Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

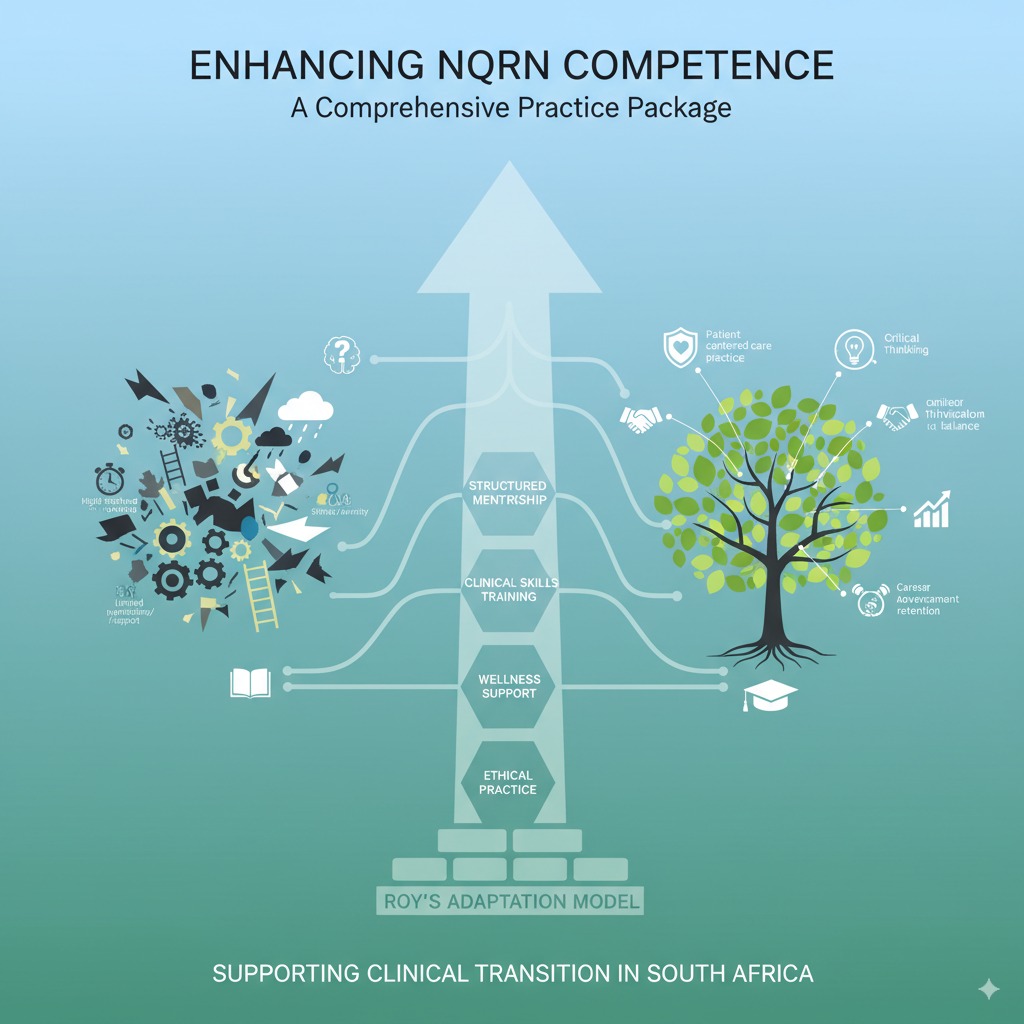

Background: Transitioning from nursing education to independent clinical practice is a critical and often challenging period for newly qualified registered nurses (NQRNs). During this phase, NQRNs frequently face high workloads, limited mentorship, stress, and gaps in clinical competence, which can affect both patient care and nurse retention. Structured support systems are therefore essential to foster competence, resilience, and professional growth. Aim: This study explored transition challenges of NQRNs and proposed a structured competency package to enhance clinical practice and professional development. Methods: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods design was used. In the quantitative phase, 272 NQRNs from Chris Hani District completed a survey on training, mentorship, workload, stress, continuing education, and leadership. In the qualitative phase, 25 purposively selected participants joined three focus group discussions exploring lived experiences and support needs. Data were analysed using SPSS for descriptive and inferential statistics and Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic framework, with ethical approval and trustworthiness ensured through standard qualitative rigor. Results: Findings indicated that many NQRNs experienced only moderate satisfaction with their transition support, high stress levels, and feelings of being overwhelmed by workload. Mentorship effectiveness was perceived as inconsistent, whereas the importance of continuing education and professional development was rated highly. Conclusions: The study informed a structured, stage-based competency package combining skills training, mentorship, critical thinking, communication, ethical practice, resilience support, and continuous assessment. This holistic framework aims to enhance clinical competence, confidence, and adaptive capacity among NQRNs, supporting safe, patient-centred care and long-term workforce retention.