Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

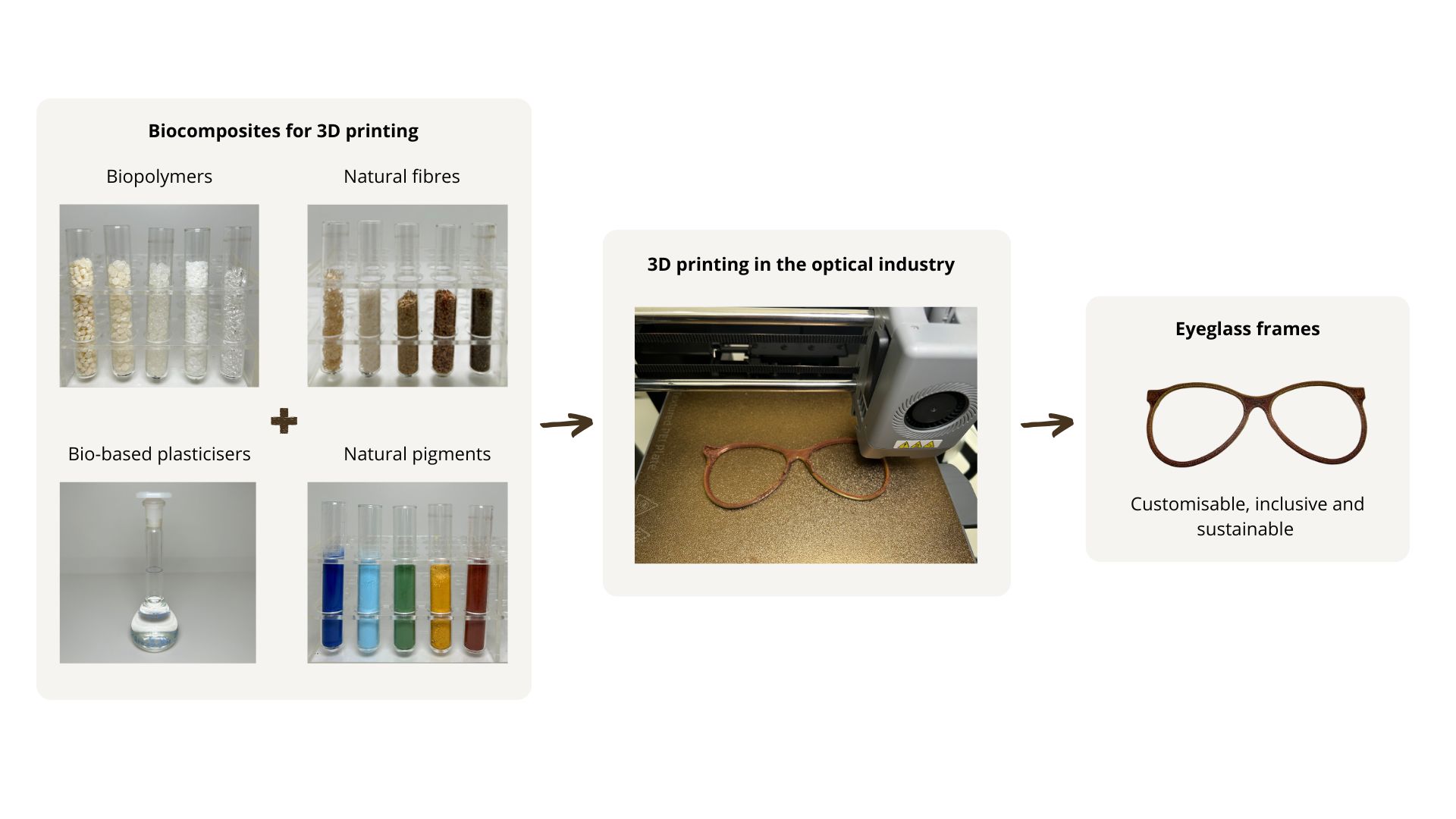

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

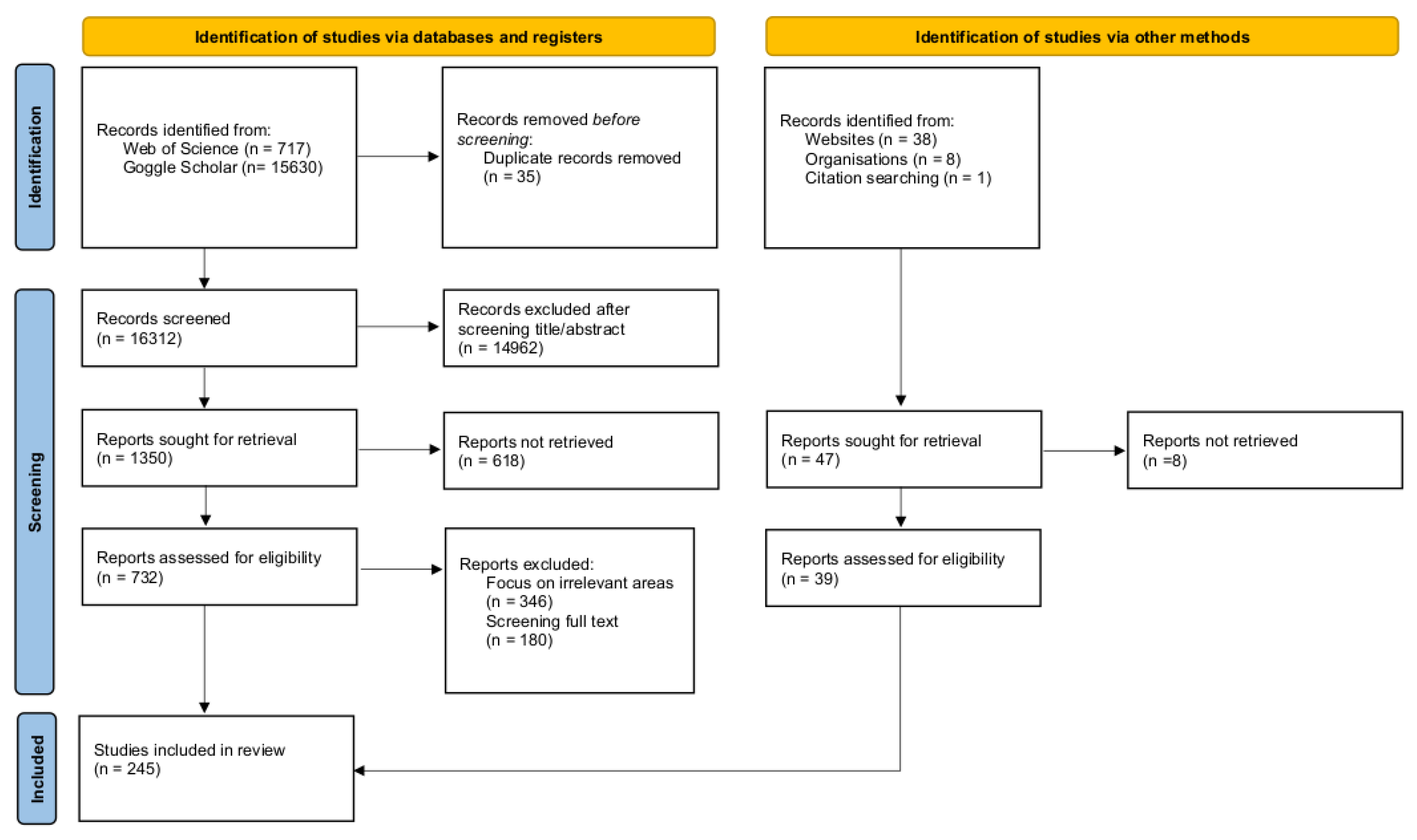

2. Method

3. Requirements in the Development of New Materials for Optical Frames

4. Biomaterials for Optical Frames

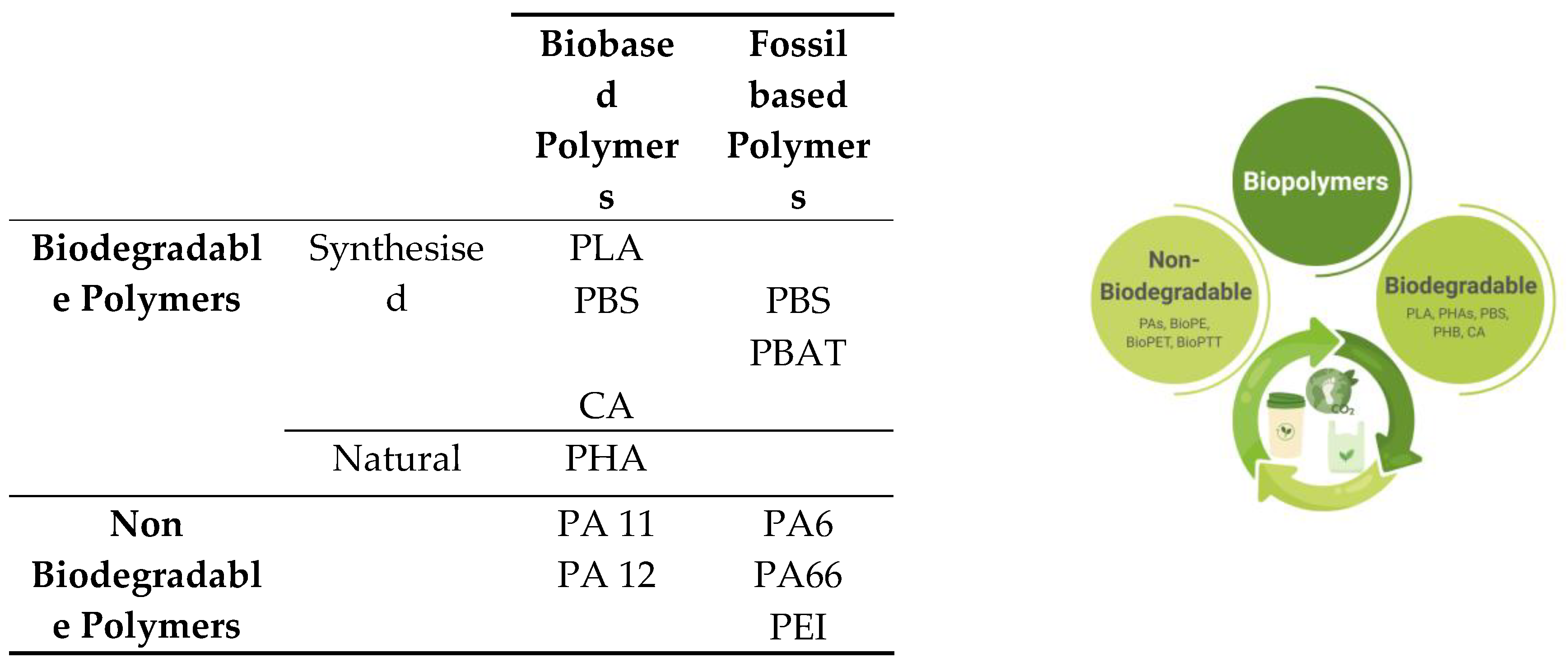

