1. Introduction

The Sm domain is an ancient RNA-binding motif with oligo(U) specificity, which assembles into heteroheptameric rings [

1], with similarity to nuclear Sm core ribonucleoprotein rings in the spliceosome, and to cytosolic Like-Sm (LSm) ribonucleoprotein rings that mediate mRNA decapping and decay [

2]. In bacteria and archaea, the Sm domains in Hfq homologs were extensively studied to characterize their best known role in intron splicing from pre-mRNA, but also to demonstrate their functions as chaperone that mediates interactions between regulatory non-coding RNAs with their targets, and functions for the maturation of tRNAs/rRNAs [

3].

Upon the evolution of multi-domain proteins in eukaryotic cells, RNA processing became more efficient with the appearance of a cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein family with a length from 600 to 1000 amino acids (exemplified by the

Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast protein Pbp1), which provides binding sites (i) for RNA at a Lsm domain, (ii) for RNA helicases in the area from the Lsm to the Lsm-associated domain (LsmAD) sequences, and (iii) for poly(A)-binding proteins at a PAM2 motif. In cellular stress periods, Pbp1 and all its orthologs relocalize away from the translation apparatus to the stress granules where RNA quality control and triage is performed [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Further currently studied family members include ATX-2 in

Caenorhabditis elegans worms [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], dATX2 in

Drosophila melanogaster flies [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], and ATXN2 in

Gallus gallus birds [

29]. With increasing organism mass and outside the temperate sea environment, a gene duplication was conserved since ray-finned fish until mammals (where the less abundant, but N-terminally much extended, version with some 1300 amino acids was called Ataxin-2 or hATXN2 in humans, while a relatively unchanged and more abundant version with some 1000 amino acids is known as Ataxin-2-like or ATXN2L). Also land plants carry two gene copies (known in

Arabidopsis thaliana as CID3/CID4) [

30].

The study of patients with autosomal dominant, chronically progressive spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) identified unstable expansions of a polyglutamine (polyQ) domain surrounded by Proline-rich motifs (PRM) in the N-terminus of hATXN2 as disease cause [

31,

32,

33], providing a name for this gene family, as well as initial insights into its physiological and pathological roles [

10,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Subsequent findings that this gene modifies the risk and disease progression of adult motor neuron degenerations such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58] intensified analyses of its impact on RNA maturation and RNA quality control in stress granules [

15,

18,

19,

22,

25,

28,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Mammalian ATXN2 appears to mediate rapid stress responses and increase fitness, because its deletion results in obesity, hepatosteatosis, hyperinsulinemia and hypercholesterolemia [

39,

48], while its excessive gain-of-function restricts nutrient endocytosis, represses mTORC1-dependent growth, decreases cholesterol biosynthesis and depletes myelin lipids [

41,

50,

66,

71]. Interestingly, the circadian clock precise rhythms are regulated by oscillating waves of translation, where ATXN2 depletion triggers an advanced phase shift, whereas ATXN2L depletion triggers a delayed phase shift [

68], so the function of these two ribonucleoproteins may be complementary or antagonistic.

Clearly pathogenic mutations in patients have not been documented for ATXN2L so far, and only very few studies have been dedicated to mammalian ATXN2L. It conserves the classical domain combination Lsm-LsmAD-PAM2, but has a PRM and a MPL binding region at its N-terminus [

72], and an additional Pat1 homology sequence at its C-terminus (which is absent from ATXN2 [

62]). Pat1 proteins usually interact with the cytosolic Lsm1-7 ring to promote deadenylation-dependent decapping and degradation of 3’ UTR AU-rich mRNAs in P-bodies [

73,

74,

75,

76], but can undergo nuclear relocation to Cajal bodies / speckles upon stress and interact with the nuclear Lsm2-8 ring complexed with U6 snRNA to promote splicing [

77,

78,

79], having a prominent role for the growth of synaptic terminals [

80]. ATXN2L can localize to nuclear splicing speckles [

62], and its nuclear localization depends on its PRMT1-dependent arginine methylation [

81]. Its normally cytosolic distribution shows more perinuclear concentration than ATXN2 [

82]. Upon constitutive knock-out of

Atxn2l exons 5-8 with subsequent frameshift in mouse, the homozygous offspring suffers from mid-gestational embryonic lethality, with brain neuronal lamination defects and apoptosis [

83]. In proteome profiles of murine embryonic fibroblasts, ATXN2L loss results in similarly strong deficits of the RNA processing factor NUFIP2 and the nuclear envelope factor SYNE2, and both proteins are interactors of ATXN2L [

82], but it remains unclear which protein dysregulations mediate the preferential ATXN2L impact on neural tissue.

Here, we generated the first mouse line with floxed Atxn2l for conditional manipulations, where an N-terminal fragment of ATXN2L with the Lsm domain may still exist but the remaining protein is ablated, to obtain an initial understanding of the impact of ATXN2L deficiency on adult neurons at behavioural, cellular and molecular level.

2. Materials and Methods

Mouse Breeding and Genotyping

All mouse experiments were in conformity with the German Animal Welfare Act, the Council Directive of 24th November 1986 (86/609/EWG) with Annex II, and the ETS123 (European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals). All mice were housed at the Central Animal Facility (ZFE) of Goethe University Medical School, kept in individually ventilated cages with nesting material at a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, with appropriate temperature and humidity conditions, and provided with food and water ad libitum. Breeding of heterozygous carriers was used for colony expansion and maintenance. Mutant and wildtype (WT) animals of the same sex were selected and aged together in the same cages for subsequent experimental group comparisons. Both female and male mice were used during all experiments. The study was ethically assessed by the Regierungs-präsidium Darmstadt, with approval number V54-19c20/15-FK/2032.

The analysis of Ataxin-2-like isoforms, and the subsequent development of an Atxn2l conditional knock-out (cKO) mouse line in the C57BL/6 genetic background by homologous recombination, was outsourced to the company Genoway (Lyon, France). The targeting vector was designed using the sequences from Mus musculus strain C57BL/6J chromosome 7, GRCm39, NC_000073.7, nucleotide positions 126075978 to 126115977. Sperm from the successfully floxed Atxn2l mice was deposited at Genoway. The software SnapGene (Boston, MA, USA, Version 8.0.2) was used for structural analysis and primer generation.

To trigger the

Atxn2l-KO constitutively, mice with targeted insertion of flox sites were bred with pan-Cre deleter mice to obtain heterozygous

Atxn2l-KO mice for intercrosses. To trigger the

Atxn2l-cKO selectively in CamK2a-positive cells, homozygous

Atxn2l-flox mice were crossed with CamK2a-Cre/ERT2 mice (B6;129S6-Tg(CamK2a-Cre/ERT2)1Aibs/J, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). Resulting double mutants that were heterozygous for

Atxn2l-flox and expressed Cre recombinase (

Atxn2l-WT/flox, CamK2a-Cre/ERT2-Tg) were then crossed with homozygous

Atxn2l-flox mice to generate homozygous

Atxn2l-flox mice with transgenic Cre (Cre-Tg). Homozygous

Atxn2l-flox mice without Cre served as littermate controls. All genotyping primers are provided in

Table S1.

For genotyping of the floxed

Atxn2l, DNA from ear tissues was extracted using the hot shot method [

84], performing the PCR with 1 µl of DNA in a reaction mix with AmpliTaq (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The PCR conditions were 3 min at 94 °C, 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94 °C, 30 sec at 65 °C, and 30 sec at 72 °C, followed by 5 min at 72 °C. The expected bands were 315 bp for the WT allele and 405 bp for the floxed allele.

