1. Introduction

Persistent foramen ovale (PFO) has garnered significant clinical attention in recent years, particularly among young adults who experience cryptogenic ischemic strokes, where the prevalence of this cardiac shunt can be as high as 50% [

1,

2]. Consequently, accurate identification of PFO is crucial for determining the underlying etiology, making imaging techniques essential in clinical practice. However, the comprehensive nature of current guidelines may not effectively enhance patient care, leading to adherence issues that can result in false-positive PFO diagnoses. Therefore, standardized TEE protocols with clear quality indicators are necessary for reliable PFO diagnosis [

1,

3].

A PFO is a remnant of embryonic circulation, and approximately 75% of the population experiences closure of the foramen ovale after birth as the lungs expand and left atrial pressure increases. If postnatal fusion of the septum primum and septum secundum does not occur, the PFO persists, creating a shunt between the left and right atria [

3,

4]. In many instances, a PFO remains undetected and is often diagnosed only when complications arise, such as paradoxical emboli [

2,

4,

5].

Although transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with a bubble test demonstrates reasonable sensitivity (46%) and high specificity (99%), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is regarded as the gold standard for effective PFO diagnosis [

6,

7,

8].

However, emerging evidence has shown that in certain contexts, transcranial Doppler and contrast-enhanced transthoracic echocardiography (cTTE) may offer similar diagnostic accuracy to TEE, potentially serving as more accessible screening alternatives when TEE is not feasible [

10].

During TEE, a flexible ultrasound probe is inserted through the esophagus to attain high-resolution images of the heart's atria with reduced sound absorption [

1]. The addition of a contrast medium or foamed NaCl solution during the bubble test is recommended to confirm the presence of a PFO [

1,

5].

International cardiac societies, such as the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), provide detailed protocols for the systematic assessment of the interatrial septum in their guidelines [

1,

3].

Recently, these were further refined by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO), which introduced focused guidance for PFO evaluation in patients with cryptogenic stroke, placing particular emphasis on age stratification, neuroimaging correlation, and individual stroke risk profiles [

11].

Recent European position papers provide an updated, multidisciplinary framework for the management of patients with PFO, covering general approach, risk stratification, and specific high-risk conditions such as decompression sickness, migraine, and arterial deoxygenation syndromes [

12,

13].

However, the comprehensive nature of these recommendations may fall short of achieving the intended improvements in patient care. Therefore, we aimed to develop an algorithm for diagnosing PFO that is tailored for daily clinical practice while maintaining high-quality standards. This study identifies essential quality indicators during TEE examinations based on instances of false-positive PFO diagnoses, aiming to establish an optimal echocardiographic methodology for PFO screening.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) remains the primary diagnostic tool for patent foramen ovale (PFO) assessment, as noted in the outdated 2012 guidelines [

8]. However, there is comparatively limited existing data in the field of congenital heart defects, with diagnostic recommendations carrying an evidence level of C [

9]. In contrast, the therapeutic landscape presents a different scenario. The correlation between cryptogenic stroke and elevated PFO prevalence is well established, leading to a recommendation grade of A and an evidence level of I for PFO closure [

2,

10].

Despite the central role of TEE in PFO workup, recent meta-analytic findings have underscored its limitations. Mojadidi et al. reported a sensitivity of 89.2% and specificity of 91.4% when validated against autopsy findings, illustrating that both missed and false-positive diagnoses can occur, particularly in the setting of suboptimal technique or anatomical variants [

15].

Notably, a study conducted by Johansson et al. in 2010 specifically examined the occurrence of false-negative diagnoses associated with contrast injections in TEE among 14 patients [

16]. Additionally, Rodrigues et al. emphasized the importance of performing an adequate Valsalva maneuver during the bubble test, pointing out that inadequate execution could lead to false-negative diagnoses [

17].

Historically, the focus has largely been on investigating false-negative diagnoses rather than false-positive ones. Therefore, our objective was to assess the incidence and causes of false-positive PFO assessments in patients with cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

2. Materials and Methods

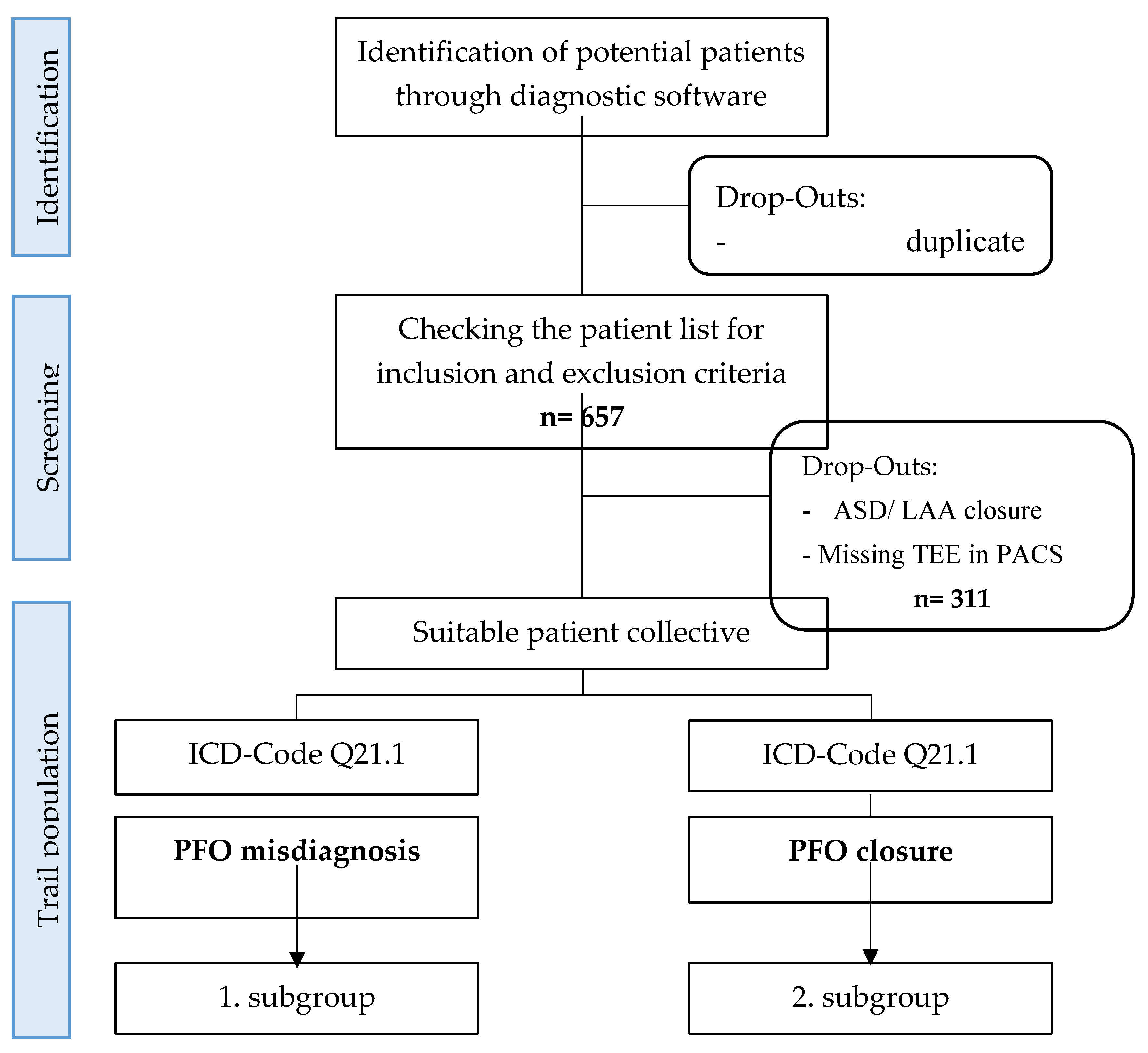

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 346 patients diagnosed with patent foramen ovale (PFO) in conjunction with cryptogenic ischemic stroke as part of a single-center observational study. The data collection period spanned from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021. Among these patients, 326 underwent successful PFO closure, while 20 underwent invasive PFO exclusion. The patient selection process and study design are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Using Metek software HKWin and KardWin, initial patient lists could be created and screened. Further selection of patients who did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria was performed and finally the subdivision into the two subgroups.

