Introduction

In the context of twenty-first-century education and the digital transformation of professional domains, the ability to self-regulate one’s own learning and thinking has become more than a desirable skill—it is a foundational competency for lifelong learning, scientific reasoning, and adaptive expertise. Metacognitive competence, defined as the capacity to plan, monitor, and evaluate one’s own cognitive processes, plays a central role in preparing learners to transfer knowledge, adapt strategies, and navigate increasingly complex problem spaces.

The GaReCoReA model emerged from this educational imperative. Its initial development was inspired by theoretical insights and reflective experiences gathered during my coursework with Prof. Mihai Stanciu, whose experimental research on metacognitive competence in Romanian university students helped operationalise planning, monitoring, and regulatory strategies as concrete pedagogical targets (Stanciu et al., 2011). His work provided a strong foundation for recognising metacognition not only as a cognitive trait but as a teachable, assessable, and improvable educational outcome. Building on this framework, we began to explore how reflective and strategic guidance could be embedded into teaching—particularly for veterinary students—through structured activities such as gamification, pre/post-lab prompts, decision trees, and open-ended problem solving.

The development of this article reflects our shared professional perspectives: one grounded in veterinary and life sciences education, and the other informed by engineering and digital systems thinking. While the GaReCoReA model was initially created in the context of laboratory teaching and student-centred learning in the health sciences, our collaborative reflections revealed its potential relevance across disciplines. In both fields, students are increasingly challenged to make decisions in uncertain, multi-step environments—whether in diagnostic reasoning or industrial problem-solving. Yet, many struggle not with content alone, but with the ability to organise their thinking, set goals, and reflect strategically. This observation highlighted the need for an adaptable metacognitive framework that could help learners manage cognitive complexity and transfer learning across contexts.

