1. Introduction

Protein folding is governed by complex interactions generating both ordered pathways and regions of energetic conflict (Bhatia and Udgaonkar 2022; Sorokina, Mushegian, and Koonin 2022; Englander 2023; Wyatt et al. 2025). The concept of protein frustration was introduced to capture situations where competing local interactions cannot be simultaneously satisfied, resulting in rugged energy landscapes, kinetic traps and alternative conformational routes (Gianni et al. 2021; Zhou, Song, and Li 2022; Haque et al. 2023; Freiberger et al. 2023; Guan et al. 2024). Experimental approaches, including NMR ensembles, hydrogen–deuterium exchange and single-molecule spectroscopy, have established that protein frustration is not uniformly distributed but rather localized at specific residues and structural regions (Vadas et al. 2017; Hodge, Benhaim, and Lee 2020; Petrosyan, Narayan, and Woodside 2021; Fernández-Quintero et al. 2022; Theillet and Luchinat 2022; Huang et al. 2023; Wijesinghe and Min 2023). Computational tools such as the Frustratometer and related indices assess frustration by comparing native contacts against energetic decoys, highlighting regions of elevated conflict that correlate with allostery, mutational sensitivity and dynamic switching (Parra et al. 2016; González-Higueras et al. 2024). Despite their utility, these approaches are empirical and lack a general theoretical principle explaining why efficient folding is possible despite the high dimensionality of conformational space. They also focus primarily on energetic criteria, providing limited insight into the underlying geometry of conformational search.

We introduce a geometric perspective based on Dvoretzky’s theorem from high-dimensional convex geometry, which guarantees the presence of nearly Euclidean subspaces within any sufficiently large normed vector space (Milman 1992; Villaverde, Kosheleva, and Ceberio 2014; Tikhomirov 2018). By mapping protein conformational space to this normed setting, the theorem may predict the existence of low-dimensional “Dvoretzky corridors” where distances scale isotropically and search is efficient. Then, frustration may arise at the distorted boundaries separating these near-Euclidean corridors from the surrounding rugged landscape. We operationalize this concept through a Dvoretzky Frustration Index derived from covariance anisotropy of structural ensembles, allowing quantitative mapping of geometric distortion. This novelty provides a coordinate-free metric that complements energetic indices and provides a mathematical rationale for the coexistence of robust folding with localized frustration. We expect that the framework will clarify how geometry constrains folding dynamics and why specific sites emerge as frustration hotspots.

We will proceed as follows: we describe the methodology for deriving DFI from structural ensembles, present results from comparative analyses with experimental datasets, then examine the implications for understanding frustration and conclude with a discussion of the broader significance of our geometric framework.

2. Materials and Methods

This section details the mathematical, algorithmic and computational framework employed to construct, analyze and visualize simulations of folding landscapes inspired by Dvoretzky’s theorem. Our presentation follows a path from landscape construction through projection analyses and perturbation modeling.

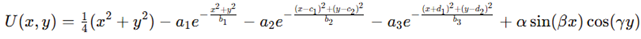

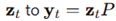

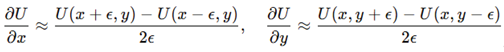

Construction of the energy landscape. Our simulation began by defining a two-dimensional artificial energy landscape as a reduced model of protein conformational space. The potential was constructed as a superposition of quadratic confinement, Gaussian wells (Rodriguez-Espejo et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2024) for

with

,

shifts

,

and

. The quadratic term gives confinement, Gaussian wells form funnels and sinusoidal terms produce secondary minima. A 500×500 mesh over

evaluated this function, yielding a scalar field that serves as reference for trajectories and visualizations. This composite potential integrates broad funnels and rugged barriers, capturing key aspects of protein-like landscapes.

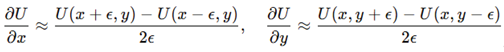

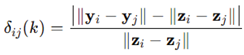

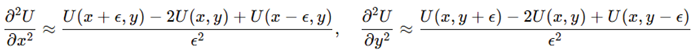

Gradient and Hessian evaluation. Dynamics required gradients and curvature from the potential. Central finite differences with gave

Second derivatives used

:

These formed the symmetric Hessian , providing the curvature and anisotropy estimates required for geometric analysis.

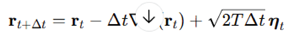

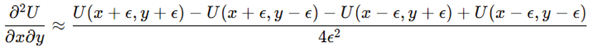

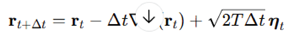

Langevin dynamics of folding trajectories. Folding was simulated by overdamped Langevin dynamics:

with step

, temperature

and Gaussian noise vector

. This corresponds to the stochastic differential equation

From initial , 2500 steps were generated, each combining deterministic descent and random perturbation. Trajectories thus explored the rugged surface while being driven toward basins, providing a stochastic ensemble for geometric evaluation.

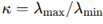

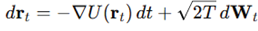

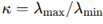

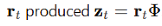

Definition of the Dvoretzky Frustration Index. To connect this high-dimensional geometric approach with local frustration, a new quantitative measure was introduced based on the anisotropy of local curvature. The Dvoretzky Frustration Index (DFI) was defined in terms of the eigenvalue spectrum of the Hessian matrix. If the eigenvalues of

, both positive after absolute-value stabilization, the condition number is given by

The DFI was then expressed as.

