Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

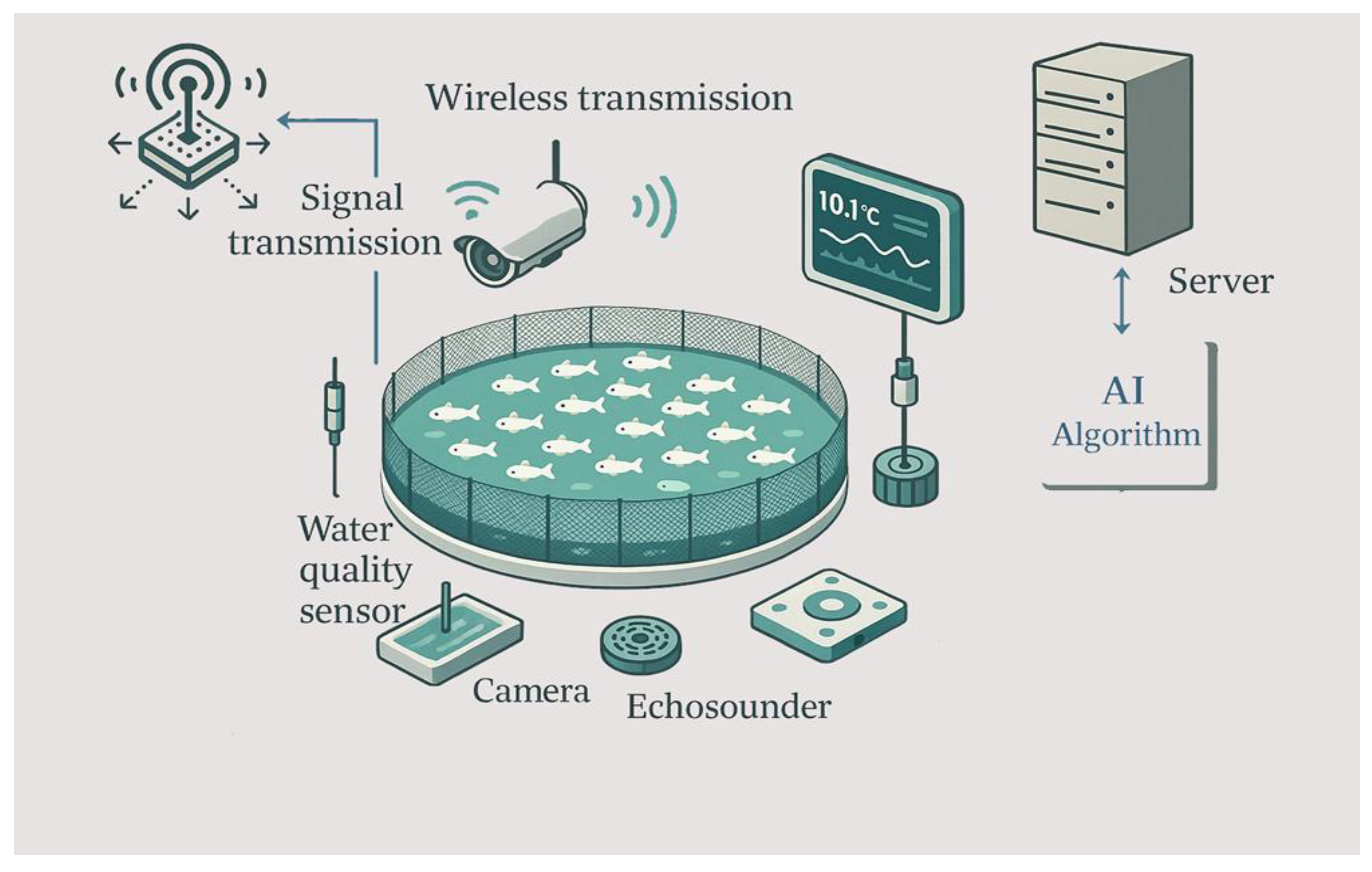

2. PFF Methods in the Aquaculture Sector

2.1. Computer Vision Methods

2.1.1. Artificial Vision Based on Visible Light

2.1.2. Artificial Vision Based on Infrared Light

2.1.3. Stereo Vision Systems

2.1.4. Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) Technology

2.2. Acoustic Methods

2.2.1. Active Acoustics

2.2.1.1. Sonars

2.2.1.2. Echosounder

2.2.2. Passive Acoustics

2.2.2.1. Underwater Microphones

2.3. Sensor-Based Methods

2.3.1. Environmental Sensors

2.3.2. Acoustic Transmitters

2.3.3. Biosensors

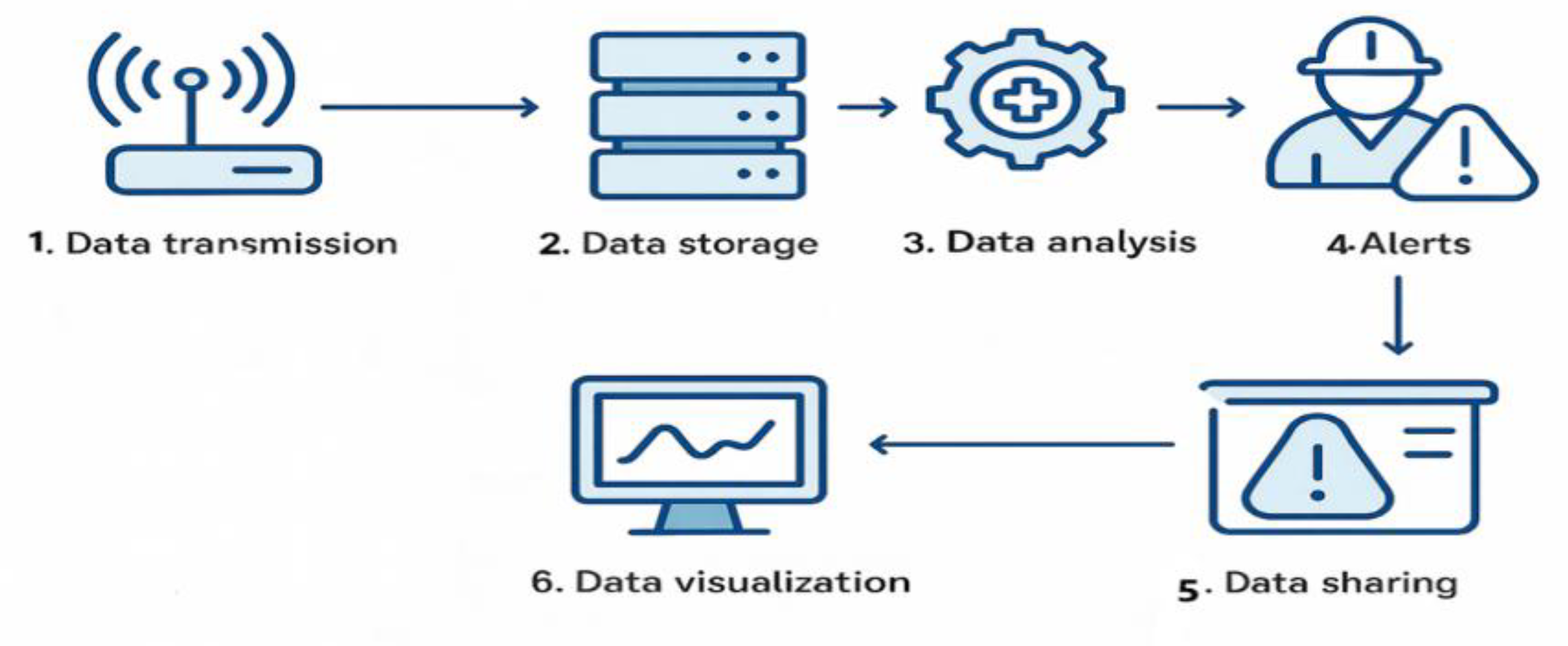

3. Automatic Monitoring and Data Analysis

4. Tasks and Models of AI

4.1. Supervised Learning

4.2. Unsupervised Learning

4.3. Semi-Supervised Learning

4.4. Reinforcement Learning

5. Using AI in Water Quality Monitoring

6. Use of AI in Fish Biomass Estimation

7. Use of AI in Fish Feeding Activities

8. Stock Assessment of Farmed Fish

9. Integration of Feeding Practices with Behaviour and Welfare Monitoring

10. Challenges and Future Prospects

10.1. Quality and Availability of Real-Time Data

10.3. Implementation Costs

9. Conclusions

References

- Huang, M.; Zhou, Y.G.; Yang, X.G. Optimizing feeding frequencies in fish: a meta-analysis and machine learning approach. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Føre, M.; Frank, K.; Norton, T.; Svendsen, E.; Alfredsen, J.A.; Dempster, T.; Eguiraun, H.; Watson, W.; Stahl, A.; Sunde, L.M.; Schellewald, C.; Skøien, K.R.; Alver, M.O.; Berckmans, D. Precision fish farming: a new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 173, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. Application of machine learning in intelligent fish aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.E.; Ko, H.; Huh, J.H.; Kim, Y. Overview of smart aquaculture system: focusing on applications of machine learning and computer vision. Electronics 2021, 10, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijs, J.; Føre, M.; Gräns, A.; Clark, T.D.; Axelsson, M.; Johansen, J.L. Biosensing technologies in aquaculture: how remote monitoring can bring us closer to our farm animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Du, R.; Kong, Q.; Li, D.; Liu, C. MSIF-MobileNetV3: an improved MobileNetV3 based on multi-scale information fusion for fish feeding behavior analysis. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 102, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberioon, M.; Gholizadeh, A.; Cisar, P.; Pautsina, A.; Urban, J. Application of machine vision systems in aquaculture with emphasis on fish: state-of-the-art and key issues. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudhane, M.; Nsiri, B. Underwater image processing method for fish localization and detection in submarine environment. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2016, 39, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Miao, Z.; Du, L.; Duan, Y. Automatic recognition methods of fish feeding behavior in aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.P.; Balucha, M.F.; Makrariyab, A.; MusheerAziz, R. Image processing model with deep learning approach for fish species classification. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2022, 13, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Zhou, Y.G.; Yang, X.G. Optimizing feeding frequencies in fish: a meta-analysis and machine learning approach. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Føre, M.; Frank, K.; Norton, T.; Svendsen, E.; Alfredsen, J.A.; Dempster, T.; Eguiraun, H.; Watson, W.; Stahl, A.; Sunde, L.M.; Schellewald, C.; Skøien, K.R.; Alver, M.O.; Berckmans, D. Precision fish farming: a new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 173, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.L.; Smith, N.; Whoriskey, F.; Devitt, S.; Novaczek, E.; Morris, C.J.; Kess, T.; Bradbury, I.; Iverson, S.; Bentzen, P.; Ruzzante, D.E. Northern cod (Gadus morhua) movement: insights from acoustic telemetry and genomics. 2025 J. Fish. Biol. 4.

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. Application of machine learning in intelligent fish aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.E.; Ko, H.; Huh, J.H.; Kim, Y. Overview of smart aquaculture system: focusing on applications of machine learning and computer vision. Electronics 2021, 10, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijs, J.; Føre, M.; Gräns, A.; Clark, T.D.; Axelsson, M.; Johansen, J.L. Biosensing technologies in aquaculture: how remote monitoring can bring us closer to our farm animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Du, R.; Kong, Q.; Li, D.; Liu, C. MSIF-MobileNetV3: an improved MobileNetV3 based on multi-scale information fusion for fish feeding behavior analysis. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 102, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberioon, M.; Gholizadeh, A.; Cisar, P.; Pautsina, A.; Urban, J. Application of machine vision systems in aquaculture with emphasis on fish: state-of-the-art and key issues. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudhane, M.; Nsiri, B. Underwater image processing method for fish localization and detection in submarine environment. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2016, 39, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Miao, Z.; Du, L.; Duan, Y. Automatic recognition methods of fish feeding behavior in aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.P.; Balucha, M.F.; Makrariyab, A.; MusheerAziz, R. Image processing model with deep learning approach for fish species classification. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2022, 13, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Føre, M.; Alfredsen, J.A.; Gronningsater, A. Development of two telemetry-based systems for monitoring the feeding behaviour of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in aquaculture sea-cages. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 76, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, S.; Zupa, W.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G.; Carbonara, P. Using telemetry sensors mapping the energetic costs in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) as a tool for welfare remote monitoring in aquaculture. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, P.; Alfonso, S.; Dioguardi, M.; Zupa, W.; Vazzana, M.; Dara, M.