Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

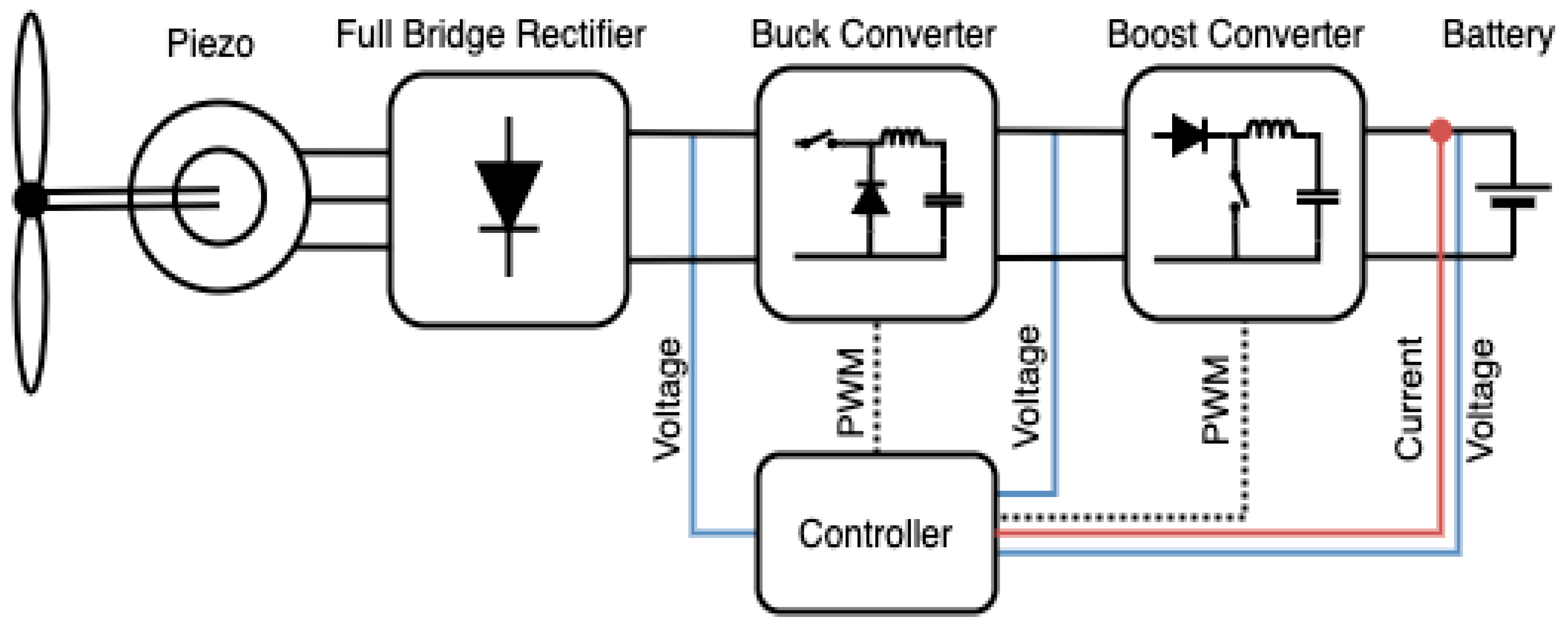

2. Harvester Design

2.1. Modeling of Harvester Design

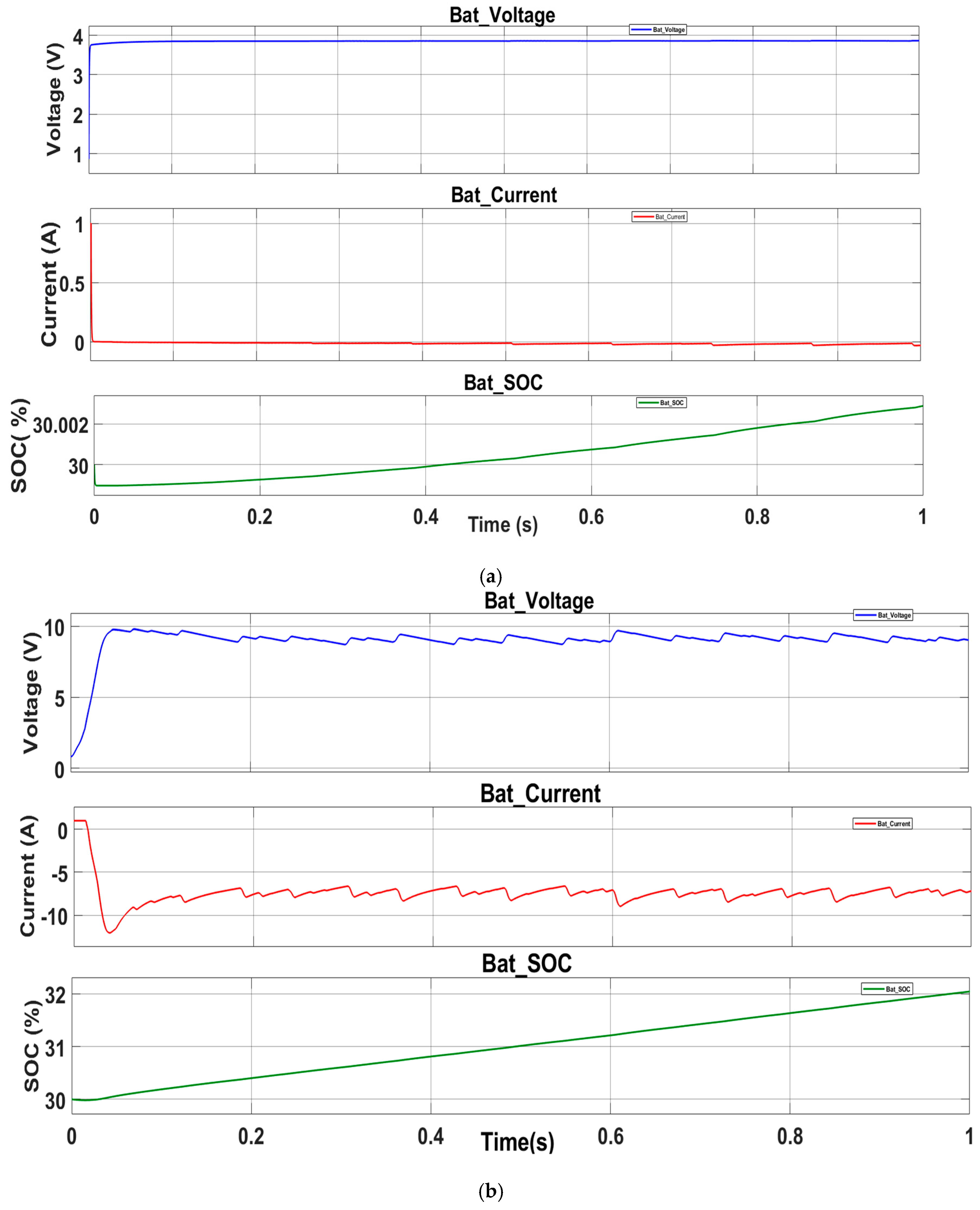

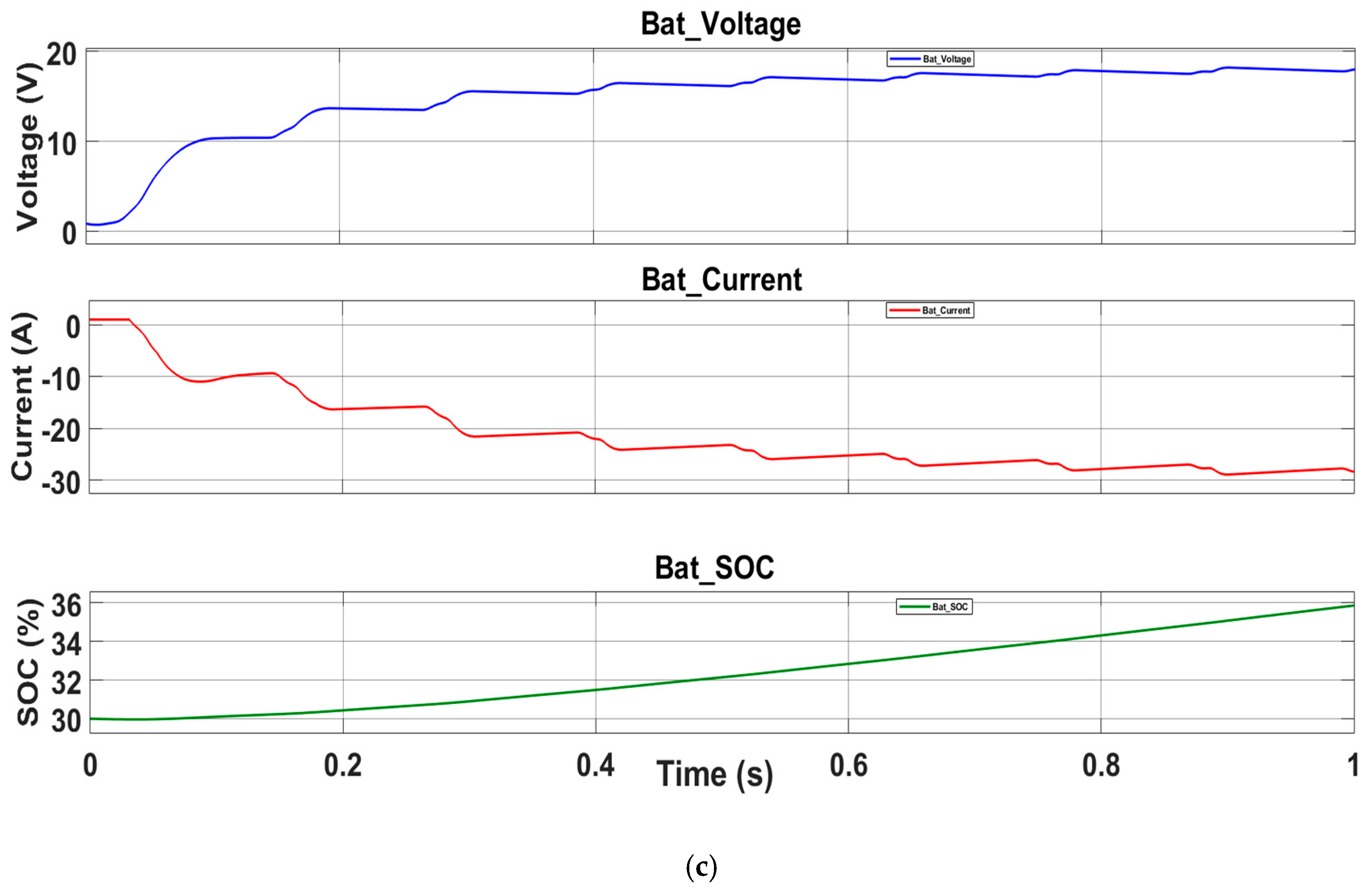

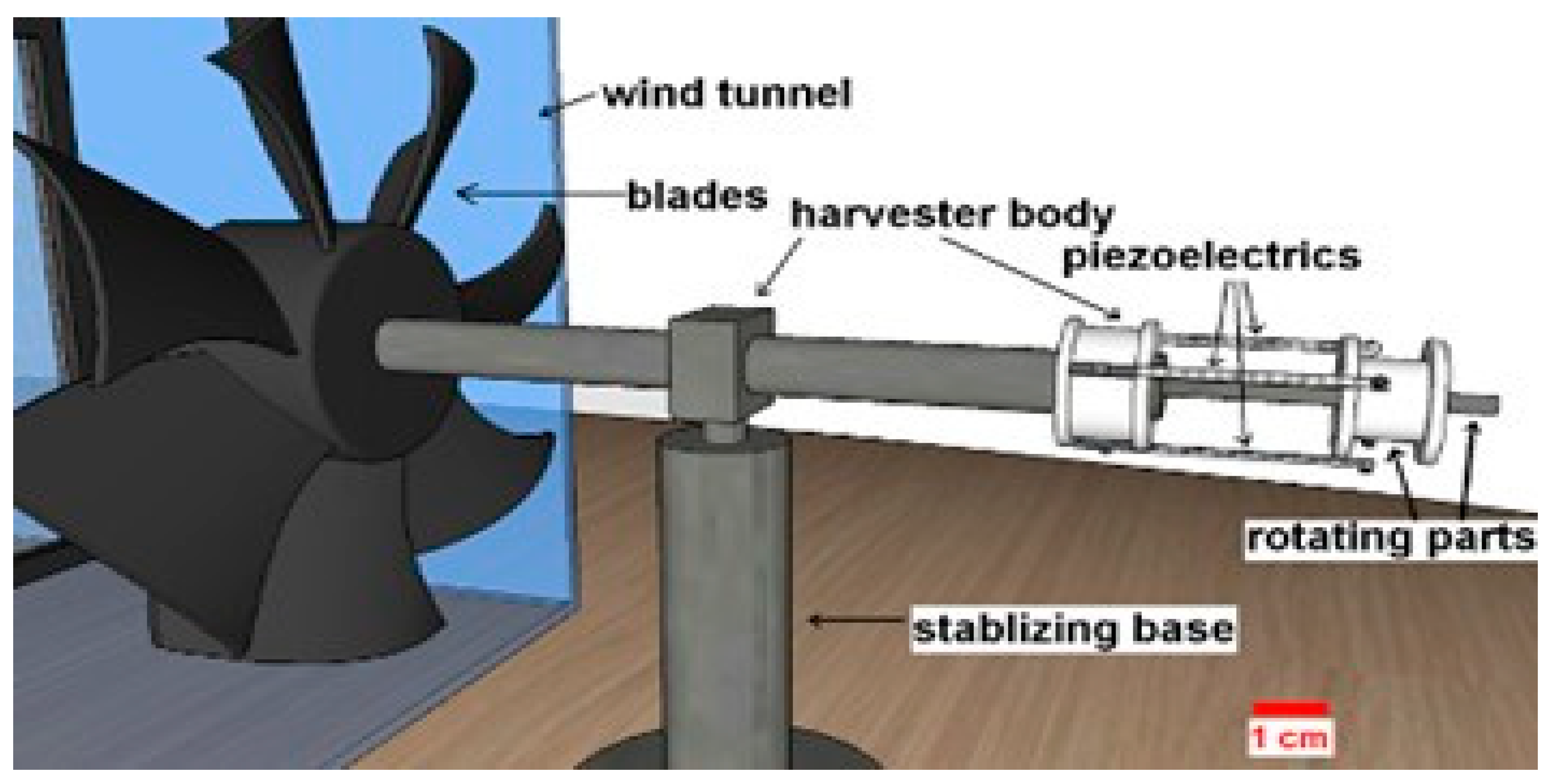

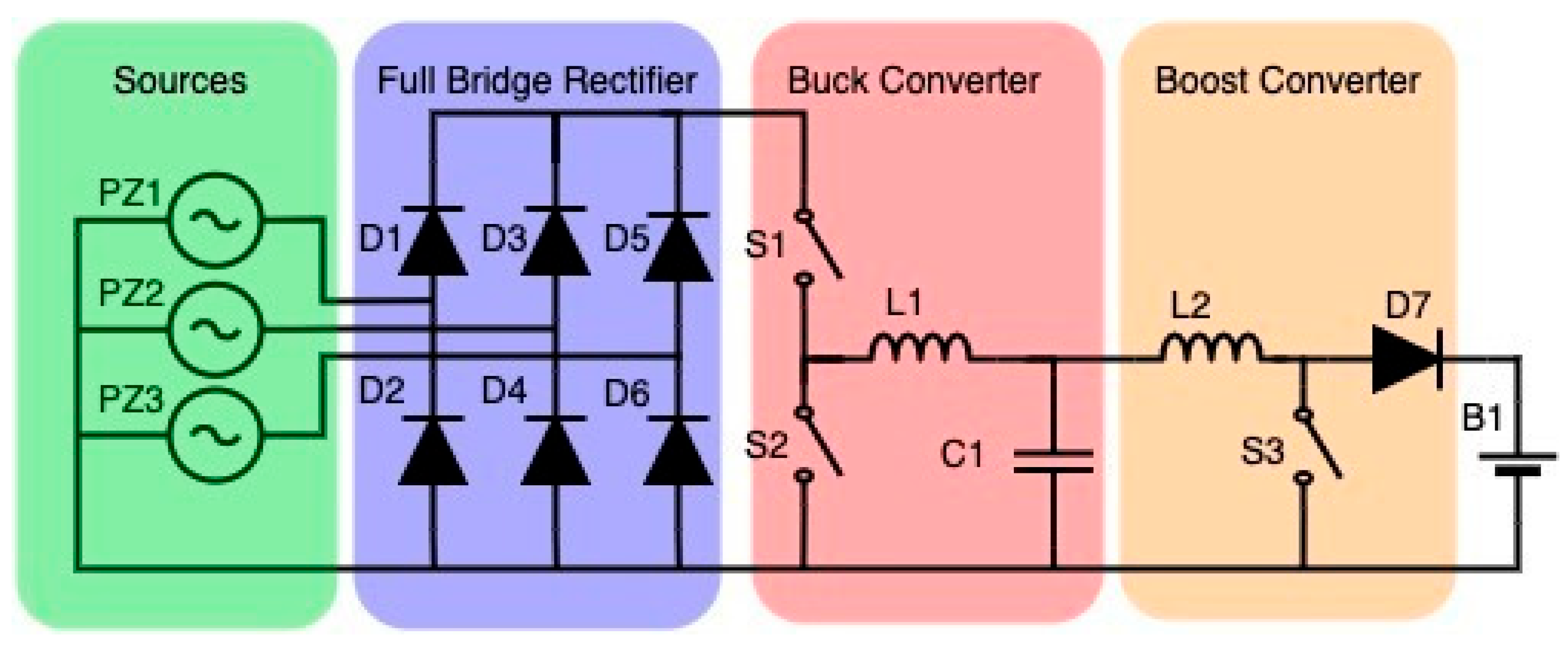

2.2. Topology of Circuit

| Buck Converter | Boost Converter | |

|---|---|---|

| Inductance (L) | 1 mH | 1 mH |

| Capacitance (C) | 1 mF | 1 mF |

| Switching Frequency (f) | 10 kHz | 10 kHz |

| PI Control (P-I) | 200-300 | 200-300 |

