Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Metacognition

1.2. Implementation in School Contexts

1.3. Metacognition and Mathematical Problem Solving

1.4. Teacher Professional Development

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Current Study

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Data Collection and Sample

2.4. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Building Knowledge, Confidence and Capacity

“sometimes you might try things in your own classroom and you never really know how it’s working […] It’s been really lovely trying something new and talking about the theory behind it to start with because then it gives you a reason why you want to do it as well” (Teacher C, final interview).

“I hadn’t even really thought about the fact that we never really teach problem solving. We expect children to be able to do it, but we never actually explicitly teach it. And then I thought especially those pupil premium children, their metacognition isn’t as developed as others and it really got us thinking that it’s definitely something we need to do” (Teacher T, final interview).

“I knew the word metacognition and I didn’t know a lot about it before I came on the course. So for me, it was useful in terms of enabling me to know how to teach the children to plan and when to work through a problem and to be able to do that with a little bit of support and then independently” (Teacher T, final interview).

“Stepping Stones has enabled me to understand how to explicitly teach problem solving. The course has helped me to understand different approaches to teaching problem solving through worked examples, faded worked examples and mistakes” (post-programme survey, Q7a)

“it’s nice that the programme repeats itself, so we start with the highlighting and then we move on to unpicking the question. I think having that repeated process constantly has been really good for supporting my disadvantaged children who don’t remember as much” (Teacher S, final interview).

“the first couple of weeks, I used [the scripts] like gospel and reading them when I was getting the kids to talk. But then I’ll be honest, the last two weeks I haven’t even really looked at them. I’ve looked at them at the start and said alright, it’s a complete problem or a faded problem or a mistake, just so that I know what’s coming next” (Teacher C, final interview).

“The PowerPoints were brilliant. I didn’t use the teacher script and I did for the first week but I kind of went through the slides obviously before I taught it and I just thought about if I was teaching this what would be my questions because I think my questions would be sometimes different from what was in the teacher’s script and really because the way that the slides are set out and there were lots of opportunities for further discussion. So, me and the children ended up going off on a tangent so I didn’t want to be held to a script, I wanted to teach it the way I want to teach it” (Teacher S, final interview).

“I think the more we’ve got in the way of it and I’m able to speak from me, the more I know what I’m asking. We don’t need the scripts as much because, well, we’ve done it for 10 weeks” (Teacher T, final interview).

“So they know that we’re gonna get through these steps. We’re gonna learn how to do it, and then we’re gonna have a go. So I think that was really useful for them as well and gave the other ones a great model of how to solve the problem. So even if there weren’t 100% sure they could look go right, well, we’ll do this one. But they were looking back at the steps on the river to have a go at their problem” (Teacher L, final interview).

“I feel I am much more confident in using items such as, Think Alouds and worked examples in my practice and I have started using them across my teaching” (post-survey, 8a).

“I definitely hear myself thinking, but why? ‘Tell me you know that because…’ and those types of stem sentences definitely carry through” (Teacher K, final interview).

“it made me think a little bit more about small steps. So I think sometimes I think about doing a worked example, but I don’t think about all the small steps where that’s what the problem solving really did because there was 5-6 steps to it. Sometimes it was going in a lot smaller steps than I would probably think of myself, which is really good because then it affected my practice in a good way. So I kind of use a lot of the strategies that we’ve done in Stepping Stones to help me in my work as well, which is really good.” (Teacher C, final interview).

3.2. Increased ownership and ‘buy in’

“I think it’s really nice to have that ownership of the system to it as well. And then coming back into school and obviously I work with another year group partner, so then me telling them and saying, oh, well, we’ve one this because of this reason and this is how it’s going to work” (Teacher C, final interview).

“I think that was really beneficial with the teaching of it and the implementation of it, like understanding where it’s all come from and doing it yourself. Especially writing the script because it gave… It allowed us to realise what we do need in the script and what we can skip out” (Teacher L, final interview).

“I think probably since the people on the course started developing them, they’ve become a bit easier and I don’t know if that’s just because it’s done by the year 2 teachers kind of with their kids in mind.” (Teacher C, final interview).

