Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Groups

2.2. Blood Sampling and Measurements of Progesterone and Endocannabinoids

2.4. Uterine Tissue Sampling and Tissue Processing

2.5. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.6. Immunohistochemical Staining

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Mean Ages and Body Weights of the Animals

3.2. Histomorphology of the Uterine Tissues and Microbiological Identification

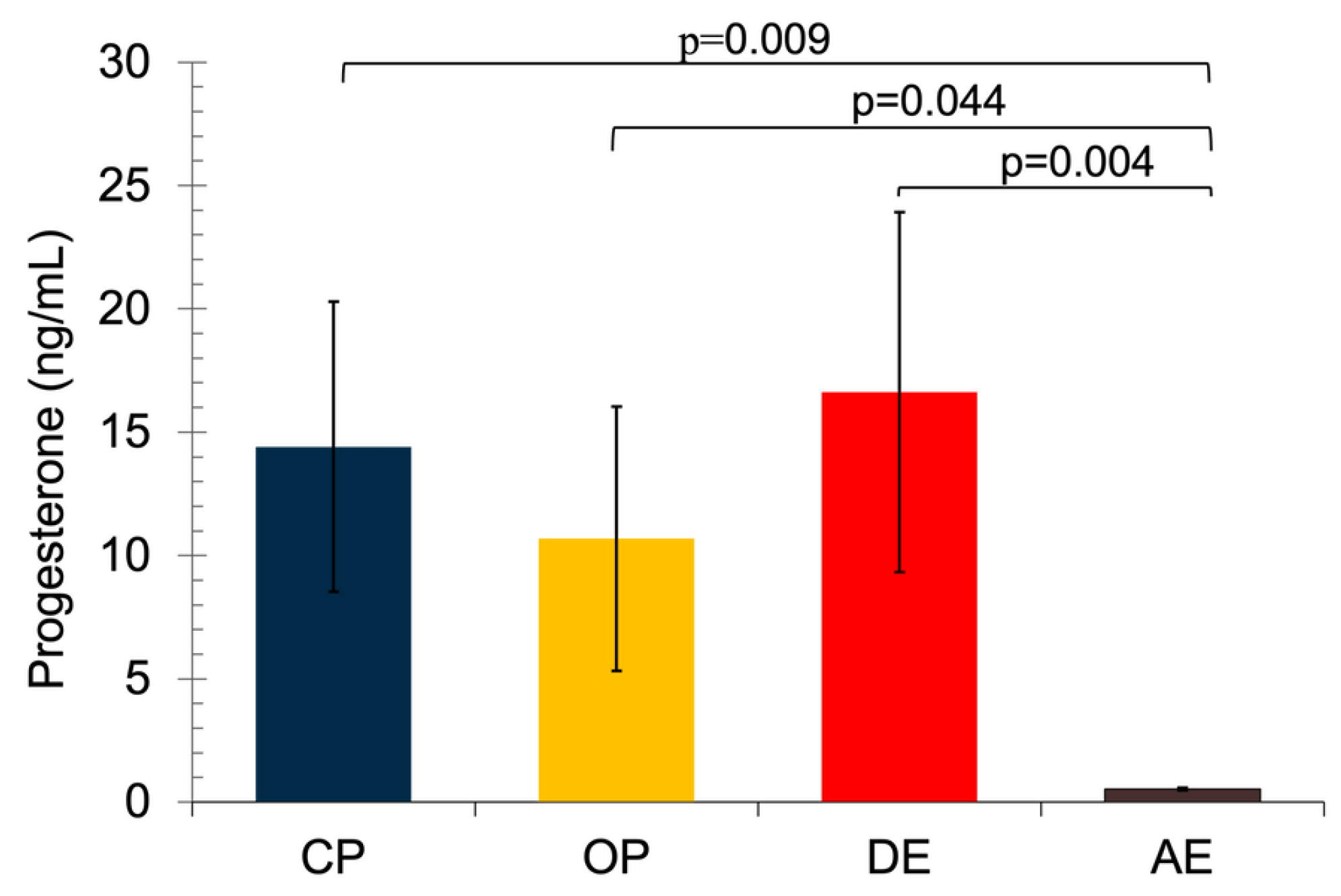

3.3. Serum Progesterone Concentrations

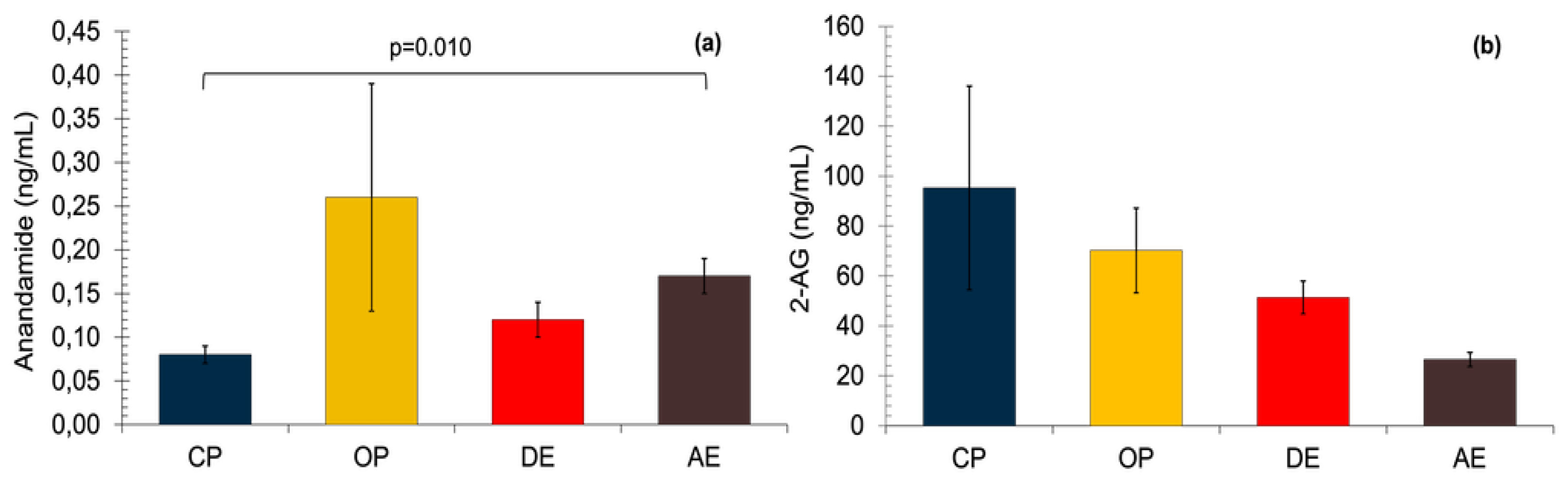

3.4. Serum Anandamide and 2-AG Concentrations

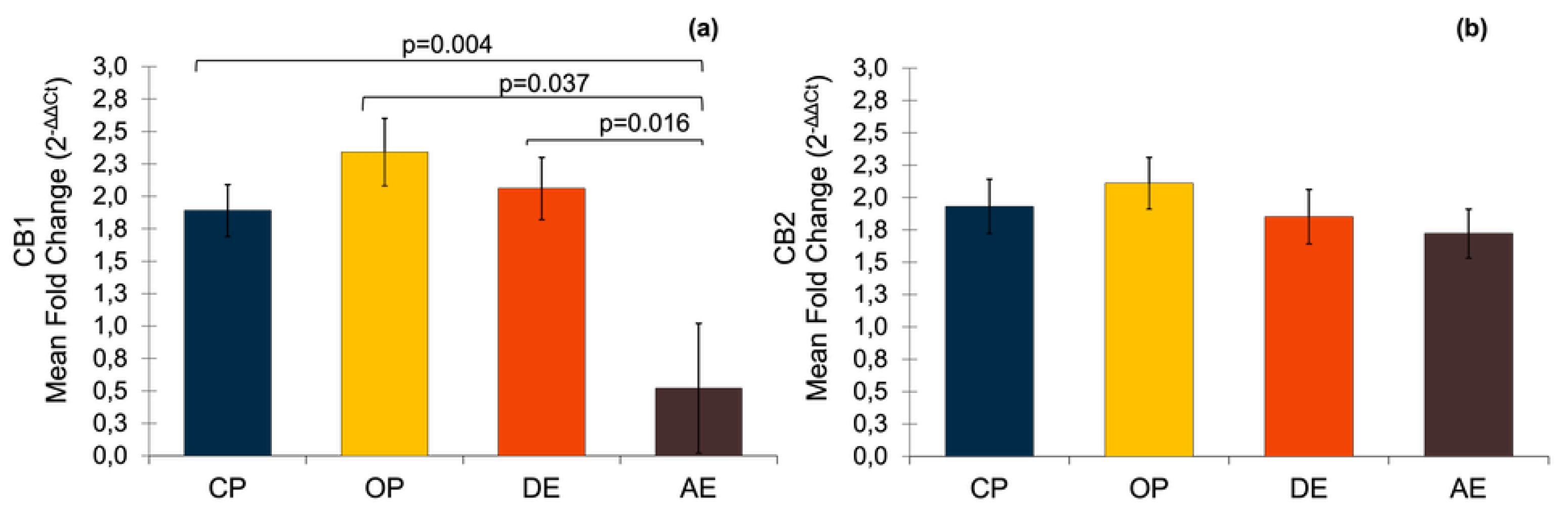

3.5. Gene Expressions of CB1 and CB2

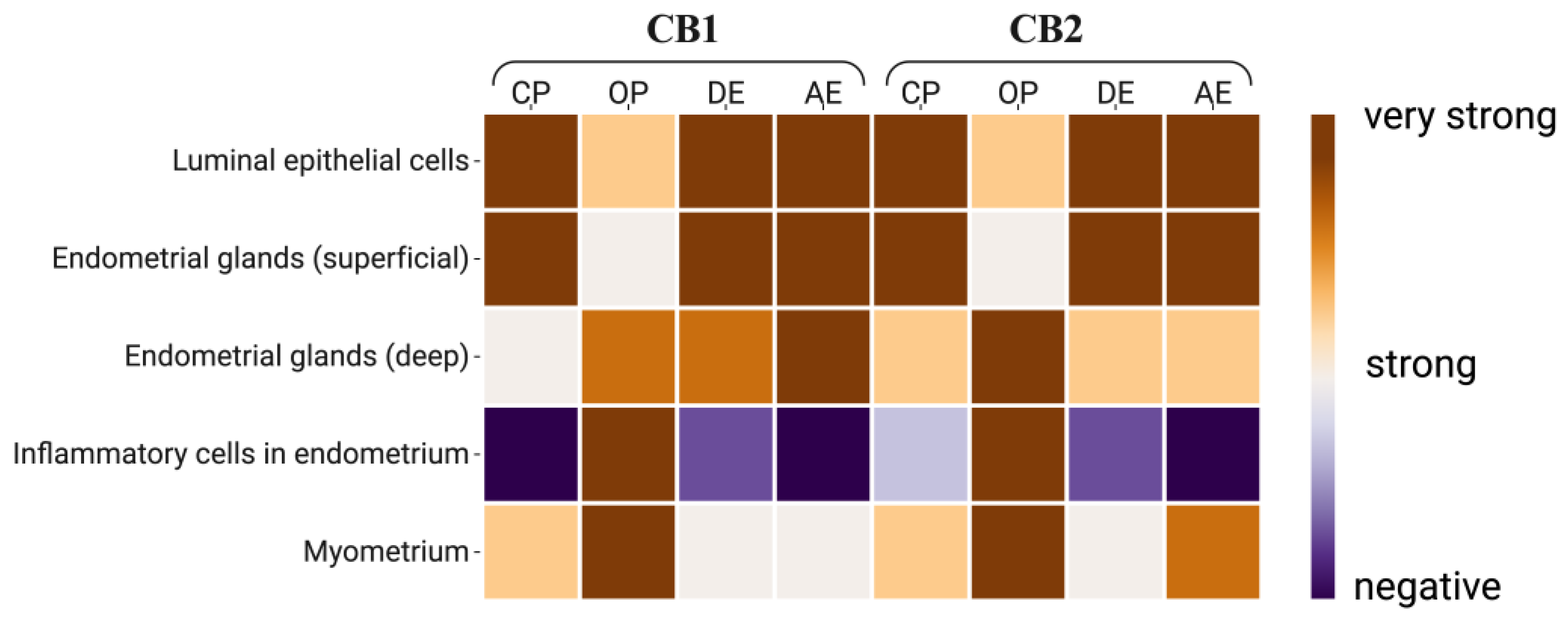

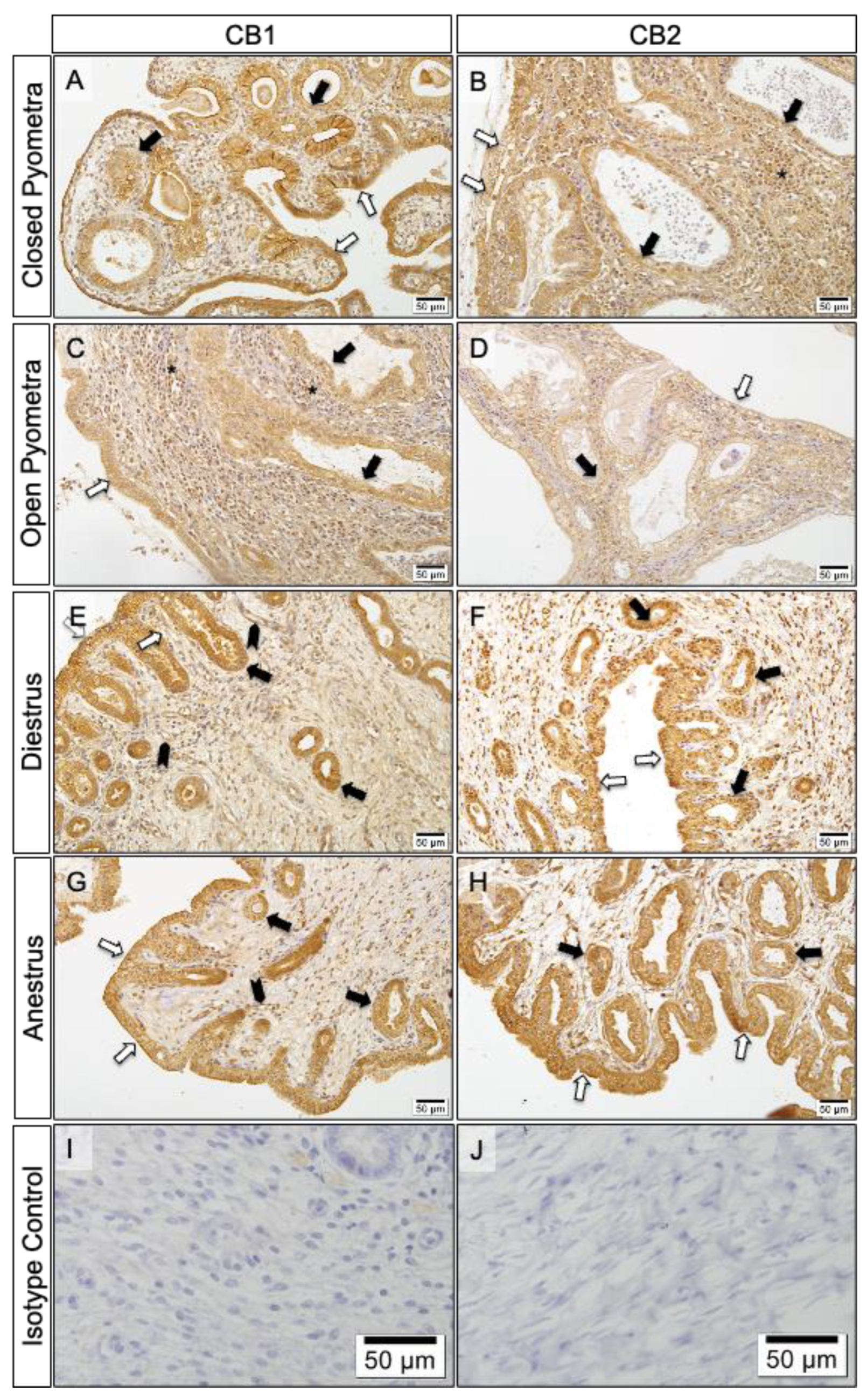

3.6. Localization of CB1 and CB2

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Hormonal Status

4.2. Effect of Age

4.3. Inflammatory Status

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maccarrone, M. Endocannabinoids: friends and foes of reproduction. Prog. Lipid Res. 2009, 48, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, A.C.; Barth, F.; Bonner, T.I.; Cabral, G.; Casellas, P.; Devane, W.A.; Pertwee, R.G. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002, 54, 161–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Talatini, M.R.; Taylor, A.H.; Elson, J.C.; Brown, L.; Davidson, A.C.; Konje, J.C. Localisation and function of the endocannabinoid system in the human ovary. PLoS One 2009, 4, e4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reggio, P.H. Endocannabinoid binding to the cannabinoid receptors: what is known and what remains unknown. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, M.; Di Marzo, V.; Gertsch, J.; Grether, U.; Howlett, A.C.; Hua, T.; van der Stelt, M. Goods and bads of the endocannabinoid system as a therapeutic target: Lessons learned after 30 years. Pharmacol. Rev. 2023, 75, 885–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, F.; Wolfson, M.L.; Valchi, P.; Aisemberg, J.; Franchi, A.M. Endocannabinoid system and pregnancy. Reproduction 2016, 152, R191–R200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, H.N.; Vaswani, K.; Holland, O.; Koh, Y.Q.; Almughlliq, F.B.; Reed, S.; Mitchell, M.D. Altered productions of prostaglandins and prostamides by human amnion in response to infectious and inflammatory stimuli identified by multiplex mass spectrometry. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2020, 154, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammon, C.M.; Freeman, G.M.; Xie, W.; Petersen, S.L.; Wetsel, W.C. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by cannabinoids. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, A.W.; Phillips, J.A. III; Kane, N.; Lourenco, P.C.; McDonald, S.E.; Williams, A.R.; Critchley, H.O. CB1 expression is attenuated in Fallopian tube and decidua of women with ectopic pregnancy. PLoS One 2008, 3, e3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorticati, C.; Fernández-Solari, J.; De Laurentiis, A.; Mohn, C.; Prestifilippo, J.P.; Lasaga, M.; Rettori, V. The inhibitory effect of anandamide on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone secretion is reversed by estrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 11891–11896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Talatini, M.R.; Taylor, A.H.; Konje, J.C. The relationship between plasma levels of the endocannabinoid, anandamide, sex steroids, and gonadotrophins during the menstrual cycle. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 1989–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, M.; Bari, M.; Battista, N.; Finazzi-Agrò, A. Estrogen stimulates arachidonoylethanolamide release from human endothelial cells and platelet activation. The J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 23954–23960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Takahashi, T.; Kingsley, P.J.; Marnett, L.J.; Das, S.K.; Cravatt, B.F.; Dey, S.K. Fatty acid amide hydrolase deficiency limits early pregnancy events. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 2122–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.M.; Cioffi, R.; Viganò, P.; Candiani, M.; Verde, R.; Piscitelli, F.; Panina-Bordignon, P. Elevated systemic levels of endocannabinoids and related mediators across the menstrual cycle in women with endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingegowda, H.; Zutautas, K.B.; Wei, Y.; Yolmo, P.; Sisnett, D.J.; McCallion, A.; Tayade, C. Endocannabinoids and their receptors modulate endometriosis pathogenesis and immune response. eLife 2024, 13, RP96523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.; Kocieda, V.P.; Yen, J.H.; Tuma, R.F.; Ganea, D. Signaling through cannabinoid receptor 2 suppresses murine dendritic cell migration by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. Blood 2012, 120, 3741–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.; Galic, M.A.; Wang, A.; Chambers, A.P.; McCafferty, D.M.; McKay, D.M.; Pittman, Q.J. Cannabinoid 