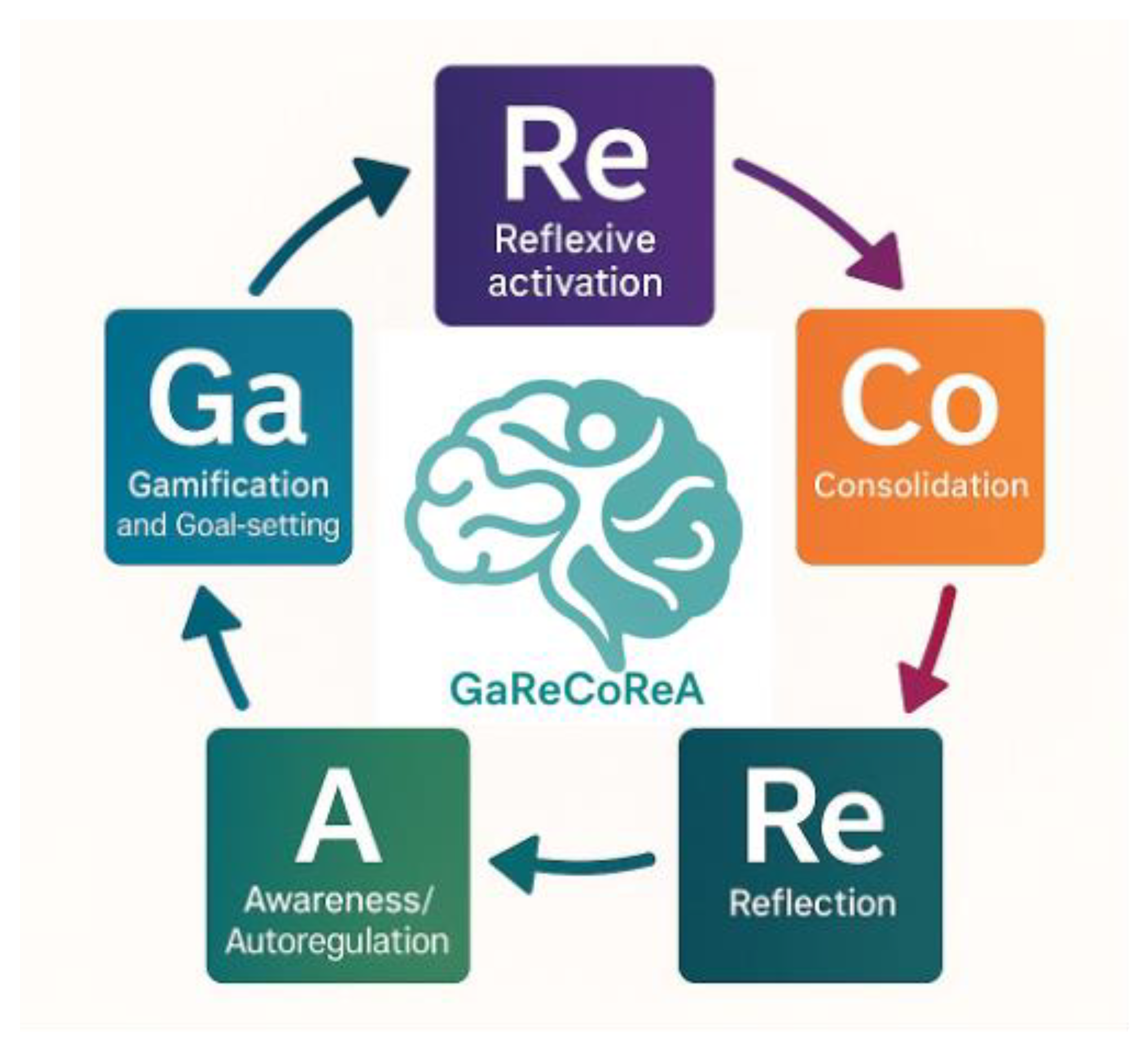

To address this gap, we propose the GaReCoReA model—a theoretically grounded and pedagogically actionable framework for developing metacognitive competence in higher education. Developed through iterative teaching, doctoral supervision, and simulation research, GaReCoReA integrates five key components: Gamification and Goal-setting, Reflexive Activation, Consolidation, Reflection, and Awareness/Autoregulation. The model has been applied in physical learning environment and is designed to promote structured self-regulation in open-ended, simulation-based, or case-driven tasks.

This article seeks to articulate the theoretical constructs underpinning GaReCoReA, illustrate its pedagogical application, and provide evidence-based rationale for its integration into simulation-based curricula. It is intended for educators designing interactive learning experiences, doctoral students seeking to develop academic autonomy, and researchers working on metacognitive interventions. Our central research questions are: (1) How can metacognitive competence be systematically developed in simulation-based learning environments? (2) How does the GaReCoReA model support the transfer and reinforcement of self-regulated learning strategies across disciplinary domains?

Theoretical Foundations of Metacognitive Competence

Although the term metacognition was introduced relatively late in the specialist literature, concerns related to cognitive self-reflection phenomena have been present since the early decades of the 20th century. Numerous authors – including Markman, Schoenfeld, Cardiner, Büchel, Cerghit, Cucoș, Joița, and Neacșu – have analysed this complex construct from both theoretical perspectives and through experimental investigations, proposing various nuanced definitions.

The simplest definition could be: metacognition is the cognition about cognition (Fleming & Frith, 2014). In the predominant understanding, metacognition is defined as the ability to reflect on one’s own learning process, including the monitoring and self-regulation of study strategies (Rahnev, 2025). It plays a crucial role in self-regulated learning, which involves setting goals, selecting appropriate strategies, and evaluating progress (Gul & Shehzad, 2012). Students who develop strong metacognitive skills adapt better to academic and professional demands. J.H. Flavell is considered the pioneer of systematic research in the field of metacognition. In his studies on metamemory (1976), he defines metacognition as “knowledge about one’s own cognitive processes, their products, and anything related to them.” Flavell emphasizes that metacognition involves not only awareness of these processes but also the ability to actively evaluate, regulate, and intentionally organize them in accordance with specific cognitive goals. His vision laid the foundation for numerous subsequent theoretical models that integrate metacognition into the architecture of learning self-regulation.

The concept of self-regulated learning has gained increasing importance since the 1980s, unifying research on cognitive strategies, metacognition, motivation, and affectivity into a coherent model. This construct highlights the active role of the individual in setting learning goals, selecting and applying appropriate strategies, and self-evaluating progress in relation to study tasks. Zimmerman defines self-regulated learning as a cyclical process comprising three stages: goal setting, progress monitoring, and strategy adjustment. This model emphasizes the interaction between personal, behavioral, and contextual factors in the learning process. Feedback gained from previous experiences is used to continuously improve educational approaches, enabling students to adapt their strategies and respond effectively to academic and professional demands (McPherson et al., 2017).

In contemporary educational psychology, metacognitive competence is closely aligned with self-regulated learning (SRL) models. Metacognitive competence comprises three interrelated domains: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive regulation, and metacognitive experiences (Efklides, 2008; Flavell, 1979).

Metacognitive knowledge refers to awareness of one’s cognitive abilities and strategies;

regulation includes monitoring, planning, and controlling learning behaviours; and

experiences are the affective and cognitive reflections that occur during problem-solving. These dimensions interact dynamically and cyclically, particularly in self-directed and simulation-based environments, where learners must make decisions, evaluate real-time feedback, and reflect on performance iteratively (Zimmerman, 2002). According to Pintrich (2000) and Zimmerman (2002), self-regulated learning involves forethought (goal setting and planning), performance (strategy use and monitoring), and reflection (evaluation and adaptation), as shown in

Figure 1.

Metacognitive strategies, such as self-questioning, checking for comprehension, and strategy shifting, are essential to all three self-regulated learning phases. Importantly, empirical research consistently links these strategies to improved academic outcomes (Dignath & Büttner, 2008; Vrugt & Oort, 2008).

The teaching methods that support the development of metacognitive competences include, but are not limited to: post-reflective exercises, which enhance problem-solving skills and critical thinking (Reinhard et al., 2022), gamification, an effective technique for motivating students and stimulating active engagement in the learning process (Alomari et al., 2019), and chaining strategies, combining goal-directed learning methods (forward chaining) and reverse analysis of the learning process (backward chaining) to facilitate knowledge transfer (Abdelshiheed, Hostetter, Yang, et al., 2023).

