1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The International Maritime Organization(IMO) strengthened its regulatory measures on greenhouse gas(GHG) reduction and energy efficiency in international shipping at the 83

rd session of the Marine Environment Protection Committee(MEPC 83) held in April 2025. Key outcomes included the adoption of a GHG fuel intensity management framework, the introduction of a differentiated emission trading scheme, and the mandatory real-time reporting of fuel consumption and emissions[

1]. From 2028 onwards, ships will be required to comply with direct measures such as monitoring actual emissions and energy intensity by fuel type and purchasing emission allowances in cases of non-compliance with GHG reduction targets. Furthermore, existing energy efficiency frameworks, including the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index(EEXI), the Carbon Intensity Indicator(CII), and the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan(SEEMP), are expected to be further reinforced.

In response to the tightening of international regulations, enhancing fuel efficiency and optimizing propulsive performance have become essential tasks for ships, both to reduce operating costs and to ensure compliance with environmental requirements. The Controllable Pitch Propeller(CPP), which has been widely applied in modern vessels, is an advanced propulsion system that allows continuous adjustment of blade angle to adapt to diverse operating conditions such as speed, load, and maneuvering demands. The core of the CPP lies in its blade angle adjustment mechanism, which regulates the distance traveled by the propeller through the water per revolution, thereby optimizing propulsion efficiency and maneuverability. Unlike a Fixed Pitch Propeller(FPP), a CPP enables continuous speed control without the limitation of minimum engine RPM, and in emergency stop situations, it can switch immediately from ahead to astern, reducing the stopping distance to nearly half compared with an FPP. Depending on the operational strategy, CPP systems are generally categorized into two modes: the Combination mode and the Fixed mode, each characterized by distinct control philosophies and optimization strategies.[

2,

3,

4]

The Combination Mode is a control strategy that simultaneously adjusts both engine speed(RPM) and propeller pitch to achieve holistic optimization of the engine–propeller system. In this mode, the control system continuously searches for the optimal operating point in real time according to load variations, thereby ensuring that the engine operates within its most efficient range. The Automatic Load Control(ALC) algorithm maintains the target load level based on engine power output and fuel consumption characteristics, while the Programmed Control(PGM) secures rational engine operation according to a pre-defined optimum RPM–pitch map. This multivariable control strategy demonstrates superior performance particularly under conditions of low-speed cruising, where fuel efficiency must be maximized, or in operating environments with frequent load fluctuations[

5,

6].

In contrast, the Fixed Mode is characterized by a simplified control structure in which engine speed is kept constant while propeller pitch alone is adjusted to regulate thrust. Owing to its simplicity, this mode ensures stable and predictable propulsion performance, with the Automatic Speed Control(ASC) algorithm accurately maintaining the target ship speed. Moreover, when a torque-based control strategy is applied, propulsion losses can be minimized even under external disturbances such as waves. Thanks to this stability and predictability, the Fixed Mode is widely adopted as a practical operational solution in situations requiring consistent propulsive power, such as high-speed cruising or long-distance voyages[

7].

1.2. Research Necessity and Hypothesis

Recent studies have primarily focused on individual technological aspects of CPPs, such as engine–propeller matching optimization, multi-objective optimization-based control strategies, and fuel consumption minimization algorithms[

8,

9,

10]. However, comprehensive comparative investigations of efficiency characteristics across different operating modes based on full-scale ship data remain limited.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis: the Combination Mode consistently demonstrates higher transmission and propulsive efficiency across a wide range of load conditions, whereas the Fixed Mode provides relative advantages in terms of speed and fuel efficiency at higher load levels. Therefore, by conducting a comparative analysis of mechanical efficiency, propulsive efficiency, and fuel consumption characteristics of CPP under the two operational modes using training ship operational data, this study aims to provide scientific evidence for effective operational optimization and practical decision-making criteria in the context of the latest IMO regulations.

2. Literature Study

2.1. Comparative Studies on CPP Operating Modes

Research on the performance characteristics of Controllable Pitch Propellers (CPPs) under different operating modes has been primarily conducted through experimental approaches and numerical analyses. Deniz et al. investigated the influence of propeller pitch on propulsion performance using the Self-Propulsion Estimation (SPE) method, and further analyzed propulsive efficiency characteristics with reference to the Wageningen B-series propeller database. Their findings revealed that a higher propeller pitch does not necessarily lead to improved propulsion efficiency, and that the maximum propeller efficiency varies depending on the ship’s advance speed[

11].

Moon et al. conducted a comparative analysis of the performance and exhaust gas characteristics of CPP operating modes using a training ship equipped with a two-stroke diesel engine at Pukyung National University. Through full-scale sea trials under both the Combination Mode and the Constant Mode, it was observed that both engines exhibited superior performance in the Combination Mode, whereas the Constant Mode generally resulted in lower NO

x emissions[

12].

2.2. Studies on Propulsion System Matching Optimization

Optimization of ship–engine–propeller matching is a critical factor that directly influences the overall efficiency of the propulsion system. Wang et al. employed a hybrid PSO–GA algorithm to optimize the matching between ship engines and propellers, and developed a free-surface propeller efficiency optimization model with propeller diameter, angular velocity, pitch ratio, and disk ratio as variables[

13].

Tran et al. proposed a novel approach to address the engine–propeller–hull matching problem under real operating conditions. Their quantitative analysis revealed that, after five years of operation, a total power loss of 21.5% occurred, which was attributed to changes in propeller characteristics (6.5%), engine performance degradation (6.3%), and engine–propeller mismatching (8.7%) [

14].

2.3. Propeller Design and Performance Optimization

Wang et al. developed a marine propeller parameterization model based on Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines (NURBS) for propeller optimization. By utilizing eight parameters and five categories of spanwise parameter distributions, they constructed a model to define hydrofoil and blade geometry. This model was combined with a Gene Expression Programming (GEP)-based hydrodynamic performance evaluation model and the NSGA-II algorithm, resulting in propellers with higher efficiency than the reference propeller[

13].

Gao et al. introduced a novel combinator surface concept for the efficiency optimization of ships equipped with mechanical propulsion systems. Their methodology proved effective in identifying optimal matching points between engines and propellers under diverse operating conditions[

9].

2.4. Propulsive and Transmission Efficiency of Shafting Systems

Propulsion system performance is critically influenced by the shafting arrangement and its components. Halilbeşe experimentally demonstrated that the application of composite drive shafts reduces torsional vibrations and improves transmission efficiency by an average of 2.3% [

15]. Olsen proposed the concept of Energy Coefficients to quantify losses occurring in each component of the propeller–shaft–gearbox system, thereby providing systematic guidelines for shafting design optimization[

16]. Shi et al. further decomposed the energy conversion process into engine efficiency (η

e), shaft and gearbox transmission efficiency (η

s·η

gb), propeller efficiency (η

o·η

r), and hull efficiency (η

h). Their study reported a 1.5–3% reduction in overall propulsion efficiency during operation compared with design values, attributing the loss to transmission efficiency deterioration under off-design conditions[

17]. This research offers practical insights into identifying the causes of efficiency degradation, guiding maintenance intervals, and supporting material selection strategies.

2.5. Studies on Operating Mode Selection Strategies and Optimization

Research on operating mode switching and integrated control strategies has gained increasing attention as a means to enhance the practical applicability of CPP systems. In studies on power management and optimization of marine hybrid propulsion systems, approaches have been proposed that consider not only mode switching but also the entire power flow simultaneously. Fan et al. optimized mode-switching policies for hybrid vessels equipped with multiple power sources (diesel, electric, and battery) under various operational scenarios, and demonstrated through full-scale operation simulations that fuel consumption could be reduced by up to 7%. This study highlights the necessity of integrated control across multiple propulsion sources, including CPP mode switching[

10].

Gao et al. introduced a novel combinator surface concept for ship propulsion efficiency optimization, in which multivariate parameters such as RPM, pitch, and ship speed are modeled on a single surface to enable real-time identification of the optimal operating point. When applied in conjunction with a CFD-based performance prediction model, this integrated control framework achieved, on average, 5.5% higher overall propulsion efficiency compared to conventional Fixed and Combination Modes[

9].

These studies underscore that operating mode selection strategies are a core challenge in CPP systems and provide strong support for the development of real-time mode-switching algorithms utilizing the ηoverall,proxy indicator proposed in this study.

