Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

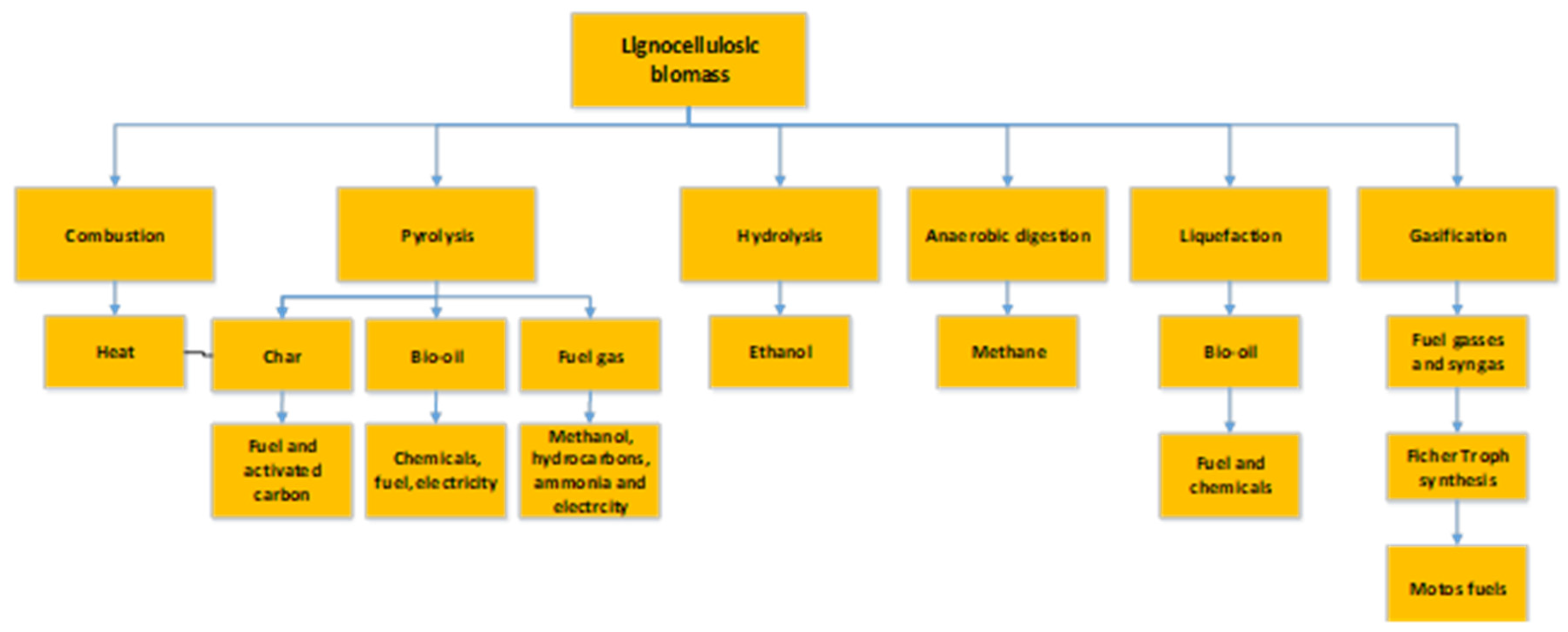

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Phase One: Comprehensive Literature Review

2.2. Phase Two: Thematic Analysis Guided by Research Questions

- RQ1: How does microwave-assisted pretreatment alter the physicochemical structure of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., cellulose crystallinity, lignin removal, and porosity enhancement)?

- RQ2: How do combined microwave-assisted pretreatments influence the physicochemical properties of lignocellulosic biomass? What are their implications for enhancing energy efficiency, product selectivity, and environmental sustainability in subsequent pyrolysis processes?

- RQ3: What are the current challenges, limitations, and future perspectives in applying microwave pretreatment at pilot and industrial scales for sustainable bioenergy production?

