1. Introduction

With the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI), automated video creation has entered a new era [

1]. In February 2024, OpenAI released Sora, the first text-to-video generation model, marking a milestone in video production. Since then, the technology has advanced rapidly. In February 2025, the University of Hong Kong and TikTok launched Goku Plus for video advertising, and in May 2025, Google Veo 3 achieved synchronized audio-video generation. These large-scale video generation models represent a breakthrough for AI advertising, with vlogs—one of the most popular forms of social media content—most directly affected.

Vloggers share their daily lives, experiences, opinions, and expertise with audiences [

1]. With increasing commercialization, sponsored vlogs have become an important vehicle for brand marketing [

2]. Recently, AI has begun transforming vlog production, as video generation models reshape creation processes [

1], giving rise to AI-generated sponsored vlogs (AISVs). AI offers clear practical benefits to this medium: It shortens production cycles, reduces costs nearly 100-fold compared to traditional advertising [

3], frees marketing teams to focus on strategy, and decreases reliance on human resources, driving innovation in marketing and business models [

4].

However, the rapid spread of generative AI in marketing also presents challenges, especially for AISVs. First, AI-generated content (AIGC) can be misused for deepfakes and misinformation, undermining perceptions of content usefulness. Second, AI involvement may reduce source credibility [

5] and compromise consumer privacy through big data analysis [

6]. Finally, whether AISVs can effectively convey emotional value—crucial to young consumers’ decision-making [

7]—remains uncertain. These issues have led scholars and practitioners to call for closer scrutiny of AI’s ethical and societal risks [

5] and for the establishment of standards and guidelines to ensure its responsible use [

4].

With over 75% of consumers now using AI-enabled services or devices [

8], AI-driven transformation has created fundamental differentiation among consumer groups, just as the internet era distinguished digital immigrants from digital natives [

9]. This study introduces the conceptual distinction between “AI immigrants” and “AI natives.” AI natives are consumers who have grown up in AI-saturated environments, whose early consumption behaviors have been shaped by AI and who regard it as integral to decision-making and value perception. Contrarily, AI immigrants formed consumption habits before the rise of AI and later adapted to its applications. In social e-commerce, this distribution of AI literacy presents new challenges for existing marketing regulations.

Traditional regulations assume consumer information asymmetry, with consumers typically at a disadvantage [

10] (pp. 1–10). In AISV contexts, however, high-literacy consumers—both immigrants and natives—can effectively identify and evaluate AIGC [

11], while low-literacy consumers remain disadvantaged. This divergence makes uniform protection standards inadequate; restrictions may overregulate AI natives while failing to safeguard traditional consumers. According to Coffin’s (2022) ontological, technical, and ethical (O-T-E) framework, resolving this dilemma requires clarifying AISVs’ characteristics and consumers’ differentiated responses before establishing robust ethical regulations. Despite this need, research on AISV consumer responses remains structurally imbalanced. Studies focus heavily on AI’s technical aspects [

12,

13], while consumer perspectives are underexplored [

14]. Particularly, attitudes toward AI-generated advertising [

15] are insufficiently studied, leaving gaps in understanding AI’s influence on marketing [

1]. Current AI literacy research emphasizes conceptualization, assessment, and cultivation, with most studies limited to students or professionals in specialized fields (e.g., doctors, developers, teachers) [

11]. Applied research on consumer AI literacy remains scarce.

Crucially, preliminary evidence suggests that differences in AI literacy [

16], leading to an AI divide [

17], may significantly shape AI advertising effectiveness. Familiarity with AI alters consumer response patterns [

18], with varying digital literacy levels producing distinct attitudes toward AI marketing [

19]. Yet these fragmented findings have not been integrated into a systematic framework. Particularly, theoretical models lack explanations of how AI literacy influences cognitive assessment, emotional response, and source evaluation, as well as how these effects vary across product types.

1.1. Research Objectives and Questions

This study primarily aims to develop and empirically test an integrated theoretical framework explaining how AI literacy shapes consumer responses to AISVs and subsequent purchase intentions, while also examining how these relationships vary across product contexts.

To address this problem, this study investigates three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How does consumer AI literacy influence perceptions and information adoption from AISVs?

This question aligns with the technology problem dimension of the OTE framework, with emphasis on differential consumer response patterns. Prior studies recognize the need to examine how AI literacy shapes cognitive responses [

20] and acceptance of AI-driven advertising [

21]. Nonetheless, no framework systematically integrates AI literacy with AISV response mechanisms across cognition, emotion, and source evaluation, highlighting a notable theoretical gap in AI marketing research.

RQ2: What are the direct and indirect effects of AI literacy on purchase intention in AISV contexts?

This question extends inquiry from cognitive influence to purchase decision formation. While existing research addresses AI marketing applications, it has not fully explained their long-term behavioral impact [

22]. A systematic understanding of how AI literacy shapes purchase intention through multiple mediating pathways is lacking. This study evaluates these pathways, constructing an integrated framework that traces the influence of technological literacy through purchase decisions, thereby offering guidance for multi-path marketing strategies and advancing understanding of decision processes in AI video marketing.

RQ3: How do these relationships differ across product types (tangible products versus experiential services)?

Product type is a critical but underexplored variable in AISV research. Kumar and Singh’s (2024) classification of automated vlog content (actor-present versus actorless) provides a useful lens. Evidence suggests product type affects consumer preferences; consumers of search products prefer collaborative filtering recommendations, while experiential product consumers favor content-based filtering [

23]. Similarly, virtual influencers are more persuasive for technological than for non-technological products [

24]. Yet no analytical framework integrates AI video generation, product type, and consumer AI literacy. This study addresses this gap by comparing actorless tangible product-oriented AISVs (e.g., clothing, food, household items) with avatar-mediated, experiential service-oriented AISVs (e.g., dance, sports, fitness). It explores structural differences in AI literacy pathways across product categories and provides a theoretical basis for targeted AISV marketing strategies.

In summary, this study is among the first empirical investigations to systematically examine the mechanisms by which consumer AI literacy influences AISV responses and how these mechanisms vary by product type. It proposes the AI Literacy Perception-Decision Model (ALPDM), integrating multi-dimensional theoretical perspectives to reveal the pathways through which technological literacy shapes consumer behavior. We believe the findings advance academic understanding of the antecedents of AISV effectiveness and provide theoretical support for practitioners seeking to optimize AISV strategies and design differentiated implementation plans.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of AISVs

Defining AISVs requires an understanding of their fundamental components. Sponsored vlogs integrate advertising into video blogs [

25], while “AI-generated” derives from generative AI, which produces realistic outputs using methods such as Generative Adversarial Networks and is widely applied in image and video synthesis [

4]. Advanced models such as Video-GPT generate video content from text descriptions, creating new opportunities for vlog production [

26]. Accordingly, AISVs are defined as videos created by AI algorithms according to vlogger instructions, using sponsor-provided product information and materials, and published on social media in exchange for sponsorship compensation. This definition highlights three core elements: the AI-driven creation process, vlogger’s guiding role, and commercial sponsorship nature. According to Kumar and Singh’s (2024) generative technology classification, AISVs can be divided into actorless (static or dynamic displays) and actor-present (partially or fully dynamic) types, reflecting their technological diversity and differentiated requirements. As a form of AI advertising, AISVs also inherit four key characteristics identified by Wu et al. (2021): data-driven, tool-enabled, process-synchronized, and efficiently executed. These features provide distinct advantages—precise audience targeting, creative automation, enhanced efficiency, and real-time content optimization—supporting their emergence as a powerful marketing tool.