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G.; Cammarata, M. Calibrating accelerometer data as a promising tool for health and welfare monitoring in aquaculture: case study in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in conventional or organic aquaculture. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 21, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Føre, M.; Svendsen, E.; Alfredsen, J.A. Using acoustic telemetry to monitor the effects of crowding and delousing procedures on farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 2017, 495, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesto, M.; Zupa, W.; Alfonso, S.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G.; Carbonara, P. Using acoustic telemetry to assess behavioral responses to acute hypoxia and ammonia exposure in farmed rainbow trout of different competitive ability. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 230, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenroth, D.K.; Vaestad, B.; Økland, F.; Finstad, B.; Olsen, R.E.; Svendsen, E.; Rosten, C.; Axelsson, M.; Bloecher, N.; Føre, M.; Gräns, A. Under the sea: How can we use heart rate and accelerometers to remotely assess fish welfare in salmon aquaculture? Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Moll, E.; Piazzon, M.C.; Sosa, J.; Ferrer, M.; Cabruja, E.; Vega, A.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Sitja-Bobadilla, A.; Lozano, M.; Montiel-Nelson, J.A.; Afonso, J.M.; Pérez-Sanchez, J. Use of accelerometer technology for individual tracking of activity patterns, metabolic rates and welfare in farmed gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) facing a wide range of stressors. Aquaculture 2021, 539, 736609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupa, W.; Alfonso, S.; Gai, F.; Gasco, L.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G.; Carbonara, P. Calibrating accelerometer tags with oxygen consumption rate of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and their use in aquaculture facility: A case study. Animals 2021, 11, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, G.; Warren-Myers, F.; Barrett, L.; Oppedal, F.; Føre, M.; Dempster, T. Tag use to monitor fish behaviour in aquaculture: a review of benefits, problems and solutions. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 15, 1565–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, L.; Aspillaga, E.; Palmer, M.; Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P. Acoustic telemetry: a tool to monitor fish swimming behavior in sea-cage aquaculture. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 545896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palstra, A.P.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Xue, Y.; Roque, A. Accelerometry of seabream in a sea-cage: is acceleration a good proxy for activity? Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 639608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrewartha, S.J.; Elliott, N.G.; McCulloch, J.W.; Frappell, P.B. Aquaculture sentinels: smart-farming with biosensor equipped stock. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2015, 7, 100393. [Google Scholar]

