1. Introduction

Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) is defined by a bilayered myocardium that recapitulates the fetal pattern: an outer compact layer, thinned and homogeneous, and an inner non-compacted layer formed by prominent trabeculae with deep recesses that communicate with the ventricular cavity (blood-filled endocardial recesses). This allows differentiation from entities with pseudo-recesses or from physiological hyper-trabeculation [

1]. In LVNC, compaction failure persists: both layers coexist beyond the neonatal period, with apical and mid-inferolateral predominance of the non-compacted pattern. The phenotype may associate with systolic dysfunction and arrhythmias or be incidental; therefore, interpretation must always be integrated with function and family/clinical context to avoid over-diagnosis [

2].

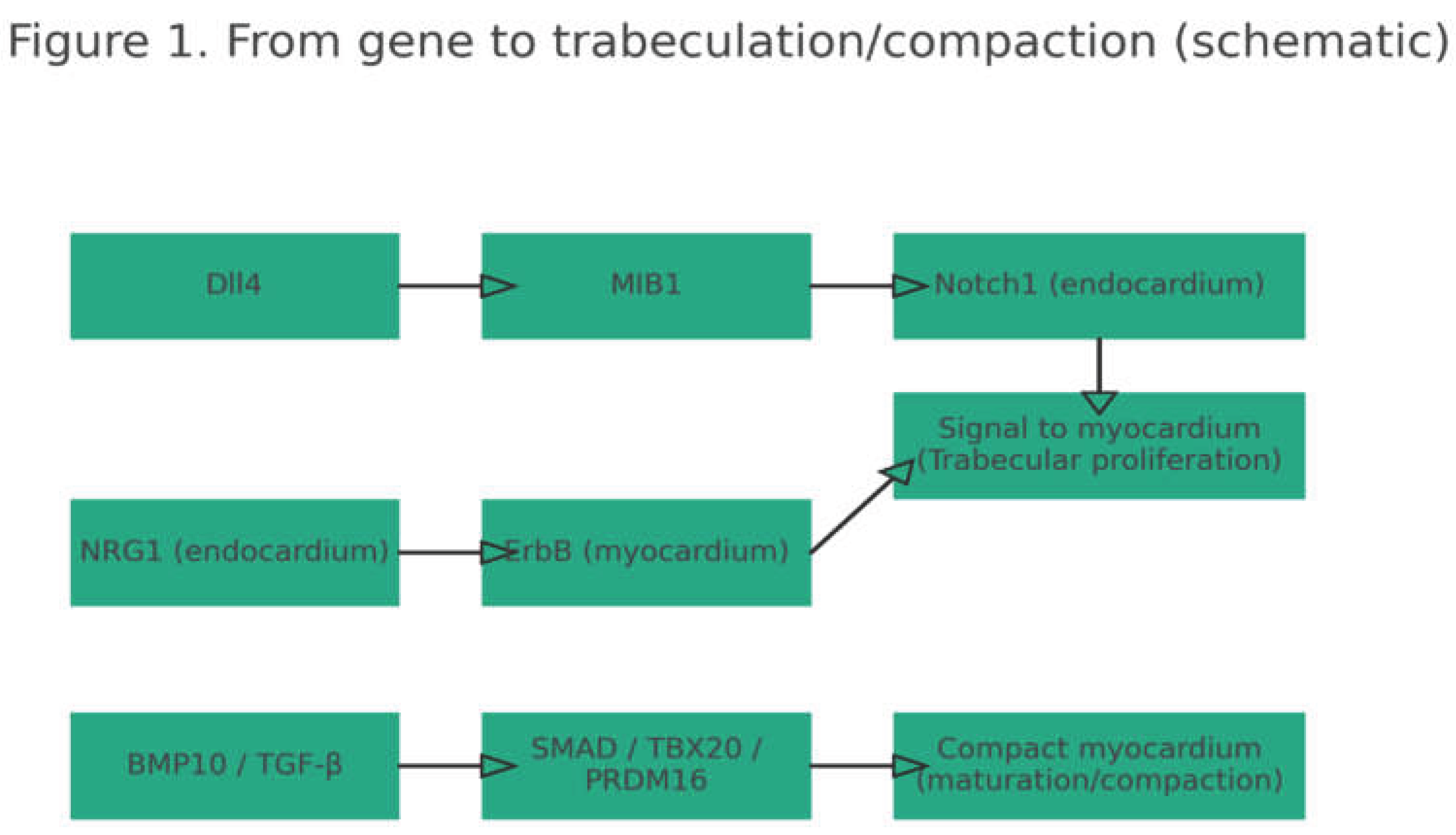

In normal development the embryonic ventricle is initially spongy: the wall is formed by trabeculae (internal ridges) and deep recesses that facilitate blood exchange before the coronary circulation exists. Trabeculation depends on endocardial–myocardial signaling; key axes are Notch—sequentially activated by the Dll4 ligand, the E3 ligase MIB1, and the NOTCH1 receptor—and the neuregulin-1/ErbB and BMP10 pathways, which promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and organize trabecular patterning [

3,

4,

9,

10]. As gestation advances, compaction begins: the outer ventricular wall thickens and homogenizes while recess depth decreases. This step requires epicardial expansion and paracrine signals (e.g., retinoic acid, erythropoietin, IGF-1) that promote maturation of the compact myocardium [

4,

5]. When these routes are interrupted, the wall does not complete its maturation and a bilaminar pattern typical of LVNC persists; in murine models, loss of Mib1 (Notch), Jarid2 (transcriptional regulation), or Ino80 (chromatin remodeling) reproduces compaction defects and can be lethal in early stages [

6].