The use of flashcard-type worksheets as post-reflective exercises can be an effective strategy for developing metacognition among veterinary medicine students. Flashcards promote active self-testing, information retrieval, and spaced repetition—cognitive processes essential for raising awareness of one’s knowledge level and identifying gaps.

In the study conducted by Ward and Vengrin (2021), students used digital flashcards to review content from a veterinary cardiology course. It was observed that this method enabled them to focus on individual concepts and adjust their learning strategies according to difficulties encountered. Even though academic performance did not differ significantly from other study methods, many students appreciated the flashcards for offering a quick and focused opportunity to reflect on their understanding— a key aspect in the development of metacognitive thinking (Ward & Vengrin, 2021).

Gamification is defined as the techniques used in non-game settings (Deterding et al., 2011) and is used in higher education to increase students motivation and engagement in a learning task, for a better learning outcome (Alomari et al., 2019). Gamification, through elements such as scoring, immediate feedback, and competition, helps students better understand their own strengths and weaknesses. For example, the online game developed by Starke and collaborators, featuring 3D animations of horse gaits, was used to train students in recognizing lameness. The results showed a significant improvement in visual discrimination capacity, an important aspect of metacognitive thinking. In the absence of a sufficient number of real clinical cases, virtual simulations become essential. The Equine Virtual Farm game, for instance, allows the integration of theoretical knowledge and practical skills in a safe and interactive environment. The game provides 3D simulations of horses, including their gait (to identify lameness), decision-making interfaces for clinical scenarios, and interactive activities in which students can learn to make clinical decisions, make mistakes without real consequences, and reflect on their own decision-making processes (Nassar, 2014).

In addition, applications such as CowSim or Illinois Cow AR offer the possibility to practice handling large animals, especially for students from urban environments with no prior experience. These platforms allow for repeated exercises and adaptation to different scenarios, facilitating self-regulated learning (Free et al., 2022).

Although further research is needed regarding the complete transfer of these skills to real veterinary practice, existing studies suggest that students trained in gamified environments are faster, more confident, and more effective in real clinical situations.

Chaining strategies—forward chaining and backward chaining—are behavioral techniques used to learn complex tasks by breaking them down into simpler steps. Combining these methods can facilitate knowledge transfer, improve adaptability and make the learning process more efficient. Forward chaining involves teaching a behavioral sequence beginning with the first step: the individual learns and can master the first step before proceeding to the next, continuing in this manner until the entire task is completed. This approach is beneficial when the early steps are easier to understand or when the aim is to build positive behavioral momentum from the beginning of the learning process. In contrast, backward chaining starts with the last step of the sequence: the individual is assisted in completing all the steps except for the last, which they perform independently. Once the final step is mastered, the process moves to the penultimate step, and so on, working backward toward the first step. This method is useful when the task’s outcome offers an immediate reward, reinforcing motivation and positive association with success. Combining the two strategies can optimize the learning process, allowing adaptation to individual needs and task complexity. For instance, in teaching metacognitive skills, alternating between forward and backward chaining has been shown to be effective in enhancing the acquisition and transfer of skills (Abdelshiheed, Hostetter, Yang, et al., 2023). These metacognitive development strategies are also commonly used in therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders, by breaking down a complex process into simple, easy-to-understand and follow steps (Pratt & Steward, 2020). The degree of success of these strategies depends on the individual’s abilities and their level of verbal language comprehension. The use of these strategies applies to everyday situations and requires the individual’s ability to carry out a task by performing all the indicated steps. One of the most accessible examples for veterinary medicine students is putting on a lab coat, the surgical gloves or performing the handwashing.

The GaReCoReA model builds upon these theoretical foundations and synthesizes five core components essential for developing metacognitive competence (

Figure 2).

This model is particularly relevant in simulation-based learning contexts, where learners interact with dynamic systems (e.g., clinical decision-making simulators) that require real-time adjustments and strategic thinking. Without metacognitive scaffolding, such complex environments can overwhelm learners and limit conceptual understanding (Ifenthaler et al., 2012). In the microbiology laboratory, this model allows an interactive and challenging way of identification the bacterial species, the students work in groups, and they decide together which is the best option for getting to the right diagnostic.

Furthermore, GaReCoReA is designed to integrate with the principles of cognitive apprenticeship and constructivist learning, where knowledge is co-constructed through active engagement, reflection, and instructor modelling. These principles are vital in doctoral education, where learners are expected to transition from knowledge consumers to autonomous researchers capable of critically evaluating their own work.

To evaluate the rate of metacognitive model implementations, we recommend using simultaneous measurement of metacognition (“think aloud protocols and systematic observations”)(Greene et al., 2013) – which allows the real-time and direct evaluation, and the questionnaire method – which is more time consuming and has negative (students may be reluctant to express ideas and experiences, they might not fully understand the tasks) and positive (larger groups of students can be objectively evaluated, assure equality for all students) aspects (Akturk & Sahin, 2011).