- Gesto, M.; Hernández, J.; López-Patiño, M.A.; Soengas, J.L.; Míguez, J.M. Is gill cortisol concentration a good acute stress indicator in fish? A study in rainbow trout and zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 188, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.C.; Yan, W.M.; Bhat, S.A.; Huang, N.F. Development of smart aquaculture farm management system using IoT and AI-based surrogate models. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 9, 00357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, D.; Zhou, C.; Sun, C.; Yang, X. Simulation of collective swimming behavior of fish schools using a modified social force and kinetic energy model. Ecol. Model. 2017, 360, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Schraml, R.; Hofbauer, H.; Jalilian, E.; Bekkozhayeva, D.; Saberioon, M.; Cisar, P.; Uhl, A. Towards fish individuality-based aquaculture. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 4356–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fore, M.; Alver, M.; Alfredsen, J.A.; Marafioti, G.; Senneset, G.; Birkevold, J.; Willumsen, F.V.; Lange, G.; Espmark, A.; Terjesen, B.F. Modelling growth performance and feeding behaviour of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in commercial-size aquaculture net pens: model details and validation through full-scale experiments. Aquaculture 2016, 464, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M. Real-time IoT dataset of pond water for fish farming (multi-pond). Data Brief 2023, 49, 10911. [Google Scholar]

- Prapti, D.R.; Mohamed Shariff, A.R.; Che Man, H.; Ramli, N.M.; Perumal, T.; Shariff, M. Internet of Things (IoT)-based aquaculture: An overview of IoT application on water quality monitoring. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Fan, Z.; Nikolaeva, A.; Bao, H. Redefining aquaculture safety with artificial intelligence: design innovations, trends and future perspectives. Fishes 2025, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, H.; Nadi, F.; Lam, S.S. Internet of Things in aquaculture: a review of the challenges and potential solutions based on current and future trends. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, U.F.; Alhassan, A.W.; Jiang, D.N.; Li, G.L. Sustainable aquaculture development: a review on the roles of cloud computing, internet of things and artificial intelligence (CIA). Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 2076–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, X.F.; Xie, Y.G. Deep learning in aquaculture: a review. J. Comput. 2020, 31, 294–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhou, C.; Sun, C. Fish behavior classification using image texture features and support vector machines. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, F.; Zhou, C.; Xu, D.; Sun, C.; Yang, X. Automatic analysis of fish location and quantity in aquaculture ponds using image preprocessing and edge detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 119, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, T.; Abdul Razak, R.; Rahiman, M.D.; Nor, A. Artificial intelligence methods used in various aquaculture applications: a systematic literature review. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, e13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Wang, Z.J.; Ali, Z.A. Automatic fish species classification using deep convolutional neural networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 116, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Khabusi, S.P. Artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) advances in aquaculture: a review. Processes 2025, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arepalli, P.G. IoT-based DSTCNN for aquaculture water-quality monitoring. Aquac. Eng. 2024, 108, 102369. [Google Scholar]

- Shete, R.P. IoT-enabled real-time WQ monitoring for aquafarming using Arduino measurement. Sensors 2024, 27, 10064. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, P.W.; Byun, Y.C. Optimized dissolved oxygen prediction using genetic algorithm and bagging ensemble learning for smart fish farm. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 15153–15164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Han, G.J. TD-LSTM: temporal dependence-based LSTM networks for marine temperature prediction. Sensors 2018, 18, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Wei, Y.; An, D. Research of dissolved oxygen prediction in recirculating aquaculture systems based on deep belief network. Aquac. Eng. 2020, 90, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claireaux, G.; Couturier, C.; Groison, A.L. Effect of temperature on maximum swimming speed and cost of transport in juvenile European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3420–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoundouros, G.; Sfakianakis, D.G.; Divanach, P.; Kentouri, M. Effect of temperature on swimming performance of sea bass juveniles. J. Fish Biol. 2002, 60, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.C.; Chen, L.B.; Huang, B.K.; Lin, H.M. A computer vision-based intelligent fish feeding system using deep learning techniques for aquaculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 22, 7185–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.C.; Chen, L.B.; Wang, B.H. Design and implementation of a full-time artificial intelligence of things-based water quality inspection and prediction system for intelligent aquaculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 3811–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.S.; Prabhaker, L.C.; Shanmugapriya, T. Water quality evaluation and monitoring model (WQEM) using machine learning techniques with IoT. Water Resour. 2024, 51, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Navarro, R.; Carriazo-Regino, Y.; Torres-Hoyos, F.; Pinedo-López, J. Intelligent prediction & continuous monitoring of pond water quality with ML + quantum optimization. Water 2025, 17, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Eneh, A.H.; Udanor, C.N.; Ossai, N.I.; Aneke, S.O.; Ugwoke, P.O.; Obayi, A.A.; Ugwuishiwu, C.H.; Okereke, G.E. Improving IoT sensor data quality in aquaculture WQ systems (LoRa/Arduino cases). Sensors 2023, 26, 100625. [Google Scholar]

