2 Pós-Graduação em Medicina Translacional, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil

1. Introduction

Despite the considerable challenges in rigorously evaluating anesthetic techniques that minimize or completely avoid classical opioids, the imperative to control the widespread diffusion of these drugs provides a strong scientific and societal incentive to pursue alternatives. Opioids remain medications with a high potential for dependence and tolerance, and their availability within and beyond the perioperative setting can have catastrophic consequences. The global burden of opioid-related harm is striking: the World Health Organization estimates that opioids account for approximately 80% of drug-related deaths, with a substantial proportion due to overdose [

1]. In the United States, the proliferation of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl has driven an almost tenfold increase in overdose fatalities over the last decade [

2]. Furthermore, perioperative opioid exposure has been identified as a critical risk factor for persistent opioid use, dependence, and overdose, highlighting the urgent need for “opioid stewardship” and safer anesthetic practices [

3]. Within this context, opioid-free and opioid-sparing anesthetic strategies emerge not only as scientific innovations but also as necessary responses to a pressing global health crisis.

Laparoscopic surgery has become the standard of care across many specialties—including general, gynecological, urological, and bariatric surgery thanks to advantages such as smaller incisions, reduced blood loss, and faster functional recovery compared with open techniques [

4]. Despite these benefits, the perioperative period remains fraught with challenges, including postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, delayed recovery, and complications related to anesthetic management. Traditionally, intraoperative analgesia has relied on opioid-based anesthesia (OBA), most often with fentanyl or remifentanil, to maintain hemodynamic stability and blunt nociceptive responses. However, the use of opioids is well known to cause adverse effects such as respiratory depression, ileus, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, hyperalgesia, tolerance, and the risk of prolonged exposure contributing to chronic use [

5].

In response to these concerns, opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) has emerged as a multimodal alternative. OFA replaces intraoperative opioids with combinations of non-opioid agents including dexmedetomidine, ketamine or esketamine, lidocaine, magnesium, and esmolol often in conjunction with regional techniques or structured multimodal postoperative analgesia. The rationale for OFA is to maintain effective nociceptive control while reducing opioid-related side effects, thereby accelerating recovery and potentially improving patient satisfaction.

In recent years, OFA has been tested across a variety of laparoscopic procedures. Sixteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs), conducted between 2007 and 2025, have compared OFA and OBA in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, gynecologic laparoscopy, bariatric surgery, colorectal surgery, and urological procedures. Collectively, these trials suggest that OFA can reduce postoperative opioid consumption and, in several studies, decrease the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Pain outcomes within the first 24 hours are often similar between groups, although modest improvements have been reported in certain populations. Nonetheless, concerns remain regarding hemodynamic instability particularly bradycardia and hypotension in dexmedetomidine-based regimens as well as slightly prolonged emergence or recovery times.

Despite increasing interest, significant heterogeneity persists in the implementation of OFA. Variability in drug selection, dosing strategies, surgical populations, and outcome definitions has produced conflicting results across trials. Furthermore, earlier reviews frequently combined observational studies or non-laparoscopic surgeries, limiting the strength of their conclusions.

This systematic review and meta-analysis seeks to provide a rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of OFA compared with OBA in adult patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. By including only randomized controlled trials, the analysis offers high-quality evidence on clinically relevant outcomes such as postoperative pain, PONV, opioid consumption, recovery quality, and perioperative complications. The findings aim to inform anesthetic practice in minimally invasive surgery and guide the design of future multicenter trials to establish standardized OFA protocols.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [

7] and reported according to the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement

[6]. The protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database under the registration number CRD4202451376

2 [

8].

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) with opioid-based anesthesia (OBA) in adult patients (≥18 years) undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery. Eligible studies were required to randomize patients to an intraoperative regimen explicitly defined as opioid-free most commonly based on multimodal combinations of dexmedetomidine, ketamine or esketamine, lidocaine, magnesium, or esmolol versus a regimen including intraoperative opioids, typically remifentanil or fentanyl. Studies were considered eligible if they reported at least one relevant clinical outcome, including postoperative pain intensity, incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), intraoperative or postoperative opioid consumption, quality of recovery, hemodynamic stability, length of hospital stay, or adverse events.

Trials were excluded if they enrolled pediatric populations, involved non-laparoscopic procedures, or reported outcomes that could not be separately extracted for laparoscopic patients. Observational studies, case series, single-arm trials, and investigations lacking a clearly defined comparator group were also excluded, to preserve methodological rigor and reduce risk of bias.

Following these criteria, 16 RCTs published between 2007 and 2025 were ultimately included in the final qualitative and quantitative syntheses. This exclusive focus on randomized evidence was designed to ensure methodological consistency, maximize internal validity, and provide high-quality evidence to inform perioperative practice regarding OFA in minimally invasive surgery.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the use of opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) compared with opioid-based anesthesia (OBA) in adult patients (≥18 years) undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery. Eligible studies were required to clearly randomize patients into an intraoperative anesthetic regimen explicitly described as opioid-free most commonly based on combinations of dexmedetomidine, esketamine or ketamine, lidocaine, magnesium, or esmolol versus a regimen including intraoperative opioids, typically remifentanil or fentanyl. To be included, trials had to report at least one clinically relevant outcome, such as postoperative pain intensity, incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), intraoperative or postoperative opioid consumption, hemodynamic stability, length of hospital stay, or measures of quality of recovery.

Trials enrolling patients undergoing a variety of laparoscopic procedures—including cholecystectomy, gynecological laparoscopy, bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy), colorectal surgery, and urological laparoscopic procedures were eligible, provided that the anesthesia protocols were clearly defined as opioid-free versus opioid-based.

Studies were excluded if they involved pediatric patients, emergency surgical procedures, or if laparoscopic outcomes could not be analyzed separately from other surgical cohorts. Observational studies, case series, single-arm trials, and investigations without a clearly defined comparator group were also excluded to preserve methodological consistency and reduce risk of bias.

After applying these criteria, 16 RCTs published between 2007 and 2025 were included in the final qualitative and quantitative syntheses. Restricting inclusion to randomized trials ensured homogeneity of study design and strengthened the internal validity of the meta-analysis, in line with the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and recent systematic reviews of anesthetic strategies.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across five electronic databases: PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The initial search was performed in January 2024 and subsequently updated in August 2025 to capture the most recent studies. In addition, the reference lists of all included articles and relevant systematic reviews were manually screened to identify additional eligible trials not retrieved by the electronic search. Gray literature and unpublished data available in trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP) were also considered.

The search strategy was developed to maximize sensitivity by combining Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to “opioid-free anesthesia”, “opioid-based anesthesia”, “laparoscopic surgery”, and “randomized controlled trial”. No language or publication date restrictions were applied. All stages of the search and study selection process were carried out in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

The final search yielded 16 randomized controlled trials published between 2007 and 2025, which fulfilled all eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative and quantitative syntheses of this review.

2.3. Study Selection

Titles and abstracts retrieved from the comprehensive database search were independently screened by four reviewers (CDAB, MRB, LFGP, VAF) using a standardized eligibility protocol [

7]. All records were imported into Rayyan® (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar) [

9] to facilitate blinded screening, conflict detection, and reviewer collaboration. Full-text articles were retrieved for all studies deemed potentially relevant during the initial screening phase.

Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus, and when necessary, adjudicated by a senior investigator (JEGP or LFRF). The entire screening process was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [

6].