Thus, the theoretical basis of GaReCoReA is represented by a convergence of metacognitive research, simulation pedagogy, and learning theory. By formalizing this framework, we aim to support educators and learners alike in developing sustainable, self-regulated learning practices that extend beyond academic tasks into professional and research contexts.

Educational Context and Methodological Clarification

The GaReCoReA model was implemented during the Special Bacteriology laboratory course in the second year of the Veterinary Medicine programme at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. A total of 72 students were enrolled in the course, and the model was integrated throughout the semester as part of a broader effort to enhance metacognitive competence and strategic learning during laboratory sessions.

The model was introduced progressively, with each laboratory session incorporating structured prompts, gamified tasks, reflection strategies, and chaining techniques. Students engaged with flashcards, guided decision-making in group work, and case-based learning scenarios. These activities were carefully aligned with the five components of the GaReCoReA framework and embedded into the laboratory workflow.

To monitor progress and encourage self-regulated learning, we conducted three evaluations throughout the semester. These included formative assessments that focused on diagnostic reasoning, interpretation of microbiological results, and the application of theoretical knowledge in simulated clinical contexts. At the end of the semester, students were invited to complete a metacognitive self-assessment questionnaire. The aim was to capture their reflections on goal-setting, strategy use, self-monitoring, and the usefulness of reflection prompts during practical tasks.

Although this was not a controlled study, the combination of structured observation, formative assessments, and student feedback provided valuable insights. The final results were encouraging: students showed a higher level of engagement, performed well in practical and theoretical evaluations, and demonstrated increased awareness of their own learning processes. These outcomes suggest that integrating the GaReCoReA model into simulation-based laboratory education can effectively support the development of metacognitive strategies, even in complex and time-constrained curricular environments.

The Garecorea Model: Design and Cognitive Scaffolds

This article employs a conceptual research methodology grounded in systematic literature synthesis and reflective educational practice. Unlike empirical studies that rely on experimental or survey-based data collection, conceptual development seeks to construct theoretical models by integrating key findings from existing scholarly work. For the GaReCoReA model, we reviewed peer-reviewed studies on metacognition, critical thinking, goal orientation, academic achievement, and simulation-based learning—drawing from both cognitive science and pedagogical domains.

The bibliographic research included empirical studies on metacognitive regulation (Gotoh, 2016), goal orientation (Gul & Shehzad, 2012), self-regulated learning (Vrugt & Oort, 2008), and simulation-based competencies in professional education. Each component of the GaReCoReA model was derived through thematic analysis of how metacognitive strategies contribute to learning performance, particularly in environments where learners are expected to problem-solve, reflect, and adapt in real-time.

This methodology also builds upon design-based research principles, in which theoretical models are iteratively tested and refined within authentic educational contexts—in this case, simulation-based laboratories and seminars in veterinary education. Reflective practitioner logs, student feedback, and performance data from simulation activities were used to triangulate theoretical insights and refine the five components of the model. Additionally, the constructive alignment principle (Biggs, 1996), guided the articulation of each GaReCoReA domain to specific learning outcomes, teaching activities, and assessment strategies. This ensures that the model is not only theoretically coherent but also pedagogically actionable.

The GaReCoReA model—an acronym for Gamification and Goal setting, Reflexive activation, Consolidation, Reflection, Awareness/Autoregulation —was developed as a pedagogical framework to explicitly cultivate metacognitive competence in higher education. In this section, we elaborate on the five components and propose actionable strategies for their implementation in higher education, particularly in engineering, healthcare, and doctoral simulation environments.

Theoretical Rationale Goal-setting is foundational to metacognitive and motivational theories of learning (Vrugt & Oort, 2008). It activates forethought, directs attention, and improves persistence. Students who articulate specific and meaningful goals are more likely to engage strategically and evaluate their performance against personal benchmarks. At the beginning of a simulation cycle or research task, instructors should facilitate the formulation of SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). This can be achieved via guided prompts, goal worksheets, or collaborative planning sessions. At this point in the learning session, leaderboards, points systems, level achievement can be used (e.g., to reach level 2, the student must answer 2 questions correctly, to reach the 3rd level – three questions, etc.) and at the end of the semester/academic year, the students will be rewarded with badges, diplomas, etc.

In the microbiology laboratory, every session starts with a quiz, flash cards or questions from the previous laboratory, to ensure the activation of prior knowledge and anticipation of goals: pre-reflection. Every laboratory ends with review questions meant to be discussed at the beginning of the next session or as Kahoot questions in the new presentation.

- 2.

Reflexive activation

Theoretical rationale reflection supports deeper learning by allowing students to analyze their actions, evaluate outcomes, and derive generalizable insights. As Gotoh (2016) shows, metacognitive regulation—including structured reflection using rubrics—enhances critical thinking and problem-solving. Educational implementation reflection should be embedded cyclically: before (predictive reflection), during (self-monitoring), and after (retrospective analysis) the learning activity. Tools such as reflection journals, guided reflection questions, and video debriefings are effective.

