Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Extraction

2.2. Chemical Analysis of Marrubium Vulgare Extracts

2.3. Structures Preparation

2.4. Molecular Docking

2.5. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

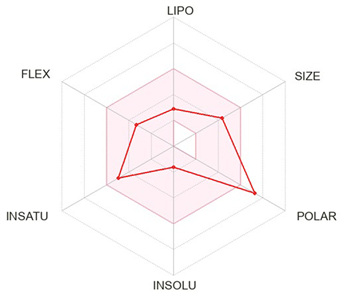

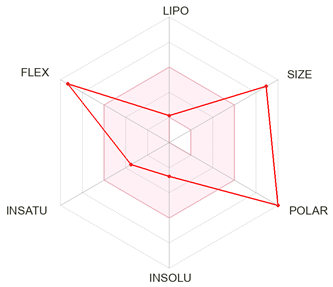

2.5. ADMET Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Extraction

4.2. Chemical Analysis of Marrubium Vulgare Extracts

4.3. Database Preparation

4.4. Extra Precision Docking

4.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

4.6. ADMET Assessment

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTD | C Terminal Domain |

| HPLC-MS | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectormetry |

| Hsp90 | Heat-Shock Protein 90 |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| MMGBSA | Molecular mechanics with generalized Born and surface area solvation |

| NTD | N Terminal Domain |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| RMSF | Root Mean Square Fluctuation |

| XP | Extra Precision |

References

- B. B. Petrovska, “Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage,” Pharmacogn. Rev., vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 1–5, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Akram and K. Mahmood, “Awareness and current knowledge of medicinal plants,” RPS Pharm. Pharmacol. Rep., vol. 3, no. 4, p. rqae023, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ouadghiri et al., “In Vivo and In Vitro Assessment of Marrubium vulgare: Chemical, Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Profiles,” Arab. J. Sci. Eng., Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Bouyahya et al., “Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of Moroccan medicinal plants: Phytochemistry, in vitro and in vivo investigations, mechanism insights, clinical evidences and perspectives,” J. Pharm. Anal., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 35–57, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Eddouks, M. Ajebli, and M. Hebi, “Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used in Daraa-Tafilalet region (Province of Errachidia), Morocco,” J. Ethnopharmacol., vol. 198, pp. 516–530, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Fakir, V. Bito, A. Zaid, and T. M. Alaoui, “Complimentary Herbal Treatments Used in Meknes-Tafilalet Region (Morocco) to Manage Cancer,” Am. J. Plant Sci., vol. 10, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Aboufaras, K. Selmaoui, and N. Ouzennou, “Adverse effects of medicinal plants used by cancer patients in Beni Mellal and the communication of this use,” E3S Web Conf., vol. 319, p. 01107, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Aćimović et al., “Marrubium vulgare L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 12, p. 2898, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. K. Popoola, A. M. Elbagory, F. Ameer, and A. A. Hussein, “Marrubiin,” Molecules, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 9049–9060, July 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Al-Khayri, G. R. Sahana, P. Nagella, B. V. Joseph, F. M. Alessa, and M. Q. Al-Mssallem, “Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review,” Molecules, vol. 27, no. 9, p. 2901, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Gourich et al., “Insight into biological activities of chemically characterized extract from Marrubium vulgare L. in vitro, in vivo and in silico approaches,” Front. Chem., vol. 11, p. 1238346, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Chiosis, C. S. Digwal, J. B. Trepel, and L. Neckers, “Structural and functional complexity of HSP90 in cellular homeostasis and disease,” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 797–815, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Miyata, H. Nakamoto, and L. Neckers, “The therapeutic target Hsp90 and cancer hallmarks,” Curr. Pharm. Des., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 347–365, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Trepel, M. Mollapour, G. Giaccone, and L. Neckers, “Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer,” Nat. Rev. Cancer, vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 537–549, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Trepel, M. Mollapour, G. Giaccone, and L. Neckers, “Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer,” Nat. Rev. Cancer, vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 537–549, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, R. Chen, C. Wang, Y. Wang, and J. Zhang, “Targeting HSP90 for Cancer Therapy: Current Progress and Emerging Prospects,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 67, no. 18, pp. 15968–15995, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Riedl et al., “Evolution of the conformational dynamics of the molecular chaperone Hsp90,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 8627, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Amri et al., “Marrubium vulgare L. Leave Extract: Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant and Wound Healing Properties,” Mol. J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem., vol. 22, no. 11, p. 1851, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. Zarguan, S. Ghoul, L. Belayachi, and A. Benjouad, “Plant-Based HSP90 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Models: A Systematic Review,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 25, no. 10, p. 5468, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Liew, X. Y. Tan, H. H. Chan, K. Y. Khaw, and Y. S. Ong, “Natural HSP90 inhibitors as a potential therapeutic intervention in treating cancers: A comprehensive review,” Pharmacol. Res., vol. 181, p. 106260, July 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Aćimović et al., “Marrubium vulgare L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview,” Mol. Basel Switz., vol. 25, no. 12, p. 2898, June 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Puangpraphant, E.-O. Cuevas-Rodríguez, and M. Oseguera-Toledo, “Chapter 9 - Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant phenolic compounds,” in Current Advances for Development of Functional Foods Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress, B. Hernández-Ledesma and C. Martínez-Villaluenga, Eds., Academic Press, 2022, pp. 165–180. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Dias, D. C. G. A. Pinto, and A. M. S. Silva, “Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 17, p. 5377, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Li and J. Buchner, “Structure, function and regulation of the hsp90 machinery,” Biomed. J., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 106–117, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Meng et al., “Chlorogenic acid regulates the expression of NPC1L1 and HMGCR through PXR and SREBP2 signaling pathways and their interactions with HSP90 to maintain cholesterol homeostasis,” Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm., vol. 123, p. 155271, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen et al., “Luteolin exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by blocking the activity of heat shock protein 90 in macrophages,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., vol. 443, no. 1, pp. 326–332, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Lv et al., “Effects of luteolin on treatment of psoriasis by repressing HSP90,” Int. Immunopharmacol., vol. 79, p. 106070, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Genheden and U. Ryde, “The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities,” Expert Opin. Drug Discov., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 449–461, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Gu et al., “Advances in the structures, mechanisms and targeting of molecular chaperones,” Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 84, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, W. Huang, K. Zhou, X. Ren, and K. Ding, “Targeting the Non-Catalytic Functions: a New Paradigm for Kinase Drug Discovery?,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 1735–1748, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, “SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 42717, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Noddings, R. Y.-R. Wang, J. L. Johnson, and D. A. Agard, “Structure of Hsp90–p23–GR reveals the Hsp90 client-remodelling mechanism,” Nature, vol. 601, no. 7893, pp. 465–469, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Waterhouse et al., “SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 46, no. W1, pp. W296–W303, July 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Laskowski, M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton, “PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures,” J. Appl. Crystallogr., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 283–291, Apr. 1993. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Friesner et al., “Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 49, no. 21, pp. 6177–6196, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Laskowski and M. B. Swindells, “LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 2778–2786, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- “Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters | Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing,” ACM Conferences. Accessed: Aug. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1188455.1188544. [CrossRef]