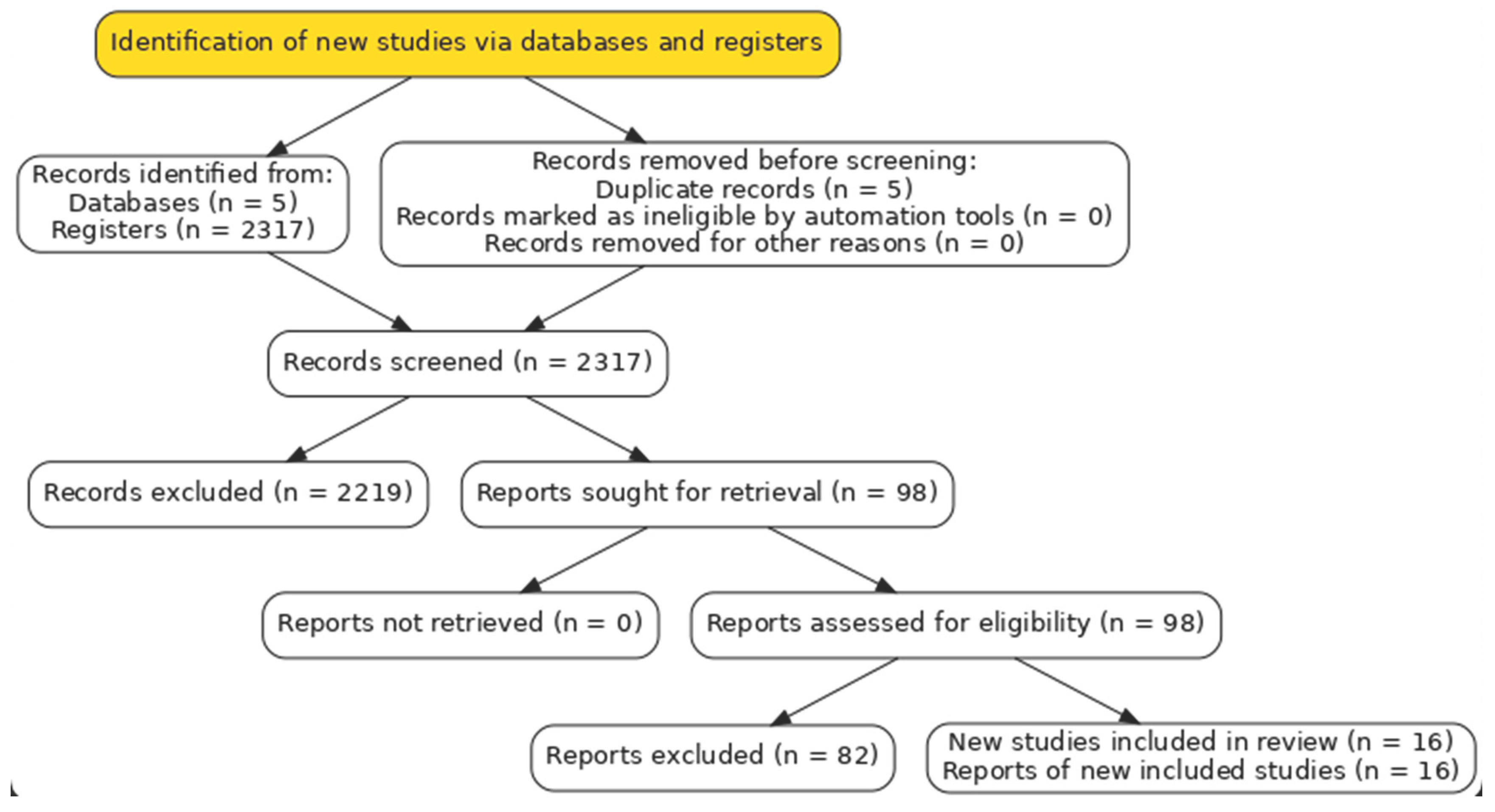

From the initial search set, after duplicate removal and screening, 98 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 82 were excluded, most commonly due to absence of a randomized design, inadequate definition of the OFA versus OBA intervention, inclusion of non-laparoscopic surgical populations, or insufficient outcome data. Ultimately, 16 RCTs met all predefined criteria and were included in the final qualitative and quantitative syntheses. The study selection process is summarized in

Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram) [

6].

2.4. Data Extraction and Management

Data from all 16 included randomized controlled trials were independently extracted by two reviewers (CDAB and MRB) using a standardized, piloted extraction form developed in accordance with

Cochrane guidelines [

7]. Extracted information comprised study characteristics (first author, year of publication, country, study design, trial registration), patient demographics (sample size, age, sex distribution, ASA status, BMI), surgical details (type of laparoscopic procedure), anesthetic protocols (OFA regimen, OBA regimen, co-interventions), and reported outcomes.

The primary outcomes of interest were postoperative pain intensity, the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and perioperative opioid consumption, including the need for rescue opioids. Secondary outcomes, defined according to the variables consistently reported across the 16 included randomized controlled trials, comprised quality of recovery, intraoperative hemodynamic stability, length of hospital stay, and adverse events.

When relevant data were missing or unclear, attempts were made to

contact study authors for clarification [

7]. Any disagreements in data extraction were resolved through consensus, and unresolved discrepancies were adjudicated by a third reviewer (LFGP or CDAB).

All extracted data were entered into RevMan (Review Manager), version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration) for meta-analysis [

10], and accuracy of data entry was cross-checked by a second investigator to ensure consistency.

