level of anthropogenic impact across the four lakes would be reflected by differences in (1) the prevalence and abundance of ESBL-Ec, (2) resistance phenotypes of

E. coli and ESBL-Ec isolated from their waters, and (3) the presence and concentration of antibiotic compounds.

2.2. Sample Collection

The lakes were sampled over 8 events between 3 March and 28 April 2023, with 4 to 16 days between sampling events. During each sampling, 800 mL of water was collected from 10 to 12 inches under the lake surface using a sterile bottle at three sites within each lake (

Table S1), yielding a total of 24 grab samples collected from each lake. Each grab sample was stored in an ice box with ice for transport to the laboratory. Upon arrival at the lab, samples were stored at 4 °C, and tested within 24 h as detailed in the following sections.

2.3. Generic E. coli by Membrane Filtration

Prior to membrane filtration, each sample was mixed by hand shaking, and then large, suspended solids were allowed to settle briefly. Sample supernatant was then collected, and a dilution series was prepared using sterile distilled water as a diluent. The diluted samples were vacuum filtered through a sterile Whatman 0.45 µm mixed cellulose ester membrane filter (ME25, Global Life Sciences Solutions, Marlborough, MA, USA) using a sterile filter funnel and column. After filtering the membrane was aseptically rolled onto a 50 mm petri dish containing Chromocult Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide (TBX, ISO 16649) Agar (92435, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for the selective enumeration of E. coli (blue-green colonies) from water without further confirmation per the manufacturer’s instructions. Each TBX agar plate was incubated at 44 °C for 24 h, and E. coli colonies were enumerated by counting blue-green colonies. Based on the dilution yielding a countable plate, the E. coli density was calculated and reported in colony-forming units (CFU) per 100 mL of lake water.

2.4. ESBL-Ec Screening by Membrane Filtration

The Tricycle protocol describes the use of membrane filtration and culture on TBX agar supplemented with 4 µg/mL cefotaxime to screen environmental samples for presumptive ESBL-Ec based on previous optimization experiments with MacConkey agar and ESBL-Ec control strains (Banu et al., 2021; Jacob et al., 2020). In the current study, the Tricycle protocol was modified by using ceftriaxone (CRO), another third-generation cephalosporin, to screen for presumptive ESBL-Ec isolates from the lake water samples. Although CRO is not used in the Tricycle Protocol, as per the M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing published by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), CTX and CRO are “equivalent agents'' for testing the susceptibility of Enterobacteriaceae such as

E. coli (CLSI, 2023). CRO screening with concentrations ≥ 2 µg/mL has been suggested as a reasonable proxy for ESBL-Ec phenotype in clinical microbiology (Curello and MacDougall, 2014; Villegas et al., 2021). CRO has also been used for ESBL-Ec screening from environmental waters in various formats (Pek et al., 2023). Serial dilutions of lake water samples were membrane filtered as detailed in

Section 2.3 and aseptically transferred to 50 mm diameter Petri dishes containing TBX agar supplemented with a 5 mg/mL CRO stock solution (C2226, Ceftriaxone Disodium salt, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Tokyo, Japan) to achieve a final CRO concentration of 4 µg/mL in the agar matrix. Each TBX-CRO agar plate was incubated, and

E. coli colonies were enumerated per the manufacturer’s recommendation. These

E. coli colonies are referred to as “CRO-resistant” and are interpreted to be presumptive ESBL-Ec. The resulting CRO-resistant colonies were subjected to confirmatory ESBL and antibiotic susceptibility testing via disk diffusion, as detailed in subsequent sections.

2.5. ESBL-Ec Screening by Quanti-Tray

Previous studies have used Quanti-Trays combined with CTX to screen for presumptive ESBL-Ec in wastewater and with CRO for various types of water in Malawian markets (Galvin et al., 2010; Masoamphambe et al., 2021). A recent study found that IDEXX Quanti-Tray with Colilert media and CTX produced

E. coli concentrations statistically similar to MacConkey agar and TBX for surface water samples amended with an ESBL-Ec control strain (Hornsby et al., 2023). In the current study, presumptive ESBL-Ec were screened from lake water samples using a Quanti-Tray/2000 format in parallel with the previously described membrane filtration method. A serial dilution of each lake water sample was prepared as described in

Section 2.3 to a total volume of 100 mL. Colilert-18 media (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA) was added to each 100 mL sample solution. Each bottle was then immediately amended with 80 µL of a 5 mg/mL CRO stock to achieve a final CRO concentration of 4 µg/mL. The solution was poured into a Quanti-Tray/2000 MPN tray and sealed using a Quanti-Tray Sealer (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA). The Quanti-Trays were incubated at 35 °C for 18 h, and then the

E. coli MPN results were interpreted using UV light per the manufacturer’s recommendations and the IDEXX MPN Generator Software (v 1.4.4, IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA). After adjustment for dilution, the resulting MPN was interpreted as the MPN of CRO-resistant and, therefore, presumptive ESBL-Ec per 100 mL of lake water. Each batch of samples processed included qualitative positive controls in the form of sterile water seeded with an overnight broth culture of an archived ESBL-Ec isolate and negative controls in the form of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Results for the relevant sample batch were considered valid for each method only if the controls yielded the expected result by that method.

2.6. Presumptive ESBL-Ec Phenotype Confirmation by Combination Disk Diffusion

Presumptive ESBL-Ec isolates were confirmed to be ESBL-producing or non-ESBL-producing using the combination disk diffusion test (CDT) as described in the Tricycle Protocol with the results interpreted per Table 3A “Tests for Extended-Spectrum

β-Lactamases in

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Klebsiella oxytoca,

Escherichia coli, and

Proteus mirabilis” of the M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (CLSI, 2023; WHO, 2021). For each sample yielding CRO-resistant

E. coli via membrane filtration (

Section 2.4), one randomly selected colony per membrane was streaked onto TBX agar and incubated at 44 °C for 24 h to produce an isolate. The resulting isolate was added into a 2 mL sterile saline solution (8.5 g/L NaCl) and briefly vortexed to achieve a 0.5 McFarland Standard (1.5 x 10

8 CFU/mL). The isolate suspension was then streaked onto a 100 mm Petri dish containing Mueller Hinton (MH) agar (225250, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) as described in the Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol (Hudzicki, 2009). After streaking, an 8-place BD BBL Sensi-Disc Dispenser (260660, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to apply 30 µg ceftazidime (CAZ, BD231632), 30/10 µg ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (CAZ/CLA, BD231754), 30 µg cefotaxime (CTX, BD231606), and 30/10 µg cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (CTX/CLA, BD231751) Sensi-Discs (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to the inoculated dish. The MH plate was incubated at 35 °C, and after 18 h, the diameter of the zone of inhibition around each disk was measured to the nearest millimeter. Isolates yielding an increase of 5 mm or more between the diameters of CAZ alone versus CAZ/CLA or CTX alone versus CTX/CLA were confirmed ESBL-Ec isolates (CLSI, 2023; WHO, 2021).