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Physiological-physical mode – meeting basic needs and developing skills to function effectively.

- Self-concept mode – building confidence, self-esteem, and professional identity.

- Role function mode – clarifying professional responsibilities and expectations.

- Interdependence mode – fostering supportive relationships and teamwork.

1.1. Aim

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Quantitative Phase

2.2.1. Sample Size, Sampling, and Recruitment

2.2.2. Data Collection Process

2.2.3. Data Analysis

2.3. Qualitative Phase

2.3.1. Participants and Sampling Strategy

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.3.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Results for the Quantitative Study

3.1.1. Descriptive Results

3.1.2. Demographic Profile of Respondents

| Table 1: Variable | Frequencies | Percentage | |

| AGE | 20-24 | 46 | 16.99% |

| 25-29 | 140 | 51.35% | |

| 30-34 | 53 | 19.31% | |

| 35-39 | 21 | 7.72% | |

| 40+ | 13 | 4.63% | |

| GENDER | Male | 116 | 42.64% |

| Female | 155 | 56.98% | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.39% | |

| WORK EXPERIENCE | One Years | 99 | 36.43% |

| Two Years | 52 | 18.99% | |

| Three Years | 121 | 44.57 | |

3.1.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.4. Job Satisfaction

| Table 2: Job satisfaction | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Satisfied are you with your current job | 256 | 2,2461 | ,61833 |

| How often do you feel valued in your role as a NQRN | 258 | 2,1667 | ,64775 |

| Likely are you to recommend your workplace to another NQRN | 258 | 2,1899 | ,73197 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 254 | ||