For genotyping of the Cre transgene, a touchdown PCR was performed as recommended by the Jackson website (

https://www.jax.org/Protocol?stockNumber=012362&protocolID=27167, last accessed on 6 June 2024). 5 min at 94 °C were followed by 10 cycles with a decrease of 0.5 °C per cycle with 30 sec at 94 °C, 30 sec at 65 °C and 30 sec at 68 °C. This was followed by 28 cycles of 30 sec at 94 °C, 30 sec at 60 °C and 30 sec at 72 °C with 7 min at 72 °C at the end. The expected band sizes were 521 bp for the control, and 200 bp for the presence of Cre.

For genotyping of the Atxn2l-KO, the PCR conditions were 3 min at 94 °C, 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94 °C, 30 sec at 66 °C, and 30 sec at 72 °C, followed by 5 min at 72 °C. The expected bands were 151 and 3808 bp for the WT allele and 276 bp for the KO allele.

Assessment of Embryonic Lethality in Constitutive Atxn2l-KO Mice

After excision of the neo cassette and the floxed region in vivo, 2 heterozygous mice with constitutive deletion of Atxn2l exons 10-17 were obtained, which were then crossed with C57BL/6 mice to generate a colony. Multiple breeding units of male and female heterozygotes were used to analyze the offspring for the viability of Atxn2l-KO mice and the distribution of heterozygous versus WT animals among the offspring. In total, 100 litter pups were produced and genotyped.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial frontal sections of 50 µm in thickness were cut using a vibratome (Leica VT 1000 S Leica, Wetzler, Germany), and collected in PBS. Individual sections were incubated in a blocking solution (10% normal goat serum (NGS), 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) at RT for 2 h. Afterwards, sections were incubated over night at RT in primary antibodies (rabbit-anti-ATXN2L, 1:300, Proteintech Cat# 24822-1-AP, RRID: AB_2879743; mouse-anti-CAMK2a, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-70492, RRID: AB_1119957) diluted in antibody solution (5% NGS, 0,2% Triton X-100 in PBS). Sections were washed three times (PBS, 10 min each), then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies diluted in antibody solution (goat-anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568, 1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-11036, RRID: AB_10563566; goat-anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488, 1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-11029, RRID: AB_2534088) in the dark. Sections were then washed three times in PBS for 10 minutes, with the second wash containing the nuclear stain Hoechst (1:5000). Finally, sections were mounted on glass slides with mounting medium (Dako/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Imaging

Fluorescent widefield overview images were acquired with an IXplore Live IX83 LED (Evident) using a 4x objective (UPlanXApo, NA 0.16). Higher-magnification images were acquired with a Nikon C2si laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 20x objective (Plan Apo, NA 0.75) at a resolution of 1024x1024 pixels, using a 2x average. Images of control and cKO brains were acquired with equal exposure times / laser and gain settings. Brightness and contrast of the overview images in Figure 3A were post-hoc adjusted in FIJI [

85] (RRID: SCR_002285) for visualization purposes, adjustments were equally applied to control and cKO images.

Locomotor Phenotyping

Assessment of spontaneous movements was done in an open field apparatus (Versamax, Omnitech, Columbus, OH, USA), placing tamoxifen-treated

Atxn2l-flox versus

Atxn2l-flox/Cre mice at monthly intervals simultaneously into the 20x20 cm chambers, recording their activity by infra-red beams during 5 min trials and interrogating predefined parameters for alterations with consistency over time, as previously described [

61].

Atxn2l-flox / Cre-Tg animals were injected with TAM to induce the conditional KO (

Atxn2l-cKO), in parallel with

Atxn2l-flox mice that lacked Cre and served as controls (

Atxn2l-flox /Cre-WT).

Tamoxifen Preparation and Treatment

A tamoxifen solution (20 mg/ml) was prepared from 200 mg of tamoxifen powder (Sigma-Aldrich #T5648, USA) and reconstituted in 10 ml of peanut oil (Sigma-Aldrich #P2144, USA). Tamoxifen was dissolved directly in peanut oil at room temperature with vertical rotation overnight and eventual vortexing. Mice were weighed before the first injection, and the volume to be injected was calculated for a tamoxifen dose of 75 mg/kg body weight. Intraperitoneal tamoxifen injections were applied on five consecutive days, using 0.3 ml syringes and 30-gauge x 8 mm needles (Becton, Dickinson and Co. #324826, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Global Proteomics

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, their brain regions dissected and frozen in liquid nitrogen, to be stored at -80 °C and then shipped on dry ice. Eight left frontal cortex samples (4

Atxn2l-cKO versus 4

Atxn2l-flox / Cre-WT) were homogenized under denaturing conditions with a FastPrep (once for 60 s, 4.5 m x s-1) in 800 µL of fresh buffer containing 3 M guanidinium chloride (GdmCl), 10 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 20 mM chloroacetamide, and 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5. Lysates were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, shaken at 1000 rpm in a thermal shaker, and sonicated in a water bath for 10 min. Supernatants were transferred into new 1.5 ml protein low-binding tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The protein concentration of each sample was measured with a BCA protein assay kit (23252, Thermo Scientific, USA). 500 ng of each sample was diluted with a dilution buffer containing 10% acetonitrile and 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, to reach a 1 M GdmCl concentration. Then, proteins were digested with LysC (Roche, Basel, Switzerland; enzyme to protein ratio 1:50, MS-grade) shaking at 800 rpm at 37 °C for 3.5 h. The digestion mixture was diluted again with water to reach 0.5 M GdmCl, followed by tryptic digestion (Roche, enzyme to protein ratio 1:50, MS-grade) and incubation at 37 °C overnight in a thermal shaker at 800 rpm. Peptides were acidified with formic acid to a final concentration of 2%, and the digests were loaded onto Evotip Pure (Evosep, Odense, Denmark) tips according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Peptide separation was carried out by nanoflow reverse phase liquid chromatography (Evosep One, Evosep) using the Aurora Elite column (15 cm x 75 µm ID, C18 1.7 µm beads, IonOpticks, Victoria, Australia) with the 20 samples a day method (Whisper zoom 20-SPD). The LC system was online coupled to a timsTOF Ultra 2 mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) applying the data-independent acquisition (DIA) with parallel accumulation serial fragmentation (PASEF) method. MS data were processed with Dia-NN (v2.0) and searched against a library of in silico predicted mouse spectra. The "match between runs" feature was used. The mass spectrometry data have been deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium (

http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository [

86] with the data set identifier PXD064497.

Proteome Interrogation for Pathway Enrichments

The webserver of STRING version 12 (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) (

https://string-db.org/) was employed to assess the proteome profile in automated manner for any enrichments in protein-protein interactions, Gene Ontology (GO) terms, Reactome and KEGG pathways, subcellular localizations, and protein motifs [

87]. In addition, to maximize bioinformatics insights, the three

Atxn2l-flox / Cre-WT samples with highest values and the three

Atxn2l-cKO samples with lowest values for ATXN2L abundance (reduction to 70% of controls) were compared for significant dysregulations in the proteome. The resulting list of proteins was visualized as volcano plot, and studied in STRING regarding ATXN2L-dependent interactomes.

Statistics and Graphical Presentation

Unpaired Student t-tests with Welch’s corrections were used to establish comparisons for continuous variables between homozygous Atxn2l-cKO and floxed WT animals. Mean values and variance as standard error of the means (SEM), as well as linear regression lines were used for behavior data visualization. GraphPad (Version 10.4.1, for Windows, GraphPad Prism, Boston, MA) software was used for all statistical analyses and Volcano plot generation. Significance was assumed at p<0.05 and highlighted with asterisks: *p<0.05.

