Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

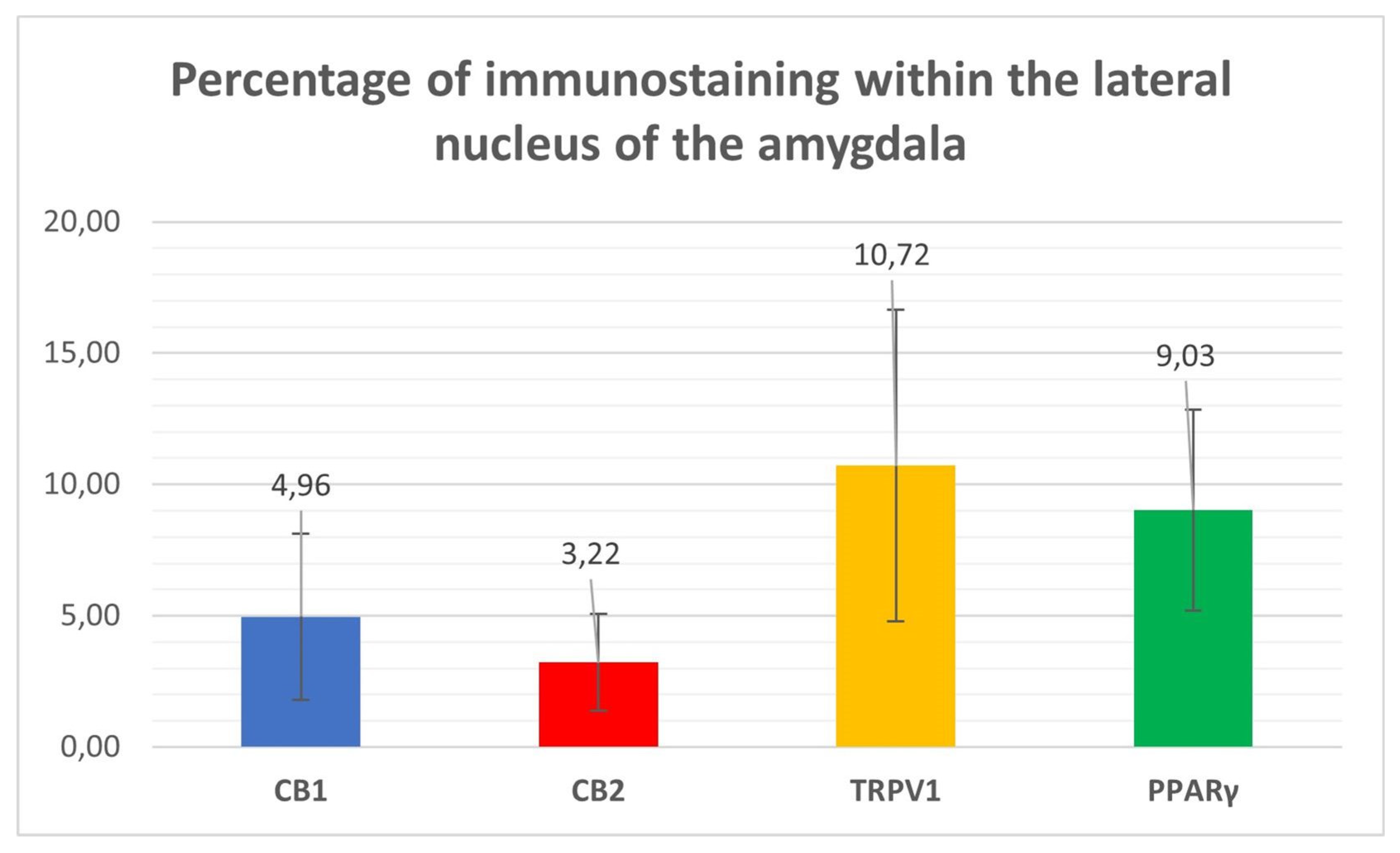

2. Results

2.1. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) for Cnr1, Cnr2, TRPV1, and PPARgamma

