1. Introduction

The overall number of adult congenital heart disease (CHD) patients continues to rise because of significant improvement in medical and surgical approaches over the past decades [1]. More than 90% of newborns diagnosed with congenital heart disease survive into adulthood [2]. A subset of these patients receive cardiac implantable devices in their childhood [3, 4]. CIED complications leading to transvenous pacemaker (PM) / implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) lead extraction (TLE) are not uncommon in this patient population [5, 6]. Lead extraction in CHD patients can be technically challenging due to their complex vascular and cardiac anatomy. Inadvertent patch or baffle injuries may have hemodynamic relevance and electrode remnants may cause thromboembolic complications in CHD patients [7]. Reaching procedural success and avoiding complications is therefore of paramount importance.

Over the past years, lead extraction centres gained significant experience in using mechanical-powered sheaths [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Available data regarding the outcome and complexity of lead extractions using only rotational-mechanical dilator as powered sheath in CHD patients is scarce [13]. The aim of this study was to report the outcome and complexity of TLEs in CHD patients. We compared the success rate, complication rate, mortality rate and complexity rate of extractions performed in CHD patients with those of extractions performed in non-CHD patients. We hypothesized that TLE in CHD patients is a safe and effective procedure; the success rate, complication rate and mortality rate of TLEs performed in CHD patients may be similar to TLEs done in non-CHD patients. Our further hypothesis was that advanced extraction technique may be more often necessary in TLEs performed in CHD patients compared to TLEs done in non-CHD patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

In our retrospective study, we included consecutive patients undergoing transvenous lead extraction procedure in a tertiary referral centre. All TLEs were performed between January 2014 and December 2023 by three expert electrophysiologists at the Gottsegen Gyorgy National Cardiovascular Centre, Budapest, Hungary.

2.2. Primary Hypothesis and Study Design

The primary hypothesis of this study was that the success rate, complication rate and mortality rate of percutaneous lead extractions performed in CHD patients are comparable to the outcome of TLEs done in non-CHD patients. We further hypothesized that due to their younger age and unique anatomic characteristics, CHD patients require more advanced extraction techniques than non-CHD patients. In our study, we first defined the success rate, complication rate, mortality rate and procedural complexity rate of TLEs in CHD patients, we then compared these outcome data with those of TLEs done in non-CHD patients who had undergone percutaneous lead extraction during the same time period.

2.3. Data Collection

Data from hospital records and chest X-ray images were collected in a database retrospectively. The following demographic data were collected: age, sex, comorbidities. Indication for lead extraction, the types of implantable cardiac devices and lead characteristics such as lead implant duration, the number of leads present, the number of leads treated per patient, the number of extracted ICD leads and the number of extracted abandoned leads were collected. Methodological data on lead extraction, such as the use of powered sheath and procedure duration were also collected. Outcome was characterized by procedural and clinical success rate, procedural complication rate, 30-day mortality rate and complexity rate of percutaneous lead extractions. The following procedural complications were collected: procedure-related death, cardiac avulsion, vascular laceration, valve injury, pericardial effusion, haemothorax, pulmonary embolism, heart failure requiring intervention, haematoma requiring evacuation and intra-or perioperative blood loss requiring blood transfusion.

2.4. Consent and ethics

The Hungarian national medical ethics committee (the Scientic and Research Ethics Committee of the Scientic Council for Health "ETT TUKEB") approved the data collection for this study (CHD-01). The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Definitions

Percutaneous lead extraction, procedural efficacy, complications were defined according to 2018 EHRA guidelines [14]. Complete procedural success was defined as the removal of all targeted leads and material, with the absence of any permanently disabling complication or procedure-related death.[14]. Clinical procedural success was defined as the retention of a small portion of a lead that does not negatively impact the outcome goals of the procedure [14]. A lead extraction was considered simple if only simple manual traction or locking stylet was required, and defined complex if rotational-mechanical sheath or femoral snare were utilized. Indications for TLEs were categorized as infection (pocket infection, infective endocarditis) or non-infective (lead failure, dislocation or system upgrade) [15].

2.6. Extraction Procedures

TLEs were performed either in the electrophysiology laboratory or a cardiac surgical operating room equipped with fluoroscopy system. Local anaesthesia or general anaesthesia was applied based on heart team decision. Standby cardiac surgery was available during all TLE procedures. Continuous intraoperative transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) was added in TLEs when a difficult procedure was anticipated.