2.2. AI Literacy

AI literacy is emerging as a key capability in the digital economy. Long and Magerko (2020) describe it as “a set of competencies required to evaluate, interact with, and use AI systems,” while Almatrafi et al. (2024) expand this into six dimensions: Recognize, Know and Understand, Use and Apply, Evaluate, Create, and Navigate Ethically. This framework provides the theoretical basis for examining how consumer AI literacy shapes responses to AISVs.

As AI penetrates marketing, literacy differences have become a critical factor in consumer information processing and decision-making. Consumers lacking digital knowledge not only face barriers to online advertising services but may also overlook concerns about algorithmic predictions [

5]. Such disparities influence how consumers perceive, interpret, and adopt AISV content. Recent scholarship calls for extending digital literacy to include AI cognition [

21]. While prior research highlights the importance of AI literacy for marketers [

27] and corporate executives [

28], studies focusing on its impact on consumer responses to AI advertising remain limited. This gap is particularly significant as AI literacy diffusion coincides with the rapid commercialization of AIGC applications.

Consumer expertise levels may further shape perceptual frameworks for AISVs. Greiner and Lemoine (2025) find that non-expert users display polarized trust in AI systems, whereas Ratta et al. (2024) show that professionals often regard AI advertising as more effective than human-created content in driving engagement and purchases. These findings raise a central question: How do consumer AI literacy levels influence perceptions, information adoption, and purchase intention in AISV contexts? This study addresses this gap by systematically analyzing the pathways through which AI literacy, as a key independent variable, affects consumer decision-making.

2.3. Theory and Models

This research integrates the Value-Based Adoption Model (VAM) and Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) to construct a framework for analyzing consumer responses to AISV marketing. As advertising operates as a brand-centered persuasive communication tool [

5], AISVs function both as applications of AI technology and as vehicles for advertising delivery, necessitating multi-dimensional theoretical perspectives. VAM provides the core foundation by positioning perceived value—rather than utility alone—at the center of adoption decisions, incorporating both cognitive and affective dimensions [

29]. Within this model, consumers assess AISVs by weighing functional value against experiential enjoyment. VAM also explains how technological complexity lowers perceived value by increasing cognitive demands, offering insight into how AI literacy shapes evaluations. ELM complements VAM by addressing persuasion processes through dual-path information processing [

30]. The two models align naturally; content usefulness in VAM corresponds to information quality assessment in ELM’s central route, while the peripheral route highlights the importance of source characteristics (e.g., vlogger credibility) when cognitive resources are constrained. In AISV contexts, this integration explains why consumers with different AI literacy levels rely on distinct evaluative pathways.

Building on this integration, this study proposes the ALPDM, which identifies key mediating pathways across three dimensions: emotional, cognitive, and trust. ALPDM fills a critical gap by linking consumer AI literacy with multi-dimensional information processing, providing a systematic framework to explain the antecedent conditions of AISV marketing effectiveness.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.4.1. Emotional Pathway of AI Literacy: Shaping Emotional Value and its Subsequent Effects

Emotional value, a key dimension of consumer perceived value, refers to the pleasure provided by a product or service [

31] and the utility derived from the affective states it generates [

32].

Consumer AI literacy directly shapes the ability to extract emotional value from AISVs, and high AI literacy enhances technological pleasure [

33]. In AISV contexts, high-literacy consumers better understand technological features, perceive personalization more fully, and derive greater satisfaction from AI-driven recommendations and customized content [

34]. They also respond more strongly to AI-induced novelty [

21], and their broader hedonic motivations and technological experience further enrich emotional responses [

12].

Although vlog advertising is often function-oriented, emotional value significantly influences consumer decision-making, even for durable goods [

32]. Positive evaluations of AI performance increase user emotional responses, which in turn strengthen acceptance [

12]. Accordingly, we propose:

H1: Consumer AI literacy directly influences AISVs’ emotional value.

Once emotional value is established, it affects behavioral outcomes. Entertainment satisfaction among digital natives enhances attitude formation [

9], and in AISV contexts, pleasurable experiences extend viewing, deepen engagement, and foster positive information processing. Satisfied consumers are more likely to share and rely on AISV content [

16]. Thus, we propose:

H2: AISVs’ emotional value directly influences consumer adoption of AISVs.

Emotional value also drives purchase intention. Positive emotional experiences transfer to sponsored products through associative learning, strengthening purchase willingness and word-of-mouth [

31]. Consumers with positive emotions show stronger AI acceptance [

12]. Given that AI interactions often lag behind human interactions in generating emotional connection [

35], successful emotional value creation in AISVs becomes critical. Therefore, we propose:

H3: AISVs’ emotional value directly influences purchase intention.

2.4.2. Cognitive Pathway of AI Literacy: Assessment of Information Usefulness and its Effects

Utilitarian value is another core dimension in consumer evaluation of AISVs. Lim et al. (2024) define usefulness as the value of product information dissemination in online advertising. In AISV contexts, utility reflects the extent to which vlog product information assists consumer decision-making. Consumer AI literacy directly shapes perceptions of information usefulness. Knowledgeable users form more reasonable expectations, and alignment between expectations and technological capabilities strengthens satisfaction and perceived usefulness [

33]. High-literacy consumers better understand AISV content generation mechanisms, set realistic quality standards, and evaluate utilitarian value more accurately. Wu et al. (2024) note that “machine heuristics” lead people to attribute objectivity and accuracy to AI, particularly in processing quantifiable tasks. High-literacy consumers are more adept at recognizing AI’s boundaries, judging content usefulness rationally, and making trust decisions accordingly. When AISVs deliver accurate, relevant, and high-quality information, they create positive user experiences that encourage continued engagement [

34]. High-literacy consumers are especially capable of filtering irrelevant content, thereby enhancing perceptions of usefulness. We thus propose:

H4: Consumer AI literacy directly influences perceived usefulness of AISVs.

Perceived usefulness then drives information adoption. Lim et al. (2024) show that advertising usefulness positively affects attitudes and improves purchase decision efficiency. When consumers view AISVs as providing valuable information, they are more likely to adopt and apply it in decision-making. Argan et al. (2023) further demonstrate that interactive behavior toward advertisements depends on value assessment; when information matches needs, perceived usefulness rises, encouraging action. Chen et al. (2024) confirm that source credibility, content quality, and need matching collectively determine persuasive effectiveness.

Moreover, emphasizing product functional attributes reduces resistance to AI advertising by leveraging the “machine effect,” wherein consumers perceive AI as more capable than humans in functional and objective assessments [

36]. These findings underscore the central role of information usefulness: Consumers must first perceive AISV content as useful before adopting it to guide decisions. Therefore, we propose:

H5: AISVs’ usefulness directly influences consumer adoption of AISVs.

