Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

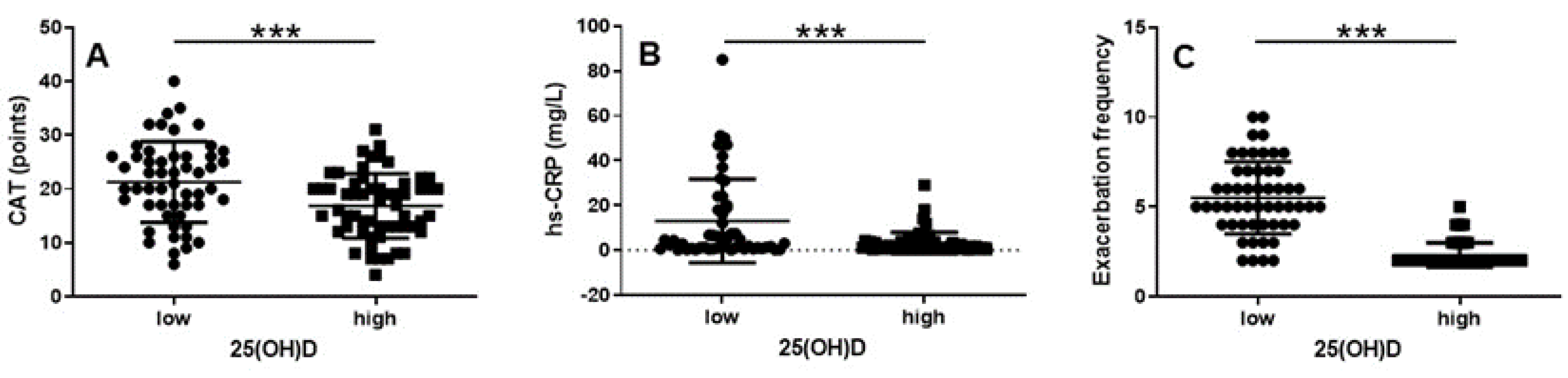

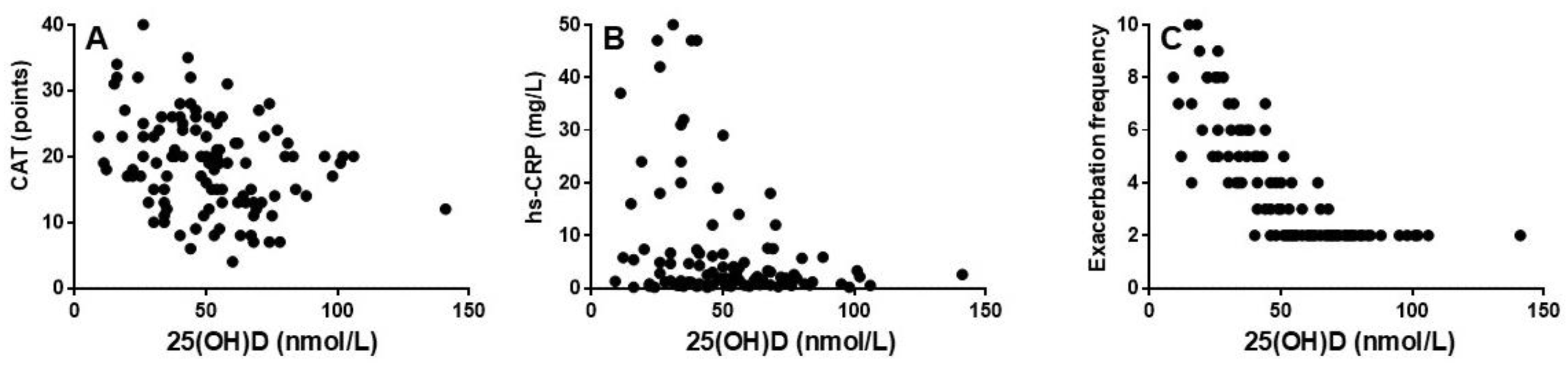

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with systemic inflammation and frequent exacerbations, thus, leading to disease progression and increased morbidity. Vitamin D deficiency has been suggested to be a contributing factor to COPD inflammation and exacerbations. Aim: To investigate the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels, systemic inflammation and exacerbation frequency among patients with COPD GOLD group E. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 111 patients with stable COPD. Patients were divided into two groups based on their serum 25(OH)D levels (<50 nmol/L vs. ≥50 nmol/L). Data on exacerbation frequency the past year, inflammatory markers, dynamic lung volumes and symptom burden were collected. Results: Patients with low serum 25(OH)D (<50 nmol/L) had significantly higher CAT-score and level of serum-high sensitivity (hs)-CRP and exhibited significantly more exacerbations compared to those with higher levels (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Furthermore, lower vitamin D levels were associated with higher CAT scores (r = -0.30; p < 0.01) and level of serum hs-CRP (r = -0.25; p < 0.01) and significantly more exacerbations (r = -0.74; p < 0.0001). Conclusion: Low vitamin D levels are significantly associated with greater symptom burden, elevated hs-CRP and increased exacerbation frequency in COPD patients group E. These findings suggest that monitoring and treating vitamin D deficiency may be beneficial in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

Data Handling and Data Protection

Patient and Public Involvement

Statistical Analysis

Ethics

Results

Characterization of the Study Population

Vitamin D Status Has a Significant Impact on CAT, hs-CRP and Exacerbation Frequency

Vitamin D Level Correlates Significantly with CAT, hs-CRP and Exacerbation Frequency

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Sharing Statement

Manuscript Originality

Disclosures

Acknowledgments

References

- Holick, MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson GC, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, Perera WR, Wedzicha JA. Exacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(5):446-52. Epub 2004 Dec 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Ge C, Zhang Z, Geng Z, Zhang L. Effects of physical activity and sedentary behavior on serum vitamin D in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2024;33(12):1329-1341. PMID: 38506415. [CrossRef]