2.2. Immunofluorescence

2.2.1. CB1R

2.2.2. CB2R

2.2.3. TRPV1

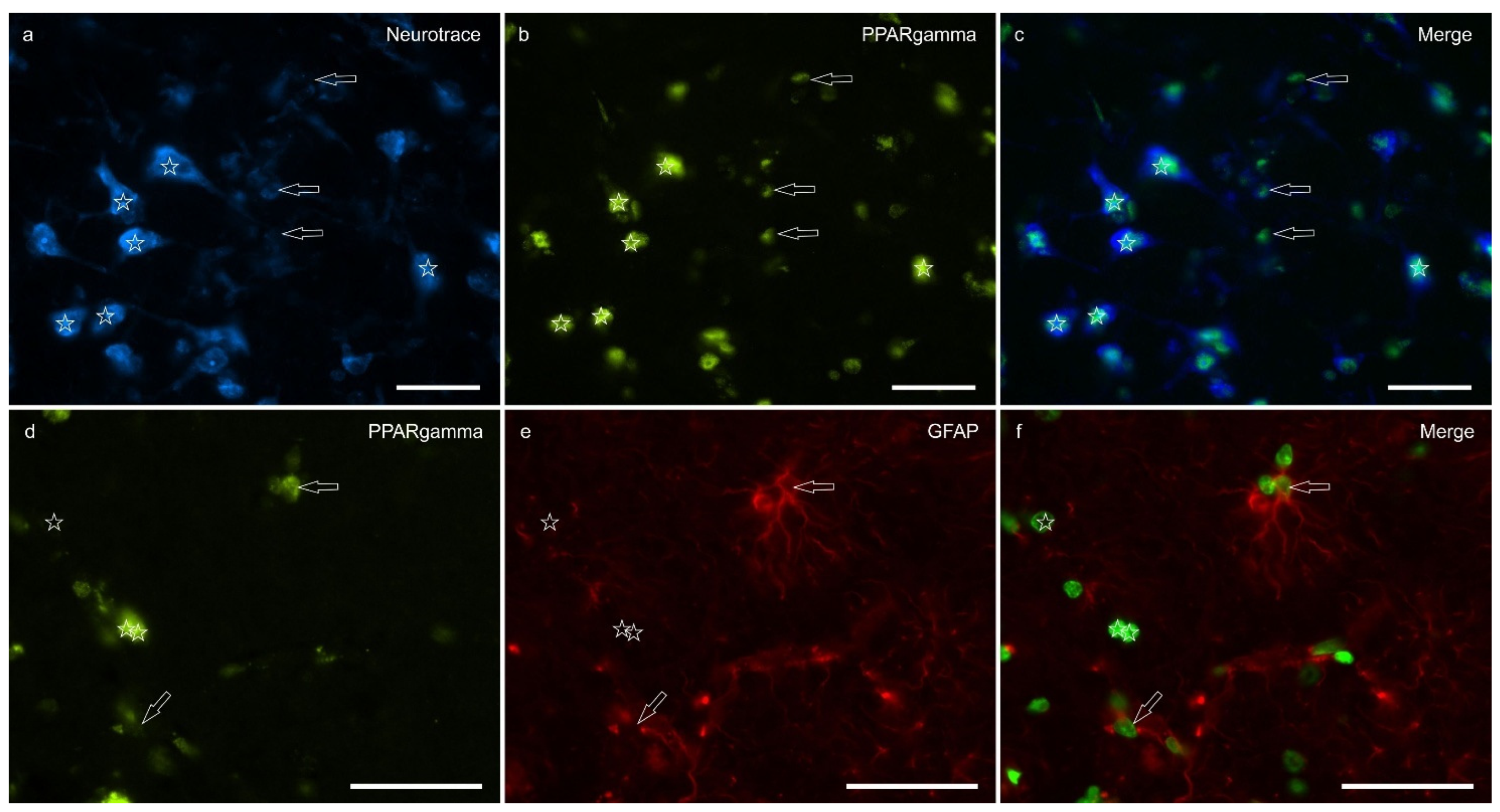

2.2.4. PPARɣ

3. Discussion