3. Results

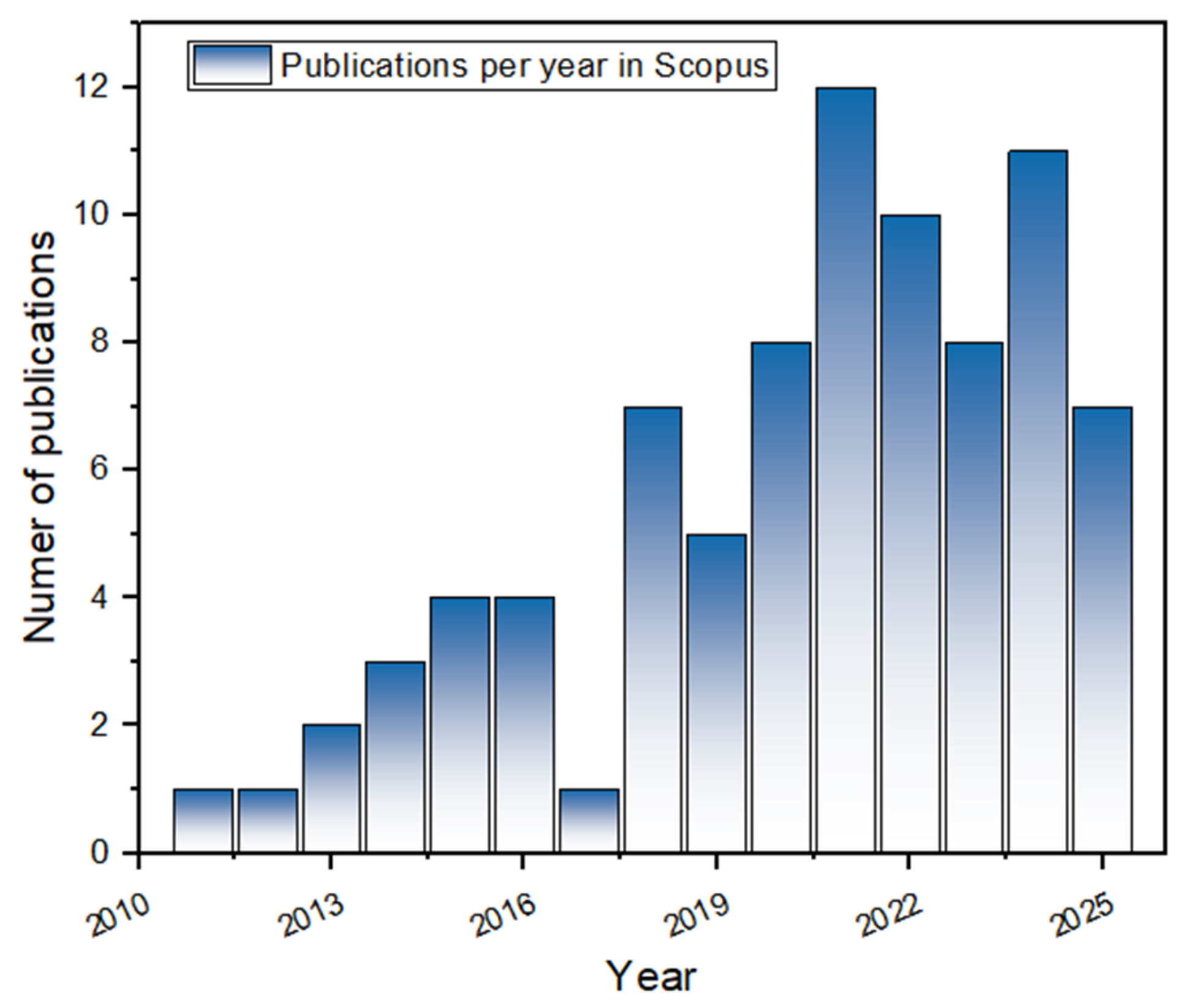

3.1. Phase One: Comprehensive Literature Review

3.1.1. Publications per Year

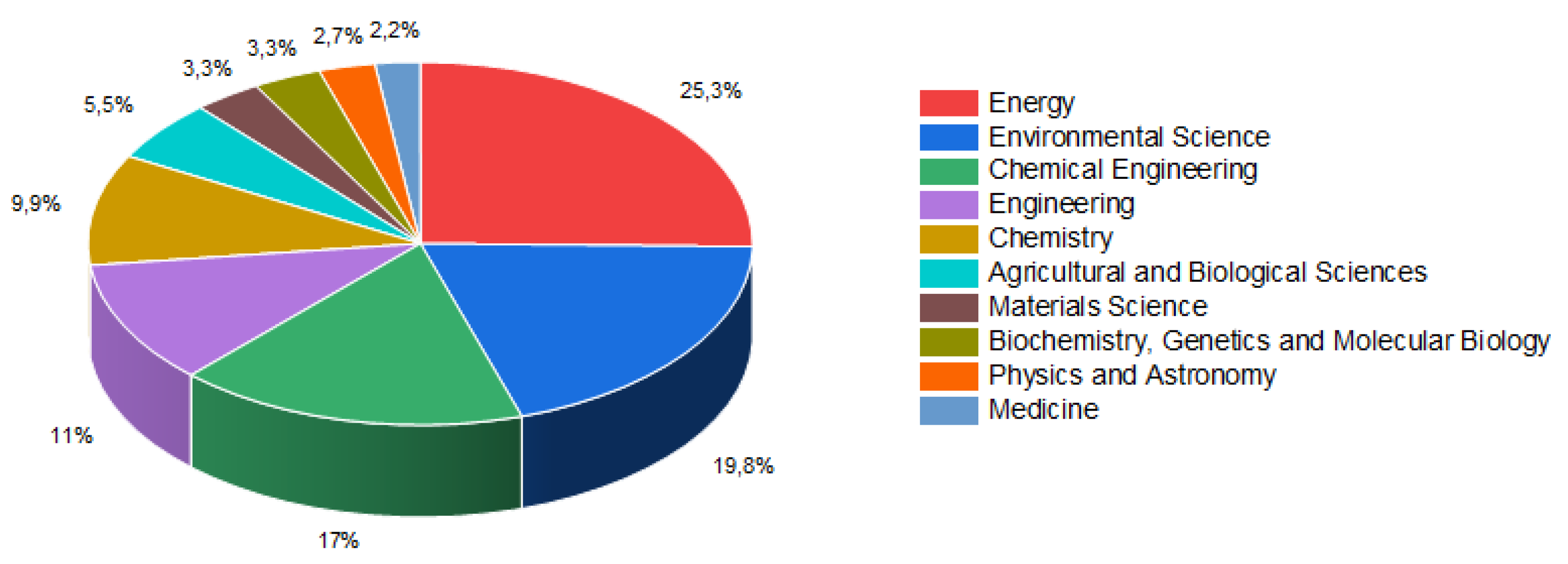

3.1.2. Subject Area

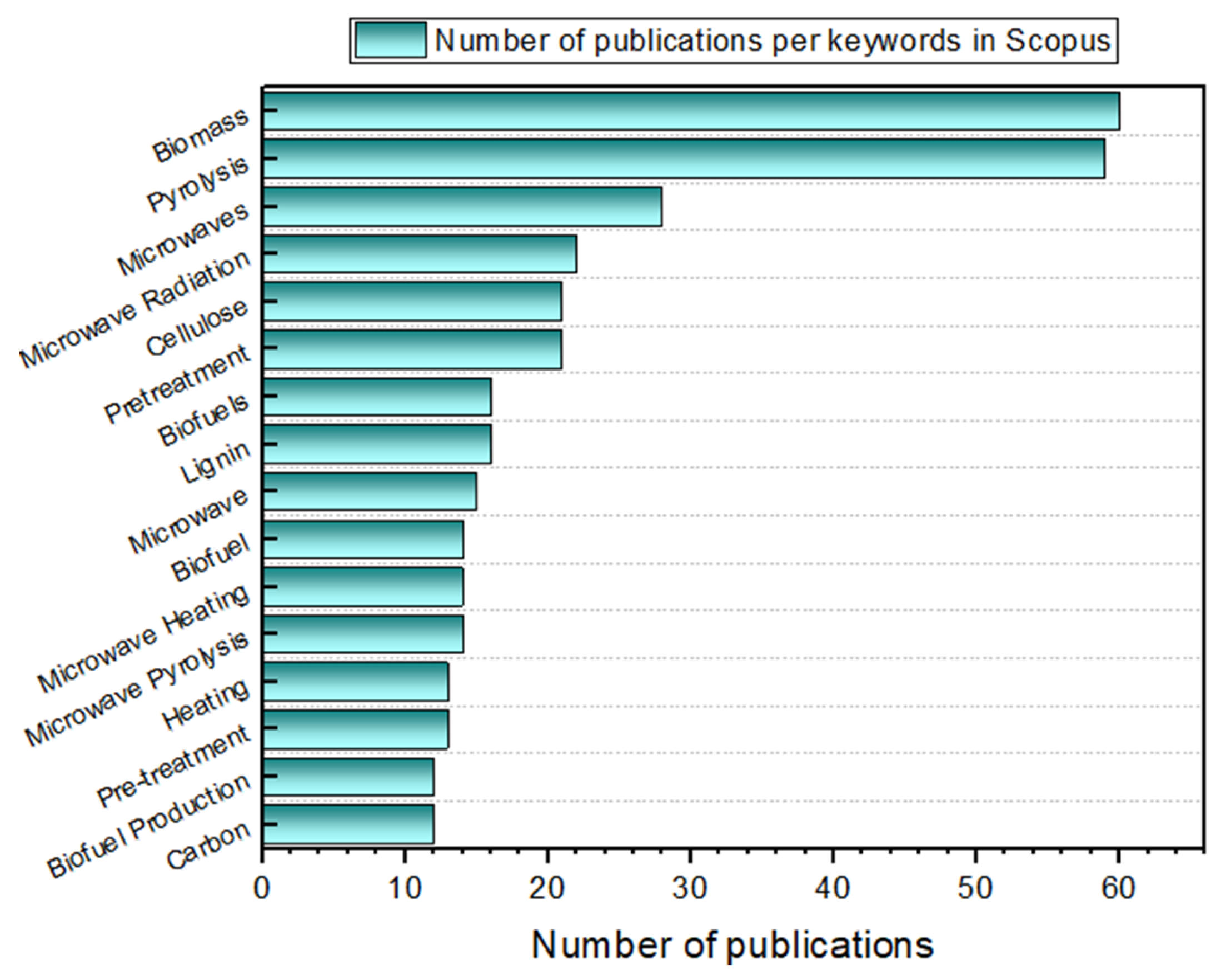

3.1.3. Keywords

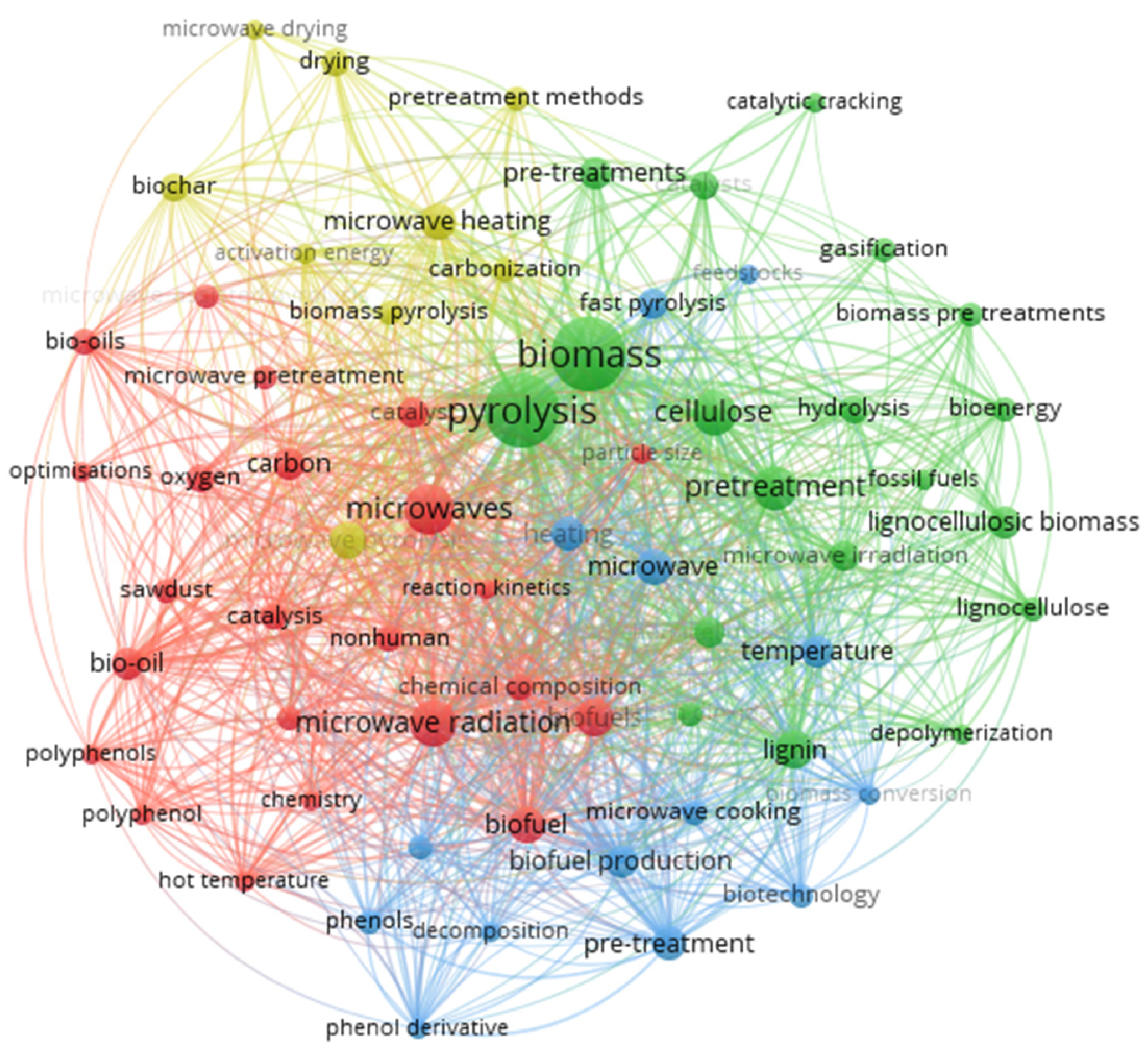

3.1.4. Correlation Keywords

3.1.5. Correlation Keyword Clusters

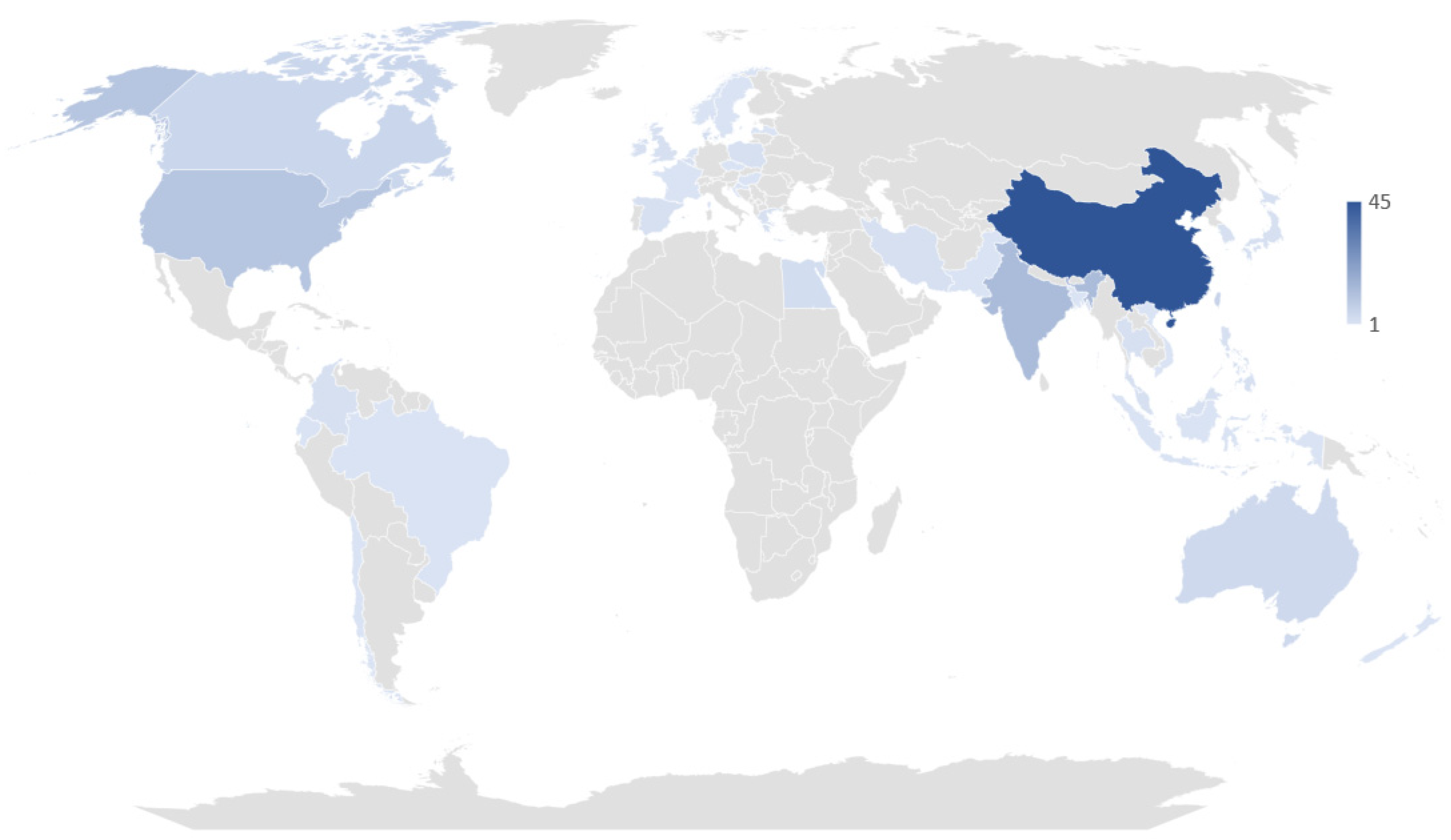

3.1.6. Publications per Country

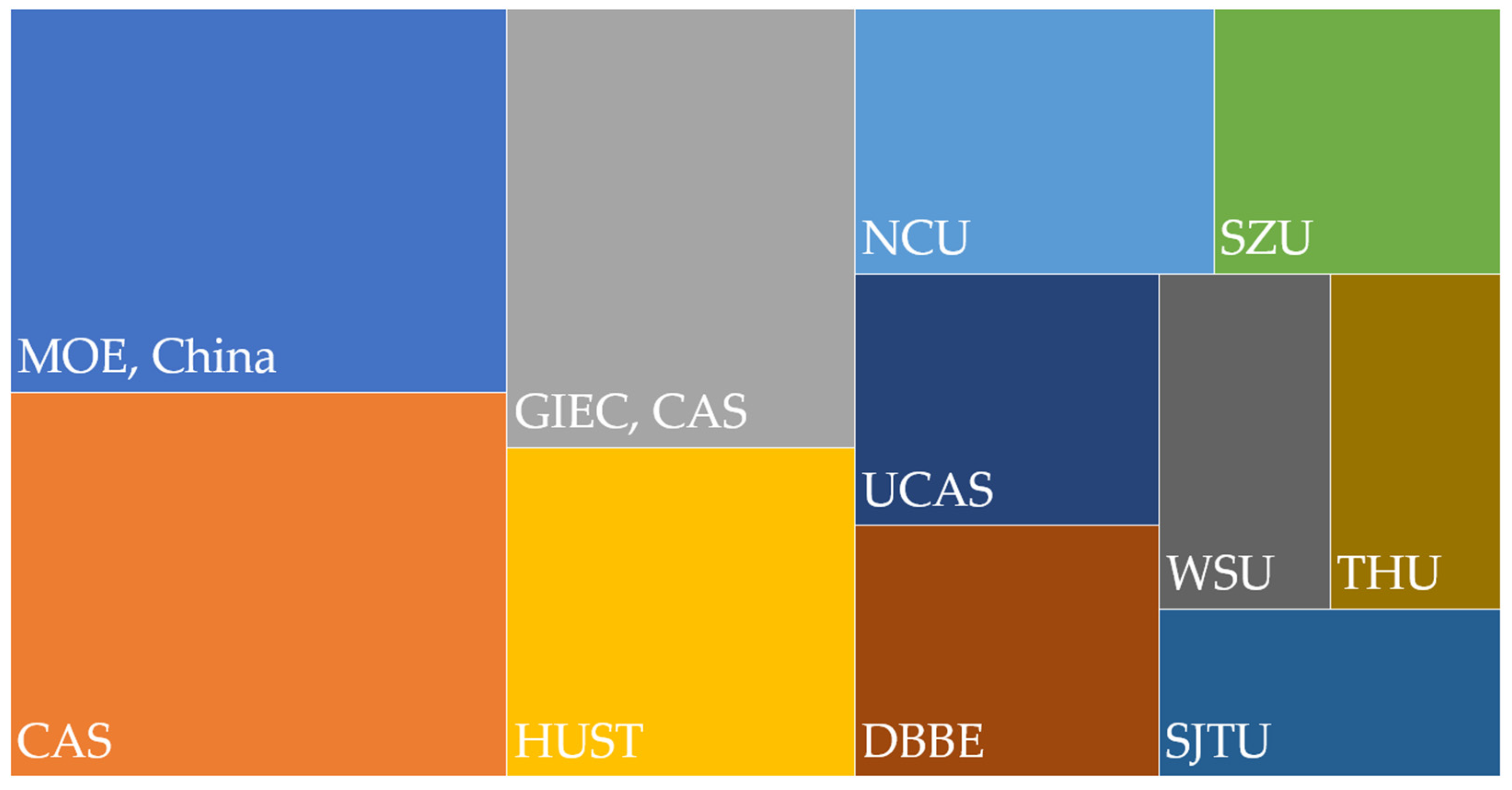

3.1.7. Publications per Affiliation

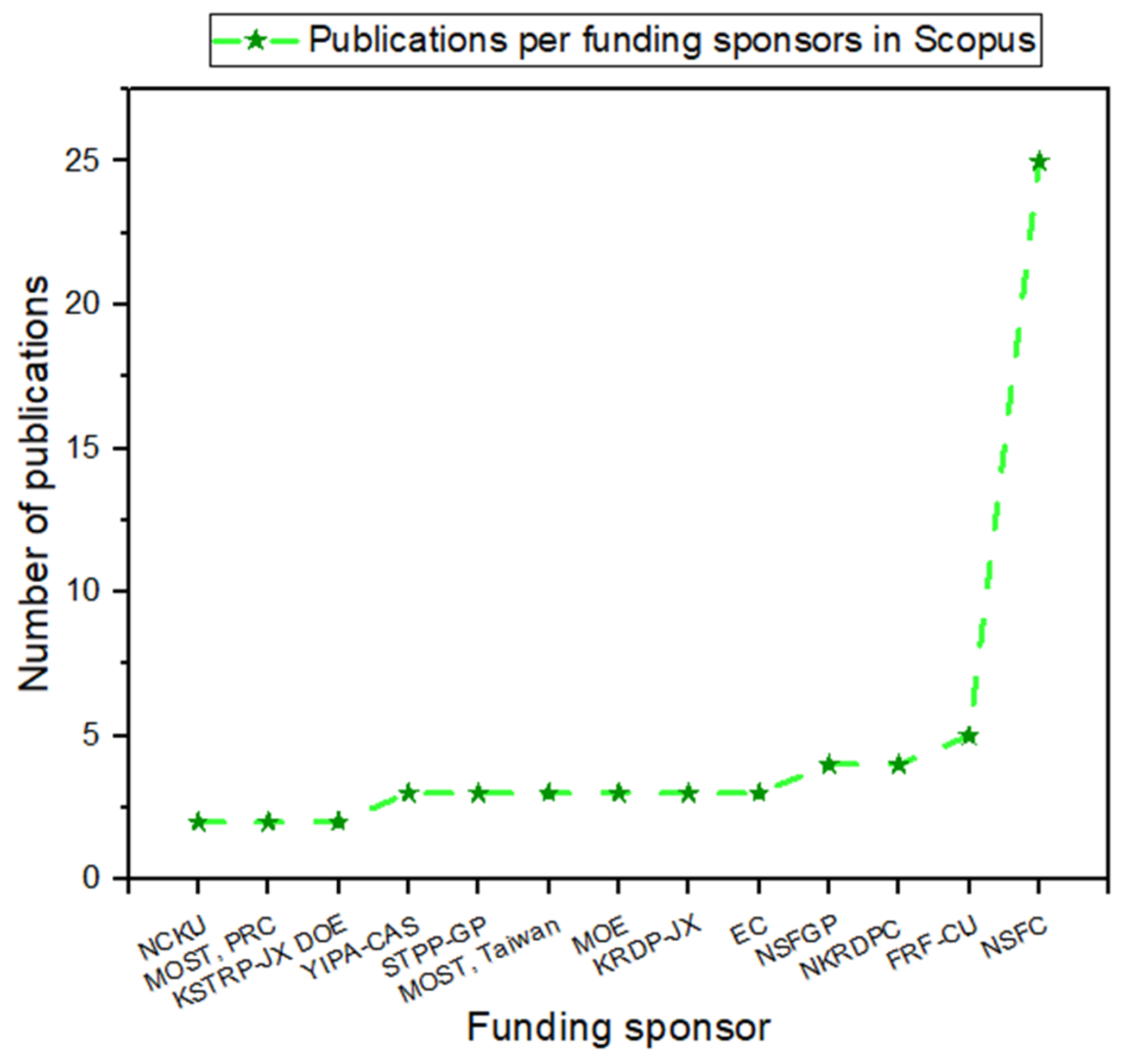

3.1.8. Publications per Funding Sponsors

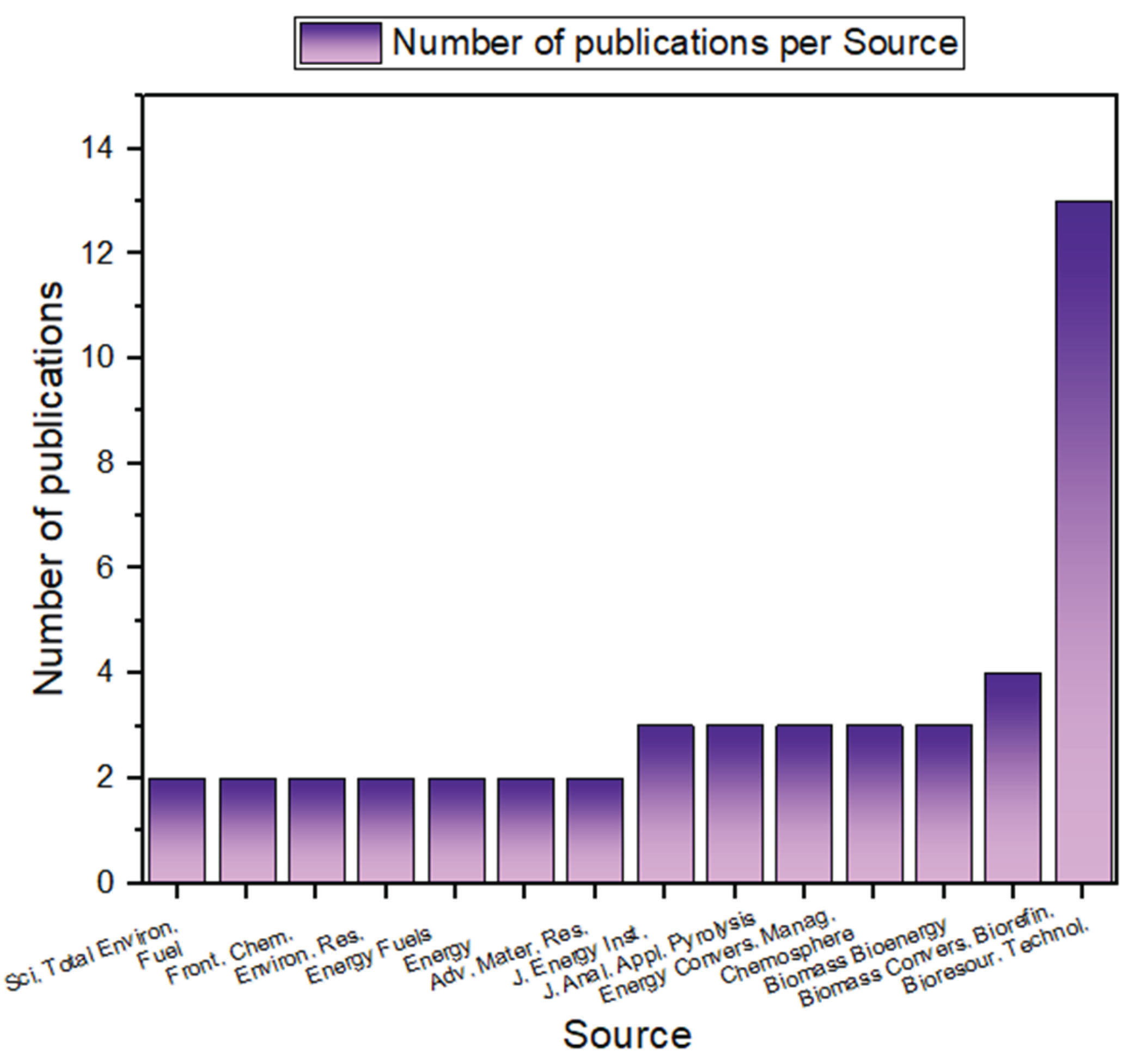

3.1.9. Publications per Source

3.2. Phase Two: Thematic Analysis Guided by Research Questions

3.2.1. How Does Microwave-Assisted Pretreatment Alter the Physicochemical Structure of Lignocellulosic Biomass?

