Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extract Obtention and Phytochemical Composition Analyses

2.2. Experimental Animals

2.3. Cell Lines Culture

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5. Early Apoptosis Analysis

2.6. Oligonucleosomal DNA Fragmentation Analysis

2.7. Antagonistic Effect Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

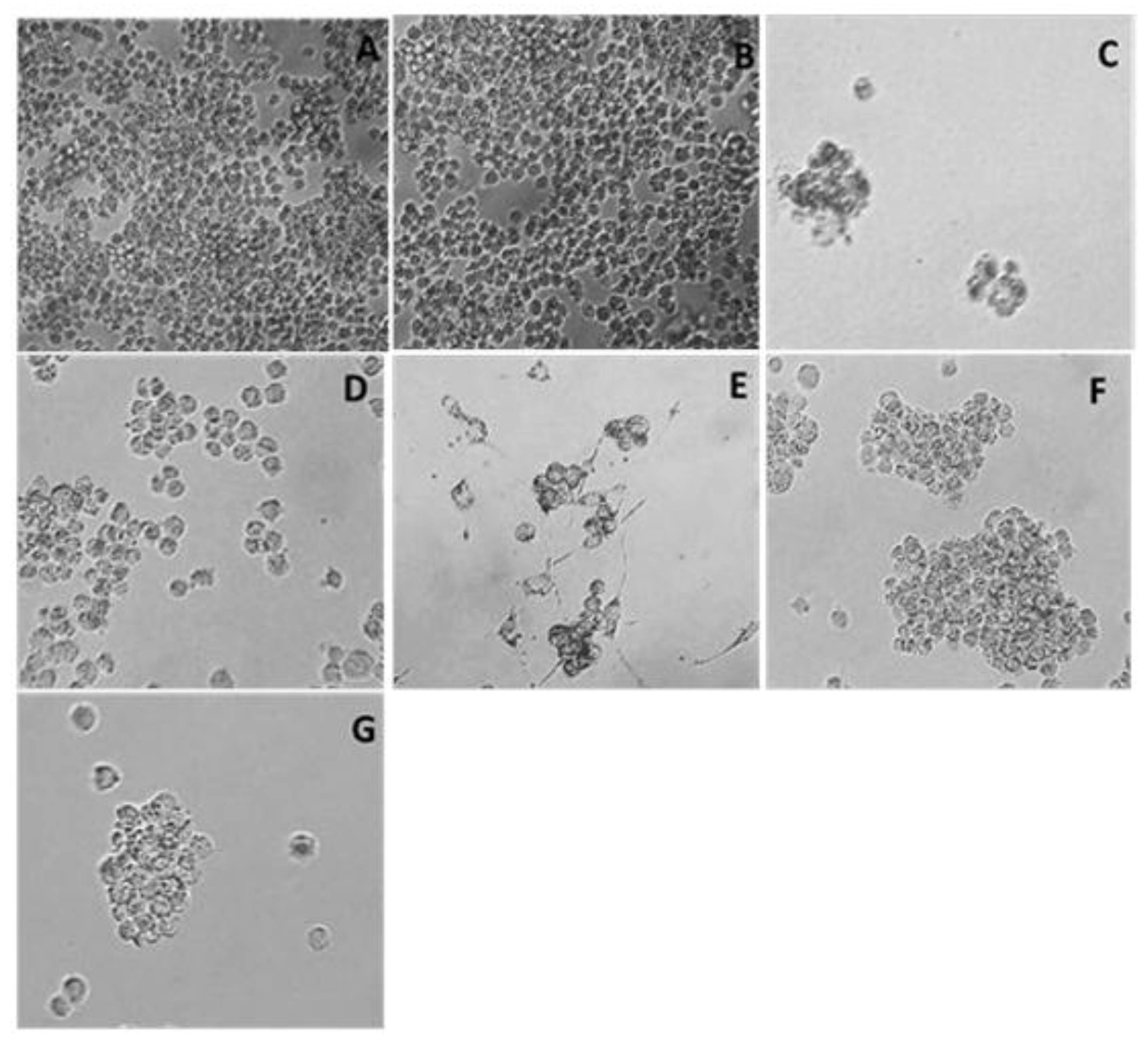

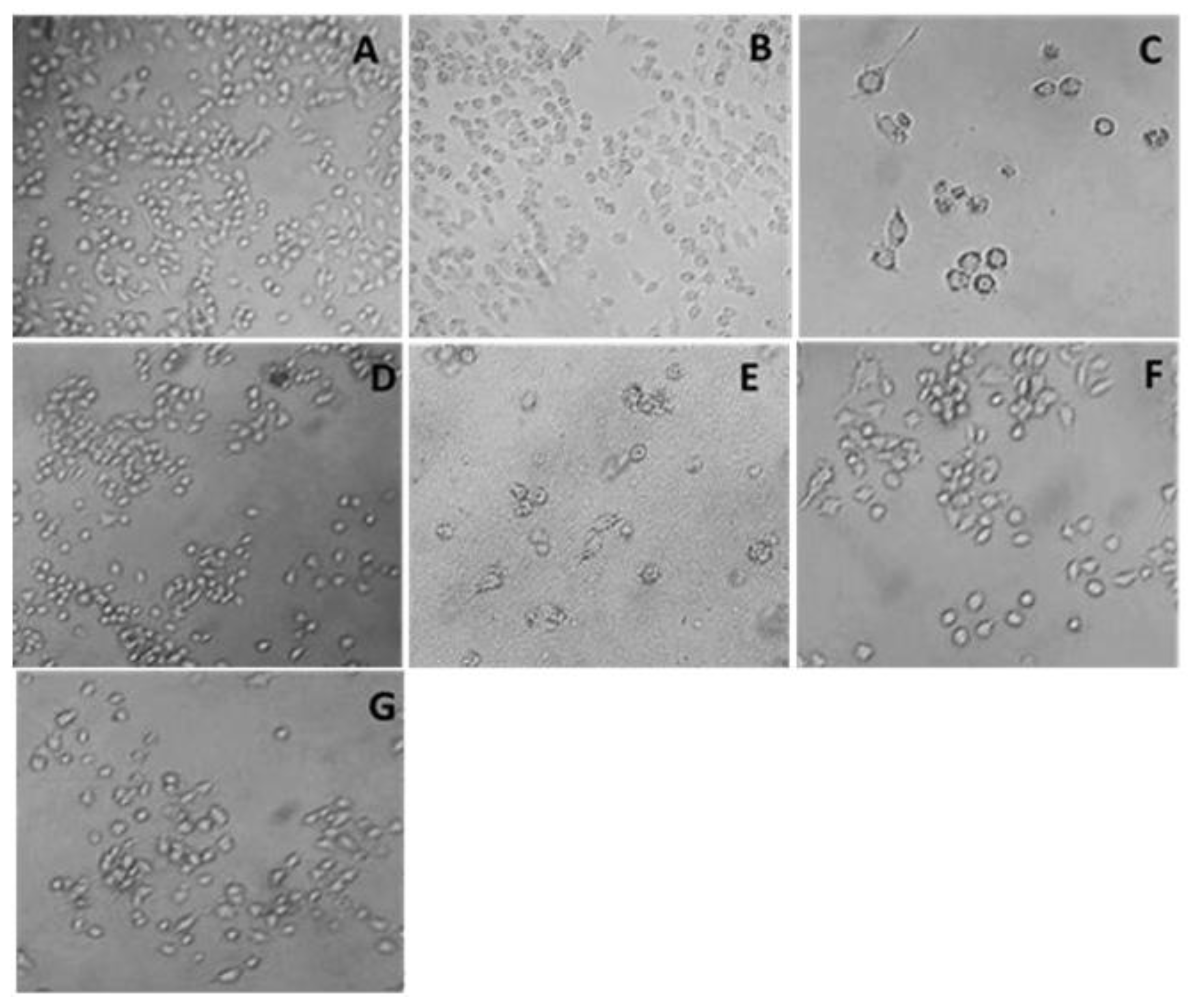

3.1. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.2. Flow Cytometry Assay

| Cells per quadrant (%) | ||||

| Treatment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Control | 0.5 | 0.2 | 99.2 | 0.1 |

| Vehicle (PBS) | 1.7 | 9.9 | 86.1 | 2.3 |

| Ara-C (Cytarabine®) | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.8 | 92.6 |

| H-387-07 | 0.6 | 17.5 | 53.2 | 28.7 |

| S. edule var. nigrum spinosum | 4.4 | 95.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| S. compositum | 0.6 | 21.0 | 33.2 | 45.1 |

| S. chinantlense | 2.1 | 23.9 | 48.9 | 25.0 |

| Cells per quadrant (%) | ||||

| Treatment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Control | 0.1 | 0.0 | 82.0 | 17.9 |

| Vehicle (PBS) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 84.1 | 15.7 |

| Ara-C (Cytarabine®) | 10.0 | 18.2 | 34.1 | 37.7 |

| H-387-07 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 63.3 | 23.0 |

| S. edule var. nigrum spinosum | 17.1 | 82.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| S. compositum | 0.7 | 16.2 | 50.6 | 32.6 |