2.4.3. Trust Pathway of AI Literacy: Evaluating Source Credibility and its Consequences

Source credibility is a central factor shaping consumer information processing and decision-making, classically defined as “positive characteristics of a communicator that influence the receiver’s acceptance of information,” typically measured through expertise and trustworthiness [

37] (pp. 20–21). In online advertising, credibility reflects both the objective and subjective trustworthiness of information or entities [

9]. With the rise of AISVs, vloggers simultaneously act as content creators and product sellers, requiring credibility assessment mechanisms to adapt to AI-driven contexts.

In AISV contexts, evaluating vlogger credibility requires consumers to possess specific AI-related cognitive abilities. AI literacy equips consumers with three core skills: technological discernment to distinguish between high- and low-quality AIGC, understanding AI’s boundaries to judge appropriate application of the technology, and professional judgment to evaluate vloggers’ proficiency in integrating AI with product information [

11]. These abilities form the cognitive foundation for assessing vlogger credibility and directly influence trust formation in their dual roles.

Prior research has established that information credibility significantly shapes consumers’ attitudes toward AR advertisements, which in turn influence purchase intentions [

38]. Building on this, digital natives, who are adept at navigating AI-driven systems, exemplify the importance of AI literacy as an antecedent of credibility assessment in AISV contexts [

19]. High-literacy consumers can thus make more accurate evaluations of vloggers’ expertise and trustworthiness. Therefore, we propose:

H6: Consumer AI literacy directly influences perceived vlogger credibility.

Once credibility is established, it strongly shapes adoption behavior. Research shows that perceptions of advertising credibility affect information processing and decision-making [

9]. When consumers view information sources as credible, they are more likely to trust recommendations and form purchase intentions [

39]. In AIGC contexts, credibility significantly influences viewing behavior and purchase decisions [

40]. Source credibility affects adoption through two pathways: enhancing persuasiveness, which increases receptivity to claims, and reducing uncertainty, which lowers decision risk [

41]. In AISVs, where AI application itself may raise trust concerns, credible vloggers can mitigate skepticism. When vloggers are considered both technically proficient in AI and trustworthy, consumers are more willing to adopt their recommendations [

42]. Therefore, we propose:

H7: Vlogger credibility directly influences consumer adoption of AISVs.

In AISV marketing environments, consumer AI literacy serves as a key cognitive resource, directly shaping information processing and purchase decisions. Digital natives’ attitudes toward online advertising positively influence purchase intention [

9], and a similar mechanism operates in AI-driven contexts. AI-driven marketing affects consumer behavior, while AI literacy determines how consumers interpret and respond to content. Higher digital literacy enables consumers to rationally evaluate AI marketing strategies, recognize their value and limitations, and make more informed decisions [

19]. High-literacy consumers can accurately assess AISV information quality and usefulness, increasing their willingness to adopt content. AI literacy also strengthens purchase decision-making; high-literacy consumers move beyond superficial appeal, analyze the substantive value of AI-enhanced content, and form stronger purchase intentions [

19]. Therefore, we propose:

H8: Consumer AI literacy directly influences information adoption from AISVs.

H9: Consumer AI literacy directly influences purchase intention.

Information adoption, as a core cognitive process, directly affects final purchase decisions. In AISV contexts, it reflects the full chain from content acceptance to behavioral intention. When consumers recognize AISV content as valuable and credible, they form positive cognitive attitudes that provide a basis for purchase decisions [

9]. Evidence indicates that adopted AI-enhanced marketing information transforms into a cognitive foundation for consumer behavior [

19]. Information adoption thus signals that consumers have overcome cognitive barriers and established trust in the content, supporting subsequent purchase actions. Therefore, we propose:

H10: Information adoption from AISVs directly influences purchase intention.

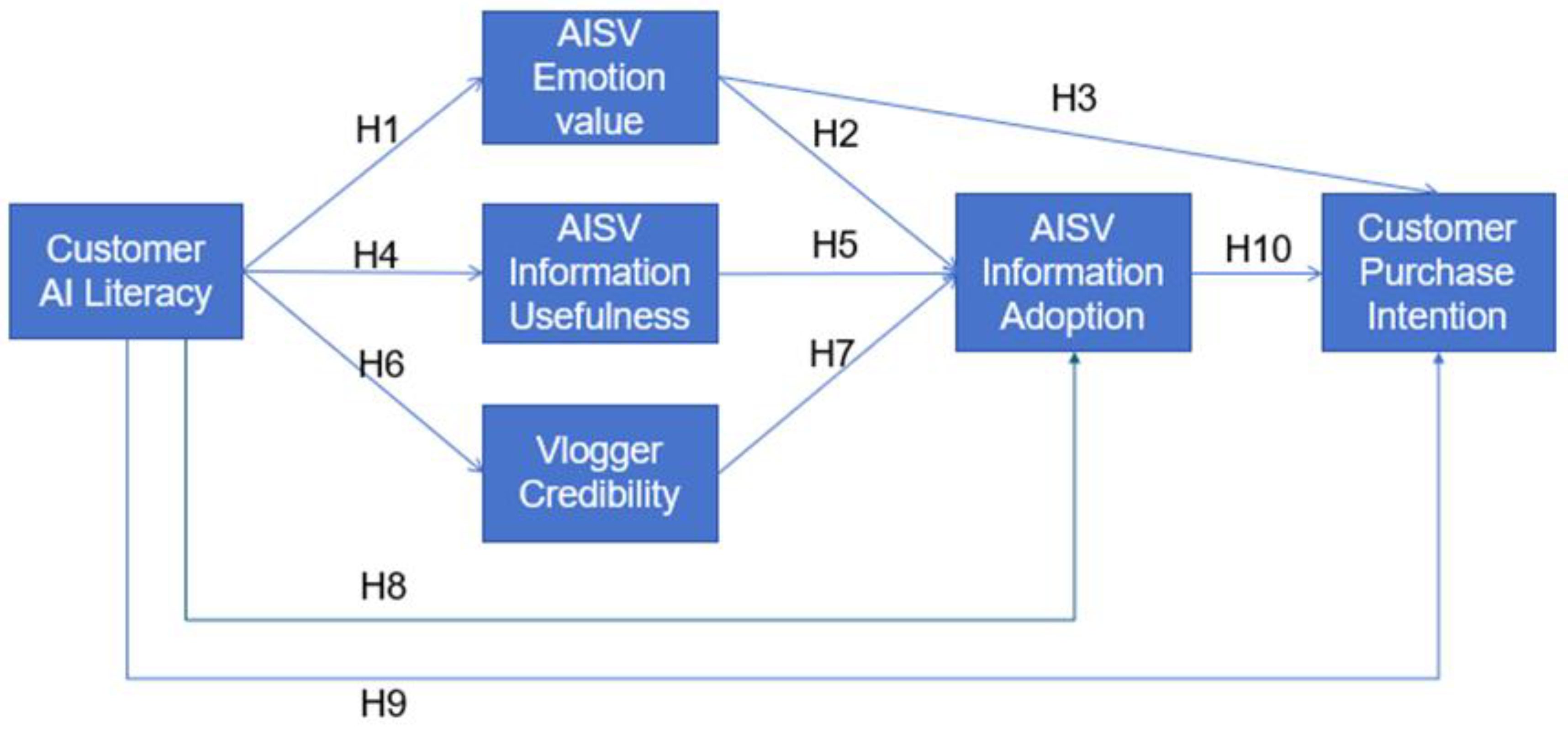

Figure 1.