3.2.2. How Do Combined Microwave-Assisted Pretreatments Influence the Physicochemical Properties of Lignocellulosic Biomass and What Are Their Implications for Enhancing Energy Efficiency, Product Selectivity, and Environmental Sustainability in Subsequent Pyrolysis Processes?

3.2.3. What Are the Current Challenges, Limitations, and Future Perspectives in Applying Microwave Pretreatment at Pilot and Industrial Scales for Sustainable Bioenergy Production?

4. Future Works

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orejuela-Escobar L, Venegas-Vásconez D, Méndez MÁ. Opportunities of artificial intelligence in valorisation of biodiversity, biomass and bioresidues—towards advanced bio-economy, circular engineering, and sustainability. Int J Sustain Energy Environ Res. 2024;13(2):105–13.

- Smith CJ, Forster PM, Allen M, Fuglestvedt J, Millar RJ, Rogelj J, et al. Current fossil fuel infrastructure does not yet commit us to 1.5 °C warming. Nat Commun. el 15 de enero de 2019;10(1):101.

- Daimary N, Deb B, Roy B, Ranjan RK, Mukherjee A. Sustainable biorefinery approach for the transformation of biowaste into biofuels and chemicals for the circular economy: A review. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. octubre de 2025;82:104457.

- Ahmed S, Ali A, D’Angola A. A Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations. Sustainability. el 21 de febrero de 2024;16(5):1749.

- Li F, Srivatsa SC, Bhattacharya S. A review on catalytic pyrolysis of microalgae to high-quality bio-oil with low oxygeneous and nitrogenous compounds. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. julio de 2019;108:481–97.

- Venegas-Vásconez D, Orejuela-Escobar L, Valarezo-Garcés A, Guerrero VH, Tipanluisa-Sarchi L, Alejandro-Martín S. Biomass Valorization through Catalytic Pyrolysis Using Metal-Impregnated Natural Zeolites: From Waste to Resources. Polymers. el 4 de julio de 2024;16(13):1912.

