1. Introduction

Most scientific endeavours are accomplished by human beings in conscious mental states. These conscious states constitute the subjective experience of the self. Many of these states seem to connect an external entity, the world, with the self, the inner subject who observes the world. One of the central pillars of Western natural philosophy since ancient Greece was precisely to assume the existence of such external world independent of the observer (Schrödinger, 1954). In this way, a third-person objective point of view was adopted in the classical study of nature. And basically, until the development of quantum mechanics this state of affairs was the mainstream in natural sciences.

On the other hand, the study of mind was practically restricted to philosophy from Descartes and his dualistic description of the mind-body problem in the seventeenth century to the introduction of quantum mechanics at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, consciousness entered physics as a possible necessary central piece in the resolution of the measurement problem within several interpretations of quantum mechanics (e.g., Copenhagen interpretation (Faye, 2019; Plotnitsky, 2012), Wigner interpretation (Wigner, 1961) …). In the end, all the information about the outside world reaches the brain of a human being mediated by the senses of their body and therefore the properties of that external world can only be indirectly deduced through these data (see von Helmholtz (1903) and chapter 6 of von Neumann’s book (1955) devoted to quantum measurement theory). Therefore, at a certain level of reduction in the description of this process, it would be reasonable to expect the necessity of studying the properties of consciousness in order to reliably extract the characteristics of the outside world from the representation generated in the mind. A schematic overview of some of the main philosophical descriptions of the problem of consciousness is briefly outlined in

Section 2.

In this paper, a physical model for consciousness is devised in the framework of an approach to study the foundations of quantum mechanics (Baladrón, 2010, 2014, 2017; Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2023) in which it is assumed that matter possesses the capacity of processing information. In this approach, a fundamental particle is characterized at time t by its position and mass in physical space, and it is supplemented with an information space in which a classical Turing machine (Barker-Plummer, 2012) (basically, a mathematical model of a classical digital computer) and a randomizer (a random number generator) are stored. In physical space, particles follow continuous trajectories and interact by exchanging carriers of momentum, energy and information, satisfying the principle of conservation of momentum and energy. The information conveyed by the carriers impinging on a particle is transferred to its information space and, in turn, after a run of the program, the output determines the momentum and energy of the carrier to be emitted by the particle in physical space.

One of the messages of our work is that information space should be treated on the equal grounds with the physical space. The flows of information are not less real than the flows of matter and fields.

A strong assumption has been made in this approach disregarding in a first-order approximation the contribution of gravitation to the evolution of the structure and interaction mechanisms of the fundamental particles from the Big Bang. As abovementioned, it has been assumed that momentum and energy are conserved in physical space. On the contrary, information is not conserved in the union of all the information spaces associated by definition with the fundamental particles. Specifically, inconsequential information for the dynamics of a particle will be deleted on the information space of the particle, introducing irreversibility in the model and constituting a central element for the characterization of consciousness in this approach, as it will be discussed throughout the article.

Every particle in this approach is governed by a program, a classical algorithm that encodes the quantum mechanical formalism, and an anticipation module that predicts the configuration of the surrounding systems at time

. In this way, as will be analysed in the

Appendix, a fundamental particle would behave quantum mechanically in real time. Given that every particle follows a continuous trajectory, the quantum dynamics resembles a generalized Bohmian mechanics, in particular, the measurement problem is solved in a similar way to Bohmian mechanics (Goldstein, 2021; Hoffman and Vona, 2014).

This information-theoretic model of fundamental particles has been applied in previous articles (Baladrón, 2010, 2014, 2017; Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2023) to study the relationships between classicality and quantumness and, in particular, to analyse a possible scenario in which quantum behaviour would emerge as a consequence of Darwinian evolution under natural selection acting on populations of these information-theoretic particles.

In the present article, a second way of interaction between the physical and the information space of a particle is postulated in the framework of this Darwinian approach to quantum mechanics (DAQM). When an apparatus measures the property of a particle, at the end of the process, only a branch of the wave function of the particle effectively keeps playing a role in its dynamics. The superfluous branches are then erased on the information space of the particle and it is hypothesized that this erasure of information on the information space induces an elementary event of phenomenological consciousness (or proto-consciousness) on the particle. This event of elementary proto-consciousness consists in the experience of the spatial locations of the surrounding particles as calculated by the program of the particle. Notice that our basic postulate characterizes elementary phenomenological consciousness as the result of the effective collapse of the wave function, just the other way around with respect to the usual assumption in quantum mechanical Wigner-like interpretations, but the same causal-effect order as in the Penrose-Hameroff theory of consciousness (Hameroff and Penrose, 1996), in which the objective collapse of the wave function is induced by a gravitational process (Diósi-Penrose scheme for the objective reduction of the quantum state (Diósi, 1989; Penrose,1996)).

In our model, proto-consciousness, by definition, is a property of matter associated to the erasure of superfluous information for the dynamics of the particle on its information space. This is the core of this model of consciousness that is developed in

Section 3.

In

Section 4, the characterization of measurement and observation in our model for a fundamental particle is formalized, and the implications for the quantum mechanical description of the world are further analysed, in particular, discussing how the model describes elementary Wigner’s friend (Wigner, 1961) scenarios in which the predictions of this model could be compared with possible future experiments.

The assumption of proto-consciousness in fundamental particles leads to the so-called combination problem, i.e., determining the way in which higher-level consciousness appears in a system composed of conscious subsystems, and the extent in which the lower-level consciousness in the constituents is affected by the emergence of consciousness in the composite system. The combination problem and an outline of its natural possible solution in this model by means of the concept of entanglement is addressed in

Section 5. Information-theoretic Darwinian evolution makes room for a possible mechanism through which consciousness might play an active role in the physical space without altering the observed status quo of physics. This mechanism is preliminarily described in

Section 6. The fundamental role that proto-consciousness, as a hypothetical intrinsic property of matter, might play in Darwinian evolution and the manner in which high-level consciousness might be generated through evolution in complex biological systems is schematically discussed in

Section 7. The implications of the model for the possible development of high-level consciousness in a future artificial general intelligence (AGI) are briefly considered. To end

Section 7, the natural implementation of a mechanism bringing about genuine, compatibilist free will for complex biological systems in this DAQM model for consciousness is succinctly described. Some conclusions of the article are drawn in

Section 8. Finally, the Darwinian approach to quantum mechanics (DAQM), the physical framework in which the model of consciousness has been developed, is briefly summarized in the

Appendix.

2. Overview of Some Philosophical Approaches to the Mind-Body Problem

The majority of scientists explicitly or implicitly adopt a materialist perspective as fundamental ontology of the world. Materialism (Stoljar, 2023) (or physicalism in more modern and precise language) assumes that matter is the fundamental stuff from which anything that exists in the world is made. In particular, consciousness also ought to be exclusively describable in terms of matter. Physicalism is a monistic philosophical doctrine, the simplest way of describing the world. However, physicalism is confronted with the so-called “hard problem of consciousness”, as named by Chalmers (1995), that is, the unsurmountable difficulty, in appearance, of describing consciousness, subjective experience, in terms of space, time, mass, charge, spin…the fundamental properties characterizing the physical world. This explanatory gap seems to defeat physicalism and its endeavour of reducing the qualities of the subjective sensations of a conscious system to the structure and function of physical entities. Several philosophical arguments (e.g., the philosophical zombie (Chalmers, 1996; Kirk, 2009), Mary’s room (Jackson, 1982)) have been developed to illustrate and highlight the unparalleled nature of this problem. The “hard problem of consciousness” has fuelled the search for other philosophical frameworks being able to give a satisfactory scientific account of subjective experience.

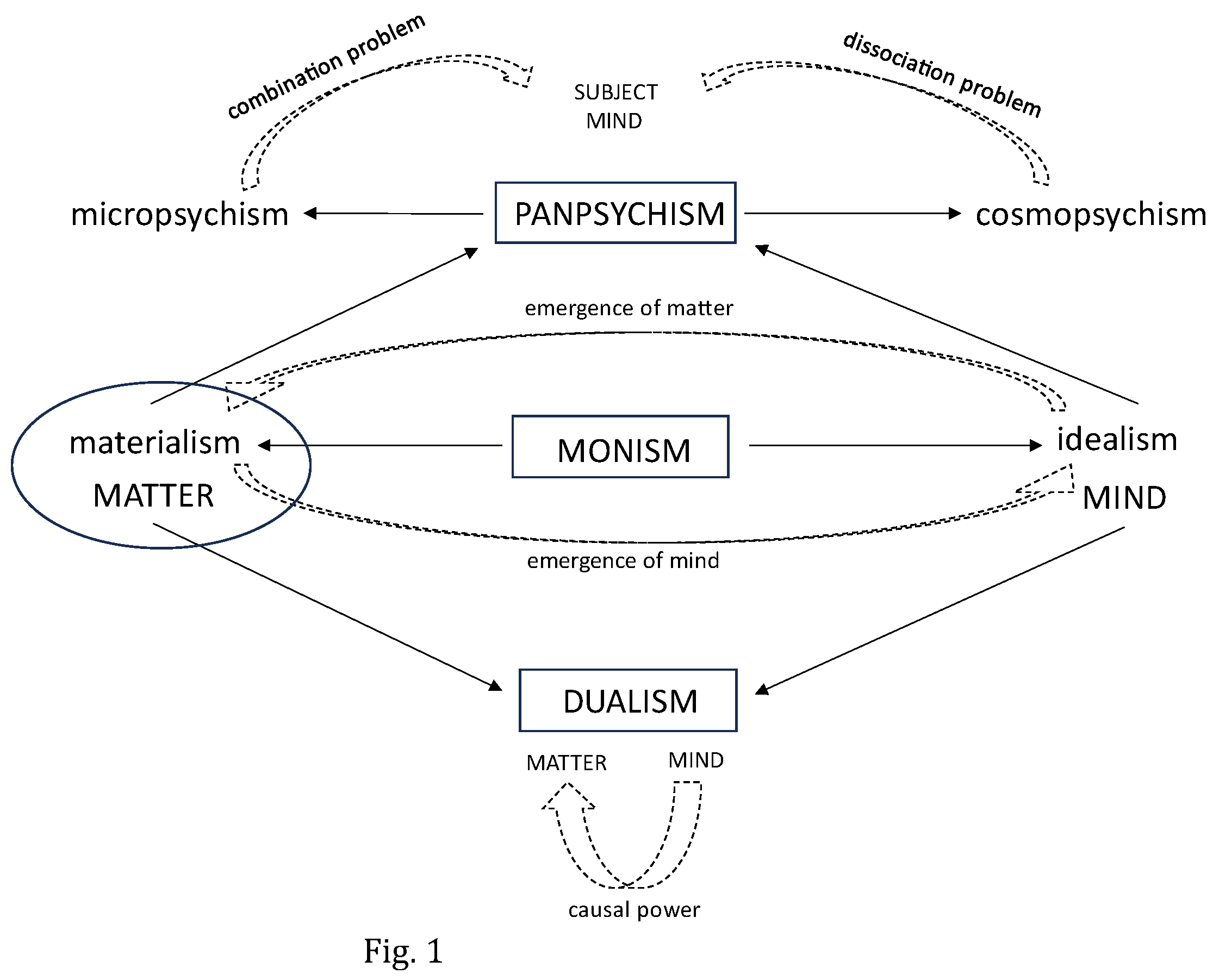

There is another monistic perspective for contemplating the world (see

Figure 1 for an interconnected summary of some of the most relevant philosophical theories facing up to the mind-body problem). This is idealism (Guyer and Horstmann, 2023), namely, the philosophical school in which the foundation of all reality is considered to be something mental (mind, thought, consciousness). Matter would be a derivative entity produced by consciousness. One of the main problems of idealism in its classical formulation is the risk of solipsism, namely, that the only sure thing to exist is the mind of the own thinking subject. Idealism could seem, at first sight, an old-fashioned philosophical scheme from the perspective of the down-to-earth scientist, however, there are some modern and invigorating descriptions of the world (Chalmers, 2022) that can be framed in this school and some of them could connect with certain anti-realist interpretations of quantum mechanics (Chalmers, 2022).