AI Literacy Perception-Decision Model.

Figure 1.

AI Literacy Perception-Decision Model.

Table 1.

Operational definitions.

Table 1.

Operational definitions.

| Constructs |

Operational definitions |

References |

| Consumer AI literacy |

The degree to which consumers possess the knowledge, skills, and critical understanding necessary to recognize, evaluate, and engage with AIGC, particularly AISVs. |

[43] |

| AISV emotional value |

The affective utility consumers experience during AISV viewing, characterized by positive emotional responses. |

[31,32] |

| AISV information usefulness |

The extent to which product or service-related information in AISVs enhances consumers’ purchase decisions. |

[9] |

| Source credibility |

The perceived ability and motivation of the vlogger in an AISV to produce accurate and truthful information. |

[44] |

| AISV information adoption |

The extent to which consumers accept and utilize the information from AISVs to support their purchase decisions. |

[45] |

| Purchase intention |

Consumers’ willingness to purchase products or services after watching AISVs. |

[46] |

3. Methodology

This study used a cross-sectional survey targeting Chinese social media users who watch AISVs and make purchases via these platforms. An anonymous online questionnaire was distributed via WeChat using convenience sampling. A minimum sample size of 385 was calculated based on a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error (Z=1.96). The study protocol was approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Ethics Committee (Reference No. JEP-2024-382). Informed consent was obtained electronically from all respondents through acknowledgment of a consent statement presented on the first page of the questionnaire.

The study’s effective sample comprised 37.53% male participants and 62.47% female participants, broadly consistent with TikTok e-commerce users (66% female) [

47]. Most respondents were aged 18–39 (87.89%), with 18–24-year-olds accounting for 44.79%, suggesting that the survey primarily captured the perspectives of younger individuals. Education was predominantly undergraduate/bachelor’s level (73.61%), with 81.36% having college education or above. Occupations were mainly students (36.80%) and corporate employees (26.15%), and 75.79% of respondents watched short videos at least once daily. These characteristics align with the core target audience for AI-generated short videos—young, highly educated, digitally engaged users—supporting the sample’s representativeness and the validity of the findings [

17].

3.1. Research Instruments, Measures, and Variable Measurement

AISVs are a novel content format in which creators use AI tools to produce product-focused videos, with consumers primarily acting as passive viewers rather than active technology evaluators. Building on Carolus et al.’s (2023) AI literacy framework, we adapted the construct for this context by retaining three dimensions—Use and Apply AI, Know and Understand AI, and Detect AI—while excluding AI Ethics. This decision followed a contextual relevance analysis, as ethics items mainly address macro-level societal issues and active technology evaluation, which are less applicable to passive AISV consumption. The adapted framework aligns with scale adaptation principles that recommend contextual refinement while preserving theoretical integrity, enhancing construct validity [

48] (pp. 285–290).

Given the emerging nature of AISVs and the lack of mature measurement tools, scale items were selected and adapted from the literature (

Table 2) to match the research variables. Participants rated items on a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree). Content validity was confirmed through expert review, and a pilot test (n=128) demonstrated reliability (Cronbach’s α [CA] > 0.8647) and validity (average variance extracted [AVE] > 0.603; composite reliability [CR] and CA > 0.7), meeting widely accepted academic standards and providing a robust foundation for formal testing.

The formal survey conducted in May 2025 yielded 413 valid responses from 666 questionnaires (62.0% response rate) after excluding incomplete responses, underage participants, and those unexposed to either type of AISV. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation was used to examine how AI literacy affects information adoption and purchase intention. Analyses were performed across four sample groups: tangible products (n=369), experiential services (n=333), tangible products AND experiential services (n=289), and the tangible products OR experiential services (N=413). Measurement models were evaluated for reliability, validity, and fit indices. Multi-group comparisons tested direct and indirect effects while controlling for measurement error, revealing differential mechanisms of AI literacy across product contexts.

4. Results

Descriptive statistics (N=413) showed means ranging from 3.339 to 3.690 (SD=0.990–1.210). All variables exhibited acceptable normality, with skewness between -0.581 and -0.191 and kurtosis between 2.182 and 2.900, within recommended thresholds (|3.0| and |10.0|, respectively) (Hair et al., 2009). The measurement model demonstrated strong reliability, with CA and CR values of 0.893–0.923 (>0.7). KaiserMeyerOlkin measures (0.893–0.923) indicated excellent sampling adequacy. Convergent validity was supported by high factor loadings (0.722–0.874) and AVE values (0.603–0.741). Discriminant validity was confirmed as the square root of AVE exceeded inter-construct correlations, confirming the measurement model’s suitability for hypothesis testing.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity statistics.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity statistics.

| Constructs |

Cronbach’s α |

KMO |

CR |

Factor loading |

AVE |

| AIL |

0.9172 |

0.916 |

0.901 |

0.722-0.817 |

0.603 |

| EM |

0.9229 |

0.893 |

0.923 |

0.818-0.858 |

0.707 |

| SC |

0.9194 |

0.842 |

0.920 |

0.832-0.874 |

0.741 |

| IU |

0.9112 |

0.848 |

0.911 |

0.840-0.855 |

0.720 |

| IA |

0.8933 |

0.836 |

0.893 |

0.793-0.842 |

0.676 |

| PI |

0.9134 |

0.841 |

0.913 |

0.832-0.863 |

0.723 |

Before hypothesis testing, the fit of the measurement models was evaluated for each group. As

Table 4 shows, all four models demonstrated acceptable fit indices. Although chi-square tests were significant (χ²_ms (314)=959.511–1099.267, p<0.001), this is common in large samples. Root mean square error of approximation values ranged from 0.078 to 0.084, close to recommended thresholds; comparative fit index (0.899–0.928) and TuckerLewis Index (0.887–0.919) approached or exceeded 0.90; standardized root mean square residual values were below 0.08 (0.042–0.051); and CD values remained high (0.962–0.964), collectively indicating good model fit and explanatory power [

53]. Multicollinearity diagnostics showed all 27 measurement items had acceptable variance inflation factors: 11 below 3, 16 between 3 and 5, and the highest at 4.24 (SC4), confirming that multicollinearity would not compromise model estimation.

Table 5 presents the standardized coefficients and significance levels for direct paths. AI literacy significantly and positively influences emotional value across all groups (βT=0.900, βE=0.910, βT OR E=0.901, βT AND E=0.908; p<0.001), supporting H1. Emotional value, in turn, positively affects information adoption (βT=0.330, βE=0.314, βT OR E=0.298, βT AND E=0.369; p<0.001), confirming H2. AI literacy also significantly increases information usefulness (βT=0.936, βE=0.934, βT OR E=0.937, βT AND E=0.931; p<0.001) and source credibility (βT=0.890, βE=0.883, βT OR E=0.888, βT AND E=0.883; p<0.001), supporting H4 and H6. Information usefulness (βT=0.544, βE=0.618, βT OR E=0.560, βT AND E=0.614; p<0.001) and source credibility (βT=0.308, βE=0.269, βT OR E=0.279, βT AND E=0.313; p<0.001) positively influence information adoption, validating H5 and H7. The direct effect of AI literacy on information adoption is non-significant (βT=-0.128, βE=-0.152, βT OR E=-0.086, βT AND E=-0.240; p>0.05), failing to support H8. Information adoption strongly predicts purchase intention (βT=0.990, βE=0.813, βT OR E=0.912, βT AND E=0.895; p<0.001), confirming H10, while emotional value’s direct effect on purchase intention is non-significant (H3 is not supported). AI literacy’s direct effect on purchase intention is significant only for experiential services (β=0.285, p=0.035), partially supporting H9.