In the microbiology laboratory, we use PowerPoint Presentations with information about descriptive features, virulence factors, the most important pathogenic species of studied bacterial genus, morphological characteristics, selective media and biochemical tests and their interpretation.

- 3.

Consolidation

Theoretical rationale cognitive strategies such as summarizing, elaboration, visualization, and analogy enable learners to process information more deeply. These strategies are critical in simulation learning, where knowledge must be integrated across domains and modalities (Gul & Shehzad, 2012).

Educational implementation instructors should teach and model the use of cognitive strategies explicitly, encouraging students to apply them during simulation planning, execution, and interpretation. Metacognitive prompts (e.g., “What strategy are you using now?”) can support real-time application. In order to develop the strategy- and time-awareness as metacognitive skills (Abdelshiheed, Hostetter, Yang, et al., 2023) in the context of future learning, this step teaches the students how and when to use backwards- and forwards-chaining strategies (Abdelshiheed, Hostetter, Barnes, et al., 2023).

In a healthcare simulation scenario, students could use concept mapping to organize differential diagnoses, connect symptoms with underlying mechanisms, and visualize decision pathways. In the microbiology laboratory, the consolidation is made with guided exploration through the application of procedures, critical observation, and the correlation of theory with practice. Some tests are to be done following procedures, using the forward-chaining strategies, while others are already done, the students can read the result and with the use of backward-chaining strategies go back to the beginning of the test and find the bacterial characteristic that is relevant for the case. The students can identify the morphological, cultural and biochemical characteristics of the bacterial species. The observations and their interpretations are to be noted in the laboratory report and discussed. Combining the chaining strategies gives diversity and interactivity to this step, the students can switch between tasks, and this change keeps them focused.

- 4.

Reflection

Theoretical rationale regulation refers to learners’ ability to adaptively monitor and control their learning process. It includes time management, strategy adjustment, help-seeking, and emotion regulation—skills essential in open-ended, ill-defined simulation tasks (Zimmerman, 2002). Teaching regulation involves helping students identify when and how to modify strategies, manage cognitive load, and persevere through challenges. Instructors can facilitate peer coaching, metacognitive checkpoints, and real-time feedback loops.

In the microbiology laboratory, for the idenfication of knowledge gaps or misunderstandings and clarification of key concepts the students will discuss a case study. For solving the ‘mistery’, the students are asked to think alout while solving the case and analysing the resulting verbal protocols.

- 5.

Awareness/Autoregulation

Theoretical rationale awareness encompasses moment-to-moment consciousness of one’s thinking, focus, and emotional state. It acts as a metacognitive alert system, enabling timely interventions and reflective shifts. Gul and Shehzad (2012) found that awareness was moderately linked to academic achievement and goal orientation.

Educational implementation awareness can be fostered through mindfulness exercises, pause-reflect strategies, and visual cues. Simulation dashboards that display progress indicators or real-time data also support awareness.