- Arepalli, P.G.; Khetavath, J.N. An IoT framework for quality analysis of aquatic water data using time-series convolutional neural network. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 125275–125294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayoun, M.N.I.; Hossain, S.A.; Rezaul, K.M.; Siddiquee, K.N.E.A.; Islam, M.S.; Jannat, T. Internet of Things-driven precision in fish farming: A deep dive into automated temperature, oxygen, and pH regulation. Computers 2024, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Cheng, S.C. A low-cost AI buoy system for monitoring water quality at offshore aquaculture cages. Sensors 2022, 22, 4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Zhang, J.X.; Chen, Y.H. IoT-based fish farm water quality monitoring system. Sensors 2022, 22, 6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Tsai, H.; Lyu, W.H. An integrated wireless multi-sensor system for monitoring the water quality of aquaculture. Sensors 2021, 21, 8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Iwasaki, M.; Guadalupe, G.A.; Pachas-Caycho, M.; Chapa-Gonza, S.; Mori-Zabarburú, R.C.; Guerrero-Abad, J.C. IoT sensors for water-quality monitoring in aquaculture: systematic review & bibliometrics (2020–2024). AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, R.; Li, D.; Shi, C. Fully automatic system for fish biomass estimation based on deep neural network. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 79, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravata, N.; Kelly, D.; Eickholt, J.; Bryan, J.; Miehls, S. Applications of deep convolutional neural networks to predict length, circumference, and weight from mostly dewatered images of fish. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 9313–9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Tejeida, S.; Soto-Zarazua, G.M.; Toledano-Ayala, M.; Contreras-Medina, L.M.; Rivas-Araiza, E.A.; Flores-Aguilar, P.S. An improved method to obtain fish weight using machine learning and NIR camera with haar cascade classifier. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittún, Ó.F.; Andersen, L.E.J.; Svendsen, M.B.S.; Steffensen, J.F. An inexpensive 3D camera system based on a completely synchronized stereo camera, open-source software, and a Raspberry Pi for accurate fish size, position, and swimming speed. Fishes 2025, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.C.; Chen, B.; Huang, B.K. A computer vision-based intelligent fish feeding system using deep learning techniques for aquaculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 7185–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Review: computer vision for fish feeding-behaviour analysis & practice. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 271, 105880. [Google Scholar]