| S. chinantlense | 0.2 | 9.0 | 51.6 | 39.3 |

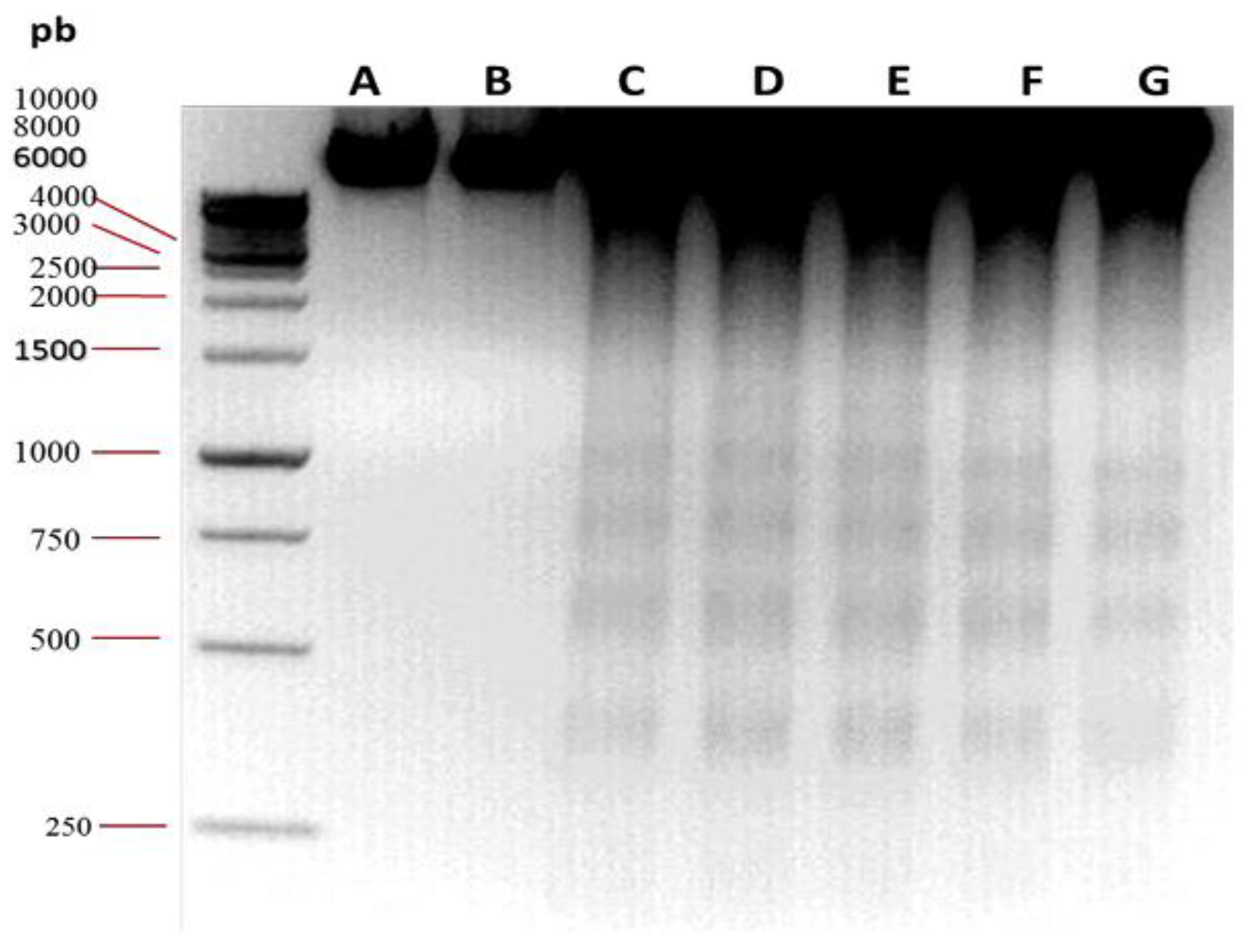

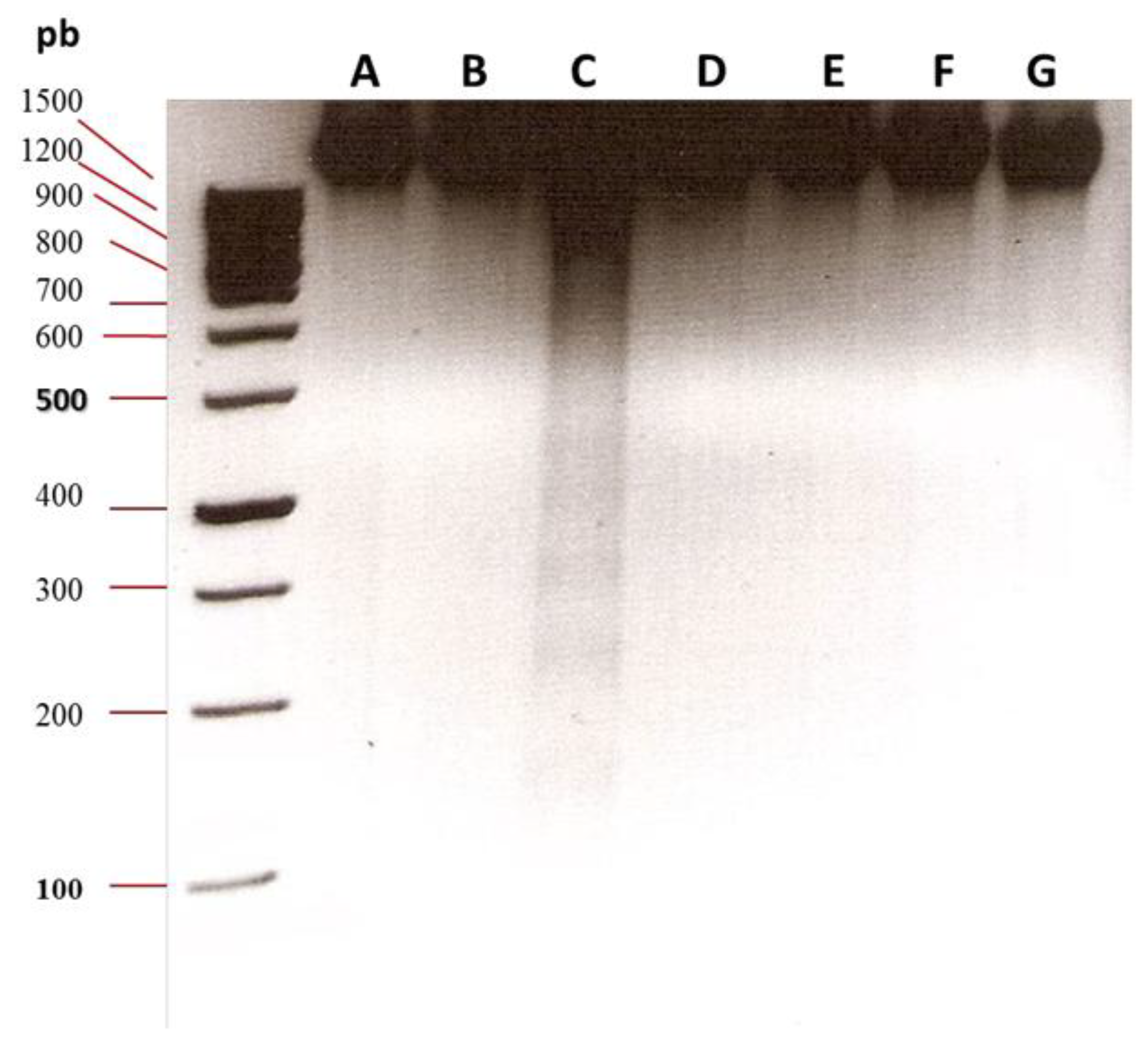

3.2. Oligonucleosomal DNA Fragmentation Analysis

3.3. Antagonistic Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gower, M.; Li, X.; Aguilar-Navarro, A.G.; Lin, B.; Fernandez, M.; Edun, G.; Nader, M.; Rondeau, V.; Arruda, A.; Tierens, A.; et al. An Inflammatory State Defines a High-Risk T-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Subgroup. Science Translational Medicine 2025, 17, eadr2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, C.; Liang, Y.; Qing, S.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. The Burden Dynamics of Leukemia in China from 1990 to 2021: An Epidemiological Analysis of Trends, Risk Factors, and Projections to 2036. Preventive Medicine Reports 2025, 57, 103191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghouraba, R.F.; EL-Desouky, S.S.; El-Shanshory, M.R.; Kabbash, I.A.; Metwally, N.M. Early Diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Utilizing Clinical, Radiographic, and Dental Age Indicators. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 12376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesneau, E.D.; McNeill, A.M.; Schary, W.; Pate, V.; Lund, J.L. Prognosis of Older Adults with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare Cohort Study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2023, 14, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehtabcheh, S.; Soleimani Samarkhazan, H.; Asadi, M.; Zabihi, M.; Parkhideh, S.; Mohammadi, M.H. Insights into KMT2A Rearrangements in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: From Molecular Characteristics to Targeted Therapies. Biomark Res 2025, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Iqbal, Q.; Amin, M.K.; Irfan, S.; Warraich, S.Z.; Anwar, I.; Dave, P.; Basharat, A.; Hebishy, A.; Faisal, M.S.; et al. Outcomes of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Primary Plasma Cell Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Leukemia Research 2025, 148, 107640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewska, W.; Zarobkiewicz, M.; Jastrzębska-Pawłowska, K.; Lehman, N.; Tomczak, W.; Mizerska-Kowalska, M.; Bojarska-Junak, A.; Roliński, J. MLR Corresponds to the Functional Status of Monocytes in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. International Journal of Inflammation 2025, 2025, 4443773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Rodríguez, D.; Ibarra-Sánchez, A.; Sosa-Garrocho, M.; Vázquez-Victorio, G.; Caligaris, C.; Anaya-Rubio, I.; Segura-Villalobos, D.; Blank, U.; González-Espinosa, C.; Macias-Silva, M. An Autocrine Regulator Loop Involving Tumor Necrosis Factor and Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand-2 Is Activated by Transforming Growth Factor-β in Rat Basophilic Leukemia-2H3 Mast Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, C.I.; Rodriguez, A.; Torres, V.C.; Sanchez, A.; Torres, A.; Vazquez, A.E.; Wagler, A.E.; Brissette, M.A.; Bill, C.A.; Vines, C.M. C-C Chemokine Receptor 7 Promotes T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Invasion of the Central Nervous System via Β2-Integrins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Ma, L.; Huang, T.; Wang, T.; Zhou, F.; Liu, X. Azelaic Acid Attenuates CCL2/CCR2 Axis-Mediated Skin Trafficking of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells through NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Modulation in Keratinocytes. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lei, L.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Ai, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, G.; et al. Enhanced Venetoclax Delivery Using L-Phenylalanine Nanocarriers in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment. Chinese Chemical Letters 2025, 36, 110316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bosiacki, M.; Stasiak, P.; Snarski, E.; Brodowska, A.; Chlubek, D.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. Clinical Aspects and Significance of β-Chemokines, γ-Chemokines, and δ-Chemokines in Molecular Cancer Processes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) and Myelodysplastic Neoplasms (MDS). Cancers 2024, 16, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Long, Z.; Lei, M.; Ding, R.; Chen, M. Integrated Genomics Reveal Potential Resistance Mechanisms of PANoptosis-Associated Genes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Molecular Carcinogenesis 2025, 64, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, E.; Azoyan, L.; Monzó-Gallo, P.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Lanternier, F.; Brissot, E.; Guitard, J.; Lacombe, K.; Dechartres, A.; Surgers, L. Risk Factors for Invasive Mould Infections in Adult Patients with Hematological Malignancies and/or Stem Cell Transplant: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Infection 2025, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwole, O.O.; Ray, M.D.; Ma, H.; Sharma, R.; Patel, A.R.; Smith, N. Health and Economic Impact of Vein-to-Vein Time in CAR T-Cell Therapy in the Second-Line Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A US Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyi, K.K.; Anuchapreeda, S.; Intasai, N.; Tungjai, M.; Okonogi, S.; Iwasaki, A.; Usuki, T.; Tima, S. Anti-Leukemia Activity of the Ethyl Acetate Extract from Gynostemma Pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Leaf against FLT3-Overexpressing