First, incision was made at the site of the pulse generator, leads were disconnected, then, dissection was performed along the leads to the suture sleeves. Sleeves were removed, and leads were cut. All electrodes were removed using a standard stepwise approach: first, a straight stylet and simple manual traction was applied, then, a locking stylet was used, last, a mechanical-powered sheath (Evolution, Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA or TightRail, Philips Healthcare) was used, if necessary. Rotational-mechanical sheath sizes included 9-11-or 13 -Fr sheaths. In case of lead fracture, femoral approach by applying snare technique (Needle’s Eye’s snare (Cook Medical Inc, Bloomington, IN, USA) was also used. Tandem femoral approach was not routinely used during the extraction process. In patients without infective indication, device re-implantation was performed at the same procedure. In patients with infective indication, device re-implantation was deferred to an infection- free time point.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for normally distributed continuous variables. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were computed for continuous variables with non-normal distribution. Categorical data were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. To compare baseline and procedural characteristics between the patient groups, we used independent t-test. To compare not normally distributed data between patient groups, we used Mann-Whitney U-test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JASP software version 0.16.4 (Intel).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Our retrospective database of 175 TLEs consisted of 13 extractions performed in 11 CHD patients (two patients underwent repeated TLEs years after the index procedure) and 162 extractions performed in non-CHD patients.

Baseline patient demographics are presented in

Table 1.

Patients with an ejection fraction of <50% were present in 23% of CHD patients and in 60% of non-CHD patients; p=0,06. Among heart failure patients, there was no significant difference between the two patient groups concerning heart failure treatment: beta-blocker therapy was taken in 66% of CHD patients and 84% of non-CHD patients; p=0,418, ACEI/ARB/ARNI therapy was present in 66% of CHD patients and 74% of non-CHD patients; p=0,752 and MRA therapy was taken regularly in 33% of CHD patients and 62% of non-CHD patients; p=0,314.

Prior cardiac surgery was present in 100% of CHD patients as compared with 13% of non-CHD patients; p<0,01. Prosthetic heart valve was present in a significantly greater number of CHD patients (30,7%) compared to non-CHD patients (7,3%); p=0,005. Diabetic patients were present in a similar proportion in both groups (7,7% of CHD patients and 27,75% of non-CHD patients; p=0,113.

A summary of the underlying heart disease of CHD patients is shown in

Table 1.

Detailed demographics of the individual CHD extractions is given is

Table 2.

Cardiac abnormalities were mostly moderate as classified by the European Society of Cardiology CHD complexity scheme [16]. In five cases, the underlying heart disease was severe, and in one case, the cardiac abnormality was mild. The most common underlying cardiac abnormality was coarctation of the aorta (n:4). All of these aortic coarctations were repaired with an end-to end anastomosis in childhood, one patient subsequently underwent a Bentall procedure at early adulthood. Tetralogy of Fallot (n:3) with complete surgical reconstruction including pulmonary homograft implantation was the second most common underlying heart disease, followed by d-transposition of the great arteries all of whom had previously undergone Senning operation (n:3). Two patients had double outlet right ventricle palliated surgically with a Fontan circulation and one patient had ventricular septal defect repaired through patch closure. In seven cases, an additional cardiac abnormality was present, among which atrial or ventricular septal defect was the most common pathology. In two cases, incomplete AV septal defect and cleft mitral valve was present and one patient had a persistent left superior vena cava. Extracardiac abnormality was present in one case, where coarctation of the aorta was accompanied by Turner syndrome.