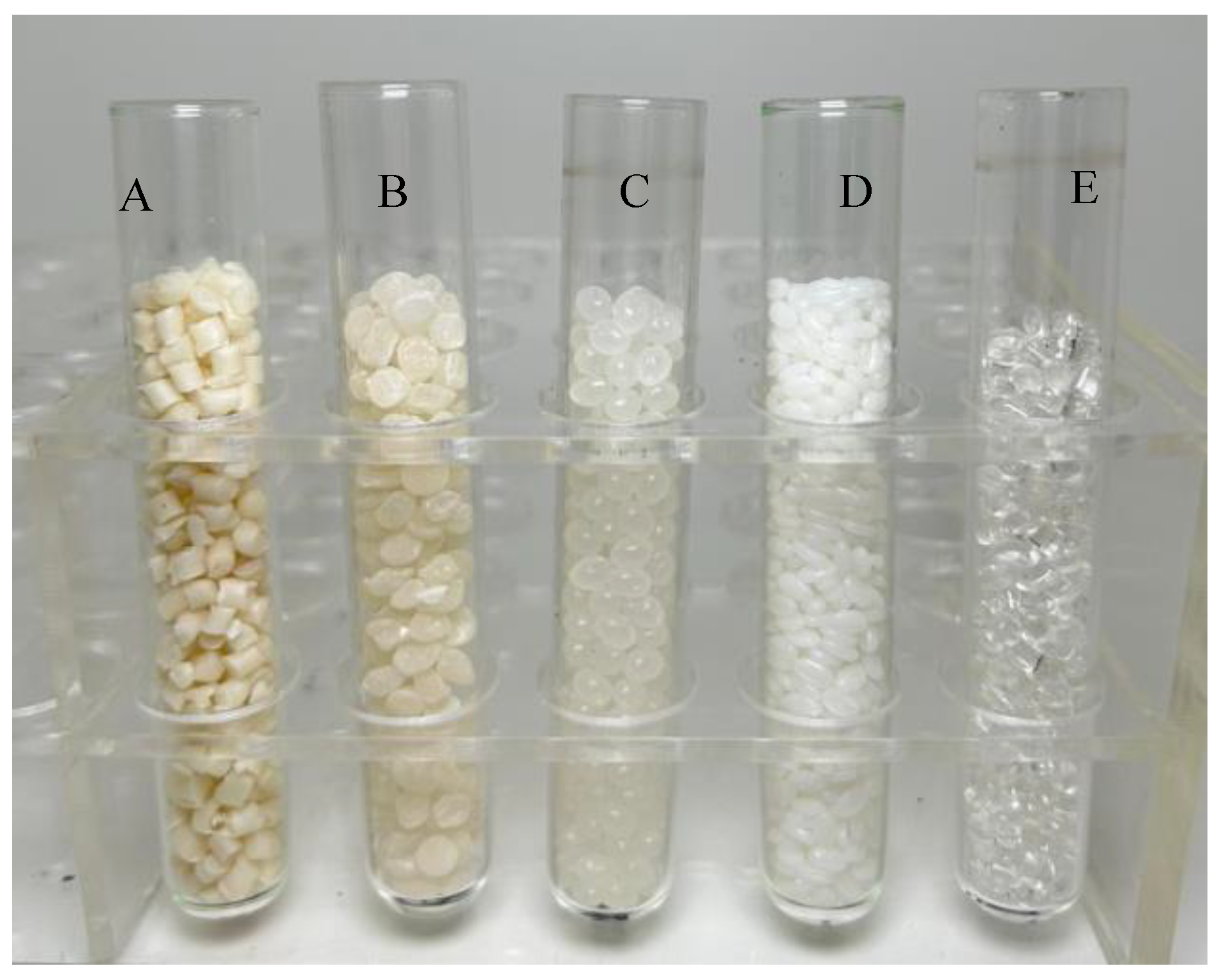

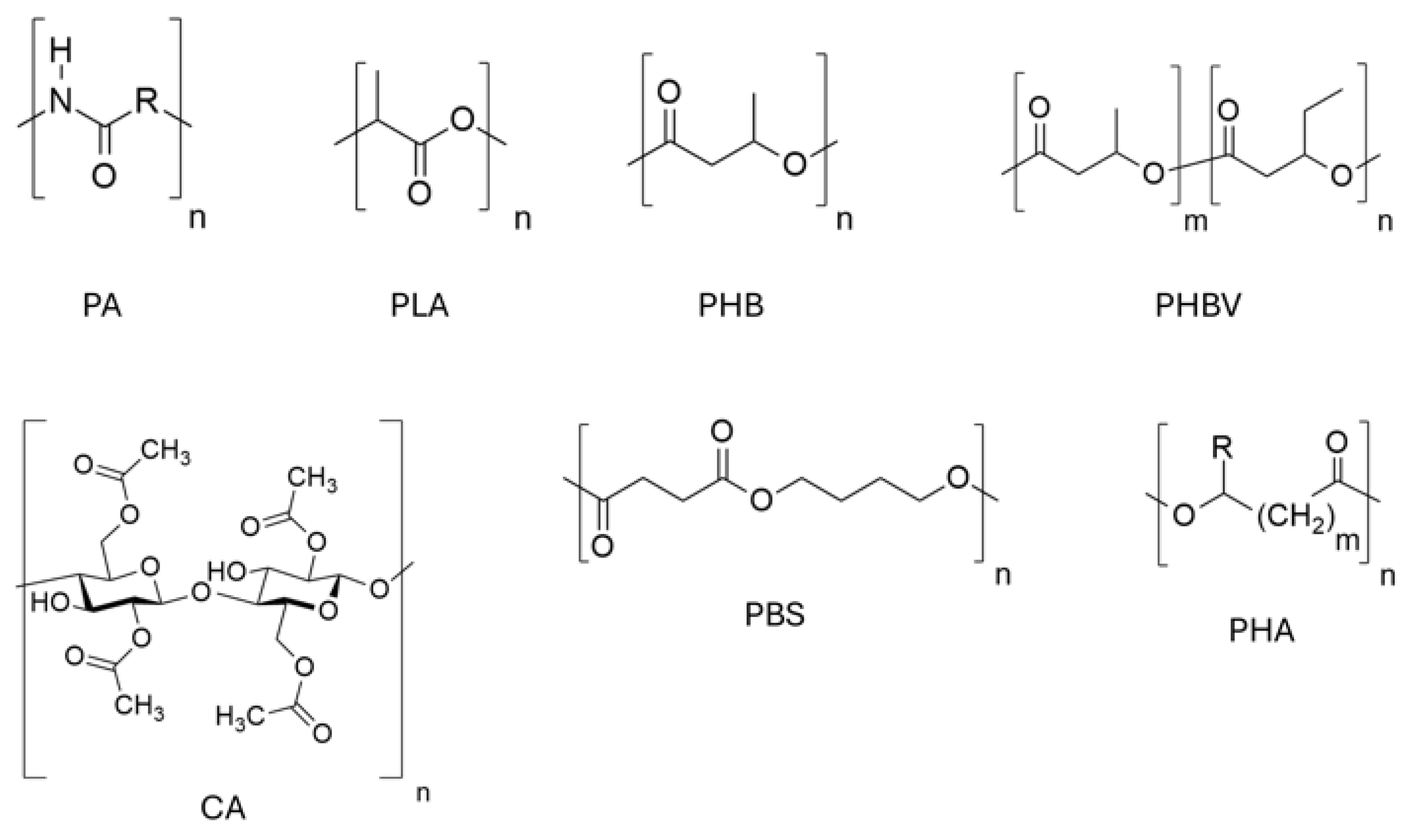

4.1. Biopolymers

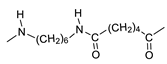

4.1.1. Polyamides (PAs)

4.1.2. Polybutylene Succinate (PBS)

4.1.3. Polylactic Acid (PLA)

4.1.4. Cellulose Acetate (CA)

4.1.5. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs)