A natural way of avoiding the problems of monistic doctrines is dualism. This philosophical view assumes that the world is constituted by two fundamental elements: matter and mind. The central difficulty of dualism is the seemingly well-established causal closure of matter. The fact that every event in the physical world seems to have a material cause, what would leave no room for the interaction between matter and mind, therefore apparently making superfluous and irrelevant the existence of mind for the physical world.

In Eastern and Western philosophy, panpsychism (Goff, Seager, and Allen-Hermanson, 2022) was another salient option to solve the mind-body problem until the beginning of the twentieth century (Goff, Seager, and Allen-Hermanson, 2022). However, it has attracted a renewed interest as a promising solution in these last decades. In simple terms, panpsychism considers that mind or consciousness (perhaps in an elementary manner that could be named proto-consciousness) is essential and ubiquitous in the physical world. Among the many variants of this philosophy (see Goff, Seager, and Allen-Hermanson (2022) for an extensive discussion), two of them particularly representative are micropsychism, in which fundamental particles would have some kind of elementary subjective experience (i.e., microphysical systems would have mental states (Chalmers, 2021a)) and cosmopsychism, in which the universe as a whole would be a conscious entity (i.e., the universe would have mental states (Chalmers, 2021a)). Panpsychism in its different versions can soften the difficulties of the other philosophical views, but it comes with its own lot of problems: the so-called combination problem (Chalmers, 2021a; Goff, Seager, and Allen-Hermanson, 2022) for micro-panpsychism, namely, how to describe the generation of consciousness for a composite system in terms of the consciousness of the component subsystems, and the dissociation problem (Chalmers, 2021a; Kastrup, 2017) for cosmo-panpsychism, i.e., how and why the consciousness of a system is dissociated from the consciousness of the universe as a whole (Goff, Seager, and Allen-Hermanson, 2022).

A fundamental work of modern philosophy that can be considered as a contribution to panpsychism is Whitehead’s “Process and Reality” (Whitehead, 1929). The concept of proto-mental elements of reality introduced by Whitehead can serve as a base for a quantum-like treatment of panpsychism (see Khrennikov (2003) for a deeper discussion).

The philosophical system developed by Whitehead with its central concept of process as the cornerstone of its structure was mainly thought to answer the crucial questions that the new physics was posing to philosophers and scientists at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, this initial physical perspective would inevitably drive to the mind-body problem revealing a natural panpsychist component in the nucleus of Whitehead’s philosophical endeavour. In spite of the opinion shared by several scholars (McHenry, 1995; Seager, 2004) on the plausible panpsychist adscription of Whitehead’s philosophy, this view is the subject of some controversy. Whitehead himself was reluctant to admit the panpsychist imprint in his philosophy when overtly confronted with the question (McHenry, 1995). His reply to Victor Lowe was an elusive “Yes, and No” (McHenry, 1995).

Although physicalism in principle seems unable of solving satisfactorily the hard problem of consciousness, however, its paramount success in describing the observed universe largely justifies the sustained engagement entertained in modern science in order to find out a scheme that reduces consciousness to sheer material elements. A reflection of this engagement is the ample gallery of proposals ranging from the pure denial of the existence of consciousness, the assertion that consciousness is just an illusion (Frankish, 2016), going through the identity theory (Smart, 2022) that equates mental states to brain states, continuing with theories, like computational functionalism (Smart, 2022), that characterizes consciousness as a complex enough computational process that is independent of the nature of the material support, until reaching the most radical proposals contending that new physics is required for reducing consciousness to the function and structure of physical systems.

The boundary between philosophical views is somehow fuzzy, e.g., Tegmark’s physicalist theory holds that the ontology of the physical world is its mathematical structure (Tegmark, 2008), i. e., the equations describing the universal laws that govern the behaviour of matter. This perspective is not far from a platonist view. This fuzziness of frontiers can also be identified between panpsychism and dualism. The version of dualism named property dualism considers consciousness not as a substance, but as a non-physical property of matter what drastically reduces the differences with panpsychism.

The theoretical model that is going to be introduced in the next section can be classified, as will be discussed below, within the physicalist stream that incorporates new physics. Although, given its structure, some caveats may arise regarding its philosophical adscription, in the end it is claimed that this model can be catalogued as physicalist.

An extensive list of current theories for consciousness can be found in Chalmers (2023). A volume devoted to mathematical and empirical foundations of models of consciousness has been edited by Arsiwalla et al. (2023). Several approaches that propose quantum theory may contribute to understand consciousness have been surveyed by Atmanspacher (2024). Within the same domain, a set of articles studying the possible connections between consciousness and quantum mechanics have been edited by Gao (2022). An encyclopaedic effort for compiling a guide to explore the vast landscape of theories of consciousness has been accomplished by Kuhn (2024).

3. Model for Elementary Consciousness in a Fundamental Particle

A direct implication of quantum mechanics is that matter is more complex than envisaged in classical physics. The simple, classical characterization of the evolution of matter states, giving the temporal trajectory of a particle in its phase space is not adequate to describe the behaviour of matter at the microscopic level, mainly, whose greater complexity is already manifest in the required Hilbert space structure for the space of states of a system in quantum mechanics.

Perhaps the mind-body problem, as pointed out by Chomsky (2022), is not as much on the side of consciousness, as on the nature of matter that is not yet completely understood. The current situation for the problem of consciousness, as remarked by Chalmers (2021b), resembles the impasse at the end of the eighteenth century for describing electric phenomena in the conceptual framework of Newtonian mechanics. That deeply baffling state of affairs came to an end by incorporating a new intrinsic property, the electric charge, for characterizing matter.

Following these thought-provoking ideas, two main new elements are introduced in the model of consciousness that is going to be defined. First, it is assumed that matter has an intrinsic capacity of processing information what is captured in the information-theoretic characterization of a fundamental particle in DAQM (Baladrón, 2010, 2014, 2017; Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2023). Second, it is considered, as hypothesized by Chalmers (1995), that information might have two aspects: a physical facet and a phenomenal facet. The first aspect would coincide with its usual quantitative character, and the second one with a qualitative character of information that might constitute the basis for describing the emergence of experience from the physical (Chalmers, 1995).

The model is then developed elaborating these two basic assumptions. Accordingly, a fundamental particle

is characterized as a classical-like point mass with coordinates

in physical space, subject to the conservation of momentum and energy, and supplemented with an information space in which a classical Turing machine is included. In addition, a control program

, an anticipation module

, a randomizer

, and an information deleting subroutine

1 are stored on the information space of the particle. Now, if

, which is a classical algorithm, encoded the quantum mechanical formalism, then, as is discussed in the

Appendix2, the fundamental particle might behave as a quantum system in real time. In this way, the first requirement of the model, the fact that the particle has an intrinsic capacity of processing information, is fulfilled. The particle has been characterized as an agent whose behaviour is not determined by universal laws, beyond the conservation principles, but by the program that is stored on its information space. The possibility that a population of particles such as the characterized in this model might emerge under the action of Darwinian evolution from sheer classical-like particles supplemented with an information space and endowed with a classical Turing machine and just a randomizer

is analysed in the

Appendix.

The DAQM particles deeply resemble actual occasions --the elementary entities in Whitehead’s process philosophy (Whitehead, 1929)-- in its characterization as potentialities determined by past occasions. In DAQM, these past occasions would be programs and data stored in the information spaces of the particles, whose actualizations would result from the output generated by the control algorithm in response to the interaction with the environment or the measurement apparatus. The input or external data would condition the output, and therefore would dynamically determine the actual property of a particle, not as an intrinsic parameter of the particle, but as a magnitude that only takes a value when properly prompted by a specific environment or measurement apparatus. Thus, DAQM particles are not classical systems in the sense that they are not characterized by intrinsic properties (excluding the location of the particles) well defined at any moment in time, but, as actual occasions, are better characterized as processes, the combination of information and material processes, whose realization would be jointly determined by the inner state or past occasions and the input data or external state that characterizes the environment.