Recent research trends have expanded in scope to encompass complex dynamic simulations, full-scale measurement data, customized optimization of hull–engine–propeller systems, and even integrated optimization that simultaneously considers fuel consumption, environmental impacts, and economic performance. In particular, advanced studies have been reported from a systems-integration perspective, including dynamic optimization of the entire ship powertrain, customized propulsion control, and fuel–emission coupled control strategies.

While most previous studies have focused on either efficiency characteristics of specific operating modes or on individual control algorithms, the distinctiveness of this study lies in its integrated analysis of crossover phenomena in terms of mechanical efficiency, propulsive efficiency, and fuel consumption, based on actual training ship operational data. By utilizing measured data from real operating conditions rather than relying solely on simulations, this study empirically identifies the trade-off structure of efficiency between operating modes and thereby provides a practical foundation for establishing effective operational strategies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Methodolog

This study investigates the propulsion system with a two-stroke diesel main engine installed on HANNARA training ship of National Korea Maritime and Ocean University (KMOU). The principal specifications of the system are provided in

Table 1.

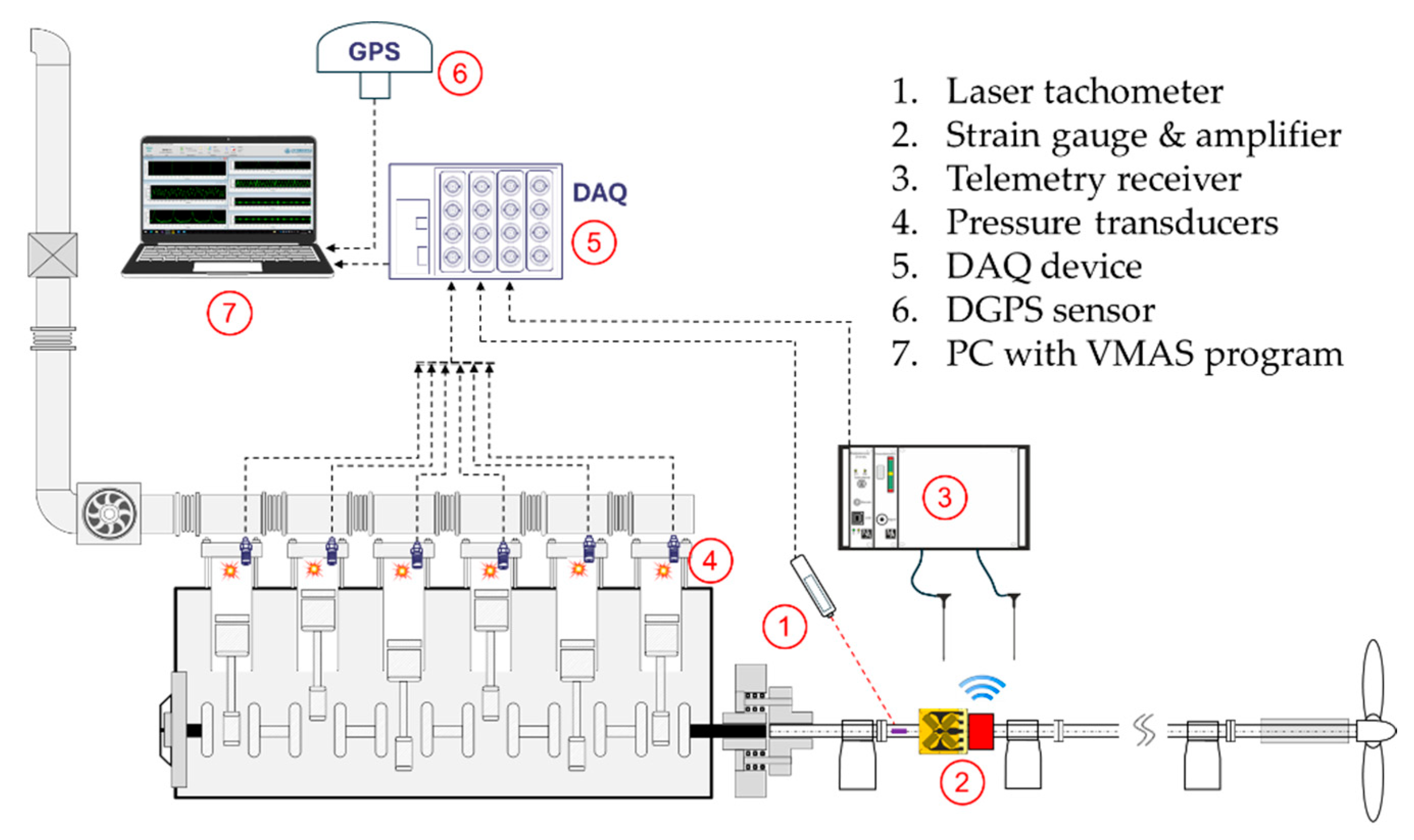

For the purpose of torque and effective power measurements on the intermediate shaft, a strain gauge (model CEA-06-250US-350, Micro-Measurements) was mounted on the shaft surface. Signal transmission from the strain gauge was achieved using a telemetry system supplied by MANNER Sensortelemetrie, consisting of a rotating sensor signal amplifier (model SV_8a) coupled with a stationary receiver unit (model AW_42TE_Fu). The accuracy error is less than . Cylinder pressure signals were obtained from the main engine’s PMI Controller, which is equipped with an ABB PFPL203 combustion pressure transducer on each cylinder. The transducer calibrated measurement range extends from 0 to 250 bar, with combined measurement errors (including sensitivity drift, linearity deviation, and hysteresis) below .

Ship speed was measured using a DGPS sensor (model JLR-4341, JRC) installed on the navigation deck. Shaft rotational speed was determined with a laser tachometer (model A2103/LSR/001, Compact Instruments) in conjunction with a reflective tape indicating the top dead center of cylinder No. 1. All measurement signals were synchronously acquired using a data acquisition system (NI-9174 Chassis with NI-9222 modules, National Instruments), digitized, and processed with VMAS (Vibration Monitoring and Analysis System) program developed by KMOU.

Figure 1 describes the schematic diagram of measurement system. To ensure accurate and reliable detection of all relevant vibration phenomena, a sampling rate of 8192 samples per second was applied.

3.2. Performance Indicators

In this study, six performance indicators shown as

Table 2 were established to quantitatively evaluate the operational characteristics of CPP modes. First, the load ratio (Load) was defined as the ratio of Indicated Horse Power (IHP) to the Maximum Continuous Rating(MCR), representing the relative operating condition of the engine. Fuel efficiency was assessed using the Specific Fuel Consumption (SFC), which was estimated based on the reference value of 173.4 g/kWh (at 100% load, Tier II condition) provided in the engine manual, and its variation with load ratio. Accordingly, Fuel Consumption (FC) was calculated by multiplying IHP with the corresponding load-dependent SFC and converting the value into tons per hour.

For efficiency analysis, the mechanical efficiency (ηmech) was defined as the ratio of shaft power (SHP) to IHP, thereby reflecting the actual output efficiency accounting for internal engine losses. Since direct measurement of propulsive efficiency is challenging, a Relative Propulsive Efficiency Index (RPEI) was introduced. Based on the assumption that effective propulsive power is proportional to the cube of ship speed (V3) under identical hull form, draft, and sea conditions, RPEI was defined as V3/SHP, and normalized (RPEInorm) to a median value of one for mode-to-mode comparison. Finally, the proxy overall efficiency (ηoverall,proxy) was defined as the product of ηmech and RPEInorm, and employed as an integrated performance index that simultaneously reflects both engine and propeller efficiencies.