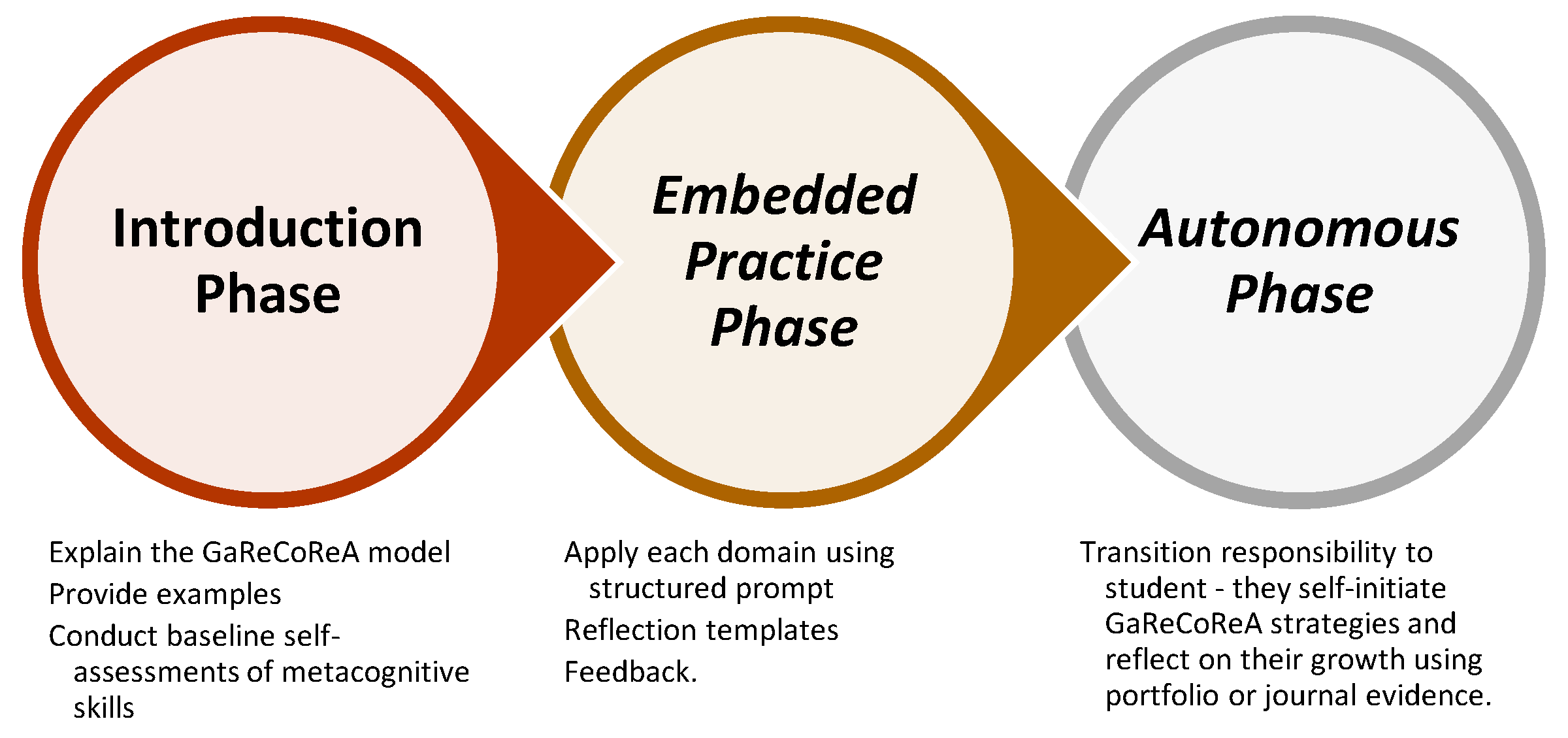

To implement GaReCoReA holistically, we recommend a three-phase integration across the course or training programme, structured like in

Figure 3. This progression supports the internalisation of metacognitive practices and aligns with developmental learning models in higher education.

The metacognitive model used for microbiology laboratories, with its steps, pedagogical tools and expected outcomes are summarized in

Table 1.

Results of the Garecorea Implementation in the Special Bacteriology Laboratory

To assess the perceived impact of the model, students (n = 72) completed an anonymous questionnaire at the end of the semester. The majority described their learning experience as positive, with 88% reporting either “very good” or “excellent.” Although only one subset found gamified tools such as flashcards and badges highly useful, 29 students reported increased engagement during sessions that included case studies and interactive tasks. Notably, 19 students stated that the course helped them become more aware of their strengths and areas for improvement, indicating the model’s value in promoting self-reflection and diagnostic reasoning. These findings support the practical relevance of GaReCoReA in simulation-based laboratory education, while also highlighting areas for further development such as scaffolding gamification elements more consistently across sessions.

In the final open-ended question, students were invited to reflect on whether the GaReCoReA model should be used in other subjects. Thematic analysis of their responses indicated strong support for wider application:

“I think we can also use this model in virology, to be more familiar with different virus families. This model really helped me visualise every Bacteria.”

“Yeah! Because it’s more attractive and allows us to participate in a different way. We learn better like this and can retain more information.”

Final exam results showed strong retention of content covered during lab sessions, though a more detailed quantitative analysis is ongoing and available upon request.

Transdisciplinary Reflections: From Smart Manufacturing to Smart Learning

Simulation environments in both engineering and healthcare education offer learners highly interactive and authentic problem-solving contexts. However, without explicit metacognitive support, learners often approach simulations as trial-and-error tasks rather than structured opportunities for learning and transfer. Simulation software not only supports system modelling in manufacturing but is also increasingly used in academic settings to train decision-making, problem-solving, and metacognitive reflection (Ciauşu-Sliwa et al., 2025). The GaReCoReA model addresses this gap by embedding metacognitive scaffolding directly into simulation-based teaching strategies.

In plant simulation tools such as Tecnomatix or AnyLogic, learners are required to construct, run, and evaluate digital models of production systems. These tasks demand not only technical fluency but also cognitive flexibility and reflective thinking. For example, learners must define simulation objectives (Goal setting), interpret performance outputs (Reflection), decide on parameter adjustments (Regulation), and identify effective modelling heuristics (Cognitive strategies). By integrating GaReCoReA, instructors can enhance students’ simulation learning experience through structured prompts such as:

- ➢

Before the simulation: “What do you expect to learn?” (Goal-setting)

- ➢

During the simulation: “What strategy are you applying and why?” (Cognitive strategy + Regulation)

- ➢

After the simulation: “What worked, what didn’t, and what will you change next time?” (Reflection + Awareness)

This metacognitive overlay transforms the simulation from a mechanical task to a strategic learning event, fostering deeper conceptual understanding and transferability of skills.

Healthcare simulation relies heavily on clinical reasoning, team coordination, and high-stakes decision-making. Gotoh (2016) emphasises that metacognitive regulation—especially when paired with rubrics and performance reflection—enhances critical thinking. In our collaborative teaching experiences, embedding GaReCoReA into medical and veterinary simulation has enabled students to become more reflective about diagnostic reasoning and procedural accuracy.