- Måløy, H.; Aamodt, A.; Misimi, E. A spatio-temporal recurrent network for salmon feeding action recognition from underwater videos in aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 167, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Huang, J.; Wei, Y. A survey of fish behaviour quantification indexes and methods in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 2169–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Georgopoulou, D.G.; Ebbesson, L.O.E.; Voskakis, D.; Lal, P.; Papandroulakis, N. Food anticipatory behaviour on European seabass in sea cages: activity-, positioning- and density-based approaches. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D. A customized recurrent neural network for fish behavior analysis. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, B.; Hu, Q.; Li, W. Multimodal knowledge distillation framework for fish feeding behaviour recognition in industrial aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 255, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, S.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, B.; Ke, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, P. YOLO-feed: An advanced lightweight network enabling real-time, high-precision detection of feed pellets on CPU devices and its applications in quantifying individual fish feed intake. Aquaculture 2025, 608, 742700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, D.G.; Vouidaskis, C.; Papandroulakis, N. Swimming behavior as a potential metric to detect satiation levels of European seabass in marine cages. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 135038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L. A two-stage framework for fish behavior recognition: modified YOLOv8 and ResNet-like model. Aquaculture 2024, 575, 112345. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Tu, W.; Gu, L. Fish behavior recognition based on an audio-visual multimodal interactive fusion network. Aquac. Eng. 2024, 107, 102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, T.; Lin, J.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Li, D. DeformAtt-ViT: A largemouth bass feeding intensity assessment method based on Vision Transformer with deformable attention. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Wei, D.; Peng, Z.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tang, R.; Tian, X.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Z. An appetite assessment method for fish in outdoor ponds with anti-shadow disturbance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.X.; Cui, H.W.; Qu, K.M. A fish appetite assessment method based on improved ByteTrack and spatiotemporal graph convolutional network. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 240, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Jia, B.; Zhou, C.; Ye, H. Detection method of fry feeding status based on YOLO lightweight network by shallow underwater images. Electronics 2022, 11, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, D.; Li, D. Fish behavior recognition using audio spectrum swin transformer network. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 101, 102320. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, T.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Xu, D. Spatio-temporal attention network for swimming and spatial features of pompano. Sensors 2023, 23, 3124. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Fish broodstock behavior recognition using ResNet50-LSTM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 106987. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. LC-GhostNet: Lightweight multimodal neural network for fish behavior recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107780. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, C. Fish feeding intensity quantification using machine vision and a lightweight 3D ResNet-GloRe network. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 98, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Q. A MobileNetV2-SENet-based method for identifying fish school feeding behavior. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 99, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, S.L. Real-time detection and tracking of fish abnormal behavior based on improved YOLOv5 and SiamRPN++. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 192, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, D. CFFI-ViT: enhanced vision transformer for the accurate classification of fish feeding intensity. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ding, W.; Zhao, S.; Gu, J. Adaptive neural fuzzy inference system for feeding decision-making of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) in outdoor intensive culturing ponds. Aquaculture 2019, 498, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.X.; Muhammad, A.; Liu, C. Automatic recognition of fish behavior with a fusion of RGB and optical flow data based on deep learning. Animals 2021, 11, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubina, F.C.; Estuar, M.R.J.E.; Ubina, C.D. Optical flow neural network for fish swimming behavior and activity analysis. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Gao, Q.; Dong, S.; Zhou, C. Deep learning for smart fish farming: applications, opportunities and challenges. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saminiano, B. Feeding behavior classification of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) using convolutional neural network. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Duan, Q. Application of convolutional neural networks (CNN) for fish feeding detection. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2020, 11, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, R.; Turra, E.M.; de Alvarenga, R.; Passafaro, T.L.; Lopes, F.B.; Alves, G.F.; Singh, V.; Rosa, G.J. Deep learning-based analysis of fish feeding images using CNNs. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100426. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, D.; Sun, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, L. Delaunay triangulation and texture analysis for fish behavior recognition in aquaculture. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 1751–1762. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, L.; Lu, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y. Measuring feeding activity of fish in RAS using computer vision. Aquac. Eng. 2014, 60, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, M.A.; Aibinu, A.M.; Kolo, J.G. Incorporating intelligence in fish feeding system for dispensing feed based on fish feeding intensity. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 91948–91960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, Y.; Srivastava, S.; Liu, X.M. Automatic feeding control for dense aquaculture fish tanks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2015, 22, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhou, Y.G.; Yang, X.G.; Gao, Q.F.; Chen, Y.N.; Ren, Y.C.; Dong, S.L. Optimizing feeding frequencies in fish: a meta-analysis and machine learning approach. Aquaculture 2024, 595, 741678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, C. Enhanced CNN frameworks for identifying feeding behavior in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2023, 561, 738682. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayalakshmi, M.; Sasithradevi, A. AquaYOLO: Advanced YOLO-based fish detection for optimized aquaculture pond monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, D.