3.1.5. Training & Support

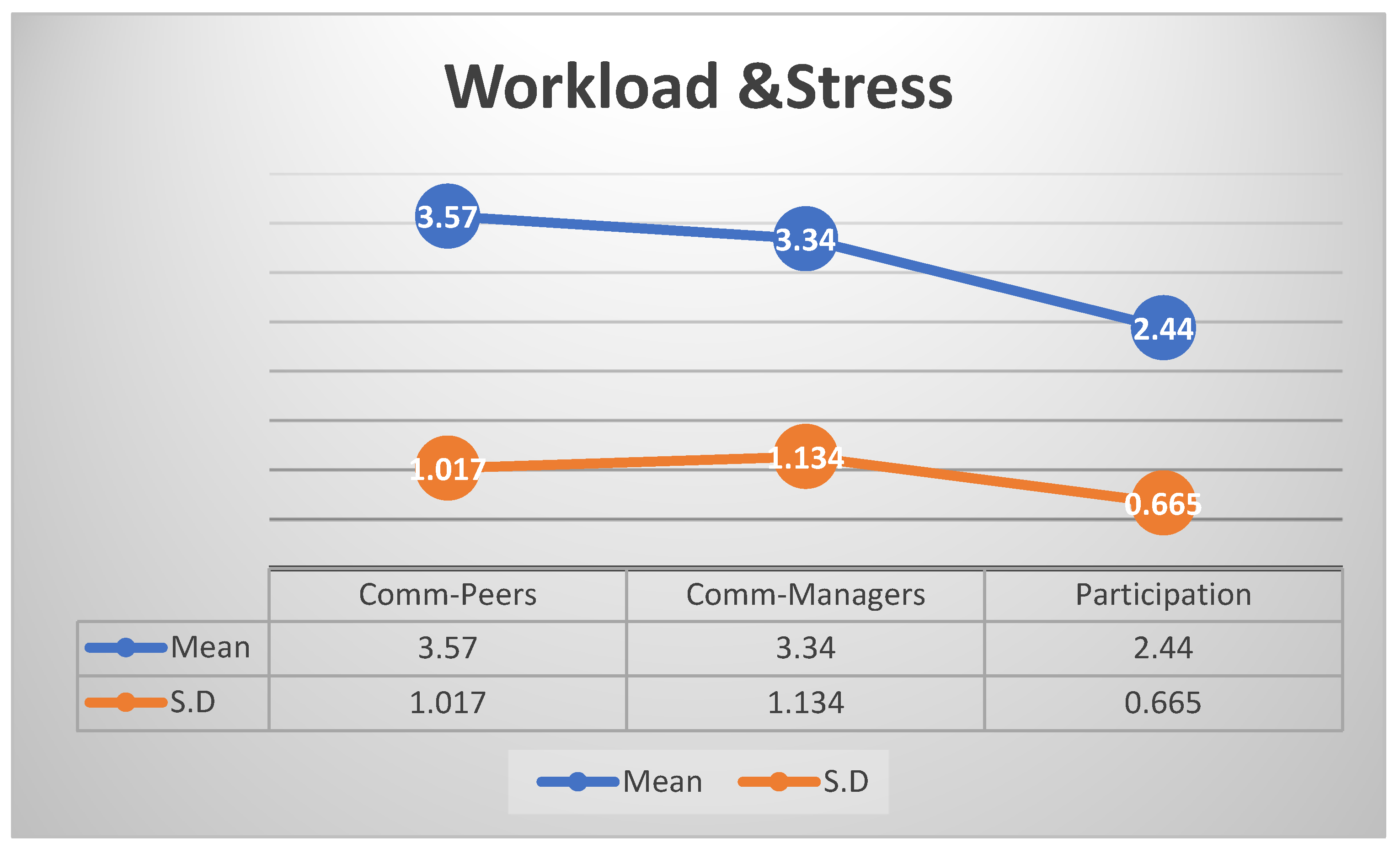

3.1.6. Workload & Stress

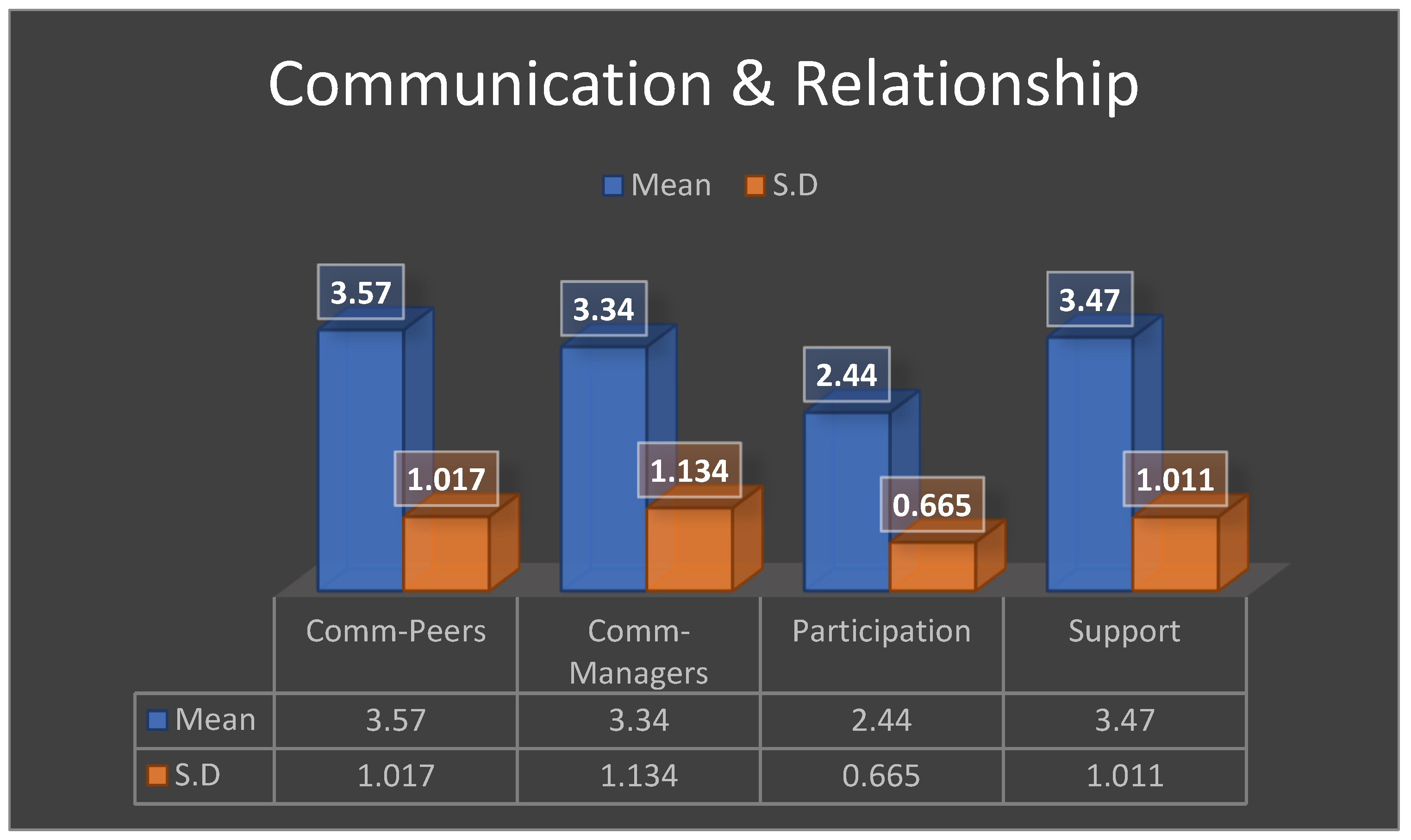

3.1.7. Communication & Relationship

3.1.8. Patient Care

| Table 3: Patient care | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| How confident do you feel in your ability to provide high-quality patient care | 256 | 3,3750 | ,72491 |

| Encounter situations where you feel unprepared to handle a patient’s needs | 256 | 3,1172 | ,75273 |

| Rate the overall quality of patient care provided by your team | 257 | 2,8093 | ,78972 |

| Feel proficient in the technical aspects of patient care | 258 | 3,7016 | ,97042 |

| Manage the nursing care unit | 257 | 3,7821 | ,88344 |

| Make independent decisions when providing nursing care | 257 | 3,7665 | ,91428 |

| Integrate knowledge and skills in clinical practice | 256 | 3,8555 | ,88927 |

| Apply clinical reasoning skills and reflective judgment in the execution of clinical practice | 257 | 3,7510 | ,87514 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 250 | ||

3.1.9. Code of Ethics

| Table 4: Code of Ethics Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Explain procedures and treatments to ensure the patient obtains informed consent | 257 | 4,2335 | ,84315 |

| Maintain the confidentiality of your patient information | 256 | 4,4492 | ,80034 |

| Ensure that patient rights and dignity are respected | 255 | 4,4706 | ,77746 |

| Advocate for patient needs and preferences in your care | 254 | 4,1850 | ,83003 |

| Promoting patient well-being and providing beneficial care | 254 | 4,1969 | ,82968 |

| Adhere to ethical standards and demonstrate integrity | 255 | 4,3373 | ,75555 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 246 | ||

3.1.10. Leadership Skills

| Table 5: Leadership Skills | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| How skilled are you at resolving conflicts | 257 | 3,6459 | ,95765 |

| Delegating tasks to other team members | 256 | 3,6992 | 1,03628 |

| Delegating subordinates who have more experience than you in the unit | 256 | 2,9180 | ,94822 |

| Demonstrate the level of honesty and integrity where there has been maladministration on your part | 257 | 3,9105 | ,84535 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 255 | ||