For example, reflective debriefings aligned with the GaReCoReA domains help students articulate their thought processes and justify their decisions—skills crucial for clinical competence. Moreover, awareness prompts increase students’ real-time recognition of stress, uncertainty, and cognitive overload, allowing more adaptive behaviour during simulations.

Doctoral students engaging in simulation research (e.g., digital twin systems or socio-technical modelling) could benefit from the GaReCoReA model as a framework for scientific self-regulation. We expect doctoral candidates who follow GaReCoReA principles to demonstrate greater autonomy in managing project cycles, troubleshooting complex code, and reflecting on methodological limitations.

In veterinary but also in engineering context, the GaReCoReA model could provide a clear scaffold for promoting self-regulation and reflective learning, positive feedback from four consistent themes is expected:

- ➢

An increase of the engagement through gamified introductions.

- ➢

Improved strategic thinking through concept mapping and mid-task prompts.

- ➢

Stronger awareness of limitations in the post-activity reflection phase.

- ➢

To detect the transfer planning (autoregulation) as the most challenging but transformative phase.

The structured nature of the model empowered learners to anticipate challenges, monitor their progress, and reflect with clarity—reinforcing the metacognitive loops described by Gul and Shehzad (2012).

Recent international reports, such as UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report (2023) and the OECD Learning Compass 2030, emphasize the growing need for metacognitive training to enhance adaptability and lifelong learning skills among students (GEM Report UNESCO, 2023; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4, n.d.). The GaReCoReA model directly responds to this need by offering structured guidance for learners navigating increasingly complex and digital learning environments. As universities progressively incorporate AI-supported tools, simulations, and learning dashboards into their curricula, metacognitive frameworks like GaReCoReA become particularly valuable. They ensure students do not merely interact passively with technology but actively reflect, adapt, and regulate their learning processes. Integrating future enhancements, such as learning analytics that monitor real-time student strategies or adaptive AI tools for personalized reflection prompts, could significantly boost individualized support and instructional effectiveness. Thus, GaReCoReA is not just addressing theoretical or disciplinary challenges—it also provides practical guidance for fostering resilient and self-aware learners in the digital era.

Conclusions and Future Research

The GaReCoReA model addresses a critical gap in simulation-based education by offering a structured yet adaptable framework for cultivating metacognitive competence in learners. Drawing upon foundational theories of metacognition and self-regulated learning, the model synthesises five interdependent components—Goal-setting and Gamification, Reflexive Activation, Consolidation, Regulation, and Awareness/Autoregulation—into an iterative pedagogical cycle. These domains are grounded in empirical evidence and designed to be implemented across disciplines, particularly in environments characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and technological mediation.

Our research and teaching experiences in veterinary microbiology, engineering simulation, and doctoral training have shown that students often lack the metacognitive scaffolds required to navigate such environments effectively. By embedding reflective questions, goal-setting frameworks, gamified learning tasks, and cognitive strategies into simulation-based curricula, GaReCoReA helps learners engage more deeply with content, monitor their progress, and critically reflect on their performance.

The model’s integration into real-world learning contexts—such as identifying bacterial species in lab settings or modelling production systems using plant simulation software—has demonstrated its value in enhancing learner autonomy, adaptability, and performance. Additionally, it aligns well with contemporary educational paradigms that emphasize constructivist learning, active participation, and the development of transferable skills.

The students’ positive responses support the pedagogical validity of GaReCoReA. Especially noteworthy was the perceived usefulness of gamified elements and backward/forward chaining, which suggests that cognitive scaffolds can significantly enhance diagnostic reasoning and procedural autonomy in laboratory settings.

Furthermore, the model’s metacognitive components—particularly awareness and strategic reflection—appear to have supported students in recognizing their learning gaps and adapting their strategies accordingly, consistent with Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning model.

Looking forward, the GaReCoReA model offers promising avenues for future research and practice. It can be adapted to diverse educational settings, scaled for various levels of learner expertise, and aligned with digital platforms for personalized learning analytics. Moreover, its principles may inform the development of instructional design tools, doctoral supervision strategies, and cross-disciplinary training programs.

Future iterations of GaReCoReA may benefit from exploring AI-supported strategies for reflection and self-explanation, particularly in resource-limited or remote teaching environments. As part of the broader context of metacognitive learning, artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being explored as a supportive tool in education. While our focus in this study was on active strategies such as gamification and structured reflection, it is worth acknowledging that AI can also contribute to the development of metacognitive skills. For instance, conversational agents like ChatGPT have been used in medical education to support clinical reasoning, promote self-explanation, and offer iterative feedback on student-generated hypotheses. In a recent study, students reported that AI-assisted dialogue helped them identify knowledge gaps, organize their thoughts more clearly, and reflect on diagnostic strategies—skills closely aligned with metacognitive growth (Kung et al., 2023). When used purposefully, such tools can complement models like GaReCoReA by offering real-time prompts for reflection, visualizing learning trajectories, or encouraging deeper engagement through questioning. Rather than replacing personal guidance, these systems can enhance self-awareness and decision-making in students who are learning to think more critically and independently. In this way, the integration of AI into teaching practice holds promise as a natural extension of metacognitive pedagogies—particularly in environments where personalized support can amplify learning.