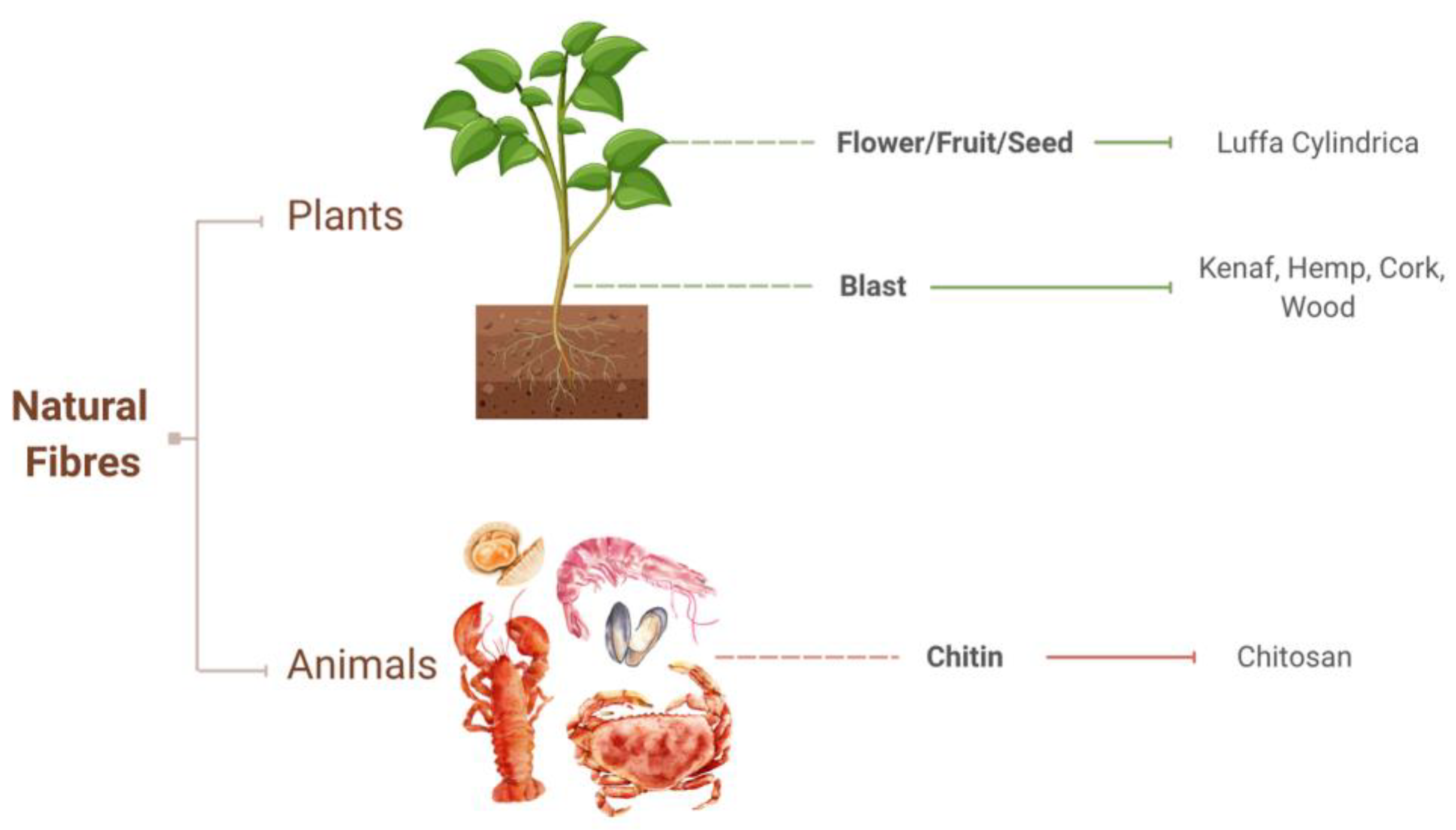

4.2. Natural Fibres for Enhanced Biopolymeric Composites

4.2.1. Wood

4.2.2. Cork

4.2.3. Luffa Cylindrica

4.2.4. Kenaf

4.2.5. Hemp

4.2.6. Chitosan

4.3. Additives

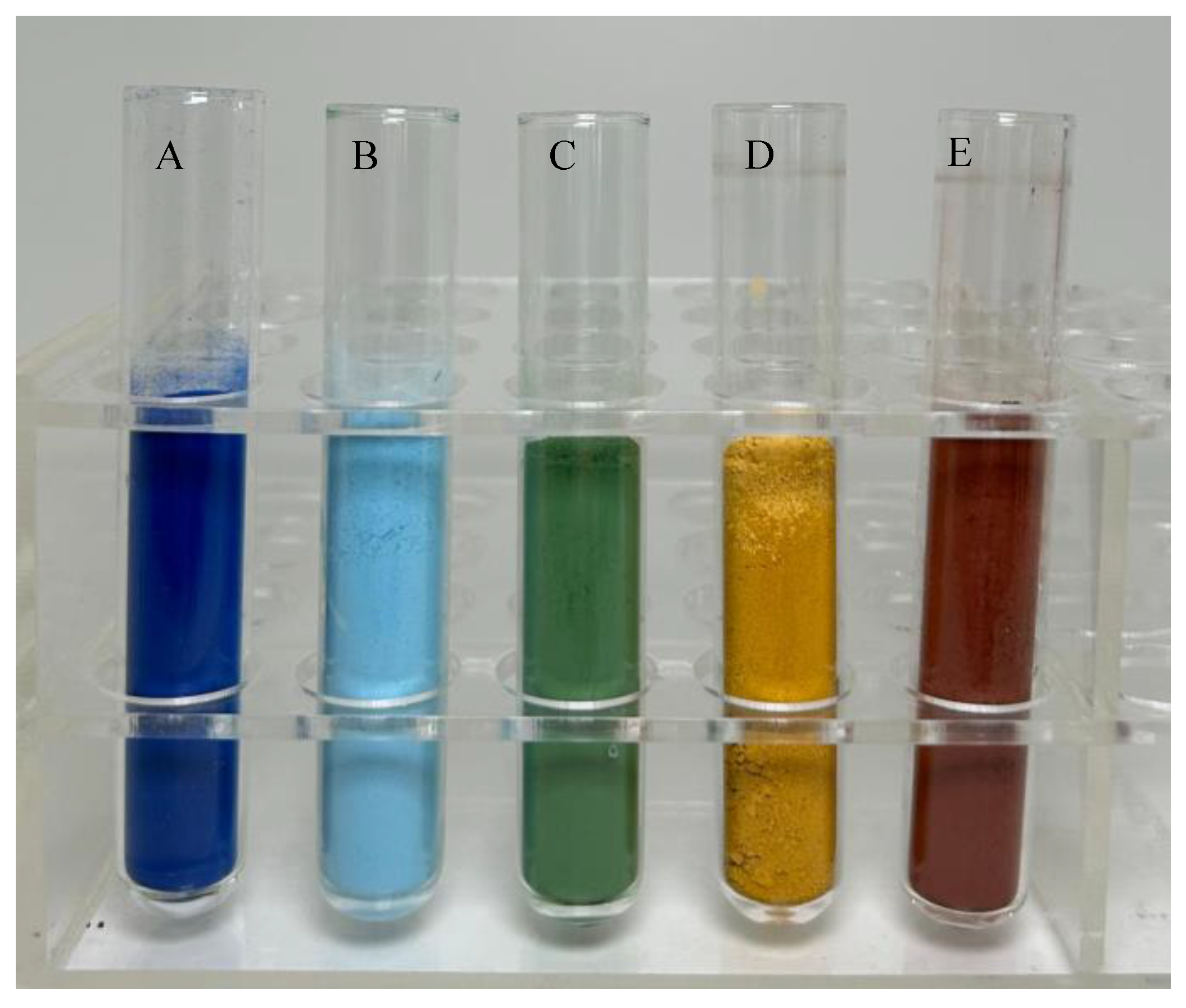

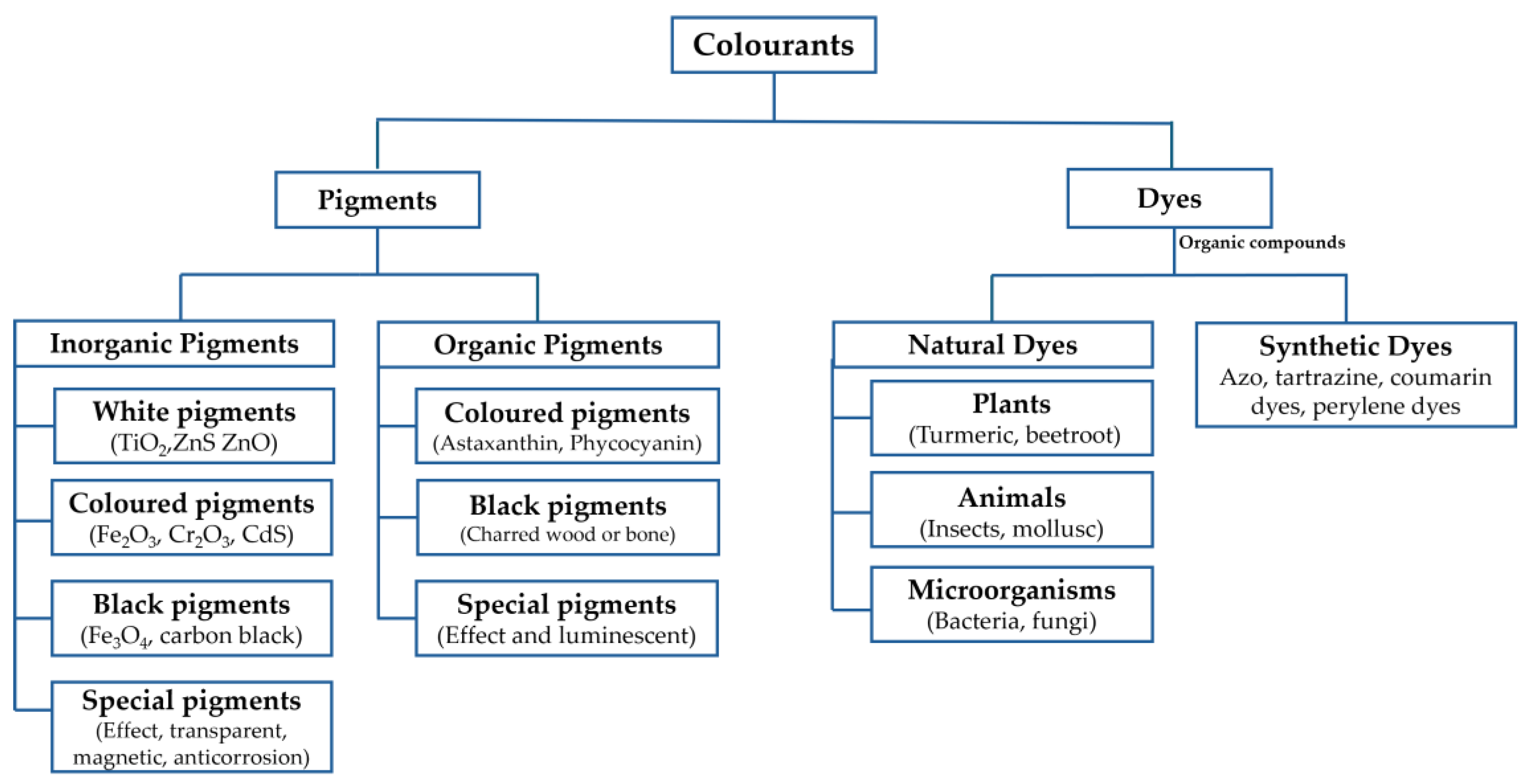

4.3.1. Colourants: Pigments and Dyes for Incorporation in Biocomposites

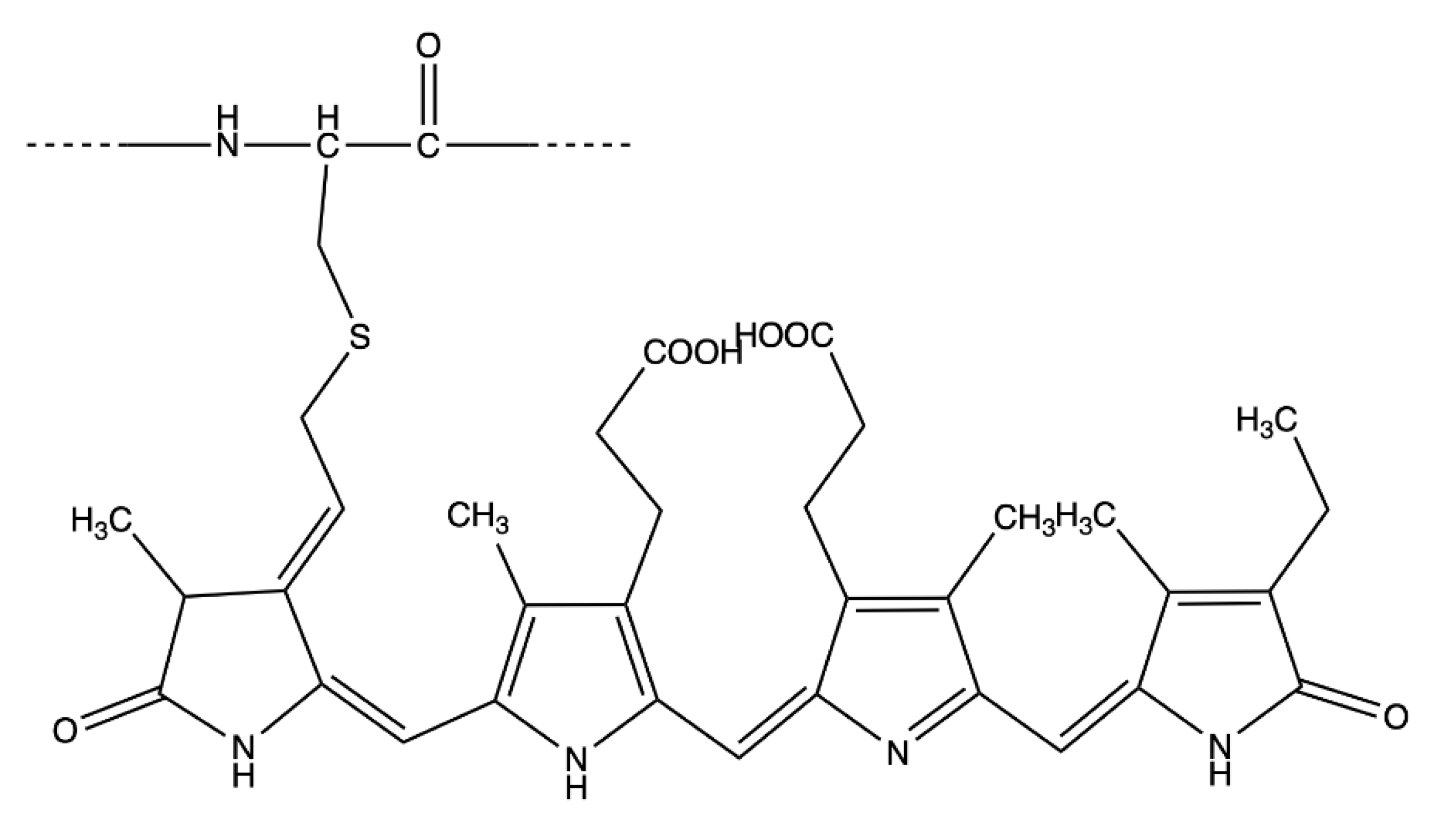

- Phycocyanin (PC)

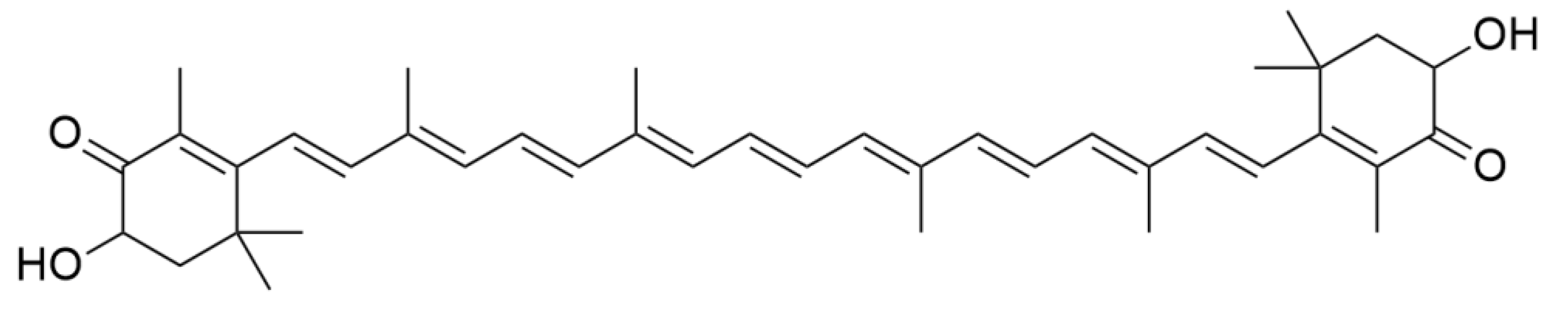

- Astaxanthin (ASX)