ASD: Atrial septal defect, LAA: Left atrial appendage, TEE: transesophageal echocardiography, PACS: Picture Archiving and communication system, ICD: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, OPS: operation and procedure key, PFO: Patent foramen ovale

The analysis was divided into two parts. In the first part, we compared the stored image sequences from screening transesophageal echocardiograms (TEEs) with the diagnostic protocols outlined in current guidelines. In the second part, we evaluated the misdiagnosed TEE images to identify indicators of error by correlating them with the image sequences of correctly diagnosed PFOs. This comparative approach aimed to investigate the relationship between examination sequences and PFO misdiagnosis, ultimately facilitating the identification of key quality indicators for effective diagnosis.

The transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) examinations analyzed in this study were conducted at both the Imaging Department of the Clinic of Cardiology, Pneumology, and Vascular Medicine, as well as the Clinic of Neurology. The procedures were performed by specially trained assistant physicians and cardiologists. We utilized various ultrasound machines, including the GE Logiq S8, Philips IE33, and Philips EPIQ 7, equipped with Philips X7-t2, X8-t2, and GE 6Tc Rs ultrasound probes.

Our analysis focused on imaging sequences of the interatrial septum (IAS). TEE examinations were triaged using the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) for image data management. To enhance readability, we employed the commonly accepted English terminology for the probe positions, which included the upper esophageal short axis view (UE SAX), mid-esophageal short axis at the level of the aortic valve (ME AV SAX), mid-esophageal four-chamber view (ME 4CV), and mid-esophageal bicaval view (ME Bicaval). These probe positions, along with their respective angle settings, were used as key parameters for analysis, allowing for both 2D and 3D imaging, as well as assessment of the bubble test.

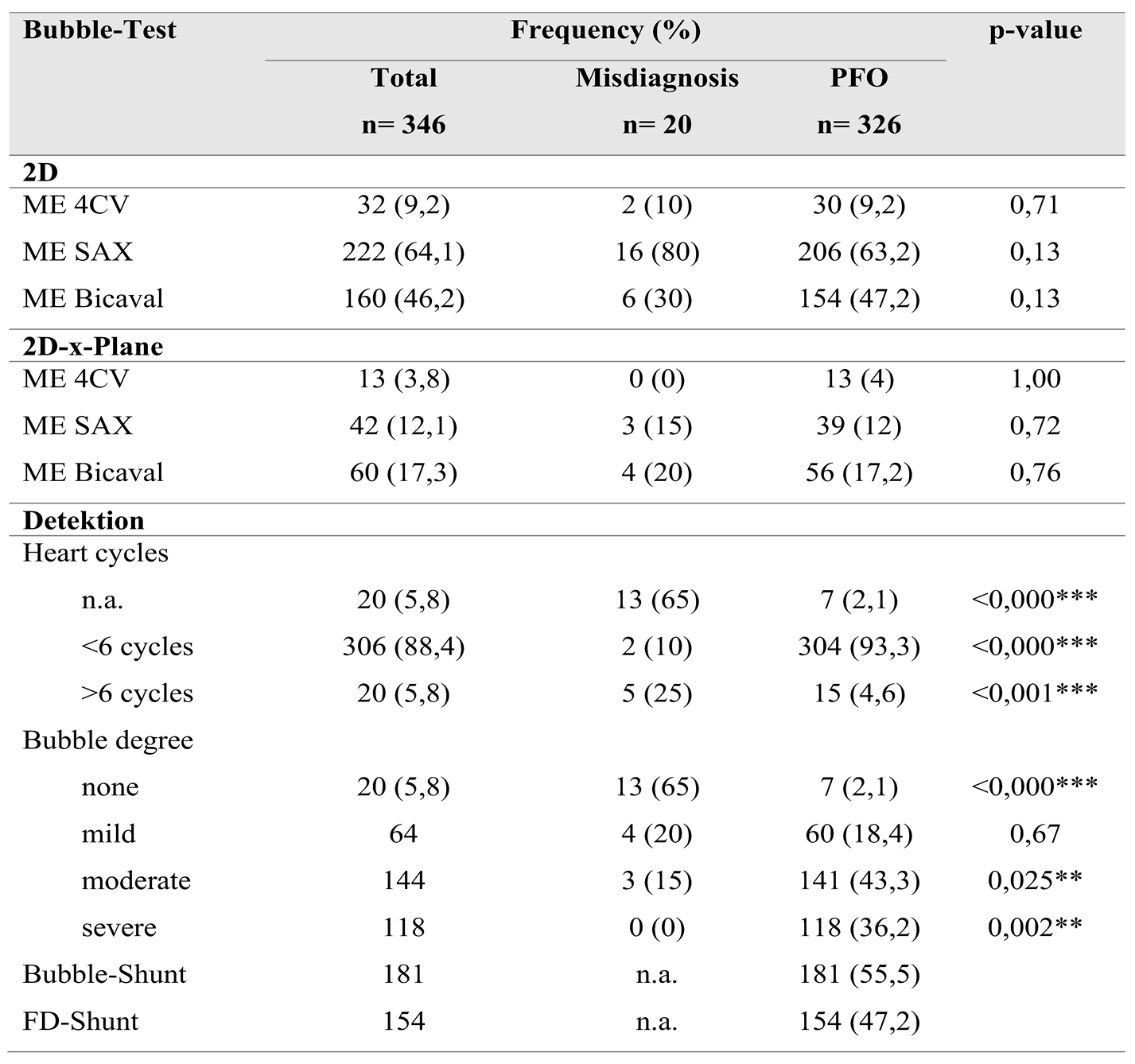

The bubble test results were evaluated based on the timing of bubble crossing and the quantity of bubbles that crossed into the left atrium. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics software. Significance was assessed using the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, with a p-value of <0.05 deemed significant at a 95% confidence interval for all statistical tests conducted.