3. Results

Generation of Conditional KO Mice via Floxing Exons 10-17 in the Atxn2l Gene

To bypass the embryonic lethality of the constitutive ATXN2L-null genotype and to achieve ATXN2L absence selectively in neural tissue during adult life, we generated the first

Atxn2l-cKO mouse strain. The initial bioinformatic characterization of the murine

Atxn2l gene revealed 22 exons (

Figure 1A), with ATG initiation codons in exons 1 and 2, stop codons in exon 22, translating into one experimentally validated protein with 1049 amino acids, as well as protein isoforms containing 1074, 994, or 1043 amino acids (analyzing the database mRNA/protein entries GenBank BC054483 / UniProt Q7TQH0-1, GenBank AK155062 / UniProt Q7TQH0-2, GenBank AK168745 / NCBI NP_001334587, and isoform 4 derived from UniProt entry Q7TQH0-3). The variants showed N-terminal differences regarding the Proline-rich motif (PRM), while the N-terminal potential MPL-interaction region [

72] was common to all (

Figure 1A). The phylogenetically conserved sequences were always present, including the (i) Lsm domain involved in RNA binding, (ii) LsmAD sequence (where a clathrin-mediated trans-Golgi signal and an ER exit signal as well as a putative capsase cleavage site DxxD were reported), and (iii) PABP-interaction motif PAM2 involved in mRNA turnover regulation. The ATXN2L variants showed differences at the C-terminus, where sequence homology exists with the Pat1 protein family [

62].

In order to flank

Atxn2l exons 10 and 17 with loxP sites, thus enabling the selective deletion of a 3.3 kb fragment containing the LsmAD sequence and the PAM2 motif, with a consequent frameshift that eliminates the C-terminal sequences, a targeting vector was generated in mouse C57BL/6 genetic background. To drive efficient homologous recombination screens, this vector contained a neomycin-selection cassette with flanking RoxP sites between exons 9 and 10 as positive selection marker, with murine isogenic

Atxn2l genomic sequences comprising a short arm from exon 8, and a long arm extending beyond exon 22, together with diphtheria toxin fragment A as negative selection marker (

Figure 1B). Optimal screening methodology by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was validated to (i) detect 5’ homologous recombination events, (ii) distinguish the wild-type, the recombined, the neo-excised and the Cre-excised alleles, as well as (iii) establish mouse genotypes (

Figure 1B). After PCR identification of 3 ES cell clones with integration of the neomycin cassette in heterozygous state, and full sequencing into the surrounding locus for confirmation of genomic integrity, blastocyst injection generated 3 chimeric males with chimerism rate above 50%. Three heterozygous floxed and (after crossbreeding with pan-Cre deleter mice) three heterozygous constitutive mice were derived, with a second PCR screening being performed to verify neo- and Cre-mediated excision events, followed by additional sequencing of the genomic locus. This approach generated 14 heterozygous floxed animals (7 males and 7 females), and 5 heterozygous constitutive KO mice (2 males, 3 females) in the F1 generation, which were interbred to generate F2 generations of the floxed conditional KO (

Atxn2l-cKO) strain and the constitutive KO (

Atxn2l-KO) strain of heterozygous breeders.

Crossbreeding with Constitutive Cre-Deleters Confirms Embryonic Lethality of Homozygous ATXN2L-Null Mice

To assess if the

Atxn2l exon 10-17 deletion event causes embryonic lethality, similar to the previously reported [

83] constitutive

Atxn2l exon 5-8 deletion where also the Lsm domain is missing (in addition to the absence of LsmAD / PAM2 / Pat1 homology sequences in the current exon 10-17 strain), cross-breeding between heterozygous constitutive KO animals was performed. Among >100 collected offspring genotypes, no postnatal ATXN2L-null homozygote was observed (

Table 1), in good agreement with the notion that embryonic lethality occurred again, despite the difference in targeted exons.

Crossbreeding with CamK2a-Dependent Cre/ERT2 Mice and Subsequent Tamoxifen Injection Generates Atxn2l-cKO in Adult Frontal Cortex Tissue

To achieve the deletion of

Atxn2l selectively in CamK2a-positive neurons postnatally at early adult age,

Atxn2l-flox mice in homozygosity were obtained that differed regarding the heterozygous presence or absence of transgenic CamK2a-Cre/ERT2. Both had tamoxifen administered intraperitoneally during 5 consecutive days at ages of 2-3 months (

Figure 2A). Their locomotor behaviour was documented regularly until the age of 9 months, before tissues were dissected for further analyses (

Figure 2B). PCR analyses at the DNA level in ear punches (

Figure 2C) and at the RNA level in frontal cortex (

Figure 2D) confirmed the desired flox / Cre genotypes and revealed the successful

Atxn2l deletion.

Atxn2l-cKO in Frontal Cortex Tissue Showed Mosaic Expression in CamK2a-Positive Neurons

To obtain a first impression of the cellular pattern of ATXN2L loss in the frontal cortex, immunofluorescence labeling for ATXN2L and CamK2a was employed. Serial brain sections of 2 cKO and 2 floxed WT mice (one WT brain was discarded after postmortal genotyping) were cut from olfactory bulb to hippocampus. ATXN2L immunoreactivity was missing from many but not all CamK2a-positive neurons of cKO frontal cortex (

Figure 3) and hippocampus (not shown), supporting the notion that this transgenic CamK2a-Cre/ERT2 line or the tamoxifen dosage employed were driving a weak Cre expression resulting in a mild chimeric deletion only in part of the target cells. The observations in the brains investigated also indicate that ATXN2L deletion does not appear to cause widespread cell death or strong dedifferentiation of adult neurons even after a period of >6 months.

CamK2a-Dependent Atxn2l-cKO Triggers Deficits of Spontaneous Horizontal Locomotion

To assess whether the absence of ATXN2L from CamK2a+ neurons of the frontal cortex affects exploratory behaviour, the spontaneous locomotor activity of mice after TAM injection was quantified in an open field paradigm after tamoxifen injection at monthly intervals from the age 3 until 9 months. The two weeks immediately after drug administration were exempted because the animal handling with repeated intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen dissolved in oil can transiently trigger discomfort or even peritonitis, resulting in a wide variability of behavior. The average spontaneous mobility parameters for cKO usually showed similar or lower values than floxed WT mice (except rest and stereotypy time), with consistent significant decreases for the parameter ambulatory time at 8 and 9 months (

Figure 4). Overall, the data indicate that the chimeric dose reduction of ATXN2L in CamK2a+ neurons of the frontal cortex was sufficient to alter curiosity and/or anxiety levels.