- Iron Oxides

4.3.2. Plasticisers

- Isosorbide-based plasticisers

- Citric acid ester plasticisers

- Glycerol-based plasticisers

- Essential oils

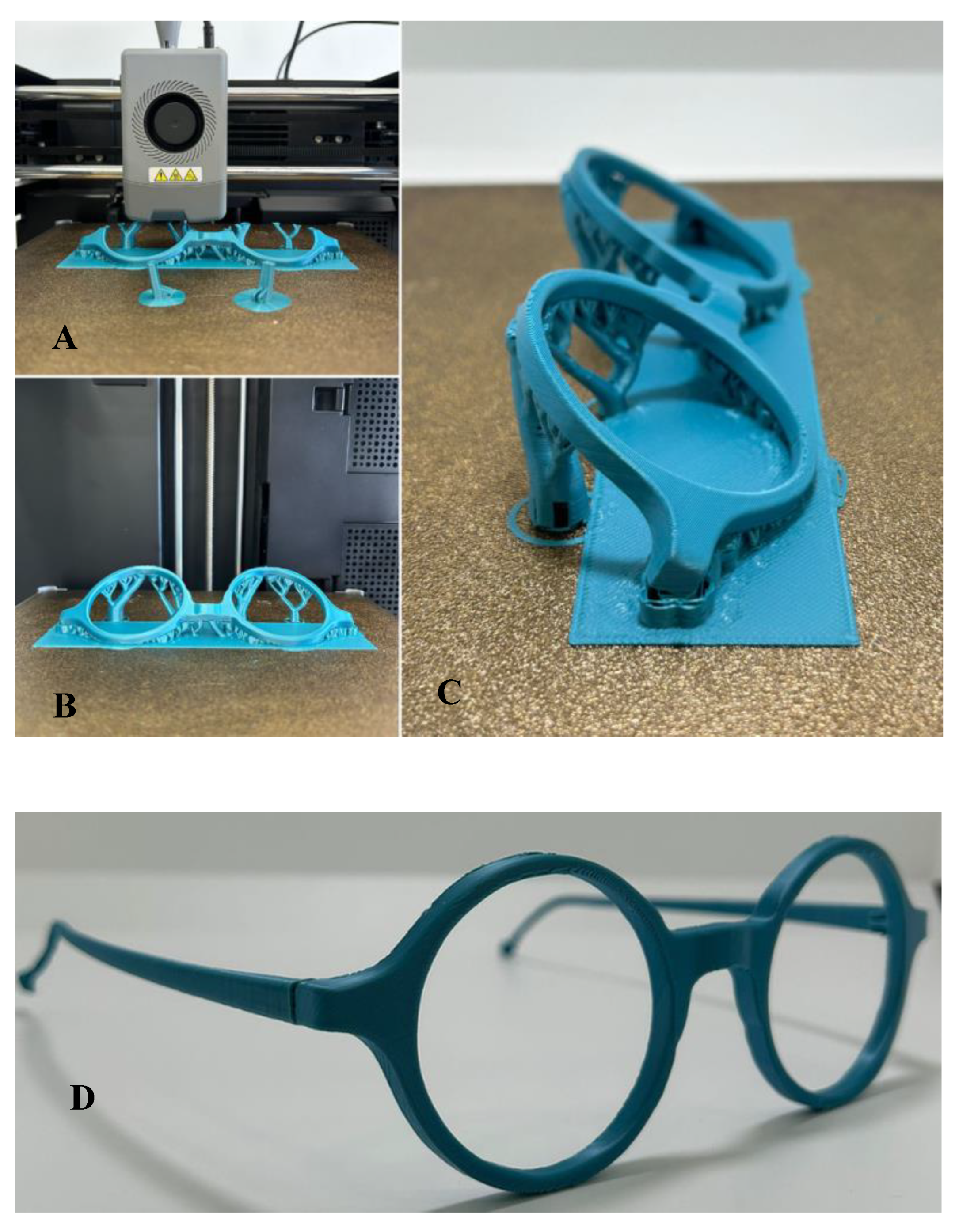

5. Additive Manufacturing and the Optics Industry

5.1. Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM)

5.2. Stereolithography

5.3. Digital Light Processing (DLP)

5.4. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

5.5. Multi Jet Fusion (MJF)

6. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

| Company | Handcraft | Injection | 3D Printing | Polymer | References |

| Neostyle | x | x | PE – for 3D printing CA – for handcraft |

[226] | |

| Formlabs | x | PA 11 powder PA 12 powder |

[227] | ||

| Monoqool | x | PA |

[228] | ||

| Mykita | x | x | PA - for 3D Printing CA – for handcraft |

[229] | |

| Materialise | x | PA 12 PA 11 |

[230] | ||

| Viu | x | x | PA - for 3D Printing CA – for handcraft CA – for handcraft |

[231] | |

| Favr | x | CA | [232] | ||

| Yoface | x | PP PA12 | [233] | ||

| Silhouette | x | x | Natural3D® - for 3D Printing NaturalPX® - for 3D Printing |

[234] | |

| Igreen | x | x | CA - for 3D Printing ECO PLASTICA – for injection PEI – for injection |

[235] | |

| Stratasys | x | ABS | [236] | ||

| Götti | x | x | PA 12 - for 3D Printing PA - for 3D Printing CA – for handcraft Buffalo horn – for handcraft |

[237] | |

| Klenze & Baum | x | SLEEK ECOLUCENT® SLEEK ACELIKE® PA 11 powder PA 12 powder |

[238] | ||

| Neubau | x | x | x | CA – for handcraft NATURAL 3D® - for 3D Printing NATURAL PXevo® - for Injection |

[239] |

| Rolf. | x | Castor Bean | [240] | ||

| Manti Mant | x | PA | [241] | ||

| Adidas | x | PA | [242] | ||

| Hala Optical | x | CA G850, EMS, TR90 |

[243] | ||

| La Giardinier | x | CA Grilamid® TR90 Propionate of Cellulose (CP) Tenite® PP Megol® (SEBS: a thermoplastic rubber) ACETATE M49 |

[244] |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| ASX | Astaxanthin |

| ATBC | Acetyl-Tributyl Citrate |

| BBP | Benzyl Butyl Phthalate |

| BioPE | Biopolyethylene |

| BioPET | Bio Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| BioPTT | Bio Polytrimethylene Terephthalate |

| CA | Cellulose Acetate |

| CP | Propionate of Cellulose |

| Cr | Chromium |

| DEHP | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| DMD | Digital Mirror Device |

| DOP | Dioctyl Terephthalate |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modelling |

| Fe | Iron |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| GMS | Glycerol Monostearate |

| GT | Glycerol Tributyrate |

| LCD | Liquid Crystal Display |

| MCPH/SCKS | Autosomal Recessive Microcephaly and Seckel Syndrome |

| MJF | Multi Jet Fusion |

| OSA | Oligo(isosorbide adipate) |

| OSS | Oligo(isosorbide suberate) |

| P3HB | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) |

| PA 11 | Polyamide 11 |

| PA 12 | Polyamide 12 |

| PAs | Polyamides |

| PBAT | Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate |

| PBS | Polybutylene Succinate |

| PC | Phycocyanin |

| PDLA | Poly(d-lactide) |

| PDLLA | Poly(dl-lactide) |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PEI | Polyetherimide |

| PETG | Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol |

| PHAs | Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| PHB | Polyhydroxybutyrate |

| PHBHHx | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) |

| PHBV or P3HB3HV | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PLLA | Poly(l-lactide) |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDH | Isosorbide Dihexanoate |

| SDO | Isosorbide Dioctate |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| TA | Triacetin |

| TBC | Tributyl citrate |

| TC | Tributyl citrate |

| Tc | Crystallization Temperature |

| Td | Degradation Temperature |

| Tg | Glass Transition Temperature |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| UN | United Nations |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) Blindness and Vision Impairment.

- Ayaki, M.; Hanyuda, A.; Negishi, K. Presbyopia and Associated Factors Specific to Age Groups. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, S.; O’Dwyer, V. The Association between Time Spent on Screens and Reading with Myopia, Premyopia and Ocular Biometric and Anthropometric Measures in 6- to 7-year-old Schoolchildren in Ireland. Ophthalmic Physiologic Optic 2023, 43, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Molaeefar, S.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Beiromvand, M.; Bagheri, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global Prevalence of Myopia in Children Using Digital Devices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Pediatr 2025, 25, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, M. Global Trends in Refractive Disorders from 1990 to 2021: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study and Predictive Modeling. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1449607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, T.R.; Tahhan, N.; Resnikoff, S.; Papas, E.; Burnett, A.; Ho, S.M.; Naduvilath, T.; Naidoo, K.S. Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.P.; Ramke, J.; Cairns, J.; Butt, T.; Zhang, J.H.; Muirhead, D.; Jones, I.; Tong, B.A.M.A.; Swenor, B.K.; Faal, H.; et al. Global Economic Productivity Losses from Vision Impairment and Blindness. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuka-Nicoulaud, E.; Naidoo, K.; Gross, K.; Marcano Williams, J.; Kirsten-Coleman, A. The Power of Advocacy: Advancing Vision for Everyone to Meet the Sustainable Development Goals. Int J Public Health 2022, 67, 1604595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E. Visual Acuity Test. In Primary Eye Examination; Lee, J.-S., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 978-981-10-6939-0. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Statista Market Forecast. 2025,.

- Juliana Araújo; Pedro Ramos; Elsa Silvestre; Artur Mateus; Anabela Massano; Timur Nikitin; Pedro Silva; Jorge Guiomar; Pedro Cruz; Abílio Sobral; et al. Physical and Chemical Characterisation of Ophthalmic Lenses Grinding Wastewater: Uncovering Environmental Implications.

- Hansraj, R. Spectacle Frames: Disposal Practices, Biodegradability and Biocompatibility – A Pilot Study.

- Encarnação, T.; Nicolau, N.; Ramos, P.; Silvestre, E.; Mateus, A.; Carvalho, T.A.D.; Gaspar, F.; Massano, A.; Biscaia, S.; Castro, R.A.E.; et al. Recycling Ophthalmic Lens Wastewater in a Circular Economy Context: A Case Study with Microalgae Integration. Materials 2023, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Eyewear with 100% Bio-Based 3D Printing Material. Available online: https://www.materialise.com/en/news/press-releases/sustainable-eyewear-bio-based-3d-printing-material (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Óculos de alto desempenho que aproveitam a impressão 3D | Manufatura Digital 2025.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 12879:2024 Ophthalmic Optics — Spectacle Frames — Requirements and Test Methods; 2024.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO10993-10:2021 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Part 10: Tests for Skin Sensitization; 2021.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 10993-2:2022 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Part 2: Animal Welfare Requirements; 2022.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 16128-2_2017 Cosmetics — Guidelines on Technical Definitions and Criteria for Natural and Organic Cosmetic Ingredients; 2017.

- Department of Biophysics and Biochemistry, Baku State University, Baku, Azerbaijan; Khalilov, R. K. FUTURE PROSPECTS OF BIOMATERIALS IN NANOMEDICINE. ABES 2024, 9, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Encarnação, T.; Tavares, R.; Todo Bom, T.; Mateus, A. Bioplastics: Innovation for Green Transition. Polymers 2023, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOPLASTICS MARKET DEVELOPMENT UPDATE 2023.

- Krishna, S.; Sreedhar, I.; Patel, C.M. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Polyamide-Based Materials – A Review. Computational Materials Science 2021, 200, 110853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paari-Molnar, E.; Qa’dan, W.N.A.; Kardos, K.; Told, R.; Sahai, N.; Varga, P.; Rendeki, S.; Szabo, G.; Fekete, K.; Molnar, T.; et al. Biomedical Applications of 3D-Printed Polyamide: A Systematic Review. Macro Materials & Eng. [CrossRef]

- Shakiba, M.; Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Khosravi, F.; Jouybar, S.; Bigham, A.; Zare, M.; Abdouss, M.; Moaref, R.; Ramakrishna, S. Nylon—A Material Introduction and Overview for Biomedical Applications. Polymers for Advanced Techs 2021, 32, 3368–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griehl, Wolfgang. ; Ruestem, Djavid. Nylon-12-Preparation, Properties, and Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1970, 62, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Textile Fibres. Volume 1. Natural Fibers; Cook, J.G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles; Fifth edition. Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, England Philadelphia, Pennsylvania New Delhi, India, 2012; ISBN 978-1-85573-484-5. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, R.J. ; Updated by Staff Polyamides, Plastics. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; Kirk-Othmer, Ed.; Wiley, 2005 ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3.