Genetically, early studies linked the phenotype to sarcomeric genes (TAZ/TAFAZZIN, MYH7, ACTN2, TTN), shared with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies [

7]. Recent reviews synthesize ~189 associated genes, with 11 of definitive evidence and 21 of moderate evidence; these encompass sarcomeric proteins, transcriptional/epigenetic regulators, mitochondrial proteins, cytoskeletal elements, and ion channels; approximately 56% appear in syndromic presentations, reflecting pleiotropy [

8]. Even so, about 50% of families lack an identified causal variant, suggesting undiscovered genes and polygenic/epigenetic contributions [

7,

8].

Against this background, the aims of this review are: (i) to explain how embryogenesis and genetics produce the LVNC phenotype; (ii) to present useful genotype–phenotype correlations; and (iii) to translate these insights into clinical decisions (diagnosis, arrhythmic risk, family screening, and emerging treatments), integrating developmental biology with contemporary genomics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

2. Materials and Methods

Design and scope. We conducted a narrative review focused on the genetics and developmental biology of LVNC, with emphasis on clinical utility (diagnosis, arrhythmic risk, family screening, and therapeutic decisions).

Sources and time frame. Searches in PubMed, Google Scholar, and CrossRef (January 2000–July 2024), without language restriction when an English abstract was available. Reference lists of included articles were hand-searched (“snowballing”).

Search terms. Combinations of: “left ventricular non-compaction”, “LVNC”, “non-compaction cardiomyopathy”, “trabeculation”, “compaction”, “embryogenesis”, “Notch”, “Dll4”, “MIB1”, “neuregulin/ErbB”, “BMP10”, “TGF-β”, “sarcomeric”, “mitochondrial”, “cytoskeletal”, “ion channel”, “genetic architecture”, “panel”, “exome”, “risk stratification”.

Human genetic studies (families, panels, exome/genome) with LVNC phenotype.

Mechanistic/animal/cellular models linking trabeculation/compaction to Notch/NRG1-ErbB/BMP routes or epigenetic regulators [

3,

4,

5,

6,

9,

10].

Clinical reviews/consensus/guidelines and imaging research with clinical implications (e.g., CMR/echo criteria, LGE, T1/ECV, N/C, fractal).

Isolated case reports without genetic or mechanistic contribution.

Editorials or letters without data.

Series with ambiguous cardiomyopathy phenotypes not defining LVNC.

Extraction and synthesis. From each article we captured: implicated genes; functional category (sarcomeric, transcription/epigenetic, mitochondrial, cytoskeleton, channels/signaling); design; population (pediatric/adult); and clinical–imaging correlates (arrhythmias, LVEF, LGE) [

2,

8,

13].

Quality and editorial notes. Although narrative (non-meta-analytic), we prioritized post-2010 sources, retained developmental “classics” to anchor mechanisms [

3,

4,

5,

6,

9,

10], and verified DOI/PMID when available. Reference order follows appearance in the text [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] and MDPI style (citations [n] inside punctuation).

3. Results

Genetic Architecture and Signaling Pathways

LVNC does not arise from a single gene or route but from the convergence of several processes: sarcomeric structure, transcriptional/epigenetic programs, mitochondrial bioenergetics, cytoskeletal integrity, and signaling/ion-channel biology [

2,

8]. Recent syntheses assemble ~189 associated genes, with 32 supported by strong evidence (11 definitive and 21 moderate) [

8]. For clinicians this implies two things: (i) heterogeneity (distinct molecular “entries” can produce a similar phenotype), and (ii) overlap with other cardiomyopathies (many sarcomeric genes are shared) [

2,

7,

8].

Functional distribution. Among genes with the strongest evidence, sarcomeric account for 34%, transcription/translation regulators 19%, mitochondrial 9%, cytoskeletal 9%, and “other” (signaling/channels) 29% [

2,

8]. This distribution supports a multi-pathway model: perturbing the contractile scaffold, gene-programming, metabolism, cytoskeleton, or signaling can halt compaction and leave a “spongy” ventricle.