4. Results

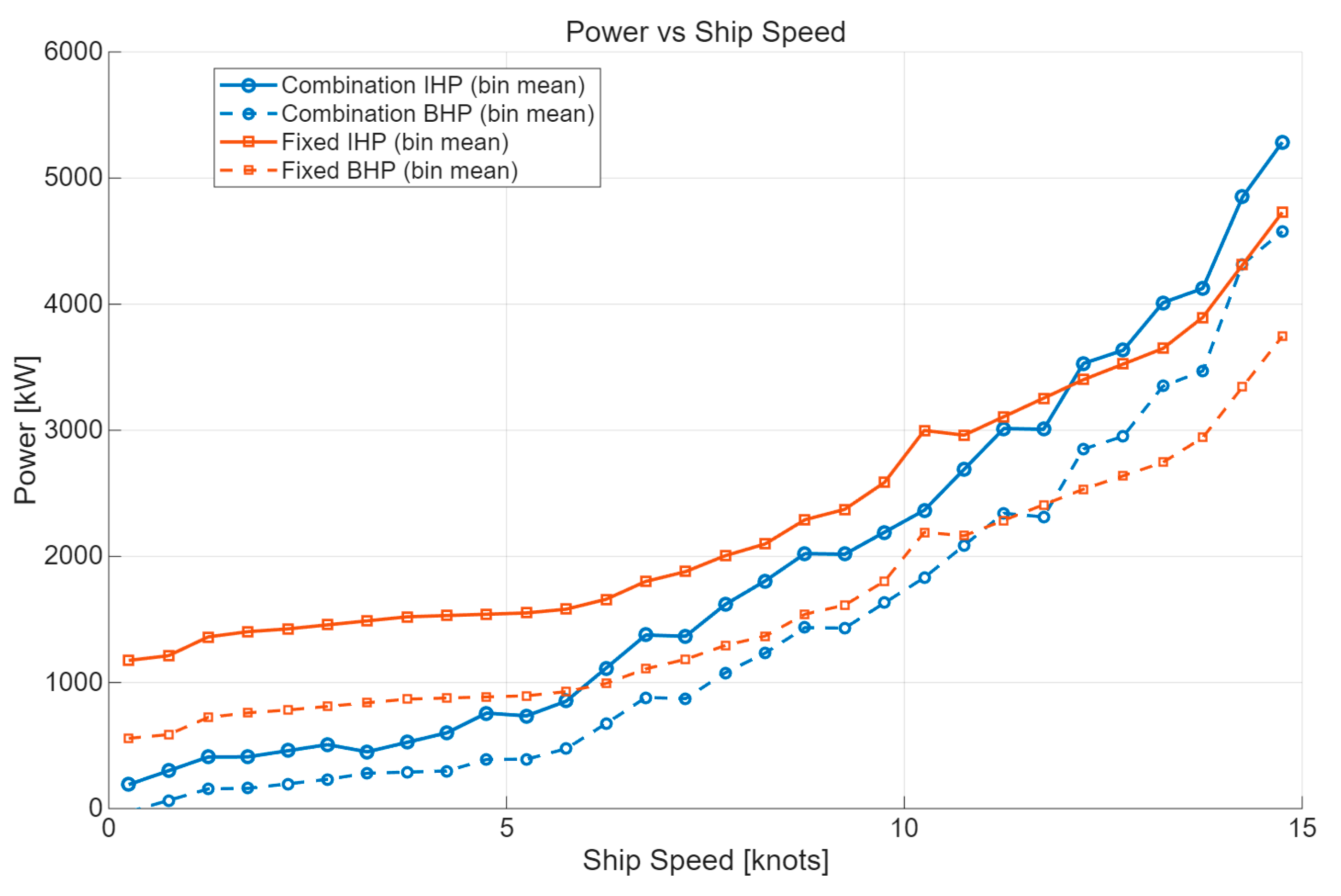

4.1. Power vs. Ship Speed

In this study, the indicated power (IHP) and brake power (BHP) under each operating mode were compared as functions of ship speed.

Figure 2 presents the averaged values, illustrating how power varies with ship speed.

Both IHP and BHP in the Combination and Fixed modes exhibited similar increasing trends across the entire speed range. However, in many cases at the same ship speed, the Fixed mode required higher power (IHP and BHP) than the Combination mode. Notably, in the low-speed region below 12 knots, the power demand of the Fixed mode consistently exceeded that of the Combination mode, whereas above 12 knots this relationship was reversed, with the Combination mode showing higher power demand.

These results suggest that in low-speed and low-load conditions, the Combination mode achieves relatively higher efficiency with reduced power loss, while the Fixed mode requires more power to maintain the same speed. In contrast, in the high-speed region (above 12 knots), the characteristics of the propulsion system and the behavior of the propeller efficiency curve lead to a crossover point where the relative advantage between the two operating modes is reversed.

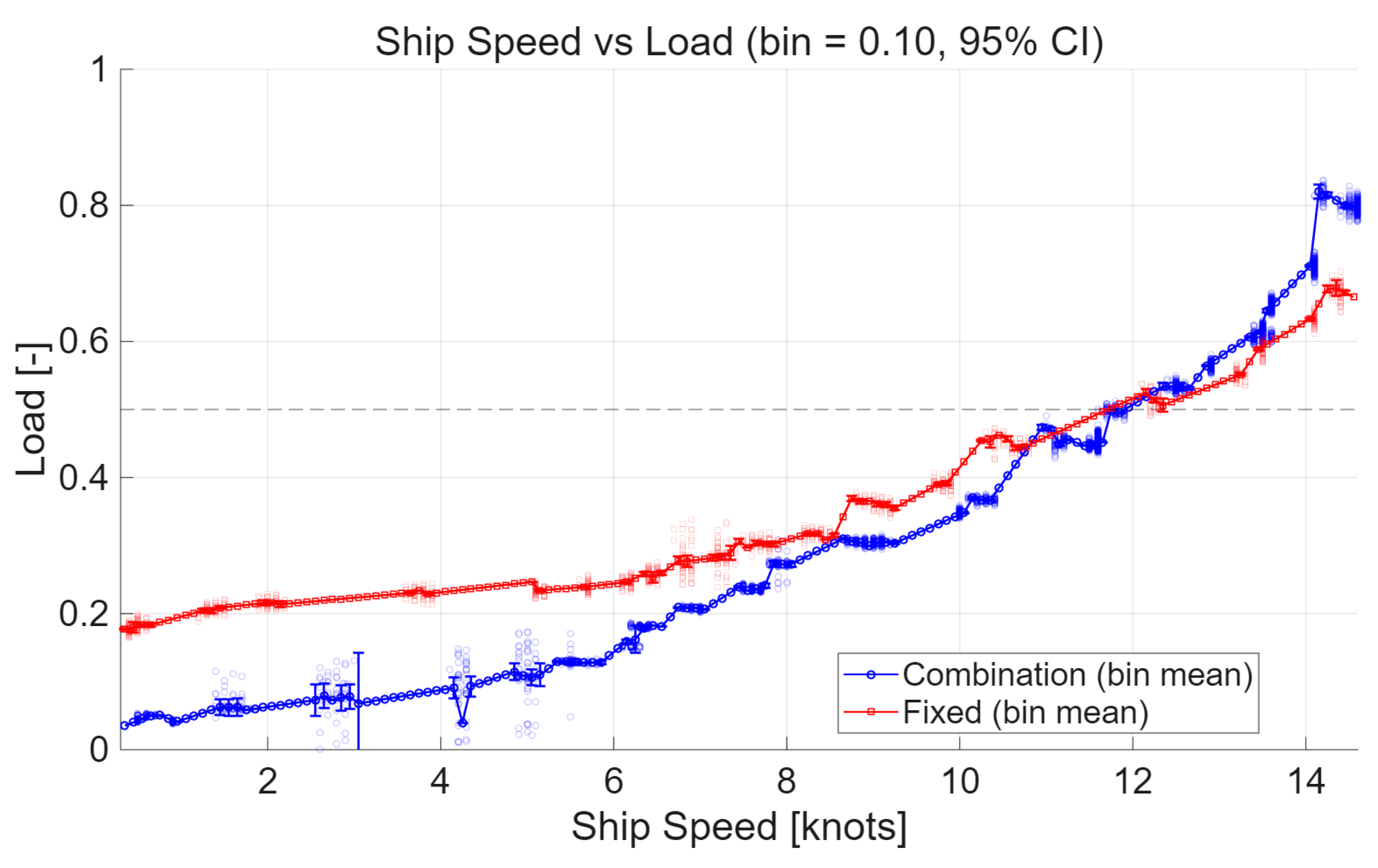

4.2. Ship Speed vs. Load

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between ship speed and engine load under the two operating modes. The analysis revealed a distinct cross-over point between the two modes at approximately 12 knots and 50% load. Below 12 knots, the Combination mode required consistently lower load ratios than the Fixed mode to maintain the same ship speed, indicating an advantage in reducing fuel consumption. For example, at 6 knots, the Combination mode required a load ratio of about 0.15, whereas the Fixed mode demanded approximately 0.25.