AML Cells and Its Phytochemical Characterization. BMC Complement Med Ther 2025, 25, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalloro, V.; Malacrida, A.; Miloso, M.; Ronchi, D.; Porta, A.; Fossati, A.; Gheza, G.; De Siervi, S.; Mantovani, S.; Oliviero, B.; et al. From Lichen to Organoids: Usnic Acid Enantiomers Show Promise against Cholangiocarcinoma via MNK2 Targeting and MAPK Pathway Modulation. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2025, 188, 118208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javrushyan, H.; Ginovyan, M.; Harutyunyan, T.; Gevorgyan, S.; Karabekian, Z.; Maloyan, A.; Avtandilyan, N. Elucidating the Impact of Hypericum Alpestre Extract and L-NAME on the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma and MDA-MB-231 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0303736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A.; Rascón-Díaz, M.P.; Quintanilla-Carvajal, M.X.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Physicochemical, Technological, and Structural Properties and Sensory Quality of Bread Prepared with Wheat Flour and Pumpkin (Cucurbita Argyrosperma), Chayotextle (Sechium Edule Root) and Jinicuil (Inga Paterno Seeds) Flour. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, E.-S.; María-Guadalupe, R.-P.; Víctor-Manuel, M.-N.; Jorge, C.-Í.; Marcos, S.-H.; Juana, R.-P.; Ernesto, R.-L.; Benny, W.-S.; Graciela, G.-G.; Taide-Laurita, A.-U.; et al. Hepatoprotective Effect of the Sechium HD-Victor Hybrid Extract in a Model of Liver Damage Induced by Carbon Tetrachloride in Mice. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2025, 183, 117831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Aguilar, S.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.D.M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Rivera-Martínez, A.R.; Aguirre-Medina, J.F. Sechium Edule (Jacq.) Swartz, a New Cultivar with Antiproliferative Potential in a Human Cervical Cancer HeLa Cell Line. Nutrients 2017, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Uriostegui-Arias, M.T.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Soto-Hernández, M. Antiproliferative Effect of Sechium Edule (Jacq.) Sw., Cv. Madre Negra Extracts on Breast Cancer In Vitro. Separations 2022, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Íñiguez ,Jorge; Santiago-Osorio ,Edelmiro; Gómez-García ,Guadalupe; Mendoza-Núñez ,Víctor Manuel; Rosado-Pérez ,Juana; Ruíz-Ramos ,Mirna; Cisneros-Solano ,Víctor Manuel; Ledesma-Martínez ,Edgar; Delgado-Bordonave ,Angel de Jesus; et al. Chemical Analyses and in Vitro and in Vivo Toxicity of Fruit Methanol Extract of Sechium Edule Var. Nigrum Spinosum. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 1638–1645. [CrossRef]

- Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Ruíz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Cadena-Zamudio, J.D.; González-Ugarte, A.K.; Weiss Steider, B.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Fruit Extract from A Sechium Edule Hybrid Induce Apoptosis in Leukaemic Cell Lines but Not in Normal Cells. Nutrition and Cancer 2015, 67, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.d.L.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Zamudio, J.D.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Ramírez-Rodas, Y.C.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Salazar-Aguilar, S.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M. Genotypes of Sechium Spp. as a Source of Natural Products with Biological Activity. Life 2025, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Martínez, A.R.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Soto-Cruz, I.; Monroy-García, A.; Gómez-García, G.; Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Weiss-Steider, B.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Fruit Extract of Sechium Chinantlense (Lira & F. Chiang) Induces Apoptosis in the Human Cervical Cancer HeLa Cell Line. Nutrients 2023, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.N.; El-Desouky, M.A.; Shawush, N.A.; Hanna, D.H. Apoptosis Induction in Ascorbic Acid Treated Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines (Caco-2). Journal of Biologically Active Products from Nature 2025, 15, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, D.F.; El-Keey, M.M.; Elgendy, S.M.; Hessien, M. Impregnation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Conditioned Media with Wortmannin Enhanced Its Antiproliferative Effect in Breast Cancer Cells via PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway. BMC Res Notes 2025, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ashafaq, M.; Alshahrani, S.; Qadri, M.; Khardali, A.; Mawkili, W.; Hassan, D.A.; Alam, M.I.; Almoshari, Y.; Elhassan Taha, M.M.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Piperine on Curcumin in Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity through DNA Fragmentation and Cytokines Gene Expressions. Drug and Chemical Toxicology 0, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, H.; Alawam, A.S.; Rudayni, H.A.; Allam, A.A.; Helim, R.; Fafa, S.; Yahia, S.; Mahmoud, R.; Alahmad, W. Emerging Electrochemical Approaches for the Early Detection of Programmed Cell Death. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 34106–34122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, A.-K.; Cheng, R.K.Y.; Tautermann, C.S.; Brauchle, M.; Huang, C.-Y.; Pautsch, A.; Hennig, M.; Nar, H.; Schnapp, G. Crystal Structure of CC Chemokine Receptor 2A in Complex with an Orthosteric Antagonist Provides Insights for the Design of Selective Antagonists. Structure 2019, 27, 427–438.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, Y.; Portugaly, E.; Fromer, M.; Linial, M. Efficient Algorithms for Accurate Hierarchical Clustering of Huge Datasets: Tackling the Entire Protein Space. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, i41–i49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, C.C.; Le, T.L.; Ho, N.Q.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, N.Q.H.; Le, P.C.; Le, N.T.L.; Tran, T.L.G.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Hoang, N.S. Cytotoxic Effects of the Standardized Extract from Curcuma Aromatica Salisb. Rhizomes via Induction of Mitochondria-Mediated Caspase-Dependent Apoptotic Pathway and P21-Mediated G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest on Human Gastric Cancer AGS Cells. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 2025, 88, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarı, U.; Zaman, F.; Özdemir, İ.; Öztürk, Ş.; Tuncer, M.C. Gallic Acid Induces HeLa Cell Lines Apoptosis via the P53/Bax Signaling Pathway. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prades-Sagarra, È.; Geurts, F.A.P.; Biemans, R.; Lieuwes, N.G.; Yaromina, A.; Dubois, L.J. The Radiosensitizing Effect of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester in Breast Cancer Is Dependent on P53 Status. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2025, 209, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feriotto, G.; Tagliati, F.; Giriolo, R.; Casciano, F.; Tabolacci, C.; Beninati, S.; Khan, M.T.H.; Mischiati, C. Caffeic Acid Enhances the Anti-Leukemic Effect of Imatinib on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells and Triggers Apoptosis in Cells Sensitive and Resistant to Imatinib. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorisio, S.; Fierabracci, A.; Cham, B.T.; Hoang, V.D.; Thuy Linh, N.T.; Nhung, L.T.H.; Martelli, M.P.; Ayroldi, E.; Ronchetti, S.; Rosati, L.; et al. Modulatory Effect of Cucurbitacin D from Elaeocarpus Hainanensis on ZNF217 Oncogene Expression in NPM-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jin, X.; An, Y.; Li, W. A Predictive Model Based on Program Cell Death Genes for Prognosis and Therapeutic Response in Early Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 13937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Saxena, A.K.; Agrawal, S.K. Essential Oil from Ocimum Carnosum Induces ROS Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Intrinsic Apoptosis in HL-60 Cells. Toxicology in Vitro 2025, 104, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gu, R.; Tang, M.; Mu, X.; He, W.; Nie, X. Elucidating the Dual Roles of Apoptosis and Necroptosis in Diabetic Wound Healing: Implications for Therapeutic Intervention. BURNS TRAUMA 2025, 13, tkae061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraei, R.; Rahman, H.S.; Soleimani, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Naimi, A.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Solali, S. Kaempferol Sensitizes Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand-Resistance Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Cells to Apoptosis. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, R.; Tadagaki, K.; Yamasaki, K.; Kuwahara, Y.; Nakada, S.; Yoshida, T. The Combination of Venetoclax and Quercetin Exerts a Cytotoxic Effect on Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiya, G.; Ogawa, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Hyodo, F.; Abe, N.; Yuzawa, A.; Takeuchi, H.; Aoyagi, M.; Sato, A.; Yamashita, K.; et al. Real-Time Imaging Reveals Radiation-Induced Intratumor Apoptosis via Nutrient and Oxygen Deprivation Following Vascular Damage. Molecular Therapy Oncology 2025, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Lan, L. Transcription-Coupled DNA Repair Protects Genome Stability upon Oxidative Stress-Derived DNA Strand Breaks. FEBS Letters 2025, 599, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, F. Biological Functions and Health Benefits of Flavonoids in Fruits and Vegetables: A Contemporary Review. Foods 2025, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, W.; Hao, W.; Ren, G.; Lu, J.; Chen, X. Cucurbitacin B Induces DNA Damage, G2/M Phase Arrest, and Apoptosis Mediated by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Leukemia K562 Cells. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 14, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriello, C.; De Rosa, C.; D’Angelo, S.; Pasquale, P. Polyphenols and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Hemato 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lakshmi, B.; K. Bidarur, J.; G. Anilkumar, H.; S. Ravindranath, B. Prioritization of Phytochemical Isolation and Characterization against HER2 as a Breast Cancer Target Based on Chromatographic Methods, DFT Studies, 3D-QSAR Analysis, and Molecular Docking Simulations. RSC Advances 2025, 15, 25103–25114. [CrossRef]