2.7. E. coli Isolate Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST)

In parallel with ESBL-Ec confirmatory testing, isolates were also tested for susceptibility to 8 different antibiotic compounds by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion (Hudzicki, 2009). For lake water samples yielding CRO-resistant E. coli during membrane filtration, isolates were produced as described in the preceding section. When a lake water sample produced no CRO-resistant E. coli, a generic E. coli colony from membrane filtration was used to produce an isolate for susceptibility testing following the same procedure described in the preceding section. After streaking the isolate onto a 100 mm MH plate, the 8-place BD BBL Sensi-Disc Dispenser was used to apply a 10 µg ampicillin (AM-10, BD231264), 15 µg azithromycin (AZM, BD231682), 5 µg ciprofloxacin (CIP, BD231658), 30 µg ceftriaxone (CRO, BD231634), 10 µg meropenem (MEM, BD231704), 23.75/1.25 µg sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim (SXT, BD231539), 10 µg streptomycin (S-10, BD231328), and 30 µg tetracycline (TE, BD230998) Sensi-Disc (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to each inoculated MH agar plate. The MH plate was incubated at 35 °C, and after 18 h, the diameter of the zone of inhibition around each disk was measured to the nearest millimeter. Each isolate was classified as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on the zone diameters listed in M100 Table 2A, “Zone Diameter and MIC Breakpoints for Enterobacterales” (CLSI, 2023).

2.8. LC-MS/MS Detection of Antibiotic Compounds

The QuEChERS method was used to extract antibiotics from grab samples (100 mL) collected from each lake. A 10 mL subsample was filtered using a Whatman 0.45 µm pore size filter paper (Whatman) and the filtrate was vortexed for 2 min with 10 mL of acetonitrile using a vortex mixer (LabNet Vortex Mixer VX-200). 2 g of NaCl and 4 g of anhydrous magnesium sulfate were added to the sample and further vortexed for 2 min followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 min using a high-speed centrifuge (Sorvall Legend X1R Benchtop, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, 1 mL from the upper acetonitrile layer was transferred into an LC vial for LC-MS/MS analysis. Ultrafast liquid chromatography with a tandem mass spectrophotometer (Shimadzu LC 30 A, LCMS-8040) was used to analyze antibiotic compounds in the prepared samples. Chromatographic separation was performed with a C18 column (4.6 x150 mm x 5µm). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q water (A) and methanol (B). The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.5 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. The injection volume was 10μL. The chromatographic method employed a binary gradient system with varying concentrations of mobile phase B at 0%, 0%, 40%, 60%, 90%, 90%, 0%, and 0% at a time interval of 0.01, 2.0, 3.0, 8.0, 10.0, 14.0, 14.50, and 20.0 minutes, respectively. The analysis was done in ESI (+) mode with an ionization voltage of +4.5 kV. Nitrogen was the nebulizing and drying gas with a flow rate of 2.8 L/min and 10 L/min, respectively. The dynamic link (DL) temperature was 250 °C, and the heater block temperature was 400 °C. The analysis was done in MRM mode with a total dwell time of 20 minutes. The mass optimization parameters and method validation results are presented in

Table S1 and Table S2.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Except where noted otherwise, figures and statistical analyses were prepared in GraphPad Prism 10 v. 10.1.0 (264) (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Quantitative comparisons (E. coli count, CRO-resistant E. coli count, CRO-resistant E. coli proportion, ESBL-Ec prevalence, antibiotic compound resistance prevalence, number of phenotypic resistance traits per isolate) between multiple groups (THL, CHL, CNL, LL) were made by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc for multiple comparisons (Dunn, 1964; Kruskal and Wallis, 1952). Quantitative agreement between log10-transformed TBX-CRO and Colilert-18-CRO enumerations of CRO-resistant E. coli was assessed by means of Spearman correlation, linear regression, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC, performed in SPSS v. 26.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) (Han, 2020; Spearman, 1904). Qualitative agreement between ESBL screening methods (TBX-CRO CFU vs Colilert-18-CRO MPN) and between screening methods and ESBL confirmation by CDT was assessed by means of the Kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960). Quantitative comparisons between CRO-resistant E. coli counts by membrane filtration versus Quanti-Tray/2000 (stratified by lake) were made using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Wilcoxon, 1945). Phenotypic resistance profiles for individual antibiotic compounds and the number of phenotypic resistance traits between confirmed ESBL-Ec and non-ESBL-Ec isolates were compared via the Mann-Whitney U test (Mann and Whitney, 1947). The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was calculated for each isolate by dividing the number of antibiotics to which an isolate was resistant by the number of antibiotic compounds tested (8), and comparisons between groups (lakes and ESBL versus non) were made by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc for multiple comparisons (Krumperman, 1983).

3. Results

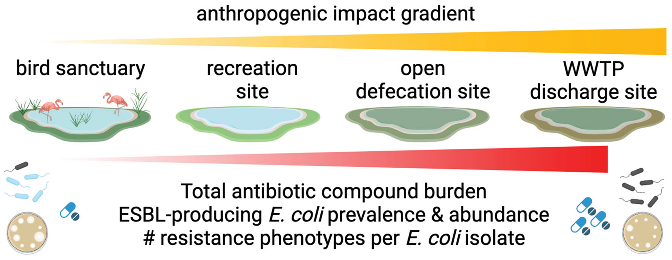

3.1. Generic E. coli Measurements by Lake

Membrane filtration and culture on TBX agar yielded valid results for all 24 grab samples collected from each lake except LL. In the case of LL, beginning with the 13th sampling event, all subsequent samples were non-detect for

E. coli. Further investigation revealed that from the 13th sampling event, the lake was being actively treated with an algaecide, so the non-detection results for the remaining 12 LL grab samples were removed from the dataset for analysis. The dilutions yielded countable results for 71 to 100% of samples across all four lakes (

Table S4). As shown in

Figure 1A, average

E. coli counts (CFU/100 mL ± standard deviation) were 131 ± 179 in THL, 245 ± 419 in CHL, 10,800 ± 10,200 in LL, and 24,400 ± 40,700 in CNL. A pairwise comparison of

E. coli counts in each lake indicated no difference between THL and CHL (

p > 0.9999) and CNL and LL (

p > 0.9999). However, counts were significantly different between the individual members of each pair and the two lakes in the other pair (

p < 0.0001). Although

E. coli was prevalent among grab samples from all lakes, the

E. coli count data suggests CNL and LL have a distinctly higher

E. coli abundance than THL and CHL.

3.2. CRO-Resistant E. coli Measurements by Lake

CRO-resistant

E. coli were enumerated using two methods in parallel – membrane filtration followed by culture on TBX agar amended with CRO (TBX-CRO) and Colilert-18 Quanti-Tray 2000 amended with CRO (CQT-CRO). By TBX-CRO, 17% (CHL) to 100% (LL) of grab samples contained CRO-resistant

E. coli (

Table S5). Similar to generic

E. coli counts, average CRO-resistant

E. coli counts (CFU/100 mL) by TBX-CRO were lowest in THL (12.0 ± 6.53), followed by CHL (120 ± 133), LL (2,010 ± 939), and CNL (7,470 ± 15,500) as shown in

Figure 1B. However, unlike generic

E. coli, CRO-resistant

E. coli counts in each lake by TBX-CRO displayed a gradient in abundance, with THL yielding significantly lower counts than CNL and LL (

p = 0.0005 and 0.0008, respectively), while CHL counts were not significantly different from LL (

p = 0.1243), CNL (

p = 0.1261), or THL (

p > 0.9999). This could be attributable to the limited number of countable results (n = 4) for CRO-resistant

E. coli by TBX-CRO in CHL. Just as for generic

E. coli, CNL, and LL yielded comparable CRO-resistant

E. coli counts by TBX-CRO (

p > 0.9999). As shown in

Figure 1C, by CQT-CRO,

E. coli abundance trends between lakes were, in general, similar, with the average count lowest in THL, followed by CHL, then LL, and lastly CNL. However, for the lakes with lower CRO-resistant

E. coli abundance (THL and CHL), the proportion of samples containing CRO-resistant

E. coli doubled by the CQT-CRO method compared to the TBX-CRO method (

Table S5). With the increased number of countable results, the abundance of CRO-resistant

E. coli by CQT-CRO in each lake clustered similarly to the generic

E. coli counts – THL vs CHL (

p > 0.9999) and CNL/LL (

p > 0.9999) with all other pairwise comparisons yielding significant differences (

p < 0.05).