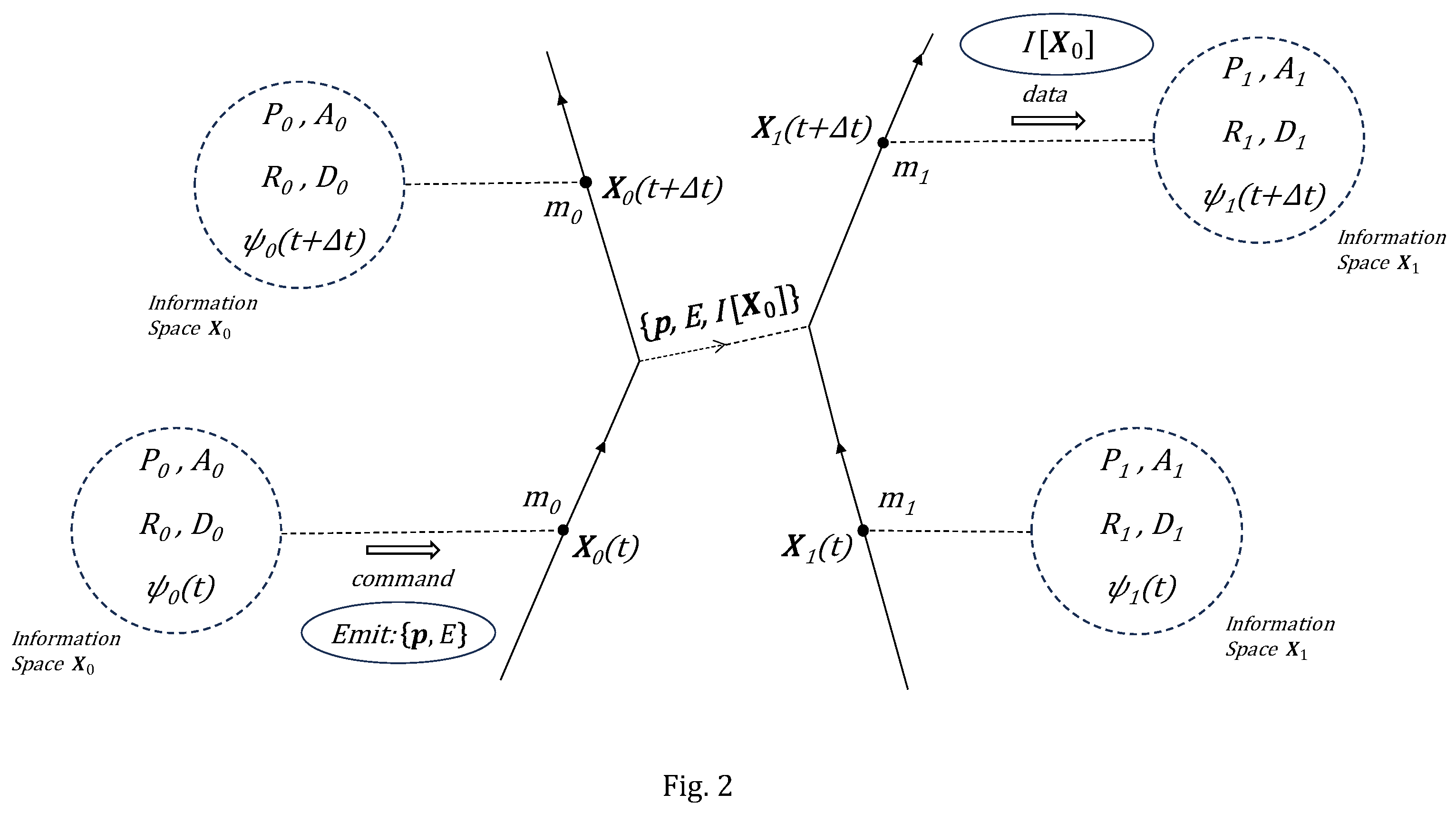

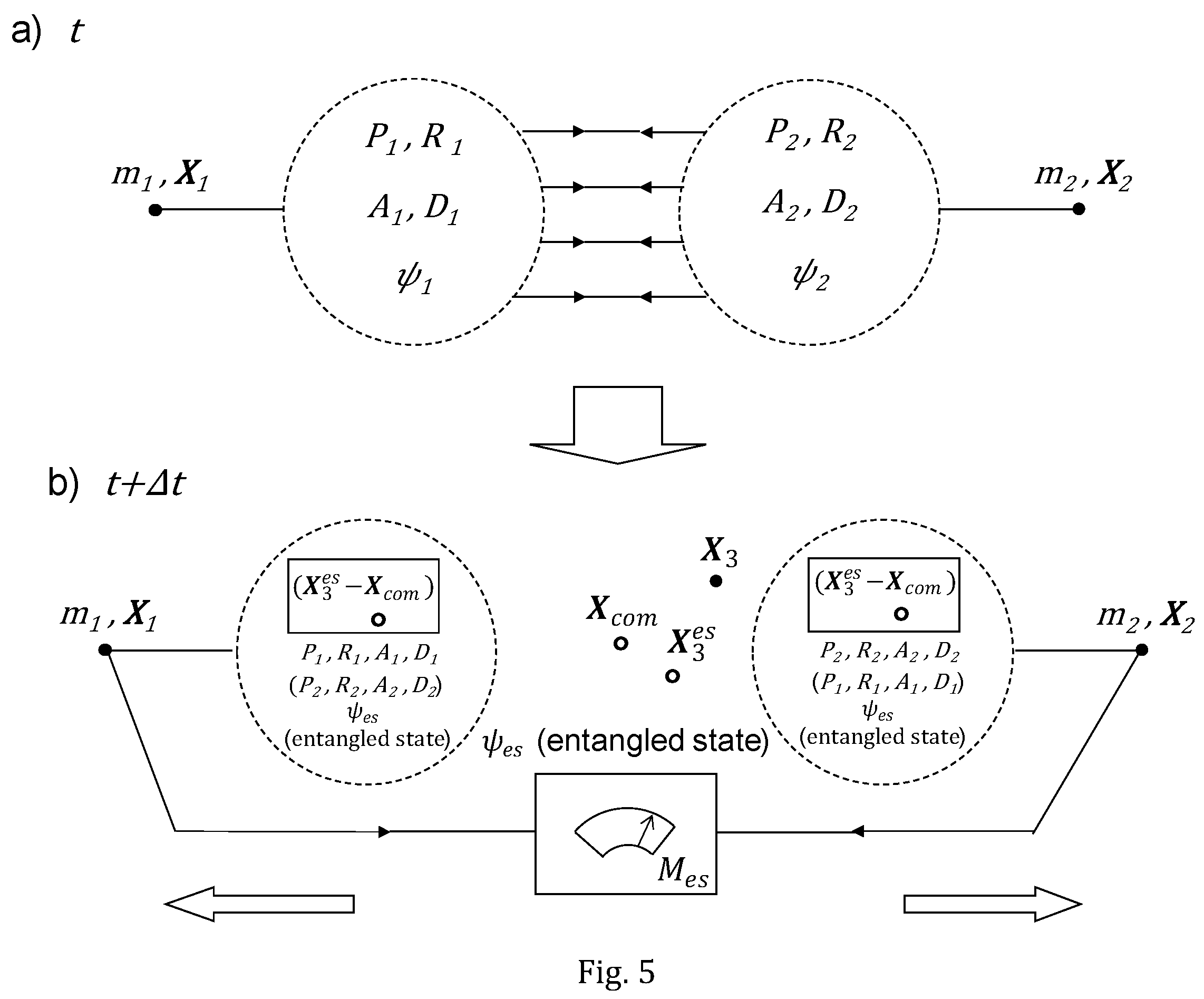

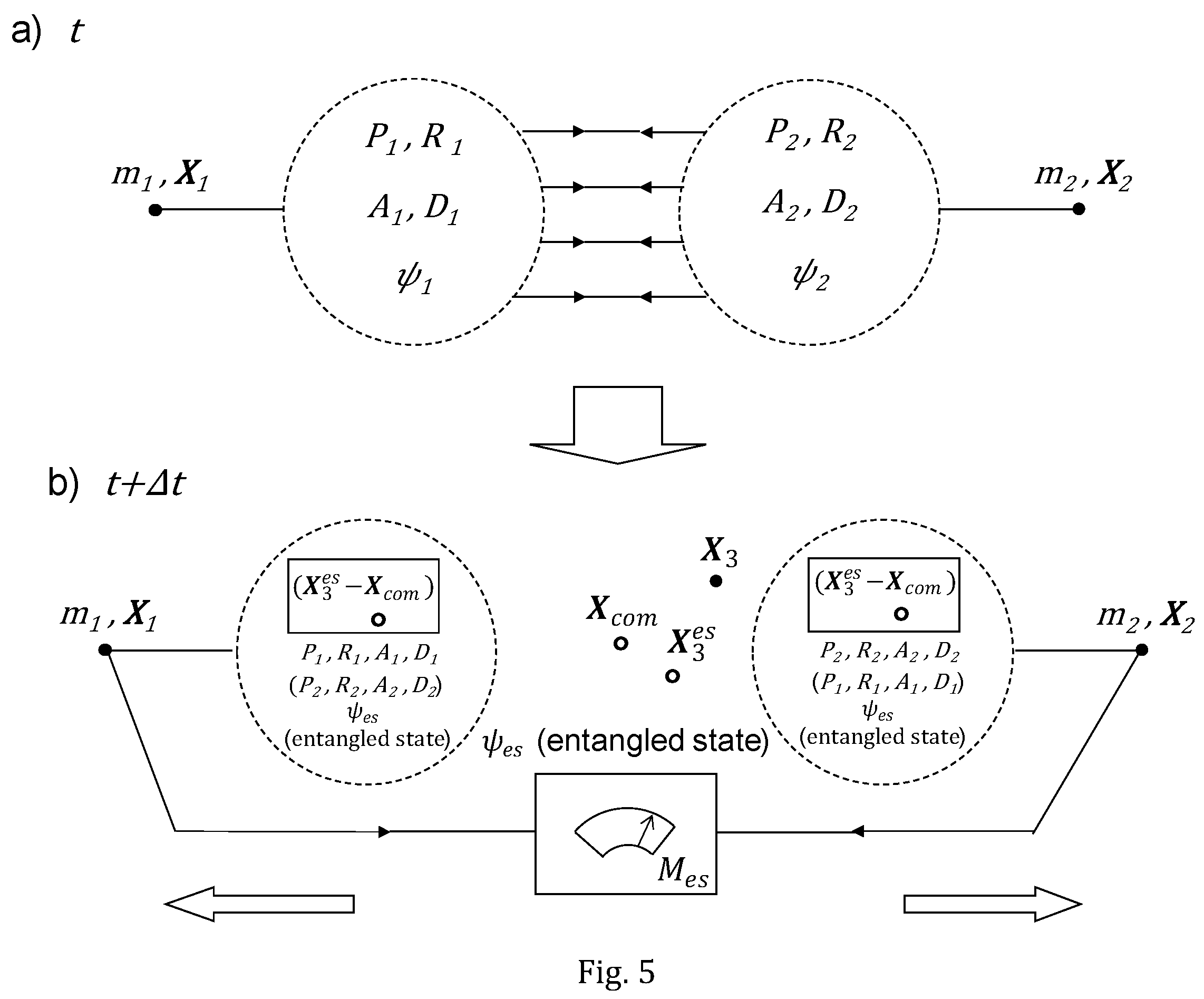

A generic interaction, in the framework of DAQM, between two particles with masses

and

, and space coordinates

and

is depicted in

Figure 2. Both particles are initially represented in physical space at time

. Their respective information spaces are drawn as dotted line circumferences encircling their respective control algorithms,

and

, anticipation modules,

and

, randomizers,

and

, information deleting subroutines,

and

, and wave functions,

and

, at time

t.

After a run of the control program

on the information space of the particle

, a command of emitting an information carrier of momentum

p and energy

E is sent to the particle

. As a consequence, the trajectory of the particle (straight solid line associated with the particle

in

Figure 2) changes according to the conservation of momentum and energy, and the wave function

ψ0(

t +Δ

t) at time

is computed.

When the emitted carrier impinges on the particle , the carrier is absorbed by the particle, the new trajectory of the particle is determined by the conservation of momentum and energy, and the information about the emitting particle that is transported by the carrier arrives at the information space of the particle . The wave function ψ1(t +Δt) at time t +Δt for the particle has been calculated by the algorithms on the information space of the particle .

The current carriers of momentum, energy and information in DAQM would be the field bosons in the Standard Model. In particular, considering for simplicity an ensemble of electrons, these carriers would be photons. Hypothetically, the fundamental particles of the Standard Model should have emerged as the fittest physical species in the Darwinian evolutionary complex dynamics in which quantum mechanical behaviour would encode the optimal strategy for the survival of the populations of information-theoretic fundamental particles. These particles would attain a dynamic stability characterized by an average mass and a set of classical algorithms in their information spaces that were able to emulate quantum behaviour in real time as a consequence of the initial conditions at the Big Bang and Darwinian evolution under natural selection acting on these information-theoretic classical-like particles that at time

were exclusively controlled by the individual randomizers stored on the information spaces of every particle. As mentioned, the feasibility of this scenario is discussed in the

Appendix.

In this DAQM model, like in Bohmian mechanics (Goldstein, 2021; Hoffman and Vona, 2014) and in de Broglie’s theory of the double solution (de Broglie, 1963), position is the realist physical parameter that characterizes the particle at any time. The trajectory of the particle in physical space is a continuous function (straight solid lines in

Figure 2). In this sense, the measurement problem is solved like in Bohmian mechanics. At any time, the positions of all the systems involved in the process are well defined.