- Janssens W, Bouillon R, Claes B, Carremans C, Lehouck A, Buysschaert I, Coolen J, Mathieu C, Decramer M, Lambrechts D. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in COPD and correlates with variants in the vitamin D-binding gene. Thorax. 2010;65(3):215-20. Epub 2009 Dec 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson LJ, Aanerud M, Hiemstra PS, Hardie JA, Bakke PS, Eagan TM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with low levels of vitamin D. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38934. Epub 2012 Jun 21. PMCID: PMC3380863. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Måhlin C, von Sydow H, Osmancevic A, Emtner M, Grönberg AM, Larsson S, Slinde F. Vitamin D status and dietary intake in a Swedish COPD population. Clin Respir J. 2014;8(1):24-32. Epub 2013 Jul 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentson M, Leanderson P, Jacobson P, Persson HL. The influence of disease severity and lifestyle factors on the peak annual 25(OH)D value of COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1389-1398. PMCID: PMC5927355. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens W, Lehouck A, Carremans C, Bouillon R, Mathieu C, Decramer M. Vitamin D beyond bones in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: time to act. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(8):630-6. Epub 2009 Jan 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herr C, Greulich T, Koczulla RA, Meyer S, Zakharkina T, Branscheidt M, Eschmann R, Bals R. The role of vitamin D in pulmonary disease: COPD, asthma, infection, and cancer. Respir Res. 2011;12(1):31. PMCID: PMC3071319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong RE, Zosky GR. Vitamin D deficiency and the lung: disease initiator or disease modifier? Nutrients. 2013;5(8):2880-900. PMCID: PMC3775233. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokturk N, Baha A, Oh YM, Young Ju J, Jones PW. Vitamin D deficiency: What does it mean for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? a compherensive review for pulmonologists. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(2):382-397. Epub 2017 Jan 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Rong Y, Zhang H, Zhan Z, Yuan L, Ning Y, Lin W. The correlation between a Th1/Th2 cytokines imbalance and vitamin D level in patients with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), based on screening results. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1032786. PMCID: PMC10063780d. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg I, Hanson C, Sayles H, Romberger D, Nelson A, Meza J, Miller B, Wouters EF, Macnee W, Rutten EP, Romme EA, Vestbo J, Edwards L, Rennard S. Vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, lung function and structure in COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1578-88. Epub 2013 Jul 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and pulmonary function in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Chest. 2005;128(6):3792-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkes RM, Ceppe AS, Doerschuk CM, Couper D, Hoffman EA, Comellas AP, Barr RG, Krishnan JA, Cooper C, Labaki WW, Ortega VE, Wells JM, Criner GJ, Woodruff PG, Bowler RP, Pirozzi CS, Hansel NN, Wise RA, Brown TT, Drummond MB; SPIROMICS Investigators. Associations Among 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels, Lung Function, and Exacerbation Outcomes in COPD: An Analysis of the SPIROMICS Cohort. Chest. 2020;157(4):856-865. Epub 2020 Jan 17. PMCID: PMC7118244. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh AJ, Moll M, Hayden LP, Bon J, Regan E, Hersh CP; COPDGene Investigators. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with respiratory symptoms and airway wall thickening in smokers with and without COPD: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):123. PMCID: PMC7199369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CY, Shin SH, Choi HS, Im Y, Kim BG, Song JY, Lee D, Park HY, Lim JH. Association Between Vitamin D Level and Respiratory Symptoms in Patients with Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:579-590. PMCID: PMC8937312. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson EL, Pourshahidi LK, Madigan SM, Baldrick FR, Kelly MG, Laird E, Healy M, Strain JJ, Mulhern MS. Vitamin D status is associated with muscle strength and quality of life in patients with COPD: a seasonal prospective observation study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2613-2622. PMCID: PMC6118240. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisaki KM, Niewoehner DE, Connett JE; COPD Clinical Research Network. Vitamin D levels and risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(3):286-90. Epub 2011 Nov 10. PMCID: PMC3297108. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinovschi A, Masoero M, Bellocchia M, Ciuffreda A, Solidoro P, Mattei A, Mercante L, Heffler E, Rolla G, Bucca C. Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalization in COPD patients. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):131. PMCID: PMC4269938. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekov E, Slavova Y, Tsakova A, Genova M, Kostadinov D, Minchev D, Marinova D, Tafradjiiska M. Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency in Hospitalized COPD Patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129080. PMCID: PMC4457885. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari R, Caram LMO, Tanni SE, Godoy I, Rupp de Paiva SA. The relationship between Vitamin D status and exacerbation in COPD patients- a literature review. Respir Med. 2018;139:34-38. Epub 2018 Apr 23. PMID: 29857999. [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, Mathyssen C, Rafiq R, de Jongh RT, Camargo CA, Griffiths CJ, Janssens W, Martineau AR. Vitamin D to prevent exacerbations of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Thorax. 2019;74(4):337-345. Epub 2019 Jan 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokesh KS, Chaya SK, Jayaraj BS, Praveena AS, Krishna M, Madhivanan P, Mahesh PA. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbation of COPD. Clin Respir J. 2021;15(4):389-399. Epub 2020 Dec 2. PMCID: PMC8043964. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li B, Liu M, Wang Y, Zhang H, Xuan L, Huang K, An Z. Association of Severe Vitamin D Deficiency with Hospitalization in the Previous Year in Hospitalized Exacerbated COPD Patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:1471-1478. PMCID: PMC11214566. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu L, Fei J, Tan ZX, Chen YH, Hu B, Xiang HX, Zhao H, Xu DX. Low Vitamin D Status Is Associated with Inflammation in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J Immunol. 2021;206(3):515-523. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMCID: PMC7812059. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorde I, Stegemann-Koniszewski S, Papra K, Föllner S, Lux A, Schreiber J, Lücke E. Association of serum vitamin D levels with disease severity, systemic inflammation, prior lung function loss and exacerbations in a cohort of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(6):3597-3609. PMCID: PMC8264670. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648-54. PMID: 19720809. [CrossRef]

- Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581-6. PMCID: PMC1745516. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenström H, Malmberg P, Agarwal K. Reference values for lung function tests in females. Regression equations with smoking variables. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1985;21(6):551-7. [PubMed]