Developmental routes. The Notch pathway (Dll4 ligands, activation by MIB1, Notch1 receptor) is essential for trabeculation and its patterning; MIB1 variants reduce Notch1 activity and have been linked to autosomal-dominant LVNC and related phenotypes in models [

3]. TBX20 and PRDM16 modulate TGF-β/SMAD, promoting trabecular proliferation and progression toward a compact wall [

5]. Neuregulin-1/ErbB drives proliferation and matrix remodeling [

9]; BMP10 maintains cardiomyocyte proliferation and enables timely compaction [

10]. From an epigenetic perspective, BRG1, TET2/TET3, and INO80 act as chromatin “switches” integrating these signals; their loss in murine models produces LVNC-like phenotypes and often embryonic lethality [

6].

Gene-by-gene perspective.

Sarcomeric: MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2, TPM1, TTN (truncating). These explain overlap with HCM/DCM and adult variability [

8].

Cytoskeletal: DMD, LMNA, DES. Point to neuromuscular/laminopathy contexts (watch for conduction/arrhythmia in LMNA) [

11].

Mitochondrial: TAZ, NNT, TMEM70. Often pediatric and syndromic with metabolic vulnerability [

12].

Signaling/channels: MIB1, ALPK3, HCN4, SCN5A. Link development with electrophysiology; HCN4 relates to bradycardia/conduction and has higher diagnostic yield in pediatrics [

8,

11].

For the practicing clinician, the key is translating gene cues into clinical signals: if conduction disease/arrhythmias and fibrosis are present on CMR, think LMNA; in a child with developmental delay/syndromic features, consider mitochondrial genes or PRDM16; with bradycardia plus LVNC, consider HCN4. This guides panel choice and cascade screening [

11,

12].

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of key pathways in ventricular trabeculation/compaction: Notch (Dll4->MIB1->Notch1), NRG1/ErbB, and BMP10/TGF-β (SMAD/TBX20/PRDM16). The figure highlights the sarcomeric burden and the diversity of other categories. Clinically: roughly one-third of strong evidence falls on contractile genes, but nearly two-thirds involve gene-programming, metabolism, cytoskeleton, and signaling—hence the broad phenotypic expression and frequent overlap with other cardiomyopathies [

2,

8].

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of key pathways in ventricular trabeculation/compaction: Notch (Dll4->MIB1->Notch1), NRG1/ErbB, and BMP10/TGF-β (SMAD/TBX20/PRDM16). The figure highlights the sarcomeric burden and the diversity of other categories. Clinically: roughly one-third of strong evidence falls on contractile genes, but nearly two-thirds involve gene-programming, metabolism, cytoskeleton, and signaling—hence the broad phenotypic expression and frequent overlap with other cardiomyopathies [

2,

8].

Table 1.

Functional categories in LVNC. Adapted from [

2,

13]. Note: percentages refer to the proportion of strong-evidence genes, not patient prevalence [

8].

Table 1.

Functional categories in LVNC. Adapted from [

2,

13]. Note: percentages refer to the proportion of strong-evidence genes, not patient prevalence [

8].

| Functional category |

Representative examples |

Approx. frequency (%) |

Typical inheritance |

| Sarcomeric |

MYH7; MYBPC3; TNNT2; TPM1; TTN (trunc.) |

34 |

AD |

| Transcription/Translation |

NKX2-5; TBX5; PRDM16; RBM20 |

19 |

AD (variable penetrance) |

| Mitochondrial |

TAZ; NNT; TMEM70 |

9 |

X-linked / AR |

| Cytoskeletal |

DMD; LMNA; DES |

9 |

X-linked (DMD) / AD (LMNA) / AD/AR |

| Signaling / Ion channels |

MIB1; ALPK3; HCN4; SCN5A |

29 |

AD (variable) |

Functional categories of genes associated with LVNC: representative examples, approximate frequency, and typical inheritance. Adapted from Hirono & Ichida 2022 [

2] and Rojanasopondist et al. 2022 [

13]. The table summarizes the genetic architecture of LVNC by grouping genes with strong evidence into five functional categories and, for each, listing representative examples, the approximate proportion contributed within the set of 32 strong-evidence genes (11 definitive and 21 moderate), and the typical inheritance pattern; these percentages reflect the distribution of genes across categories, not patient prevalence [

8]. Practically, the sarcomeric predominance (34%) explains overlap with HCM/DCM; transcription/translation regulators (19%) associate with variable penetrance and developmental traits; mitochondrial (9%) and cytoskeletal (9%) genes point toward pediatric, syndromic, or neuromuscular presentations; and the signaling/ion-channel category (29%) integrates developmental (e.g., Notch) and electrophysiologic pathways [

2,

13]. This stratification helps select panels (e.g., prioritize LMNA/SCN5A in conduction disease, HCN4 in sinus bradycardia, TAZ/NNT/TMEM70 in metabolic phenotypes), anticipate inheritance (AD vs X-linked/AR), and plan cascade screening and genetic counseling [

2,

13]. As a limitation, heterogeneity within groups and the likely addition of new genes require interpreting the table in clinical–imaging–genotype context and updating it as evidence emerges [

8,

13].