By construction, , with values approaching zero when eigenvalues are equal and the curvature isotropic, and approaching one when the spectrum is highly anisotropic. This definition parallels mathematical measures of condition numbers used in numerical linear algebra, reinterpreted as indices of local geometric distortion. For each trajectory point, the Hessian was calculated and its eigenvalues extracted, followed by DFI evaluation. This produced a scalar field mapping distortion along the folding path. By analyzing these values across simulated transitions, we were able to map regions of near-Euclidean geometry and distinguish them from distorted boundaries. The DFI thus operationalizes Dvoretzky’s theorem by identifying effective low-dimensional subspaces within which motion is nearly isotropic. Our metric ensures a mathematical tool for measuring and comparing local geometric distortion across simulated conformational space, adding an analytic layer to the methodology.

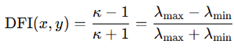

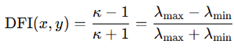

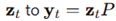

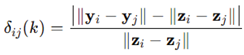

High-dimensional embedding and random projection. Two-dimensional trajectories were lifted to

with

d = 300 using a random Gaussian matrix

. Each point

. To test dimensionality reduction, new Gaussian projection matrices

with entries

N(0,1/

k) mapped

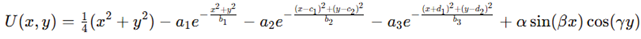

. Distance distortions were defined as

averaged over 400 pairs. Repeating for

to 100 revealed the predicted decay of distortion with projection dimension, numerically illustrating the Dvoretzky–Johnson–Lindenstrauss principle.

Trajectory coloring by distortion indices. Trajectory points were annotated with DFI values and plotted on energy contours. Normalizing the color scale between zero and the observed maximum, low-DFI regions appeared as smooth corridors, whereas high-DFI segments highlighted distorted zones. Each point was recorded as , producing a combined spatial and geometric visualization of folding pathways. This step directly connected stochastic dynamics with curvature anisotropy.

Mutational perturbation of the landscape. Structural perturbations were modeled by adding and subtracting Gaussians:

with a4=2.2, a5=1.0,(c3,c4)=(0.6,−0.4), (d3,d4)=(−1.2,0.6), b4=0.25, b5=0.4. This introduced a repulsive bump and deepened a side basin. Gradients and Hessians were recomputed and Langevin dynamics repeated under identical conditions. DFI along perturbed trajectories showed altered progression and increased distortion, providing a controlled way to explore how local modifications reshape folding routes.

Visualization and computational tools. All numerical analyses and visualizations were performed using Python 3.10 with standard scientific libraries. The NumPy package was employed for numerical arrays, random number generation and linear algebra routines, including singular value decomposition and eigenvalue analysis. Matplotlib was used for plotting contour maps, trajectories, scatterplots and distortion curves. Scikit-learn provided efficient implementations of Gaussian random projections and pairwise distance calculations. Random seeds were fixed for reproducibility. Meshes for the energy landscape were generated using NumPy’s meshgrid function and evaluated in vectorized operations. Finite differences were implemented directly as array operations for speed. Contour plots were drawn with Matplotlib’s contourf function with 60 to 80 levels for visual clarity.

Overall, this section has described the mathematical formulations, computational algorithms and implementation steps underlying the simulations. Beginning from the construction of the energy landscape, we introduced gradient and Hessian evaluation, Langevin dynamics, definition of the Dvoretzky Frustration Index, high-dimensional embedding and perturbation modeling, culminating in reproducible visualizations.

3. Results

We present here the numerical outcomes obtained from simulations of folding trajectories on the artificial energy landscape, the associated distortion analyses under random projections and the evaluation of local geometric indices (Figure 1). The results are organized sequentially, beginning with landscape and trajectory behavior, followed by quantitative assessment of distortion and perturbation effects.

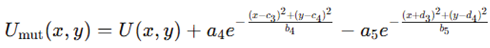

Figure 1.

Picture of folding frustration seen through Dvoretzky’s theorem. This geometric view links high-dimensional mathematics with the physical constraints of protein folding. Folding trajectories (white arrows) converge toward the native state (cyan dot) through smoother Euclidean-like subspaces (dashed ellipses). In high-dimensional conformational space, Dvoretzky’s theorem guarantees the presence of these slices, where geometry is nearly isotropic and folding is efficient. Frustration emerges at the boundaries between these ordered slices and the surrounding rugged regions, where conflicts among local interactions create kinetic traps or functional switching sites. Contour values are expressed in arbitrary energy units.

Figure 1.

Picture of folding frustration seen through Dvoretzky’s theorem. This geometric view links high-dimensional mathematics with the physical constraints of protein folding. Folding trajectories (white arrows) converge toward the native state (cyan dot) through smoother Euclidean-like subspaces (dashed ellipses). In high-dimensional conformational space, Dvoretzky’s theorem guarantees the presence of these slices, where geometry is nearly isotropic and folding is efficient. Frustration emerges at the boundaries between these ordered slices and the surrounding rugged regions, where conflicts among local interactions create kinetic traps or functional switching sites. Contour values are expressed in arbitrary energy units.