- A. Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, “SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 42717, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Banerjee, E. Kemmler, M. Dunkel, and R. Preissner, “ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 52, no. W1, pp. W513–W520, July 2024. [CrossRef]

| Middle domain Chain A | Middle domain Interchain | CTD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Docking score | Compound | Docking score | Compound | Docking score |

| Forsythoside B | -6.84 | Forsythoside B | -7.96 | Luteolin | -7.82 |

| Terniflorin | -6.59 | Samioside | -7.64 | Naringenin | -7.50 |

| Rosmarinic_acid | -6.48 | Terniflorin | -7.44 | Chlorogenic acid | -7.33 |

| Luteolin7_o_glucuronide | -6.48 | Alyssonoside | -7.33 | Galangin | -7.20 |

| Apigenin | -6.40 | Verbascoside | -6.93 | Forsythoside B | -6.99 |

| Samioside | -6.26 | Acteoside | -6.93 | Diosmetin | -6.91 |

| Acteoside | -5.97 | Rosmarinic_acid | -6.85 | Terniflorin | -6.89 |

| Verbascoside | -5.97 | LeucosceptosideA | -6.71 | Samioside | -6.80 |

| Luteolin7_O_rutinoside | -5.91 | Echinacin | -6.50 | Acacetin | -6.65 |

| Vicenin2 | -5.90 | Vicenin2 | -6.20 | Vulgarin | -6.52 |

| Echinacin | -5.86 | Diosmetin | -6.06 | Ladanein | -6.43 |

| Rutin | -5.73 | Syringic_acid | -6.03 | Rosmarinic_acid | -6.33 |

| Alyssonoside | -5.69 | Luteolin | -5.94 | Alyssonoside | -6.26 |

| Luteolin | -5.62 | Naringenin | -5.77 | Acteoside | -6.26 |

| Aesculin | -5.56 | Diosmetin_7_O_glucoside | -5.70 | Verbascoside | -6.26 |

| Eugenol | -5.38 | Acacetin | -5.57 | cis_Piperitone | -6.13 |

| Diosmetin | -5.18 | Luteolin7_O_rutinoside | -5.53 | Echinacin | -5.71 |

| Chlorogenic acid | -4.95 | Rutin | -5.49 | Syringic_acid | -5.64 |

| Acacetin | -4.90 | Ladanein | -5.41 | Aesculin | -5.63 |

| Galangin | -4.88 | Galangin | -5.34 | Luteolin7_O_rutinoside | -5.60 |

| Vulgarin | -4.86 | Chlorogenic acid | -5.05 | Apigenin | -5.59 |

| Syringic_acid | -4.71 | Aesculin | -4.99 | Rutin | -5.42 |

| Ladanein | -4.62 | Novobiocin | -4.98 | LeucosceptosideA | -5.36 |

| Peregrinin | -4.61 | Apigenin | -4.92 | Diosmetin_7_O_glucoside | -5.27 |

| Diosmetin_7_O_glucoside | -4.54 | Eugenol | -4.87 | Eugenol | -5.24 |

| Marrubiin | -4.48 | Vulgarin | -4.85 | Marrubenol | -4.91 |

| o_Coumaric_acid | -4.48 | Peregrinin | -4.82 | Vicenin2 | -4.78 |

| Oxacyclohexadecan_2_one | -4.44 | o_Coumaric_acid | -4.77 | Luteolin7_o_glucuronide | -4.63 |

| Para_coumaric_acid | -4.44 | Oxacyclohexadecan_2_one | -4.57 | Para_coumaric_acid | -4.46 |

| Cyllenin_A | -4.35 | Luteolin7_o_glucuronide | -4.35 | Radicicol | -4.43 |

