Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

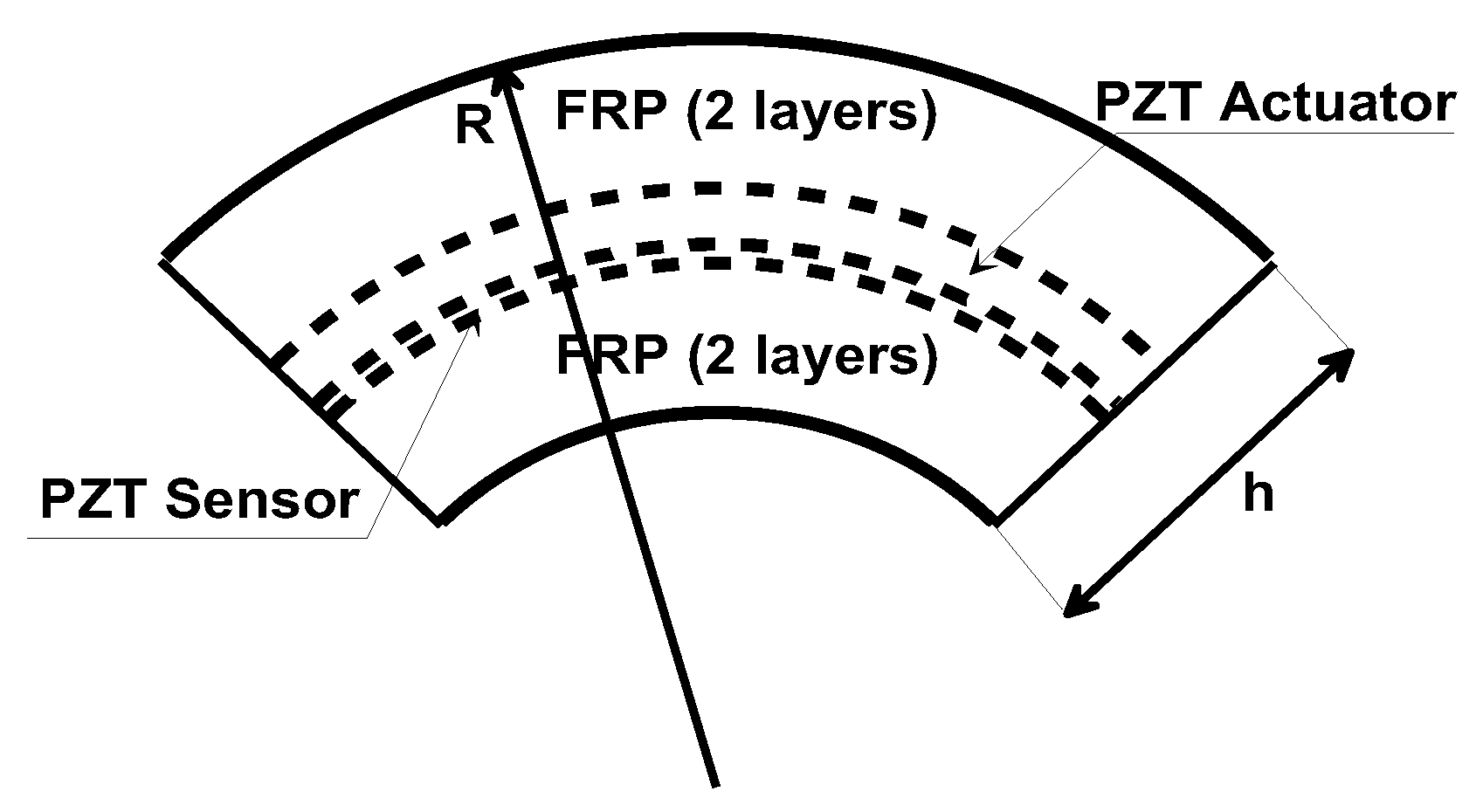

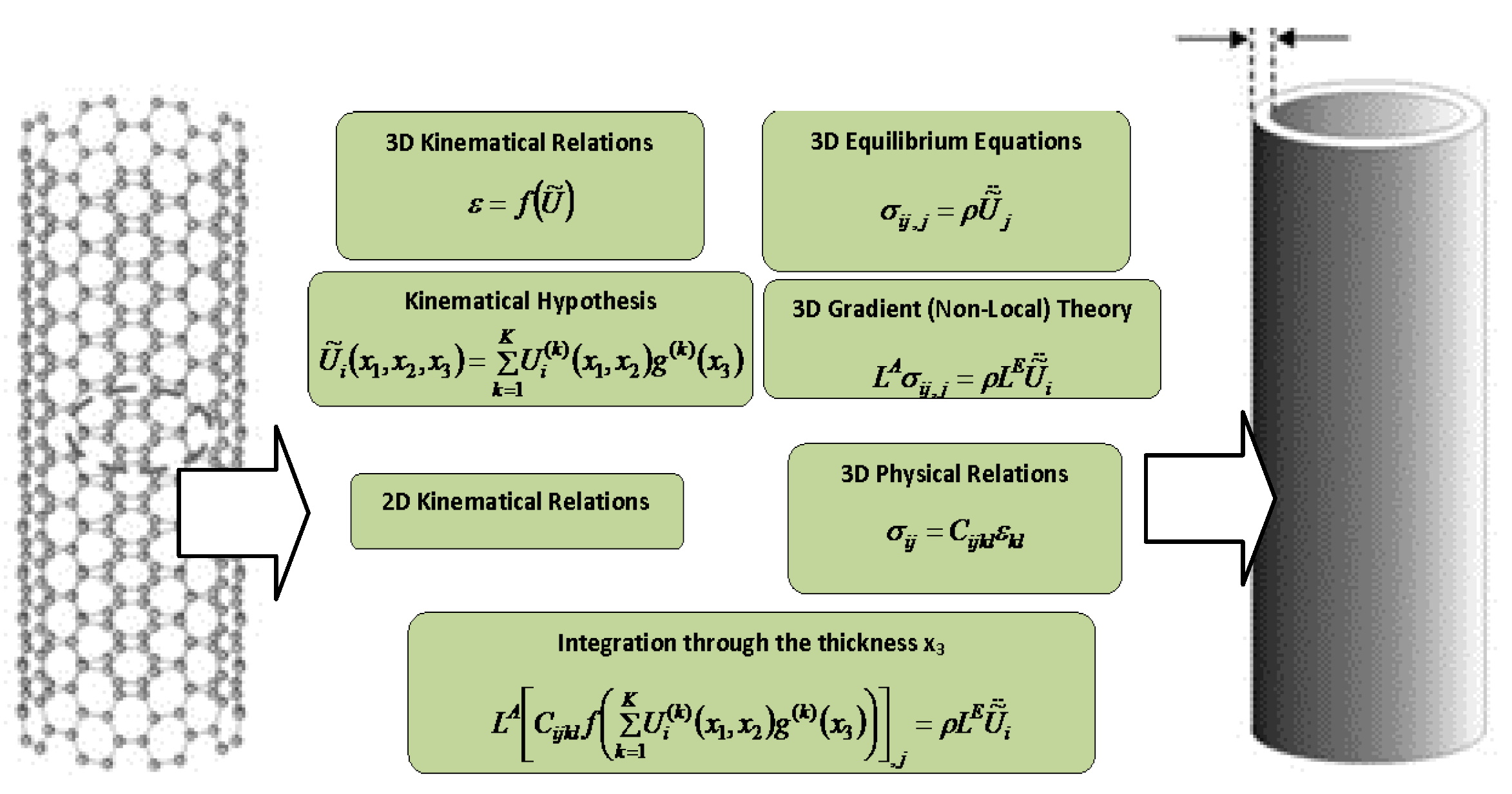

2. Formulation of the Local Coupled Electro-Mechanical Problem