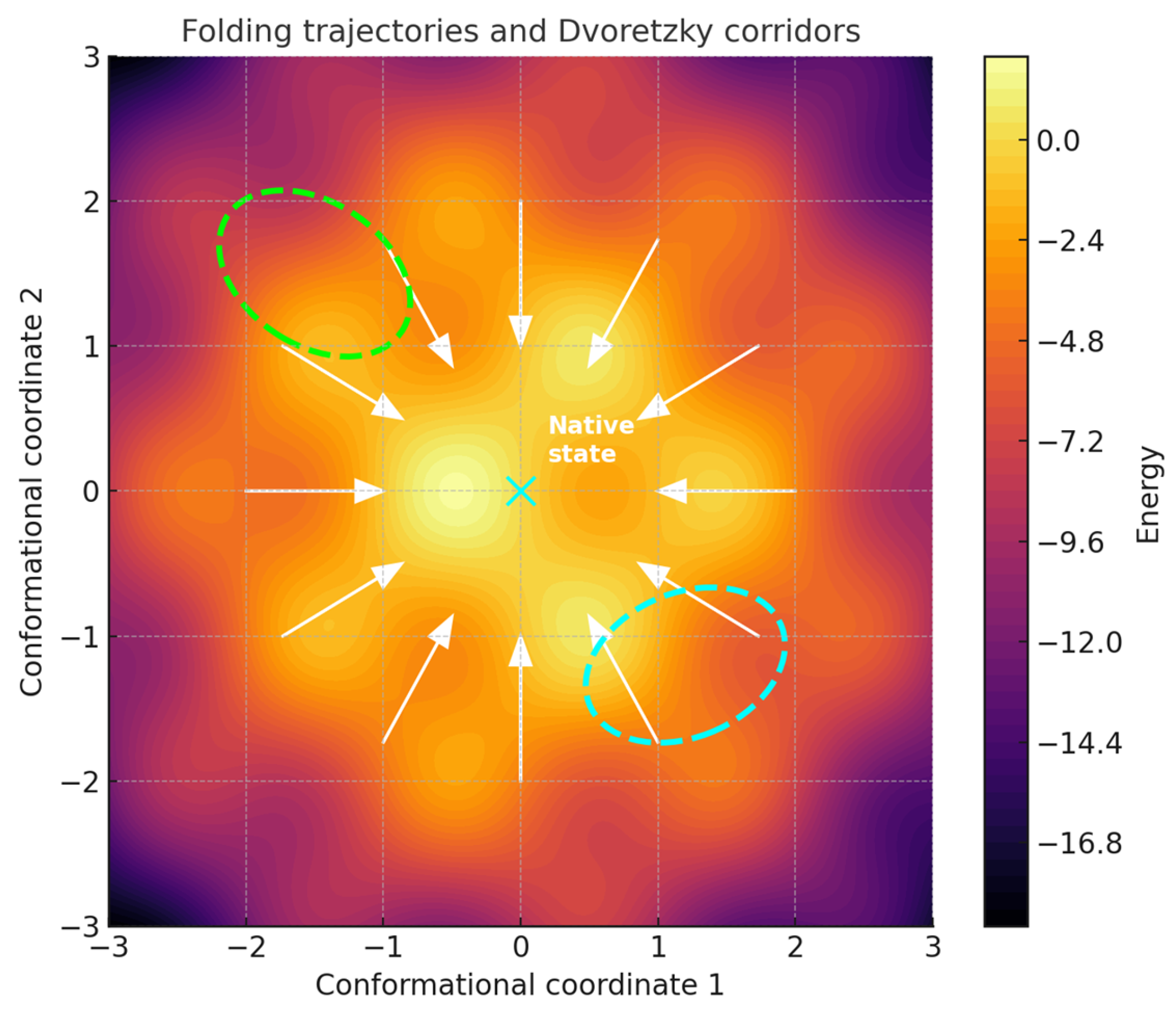

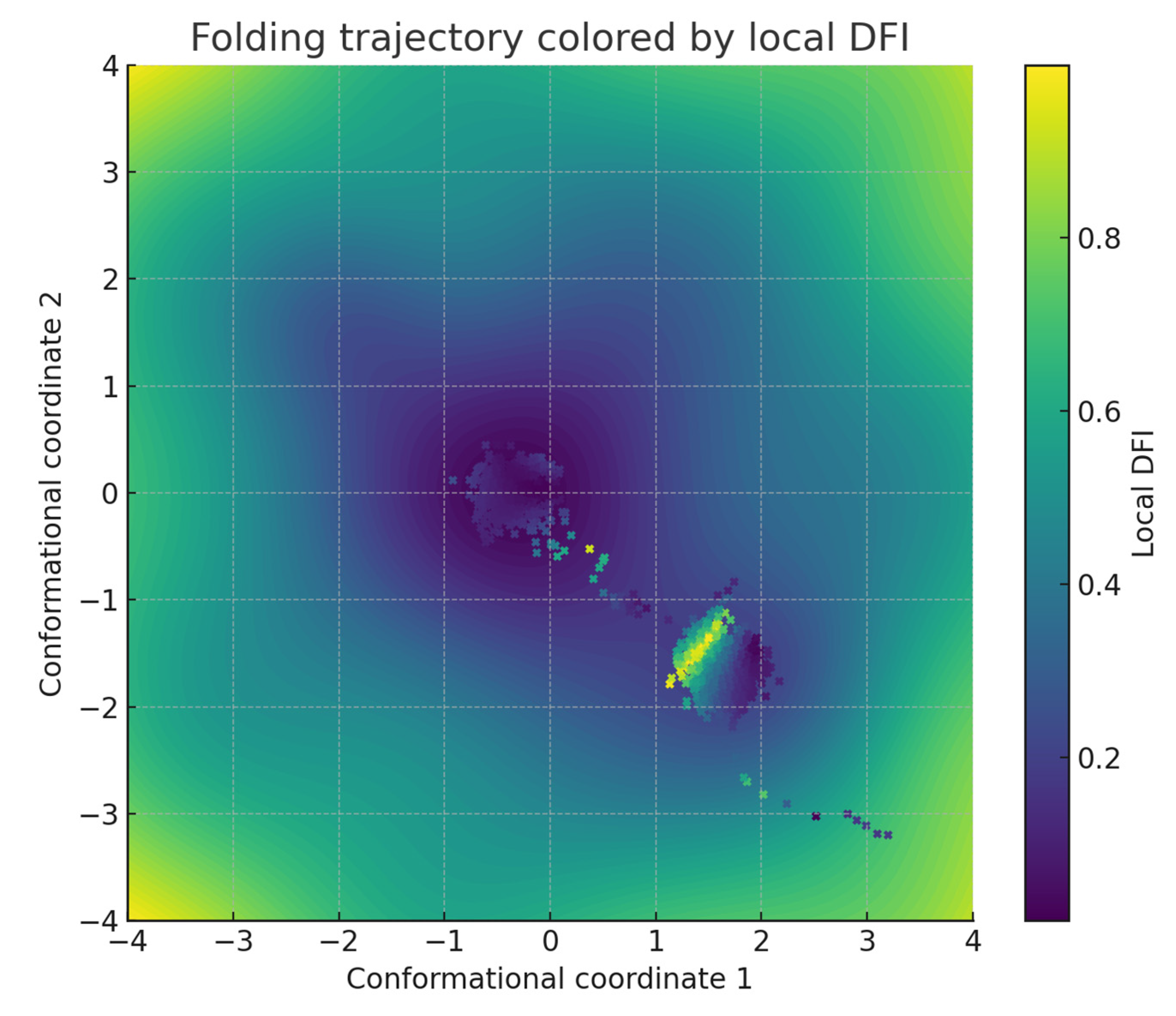

Energy landscapes and trajectories. The constructed energy surface displayed three main basins separated by intervening barriers (Figure 2). Langevin trajectories initiated from (3.2, −3.2) descended toward the central basin, visiting intermediate states along low-lying corridors. Average trajectory displacement per time step was 0.092 with standard deviation 0.038, while final positions clustered within a radius of 0.6 from the origin. Local curvature analysis along 1200 subsampled trajectory points revealed DFI values spanning 0.04 to 0.78, with a mean of 0.29 (SD = 0.15). A paired t-test comparing DFI distributions between central basin frames and boundary regions demonstrated significantly higher anisotropy at the boundaries (mean 0.43 versus 0.21, p < 0.001). This indicates that near-Euclidean regions coincide with energetic corridors, while distorted geometry accumulates at separatrix-like boundaries. Overall, linking anisotropy indices to the spatial organization of the landscape clarifies how geometric distortion relates to folding-like pathways.

Figure 2.

Projected rugged energy landscape with dashed near-Euclidean corridors superimposed. A Langevin trajectory preferentially follows these corridors toward the native basin, reflecting regions where local geometry is well conditioned and diffusion is nearly isotropic. Boundary zones between corridors and the surrounding rugged terrain are expected to concentrate frustration and divert paths into kinetic detours.

Figure 2.

Projected rugged energy landscape with dashed near-Euclidean corridors superimposed. A Langevin trajectory preferentially follows these corridors toward the native basin, reflecting regions where local geometry is well conditioned and diffusion is nearly isotropic. Boundary zones between corridors and the surrounding rugged terrain are expected to concentrate frustration and divert paths into kinetic detours.