Table 2.

Quick gene–phenotype map (LVNC).

Adapted from [14,17,19,20,22]. Examples are not exhaustive; penetrance/expressivity vary.

Table 2.

Quick gene–phenotype map (LVNC).

Adapted from [14,17,19,20,22]. Examples are not exhaustive; penetrance/expressivity vary.

| Gene |

Key clinical cues |

Typical imaging (CMR) |

Immediate clinical implication |

| LMNA |

Conduction disease; VT/VF risk |

Diffuse LGE |

Consider early ICD if fibrosis/LGE |

| HCN4 |

Sinus bradycardia; pediatric |

Mild/variable |

Rhythm/conduction surveillance |

| TTN (trunc.) |

Systolic dysfunction; adult |

Dilated LV; ↓LVEF |

HF therapy; screen relatives |

| DMD |

Myopathy; symptomatic female carriers |

Variable LGE |

Family screening; genetics |

| TAZ |

Pediatric; metabolic/mitochondrial |

Cardiomyopathy + systemic signs |

Multisystem care |

| PRDM16 |

Developmental cardiac phenotype |

Abnormal trabeculation |

Refer to genetics center |

| MIB1 |

Notch-linked non-compaction |

Altered trabeculation/compaction |

Targeted screening; counseling |

Quick gene–phenotype map for LVNC linking frequent genes (left) to their clinical “red flags,” typical CMR findings, and the immediate practical implication (right). The goal is to help prioritize panels and guide follow-up/ICD decisions without replacing clinical–imaging–genotype correlation. LMNA commonly presents with conduction disease/ventricular tachyarrhythmias and diffuse LGE; early ICD may be appropriate when LGE or overt fibrosis is present. HCN4 associates with sinus-node dysfunction (sometimes aortic dilation) and typically requires rhythm/conduction surveillance. Truncating TTN variants relate to systolic dysfunction and dilated phenotypes in adults, guiding heart-failure care and family evaluation. DMD indicates a neuromuscular/carrier context, with variable CMR and the need for family screening and counseling. TAZ signals pediatric/metabolic presentations requiring multisystem follow-up. PRDM16 appears in developmental phenotypes with trabeculation anomalies, warranting referral to clinical genetics. MIB1 integrates Notch-linked LVNC (altered trabeculation/compaction) and supports targeted screening. Examples are not exhaustive and penetrance/expressivity vary; proposed actions must be integrated with LVEF, LGE, age, and family context and updated with new evidence [

14,

17,

19,

20,

22].

4. Discussion

Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

Correlations vary by age and clinical setting. In pediatrics, the probability of identifying a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is high; in adults with isolated LVNC, the yield is lower [

14,

19]. In addition, specific clinical cues point toward gene categories (e.g., conduction disease/arrhythmias suggests LMNA; bradycardia in young patients suggests HCN4; metabolic signs in children suggest TAZ or other mitochondrial genes) [

11,

12].

Pediatric cohorts. In a multicenter series (n≈31), pathogenic variants were identified in ~52%, notably in HCN4, MYH7, PRDM16, ACTC1, ACTN2, and truncating TTN; carriers had more arrhythmias, thromboembolic events, and mortality than non-carriers, underscoring the prognostic value of genetics in this group [

14]. Clinically, in children with LVNC and functional impairment or extracardiac features, genetic testing is seldom incidental—it informs surveillance and cascade screening.

Adult cohorts. In adult series with isolated LVNC, yield decreases (~9–10%); variants occur in NKX2-5, TBX5, PRDM16, more often when ventricular dysfunction or syndromic traits are present [

19]. This difference suggests reduced penetrance, environmental/hemodynamic modifiers, or yet-unidentified loci that dilute a monogenic signal; thus panel selection and expectations should be adjusted to age and phenotype [

19].

Syndromic/neuromuscular forms. LVNC can be part of complex syndromes: deletions 1p36, 22q11.2, 8p23.1; lysosomal/neurodevelopmental disorders (LAMP2 in Danon; RPS6KA in Coffin–Lowry); neuromuscular (DMD and carriers), among others [

21,

29,

30]. In these contexts, extracardiac suspicion raises pre-test probability and prioritizes specific genes/studies.

5. Conclusions

Clinical Implications and Precision Medicine

Echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) are diagnostic pillars, but over-diagnosis is common due to heterogeneous criteria; therefore, trabecular morphology must be interpreted in context with ventricular function, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), and family history, not by ratios alone [

27,

29]. A diastolic N/C threshold >2.3 (or >2.3–2.5 in systole) is used pragmatically, yet with limited specificity [

27,

29]. Quantitative techniques such as fractal analysis may help in borderline cases, but decisions should rest on combined clinical–imaging evidence [

30].