The DAQM model might be considered a sort of generalized Bohmian mechanics, but in which nonlocality has been removed thanks to the supplementary information spaces ascribed to every particle and the development of anticipation modules on them. In this Bohmian picture of the DAQM model, the prescribed trajectory of a particle given by the guiding equation would coincide with the trajectory generated by the emission of the photons sequence as computed by the control program on the information space of the particle. In particular, the model considered in this article should be compared with the variant of Bohmian mechanics that defines the wave function as a purely epistemological object, and even in more precise terms, the Bohm-Vigier stochastic version (Bohm and Vigier, 1954) including a random term in the guiding equation would properly match the action of the randomizer on the dynamics of the particle.

The second main element of the model is the central hypothesis characterizing consciousness. It is assumed that the qualitative, phenomenal aspect of information is an intrinsic property of matter that generates an elementary conscious event in any fundamental particle when the branches of the wave function that become, for all practical purposes, irrelevant for the dynamics of the particle are erased on its information space. In other words, this elementary conscious event occurs when the wave function

of the particle effectively collapses. The core of the model is then the assumption that when the superfluous information for the dynamics of the particle is erased on the information space, i.e., when the collapse of the wave function irreversibly

3 happens, then a subjective experience is induced on the particle

corresponding to a representation of the estimated sharp locations {

} of the surrounding systems,

, (that are not necessarily the actual positions {

} of such surrounding systems,

) as calculated by the program stowed on the information space of the particle

.

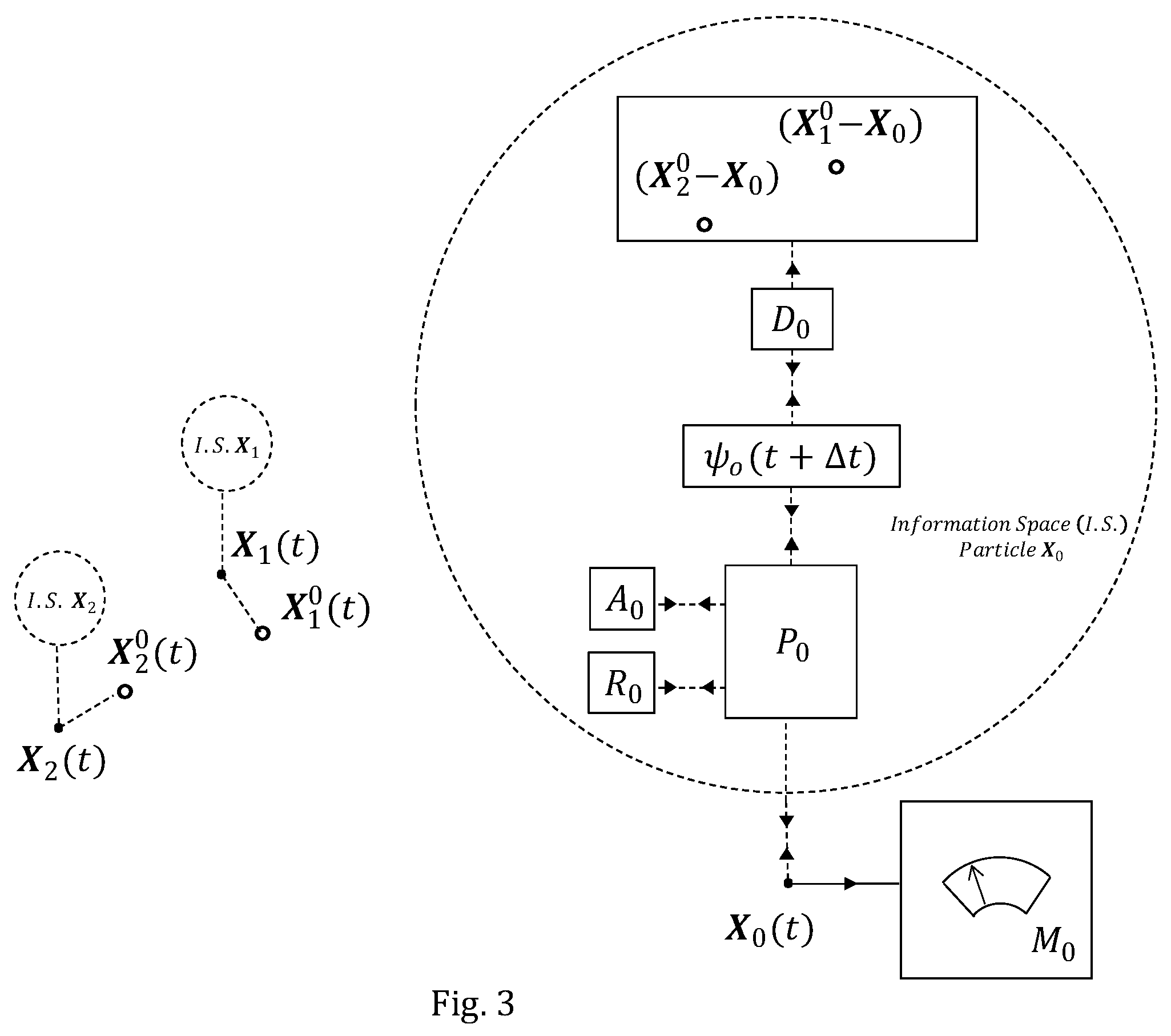

An example of the generation of an elementary conscious event for the particle

surrounded by two particles (

is represented in

Figure 3. The particle

at time

t is surrounded by two other particles located (black dots) at

and

. The information spaces of the particles are represented by dashed line circumferences. At time

t, the particle

is measured by the device

. This implies that only the branch of the wave function

whose support contains the actual location of the particle is meaningful for the dynamics of such particle

. Therefore, the empty branches of the wave function

computed by the control algorithm

are deleted by the subroutine

, and according to the model an elementary conscious event is generated on the particle

, corresponding to the spatial representation of the calculated positions on the information space of particle

of the surrounding systems (

and

). These calculated positions are drawn in

Figure 3 as empty dots, and, in general, they do not coincide with the actual locations (

and

) of the particles. The perspective of the representation (the subjective experience) corresponds with the position occupied by the particle

.

Consciousness, in this model, is considered as part of a process, much in the like of Whitehead’s philosophy of organism (Sulis, 2025; Whitehead, 1929, 1933). A connection can also be established with the concept of mediation, in the sense discussed by Taguchi (2022), considering consciousness, in the present microscopic model, as a kind of mediation between the world and the particle, between the objective property of the world, systems’ locations, and its subjective representation on the information space of the particle.

4. Measurement, Observation, and Wigner’s Friend-like Scenarios

The measurement problem in this model is solved as in the de Broglie-Bohm theory (de Broglie, 1963; Goldstein, 2021; Hoffman and Vona, 2014), given that particles have well-defined positions at any time

4, and that all systems, even macroscopic systems and measuring apparatuses, can be characterized as constituted by quantum particles. Therefore, in this model as in the de Broglie-Bohm theory, a measurement is just a particular kind of interaction that results in the effective collapse of the wave function of a system when interacting with a measurement device, that is defined as a system whose possible configurations after an interaction are macroscopically distinguishable, like different directions for a pointer (Hoffman and Vona, 2014). The interaction between the system and the measurement apparatus reduces, for all practical purposes, the overlap of the different terms of the system’s wave function to negligible values, what implies that only the branch of the wave function whose support in the configuration space contains the actual location of the system retains its dynamical relevance.

When the effective collapse is induced, according to the introduced model, the dynamically superfluous branches of the wave function are deleted on the information space of the system, triggering the computation by the control program of the estimated positions of the surrounding systems, and generating an elementary conscious event that constitutes an elementary observation of its surrounding world by the system. Therefore, if a system is measured at time , this system is an observer at time .

If the observer system is a fundamental particle, then the information that is contained in the observation is stored on the information space of the particle, but this information cannot be shared with or communicated to other systems, unless the particle and such systems become entangled.

Note that in this model measurement and observation are two different processes. A measurement is a specific, well-defined kind of interaction that drives a system to the effective collapse of its wave function, and an elementary observation is a register of estimated information about the locations of the surrounding systems of the observer that is stored on its information space and associated with an elementary subjective experience of the observer caused by the erasure of the dynamically superfluous branches of its wave function that irreversibly completes its effective collapse.

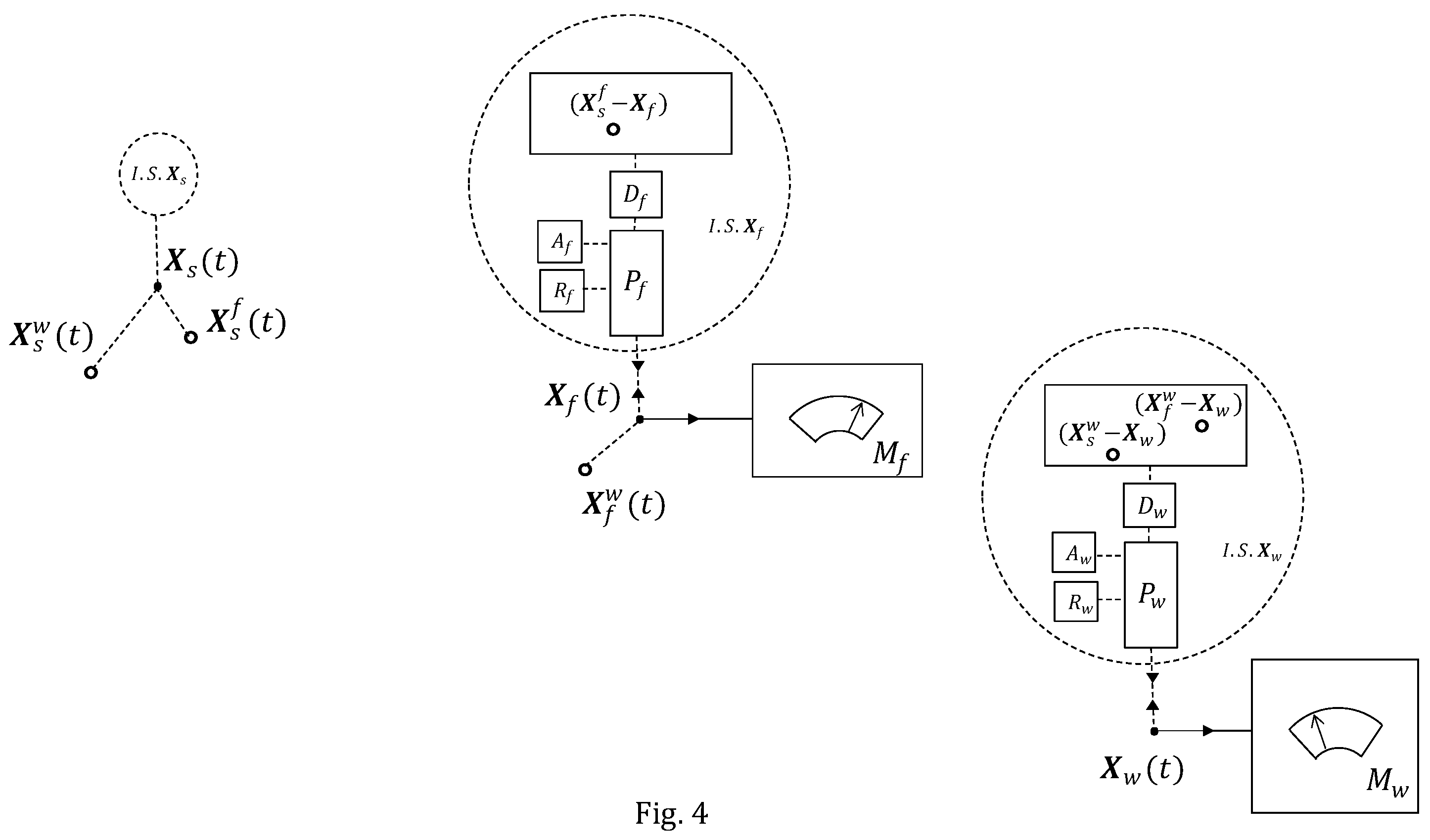

In this model, fundamental particles are qualified as elementary Wigner’s friends (Wigner, 1961) since fundamental particles are characterized as elementary conscious observers. Therefore, an elementary Wigner’s friend-like scenario (see

Figure 4) may be constituted by three particles, the test particle

whose position is going to be observed by the second particle

, the Wigner’s friend, and finally a third particle

that plays the role of Wigner as a system that observes the composite system

5 formed by particle

and particle

. Every fundamental particle in DAQM is supplemented by its information space (dashed-line circles in

Figure 4). In order to be observers and register the observations, the wave functions of particles

and

must be effectively collapsed at the moment of the respective observations. This can be achieved by conveniently disposing measurement apparatuses acting on

and

. The result of the observation of the particle

at time

t performed by the particle

will be

, as calculated by the program

controlling particle

, meanwhile the observation of the particle

by the particle

will be

, as computed by the program

on the information space of

. The actual position of particle

at time

t being

.