2.1. Kinematic Relations

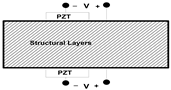

2.2. Constitutive Equations and Variational Formulation

2.3. Non-Local Formulation

3. Numerical Results

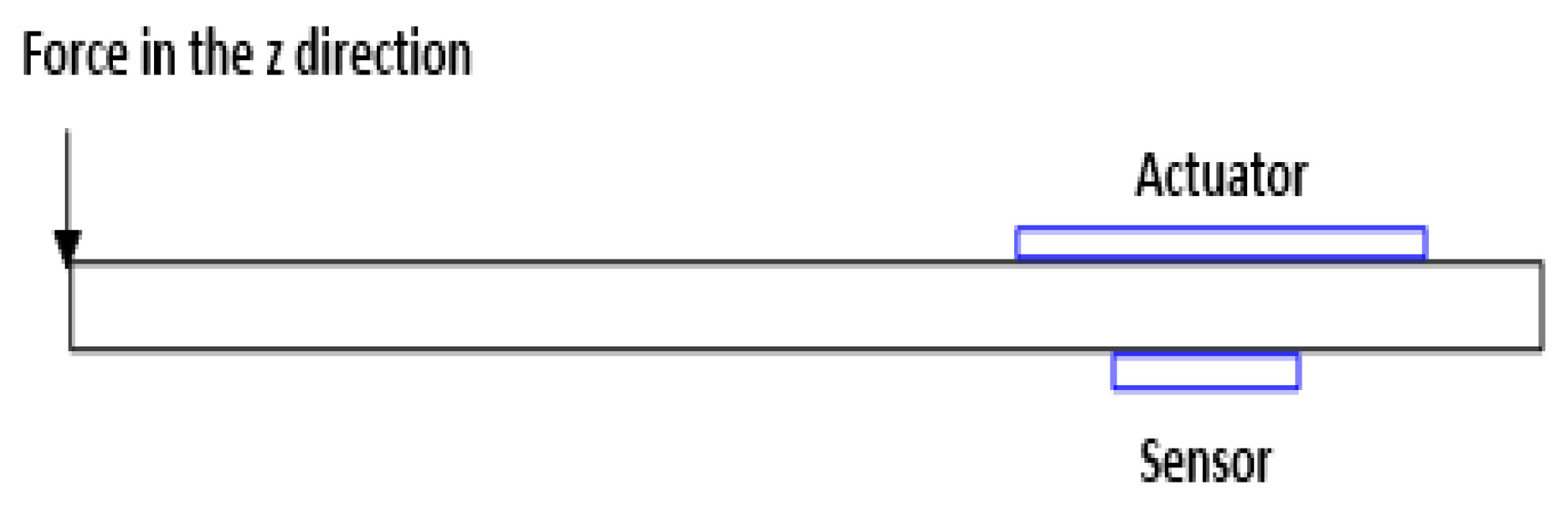