- Millan-Casarrubias, E.J.; García-Tejeda, Y.V.; González-De la Rosa, C.H.; Ruiz-Mazón, L.; Hernández-Rodríguez, Y.M.; Cigarroa-Mayorga, O.E. Molecular Docking and Pharmacological In Silico Evaluation of Camptothecin and Related Ligands as Promising HER2-Targeted Therapies for Breast Cancer. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2025, 47, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cells per quadrant (%) | ||||

| Treatment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Control | 0.1 | 25.1 | 24.2 | 50.7 |

| Vehicle (PBS) | 0.1 | 21.9 | 37.0 | 41.1 |

| Ara-C (Cytarabine®) | 0.4 | 24.7 | 15.1 | 59.8 |

| H-387-07 | 0.0 | 20.8 | 35.2 | 43.9 |

| S. edule var. nigrum spinosum | 3.2 | 77.7 | 11.4 | 8.3 |

| S. compositum | 0.1 | 19.2 | 35.7 | 45.0 |

| S. chinantlense | 0.0 | 17.6 | 30.2 | 52.2 |

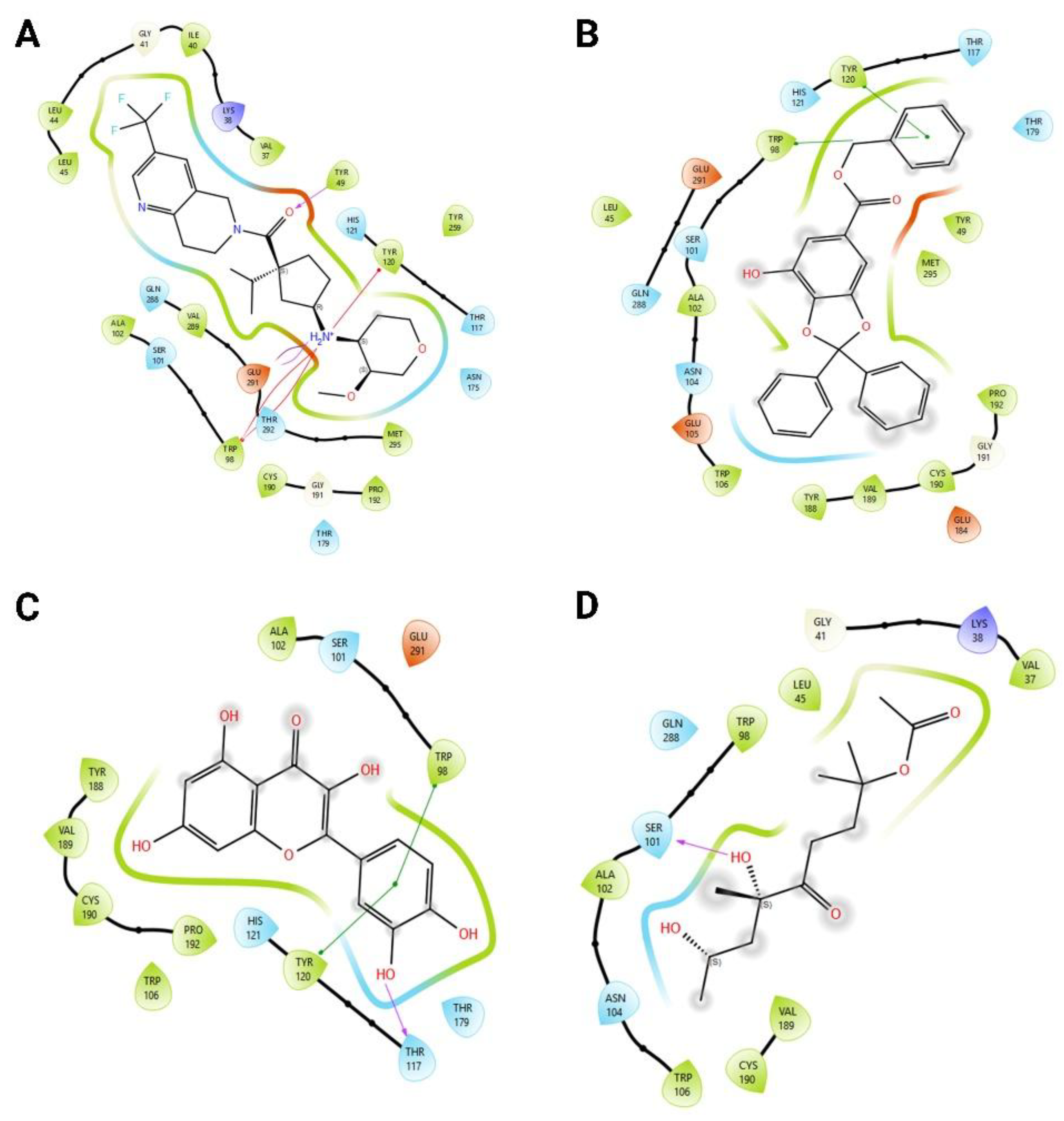

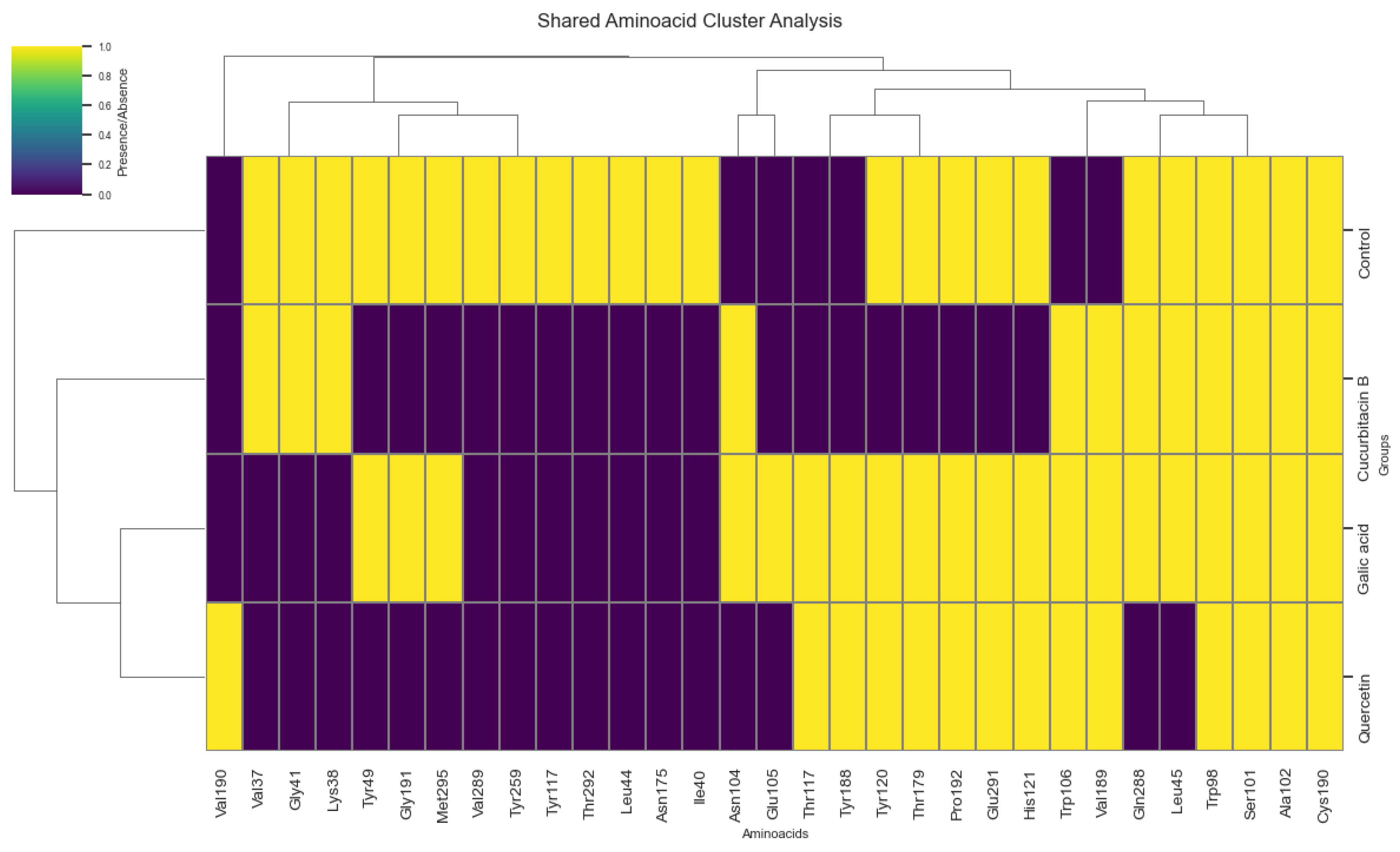

| Ligand | Average (kcal/mol) | Standard deviation | n |

| Gallic acid | -9.49 | 0.001 | 10 |

| Cucurbitacin B | -9.53 | 0.016 | 10 |

| Quercetin | -7.89 | 0.001 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).