The observations are associated with subjective believes (estimations) of every observer about the real, well-defined, objective location of a particle. Consequently, it is natural to expect different assignments of the same observed particle’s position from different observers. Therefore, there is no contradiction in elementary Wigner’s friend-like scenarios within the framework of DAQM, so that the existence of a realist, unique world in which every particle has an objective position is compatible with the observation from different systems of unequal locations at time t (and, accordingly, hypothetical unequal properties) for the same observed particle.

Is this conclusion applicable to usual macroscopic Wigner’s friend scenarios? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to properly describe the process through which consciousness is formed in composite systems whose different parts are in turn individually conscious. This is known as the combination problem and is discussed in the following section.

5. The Combination Problem: Generating Consciousness in a Composite System

Let us consider two initially independent particles characterized in DAQM by their respective average masses, positions, algorithms, and wave functions (see

Figure 5 for a graphical representation). In DAQM, the entanglement of these two particles is defined as the process in which non-classical correlations are established between the particles by mutually copying the algorithms and data stored on their information spaces. This mutual copying enables each particle to compute on their respective information spaces the entangled wave function of the compound system that results from the entanglement process. This definition implies an entirely local characterization of entanglement (Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2019) thanks to supplementing every particle with an information space in which a randomizer and a module of anticipation are stored (see the

Appendix for a deeper discussion).

When a measurement is performed on the composite entangled system as a whole, a conscious event is induced on the entangled system (see

Figure 5). At the moment in which the erasure of the irrelevant information for the dynamics of the compound system happens, the representation of the estimated configuration of the surrounding particles is projected onto the perception screen of each particle that constitutes the entangled system. This representation is identical for both particles and consists in the estimated position of the surrounding particles as calculated by the algorithms and data of both particles that are simultaneously stored on both information spaces. It is postulated that the perspective of the representation (the origin of coordinates) is taken from the mass centre of the system, therefore, playing the role of the proto-experiential point of view of the system (a kind of elementary Cartesian theatre that is located in the set of information spaces of the entangled systems). Notice that the key element of the model is again the postulated assignment of precise information processing capacities to matter, and their role in the dynamics of the particles what endows information with an explicit physical status.

This DAQM model for consciousness seems to solve satisfactorily the combination problem through entanglement. Entanglement, as no other phenomenon, fits in with the generation of the identity of a composite, new system that cannot be reduced to the addition of the individual properties of the parts. The entangled system is described in terms of the correlations between both particles. Every component particle can no longer be characterized separately. In most interpretations of quantum mechanics, both particles, their individual properties, seem to dissolve into the compound entangled system whose state is determined by the correlations between the constituent particles.

In the defined DAQM model of entanglement, the two subjective experiences of two initially independent particles would be transformed into the subjective experience of a new objective system formed by those two particles that are now entangled. The phenomenal experience of the new-formed entangled pair would not be reducible to the addition of the individual experience of the two previously independent parts.

The possibility that entanglement solves the combination problem has already been proposed in previous studies (Chalmers,2017; D’Ariano and Faggin, 2022). The concept of entanglement looks tailored to accommodate the generation of consciousness in a compound system whose constituents were themselves independently conscious prior to the entanglement.

The hard core of the combination problem seems to admit a solution by means of the concept of entanglement. However, an essential problem persists associated with the apparently required isolation of the entangled system in order to preserve the correlations within the system from the perturbation caused by the interaction with the environment. The fragility of entanglement entails a major difficulty in the scaling up of the process when increasing the number of entangled particles within complex macroscopic biological systems. In principle, the usually complex, wet, and hot environment that is generally needed by biological systems to stay out of equilibrium in order to maintain their structures and functions (Marais et al., 2018) seems to imply extremely short decoherence timescales for collective states of ions involved in the firing rate of a neuron. A reported estimation (Tegmark, 2000) of this decoherence timescale ) was many orders of magnitude shorter than the firing timescale (Ritchie, 1995)) of a neuron. A similar conclusion was drawn for estimated decoherence timescales of neuron microtubules processes (Tegmark, 2000)) in relation to the dynamical timescale ( (Satarić, Tuszyński and Žakula, 1993)) of a microtubule excitation (excitation traversing time of a short tubule).

Short decoherence timescales in comparison with typical dynamical timescales for neuronal activity might be considered, in principle, detrimental to the option of grounding a physical description of consciousness in composite systems on quantum entanglement.

However, based on more recent studies (Hameroff and Penrose, 2014) that consider detailed stipulations of the Penrose-Hameroff theory of consciousness (Hameroff and Penrose, 2014) for the calculation of the decoherence timescale of excitations in neuron microtubules, it has been claimed (Hameroff and Penrose, 2014) a drastic increase in the estimated decoherence timescale (, see Hameroff and Penrose (2014) and reference therein). These results, as suggested by Hameroff and Penrose (2014), in addition to the extraordinary advance of quantum biology (Marais et al., 2018), unveiling the relevance of quantum phenomena in explaining fundamental functions of biological systems that cannot be satisfactorily described by classical physics, pave the way for future theoretical and experimental studies that might clarify whether quantum coherence is a central concept for describing consciousness in complex biological systems.