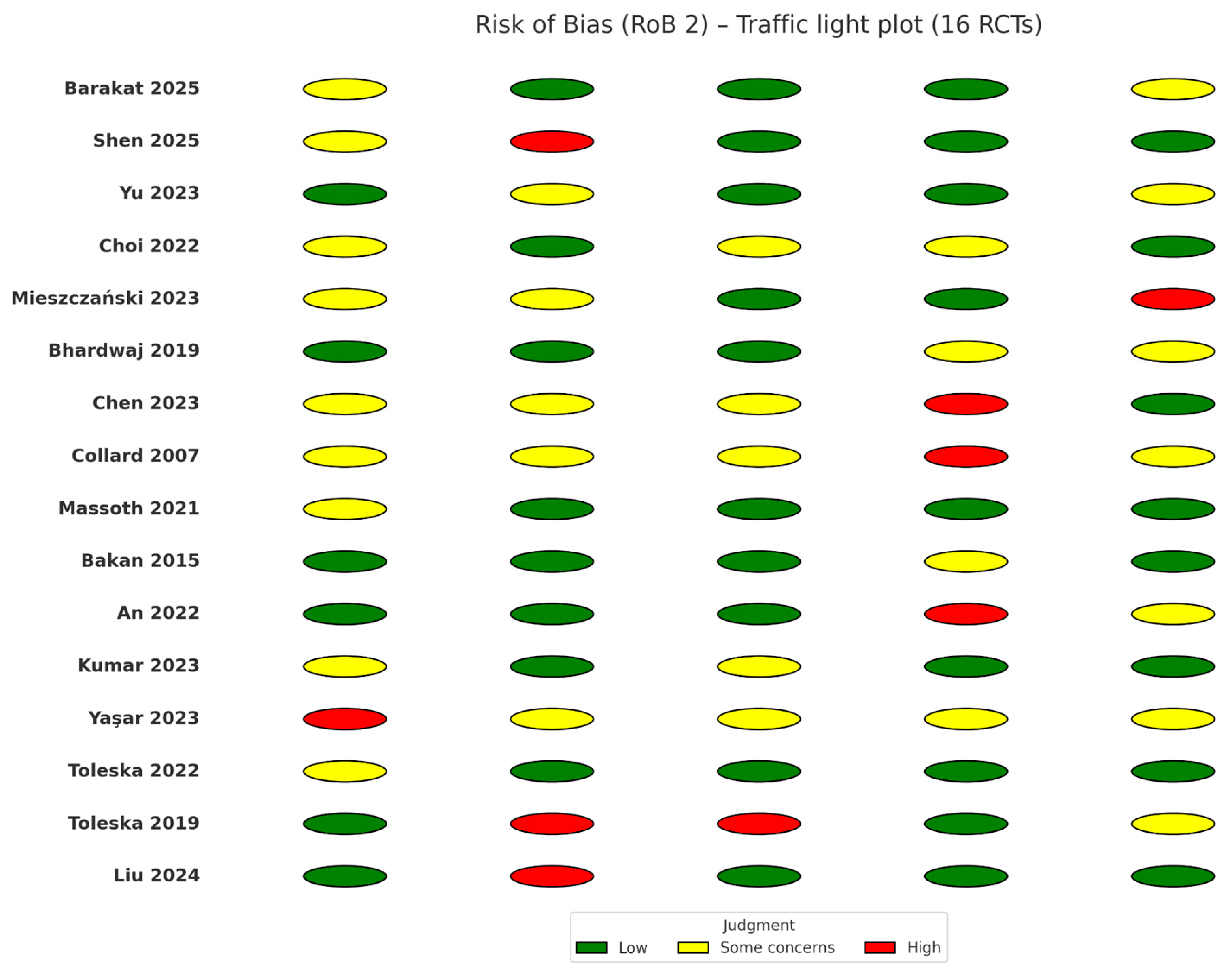

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias for all 16 included randomized controlled trials was independently assessed by two reviewers (CDAB and MRB) using the

Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool [

11]. The following domains were evaluated: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. Each domain was rated as low risk of bias, some concerns, or high risk of bias, and an overall risk-of-bias judgment was assigned for each trial.

Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through consensus, and when necessary, adjudicated by a third investigator (LFGP or CDAB).

Graphical summaries of risk-of-bias assessments across all domains and studies were generated using

RevMan (version 5.4) [

12] and are presented in

Figure 2.

Overall, the majority of trials were judged at low risk of bias or some concerns, primarily due to incomplete reporting of allocation concealment or lack of explicit blinding of outcome assessors. None of the included RCTs were judged to have a high overall risk of bias that would preclude their inclusion in the quantitative synthesis.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration) [

12] and Stata (version 17.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) [

13]. Continuous outcomes, such as postoperative pain scores and opioid consumption, were analyzed as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). When studies reported pain using different scales, outcomes were converted to a standardized 0–10 scale, and results were summarized as standardized mean differences (SMD). Dichotomous outcomes, including incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) or adverse events, were analyzed as risk ratios (RR) with corresponding 95% CIs.

Given the expected methodological and clinical heterogeneity across the included trials, a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird) was used as the primary approach for all pooled analyses [

14]. Fixed-effects models were conducted as sensitivity analyses. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using the I² statistic, with thresholds of 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [

15]. Sources of heterogeneity were explored through predefined subgroup analyses (e.g., type of laparoscopic procedure, OFA regimens with vs. without dexmedetomidine, OBA based on remifentanil vs. fentanyl) and sensitivity analyses excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias.

When at least ten trials were available for an outcome, publication bias was evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plots and formally tested using Egger’s regression test [

16]. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence for all key outcomes—postoperative pain intensity, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption, hemodynamic adverse events (bradycardia, hypotension), quality of recovery, and length of hospital stay—was assessed using the

GRADE approach [

17,

18]. Two reviewers (CDAB, LFGP) independently judged the five GRADE domains—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (LFGP or CDAB) [

17,

18].

Because the body of evidence comprised randomized controlled trials, each outcome started at high certainty and was downgraded when domain-specific concerns were identified [

17]. Risk-of-bias judgments drew on the RoB 2.0 assessments for individual trials [

11]. Inconsistency was considered when between-study heterogeneity (I²) was moderate to high or when effect directions varied meaningfully across trials [

15,

17]. Indirectness was appraised with respect to population, intervention fidelity (clear OFA vs OBA), and applicability to elective laparoscopic settings [

17]. Imprecision was evaluated using 95% confidence interval width, optimal information size, and overlap with thresholds of clinical importance [

17]. Publication bias was explored through funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s test when ≥10 studies contributed to a given outcome [

16,

17].

Findings are summarized in

Summary of Findings tables, presenting pooled effect estimates with 95% CIs and the corresponding GRADE certainty ratings (high, moderate, low, very low) [

18].

3. Result

3.1. Search Results

A total of 2,322 records were identified through the comprehensive search strategy conducted across electronic databases and clinical trial registries. Following the removal of 5 duplicates, 2,317 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 1,713 records were excluded according to the predefined eligibility criteria.

In the next stage, 98 full-text articles were retrieved and evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 82 articles were excluded, most frequently due to the absence of a randomized design, inadequate or unclear definition of OFA versus OBA protocols, inclusion of non-laparoscopic, pediatric, or emergency surgical populations, or insufficient outcome data for extraction. No additional eligible studies were identified through manual searches of reference lists or trial registries.

Ultimately, 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published between 2007 and 2025 fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into both the qualitative and quantitative syntheses. All trials recruited adult patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery and compared an explicitly defined opioid-free anesthetic regimen with a conventional opioid-based approach. Collectively, these studies enrolled over 1,300 participants, with comparable numbers allocated to the OFA and OBA groups. The selection process is depicted in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 1) [

6].

