1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Dual-chamber pacemakers are an established therapy for the management of bradyarrhythmias, particularly in patients with atrioventricular conduction disturbances [

1]. By preserving atrioventricular synchrony, these devices improve cardiac output, exercise tolerance, and quality of life [

2]. Modern systems are highly reliable, yet complications can still occur, often as a result of technical issues at the time of implantation [

3]. Small details, such as the proper placement of sutures or the use of protective sleeves, may appear minor during the procedure but can have long-term consequences on lead integrity. Mechanical stress, insulation damage, and conductor fracture are well-documented outcomes of such technical pitfalls, and while they may remain silent for months, they can ultimately manifest as sudden lead failure or premature device depletion [

4].

Another dimension in the management of patients with pacemakers is the detection of arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation (AF). Device interrogation has become a powerful diagnostic tool, capable not only of identifying technical dysfunctions but also of uncovering arrhythmic events that may otherwise remain asymptomatic [

5]. The recognition of AF is particularly relevant because of its established role as a major risk factor for ischemic stroke. Early detection of AF burden provides clinicians with an opportunity to initiate anticoagulation in accordance with international guidelines, thereby significantly reducing the risk of thromboembolic events [

6].

In situations where lead revision becomes necessary, venous access problems or anatomical limitations may preclude conventional transvenous reimplantation [

7]. Leadless pacemakers have emerged as a valuable alternative in this setting. Implanted directly into the right ventricle through femoral venous access, these devices bypass the need for leads and subcutaneous pockets, reducing the risks of infection, lead fracture, and hematoma [

8]. Furthermore, registry data support the safety of leadless implantation in patients on uninterrupted oral anticoagulation, a feature of particular relevance in those with recent thromboembolic stroke [

9].

Clinical Significance: The following case illustrates not only how technical pitfalls can result in unusually early device failure but also how a rare convergence of complications—stroke related to new atrial fibrillation, complete venous occlusion, and the need for uninterrupted anticoagulation—created an exceptionally complex therapeutic scenario. In this setting, leadless pacing provided the only safe and effective solution.

2. Case Presentation

A 78-year-old man with a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease underwent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation one year earlier for complete atrioventricular block. He presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of aphasia, right hemiparesis, and mouth angle deviation. Neurological examination confirmed a disabling focal deficit, with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 12. Urgent brain computed tomography (CT) excluded intracranial hemorrhage, and CT angiography revealed an occlusion of a left middle cerebral artery branch. The patient presented outside the therapeutic window for intravenous thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy. He was managed conservatively with acute stroke care and subsequently initiated on secondary prevention, including oral anticoagulation (Apixaban 5 mg twice daily) and optimization of cardiovascular risk factors.