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Sun, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of fish feeding intensity in aquaculture using a convolutional neural network and machine vision. Aquaculture 2019, 507, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Yang, Z.; Gao, T.; Liang, M.; Liu, P.; Zhou, S.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y. Efficient recognition of fish feeding behavior: a novel two-stage framework pioneering intelligent aquaculture strategies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.Y.; Zhao, S.L.; Duan, Y.Q. MMFINet: a multimodal fusion network for accurate fish feeding intensity assessment in recirculating aquaculture systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Becerra, A.T.; Bienvenido-Barcena, J.F.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, C. CFFI-ViT: enhanced vision transformer for the accurate classification of fish feeding intensity in aquaculture. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Yang, X.; Hu, W.; Fu, T.; Zhou, C. Fish feeding behavior recognition using time-domain and frequency-domain signals fusion from six-axis inertial sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Cui, X.; Xu, Z.; Bai, J.; Han, W.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, D. Harnessing multimodal data fusion to advance accurate identification of fish feeding intensity. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 246, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayan, A.A.; Saha, J.; Mozumder, A.N.; Mahmud, K.R.; Al Azad, A.K.; Kibria, M.G. A machine learning approach for early detection of fish diseases by analyzing water quality. Trends Sci. 2021, 18, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donncha, F.; Stockwell, C.L.; Planellas, S.R.; Micallef, G.; Palmes, P.; Webb, C.; Filgueira, R.; Grant, J. Data driven insight into fish behaviour and their use for precision aquaculture. Front. Anim. Sci. 2021, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Ghosh, A.R. Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in fish growth and health status monitoring: A review on sustainable aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2791–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.; Goncalves, W.N.; Zanoni, V.A.G.; Dos Santos De Arruda, M.; de Araujo Carvalho, M.; Nascimento, E.; Marcato, J.; Diemer, O.; Pistori, H. Counting tilapia larvae using images captured by smartphones. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.B.; Liu, H.H. Fish tracking, counting and behaviour analysis in digital aquaculture: a comprehensive survey. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoul, B.; Alfonso, S.; Cousin, X.; Prunet, P.; Bégout, M.L.; Leguen, I. Global assessment of the response to chronic stress in European sea bass. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, P.; Alfonso, S.; Zupa, W.; Manfrin, A.; Fiocchi, E.; Pretto, T.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G. Behavioral and physiological responses to stocking density in sea bream (Sparus aurata): Do coping styles matter? Physiol. Behav. 2019, 212, 112698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.L.; Wang, G.X.; Du, L. Recent advances in intelligent recognition methods for fish stress behavior. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 96, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarevic, J.; Aas-Hansen, Ø.; Espmark, Å.; Baeverfjord, G.; Terjesen, B.F.; Damsgård, B. The use of acoustic acceleration transmitter tags for monitoring of Atlantic salmon swimming activity in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). Aquac. Eng. 2016, 72, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alpiste, I.; De Tailly, J.B.; Alcaraz-Calero, J.M. Machine learning-based understanding of aquatic animal behaviour in high-turbidity waters. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, P.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. Appearance-motion autoencoder network (AMA-Net) for behavior recognition of Oplegnathus punctatus. Aquaculture 2023, 569, 739302. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; An, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. Recognizing fish behavior in aquaculture with graph convolutional network. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 98, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Xu, W.; Zhao, J.; Sun, F. Active learning with VGG16 for behavior detection in Oplegnathus punctatus. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 96, 102175. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Xu, D.; Zhou, C.; Chen, L. Automated monitoring of fish behavior in recirculating aquaculture systems using edge detection and segmentation methods. Aquac. Eng. 2015, 67, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoul, B.; Vijayan, M.M.; Schram, E.; Aluru, N.; Wendelaar Bonga, S.E. Physiological and behavioral responses to multiple stressors in farmed fish: application of imaging and dispersion indices. Aquaculture 2014, 432, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkiewicz, T.H.; Purser, G.J.; Williams, R.N. A computer vision system to analyse the swimming behaviour of farmed fish in commercial aquaculture facilities: A case study using cage-held Atlantic salmon. Aquac. Eng. 2011, 45, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.F.; Zhu, J.C.; Liu, B. Fish shoals behavior detection based on convolutional neural network and spatiotemporal information. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126907–126926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, D.D.; Zhang, Y.F. Real-time nondestructive fish behavior detecting in mixed polyculture system using deep learning and low-cost devices. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 178, 115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, U.; Li, D.L.; Akhter, M. Intelligent diagnosis of fish behavior using deep learning method. Fishes 2022, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, C.; Bronstein, M.; Raskin, A. Using machine learning to decode animal communication. Science 2023, 381, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad Saoud, L.; Sultan, A.; Elmezain, M. Beyond observation: deep learning for animal behavior and ecological conservation. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 84, 102893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Lee, S.K.; Lai, Y.C.; Lin, C.C.; Wang, T.Y.; Lin, Y.R.; Hsu, T.H.; Huang, C.W.; Chiang, C.P. Anomalous behaviors detection for underwater fish using AI techniques. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 224372–224382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Qin, H.X.; Xu, L.A. Review of deep learning-based stereo vision techniques for phenotype feature and behavioral analysis of fish in aquaculture. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Wu, J.F.; Kong, H. A video object segmentation-based fish individual recognition method for underwater complex environments. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Johnson, Z.V.; Li, J.; Lancaster, T.J.; Aljapur, V.; Streelman, J.T.; McGrath, P.T. Automatic classification of cichlid behaviors using 3D convolutional residual networks. iScience 2020, 23, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhou, C.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ye, H. BlendMask-VoNetV2: Robust detection of overlapping fish behavior in aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108023. [Google Scholar]