- Nanda, S.; Patra, B.R.; Patel, R.; Bakos, J.; Dalai, A.K. Innovations in Applications and Prospects of Bioplastics and Biopolymers: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2022, 20, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegay, F.; Ghannam, R.; Daniel, N.; Butt, H. 3D Printing Smart Eyeglass Frames: A Review. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculpteo Nylon PA12 3D Printing Material.

- Rahim, T.N.A.T.; Abdullah, A.M.; Md Akil, H.; Mohamad, D.; Rajion, Z.A. The Improvement of Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Polyamide 12 3D Printed Parts by Fused Deposition Modelling. Express Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.M.; Rahim, T.N.A.T.; Hamad, W.N.F.W.; Mohamad, D.; Akil, H.M.; Rajion, Z.A. Mechanical and Cytotoxicity Properties of Hybrid Ceramics Filled Polyamide 12 Filament Feedstock for Craniofacial Bone Reconstruction via Fused Deposition Modelling. Dental Materials 2018, 34, e309–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Jin, S.; Yokozeki, T.; Ueda, M.; Yang, Y.; Elbadry, E.A.; Hamada, H.; Sugahara, T. Effect of Hot Water on the Mechanical Performance of Unidirectional Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Nylon 6 Composites. Composites Science and Technology 2020, 200, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Patel, C.M. Computational and Experimental Study of Mechanical Properties of Nylon 6 Nanocomposites Reinforced with Nanomilled Cellulose. Mechanics of Materials 2020, 143, 103318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, V.; Rodrigue, D. Recycling of Polyamides: Processes and Conditions. Journal of Polymer Science 2023, 61, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Told, R.; Ujfalusi, Z.; Pentek, A.; Kerenyi, M.; Banfai, K.; Vizi, A.; Szabo, P.; Melegh, S.; Bovari-Biri, J.; Pongracz, J.E.; et al. A State-of-the-Art Guide to the Sterilization of Thermoplastic Polymers and Resin Materials Used in the Additive Manufacturing of Medical Devices. Materials & Design 2022, 223, 111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Kechagias, J.D. Parameter Effects and Process Modelling of Polyamide 12 3D-Printed Parts Strength and Toughness. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2022, 37, 1358–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ráž, K.; Chval, Z.; Thomann, S. Minimizing Deformations during HP MJF 3D Printing. Materials 2023, 16, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Li, Z.; Luan, C.; Wang, Z.; Yao, X.; Fu, J. Additive Manufacturing of Polyamide 66: Effect of Process Parameters on Crystallinity and Mechanical Properties. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 2022, 31, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, W.S.; Cai, C.; Zhou, K. A Comprehensive Investigation on 3D Printing of Polyamide 11 and Thermoplastic Polyurethane via Multi Jet Fusion. Polymers 2021, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, R.; Cavalcante, B. Hygromechanical Performance of Polyamide Specimens Made with Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2021, 13, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, R.D.; Tuck, C.J.; Hague, R.J.M. Laser Sintering of Polyamides and Other Polymers. Progress in Materials Science 2012, 57, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha Martynková, G.; Slíva, A.; Kratošová, G.; Čech Barabaszová, K.; Študentová, S.; Klusák, J.; Brožová, S.; Dokoupil, T.; Holešová, S. Polyamide 12 Materials Study of Morpho-Structural Changes during Laser Sintering of 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shujaat, S.; Shaheen, E.; Jacobs, R. Quality and Haptic Feedback of Three-Dimensionally Printed Models for Simulating Dental Implant Surgery. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2024, 131, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayaka, N.; Maclachlan, L.R.; Alexander, H.; Redmond, M.; Carluccio, D.; Jules-Vandi, L.; Novak, J.I. Evaluation of 3D Printed Burr Hole Simulation Models Using 8 Different Materials. World Neurosurgery 2023, 176, e651–e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.; Van Langeveld, M.C.; Donoso, L.A. Innovations in 3D Printing: A 3D Overview from Optics to Organs. Br J Ophthalmol 2014, 98, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.; Burnett, A.M.; Panos, J.G.; Paudel, P.; Keys, D.; Ansari, H.M.; Yu, M. 3-D Printed Spectacles: Potential, Challenges and the Future. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2020, 103, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwalek, P.; Ramsay, D.; Paradiso, J.A. Captivates: A Smart Eyeglass Platform for Across-Context Physiological Measurement. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2021, 5, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinkurt, E.; Ceylan, N.A.; Altunoglu, U.; Turgut, G.T. Manufacture of Custom-made Spectacles Using Three-dimensional Printing Technology. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2020, 103, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalle, M.; Belotti, V.; Frascio, M.; Razzoli, R. Development of a Wearable Device for the Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1038, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrin, A. A Circular Economy through 4.0 Technologies: The Case of Eyewear, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA, 2018.

- HP 3D Printed Glasses Are an Eye-Opener for the Optics Industry.

- Materialise and Safilo 3D-Print Spectacles.

- Anne et Valentin. Helium.

- Barletta, M.; Aversa, C.; Ayyoob, M.; Gisario, A.; Hamad, K.; Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H. Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS): Materials, Processing, and Industrial Applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2022, 132, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, J.; Yang, G.; Shi, F.; Yan, Q. Biodegradation of Poly(Butylene Succinate) in Compost. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2005, 97, 2273–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, G.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. Crystallization and Melting Properties of Poly(Butylene Succinate) Composites with Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes or Hydroxyapatite Nanorods. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2014, 131, app.40335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, S.; Anand, P.B.; K. , M.K.; Ammarullah, M.I. Synergistic Advances in Natural Fibre Composites: A Comprehensive Review of the Eco-Friendly Bio-Composite Development, Its Characterization and Diverse Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17594–17611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, L.G. Polymeric Biomaterials. Acta Materialia 2000, 48, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogje, M.; Mestry, S.; Mhaske, S.T. Biopolymers: A Comprehensive Review of Sustainability, Environmental Impact, and Lifecycle Analysis. Iran Polym J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniac, I.; Popescu, D.; Zapciu, A.; Antoniac, A.; Miculescu, F.; Moldovan, H. Magnesium Filled Polylactic Acid (PLA) Material for Filament Based 3D Printing. Materials 2019, 12, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Miao, S.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Mills, D.K.; Zhang, L.G. Bio-Based Polymers for 3D Printing of Bioscaffolds. Polymer Reviews 2018, 58, 668–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alionte, C.G.; Ungureanu, L.M.; Alexandru, T.M. Innovation Process for Optical Face Scanner Used to Customize 3D Printed Spectacles. Materials 2022, 15, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molero, E.; Fernández, J.J.; Rodríguez-Alabanda, O.; Guerrero-Vaca, G.; Romero, P.E. Use of Data Mining Techniques for the Prediction of Surface Roughness of Printed Parts in Polylactic Acid (PLA) by Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM): A Practical Application in Frame Glasses Manufacturing. Polymers 2020, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.M.; Asici, C. Analysis of Surface Roughness and Strain Durability of Eyeglasses Frames by the 3D Printing Technology. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 12214–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balart, R.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Fombuena, V.; Quiles-Carrillo, L.; Arrieta, M.P. Biopolymers from Natural Resources. Polymers 2021, 13, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.S.; Mahmood, A. Biopolymers: An Introduction and Biomedical Applications. Journal of Physical Chemistry and Functional Materials 2024, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grira, S.; Mozumder, M.S.; Mourad, A.-H.I.; Ramadan, M.; Khalifeh, H.A.; Alkhedher, M. 3D Bioprinting of Natural Materials and Their AI-Enhanced Printability: A Review. Bioprinting 2025, 46, e00385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, A.; Bonetti, L.; Piantanida, E.; De Nardo, L. Plasticizer Design Strategies Enabling Advanced Applications of Cellulose Acetate. European Polymer Journal 2023, 197, 112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, J.; Zubizarreta, J.; Geis, N.; Immonen, K.; Kangas, H.; Ruckdäschel, H. 3D Printed Cellulose-Based Filaments—Processing and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ravichandran, D.; Ramanathan, A.; Sobczak, M.T.; Sacco, A.F.; Patil, D.; Thummalapalli, S.V.; Pulido, T.V.; Lancaster, J.N.; et al. 3D-Printed Polymeric Biomaterials for Health Applications. Adv Healthcare Materials 2025, 14, 2402571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H.; Barletta, M.; Laheurte, P.; Langlois, V. Additive Manufacturing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Biopolymers: Materials, Printing Techniques, and Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 127, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, J.; Zubizarreta, J.; Geis, N.; Immonen, K.; Kangas, H.; Ruckdäschel, H. 3D Printed Cellulose-Based Filaments—Processing and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, J.N.; Pilania, G.; Marrone, B.L. Materials Designed to Degrade: Structure, Properties, Processing, and Performance Relationships in Polyhydroxyalkanoate Biopolymers. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, H.; McGreal, H.; Zarrin, H.; Behzadfar, E. Effects of Rheological Properties on 3D Printing of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) and Poly(Hydroxy Alkenoate) (PHA) Hybrid Materials. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 4034–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Achraf, W.; Abdelkarim, K.; Hamid, C.; Mohamed, El. Failure Analysis of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) Materials and Damage Modeling by Fracture. Int J Performability Eng 2019, 15, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imranuddin, S.; Singh, A.; Shiferaw, M.; Tadesse, Y. Energy-Efficient 3D-Printed Multi-Material Gripper with Integrated Smart Sensing and Actuation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 18th Dallas Circuits and Systems Conference (DCAS); IEEE: Arlington, TX, USA, April 11, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.R.; Mount, E.M.; Giles, H.F. Processing Recommendations for Various Resin Systems. In Extrusion; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 255–275 ISBN 978-1-4377-3481-2.

- Sastri, V.R. High-Temperature Engineering Thermoplastics. In Plastics in Medical Devices; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 173–213 ISBN 978-1-4557-3201-2.

- Https://Www.Curbellplastics.Com/Materials/Plastics/Ultem/?srsltid=AfmBOorVCgfsJj9p3CCW29wOaFwb7_pQAuVB0nTeV6yXVKZyY0uApsuZ.

- Https://Www.Addmangroup.Com/Ultem-Thermoplastic/.

- Http://Www.Neema3d.Com/High-Temperature/Pei-Ultem-1010.

- Bahrami, M.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.A. Comparative Characterization of Hot-Pressed Polyamide 11 and 12: Mechanical, Thermal and Durability Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, M.; Lavayen-Farfan, D.; Martínez, M.A.; Abenojar, J. Experimental and Numerical Studies of Polyamide 11 and 12 Surfaces Modified by Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Treatment. Surfaces and Interfaces 2022, 32, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parulekar, Y.; Mohanty, A.K. Biodegradable Toughened Polymers from Renewable Resources: Blends of Polyhydroxybutyrate with Epoxidized Natural Rubber and Maleated Polybutadiene. Green Chem. 2006, 8, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Ortega, H.; Llop, M.F.; Espinach, F.X.; Tarrés, Q.; Ardanuy, M.; Mutjé, P. Study of the Flexural Modulus of Lignocellulosic Fibers Reinforced Bio-Based Polyamide11 Green Composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2018, 152, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.J.; Salazar, A.; Rodríguez, J. Effect of Temperature on the Fracture Behavior of Polyamide 12 and Glass-Filled Polyamide 12 Processed by Selective Laser Sintering. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2018, 203, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Rodrigues, P.; Vargas, P.; Massano, A.; Oliveira, L.M.; Batista, C.; Cruz, V.; Mateus, A.; Mitchell, G.R.; Sobral, A.J.F.N.; et al. A Novel Fully Biobased Material Composite for Cosmetic Packaging Applications. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 26882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righetti, M.C.; Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Cinelli, P.; Gazzano, M. Temperature Dependence of the Rigid Amorphous Fraction of Poly(Butylene Succinate). RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 25731–25737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliotta, L.; Seggiani, M.; Lazzeri, A.; Gigante, V.; Cinelli, P. A Brief Review of Poly (Butylene Succinate) (PBS) and Its Main Copolymers: Synthesis, Blends, Composites, Biodegradability, and Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fátima Santos; Patrício Vargas; Anabela Massano; Beatriz Carvalho; Ana Fonseca; Geoffrey Mitchell; Artur Mateus; Telma Encarnação Biocomposite of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV), Wood Fibres and Additives: Physicochemical Properties and Processability through Different Techniques.