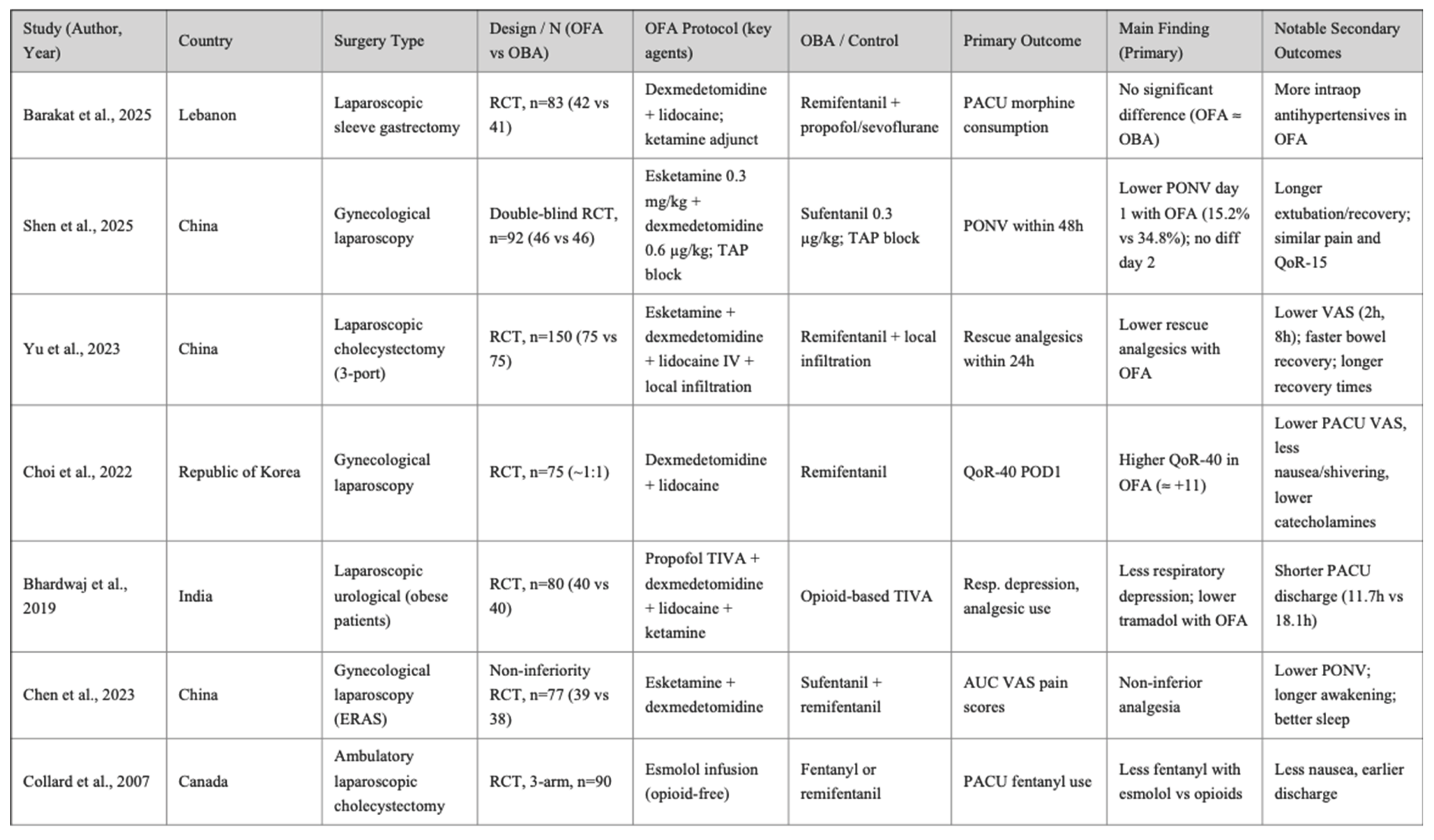

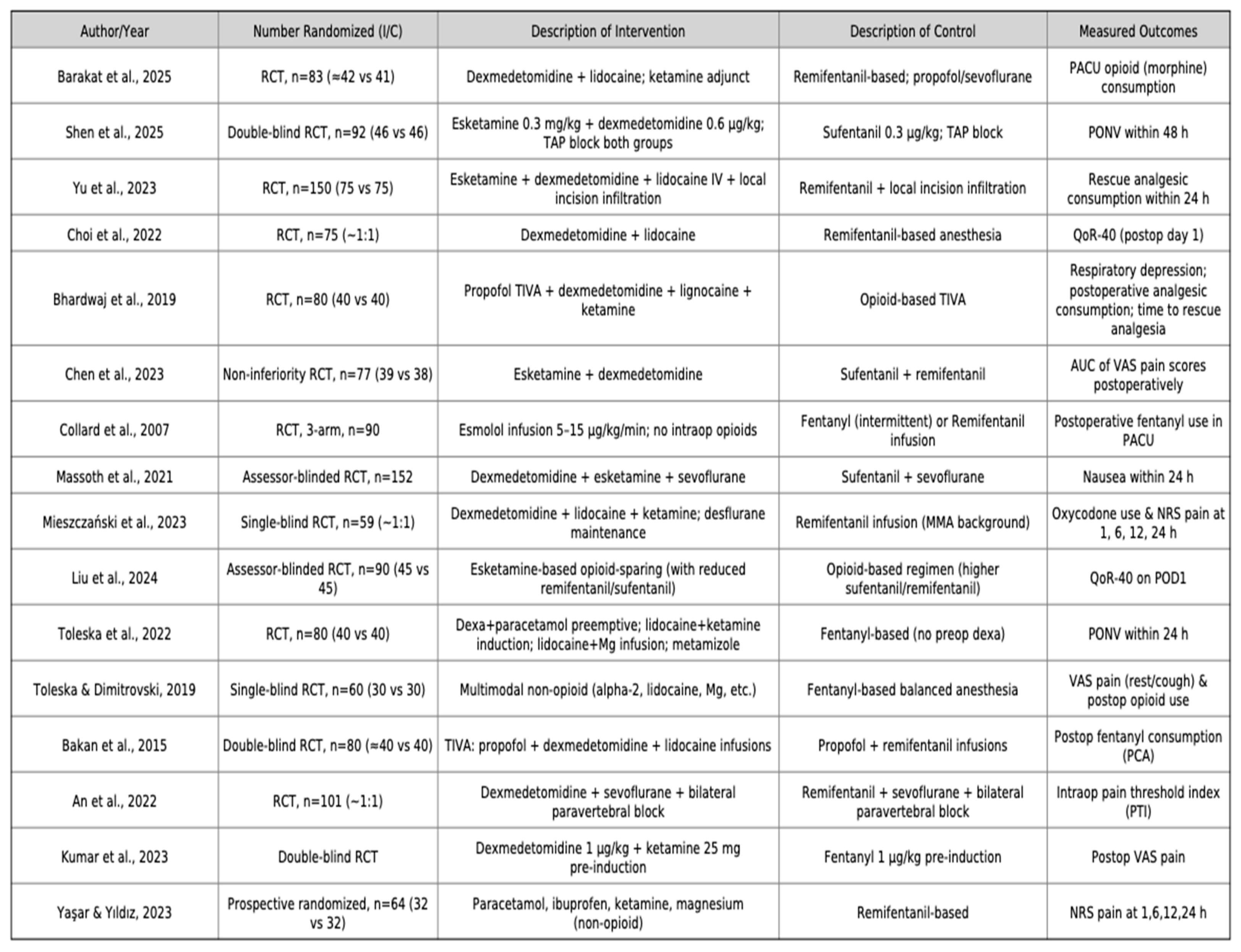

3.2. Study Characteristics

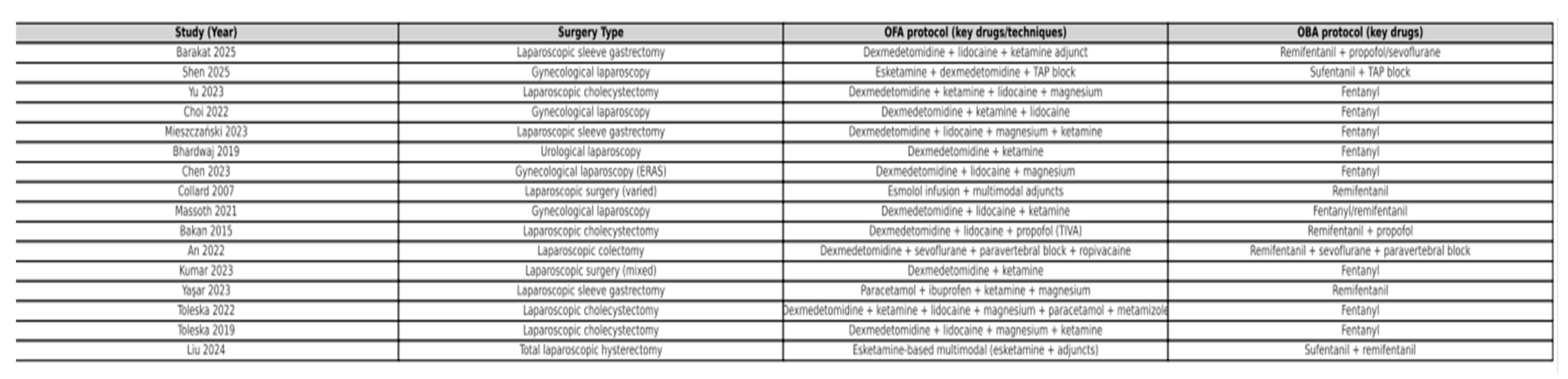

The 16 randomized controlled trials included in this review were published between 2007 and 2025, spanning a wide range of surgical specialties. All studies were single-center trials, with sample sizes ranging from 40 to 152 patients, and collectively enrolled approximately 1,350 adult participants undergoing elective laparoscopic procedures.