The proportion of CRO-resistant

E. coli in each lake was estimated using generic

E. coli counts from TBX agar (denominator), and CRO-resistant

E. coli counts from TBX-CRO (numerator) (

Figure 1D). THL and CHL yielded the lowest proportions of CRO-resistant

E. coli with average percentages of 3 ± 7 and 1 ± 5, respectively (

Table S6). CRO-resistant

E. coli proportions in CNL and LL were much greater, with average percentages of 21 ± 23 and 29 ± 18, respectively. The maximum proportion of CRO-resistant

E. coli observed in any single sample was 98% for a grab sample collected from CNL. The proportion of CRO-resistant

E. coli in grab samples stratified by lake exhibited similar trends to generic

E. coli. Proportions were comparable in THL and CHL (

p > 0.9999) and CNL and LL (

p > 0.9999) but were significantly different for all other pairwise comparisons (

p < 0.05).

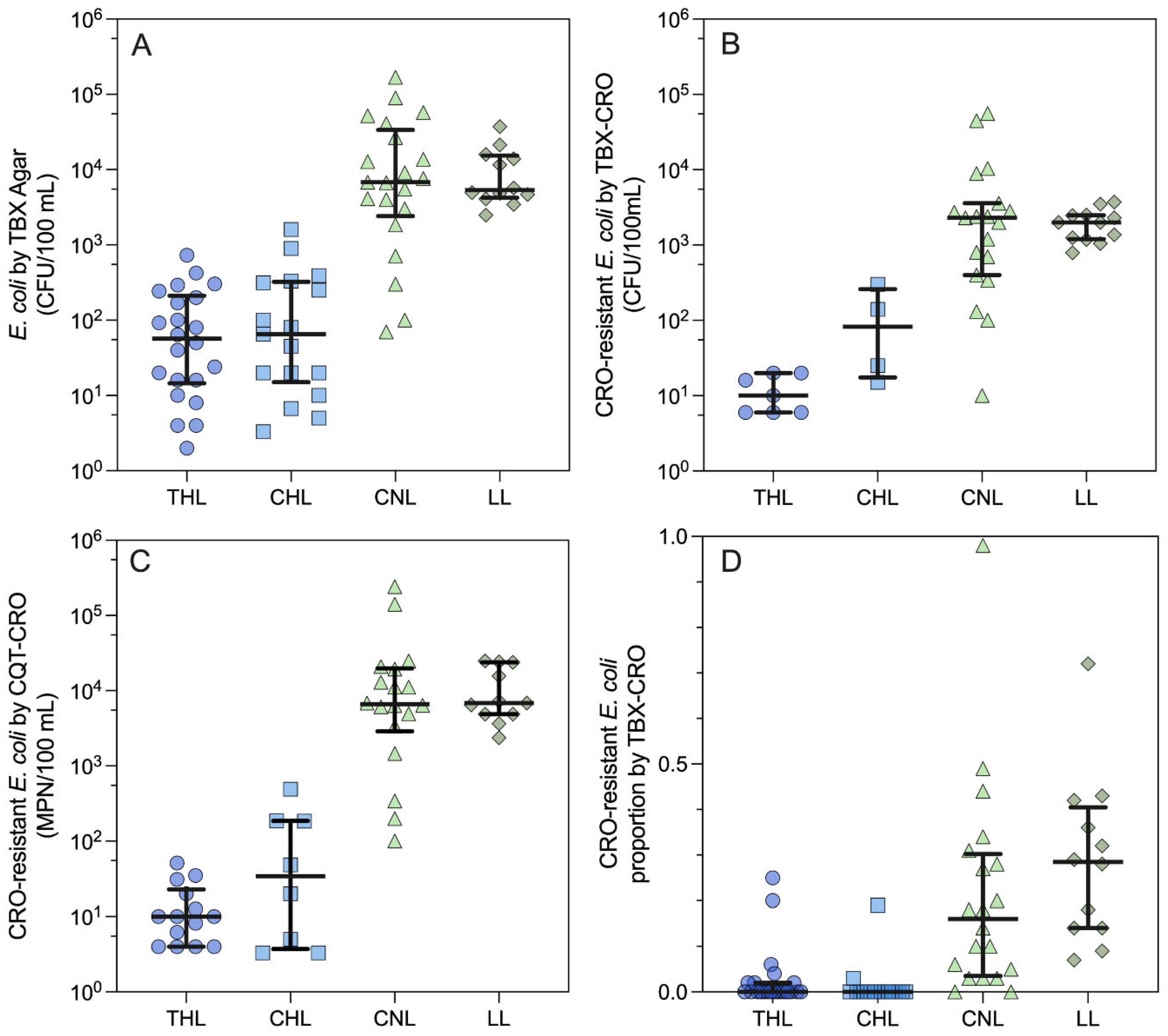

3.3. CRO-Resistant E. coli Measurements Comparison by Method

The two methods used to measure CRO-resistant

E. coli (TBX-CRO and CQ-CRO) were compared for qualitative and quantitative agreement among the 84 samples that yielded valid results for both. Among these, 67 pairs were concordant, and 17 were discordant, yielding a Kappa value of 0.603 (95% CI: 0.445 - 0.761). This result suggests moderate (0.41 to 0.60) agreement between the two for assessing the presence of CRO-resistant

E. coli in individual grab samples. The Spearman correlation coefficient between log

10-transformed CRO-resistant

E. coli counts by each method indicates a strong correlation (r = 0.7513,

p < 0.0001). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.849 (95% CI: 0.211 - 0.950) and suggests good quantitative agreement between the two methods. As shown in

Figure 2, paired log

10-transformed counts were linearly related (y = 1.17x + 0.192, r

2 = 0.785). When stratified by lake (

Figure S3), CRO-resistant

E. coli counts were similar between the two methods for THL (

p = 0.4062) and CHL (

p = 0.7500), where CRO-resistant

E. coli abundance was lower. Whereas for CNL and LL, where CRO-resistant

E. coli abundance was higher, the CQT-CRO method yielded greater counts of CRO-resistant

E. coli (

p = 0.0001,

p = 0.0020, respectively) than the TBX-CRO method. Although, this observation could be an artifact of the low number of samples yielding CRO-resistant

E. coli in THL (n = 6) and CHL (n = 4) compared to CNL (n = 18) and LL (n = 12).

3.4. CRO-Based Screening for ESBL-Producing E. coli

In the current study, E. coli resistant to CRO on TBX agar were interpreted as putative ESBL-Ec and were subjected to confirmatory testing via the combined disk test (CDT). Neither ESBL-Ec screening method (i.e., the presence of CRO-resistant E. coli in the sample assessed by TBX-CRO or CQT-CRO) demonstrated agreement with ESBL-Ec phenotype presence confirmed by CDT. The TBX-CRO screen yielded 33 concordant pairs and 33 discordant pairs (K = -0.090) with a sensitivity of 56.3% (95% CI: 41.2 - 70.5) and specificity of 33.3% (95% CI: 13.3 - 59.0) for phenotypic ESBL-Ec. The CQT-CRO screening did not fare better, with 41 concordant pairs and 25 discordant pairs (K = -0.007), a sensitivity of 77.1% (95% CI: 62.7 - 88.0), and a specificity of 22.2% (95% CI: 6.4 - 47.6). These results suggest that neither CRO-based screening format was a reliable predictor of ESBL-Ec phenotype in the samples collected from the four lakes during the study period.