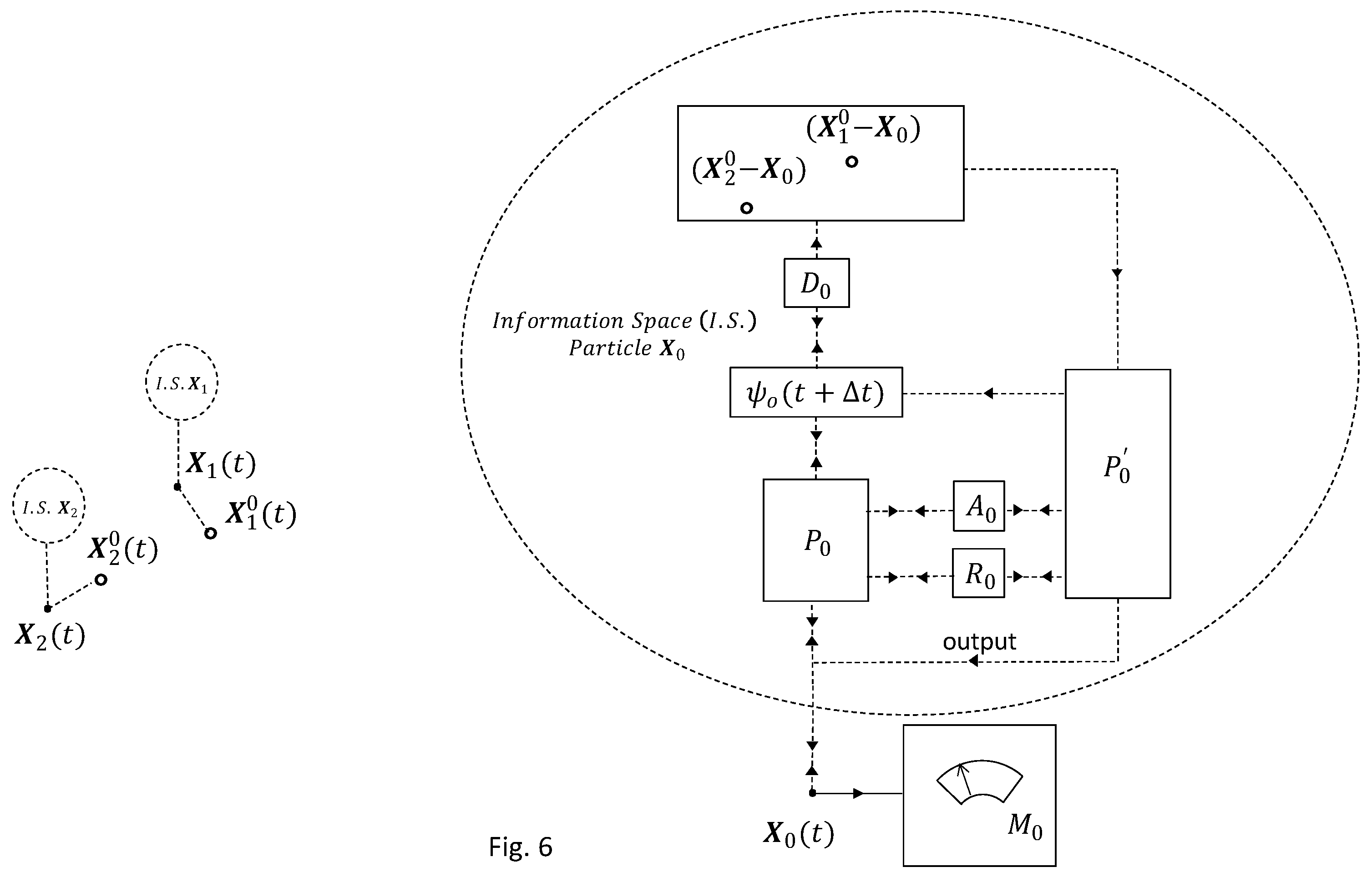

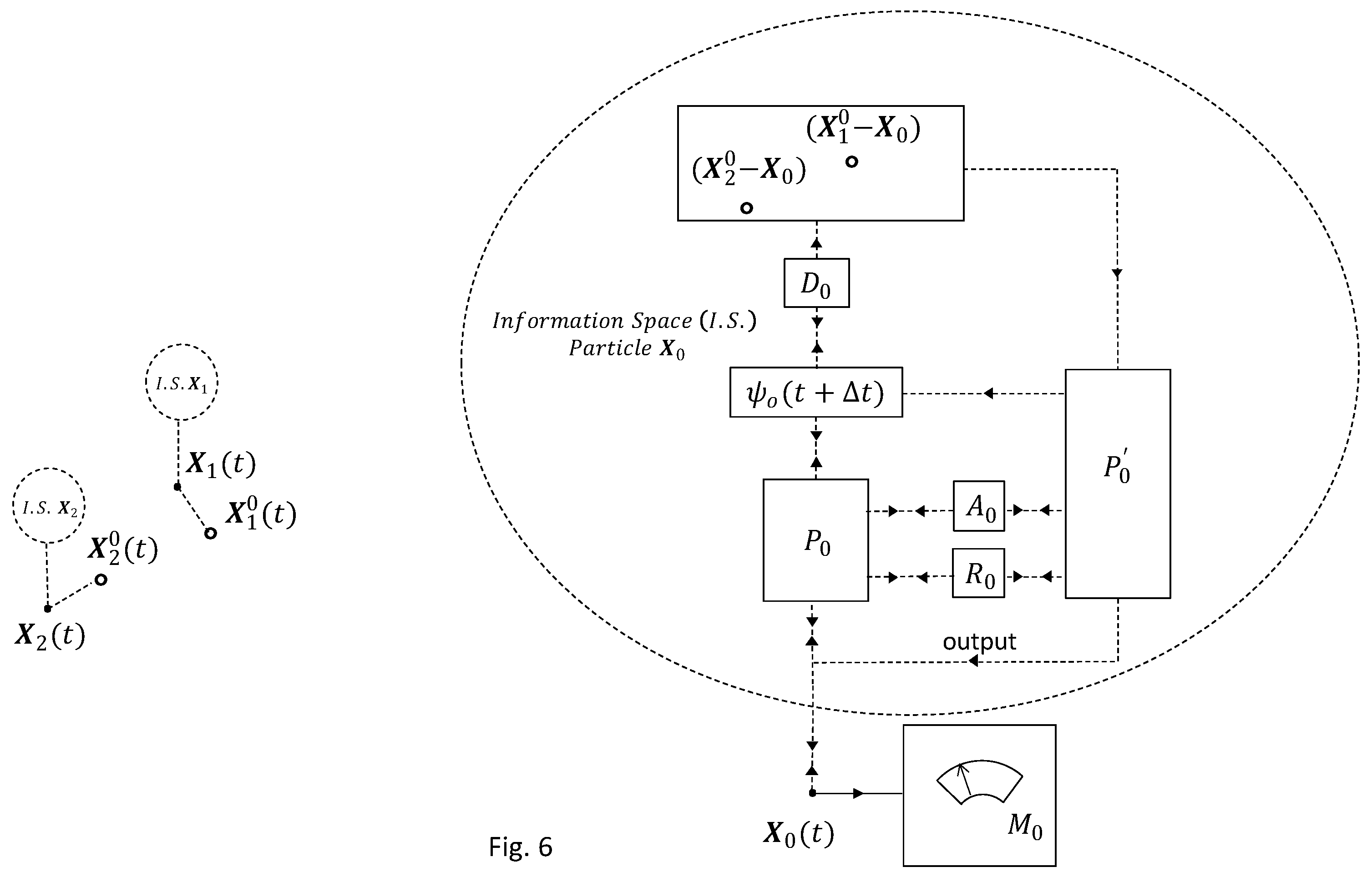

6. Doing-Otherwise Mechanism in DAQM: Consciousness Backaction on Physical Space

Consciousness as defined in the DAQM model until now seems to be an epiphenomenon, i.e., a side effect with no causal role in the physical realm. The apparent causal closure of the physical world suggests that the backaction of consciousness on matter, if any, ought to be an elusive process. In DAQM, a natural extension of the model of consciousness consists in introducing as backaction of a conscious event the transfer of the particle’s control from the original main program

to an alternative second program

that could either directly return the control to the program

or lead to a different self-interaction output when a conscious event has happened (see

Figure 6). This would be associated with a different computational route activated as a consequence of the conscious state. This alternate algorithm

endows the particle with the capacity of doing otherwise, and it constitutes a backreaction on the physical particle from the information space when an elementary event of subjective experience takes place, giving consciousness a definite influence on the material world.

However, the physical action caused by conscious events on a fundamental particle should not be distinguishable from the usual quantum behaviour predicted by the standard quantum formalism and observed in experiments. That is to say, the sequential outputs generated by the particle must be in accordance with the standard quantum behaviour of the particle either conscious events have occurred or not. Therefore, the physical action caused by conscious events on the system should be only distinguishable in the long run, i.e., in the evolutionary trajectory on the fitness landscape of possible control algorithms for a population of fundamental particles, and consequently the backaction of conscious events on matter should be only distinguishable within meaningful evolutionary time scales.

This capacity of doing otherwise might constitute a central mechanism for speeding up evolution. The reasoning is as follows. Having a set of alternative strategies (that are coded in the program

) starting from a common original control algorithm

enables the system to probe different close paths on the landscape of possible algorithms that control the behaviour of the particle. This structure might resemble the ‘regeneration process’ described by Chatterjee et al. (2013) in the framework of a theory for estimating time scales of evolutionary trajectories in biology. As studied by Chatterjee et al. (2013), this ‘regeneration process’ which requires that the starting sequence (whose key variable is its length) that undergoes adaptation –the equivalent entity in DAQM would be the particle’s control algorithm

-- both be close to the target sequence (i.e., the number of different bits, for binary sequences, between the considered two sequences be small) and can be generated repeatedly would allow biological evolution to overcome the exponential barrier and work in polynomial time (see the

Appendix for a more detailed discussion).

Further studies must be accomplished in order to check the validity of the analogy established between the results obtained by Chatterjee et al. (2013) for evolution in biology with the hypothetical doing-otherwise mechanism considered in the DAQM model of consciousness, but it seems a mechanism that is worth exploring given that it enables consciousness to play a causal role in the physical world preserving at the same time the agreement with the predictions of standard quantum mechanics and the observed experimental results.

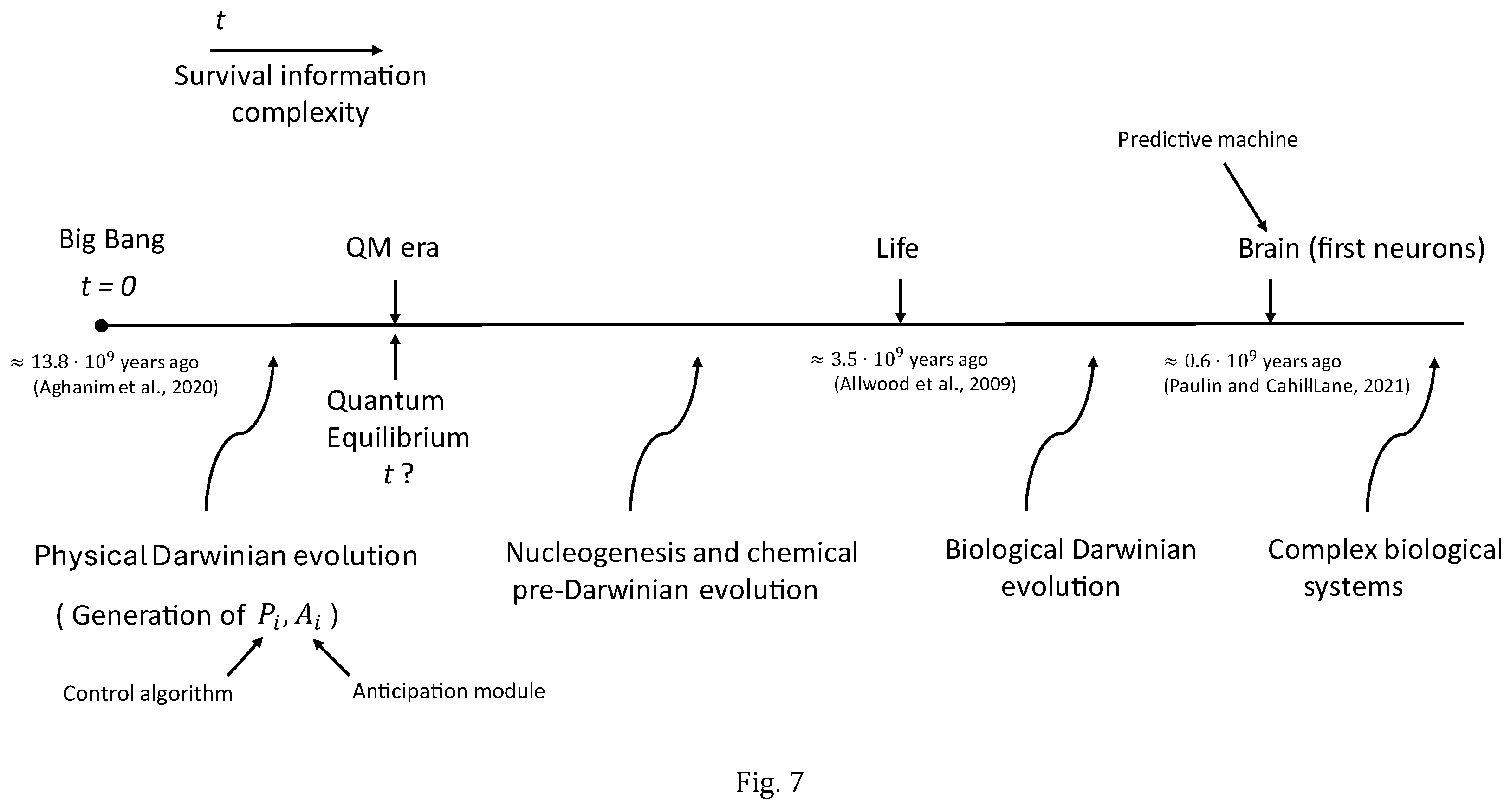

7. The Road from Elementary Microscopic Proto-Consciousness to Consciousness in Complex Biological Macroscopic Systems

The possible central role played by evolution in the generation of consciousness in complex biological systems, in particular in human beings, has been analysed by several authors (e.g., see Humphrey (2023) and Jablonka and Ginsburg (2022)). The main target of the model of consciousness in DAQM is to study the possibility that Darwinian evolution might generate high-level consciousness in complex biological macroscopic systems starting from elementary proto-consciousness events as characterized in information-theoretic DAQM fundamental particles. A first fundamental difficulty would be to determine if high-level consciousness, with all the variety and richness of phenomenological subjective experience related to sensations and feelings, might be described in terms of elementary proto-consciousness events associated with the subjective experience of the locations of the surrounding systems

6. These problems, however daunting they might be, can be categorized as “weak problems” (à la Chalmers (1995)) in comparison with the “hard problem” of consciousness (Chalmers,1995). Leaving aside the extraordinary scientifical and technological difficulty associated with these endeavours (the “weak problems” of consciousness), an initial discussion of the plausibility of the main target of the model, taking into account its features analysed in the previous sections, can be considered.

The characterization of fundamental particles in DAQM as systems that can store and process information, which in turn explicitly possesses causal power on the dynamical behaviour of the physical particles, makes these DAQM particles susceptible of Darwinian evolution, transforming the initial random behaviour of the particles (see

Figure 7) that are exclusively controlled at

by the randomizers stowed on their information spaces into quantum behaviour as the classical algorithms (

that progressively take control of the dynamics of the particles are generated by the action of Darwinian evolution under natural selection.

The plausibility of achieving a quantum equilibrium regime in which most particles in the universe were controlled by algorithms coding the rules of quantum mechanics, and generating quantum behaviour of matter in real time according to the Standard Model is further discussed in the

Appendix. However, three remarks are worth highlighting.