- Huntingford, F.A.; Adams, C.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Kadri, S.; Pottinger, T.G.; Sandøe, P.; Turnbull, J.F. Current issues in fish welfare. J. Fish Biol. 2006, 68, 332–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, H. New approach for disease fish identification using augmented reality and image processing technique. IPASJ 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, S.; Sadoul, B.; Cousin, X.; Bégout, M.L. Spatial distribution and activity patterns as welfare indicators in response to water quality changes in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 226, 104974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, P.J. Fish welfare: Current issues in aquaculture. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, K.; Joshi, P.; Acharya, K.P.; Ramena, G. Emerging technologies revolutionising disease diagnosis and monitoring in aquatic animal health. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubina, N.A.; Lan, H.Y.; Cheng, S.C.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, S.S.; Zhang, K.X.; Lu, H.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.Z. Digital twin-based intelligent fish farming with Artificial Intelligence Internet of Things (AIoT). Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 5, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.W.K. Implementation of artificial intelligence in aquaculture and fisheries: deep learning, machine vision, big data, internet of things, robots and beyond. J. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method/Model | Data Type | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMKDR | image based | feeding behaviour & intensity quantification | [78] |

| YOLO feed | image based | feed intake | [79] |

| Feedforward neural network (FFN) | water surface fluctuations |

feeding behaviour | |

| YOLOv5 | image based | feeding behaviour Dicentrarchus labrax |

[80] |

| MobileViT-SENet | image based | fish density & feeding intensity in outdoor ponds | [68] |

| YOLOv8 mode | image based | fish swimming behaviour and activity degree | [81] |

| Mul-SEResNet50 | multi information | sound and activity degree Oncorhynchus mykiss |

[82] |

| DeformAtt-ViT | image based | swimming behaviour and activity degree largemouth bass |

[83] |

| RCNN | video based | activity degree Ctenopharyngodon idella |

[84] |

| FishFeed methods | video based | fish density and spatial information | [85] |

| CNN | image-based | feeding behaviour classification | [86] |

| BlendMask-VoNetV2 | video based | fish swimming behaviour and activity degree | [87] |

| Audio spectrum swin transformer network | multi information | sound and activity level Oncorhynchus mykiss |

[88] |

| STAN | multi information | swimming and spatial features pompanos |

[89] |

| MMTM | multi information | sound and activity degree Oncorhynchus aguabonita |

[56] |

| LC-GhostNet lightweight network | multi information | Sound and activity degree Oplegnathus punctatus |

[90] |

| MSIF- MobileNetV3 | image based | swimming behaviour and activity degree Oplegnathus punctatus |

[6] |

| Resnet50-LSTM | video based | swimming behaviour, activity degree | [91] |

| 3D ResNet-GloRe | video based | swimming behaviour and activity degree Oncorhynchus mykiss |

[92] |

| MobileNetV2- SENet | image based | swimming behaviour and activity degree Plectropomus leopardus |

[93] |

| Multi-task network | multi information | group activity level Oplegnathus punctatus |

[94] |

| Long term recurrent convolutional network | image based | feeding behaviour grass and crucian carps |

[72] |

| YOLOv4 | image based | water feed detection | [95] |

| CNN | image based | water feed detection | [96] |

| CNN | image based | water feed detection | [97] |

| Customized recurrent neural network | video based | swimming behaviour and activity degree American black bass |

[77] |

| Optical flow neural network | image based | fish swimming behaviour and activity degree | [98] |

| Duel attention network-EfficinetB2 | image based | feeding behaviour |

[99] |

| Optical flow model | optical flow | feeding behaviour recognition | [76] |

| CNN | image based | feeding behaviour tilapia |

[100] |

| CNN | image based | fish recognition / feeding detection | [101] |

| CNN | image based | feeding behaviour detection | [102] |

| Dual-Stream Recurrent Network | video based | spatial and motion information Atlantic salmon |

[74] |

| CNN | image based | feeding behaviuor tilapia |

[103] |

| RNN | sensors | fish growth/environment modeling | [52] |

| Computer vision feeding index | image based | feeding activity assessment | [104] |

| Method/Model | Data Type | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AquaYOLO | image based | fish detection | [109] |

| AMA-Net | video based | appearance & motion Oplegnathus punctatus |

[126] |

| Graph Convolution Networks (GCN) | image based | Swimming/spatial features of Oncorhynchus mykiss |

[127] |

| VGG16 + Active Learning | image based | swimming behaviour Oplegnathus punctatus |

[128] |

| Multi-task network | multi modal | group activity level Oplegnathus punctatus |

[94] |

| CNN |

image based | fish recognition | [9] |

| CNN |

image based | spatial information Tilapia |

[100] |

| LeNet-5 |

image based | swimming behaviour & activity Tilapia |

[108] |

| Recurrent Network |

image based | fish behaviour recognition |

[44] |

| SVM + image texture |

Image based | fish behaviour analysis | [94] |

| Social force model |

Simulation | fish schooling dynamics | [35] |

| Grayscale + edge detection |

image based | fish location & quantity | [45] |

| Image edge detection + threshold segmentation |

image based | behaviour analysis | [129] |

| Image processing methods |

image based | group dispersion & activity index | [130] |

|

Adaptive threshold + edge detection |

image based |

swimming velocity & direction |

[131] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).