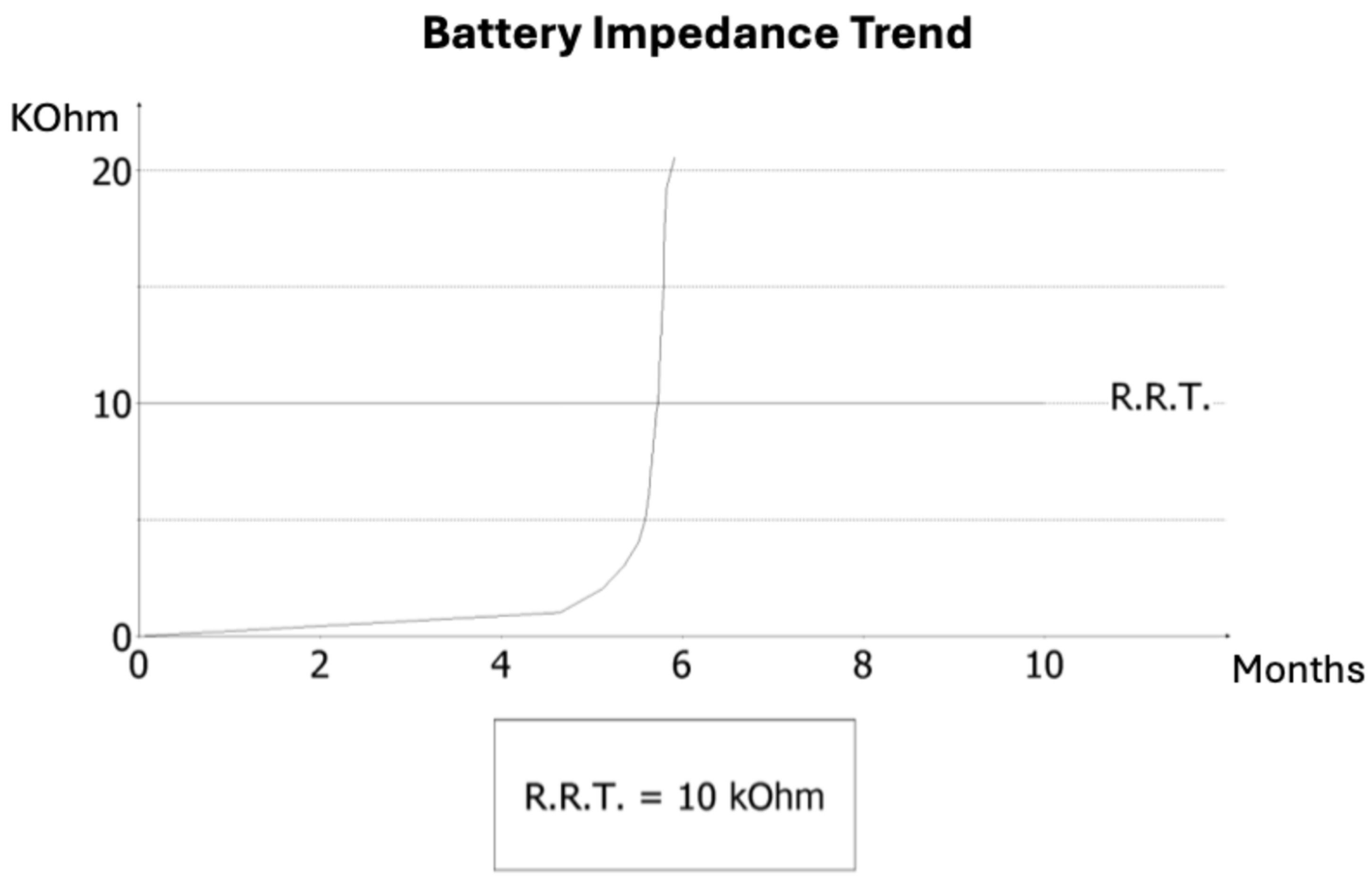

On admission, AF was documented for the first time. Pacemaker interrogation was performed to clarify arrhythmic burden and device status. Analysis revealed that AF had been persistent for several weeks prior to admission, temporally consistent with the occurrence of the cerebrovascular event. Additionally, diagnostic review identified striking electrical abnormalities: three months earlier, the ventricular lead impedance had dropped abruptly to 145 Ω, suggesting insulation breach or conductor damage, followed by a sharp rise to values above 30 kΩ, consistent with an open circuit (

Figure 1). This electrical instability accelerated battery consumption, and the device entered elective replacement indicator (ERI) mode within months of implantation — a highly unusual finding, as large registries report lead failure rates of <1% at one year. Notably, at previous follow-up visits, no signs of lead malfunction or abnormal impedance trends had been detected and, unlike implantable loop recorders, conventional dual-chamber pacemakers do not systematically provide continuous remote monitoring, and in this case no remote alerts were available.

Fluoroscopic examination demonstrated the pacemaker generator in situ with both atrial and ventricular leads displaying focal narrowings in the infraclavicular region (

Figure 2A). These findings were consistent with chronic mechanical damage, most likely related to suture fixation without protective sleeves at the time of implantation.

Conventional transvenous reimplantation was not feasible because of complete left subclavian vein occlusion (

Figure 2B) and arterial overlap. Extraction of the damaged leads was deemed high risk. Leadless pacemaker implantation represented the only feasible and safe alternative, given the presence of complete venous occlusion, the high hemorrhagic risk of contralateral reimplantation, and the prohibitive risk of extraction. A leadless pacemaker (Aveir, Abbott) was therefore selected as the optimal solution.

The procedure was performed via ultrasound-guided right femoral venous access without interruption of anticoagulation therapy. The presence of pre-existing intracardiac leads posed technical challenges, obstructing advancement of the delivery system (

Figure 2C) and requiring multiple repositioning attempts. After careful manipulation and sheath angulation adjustments, stable fixation of the leadless device was achieved on the apico-septal region of the right ventricle (

Figure 2D).

Final pacing parameters were optimal (threshold 0.5 V at 0.4 ms, R-wave 10 mV, impedance 680 Ω). No procedural complications occurred, and no bleeding events were observed despite uninterrupted anticoagulation.

The patient underwent neurological rehabilitation with partial functional recovery. At discharge, his modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was 2, indicating slight disability but preserved independence.