“I am going to continue this in summer term and plan and prepare my own slides. I am planning on using the programme with next year’s year 2 cohort too” (post-programme survey, Q25a)

“I’ve had an ECT and another staff member observe from our school and the ECT was from year four and she thinks that she would like to roll it out in year four as a quick 10 minutes. Let’s identify the key facts and things. So I’m in discussions with our SLT at the minute to see whether or not we might be able to do it across the school like say three times a week” (Teacher S, final interview)

“I think having a conversation with [Maths Lead] because she’s been really, really excited by it and she’s been thinking about how she can do things like it with Year 6. She’s been having a go’ (Teacher C, final interview)

3.3. The Value of Collaboration

“The collaboration was so useful because I felt sometimes like I wasn’t as valuable as the other teachers, but only because it was… It was really nice to hear experienced teachers feedback on the way they do maths or the way they do something else and it was nice to even make our own and sit with somebody else and say like, ‘I would have done it this way with my class’. But they’ve done it a completely different way and it was really nice to hear that different ways of doing things in maths. I thought that was so useful. When I came back to my headteacher I said, ‘Ohh, it was amazing’” (Teacher J, final interview).

“both of you were absolutely brilliant in your delivery and you kind of opened it up to the floor more than enough because sometimes on some courses that you go to you get talked to a lot. And although they ask for questions, they don’t really want me to answer, they want to answer themselves, whereas I think this was very much you really wanted to hear what we wanted to do and really wanted us to get involved” (Teacher C, final interview).

“I know we did talk about the planning stage where that might have been better just at school, but it wasn’t. It was lovely to be altogether and share our ideas, so I did think the group discussions and the group meetings were brilliant” (Teacher S, final interview).

“Really good opportunity to plan with K present for support” (Training session 3 feedback).

“The two sessions we had with K and W really helped break down the planning process” (post-survey, 8a).

“I think the frequency of seeing each other actually was enough to not need anything else. Because we’ve seen you probably once a month, I think I felt like that if we did have a problem then we knew how to reach you […] There’s a lot of work gone into it, you weren’t just handed it and said go and have a go because it was like the sessions where we caught up fell nicely within a week of us being able to give it a go, get back, feedback. Then the sessions we planned together. They weren’t immediately the week after. So, then that fed into those weeks and then we came back together again” (Teacher K, final interview).

“you and W were both there supporting and any questions we had you were there to help and support. I think it was just the time, just the amount of time for it, you know. You gave us materials, like all of the things that you use like the puzzles and the problems. […] I don’t think we could have had any more support really. I think it was just the time” (Teacher T, final interview)

“me and my partner didn’t get the second slides done. So we only got the one session done. So I do think a little bit more time to plan both of them in that session would have been useful for me to break it down and think about it myself” (Teacher J, final interview)

“I think time one is a tricky one because you could have given us longer and some people could have absolutely flown through it. Or you could have gave us less time and some people still would have done it. I think it depends on more the computing skills than the mathematical skills and process, and I think probably the people that got through the problems quicker were the ones that were more confident using the software, they make animations and things like that rather than the actual maths behind it. I think the only issue that I had was the Wi-Fi […] because that was making the collaborative document really slow and cumbersome” (Teacher C, final interview)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lai, E.R. Critical Thinking: A Literature Review; 2011.

- Perry, J.; Lundie, D.; Golder, G. Metacognition in schools: what does the literature suggest about the effectiveness of teaching metacognition in schools? Educational Review 2019, 71, 483-500. [CrossRef]

- (EEF), E.E.F. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Guidance Report; 2021.

- Vula, E.; Avdyli, R.; Berisha, V.; Saqipi, B.; Elezi, S. The impact of metacognitive strategies and self-regulating processes of solving math word problems. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 2017, 10, 49-59. [CrossRef]

- Muncer, G.; Higham, P.A.; Gosling, C.J.; Cortese, S.; Wood-Downie, H.; Hadwin, J.A. A meta-analysis investigating the association between metacognition and math performance in adolescence. Educational Psychology Review 2022, 34, 301-334. [CrossRef]

- Muijs, D.; Bokhove, C. Metacognition and self- regulation: Evidence Review; 2020.

- Jossberger, H.; Brand-Gruwel, S.; Boshuizen, H.; Wiel, M. The challenge of self-directed and self-regulated learning in vocational education: A theoretical analysis and synthesis of requirements. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 2010, 62. [CrossRef]

- Veenman, M.; Van Hout-Wolters, B.; Afflerbach, P. Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacognition and Learning 2006, 1, 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J.H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist 1979, 34, 906-911. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., L. The School as a Home for the Mind: A Collection of Articles; Corwin: IL, 1991.

- Perry, V.; Albeg, L.; Tung, C. Meta-Analysis of Single-Case Design Research on Self-Regulatory Interventions for Academic Performance. Journal of Behavioral Education 2012, 21, 217-229.