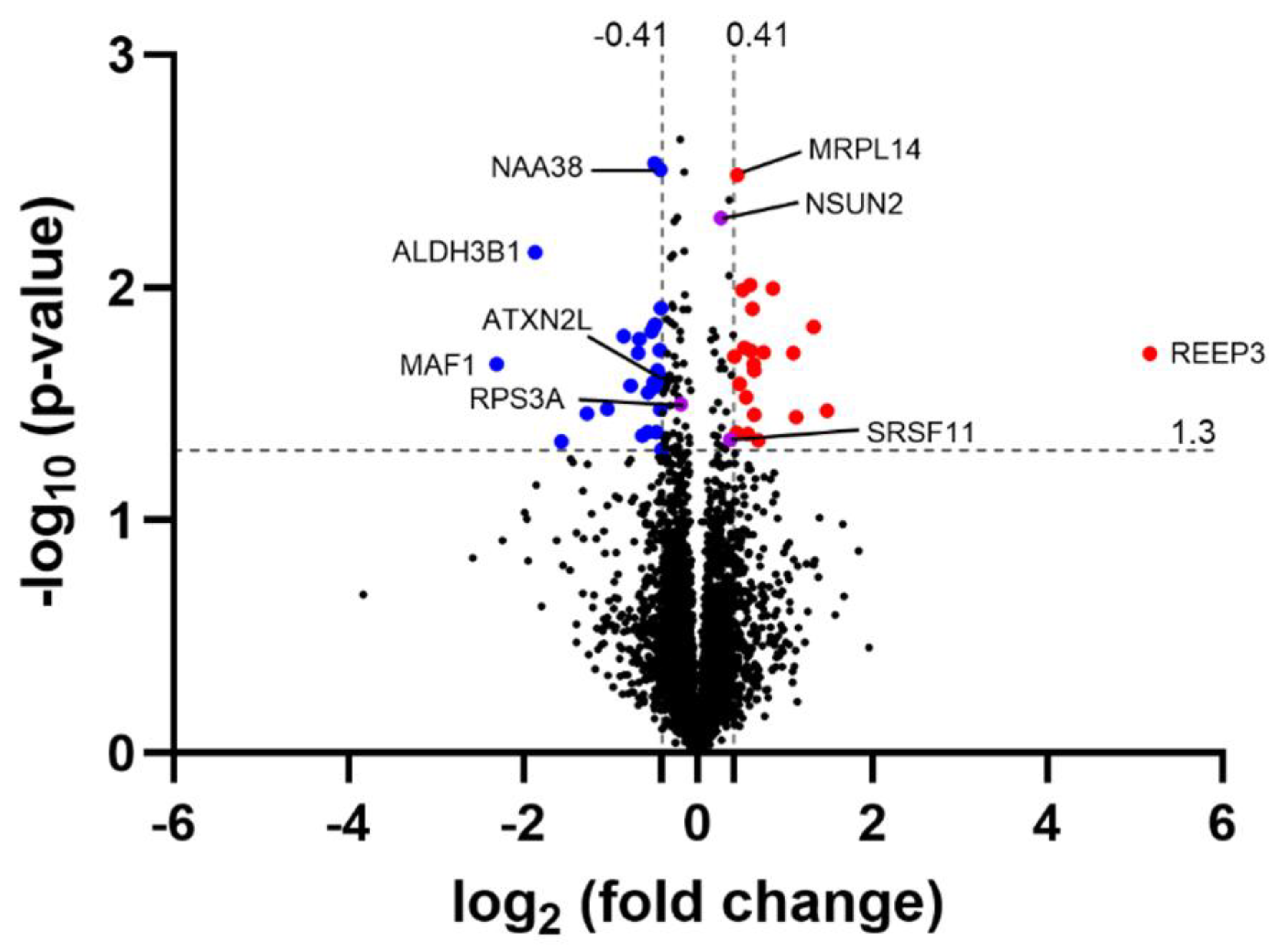

CamK2a-Dependent Atxn2l-cKO Mouse Frontal Cortex Proteomics Shows ATXN2L Protein Reduction to 75% and Dysregulation of Alternative Splicing Pathway

To elucidate the molecular consequences of the ATXN2L-cKO in adult nervous tissue, samples from several important brain regions (olfactory bulb, frontal cortex, striatum, hippocampus, septum, tectum, cerebellum) were analysed by label-free mass spectrometry to quantify their global proteome profiles. In frontal cortex, average ATXN2L protein abundance showed a decrease to 75% in the four samples with nominal significance, after the tamoxifen-activated, Cre-mediated deletion events in CamK2a-positive neurons at ages >9 months (

Figure 5,

Table S1). Given that ATXN2L is physiologically present not only in these neurons, but also in other neurons, glia, endothelial and blood cells where no deletion is expected in our experiment, this quantification result is credible. The two proteins with massive ATXN2L dependence in murine embryonic fibroblasts, NUFIP2 as RNA processing factor and SYNE2 as bridge between nuclear envelope and microtubules, did not display dysregulated levels (

Table S1). In this complete analysis of four cKO samples, the strongest downregulation was observed for MAF1 as repressor of RNA polymerases and the U6 snRNP as well as ribosomal translation apparatus, which is under control of mTOR growth signalling [

88]. Even more significant downregulation was observed for ALDH3B1 as a factor that protects medium-/long-chain fatty acids from lipid peroxidation. The strongest upregulation was documented for REEP3 as bridge between the endoplasmic reticulum with microtubules that ensures nuclear envelope architecture [

89,

90].

In view of this mild decrease of ATXN2L levels upon CamK2a-dependent deletion, the downstream consequences would be too subtle for immunoblot analyses, so only systematic bioinformatics surveys with alternate approaches could be conducted.

STRING interaction and enrichment analysis revealed that protein dysregulations occurred with strongest enrichment in dendrites (false discovery rate FDR = 4.07e-08), for cytoskeleton binding proteins (FDR = 4.36e-05), and factors with rapid regulation by phosphorylation (FDR = 2.50e-07), acetylation (FDR = 1.05e-05), and alternative splicing (FDR = 9.61e-05). The only enriched protein motifs were pleckstrin homology domains (FDR = 0.04), which mediate binding to inositol lipids. As single ATXN2L interactor with significantly dysregulated levels, NAA38 was reduced to 74% with nominal significance. NAA38 is a member of the snRNP family of Lsm domain-containing proteins, which serves as auxiliary component of the N-terminal acetyltransferase C (NatC) complex that acts after ribosomal translation in the cytosol.

Other dysregulated RNA processing proteins with nominal significance (both in the complete analysis of 4 cKO versus 4 floxed WT samples and in the enrichment analysis of selected 3 cKO with lowest ATXN2L levels versus 3 floxed WT with highest levels) included the nuclear splicing factor SRSF11, the RNA cytosine C(5)-methyltransferase NSUN2, as well as RPS3 and MRPL14 as ribosomal subunits in the cytosol and the mitochondria, respectively.

Upon assessment of consistencies between frontal cortex and hippocampal proteome profiles, upon normalization either among multiple brain regions or normalization among these two regions with maximal ATXN2L depletion, an enrichment of the cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein granule factors with dysregulations of nominal significance stood out (FDR = 0.0125), involving decreases of ATXN2L and AGO3, versus increases of LSM3, EDC4, FXR2, NSUN2, LARP7 and SRSF11.

Overall, the mild CamK2a-dependent Atxn2l-cKO in frontal cortex enabled preliminary insights into the alterations of neural ribonucleoproteins and pathways that underlie the phenotypic deficits of spontaneous locomotion.

4. Discussion

Although mutations of the less abundant ATXN2 and the more abundant ATXN2L have a preferential impact on neural tissues, with their distorted functions making causal contributions to the adult neurodegenerative diseases SCA2 and ALS, so far no mammalian model was available where ATXN2L mutation effects can be studied in adult neurons. Furthermore, the primary protein/RNA interactions of ATXN2L in adult mammalian neurons are currently not documented. Moreover, the exact physiological role of ATXN2L in RNA processing remains to be identified, both during growth periods when its subcellular distribution shows perinuclear concentration, and in periods of cell damage when its redistribution to stress granules suggests its involvement in quality control and repair.

Here, we generated the first

Atxn2l-cKO mouse line, via genetic ablation of exons 10-17 with subsequent frameshift, which results in ATXN2L N-term translation to be interrupted before the LsmAD and PAM2 domains, and the C-terminal Pat1-homology region. Upon constitutive Cre-mediated deletion in homozygosity, embryonic lethality ensued as previously reported for the

Atxn2l exon 5-8 deletion with frameshift [

83]. Upon conditional CamK2a-Cre/ERT2-mediated deletion in frontal cortex neurons via tamoxifen injection at the adult ages of 2-3 months, and subsequent aging until 9-12 months, cell death was not observed in CamK2a-positive neurons with complete absence of ATXN2L. However, altered curiosity and/or anxiety was observed in response to the altered signalling of these neurons upon ATXN2L absence. Analyses of the global proteome of frontal cortex (and hippocampus) from

Atxn2l-cKO mice confirmed a reduction of ATXN2L protein to 75% abundance, and weak downstream alterations in the alternative splicing pathway and in the cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein granule composition. While ATXN2L protein is mainly cytoplasmic, it therefore appears to control the surveillance and triage of alternatively spliced isoforms, which need rapid turnover upon stressors or upon stimuli. This notion about ATXN2L Lsm and LsmAD effects are in excellent agreement with the well-established function of nuclear Sm domains for alternative splicing [

91] and of cytosolic Lsm1-7 rings for balancing mRNA translation versus turnover [

92].