3.5. Antibiotic Compound Resistance among ESBL- and Non-ESBL Ec

A total of 66

E. coli isolates were subjected to ESBL confirmatory testing by CDT and AST testing against 8 antibiotic compounds. Among these isolates, 48 (73%) were confirmed as ESBL-Ec, and 18 (27%) were non-ESBL-Ec. There was no difference (

p > 0.05) in the AST categorical distribution (susceptible, intermediate, resistant) between ESBL versus non-ESBL

E. coli isolates for any of the 8 compounds tested (

Figure S4,

Table S8). Further, as shown in

Figure 3A, the distribution of the number of antibiotic compounds to which an individual isolate was resistant nor the MAR index varied for ESBL versus non-ESBL

E. coli (

p = 0.9451). Nonetheless, the

E. coli isolates demonstrated extensive resistance, with only 11% of isolates susceptible to 2 or more compounds. Among the 66 isolates, 71% were resistant to 4 or more antibiotic compounds, and 24% were resistant to all 8 compounds tested.

When considering results stratified by lake, there was no difference in the confirmed ESBL-Ec proportion (

p = 0.4608,

Table S8). However, the number of antibiotic compounds to which an individual isolate was resistant (MAR index) varied significantly by lake (

p < 0.0001,

Figure 3B), with only CHL/THL and CNL/LL exhibiting a similar MAR index (

p > 0.9999) in pairwise comparisons. For THL and CHL, only 48% and 46% of isolates exhibited resistance to 4 or more compounds, respectively. Meanwhile, for CNL and LL, 95% and 100% of isolates, respectively, were resistant to 4 or more compounds. Resistance phenotypes were especially prevalent in LL, with 100% of isolates demonstrating resistance to 7 or 8 compounds.

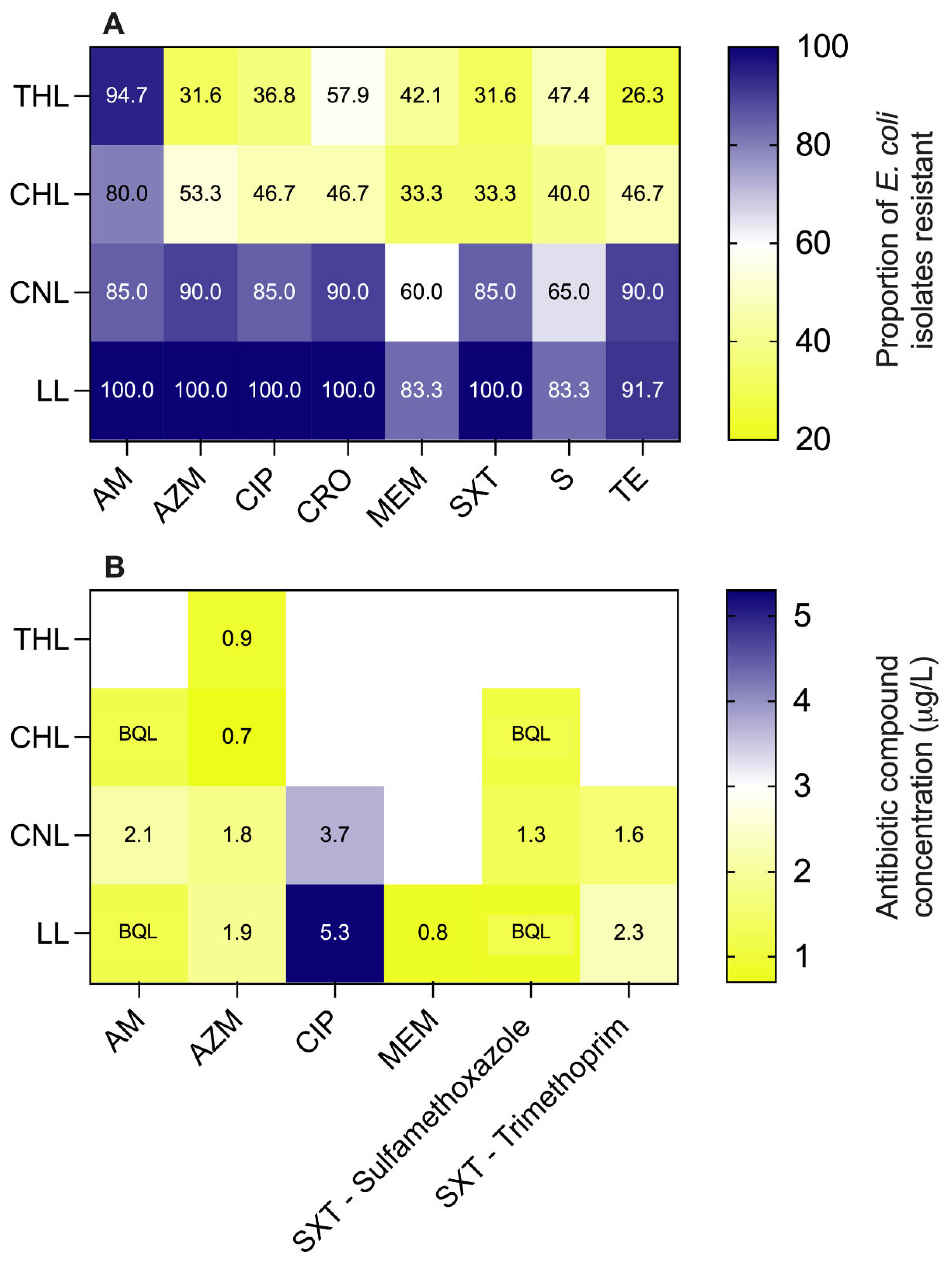

A heatmap of the proportion of

E. coli isolates demonstrating resistance to various antibiotic compounds for each individual lake is shown in

Figure 4. Resistance prevalence was not significantly different between the four lakes for ampicillin (AM,

p = 0.062) and streptomycin (S,

p = 0.0886). Just as for generic

E. coli counts and CRO-resistant

E. coli counts, the lakes separated into two distinct clusters with resistance prevalence among isolates from THL and CHL being comparable for all compounds (

p ≥ 0.3953) and from CNL and LL being comparable for all compounds (

p > 0.9999). When comparing THL to CNL and CHL, statistically significant differences (

p < 0.05) in resistance prevalence were observed for azithromycin (AZM), ciprofloxacin (CIP), sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim (SXT), and tetracycline (TE). For CHL and CNL, the prevalence of CRO and SXT resistance were significantly different. Lastly, for CHL and LL, the prevalence of CIP, CRO, meropenem (MEM), and SXT resistances were significantly different. All other pairwise comparisons between compounds and lakes yielded statistically insignificant results (

p > 0.05).

