Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Collection of Materials

2.2. Determination of Chemical Composition

2.3. Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy

2.4. Determination of Fiber Dimensions

2.5. Determination of Derived Indices of Fibers

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

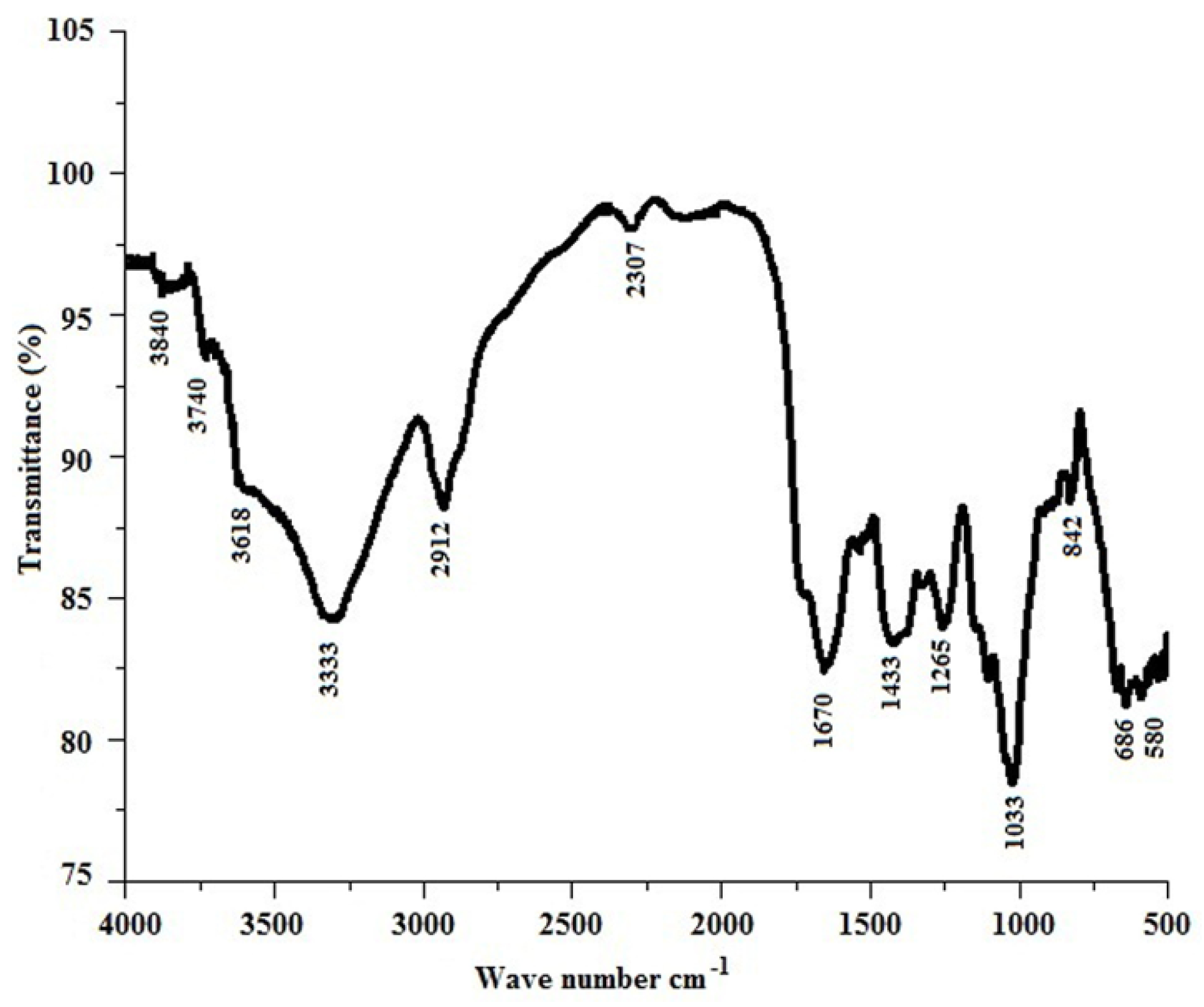

3.2. Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy

3.3. Determination of Fiber Dimensions

3.3.1. Fiber Length

3.3.2. Fiber Diameter

3.3.3. Lumen Width

3.3.4. Fiber Cell Wall Thickness

3.4. Derived Indices of Fibers

3.4.1. Runkel Ratio

3.4.2. Slenderness Ratio

3.4.3. Coefficient of Flexibility

3.4.4. Rigidity Coefficient

3.4.5. Luce’s Shape Factor

3.4.6. Solid’s Shape Factor

4. Conclusions

References

- Dutt, D.; Tyagi, C.H. Comparison of various eucalyptus species for their morphological, chemical, pulp and paper making characteristics. Indian Journal of Chemical Technology 2011, 18, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, P.M.; Sivaram, N.M.; Barik, D. Paper industry wastes and energy generation from wastes. In Energy from Toxic Organic Waste for Heat and Power Generation; Woodhead Publishing; pp. 83–97. [CrossRef]