- Hedenström H, Malmberg P, Fridriksson HV. Reference values for lung function tests in men: regression equations with smoking variables. Ups J Med Sci. 1986;91(3):299-310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minter M, Augustin H, van Odijk J, Vanfleteren LEGW. Gender Differences in Vitamin D Status and Determinants of Vitamin D Insufficiency in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Nutrients. 2023;15(2):426. PMC9863414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livsmedelsverket. LIVSFS 2018:5. Available online: https://kontrollwiki.livsmedelsverket.se/lagstiftning/402/livsfs-2018-5 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Abioye AI, Bromage S, Fawzi W. Effect of micronutrient supplements on influenza and other respiratory tract infections among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(1):e003176. PMCID: PMC7818810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiq R, Aleva FE, Schrumpf JA, Daniels JM, Bet PM, Boersma WG, Bresser P, Spanbroek M, Lips P, van den Broek TJ, Keijser BJF, van der Ven AJAM, Hiemstra PS, den Heijer M, de Jongh RT; PRECOVID-study group. Vitamin D supplementation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with low serum vitamin D: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;116(2):491-499. PMCID: PMC9348978. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei J, Liu L, Li JF, Zhou Q, Wei Y, Zhou TD, Fu L. Associations of Vitamin D With GPX4 and Iron Parameters in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: A Case-Control Study. Can Respir J. 2024;2024:4505905. PMCID: PMC11535414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sioutas A, Vainikka LK, Kentson M, Dam-Larsen S, Wennerström U, Jacobson P, Persson HL. Oxidant-induced autophagy and ferritin degradation contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition through lysosomal iron. J Inflamm Res. 2017;10:29-39. PMCID: PMC5378460. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentson M, Leanderson P, Jacobson P, Persson HL. Oxidant status, iron homeostasis, and carotenoid levels of COPD patients with advanced disease and LTOT. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1447221. PMCID: PMC5912708. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson HL, Sioutas A, Jacobson P, Vainikka LK. Human Lung Macrophages Challenged to Oxidants ex vivo: Lysosomal Membrane Sensitization is Associated with Inflammation and Chronic Airflow Limitation. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:925-932. PMCID: PMC7678820. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui Y, Du X, Li Y, Wang D, Lv Z, Yuan H, Chen Y, Liu J, Sun Y, Wang W. Imbalanced and unchecked: the role of metal dyshomeostasis in driving COPD progression, COPD: J COPD, 2024; 21: 1, 2322605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| COPD patients n = 111 |

Low (< 50 nmol/L) n = 53 |

High (≥ 50 nmol/L) n = 58 |

Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 70±10 (46-84) | 70±7 (52-86) | n.s. |

| Women, n (%) | 28 (53) | 34 (57) | n.s. |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26±7 (15-44) | 25±5 (15-40) | n.s. |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 12 (23) | 7 (12) | n.s. |

| Ex smokers, n (%) | 39 (74) | 49 (84) | n.s. |

| Never smokers, n (%) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | n.s. |

| mMRC (points) | 3(1) Md (IQR) | 3(1) Md (IQR) | n.s. |

| CCI, score 1, n (%) | 12 (23) | 18 (31) | n.s. |

| CCI, score 2, n (%) | 13 (25) | 7 (12) | n.s. |

| CCI, score 3, n (%) | 14 (26) | 14 (24) | n.s. |

| CCI, score ≥4, n (%) | 14 (26) | 19 (33) | n.s. |

| WBC | 9.8±4.2 (4.2-5.8) | 8.7±2.3 (4.2-15.4) | n.s. |

| SAT (%) | 92±6 (70-100) | 94±4 (82-100) | n.s. |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 42±17 (14-92) | 41±17 (13-82) | n.s. |

| GOLD stage 1, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | n.s. |

| GOLD stage 2, n (%) | 18 (34) | 17 (29) | n.s. |

| GOLD stage 3, n (%) | 14 (26) | 22 (38) | n.s. |

| GOLD stage 4, n (%) | 20 (38) | 18 (31) | n.s. |

| COPD medications | |||

| SABA; n (%) | 39 (74) | 48 (83) | n.s. |

| SAMA; n (%) | 15 (28) | 14 (24) | n.s. |

| LABA; n (%) | 51 (96) | 56 (97) | n.s. |

| LAMA; n (%) | 50 (94) | 53 (91) | n.s. |

| ICS; n (%) | 50 (94) | 54 (93) | n.s. |

| OCS; n (%) | 13 (25) | 13 (22) | n.s. |

| PD4I; n (%) | 7 (13) | 7 (12) | n.s. |

| LTOT; n (%) | 16 (30) | 12 (21) | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).