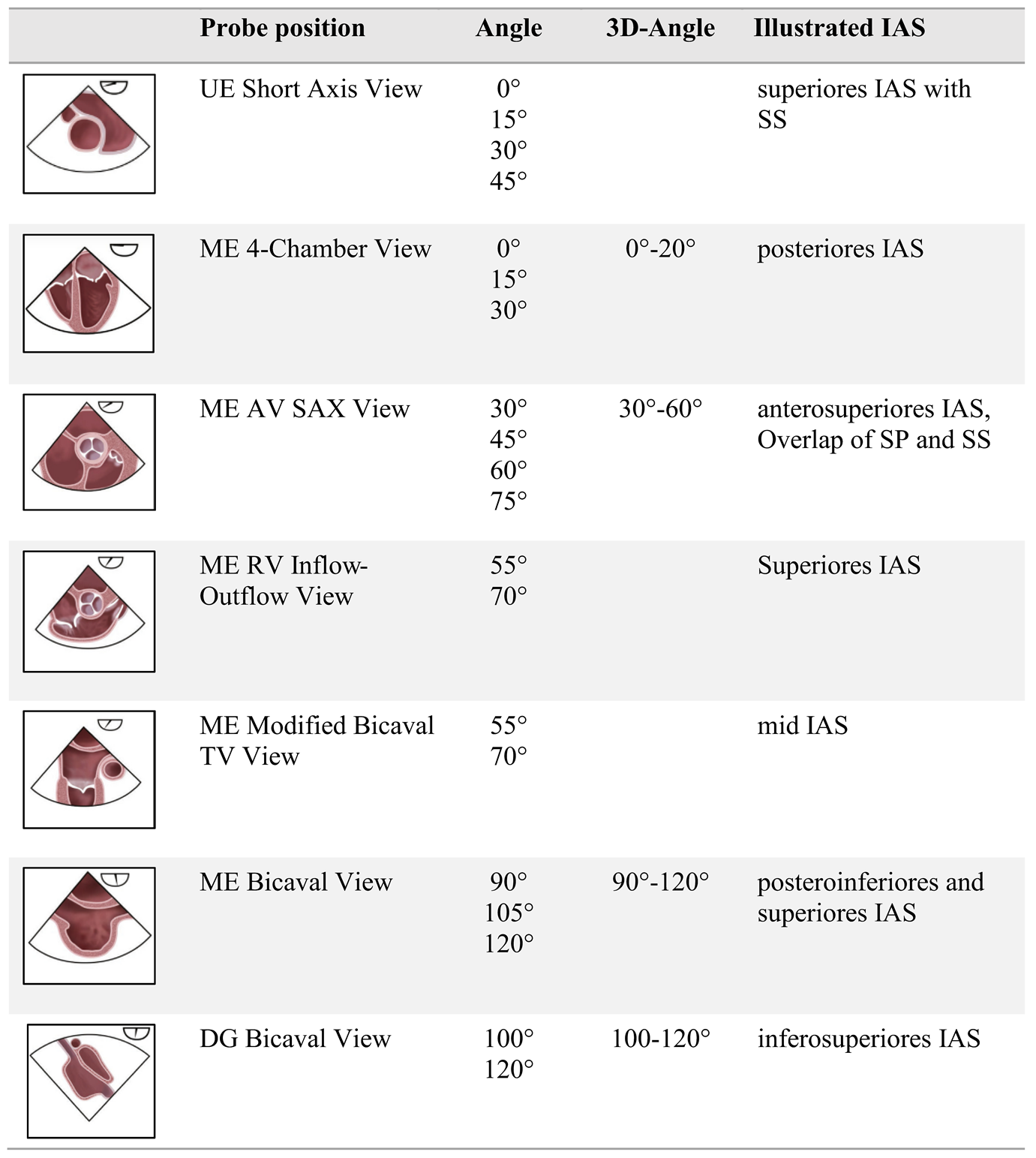

The probe positions and angle recommendations used in this study are summarized in

Table 1, in accordance with current guideline standards.

3. Results

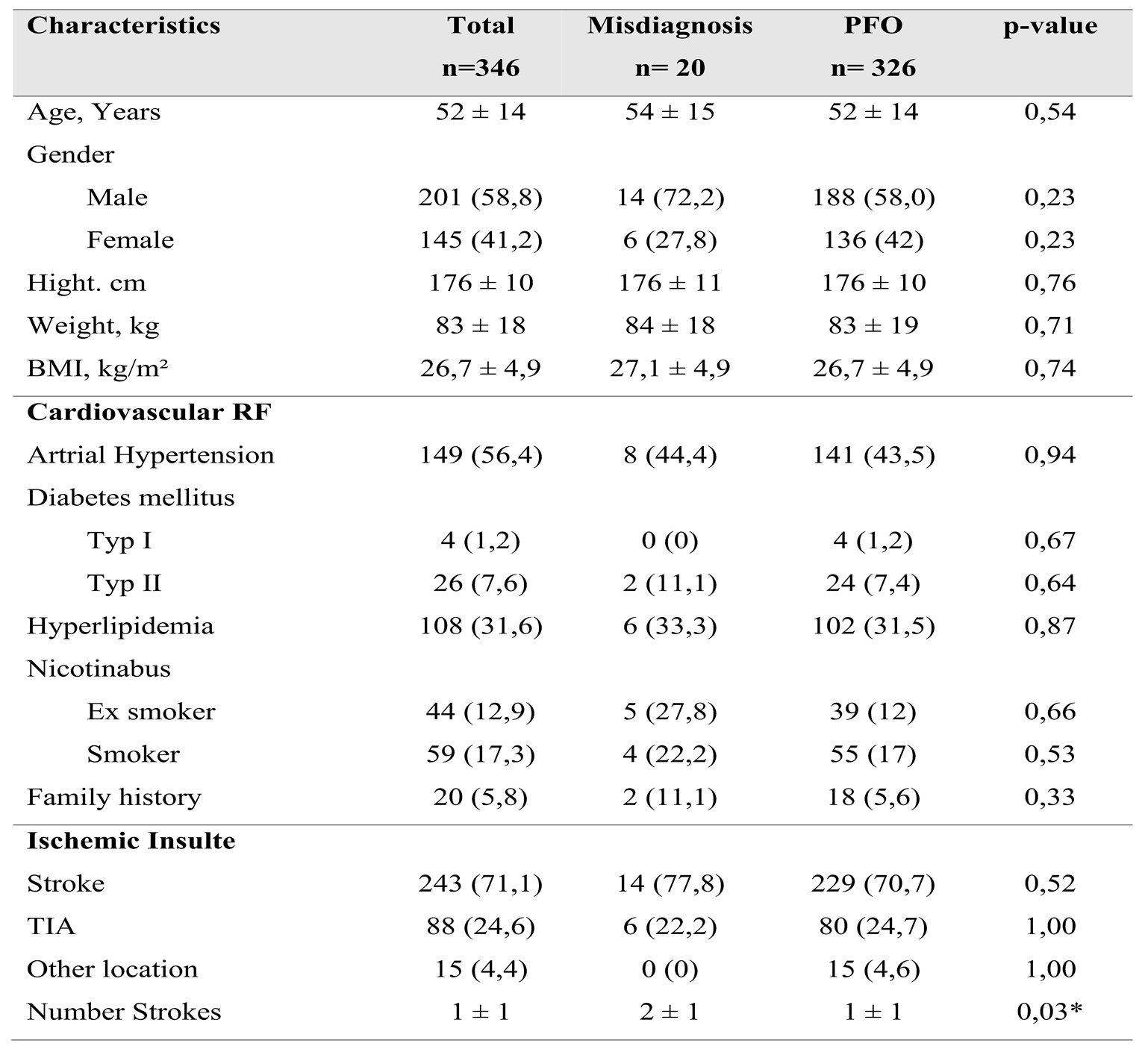

A total of 346 patients with a mean age of 52±14 years were included in the study. The patient population was divided into two groups: 20 patients (5.8%) with misdiagnosed patent foramen ovale (PFO) and 326 patients (94.2%) with confirmed PFO occlusions. There were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors, including arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, nicotine use, and positive family history, between the two groups. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in

Table 2.

Overview of Patient Characteristics, Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Neurological History Regarding Ischemic Insults

A total of 346 patients with a mean age of 52±14 years were included in the study. The patient population was divided into two groups: 20 patients (5.8%) with misdiagnosed patent foramen ovale (PFO) and 326 patients (94.2%) with confirmed PFO occlusions. There were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors, including arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, nicotine use, and positive family history, between the two groups.

Among the study population, 243 patients (71.1%) experienced cerebral ischemia, 84 patients (24.6%) had transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and 15 patients (4.4%) presented with paradoxical embolism of other origins. The relative incidence of these conditions was similar between both groups, except for paradoxical embolism; all 15 cases were assigned to the PFO group.