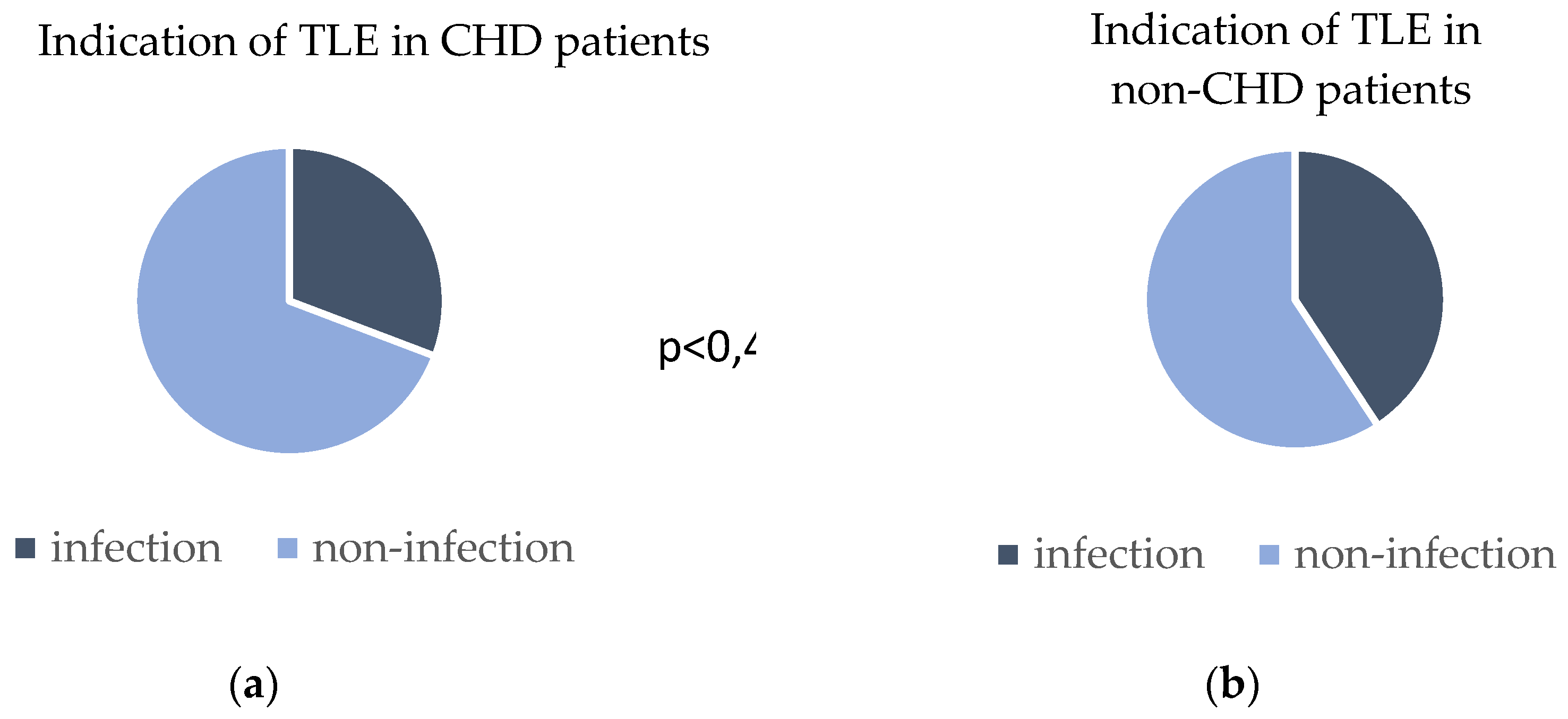

Patient indications for lead extractions were system infection in 31% of CHD patients and 41% of non-CHD patients; p=0,48. The indications for TLE are provided in

Figure 1.

3.2. Device Type and Lead Characteristics

Device types present at the time of extraction and lead characteristics are shown in

Table 3.

Overall, 264 leads were extracted, 22 leads were removed from CHD patients and 242 leads were extracted from non-CHD patients. Median lead dwelling time was higher for CHD patients (8 years) than for non-CHD patients (4 years); p<0,01. The majority of CHD patients and non-CHD patients had 2 leads present at the time of extraction (61% vs 35%; p=0,448). One lead was extracted in most CHD (54%) and most non-CHD patients (67%); p=0,594. The rate of ICD lead extraction was numerically lower in CHD patients compared to non-CHD patients, however, this difference was statistically not significant (15% vs 40%; p=0,07). Abandoned leads were extracted more often from CHD patients (23%) than from non-CHD patients (6%); p= 0,025.

3.3. TLE outcomes in CHD patients: success rate, complication rate, survival and rate of advanced technique use

Complete procedural success rate in CHD patients was 92%, clinical procedural success rate among CHD was 100%. Neither minor nor major procedural complications were observed in the CHD group. Procedure related mortality was 0% in CHD patients. 30-day mortality rate was 8,3% among CHD patients: one patient was lost to follow-up, eleven out of 12 (91,7%) patients survived, one patient (8,3%) died of septic shock following the procedure. Percutaneous extractions in CHD patients required the use of rotational-mechanical sheaths and/or femoral snare in 61% of cases. Procedural outcome data are summarized in

Table 3.