3.6. LC-MS/MS Detection of Antibiotic Compounds

Only a single antibiotic compound, Azithromycin (AZM), was detected in all four lakes at concentrations ranging from 0.7 µg/L (CHL) to 1.9 µg/L (LL). Ampicillin and Sulfamethoxazole were detected in every lake except THL, although the detections were below the quantification limit (BQL) in CHL and LL. Sulfamethoxazole concentrations were also highest in CNL (1.3 µg/L), with CHL and LL both yielding BQL results. Trimethoprim was only detected in CNL and LL at concentrations of 1.6 and 2.3 µg/L, respectively. Ciprofloxacin (CIP) was also only detected in CNL and LL at 3.7 and 5.3 µg/L, respectively, the highest concentrations observed for any compound. Meropenem was detected only in LL at 0.8 µg/L. The cumulative antibiotic burden in LL (12.3 µg/L) was higher than that in CNL (10.5 µg/L), potentially due to the direct discharge of effluent from a nearby STP. CNL, which is a known open defection site and surrounded by scattered garbage dumps, recorded the second-highest cumulative antibiotic load. CHL exhibited a total antibiotic concentration of 0.7 µg/L, while THL solely detected Azithromycin at BQL levels. The analytical results for all antibiotic compounds in each lake are summarized in a heat map shown in

Figure 4B.

4. Discussion

4.1. ESBL-Ec and Anthropogenic Impact

Our study leveraged a modified version of the WHO Tricycle protocol to assess AMR via ESBL-Ec across four lakes subject to varying levels of human activity. The lakes include one that is a wildlife refuge for migratory birds (THL), one that is a recreational site on the urban periphery (CHL), one that is adjacent to an informal settlement, and a site for open defecation and animal soaking (CNL), and finally, one that receives effluent from an STP (LL). Generic E. coli counts from the four lakes reflected the impact gradient we observed during our preliminary sanitary inspection, with two distinct clusters emerging – THL and CHL, low impact, versus CNL and LL, high impact. This same distinction was also reflected in the putative ESBL-Ec (i.e., CRO-resistant) measurements with significantly lower prevalence in grab samples from THL/CHL (17 to 29%) compared to CNL/LL (79% to 100%) and significantly lower abundance in THL/CHL (mean counts 12 and 120 CFU/100 mL, respectively) versus CNL/LL (mean counts 7,470 and 2,010 CFU/100 mL, respectively). The mean proportion of E. coli resistant to CRO ranged from 1 to 3% in THL/CHL, while in CNL/LL, it ranged from 21 to 29%. The number of resistance phenotypes observed in E. coli isolates also separated into the same two distinct groups, with the MAR index being significantly lower among isolates from THL and CHL compared to CNL and LL.

The ESBL-Ec measurements from the bird sanctuary and recreational lakes are consistent with measurements made using versions of the WHO Tricycle Protocol to test surface waters in the United States. For example, in North Carolina, surface water samples were found to have ESBL-Ec positivity rates of 8.5%, and proportions of ESBL-Ec to generic E. coli were less than 2% (Appling et al., 2023; Hornsby et al., 2023). Conversely, for the two highly impacted lakes, the ESBL-Ec data are comparable to data produced via the Tricycle Protocol in other LMICs. In Ghana, for example, 98% of water samples from two rivers contained ESBL-Ec at concentrations between 1,000 and 10,000 CFU per 100 mL (Banu et al., 2021). Similarly, pilot testing of the Tricycle Protocol in Indonesia found that 100% of water samples contained ESBL-Ec with ESBL-EC to generic E. coli proportions ranging from 4.2 to 30.2% of total E. coli (Puspandari et al., 2021). Concerning AMR, as reflected by ESBL-Ec measurements made via the Tricycle Protocol, the lakes in the current study stratify into those less impacted by anthropogenic inputs, a bird sanctuary and recreational site, and those more affected by human activities, including open defecation, animal soaking and grazing, and sewage treatment plant effluent. This is consistent with molecular-based characterizations of lotic ecosystems where ESBL gene prevalence and diversity were distinctly different between polluted and unpolluted settings (Tacão et al., 2012).

Notably, even the “pristine” lake within the bird sanctuary, which is strictly maintained as an Eco-Sensitive Zone, was not free of ESBL-Ec. We hypothesize that in this setting, migratory birds are the likely source. Among migratory birds in Bangladesh, the prevalence of ESBL-Ec fecal carriage was 38% (Islam et al., 2022). In Saudi Arabia, aquatic-associated migratory birds, such as the type that would be expected at THL, had a higher MAR index among bacteria isolated from their feces compared to other birds (Elsohaby et al., 2021). Elsewhere, genetic investigations of a specific beta-lactamase type (blaTEM) suggested extensive linkages between birds and their environments, including soil and water, and the presence of clinically relevant ESBL-Ec sequence types in bird feces (Ahlstrom et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2022). Our observations suggest that the baseline for “pristine” environments in India, and possibly elsewhere, is possibly not the absence of ESBL-Ec and further substantiates the diffuse and complex pathways for AMR dissemination, even in the absence of direct human activity within the relevant ecosystem.

The prevalence and concentration of antibiotic compounds in the four lakes also followed the hypothesized trend along the anthropogenic impact gradient. The lakes in the bird sanctuary (THL) and recreational site (CHL) exhibited the lowest cumulative antibiotic compound concentrations (0.9 µg/L and 0.7 µg/L, respectively). Birds and their feces have previously been implicated in depositing antibiotic residuals in aquatic ecosystems (Mejías et al., 2022). The highly impacted lakes (CNL and LL) were characterized by much greater cumulative antibiotic concentrations (10.5 and 12.3 µg/L), with the majority of compounds detected in the water column, including a carbapenem in the case of LL. Although the cumulative antibiotic compound burden mirrored the trends in CRO-resistant and MDR E. coli abundance and prevalence, there was not a one-to-one relationship between antibiotic compounds present in the lakes and resistance phenotypes observed among E. coli isolates. For example, some E. coli isolates from THL and CHL demonstrated multi-drug resistance and resistance against compounds not detected in the lakes. Given the frequent co-location of ARGs on plasmids, the selective pressure exerted by one antibiotic could enrich bacteria resistant to others. Additionally, the lakes themselves may not be the venue for selection, which could occur upstream during sewage treatment or in the gut of humans or livestock. Even if the lakes are the venue, the relationship between aqueous antibiotic concentration and environmental selective pressure is poorly characterized (Berglund, 2015). It is known that concentrations well below clinically relevant minimum inhibitory concentrations can select for resistant bacteria in the environment (Lübbert et al., 2017). Estimates indicate antibiotic concentrations ranging from 8 ng/L to 64 μg/L, well below ecotoxicology thresholds, have the potential to exert selective pressure in the environment (Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson, 2016). In this case, the antibiotic concentrations in the highly impacted lakes would be more than sufficient to enrich resistant E. coli.

4.2. Quanti-Tray MPN versus Membrane Filtration for Putative ESBL-Ec Screening

Although more expensive, MPN formats, such as the Quanti-Tray, can be less labor-intensive for sample processing and could be helpful in scaling environmental surveillance of ESBL-Ec in specific settings. The ability of Colilert media amended with antibiotic compounds to screen for resistant E. coli in aqueous matrices using an IDEXX Quanti-Tray has been previously established (Galvin et al., 2010); however, robust comparisons with membrane filtration from environmental water samples are limited. In the current study, we found that for lakes with lower E. coli abundance, the proportion of samples positive for CRO-resistant E. coli doubled by the Quanti-Tray versus the membrane filtration method. This is consistent with another study reporting that the Quanti-Tray MPN method was more sensitive than membrane filtration for detecting putative ESBL-Ec in water samples collected from markets (Masoamphambe et al., 2021). When both methods yielded quantifiable results from lakes where E. coli were less abundant, the CRO-resistant E. coli counts were similar. On the contrary, in lakes where E. coli abundance was high, the Quanti-Tray method yielded significantly higher CRO-resistant E. coli counts. This mixed performance is consistent with another recently published study that found for pure culture treatments, TBX with cefotaxime yielded lower counts than Quanti-Tray and MacConkey agar amended with the same but produced similar concentrations for water samples spiked with an ESBL-Ec control strain (Hornsby et al., 2023).