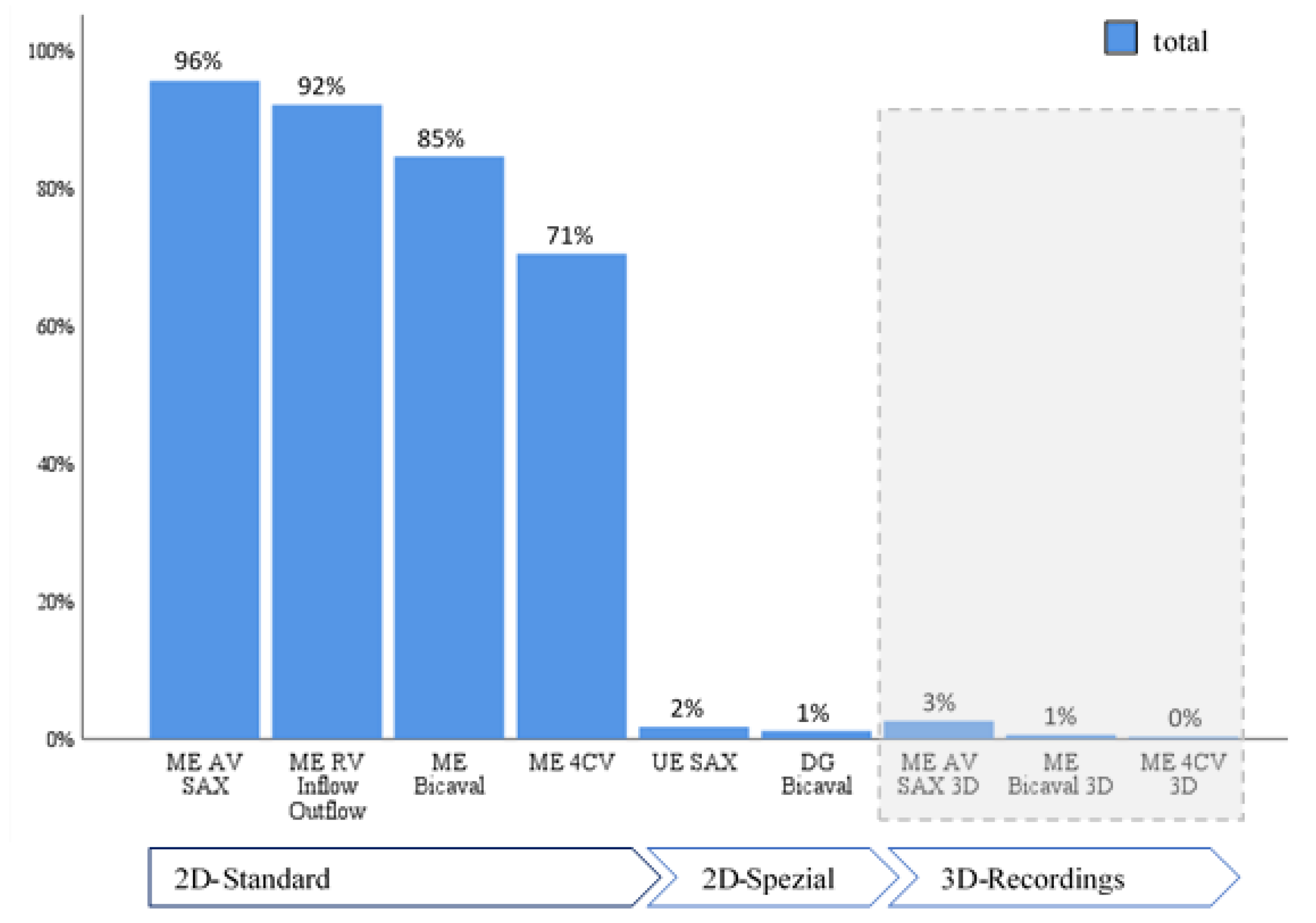

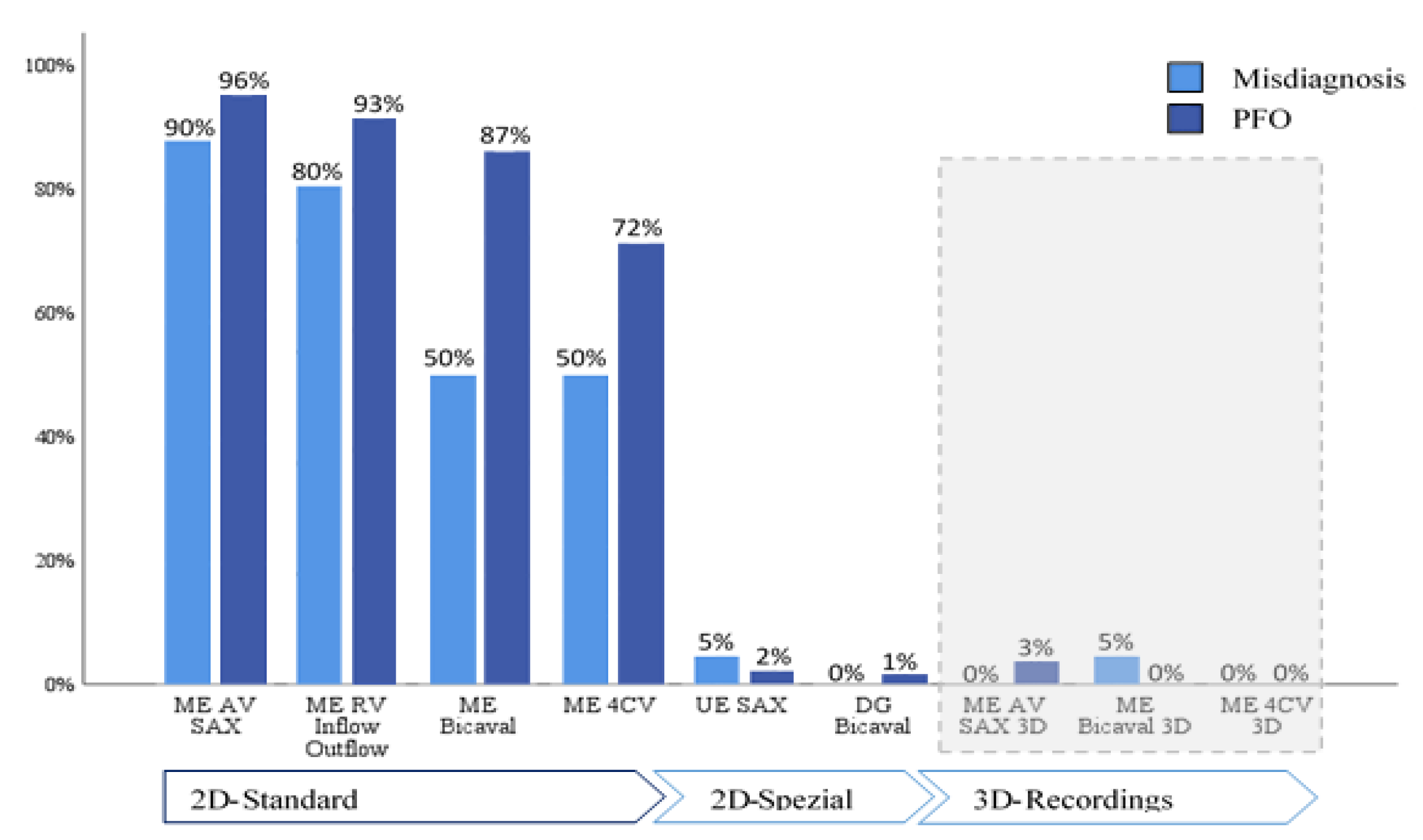

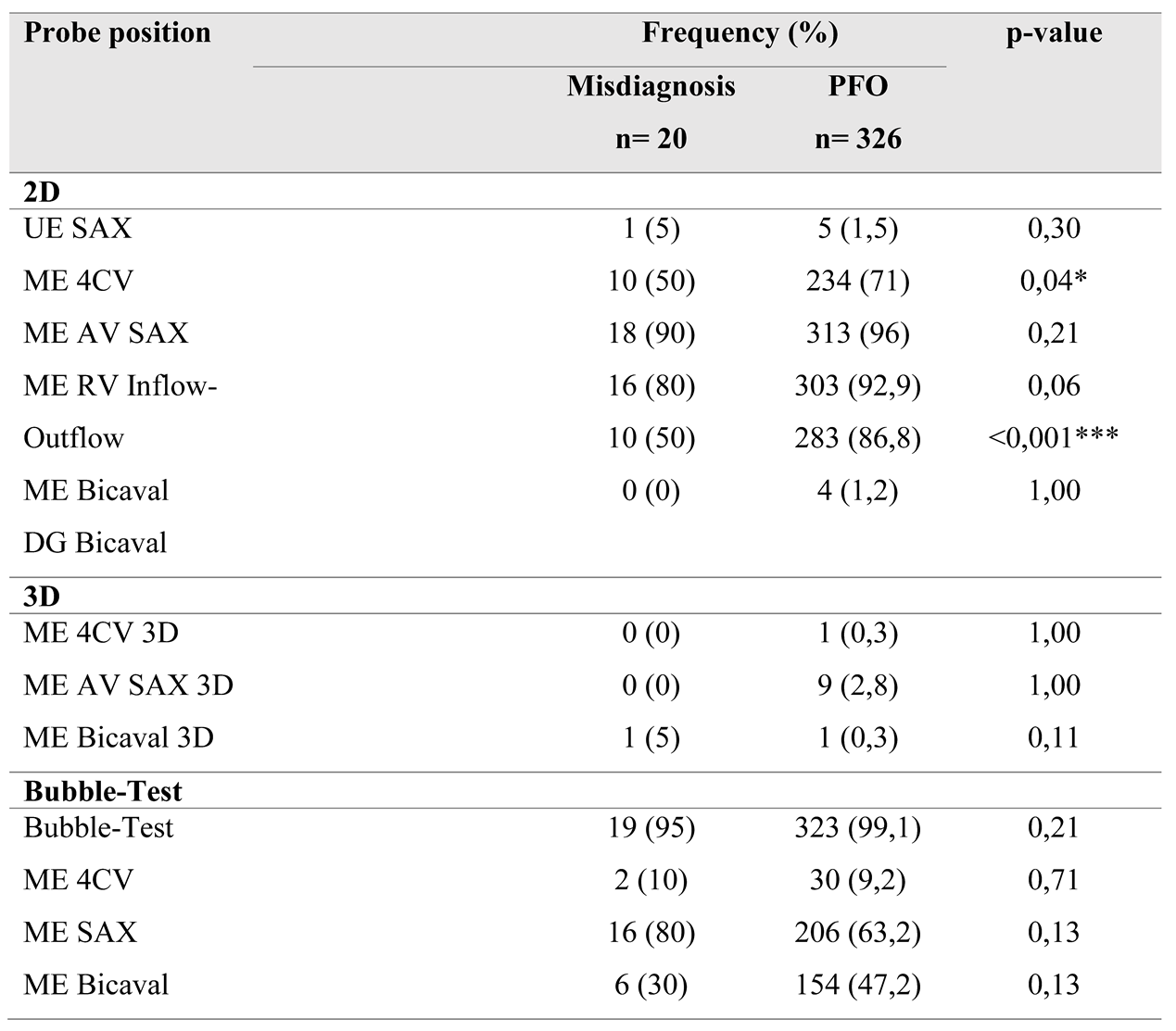

When evaluating adherence to guidelines across the entire cohort, it was noted that imaging planes in the mid-esophagus were used significantly more frequently than modified probe positions in the upper and transgastric planes (71-96% vs. 1-2%). The mid-esophageal aortic valve short axis view (ME AV SAX) was employed in 95% of TEE diagnoses, while the mid-esophageal right ventricular inflow and outflow view (ME RV Inflow Outflow) was observed in 92% of examinations. Three-dimensional imaging of the interatrial septum (IAS) was infrequently performed (0-3%). To align with guidelines, the bubble test was utilized in 98.8% of the 346 examinations, with only four cases omitting this test (

Table 4). Overall use of probe positions is visualized in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Comparing the two subgroups revealed a lower overall frequency of diverse probe positions in the misdiagnosis group. Specifically, in this group, the IAS was predominantly presented in the mid-esophageal short axis view (ME AV SAX), observed in 90% of cases.

Detailed frequencies of probe views and bubble test performance across both groups are provided in

Table 3.

This setting was also prevalent in the PFO group (96%). However, a statistically significant difference of 21% in the frequency of the four-chamber view was noted between the groups (50% vs. 71%, p=0.04). A highly significant difference (p<0.001) was observed in the bicaval view in the mid-esophagus, albeit with a small effect size (V=0.2)

The bubble test was conducted in 95% of the misdiagnosis group and in 99.1% of the control group (p=0.12). In the misdiagnosis group, visualization during the bubble test occurred in 80% using the short axis view and in 30% using the bicaval view. In comparison, the control group demonstrated frequencies of 63% and 47%, respectively. IAS imaging in x-plane mode was similarly low in both groups (35% vs. 33%). In 88% of all bubble tests, the first microbubbles were detected in the left atrium (LA) within the first six cardiac cycles; this criterion was met in only two cases (10%) within the misdiagnosis group. Additionally, two-thirds (65%) of bubble tests in the misdiagnosis group showed no bubbles in the LA during recorded image sequences, contrasted with only 2% in the control group, resulting in a high level of significance (p<0.001). In this subgroup, more than six microbubbles appeared in the LA in 79.5% of tests, demonstrating highly significant differences (p=0.02).