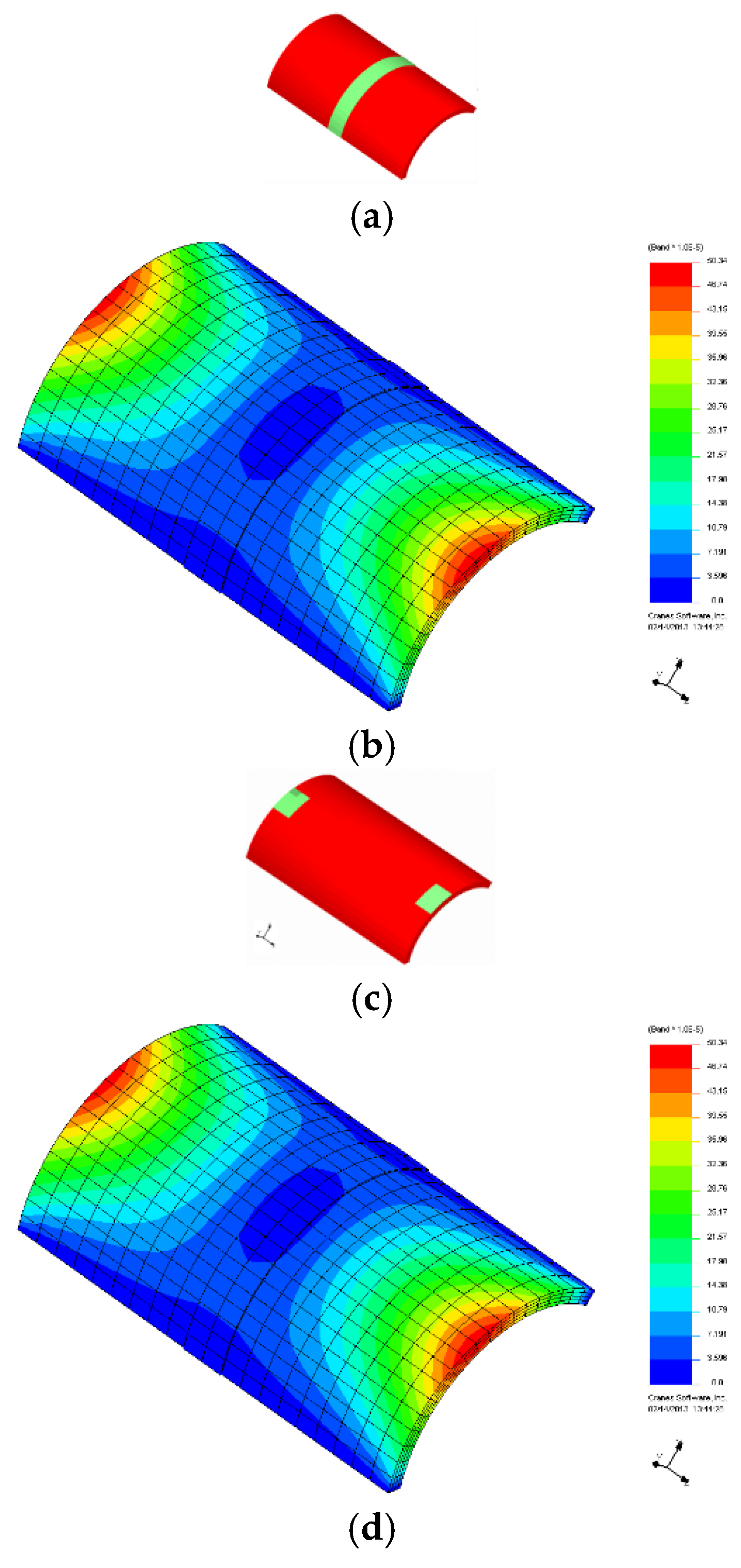

3.1. Active Vibration Control–Shear Actuator

3.2. Smart Beam Structure – Extension Actuator

3.3. Location of Passive Actuators