- Bi, X.; Huang, R. 3D Printing of Natural Fiber and Composites: A State-of-the-Art Review. Materials & Design 2022, 222, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Oleiwi, J.K.; Mohammed, A.M.; Jawad, A.J.M.; Osman, A.F.; Adam, T.; Betar, B.O.; Gopinath, S.C.B. A Review on the Advancement of Renewable Natural Fiber Hybrid Composites: Prospects, Challenges, and Industrial Applications. JRM 2024, 12, 1237–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, V.; Malagutti, L.; Mollica, F. FDM 3D Printing of Polymers Containing Natural Fillers: A Review of Their Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Correa, D.; Ueda, M.; Matsuzaki, R.; Castro, M. A Review of 3D and 4D Printing of Natural Fibre Biocomposites. Materials & Design 2020, 194, 108911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Mohammad Taha, M.; Mustapha, F.; Leman, Z. A Review of Natural Fiber-Based Filaments for 3D Printing: Filament Fabrication and Characterization. Materials 2023, 16, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Alliyankal Vijayakumar, A.; Jose, T.; George, S.C. A Comprehensive Review of Sustainability in Natural-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, M.; Saravanan, R.; T, S. Exploring Natural Plant Fiber Choices and Treatment Methods for Contemporary Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Results in Engineering 2024, 24, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Moon, J.-B.; Kim, G.-H.; Ha, C.-S. Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene/Natural Fiber Composites: Comparison of Wood Fiber and Cotton Fiber. Polymer Testing 2008, 27, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Mahendran, A.R.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Bliem, P.; Konnerth, J.; Müller, U.; Veigel, S. The Strength and Stiffness of Oriented Wood and Cellulose-Fibre Materials: A Review. Progress in Materials Science 2022, 125, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A Comprehensive Review of Natural Fibers and Their Composites: An Eco-Friendly Alternative to Conventional Materials. Results in Engineering 2023, 19, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenhorn, P.R.; Blankenhorn, B.D.; Silsbee, M.R.; DiCola, M. Effects of Fiber Surface Treatments on Mechanical Properties of Wood Fiber–Cement Composites. Cement and Concrete Research 2001, 31, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, W.; Szymanowski, K.; Nasiłowska, B.; Barlak, M.; Betlej, I.; Prokopiuk, A.; Borysiuk, P. 3D Printing Wood–PLA Composites: The Impact of Wood Particle Size. Polymers 2025, 17, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lei, W.; Yu, W. FDM 3D Printing and Properties of WF/PBAT/PLA Composites. Molecules 2024, 29, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehanich, J.L.; Blankenhorn, P.R.; Silsbee, M.R. Wood Fiber Surface Treatment Level Effects on Selected Mechanical Properties of Wood Fiber–Cement Composites. Cement and Concrete Research 2004, 34, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obućina, M.; Hajdarević, S.; Martinović, S.; Jusufagić, M. Properties and Application of Wood-Plasticcomposites Obtained by FDM 3D Printing. In New Technologies, Development and Application VII; Karabegovic, I., Kovačević, A., Mandzuka, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-66267-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jaróg, T.; Góra, M.; Góra, M.; Maroszek, M.; Hodor, K.; Hodor, K.; Hebda, M.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M. Biodegradable Meets Functional: Dual-Nozzle Printing of Eco-Conscious Parklets with Wood-Filled PLA. Materials 2025, 18, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvanjumrat, C.; Chansoda, K.; Chookaew, W. Additive Manufacturing Advancement through Large-Scale Screw-Extrusion 3D Printing for Precision Parawood Powder/PLA Furniture Production. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2024, 20, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, L. New Cork-Based Materials and Applications. Materials 2015, 8, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L.G.; Soares, E.; Oliveira, M. Biodegradability Assessment of Cork Polymer Composites for Sustainable Packaging Applications. Next Materials 2025, 8, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.P.; Sabino, M.A.; Fernandes, E.M.; Correlo, V.M.; Boesel, L.F.; Reis, R.L. Cork: Properties, Capabilities and Applications. International Materials Reviews 2005, 50, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H. The Rationale behind Cork Properties: A Review of Structure and Chemistry. BioResources 2015, 10, 6207–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ocaña, I.; Herrera, M.; Fernández-Delgado, N.; Molina, S.I. Potential Use of Residual Powder Generated in Cork Stopper Industry as Valuable Additive to Develop Biomass-Based Composites for Injection Molding. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães Da Silva, S.P.; Antunes, T.; Costa, M.E.V.; Oliveira, J.M. Cork-like Filaments for Additive Manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2020, 34, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; Balu, R.; Dekiwadia, C.; John, S.; Choudhury, N.R.; Dutta, N.K. Fused Filament Fabrication with Engineered Polyamide-12-Cork Composites with a Silane Coupling Agent as an Interaction Promoter. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 4110–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, M.A.; Bello, O.S.; Adedeji, A.O. Traditional and Medicinal Uses of Luffa Cylindrica: A Review.

- Department of Mechanical Engineering, G. Pulla Reddy Engineering College, Kurnool, A.P., INDIA – 518007; Krishnudu, D.M.; Sreeramulu, D.; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Aditya Institute of Technology and Management, Tekkali, A.P., INDIA - 532201; Reddy, P.V.; Department of Mechanical Engineering, G.Pulla Reddy Engineering College, Kurnool, A.P., INDIA – 518007 Synthesis and Characterization of PLA/Luffa Cylindrica Composite Films. IJIE 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I. Investigation of Mechanical Properties of Luffa Cylindrica Particulates Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composite. 2020.

- Martínez-Barrera, G.; Martínez-López, M.; Castro-López, C. Luffa Natural Sponge as Sustainable Reinforcement for Polyester Polymer Composites. Journal of Composite Materials 2025, 00219983251347853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Patra, S.; Parida, C.; Pradhan, C. Green Biodegradable Dielectric Material Made from PLA and Electron Beam Irradiated Luffa Cylindrica Fiber: Devices for a Sustainable Future. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 114078–114094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masmoudi, F.; Bessadok, A.; Dammak, M.; Jaziri, M.; Ammar, E. Biodegradable Packaging Materials Conception Based on Starch and Polylactic Acid (PLA) Reinforced with Cellulose. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2016, 23, 20904–20914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Mohanta, K.L.; Parida, C. Mechanical Properties of Bio-Fiber Composites Reinforced with Luffa Cylindrica Irradiated by Electron Beam. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2019, 33, 1950305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, S.; Munawar, M.A.; Khan, S. NATURAL FIBER-REINFORCED POLYMER COMPOSITES.

- Hiremath, V.S.; Reddy, D.M.; Reddy Mutra, R.; Sanjeev, A.; Dhilipkumar, T.; J, N. Thermal Degradation and Fire Retardant Behaviour of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymeric Composites- A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 30, 4053–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaliya, B.; Sunooj, K.V.; Lackner, M. Biopolymer Composites: A Review. International Journal of Biobased Plastics 2021, 3, 40–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyavihalli Girijappa, Y.G.; Mavinkere Rangappa, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Natural Fibers as Sustainable and Renewable Resource for Development of Eco-Friendly Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Padzil, F.N.B.M.; Lee, S.H.; Ainun, Z.M.A.; Abdullah, L.C. Potential for Natural Fiber Reinforcement in PLA Polymer Filaments for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohit, K.; Dixit, S. A Review - Future Aspect of Natural Fiber Reinforced Composite. Polymers from Renewable Resources 2016, 7, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumnate, C.; Soatthiyanon, N.; Makmoon, T.; Potiyaraj, P. Polylactic Acid/Kenaf Cellulose Biocomposite Filaments for Melt Extrusion Based-3D Printing. Cellulose 2021, 28, 8509–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, F.S.; Hameed Sultan, M.T.; Safri, S.N.A.; Jawaid, M.; Abu Talib, Abd. R.; Basri, A.A.; Md Shah, A.U. Physical, Thermal and Tensile Behaviour of 3D Printed Kenaf/PLA to Suggest Its Usability for Ankle–Foot Orthosis – a Preliminary Study. RPJ 2022, 28, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, J.P.; Manaia, A.T.; Rodriges, L. Industrial Hemp Fibers: An Overview. Fibers 2019, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, B.; Garofalo, E.; Di Maio, L.; Scarfato, P.; Incarnato, L. Investigation on the Use of PLA/Hemp Composites for the Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) 3D Printing.; Ischia, Italy, 2018; p. 020086.

- Skosana, S.J.; Khoathane, C.; Malwela, T.; Webo, W. Comparative Study on 3D Fused Deposition Modeling of PLA Composites Reinforced with Flax, PALF, and Hemp Fibres. Journal of Composite Materials 2025, 59, 2293–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.; Uysal, M.; Gumus, O.Y.; Tasdemir, C. 3D-Printed Biocomposites from Hemp Fibers Reinforced Polylactic Acid: Thermal, Morphology, and Mechanical Performance. BioRes 2024, 20, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placet, V. Characterization of the Thermo-Mechanical Behaviour of Hemp Fibres Intended for the Manufacturing of High Performance Composites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2009, 40, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.T.M.F.; Islam, M.Z.; Mahmud, M.S.; Sarker, M.E.; Islam, M.R. Hemp as a Potential Raw Material toward a Sustainable World: A Review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Hasan, Md.B.; Kodrić, M.; Motaleb, K.Z.M.A.; Karim, F.; Islam, Md.R. Mechanical Properties of Hemp Fiber-reinforced Thermoset and Thermoplastic Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. SPE Polymers 2025, 6, e10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Bueno, G.; Martín, M.R.; Rocha, J. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Hemp Fibers Influenced by Various Parameters. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseto, M. ; V.T. Rigueto, C.; D.C. Krein, D.; P. Balbé, N.; A. Massuda, L.; Dettmer, A. Biodegradable Polymers: Opportunities and Challenges. In Organic Polymers; Sand, A., Zaki, E., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2020 ISBN 978-1-78984-573-0.

- Ilyas, R.; Aisyah, H.; Nordin, A.; Ngadi, N.; Zuhri, M.; Asyraf, M.; Sapuan, S.; Zainudin, E.; Sharma, S.; Abral, H.; et al. Natural-Fiber-Reinforced Chitosan, Chitosan Blends and Their Nanocomposites for Various Advanced Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijoł, N.; Aguilar-Sánchez, A.; Mathew, A.P. 3D-Printable Biopolymer-Based Materials for Water Treatment: A Review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 430, 132964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, T.; Vincent, S.; Mohanty, S. Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid/Chitosan Composites by Fused Deposition Modeling. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansingh, B.B.; Binoj, J.S.; Tan, Z.Q.; Wong, W.L.E.; Amornsakchai, T.; Hassan, S.A.; Goh, K.L. Characterization and Performance of Additive Manufactured Novel Bio-Waste Polylactic Acid Eco-Friendly Composites. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 2306–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, G. The World of Inorganic Pigments. ChemTexts 2022, 8, 15–s40828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürses, A.; Açıkyıldız, M.; Güneş, K.; Gürses, M.S. Dyes and Pigments: Their Structure and Properties. In Dyes and Pigments; SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-33890-3. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 18451-1 Pigments, Dyestuffs and Extenders — Terminology — Part 1: General Terms; 2019.