Types of surgery. The most frequent procedures were laparoscopic cholecystectomy (six trials), followed by gynecological laparoscopic surgery (four trials), bariatric surgery including laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (three trials), laparoscopic colectomy (one trial), and urological laparoscopic surgery (one trial). Across all procedures, study populations were generally classified as ASA I–III, with mean ages ranging from 35 to 55 years. A balanced sex distribution was reported in most studies, except for those restricted to gynecological indications.

OFA regimens. Opioid-free anesthesia strategies were consistently multimodal, although with some variation in drug selection and combinations. The most commonly used agents were dexmedetomidine, ketamine, lidocaine, magnesium sulfate, and esmolol, combined with hypnotics such as propofol or sevoflurane. Several studies additionally incorporated regional blocks (e.g., paravertebral block) or non-opioid adjuncts (NSAIDs, acetaminophen, metamizole) as part of the multimodal analgesia regimen.

OBA regimens. Control groups received conventional opioid-based anesthesia, most frequently with remifentanil or fentanyl, alongside standard hypnotics (propofol or sevoflurane). In most studies, background multimodal analgesia (NSAIDs, acetaminophen, antiemetics) was also provided in both groups to ensure comparability.

Reported outcomes. Primary outcomes most frequently included postoperative pain intensity, incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and perioperative opioid consumption (including rescue use). Secondary outcomes included quality of recovery (QoR), intraoperative hemodynamic stability, length of hospital stay, recovery times, and adverse events.

Detailed characteristics of the included populations, anesthetic regimens, and study protocols are summarized in

Table 1 (study population and setting),

Table 2 Study characteristics related to intervention and control groups. and

Table 3 (OFA and OBA anesthetic protocols).

3.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

The risk of bias across the 16 included randomized controlled trials was assessed using the

Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool [

11]. Overall, seven trials were judged to be at low risk of bias across all domains, while the remaining studies were rated as having “some concerns,” mainly due to incomplete reporting of allocation concealment and insufficient details on blinding of outcome assessors. Importantly, none of the included trials were classified as having a high overall risk of bias.

Randomization process. Most studies employed adequate random sequence generation methods, such as computer-generated lists or sealed opaque envelopes. However, allocation concealment was inconsistently reported, raising some concerns in four trials.

Deviations from intended interventions. Interventions were generally implemented as planned, with no evidence of systematic cross-over between study groups. In a few trials, intraoperative rescue opioids were allowed in the OFA arm when clinically indicated. While consistent with pragmatic trial design, this approach introduced minor concerns regarding adherence to the protocol.

Missing outcome data. Attrition was low (<5%) in nearly all studies, and outcome data were largely complete. One trial excluded patients who required conversion to open surgery; however, this was judged to introduce a low risk of bias given the small number of excluded cases.

Measurement of the outcome. Pain intensity and PONV were consistently measured using validated instruments (VAS, NRS, or standardized PONV scores). Nevertheless, blinding of outcome assessors was not always clearly described, resulting in some concerns in six trials.

Selection of the reported results. Most trials reported prespecified primary outcomes. However, selective reporting of secondary outcomes—such as recovery scores or hemodynamic variables—was suspected in three trials due to inconsistencies between the methods and results sections.

A graphical summary of the risk-of-bias assessment is provided in

Figure 2, presenting domain-level judgments for each included study,

generated using RevMan (version 5.4) [

12].

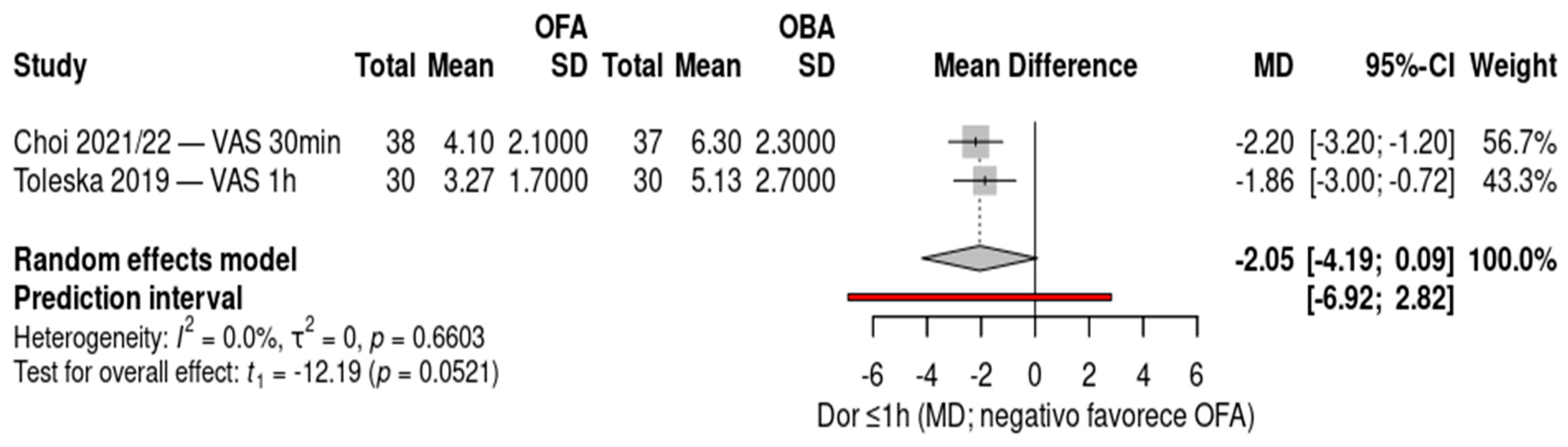

3.5. Meta-Analysis

The forest plot compares postoperative pain scores within one hour between opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) and opioid-based anesthesia (OBA), including two randomized controlled trials: Choi 2021/22 (gynecologic laparoscopy, 30 minutes) and Toleska 2019 (laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 1 hour), totaling 135 patients. Both studies demonstrated significantly lower pain scores in the OFA group compared with the OBA group, with mean differences of –2.20 (95% CI –3.20 to –1.20) and –1.86 (95% CI –3.00 to –0.72), respectively. The pooled random-effects analysis showed an overall mean difference of –2.05 (95% CI –4.19 to 0.09; p = 0.0521), indicating a trend toward reduced early postoperative pain with OFA, although the confidence interval crossed the line of no effect. No heterogeneity was observed (I² = 0%), and the prediction interval (–6.92 to 2.82) suggests consistency of the effect across similar clinical contexts. Negative values favor OFA.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of postoperative pain scores within one hour (VAS/NRS) comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Two randomized controlled trials were included (Choi 2021/22 and Toleska 2019), showing a trend toward reduced pain in the OFA group (overall MD –2.05, 95% CI –4.19 to 0.09; p = 0.0521) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Negative values favor OFA.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of postoperative pain scores within one hour (VAS/NRS) comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Two randomized controlled trials were included (Choi 2021/22 and Toleska 2019), showing a trend toward reduced pain in the OFA group (overall MD –2.05, 95% CI –4.19 to 0.09; p = 0.0521) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Negative values favor OFA.