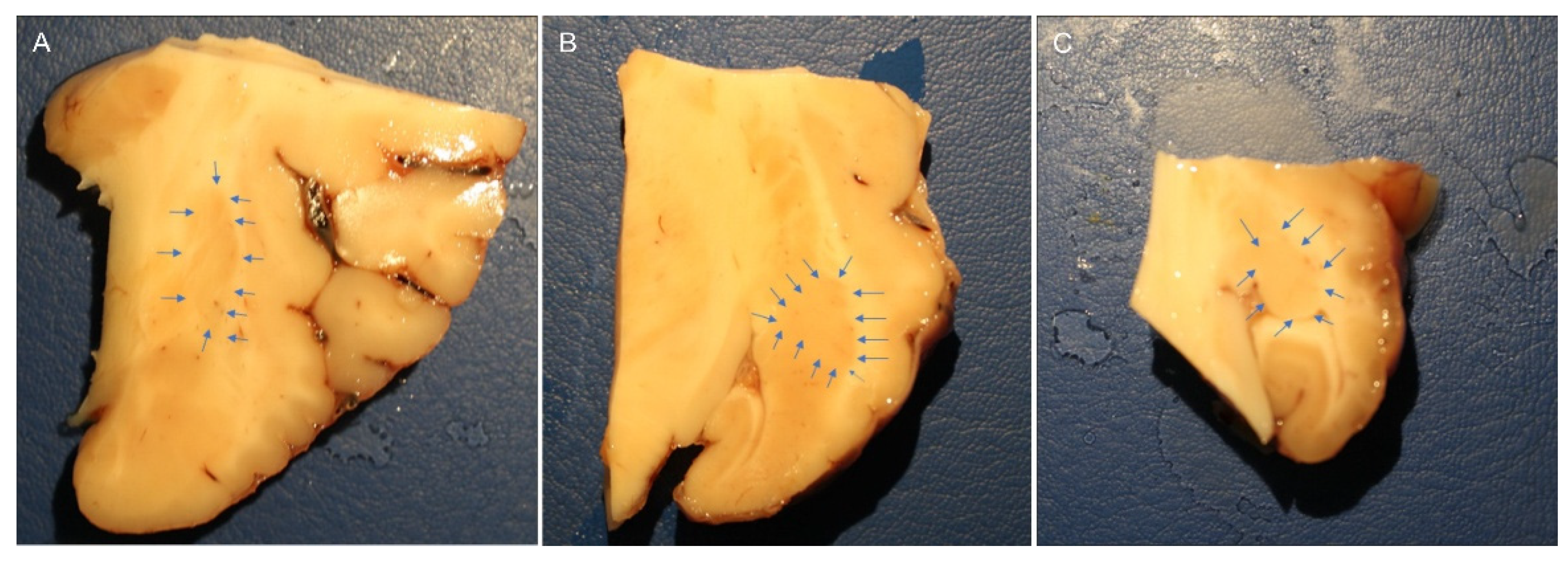

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real Time PCR (RT- PCR) for Cnr1, Cnr2, PPARγ and TRPV1