Practical interpretation pathway. In LVNC, variant interpretation should: (i) define the phenotype (isolated vs syndromic LVNC, systolic dysfunction, arrhythmias); (ii) prioritize panels according to age and features (sarcomeric, developmental regulators, mitochondrial) [

7,

13,

19]; (iii) apply population filters and predictors, incorporating segregation; and (iv) reclassify with functional data and/or family follow-up, communicating uncertainty when appropriate [

17,

25].

In practice, genetic testing is recommended when LVNC coexists with ventricular dysfunction, clinically significant arrhythmias, growth delay, or syndromic features; results inform genetic counseling, cascade screening, and risk prediction [

27,

28]. A negative panel does not exclude LVNC, and many findings are variants of uncertain significance (VUS); they require correlation with phenotype and segregation [

22,

23]. Age and context modulate yield and implications (higher in pediatrics; lower in isolated adult forms), arguing for phenotype-guided panels and targeted follow-up of at-risk relatives [

19,

27,

28].

A precision-medicine framework integrates imaging (function, LGE, quantitative metrics), biomarkers (troponin, NT-proBNP), history, and genotype to refine prognosis and therapy. Carriers of truncating variants in LMNA, MIB1, or MYBPC3 with extensive fibrosis may merit earlier ICD, while others can be managed with risk-adjusted surveillance [

19,

22]. Targets under exploration include Notch modulation and mitochondrial biogenesis, together with SGLT2 inhibitors in LVNC with systolic dysfunction; as evidence matures, treatment will align with pathway-defined endotypes [

22].

Table 3.

“Checklist” for referral to genetics in LVNC.

Adapted from [20,22,25,27,28,29,30].

Table 3.

“Checklist” for referral to genetics in LVNC.

Adapted from [20,22,25,27,28,29,30].

| Criterion |

Indicators |

| Ventricular dysfunction or LGE |

LVEF ↓; fibrosis on CMR |

| Significant arrhythmias |

VT/AF/CPVT; unexplained syncope |

| Pediatric onset or syndromic features |

Growth delay; extracardiac signs |

| Family history |

SCD/cardiomyopathy in 1st-degree relatives |

| Conduction abnormality / myopathy |

Suspect LMNA / DMD / DES |

| Congenital defects / chromosomal del. |

1p36; 22q11.2; 8p23.1 |

Checklist for genetics referral in LVNC: criteria and indicators. Adapted from Hoedemaekers 2010 [

20], guidelines/consensus documents [

25,

27], and imaging/prognosis studies [

22,

28,

29,

30]. It operationalizes referral: any of these criteria should trigger genetic consultation and guide panel selection, with realistic expectations regarding VUS and age-dependent yield [

20,

22,

27]–[

30].

Extracardiac Manifestations and Clinical “Red Flags”

A relevant proportion of genes linked to LVNC occur in multisystem syndromes; thus the phenotype may include extracardiac features—especially neuromuscular and neurocognitive—and chromosomal deletions [

8,

11,

12,

21,

29,

30]. Established associations include: DMD (Duchenne muscular dystrophy/carriers) with proximal weakness, elevated CK, and risk of cardiomyopathy/conduction disease; LMNA (laminopathies) with myopathy, contractures, and conduction block/tachyarrhythmias; LAMP2 (Danon disease, X-linked) with myopathy, variable cognitive deficit, and pre-excitation; mitochondrial genes such as TAZ (Barth syndrome), TMEM70, or NNT, with hypotonia, exercise intolerance, failure to thrive, and multisystem involvement; and deletions 1p36, 22q11.2, 8p23.1, which combine congenital anomalies and neurodevelopmental traits with LVNC [

11,

12,

21,

29,

30].

When to suspect syndromic/neuromuscular forms (refer to Genetics/Neurology):

Pediatric age with developmental delay, hypotonia, or cognitive deficit [

14,

21].

Proximal weakness, myopathy, exercise intolerance, or elevated CK; female carriers of DMD with cardiac findings [

11].

Early conduction abnormalities, marked bradycardia, or pre-excitation (suspect LMNA or LAMP2) [

11,

29].

Multi-organ dysfunction or dysmorphic features; family history compatible with X-linked or autosomal-dominant inheritance [

12,

21,

29].

Congenital heart disease plus LVNC in the same patient (consider chromosomal deletions) [

21,

30].

Table 4.

Extracardiac “red flags” and likely etiology in LVNC.

Adapted from [11,12,21,29,30].

Table 4.

Extracardiac “red flags” and likely etiology in LVNC.