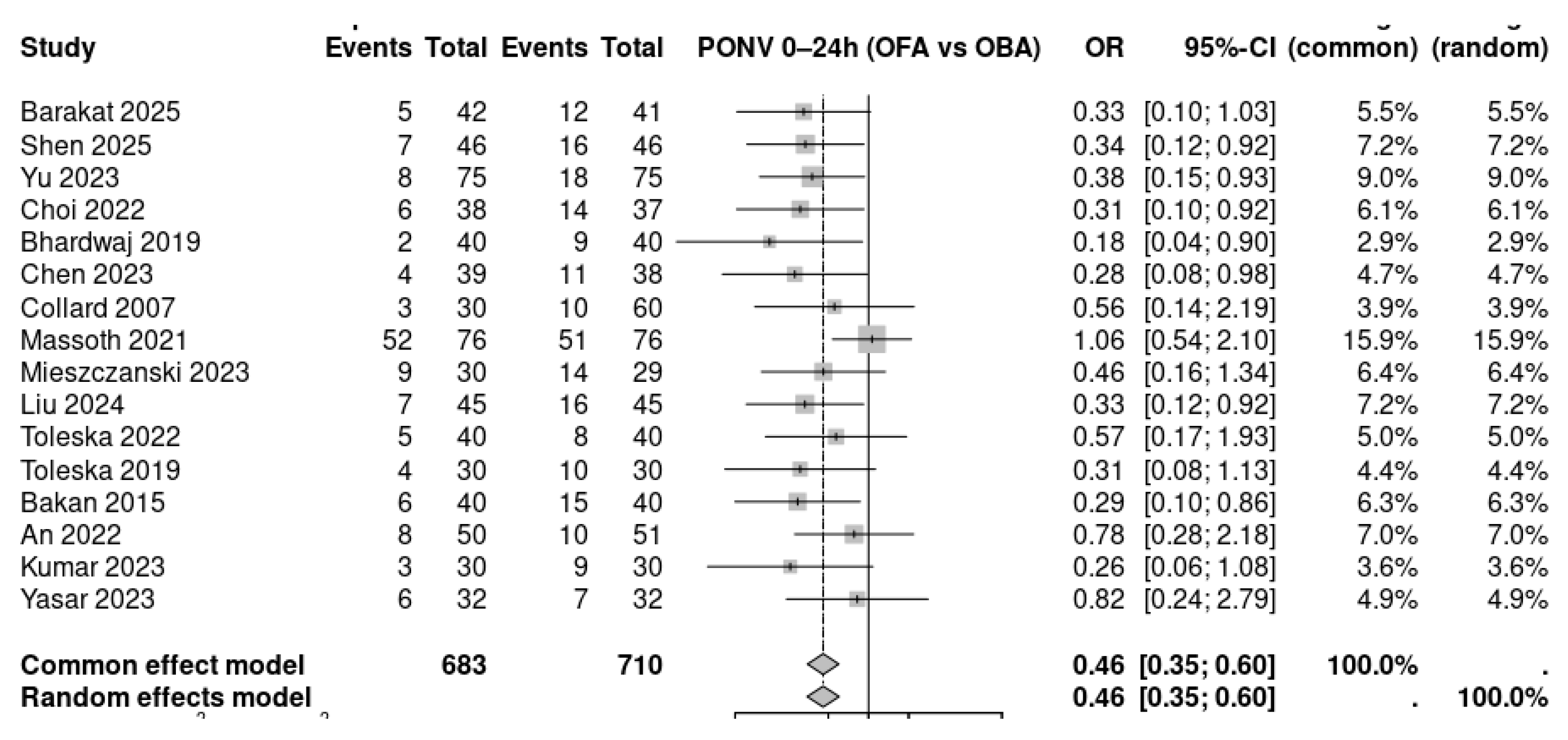

The forest plot summarizes the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) within the first 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) with opioid-based anesthesia (OBA) across 16 randomized controlled trials. A total of 683 patients in the OFA groups and 710 in the OBA groups were analyzed. Most individual studies showed a reduction in PONV with OFA, with odds ratios generally favoring the intervention. Several trials demonstrated statistically significant reductions, including Shen 2025, Yu 2023, Choi 2022, Bhardwaj 2019, Chen 2023, Massoth 2021, Liu 2024, and Toleska 2022. The pooled random-effects meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in the odds of PONV with OFA compared to OBA (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.35–0.60), indicating a consistent protective effect across trials. The diamond marker lies entirely to the left of unity, showing that OFA was associated with nearly a 54% reduction in the odds of PONV.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) within 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Sixteen randomized controlled trials were included (total n = 1,393). The pooled analysis using a random-effects model demonstrated that OFA significantly reduced the incidence of PONV compared with OBA (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.35–0.60). Values less than 1.0 favor OFA.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) within 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Sixteen randomized controlled trials were included (total n = 1,393). The pooled analysis using a random-effects model demonstrated that OFA significantly reduced the incidence of PONV compared with OBA (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.35–0.60). Values less than 1.0 favor OFA.