- Bridgwater, AV. Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy. marzo de 2012;38:68–94.

- Scarlat N, Fahl F, Dallemand JF, Monforti F, Motola V. A spatial analysis of biogas potential from manure in Europe. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. octubre de 2018;94:915–30.

- Fargione J, Hill J, Tilman D, Polasky S, Hawthorne P. Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt. Science. el 29 de febrero de 2008;319(5867):1235–8.

- Vamvuka, D. Bio-oil, solid and gaseous biofuels from biomass pyrolysis processes-An overview. Int J Energy Res. agosto de 2011;35(10):835–62.

- Lei H, Cybulska I, Julson J. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass and Kinetics. J Sustain Bioenergy Syst. 2013;03(04):250–9.

- Zaman CZ, Pal K, Yehye WA, Sagadevan S, Shah ST, Adebisi GA, et al. Pyrolysis: A Sustainable Way to Generate Energy from Waste. En: Samer M, editor. Pyrolysis [Internet]. InTech; 2017 [citado el 18 de agosto de 2025]. Disponible en: http://www.intechopen.com/books/pyrolysis/pyrolysis-a-sustainable-way-to-generate-energy-from-waste.

- Neumann J, Meyer J, Ouadi M, Apfelbacher A, Binder S, Hornung A. The conversion of anaerobic digestion waste into biofuels via a novel Thermo-Catalytic Reforming process. Waste Manag. enero de 2016;47:141–8.

- Alvira P, Tomás-Pejó E, Ballesteros M, Negro MJ. Pretreatment technologies for an efficient bioethanol production process based on enzymatic hydrolysis: A review. Bioresour Technol. julio de 2010;101(13):4851–61.

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Convers Manag. julio de 2001;42(11):1357–78.

- Wang S, Dai G, Yang H, Luo Z. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis mechanism: A state-of-the-art review. Prog Energy Combust Sci. septiembre de 2017;62:33–86.

- Roy P, Dias G. Prospects for pyrolysis technologies in the bioenergy sector: A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. septiembre de 2017;77:59–69.

- Nishu, Liu R, Rahman MdM, Sarker M, Chai M, Li C, et al. A review on the catalytic pyrolysis of biomass for the bio-oil production with ZSM-5: Focus on structure. Fuel Process Technol. marzo de 2020;199:106301.

- Zainan NH, Srivatsa SC, Bhattacharya S. Catalytic pyrolysis of microalgae Tetraselmis suecica and characterization study using in situ Synchrotron-based Infrared Microscopy. Fuel. diciembre de 2015;161:345–54.

- Collard FX, Blin J. A review on pyrolysis of biomass constituents: Mechanisms and composition of the products obtained from the conversion of cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. octubre de 2014;38:594–608.

- Lange, J. Lignocellulose conversion: an introduction to chemistry, process and economics. Biofuels Bioprod Biorefining. septiembre de 2007;1(1):39–48.

- Traven, L. Sustainable energy generation from municipal solid waste: A brief overview of existing technologies. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. diciembre de 2023;8:100491.

- Isahak WNRW, Hisham MWM, Yarmo MA, Yun Hin T yap. A review on bio-oil production from biomass by using pyrolysis method. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. octubre de 2012;16(8):5910–23.

- Ryu S, Lee HW, Kim YM, Jae J, Jung SC, Ha JM, et al. Catalytic fast co-pyrolysis of organosolv lignin and polypropylene over in-situ red mud and ex-situ HZSM-5 in two-step catalytic micro reactor. Appl Surf Sci. mayo de 2020;511:145521.

- Hamza M, Ayoub M, Shamsuddin RB, Mukhtar A, Saqib S, Zahid I, et al. A review on the waste biomass derived catalysts for biodiesel production. Environ Technol Innov. febrero de 2021;21:101200.

- Demirbas, A. Partly chemical analysis of liquid fraction of flash pyrolysis products from biomass in the presence of sodium carbonate. Energy Convers Manag. 2002;43:1801–9.