- Przybysz, K.; Małachowska, E.; Martyniak, D.; Boruszewski, P.; Iłowska, J.; Kalinowska, H.; Przybysz, P. Yield of Pulp, Dimensional Properties of Fibers, and Properties of Paper Produced from Fast Growing Trees and Grasses. BioResources 2018, 13, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonio, F.; Antwi-Boasiako, C. The characteristics of fibres within coppiced and non-coppiced rosewood (Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir.) and their aptness for wood - and paper -based products. Pro Ligno 2017, 13, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.K.; Dutt, D.; Upadhyaya, J.S.; Roy, T.K. Anatomical, morphological, and chemical characterization of Bambusa tulda, Dendrocalamus hamiltonii, Bambusa balcooa, Malocana baccifera, Bambusa arundinacea, and Eucalyptus tereticornis. BioResources 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NagarajaGanesh, B.; Rekha, B.; Kailasanathan, C.; Ganeshan, P.; Mohanavel, V. Sustainable fiber extraction and determination of mechanical and wear properties of Borassus flabellifer sprout fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 6859–6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, N.; Balasubramanian, R. Turning Discarded Agricultural Remnants and Poultry Waste into Usable Hybrid Polymer Matrix Reinforcements: An Experimental Study. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirralho, M.; Flores, D.; Sousa, V.B.; Quilhó, T.; Knapic, S.; Pereira, H. Evaluation on paper making potential of nine Eucalyptus species based on wood anatomical features. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 54, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.F.E.; Abdelazim, Y.A. Effect of growth rate on fiber characteristics of eucalyptus camaldulensis wood of coppice origin grown in White Nile State. Sudan J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Stud. 2015, 3, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima, J.; Yokota, S.; Yoshizawa, N.; Ona, T. Examination of within-tree variations and the heights representing whole-tree values of derived wood properties for quasi-non-destructive breeding of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus globulus as quality pulpwood. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NagarajaGanesh, B.; Rekha, B.; Mohanavel, V.; Ganeshan, P. Exploring the Possibilities of Producing Pulp and Paper from Discarded Lignocellulosic Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NagarajaGanesh, B.; Rekha, B. Morphology and damage mechanism of lignocellulosic fruit fibers reinforced polymer composites: a comparative study. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanobe, V.O.; Sydenstricker, T.H.; Munaro, M.; Amico, S.C. A comprehensive characterization of chemically treated Brazilian sponge-gourds (Luffa cylindrica). Polym. Test. 2005, 24, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querido, V.A.; D’aLmeida, J.R.M.; Silva, F.A. Development and analysis of sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica L.) fiber-reinforced cement composites. BioResources 2019, 14, 9981–9993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NagarajaGanesh, B.; Muralikannan, R. Extraction and characterization of lignocellulosic fibers from Luffa cylindrica fruit. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization 2016, 21, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, B.J.; Buijtenen, J.P.V. Wood variation and wood properties. In Wood Variation; Springer: Berlin, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, G.E. Transverse collapse of wood pulp fibers: Fiber models. In The physics and chemistry of wood pulp fibers (special technical association publication, no. 8) (pp.278–281); Page, D.H., Ed.; Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper industry: New York, United States, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Malan, F.; Gerischer, G. Wood Property Differences in South African Grown Eucalyptus grandis Trees of Different Growth Stress Intensity. Holzforschung 1987, 41, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Langenfeld-Heyser, R.; Finkeldey, R.; Polle, A. Functional anatomy of five endangered tropical timber wood species of the family Dipterocarpaceae. Trees 2008, 23, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifah, K.A.; Osei, L.; Ofosu, S. Suitability of Four Varieties of Cocos Nucifera Husk in Ghana for Pulp and Paper Production. J. Nat. Fibers 2021, 19, 4654–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M. (Ed.) Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites; CRC Press: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhes, J.; Marandi, M.A.B.; Zeinaly, F.; Saraian, A.; Saghaf, T. Tobacco residuals as promising lignocellulosic materials for pulp and paper industry. BioResources 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, A.A.; Hamzeh, Y.; Mirshokraie, S.A.; Molaii, M. Papermaking potential of canola stalks. BioResources 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, N.A.; Oluyege, A.O.; Ajayi, B. Fibre dimension and chemical characterisation of naturally grown Bambusa vulgaris for pulp and paper production. Journal of Bamboo and Rattan 2015, 15, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lukmandaru, G.; Zumaini, U.F.; Soeprijadi, D.; Nugroho, W.D.; Susanto, M. Chemical Properties and Fiber Dimension of Eucalyptus pellita from The 2nd Generation of Progeny Tests in Pelaihari, South Borneo, Indonesia. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2016, 44, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NagarajaGanesh, B.; Muralikannan, R. Physico-chemical, thermal, and flexural characterization of Cocos nucifera fibers. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization 2016, 21, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakifirooz, A.; Kiaei, M.; Sadegh, A.N.; Samariha, A.A. Studies on chemical properties and morphological characteristics of Iranian cultivated kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.): A potential source of fibrous raw material for paper industry in Iran. Research on Crops. 2012, 13, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Sharma, C.L.; Lama, D.D. Anatomical and fibre characteristics of some agro waste materials for pulp and paper making. International Journal of Agricultural Science and Research 2015, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Laftah, W. A.; Rahman, A.W.A. Pulping Process and the Potential of Using Non-Wood Pineapple Leaves Fiber for Pulp and Paper Production: A Review. Journal of Natural Fibers 2016, 13, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Mori, F.; Tonoli, G.; Savastano, H.; Ferrari, D.; Miranda, I. Properties of an Amazonian vegetable fiber as a potential reinforcing material. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 47, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ververis, C.; Georghiou, K.; Christodoulakis, N.; Santas, P.; Santas, R. Fiber dimensions, lignin and cellulose content of various plant materials and their suitability for paper production. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2004, 19, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhong, X.; Sun, R.; Lu, Q. Anatomy, ultrastructure and lignin distribution in cell wall of Caragana Korshinskii. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2006, 24, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, K.B.; Antwi-Boasiako, C.; Frimpong-Mensah, K. Physical and mechanical properties of Klainedoxa gabonensis with engineering potential. J. For. Res. 2016, 28, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifah, K.A.; Adom, A.N.A.; Ofosu, S. The Morphological and Pulping Indices of Bagasse, Elephant Grass (Leaves and Stalk), and Silk Cotton Fibers for Paper Production. J. Nat. Fibers 2021, 19, 9782–9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangaard, F.F. Contributions of hardwood fibres to the properties of kraft pulps. Tappi 1962, 45, 548–556. [Google Scholar]