1 receptors are critical for the innate immune response to TLR4 stimulation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R224–R231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šahinović, I.; Mandić, S.; Mihić, D.; Duvnjak, M.; Loinjak, D.; Sabadi, D.; Šerić, V. Endocannabinoids, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, as prognostic markers of sepsis outcome and complications. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023, 8, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, H.; Ferraro, M.J. Exploring the versatile roles of the endocannabinoid system and phytocannabinoids in modulating bacterial infections. Infect. Immun. 2024, 92, e00020-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, K.L. Interaction between cannabinoid system and toll-like receptors controls inflammation. Mediators of Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.; Leitão, S.; Henriques, S.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Hoffmann, B.; Ferreira-Dias, G.; Mateus, L. Gene transcription of TLR2, TLR4, LPS ligands and prostaglandin synthesis enzymes are up-regulated in canine uteri with cystic endometrial hyperplasia–pyometra complex. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010, 84, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotimanukul, S.; Sirivaidyapong, S. Differential expression of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in healthy and infected canine endometrium. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, R.J.; Adams, L.F.; Mitchell, M.D. Prostaglandin synthases: recent developments and a novel hypothesis. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2004, 70, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariani, M.V.; Domínguez Rubio, A.P.; Cella, M.; Burdet, J.; Franchi, A.M.; Aisemberg, J. Role for the endocannabinoid system in the mechanisms involved in the LPS-induced preterm labor. Reproduction 2015, 150, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Mestre, L.; Loría, F.; Spagnolo, A.; Docagne, F.; Guaza, C. Anandamide enhances IL-10 production in activated microglia by targeting CB2 receptors: Roles of ERK1/2, JNK, and NF-κB. Glia 2010, 58, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol protects neurons by limiting COX-2 elevation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 22601–22611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, R.; Rönnberg, E.; Pejler, G. Canine uterine bacterial infection induces upregulation of proteolysis-related genes and downregulation of homeobox and zinc finger factors. PLoS One 2009, 4, e8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, G.B.; Casal, M.L. A review of pyometra in small animal medicine: incidence, pathophysiology, clinical diagnosis, and medical management. Clin. Theriogenol. 2018, 10, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorwald, F.A.; Marchi, F.A.; Villacis, R.A.R.; Alves, C.E.F.; Toniollo, G.H.; Amorim, R.L.; Rogatto, S.R. Molecular expression profile reveals potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in canine endometrial lesions. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.F. Bases da Patologia em Veterinária. In Sistema Reprodutivo da Fêmea, 4th ed.; McGavin, M.D., Zachary, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; pp. 1263–1315. [Google Scholar]