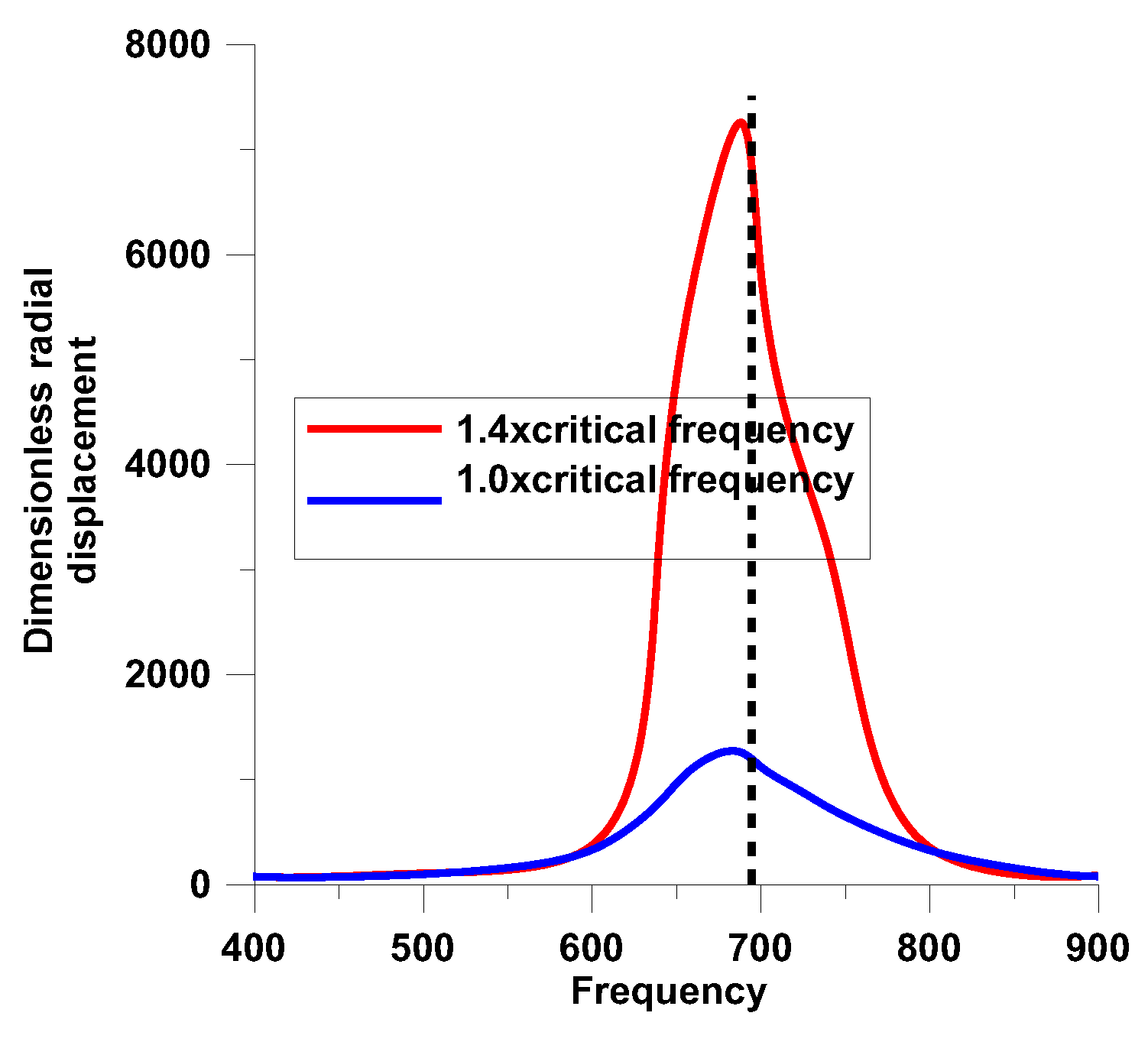

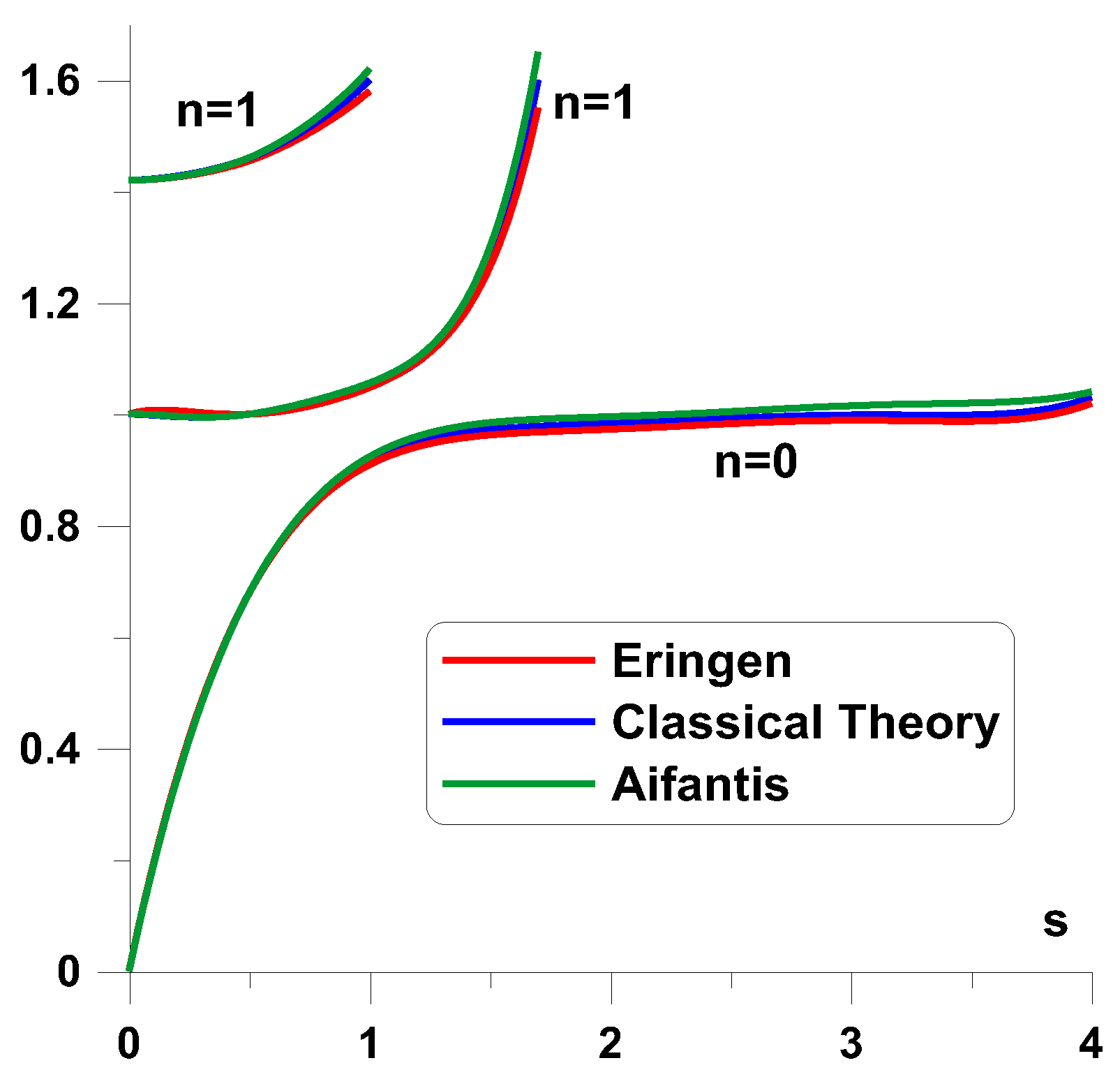

4. Non-Local Formulation

5. Concluding Remarks

- Local formulation and shear vibration control.

- Local formulation and extension displacement control.

- Non-local vibration control.

References

- Crawley, E.F. and Luis, J., Use of piezoelectric actuators as elements of intelligent structures, AIAA Journal, Vol.25, 1987, pp.1373–1385.