- Sangumbe, L.M.V.; Pereira, M.; Carrillo, I.; Mendonça, R.T. An exploratory evaluation of the pulpability of Brachystegia spiciformis and Pericopsis angolensis from the angolan miombo woodlands. Maderas-Cienc Tecnol 2018, 20, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, J.; Yokota, S.; Yoshizawa, N.; Ona, T. Examination of within-tree variations and the heights representing whole-tree values of derived wood properties for quasi-non-destructive breeding of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus globulus as quality pulpwood. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifah, K.A.; Adjei-Mensah, E. Anatomical and chemical characterization of Alstonia boonei for pulp and paper production. Les/Wood 2021, 70, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu, S.; Boadu, K.B.; Afrifah, K.A. Suitability of Chrysophyllum albidum from moist semi-deciduous forest in Ghana as a raw material for manufacturing paper-based products. J. Sustain. For. 2019, 39, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, S.; Naithani, S.; Thapliyal, B.P.; Tyagi, S.; Bist, M. Effect of morphological characteristics of indegeneous fibers (E. tereticornis and S. officinarum) and their impact on paper properties. Ippta Journal 2017, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwadare, A.O.; Sotannde, O.A. The relationship between fiber characteristics and pulp-sheet properties of Leucaena leucocephala (Lam. ) De Wit. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 2007, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rekha, B.; NagarajaGanesh, B. X-ray Diffraction: An Efficient Method to Determine Microfibrillar Angle of Dry and Matured Cellulosic Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 19, 3689–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fiber name | Holocellulose | Lignin | Ash content | References |