- De Bosschere, H.; Ducatelle, R.; Vermeirsch, H.; Van Den Broeck, W.; Coryn, M. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch: Should the two entities be disconnected? Theriogenology 2001, 55, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.C.; Nelson, R.W. Ovarian cycle and vaginal cytology. In Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction; Feldman, E.C., Nelson, R.W., Eds.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 752–774. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, K.; Funahashi, H. Histological characteristics of canine deciduoma induced by intrauterine inoculation of E. coli suspension. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1999, 61, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlafer, D.H. Diseases of the canine uterus. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concannon, P.W. Endocrinologic control of normal canine ovarian function. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, P.Y.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Lee, C.S.; Wright, P.J. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the endometrium of bitches. Reproduction 2002, 123, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campora, L.; Miragliotta, V.; Ricci, E.; Cristino, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Albanese, F.; Abramo, F. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 and 2 expression in the skin of healthy dogs and dogs with atopic dermatitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 73, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiazzo, G.; Giancola, F.; Stanzani, A.; Fracassi, F.; Bernardini, C.; Forni, M.; Chiocchetti, R. Localization of cannabinoid receptors CB1, CB2, GPR55, and PPARα in the canine gastrointestinal tract. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 150, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercati, F.; Dall’Aglio, C.; Pascucci, L.; Boiti, C.; Ceccarelli, P. Identification of cannabinoid type 1 receptor in dog hair follicles. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Aglio, C.; Mercati, F.; Pascucci, L.; Boiti, C.; Pedini, V.; Ceccarelli, P. Immunohistochemical localization of CB1 receptor in canine salivary glands. Vet. Res. Commun. 2010, 34, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundt-Revilla, J.; Kegler, K.; Baumgärtner, W.; Tipold, A. Spatial distribution of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) in normal canine central and peripheral nervous system. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, M.P.; Beceriklisoy, H.B.; Pfarrer, C.; Aslan, S.; Kindahl, H.; Kücükaslan, I.; Hoffmann, B. Canine placenta: a source of prepartal prostaglandins during normal and antiprogestin-induced parturition. Reproduction 2010, 139, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavreus-Evers, A.; Koraen, L.; Scott, J.E.; Zhang, P.; Westlund, P. Distribution of cyclooxygenase-1, cyclooxygenase-2, and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in the luteal phase human endometrium and ovary. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 83, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, G.A.L.; Miziara, R.H.; Angrimani, D.S.R.; Papa, P.C.; Cogliati, B.; Vannucchi, C.I. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia–pyometra syndrome in bitches: identification of hemodynamic, inflammatory, and cell proliferation changes. Biol. Reprod. 2017, 96, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osteen, K.G.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Eisenberg, E. Reduced progesterone action during endometrial maturation: a potential risk factor for the development of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 83, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penell, J.C.; Morgan, D.M.; Watson, P.; Carmichael, S.; Adams, V.J. Body weight at 10 years of age and change in body composition between 8 and 10 years of age were related to survival in a longitudinal study of 39 Labrador retriever dogs. Acta Vet. Scand. 2019, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, J.; Fonseca, B.M.; Teixeira, N.; Correia-da-Silva, G. The fundamental role of the endocannabinoid system in endometrium and placenta: implications in pathophysiological aspects of uterine and pregnancy disorders. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnu, V.P. Efficacy of medical management and surgical trans-cervical catheterisation for canine cystic endometrial hyperplasia. Ph.D. Thesis, College of Veterinary and Animal Science, Mannuthy, 2016. Available online: http://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/5810110584 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Taylor, A.H.; Abbas, M.S.; Habiba, M.A.; Konje, J.C. Histomorphometric evaluation of cannabinoid receptor and anandamide modulating enzyme expression in the human endometrium through the menstrual cycle. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 133, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Mayne, L.; Khalil, A.; Baartz, D.; Eriksson, L.; Mortlock, S.A.; Amoako, A.A. The role of the endocannabinoid system in aetiopathogenesis of endometriosis: A potential therapeutic target. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 244, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resuehr, D.; Glore, D.R.; Taylor, H.S.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Osteen, K.G. Progesterone-dependent regulation of endometrial cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1-R) expression is disrupted in women with endometriosis and in isolated stromal cells exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazeid, O.; Eylem, C.C.; Reçber, T.; Yalçın, F.N.; Kır, S.; Nemutlu, E. An LC-ESI-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of pronuciferine and roemerine in some Papaver species. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1096, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, C.; Mattsson, J.; Stickel, F.; Dufour, J.F.; Brenneisen, R. Determination of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: analytical and preanalytical challenges and pitfalls. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2018, 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, B.M.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Taylor, A.H.; Lam, P.M.W.; Marczylo, T.H.; Bell, S.C.; Teixeira, N.A. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and metabolizing enzymes during rat fetoplacental development: a role in uterine remodelling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, H.C.; Dhakal, P.; Behura, S.K.; Schust, D.J.; Spencer, T.E. Self-renewing endometrial epithelial organoids of the human uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 23132–23142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares Pereira, M.; Kazemian, A.; Rehrauer, H.; Kowalewski, M.P. Transcriptomic profiling of canine decidualization and effects of antigestagens on decidualized dog uterine stromal cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21890–10.1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, K. Induction of canine deciduoma in some reproductive stages with the different conditions of corpora lutea. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1997, 59, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.M.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Almada, M.; Costa, M.A.; Teixeira, N.A. The endocannabinoid system in the postimplantation period: a role during decidualization and placentation. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 510540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.M.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Taylor, A.H.; Konje, J.C.; Bell, S.C.; Teixeira, N.A. Spatio-temporal expression patterns of anandamide-binding receptors in rat implantation sites: evidence for a role of the endocannabinoid system during the period of placental development. Reprod. Biol. Endocrin. 