In the range of 11–12 knots, the load demands of the two modes converged, forming a cross-over point. Beyond this point (approximately 50% load), as operating conditions shifted toward higher speed and higher load, the Fixed mode exhibited lower load ratios and consequently gained an advantage in terms of fuel efficiency.

This cross-over phenomenon indicates that the Combination mode is more favorable for minimizing fuel consumption in low-speed and low-load conditions, whereas the Fixed mode becomes more economical under high-speed and high-load conditions. Therefore, switching operating modes around 11–12 knots and 50% load could optimize fuel consumption across the entire operating envelope.

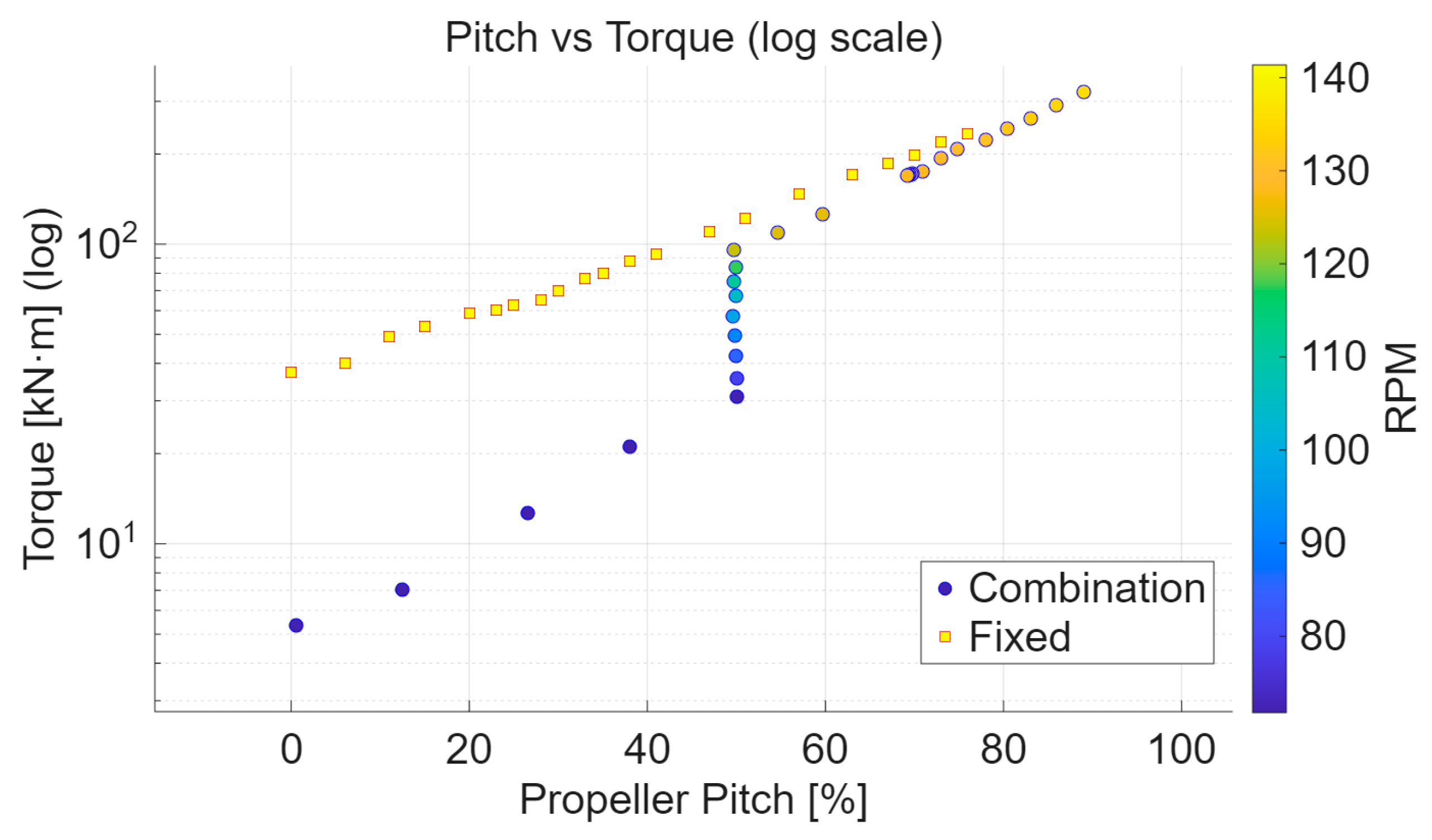

4.3. Pitch–Torque Relationship

Figure 4 presents the relationship between propeller pitch and torque on a logarithmic scale, clearly highlighting the fundamental differences in control characteristics between the two operating modes. The color scale indicates engine RPM, and the analysis confirmed that torque follows a proportional relationship with pitch.

In the Fixed mode, torque was consistently proportional to pitch across the entire range, forming a stable and predictable linear trend. The data distribution was demonstrated the basic principle that torque can be linearly controlled through pitch variation while maintaining a constant engine speed of approximately 140 RPM.

In contrast, the Combination mode exhibited substantial data dispersion in the low-pitch region (20–50%), with a particularly vertical distribution of torque values observed near 50% pitch. This indicates an operating characteristic in which torque is regulated by increasing engine RPM while keeping pitch constant. Specifically, at 50% pitch, torque ranged widely from about 20 kN∙m to 100 kN∙m —more than a fivefold variation—demonstrating the mechanism of adjusting torque and propulsive force by varying engine RPM at a fixed pitch setting. At higher pitch levels (above 50%), the Combination mode converged toward the stable relationship observed in the Fixed mode.

These contrasting control methods distinguish the two modes: the Fixed mode employs a simple and predictable torque control strategy based on constant RPM and pitch variation, whereas the Combination mode allows more flexible control by combining adjustments in both RPM and pitch. The nearly linear trend observed in logarithmic scaling is consistent with the theoretical proportionality law of torque to pitch derived from propeller theory [

18].

From a practical perspective, the Fixed mode offers predictability and stability, making precise torque management straightforward, while the Combination mode provides superior adaptability to varying operating conditions through its flexible control range. These characteristics help explain the efficiency differences analyzed earlier, illustrating that the multi-variable control of the Combination mode provides opportunities for optimization while simultaneously increasing control complexity.