Our observation of chimeric or mosaic deletions upon CamK2a-driven Cre/ERT2 expression and tamoxifen administration was reported previously [

93,

94,

95,

96]. Similarly, altered curiosity-driven exploration and/or anxiety is an expected feature upon frontal cortex dysfunction [

97,

98,

99]. Furthermore, an impact on alternative splicing was previously shown for mutations in TDP-43, FMR1, NUFIP2 and G3BP2 [

100,

101,

102,

103], as ATXN2/ATXN2L ribonucleoprotein interactors and stress granule components [

82]. Thus, the results in the new

Atxn2l-cKO mouse are in line with previous work.

The main limitations of this study derive from the choice of the CamK2a promoter to drive a weak Cre expression selectively in frontal cortex and hippocampus. Given that Cre transgene expression is weak under control of the CamK2a promoter, the ATXN2L depletion was mild in the current project, and the downstream proteome dysregulations were too subtle for validation by independent techniques such as immunoblots and quantitative RT-qPCR. Therefore, a next round

Atxn2l-cKO experiments could be driven by a strong promoter with specificity for forebrain and hippocampus projection neurons, such as the NEX-Cre transgene [

104], to maximize the effect sizes of downstream proteome dysregulations. While the affection of frontal cortex and hippocampus are unlikely to restrict the survival of mouse mutants, thus providing a safe opportunity to assess the viability of ATXN2L depletion in adult neurons, future experiments should also target motor neurons, cerebellar neurons, or brainstem neurons, which are more critical and correspond to the neural circuits affected in ALS and SCA2. All current mass spectrometry findings have to be regarded as preliminary, given that no single result achieved actual significance, and the findings varied in dependence on tamoxifen efficacy in different animals, diverse brain region, and normalization approaches. However, it was intriguing to identify both NAA38 and LSM3 among the nominally significant dysregulations, given that ATXN2L and both factors mentioned are members of the Lsm protein family, and that LSM12 was previously reported as ATXN2L interactor [

82]. The mainly nuclear ribonucleoproteins NSUN2 and SRSF11 were also quite consistently dysregulated, indicating that ATXN2L depletion leads to adaptations of nuclear RNA processing. NSUN2 acts with ALYREF and ATXN2 interactor YBX1 to bind m5C-mRNAs and modify their nuclear export [

105,

106]. SRSF11 (also known as p54 or SRp54) always resides at the spliceosome [

107,

108], acting as constitutive splicing factor, but associates with U2AF65 unlike the remaining SR family [

109], and its specific functions include the splicing of small introns [

110] and of neuronal microexons [

111].

Overall, this project generated the first mammalian conditional Atxn2l deletion strain, providing proof-of-concept that it constitutes a useful tool for future analyses of ATXN2L physiological functions in adult brain, where they have selective importance for neuronal responses to stress and stimuli.

5. Conclusions

The present study generated the first mouse strain with conditional deletion of ATXN2L, providing evidence that (i) complete absence of ATXN2L is incompatible with embryonic development, while (ii) in adult mice the chimeric removal of ATXN2L protein levels from half of CamK2a-positive frontal cortex neurons triggers reduced spontaneous locomotion and dysregulated protein levels in the alternative splicing pathway.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: primers used for genotyping; Table S2: Proteome Frontal Cortex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and G.A.; methodology, J.K., L.-E.A.-M., A.R.K., M.F., S.G., G.K., D.M., T.D.; validation, L.-E.A.-M. and A.R.K.; formal analysis, J.K., L.-E.A.-M., D.M. and G.A.; investigation, J.K., L.-E.A.-M., S.G., D.M., M.F., G.A.; resources, D.M., T.D. and G.A.; data curation, J.K., D.M. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., L.E.A.-M. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, J.K., L.-E.A.-M., A.R.K., M.F., D.M., T.D. and G.A.; visualization, J.K., L.-E.A.-M., A.R.K., M.F., D.M. and G.A.; supervision, S.G., D.M., and G.A.; project administration, G.A.; funding acquisition, D.M. and G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG AU96/21-1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt (V54-19c20/15-FK/1083, on 11 March 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All proteome data were deposited in PRIDE with accession number PXD064497.

Acknowledgments

The invaluable advice and support from Ann-Carol Eberle, Delphine Cartier, Patricia Isnard-Petit, and Kader Thiam at Genoway (Lyon, France) in the generation of conditional ATXN2L-null mice made this project possible. We thank Beata Lukaszewska-McGreal for proteome sample preparation and the Max Planck Society for support, as well as the ZFE staff at Goethe University Frankfurt Medical School for their animal care.

Conflicts of Interest

Thomas Deller received honoraria from Novartis for lectures on human brain anatomy. All other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGO3 |

Argonaute RISC Catalytic Component 3 |

| ALDH3B1 |

Medium-Chain Fatty Aldehyde Dehydrogenase |

| ALS |

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| ALYREF |

Aly/REF export factor |

| ATG |

Autophagy-related gene |

| ATX |

Ataxin |

| ATXN2 |

Ataxin-2 |

| ATXN2L |

Ataxin-2-like |

| AU-rich |

Adenosin-Uridine rich |

| BCA |

Bicinchoninic Acid |

| bp |

base pairs |

| CAG |

Cytosine–Adenine–Guanine trinucleotide repeat |

| CamK2a |

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha |

| cKO |

conditional Knock-Out |

| Cre |

Cyclization recombination enzyme |

| DEAD |

Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp (DEAD-box helicase family) |

| DIA |

Data-independent acquisition |

| DNA |

Deoxyribo-Nucleic Acid |

| DTA |

Diphtheria toxin fragment A |

| DxxD |

Aspartate – any amino acid – any amino acid - Apartate |

| EDC4 |

Enhancer Of mRNA Decapping 4 |

| EGF |

Epidermal Growth Factor |

| ER |

Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERT2 |

Tamoxifen-inducible estrogen receptor domain, improved version |

| ES |

Embryonic Stem Cells |

| FDR |

False Discovery Rate |

| FEBS |

Federation of European Biochemical Societies |

| FIJI |

FIJI Is Just ImageJ |

| floxed |

sequence flanked by two loxP sites |

| FMRP |

Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein |

| FMR1 |

Fragile X Messenger Ribonucleoprotein 1 |

| FXR2 |

Fragile X Mental Retardation, Autosomal Homolog 2 |

| GO |

Gene Ontology |

| G3BP2 |

GTPase Activating Protein (SH3 Domain) Binding Protein 2 |

| hATXN2 |

human Ataxin-2 |

| het |

heterozygous |

| hom |

homozygous |

| HSC |

Hematopoietic Stem Cell |

| kb |

kilo-bases |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KO |

Knock-Out |

| LARP7 |

La Ribonucleoprotein 7, Transcription Regulator, binds U6 snRNA |

| LC |

Liquid Chromatography |

| LED |

Light Emitting Diode |

| LoxP |

Locus of X-over (crossing-over) in bacteriophage P1 |

| Lsm |

Like-Sm domain |

| LsmAD |

Like-Sm associated domain |

| LSM3 |

LSM3 Homolog, U6 Small Nuclear RNA Associated |

| MAF1 |

MAF1 Homolog, Negative Regulator Of RNA Polymerase III |

| MPL |

Myelo-Proliferative Leukaemia Protein |

| mRNA |

messenger Ribo-Nucleic Acid |

| MRPL14 |

Large Ribosomal Subunit Protein UL14m |

| MS |

Mass Spectrometry |

| mTOR |

mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| mTORC1 |

mechanistic Target of Rapamycin-Complex associated protein 1 |

| m5C |

5-methyl-Cytosine |

| NAA38 |

N-Alpha-Acetyltransferase 38, NatC Auxiliary Subunit |

| NGS |

Normal goat serum |

| NSUN2 |

NOP2/Sun RNA Methyltransferase 2 |

| NUFIP2 |

Nuclear Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Interacting Protein 2 |

| oligo(U) |

several (Uridine bases) |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PABP |