- Horsth, D.F.L.; Primo, J.D.O.; Balaba, N.; Anaissi, F.J.; Bittencourt, C. Mixed Oxides with Corundum-Type Structure Obtained from Recycling Can Seals as Paint Pigments: Color Stability. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2023, 14, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Pandey, V.K.; Dash, K.K.; Zanwar, S.; Singh, R. Natural Bio-Colorant and Pigments: Sources and Applications in Food Processing. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023, 12, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Rodrigues, P.; Vargas, P.; Massano, A.; Oliveira, L.M.; Batista, C.; Cruz, V.; Mateus, A.; Mitchell, G.R.; Sobral, A.J.F.N.; et al. A Novel Fully Biobased Material Composite for Cosmetic Packaging Applications. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 26882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, M.; Ramakrishnan, E.; Deka, S.; Parasar, D.P. Bacteria as a Source of Biopigments and Their Potential Applications. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2024, 219, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, S.B.; Ghgare, S.N.; Swami, S.S.; Shinde, K.J.; Kalse, S.B.; Pardeshi, I.L. Natural Pigments from Plant Sources: A Review.

- Randhawa, K.S. Synthesis, Properties, and Environmental Impact of Hybrid Pigments. The Scientific World Journal 2024, 2024, 2773950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbe, E.O.; Uthman, T.O. A Review of History, Properties, Classification, Applications and Challenges of Natural and Synthetic Dyes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegay, F.; Ghannam, R.; Daniel, N.; Butt, H. 3D Printing Smart Eyeglass Frames: A Review. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, M.; Cardano, F.; Zanetti, M.; Viscardi, G.; Barolo, C.; Bordiga, S.; Magdassi, S.; Fin, A.; Roppolo, I. Functional Dyes in Polymeric 3D Printing: Applications and Perspectives. ACS Materials Lett. 2021, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseto, M. ; V.T. Rigueto, C.; D.C. Krein, D.; P. Balbé, N.; A. Massuda, L.; Dettmer, A. Biodegradable Polymers: Opportunities and Challenges. In Organic Polymers; Sand, A., Zaki, E., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2020 ISBN 978-1-78984-573-0.

- Lee, L.; Burnett, A.M.; Panos, J.G.; Paudel, P.; Keys, D.; Ansari, H.M.; Yu, M. 3-D Printed Spectacles: Potential, Challenges and the Future. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2020, 103, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rojas, B.; Hernández-Juárez, J.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Nutraceutical Properties of Phycocyanin. Journal of Functional Foods 2014, 11, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, N.T. Production of Phycocyanin—a Pigment with Applications in Biology, Biotechnology, Foods and Medicine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjali, A.; Clarot, I.; Chen, Z.; Marchioni, E.; Boudier, A. Physicochemical Degradation of Phycocyanin and Means to Improve Its Stability: A Short Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2022, 12, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pez Jaeschke, D.; Rocha Teixeira, I.; Damasceno Ferreira Marczak, L.; Domeneghini Mercali, G. Phycocyanin from Spirulina: A Review of Extraction Methods and Stability. Food Research International 2021, 143, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oninku, B.; Lomas, M.W.; Burr, G.; Aryee, A.N.A. Astaxanthin: An Overview of Its Sources, Extraction Methods, Encapsulation Techniques, Characterization, and Bioavailability. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2025, 21, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Félix-Valenzuela, L.; Goycoolea, F.M. Astaxanthin: A Review of Its Chemistry and Applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2006, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowiak, B.; Szulc, P. Astaxanthin for the Food Industry. Molecules 2021, 26, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Vázquez, A.; Jaimes-López, R.; Morales-Bautista, C.M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, S.; Gochi-Ponce, Y.; Estudillo-Wong, L.A. Catalytic Applications of Natural Iron Oxides and Hydroxides: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, G. Iron Oxide Pigments. Physical Sciences Reviews 2021, 6, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Barnard, A.S. Naturally Occurring Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Morphology, Surface Chemistry and Environmental Stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Huang, X.; Du, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, M.; Xu, G.; Geng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, X. Integration of Biological Synthesis & Chemical Catalysis: Bio-Based Plasticizer Trans-Aconitates. Green Carbon 2023, 1, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czogała, J.; Pankalla, E.; Turczyn, R. Recent Attempts in the Design of Efficient PVC Plasticizers with Reduced Migration. Materials 2021, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, J.; Bethel, A.; Galloway, T.; Hopkinson, P.; Morrissey, K.; Short, R.E.; Garside, R. Human Health Impacts of Exposure to Phthalate Plasticizers: An Overview of Reviews. Environment International 2022, 158, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Guo, J.-L.; Xue, J.; Bai, C.-L.; Guo, Y. Phthalate Metabolites: Characterization, Toxicities, Global Distribution, and Exposure Assessment. Environmental Pollution 2021, 291, 118106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; Da Silva, M.A.; Dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-Based Plasticizers and Biopolymer Films: A Review. European Polymer Journal 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.M.; Arezoumand, S.; Zare, L. Research Progress in Fully Biorenewable Tough Blends of Polylactide and Green Plasticizers. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 279, 135345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handbook of Plasticizers; Wypych, G. , Ed.; ChemTec Pub: Toronto, 2004; ISBN 978-1-895198-29-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Brazel, C. The Plasticizer Market: An Assessment of Traditional Plasticizers and Research Trends to Meet New Challenges. Progress in Polymer Science 2004, 29, 1223–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Park, W.H. Effect of Biodegradable Plasticizers on Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate). Polymer Testing 2004, 23, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosterhout, J.T.; Gilbert, M. Interactions between PVC and Binary or Ternary Blends of Plasticizers. Part I. PVC/Plasticizer Compatibility. Polymer 2003, 44, 8081–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.; Palkovits, R. Isosorbide as a Renewable Platform Chemical for Versatile Applications—Quo Vadis? ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussenne, C.; Delaunay, T.; Wiatz, V.; Wyart, H.; Suisse, I.; Sauthier, M. Synthesis of Isosorbide: An Overview of Challenging Reactions. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 5332–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-M.; Jung, J.; Gwon, H.-J.; Hwang, T.S. Synthesis and Properties of Isosorbide-Based Eco-Friendly Plasticizers for Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Hakkarainen, M. Oligomeric Isosorbide Esters as Alternative Renewable Resource Plasticizers for PVC. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2011, 119, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbecq, F.; Khodadadi, M.R.; Rodriguez Padron, D.; Varma, R.; Len, C. Isosorbide: Recent Advances in Catalytic Production. Molecular Catalysis 2020, 482, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinska, L.; Koning, C.E. Unsaturated, Biobased Polyesters and Their Cross-linking via Radical Copolymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 2885–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordover, B.A.J.; Duchateau, R.; Van Benthem, R.A.T.M.; Ming, W.; Koning, C.E. Enhancing the Functionality of Biobased Polyester Coating Resins through Modification with Citric Acid. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordover, B.A.J.; Van Staalduinen, V.G.; Duchateau, R.; Koning, C.E.; Van Benthem; Mak, M. ; Heise, A.; Frissen, A.E.; Van Haveren, J. Co- and Terpolyesters Based on Isosorbide and Succinic Acid for Coating Applications: Synthesis and Characterization. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 3406–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; East, A.J.; Hammond, W.B.; Zhang, Y.; Jaffe, M. Overview of Advances in Sugar-based Polymers. Polymers for Advanced Techs 2011, 22, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruellan, A.; Guinault, A.; Sollogoub, C.; Ducruet, V.; Domenek, S. Solubility Factors as Screening Tools of Biodegradable Toughening Agents of Polylactide. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2015, 132, app.42476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J. Isosorbide Dioctoate as a “Green” Plasticizer for Poly(Lactic Acid). Materials & Design 2016, 91, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Huang, S.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; et al. Intergenerational Metabolism-Disrupting Effects of Maternal Exposure to Plasticizer Acetyl Tributyl Citrate (ATBC). Environment International 2024, 191, 108967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Xia, H.; Tang, K.; Zhou, Y. Plasticizers Derived from Biomass Resources: A Short Review. Polymers 2018, 10, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.V.; Kumar, R.A.; Dav�, V.; Gross, R.A.; McCarthy, S.P. Citrate Esters as Plasticizers for Poly(Lactic Acid). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 66, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiza, M.; Benaniba, M.T.; Massardier-Nageotte, V. Plasticizing Effects of Citrate Esters on Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid). Journal of Polymer Engineering 2016, 36, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiza, M.; Benaniba, M.T.; Massardier-Nageotte, V. Plasticizing Effects of Citrate Esters on Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid). Journal of Polymer Engineering 2016, 36, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, F.M.; Gupta, R.K. Exploring the Potential of Bio-Plasticizers: Functions, Advantages, and Challenges in Polymer Science. J Polym Environ 2024, 32, 5499–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, Z.Y.; Samsudin, H.; Yhaya, M.F. Glycerol: Its Properties, Polymer Synthesis, and Applications in Starch Based Films. European Polymer Journal 2022, 175, 111377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, D.; Adhikari, B.; Adhikari, R.; Chaudhary, D.S. Comparative Study of Film Forming Behaviour of Low and High Amylose Starches Using Glycerol and Xylitol as Plasticizers. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.M.; Maria Martelli, S.; Canhadas Bertan, L.; Yamashita, F.; Innocentini Mei, L.H.; Collares Queiroz, F.P. Edible Films Made from Blends of Manioc Starch and Gelatin – Influence of Different Types of Plasticizer and Different Levels of Macromolecules on Their Properties. LWT 2012, 49, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.J.; Florido-Moreno, P.; Porras-Vázquez, J.M.; Tedeschi, G.; Athanassiou, A.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Guzman-Puyol, S. Transparent, Plasticized Cellulose-Glycerol Bioplastics for Food Packaging Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 132956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Yang, F.; Hao, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, H.; Dong, L. Thermal, Mechanical, and Rheological Properties of Plasticized Poly(L-lactic Acid). J of Applied Polymer Sci 2013, 127, 2832–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, G. A Natural Butter Glyceride as a Plasticizer for Improving Thermal, Mechanical, and Biodegradable Properties of Poly(Lactide Acid). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 263, 130366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revutskaya, N.; Polishchuk, E.; Kozyrev, I.; Fedulova, L.; Krylova, V.; Pchelkina, V.; Gustova, T.; Vasilevskaya, E.; Karabanov, S.; Kibitkina, A.; et al. Application of Natural Functional Additives for Improving Bioactivity and Structure of Biopolymer-Based Films for Food Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Wu, S.; Siddiqui, M.W. Incorporating Essential Oils or Compounds Derived Thereof into Edible Coatings: Effect on Quality and Shelf Life of Fresh/Fresh-Cut Produce. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 108, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.R.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Mauri, A.N.; Montero, M.P. Sunflower Protein Films Incorporated with Clove Essential Oil Have Potential Application for the Preservation of Fish Patties. Food Hydrocolloids 2013, 33, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A. Essential Oils as Additives in Biodegradable Films and Coatings for Active Food Packaging. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2016, 48, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Barkauskaite, S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Essential Oils as Additives in Active Food Packaging. Food Chemistry 2021, 343, 128403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turek, C.; Stintzing, F.C. Stability of Essential Oils: A Review. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2013, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, M.; Carniel, T.K.; Dalcanton, F.; Dos Anjos, R.S.; Gracher Riella, H.; De Araújo, P.H.H.; De Oliveira, D.; Antônio Fiori, M. Use of Encapsulated Natural Compounds as Antimicrobial Additives in Food Packaging: A Brief Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 81, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.M.; Asici, C. Analysis of Surface Roughness and Strain Durability of Eyeglasses Frames by the 3D Printing Technology. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 12214–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Composites Part B: Engineering 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. Diab; Mohamed El-Sakhawy THREE-DIMENSIONAL (3D) PRINTING BASED ON CELLULOSIC MATERIAL: A REVIEW. CELLULOSE CHEMISTRY AND TECHNOLOGY 2022, 56, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H.; Barletta, M.; Laheurte, P.; Langlois, V. Additive Manufacturing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Biopolymers: Materials, Printing Techniques, and Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 127, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; Aldhanhani, S.; Ali, M.; Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; Advanced Digital & Additive Manufacturing (ADAM) Center, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; Elkaffas, R.A.; Department of Aerospace Engineering, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; Butt, H.; Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; Advanced Digital & Additive Manufacturing (ADAM) Center, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, 127788, United Arab Emirates; et al. Advancing Structural Integrity: Graphene Nanocomposites via Vat Photopolymerization 3D Printing. ES Mater. Manuf. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y. Thermal Debinding for Stereolithography Additive Manufacturing of Advanced Ceramic Parts: A Comprehensive Review. Materials & Design 2024, 238, 112632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, M.; Ma, H.; Chapa-Villarreal, F.A.; Lobo, A.O.; Zhang, Y.S. Stereolithography Apparatus and Digital Light Processing-Based 3D Bioprinting for Tissue Fabrication. iScience 2023, 26, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Tan, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, J.; Liang, Z. Overview of 3D-Printed Silica Glass. Micromachines 2022, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alionte, C.G.; Ungureanu, L.M.; Alexandru, T.M. Innovation Process for Optical Face Scanner Used to Customize 3D Printed Spectacles. Materials 2022, 15, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robar, J.L.; Kammerzell, B.; Hulick, K.; Kaiser, P.; Young, C.; Verzwyvelt, V.; Cheng, X.; Shepherd, M.; Orbovic, R.; Fedullo, S.; et al. Novel Multi Jet Fusion 3D-printed Patient Immobilization for Radiation Therapy. J Applied Clin Med Phys 2022, 23, e13773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; Chen, A.; Wright, J.; Fitzhugh, A.; Hartman, A.; Zeng, J.; Gu, G.X. Effect of Build Parameters on the Mechanical Behavior of Polymeric Materials Produced by Multijet Fusion. Adv Eng Mater 2022, 24, 2100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, A.; Fitzhugh, A.; Jun, J.; Baker, M. Improving Aesthetics Through Post-Processing for 3D Printed Parts. ei 2019, 31, 480–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HP, HORIZONS OPTICAL CREATES CUSTOM EYEWEAR WITH HP MULTI JET FUSION. Available online: https://reinvent.hp.com/us-en-3dprint-cs-horizons-optical (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Eckhardt, L.; Layher, M.; Hopf, A.; Bliedtner, J.; May, M.; Lachmund, S.; Buttler, B. Laser Beam Polishing of PA12 Parts Manufactured by Powder Bed Fusion. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 10, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HP Multi Jet Fusion 3D Printing Technology. Available online: https://www.hp.com/gb-en/printers/3d-printers/products/multi-jet-technology.html (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Produkt-Kategorien PE 3D. Eyewear.