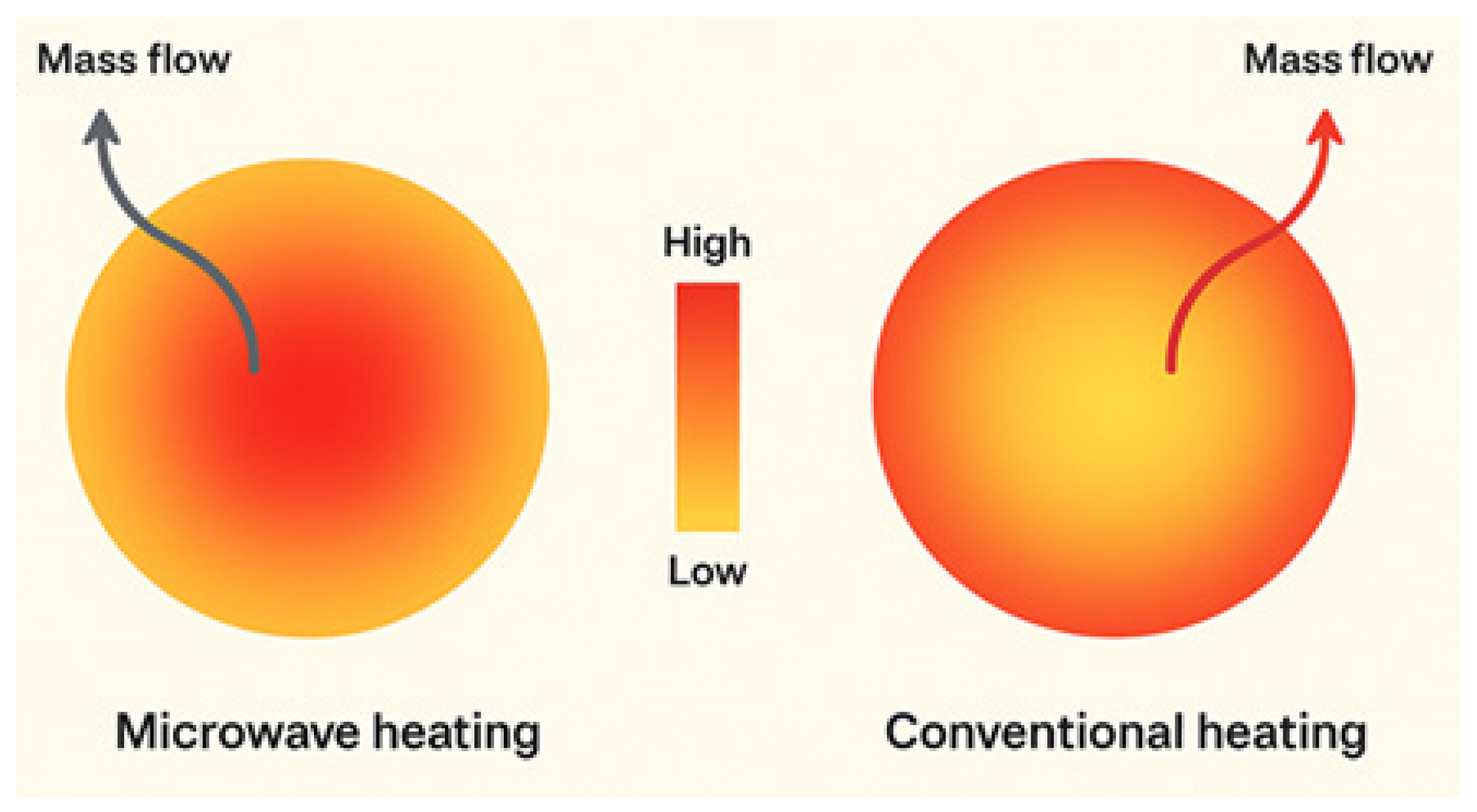

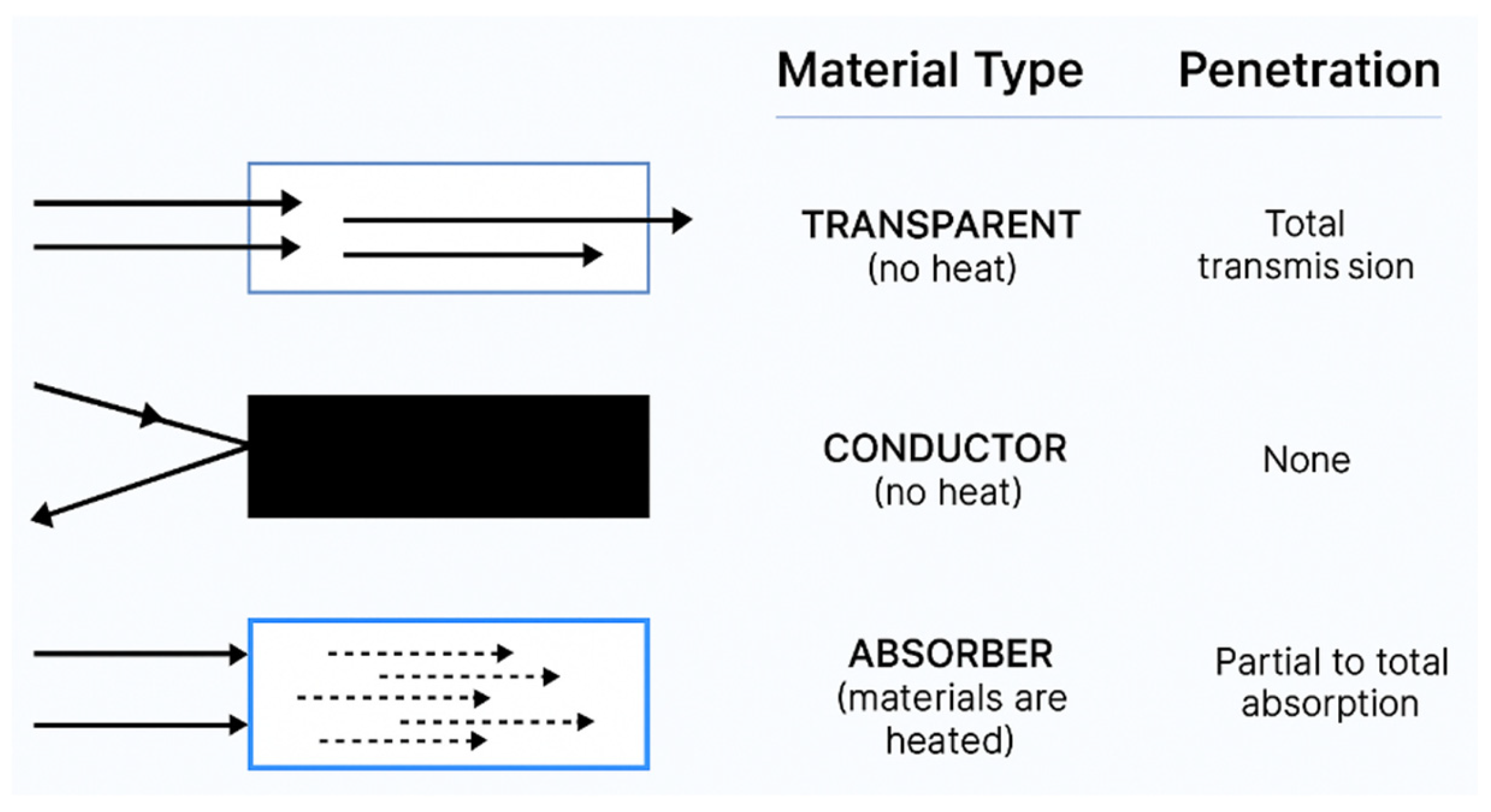

- Motasemi F, Afzal MT. A review on the microwave-assisted pyrolysis technique. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. diciembre de 2013;28:317–30.

- Conesa JA, Marcilla A, Moral R, Moreno-Caselles J, Perez-Espinosa A. Evolution of gases in the primary pyrolysis of different sewage sludges. Thermochim Acta. marzo de 1998;313(1):63–73.

- Kumar B, Bhardwaj N, Agrawal K, Chaturvedi V, Verma P. Current perspective on pretreatment technologies using lignocellulosic biomass: An emerging biorefinery concept. Fuel Process Technol. marzo de 2020;199:106244.

- Kumari D, Singh R. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes for biofuel production: A critical review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. julio de 2018;90:877–91.

- Ge L, Ali MM, Osman AI, Elgarahy AM, Samer M, Xu Y, et al. A critical review on conversion technology for liquid biofuel production from lignocellulosic biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. julio de 2025;217:115726.

- Giorcelli M, Das O, Sas G, Försth M, Bartoli M. A Review of Bio-Oil Production through Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis. Processes. el 23 de marzo de 2021;9(3):561.

- Zhang Y, Chen P, Liu S, Fan L, Zhou N, Min M, et al. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Biomass for Bio-Oil Production. En: Samer M, editor. Pyrolysis [Internet]. InTech; 2017 [citado el 19 de agosto de 2025]. Disponible en: http://www.intechopen.com/books/pyrolysis/microwave-assisted-pyrolysis-of-biomass-for-bio-oil-production.

- Bundhoo ZMA. Microwave-assisted conversion of biomass and waste materials to biofuels. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. febrero de 2018;82:1149–77.

- Roberts BA, Strauss CR. Toward Rapid, “Green”, Predictable Microwave-Assisted Synthesis. Acc Chem Res. el 1 de agosto de 2005;38(8):653–61.

- Nüchter M, Ondruschka B, Bonrath W, Gum A. Microwave assisted synthesis—a critical technology overview. Green Chem. 2004;6(3):128–41.

- Hassan SS, Williams GA, Jaiswal AK. Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol. agosto de 2018;262:310–8.

- Lei H, Ren S, Julson J. The Effects of Reaction Temperature and Time and Particle Size of Corn Stover on Microwave Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels. el 18 de junio de 2009;23(6):3254–61.

- Zhang X, Rajagopalan K, Lei H, Ruan R, Sharma BK. An overview of a novel concept in biomass pyrolysis: microwave irradiation. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2017;1(8):1664–99.

- Fernández I, Pérez SF, Fernández-Ferreras J, Llano T. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Forest Biomass. Energies. el 27 de septiembre de 2024;17(19):4852.

- Chen P, Xie Q, Addy M, Zhou W, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Utilization of municipal solid and liquid wastes for bioenergy and bioproducts production. Bioresour Technol. septiembre de 2016;215:163–72.

- Omoriyekomwan JE, Tahmasebi A, Dou J, Wang R, Yu J. A review on the recent advances in the production of carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers via microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass. Fuel Process Technol. abril de 2021;214:106686.

- Menéndez JA, Arenillas A, Fidalgo B, Fernández Y, Zubizarreta L, Calvo EG, et al. Microwave heating processes involving carbon materials. Fuel Process Technol. enero de 2010;91(1):1–8.

- Thostenson ET, Chou TW. Microwave processing: fundamentals and applications. Compos Part Appl Sci Manuf. septiembre de 1999;30(9):1055–71.

- Jin Q, Liang F, Zhang H, Zhao L, Huan Y, Daqian Song. Application of microwave techniques in analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. julio de 1999;18(7):479–84.

- Abdulridha S, Zhang R, Xu S, Tedstone A, Ou X, Gong J, et al. An efficient microwave-assisted chelation (MWAC) post-synthetic modification method to produce hierarchical Y zeolites. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. febrero de 2021;311:110715.

- Akhlisah ZN, Yunus R, Abidin ZZ, Lim BY, Kania D. Pretreatment methods for an effective conversion of oil palm biomass into sugars and high-value chemicals. Biomass Bioenergy. enero de 2021;144:105901.

- Ge S, Yek PNY, Cheng YW, Xia C, Wan Mahari WA, Liew RK, et al. Progress in microwave pyrolysis conversion of agricultural waste to value-added biofuels: A batch to continuous approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. enero de 2021;135:110148.

- Osepchuk, JM. Microwave Power Applications. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech. 2002;50:975–85.

- Cundy, CS. Microwave Techniques in the Synthesis and Modification of Zeolite Catalysts. A Review. Collect Czechoslov Chem Commun. 1998;63(11):1699–723.

- Mushtaq F, Mat R, Ani FN. A review on microwave assisted pyrolysis of coal and biomass for fuel production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. noviembre de 2014;39:555–74.

- Haque, KE. Microwave energy for mineral treatment processes—a brief review. Int J Miner Process. julio de 1999;57(1):1–24.

- Jones DA, Lelyveld TP, Mavrofidis SD, Kingman SW, Miles NJ. Microwave heating applications in environmental engineering—a review. Resour Conserv Recycl. enero de 2002;34(2):75–90.

- Huang YF, Chiueh PT, Lo SL. A review on microwave pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Sustain Environ Res. mayo de 2016;26(3):103–9.

- Ke L, Zhou N, Wu Q, Zeng Y, Tian X, Zhang J, et al. Microwave catalytic pyrolysis of biomass: a review focusing on absorbents and catalysts. Npj Mater Sustain. el 22 de julio de 2024;2(1):24.

- Singh R, Lindenberger C, Chawade A, Vivekanand V. Unveiling the microwave heating performance of biochar as microwave absorber for microwave-assisted pyrolysis technology. Sci Rep. el 22 de abril de 2024;14(1):9222.

- Erythropel HC, Zimmerman JB, De Winter TM, Petitjean L, Melnikov F, Lam CH, et al. The Green ChemisTREE: 20 years after taking root with the 12 principles. Green Chem. 2018;20(9):1929–61.

- Foong SY, Chan YH, Yek PNY, Lock SSM, Chin BLF, Yiin CL, et al. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis in biomass and waste valorisation: Insights into the life-cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA). Chem Eng J. julio de 2024;491:151942.

- Hoang AT, Nižetić S, Ong HC, Mofijur M, Ahmed SF, Ashok B, et al. Insight into the recent advances of microwave pretreatment technologies for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into sustainable biofuel. Chemosphere. octubre de 2021;281:130878.

- Syed NR, Zhang B, Mwenya S, Aldeen AS. A Systematic Review on Biomass Treatment Using Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis under PRISMA Guidelines. Molecules. el 20 de julio de 2023;28(14):5551.