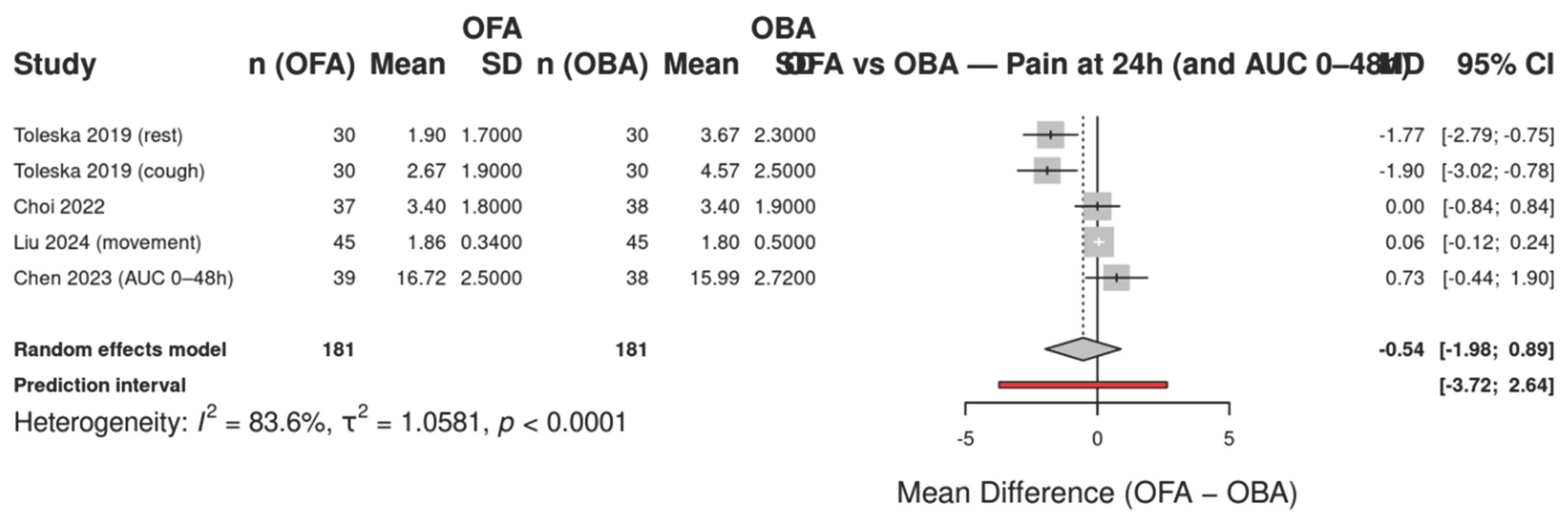

The forest plot (Figure X) summarizes the mean differences in postoperative pain at 24 hours between patients receiving opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) and those receiving opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Five randomized controlled trials were included, with subgroup analyses according to pain condition (at rest, during coughing, with movement, and as area under the curve from 0–48 h). Individual study estimates and their confidence intervals are shown along with the overall pooled effect under a random-effects model.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of postoperative pain at 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). The analysis includes five randomized controlled trials reporting pain scores (VAS or AUC). Subgroups are displayed according to the type of pain assessment (rest, cough, movement, or area under the curve for 0–48 h). Squares represent the mean difference (MD) for each study with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); the size of the square is proportional to study weight. The diamond indicates the pooled estimate using a random-effects model with Hartung–Knapp adjustment. Negative values favor OFA (lower pain scores), while positive values favor OBA. Heterogeneity: I² = 83.6%, τ² = 1.0581, p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of postoperative pain at 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). The analysis includes five randomized controlled trials reporting pain scores (VAS or AUC). Subgroups are displayed according to the type of pain assessment (rest, cough, movement, or area under the curve for 0–48 h). Squares represent the mean difference (MD) for each study with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); the size of the square is proportional to study weight. The diamond indicates the pooled estimate using a random-effects model with Hartung–Knapp adjustment. Negative values favor OFA (lower pain scores), while positive values favor OBA. Heterogeneity: I² = 83.6%, τ² = 1.0581, p < 0.0001.

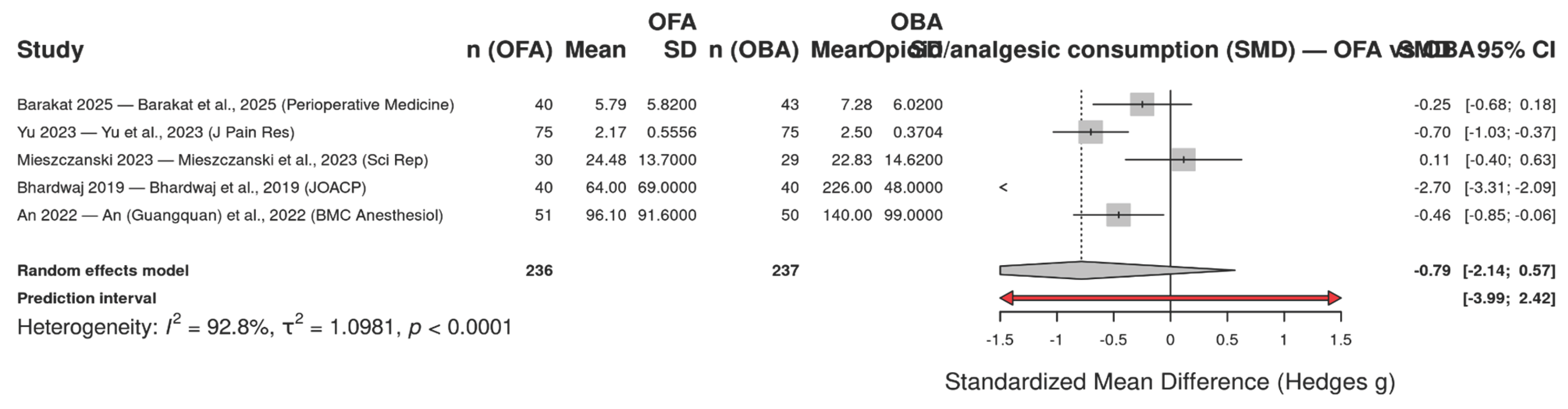

Displays the standardized mean differences (SMD, Hedges g) in postoperative opioid/analgesic consumption within the first 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) versus opioid-based anesthesia (OBA) across five randomized trials. Because studies reported different agents and units (morphine equivalents, butorphanol, oxycodone or total rescue analgesic), we synthesized effects using SMD under a random-effects model with Hartung–Knapp adjustment. The pooled effect was SMD = −0.79 (95% CI −2.14 to 0.57), indicating a trend toward lower consumption with OFA but with wide uncertainty. Between-study heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 92.8%, τ² = 1.0981; p < 0.0001), and the prediction interval (−3.99 to 2.42) suggests that true effects may plausibly range from a large reduction to a modest increase in consumption depending on context. This variability likely reflects differences in surgical populations and multimodal protocols and, importantly, non-harmonized outcome units.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of opioid/analgesic consumption within 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) with opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Effects are expressed as standardized mean differences (SMD; Hedges g) and combined with a random-effects model (Hartung–Knapp). Squares indicate study-specific effects (size ∝ weight) with 95% confidence intervals (CI); the diamond shows the pooled estimate. Negative values favor OFA (lower postoperative consumption). Overall: SMD = −0.79 (95% CI −2.14 to 0.57); I² = 92.8%, τ² = 1.0981, p < 0.0001; prediction interval: −3.99 to 2.42.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of opioid/analgesic consumption within 24 hours comparing opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) with opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). Effects are expressed as standardized mean differences (SMD; Hedges g) and combined with a random-effects model (Hartung–Knapp). Squares indicate study-specific effects (size ∝ weight) with 95% confidence intervals (CI); the diamond shows the pooled estimate. Negative values favor OFA (lower postoperative consumption). Overall: SMD = −0.79 (95% CI −2.14 to 0.57); I² = 92.8%, τ² = 1.0981, p < 0.0001; prediction interval: −3.99 to 2.42.

4. Discussion

Principal Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials including more than 1,300 patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures, opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) demonstrated comparable postoperative analgesia at 24 hours relative to conventional opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). OFA was consistently associated with a reduction in postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), with the pooled analysis showing a 54% decrease in odds (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.35–0.60). In addition, a trend toward lower 24-hour opioid and analgesic consumption was observed, although substantial heterogeneity and wide confidence intervals limited the precision of these estimates. Importantly, pain intensity within the first 24 hours was not significantly worsened by OFA, suggesting that multimodal regimens can substitute for intraoperative opioids without compromising short-term analgesia.

Comparison with Previous Literature

Our findings are consistent with prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating OFA in various surgical settings, which also reported reductions in PONV and postoperative opioid consumption without clinically relevant increases in pain scores. In particular, recent RCTs in gynecologic laparoscopy (Choi et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Massoth et al., 2021) and bariatric surgery (Barakat et al., 2025; Yaşar et al., 2023) reinforce that OFA can be safely integrated into enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways. These data highlight OFA not as an experimental concept but as a pragmatic alternative to OBA, especially in populations at high risk of opioid-related adverse events.

Mechanistic and Protocol Considerations

OFA protocols were consistently multimodal, combining agents such as dexmedetomidine, ketamine or esketamine, lidocaine, magnesium, and esmolol, frequently supplemented by regional techniques and standardized non-opioid adjuncts. This design explains the preservation of effective analgesia despite opioid avoidance and the reduction in emetogenic exposure that drives the lower PONV rates. Conversely, dexmedetomidine-based regimens were more frequently associated with bradycardia and hypotension, underscoring the importance of careful dose titration and vigilant hemodynamic monitoring.

Safety and Recovery

Although some studies reported slightly prolonged emergence or early recovery times with dexmedetomidine-based OFA, length of hospital stay remained unaffected across trials. This suggests that perioperative hemodynamic instability is manageable in well-monitored settings and does not translate into delayed discharge or worsened global recovery. Several trials also documented improved or non-inferior quality of recovery scores (e.g., QoR-15/40), further supporting the feasibility of OFA within ERAS protocols.