- Zappino, E.; Carrera, E. Advanced modeling of embedded piezo-electric transducers for the health-monitoring of layered structures. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2020, 11, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J. On laminated composite plates with integrated sensors and actuators. Eng. Struct. 1999, 21, 568–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, H.; Gadre, M. Theoretical analysis of a multi-layered thin shell coupled with piezoelectric shell actuators for distributed vibration controls. J. Sound Vib. 1989, 132, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M. , Smart analysis of doubly curved piezoelectric nano shells: Electrical and mechanical buckling analysis, Smart Structures and Systems, Vol.25,2020, pp.471-486.

- Mousavi, M. , Mohammadimehr, M. and Rostami, R., Analytical solution for buckling analysis of micro sandwich hollow circular plate, Computers and Concrete, Vol.24, 2019,pp.185-192.

- Farrokhian, A. , Buckling response of smart plates reinforced by nanoparticles utilizing analytical method, Steel and Composite Structures, Vol.35,2020,pp.1-12.

- Moosazadeh, H. and Mohammadi, M.M., Two-dimensional curved panel vibration and flutter analysis in the frequency and time domain under thermal and in-plane load, Advances in Aircraft and Spacecraft Science, Vol.8,2021, pp.345-372.

- Gharaei, A. , Rabieyan-Najafabadi, H., Nejatbakhsh, H. and Ghasemi, A.R., An analytical approach for aeroelastic analysis of tail flutter, Advances in Computational Design, Vol.7, 2022, pp.69-79.

- Atabakhshian, V. and Shooshtaria, A., A study on the dynamic instabilities of a smart embedded micro-shell induced by a pulsating flow: A nonlocal piezoelastic approach, Advances in Nano Research, Vol.9,2020, pp.133-145.

- Muc, A.; Flis, J.; Augustyn, M. Optimal Design of Plated/Shell Structures under Flutter Constraints—A Literature Review. Materials 2019, 12, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muc, A.; Flis, J. Free vibrations and supersonic flutter of multilayered laminated cylindrical panels. Compos. Struct. 2020, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X. Free vibration of laminated piezoelectric composite plates based on an accurate theory. Compos. Struct. 2005, 67, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. , Qi, C., Fang, H. and Sun, X., Bending and free vibration analysis of laminated piezoelectric composite plates, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol.75, 2020, pp.747-769.

- Arefi, M. and Meskini, M., Application of hyperbolic shear deformation theory to free vibration analysis of functionally graded porous plate with piezoelectric face-sheets, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol. 71, 2019, pp. 459-467.

- Singh, A. and Kumari, P., Analytical free vibration solution for angle-ply piezolaminated plate under cylindrical bending: A piezo-elasticity approach, Advances in Computational Design, Vol.5, 2020, pp. 55-89.

- Zenkour, A.M. and Hafed, Z.S., Bending response of functionally graded piezoelectric plates using a two-variable shear deformation theory, Advances in Aircraft and Spacecraft Science, Vol. 7,2020, pp. 115-134.

- Dehsaraji, M.L. , Saidi, A.R. and Mohammadi, M., Bending analysis of thick functionally graded piezoelectric rectangular plates using higher-order shear and normal deformable plate theory, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol.73,2020, pp. 256-269.

- Ridha, A.A. , Basima, S.K., Kareem, M.R., Raad, M.F. and Nadhim M.F., Investigating dynamic response of nonlocal functionally graded porous piezoelectric plates in thermal environment, Steel and Composite Structures, Vol. 40, 2021, pp. 243-254.

- Heidari, F. , Afsari, A. and Janghorban, M., Several models for bending and buckling behaviors of FG-CNTRCs with piezoelectric layers including size effects, Advances in Nano Research,Vol.9, 2020, pp.193-210.

- Taherifar, R. , Mahmoudi, M., Nasr Esfahani, M.H., Khuzani, N.A., Nasr Esfahani, S. and Chinaei, F., Buckling analysis of concrete plates reinforced by piezoelectric nano-particles, Computers and Concrete, Vol.23, 2019, pp. 295-301.

- Ebrahimi, F. , Hosseini, S.H.S. and Singhal, A., A comprehensive review on the modeling of smart piezoelectric nanostructures, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol. 74, 2020, pp. 611-633.

- Karami, B. and Shahsavari, D., Nonlocal strain gradient model for thermal stability of FG nanoplates integrated with piezoelectric layers, Smart Structures and Systems, Vol.23, 2019, pp. 215-225.