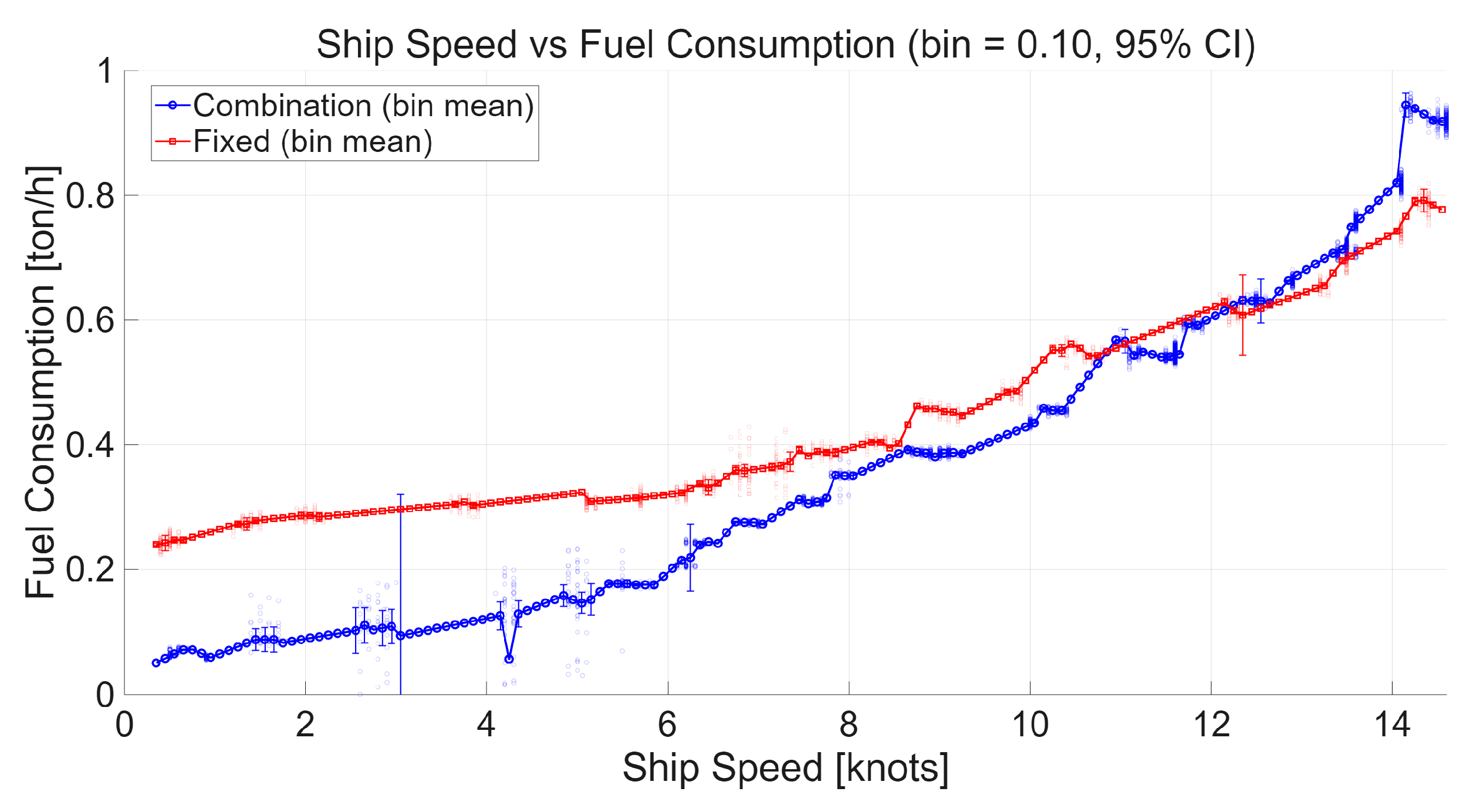

4.4. Relationship Between Ship Speed and Fuel Consumption

In order to quantitatively analyze the relationship between ship speed and fuel consumption (FC) under different operating modes, this study utilized the specific fuel oil consumption (SFOC) curves by engine load ratio in combination with the engine specification data. The training ship is equipped with a HYUNDAI–MAN B&W 6S40ME-B9.5-LP SCR two-stroke diesel engine (rated power: 6,618 kW at 146 rpm). Based on the reference SFOC value of 173.4 g/kWh at 100% load (Tier II, conventional turbocharger) as specified in the engine manual, the variation of SFOC with engine load was approximated using the following equation (1) [

18,

19].

Here, SFOCload denotes the specific fuel oil consumption (g/kWh) at a given load, while load represents the relative engine load (0–1).

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between ship speed and fuel consumption, where the previously identified cross-over phenomenon is again observed. In the low-speed range (0–6 knots), the Combination mode achieved superior fuel-saving performance, with consumption levels of approximately 0.05–0.2 ton/h, compared with 0.25–0.3 ton/h in the Fixed mode. This indicates that under low-load and low-speed conditions, the optimized engine–propeller matching of the Combination mode contributes significantly to improved fuel efficiency.

In the medium-speed range (6–11 knots), the difference in fuel consumption between the two modes gradually diminished, converging to nearly identical values around 11 knots, where a clear cross-over point was observed.

In the high-speed range (12–15 knots), the relationship was reversed. The Combination mode exhibited a sharp increase in fuel consumption due to its control strategy prioritizing higher speed through greater engine output and RPM, whereas the Fixed mode demonstrated a relatively moderate rate of increase as pitch variation was the primary control mechanism.

Overall, the Combination mode provided an average fuel-saving effect of about 54% in low-load and low-speed operations, demonstrating superior fuel efficiency. In the intermediate load and speed range, the difference between the two modes was marginal, allowing for flexible mode selection based on combined consideration of mechanical and propulsive efficiencies. At high load and high speed, however, the Combination mode’s focus on speed maintenance led to steep increases in fuel consumption, while the Fixed mode secured better economy through its relatively moderate growth in consumption. Based on these results, the Fixed mode is considered more economical for long-distance, high-speed voyages, whereas the Combination mode is more suitable for low-speed cruising and port entry/exit operations where fuel savings are critical.

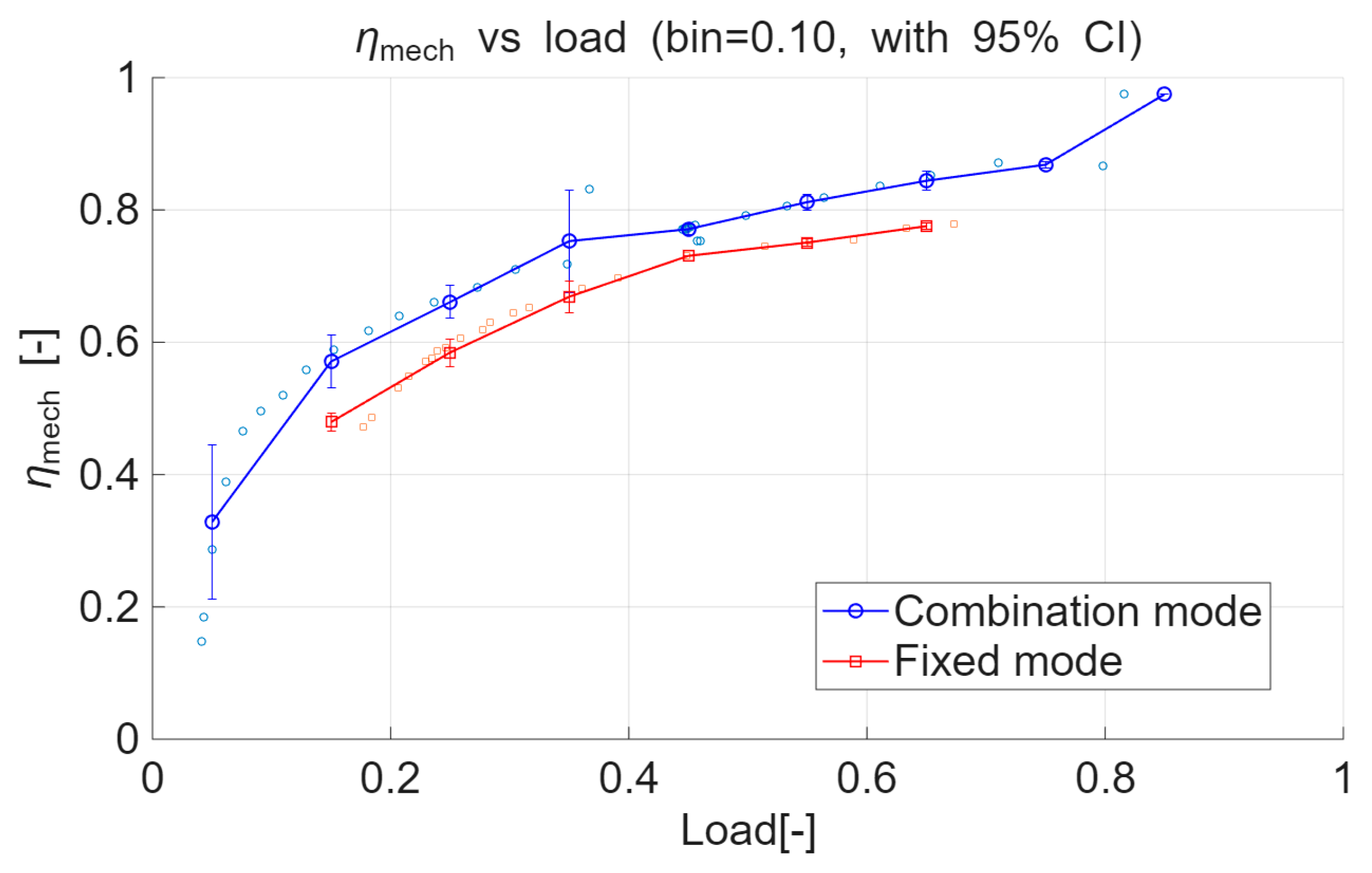

4.5. Mechanical Efficiency vs. Load

The comparison of engine mechanical efficiency (ηmech) across load ratios revealed that the Combination mode consistently achieved higher efficiency than the Fixed mode over the entire load range. On average, the Combination mode exceeded the Fixed mode by about 7–15 percentage points, with the performance gap gradually narrowing at higher loads. Nevertheless, across all operating conditions, the Combination mode demonstrated superior mechanical efficiency.

These findings suggest that the Combination mode is effective in minimizing mechanical losses and enabling the engine to operate closer to its optimal operating points by adjusting both RPM and propeller pitch simultaneously. In contrast, the Fixed mode, with its constant RPM constraint, shows limited adaptability to load variations, resulting in overall lower mechanical efficiency.