Nonetheless, the qualitative agreement between methods was moderate across all samples from all lakes, and the log10-transformed counts of CRO-resistant E. coli were strongly correlated and demonstrated good agreement. Our results suggest that when screening for putative ESBL-Ec from water using third-generation cephalosporins, Colilert media and Quanti-Tray may yield improved sensitivity while maintaining quantitative comparability with the membrane filtration and TBX agar methods in the Tricycle Protocol. Higher sensitivity may be especially advantageous in high-income countries where ESBL-Ec are expected to be less abundant in the environment, and the additional costs associated with IDEXX consumables are more feasible.

4.3. Ceftriaxone Screening for ESBL-Ec

The WHO’s Tricycle protocol uses cefotaxime to screen for ESBL-Ec from environmental samples, whereas, in the current study, we have used ceftriaxone. Both compounds are third-generation cephalosporins, and CLSI classifies them as “equivalent agents” for testing E. coli isolates (CLSI, 2023). Clinical microbiology studies have suggested that ceftriaxone resistance with a minimum inhibitory concentration greater than 2 µg/mL is a reasonable proxy for ESBL-Ec phenotype in clinical specimens (Curello and MacDougall, 2014; Villegas et al., 2021). In our study, ceftriaxone at 4 µg/mL in TBX agar or Colilert media was poorly predictive of ESBL-Ec phenotype as determined by the combination disk test. TBX-CRO achieved maximum specificity (33%) while CQT-CRO achieved maximum sensitivity (77%). Neither method performed better than chance for predicting ESBL phenotype among CRO-resistant E. coli isolates. Such low predictive performance for ESBL phenotype among E. coli is not limited to ceftriaxone. The study that recommended cefotaxime at 4 µg/mL to screen for ESBL-Ec yielded confirmation rates of 45% for environmental water samples, while another study using cefotaxime produced confirmation rates of 23% for wastewater isolates and 44% for surface water isolates (Appling et al., 2023; Jacob et al., 2020). Conversely, an implementation of the Tricycle Protocol in Indonesia reported a confirmation rate of 84.3% for colonies grown on MacConkey agar with 0.4% cefotaxime (Puspandari et al., 2021).

Our results and those of the previous studies suggest that the efficiency of third-generation cephalosporins for screening ESBL-Ec isolates from environmental samples may be quite limited. Misclassifying environmental E. coli isolates could produce bias in One Health assessments of AMR. In clinical microbiology, interpreting susceptibility tests for ESBL production is hotly debated with known limitations due to false negatives (AmpC) and false positives (hyperactivity of a narrow spectrum beta-lactamase) (Bush and Bradford, 2020; Castanheira et al., 2021; Tamma and Humphries, 2021). Even when the ESBL phenotype classification is correct, epidemiological interpretation is greatly complicated by the multitude of genetic variants and types that confer the ESBL phenotype (Bush and Bradford, 2020). For example, there are 202 known genetic variations of TEM-type ESBLs, 200 SHV-types, and 254 CTX-types (Castanheira et al., 2021). Numerous studies of ESBL-Ec isolates from surface waters in a variety of settings have emphasized the genetic diversity of such isolates and the importance of sequence typing to better link environmental isolates to human or animal sources (Adator et al., 2020; Davidova-Gerzova et al., 2023; Hassen et al., 2020). The limited specificity of antibiotic-compound-based screening for ESBL phenotype among E. coli, as observed in the current study, and the genetic diversity of such phenotypes emphasizes the importance of genotypic characterization to maximize the value of the Tricycle Protocol for informing AMR. In our case, as in many others, sequencing the isolates was beyond the scope of the resources readily available for the project.

4.2. Antibiotic Resistance among ESBL versus Non-ESBL Ec Isolates

Among clinical isolates, ESBL-producing E. coli frequently demonstrate multi-drug resistance (MDR, resistance to compounds across 3 or more antibiotic classes) owing to the frequent co-location of ESBL encoding genes and other ARGs on plasmids. A study comparing environmental and clinical isolates in Norway found MDR was more common among clinical E. coli isolates than those from urban surface waters (Jørgensen et al., 2017). During the current study, we found extensive MDR with 89% of E. coli isolates resistant to 3 or more of the compounds tested. The mean MAR index across all four lakes exceeded 20%, which has previously been interpreted to suggest an isolate originates from a source where selective pressure from antibiotic compounds is high (Krumperman, 1983). This is consistent with observations of bacterial isolates from the environment elsewhere in India. For example, environmental isolates collected from water, sediments, and aquatic vegetation in and around Delhi demonstrated extensive MDR with MAR index greater than 20% (Gehlot and Hariprasad, 2024).

Importantly, we found no difference in the number of resistance phenotypes between ESBL versus non-ESBL E. coli isolated during the study. Instead, the number of resistance phenotypes was driven by the lake from which the isolate originated. Our experience suggests that in settings where MDR is prevalent among E. coli, it could be more efficient to test generic E. coli isolates without ESBL screening to characterize AMR, especially given the lack of specificity of third-generation cephalosporins for screening the ESBL phenotype. In our case, it is unclear what additional information was gathered in terms of resistance profiling by screening with ceftriaxone.

Conclusions

The WHO Tricycle Protocol produced ESBL-Ec abundance and prevalence estimates that reflected environmental AMR differences between highly impacted lakes subject to open defecation, animal soaking, and STP effluent versus “pristine” lakes in a wildlife sanctuary and recreational site. Impacted lakes produced significantly higher E. coli counts, CRO-resistant E. coli counts, and presumptive ESBL-Ec isolates resistant to a greater number of antibiotic compounds. The prevalence and concentration of antibiotic compounds were also higher in the highly impacted lakes.

A Colilert Quanti-Tray format of ESBL-Ec screening demonstrated reasonable qualitative and quantitative agreement with the WHO Tricycle Protocol TBX method across lakes with varying AMR profiles. In lakes where presumptive ESBL-Ec were less abundant, the Quanti-Tray format demonstrated increased sensitivity, and in lakes where presumptive ESBL-Ec were more abundant, Quanti-Tray yielded higher CRO-resistant E. coli counts. The Colilert Quanti-Tray format could be advantageous for ESBL screening in settings where such E. coli are expected to be rare.

In both the WHO Tricycle and Quanti-Tray format, ceftriaxone performed poorly in screening for the ESBL phenotype. This is consistent with observations for other third-generation cephalosporins when screening for ESBL-Ec from the environment. Confirmed ESBL phenotype was not associated with increased multidrug resistance compared to non-ESBL-Ec isolates. Instead, the multi-drug resistance of E. coli isolates was related to the lake from which the sample was collected.