| Sample Time (Tss) | 1x10-6 s | |

| Battery | Li-ion, 0.1Ah, 3.6V | |

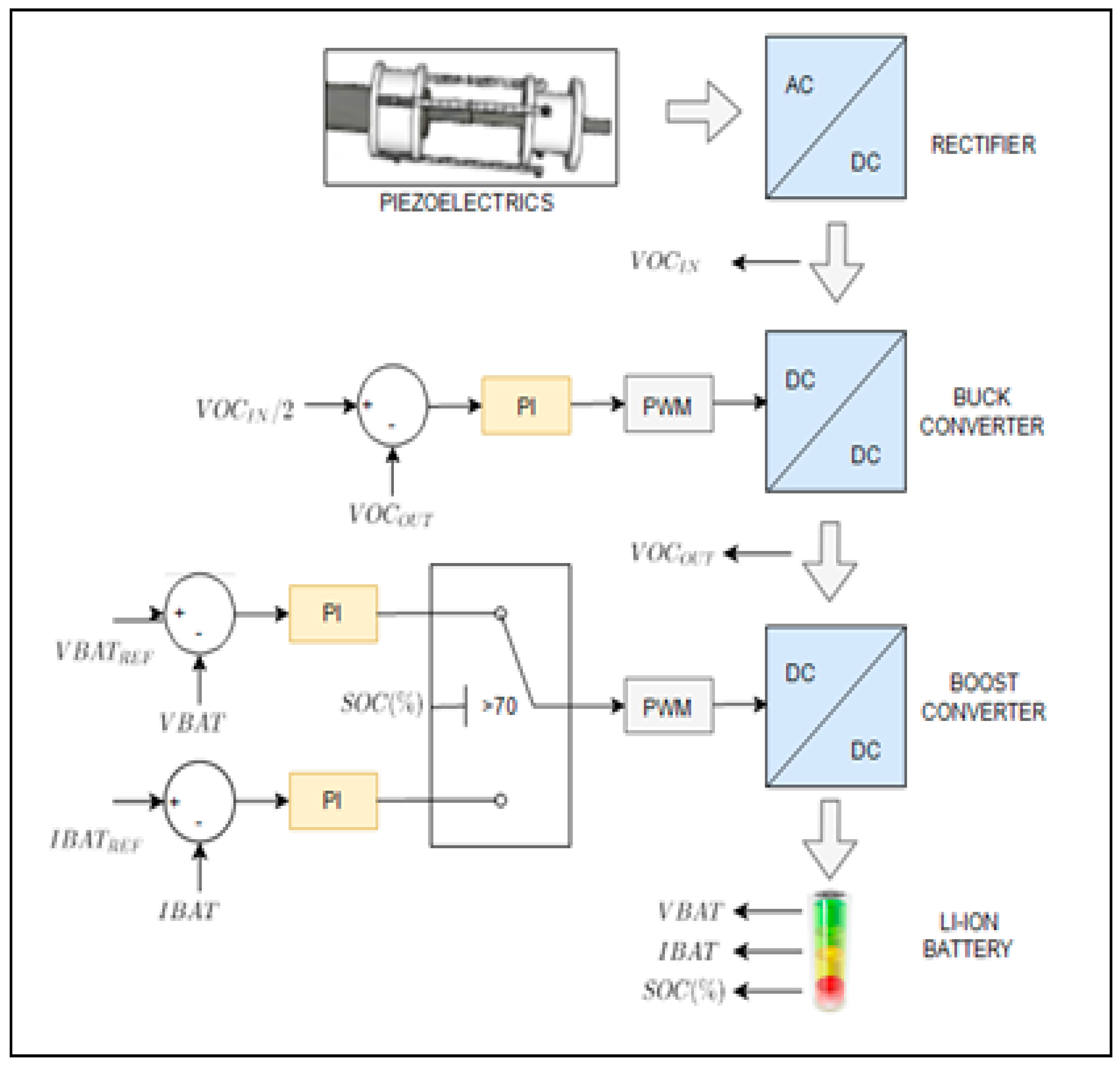

2.3. Controller

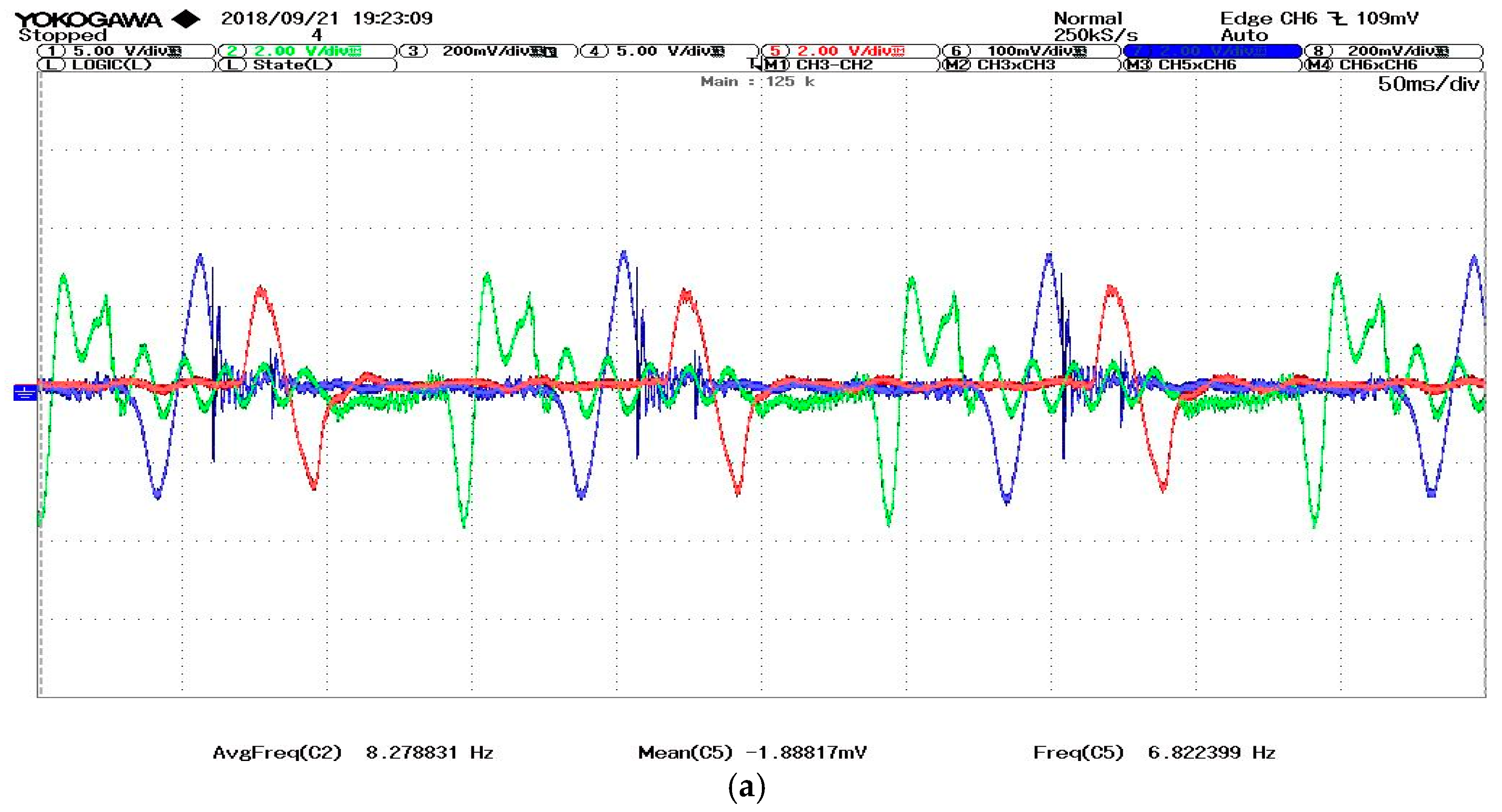

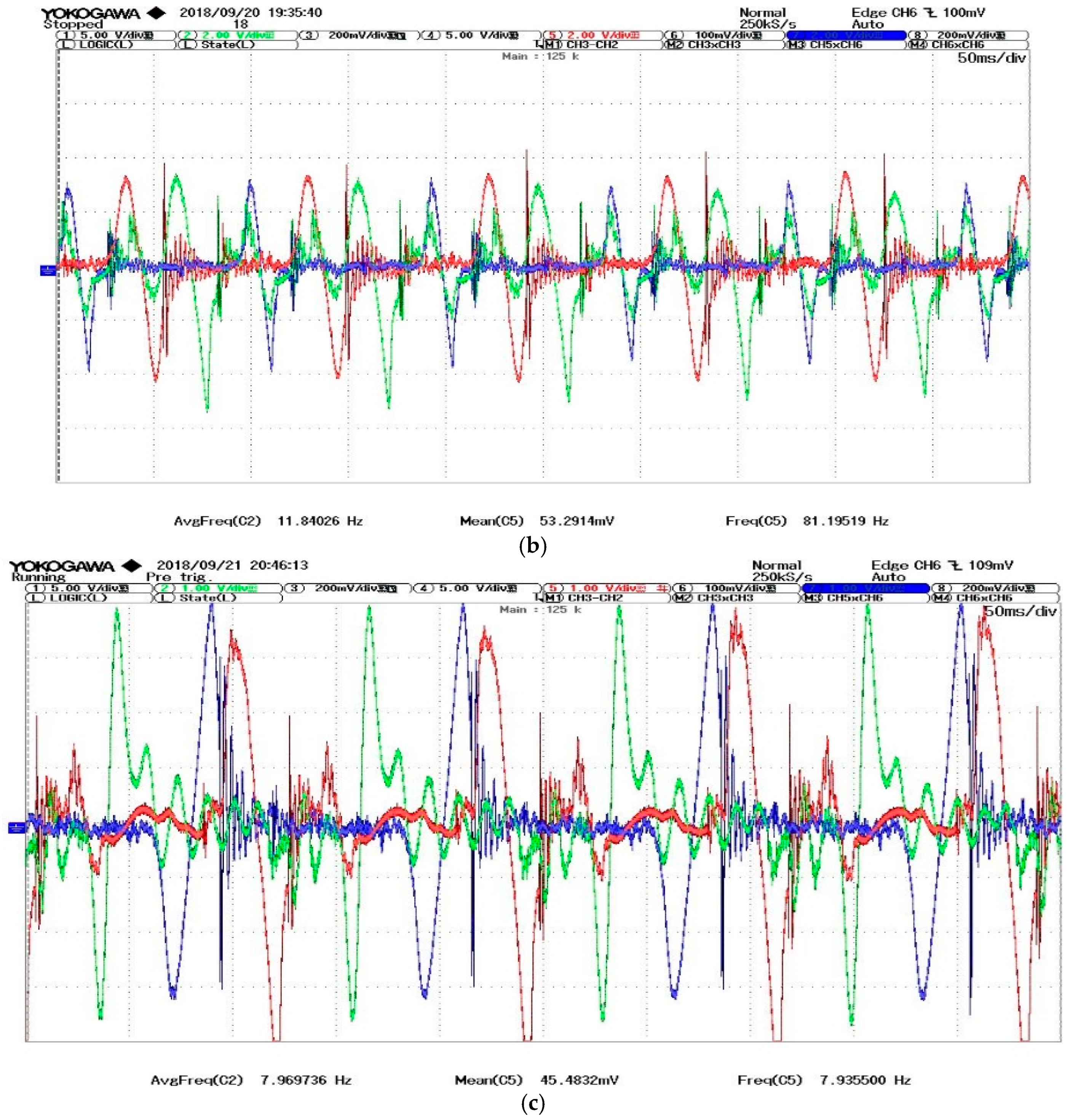

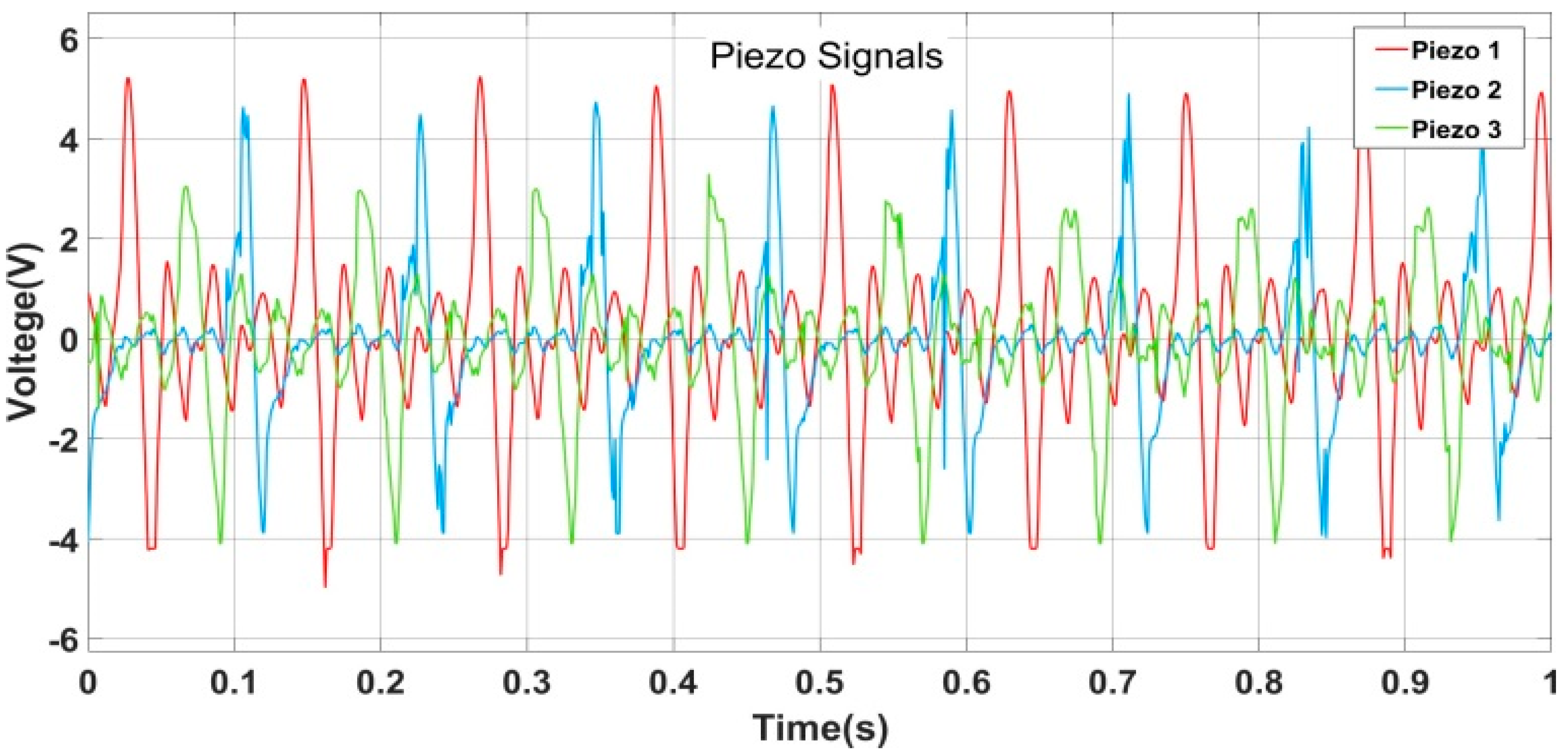

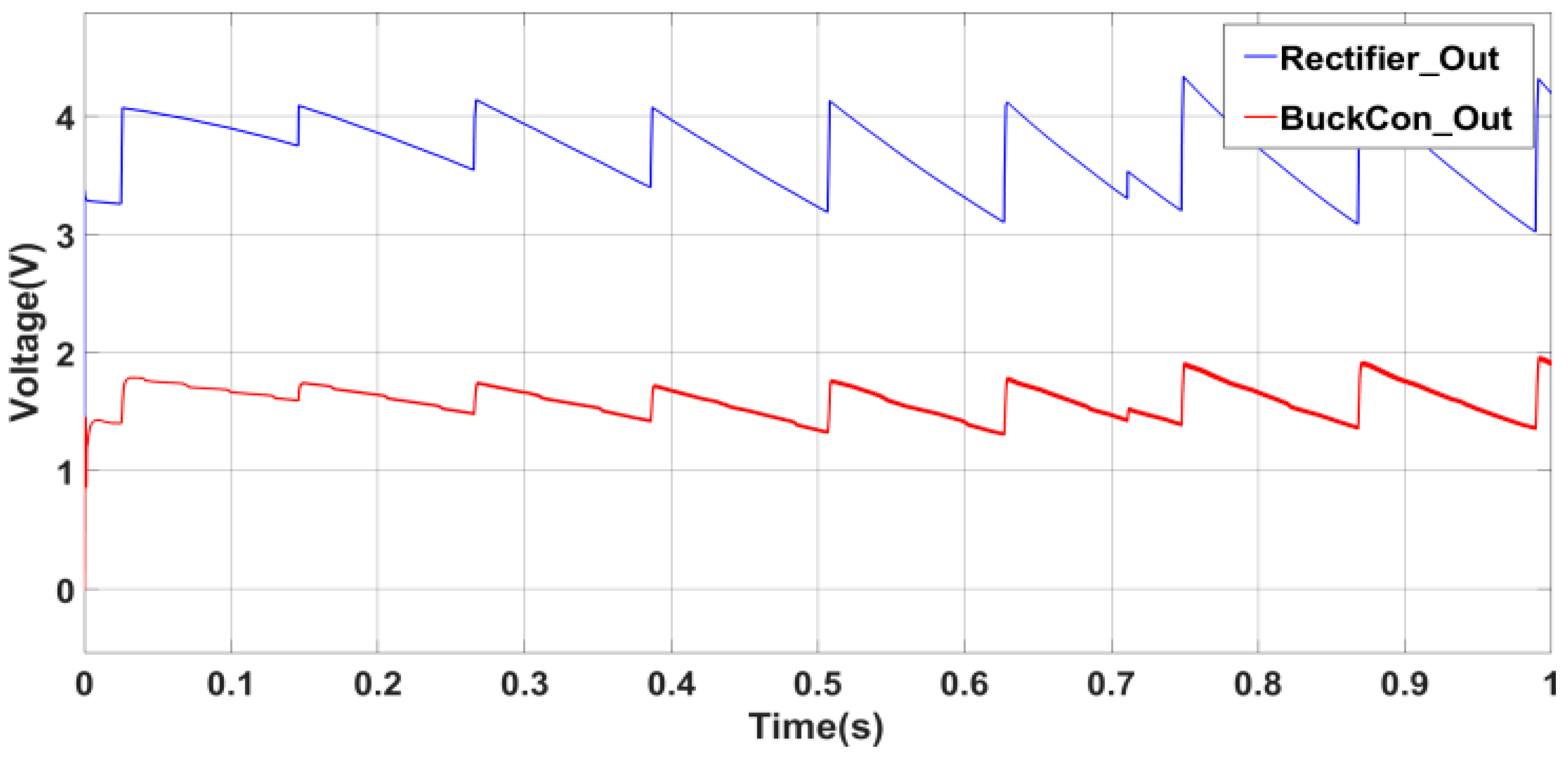

3. Experimental and Theoretical Work

4. Conclusions

References

- Bizon, N., Tabatabaei, N.M., Blaabjerg, F., Kurt, E., (Eds.), Energy Harvesting and Energy Efficiency: Technology, Methods, and Applications, Springer International Publishing (2017), doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49875-1.