Adapted from [11,12,21,29,30].

| Clinical/extracardiac red flag |

Likely etiology / orienting genes |

| Proximal weakness; ↑CK; symptomatic carriers |

DMD (X-linked) |

| Conduction disease; tachyarrhythmias; contractures |

LMNA (AD) |

| Pre-excitation/WPW; variable cognitive deficit; myopathy |

LAMP2 (Danon, X-linked) |

| Hypotonia; failure to thrive; neutropenia/metabolic traits |

TAZ (Barth); TMEM70; NNT |

| Dysmorphic traits; associated congenital heart disease |

1p36; 22q11.2; 8p23.1 deletions |

| Marked sinus bradycardia (pediatrics) |

HCN4 (AD; conduction) |

Practical implications. When these indicators are present, prioritize panels that combine sarcomeric with developmental/mitochondrial/lamin/lysosomal genes according to age and phenotype; coordinate Neurology and Clinical Genetics; arrange cascade screening if a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is identified; and plan follow-up with conduction/arrhythmia monitoring when suggested by the gene (e.g., LMNA, HCN4) [

11,

12,

22,

29,

30].

6. Limitations

This narrative review summarizes evidence up to July 2024; studies published thereafter were not systematically included. Heterogeneity of designs (gene panels versus exome/genome; small sample sizes; disparate imaging criteria) makes it difficult to compare variant frequencies and outcomes across studies [

2,

8]. Many gene–phenotype links arise from small cohorts or single centers and lack functional validation, limiting causal inference (e.g., VUS classifications that may change over time) [

22,

23]. Population representation is uneven (predominantly European/Asian), affecting allele-frequency filters and penetrance estimates; extrapolation to other ancestries should therefore be cautious [

8,

20]. In imaging, multiple N/C criteria and thresholds coexist (echo vs CMR; variable use of LGE, T1/ECV, and quantitative metrics such as GLS or fractal), which favors over- or under-diagnosis if used in isolation [

27,

29,

30]. Hemodynamic factors (e.g., pregnancy, intense training) can induce reversible hyper-trabeculation, introducing phenotypic confusion if reassessment is not performed after the trigger resolves [

2]. Finally, because this is not a meta-analysis, we did not perform a formal risk-of-bias assessment or quantitative synthesis; figures and tables adapt sources for readability and may simplify complex datasets [

2,

8,

27,

28,

29,

30].

7. Discussion

LVNC exemplifies the convergence of developmental programs and heterogeneous genetic architecture: perturbing Notch, NRG1/ErbB, or BMP10 halts the transition from a spongy ventricle to a compact wall in experimental models, and loss of epigenetic regulators (e.g., BRG1, TET2/TET3, INO80) reproduces non-compaction phenotypes with embryonic lethality in animals [

3,

4,

5,

6,

9,

10]. In humans, although sarcomeric genes contribute the most visible share—and explain overlap with HCM/DCM—developmental signaling and mitochondrial/cytoskeletal mechanisms add alternative routes to a shared phenotype [

2,

7,

8]. For non-specialist clinicians, the practical consequence is to avoid binary decisions based solely on N/C: integrating systolic function (LVEF), fibrosis (LGE), and tissue markers (T1/ECV) helps distinguish physiology (e.g., athletes, pregnancy) from pathology, particularly when symptoms, arrhythmias, or family history are present [

27,

29].

Genotype–phenotype correlations are age- and context-dependent: genetic yield is higher in pediatrics (~50%) than in adults with isolated LVNC (~10%), suggesting reduced penetrance, non-genetic modifiers, and undiscovered genes [

14,

19]. This gradient shapes panel selection, consent (VUS management), and family screening strategies. Certain clinical signals orient molecular suspicion: conduction disease/arrhythmias and fibrosis → LMNA; bradycardia in young patients → HCN4; pediatric metabolic syndrome → TAZ or other mitochondrial genes; and if syndromic features are present (1p36, 22q11.2, 8p23.1 deletions), prioritize genomic/targeted testing [

11,

12,

21,

29,

30].

Risk stratification should combine quantitative imaging (LVEF, LGE, T1/ECV, GLS, trabeculated mass/volume; fractal analysis when morphology is borderline), family history, and genotype. High arrhythmic-risk subgroups (e.g., truncating LMNA with diffuse fibrosis) may benefit from earlier ICD, whereas others require structured follow-up and first-degree cascade screening [

19,

22]. Regarding therapies, most remain preclinical (Notch/TGF-β modulation, mitochondrial biogenesis), while shared heart-failure strategies (e.g., SGLT2 inhibitors) are being explored in LVNC with systolic dysfunction [

22].

8. Conclusions

Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy arises from alterations in embryonic developmental programs and a heterogeneous genetic architecture, in which sarcomeric mutations are prominent but pathways such as Notch, BMP, epigenetic regulators (BRG1, TET2/TET3), and mitochondrial/cytoskeletal genes also contribute. This complexity explains both overlap with other cardiomyopathies and phenotypic variability.

Diagnosis requires a multiparametric approach: integration of quantitative imaging (LVEF, LGE, T1/ECV, GLS), clinical context (symptoms, arrhythmias, family history), and genetics. Genetic yield is higher in pediatrics (~50%) than in adults with isolated LVNC (~10%), reflecting incomplete penetrance and yet-unidentified genes. Specific findings (fibrosis, arrhythmias, syndromic traits) orient toward specific genes (LMNA, HCN4, TAZ).