Poly(A)-Binding Protein |

| PAM2 |

Poly(A)-Binding protein association Motif type 2 |

| PASEF |

Parallel Accumulation Serial Fragmentation |

| Pat1 |

yeast factor for protection of mRNA 3'-UTRs from trimming |

| P-bodies |

processing bodies in the cytosol, where RNA is degraded |

| Pbp1 |

Poly(A)-binding protein 1 in yeast |

| PBS |

Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| Poly(A) |

many (Adenine bases) |

| polyQ |

many Glutamine amino acids |

| PRM |

Proline-rich motif |

| REEP3 |

Receptor Expression-Enhancing Protein 3 |

| RNA |

Ribo-Nucleic Acid |

| RNP |

Ribo-Nucleoprotein |

| RoxP |

loxP-analogous site, recognized by phage integrase Dre |

| RPS3 |

Small Ribosomal Subunit Protein US3 |

| RRM |

RNA Recognition Motif |

| rRNA |

ribosomal Ribo-Nucleic Acid |

| RT |

Reverse Transcription |

| SCA2 |

Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 2 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SEM |

Standard Error of the Mean |

| SG |

Stress Granule |

| siRNA |

Small Interfering RNA |

| SN |

Substantia Nigra |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| snRNA |

small nuclear Ribo-Nucleic Acid |

| snRNP |

small nuclear Ribo-Nucleic-Acid binding protein |

| SR |

Serine/Arginine-rich protein, family of splicing factors |

| SRSF11 |

Serine And Arginine Rich Splicing Factor 11 |

| SYNE2 |

Spectrin Repeat Containing Nuclear Envelope Protein 2 |

| TAM |

Tamoxifen |

| TDP-43 |

TAR DNA-Binding Protein-43 |

| Tg |

Transgenic |

| tRNA |

transfer Ribo-Nucleic Acid |

| UPR |

Unfolded Protein Response |

| UTR |

un-translated region of mRNA |

| U2AF65 |

U2 Small Nuclear RNA Auxiliary Factor 2 |

| WB |

Western Blot |

| WT |

Wild-Type |

| YBX1 |

Y-Box-Binding Protein 1, CCAAT-Binding Transcription Factor I |

| ZFE |

Zentrale Forschungseinrichtung (Central Animal Facility) |

References

- Achsel, T., H. Stark, and R. Luhrmann, The Sm domain is an ancient RNA-binding motif with oligo(U) specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001. 98(7): p. 3685-9. [CrossRef]

- Tharun, S., et al., Yeast Sm-like proteins function in mRNA decapping and decay. Nature, 2000. 404(6777): p. 515-8. [CrossRef]

- Mura, C., et al., Archaeal and eukaryotic homologs of Hfq: A structural and evolutionary perspective on Sm function. RNA Biol, 2013. 10(4): p. 636-51.

- Swisher, K.D. and R. Parker, Localization to, and effects of Pbp1, Pbp4, Lsm12, Dhh1, and Pab1 on stress granules in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One, 2010. 5(4): p. e10006. [CrossRef]

- Seidel, G., et al., Quantitative Global Proteomics of Yeast PBP1 Deletion Mutants and Their Stress Responses Identifies Glucose Metabolism, Mitochondrial, and Stress Granule Changes. J Proteome Res, 2017. 16(2): p. 504-515. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S., et al., Yeast Ataxin-2 Forms an Intracellular Condensate Required for the Inhibition of TORC1 Signaling during Respiratory Growth. Cell, 2019. 177(3): p. 697-710 e17. [CrossRef]

- Kato, M., et al., Redox State Controls Phase Separation of the Yeast Ataxin-2 Protein via Reversible Oxidation of Its Methionine-Rich Low-Complexity Domain. Cell, 2019. 177(3): p. 711-721 e8. [CrossRef]

- Kiehl, T.R., H. Shibata, and S.M. Pulst, The ortholog of human ataxin-2 is essential for early embryonic patterning in C. elegans. J Mol Neurosci, 2000. 15(3): p. 231-41. [CrossRef]

- Ciosk, R., M. DePalma, and J.R. Priess, ATX-2, the C. elegans ortholog of ataxin 2, functions in translational regulation in the germline. Development, 2004. 131(19): p. 4831-41. [CrossRef]

- Bar, D.Z., et al., Cell size and fat content of dietary-restricted Caenorhabditis elegans are regulated by ATX-2, an mTOR repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(32): p. E4620-9. [CrossRef]

- Stubenvoll, M.D., et al., ATX-2, the C. elegans Ortholog of Human Ataxin-2, Regulates Centrosome Size and Microtubule Dynamics. PLoS Genet, 2016. 12(9): p. e1006370. [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, U., et al., Conserved role for Ataxin-2 in mediating endoplasmic reticulum dynamics. Traffic, 2019. 20(6): p. 436-447. [CrossRef]

- Beath, E.A., et al., Katanin, kinesin-13, and ataxin-2 inhibit premature interaction between maternal and paternal genomes in C. elegans zygotes. Elife, 2024. 13.

- Satterfield, T.F., S.M. Jackson, and L.J. Pallanck, A Drosophila homolog of the polyglutamine disease gene SCA2 is a dosage-sensitive regulator of actin filament formation. Genetics, 2002. 162(4): p. 1687-702. [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, T.F. and L.J. Pallanck, Ataxin-2 and its Drosophila homolog, ATX2, physically assemble with polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet, 2006. 15(16): p. 2523-32. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ramahi, I., et al., dAtaxin-2 mediates expanded Ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of SCA1. PLoS Genet, 2007. 3(12): p. e234. [CrossRef]

- McCann, C., et al., The Ataxin-2 protein is required for microRNA function and synapse-specific long-term olfactory habituation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(36): p. E655-62. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. and R. Allada, ATAXIN-2 activates PERIOD translation to sustain circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Science, 2013. 340(6134): p. 875-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., A role for Drosophila ATX2 in activation of PER translation and circadian behavior. Science, 2013. 340(6134): p. 879-82. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakaran, I.P., et al., FMRP and Ataxin-2 function together in long-term olfactory habituation and neuronal translational control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(1): p. E99-E108. [CrossRef]

- Vianna, M.C., et al., Drosophila ataxin-2 gene encodes two differentially expressed isoforms and its function in larval fat body is crucial for development of peripheral tissues. FEBS Open Bio, 2016. 6(11): p. 1040-1053. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., et al., LSM12 and ME31B/DDX6 Define Distinct Modes of Posttranscriptional Regulation by ATAXIN-2 Protein Complex in Drosophila Circadian Pacemaker Neurons. Mol Cell, 2017. 66(1): p. 129-140 e7. [CrossRef]

- Bakthavachalu, B., et al., RNP-Granule Assembly via Ataxin-2 Disordered Domains Is Required for Long-Term Memory and Neurodegeneration. Neuron, 2018. 98(4): p. 754-766 e4. [CrossRef]