| Naringenin | -4.26 | Cyllenin_A | -4.26 | o_Coumaric_acid | -4.16 |

| cis_Piperitone | -4.25 | Para_coumaric_acid | -4.19 | 17AAG | -4.14 |

| Caffeoylmalic acid | -4.08 | Marrubiin | -4.13 | Oxacyclohexadecan_2_one | -3.88 |

| Novobiocin | -3.99 | Marrubenol | -4.10 | Novobiocin | -3.69 |

| Radicicol | -3.86 | cis_Piperitone | -4.10 | Premarrubiin | -3.56 |

| Premarrubiin | -3.79 | Enniatin A | -4.05 | Caffeoylmalic acid | -3.52 |

| 17AAG | -3.47 | Radicicol | -3.99 | Marrubiin | -3.50 |

| Marrubenol | -3.30 | Premarrubiin | -3.92 | Cyllenin_A | -3.42 |

| Geldanamycin | -3.02 | 24_Ethylcholest_5_en_3beta_ol | -3.81 | Peregrinin | -3.39 |

| Leucosceptoside A | -2.74 | Sitosterol | -3.81 | 24_Ethylcholest_5_en_3beta_ol | -3.13 |

| Enniatin A | -2.50 | Stigmast_5_en_3_ol | -3.81 | Sitosterol | -3.13 |

| 24_Ethylcholest_5_en_3beta_ol | -2.23 | Caffeoylmalic acid | -3.61 | Stigmast_5_en_3_ol | -3.13 |

| Sitosterol | -2.23 | Geldanamycin | -3.43 | Geldanamycin | -2.96 |

| Stigmast_5_en_3_ol | -2.23 | Phytol | -1.39 | Phytol | -2.37 |

| Phytol | -0.58 | Methyl_linoleate | 0.14 | Enniatin A | -2.29 |

| Octadecatrienic_acid | 0.86 | Methyl_linoleate | -1.00 | ||

| Octadecatrienic_acid | -0.56 | ||||

| Unbound structure | Middle domain Chain A |

Middle domain Interchain |

CTD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp90α | Forsythoside B | Rosmarinic Acid | Forsythoside B | Chlorogenic acid | Luteolin | ||

| RMSD (Å) | Avg | 6.56 | 5.25 | 6.14 | 6.47 | 6.16 | 6.11 |

| SD | 1.01 | 0.68 | 0.96 | 1.14 | 0.97 | 0.85 | |

| RMSF (Å) | Avg | 2.16 | 1.87 | 1.96 | 1.90 | 2.07 | 2.11 |

| SD | 1.41 | 1.37 | 1.29 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.30 | |

| Complex | ΔG Average (kcal mol-1) | ΔG Standard Deviation | ΔG Range |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Forsythoside B (Interchain) |

-71.68 | 14.62 | -107.08 to 0.69 |

| Chlorogenic Acid (CTD) | -51.50 | 10.02 | -64.47 to 0.53 |

| Chlorogenic acid |  |

Formula | C16H18O9 |

| Molecular weight | 354.31 g/mol | ||

|

Druglikeness (Lipinski) |

Yes; 1 violation: NHorOH>5 | ||

| Log S (ESOL) | -1.62 | ||

| Consensus LogPo/w | -0.38 | ||

| TPSA | 164.75 Å2 | ||

| Bioavailability Score | 0.11 | ||

| Forsythoside B |  |

Formula | C34H44O19 |

| Molecular weight | 756.70 g/mol | ||

|

Druglikeness (Lipinski) |

No; 3 violations: MW>500, NorO>10, NHorOH>5 | ||

| Log S (ESOL) | -2.69 | ||

| Consensus LogPo/w | -1.49 | ||

| TPSA | 304.21 Å2 | ||

| Bioavailability Score | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).