- Wall, K. Understanding metacognition through the use of pupil views templates: Pupil views of Learning to Learn. Thinking Skills and Creativity 2008, 3, 23-33. [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G. Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning 2008, 3, 231-264. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.E. What is Metacognition? Phi Delta Kappan 2006, 87, 696-699. [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D.; Coltman, P.; Jameson, H.; Lander, R. Play, cognition and self-regulation: What exactly are children learning when they learn through play? Educational and Child Psychology 2009, 26, 40-52. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Metacognitive Development. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2000, 9, 178-181. [CrossRef]

- Veenman, M.V.J.; Wilhelm, P.; Beishuizen, J.J. The relation between intellectual and metacognitive skills from a developmental perspective. Learning and Instruction 2004, 14, 89-109. [CrossRef]

- Kistner, S.; Rakoczy, K.; Otto, B.; Dignath-van Ewijk, C.; Büttner, G.; Klieme, E. Promotion of self-regulated learning in classrooms: Investigating frequency, quality, and consequences for student performance. Metacognition and Learning 2010, 5, 157-171. [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.D.; Hancock, T.E. Reading Comprehension Improvement with Individualized Cognitive Profiles and Metacognition. Literacy Research and Instruction 2008, 47, 124 - 139.

- Schraw, G. Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science 1998, 26, 113-125. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.L.; Chase, C.; Chin, D.B.; Oppezzo, M.; Kwong, H.; Okita, S.; Biswas, G.; Roscoe, R.; Jeong, H.; Wagster, J. Interactive metacognition: Monitoring and regulating a teachable agent. In Handbook of metacognition in education.; The educational psychology series.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, US, 2009; pp. 340-358.

- Hodgen, J.; Foster, C.; Marks, R.; Brown, M. Evidence for review of mathematics teaching: improving mathematics in key stages two and three: evidence review; 2018.

- Kyriacou, C.a.I., J. What characterises effective teacher-initiated teacher-pupil dialogue to promote conceptual understanding in mathematics lessons in England in Key Stages 2 and 3: a systematic review; EPPI-Centre: 2008.

- Donovan, M.S., & Bransford, John, D. How students learn—Science in the classroom; National Academy Press.: Washington DC, 2005.

- Cross, D.R.; Paris, S.G. Developmental and instructional analyses of children’s metacognition and reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology 1988, 80, 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, M.G. Probing the Dimensions of Metacognition: Implications for Conceptual Change Teaching-Learning. 1999.

- Stein, M.K.; A., E.R.; S., S.M.; and Hughes, E.K. Orchestrating Productive Mathematical Discussions: Five Practices for Helping Teachers Move Beyond Show and Tell. Mathematical Thinking and Learning 2008, 10, 313-340. [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, K. Using Pupil Views to Uncover Evidence of Children’s Metacognition in Mathematics. International Journal of Student Voice 2021, 8.

- Picker, S.H.; Berry, J.S. Investigating pupils’ images of mathematicians. Educational Studies in Mathematics 2000, 43, 65-94. [CrossRef]

- Boaler, J. How a Detracked Mathematics Approach Promoted Respect, Responsibility, and High Achievement. Theory Into Practice 2006, 45, 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, A. An investigation of relationships between seventh-grade students’ beliefs and their participation during mathematics discussions in two classrooms. Mathematical Thinking and Learning 2008, 10, 68-100. [CrossRef]

- Westwood, P. The problem with problems: Potential difficulties in implementing problem-based learning as the core method in primary school mathematics. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties 2011, 16, 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Taverner, S.; Flitney, G. Thinking Through Mathematics; Chris Kington: 2008.

- Boylan, M., Adams, Gill., and Birkhead, Amy. Landscaping Mathematics Education Policy: Landscaping national mathematics education policy; 2023.

- Boylan, M., Zhu, Hongjuan., Jaques, Laurie., Birkhead, Amy., and Rempe-Gillen, Emma. Secondary Maths; Education Endowment Foundation (EEF): 2024.

- Woodward, J., Beckmann, S., Driscoll, M., Franke, M., Herzig, P., Jitendra, A., Koedinger, K. R., & Ogbuehi, P. Improving mathematical problem solving in grades 4 through 8: A practice guide; U.S. Department of Education: Washington DC, 2012.