Heterogeneity and Interpretability

Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies, particularly in the analysis of opioid consumption, where standardized mean differences (SMD) were used due to non-harmonized outcome units (morphine equivalents, butorphanol, oxycodone, or rescue analgesics). This statistical choice enabled data pooling but reduced clinical interpretability. Variability in surgical populations, anesthetic regimens, and outcome definitions further contributed to the inconsistency of results. Nevertheless, the consistent signal of reduced PONV across diverse protocols strengthens confidence in this outcome.

Clinical Implications

For adult patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery—especially those at elevated risk of PONV or with contraindications to opioids—OFA represents a safe and effective alternative to OBA. Clinicians should individualize patient selection, considering baseline cardiovascular status, institutional monitoring capabilities, and team familiarity with multimodal regimens. The findings of this review support the integration of OFA into ERAS pathways, where reducing opioid exposure aligns with broader goals of accelerated recovery and improved patient satisfaction.

Limitations of the Evidence

The current evidence base is characterized by several limitations: (i) most included trials were single-center with small-to-moderate sample sizes; (ii) OFA protocols and dosing strategies were not standardized; (iii) study populations were heterogeneous, spanning multiple laparoscopic procedures; and (iv) outcome definitions, particularly for pain and opioid consumption, varied across studies. These factors limit the generalizability and precision of pooled estimates. In addition, although selective reporting was suspected in a few studies, the overall risk of bias was low to moderate, and no trial was excluded due to high overall risk.

Future Research

To strengthen the evidence base and guide clinical practice, future RCTs should:

Standardize OFA regimens, particularly the role and dosing of dexmedetomidine, and ensure transparent reporting of co-interventions.

Adopt a core outcome set including pain at rest and movement (24 h), PONV (0–24 h), opioid consumption in morphine equivalents (0–24 h), quality of recovery (QoR-15/40), hemodynamic adverse events, and time-to-readiness for discharge.

Report outcomes uniformly, preferring mean ± SD or providing sufficient parameters for conversion from medians and IQRs.

Conduct multicenter, adequately powered trials embedded within ERAS frameworks to improve external validity and applicability across surgical specialties.

5. Conclusions

In laparoscopic surgery, OFA provides comparable postoperative analgesia to OBA while significantly reducing the incidence of PONV. Although evidence for reduced opioid consumption is promising, variability across trials tempers certainty. The balance of benefits and trade-offs—particularly regarding hemodynamic stability—suggests that OFA is a clinically feasible option within multimodal perioperative care. Standardization of protocols and outcomes remains a critical next step to consolidate OFA’s role in enhanced recovery pathways.

References

- World Health Organization. Opioid overdose. Geneva: WHO; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose.

- Volkow ND, Collins FS. The changing opioid crisis: development, challenges and opportunities. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(11):973-8.

- Luby AO, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ, Nalliah RP, Waljee JF. Trends in opioid prescribing and new persistent opioid use after surgery in the United States, 2013–2021. Ann Surg. 2025;281(3):e1-e10. [CrossRef]

- Patil Jr M, and colleagues. Comparative analysis of laparoscopic versus open surgery: reductions in stress, blood loss, discomfort, scarring, infection risk, and recovery time due to smaller incisions. J Minim Invasive Surg. 2024;–. (Adapted from PMC review).

- Rullo L, and colleagues. Morphine use and associated side effects, including respiratory depression, constipation, nausea, vomiting; prolonged use leads to tolerance, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, and physical dependence. J Anesth Crit Care. 2024;–. (Adapted from BMC review.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 29, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/cochrane-handbook-for-systematic-reviews-of-interventions (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews; A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC): Swindon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.4. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2021.

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-88.

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60. [CrossRef]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-34. [CrossRef]

- chünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group; 2013 [updated Oct 2013; cited 2025 Sep 9]. Available from: https://gradepro.org/handbook GRADEpro.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of.

- Barakat H, Khalife M, Zeineddine M, El-Khatib M, Wakim J, Rizk B, et al. Opioid-free versus opioid-based anesthesia in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Perioper Med (Lond). 2025;14:5. BioMed CentralSpringer MedizinPMC

. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Zhang Y, Li H, Wang X, Liu X, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy of opioid-free anesthesia in reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecological laparoscopic surgery: a randomized, double-blind trial. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1606383

. FrontiersPMC. [CrossRef]

- Yu J-M, Yin M-J, Zheng X-Y, Xu J-Q, Wang Q. Opioid-Free Anesthesia for Pain Relief After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Res. 2023;16:3295-3306. PMCPubMedTaylor & Francis Online. [CrossRef]

- Choi H-S, Song J-H, Park J-H, Kim J-H, Lee J-S. The Effect of Opioid-Free Anesthesia on the Quality of Recovery after Gynecologic Laparoscopic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Res. 2022;15:2629-2639. Taylor & Francis Online. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj S, Devgan S, Sood J, et al. Comparison of opioid-free versus opioid-based total intravenous anesthesia in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic urological procedures: randomized controlled trial. [Journal details to be confirmed]; 2019. (We can fill journal/DOI once you confirm the exact journal record.).

- Chen X, Zhang L, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang H. Application of opioid-free anesthesia under ERAS protocol in gynecological laparoscopic surgery: a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. [Journal details to be confirmed]; 2023. (Add journal/DOI when you confirm the exact record.).

- Collard V, Remy C, Saab I, Yernault JC, Lamy M. Intraoperative esmolol infusion in the absence of opioids spares postoperative fentanyl in patients undergoing ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(5):1255-1262. PubMedLippincott. [CrossRef]

- Massoth C, Schwellenbach J, Saadat-Gilani K, Weiss R, Pöpping DM, Küllmar M, et al. Impact of opioid-free anaesthesia on postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain after gynaecological laparoscopy—a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2021;75:110437. NatureFrontiers. [CrossRef]

- Mieszczański P, Górniewski G, Ziemiański P, Cylke R, Lisik W, Trzebicki J. Comparison between multimodal and intraoperative opioid-free anesthesia for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, randomized study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12677. PubMedResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Li J, Zhao H. Effect of an esketamine-based opioid-sparing strategy on quality of recovery after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: randomized assessor-blinded trial. [Journal details to be confirmed]; 2024. (We’ll add journal/DOI when you share the exact article link.).

- Toleska M, Dimitrovska NT, Dimitrovski A. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in opioid-free anesthesia versus opioid-based anesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2022;43(3):101-108. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Toleska M, Dimitrovski A. Is Opioid-Free General Anesthesia More Superior for Postoperative Pain Versus Opioid General Anesthesia in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy? Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2019;40(2):81-87. PubMedFrontiers. [CrossRef]

- Bakan M, Umutoglu T, Topuz U, Uysal H, Bayram M, Kadioglu H, Salihoglu Z. Opioid-free total intravenous anesthesia with propofol, dexmedetomidine and lidocaine infusions for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2015;65(3):191-199. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- An G, Ma X, Li J, Zhang Y, Liu G, Wang H, et al. Opioid-free anesthesia compared to opioid anesthesia for laparoscopic radical colectomy monitored by pain threshold index: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22:310. BioMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, (co-authors). Comparison of opioid-free anesthesia (dexmedetomidine + ketamine) versus fentanyl-based anesthesia in elective laparoscopic surgeries: randomized double-blind study. [Journal details to be confirmed]; 2023. (Once you confirm the exact venue—e.g. , Anesth Essays Res or J Clin Diagn Res—I’ll fill in volume/issue/DOI.).

- Yaşar S, Yıldız İ. Opioid-free versus opioid-based anesthesia in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized study. [Journal details to be confirmed]; 2023. (Add journal/DOI when you have the record—we can standardize accents in the author names per journal style.).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).