Although GaReCoReA is not limited to simulation-based teaching, its structure lends itself well to complex, open-ended learning environments—such as laboratory tasks, clinical reasoning, or system modelling. These parallels offer a promising direction for future interdisciplinary applications.

In conclusion, the GaReCoReA model represents more than a pedagogical tool—it is a strategic response to the evolving demands of higher education. Its structured approach to metacognition equips learners with enduring skills for academic success, professional development, and scientific inquiry. Future research should explore its integration with AI-driven feedback systems, real-time learning analytics, and cross-institutional applications in both STEM and health sciences.

References

- Abdelshiheed, M. , Hostetter, J. W., Barnes, T., & Chi, M. (2023). Bridging Declarative, Procedural, and Conditional Metacognitive Knowledge Gap Using Deep Reinforcement Learning, arXiv:2304.11739). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Abdelshiheed, M. , Hostetter, J. W., Yang, X., Barnes, T., & Chi, M. (2023). Mixing Backward- with Forward-Chaining for Metacognitive Skill Acquisition and Transfer, arXiv:2303.12223). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Akturk, A. O., & Sahin, I. (2011). Literature Review on Metacognition and its Measurement. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3731–3736. [CrossRef]

- Alomari, I., Al-Samarraie, H., & Yousef, R. (2019). The Role of Gamification Techniques in Promoting Student Learning: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 18, 395–417. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. [CrossRef]

- Ciauşu-Sliwa, M., Ciaușu-Sliwa, D., & Dodun, O. (2025). Discrete-Event Simulation for Smart Manufacturing: Assessing Software, Industry Adoption, and Future Research Challenges. Bulletin of the Polytechnic Institute of Iași. Machine Constructions Section, 71, 105–124. [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining Gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, MindTrek 2011 (Vol. 11, p. 15). [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning, 3(3), 231–264. [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. (2008). Metacognition. European Psychologist, 13(4), 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S. M., & Frith, C. D. (Eds.). (2014). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Free, N., Menendez, H. M., & Tedeschi, L. O. (2022). A paradigm shift for academia teaching in the era of virtual technology: The case study of developing an edugame in animal science. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 625–642. [CrossRef]

- GEM Report UNESCO. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? (1st ed.). GEM Report UNESCO. [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, Y. (2016). Development of Critical Thinking with Metacognitive Regulation. In International Association for Development of the Information Society. International Association for the Development of the Information Society. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED571408.

- Greene, J. A. , Robertson, J., & Costa, L.-J. C. (2013). Assessing Self-Regulated Learning Using Think-Aloud Methods. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Gul, F., & Shehzad, S. (2012). Relationship Between Metacognition, Goal Orientation and Academic Achievement. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1864–1868. [CrossRef]

- Ifenthaler, D. , Eseryel, D., Ge, X., Ke, F., Warren, S., Loh, C., & Clark, D. (2012). Assessment in game-based learning Part 1 & 2—Panels.

- Kung, T. H., Cheatham, M., Medenilla, A., Sillos, C., De Leon, L., Elepaño, C., Madriaga, M., Aggabao, R., Diaz-Candido, G., Maningo, J., & Tseng, V. (2023). Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digital Health, 2(2), e0000198. [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G., Osborne, M., Evans, P., & Miksza, P. (2017). Applying self-regulated learning microanalysis to study musicians’ practice. Psychology of Music, in press. [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M. (2014). Equine Virtual Farm: Toward Meaningful Cognitive Strategies in Veterinary Education.

-

OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. (n.d.). OECD. Retrieved 3 February 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-guidelines-for-the-testing-of-chemicals-section-4_20745788.html.

- Pratt, C., & Steward, L. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis: The Role of Task Analysis and Chaining. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/applied-behavior-analysis.html.

- Rahnev, D. (2025). A comprehensive assessment of current methods for measuring metacognition. Nature Communications, 16(1), 701. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, A., Felleson, A., Turner, P. C., & Green, M. (2022). Assessing the impact of metacognitive postreflection exercises on problem-solving skillfulness. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 18(1), 010109. [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, M., Dumitriu, C., Clipa, O., Ignat, A. A., Mâţă, L., & Brezuleanu, C.-O. (2011). Experimental Research on Metacognitive Competence Development at Freshmen Students from Three Romanian Universities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1914–1923. [CrossRef]

- Vrugt, A. Vrugt, A., & Oort, F. J. (2008). Metacognition, achievement goals, study strategies and academic achievement: Pathways to achievement. Metacognition and Learning, 3(2), 123–14. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. L., & Vengrin, C. A. (2021). Comparison of Graphic Organizers Versus Online Flash Cards as Study Aids in an Elective Veterinary Cardiology Course. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 48(4), 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).