4.2. Immunofluorescence

4.3. Specificity of the Antibodies

4.4. Fluorescence Microscopy

4.5. Semiquantitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Immunofluorescence

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggleton, J.P. The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis; Aggleton, J.P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000; ISBN 978-0-19-850501-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi, C. Neuronal Localization of the 5-HT2 Receptor Family in the Amygdaloid Complex. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamanca, G.; Tagliavia, C.; Grandis, A.; Graïc, J.M.; Cozzi, B.; Bombardi, C. Distribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) Immunoreactivity in the Rat Pallial and Subpallial Amygdala and Colocalization with γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA). The Anatomical Record 2024, 307, 2891–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitkanen, A. Connectivity of the Rat Amygdaloid Complex. The amygdala, a functional analysis 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guirado, S.; Real, M.Á.; Dávila, J.C. Distinct Immunohistochemically Defined Areas in the Medial Amygdala in the Developing and Adult Mouse. Brain Research Bulletin 2008, 75, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, A. m.; Cozzi, B.; Grandis, A.; Canova, M.; Mazzoni, M.; Bombardi, C. Distribution of Calretinin Immunoreactivity in the Lateral Nucleus of the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops Truncatus) Amygdala. The Anatomical Record 2017, 300, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, P.; Faber, E.S.L.; Lopez De Armentia, M.; Power, J. The Amygdaloid Complex: Anatomy and Physiology. Physiological Reviews 2003, 83, 803–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, J.L. The Amygdala Modulates the Consolidation of Memories of Emotionally Arousing Experiences. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004, 27, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, J. The Amygdala. Current Biology 2007, 17, R868–R874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.; Neugebauer, V. Amygdala Plasticity and Pain. Pain Research and Management 2017, 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.J. The Neurobiology and Control of Anxious States. Progress in Neurobiology 2003, 70, 83–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, V.; Li, W.; Bird, G.C.; Han, J.S. The Amygdala and Persistent Pain. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.C.; Shi, C.-Q.; Franaszczuk, P.J.; Crone, N.E.; Schretlen, D.; Ohara, S.; Lenz, F.A. Painful Laser Stimuli Induce Directed Functional Interactions within and between the Human Amygdala and Hippocampus. Neuroscience 2011, 178, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T.; Sugita, S. Histological Atlas and Morphological Features by Nissl Staining in the Amygdaloid Complex of the Horse, Cow and Pig. Journal of Equine Science 2007, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Randle, H.; Pearson, G.; Preshaw, L.; Waran, N. Assessing Equine Emotional State. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2018, 205, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitzer, F.R.; Stella, N. The Therapeutic Potential of Novel Cannabinoid Receptors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2009, 122, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowin, T.; Pongratz, G.; Straub, R.H. The Synthetic Cannabinoid WIN55,212-2 Mesylate Decreases the Production of Inflammatory Mediators in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts by Activating CB2, TRPV1, TRPA1 and yet Unidentified Receptor Targets. J Inflamm (Lond) 2016, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligresti, A.; De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V. From Phytocannabinoids to Cannabinoid Receptors and Endocannabinoids: Pleiotropic Physiological and Pathological Roles Through Complex Pharmacology. Physiol Rev 2016, 96, 1593–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Hurst, D.P.; Reggio, P.H. Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture. In Phytocannabinoids; Kinghorn, A.D., Falk, H., Gibbons, S., Kobayashi, J., Eds.; Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; Vol. 103, pp. 103–131. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mlost, J.; Bryk, M.; Starowicz, K. Cannabidiol for Pain Treatment: Focus on Pharmacology and Mechanism of Action. IJMS 2020, 21, 8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.J.; Mascagni, F. Localization of the CB1 Type Cannabinoid Receptor in the Rat Basolateral Amygdala: High Concentrations in a Subpopulation of Cholecystokinin-Containing Interneurons. Neuroscience 2001, 107, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.J. Expression of the Type 1 Cannabinoid Receptor (CB1R) in CCK-Immunoreactive Axon Terminals in the Basolateral Amygdala of the Rhesus Monkey (Macaca Mulatta). Neuroscience Letters 2021, 745, 135503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, D.G. Anatomical Organization of the Primate Amygdaloid Complex. The amygdala: Neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, C.E.; Reberger, R.; Dall’Oglio, A.; Calcagnotto, M.E.; Rasia-Filho, A.A. Neuronal Types of the Human Cortical Amygdaloid Nucleus. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2018, 526, 2776–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.J. Chapter 1 - Functional Neuroanatomy of the Basolateral Amygdala: Neurons, Neurotransmitters, and Circuits. In Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience; Urban, J.H., Rosenkranz, J.A., Eds.; Handbook of Amygdala Structure and Function; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 26, pp. 1–38.