4. Discussion

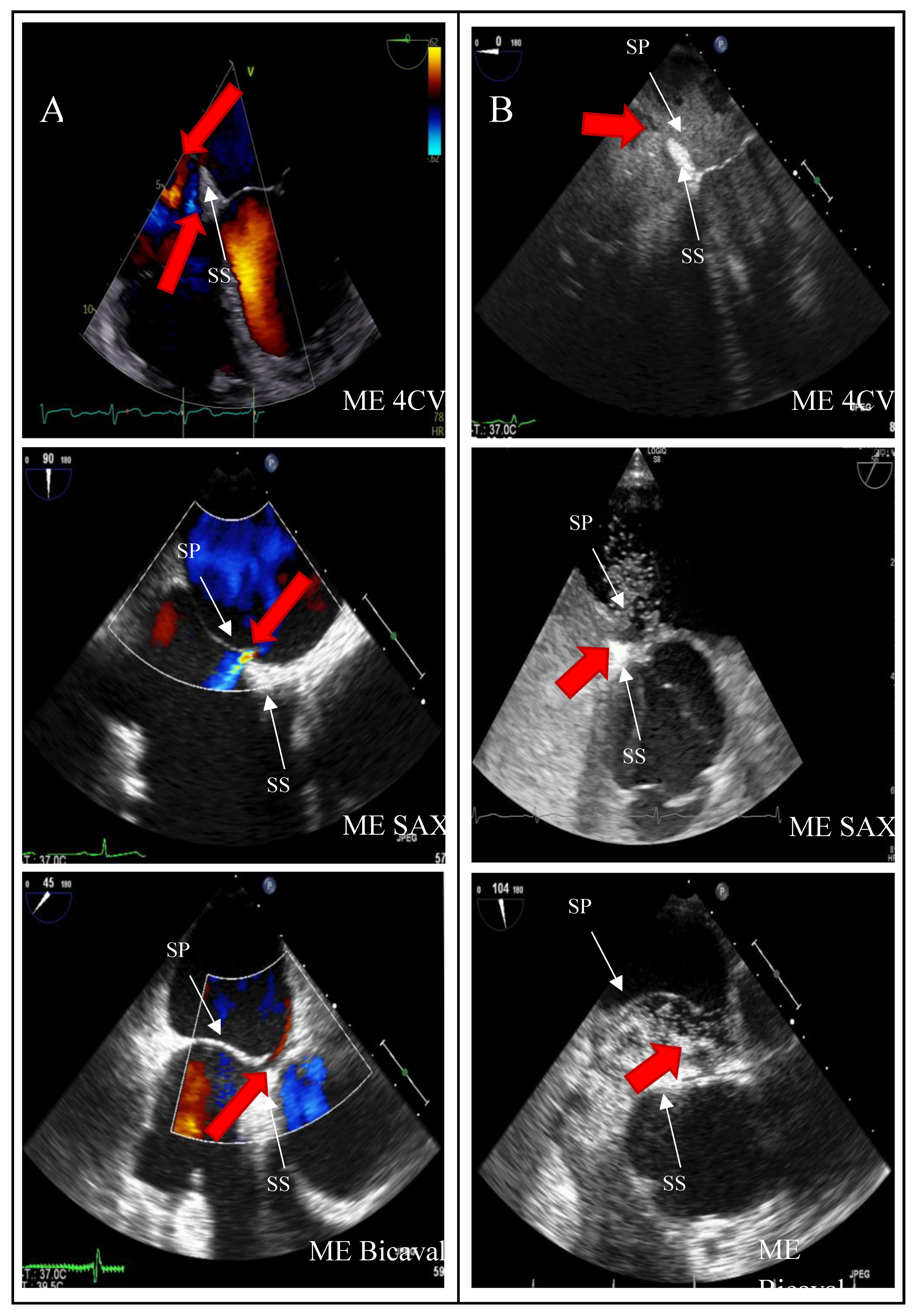

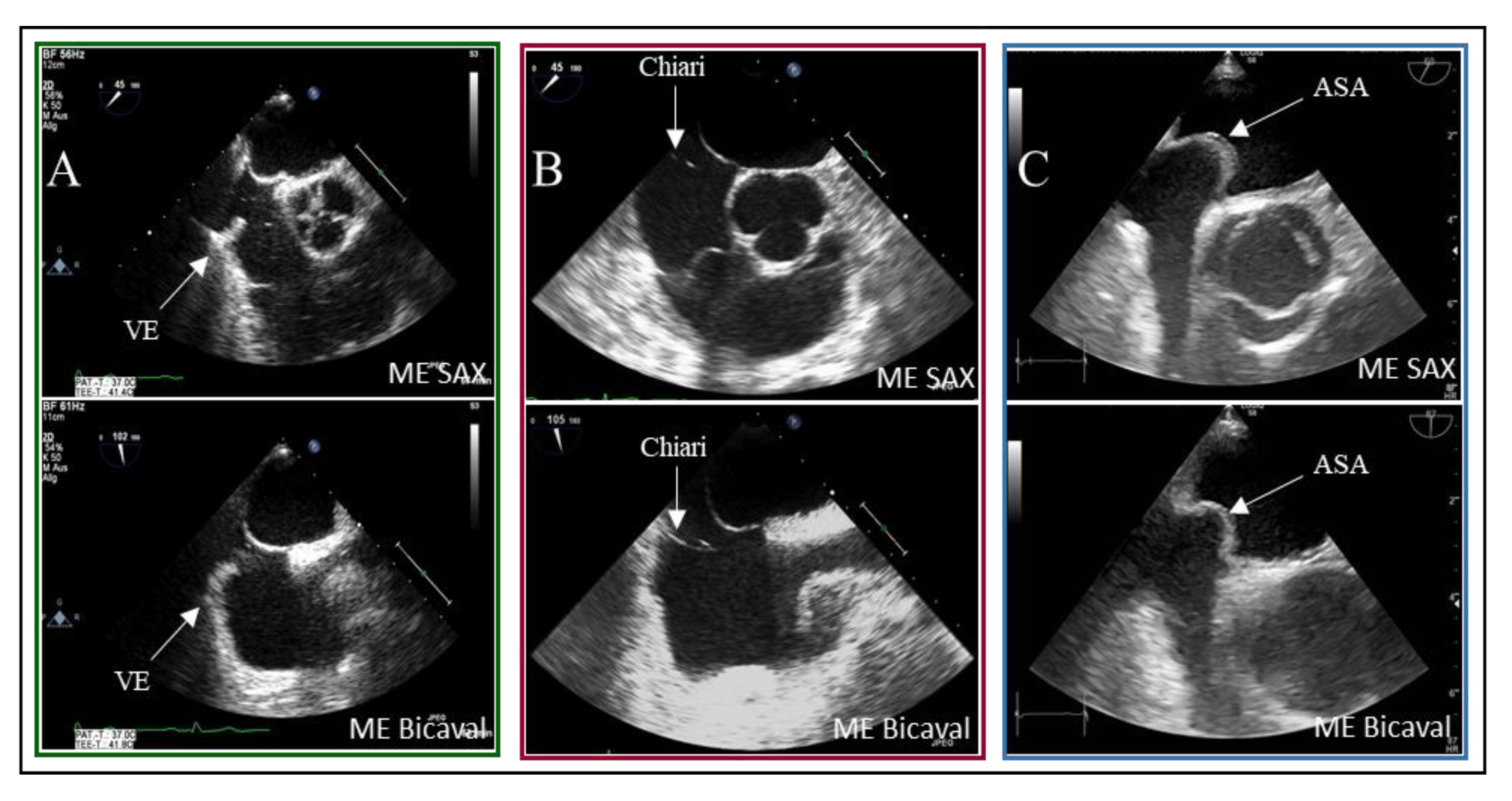

Despite guideline recommendations, standardization in patient care is essential. Echocardiographic imaging procedures are often highly examiner-dependent, leading to variability in performance. Given the results presented, we investigated whether precise quality indicators could enhance the reliability of PFO diagnosis in the context of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Standard TEE views demonstrating PFO shunting are shown in

Figure 3.

Among the initial patient population of 653 referred for PFO diagnosis from smaller hospitals or office-based physicians, only approximately half (n=346) underwent pre-interventional screening TEE at the UKD facilities. Over a data collection period of 10 years, 23 cases of false-positive PFO findings were identified during elective interventional procedures in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Of these, the echo examinations of 20 patients were included in the analysis reported here, with a patient-to-group ratio of 1.

Substudy 1: In the initial analysis of the TEE examinations, the complete dataset was examined. Common probe positions ranged from 70% to 95% prevalence at the mid-esophageal level. However, visualization of the interatrial septum (IAS) in the four-chamber view was often inadequate, as the IAS was not fully visible. Although three-dimensional (3D) imaging is now standardized for valve assessment and is recommended for PFO diagnosis in ambiguous cases, 3D imaging of the IAS was performed in only 4% of the 346 TEEs analyzed. Contrast echocardiography utilizing bubble testing was conducted in 99% of the cases within the dataset.

Sub-study 2: This sub-study aimed to compare the echocardiographic images of patients with false-positive PFO diagnoses against those with accurate diagnoses to determine the necessary steps and views in TEE for confirming a PFO diagnosis. Overall, there was less variability in the probe settings used to visualize the interatrial septum (IAS) within the false-positive group compared to the accurate diagnosis group. In the misdiagnosis group, IAS imaging predominantly occurred in the mid-esophageal short axis (80-90%).

These findings align with previously published observations on procedural pitfalls, such as misaligned imaging planes, suboptimal probe angulation, or lack of experience with shunt visualization during TEE [

18].

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional TOE recordings of an IAS with PFO.Shown is a short circuit between the RA and LA in ME 4CV, ME SAX, ME Bicaval image planes (A) in the color Doppler and (B) in the bubbles test; the red arrow indicates the direction of the short circuit.ME: midesophageal, SAX: short axis, 4CV: four chamber view, SP: septum primum, SS: septum secundum.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional TOE recordings of an IAS with PFO.Shown is a short circuit between the RA and LA in ME 4CV, ME SAX, ME Bicaval image planes (A) in the color Doppler and (B) in the bubbles test; the red arrow indicates the direction of the short circuit.ME: midesophageal, SAX: short axis, 4CV: four chamber view, SP: septum primum, SS: septum secundum.

The PFO is situated in the anterior-superior part of the fossa ovalis [

3]. Visualization of the anterior fossa ovalis limb on TEE is typically achieved only in the short axis at the level of the aortic valve (mid-esophageal aortic valve short axis view, ME AV SAX). However, statistical analysis revealed no significant correlation between this probe position and diagnostic accuracy (p=0.21; odds ratio [OR] 2.99). In contrast, the mid-esophageal bicaval view (ME Bicaval) demonstrated a strong correlation with accurate diagnoses (p<0.001; OR 5.23), as it presents the superior aspect of the fossa ovalis where the PFO is located [

3]. Additionally, the four-chamber view was found to be statistically significant (p=0.04; OR 1.12); however, its relevance in PFO diagnostics is questionable as it primarily images the posterior region of the fossa ovalis limbus, which is less important for PFO identification.

These recommendations are consistent with the latest expert consensus on the treatment of PFO, which emphasizes individualized patient selection, optimal procedural techniques, and structured follow-up to maximize clinical benefit [

21].

Previous studies indicate that methods such as the bubble test can achieve sensitivity levels of 96% when optimally performed [

16]. Given the anterior-superior location of the PFO within the fossa ovalis, we also sought to explore whether probe position influenced the outcomes of the bubble test. No correlations were found between probe position and diagnostic group, whether in conventional imaging (p=0.13-0.71) or in x-plane mode (p=0.71-1.0). In conventional 2D imaging, both the mid-esophageal short axis (p=0.13) and bicaval views (p=0.13) exhibited better correlation evidence. However, x-plane representation during the bubble test did not significantly affect diagnostic confidence in this analysis, which may be attributed to the low frequency of observations in the PFO group.

As outlined in the guidelines, the appearance of microbubbles in the left atrium (LA) within the first six cardiac cycles is highly significant (p=<0.000). In 90% of the misdiagnosis group, this dynamic was absent, while early crossing was observed in over 90% of the PFO cases. Moreover, statistical analyses support a correlation between the number of bubbles crossed and PFO diagnosis, indicating that the absence of bubble crossing in the LA strongly suggests a negative PFO diagnosis (p=<0.000). Unexpectedly, no positive bubble tests were detected in seven TEE examinations despite the presence of PFO. Retrospective image analysis does not conclusively determine whether there was no bubble crossing or if that aspect of the examination was not recorded.