Risk stratification should combine genotype, imaging, and clinical data to guide decisions (e.g., ICD in LMNA carriers with fibrosis). Future priorities include harmonizing diagnostic criteria, discovering new genes, and developing pathway-directed therapies (Notch/TGF-β, mitochondrial biogenesis). Multidisciplinary collaboration (cardiologists, geneticists) is essential to optimize management and cascade family screening [

2,

8,

22,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Author Contributions

L.E.M.T. conceived and drafted the manuscript; X.B.H. provided methodological oversight and critical review; E.K. reviewed clinical content and added substantive comments; F.R.C. assisted in the final review and incorporated tutor suggestions. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Notch (signaling pathway): Conserved cell-signaling route (NOTCH receptors and Delta/Jagged ligands) that regulates cardiac proliferation and differentiation; key for trabeculation and compaction.

Dll4 (Delta-like ligand 4): Endothelial/endocardial Notch ligand that activates NOTCH1 and coordinates trabecular growth.

MIB1 (Mindbomb-1): E3 ubiquitin ligase that facilitates endocytosis of Notch ligands and enhances pathway activation; variants can associate with LVNC.

-

Trabeculation (ventricular): Formation of internal myocardial ridges and deep recesses in the embryonic ventricle that improve exchange before coronary perfusion develops.

Myocardial compaction: Thickening and maturation of the compact ventricular layer that reduces sponginess; its disruption is associated with LVNC.

Endocardium / Myocardium / Epicardium: Inner lining / contractile middle layer / outer layer contributing vessels and paracrine signals for compaction.

NRG1/ErbB (Neuregulin-1/ErbB): Endocardial–myocardial signaling that stimulates trabecular proliferation and matrix remodeling during development.

BMP10 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 10): Morphogen essential to maintain embryonic cardiomyocyte proliferation and progression toward compaction.

TGF-β / SMAD: Signaling axis that modulates proliferation and differentiation; interacts with factors such as TBX20 and PRDM16.

TBX20: T-box transcription factor involved in cardiac morphogenesis; regulates ventricular proliferation and differentiation programs.

PRDM16: Transcriptional/epigenetic regulator associated with cardiac development and non-compaction phenotypes.

INO80: Chromatin-remodeling complex that controls DNA accessibility; its loss in murine models causes non-compaction phenotypes.

BRG1 (SMARCA4): ATPase of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex required for state transitions during cardiogenesis.

TET2 / TET3: Dioxygenases promoting active demethylation (5hmC); their disruption affects ventricular maturation.

HCN4: Pacemaker ion channel (I_f) associated with bradycardia/conduction disease; implicated in pediatric LVNC phenotypes.

TTN / TTNtv: Titin gene; TTNtv = truncating variants, frequent in cardiomyopathies and present in LVNC subgroups.

LMNA: Nuclear lamins A/C; variants entail conduction disease, arrhythmias, and higher arrhythmic risk (consider earlier ICD as context dictates).

DMD: Dystrophin; Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy and female carriers with cardiac involvement including LVNC.

TAZ (tafazzin): Mitochondrial cardiolipin gene (Barth syndrome); pediatric LVNC with multisystem involvement.

LGE (Late Gadolinium Enhancement / RTG): Late gadolinium enhancement on CMR; marker of fibrosis and worse prognosis.

LVEF: Left-ventricular ejection fraction; key parameter for systolic function and risk stratification.

VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance): Genetic variant with uncertain meaning; requires phenotype correlation, segregation, and/or functional studies.

Pathogenic / Likely pathogenic: ACMG/AMP categories for variants with sufficient evidence of causality.

Penetrance / Variable expressivity: Probability of expressing a phenotype given a genotype / variation in clinical severity or features.

Cascade screening: Stepwise testing of first-degree relatives (and beyond) once the causal variant is identified in the proband.

Multigene panel / Exome: Sequencing approaches for multiple candidate genes or all coding regions.

ACMG/AMP criteria: Standardized framework to classify variants (pathogenic ↔ benign) integrating multiple evidence lines.

Trabeculation endophenotype / Fractality: Quantitative metrics of trabecular pattern (e.g., fractal analysis) aiding physiological vs pathological discrimination.

ICD: Implantable cardioverter–defibrillator; indicated in high arrhythmic-risk subgroups (e.g., LMNA + fibrosis).

SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i): Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; under exploration for systolic dysfunction, including LVNC contexts.

References

- Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy. Springer, 2019. Chapter on genetics and embryology of noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Google Scholar.