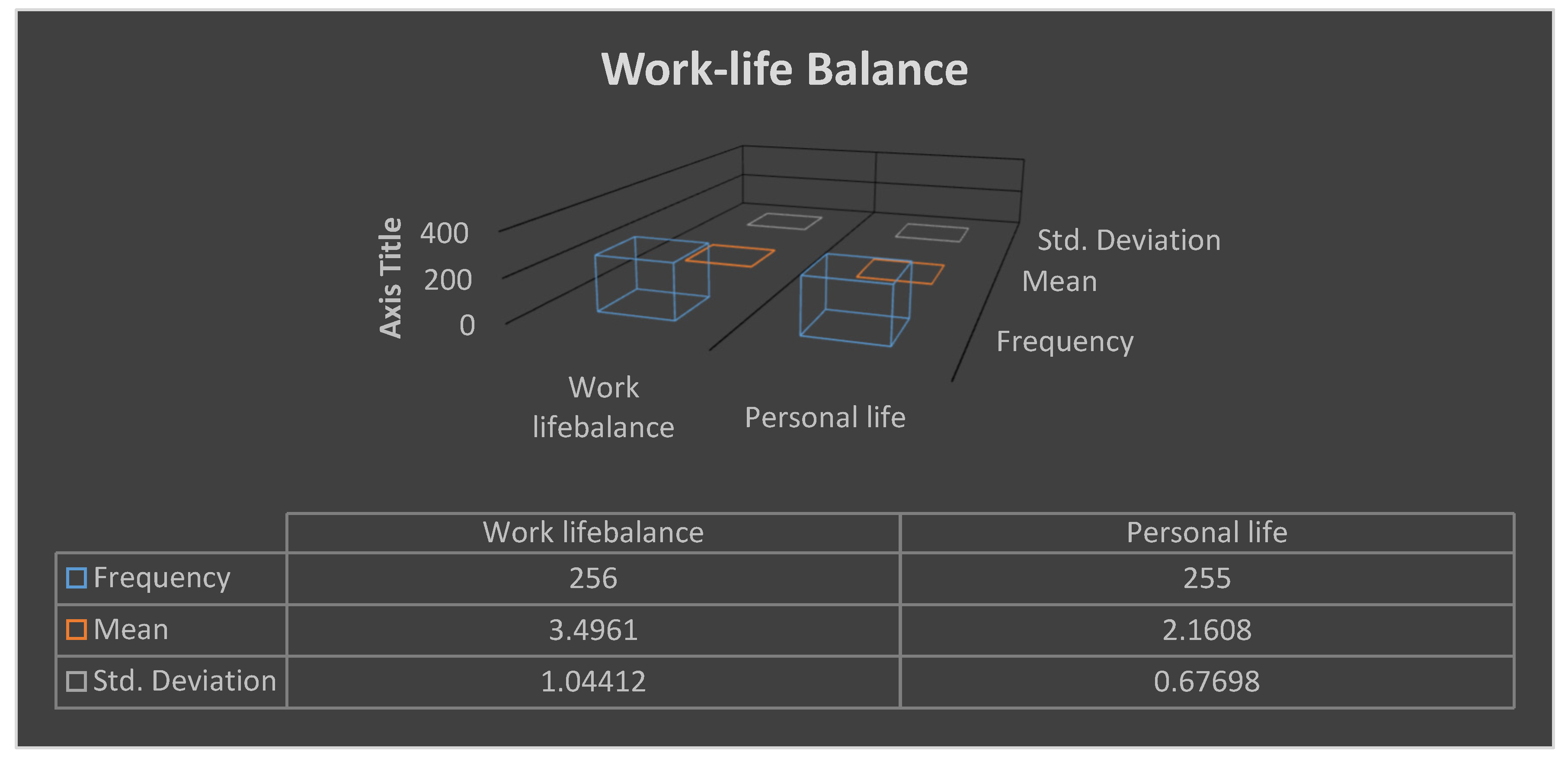

3.1.11. Work-Life Balance

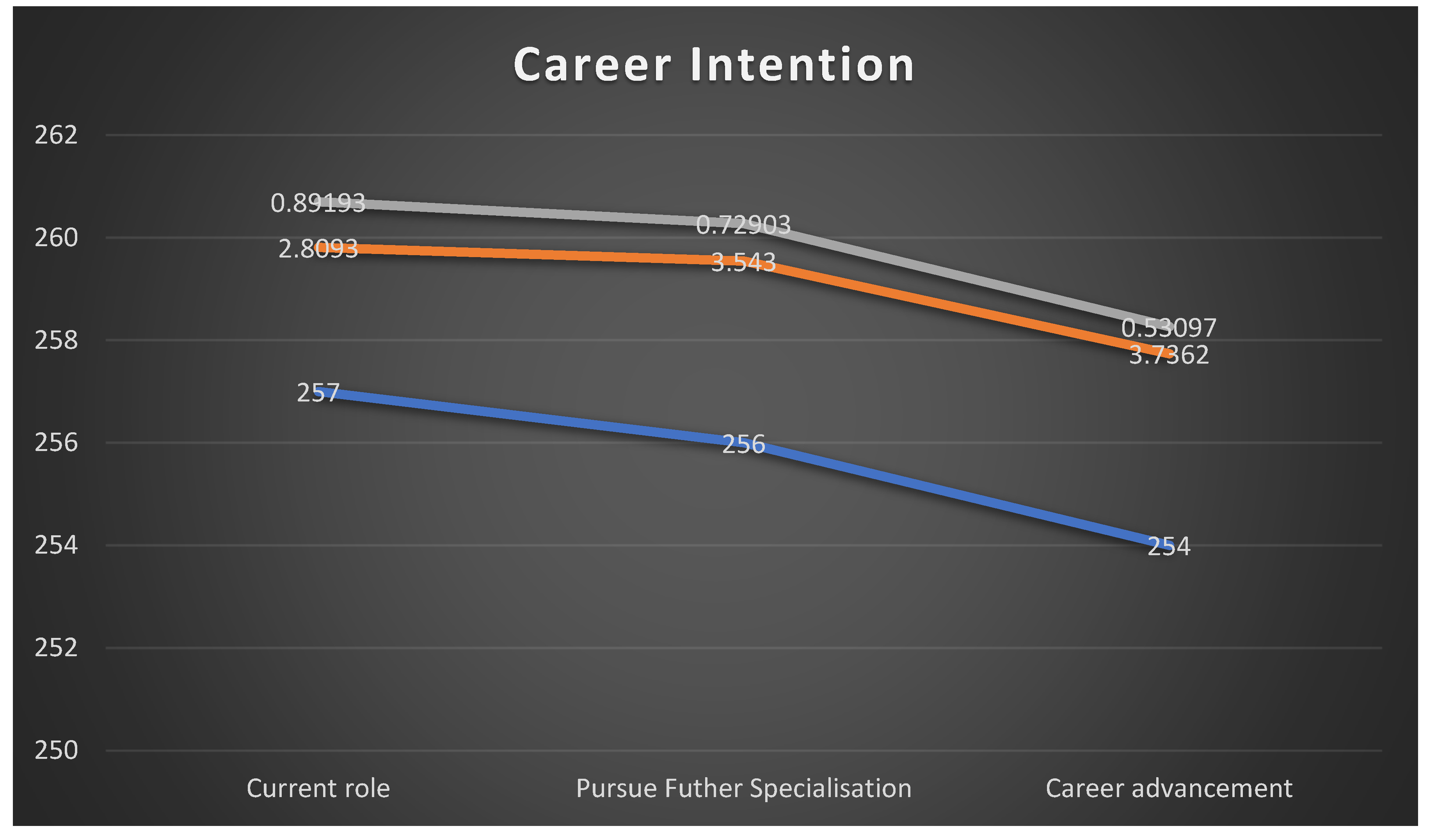

3.1.12. Career Intention

3.2. Results for Qualitative

| Table 8. Demographic profile of participants. | |

| Variable | Frequency |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 15 |

| Age | |

| 24 30 | 7 |

| 30 34 | 9 |

| 35 40 | 5 |

| 40+ | 4 |

| Qualifications | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 12 |

| Comprehensive Diploma | 13 |

| Years of experience | |

| 1- 2 years | 10 |

| 3- 4 years | 8 |

| 5 years | 7 |

| Table 9. Themes and Subthemes of the research findings. | |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|