- Izzati, L.; Mahmudi, A. The influence of metacognition in mathematical problem solving. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2018, 1097, 012107. [CrossRef]

- Foster, C. The fundamental problem with teaching problem solving. Mathematics Teaching 2019, 265, 8-10.

- Ofsted. Research review series: mathematics; Ofsted: 2021.

- Ofsted. Coordinating mathematical success: the mathematics subject report; Ofsted: 2023.

- Education, D.f. Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2023: National report for England.

- Volume 1. 2024.

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, Harry., O’Mara-Eves, Alison., Cottingham Sarah., Stansfield, Claire., Van Herwegen, Jo., & Anders., Jake. What are the Characteristics of Effective Teacher Professional Development? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis; Education Endowment Foundation (EEF): 2021.

- Cordingley, P.; Higgins, S.; Greany, T.; Buckler, N.; Coles-Jordan, D.; Crisp, B.; Saunders, L.; Coe, R. Developing Great Teaching; Teacher Development Trust: 2015.

- Sancar, R.; Atal, D.; Deryakulu, D. A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education 2021, 101, 103305. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S., Major, L. E., & Coe, R. What makes great teaching. Professional Voice 2014, 11, 11-16.

- Trust, T.S. Improving the impact of teachers on pupil achievement in the UK – interim findings 2011.

- Opfer, V.D.; Pedder, D. Access to Continuous Professional Development by teachers in England. The Curriculum Journal 2010, 21, 453-471. [CrossRef]

- Education, D.f. National professional qualification (NPQ) courses. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/national-professional-qualification-npq-courses (accessed on.

- Boulay, A.-M.; Bare, J.; Benini, L.; Berger, M.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Manzardo, A.; Margni, M.; Motoshita, M.; Núñez, M.; Pastor, A.V.; et al. The WULCA consensus characterization model for water scarcity footprints: assessing impacts of water consumption based on available water remaining (AWARE). The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2018, 23, 368-378. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Wood, H., & Zuccollo, James. The effects of high-quality professional development on teachers and students; Education Policy Institute 2020.

- Asterhan, C.S.C.; and Lefstein, A. The search for evidence-based features of effective teacher professional development: a critical analysis of the literature. Professional Development in Education 2024, 50, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Cain, T. Teachers’ engagement with published research: addressing the knowledge problem. The Curriculum Journal 2015, 26, 488-509. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Penuel, W.R. Studying Teachers’ Sensemaking to Investigate Teachers’ Responses to Professional Development Focused on New Standards. Journal of Teacher Education 2015, 66, 136-149. [CrossRef]

- Miquel, E.; and Duran, D. Peer Learning Network: implementing and sustaining cooperative learning by teacher collaboration. Journal of Education for Teaching 2017, 43, 349-360. [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.; Evans, D.K.; Breeding, M.E.; Arancibia, V. Teacher Professional Development around the World: The Gap between Evidence and Practice. The World Bank Research Observer 2021, 37, 107-136. [CrossRef]

- SHULMAN, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher 1986, 15, 4-14. [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Reimers, E. Teacher professional development:an international review of the literature; International Institute for Educational Planning, 2003.

- Mulholland Shipley, K. “I think when I work with other people I can let go of all of my ideas and tell them out loud’ : the impact of a Thinking Skills approach upon pupils’ experiences of maths. Newcastle University, 2016.

- Paas, F.; Alexander, R.; and Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and Instructional Design: Recent Developments. Educational Psychologist 2003, 38, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Evaluation, C.f.E.S.a. Cognitive load theory: Research that teachers really need to understand; New South Wales, 2017.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research design : qualitative, quantitative & mixed methods approaches, Fifth edition, international student edition. ed.; Sage: Los Angeles ; London, 2018.

- Bhaskar, R. On the possibility of social scientific knowledge and the limits of naturalism. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 1978, 8, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research : A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers / C. Robson. 2002.

- Wilson, N.; Bai, H. The relationships and impact of teachers’ metacognitive knowledge and pedagogical understandings of metacognition. Metacognition and Learning 2010, 5, 269-288. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A.; Kruskal, W.H. Measures of association for cross classification. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1954, 49, 732-764. [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3 ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis : a practical guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, 2022; pp. xxxiv, 338 pages.

- Sweller, J.; Van Merrienboer, J.J.G.; Paas, F. Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later. Educational Psychology Review 2019, 31, 261-292. [CrossRef]

- (EEF), E.E.F. Cognitive Science Approaches in the Classsroom: Evidence Review; 2021.