Figure 6.

Mechanical efficiency as a function of engine load in Combination and Fixed CPP modes.

Figure 6.

Mechanical efficiency as a function of engine load in Combination and Fixed CPP modes.

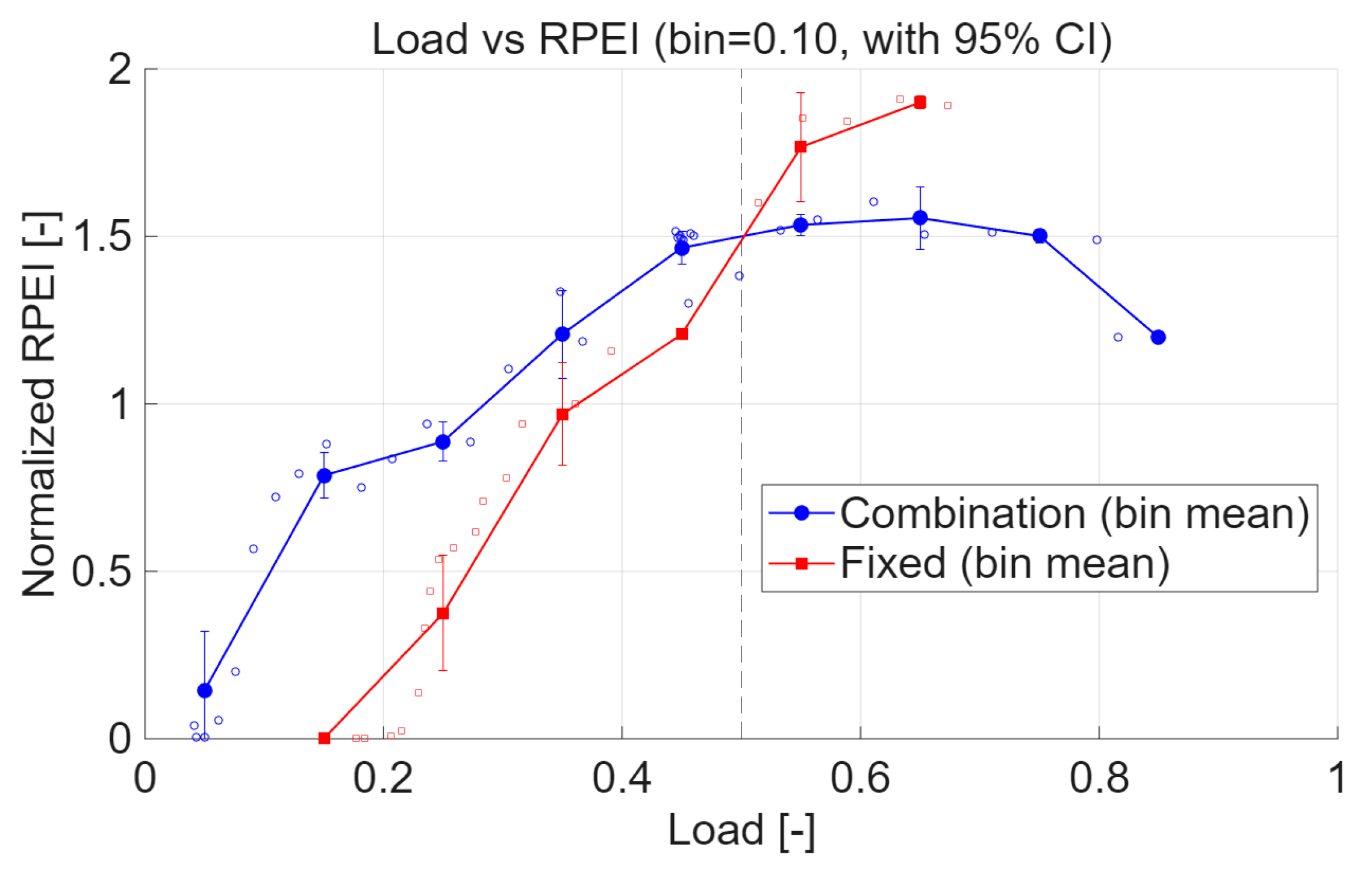

4.6. Analysis of the Relative Propulsive Efficiency Index (RPEI)

For a given ship, when hull form, draft, and sea conditions are assumed to remain constant, the effective horsepower (EHP) is approximately proportional to the cube of the ship speed, as expressed below:

where k is a proportional constant that can be cancelled out when the same resistance conditions are assumed across different operating modes. Accordingly, the propulsive efficiency can be expressed as equation (3) [

20]:

Since k is identical under the assumption of equal resistance conditions between operating modes, propulsive efficiency is thus proportional to the cube of ship speed and inversely proportional to shaft power:

Because direct calculation of propulsive efficiency from operational data is difficult, this study introduces the Relative Propulsive Efficiency Index (RPEI), newly defined as:

For comparability across datasets, the RPEI was normalized by the overall median value, ensuring that the median equals unity:

Figure 7 shows that the two operation modes exhibit distinct trends in RPEI

norm as a function of load. A clear crossover point occurs at approximately 0.5 load, where both modes reach an RPEI

norm of about 1.5. Prior to this point, the Combination mode demonstrates a relatively gradual increase in RPEI

norm, rising from 0.1 to 1.5, whereas the Fixed mode shows a much steeper increase, quickly catching up to the Combination mode. Beyond the crossover, the two modes diverge again: the Combination mode maintains its RPEI

norm near 1.5 and then gradually declines, while the Fixed mode continues to increase, exceeding 1.5 and reaching its peak performance at higher loads.

Therefore, the load ratio of 0.5 can be identified as a turning point: the Combination mode is more economical in low-load conditions, whereas the Fixed mode demonstrates superior propulsive efficiency under high-load conditions.