3.4. Comparison of TLE Outcomes in CHD Patients with Non-CHD Patients

There was no difference between CHD patients and non-CHD patients in procedural success rate (92% vs 87%; p=0,581) and clinical success rate (100% vs 91%; p=0,269). The two patient groups did not differ in their procedural complication rate, either (0% vs 11%; p=0,191).

Procedure related mortality was 0% in both groups. 30-day mortality rate was not different between CHD (8,3%) and non-CHD patients (6,6%); p= 0,825, the cause of death was septic shock for all patients.

There was no difference in the utilized TLE techniques. Simple manual traction was used in 30% of CHD extractions and in 48% of non-CHD extractions; p=0,21, simple manual traction had an overall clinical success rate of 97,5% and an overall procedural success rate of 96,3%. Locking-stylet and manual traction was applied in 8,3% of CHD extractions and in 11% of non-CHD extractions; p= 0,641. Complex technique was necessary in 61% (8 of 13) of CHD extractions, and in 38% (63 of 162) of non-CHD extractions; p= 0,11. The distribution of Evolution and TightRail use was similar in the two patient groups: Evolution powered sheaths were used in 23% of CHD extractions and 10% of non-CHD extractions, TightRail powered sheaths were applied in 15% of CHD extractions and 22% of non-CHD extractions; p=0,191. However, femoral snare was more often necessary as bail-out technique in CHD patients (23%) compared to non-CHD patients (4,9%); p=0,01.

4. Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that when using a stepwise approach with mechanical powered sheath as the last step, percutaneous lead extraction in surgically corrected CHD patients can be accomplished with high efficacy and safety comparable with TLEs performed in non-CHD patients.

4.1. TLE in Surgically Repaired CHD Patients

Surgically corrected congenital heart disease patients represent a unique patient population in that they pose special technical challenges to TLEs. Difficulties inherent in the TLEs of surgically repaired CHD patients are the younger age of the patients, longer lead implant duration and cardiac abnormalities arising not only from congenital malformations but from the postoperative condition, as well. Previous reports have shown that patients with greater anatomic complexity have an increased risk of developing lead complication, thus transvenous PM/ICD lead extraction becomes a necessity in a greater proportion of postoperative CHD patients [17]. Therefore, understanding the outcome of percutaneous lead extraction in this special postoperative patient group is essential.

Previous reports of lead extractions in CHD patients focusing on a mixed population of CHD patients with and without previous surgical correction have shown that percutaneous lead extraction is effective and relatively safe in this patient group [18]. However, there is limited data on the safety and efficacy of TLEs performed in surgically corrected CHD patients. Our study where all CHD patients were surgically reconstructed, suggests that despite their unique anatomic characteristics, percutaneous lead extraction can be performed safely and effectively in this patient group.

4.2. Use of Mechanical- Powered Sheaths in CHD Patients: Efficacy

Concerning the technique of TLEs in CHD patients, previous studies have shown that laser- powered lead extractions [18, 19, 20, 21] and radiofrequency-powered sheath use [22] have a clinical success rate of 74%-94%. Mechanical powered sheath use has a well- established efficacy profile, and over the past decade, extraction centres have gained significant experience in using this technique of percutaneous lead extraction [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. However, little is known about the efficacy of mechanical-powered sheath use in surgically corrected CHD patients. In our study, all extractions were performed using mechanical-powered sheaths as advanced extraction tools. We report that in surgically corrected CHD patients, lead extraction had a clinical success rate of 100%, an efficacy rate that exceeds the previously reported efficacy rate of laser -or radiofrequency powered extractions in CHD patients. The superior performance of mechanical powered sheath use in CHD patients compared to laser- or radiofrequency-powered extractions might be explained by the observation that younger patients -such as CHD patients- form excessive calcific adhesions around intracardiac leads [23], and this calcific mass might be better destroyed by rotational-mechanical TLE than laser-powered sheaths.

4.3. Use of Mechanical-Powered Sheaths in CHD Patients: Safety

Former reports on complication rate of laser-powered TLE in CHD patients have shown a complication rate of 5,5-17% [13, 19, 21, 24]. In the current report, despite the difficulties inherent in TLEs of CHD patients, no procedural complications occurred during TLE of surgically corrected CHD patients. We presume that previous cardiac surgery had a protective role in reducing the risk of pericardial effusion due to postoperative pericardial adhesion.