First, as mentioned in

Section 3, a fundamental assumption of DAQM (Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2023) is that although evolution in the short time (or microevolution) that is determined by fitness is fundamentally random due to the random mutations in the control algorithms of the particles as fundamental mechanism of variation, however evolution in the long run (or macroevolution) has a direction that is determined by the increase of complexity, in particular by the increase of the so-called survival information complexity (see the

Appendix for a mathematical definition of this magnitude) that measures, on the one hand, the capacity of a system for predicting the locations of the surrounding systems and, on the other hand, the capacity of such system for being stealthy, i.e., for minimizing the accuracy of the surrounding systems when foreseeing the position of the referred system. This function seems to gauge the quality of the information flows against survival, characterizing the fundamental general properties of a strategy for optimizing the possibilities of survival for a system.

Second, the DAQM description of the physical world recovers a rational characterization of matter behaviour even at the microscopic level. The experimentally demonstrated violation of Bell inequalities for certain systems configurations is reconciled in DAQM (Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2019) with the simultaneous existence in nature of the properties of realism (a particle has at any time a well-defined space position), causality (every non-random event has a previous cause, and the persistence in nature of random events is caused by Darwinian evolution), and locality (the speed of light is the limit for the propagation of any physical influence). These points will be further extended in the

Appendix. The weirdness of quantum mechanics is demystified in DAQM (Baladrón, 2010, 2014, 2017; Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2023) as resulting from two main elements, the in-flight calculation of the properties of a system on the information space, what explains that the result of an experiment can only be asserted when such experiment is actually performed (Peres, 1978), and the anticipation module that is the central element responsible for the non-classical correlations in Bell inequality violation experiments. The conclusion is that the systems that persist in the universe present quantum behaviour and that this behaviour is generated by Darwinian evolution under natural selection acting on populations of information-theoretic classic-like particles.

The third remark on the possible Darwinian evolution of physical systems refers to the hypothetical role played by proto-consciousness, as defined in the DAQM model for a particle, in such evolution. As previously discussed in

Section 6, proto-consciousness might accelerate the pace of evolution becoming a crucial element in explaining the transformation of an exponential problem in time, in terms of computational complexity, into a polynomial problem in time (see the

Appendix).

In DAQM, physical evolution plausibly saturated (see

Figure 7) or nearly stopped when the quantum equilibrium state was attained in the universe

7. After achieving the quantum equilibrium regime, the nucleogenesis and the synthesis of chemical compounds in the universe would be satisfactorily described by the Standard Model. The formation of heavier composite systems that in adequate environments (as presumably the Earth around 3.5 billion years ago (Allwood, 2009)) would plausibly lead to the appearance of macromolecules (chemical pre-evolution as analysed in modern chemistry (Chen and Novak, 2012; Eigen, 1971)) and ultimately life might be satisfactorily described by the increase of survival information complexity in the framework of DAQM. From this perspective a primordial alive entity would be characterized by its capability of storing and processing information (with causal power on matter) on physical parts of a system that would be able to maintain (metabolism) and replicate (inheritance) its structure and functions. The causal capacity of the information stowed on chemical compounds should now be reducible in DAQM to the causal power of the information stored on the information space of all the fundamental particles that constitute the chemical compounds. Thus, the agency of biological organisms would be a direct consequence of the postulated agency of fundamental particles in DAQM, removing one of the main difficulties in explaining the origin of life (Walker and Davies, 2013) and its early arising on Earth. Therefore, life in DAQM would be a natural result of the assumed evolutionary characteristics of matter, representing a phase transition determined by the increase in survival information complexity that drives Darwinian evolution in the long run as hypothesized in DAQM.

Biological Darwinian evolution would then start after the pre-evolutionary chemical epoch and the subsequent emergence of life. Assuming again for biological evolution as previously for physical evolution that the increase of survival information complexity would determine the direction of evolution in the long term, the development in biological systems of an anticipation module (see

Figure 7) now built with physical elements is straightforwardly implied from the definition of survival information complexity (see the

Appendix for its mathematical characterization). But precisely some modern theories (Clark, 2023, Friston et al., 2017; Kuhn, 2024; Seth and Bayne, 2022) characterize the brain as a predictive machine that builds models of the world around and of the self in order to monitor the differences between perceptual expectations and sensory inputs. The brain would work as an anticipation module in physical space for complex biological systems.

There is still a second crucial element involved in the definition of survival information complexity. It is that taking into account the characterization of quantum entanglement in DAQM (see

Section 5 and the

Appendix), the survival information complexity in a collection of particles would be increased by the entanglement of those particles. Therefore, not only the generation of a predictive physical system would favour the increase of survival information complexity, but also the spread of entanglement between the parts of that system, implying the raise of consciousness in the compound system as a whole, as it was discussed in

Section 5 when analysing the solution of the combination problem in the DAQM model of consciousness. It then seems reasonable to ponder the value of the survival information complexity (more precisely, of a term of the survival information complexity -see the

Appendix-) of a system as an adequate index to measure its degree of consciousness. However, there is a serious issue associated with the difficulty of calculating that magnitude beyond some extremely simplified modelled systems.

Summarising, consciousness in a complex biological system might be scaled up as a flow of conscious events on a dynamic quantum network constituted by a changing entangled collection of inter-neuronal components. This would require that brains were entanglement-protecting containers in spite of being wet and hot tissues in order to sustain consciousness. As pointed out in

Section 5, the Penrose-Hameroff theory (Hameroff and Penrose, 2014) proposing that microtubules might hold long range quantum coherence has received an extraordinary support in some recent experiments (Khan et al., 2024), and could explain the mechanism by which quantum coherence might be the basic phenomenon sustaining consciousness in complex biological systems.

The way in which the quantum coherence dynamical network, i.e., complex consciousness, and its interaction with the classical cognitive structure of the brain, plausibly at the interneuron level, are built, in addition to the interplay between the conscious and unconscious processes, are arduous problems to be investigated in the future.

The DAQM model leaves open the possibility that a future artificial general intelligence might be conscious since proto-consciousness is an intrinsic property of matter as hypothesized in DAQM. But the key point, from the present perspective, seems to be connected not only with the enormous difficulty of artificially developing complex enough quantum coherence dynamical networks, presumably necessary to give rise to high-degree consciousness in the framework of DAQM, but, in addition, with the development of adequate environments being able to protect that hypothetically huge quantum networks. These procedures seem to be completely out of reach for the present technological state of the art.

There is still a central question to be considered. How does consciousness act on matter in complex biological systems? As it has been already discussed for microscopic systems, the action of consciousness on matter in complex biological systems might be confined to accelerating the pace of evolution in the long run. However, a possible second crucial manner of action at the macroscopic level is especially interesting. The structure of the DAQM model based on anticipation opens up a new possibility of explaining free will in complex biological systems in a genuine compatibilist line. The main idea is that the free decision making would come from the future

8, more precisely from an anticipated future, but without violating the classical principle of causality, since in the doing-otherwise module (see

Figure 6) a self-referential model of the decision making structure of the system (a self-anticipating subroutine of

that by extension may be named

) might be built through the action of Darwinian evolution under natural selection. The construction of this self-referential subroutine would be equivalent to acquire self-awareness by the system. In this mechanism, the free-will decision event would be determined by asking from the control program

to the self-referential predicting module

what decision will be made by the own system in the immediate future. In this way, free will might constitute a real, definite survival advantage for a complex biological system.

8. Conclusions

A model for proto-consciousness as an intrinsic property of matter has been introduced. The model in turn is based on a characterization of fundamental particles as classic-like systems supplemented with an information space with the capacity of storing and processing information, and interacting with the bare particle in physical space through commanding the emission of carriers of momentum and energy (photons when the considered fundamental particles are electrons) calculated by the particle’s control algorithm. This structure transforms the fundamental particles into information-theoretic Darwinian systems susceptible of evolution under natural selection. In this physical framework, which might plausibly reconstruct the observed quantum properties of fundamental particles as is discussed in the

Appendix, the characterization of proto-consciousness as a microscopic intrinsic property of matter associated with the irreversible erasure of dynamically superfluous information conveyed by a particle on its information space is naturally incorporated.

The model of proto-consciousness that might initially be catalogued as a panpsychist model, given its characterization as a fundamental intrinsic property of matter, however, it might also properly be considered as a physicalist model because of its natural assembly into the physical structure of matter without modifying the predictions of the quantum formalism, and at the same time dissolving most of the difficulties associated with the long-standing conundrums in the foundations of quantum mechanics. In this sense, proto-consciousness might be incorporated as a new property in the list of fundamental entities and intrinsic properties that constitute the set of elements defining the ontology of the physical world.

The DAQM model of consciousness allows for a clear-cut resolution of the process of measurement (one of the deepest problems in the foundations of quantum mechanics) in the line of the de Broglie-Bohm theory and the model also introduces a precise definition of the process of observation by identifying the conditions that qualify a physical system as an observer. Therefore, the DAQM model of consciousness is a reductionist scheme that would describe any kind of physical process (potentially extensible to any kind of biological or cognitive process) in terms of quantum mechanical properties and interactions excluding the necessity of introducing (among other options) classical macroscopic systems (or, in general, systems out of the quantum realm, i.e., non-describable as mere compounds of fundamental physical particles) as fundamental elements in order to characterize a measurement or an observation.

To check the consistency of the DAQM model of consciousness, it has been applied to describe simplified basic Wigner’s friend-like scenarios in which the observers are the most elementary systems being eligible as observers (i.e., fundamental DAQM particles under the defined right conditions). These Wigner’s friend-like scenarios can be tagged as Gedankenexperiments since the considered elementary observers lack the capacity of communicating between them. The model accounts for the compatibility of the existence of one universe in which every fundamental particle has a well-defined position at any time with the possibility of apparently incongruent observations corresponding to different assignments, made by the particle playing the role of Wigner’s friend and the particle in the role of Wigner himself, referring to the position occupied by the observed system.

The model is also able to give a satisfactory solution to the combination problem for the generation of consciousness in a composite system. The set of individual consciousnesses of the constituents is transformed into the high-level consciousness of the compound in which the initial individual identity of the components is dissolved into the resultant collective entity characterized by the correlations among the constituents through the quantum entanglement as modelled in DAQM.

Quantum entanglement gives rise to a cogent description of the consciousness formation process in compound systems, but the question of how this process is implemented in the brain of complex biological systems immersed in hot and usually highly interconnected environments is raised. Recent experiments (Khan et al., 2024) have yielded promising results in which the presence of long-range quantum coherence in neuron microtubules, as was predicted in the Penrose-Hameroff theory (Hameroff and Penrose, 2014), has been detected.

A possible sketchy scenario of the evolution of the universe from the Big Bang, assuming as basic ontological entities information-theoretic fundamental particles, as characterized in DAQM, therefore, susceptible of experiencing Darwinian evolution under natural selection, has been briefly discussed. The plausible emergence of quantum behaviour in matter from the assumption of these initial random-behaved, classic-like, Darwinian fundamental particles is analysed. The picture arising from DAQM would alleviate most of the interpretational problems in the foundations of quantum mechanics by assuming both that matter possesses the intrinsic capacity of storing and processing information, and that information reciprocally has a fundamental causal control on matter. As mentioned, the approach in physical terms resembles in many respects a generalization of the de Broglie-Bohm theory, but with the additional asset of eliminating non-locality through the anticipation capability of systems developed by the action of Darwinian evolution under natural selection. On the biological side, the model might constitute the germ for explaining both the emergence of life in a continuous, natural way and the mechanism for the generation of high-level consciousness in complex biological systems with its elaborated agent attributes.