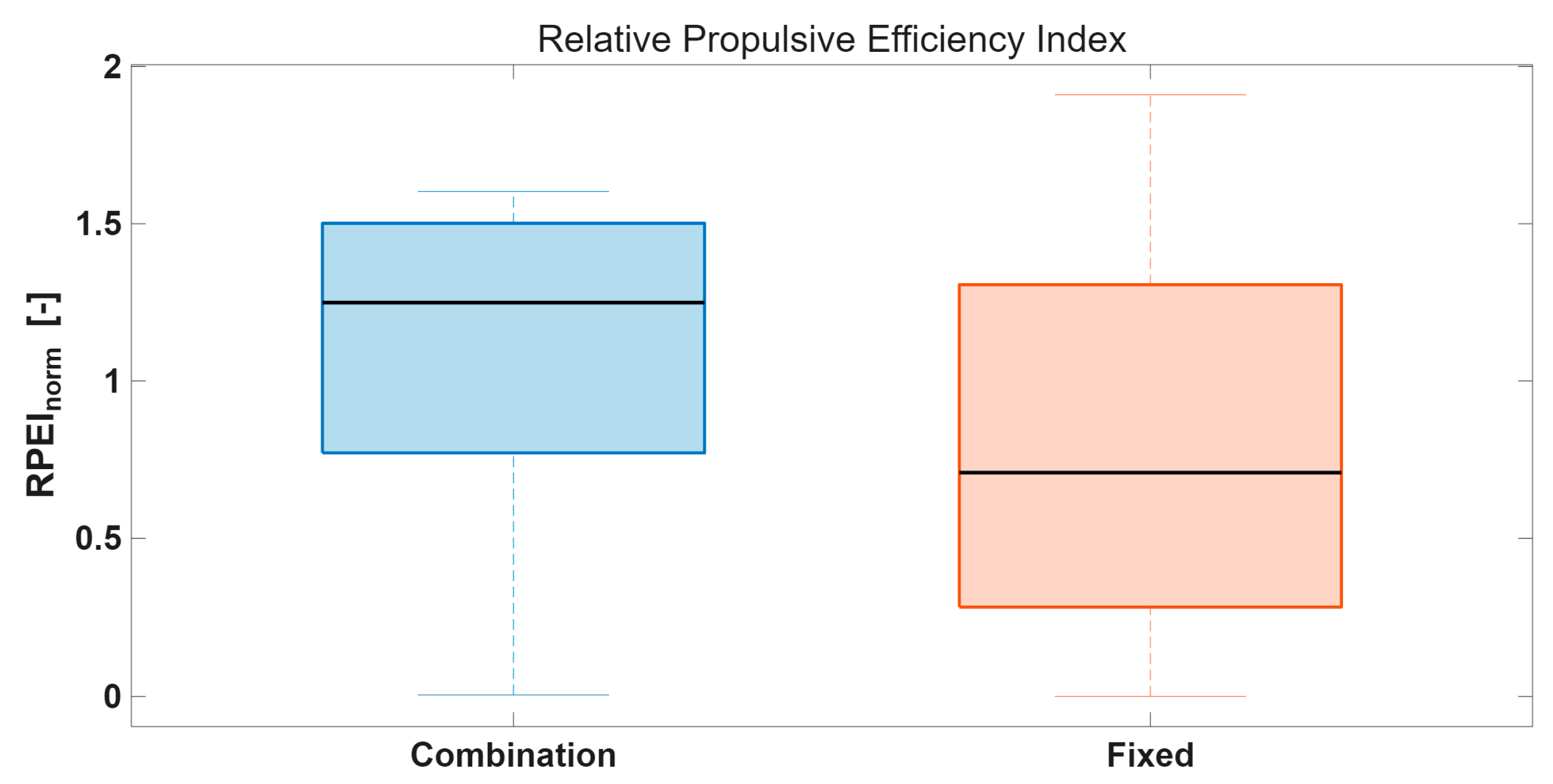

The box plot of

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of RPEI

norm under the Combination and Fixed modes. The median value of the Combination mode was approximately 1.25, significantly higher than that of the Fixed mode (about 0.75). This indicates that half of the observations in the Combination mode exceeded 1.25, suggesting superior overall propulsive efficiency compared with the Fixed mode.

In terms of the interquartile range (IQR), the Combination mode exhibited a narrower and more stable spread (0.8–1.5), whereas the Fixed mode showed a wider variability (0.4–1.3). This demonstrates that under similar load conditions, efficiency variations were larger in the Fixed mode than in the Combination mode.

The whiskers also highlight distinct characteristics between the two modes. While the Combination mode had a minimum value close to zero, its maximum extended to about 1.6, reflecting low efficiency under very low load but stable high efficiency at medium to high loads. By contrast, the Fixed mode also had a minimum near zero but extended to a maximum of around 1.9, indicating the potential for achieving higher efficiency at high loads, albeit with greater variability.

In terms of symmetry and variability, the Combination mode displayed relatively balanced quartile distributions and few outliers, reflecting stable operational efficiency. The Fixed mode, however, exhibited an asymmetric distribution with a longer lower-quartile span and multiple outliers, indicating greater efficiency fluctuations with changing operating conditions.

Overall, the Combination mode provides consistently higher and more stable efficiency across the full load range, making it more suitable for low- to mid-load operations where fuel economy is critical. The Fixed mode, on the other hand, can achieve peak efficiency values up to 1.9 but frequently exhibits lower efficiency and larger variability at low loads, suggesting that it is more appropriate for operations under sufficiently high load conditions.

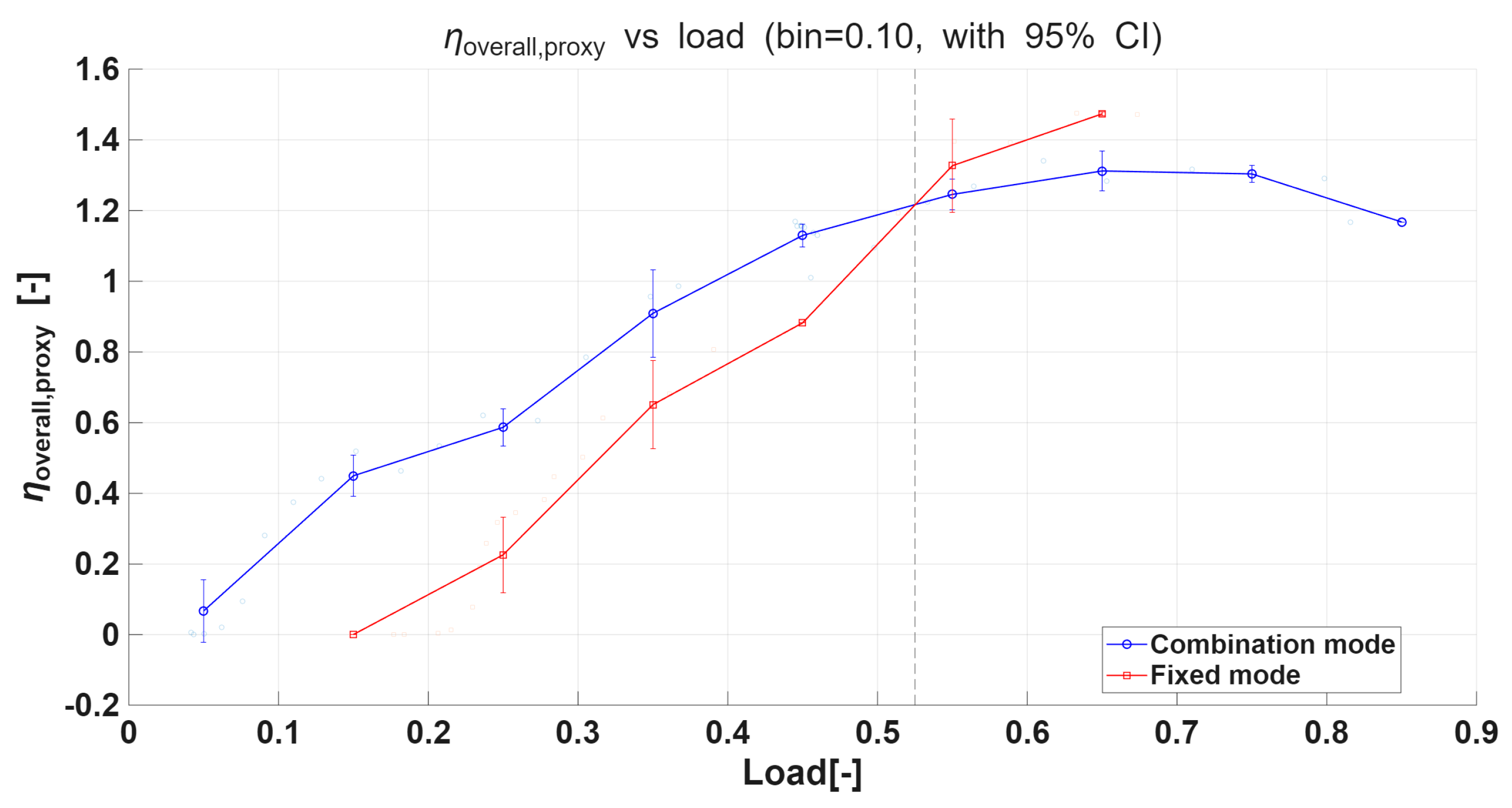

4.7. Overall Efficiency Proxy

By combining mechanical efficiency with the normalized propulsive efficiency, a proxy indicator was defined to approximate the relative overall efficiency of the propulsion system under actual operating conditions, as shown in equation (8):

The RPEI introduced in this study serves as a physical indicator for relative comparison of propulsive performance between operating modes when direct thrust measurement is not feasible, using only ship speed and shaft power data. By normalizing RPEI to a median value of unity, differences between modes can be intuitively interpreted as deviations above or below the central reference. When combined with ηmech, the proxy overall efficiency reflects both engine-side losses and propeller performance, providing a comprehensive measure of propulsion efficiency across a wide range of operating conditions.

The graph reveals a critical cross-over point at a load ratio of 0.525, which carries significant implications for ship propulsion system design and operational optimization. Below this threshold, the Combination mode demonstrates clear superiority. In this region, its overall proxy efficiency rises steeply from about 0.05 to 1.25, while the Fixed mode begins near zero and increases only gradually. This indicates that engine–propeller matching is more effectively optimized in the low-load range under the Combination mode.

The advantage of the Combination mode at low loads arises from its ability to adjust both engine RPM and propeller pitch simultaneously. This dual adjustment enables the engine to maintain an optimal RPM–torque balance while the propeller is set to an appropriate pitch angle, collectively achieving high mechanical and propulsive efficiency.