Mediation effects were tested using the Delta method, Sobel test, and Monte Carlo simulation (

Table 6). All three paths from AI literacy to information adoption through emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility are fully mediated (p<0.001), while the direct effect of AI literacy on information adoption remains non-significant (p>0.05); this indicates that AI literacy promotes information adoption primarily by enhancing these value perceptions. The AI literacy to purchase intention through information adoption path is non-significant across all groups (p>0.05), consistent with the significant direct effect of AI literacy on purchase intention in the experiential service group. The emotional value to purchase intention through information adoption path shows full mediation (p<0.001), highlighting information adoption as a crucial mediator between emotional value and purchase intention.

Multi-group SEM revealed that AI literacy influences information adoption through three parallel full mediation paths (emotional value, information usefulness, source credibility) with consistent direct effects across all groups (β=0.88–0.94, p<0.001). The strongest mediating effect is via information usefulness (β=0.509–0.577), followed by emotional value (β=0.268–0.335) and source credibility (β=0.237–0.276), a ranking consistent across product types. The direct effect of AI literacy on purchase intention is significant only for experiential services (β=0.285, p<0.05). The information adoption to purchase intention path is significantly stronger for tangible products (β=0.990, p<0.001) than experiential services (β=0.813, p<0.001), with a difference of 0.177, indicating a stronger link between information adoption and purchase intention in the tangible product group.

5. Discussion

5.1. How AI Literacy Shapes Consumer Perception and Information Adoption from AISVs (RQ1)

This study’s findings suggest that consumer AI literacy does not directly affect AISV information adoption (H8 not supported) but operates through three parallel mediating paths: information usefulness (β=0.509–0.577), emotional value (β=0.298–0.369), and source credibility (β=0.201–0.267). This challenges the assumption that “understanding AI technology necessarily leads to AI technology acceptance” [

13] and highlights consumers’ prioritization when evaluating AISVs: utilitarian value outweighs emotional and trust factors. These results establish value perceptions as key mediators between technological cognition and behavioral adoption.

The emotional value pathway confirms that AI literacy enhances AISV information adoption by increasing emotional value perception (H1, H2 supported). This effect follows a two-stage cognitiveemotional transformation: high-literacy consumers first reduce cognitive load and AI anxiety [

13], then convert this cognitive advantage into an emotional appreciation of AISV content. This finding addresses Coffin’s (2022) question of whether consumers will exchange choice autonomy for AI convenience, showing that AI evaluation depends not only on technology itself but also on consumers’ AI literacy. By validating AI literacy as a key antecedent of emotional value perception, this study clarifies the formation of users’ emotional responses to AISVs, complementing prior research that reported divergent reactions to AIGC without explaining their origins [

16]; [

54].

However, the hypothesis that emotional value directly impacts purchase intention (H3) is not supported, revealing a theoretical nuance. While prior studies suggest that emotional engagement from online advertisements can positively influence attitudes and purchase intention [

3], our findings show that emotional value primarily promotes information adoption. Only through this mediating pathway does AIGC influence final purchase decisions, highlighting its role in driving initial engagement and information processing rather than directly affecting purchase behavior.

This study identifies the information usefulness pathway (H4, H5) as having the strongest mediating effect, confirming that consumer AI literacy enhances AISV information adoption primarily by increasing perceived usefulness. This aligns with prior research emphasizing perceived usefulness as a key determinant in technology acceptance [

13]. AI advertising technologies are highly efficient—capable of generating 20,000–30,000 copies daily, 50–60 times the output of humans—while leveraging data-driven approaches, tool support, and parallel processing [

54]. Our results show a significant positive correlation between AI literacy and perceived AISV usefulness, which can be explained through the “machine heuristic”: Consumers perceive AI as more accurate in objective, quantifiable tasks [

21]. In utilitarian consumption contexts, highly AI-literate consumers more readily apply this heuristic, attributing greater functional value to AISV content [

36]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to empirically link AI literacy, the machine heuristic, and perceived usefulness, explaining how transparency disclosure enhances marketing effectiveness: AI literacy activates the machine heuristic, which increases perceived usefulness and, in turn, promotes information adoption, providing a theoretical basis for AI marketing design.

The results also support H6 and H7, confirming that source credibility fully mediates the effect of AI literacy on AISV information adoption. Highly AI-literate consumers adopt AISV content primarily through positive evaluations of vlogger credibility, consistent with prior findings on the importance of source credibility in consumer decisions [

9]; [

31]. Similar to the usefulness pathway, the source credibility pathway reflects a machine heuristic effect: Contrary to assumptions that AI involvement undermines credibility [

5], higher AI literacy corresponds with increased trust in AI-assisted vloggers. Previous work has suggested that AI transparency disclosure enhances perceived objectivity in advertising [

14] and signals brand openness and value alignment [

15]; [

42]. Our findings extend this framework to content creator evaluation, showing that technological competence reshapes consumer trust formation in AI-generated marketing.

In traditional ELM theory, source credibility functions as a peripheral cue used by consumers in low-cognitive-investment states [

30]. In the AISV context, however, highly AI-literate consumers evaluate source credibility more deeply. Their understanding of AI allows them to interpret vloggers’ transparent and skillful use of AI as evidence of honesty and professional competence. This cognitive processing elevates source credibility from a peripheral cue to a factor requiring thoughtful analysis, challenging and extending traditional persuasion frameworks in the AI content era. This study shows that highly AI-literate consumers assess creators’ honesty and professional capabilities by evaluating technological transparency in AISVs, establishing a new paradigm of credibility assessment based on technological literacy.

Overall, this study identifies three parallel pathways through which AI literacy influences AISV information adoption: emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility. AI literacy serves as a cognitive advantage that enhances emotional appreciation for AISV content, promoting adoption. The “machine heuristic” pathway—where high AI literacy increases perceived information usefulness—exerts the strongest effect, while the source credibility pathway demonstrates that highly AI-literate consumers develop trust in algorithmic integrity through perceptions of technological transparency. These findings clarify how AISV marketing content gains consumer acceptance. However, the conversion from information adoption to actual purchase decisions remains to be examined.

5.2. Direct and Indirect Effects of AI Literacy on Purchase Intention (RQ2)

This study identifies multiple mediating mechanisms through which AI literacy influences purchase intention, based on SEM analysis. The results confirm that AISV information adoption significantly increases purchase intention (H10 supported), reinforcing its role as a key antecedent of consumer behavioral intentions [

55]. AI literacy enhances purchase intention by shaping consumers’ three-dimensional value perceptions of AISV—emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility—which in turn promote information adoption; this supports the view that digital literacy strengthens consumers’ critical understanding of marketing strategies [

19].