At one-month follow-up, the leadless device demonstrated stable function with excellent electrical performance, and the patient continued to show neurological improvement.

3. Discussion

This case highlights several clinically relevant considerations. Beyond the unusually early failure of a dual-chamber system, what makes this report distinctive is the convergence of multiple high-risk factors: ischemic stroke linked to new atrial fibrillation, complete venous occlusion, and the requirement for uninterrupted anticoagulation. It was this clustering of challenges, rather than any single factor, that defined the therapeutic complexity and shaped the management strategy. The most striking aspect is the abrupt failure of a dual-chamber system only one year after implantation, a timing that is exceptionally early. In large national registries, lead failure rates during the first year remain well below 1%, with most malfunctions occurring after several years [

10,

11]. This strongly suggests a preventable technical cause rather than intrinsic device defect.

The fluoroscopic finding of focal narrowings along the lead trajectory supports the hypothesis of suture-related compression injury. Such injury is avoidable with meticulous implant technique and routine use of protective sleeves [

12,

13]. In their absence, chronic mechanical stress may silently progress for months until manifesting with abrupt impedance shifts, pacing failure, and accelerated battery depletion. This case therefore reinforces the importance of careful handling of transvenous leads at the time of implant.

Another central message is the value of systematic device interrogation. In this patient, pacemaker checks did not merely reveal technical malfunction but also uncovered an elevated arrhythmic burden and several weeks of persistent atrial fibrillation preceding the ischemic stroke. Interrogation thus provided crucial diagnostic information, establishing an etiological link between arrhythmia and the neurological event [

14]. This highlights how device data can guide stroke prevention strategies, especially in patients with elevated CHA₂DS₂-VASc scores, for whom guideline-directed anticoagulation is essential.

In our case, the therapeutic pathway was also shaped by anatomic and procedural challenges. Conventional transvenous reimplantation was not feasible because of venous occlusion and arterial overlap, while extraction was judged high risk [

15]. Leadless pacing provided a feasible alternative [

16]. Despite technical difficulties from intracardiac obstacles, the Aveir device was successfully implanted, restoring ventricular pacing with stable parameters.

Finally, the use of femoral venous access offered an important advantage in this anticoagulated patient [

17]. Unlike subclavian or axillary approaches, the femoral route avoids creation of a subcutaneous pocket and reduces the risk of clinically significant bleeding or hematoma. Registry data confirm the safety of uninterrupted anticoagulation during leadless implantation, making this strategy particularly suitable for patients with recent ischemic stroke in whom strict maintenance of anticoagulation is mandatory [

18,

19]. At our centre we perform femoral haemostasis by means of a figure-of-eight suture, closing the suture point inside a 3-way tap. This technique allows constant compression at the access level for 24 hours, thereby minimizing the risk of hematoma formation. Combined with the absence of a subcutaneous pocket, this approach reduces bleeding complications and allows safe continuation of oral anticoagulation.

It should be noted that this report reflects a single patient with short-term follow-up, which limits generalizability. While device interrogation strongly suggested a temporal association between atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke, causality cannot be definitively established. Moreover, the absence of remote monitoring restricted continuous arrhythmia detection and may have delayed recognition of lead malfunction.

4. Conclusions

What makes this case particularly noteworthy is the simultaneous occurrence of multiple adverse factors, rarely reported together in the literature. Furthermore, it underscores that even minor technical oversights at pacemaker implantation may result in serious complications within an unusually short timeframe. Device interrogation proved invaluable, simultaneously identifying lead malfunction and clarifying arrhythmic burden, thereby informing both technical management and stroke prevention. Leadless pacing via femoral access emerged as a safe and effective rescue strategy in a patient requiring uninterrupted anticoagulation. As the population of anticoagulated and anatomically complex patients continues to grow, leadless systems are likely to play an increasingly central role in contemporary pacing practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fu.Cac.; methodology, Fu.Cac. and M.V.; software, Fl.Cas.; validation, Fu.Cac. and M.V..; formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, Fu.Cac. and M.V.; resources, Fl.Cas.; data curation, Fu.Cac. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Fu.Cac.; writing—review and editing, Fu.Cac.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, M.V.; project administration, Fu.Cac. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| NIHSS |