- Hirono, K.; Ichida, F. Left ventricular non-compaction: a disorder with genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity—a narrative review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2022, 12, 495–515. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Luxán, G.; Casanova, J.C.; Martínez-Poveda, B.; et al. Mutations in the NOTCH pathway regulator MIB1 cause left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Nat Med 2013, 19, 193–201. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, G.; Luxán, G.; del Monte-Nieto, G.; et al. Sequential Notch activation regulates ventricular chamber development. Nat Cell Biol 2016, 18, 7–20. CrossRef. Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Kodo, K.; Ong, S.G.; Jahanbani, F.; et al. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reveal abnormal TGF-β signalling in left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(10):1031–1042. CrossRef. Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Mysliwiec, M.R.; Carlson, C.D.; Tietjen, J.; Lee, Y.; Ross, J.; et al. Endothelial Jarid2/Jumonji is required for normal cardiac development and proper Notch1 expression. J Biol Chem 2011;286(19):17193–17204 CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Rojanasopondist, P.; Nesheiwat, L.; Piombo, S.; Porter, G.A.; Ren, M.; Phoon, C.K.L. Genetic basis of left ventricular non-compaction. Circ Genom Precis Med 2022, 15, e003517. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.F.; Simon, H.; Chen, H.; Bates, B.; Hung, M.-C.; Hauser, C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature 1995;378:394–398 CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, S.; Acosta, L.; et al. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development 2004;131(9):2219–2231. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar. [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.J.; Moore, R.A.; Taylor, M.D.; et al. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy carriers. J Cardiol Cases 2014, 11, 7–9. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Vershinina, T.; Fomicheva, Y.; Muravyev, A.; et al. Genetic spectrum of left ventricular non-compaction in pediatric patients. Cardiology 2020, 145, 746–756. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Ziętkiewicz, M.; Jurkiewicz, D.; et al. Genetic profile of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy in children—A single reference centre experience. Genes 2022, 13, 1711. CrossRef PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Mazzarotto, F.; Hawley, M.H.; Beekman, L.; et al. Systematic large-scale assessment of the genetic architecture of LVNC reveals diverse etiologies. Genet Med 2021, 23, 856–864. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Miszalski-Jamka, K.; Jefferies, J.L.; Mazur, W.; et al. Novel genetic triggers and genotype–phenotype correlations in patients with left ventricular non-compaction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2017, 10, e001763. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Lu, Y.; Jia, S.; Luo, S. Recent advancements in the molecular genetics of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Clin Chim Acta 2017, 465, 41–52. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J. Cardiogenetics, neurogenetics, and pathogenetics of left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Pediatric Cardiology. 2009;30(5):659–681. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar. [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.B.; Singer, E.S.; Driscoll, E.; et al. Genetic architecture of left ventricular non-compaction in adults. Hum Genome Var 2020, 7, 33. CrossRef. Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Gerecke, B.J.; Engberding, R. Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy—History and Current Knowledge for Clinical Practice. J Clin Med 2021;10(11):2457. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Digilio, M.C.; Bernardini, L.; Gagliardi, M.G.; Versacci, P.; Baban, A.; Capolino, R.; Dentici, M.L.; Roberti, M.C.; Angioni, A.; Novelli, A.; Marino, B.; Dallapiccola, B. Syndromic non-compaction of the left ventricle: associated chromosomal anomalies. Clin Genet. 2013;84(4):362–367.CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Hoedemaekers, Y.M.; Caliskan, K.; Michels, M.; Frohn-Mulder, I.; van der Smagt, J.J.; Phefferkorn, J.E.; Wessels, M.W.; ten Cate, F.J.; Sijbrands, E.J.; Dooijes, D.; Majoor-Krakauer, D. The importance of genetic counseling, DNA diagnostics, and cardiologic family screening in left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3(3):232–239. CrossRef Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.; et al. The trouble with trabeculation: how genetics can help to unravel a complex and controversial phenotype. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2023, 16, 1310–1324. CrossRef. Google Scholar PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, C.; Casas, G.; Martin-Isla, C.; et al. Radiomics-based classification of left ventricular non-compaction, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy by cardiac magnetic resonance. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 764312. DOI: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.764312. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, A.N.; Patel, N.; Kaka, N.; et al. Precision medicine and the future of cardiovascular diseases: a clinically oriented comprehensive review. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 1799. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599–3726. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- European Heart Rhythm Association; Heart Rhythm Society; Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society; Latin American Heart Rhythm Society. Expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for cardiac diseases. Europace 2022, 24, 1307–1367. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Casas, G.; Rodríguez-Palomares, J.F.; Ferreira-González, I. Left ventricular non-compaction: a disease or a phenotypic trait? Rev Esp Cardiol 2022, 75, 1059–1069. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Pittorru, R.; Corrado, D.; et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: evolving concepts. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5674. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Sun, R.; Liu, W.; et al. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in left ventricular non-compaction: a multicenter study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2457. CrossRef. Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.; Doimo, S.; Ricci, F.; et al. Prognostic significance of left ventricular non-compaction: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 13, e009712. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Captur, G.; Muthurangu, V.; Cook, C.; et al. Quantification of left ventricular trabeculae using fractal analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013, 15, 36. CrossRef Google Scholar. PubMed. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).