Given the inaccuracy of ceftriaxone and other third-generation cephalosporins for screening ESBL-Ec from environmental samples and the many-to-one nature of ESBL genotypes versus phenotype, genetic evaluation of isolates produced via the WHO Tricycle Protocol will be critical to establish epidemiological links and risk mitigation in settings where AMR risks are highest and resources are often lowest.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization - AB, ASK; Data curation - AS, AK, ASK; Formal analysis - AB; Funding acquisition - AB, ASK; Investigation - AS, AK; Methodology - AS, AK; Project administration - ASK; Supervision - AB, ASK; Visualization - AB; Roles/Writing - original draft - AB, AS, KW, ASK; Writing - review & editing - AB, AS, KW, ASK.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset produced in the described study and used for the statistical analysis is publicly available at:

https://osf.io/rz4f5/ DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/RZ4F5.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Thol Bird Sanctuary for allowing access for weekly water sampling and the National Forensic Sciences University for providing transportation for sample collection.

References

- Adator, E.H.; Walker, M.; Narvaez-Bravo, C.; Zaheer, R.; Goji, N.; Cook, S.R.; Tymensen, L.; Hannon, S.J.; Church, D.; Booker, C.W.; Amoako, K.; Nadon, C.A.; Read, R.; McAllister, T.A. Whole Genome Sequencing Differentiates Presumptive Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Escherichia coli along Segments of the One Health Continuum. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlstrom, C.A.; Bonnedahl, J.; Woksepp, H.; Hernandez, J.; Olsen, B.; Ramey, A.M. Acquisition and dissemination of cephalosporin-resistant E. coli in migratory birds sampled at an Alaska landfill as inferred through genomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appling, K.C.; Sobsey, M.D.; Durso, L.M.; Fisher, M.B. Environmental monitoring of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in North Carolina water and wastewater using the WHO Tricycle protocol in combination with membrane filtration and compartment bag test methods for detecting and quantifying ESBL E. coli. PLOS Water 2023, 2, e0000117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, R.A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Reid, A.J.; Enbiale, W.; Labi, A.-K.; Ansa, E.D.O.; Annan, E.A.; Akrong, M.O.; Borbor, S.; Adomako, L.A.B.; Ahmed, H.; Mustapha, M.B.; Davtyan, H.; Owiti, P.; Hedidor, G.K.; Quarcoo, G.; Opare, D.; Kikimoto, B.; Osei-Atweneboana, M.Y.; Schmitt, H. Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Escherichia coli in River Waters Collected from Two Cities in Ghana, 2018–2020. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Larsson, D.G.J. Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, B. Environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and correlation to anthropogenic contamination with antibiotics. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 28564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih, Y.M.; Sabiiti, W.; Alamneh, E.; Bezabih, A.; Peterson, G.M.; Bezabhe, W.M.; Roujeinikova, A. The global prevalence and trend of human intestinal carriage of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, 10.1128/cmr.00047-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarco, J.; Pruden, A.; Harwood, V.J. Comparison of methods proposed for monitoring cefotaxime-resistant Escherichia coli in the water environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e02128-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; Bradford, P.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chereau, F.; Opatowski, L.; Tourdjman, M.; Vong, S. Risk assessment for antibiotic resistance in South East Asia. BMJ 2017, 358, j3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI, 2023. M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 33rd Edition. CLSI.

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curello, J.; MacDougall, C. Beyond Susceptible and Resistant, Part II: Treatment of Infections Due to Gram-Negative Organisms Producing Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 19, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.K.; Das, S.; Srivastava, P.K. An overview on the prevalence and potential impact of antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance in the aquatic environment of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidova-Gerzova, L.; Lausova, J.; Sukkar, I.; Nesporova, K.; Nechutna, L.; Vlkova, K.; Chudejova, K.; Krutova, M.; Palkovicova, J.; Kaspar, J.; Dolejska, M. Hospital and community wastewater as a source of multidrug-resistant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, V.; Hanna, N.; Purohit, M.; Chandran, S.; Riggi, E.; Parashar, V.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Stålsby Lundborg, C. Seasonal Variations in Water-Quality, Antibiotic Residues, Resistant Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes of Escherichia coli Isolates from Water and Sediments of the Kshipra River in Central India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Iovleva, A.; Bonomo, R.A. The ecology of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in the developed world. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, S44–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsohaby, I.; Samy, A.; Elmoslemany, A.; Alorabi, M.; Alkafafy, M.; Aldoweriej, A.; Al-Marri, T.; Elbehiry, A.; Fayez, M. Migratory Wild Birds as a Potential Disseminator of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria around Al-Asfar Lake, Eastern Saudi Arabia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, S.; Boyle, F.; Hickey, P.; Vellinga, A.; Morris, D.; Cormican, M. Enumeration and Characterization of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli Bacteria in Effluent from Municipal, Hospital, and Secondary Treatment Facility Sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 4772–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlot, P.; Hariprasad, P. Unveiling the ecological landscape of bacterial β-lactam resistance in Delhi-national capital region, India: An emerging health concern. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 363, 121288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X. On Statistical Measures for Data Quality Evaluation. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2020, 12, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.; Abbassi, M.S.; Benlabidi, S.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Mama, O.M.; Ibrahim, C.; Hassen, A.; Hammami, S.; Torres, C. Genetic characterization of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from wastewater and river water in Tunisia: predominance of CTX-M-15 and high genetic diversity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44368–44377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsby, G.; Ibitoye, T.D.; Keelara, S.; Harris, A. Validation of a modified IDEXX defined-substrate assay for detection of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in environmental reservoirs. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzicki, J., 2009. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol. ASM.

- IFPMA, 2024. From resistance to resilience: what could the future antibiotic pipeline look like?

- Islam, K.; Heffernan, A.J.; Naicker, S.; Henderson, A.; Chowdhury, M.A.H.; Roberts, J.A.; Sime, F.B. Epidemiology of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase and Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli in South Asia. Future Microbiol. 2021, 16, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md.S., Sobur, Md.A., Rahman, S., Ballah, F.M., Ievy, S., Siddique, M.P., Rahman, M., Kafi, Md.A., Rahman, Md.T. Detection of blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaCMY, and blaSHV Genes Among Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Migratory Birds Travelling to Bangladesh. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 83, 942–950. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.E.; Keelara, S.; Aidara-Kane, A.; Matheu Alvarez, J.R.; Fedorka-Cray, P.J. Optimizing a Screening Protocol for Potential Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Escherichia coli on MacConkey Agar for Use in a Global Surveillance Program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 10.1128/jcm.01039-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Ginn, O.; Bivins, A.; Rocha-Melogno, L.; Tripathi, S.N.; Brown, J. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Escherichia coli presence in urban aquatic environments in Kanpur, India. J. Water Health 2020, 18, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.B.; Søraas, A.V.; Arnesen, L.S.; Leegaard, T.M.; Sundsfjord, A.; Jenum, P.A. A comparison of extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli from clinical, recreational water and wastewater samples associated in time and location. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0186576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumperman, P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuralayanapalya, S.P.; Patil, S.S.; Hamsapriya, S.; Shinduja, R.; Roy, P.; Amachawadi, R.G. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing bacteria from animal origin: A systematic review and meta-analysis report from India. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0221771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lübbert, C.; Baars, C.; Dayakar, A.; Lippmann, N.; Rodloff, A.C.; Kinzig, M.; Sörgel, F. Environmental pollution with antimicrobial agents from bulk drug manufacturing industries in Hyderabad, South India, is associated with dissemination of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing pathogens. Infection 2017, 45, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhang, H.; Bi, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Xu, X.; Sun, R.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Characteristics of Wild Bird Resistomes and Dissemination of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Interconnected Bird-Habitat Systems Revealed by Similarity of blaTEM Polymorphic Sequences. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15084–15095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoamphambe, E., Cocker, D., Feasey, N., Berendes, D., Kirby, A., Chidziwisano, K., Panulo, W., Morse, T., 2021. A NOVEL ESBL COLILERT SYSTEM FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SURVEILLANCE OF AMR BACTERIA AT MARKETS IN LMICS.