- McDonald, A.J.; Augustine, J.R. Nonpyramidal Neurons in the Primate Basolateral Amygdala: A Golgi Study in the Baboon (Papio Cynocephalus) and Long-Tailed Macaque (Macaca Fascicularis). Journal of Comparative Neurology 2020, 528, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.F.; Mascagni, F.; McDonald, A.J. Postsynaptic Targets of Somatostatin-Containing Interneurons in the Rat Basolateral Amygdala. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2007, 500, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascagni, F.; McDonald, A.J. Immunohistochemical Characterization of Cholecystokinin Containing Neurons in the Rat Basolateral Amygdala. Brain research 2003, 976, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainnie, D.G.; Mania, I.; Mascagni, F.; McDonald, A.J. Physiological and Morphological Characterization of Parvalbumin-Containing Interneurons of the Rat Basolateral Amygdala. J Comp Neurol 2006, 498, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, A.J.; Pearson, J.C. Coexistence of GABA and Peptide Immunoreactivity in Non-Pyramidal Neurons of the Basolateral Amygdala. Neuroscience Letters 1989, 100, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degroot, A. Role of Cannabinoid Receptors in Anxiety Disorders. In Cannabinoids and the Brain; Köfalvi, A., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2008; pp. 559–572. ISBN 978-0-387-74349-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zamith Cunha, R.; Zannoni, A.; Salamanca, G.; De Silva, M.; Rinnovati, R.; Gramenzi, A.; Forni, M.; Chiocchetti, R. Expression of Cannabinoid (CB1 and CB2) and Cannabinoid-Related Receptors (TRPV1, GPR55, and PPARα) in the Synovial Membrane of the Horse Metacarpophalangeal Joint. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamith Cunha, R.; Semprini, A.; Salamanca, G.; Gobbo, F.; Morini, M.; Pickles, K.J.; Roberts, V.; Chiocchetti, R. Expression of Cannabinoid Receptors in the Trigeminal Ganglion of the Horse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiazzo, G.; De Silva, M.; Giancola, F.; Rinnovati, R.; Peli, A.; Chiocchetti, R. Cellular Distribution of Cannabinoid-related Receptors TRPV1, PPAR-gamma, GPR55 and GPR3 in the Equine Cervical Dorsal Root Ganglia. Equine Vet J 2022, 54, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, R.; Rinnovati, R.; Tagliavia, C.; Stanzani, A.; Galiazzo, G.; Giancola, F.; Silva, M.D.; Capodanno, Y.; Spadari, A. Localisation of Cannabinoid and Cannabinoid-Related Receptors in the Equine Dorsal Root Ganglia. Equine Vet J 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscaia, M.; Marín, S.; Fernández, B.; Marco, E.M.; Rubio, M.; Guaza, C.; Ambrosio, E.; Viveros, M.P. Chronic Treatment with CP 55,940 during the Peri-Adolescent Period Differentially Affects the Behavioural Responses of Male and Female Rats in Adulthood. Psychopharmacology 2003, 170, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urigüen, L.; Pérez-Rial, S.; Ledent, C.; Palomo, T.; Manzanares, J. Impaired Action of Anxiolytic Drugs in Mice Deficient in Cannabinoid CB1 Receptors. Neuropharmacology 2004, 46, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacology of Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1997, 74, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshan, F.; Day, T.A.; Blakely, R.D.; Barker, E.L. Carrier-Mediated Uptake of the Endogenous Cannabinoid Anandamide in RBL-2H3 Cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000, 292, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz-Cinar, O. The Endocannabinoid System in the Amygdala and Modulation of Fear. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2021, 105, 110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz-Cinar, O.; Castillo, L.I.; Xia, M.; Leer, E.V.; Brockway, E.T.; Pollack, G.A.; Yasmin, F.; Bukalo, O.; Limoges, A.; Oreizi-Esfahani, S.; et al. A Cortico-Amygdala Neural Substrate for Endocannabinoid Modulation of Fear Extinction. Neuron 2023, 111, 3053–3067.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, A. Endocannabinoids Modulate Fear Extinction Controlled by a Cortical-Amygdala Projection. Neuron 2023, 111, 2948–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Cravatt, B.F.; Hillard, C.J. Synergistic Interactions between Cannabinoids and Environmental Stress in the Activation of the Central Amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacol 2005, 30, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsicano, G.; Wotjak, C.T.; Azad, S.C.; Bisogno, T.; Rammes, G.; Cascio, M.G.; Hermann, H.; Tang, J.; Hofmann, C.; Zieglgänsberger, W.; et al. The Endogenous Cannabinoid System Controls Extinction of Aversive Memories. Nature 2002, 418, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, S.C.; Monory, K.; Marsicano, G.; Cravatt, B.F.; Lutz, B.; Zieglgänsberger, W.; Rammes, G. Circuitry for Associative Plasticity in the Amygdala Involves Endocannabinoid Signaling. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 9953–9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, K.; Olango, W.M.; Harhen, B.; Kerr, D.M.; Galligan, R.; Fitzgerald, S.; Moore, M.; Roche, M.; Finn, D.P. Evidence for a Role of GABAergic and Glutamatergic Signalling in the Basolateral Amygdala in Endocannabinoid-Mediated Fear-Conditioned Analgesia in Rats. PAIN 2013, 154, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, T.; Sala, M.; Viganò, D.; Braida, D.; Castiglioni, C.; Limonta, V.; Guidali, C.; Realini, N.; Parolaro, D. Cellular Mechanisms Underlying the Anxiolytic Effect of Low Doses of Peripheral Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaivi, E.S.; Ishiguro, H.; Gong, J.-P.; Pa℡, S.; Perchuk, A.; Meozzi, P.A.; Myers, L.; Mora, Z.; Tagliaferro, P.; Gardner, E.; et al. Discovery of the Presence and Functional Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors in Brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006, 1074, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, G.A.; Raborn, E.S.; Griffin, L.; Dennis, J.; Marciano-Cabral, F. CB2 Receptors in the Brain: Role in Central Immune Function. British Journal of Pharmacology 2008, 153, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusco, A.; Tagliaferro, P.; Saez, T.; Onaivi, E.S. Postsynaptic Localization of CB2 Cannabinoid Receptors in the Rat Hippocampus. Synapse 2008, 62, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Finn, D.P. Brain CB2 Receptors: Implications for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 2517–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, B.K.; Mackie, K. CB2: A Cannabinoid Receptor with an Identity Crisis. British Journal of Pharmacology 2010, 160, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi, A.; Al Mansouri, S.; Al Memari, E.; Al Ameri, M.; Nurulain, S.M.; Ojha, S. β-Caryophyllene, a CB2 Receptor Agonist Produces Multiple Behavioral Changes Relevant to Anxiety and Depression in Mice. Physiology & Behavior 2014, 135, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramikie, T.S.; Patel, S. Endocannabinoid Signaling in the Amygdala: Anatomy, Synaptic Signaling, Behavior, and Adaptations to Stress. Neuroscience 2012, 204, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Manzanares, J. Overexpression of CB2 Cannabinoid Receptors Decreased Vulnerability to Anxiety and Impaired Anxiolytic Action of Alprazolam in Mice. J Psychopharmacol 2011, 25, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, B.H.; Martin, W.J.; Meng, I.D. The Rodent Amygdala Contributes to the Production of Cannabinoid-Induced Antinociception. Neuroscience 2003, 120, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argue, K.J.; VanRyzin, J.W.; Falvo, D.J.; Whitaker, A.R.; Yu, S.J.; McCarthy, M.M. Activation of Both CB1 and CB2 Endocannabinoid Receptors Is Critical for Masculinization of the Developing Medial Amygdala and Juvenile Social Play Behavior. eNeuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, A.; Akirav, I. Cannabinoids and Glucocorticoids in the Basolateral Amygdala Modulate Hippocampal–Accumbens Plasticity After Stress. Neuropsychopharmacol 2016, 41, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschenderlein, C.; Gebhardt, C.; Halbach, O. von B. und; Kulisch, C.; Albrecht, D. Capsaicin-Induced Changes in LTP in the Lateral Amygdala Are Mediated by TRPV1. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e16116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsch, R.; Foeller, E.; Rammes, G.; Bunck, M.; Kössl, M.; Holsboer, F.; Zieglgänsberger, W.; Landgraf, R.; Lutz, B.; Wotjak, C.T. Reduced Anxiety, Conditioned Fear, and Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation in Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 1 Receptor-Deficient Mice. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.J.P.A.; Stern, C.A.J.; Bertoglio, L.J. Attenuation of Anxiety-Related Behaviour after the Antagonism of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 1 Channels in the Rat Ventral Hippocampus. Behavioural Pharmacology 2008, 19, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsicano, G.; Kuner, R. Anatomical Distribution of Receptors, Ligands and Enzymes in the Brain and in the Spinal Cord: Circuitries and Neurochemistry. In Cannabinoids and the Brain; Köfalvi, A., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2008; pp. 161–201. ISBN 978-0-387-74349-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkedal, C.; Wegener, G.; Moreira, F.; Joca, S.R.L.; Liebenberg, N. A Dual Inhibitor of FAAH and TRPV1 Channels Shows Dose-Dependent Effect on Depression-like Behaviour in Rats. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2017, 29, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, B.; Merighi, A. Capsaicin, Nociception and Pain. Molecules 2016, 21, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, I.; White, J.P.M.; Paule, C.C.; Maze, M.; Urban, L. Functional Molecular Biology of the TRPV1 Ion Channel. In Cannabinoids and the Brain; Köfalvi, A., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2008; pp. 101–130. ISBN 978-0-387-74349-3. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.-A.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Xu, G.-Y. TRPV1-Mediated Presynaptic Transmission in Basolateral Amygdala Contributes to Visceral Hypersensitivity in Adult Rats with Neonatal Maternal Deprivation. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.G. TRPV1 in the Central Nervous System: Synaptic Plasticity, Function, and Pharmacological Implications. Prog Drug Res 2014, 68, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolezzi, J.M.; Santos, M.J.; Bastías-Candia, S.; Pinto, C.; Godoy, J.A.; Inestrosa, N.C. PPARs in the Central Nervous System: Roles in Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation. Biological Reviews 2017, 92, 2046–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristiano, L.; Bernardo, A.; Cerù, M.P. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) and Peroxisomes in Rat Cortical and Cerebellar Astrocytes. J Neurocytol 2001, 30, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, S.; Farioli-Vecchioli, S.; Cerù, M.P. Immunolocalization of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Retinoid X Receptors in the Adult Rat CNS. Neuroscience 2004, 123, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, A.; Truitt, J.; Merriman, M.; Ponomareva, O.; Jameson, K.; Ferguson, L.B.; Mayfield, R.D.; Harris, R.A. Localization of PPAR Isotypes in the Adult Mouse and Human Brain. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 27618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, C.R.; Emborg, M.E. Expression of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ in the Substantia Nigra of Hemiparkinsonian Nonhuman Primates. Neurol Res 2014, 36, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.; Levi, G.; Minghetti, L. Role of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) and Its Natural Ligand 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-Prostaglandin J2 in the Regulation of Microglial Functions. European Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 12, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.D.; Leisewitz, A.V.; Jung, J.E.; Cassina, P.; Barbeito, L.; Inestrosa, N.C.; Bronfman, M. PPAR Gamma Activators Induce Growth Arrest and Process Extension in B12 Oligodendrocyte-like Cells and Terminal Differentiation of Cultured Oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res 2003, 72, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma, C.; Stellwagen, H.; Fister, M.; Coultrap, S.J.; Mesches, M.H.; Browning, M.D.; Bickford, P.C. Rosiglitazone Improves Contextual Fear Conditioning in Aged Rats. Neuroreport 2004, 15, 2255–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.C.; Okine, B.N.; Dinneen, D.; Roche, M.; Finn, D.P. Effects of Intra-BLA Administration of PPAR Antagonists on Formalin-Evoked Nociceptive Behaviour, Fear-Conditioned Analgesia, and Conditioned Fear in the Presence or Absence of Nociceptive Tone in Rats. Molecules 2022, 27, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.J.; Mascagni, F. Localization of the CB1 Type Cannabinoid Receptor in the Rat Basolateral Amygdala: High Concentrations in a Subpopulation of Cholecystokinin-Containing Interneurons. Neuroscience 2001, 107, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, D.L.; Fowler, C.B.; Cunningham, B.R.; Mason, J.T.; O’Leary, T.J. The Effect of Formaldehyde Fixation on RNA. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2011, 13, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, W.; Greytak, S.; Odeh, H.; Guan, P.; Powers, J.; Bavarva, J.; Moore, H.M. Deleterious Effects of Formalin-Fixation and Delays to Fixation on RNA and miRNA-Seq Profiles. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiocchetti, R.; Rinnovati, R.; Tagliavia, C.; Stanzani, A.; Galiazzo, G.; Giancola, F.; Silva, M.D.; Capodanno, Y.; Spadari, A. Localisation of Cannabinoid and Cannabinoid-related Receptors in the Equine Dorsal Root Ganglia. Equine Vet J 2021, 53, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiazzo, G.; Tagliavia, C.; Giancola, F.; Rinnovati, R.; Sadeghinezhad, J.; Bombardi, C.; Grandis, A.; Pietra, M.; Chiocchetti, R. Localisation of Cannabinoid and Cannabinoid-Related Receptors in the Horse Ileum. J Equine Vet Sci 2021, 104, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczyk, P.; Rykala, M.; Serek, P.; Pawlak, A.; Slowikowski, B.; Holysz, M.; Chodaczek, G.; Madej, J.P.; Ziolkowski, P.; Niedzwiedz, A. The Cannabinoid Receptors System in Horses: Tissue Distribution and Cellular Identification in Skin. J Vet Intern Med 2022, 36, 1508–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, J. Anxiety Modulation by Cannabinoids—The Role of Stress Responses and Coping. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).