- Allen, J.P.; Hafen, C.A.; Gregory, A.C.; Mikami, A.Y.; Pianta, R. Enhancing Secondary School Instruction and Student Achievement: Replication and Extension of the My Teaching Partner-Secondary Intervention. J Res Educ Eff 2015, 8, 475-489. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel : a guide to designing interventions; Silverback Publishing: Great Britain, 2014; p. 329 pages.

- Thompson, M.; Wiliam, D. Tight but loose: A conceptual framework for scaling up school reforms. 2008; pp. 1-44.

- Lendrum, A.; and Humphrey, N. The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education 2012, 38, 635-652. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, C.L. Defining, Conceptualizing, and Measuring Fidelity of Implementation and Its Relationship to Outcomes in K–12 Curriculum Intervention Research. Review of Educational Research 2008, 78, 33-84. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, T.; Parker, J.; Eberhardt, J.; Koehler, M.; Lundeberg, M. Virtual Professional Learning Communities: Teachers’ Perceptions of Virtual Versus Face-to-Face Professional Development. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2013, 22. [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Legleiter, E.; Owens, K.; Packard, B.; Wright, J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of an Online Professional Development for Rural Middle-School Science Teachers. Journal of Science Teacher Education 2023, 35, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.; and Booth, J. The practices of professional development facilitators. Professional Development in Education 2024, 50, 144-156. [CrossRef]

- Hadar, L.L.; and Brody, D.L. Interrogating the role of facilitators in promoting learning in teacher educators’ professional communities. Professional Development in Education 2021, 47, 599-612. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.L.; Ayres, P.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory for the Design of Medical Simulations. Simul Healthc 2015, 10, 295-307. [CrossRef]

- Renkl, A. Toward an Instructionally Oriented Theory of Example-Based Learning. Cognitive Science 2014, 38, 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P.A.; John, S.; and Clark, R.E. Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist 2006, 41, 75-86. [CrossRef]

- Farley-Ripple, E., N., Tilley, Katherine., Mead, Hilary., Van Horne, Sam., and Agboh, Darren. How is evidence use enacted in schools? A mixed methods multiple case study of “deep-use”schools; Centre for Research Use in Education: 2022.

- Paas, F.; Ayres, P. Cognitive load theory: A broader view on the role of memory in learning and education. Educational Psychology Review 2014, 26, 191-195. [CrossRef]

- van Merriënboer, J.J.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies. Med Educ 2010, 44, 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Creagh, S.; Greg, T.; Nicole, M.; Meghan, S.; and Hogan, A. Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: a systematic research synthesis. Educational Review 2023, 77, 661-680. [CrossRef]

| Data | Further information |

| Pre-, mid- and post-programme surveys | Teachers’ views and understanding of metacognition, problem solving, and wider learning in mathematics, as well as their feelings, confidence and opinions. |

| Training session feedback survey | Feedback regarding teachers’ perceptions of their learning and experiences following each of the three PD sessions. |

| Observations during school visit | Observation notes from visits to each school during the second or third weeks of delivery. Visits were made by one member of our research team to observe a Stepping Stones session, and a short (20-30 minutes) discussion regarding implementation. Observations were structured using a checklist of key programme features, as well as a series of questions to guide an informal discussion with teachers. |