The mathematical analysis of DAQM is far from being completed, however, the expectations of the model seem to justify continuing its study. In particular, the interest of investigating the possibility of efficiently simulating quantum behaviour on classical Turing machines is supported by the recent stunning advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) exemplified by the computational development of the neural network-based model AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021) that is able to efficiently predict the correct folding of proteins within the astronomically large space of possible three-dimensional structural states from its one-dimensional amino acid sequences. Exponentially complex structural problems in quantum chemistry seemed to be the specific domain reserved to the application of the future quantum computer since the quantum advantage was patent in this type of computation. However, AlphaFold has deeply changed the perspectives on the plausibility of developing efficient computational procedures for applying classical Turing machines to the resolution of quantum problems originally considered out of their scope (Hassabis, 2024).

At the price of both assuming information processing capabilities in matter, what presents the positive counterpart of endowing information with an unequivocal physical character, and postulating proto-consciousness as an intrinsic property of fundamental particles, not only might the development of the DAQM model satisfactorily integrate high-level consciousness to the physical world, but also account for the deep conceptual issues of quantum mechanics in a rational, compelling manner, and to a great extent reduce the difficulties in understanding life and its early appearance on Earth.

Appendix A. Overview of the Darwinian Approach to Quantum Mechanics (DAQM)

The first strong hypothesis on which DAQM (Baladrón, 2010, 2014, 2017; Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2023) is built relies on the assumption that matter has an intrinsic capacity for storing and processing information. This hypothesis is articulated through a model of a fundamental particle that consists in two interacting elements. First, the bare classic-like particle in physical space characterized by its position and mass, and subject to the principles of momentum and energy conservation. And second, an information space attached to the physical particle that stores the information that transport the physical carriers (photons if the particle is an electron) of momentum, energy and information impinging on the physical particle. In addition, it is assumed that the information space has the capability of processing information by means of a classical Turing machine and also incorporates a random number generator. The output of the Turing machine determines the parameters of a carrier of momentum and energy to be emitted by the physical particle. This accounts for self-interaction of the particle what is the indication of its agency, i.e., the causal power ascribed in the DAQM to the information space on matter.

In DAQM, it is further assumed that gravitation, in a first-order approximation, does not play an essential role in the determination of the interactions and inner structures of fundamental particles, basically constituting the backdrop in which the evolution of matter interactions happen. In addition, information is assumed not to be conserved on the information spaces of the particles as it becomes manifest in the characterization of the process of measurement.

Initially, at time , all the particles, whose distribution of masses would reflect the initial conditions at the Big Bang, would be controlled by their randomizers (random number generators stored on their respective information spaces). As information starts to arrive at the particle, it is assumed that errors in the read/write operations on the Turing machine generate algorithms that progressively take over the control on the particle to the detriment of the randomizer. These random read/write errors would constitute the first source of variation for the algorithm that controls the dynamics of the particle. Different mechanisms for variation can be conceived mimicking those encountered in biological Darwinian evolution. In particular, certain processes responsible for duplication or recombination of algorithms respectively resembling biological mitosis or meiosis might have been crucial for the dynamics of particles populations at high-energy stages, but becoming much less frequent at lower-energy levels, even being undetectable at the present, hypothesized, evolutionarily stable physical scenario. These duplication and recombination methods might also have been central for the process of retention or inheritance of algorithmic variation in subsequent populations of physical particles as they are in biological Darwinian evolution. Finally, the mechanism of natural selection would act on particles populations completing the characterization of Darwinian evolution on hypothesized information-theoretic physical systems.

The central idea of DAQM is that then quantum mechanics would emerge as an evolutionarily stable attractor strategy (Rand, Wilson and McGlade, 1994) for physical systems. In addition, ideally, DAQM should predict or at least make plausible the intrinsic parameters of the fundamental particles in the Standard Model from the initial conditions at the Big Bang.

To start the analysis of DAQM, the first fundamental issue to be considered is whether beyond the canonical central role played by fitness in Darwinian evolution, in addition, there also exists a regulatory principle that determines the direction of evolution in the long run. Several schemes (Friston, 2019; Martyushev and Seleznev, 2006; Saunders and Ho, 1976) have been proposed to study this open problem in the general framework of Darwinism (schemes that might also shed light on the origin of life). Among them, those envisaging complexity as a crucial element for predicting evolution in the long term face the difficulty of finding out a satisfactory mathematical characterization that captures the essentials of the concept.

Appendix A.1. Regulating Principle: Increase of Survival Information Complexity

In DAQM, a magnitude named survival information complexity

is defined (Baladrón and Khrennikov, 2023) as a function of time for a fundamental particle

. This magnitude is meant to grasp the fundamentals

9 of an optimal strategy for survival from the perspective of information flows for a generic physical system independently of its environment, structure and functions. Two terms contribute to the survival information complexity:

The first term

evaluates the capacity of the fundamental particle

at time

for predicting the future configuration of the environment at time

and is mathematically defined as follows:

where

is the number of particles surrounding the particle

whose survival information complexity is going to be calculated,

is the real location that will be occupied by particle

(a particle in the vicinity of the studied particle

) at time

,

is the predicted position (according to the estimation of the central particle

) that would hypothetically be occupied by particle

at time

as computed on the information space of particle

at time

by the Turing machine of particle

, and

is the squared distance between the locations that will really be occupied by particle

and its surrounding particle

at time

.

The second term

measures the stealthiness of the particle

, i.e., the performance of such particle

for maximising the unpredictability of its position

for the surrounding systems

by optimising the information that the particle

sends outwards. Therefore, the magnitude is mathematically defined as follows:

where

is again the number of particles surrounding the central particle

whose survival information complexity is going to be calculated,

is the real location that will be occupied by particle

at time

,

is the estimated location of the central particle

at time

as calculated on the information space of particle

at time

by its Turing machine, and, as for equation A-2,

is the squared distance between the locations that will really be occupied by particle

and its surrounding particle

at time

.

Let us consider a system

constituted by

particles. The survival information complexity of such system

is defined as:

Now, in case the system

is being measured by the environment or by an apparatus and, therefore, experiencing a conscious event associated to the erasure of superfluous information, then the degree of consciousness of the system

at time

is determined in the DAQM by the following quantity connected with the first term of the survival information complexity of the system:

This magnitude captures the faithfulness of the representation of the environment that is subjectively experienced by the system taking also into account the structural complexity of such environment through the number of particles surrounding every constituent particle of the system .

Some weakly emergent quantities ought to be defined in future developments in terms of this microscopic quantitative characterization of the degree of consciousness or some adequate extension of it in order to provide a satisfactory quantitative description of high-level properties for human being consciousness.

Once the formalism of DAQM is equipped with a mathematical characterization of the survival information complexity, the goal of the theory is to explore the possibility of plausibly deducing the generation of quantum behaviour for the postulated initially random-behaved information-theoretic classic fundamental particles as a consequence of Darwinian evolution whose direction would be hypothetically determined by the increase of survival information complexity in the long run.

Appendix A.2. Discussion on the Derivation of the Postulates of Quantum Mechanics

A possible starting point to analyse the main properties that characterise quantum versus classical behaviour is the perspective of computation. From this point of view, the kind of problems that a quantum computer can solve is exactly the same that a classical computer can, the only difference being the degree of efficiency for certain types of problems (Timpson, 2008). In particular, optimisation schemes and simulation of quantum systems are two areas for which the quantum advantage

10 might be patent. This perspective suggests to explore quantumness in relation to classicality fundamentally as computational efficiency. Efficiency seems a natural enhancer of survival expectations in a world of limited resources. Those physical systems presenting computational efficient performances would have a substantial survival advantage. Therefore, if survival information complexity drives, as assumed in DAQM, Darwinian evolution in the long run, then it seems plausible to consider that it should propel the computational efficiency of physical systems that possess the capacity of processing information. Might the optimisation of the information flows in information-theoretic particles eventually lead to the arise of quantum behaviour in real time? Two conditions are required, namely, the development of both a classical algorithm

on the information space of the particle that codes the rules of quantum mechanics, and an efficient enough procedure that enables the classical Turing machine of the particle to emulate quantum behaviour in real time. Let us first discuss the possible deduction of the postulates of quantum mechanics (and, therefore, the possible generation of

on the information space of a DAQM particle) assuming that the increase of survival information complexity would determine the direction of Darwinian evolution in the long term.

The dynamics of a DAQM particle, as mentioned in previous sections, can be compared to a generalised Bohmian description in which the pilot wave, whose role can be envisaged in Bohmian mechanics as twofold, containing active information about the surrounding particles and guiding the own particle trajectory, is calculated by the control program stored on the information space of the particle. This particle might be considered as a ship that follows a continuous trajectory and is steered by a computer, borrowing the analogy established by Bohm and Hiley (1993) for describing the dynamics of a particle in the de Broglie-Bohm theory. The problem of determining the trajectory of a particle can then be divided into two parts. The first one is related to the way in which the data about the environment of the particle are collected, stored and analysed on the information space. The second part refers to the way in which these data are processed to compute an output that ultimately shapes the dynamical behaviour of the particle.

Appendix A.2.1. Data Storage: Complex Wave Function

A first step towards computational efficiency would be to store data optimising the computational resources and with a structure that improved the retrieval and processing speed of information. To begin with, as Frieden and Soffer (1995) point out, it is intriguing that Fisher (Fisher and Mather, 1943) himself used probability amplitudes (the square root of probabilities) instead of directly probabilities in his statistical studies of inheritance in populations of living organisms, having no connection to quantum mechanics whatsoever, arguing that it was more convenient for identifying different population classes.

To examine the process of acquiring and storing information, let us assume that a DAQM particle is endowed with a collection of methodological detectors that enable the particle to register the momentum and energy of the photons impinging on it. These detectors can be envisaged as a convenient set of yes/no methodological sensors whose output arrives at the information space of the particle. This characterisation of the particle accommodates to the description that Summhammer (1994, 2001, 2007) adopts for the generic process of acquisition of information from a system in the laboratory by means of a set of click-yielding detectors. Replacing the system in Summhammer’s model by the environment of the DAQM particle and the set of click-yielding detectors in the laboratory in Summhammer’s description by the registering detectors in the DAQM particle, the analysis and conclusions of Summhammer can be applied to the process of information gaining by a DAQM particle about its surrounding systems.

Summhammer (1994, 2001, 2007) starts his study considering that the basic phenomenology in physics is the observation of clicks in detectors, adopting a probabilistic view to interpret the observations, and assuming that the information about the world always increases through observation. The information gathered by these yes/no detectors is discrete and constituted by a finite number of bits. Summhammer’s analysis then drives to the conclusion that storing the information captured by the detectors as a complex probability amplitude vector whose module is the squared root of the relative frequency of click events for every detector maximises the predictive power of the information by ensuring that the gain of information only depends on the number of registered events and not on the nature of the registered physical parameters. The complex character of the probability amplitude, as discussed by Summhammer, is more powerful for predictions than the sheer real representation.

The incorporation of the phase of the wave function is also justified in DAQM as an element required for optimising the flows of information, because it works as a clock associated to the particle that facilitates the projection to the future of the registered information and determines in an efficient way the temporal and spatial correlation between the information captured by the particle from different locations at different times. This possible role of the wave function’s phase as a method of efficiently projecting information into the future is also pointed out in the transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics (Cramer, 1986).