- Mejías, C.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Sánchez, M.I.; Alonso, E. Development and validation of a highly effective analytical method for the evaluation of the exposure of migratory birds to antibiotics and their metabolites by faeces analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 3373–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munita, J.M.; Arias, C.A. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 10.1128/microbiolspec.vmbf-0016–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C.; Browne, A.J.; Chipeta, M.G.; Fell, F.; Hackett, S.; Haines-Woodhouse, G.; Kashef Hamadani, B.H.; Kumaran, E.A.P.; McManigal, B.; Agarwal, R.; Akech, S.; Albertson, S.; Amuasi, J.; Andrews, J.; Aravkin, A.; Ashley, E.; Bailey, F.; Baker, S.; Basnyat, B.; Bekker, A.; Bender, R.; Bethou, A.; Bielicki, J.; Boonkasidecha, S.; Bukosia, J.; Carvalheiro, C.; Castañeda-Orjuela, C.; Chansamouth, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Chiurchiù, S; Chowdhury, F.; Cook, A.J.; Cooper, B.; Cressey, T.R.; Criollo-Mora, E.; Cunningham, M.; Darboe, S.; Day, N.P.J.; De Luca, M.; Dokova, K.; Dramowski, A.; Dunachie, S.J.; Eckmanns, T.; Eibach, D.; Emami, A.; Feasey, N.; Fisher-Pearson, N.; Forrest, K.; Garrett, D.; Gastmeier, P.; Giref, A.Z.; Greer, R.C.; Gupta, V.; Haller, S.; Haselbeck, A.; Hay, S.I.; Holm, M.; Hopkins, S.; Iregbu, K.C.; Jacobs, J.; Jarovsky, D.; Javanmardi, F.; Khorana, M.; Kissoon, N.; Kobeissi, E.; Kostyanev, T.; Krapp, F.; Krumkamp, R.; Kumar, A.; Kyu, H.H.; Lim, C.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Loftus, M.J.; Lunn, M.; Ma, J.; Mturi, N.; Munera-Huertas, T.; Musicha, P.; Mussi-Pinhata, M.M.; Nakamura, T.; Nanavati, R.; Nangia, S.; Newton, P.; Ngoun, C.; Novotney, A.; Nwakanma, D.; Obiero, C.W.; Olivas-Martinez, A.; Olliaro, P.; Ooko, E.; Ortiz-Brizuela, E.; Peleg, A.Y.; Perrone, C.; Plakkal, N.; Ponce-de-Leon, A.; Raad, M.; Ramdin, T.; Riddell, A.; Roberts, T.; Robotham, J.V.; Roca, A.; Rudd, K.E.; Russell, N.; Schnall, J.; Scott, J.A.G.; Shivamallappa, M.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J.; Steenkeste, N.; Stewardson, A.J.; Stoeva, T.; Tasak, N.; Thaiprakong, A.; Thwaites, G.; Turner, C.; Turner, P.; van Doorn, H.R.; Velaphi, S.; Vongpradith, A.; Vu, H.; Walsh, T.; Waner, S.; Wangrangsimakul, T.; Wozniak, T.; Zheng, P.; Sartorius, B.; Lopez, A.D.; Stergachis, A.; Moore, C.; Dolecek, C.; Naghavi, M. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- Nadimpalli, M.L.; Marks, S.J.; Montealegre, M.C.; Gilman, R.H.; Pajuelo, M.J.; Saito, M.; Tsukayama, P.; Njenga, S.M.; Kiiru, J.; Swarthout, J.; Islam, M.A.; Julian, T.R.; Pickering, A.J. Urban informal settlements as hotspots of antimicrobial resistance and the need to curb environmental transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, H.B.; Kadir, S.A.; Arivalan, S.; Osman, S.; Mohamed, R.; Ng, L.C.; Wong, J.C.; Octavia, S. Screening for Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Escherichia Coli in Recreational Beach Waters in Singapore. Future Microbiol. 2023, 18, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruden, A.; Vikesland, P.J.; Davis, B.C.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Seizing the moment: now is the time for integrated global surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in wastewater environments. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 64, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspandari, N.; Sunarno, S.; Febrianti, T.; Febriyana, D.; Saraswati, R.D.; Rooslamiati, I.; Amalia, N.; Nursofiah, S.; Hartoyo, Y.; Herna, H.; Mursinah, M.; Muna, F.; Aini, N.; Risniati, Y.; Dhewantara, P.W.; Allamanda, P.; Wicaksana, D.N.; Sukoco, R.; Efadeswarni Nelwan, E.J.; Cahyarini Haryanto, B.; Sihombing, B.; Soares Magalhães, R.J.; Kakkar, M.; Setiawaty, V.; Matheu, J. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli surveillance in the human, food chain, and environment sectors: Tricycle project (pilot) in Indonesia. One Health 2021, 13, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppé, E. Lessons from a global antimicrobial resistance surveillance network. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, D.; Louise Wester, A.; Schmitt, H.; Amarasiri, M.; Kirby, A.; Medlicott, K.; >Roda Husman, A.M.d. Updated research agenda for water sanitation antimicrobial resistance. J. Water Health 2020, 18, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.S.; Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Virdi, J.S. High Prevalence of Drug Resistance and Class 1 Integrons in Escherichia coli Isolated From River Yamuna, India: A Serious Public Health Risk. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spearman, C. The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, I.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Gogry, F.A.; Haq, Q.M.o.h.d.R. Molecular characterization of resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements of ESBL producing multidrug-resistant bacteria from freshwater lakes in Kashmir, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacão, M.; Correia, A.; Henriques, I. Resistance to Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics in Aquatic Systems: Anthropogenic Activities Modulate the Dissemination of bla CTX-M-Like Genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4134–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Humphries, R.M. PRO: Testing for ESBL production is necessary for ceftriaxone-non-susceptible Enterobacterales: perfect should not be the enemy of progress. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, N.; Sharma, M. Antimicrobial resistance in the environment: The Indian scenario. Indian J. Med. Res. 2019, 149, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiyapuri, M.; Sebastian, A.S.; George, I.; Variem, S.S.; Vasudevan, R.N.; George, J.C.; Badireddy, M.R.; Sivam, V.; Peeralil, S.; Sanjeev, D.; Thandapani, M.; Moses, S.A.; Nagarajarao, R.C.; Mothadaka, M.P. Predominance of genetically diverse ESBL Escherichia coli identified in resistance mapping of Vembanad Lake, the largest fresh-cum-brackishwater lake of India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 66206–66222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas, M.V.; Esparza, G.; Reyes, J. Should ceftriaxone-resistant Enterobacterales be tested for ESBLs? A PRO/CON debate. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, 2024. WHO bacterial priority pathogens list, 2024: Bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance. WHO, Geneva.

- WHO, 2023. Antimicrobial resistance [WWW Document]. URL https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed 8.16.24).

- WHO, 2021. WHO integrated global surveillance on ESBL-producing E. coli using a “One Health” approach: Implementation and opportunities. WHO.

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).