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| ERI |

Elective Replacement Indicator |

| RRT |

Recommended Replacement Time |

| mRS |

Modified Rankin Scale |

References

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM, Barrabés JA, Boriani G, Braunschweig F, Brignole M, Burri H, Coats AJS, Deharo JC, Delgado V, Diller GP, Israel CW, Keren A, Knops RE, Kotecha D, Leclercq C, Merkely B, Starck C, Thylén I, Tolosana JM; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427-3520. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2022 May 1;43(17):1651. PMID: 34455430. [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, F.M.; Schoenfeld, M.H.; Barrett, C.; Edgerton, J.R.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Gold, M.R.; Goldschlager, N.F.; Hamilton, R.M.; Joglar, J.A.; Kim, R.J.; et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay. JACC 2019, 74, e51–e156. [CrossRef]

- Kirkfeldt, R.E.; Johansen, J.B.; Nohr, E.A.; Jørgensen, O.D.; Nielsen, J.C. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur. Hear. J. 2013, 35, 1186–1194. [CrossRef]

- Schnorr, B.; Kelsch, B.; Cremers, B.; Clever, Y.P.; Speck, U.; Scheller, B. Contemporary issues in cardiac pacing.. 2010, 58, 677–90.

- Witkowski, M.; Bissinger, A.; Grycewicz, T.; Lubinski, A. Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation in patients with atrial fibrillation and implanted pacemaker. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 583–588. [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Hear. J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.-Y.; Kwong, N.-P.; Cheong, A.-P. Venous access and long-term pacemaker lead failure: comparing contrast-guided axillary vein puncture with subclavian puncture and cephalic cutdown. Eur. 2016, 19, euw147–1197. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Meng, L.; Lin, H.; Xu, W.; Guo, H.; Peng, F. Systematic review of leadless pacemaker. Acta Cardiol. 2023, 79, 284–294. [CrossRef]

- Mitacchione, G.; Schiavone, M.; Gasperetti, A.; Arabia, G.; Breitenstein, A.; Cerini, M.; Palmisano, P.; Montemerlo, E.; Ziacchi, M.; Gulletta, S.; et al. Outcomes of leadless pacemaker implantation following transvenous lead extraction in high-volume referral centers: Real-world data from a large international registry. Hear. Rhythm. 2022, 20, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Sterns, L.D. Pacemaker lead surveillance and failure: Is there a signal in the noise?. Hear. Rhythm. 2018, 16, 579–580. [CrossRef]

- Haeberlin, A.; Anwander, M.-T.; Kueffer, T.; Tholl, M.; Baldinger, S.; Servatius, H.; Lam, A.; Franzeck, F.; Asatryan, B.; Zurbuchen, A.; et al. Unexpected high failure rate of a specific MicroPort/LivaNova/Sorin pacing lead. Hear. Rhythm. 2021, 18, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Kumar, V.; Talwar, K.K. Traumatic Fracture of Pacemaker Lead by Suture Transfixation to Pectoral Muscle. 2018, 30, E156–E156.

- Rezazadeh, S.; Wang, S.; Rizkallah, J. Evaluation of common suturing techniques to secure implantable cardiac electronic device leads: Which strategy best reduces the lead dislodgement risk?. Can. J. Surg. 2019, 62, E10–E13. [CrossRef]

- Al-Gibbawi, M.; Ayinde, H.O.; Bhatia, N.K.; El-Chami, M.F.; Westerman, S.B.; Leon, A.R.; Shah, A.D.; Patel, A.M.; De Lurgio, D.B.; Tompkins, C.M.; et al. Relationship between device-detected burden and duration of atrial fibrillation and risk of ischemic stroke. Hear. Rhythm. 2020, 18, 338–346. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ze, F.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Duan, J.; Guo, F.; Yuan, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, J. Prevalence of venous occlusion in patients referred for lead extraction: implications for tool selection. Eur. 2014, 16, 1795–1799. [CrossRef]

- Darlington, D.; Brown, P.; Carvalho, V.; Bourne, H.; Mayer, J.; Jones, N.; Walker, V.; Siddiqui, S.; Patwala, A.; Kwok, C.S. Efficacy and safety of leadless pacemaker: A systematic review, pooled analysis and meta-analysis. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol. J. 2021, 22, 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Jelisejevas, J.; Breitenstein, A.; Hofer, D.; Winnik, S.; Steffel, J.; Saguner, A.M. Left femoral venous access for leadless pacemaker implantation: patient characteristics and outcomes. Eur. 2021, 23, 1456–1461. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.F.; Carvalho, M.M.; Adão, L.; Nunes, J.P. Clinical outcomes of leadless pacemaker: a systematic review. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2021, 69, 346–357. [CrossRef]

- Kadado, A.J.; Chalhoub, F. Periprocedural anticoagulation therapy in patients undergoing micra leadless pacemaker implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 371, 221–225. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).