Correctly diagnosed PFOs reliably showed inflow of more than six microbubbles within the first six cardiac cycles in 98.8% of cases, compared to only 15% in the false positive group.

However, false negative results during the bubble test can also occur, particularly in cases of insufficient Valsalva or delayed right atrial opacification. In this context, clinicians should be aware of limitations in sensitivity even with proper technique [

22].

False positive PFO diagnoses could be attributed to intrapulmonary shunts during late inflow. TEE studies from the false diagnosis group indicated a clustered occurrence of spontaneous echo contrast in the left atrium, which may simulate a positive bubble test. In 2D imaging, this increased echogenicity manifests as a “fog” in the blood, attributed to heightened erythrocyte aggregation [

17].

In eleven of the 20 misdiagnosed cases, spontaneous contrast was observed in the left atrium (LA). The timing of microbubble appearance in LA serves as a general guideline but is not a reliable indicator. According to Soliman et al., there is significant temporal overlap in the occurrence of bubbles in LA from both a PFO and a proximal interpulmonary shunt [

18]. As illustrated, the presence of interatrial septum (IAS) hypermobility significantly influences the timing of bubble crossover. Delayed crossing may result from residual fetal structures in the right atrium, such as the Eustachian valve and the Chiari network. In 5% of patients with PFO, bubbles were detected in LA after six heartbeats.

Examples of residual fetal structures are shown in

Figure 4.

This analysis revealed a statistical association between high-grade shunt intensity and PFO diagnosis in the context of IAS hypermobility (p=0.02). In contrast, remnants of fetal circulation did not significantly impact shunt flow intensity. However, delayed contrast filling of the right atrium remains visible in the imaging sequences, which is critical for the bubble test, as indicated by Johansson et al. [

16].

Accurate execution of the bubble test is essential and may require repetition in instances where findings are inconsistent. Interventional PFO exclusions benefit from having injections into the femoral vein, which provides the highest sensitivity, particularly when enhanced by the Eustachian valve.

Historically, the understanding of PFO has evolved significantly. Initially regarded as a benign anatomical variant, it is now recognized as a potential conduit for paradoxical embolism and a target for intervention in cryptogenic strokes. This shift underscores the growing importance of robust diagnostic algorithms and therapeutic clarity [

23].

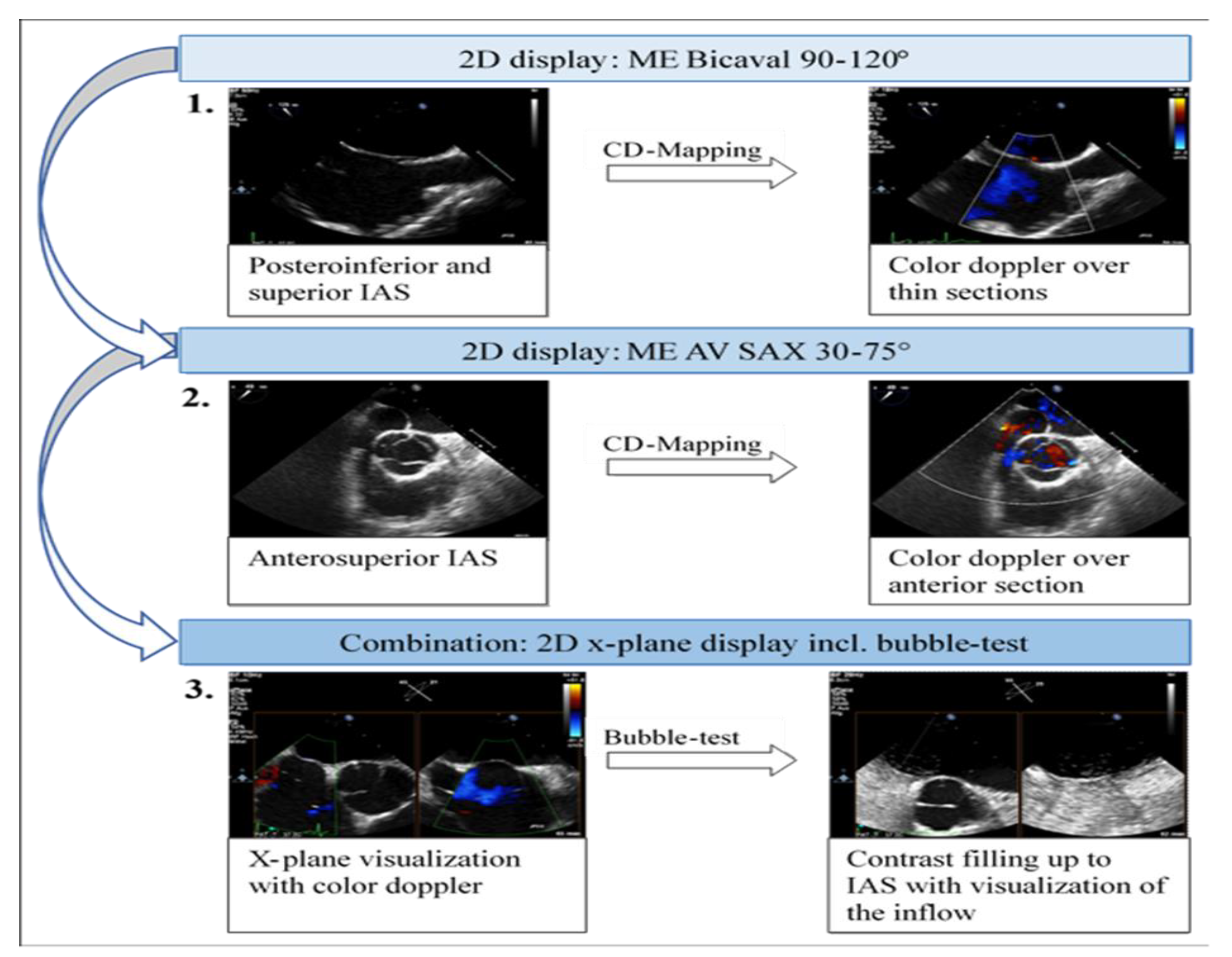

Figure 5.

Illustration of a possible examination procedure based on five quality criteria. These major criteria in TEE are necessary to confirm the diagnosis based on the results and the anatomical location of the PFO, to avoid invasive PFO exclusion in the future. 2D: two-dimensional, ME: midesophageal, AV: aortic valve, SAX: short axis, IAS: interatrial septum, 3D: three-dimensional.

Figure 5.

Illustration of a possible examination procedure based on five quality criteria. These major criteria in TEE are necessary to confirm the diagnosis based on the results and the anatomical location of the PFO, to avoid invasive PFO exclusion in the future. 2D: two-dimensional, ME: midesophageal, AV: aortic valve, SAX: short axis, IAS: interatrial septum, 3D: three-dimensional.

5. Conclusions

To develop a strategy for reducing false positive diagnoses of patent foramen ovale (PFO), we retrospectively analyzed 346 TEE examinations at the University Hospital Düsseldorf. Although color Doppler mapping and the bubble test were performed in all examinations, not all recommendations outlined in the guidelines were adequately followed.

Visualization of the interatrial septum (IAS) from the upper esophagus or gastric views is rarely achieved in PFO diagnostics, and three-dimensional imaging of the IAS is infrequent in clinical practice. The sequential acquisition of IAS images primarily occurred from the mid-esophagus in the two-dimensional short-axis and bicaval views. For efficient and reliable IAS visualization, the bubble test should be conducted in the mid-esophagus utilizing x-plane mode with the short axis (30-75°) and the bicaval view (90-120°). This approach facilitates parallel visualization of the anterosuperior portion of the fossa ovalis and the inflow of bubbles via the superior vena cava (SVC).