The cross-over point at a load ratio of 0.525 represents a critical threshold where the efficiency characteristics of the two operating modes fundamentally shift. At this point, both modes converge to an overall efficiency of approximately 1.25, reflecting a balance between their distinct optimization mechanisms. The convergence near this threshold highlights the interplay of trade-offs: in the Combination mode, mechanical efficiency remains high but its slope begins to decline, whereas in the Fixed mode, mechanical efficiency remains relatively lower but the RPEI slope rises sharply, offsetting the difference.

Beyond the 0.525 load ratio, the Fixed mode surpasses the Combination mode and sustains higher efficiency. The Fixed mode continues to rise, reaching a peak of about 1.5, while the Combination mode attains a maximum of around 1.3 before declining beyond a load ratio of 0.8.

Figure 9.

Proxy overall efficiency (ηoverall,proxy) versus load under Combination and Fixed CPP operating modes.

Figure 9.

Proxy overall efficiency (ηoverall,proxy) versus load under Combination and Fixed CPP operating modes.

This reversal phenomenon is attributed to the propeller optimization effect in the high-load region. In the fixed mode, the engine speed remains constant, and as the load increases, the propeller pitch also increases, allowing the propeller to operate closer to its optimum operating condition, thereby maximizing propulsive efficiency under high-load conditions. In contrast, the combination mode is primarily focused on engine optimization, which leads to a gradual decline in propeller–engine matching efficiency in the high-load range.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

This study compared and analyzed the combination mode and fixed mode of controllable pitch propellers (CPP) using actual ship operating data, focusing on mechanical efficiency (ηmech), propulsive efficiency (RPEInorm), and fuel consumption. The findings shed light on the dual optimization challenge in marine propulsion system design.

First, the combination mode consistently maintained higher ηmech across all load ranges by following an “engine-prioritized optimization” strategy. Particularly under low-load and low-speed conditions (ship speed < 12 knots, load < 50%), it achieved superior RPEInorm and reduced fuel consumption. This demonstrates that combination mode can enhance both economic and environmental performance in coastal navigation, port entry/exit, and low-speed cruising, where simultaneous adjustment of engine RPM and propeller pitch minimizes internal engine losses and secures favorable speed-to-power ratios.

Second, the fixed mode, following a “propeller-prioritized optimization” strategy, outperformed the combination mode in high-load and high-speed conditions. By keeping engine RPM constant and adjusting only the pitch, the fixed mode secured better RPEInorm and fuel efficiency once the load exceeded ~50% (corresponding to ~12 knots). Beyond this crossover point, the system gains more from optimizing propeller performance, even if engine efficiency is partially sacrificed. Thus, fixed mode proves more advantageous for long-distance voyages or sustained high-speed cruising.

Third, the efficiency patterns of the two modes highlight the trade-off between engine and propeller optimization in propulsion system design. Combination mode ensures consistently higher mechanical efficiency but sacrifices propeller efficiency at high loads, whereas fixed mode maximizes propeller performance in heavy-load conditions at the expense of engine efficiency. This finding underscores that no single efficiency indicator is sufficient to determine the optimal design point; rather, operating profiles must guide a context-dependent optimization strategy.

Fourth, the proposed proxy overall efficiency (ηoverall,proxy), defined as the product of ηmech and RPEInorm, offers a useful integrated metric for evaluating propulsion performance. This indicator can support real-time optimization and control algorithms, enabling adaptive switching between modes based on operating conditions. Using 50% load and 12 knots as a reference point, operators could dynamically choose between combination and fixed mode to maximize overall voyage efficiency.

Finally, several limitations and directions for future research are noted. Incorporating draft, sea state, and thrust measurements will allow more precise evaluation of true propulsive efficiency. since this analysis was limited to a single vessel and CPP system, broader studies across diverse ship types and propeller designs are necessary. To validate the applicability of the proposed real-time mode-switching strategy, follow-up studies should include simulation-based verification and full-scale sea trials.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of mission- and profile-specific optimization in marine propulsion system design. By quantifying the trade-off between combination and fixed mode, it provides practical insights for enhancing both fuel economy and compliance with environmental regulations. Furthermore, the findings lay a foundation for the development of intelligent control and automation technologies for future propulsion systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jiwoong Lee and Jae-Ung Lee; methodology, Jiwoong Lee and Voung Quang Dao; software, Voung Quang Dao; validation, Jiwoong Lee, Eun-Seok Jeong, Jung-Ho Noh and Jae-Ung Lee; formal analysis, Jiwoong Lee and Voung Quang Dao; investigation, Jiwoong Lee, Eun-Seok Jeong and Jung-Ho Noh; resources, Jae-Ung Lee; data curation, Eun-Seok Jeong and Jung-Ho Noh; writing—original draft preparation, Jiwoong Lee; writing—review and editing, Jae-Ung Lee, Eun-Seok Jeong and Jung-Ho Noh; visualization, Voung Quang Dao; supervision, Jae-Ung Lee; project administration, Jae-Ung Lee; funding acquisition, Jae-Ung Lee. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion(KIMST) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, grant number (20220630).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT to improve clarity and readability of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IMO Report of the Marine Environment Protection Committee on Its Eighty-Third Session (MEPC 83/24); International Maritime Organization (IMO).

- Tian, W.; Lang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yan, S.; Li, B.; Zang, S. Optimization of Controllable-Pitch Propeller Operations for Yangtze River Sailing Ships. JMSE 2024, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogar, O.B.; Nitonye, S.; John-Hope, I. Design Analysis and Optimal Matching of a Controllable Pitch Propeller to the Hull and Diesel Engine of a CODOG System. JPEE 2018, 06, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A SMART WAY OF USING A CONTROLLABLE PITCH PROPELLER.

- Geertsma, R.; Negenborn, R.R.; Visser, K.; Hopman, J. Design and Control of Hybrid Power and Propulsion Systems for Smart Ships: A Review of Developments. Applied energy 2017, 194, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planakis, N.; Papalambrou, G.; Kyrtatos, N. Ship Energy Management System Development and Experimental Evaluation Utilizing Marine Loading Cycles Based on Machine Learning Techniques. Applied Energy 2022, 307, 118085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertsma, R.; Visser, K.; Negenborn, R. Adaptive Pitch Control for Ships with Diesel Mechanical and Hybrid Propulsion. Applied energy 2018, 228, 2490–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypa, I.; Jansson, M.; Gustafsson, R.; Werner, S.; Bensow, R. Controllable-Pitch Propeller Design Process for a Wind-Powered Car-Carrier Optimising for Total Energy Consumption. Ocean Engineering 2023, 269, 113426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Bloch, F.; Brodtkorb, A.H. Novel Combinator Surface Concept for Efficiency Optimization of Ship Propulsion System. Ocean Engineering 2023, 280, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Brodtkorb, A.H.; Zadeh, M.; Mo, S.M. Power Management and Optimization of Marine Hybrid Propulsion Systems: A Combinator Surface Methodology. Ocean Engineering 2024, 309, 118354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, D.; Delen, C.; Belhenniche, S.E.; Kinaci, O.K. Effect of Propeller Pitch on Ship Propulsion. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2022, 11, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-S.; Je, M.-A.; Hwang, S.-C. A Study on Performance and Exhaust Emission Characteristics According to the Controllable Pitch Propeller Operation of Two-Stroke Diesel Engine in Sailing Condition. jamet 2024, 48, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, L.; Chen, S. Marine Propeller Optimization Based on a Novel Parametric Model. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022, 2022, 5612793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.G.; Kim, H.C. A Study on the Matching Problem of Engine, Propeller, and Ship Hull under Actual Service Conditions. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2023, 15, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halilbeşe, A.N. Investigating the Torsional Vibration Behaviour of Composite Drive Shafts in Marine Propulsion Shaft Systems. jnamt 2025, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.S. Energy Coefficients for a Propeller Series. Ocean engineering 2004, 31, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Stapersma, D.; Grimmelius, H. Analysis of Energy Conversion in Ship Propulsion System in Off-Design Operation Conditions. WIT transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2009, 121. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization Fourth IMO Greenhouse Gas Study (2020); London: International Maritime Organization.

- Lee, J.-U.; Lee, W.-J.; Jeong, E.-S.; Noh, J.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, J.-W. Algorithm for Monitoring Emissions Based on Actual Speed of Ships Participating in the Korean Vessel Speed Reduction Program. Energies 2022, 15, 9555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAN Energy Solutions Basic Pricciples of Ship Propulsion; MAN Energy Solutions.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).