The analysis shows that emotional value affects purchase intention only indirectly through information adoption, revealing an “emotionalpurchase conversion mechanism”: While emotional value stimulates initial interest, visual expressiveness enhances emotional experience but does not necessarily strengthen consumers’ cognitive assessment of message reliability [

38], and thus cannot directly drive purchase decisions. Consumers must assess content utility and relevance via information adoption to form purchase intentions. Higher AI literacy reduces cognitive load when processing AISV content [

56], allowing consumers to perceive value more clearly and evaluate information more efficiently, facilitating the conversion from emotional engagement to purchase decisions.

Regarding AI literacy’s direct effect on purchase intention (H9), significant differences emerge by product type: AI literacy directly influences purchase intention for experiential services but not for functional products. This indicates that the mechanisms linking AI literacy to purchase behavior vary across product categories, forming the basis for further investigation.

5.3. Relationship Patterns Under Product Type Differences (RQ3)

Multi-group SEM revealed that AI literacy consistently influences the three mediating variables—emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility—across all product types. AI literacy acts as a metacognitive ability that enhances consumers’ cognitive assessment of AIGC, independent of product category. However, significant differences emerge in the direct path from AI literacy to purchase intention: The path is significant for experiential services (β=0.285, p=0.035) but non-significant for tangible products. This indicates that AI literacy’s effect on purchase decisions varies by product type, warranting theoretical exploration of the underlying cognitive mechanisms.

Grounded cognition theory and dual mechanisms of technological transparency help explain this phenomenon. Grounded cognition theory suggests that cognitive processes are rooted in interactions between the body and environment [

57], with sensorimotor systems and mirror neurons engaged during concept understanding and action observation [

58]. Experiential AISVs (e.g., fitness, dance, sports guidance) rely on bodily perceptual engagement. Highly AI-literate consumers, understanding AI generation mechanisms, can overcome technological barriers, accurately interpret visual-action simulations, map AISV content to potential bodily experiences, and form direct purchase intentions.

Moreover, AI marketing faces challenges owing to algorithmic opacity, with low explainability reducing adoption willingness [

59] and transparency deficits contributing to consumer resistance [

42]. For highly AI-literate consumers, this opacity transforms into a cognitive advantage. Explainable AI systems enhance comprehensibility, allowing users to understand model operations and content generation [

59]. Combining this transparency with existing technical knowledge, highly AI-literate consumers shift focus from questioning AI content authenticity to evaluating how effectively AISVs convey experiential attributes. This cognitive advantage, coupled with neural simulation capabilities from grounded cognition, explains why AI literacy can bypass traditional information adoption pathways and directly influence purchase intention in experiential service contexts.

Compared to experiential services, actorless tangible product-oriented AISVs primarily emphasize functional specifications and physical attributes, engaging bodily perception simulation to a lesser extent. In this context, even high AI literacy provides limited advantage; consumers struggle to map AISV content to bodily experiences and cannot form direct purchase intentions. The finding also shows that AI literacy has a non-significant effect on information adoption for tangible products, confirming its limited role in this domain. These findings define the boundary conditions of AI literacy’s influence on purchase decisions: Only in experiential service contexts can AI literacy bypass information adoption to directly affect purchase intention.

This result challenges two existing perspectives. First, contrary to Gursoy et al. (2019), who concluded that AI anthropomorphic features do not enhance task performance or service quality, we find that highly AI-literate consumers shift their evaluation from anthropomorphism to functionality, effectively overcoming the “uncanny valley” [

60]. This cognitive shift reflects the evolution of technology acceptance models, especially in experiential service contexts. Second, we question Wu et al.’s (2021) claim that AI content creation is most effective for rational appeals and utilitarian products. With AI literacy accounted for, high-literacy consumers show greater acceptance and direct engagement with experiential service AISVs, suggesting that AI content applicability extends beyond purely functional domains.

Overall, consumer cognition of AI capabilities is evolving from mechanical and rational toward experiential and emotional dimensions, with AI literacy driving this transition. By clarifying the boundary conditions of AI literacy’s effect on purchase decisions, this study offers a new perspective on the differentiated impact of AI content marketing and provides a theoretical foundation for optimizing AI marketing strategies across product types.

The results show that information adoption’s impact on purchase intention is significantly stronger for tangible products (β=0.990) than for experiential services (β=0.813), with a difference of 0.177, highlighting the structural influence of product type on decision pathways. This finding aligns with Franke et al. (2023), who observed that consumers view technological products as more suitable for AI influencer endorsement, while also clarifying the underlying cognitive mechanisms. Actorless tangible product-oriented AISVs primarily present products with search attributes—features evaluable through information prior to purchase [

23]. In online environments where physical interaction is not possible, AISV-provided information serves as a critical surrogate cue for assessing quality and functionality. Consequently, information adoption plays a central mediating role for tangible products. This search attribute-oriented processing complements Liao and Sundar’s (2022) finding that consumers of search products prefer algorithmic recommendations, jointly indicating that product type shapes both preferences for AI application and fundamental information-processing pathways. Even highly AI-literate consumers rely on complete information adoption pathways when evaluating tangible products, confirming product type as a boundary condition for AI literacy’s influence.

In summary, this study elucidates the multi-level mechanisms by which AI literacy shapes AISV decision-making. The finding related to RQ1 shows that AI literacy influences information adoption through three parallel pathways: emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility, with the information usefulness pathway, based on “machine heuristics,” exhibiting the strongest effect and emphasizing consumers’ prioritization of utilitarian content. The finding regarding RQ2 confirms information adoption as a key antecedent to purchase intention and demonstrates that the “emotion–purchase conversion mechanism” requires mediation through information adoption. RQ3 identifies product type as a critical boundary condition: AI literacy directly affects purchase intention only for experiential services and operates via the information adoption pathway for tangible products. These contextual insights reveal the situational dependency of technological literacy’s impact on consumer decision-making, enriching digital marketing theory by clarifying cognitiveaffectivebehavioral conversion mechanisms. Overall, this study defines both the scope and boundaries of AI literacy’s influence, offering a systematic theoretical framework for understanding consumer behavior in emerging AI-driven marketing environments.

6. Theoretical Implications

This study extends the concept of digital immigrants by introducing the consumer classifications of AI immigrants and AI natives, based on differences in AI literacy. It develops the ALPDM, which traces how AI literacy influences information adoption via AISV perceived value and ultimately shapes purchase intention. This study makes three key theoretical contributions. First, by constructing the ALPDM, it addresses limitations of the traditional VAM by incorporating consumer AI literacy as a core antecedent, establishing the complete causal chain: AI literacy → value perception → information adoption → purchase intention. Unlike traditional VAM, which treats technology solely as a non-monetary cost that reduces perceived value [

29], ALPDM highlights the dual nature of technological understanding: initial learning represents a cost, whereas mastered technological capability becomes a cognitive resource that enhances AISV value perception. This distinction between “acquisition process” and “existing capability” strengthens the model’s explanatory power for AI content evaluation. Empirical results confirm that AI literacy significantly affects emotional value and information usefulness, validating ALPDM’s relevance for understanding consumer decision-making in the AI era.