- Cha, I.J., et al., Ataxin-2 Dysregulation Triggers a Compensatory Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Decrease in Drosophila C4da Neurons. Mol Cells, 2020. 43(10): p. 870-879. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., et al., Antagonistic roles for Ataxin-2 structured and disordered domains in RNP condensation. Elife, 2021. 10. [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, U., et al., Ataxin-2 is essential for cytoskeletal dynamics and neurodevelopment in Drosophila. iScience, 2022. 25(1): p. 103536. [CrossRef]

- Corgiat, E.B., et al., The Nab2 RNA-binding protein patterns dendritic and axonal projections through a planar cell polarity-sensitive mechanism. G3 (Bethesda), 2022. 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Petrauskas, A., et al., Structured and disordered regions of Ataxin-2 contribute differently to the specificity and efficiency of mRNP granule formation. PLoS Genet, 2024. 20(5): p. e1011251. [CrossRef]

- Auburger, G., et al., Efficient Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases by Depletion of Starvation Response Factor Ataxin-2. Trends Neurosci, 2017. 40(8): p. 507-516. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, D. and P. Guzman, Insights into the evolution and domain structure of Ataxin-2 proteins across eukaryotes. BMC Res Notes, 2014. 7: p. 453. [CrossRef]

- Pulst, S.M., et al., Moderate expansion of a normally biallelic trinucleotide repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nat Genet, 1996. 14(3): p. 269-76. [CrossRef]

- Sanpei, K., et al., Identification of the spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 gene using a direct identification of repeat expansion and cloning technique, DIRECT. Nat Genet, 1996. 14(3): p. 277-84. [CrossRef]

- Imbert, G., et al., Cloning of the gene for spinocerebellar ataxia 2 reveals a locus with high sensitivity to expanded CAG/glutamine repeats. Nat Genet, 1996. 14(3): p. 285-91. [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Perez, L., et al., Saccade velocity is controlled by polyglutamine size in spinocerebellar ataxia 2. Ann Neurol, 2004. 56(3): p. 444-7. [CrossRef]

- Rub, U., et al., Spinocerebellar ataxias types 2 and 3: degeneration of the pre-cerebellar nuclei isolates the three phylogenetically defined regions of the cerebellum. J Neural Transm (Vienna), 2005. 112(11): p. 1523-45. [CrossRef]

- Gierga, K., et al., Involvement of the cranial nerves and their nuclei in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2). Acta Neuropathol, 2005. 109(6): p. 617-31. [CrossRef]

- Ralser, M., et al., Ataxin-2 and huntingtin interact with endophilin-A complexes to function in plastin-associated pathways. Hum Mol Genet, 2005. 14(19): p. 2893-909. [CrossRef]

- Tuin, I., et al., Stages of sleep pathology in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2). Neurology, 2006. 67(11): p. 1966-72. [CrossRef]

- Lastres-Becker, I., et al., Insulin receptor and lipid metabolism pathology in ataxin-2 knock-out mice. Hum Mol Genet, 2008. 17(10): p. 1465-81. [CrossRef]

- Lastres-Becker, I., U. Rub, and G. Auburger, Spinocerebellar ataxia 2 (SCA2). Cerebellum, 2008. 7(2): p. 115-24.

- Nonis, D., et al., Ataxin-2 associates with the endocytosis complex and affects EGF receptor trafficking. Cell Signal, 2008. 20(10): p. 1725-39. [CrossRef]

- Rub, U., et al., Thalamic involvement in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) and a spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) patient, and its clinical relevance. Brain, 2003. 126(Pt 10): p. 2257-72. [CrossRef]

- van de Loo, S., et al., Ataxin-2 associates with rough endoplasmic reticulum. Exp Neurol, 2009. 215(1): p. 110-8.

- Almaguer-Mederos, L.E., et al., Estimation of the age at onset in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 Cuban patients by survival analysis. Clin Genet, 2010. 78(2): p. 169-74. [CrossRef]

- Auburger, G.W., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Handb Clin Neurol, 2012. 103: p. 423-36.

- Rub, U., et al., Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Prog Neurobiol, 2013. 104: p. 38-66. [CrossRef]

- Schols, L., et al., No parkinsonism in SCA2 and SCA3 despite severe neurodegeneration of the dopaminergic substantia nigra. Brain, 2015. 138(Pt 11): p. 3316-26. [CrossRef]

- Meierhofer, D., et al., Ataxin-2 (Atxn2)-Knock-Out Mice Show Branched Chain Amino Acids and Fatty Acids Pathway Alterations. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2016. 15(5): p. 1728-39. [CrossRef]

- Halbach, M.V., et al., Atxn2 Knockout and CAG42-Knock-in Cerebellum Shows Similarly Dysregulated Expression in Calcium Homeostasis Pathway. Cerebellum, 2017. 16(1): p. 68-81. [CrossRef]

- Lastres-Becker, I., et al., Mammalian ataxin-2 modulates translation control at the pre-initiation complex via PI3K/mTOR and is induced by starvation. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016. 1862(9): p. 1558-69. [CrossRef]

- Seidel, K., et al., On the distribution of intranuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates in the brainstem of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 and 3. Brain Pathol, 2017. 27(3): p. 345-355. [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.E., et al., Generation of an Atxn2-CAG100 knock-in mouse reveals N-acetylaspartate production deficit due to early Nat8l dysregulation. Neurobiol Dis, 2019. 132: p. 104559. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., et al., Ataxin2 functions via CrebA to mediate Huntingtin toxicity in circadian clock neurons. PLoS Genet, 2019. 15(10): p. e1008356. [CrossRef]

- Elden, A.C., et al., Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature, 2010. 466(7310): p. 1069-75. [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.A., et al., Therapeutic reduction of ataxin-2 extends lifespan and reduces pathology in TDP-43 mice. Nature, 2017. 544(7650): p. 367-371. [CrossRef]

- Gispert, S., et al., The modulation of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis risk by ataxin-2 intermediate polyglutamine expansions is a specific effect. Neurobiol Dis, 2012. 45(1): p. 356-61. [CrossRef]

- Lahut, S., et al., ATXN2 and its neighbouring gene SH2B3 are associated with increased ALS risk in the Turkish population. PLoS One, 2012. 7(8): p. e42956. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T., et al., Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions in European ALS patients. Hum Mol Genet, 2011. 20(9): p. 1697-700. [CrossRef]

- Ralser, M., et al., An integrative approach to gain insights into the cellular function of human ataxin-2. J Mol Biol, 2005. 346(1): p. 203-14. [CrossRef]

- Nonhoff, U., et al., Ataxin-2 interacts with the DEAD/H-box RNA helicase DDX6 and interferes with P-bodies and stress granules. Mol Biol Cell, 2007. 18(4): p. 1385-96. [CrossRef]

- Damrath, E., et al., ATXN2-CAG42 sequesters PABPC1 into insolubility and induces FBXW8 in cerebellum of old ataxic knock-in mice. PLoS Genet, 2012. 8(8): p. e1002920. [CrossRef]

- Kaehler, C., et al., Ataxin-2-like is a regulator of stress granules and processing bodies. PLoS One, 2012. 7(11): p. e50134. [CrossRef]

- Yokoshi, M., et al., Direct binding of Ataxin-2 to distinct elements in 3' UTRs promotes mRNA stability and protein expression. Mol Cell, 2014. 55(2): p. 186-98. [CrossRef]

- Fittschen, M., et al., Genetic ablation of ataxin-2 increases several global translation factors in their transcript abundance but decreases translation rate. Neurogenetics, 2015. 16(3): p. 181-92. [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, H., et al., Direct evidence that Ataxin-2 is a translational activator mediating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. J Biol Chem, 2020. 295(47): p. 15810-15825. [CrossRef]