2009, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.H.; Finney, M.; Lam, P.M.; Konje, J.C. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system in viable and non-viable first trimester pregnancies by pregnancy-related hormones. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, D.F. Commentary: Paying a price for plasticity—what the endometrium has to do with it! J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, D.; Besana, A.; Vigano, P.; Dalino, P.; Vignali, M.; Melandri, M.; Di Blasio, A.M. Endocannabinoid system regulates migration of endometrial stromal cells via cannabinoid receptor 1 through the activation of PI3K and ERK1/2 pathways. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 2588–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojiljković, A.; Gaschen, V.; Forterre, F.; Rytz, U.; Stoffel, M.H.; Bluteau, J. Novel immortalization approach defers senescence of cultured canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. GeroScience 2022, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesaris, V.; Grolli, S.; Bresciani, C.; Conti, V.; Basini, G.; Parmigiani, E.; Bigliardi, E. Isolation, proliferation and characterization of endometrial canine stem cells. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.S.; Dyer, N.P.; Murakami, K.; Hou Lee, Y.; Chan, Y.W.; Grimaldi, G.; Brosens, J.J. Loss of endometrial plasticity in recurrent pregnancy loss. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstegen, J.; Dhaliwal, G.; Verstegen-Onclin, K. Mucometra, cystic endometrial hyperplasia, and pyometra in the bitch: advances in treatment and assessment of future reproductive success. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Di Nisio, V.; Chiominto, A.; Cecconi, S.; Maccarrone, M. Endocannabinoid system components of the female mouse reproductive tract are modulated during reproductive aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.I.; Vercelli, C.; Schiariti, V.; Davio, C.; Correa, F.; Franchi, A.M. Heparin exerts anti-apoptotic effects on uterine explants by targeting the endocannabinoid system. Apoptosis 2016, 21, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, B.; Borrelli, F.; Fasolino, I.; Capasso, R.; Piscitelli, F.; Cascio, M.G.; Izzo, A.A. The cannabinoid TRPA1 agonist cannabichromene inhibits nitric oxide production in macrophages and ameliorates murine colitis. Br J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.P.; Yuan, Q.H.; Zhang, B.; Yang, L.; He, Q.W.; Chen, K.; Zhan, J. Cannabinoid receptor 2 activation alleviates septic lung injury by promoting autophagy via inhibition of inflammatory mediator release. Cell. Signal. 2020, 69, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanikawa, T.; Kitamura, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Yokogawa, T.; Inoue, Y. Curcumae Longae Rhizoma and Saussureae Radix inhibit nitric oxide production and cannabinoid receptor 2 down-regulation. In Vivo 2022, 36, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Shi, R.; Kang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Miao, H. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates cannabinoid receptor 2-dependent macrophage activation and cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Akira, S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 2005, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allhorn, S.; Böing, C.; Koch, A.A.; Kimmig, R.; Gashaw, I. TLR3 and TLR4 expression in healthy and diseased human endometrium. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2008, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, P.Y.; Lee, C.S.; Wright, P.J. Degeneration and apoptosis of endometrial cells in the bitch. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1545–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, T.; Osuga, Y.; Hamasaki, K.; Hirota, Y.; Nose, E.; Morimoto, C.; Taketani, Y. Expression of toll-like receptors 2, 3, 4, and 9 genes in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 74, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freundt-Revilla, J.; Heinrich, F.; Zoerner, A.; Gesell, F.; Beyerbach, M.; Shamir, M.; Tipold, A. The endocannabinoid system in canine steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis and intraspinal spirocercosis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0187197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Rakotoarivelo, V.; Di Marzo, V.; Flamand, N. Expression and functions of the CB2 receptor in human leukocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 826400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M.A.; Payan-Carreira, R. Resident macrophages and lymphocytes in the canine endometrium. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2015, 50, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghetti, L. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 63, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, A.A. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors: Implications for regulating inflammatory and immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2002, 23, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Leitao, S.; Ferreira-Dias, G.; Lopes da Costa, L.; Mateus, L. Prostaglandin synthesis genes are differentially transcripted in normal and pyometra endometria of bitches. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleš, J.; Horvatić, A.; Guillemin, N.; Ferreira, R.F.; Mischke, R.; Mrljak, V.; Eckersall, P.D. The plasma proteome and the acute phase protein response in canine pyometra. J. Proteomics 2020, 223, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, R.; Kindahl, H.; Fransson, B.A.; Bergström, A.; Holst, B.S.; Lagerstedt, A.S. Differentiation between pyometra and cystic endometrial hyperplasia/mucometra in bitches by prostaglandin F2α metabolite analysis. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Watkins, B.A. Cannabinoid receptor antagonists and fatty acids alter endocannabinoid system gene expression and COX activity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennedy, M.C.; Friel, A.M.; Houlihan, D.D.; Broderick, V.M.; Smith, T.; Morrison, J.J. Cannabinoids and the human uterus during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, E.; Orlando, P.; Finizio, S.; Rossi, A.; Buono, L.; Iannotti, F.A.; Borrelli, F. Role of the endocannabinoid system in the control of mouse myometrium contractility during the menstrual cycle. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 124, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.L.; Gangula, P.R.; Fang, L.; Yallampalli, C. Differential expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 proteins in rat uterus and cervix during the estrous cycle, pregnancy, labor and in myometrial cells. Prostaglandins 1996, 52, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, B.; FitzGerald, G.A. Cyclooxygenases and prostaglandins: shaping up the immune response. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002, 2, 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, C.A.; Aisemberg, J.; Billi, S.; Cervini, M.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Farina, M.; Franchi, A.M. Anandamide regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthesis and tissue damage in the murine uterus. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2009, 18, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Bu, S.; Nikfarjam, S.; Rasheed, B.; Michels, D.C.; Singh, A.; Singh, K.K. Loss of fatty acid binding protein 3 ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmes, M.W.; Kaczocha, M.; Berger, W.T.; Leung, K.; Ralph, B.P.; Wang, L.; Deutsch, D.G. Fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are intracellular carriers for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8711–8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer sequence | Product length (bp) | Accession numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNR1 | F: TCCTGGGGAGCGTCATATTT | 99 | AY011618.1 |