4.4. Abandoned Leads

Defining the risk of the extraction of abandoned leads is particularly important in surgically repaired CHD patients. Previous studies have shown that the extraction of abandoned leads increases complication rate and decreases the success rate of TLEs [8, 25]. However, abandonment has also been shown to carry the risk of infection, future lead-to-lead interaction, tricuspid regurgitation and venous occlusion [26, 27], an issue which is of paramount importance in CHD patients repaired with baffles. It is well known that the policy to abandon a non-functioning lead often increases the difficulty of a future extraction [28], thus the benefit of extracting a non-functioning lead could be much greater in younger patients. In our single-centre study, where abandoned leads were present in 23% of CHD patients, the extraction of abandoned leads did not increase the complication rate of TLEs. According to current guidelines, the extraction of non-functional leads that have no negative arrhythmic or thromboembolic impact is a class IIa indication or -when the aim is to facilitate magnetic resonance imaging- a class IIb indication [29]. In everyday practice, this means that in such situations, a shared decision-making process about extraction is advised. Our finding that abandoned leads can be safely extracted in CHD patients helps to refine such shared decisions, and argues for the extraction of non-functioning leads in young CHD patients after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

4.5. Study Limitations

The relatively small sample size of the CHD group is the most important limitation of our analysis; however, it should be noted that surgically repaired CHD patients undergoing percutaneous lead extraction is a unique patient population. The study represents a single-centre experience, however, as our lead extraction centre is the only centre dedicated to CHD percutaneous extractions in our country, it was not possible to include patients from other centres. Continuous intraoperative TEE or ICE monitoring was performed in only 10,9% of TLEs, which is another limitation of our study [30]. Procedure duration was collected as skin-to skin time, which indicated the duration of the extraction procedure itself only in infectious indications, where a new electrode was not simultaneously implanted. Although procedure duration is a relevant issue, for the above reason, it was not statistically interpretable

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in surgically corrected CHD patients percutaneous lead extraction can be performed safely and effectively, comparable to extractions done in patients without CHD. Complex technique was not required more often in CHD patients than it is generally mandatory in non-CHD patients. Our findings suggest that the approach to remove non-functioning leads seems justified even in CHD patients after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.Cs. and T. Sz...; methodology: A. Cs and T.Sz.T..; software: R.G.; validation: R.G.; formal analysis: R.G.; investigation: A.Cs.; resources: A.K., Cs. .F. and Z. S..; writing—original draft preparation: A. Cs and R. G; writing—review and editing: M.V. and T.Sz..; supervision: T.Sz. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Hungarian national medical ethics committee (the Scientic and Research Ethics Committee of the Scientic Council for Health "ETT TUKEB") (protocol code: CHD-01)

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the restrospective nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Cs.Foldesi received institutional grants from Medtronic Inc., consulting fees from Medtronic Inc. and Biotronik Hungária Kft., payment or honoraria for lectures from Johnson and Johnson Co., Abbott Laboratories, Novartis Hungária Kft. and Boehringer Ingelheim RCV GmbH Co. M.Vamos reports educational activity and advisory relationship with Biotronik and educational activity on behalf of Boston Scientific/ Twinmed, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. T. Szili-Török received institutional grants from Biotronik, Abbott NL, Biosense Webster, Acutus Medical Inc., Stereotaxis, Catheter Precision, and had consultancy/advisory/speakers contract for product development with Biotronik, Ablacon Inc., Acutus Medical Inc., and Stereotaxis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHD |

Congenital heart disease |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator |

| PM |

Pacemaker |

| TLE |

Transvenous lead extraction |

References

- van der Linde; Konings EE; Slager MA et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 58, 2241-7.

- Khairy P; Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, Abrahamowicz M, Pilote L, Marelli AJ. Changing mortality in congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 56, 1149-57.

- Khairy P, Van Hare GF, Balaji S et al. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the recognition and management of arrhyth mias in adult congenital heart disease: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology devel oped in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Can J Cardiol 2014, 30, e1-e63.

- Koyak Z, Harris L, de Groot JR et al. Sudden cardiac death in adult congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2012, 126, 1944–54.

- Czosek RJ, Meganathan K, Anderson JB, Knilans TK, Marino BS, Heaton PC. Cardiac rhythm devices in the pediatric population: utilization and complications. Heart Rhythm 2012, 9, 199-208.

- Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL et al. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 1085-104.

- Khairy P, Landzberg MJ, Gatzoulis MA et al. Epicardial Versus Endocardial pacing and Thromboembolic events Investigators. Transvenous pacing leads and systemic thromboemboli in patients with intracardiac shunts: a multicenter study. Circulation 2006, 113, 2391-7.