Second, this study extends the ELM to AI content evaluation. While traditional ELM treats source credibility as a peripheral cue [

30], our results show that highly AI-literate consumers process source evaluation centrally, interpreting technological transparency as evidence of honesty and professional competence. By integrating AI literacy, ALPDM clarifies how consumers form new information-processing mechanisms, offering a more precise theoretical framework and enhancing ELM’s explanatory power in AI-driven contexts.

Third, this study identifies systematic differences in AI literacy’s influence across AISV types. For actorless tangible product AISVs, AI literacy affects purchase intention indirectly through information adoption, whereas for avatar-mediated experiential service AISVs, it can directly drive purchase decisions. This finding establishes the contextual boundaries of ALPDM and provides empirical insight into AIGC’s differential effects.

7. Managerial Implications

Based on ALPDM and the empirical findings, this research offers two key managerial implications for content creators and businesses using AI synthetic video marketing.

First, AISV content strategies should follow the consumer value assessment sequence: utilitarian value, emotional value, and trust. Accordingly, creators should construct a three-tier content architecture by establishing usefulness through functional information, incorporating emotional elements to evoke resonance, and building trust via vlogger roles. For AI natives and AI immigrants with digital empathy capabilities, businesses should enhance immersive experiences using precise audiovisual elements and multisensory cues, thereby improving content resonance, memory retention, differentiation, and conversion efficiency.

Second, the pathway differences revealed by ALPDM provide a theoretical basis for differentiated consumer decision guidance strategies. For avatar-mediated experiential services, marketers should focus on perception-enhancing AISV content, incorporating elements such as muscle activation prompts, joint force markers, and slow-motion demonstrations in AI virtual coach videos. This allows high AI literacy users to mentally simulate outcomes, bypass credibility assessment, and form direct purchase intentions, leveraging their cognitive advantages.

For tangible product AISVs, businesses should implement decision-transparent systems that disclose AIGC and explain the rationale behind it—for instance, revealing recommendation logic in clothing displays or enabling real-time rendering adjustments in home furnishing videos. Such explainable AI strategies reduce resistance to black-box algorithms [

59], increase perceived control, and improve information adoption and conversion rates.

Moreover, businesses should offer tiered transparency based on users’ AI literacy, providing detailed explanations for high-literacy users and simplified guidance for low-literacy users, aligning cognitive needs with marketing efficiency to create competitive advantage in the AI-driven marketplace.

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite providing valuable insights into AISV influence mechanisms, this study has notable limitations. First, in conceptualizing AI literacy, we selectively incorporated the technological application, cognitive understanding, and detection identification dimensions from Carolus et al. (2023), excluding the ethical dimension owing to its contextual misalignment with passive AISV consumption. Future research could integrate AI ethical cognition as an independent construct, systematically examining its effects across AI applications and exploring interactions with technological literacy. Second, this study has limitations in product type grouping. Social media recommendation algorithms expose users to multiple content types rather than a single product category. To maintain statistical power, we did not analyze “tangible products only” or “experiential services only” groups. Instead, we employed multi-group SEM to compare tangible product groups, experiential service groups, mixed viewing groups, and the overall sample. Future research could use experimental designs assigning participants to single product type conditions or larger-scale sampling to balance ecological validity with statistical robustness.

9. Conclusions

This study demonstrates how consumer AI literacy shapes AISV marketing effectiveness. AI literacy influences information adoption through three pathways—emotional value, information usefulness, and source credibility—with information usefulness exerting the strongest effect. Product type acts as a critical boundary condition: AI literacy directly affects purchase intention in experiential service AISVs but operates indirectly via information adoption in tangible product AISVs. This study’s contribution to marketing management lies in systematically revealing how AI literacy drives consumer decision-making, addressing a theoretical gap regarding its role in marketing acceptance. For scholars, ALPDM offers a novel perspective, advancing theory from traditional contentresponse frameworks to multi-level models that account for consumer technological capabilities. For practitioners, the findings inform differentiated AISV strategies: Experiential service marketers should emphasize anthropomorphic elements, while tangible product marketers should enhance technological transparency to build AI trust. This theory-driven approach can improve marketing effectiveness and support sustainable competitive advantage in digital environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Qianwen Liu and Lokhman Hakim Osman; methodology, Lokhman Hakim Osman and Che Aniza Che Wel; data curation, Qianwen Liu and Zhongxing Lian; software, Zhongxing Lian; formal analysis, Qianwen Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Qianwen Liu; writing—review and editing, Qianwen Liu; supervision, Lokhman Hakim Osman; project administration, Lokhman Hakim Osman; language editing, Siti Ngayesah Ab. Hamid. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research Ethics Committee (Ref. No. JEP-2024-382, 09 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all team members, whose collective efforts and perseverance made it possible to complete this study despite the challenges encountered.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AIGA |

Artificial Intelligence-Generated Advertising |

| AIGC |

Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content |

| AISV |

Artificial Intelligence-Generated Sponsored Vlogs |

| ALPDM |

AI Literacy Perception-Decision Model |

| ELM |

Elaboration Likelihood Model |

| VAM |

Value-Based Adoption Model |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modelling |