- Canet-Pons, J., et al., Atxn2-CAG100-KnockIn mouse spinal cord shows progressive TDP43 pathology associated with cholesterol biosynthesis suppression. Neurobiol Dis, 2021. 152: p. 105289. [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S., et al., Poly(A)-binding protein is an ataxin-2 chaperone that regulates biomolecular condensates. Mol Cell, 2023. 83(12): p. 2020-2034 e6. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y., et al., Circadian clocks are modulated by compartmentalized oscillating translation. Cell, 2023. 186(15): p. 3245-3260 e23. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y., et al., PolyQ-expanded ataxin-2 aggregation impairs cellular processing-body homeostasis via sequestering the RNA helicase DDX6. J Biol Chem, 2024. 300(7): p. 107413. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., The LSmAD Domain of Ataxin-2 Modulates the Structure and RNA Binding of Its Preceding LSm Domain. Cells, 2025. 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Drost, J., et al., Ataxin-2 modulates the levels of Grb2 and SRC but not ras signaling. J Mol Neurosci, 2013. 51(1): p. 68-81. [CrossRef]

- Meunier, C., et al., Cloning and characterization of a family of proteins associated with Mpl. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(11): p. 9139-47. [CrossRef]

- Coller, J. and R. Parker, General translational repression by activators of mRNA decapping. Cell, 2005. 122(6): p. 875-86. [CrossRef]

- Lobel, J.H. and J.D. Gross, Pdc2/Pat1 increases the range of decay factors and RNA bound by the Lsm1-7 complex. RNA, 2020. 26(10): p. 1380-1388. [CrossRef]

- Hurst, Z., et al., A distinct P-body-like granule is induced in response to the disruption of microtubule integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 2022. 222(1). [CrossRef]

- Vijjamarri, A.K., et al., mRNA decapping activators Pat1 and Dhh1 regulate transcript abundance and translation to tune cellular responses to nutrient availability. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(17): p. 9314-9336. [CrossRef]

- Bahassou-Benamri, R., et al., Subcellular localization and interaction network of the mRNA decay activator Pat1 upon UV stress. Yeast, 2013. 30(9): p. 353-63. [CrossRef]

- Vindry, C., et al., Dual RNA Processing Roles of Pat1b via Cytoplasmic Lsm1-7 and Nuclear Lsm2-8 Complexes. Cell Rep, 2017. 20(5): p. 1187-1200.

- Vindry, C., D. Weil, and N. Standart, Pat1 RNA-binding proteins: Multitasking shuttling proteins. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA, 2019. 10(6): p. e1557. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.J., et al., The conserved P body component HPat/Pat1 negatively regulates synaptic terminal growth at the larval Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Cell Sci, 2012. 125(Pt 24): p. 6105-16. [CrossRef]

- Kaehler, C., et al., PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation controls ATXN2L localization. Exp Cell Res, 2015. 334(1): p. 114-25. [CrossRef]

- Key, J., et al., ATXN2L primarily interacts with NUFIP2, the absence of ATXN2L results in NUFIP2 depletion, and the ATXN2-polyQ expansion triggers NUFIP2 accumulation. Neurobiol Dis, 2025. 209: p. 106903. [CrossRef]

- Key, J., et al., Mid-Gestation lethality of Atxn2l-Ablated Mice. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(14). [CrossRef]

- Truett, G.E., et al., Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT). Biotechniques, 2000. 29(1): p. 52, 54. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J., et al., Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods, 2012. 9(7): p. 676-82. [CrossRef]

- Martens, L., et al., PRIDE: the proteomics identifications database. Proteomics, 2005. 5(13): p. 3537-45.

- Szklarczyk, D., et al., The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(D1): p. D638-D646. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., Beyond regulation of pol III: Role of MAF1 in growth, metabolism, aging and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2018. 1861(4): p. 338-343. [CrossRef]

- Schlaitz, A.L., et al., REEP3/4 ensure endoplasmic reticulum clearance from metaphase chromatin and proper nuclear envelope architecture. Dev Cell, 2013. 26(3): p. 315-23. [CrossRef]

- Burke, B., PREEParing for mitosis. Dev Cell, 2013. 26(3): p. 221-2. [CrossRef]

- Urlaub, H., et al., Sm protein-Sm site RNA interactions within the inner ring of the spliceosomal snRNP core structure. EMBO J, 2001. 20(1-2): p. 187-96. [CrossRef]

- Decker, C.J. and R. Parker, P-bodies and stress granules: possible roles in the control of translation and mRNA degradation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2012. 4(9): p. a012286. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S. and A.P. McMahon, Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol, 2002. 244(2): p. 305-18. [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, D., et al., Spontaneous ectopic recombination in cell-type-specific Cre mice removes loxP-flanked marker cassettes in vivo. Genesis, 2004. 38(4): p. 159-65.

- Chakravarthy, S., et al., Cre-dependent expression of multiple transgenes in isolated neurons of the adult forebrain. PLoS One, 2008. 3(8): p. e3059. [CrossRef]

- Senserrich, J., et al., Analysis of Runx1 Using Induced Gene Ablation Reveals Its Essential Role in Pre-liver HSC Development and Limitations of an In Vivo Approach. Stem Cell Reports, 2018. 11(3): p. 784-794. [CrossRef]

- Crawley, J.N., Behavioral phenotyping strategies for mutant mice. Neuron, 2008. 57(6): p. 809-18. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.Y., et al., Neuronal Yin Yang1 in the prefrontal cortex regulates transcriptional and behavioral responses to chronic stress in mice. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 55. [CrossRef]

- Mastwal, S., et al., Adolescent neurostimulation of dopamine circuit reverses genetic deficits in frontal cortex function. Elife, 2023. 12.

- Bish, R., et al., Comprehensive Protein Interactome Analysis of a Key RNA Helicase: Detection of Novel Stress Granule Proteins. Biomolecules, 2015. 5(3): p. 1441-66. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., et al., FMRP Control of Ribosome Translocation Promotes Chromatin Modifications and Alternative Splicing of Neuronal Genes Linked to Autism. Cell Rep, 2020. 30(13): p. 4459-4472 e6. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.L., et al., TDP-43 loss and ALS-risk SNPs drive mis-splicing and depletion of UNC13A. Nature, 2022. 603(7899): p. 131-137. [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.I., et al., Cooperative nuclear action of RNA-binding proteins PSF and G3BP2 to sustain neuronal cell viability is decreased in aging and dementia. Aging Cell, 2024. 23(12): p. e14316. [CrossRef]

- Goebbels, S., et al., Genetic targeting of principal neurons in neocortex and hippocampus of NEX-Cre mice. Genesis, 2006. 44(12): p. 611-21. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., et al., 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res, 2017. 27(5): p. 606-625. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol, 2019. 21(8): p. 978-990. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N., C. McMahon, and G. Blobel, Primary structure of a human arginine-rich nuclear protein that colocalizes with spliceosome components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1991. 88(18): p. 8189-93. [CrossRef]

- Twyffels, L., C. Gueydan, and V. Kruys, Shuttling SR proteins: more than splicing factors. FEBS J, 2011. 278(18): p. 3246-55. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J. and J.Y. Wu, Functional properties of p54, a novel SR protein active in constitutive and alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol, 1996. 16(10): p. 5400-8. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.F., A. Kramer, and S.M. Berget, A role for SRp54 during intron bridging of small introns with pyrimidine tracts upstream of the branch point. Mol Cell Biol, 1998. 18(9): p. 5425-34. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, N.H. and J.Y. Roignant, Anything but Ordinary - Emerging Splicing Mechanisms in Eukaryotic Gene Regulation. Trends Genet, 2021. 37(4): p. 355-372. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).