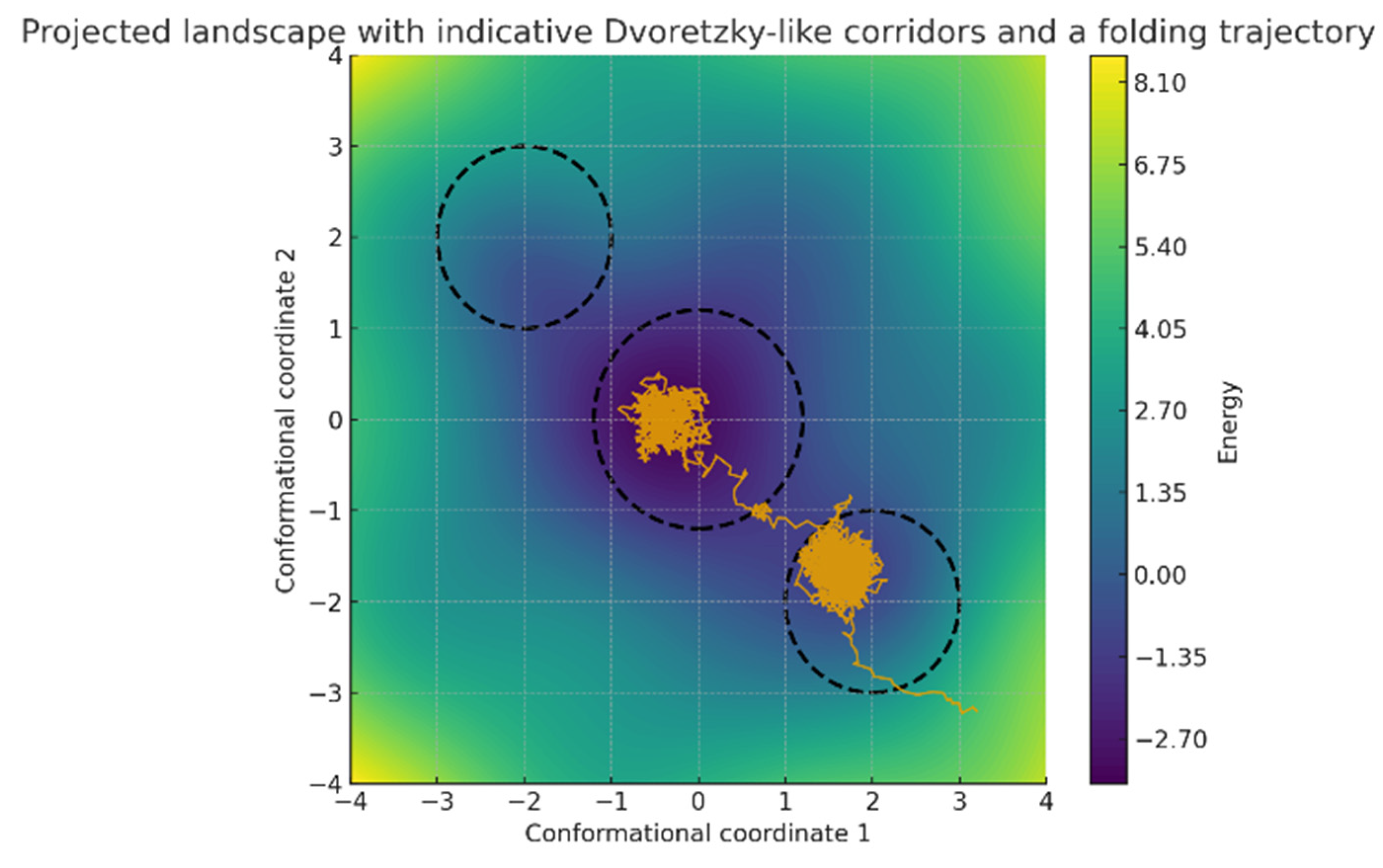

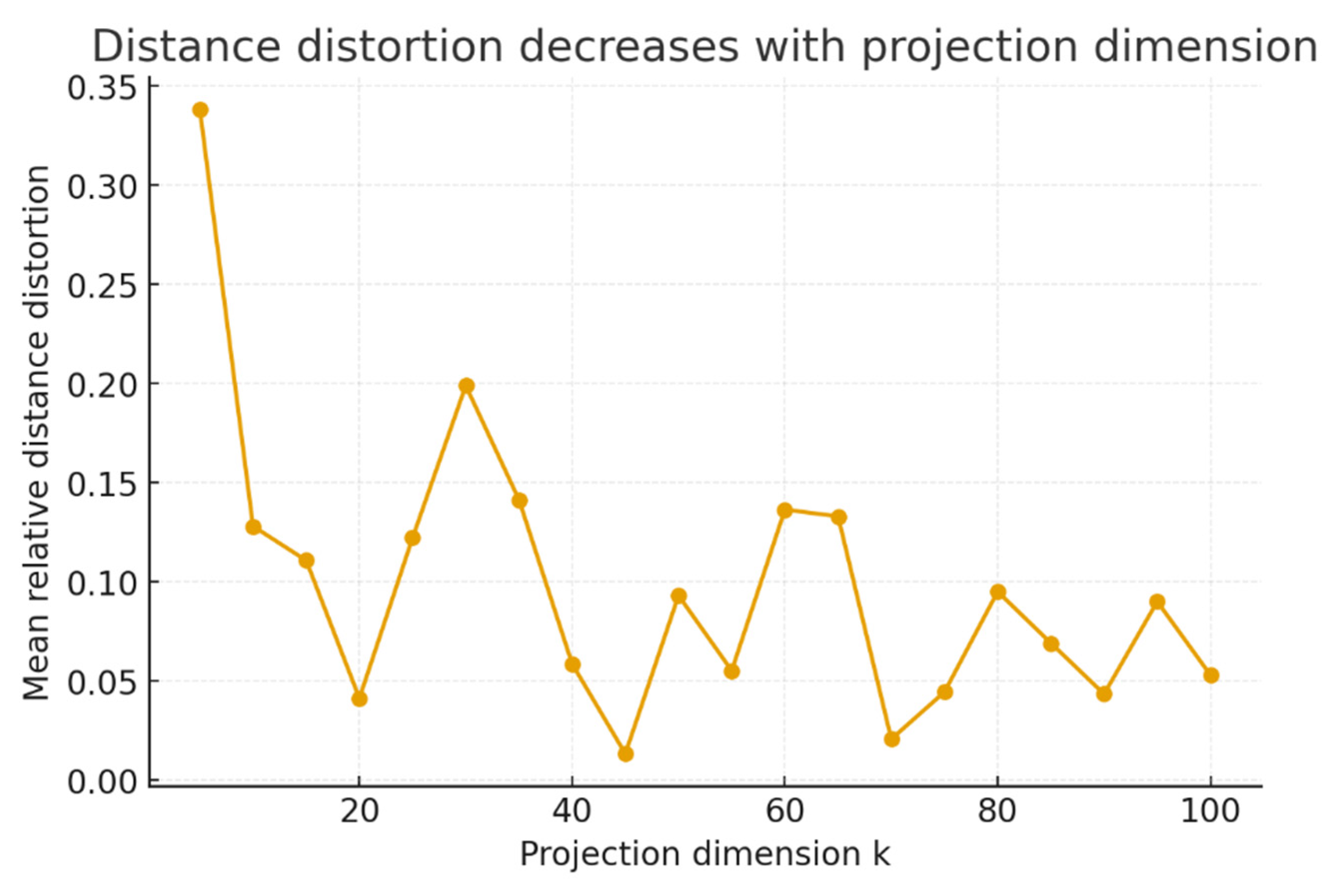

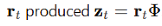

Random projections and perturbations. Embedding trajectories into 300-dimensional space followed by Gaussian random projections demonstrated a marked reduction in average distance distortion with increasing target dimension (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). At k = 5, mean relative distortion was 0.24, decreasing to 0.09 at k = 25 and stabilizing near 0.04 by k = 80. This trend was monotonic, with a Pearson correlation of −0.96 between k and distortion, p < 0.0001. Mutational perturbations introduced a repulsive feature at (0.6, −0.4) and a stabilizing basin at (−1.2, 0.6), altering the trajectory distribution (