| % | % | % | ||

| Eucalyptus grandis | 59.8 | 29.6 | 2.87 | [1] |

| Eucalyptus alba | 60.3 | 27.9 | 0.36 | [6] |

| Eucalyptus europhyllia | 64.2 | 26.5 | 0.98 | [6] |

| Reed | 77.9 | 18.7 | 3.9 | [1] |

| Paulownia | 75.4 | 20.5 | 0.21 | [21] |

| Canola stalk | 73.6 | 17.3 | 8.2 | [21] |

| Bamboosa vulgaris | 79.01 | 40.41 | 29.2 | [23] |

| Eucalyptus pellita | 71.07 | 25.5 | - | [24] |

| E. tereticornis | 66.5 | 28.2 | 1.12 | [6] |

| Luffa cylindrica | 82.4 | 11.2 | 0.63 | Current work |

| S.No | Fiber length | Fiber Diameter | Lumen diameter | Cell Wall Thickness |

| μm | μm | μm | μm | |

| 1 | 956 | 15.2 | 9.3 | 2.9 |

| 2 | 984 | 16.2 | 9.5 | 3.4 |

| 3 | 964 | 14.7 | 10.3 | 2.3 |

| 4 | 1022 | 16.4 | 12.6 | 2.2 |

| 5 | 1014 | 16.2 | 10.2 | 3.2 |

| 6 | 1036 | 17.4 | 10.3 | 3.6 |

| 7 | 1012 | 18.6 | 14.2 | 2.4 |

| 8 | 956 | 15.3 | 11.1 | 2.3 |

| 9 | 976 | 15.8 | 8.9 | 3.4 |

| 10 | 932 | 16.8 | 10.8 | 3.2 |

| 11 | 912 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 2.1 |

| 12 | 948 | 14.4 | 9.4 | 2.5 |

| 13 | 914 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 2.2 |

| 14 | 1042 | 18.8 | 10.5 | 4.2 |

| 15 | 968 | 15.8 | 9.6 | 3.3 |

| 16 | 992 | 15.6 | 8.6 | 3.6 |

| 17 | 1068 | 17.8 | 12.4 | 2.6 |

| 18 | 1060 | 16.8 | 8.4 | 4.5 |

| 19 | 1048 | 17.2 | 10 | 3.7 |

| 20 | 1108 | 18.4 | 10.2 | 4.4 |

| Mean | 995.6 | 16.31 | 10.39 | 3.1 |

| Median | 988 | 16.2 | 10.25 | 3.2 |

| Mode | 956 | 16.2 | 10.3 | 3.4 |

| Min | 912 | 14.2 | 8.4 | 2.1 |

| Max | 1108 | 18.8 | 14.2 | 4.5 |

| Range | 196 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 2.4 |

| STD | 53.92 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 0.76 |

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Fiber name | Runkel ratio | Slenderness ratio% | Coefficient of Flexibility | Rigidity Ratio | Luce shape factor | Solids Factor μm³ | References |

| Chrysophyllum albidum | 0.55 | 46.9 | 0.64 | 0.177 | 0.41 | 346 | [38] |

| Saccharum officinarum | 2.479 | 69.77 | 29.12 | 0.722 | 84 | 634 | [39] |

| Eucalyptus tereticornis | 1.047 | 39.07 | 39.73 | 0.416 | 0.727 | 256 | [40] |

| Leucaena leucocephala | 0.59 | - | 0.63 | - | 0.41 | - | [41] |

| Biden spilosa | 0.46 | 47.33 | 69.01 | - | 0.33 | - | [1] |

| Eupatorium odoratum | 0.52 | 42.3 | 65.81 | - | 0.50 | - | [1] |

| Beema bamboo | 0.69-0.8 | 78.38-101.48 | 56.32-60.39 | - | - | - | [32] |

| Oxythenantera abyssinica | 0.6-0.76 | 82.37-93.92 | 59.75-60.66 | - | - | - | [32] |

| Setaria glauca | 0.57 | 173.15 | 65.57 | 0.35 | 0.4 | 0.86 | [27] |

| Solanum torvum | 0.25 | 24.62 | 80.30 | - | 0.19 | - | [27] |

| Tobacco stalk | 1.16 | 50.59 | 63.26 | - | - | - | [21] |

| Pinus kesiya | 0.22 | 49.04 | 81.74 | - | 0.19 | - | [27] |

| Luffa cylindrica | 0.5977 | 61.04 | 0.637 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 157.36 | Current work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).