1.1 Inadequate orientation and supervision |

|

2.1 Ineffective in-service training and skills development. |

|

3.1 Shortage of equipment and staff |

|

4.1.1 Fear and anxiety 4.1.2 Inadequate leadership and emotional support |

|

5.1 High workload stress |

|

6.1 Poor job satisfaction |

3.2.1. Theme 1: An Institutional Void of Clinical Support and Mentorship

“There was no orientation. On my first day, they just showed me the ward and said, ‘This is your ward, these are your patients.’ I was terrified. I had no idea who to ask if I had a problem, because everyone else was just as busy and stressed.”(P1)

“Mentorship is a nice word we read about in textbooks. Here, it doesn’t exist. The senior nurses are either burnt out or they see you as a threat. You learn by making mistakes, and you pray those mistakes don’t harm a patient. It’s a very hard way to learn.”(P3)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Systemic Failures in Management and Leadership

“We had a training session on a new electronic system. They sent one manager, who then was supposed to train all of us. The training never happened properly. It’s always like that. Opportunities for skills development are there, but they don’t reach the people who actually need them on the ground.”(P7)

“When there’s a critical incident, like a patient fall or a medication error, management’s first reaction is to find someone to blame. There is no culture of supportive, non-punitive incident reporting. It makes you afraid to speak up, so problems just get hidden until they become disasters.”(P5)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Crippling Resource Constraints and Infrastructure Decay

“We have one working vital signs machine for a ward of 40-plus patients. You spend half your shift just waiting for the machine. How can you monitor a critically ill patient properly like that? It’s impossible. We are set up to fail.”(P6)

“The staffing is a nightmare. It’s normal to be the only registered nurse for the entire ward at night, with one nursing assistant. You have to do everything admissions, drug rounds, emergencies, paperwork. The patient-to-nurse ratio is not just unsafe; it’s inhumane for both the patient and the nurse.”(P2)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Pervasive Emotional and Psychological Distress

“I have anxiety every single day before I come to work. My stomach is in knots because I’m so scared of what I might face a patient crashing and I’m alone, or a piece of equipment failing during an emergency. It’s a constant state of fear.”(P1)

“It affects your personal life. You go home exhausted, not just physically but emotionally. You are irritable with your family. You can’t sleep because you are replaying everything that happened on your shift, thinking about what you could have done differently if only you had more time or more help.”(P2)

“The emotional toll is immense. I’ve seen so much trauma and there’s no one to talk to about it. There’s no debriefing, no counselling. You are just expected to be strong and carry on. I have cried in my car after a shift more times than I can count.”(P6)

“They is a huge gap that the managers need to do, to guide and support us, we are dying with stress and workload while they is no support are we getting.”(P13)

3.2.5. Theme 5: A Trajectory Towards Professional Burnout

“I am burnt out. Completely. Some days I feel like a robot, just going through the motions. I don’t feel the same empathy I used to. It’s a defence mechanism, I think. If you feel too much, you won’t survive.”(P6)

“I am actively looking for a way out. Maybe go overseas, or work for a private hospital, or just leave nursing altogether. I love being a nurse, but I can’t sacrifice my own health and sanity for a system that doesn’t care about me.”(P7)

3.2.6. Theme 6: Profound Job Dissatisfaction and Disillusionment

“I am not proud of the nursing care I give most days. I know it’s not my fault, but it’s my name on the patient’s chart. We were trained to be advocates for our patients, to give holistic, high-quality care. What we do here is just task-based crisis management.”(P1)