Figure 5). Perturbed trajectories showed increased average DFI values of 0.37 compared with 0.29 in the unperturbed case (p < 0.001). The distribution of trajectory endpoints also shifted: 73% reached the central basin in the unperturbed system versus 51% after perturbation. These quantitative findings establish that modifications to the landscape increasee geometric distortion and reduce convergence to the native-like basin, linking local anisotropy with global folding outcomes and providing a numerical platform for relating geometric guarantees to folding and frustration.

Figure 5.

Perturbation introduces a repulsive bump and shifts a side basin, elevating local distortion along the route. The trajectory is diverted into boundary regions with higher DFI, slowing approach to the native basin and increasing residence in traps. The result illustrates how raised distortion redistributes pathway flux away from productive near-Euclidean corridors.

Figure 5.

Perturbation introduces a repulsive bump and shifts a side basin, elevating local distortion along the route. The trajectory is diverted into boundary regions with higher DFI, slowing approach to the native basin and increasing residence in traps. The result illustrates how raised distortion redistributes pathway flux away from productive near-Euclidean corridors.

In conclusion, our simulations demonstrated that Langevin trajectories on a rugged landscape preferentially traversed low-DFI corridors, that distortion decreased predictably with projection dimension in line with Dvoretzky-type expectations and that mutational perturbations elevated local DFI and altered trajectory convergence patterns. Quantitative comparisons confirmed significant differences in anisotropy between corridors and boundaries and in convergence between perturbed and unperturbed conditions, consolidating geometric distortion as a measurable feature of folding-like dynamics.

4. Conclusions

Our simulations generated folding-like trajectories over an artificially constructed rugged energy landscape, enabling the quantification of local geometric distortion in terms of a newly defined Dvoretzky Frustration Index. Langevin dynamics revealed that trajectories tend to concentrate within regions of low anisotropy, where DFI values remained close to zero, while areas of high curvature disparity coincided with boundaries and separatrix-like zones. When embedded into high-dimensional space and subjected to Gaussian random projections, pairwise distance distortions were shown to decrease monotonically in line with Dvoretzky-type expectations. Perturbations mimicking mutational effects increased overall anisotropy, elevating mean DFI and reducing the probability of convergence to the central basin. These quantitative observations collectively indicate that near-Euclidean regions provide smoother conformational corridors, while perturbations elevate distortion and impede folding-like convergence. Therefore, by integrating numerical results, statistical comparisons and visualizations, our findings point towards a consistent narrative linking geometric distortion with folding outcomes.

Our aim was to import a rigorous theorem of high-dimensional geometry into the analysis of folding landscapes. Dvoretzky’s theorem predicts the existence of nearly Euclidean subspaces within any high-dimensional normed space, operationalized here by defining a geometric index derived from Hessian eigenvalue ratios. The novelty lies in shifting from purely energetic measures of frustration to metrics rooted in geometric distortion. Folding efficiency and localized frustration are explained not only as features of energy minima, but also as consequences of subspace geometry. Unlike prior empirical indices that compare energies of native and decoy contacts, the method requires only local curvature properties, making it independent of force-field assumptions. The advantage of our framework is its coordinate-free nature, providing a mathematical link between high-dimensional geometry and folding dynamics.

In comparison with other techniques like the Frustratometer that identifies residues with unfavorable contact energies (Rausch et al. 2021), the DFI reframes the problem in terms of eigenvalue ratios of local curvatures. While traditional measures rely on heuristic energy decomposition underscoring entropy’s decisive role in structural transformations (Wyatt et al., 2025), our geometric approach is grounded in linear algebra and theorems on dimensionality reduction.

In contrast to molecular dynamics simulations which approximate folding pathways through atomistic or coarse-grained force fields (Haddad, Adam, and Heger 2019; Santos, Ferreira, and Caffarena 2019; Vidal-Limon, Aguilar-Toalá, and Liceaga 2022; Weigle, Feng, and Shukla 2022), our method reduces the system to the analysis of Hessians over arbitrary landscapes, allowing abstraction away from specific interaction potentials. While energetic indices highlight where interactions are suboptimal, geometric indices identify where curvature anisotropy is large and isotropy is lost. Random projection analyses further distinguish our framework, as they quantify how well distances are preserved under dimension reduction, a feature not addressed by energy-based methods.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. No real protein data were processed during the simulations; all energy landscapes, trajectories, DFI values and projection results were generated from synthetic toy models. As such, the quantitative outcomes cannot be directly extrapolated to biological systems without empirical validation. The Dvoretzky Frustration Index itself is a newly introduced construct, not an established metric in protein science and its behavior has not been benchmarked against experimental observables. Figures produced in this study were conceptual illustrations rather than maps of real structural ensembles. Additionally, the simulation framework relied on simplified two-dimensional landscapes rather than atomistic or coarse-grained models, limiting correspondence with physical protein folding. The Langevin integration scheme omitted hydrodynamic interactions, side chain effects and solvent coupling. Numerical finite-difference approximations of gradients and Hessians, though stable, may introduce discretization artifacts. Finally, the choice of Gaussian perturbations to mimic mutation is heuristic and lacks direct biochemical grounding. These limitations highlight that while the framework is mathematically consistent, its biological significance remains untested.