- Liang J, Xu X, Yu Z, Chen L, Liao Y, Ma X. Effects of microwave pretreatment on catalytic fast pyrolysis of pine sawdust. Bioresour Technol. diciembre de 2019;293:122080.

- Qiu B, Wang Y, Zhang D, Chu H. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass to high-value products: Factors assessment, mechanism analysis, and critical issues proposal. Chem Eng J. octubre de 2024;498:155362.

- Mahmood H, Moniruzzaman M, Yusup S, Muhammad N, Iqbal T, Akil HMd. Ionic liquids pretreatment for fabrication of agro-residue/thermoplastic starch based composites: A comparative study with other pretreatment technologies. J Clean Prod. septiembre de 2017;161:257–66.

- Kumar AK, Sharma S. Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess. diciembre de 2017;4(1):7.

- Ramos Maldonado M, Duarte Sepúlveda T, Gatica Neira F, Venegas-Vásconez D. Machine learning para predecir la calidad del secado de chapas en la industria de tableros contrachapados de Pinus radiata. Maderas Cienc Tecnol [Internet]. el 29 de julio de 2024 [citado el 2 de diciembre de 2024];26. Disponible en: https://revistas.ubiobio.cl/index.php/MCT/article/view/6661.

- Mahmood H, Moniruzzaman M, Iqbal T, Khan MJ. Recent advances in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and value-added products. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. diciembre de 2019;20:18–24.

- Kumari D, Singh R. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes for biofuel production: A critical review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. julio de 2018;90:877–91.

- Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, Van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. diciembre de 2002;66(4):739–739.

- Ryu HW, Kim DH, Jae J, Lam SS, Park ED, Park YK. Recent advances in catalytic co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastic waste for the production of petroleum-like hydrocarbons. Bioresour Technol. agosto de 2020;310:123473.

- Rezania S, Oryani B, Cho J, Talaiekhozani A, Sabbagh F, Hashemi B, et al. Different pretreatment technologies of lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production: An overview. Energy. mayo de 2020;199:117457.

- Sankaran R, Parra Cruz RA, Pakalapati H, Show PL, Ling TC, Chen WH, et al. Recent advances in the pretreatment of microalgal and lignocellulosic biomass: A comprehensive review. Bioresour Technol. febrero de 2020;298:122476.

- Anu, Kumar A, Rapoport A, Kunze G, Kumar S, Singh D, et al. Multifarious pretreatment strategies for the lignocellulosic substrates for the generation of renewable and sustainable biofuels: A review. Renew Energy. noviembre de 2020;160:1228–52.

- Li H, Qu Y, Yang Y, Chang S, Xu J. Microwave irradiation—A green and efficient way to pretreat biomass. Bioresour Technol. enero de 2016;199:34–41.

- Beig B, Riaz M, Raza Naqvi S, Hassan M, Zheng Z, Karimi K, et al. Current challenges and innovative developments in pretreatment of lignocellulosic residues for biofuel production: A review. Fuel. marzo de 2021;287:119670.

- Mankar AR, Pandey A, Modak A, Pant KK. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresour Technol. agosto de 2021;334:125235.

- Hu Z, Wen Z. Enhancing enzymatic digestibility of switchgrass by microwave-assisted alkali pretreatment. Biochem Eng J. marzo de 2008;38(3):369–78.

- Budarin VL, Clark JH, Lanigan BA, Shuttleworth P, Macquarrie DJ. Microwave assisted decomposition of cellulose: A new thermochemical route for biomass exploitation. Bioresour Technol. mayo de 2010;101(10):3776–9.

- Sólyom K, Mato RB, Pérez-Elvira SI, Cocero MJ. The influence of the energy absorbed from microwave pretreatment on biogas production from secondary wastewater sludge. Bioresour Technol. diciembre de 2011;102(23):10849–54.

- Eskicioglu C, Terzian N, Kennedy K, Droste R, Hamoda M. Athermal microwave effects for enhancing digestibility of waste activated sludge. Water Res. junio de 2007;41(11):2457–66.

- Devi A, Singh A, Bajar S, Pant D, Din ZU. Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: An in-depth analysis of pre-treatment methods, fermentation approaches and detoxification processes. J Environ Chem Eng. octubre de 2021;9(5):105798.

- Haldar D, Purkait MK. A review on the environment-friendly emerging techniques for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: Mechanistic insight and advancements. Chemosphere. febrero de 2021;264:128523.

- Shinoj S, Visvanathan R, Panigrahi S, Kochubabu M. Oil palm fiber (OPF) and its composites: A review. Ind Crops Prod. enero de 2011;33(1):7–22.

- Tsubaki S, Ozaki Y, Azuma J. Microwave-Assisted Autohydrolysis of Prunus mume Stone for Extraction of Polysaccharides and Phenolic Compounds. J Food Sci [Internet]. marzo de 2010 [citado el 21 de agosto de 2025];75(2). Disponible en: https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01466.x.

- Gabhane J, Prince William SPM, Vaidya AN, Mahapatra K, Chakrabarti T. Influence of heating source on the efficacy of lignocellulosic pretreatment—A cellulosic ethanol perspective. Biomass Bioenergy. enero de 2011;35(1):96–102.

- Shi J, Pu Y, Yang B, Ragauskas A, Wyman CE. Comparison of microwaves to fluidized sand baths for heating tubular reactors for hydrothermal and dilute acid batch pretreatment of corn stover. Bioresour Technol. mayo de 2011;102(10):5952–61.

- Dhua S, Mishra P. Microwave drying: A novel technique in the sustainable development of corn starch-based aerogel and its comparison with traditional freeze dried aerogel. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. septiembre de 2025;720:137135.

- Zaker A, Chen Z, Wang X, Zhang Q. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of sewage sludge: A review. Fuel Process Technol. mayo de 2019;187:84–104.

- Prasiwi AD, Trisunaryanti W, Triyono T, Falah II, Santi D, Marsuki MF. Synthesis of Mesoporous Carbon from Merbau Wood (Intsia spp.) by Microwave Method as Ni Catalyst Support for α-Cellulose Hydrocracking. Indones J Chem [Internet]. el 11 de abril de 2019 [citado el 21 de agosto de 2025]; Disponible en: https://journal.ugm.ac.id/ijc/article/view/34189.

- Anoopkumar AN, Reshmy R, Aneesh EM, Madhavan A, Kuriakose LL, Awasthi MK, et al. Progress and challenges of Microwave-assisted pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass from circular bioeconomy perspectives. Bioresour Technol. febrero de 2023;369:128459.

- Mikulski D, Kłosowski G. Delignification efficiency of various types of biomass using microwave-assisted hydrotropic pretreatment. Sci Rep. el 16 de marzo de 2022;12(1):4561.

- Mikulski D, Kłosowski G. High-pressure microwave-assisted pretreatment of softwood, hardwood and non-wood biomass using different solvents in the production of cellulosic ethanol. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. el 7 de febrero de 2023;16(1):19.

- Venegas-Vásconez D, Arteaga-Pérez LE, Aguayo MG, Romero-Carrillo R, Guerrero VH, Tipanluisa-Sarchi L, et al. Analytical Pyrolysis of Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus globulus: Effects of Microwave Pretreatment on Pyrolytic Vapours Composition. Polymers. el 17 de septiembre de 2023;15(18):3790.

- Cui JY, Zhang N, Jiang JC. Effects of Microwave-Assisted Liquid Hot Water Pretreatment on Chemical Composition and Structure of Moso Bamboo. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. el 7 de febrero de 2022;9:821982.

- Kaur K, Phutela UG. Enhancement of paddy straw digestibility and biogas production by sodium hydroxide-microwave pretreatment. Renew Energy. julio de 2016;92:178–84.

- Zheng A, Zhao Z, Huang Z, Zhao K, Wei G, Jiang L, et al. Overcoming biomass recalcitrance for enhancing sugar production from fast pyrolysis of biomass by microwave pretreatment in glycerol. Green Chem. 2015;17(2):1167–75.

- Keshwani DR, Cheng JJ. Microwave-based alkali pretreatment of switchgrass and coastal bermudagrass for bioethanol production. Biotechnol Prog. mayo de 2010;26(3):644–52.

- Shengdong Z, Yuanxin W, Yufeng Z, Shaoyong T, Yongping X, Ziniu Y, et al. Fed-Batch simultaneous saccharification and ferementation of microwave/acid/alkali pretreated rice straw for production of ethanol. Chem Eng Commun. mayo de 2006;193(5):639–48.

- Nair LG, Agrawal K, Verma P. Organosolv pretreatment: an in-depth purview of mechanics of the system. Bioresour Bioprocess. el 11 de agosto de 2023;10(1):50.

- Akhtar N, Goyal D, Goyal A. Characterization of microwave-alkali-acid pre-treated rice straw for optimization of ethanol production via simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF). Energy Convers Manag. junio de 2017;141:133–44.

- Marx S, Ndaba B, Chiyanzu I, Schabort C. Fuel ethanol production from sweet sorghum bagasse using microwave irradiation. Biomass Bioenergy. junio de 2014;65:145–50.