- Bongiorni MG, Kennergren C, Butter C et al. The European Lead Extraction ConTRolled (ELECTRa) study: a European Heart.

- Rhythm Association (EHRA) Registry of Transvenous Lead Extraction Outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2017, 3, 2995–3005.

- Starck CT, Gonzalez E, Al-Razzo O et al. Results of the Patient-Related Outcomes of Mechanical lead Extraction Techniques (PROMET) study: a multicentre retrospective study on advanced mechanical lead extraction techniques. Europace 2020, 22, 1103-1110.

- Sharma S, Lee BK, Garg A et al. Performance and outcomes of transvenous rotational lead extraction: Results from a prospective, monitored, international clinical study. Heart Rhythm O2 2021, 2, 113-121.

- Zsigmond EJ, Saghy L, Benak A et al. A head-to-head comparison of laser vs. powered mechanical sheaths as first choice and second line extraction tools. Europace 2023, 25, 591-599.

- Yap SC, Bhagwandien RE, Theuns DAMJ et al. Efficacy and safety of transvenous lead extraction using a liberal combined superior and femoral approach. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021, 62, 239-248.

- Pham TDN, Cecchin F, O'Leary E et al. Lead Extraction at a Pediatric/Congenital Heart Disease Center: The Importance of Patient Age at Implant. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 343-353.

- Bongiorni MG, Burri H, Deharo JC et al. 2018 EHRA expert consensus statement on lead extraction: recommendations on definitions, endpoints, research trial design, and data collection requirements for clinical scientific studies and registries: endorsed by APHRS/HRS/LAHRS. Europace.2018, 20, 1217.

- Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID), and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 2012-2032.

- Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV et al..2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 563-645.

- Albertini L, Kawada S, Nair K, Harris L. Incidence and Clinical Predictors of Early and Late Complications of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. Can J Cardiol. 2023, 39, 236-245.

- Fender EA, Killu AM, Cannon BC et al. Lead extraction outcomes in patients with congenital heart disease. Europace 2017, 19, 441-446.

- Khairy P, Roux JF, Dubuc M et al. Laser lead extraction in adult congenital heart disease. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007, 18, 507–11.

- McCanta AC, Kong MH, Carboni MP, Greenfield RA, Hranitzky PM, Kanter RJ. Laser lead extraction in congenital heart disease: a case-controlled study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013, 36, 372-80.

- Gourraud JB, Chaix MA, Shohoudi A et al. Transvenous Lead Extraction in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Insights From a 20-Year Single-Center Experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018, 11,:e005409.

- Cecchin F, Atallah J, Walsh EP, Triedman JK, Alexander ME, Berul CI. Lead extraction in pediatric and congenital heart disease patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010, 3, 437-44.

- Esposito M, Kennergren C, Holmström N, Nilsson S, Eckerdal J, Thomsen P. Morphologic and immunohistochemical observations of tissues surrounding retrieved transvenous pacemaker leads. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002; 63, :548-58.

- Moak JP, Freedenberg V, Ramwell C, Skeete A. Effectiveness of excimer laser- assisted pacing and ICD lead extraction in children and young adults. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 200, 29, 461-6.

- Hussein AA, Tarakji KG, Martin DO et al. Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections: Added Complexity and Suboptimal Outcomes With Previously Abandoned Leads. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017, 3, 1-9.

- Kolodzinska K, Kutarski A, Grabowski M, Jarzyna I, Małecka B, Opolski G. Abrasions of the outer silicone insulation of endocardial leads in their intracardiac part: a new mechanism of lead-dependent endocarditis. Europace 2012, 14, 903-10.

- Issa Z. An approach to transvenous lead extraction in patients with malfunctioning or superfluous leads EP LabDigest 2022.

- Segreti L, Rinaldi CA, Claridge S et al. Procedural outcomes associated with transvenous lead extraction in patients with abandoned leads: an ESC-EHRA ELECTRa (European Lead Extraction ConTRolled) Registry Sub-Analysis. Europace 2019, 21, 645-654.

- Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Wilkoff BL et al. 2017 HRS expert consensus statement on cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead management and extraction. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, :e503-e551.

- Strachinaru M, Kievit CM, Yap SC, Hirsch A, Geleijnse ML, Szili-Torok T. Multiplane/3D transesophageal echocardiography monitoring to improve the safety and outcome of complex transvenous lead extractions. Echocardiography. 2019, 36,:980-986.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).