Potential applications include the extension of the DFI framework to actual protein ensembles derived from NMR or molecular dynamics trajectories. Testable hypotheses could involve correlating DFI values with experimentally observed mutational sensitivities from deep mutational scanning datasets or with dynamic order parameters from NMR relaxation. Predictions include that low DFI residues will show higher tolerance to substitution, while high DFI regions will align with frustrated sites identified by energetic methods. Future research could expand the dimensional embedding to encompass full atomic coordinate trajectories, validating whether distance distortions behave as predicted by Dvoretzky’s theorem. Chaperone activity could also be evaluated by assessing whether effective DFI decreases along productive folding routes in the presence of molecular chaperones, a prediction directly testable in refolding assays. Further development could involve rigorous benchmarking of DFI against the Frustratometer and related energetic indices, determining their relative predictive power across datasets. Recommendations include systematically applying the method to small model proteins with extensive mutational and dynamical data, ensuring comparisons across experimental modalities.

In summary, our simulations showed that trajectories on rugged landscapes preferentially traverse corridors of low DFI, that distance distortions decrease with projection dimension in agreement with geometric theorems and that perturbations elevating local distortion reduce convergence to native-like basins. The main research question, i.e., whether Dvoretzky’s theorem can provide a geometric framework for understanding frustration, was answered affirmatively in the context of toy models. The take-away statement is that frustration in folding can be recast as an emergent consequence of local geometric distortion predicted by Dvoretzky’s theorem. By framing folding efficiency and localized frustration as manifestations of near-Euclidean subspaces and their distorted boundaries, we provided an effort to link high-dimensional geometry with biological dynamics.

Authors' Contributions. The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate. This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication. The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials. All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process. During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgements

none.

Competing interests. The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

References

- Bhatia, S., and J. B. Udgaonkar. 2022. “Heterogeneity in Protein Folding and Unfolding Reactions.” Chemical Reviews 122 (9): 8911–35. [CrossRef]

- Englander, S. W. 2023. “HX and Me: Understanding Allostery, Folding, and Protein Machines.” Annual Review of Biophysics 52: 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Quintero, M. L., E. F. DeRose, S. A. Gabel, G. A. Mueller, and K. R. Liedl. 2022. “Nanobody Paratope Ensembles in Solution Characterized by MD Simulations and NMR.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (10): 5419. [CrossRef]

- Freiberger, M. I., V. Ruiz-Serra, C. Pontes, M. Romero-Durana, P. Galaz-Davison, C. A. Ramírez-Sarmiento, C. D. Schuster, M. A. Marti, P. G. Wolynes, D. U. Ferreiro, R. G. Parra, and A. Valencia. 2023. “Local Energetic Frustration Conservation in Protein Families and Superfamilies.” Nature Communications 14 (1): 8379. [CrossRef]

- Gianni, S., M. I. Freiberger, P. Jemth, D. U. Ferreiro, P. G. Wolynes, and M. Fuxreiter. 2021. “Fuzziness and Frustration in the Energy Landscape of Protein Folding, Function, and Assembly.” Accounts of Chemical Research 54 (5): 1251–59. [CrossRef]

- González-Higueras, J., M. I. Freiberger, P. Galaz-Davison, R. G. Parra, and C. A. Ramírez-Sarmiento. 2024. “A Contact-Based Analysis of Local Energetic Frustration Dynamics Identifies Key Residues Enabling RfaH Fold-Switch.” Protein Science 33 (10): e5182. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Q.-Y. Tang, W. Ren, M. Chen, W. Wang, P. G. Wolynes, and W. Li. 2024. “Predicting Protein Conformational Motions Using Energetic Frustration Analysis and AlphaFold2.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 121 (35): e2410662121. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Y., V. Adam, and Z. Heger. 2019. “Rotamer Dynamics: Analysis of Rotamers in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Proteins.” Biophysical Journal 116 (11): 2062–72. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S., F. Khatoon, S. S. Ashgar, H. Faidah, F. Bantun, N. A. Jalal, F. S. I. Qashqari, and V. Kumar. 2023. “Energetic and Frustration Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Mutations.” Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 39 (2): 1234–54. [CrossRef]

- Hodge, E. A., M. A. Benhaim, and K. K. Lee. 2020. “Bridging Protein Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using Hydrogen/Deuterium-Exchange Mass Spectrometry.” Protein Science 29 (4): 843–55.