- Kunbar, L.A. H, Alkadhimi, B.M., Radhi, H.S. and Faleh, N.M., Flexoelectric effects on dynamic response characteristics of nonlocal piezoelectric material beam, Advances in Materials Research, Vol. 8, 2019, pp. 259-274.

- Singh, A.K. , Negi, A. and Koley, S., Influence of surface irregularity on dynamic response induced due to a moving load on functionally graded piezoelectric material substrate, Smart Structures and Systems, Vol. 23, 2019, pp. 31-44.

- Asghar, S. , Khadimallah, M.A., Naeem, M.N., Ghamkhar, M., Khedher, K.M., Hussain, M., Bouzgarrou, S.M., Ali, Z., Iqbal, Z., Mahmoud, S.R., Algarni, A., Taj, M. and Tounsi, A., Small scale computational vibration of double-walled CNTs: Estimation of non-local shell model, Advances in Concrete Construction, Vol.10, 2020, pp. 345-355.

- Timesli, A. , A cylindrical shell model for non-local buckling behavior of CNTs embedded in an elastic foundation under the simultaneous effects of magnetic field, temperature change, and number of walls, Advances in Nano Research, Vol.11, 2021, pp. 581-593.

- Mirjavadi, S.S. , Bayani, H., Khoshtinat, N., Forsat, M., Barati, M.R. and Hamouda, A.M.S, On nonlinear vibration behavior of piezo-magnetic doubly-curved nanoshells, Smart Structures and Systems, Vol. 26, 2020, pp. 631-640.

- Song, Y. and Xu, J., Multi-phase magneto-electro-elastic stability of nonlocal curved composite shells, Steel and Composite Structures, Vol. 41, 2021, pp. 775-785.

- Muc, A. Non-local approach to free vibrations and buckling problems for cylindrical nano-structures. Compos. Struct. 2020, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, J.F.A.; Araujo, A.L. Optimal distribution of active piezoelectric elements for noise attenuation in sandwich panels. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2020, 11, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katariya, P.V. and Panda, S.K., Numerical frequency analysis of skew sandwich layered composite shell structures under thermal environment including shear deformation effects, Structural Engineering. and Mechanics, Vol. 71, 2019, pp. 657-668.

- Safari, M. , Mohammadimehr, M. and Ashrafi, H., Free vibration of electro-magneto-thermo sandwich Timoshenko beam made of porous core and GPLRC, Advances in Nano Research, Vol. 10, 2021, pp. 115-128.

- Mohammadimehr, M. , Firouzeh, S., Pahlavanzadeh, M., Heidari, Y. and Irani-Rahaghi, M., Free vibration of sandwich micro-beam with porous foam core, GPL layers and piezo-magneto-electric face sheets via NSGT, Computers and Concrete, Vol.26, 2020, pp.75-94.

- Rostami, R. , Mohammadimehr, M. and Rahaghi, M.I., Dynamic stability and nonlinear vibration of rotating sandwich cylindrical shell with considering FG core integrated with sensor and actuator, Steel and Composite Structures, Vol.32, 2019, pp.225-237.

- Amini, A. , Mohammadimehr, M. and Faraji, A., Optimal placement of piezoelectric actuator/senor patches pair in sandwich plate by improved genetic algorithm, Smart Structures and Systems, Vol.26, 2020, pp.721-733.

- Muc, A.; Stawiarski, A.; Romanowicz, P. Experimental Investigations of Compressed Sandwich Composite/Honeycomb Cylindrical Shells. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2017, 25, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Ye, L.; Lu, Y. Guided Lamb waves for identification of damage in composite structures: A review. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 295, 753–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanthakumar, S.; Lahmer, T.; Zhuang, X.; Zi, G.; Rabczuk, T. Detection of material interfaces using a regularized level set method in piezoelectric structures. Inverse Probl. Sci. Eng. 2015, 24, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F. , Hosseini, S.H.S. and Singhal, A., A comprehensive review on the modeling of smart piezoelectric nanostructures, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol.74, 2020, pp. 611-633.

- Ali, Z. , Khadimallah, M.A., Hussain, M., Asghar, S., Al-Thobiani, F., Elbahar, M., Elimame, E. and Tounsi, A., Propagation of waves with nonlocal effects for vibration response of armchair double-walled CNTs, Advances in Nano Research, Vol.11, 2021, pp. 183-192.

- Yang, S. , Jung, J., Liu, P., Lim, H.J., Yi, Y., Sohn, H. and Bae, I., Ultrasonic wireless sensor development for online fatigue crack detection and failure warning, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol. 69, 2019, pp. 407-416.