| R: TGACCCCACCCAGTTTGAAA | |||

| CNR2 | F: TCCTGGCCAGTGTGATCTTT | 119 | NM_001284480.1 |

| R: AGAGGCTGTGAAGGTCATGG | |||

| KDM4A | F: TCACAGAGAAGGAAGTTAAG | 82 | XM_005629107 |

| R: TCACAGAGAAGGAAGTTAAG | |||

| PTK2 | F: ACCTGGCTGACTTCAATC | 85 | XM_005627993 |

| R: ATCTTCAACTGTAGCATTCCT | |||

| EIF4H | F: TAAGGTCTCAGCAATTAC | 101 | XM_014114129 |

| R: TAAGGTCTCAGCAATTAC |

| Antibody | Reference (Company) |

Biological source | Antibody Dilution |

Antibody Incubtion |

Epitope Revelation (DAB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNR1/CB1 | bs-1683R (Bioss, Woburn, USA) | Rabbit (Polyclonal) |

1:200 | Overnight (17 h), 4°C |

Thermo Fisher Scientific Lab Vision Corporation |

| CNR2/CB2 | LS-A34-50 (Life Span, Lynnwood, USA) | ||||

|

Isotype control |

IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA |

Rabbit | Same protein concentration as primary antibody | - | - |

| Groups | n | Ages (year) |

Body weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP | 7 | 8.1 ± 1.1a | 18.4 ± 1.2a |

| OP | 7 | 10.0 ± 1.0a | 15.5 ± 0.1a |

| DE | 7 | 1.8 ± 0.1b | 10.1 ± 0.9b |

| AE | 7 | 1.5 ± 0.2b | 11.2 ± 1.0b |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).