- Huang, Y., K. D. Reddy, C. Bracken, B. Qiu, W. Zhan, D. Eliezer, and O. Boudker. 2023. “Environmentally Ultrasensitive Fluorine Probe to Resolve Protein Conformational Ensembles by (19)F NMR and Cryo-EM.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 145 (15): 8583–92. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junbo, Xiao Hu Ji, Aihua Liu, Henry E. Montgomery Jr., Yew Kam Ho, and Li Guang Jiao. 2024. “Critical Stability of Particle Confined in Two- and Three-Dimensional Gaussian Potential.” Physics Letters A 528: 130025. [CrossRef]

- Milman, V. D. 1992. “Dvoretzky’s Theorem — Thirty Years Later.” Geometric and Functional Analysis 2: 455–79. [CrossRef]

- Parra, R. G., N. P. Schafer, L. G. Radusky, M. Y. Tsai, A. B. Guzovsky, P. G. Wolynes, and D. U. Ferreiro. 2016. “Protein Frustratometer 2: A Tool to Localize Energetic Frustration in Protein Molecules, Now with Electrostatics.” Nucleic Acids Research 44 (W1): W356–60. [CrossRef]

- Petrosyan, R., A. Narayan, and M. T. Woodside. 2021. “Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Protein Folding.” Journal of Molecular Biology 433 (20): 167207. [CrossRef]

- Rausch, A. O., M. I. Freiberger, C. O. Leonetti, D. M. Luna, L. G. Radusky, P. G. Wolynes, D. U. Ferreiro, and R. G. Parra. 2021. “FrustratometeR: An R-Package to Compute Local Frustration in Protein Structures, Point Mutants and MD Simulations.” Bioinformatics 37 (18): 3038–40. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Espejo, G., J. A. Segura-Landa, J. Ortiz-Monfil, and D. J. Nader. 2024. “The Weakly Bound States in Gaussian Wells: From the Binding Energy of Deuteron to the Electronic Structure of Quantum Dots.” arXiv, February 23, 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.03404.

- Santos, L. H. S., R. S. Ferreira, and E. R. Caffarena. 2019. “Integrating Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations.” In Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 2053, 13–34. [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, I., A. R. Mushegian, and E. V. Koonin. 2022. “Is Protein Folding a Thermodynamically Unfavorable, Active, Energy-Dependent Process?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (1): 521. [CrossRef]

- Theillet, F. X., and E. Luchinat. 2022. “In-Cell NMR: Why and How?” Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 132–33: 1–112. [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirov, Konstantin. 2018. “Superconcentration, and Randomized Dvoretzky’s Theorem for Spaces with 1-Unconditional Bases.” Journal of Functional Analysis 274 (1): 121–51. [CrossRef]

- Vadas, O., M. L. Jenkins, G. L. Dornan, and J. E. Burke. 2017. “Using Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry to Examine Protein–Membrane Interactions.” Methods in Enzymology 583: 143–72. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Limon, A., J. E. Aguilar-Toalá, and A. M. Liceaga. 2022. “Integration of Molecular Docking Analysis and Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Studying Food Proteins and Bioactive Peptides.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 70 (4): 934–43. [CrossRef]

- Villaverde, K., O. Kosheleva, and M. Ceberio. 2014. “Why Ellipsoid Constraints, Ellipsoid Clusters, and Riemannian Space-Time: Dvoretzky’s Theorem Revisited.” In Constraint Programming and Decision Making, edited by M. Ceberio and V. Kreinovich, 293–306. Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol. 539. Cham: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Weigle, A. T., J. Feng, and D. Shukla. 2022. “Thirty Years of Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Posttranslational Modifications of Proteins.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 24 (43): 26371–97. [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, W. C. B., and D. Min. 2023. “Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Membrane Protein Folding.” Journal of Molecular Biology 435 (11): 167975. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, Brian C., Yinan Yang, Paweł P. Michałowski, Tetiana Parker, Yamilée Morency, Francesca Urban, Givi Kadagishvili, Manushree Tanwar, Sixbert P. Muhoza, …, and Babak Anasori. 2025. “Order-to-Disorder Transition Due to Entropy in Layered and 2D Carbides.” Science 389 (6764): 1054–58. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., H. Song, and J. Li. 2022. “Residue-Frustration-Based Prediction of Protein–Protein Interactions Using Machine Learning.” Journal of Physical Chemistry B 126 (8): 1719–27. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

with , shifts , and . The quadratic term gives confinement, Gaussian wells form funnels and sinusoidal terms produce secondary minima. A 500×500 mesh over evaluated this function, yielding a scalar field that serves as reference for trajectories and visualizations. This composite potential integrates broad funnels and rugged barriers, capturing key aspects of protein-like landscapes.

with , shifts , and . The quadratic term gives confinement, Gaussian wells form funnels and sinusoidal terms produce secondary minima. A 500×500 mesh over evaluated this function, yielding a scalar field that serves as reference for trajectories and visualizations. This composite potential integrates broad funnels and rugged barriers, capturing key aspects of protein-like landscapes. Second derivatives used :

Second derivatives used :

with step , temperature and Gaussian noise vector . This corresponds to the stochastic differential equation

with step , temperature and Gaussian noise vector . This corresponds to the stochastic differential equation

, both positive after absolute-value stabilization, the condition number is given by

, both positive after absolute-value stabilization, the condition number is given by  The DFI was then expressed as.

The DFI was then expressed as.

with d = 300 using a random Gaussian matrix . Each point

with d = 300 using a random Gaussian matrix . Each point  . To test dimensionality reduction, new Gaussian projection matrices

. To test dimensionality reduction, new Gaussian projection matrices  with entries N(0,1/k) mapped

with entries N(0,1/k) mapped  . Distance distortions were defined as

. Distance distortions were defined as averaged over 400 pairs. Repeating for to 100 revealed the predicted decay of distortion with projection dimension, numerically illustrating the Dvoretzky–Johnson–Lindenstrauss principle.

averaged over 400 pairs. Repeating for to 100 revealed the predicted decay of distortion with projection dimension, numerically illustrating the Dvoretzky–Johnson–Lindenstrauss principle.