- Alio MA, Tugui OC, Vial C, Pons A. Microwave-assisted Organosolv pretreatment of a sawmill mixed feedstock for bioethanol production in a wood biorefinery. Bioresour Technol. marzo de 2019;276:170–6.

- Li J, Dai J, Liu G, Zhang H, Gao Z, Fu J, et al. Biochar from microwave pyrolysis of biomass: A review. Biomass Bioenergy. noviembre de 2016;94:228–44.

- Torrado I, Neves BG, Da Conceição Fernandes M, Carvalheiro F, Pereira H, Duarte LC. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal processing of pine nut shells for oligosaccharide production. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. septiembre de 2024;14(17):20751–60.

- Dai L, He C, Wang Y, Liu Y, Yu Z, Zhou Y, et al. Comparative study on microwave and conventional hydrothermal pretreatment of bamboo sawdust: Hydrochar properties and its pyrolysis behaviors. Energy Convers Manag. agosto de 2017;146:1–7.

- Hassan SS, Williams GA, Jaiswal AK. Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol. agosto de 2018;262:310–8.

- Aylin Alagöz B, Yenigün O, Erdinçler A. Ultrasound assisted biogas production from co-digestion of wastewater sludges and agricultural wastes: Comparison with microwave pre-treatment. Ultrason Sonochem. enero de 2018;40:193–200.

- Darji D, Alias Y, Mohd Som F, Abd Razak NH. Microwave heating and hydrolysis of rubber wood biomass in ionic liquids. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. noviembre de 2015;90(11):2050–6.

- Zhu Z, Macquarrie DJ, Simister R, Gomez LD, McQueen-Mason SJ. Microwave assisted chemical pretreatment of Miscanthus under different temperature regimes. Sustain Chem Process. diciembre de 2015;3(1):15.

- Fodah AEM, Abdelwahab TAM. Process optimization and technoeconomic environmental assessment of biofuel produced by solar powered microwave pyrolysis. Sci Rep. el 22 de julio de 2022;12(1):12572.

- Allende S, Brodie G, Jacob MV. Breakdown of biomass for energy applications using microwave pyrolysis: A technological review. Environ Res. junio de 2023;226:115619.

- Osman AI, Farghali M, Ihara I, Elgarahy AM, Ayyad A, Mehta N, et al. Materials, fuels, upgrading, economy, and life cycle assessment of the pyrolysis of algal and lignocellulosic biomass: a review. Environ Chem Lett. junio de 2023;21(3):1419–76.

- Ethaib, S. Microwave-assisted pretreatment for lignocellulosic biomass energy conversion path. Bioresour Technol Rep. diciembre de 2024;28:102006.

- Li S, Li C, Shao Z. Microwave pyrolysis of sludge: a review. Sustain Environ Res. el 1 de abril de 2022;32(1):23.

- Ding W, Ji X, Tian Z, Liu S, Zhang F, Zhou J. Effect of microwave hydrothermal pretreatment on dissolution of composite components in Acacia wood and subsequent pulping performance. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(191).

- Zhang X, Ma X, Yu Z, Shen G. Effect of microwave pretreatment on pyrolysis of chili straw: thermodynamics, activation energy, and solid reaction mechanism. Env Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31(10):15759–69.

| Conventional Heating | Microwave Heating |

| Energy transfer | Energy conversion |

| Surface heating by conduction, convection, and radiation | Volumetric and uniform core heating at the molecular level |

| Absence of hot spots | Presence of hot spots |

| Slow, inefficient, and limited | Fast and efficient |

| Lower electricity-to-heat conversion efficiency | Higher electricity-to-heat conversion efficiency |

| Non-selective | Selective |

| Less dependent on material properties | Dependent on material properties |

| Less controllable heating | Precise and controllable heating |

| Less flexible process | Flexible process |

| Less portable equipment | Portable equipment |

| Polluting process | Less polluting process |

| Higher thermal inertia | Lower thermal inertia |

| Combination | Key Findings | Ref. |

| Alkali | Rice straw pretreated with 4% NaOH and microwaves for 30 min showed 65% reduction in lignin and 88.7% reduction in silica, resulting in a 54.7% increase in biogas production. | [94] |

| Sugarcane bagasse treated with Ca(OH)2 under microwaves improved cellulose crystallinity and led to higher bio-oil yields in subsequent pyrolysis. | [64] | |

| Corn stover pretreated with NaOH and microwaves showed 72% delignification and increased enzymatic digestibility, enhancing downstream pyrolysis performance | [91] | |

| Corn cob treated with glycerol and microwaves at 150 W for 18 min exhibited ~189-fold increase in levoglucosan yield compared to untreated pyrolysis, due to effective delignification, demineralization, and selective removal of hemicellulose and lignin fractions. | [95] | |

| Grass pretreated with microwaves and alkalis (Na2CO3, Ca(OH)2, NaOH) enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis, yielding 82% glucose and 63% xylose. | [96] | |

| Acid | Rice straw pretreated with acid and alkali under microwaves removed hemicellulose and lignin, achieving ethanol yield of 61.3% (29.1 g/L). | [97] |

| Hardwood residues treated with dilute H2SO4 and microwaves (175 °C) increased cellulose recovery to >80% and reduced lignin content, facilitating higher yields of volatiles. | [98] | |

| Rice straw treated with acetic acid and NaOH under microwaves for simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) increased cellulose from 42.54% to 60.07%, while hemicellulose and lignin decreased to 14.90% and 4.52%, respectively. | [99] | |

| Sweet sorghum bagasse pretreated with 50 g/kg H2SO4 under microwaves at 180 W for 20 min reached total sugar yield of 820 g/kg and ethanol yield of 480 g/kg. | [100] | |

| Sawmill residues (fir, Scots pine, Douglas fir) pretreated with H2SO4 under microwaves (ethanol-water 60:40, 175 °C, 0.25% H2SO4) achieved cellulose yield of 82% ± 3% and purity of 71% ± 3%. | [101] | |

| Hydrothermal | Increased biomass moisture enhances microwave absorption via dielectric heating. | [102] |

| Microwave-assisted hydrothermal pretreatment enhanced hemicellulose solubilization in pinewood, improving sugar recovery and reducing char formation. | [103] | |

| Bamboo sawdust hydrothermally pretreated with microwaves removed more acetyl groups from hemicellulose than conventional hydrothermal treatment, resulting in 9.82% higher glucopyranose content and 4.12% lower acid content in pyrolysis. | [104] | |

| Ultrasound | Combined microwaves and ultrasound reduce particle size, increase exposed surface area, and improve accessibility of cellulose, hemicellulose, and oligosaccharides. | [74,105] |

| Combined MW-ultrasound pretreatment of agricultural residues enhanced porosity and surface exposure, boosting enzymatic hydrolysis and subsequent pyrolysis yields. | [55] | |

| Agricultural residues (olive and grape pomace) and wastewater sludge pretreated with microwaves and ultrasound showed enhanced surface area, selective lignin and wax degradation, improving enzymatic hydrolysis for biogas production. | [106] | |

| Ionic Liquids | Rubberwood treated with microwaves and ionic liquids (1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate & 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate) at 200 W achieved 85% biomass dissolution and 52% sugar yield. | [107] |

| Pretreatment of rubberwood with imidazolium-based ionic liquids under MW achieved >80% biomass dissolution and improved sugar release. | [108] |

| Environmental/Sustainability Advantage | Why It Helps (Mechanism) | Ref. |

| Lower process energy via rapid, volumetric heating | Microwaves couple directly with dipoles/ions, cutting heat-up times and thermal losses vs. convective heating. | [59] |

| Less pre-drying / size-reduction energy | MAP tolerates higher moisture and larger particle sizes, avoiding energy-intensive drying and fine milling. | [55] |

| Integration of renewables | Microwaves are inherently electric—easy coupling to PV/wind or hybrid systems | [109] |

| Improved product selectivity → lower downstream upgrading burden | Selective, in-core heating and catalyst/absorber synergy yield higher-quality, lower-oxygen bio-oil, reducing hydrotreating severity and associated emissions. | [110] |

| Potential life-cycle GHG reduction (with biochar co-product) | Biochar/activated carbon from MAP can act as carbon sequestration; MAP systems can be designed for distributed conversion to cut transport emissions. | [111] |

| Reduced reagent intensity when paired with tunable pretreatments | MAP enhances physicochemical pretreatments (acid/alkali/organosolv/hydrothermal), enabling milder conditions or shorter times for delignification/demineralization. | [59,112] |

| Lower emissions from process intensification | Compact reactors, rapid start/stop, and targeted heating minimize off-gas/cooling loads relative to large, thermally massive units. | [55] |

| Valorization of wet/heterogeneous wastes | MAP handles moist, variable feedstocks (sludge, residues), enabling diversion from landfilling and fossil displacement. | [113] |

| Scalable routes to higher-surface-area biochar (adsorbents/soil) | Faster heating and localized hotspots can yield chars with higher surface area, supporting soil health, pollutant capture, and circular uses. | [110] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).