“Is this what I studied so hard for? To work in these conditions? I feel cheated. I feel like the system has failed me, and in turn, it is failing the patients who depend on us. It’s a deep, deep dissatisfaction.”(P5)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Recommendations

| Table 10. below summarises the package. Comprehensive Support Package for NQRNs to Maximise Clinical Competence. | ||

| Domain | Key Components | Intended Outcomes |

| Mentorship & Preceptorship | Formal pairing with experienced mentors; structured role transitions; regular debriefing | Guided transition, reduced anxiet, enhanced confidence |

| Clinical Skills Development | Simulation training; refreshers on routine procedures; interprofessional teamwork training | Strengthened technical competence, improved patient safety |

| Professional Development | Accredited CPD workshops; online learning access; career pathway support | Ongoing competence growth, career satisfaction, retention |

| Workplace Integration | Orientation programmes; peer support groups; open communication with management | Smooth adjustment, reduced isolation, stronger teamwork |

| Wellness & Work-Life Balance | Stress management training; counselling services; adequate staffing and flexible rostering | Reduced burnout, improved morale and productivity |

| Ethical & Professional Practice | Ethics workshops; advocacy training; safe spaces for ethical dialogue | Reinforced professionalism, patient rights protection |

| Monitoring & Feedback | Competence checklists; mentor/peer evaluations; outcome tracking | Continuous improvement, accountability, evidence-based support |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin PS, Viscardi MK, McHugh MD. Factors influencing job satisfaction of new graduate nurses participating in nurse residency programs: a systematic review. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2014 Oct;45(10):439-50; quiz 451-2.

- Yingnan Z, Ziqi Z, Ting W, Liqin C, Xiaoqing S, Lan X. Transitional Shock in Newly Graduated Registered Nurses From the Perspective of Self-Depletion and Impact on Cognitive Decision-Making: A Phenomenological Study. J Nurs Manag. 2024;6722892.

- Duchscher, J.E.B., 2009. Transition shock: the initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(5), pp.1103-1113.

- Van Rensburg, G.H., Botma, Y. and van der Merwe, A., 2020. Competence of NQRNs from a nursing college. Curationis, 23(3), pp.15-22.

- Nkoane, N.L., Mavundla, T.R. and Van der Merwe, A.S., 2021. The experience of professional nurses working with NQRNs placed for community service in public health facilities in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. Curationis, 44(1), p.a2166.

- Casey, K., Fink, R., Jaynes, C., Campbell, L., Cook, P. and Wilson, V., 2011. Readiness for practice: the senior practicum experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(11), pp.646-652.

- Rush, K.L., Janke, R., Duchscher, J.E., Phillips, R. and Kaur, S., 2019. Best practices of formal new graduate nurse transition programs: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 94, pp.138-154.

- Roy, C., 1976. Introduction to Nursing: An Adaptation Model. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Durbin, D.R., House, S.C., Meagher, E.A. and Rogers, J.G., 2019. The role of mentors in addressing issues of work-life integration in an academic research environment. J Clin Transl Sci, 3(6), pp.302-307.

- Casey, K., Fink, R., Krugman, M. and Propst, J., 2004. The graduate nurse experience. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(6), pp.303-311.

- Kang SY, Kim SS, Kim MJ, Kim KH. Effects of a preceptorship program on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention of new graduate nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2016;46(3):362-72.

- Oshodi TO, Bruneau B, Crockett R, Kinchington F, Nayar S, West E. The nursing work environment and quality of care: Content analysis of comments made by registered nurses responding to the Essentials of Magnetism II scale. Nurs Open. 2019;6(3):878-88.4.

- Woo MW, Kim J, Kim J, Choi M, Choe M, An HY. Workload, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of newly graduated nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2020;50(5):668-80. (Note: Woo et al. 2020 was missing).

- Shields M, Ward M, Scott A. The impact of job satisfaction on the turnover intentions of registered nurses in Australia. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(1):173-84. (Note: Shields et al. 2015 was missing).

- Grace R, George N, Jacob R, Baby U, Thomas J. Professional values of nurses and their relationship with perceived ethical climate. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(4):e12555. (Note: Grace et al. 2017 was missing).

- Olejarczyk JP, Young M. Patient Rights and Ethics. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538279/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).