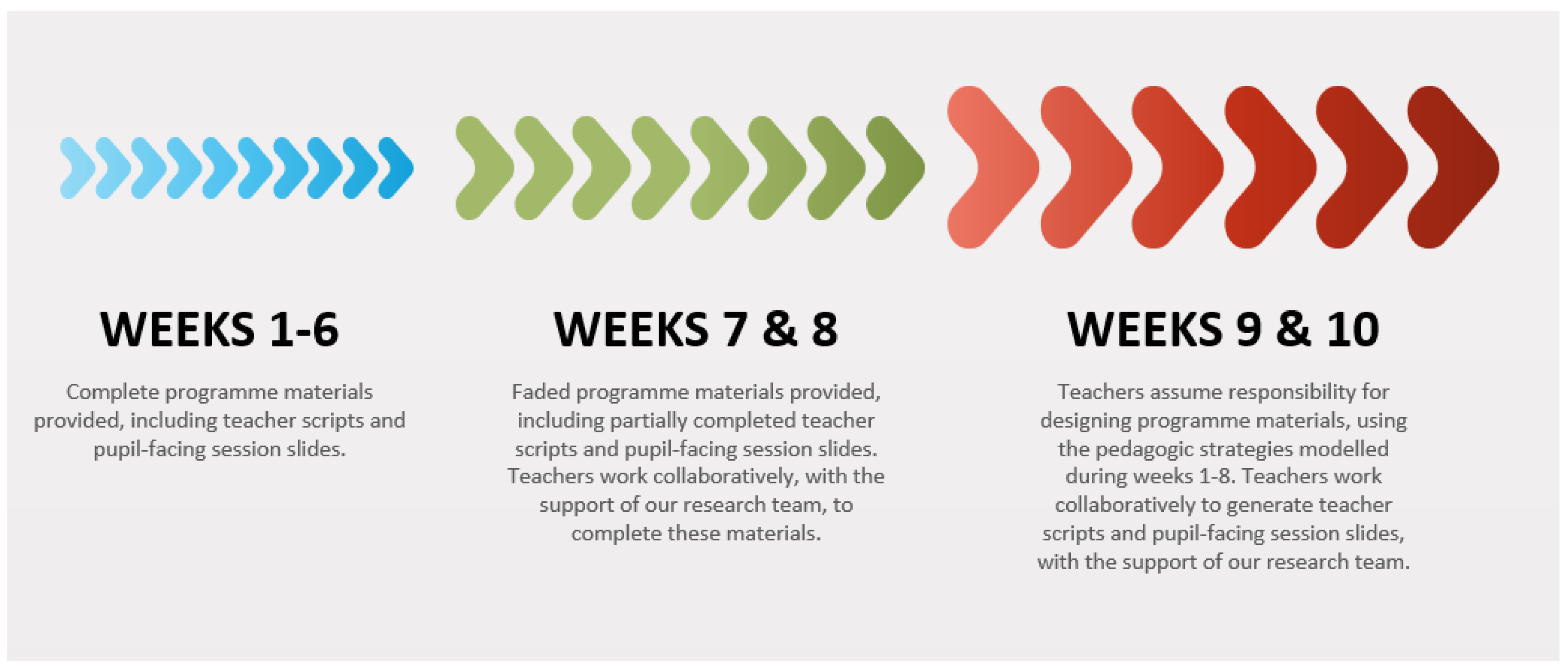

| Review of teacher-generated materials | Analysis of programme materials (pupil-facing session slides and teacher scripts) produced by teachers during the fading stages of the programme (weeks 7-10). Analysis was structured using a checklist of key programme features. |

| Interviews | Semi-structured interviews, conducted within two weeks following the conclusion of the programme. These were of approximately 30 minutes in duration, and took place via Microsoft Teams. The Microsoft Teams transcription function was used to generate a written record of these discussions. An audio recording was also taken and was used to cleanse transcripts to produce an accurate record of conversations. |

| Checklist Strategy | Total Count and Implementation % | Mean Rank |

| 15-20 mins session delivered, outside of the daily maths lesson | 15 (100%) | 8.50 |

| Programme slides used | 15 (100%) | 8.50 |

| Problem solving objective shared with the class | 14 (93%) | 6.50 |

| Mixed-attaining trios are in place for discussion | 14 (93%) | 6.50 |

| Expectations for discussion are clearly communicated to children | 13 (87%) | 4.50 |

| Strategies for problem solving – in addition to mathematical content alone – is a key focus of the session | 13 (87%) | 4.50 |

| Teacher overview used to inform questioning and discussion within the session | 11 (73%) | 3.00 |

| ‘River’ used | 9 (60%) | 2.00 |

| Alternating worked example used | 8 (53%) | 1.00 |

| Checklist Item |

Total Frequency Count (Weeks 7-9) |

Missing | Brief Information Included |

Detailed Information Included |

Γ | p |

| Learning intentions, including both National Curriculum and problem-solving objectives | 25 | 0 (0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | -.857 | .040* |

| Teacher overview, including script | 22 | 0 (0%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | -1.00 | 0.01** |

| Teacher overview includes use of Think Aloud | 21 | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | -.750 | 0.01** |

| Alternating worked example identified as an optional extension | 26 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (89.9%) | .000 | 1.00 |

| Teacher overview details key question prompts | 26 | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (89.9%) | -1.00 | .225 |

| Worked Example uses complete/mistakes/fading as appropriate | 26 | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (89.9%) | -1.00 | .225 |

| Visual representations are used to support understanding of key mathematical concepts | 26 | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (89.9%) | -1.00 | .225 |

| Worked example included in session slides includes reference to/exemplification of the problem solving objectives taught during the session | 26 | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (89.9%) | -1.00 | .225 |

| *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).