The extent to which a structured procedure with defined quality indicators in transesophageal echocardiography can enhance the reliability of PFO diagnosis is limited by our comparative analysis of the two subgroups. To further evaluate this hypothesis, it is necessary to validate the major criteria defined in the following section in subsequent studies. By implementing a summarized version of the current guidelines, PFO diagnostics can be better structured within clinical routines.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: Zeus, Afzal. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Phinicarides, Berning, Afzal. Drafting of the manuscript: Phinicarides, Berning, Afzal. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Heidari, Kanschik, Klein, Polzin, Kelm, Jung, Werner, Zeus. Statistical analysis: Phinicarides, Berning, Afzal, Zeus. Obtained funding: none. Administrative, technical, or material support: Berning, Afzal, Zeus. Study supervision: Zeus, Afzal.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Düsseldorfer Beobachtungsregister zum interventionellen PFO-Verschluss (protocol code 2019-559_9 on September 2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2D |

Two-Dimensional |

| 3D |

Three-Dimensional |

| ASA |

Three letter acronym |

| ASD |

Linear dichroism |

| AV |

Aortic valve |

| cTTE |

Contrast enhanced transthoracic echocardiography |

| DG |

Deep transgastric |

| ESO |

European Stroke Organisation |

| ESC |

European Society of Cardiology |

| FD |

Color Doppler (Farbdoppler) |

| IAS |

Interatrial septum |

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases |

| LA |

Left atrium |

| LAA |

Left atrial appendage |

| LV |

Left ventricle |

| ME |

Mid-esophageal |

| OPS |

Operation and procedure coding system (Germany) |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PACS |

Picture archiving and communication system |

| PFO |

Patent foramen ovale |

| RA |

Right atrium |

| RV |

Right ventricle |

| SAX |

Short axis view |

| SP |

Septum primum |

| SS |

Septum secundum |

| SVC |

Superior vena cava |

| TEE |

Transesophageal echocardiography |

| TIA |

Transient ischemic attack |

| TTE |

Transthoracic echocardiography |

| UE |

Upper esophageal |

| VE |

Valvula Eustachii |

References

- Silvestry, Frank E.; Cohen, Meryl S.; Armsby, Laurie B.; Burkule, Nitin J.; Fleishman, Craig E.; Hijazi, Ziyad M. et al. (2015): Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of Atrial Septal Defect and Patent Foramen Ovale: From the American Society of Echocardiography and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. In: Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 28 (8), p. 910–958. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, A.; Liebetrau, C.; Diener, H.-C.; Elsässer, A.; Grau, A.; Gröschel, K.; et al. (2018): Interventioneller PFO-Verschluss. In: Kardiologe 12 (6), S. 415–423. [CrossRef]

- Saric, Muhamed; Armour, Alicia C.; Arnaout, M. Samir; Chaudhry, Farooq A.; Grimm, Richard A.; Kronzon, Itzhak et al. (2016): Guidelines for the Use of Echocardiography in the Evaluation of a Cardiac Source of Embolism. In: Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 29 (1), S. 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Blum, Ulrike; Meyer, Hans; Beerbaum, Philipp (2016): Kompendium angeborene Herzfehler bei Kindern. Diagnose und Behandlung. Berlin, Heidelberg, p.l.: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Diener, Hans-Christoph; Grau, Armin; Baldus, Stephan et al. (2018): Kryptogener Schlaganfall und offenes Foramen ovale. Leitlinie für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie. Hg. v. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Available online at https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/030-142l_S2e_Kryptogener_ Schlaganfall_2018-08-verlaengert.pdf, last checked on 11.07.2021.

- Zhao, Enfa; Wei, Yajuan; Zhang, Yafei; Zhai, Nina; Zhao, Ping; Liu, Baomin (2015): A Comparison of Transthroracic Echocardiograpy and Transcranial Doppler With Contrast Agent for Detection of Patent Foramen Ovale With or Without the Valsalva Maneuver. In: Medicine 94 (43), e1937. [CrossRef]

- chuchlenz, H.; Pachler, C.; Binder, R.; Mair, J.; Toth, GG.; Gabriel, H. (2019): Review und Leitlinien für die Diagnostik und den interventionellen Verschluss des persistierenden Foramen ovale (PFO) // Review and guidelines for diagnosis and interventional closure of PFO. Available online at https://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/14448.pdf, last checked on 11.07.2021.

- Hahn, Rebecca T.; Abraham, Theodore; Adams, Mark S.; Bruce, Charles J.; Glas, Kathryn E.; Lang, Roberto M. et al. (2013): Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. In: Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 26 (9), p.921–964. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, Helmut; Backer, Julie de; Babu-Narayan, Sonya V.; Budts, Werner; Chessa, Massimo; Diller, Gerhard-Paul et al. (2021): 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. In: European heart journal 42 (6), p.563–645. [CrossRef]

- Lanzone A, Castelluccio EV, Della Pina P, Boldi E, Lussardi G, Frati G, Gaudio C, Biondi-Zoccai G. Comparative Diagnostic Accuracy of Transcranial Doppler and Contrast-Enhanced Transthoracic Echocardiography for the Diagnosis of Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Defect. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2021.

- Caso V, Turc G, Abdul-Rahim AH, Castro P, Hussain S, Lal A, Mattle HP. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) After Stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021.

- European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism: Pristipino C, Sievert H, D’Ascenzo F, Mas JL, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, Gaita F, Toni D, Kyrle P, Thomson J, Derumeaux G, Onorato E, Sibbing D, Germonpré P, Berti S, Chessa M, Bedogni F, Dudek D, Hornung M, Zamorano J; European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI); European Stroke Organisation (ESO); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI); Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC); ESC Working Group on GUCH; ESC Working Group on Thrombosis; European Haematological Society (EHA). European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. EuroIntervention. 2019 Jan 20;14(13):1389–1402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. Part II – Decompression sickness, migraine, arterial deoxygenation syndromes and select high-risk clinical conditions: Pristipino C, Germonpré P, Toni D, Sievert H, Meier B, D’Ascenzo F, Berti S, Onorato EM, Bedogni F, Mas JL, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, Gaita F, Kyrle PA, Thomson J, Derumeaux G, Sibbing D, Chessa M, Hornung M, Zamorano J, Dudek D; EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS TEAM. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. Part II – Decompression sickness, migraine, arterial deoxygenation syndromes and select high-risk clinical conditions. EuroIntervention. 2021 Aug 6;17(5):e367–e375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunert, Dustin (2018): Sekundärprävention Schlaganfall: Schützende Schirmchen. In: Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online. [CrossRef]

- Mojadidi, Mohammad Khalid; Bogush, Nikolay; Caceres, Jose Diego; Msaouel, Pavlos; Tobis, Jonathan M. (2014): Diagnostic accuracy of transesophageal echocardiogram for the detection of patent foramen ovale: a meta-analysis. In: Echocardiography (Mount Kisco, N.Y.) 31 (6), p.752–758. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, Magnus C.; Eriksson, Peter; Guron, Cecilia Wallentin; Dellborg, Mikael (2010): Pitfalls in diagnosing PFO: characteristics of false-negative contrast injections during transesophageal echocardiography in patients with patent foramen ovales. In: Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 23 (11), p.1136–1142. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Ana Clara; Picard, Michael H.; Carbone, Aime; Arruda, Ana Lúcia; Flores, Thaís; Klohn, Juliana et al. (2013): Importance of adequately performed Valsalva maneuver to detect patent foramen ovale during transesophageal echocardiography. In: Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 26 (11), p.1337–1343. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, Osama I. I.; Geleijnse, Marcel L.; Meijboom, Folkert J.; Nemes, Attila; Kamp, Otto; Nihoyannopoulos, Petros et al. (2007): The use of contrast echocardiography for the detection of cardiac shunts. In: European journal of echocardiography: the journal of the Working Group on Echocardiography of the European Society of Cardiology 8 (3), p.2–12. [CrossRef]

- Weber T; Auer J; Berent R; Eber B (2001): Schlaganfall - was der Kardiologe beitragen kann. Available online at https://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/803.pdf, last checked on 11.07.2021.

- Song JK. Pearls and Pitfalls in the Transesophageal Echocardiographic Diagnosis of Patent Foramen Ovale. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022.

- Treatment of patent foramen ovale: Pristipino C, Carroll J, Mas JL, Wunderlich NC, Søndergaard L. Treatment of patent foramen ovale. EuroIntervention. 2025 May 16;21(10):505–524. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgwairi E, Dickson S, Friedman BM. Be Aware of False Negative Bubble Study in Diagnosis of Patent Foramen Ovale! Echocardiography. 2020.

- Maloku A, Hamadanchi A, Günther A, Aftanski P, Schulze PC, Möbius-Winkler S. Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO): History, Diagnosis, and Management. Herz. 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).