- Harne, R.L. and K. Wang, A review of the recent research on vibration energy harvesting via bistable systems. Smart materials and structures, 2013. 22(2): p. 023001. [CrossRef]

- Toprak, A. and O. Tigli, Piezoelectric energy harvesting: State-of-the-art and challenges. Applied Physics Reviews, 2014. 1(3). [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.R.M., S. Mahmud, and B. Van Heyst, A comprehensive review on vibration based micro power generators using electromagnetic and piezoelectric transducer mechanisms. Energy Conversion and Management, 2015. 106: p. 728-747. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z., et al., A piezoelectric energy harvester for broadband rotational excitation using buckled beam. Aip Advances, 2018. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Singla, P. and S.R. Sarangi, A survey and experimental analysis of checkpointing techniques for energy harvesting devices. Journal of Systems Architecture, 2022. 126: p. 102464. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W., et al., Study on human motion energy harvesting devices: A review. Machines, 2023. 11(10): p. 977. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al., A Comprehensive Review on Iron-Based Sulfate Cathodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Nanomaterials, 2024. 14(23): p. 1915. [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K., Piezoelectric energy harvesting systems—Essentials to successful developments. Energy Technology, 2018. 6(5): p. 829-848. [CrossRef]

- Paul, T., et al., Cube shaped FAPbBr3 for piezoelectric energy harvesting devices. Materials Letters, 2021. 301: p. 130264. [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.A., Energy harvesting devices in pavement structures. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 2025. 10(5): p. 183. [CrossRef]

- Friswell, M.I. and S. Adhikari, Sensor shape design for piezoelectric cantilever beams to harvest vibration energy. Journal of Applied Physics, 2010. 108(1). [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.-h., et al., Recent progress and perspective of cathode recycling technology for spent LiFePO4 batteries. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2024. 133: p. 65-73. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S., M.a. Friswell, and D. Inman, Piezoelectric energy harvesting from broadband random vibrations. Smart materials and structures, 2009. 18(11): p. 115005. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S., J.-H. Kim, and J. Kim, A review of piezoelectric energy harvesting based on vibration. International journal of precision engineering and manufacturing, 2011. 12: p. 1129-1141.