- Asghar, S. , Naeem, M.N., Hussain, M. and Tounsi, A., Nonlocal vibration of DWCNTs based on Flügge shell model using wave propagation approach, Steel and Composite Structures, Vol. 34, 2020, pp.

- Bambach, M.R.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Experimental techniques for testing unstiffened plates in compression and bending. Exp. Mech. 2004, 44, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Tannuri, E.A. Modeling, control and experimental validation of a novel actuator based on shape memory alloys. Mechatronics 2009, 19, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muc, A.; Kubis, S.; Bratek, Ł.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Higher order theories for the buckling and post-buckling studies of shallow spherical shells made of functionally graded materials. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabili, M. A non-linear higher-order thickness stretching and shear deformation theory for large-amplitude vibrations of laminated doubly curved shells. Int. J. Non-linear Mech. 2014, 58, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. , Qi, C., Fang, H. and Sun, X., Bending and free vibration analysis of laminated piezoelectric composite plates, Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol.75, 2020, pp.747-769.

- Chen, H.; Wang, A.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W. Free vibration of FGM sandwich doubly-curved shallow shell based on a new shear deformation theory with stretching effects. Compos. Struct. 2017, 179, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfan, S.; Anamagh, M.R.; Bediz, B. A general higher-order model for vibration analysis of axially moving doubly-curved panels/shells. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.; Phan, N. Stability and vibration of isotropic, orthotropic and laminated plates according to a higher-order shear deformation theory. J. Sound Vib. 1985, 98, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Friswell, M.; Inman, D.J. The relationship between positive position feedback and output feedback controllers. Smart Mater. Struct. 1999, 8, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vel, S.S.; Baillargeon, B.P. Analysis of Static Deformation, Vibration and Active Damping of Cylindrical Composite Shells with Piezoelectric Shear Actuators. J. Vib. Acoust. 2004, 127, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagülle, H.; Malgaca, L.; Öktem, H.F. Analysis of active vibration control in smart structures by ANSYS. Smart Mater. Struct. 2004, 13, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muc, A. Evolutionary Design of Engineering Constructions. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eringen, A. , Microcontinuum field theories; Foundations and solids, Springer Science & Busines Media, 2012.

- Aifantis, E.C. On the Microstructural Origin of Certain Inelastic Models. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1984, 106, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindlin, R.D.; Tiersten, H.F. Effects of couple-stresses in linear elasticity. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1962, 11, 415–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

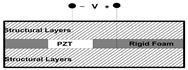

| (a) extension actuator | (b) shear actuator |

| Number of variables | Number of indepen-dent variables | ||

| TSE/ SN – [47,48] | 14 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2,, ψ1, ψ2, γ1, γ2, θ1, θ2,χ1, χ2 ,χ3 | 8 -u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2, χ1, χ2 ,χ3 | 4-th order TSE/ SN |

| TSE/ SN –– [49] | 13 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2,, ψ1, ψ2, γ1, γ2, θ1, θ2,χ1, χ2 | 7 -u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2, χ1, χ2 | 3-rd order TSE/ SN |

| TSE/ SN – [50], | 12 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2, , ψ1, ψ2, γ1, γ2, θ1, θ2,χ1 | 6 -u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2, χ1 | 3-rd order TSE/ SN |

| TSE [51] | 5 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2 | 5 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2 | 3-rd order TSE |

| TSE | 5 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2 | 5 - u, v, w, ϕ1, ϕ2 | 1-rd order TSE |

| L-K | 3 - u, v, w | 3 - u, v, w | L-K |

| Mode | Natural frequency [Hz] | ||

| [51] – FE 3D Model- ABAQUS |

Present analysis – NISA II |

||

| 1.Bending | 683.3 | 690.7 | 689.7 |

| 2. Out of plane | 2393.7 | 2454.1 | 2505.2 |

| 3. Bending | 2858.2 | 2907.4 | 2791.9 |

| 4. Out of plane | 4780.8 | 4783.4 | 4693.2 |

| 5. Bending | 5254.7 | 5292.1 | 5387.2 |

| 6. Out of plane | 7156.8 | 7342.6 | 7245.3 |

| 7.Bending | 7636.6 | 7600.4 | 7795.6 |

| 8. Bending | 9984.2 | 9645.2 | 9342.3 |

| 9. Shear | 10223.9 | 10443.9 | 10396.1 |

| Mode | Natural Frequency dB | ||

| Ansys Karagulle FE 3D Model | Present analysis – NISA II |

||

| FE – 2D | FE- 3D | ||

| 29.7 | 24.5 | 24.4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).