References

- Kumar, V.; Ashraf, A.R.; Nadeem, W. AI-Powered Marketing: What, Where, and How? International Journal of Information Management 2024, 77, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Lee, Y. Effects of Fashion Vlogger Attributes on Product Attitude and Content Sharing. Fashion and Textiles 2019, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratta, A.A.; Muneer, S.; Hassan, H. ul The Impact of AI Generated Advertising Content on Consumer Buying Intention and Consumer Engagement. Bulletin of Business and Economics 2024, 13, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelt, C.; Röser, A.M. Transforming the Operational Components of Marketing Processes with GenAI: A Paradigm Shift. Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning 2024, 4, 2535–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, J. Asking Questions of AI Advertising: A Maieutic Approach. Journal Of Advertising 2022, 51, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, C.; Allerborg, H. How Do Different Factors Influence Customer Satisfaction in the Context of AI Marketing? A YouTube-Ads Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TikTok e-commerce; SocialBeta 2025 Youth Emotional Consumption Trend Report. TikTok E-commerce Marketing Observatory 2025. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vsxTsTMsKUeoE56MuI7kvA (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Argan, M.; Dinc, H.; Kaya, S.; Argan, M.T. Artificial Intelligence in Advertising Understanding and Schematizing the Behaviors of Social Media Users. Advances In Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence Journal 2023, 11, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Gupta, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Paul, J.; Sadhna, P. How Do Digital Natives Perceive and React toward Online Advertising? Implications for SMEs. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2024, 32, 1071–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M.A. Market Signaling: Information Transfer in Hiring and Related Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Almatrafi, O.; Johri, A.; Lee, H. A Systematic Review of AI Literacy Conceptualization, Constructs, and Implementation and Assessment Efforts (2019–2023). Computers and Education Open 2024, 6, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, O.H.; Lu, L.; Nunkoo, R. Consumers Acceptance of Artificially Intelligent Device Use in Service Delivery. International Journal Of Information Management 2019, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, G.; Businaro, S.; Zancanaro, M. Comprehension, Apprehension, and Acceptance: Understanding the Influence of Literacy and Anxiety on Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence. Technology in Society 2024, 77, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wen, T.J. Understanding AI Advertising from the Consumer Perspective. Journal Of Advertising Research 2021, 61, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Hill, S.R.; Li, B. Consumer Attitudes toward AI-Generated Ads: Appeal Types, Self-Efficacy and AI’s Social Role. Journal Of Business Research 2024, 185, 114867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, D.; Lemoine, J.-F. Bridging the Gap: User Expectations for Conversational AI Services with Consideration of User Expertise. Journal Of Services Marketing 2025, 39, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Boerman, S.C.; Kroon, A.C.; Möller, J.; Vreese, C.H. de The Artificial Intelligence Divide: Who Is the Most Vulnerable? New Media & Society 2024, 27, 3867–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Huang, M. Can Personalized Recommendations in Charity Advertising Boost Donation? The Role of Perceived Autonomy. Journal Of Advertising 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, U.A.; Moustafa, A.M.A.; Ghani, M.A. They Misused Me! Digital Literacy’s Dual Role in AI Marketing Manipulation and Unethical Young Consumer Behavior. Young Consumers 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chu, S.-C.; Cao, Y. Adopting AI Advertising Creative Technology in China: A Mixed Method Study Through the Technology-Organization-Environment Framework, Perceived Value and Ethical Concerns. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 2024, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Dodoo, N.A.; Wen, T.J. Disclosing AI’s Involvement in Advertising to Consumers: A Task-Dependent Perspective. Journal Of Advertising 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spais, G.; Jain, V. Consumer Behavior’s Evolution, Emergence, and Future in the AI Age Through the Lens of MR, VR, XR, Metaverse, and Robotics. Journal Of Consumer Behaviour 2025, 24, 1275–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Sundar, S. When E-Commerce Personalization Systems Show and Tell: Investigating the Relative Persuasive Appeal of Content-Based versus Collaborative Filtering. Journal Of Advertising 2021, 51, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Müller, K. Consumers’ Responses to Virtual Influencers as Advertising Endorsers: Novel and Effective or Uncanny and Deceiving? Journal of Advertising 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, S.D.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. How an Advertising Disclosure Alerts Young Adolescents to Sponsored Vlogs: The Moderating Role of a Peer-Based Advertising Literacy Intervention through an Informational Vlog. Journal of Advertising 2018, 47, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Singh, D.K. A Novel Aspect of Automatic Vlog Content Creation Using Generative Modeling Approaches. Digital Signal Processing 2024, 148, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, B.J.; Iredale, S.; Naudé, P. Examining the Dark Force Consequences of AI as a New Actor in B2B Relationships. Industrial Marketing Management 2023, 115, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinski, M.; Hofmann, T.; Benlian, A. AI Literacy for the Top Management: An Upper Echelons Perspective on Corporate AI Orientation and Implementation Ability. Electronic Markets 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Chan, H.C.; Gupta, S. Value-Based Adoption of Mobile Internet: An Empirical Investigation. Decision Support Systems 2007, 43, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Goldman, R. Personal Involvement as a Determinant of Argument-Based Persuasion. Journal Of Personality and Social Psychology 1981, 41, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J. Development of a Multi-Dimensional Scale for Measuring the Perceived Value of a Service. Journal Of Leisure Research 2002, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.; Soutar, G. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. Journal Of Retailing 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullatif, A.M.; Alsubaie, M.A. ChatGPT in Learning: Assessing Students’ Use Intentions through the Lens of Perceived Value and the Influence of AI Literacy. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.C.M.; Ho, P.S.S.; Armutcu, B.; Tan, A.; Butt, M.-K. Role of Culture in How AI Affects the Brand Experience: Comparison of Belt and Road Countries. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu-Thompkins, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Li, H. Artificial Empathy in Marketing Interactions: Bridging the Human-AI Gap in Affective and Social Customer Experience. Journal Of the Academy Of Marketing Science 2022, 50, 1198–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Cian, L. Artificial Intelligence in Utilitarian vs. Hedonic Contexts: The “Word-of-Machine” Effect. Journal Of Marketing 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Zhang, J. Dual-Pathway Effects of Product and Technological Attributes on Consumer Engagement in Augmented Reality Advertising. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2025, 20, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Shen, H.; Wu, L.; Mattila, A.; Bilgihan, A. Whom Do We Trust? Cultural Differences in Consumer Responses to Online Recommendations. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2018, 3, 1508–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, C.; Alur, S. Ad Generation Modalities and Response to In-App Advertising – an Experimental Study. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Vrontis, D.; Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S. Entrepreneurship Strategy through Social Commerce Platform: An Empirical Approach Using Contagion Theory and Information Adoption Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, S.; Demsar, V.; Ferraro, C.; Wilson, S.; Wheeler, M.; Campbell, C. Easing AI-Advertising Aversion: How Leadership for the Greater Good Buffers Negative Response to AI-Generated Ads. International Journal of Advertising 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What Is AI Literacy? In Competencies and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W.; Goh, W.W.; Chong, A.Y.L. Examining the Antecedents of Persuasive EWOM Messages in Social Media. Online Information Review 2014, 38, 746–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What Leads Students to Adopt Information from Wikipedia? An Empirical Investigation into the Role of Trust and Information Usefulness. British Journal of Educational Technology 2012, 44, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C. Effect of EWOM Review on Beauty Enterprise: A New Interpretation of the Attitude Contagion Theory and Information Adoption Model. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 2021, 35, 376–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TikTok E-commerce. 2021 TikTok E-Commerce Annual Data Report. TikTok E-commerce Marketing Observatory 2022. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vsxTsTMsKUeoE56MuI7kvA (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Carolus, A.; Koch, M.; Straka, S.; Latoschik, M.; Wienrich, C. MAILS - Meta AI Literacy Scale: Development and Testing of an AI Literacy Questionnaire Based on Well-Founded Competency Models and Psychological Change- and Meta-Competencies. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2023, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, R.A.; Qayyum, A. Word of Mouse vs Word of Influencer? An Experimental Investigation into the Consumers’ Preferred Source of Online Information. Management Research Review 2021, 45, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaban, P.H.; Chen, W.-K.; Sormin, S.; Panjaitan, Y.N.B.P.; Silalahi, A.D.K. How Does Electronic Word of Mouth on Instagram Affect Travel Behaviour in Indonesia: A Perspective of the Information Adoption Model. Cogent Social Sciences 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I. The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth in Social Media on Consumers’ Purchase Intention

. Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Dodoo, N.A.; Wen, T.J.; Ke, L. Understanding Twitter Conversations about Artificial Intelligence in Advertising Based on Natural Language Processing. International Journal of Advertising 2021, 41, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Du, H. Electronic Word-of-Mouth from Video Bloggers: The Role of Content Quality and Source Homophily across Hedonic and Utilitarian Products. Journal Of Business Research 2023, 160, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Q. The Effectiveness of Human vs. AI Voice-over in Short Video Advertisements: A Cognitive Load Theory Perspective. Journal of Retailing And Consumer Services 2024, 81, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L. Grounded Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Craighero, L. The Mirror-Neuron System. Annual review of neuroscience 2004, 27, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.I.; Gonçalves, J.N.C.; Cortez, P.; Carvalho, M.S.; Fernandes, J.M. A Context-Aware Decision Support System for Selecting Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods in Business Organizations. Computers in Industry 2025, 165, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.; Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).