- Jin, K., et al., Recent progress in aqueous underwater power batteries. Discover Applied Sciences, 2024. 6(8): p. 441. [CrossRef]

- Nechibvute, A., A. Chawanda, and P. Luhanga, Piezoelectric energy harvesting devices: an alternative energy source for wireless sensors. Smart Materials Research, 2012. 2012(1): p. 853481. [CrossRef]

- Glynne-Jones, P., et al., An electromagnetic, vibration-powered generator for intelligent sensor systems. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2004. 110(1-3): p. 344-349. [CrossRef]

- Torah, R., et al. Autonomous low power microsystem powered by vibration energy harvesting. in SENSORS, 2007 IEEE. 2007. IEEE.

- Ambrożkiewicz, B., G. Litak, and P. Wolszczak, Modelling of electromagnetic energy harvester with rotational pendulum using mechanical vibrations to scavenge electrical energy. Applied Sciences, 2020. 10(2): p. 671. [CrossRef]

- Płaczek, M. and Ł. Dulat, Supporting the Design of Systems for Energy Recovery from Mechanical Vibrations Containing MFC Piezoelectric Transducers. Applied Sciences, 2025. 15(10): p. 5530. [CrossRef]

- von Büren, T. and G. Tröster, Design and optimization of a linear vibration-driven electromagnetic micro-power generator. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2007. 135(2): p. 765-775.

- Mitcheson, P.D., et al., MEMS electrostatic micropower generator for low frequency operation. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2004. 115(2-3): p. 523-529. [CrossRef]

- Ghashami, G., et al., Energy harvesting from mechanical vibrations: self-rectification effect. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2023. 25(20): p. 14400-14405. [CrossRef]

- Khbeis, M., J. McGee, and R. Ghodssi. Development of a simplified hybrid ambient low frequency, low intensity vibration energy scavenger system. in TRANSDUCERS 2009-2009 International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference. 2009. IEEE.

- Erturk, A., Electromechanical modeling of piezoelectric energy harvesters. 2009.

- Choi, W., et al., Energy harvesting MEMS device based on thin film piezoelectric cantilevers. Journal of Electroceramics, 2006. 17: p. 543-548. [CrossRef]

- Sodano, H.A., D.J. Inman, and G. Park, Comparison of piezoelectric energy harvesting devices for recharging batteries. Journal of intelligent material systems and structures, 2005. 16(10): p. 799-807. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A. and F. Motaei, A review of phononic-crystal-based energy harvesters. Progress in Energy, 2024. 7(1): p. 012002. [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, H., et al., Design, Modeling, and Experimental Validation of a Hybrid Piezoelectric–Magnetoelectric Energy-Harvesting System for Vehicle Suspensions. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 2025. 16(4): p. 237. [CrossRef]

- Mitcheson, P.D., T.C. Green, and E.M. Yeatman, Power processing circuits for electromagnetic, electrostatic and piezoelectric inertial energy scavengers. Microsystem Technologies, 2007. 13: p. 1629-1635. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I., Review of state of art of smart structures and integrated systems. AIAA journal, 2002. 40(11): p. 2145-2187.

- Priya, S., Advances in energy harvesting using low profile piezoelectric transducers. Journal of electroceramics, 2007. 19: p. 167-184. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H. and E.M. Yeatman, A miniaturized piezoelectric turbine with self-regulation for increased air speed range. Applied Physics Letters, 2015. 107(24). [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K. and T. Ishii, Energy flow analysis in piezoelectric energy harvesting systems. Ferroelectrics, 2010. 400(1): p. 305-320. [CrossRef]

- Renaud, M., et al., Harvesting energy from the motion of human limbs: the design and analysis of animpact-based piezoelectric generator. Smart Materials and Structures, 2009. 18(3): p. 035001. [CrossRef]

- Uzun, Y. and E. Kurt, Performance exploration of an energy harvester near the varying magnetic field of an operating induction motor. Energy conversion and management, 2013. 72: p. 156-162. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., et al., Road energy harvester designed as a macro-power source using the piezoelectric effect. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2016. 41(29): p. 12563-12568. [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, P. and A.K. Thakur, ENERGY HARVESTING & STORAGE.

- Uzun, Y., S. Demirbaş, and E. Kurt, Implementation of a new contactless piezoelectric wind energy harvester to a wireless weather station. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., et al., Consideration of impedance matching techniques for efficient piezoelectric energy harvesting. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, 2007. 54(9): p. 1851-1859. [CrossRef]

- Kurt, E., et al., Design and implementation of a maximum power point tracking system for a piezoelectric wind energy harvester generating high harmonicity. Sustainability, 2021. 13(14): p. 7709. [CrossRef]

- Du, S., et al. Rectified Output Power Analysis of Piezoelectric Energy Harvester Arrays under Noisy Excitation. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2018. IOP Publishing.

- Kurt, E., et al., Design and implementation of a new contactless triple piezoelectrics wind energy harvester. international journal of hydrogen energy, 2017. 42(28): p. 17813-17822. [CrossRef]

- Chew, Z.J. and M. Zhu, Adaptive maximum power point finding using direct V OC/2 tracking method with microwatt power consumption for energy harvesting. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 2017. 33(9): p. 8164-8173. [CrossRef]

- Sinkaram, C., V.S. Asirvadam, and N.B.M. Nor. Capacity study of lithium ion battery for hybrid electrical vehicle (HEV) a simulation approach. in 2013 IEEE International Conference on Signal and Image Processing Applications. 2013. IEEE.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).