- read, M.G. 14 minutes Guide to 3D Printed Glasses and Eyewear. Available online: https://formlabs.com/eu/blog/3d-printed-glasses-frames-eyewear/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- 3D Printed Glasses. Tailor Made Glasses & Bespoke Glasses.

- MYKITA 3D Printed Designer Glasses Frames - MYKITA® MYLON. Available online: https://mykita.com/en/prescription-glasses/mylon (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- 3D-Printed Eyewear Portfolio | Inspiring Materials and Finishes. Available online: https://www.materialise.com/en/industries/3d-printed-eyewear/portfolio (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Buy 3D Printed Glasses with Prescription Lenses Online | VIU Eyewear. Available online: https://shopviu.com/en-de/glasses/material/3d?srsltid=AfmBOopmjkDVZAcuClzkJhpV6V8NXRXJD1A7zkBufwy7_mkWT5jq6Bqv (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- monday Find the Best 3D-Printed Eyewear of 2025 | Virtual Try-On at FAVR. blog.favrspecs.com 2020.

- Óculos Customizados - Sob Medida Para o Seu Rosto - Yoface. Available online: https://mkt.yoface.com.br/page/oculos-customizados/?_gl=1*tl9gxw*_gcl_au*MTIwNTk3Njg2MS4xNzUzNjk5MjEx*_ga*MjY3OTI4Mzc3LjE3NTM2OTkyMTE.*_ga_2TGDFFDJPD*czE3NTM2OTkyMTAkbzEkZzEkdDE3NTM2OTk3MDMkajU2JGwwJGgyNjczNzI2MTc. (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- www.netural.com, N.- Material: natural3D. Available online: https://www.silhouette-group.com/en/stories/natural3d (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- IGX. Available online: https://www.igreeneyewear.com/collection/IGX (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Veroflex: A Flexible Colorful 3D Printing Material. Available online: https://www.stratasys.com/en/materials/materials-catalog/polyjet-materials/veroflex/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Goetti-Dimension. Available online: https://gotti.ch/en/collections/goetti-dimension (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Klenze & Baum. Available online: https://klenzebaum.com/en (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Product. Available online: https://www.neubau-eyewear.com/materials (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- 20/20 EUROPE SPECIAL: 3D printed Eyewear - rolf. Available online: https://www.rolf-spectacles.com/20-20-europe-special-3d-printed-eyewear/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- 3D Printed Glasses - MANTI MANTI Is Made for Cool Kids. Available online: https://manti-manti.com/collections/3d-gedruckte-brillen (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Adidas SP0066 Sunglasses - Black | Free Shipping with adiClub | Adidas US. Available online: https://www.adidas.com/us/sp0066-sunglasses/GA4639.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- China Sunglasses, Optical Frame and Reading Glasses Manufacturer | Hala Optical. Available online: http://www.halaeyewear.com/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Plastic Injected Eyewear Production & Manufacturing | La Giardiniera Srl.

- Kaur, A.; Singh, S.; Bala, N.; Kumar Kansal, S. 3D Printed Biomaterials: From Fabrication Techniques to Clinical Applications: A Systematic Review. European Polymer Journal 2025, 227, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

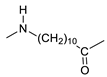

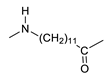

| Polyamide | Structure (Repeating Unit) | Melting point (ºC) | Density (g/cm3) | Young’s strength (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Glass transition (ºC) |

| PA 6 |  |

215-220 | 1.14 | 700-5000 | 30-66 | 40-50 |

| PA 6-6 |  |

261-263.5 | 1.06-1.08 | 939-1170 | 36.1-45.1 | 55 |

| PA 11 |  |

185 | 1.05 | 350-1330 | 25-41 | 45 |

| PA 12 |  |

178-180 | 1.01 | 350-1350 | 30-70 | 40-50 |

| Source | Material |

Tg (°C) |

Tm (°C) |

MFR (g/10 min) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Tensile Modulus (MPa) |

Elongation Break (%) |

Flexural Strength (MPa) |

Flexural Modulus (GPa) |

Izod Impact Strength (J/cm) |

Ref. | |

| Fossil | ABS | 100-110 | 221 to 240 | 20 | 43.8 | 847.55 to 991.61 | 7.2 | 70.608 | 2.354 | 2.648 | [78,79,80] | |

| PEI | 215 | 217 to 225 | 11 | 115 | 90 to 130 | 60-80 | 22 | 3.5 | 25 to 60 | [81,82,83,84] | ||

| PA 11 | 40 to 45 | 185 to 193 | - | 25 to 41 | 350 to 1330 | 4 | 0.074 ± 0.012 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | - | [25,85,86,87,88] | ||

| PA 12 | 40 to 55 | 178 to 180 | - | 30 to 70 | 350 to 1350 | 200 | 47 to 49 | 1.146 to 1.687 | - | [25,85,86,89] | ||

| Bio-Based | Matrices | PLA | 50-65 | 153-180 | 42.7 ± 2.9 | 51.9 ± 0.69 | 804.9 ± 3.33 | 30 to 240 | 0.170 to 159 | 0.167 to 13.8 | 0.105 to 8.54 | [62,90] |

| PBS | -40 to 1-10 | 90-120 | 326.3-387 | [91,92] | ||||||||

| PHB | - | 140 to 180 | 17 to 20 | 25 to 40 | 3500 | 5 to 8 | 18 | 16 | 23 ± 1.53 | [22,87] | ||

| PHA | -30 to 10 | 70 to 170 | - | 18 to 24 | 700 to 1800 | 3 to 25 | 40 | 2 | 0.260 | [22] | ||

| PHBV | 60 | 173.9 | 17.4 ± 1.4 | 30.58 ± 0.92 | 823.22 ± 5.79 | 4.53 ± 0.02 | - | - | - | [93] | ||

| CA | - | 115 | - | 10 | 460 | 13 to 15 | 27 to 72 | 0.08 to 2.62 | 0.480 to 4.50 | [22] | ||

| Composite/ Blends | PHBV/Wood | - | 173.5 | 42.0 ± 2.1 | 27.31 ± 0.67 | 179.13 ± 16.74 | 3.59 ± 0.10 | - | - | - | [93] | |

| PHBV/Wood/CaCO3 | - | 173.8 | 51.0 ± 2.8 | 17.21 ± 2.29 | 928.5 ± 30.86 | 1.75 ± 0.21 | - | - | - | [93] | ||

| PHBV/Wood/CaCO3/Ad1 | - | 173.4 | 55.6 ± 2.7 | 23.53 ± 1.35 | 707.50 ± 55.9 | 2.32 ± 0.06 | - | - | - | [93] | ||

| PHBV/Wood/CaCO3/Ad2 | - | 175.1 | 44.1 ± 1.4 | 26.62 ± 2.05 | 132.4 ± 14.88 | 3.69 ± 0.27 | - | - | - | [93] | ||

| PHBV/Wood/Ta.Fe/CaCO3 | - | 174.4 | 44.6 ± 0.9 | 29.28 ± 1.12 | 173.48 ± 9.54 | 3.78 ± 0.14 | - | - | - | [93] | ||

| PHBV/PLA | 59 | 174 | 30.0 ± 1.7 | 32.17 ± 0.86 | 804.23 ± 10.90 | - | - | - | - | [90] | ||

| PHBV/PLA/CS | 58 | 173 | - | 25.40 ± 0.91 | 871.23 ± 3.60 | - | - | - | - | [90] | ||

| PHBV/PLA/CS/OE/Pgm/ATBC | 54 | 172 | - | 19.03 ± 0.92 | 713.96 ± 30.20 | - | - | - | - | [90] | ||

| Pigments | Dyes | |

| Classification | Inorganic; Organic | (Organic) Natural; Synthetic |

| Solubility in the medium | No* | Yes |

| Affinity to the substrate | Not needed- crystal or powder particles dispersed on the medium; Unaffected chemically or physically by the vehicle or substrate where they are incorporated. | Yes – Organic molecules dissolved in a medium. During the application process, the crystal structure is (temporarily) destroyed by absorption, solution, and mechanical retention or by ionic or covalent bonds. |

| Processability | Difficult | Easy |

| Stability of colour |

Inorganic pigments: Highly durable, Poor colour strength; Poor brilliance; Heat stable; Solvent resistant. Organic pigments: Less Stable; Prone to degradation (after UV and atmospheric exposure). |

Brighter colour; Good colour strength; Less light stable (UV radiation); Less permanent/ Poor durability; Sensitivity to heat; Sensitivity to solvents |

| Change in colour | By scattering of the light and/or selective absorption. | Impart colour by selective absorption of light. |

| Coloristic properties | Defined by their chemical structure, by the physical characteristics of their particles (shape, size, distribution, concentration, etc.) and by the medium (absorption, refractive index). | Defined by their chemical structure (electronic properties of the chromophore molecule). |

| Examples |

Inorganic pigments: salt and oxides (Cr and Fe oxides); Organic pigments: Phycocyanin*, Astaxanthin* |

Synthetic dyes: Azo, Coumarin and Perylene dyes. Natural dyes: Indigo, Turmeric, beetroot |

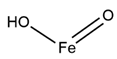

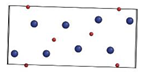

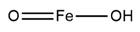

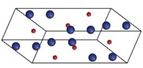

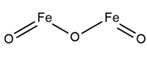

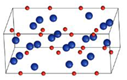

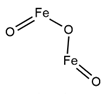

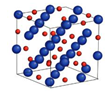

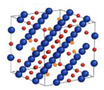

| Iron Oxide pigment | Chemical structure – 2D | Chemical structure- 3D | Colours | Characteristics |

| Goethite α-FeOOH |

|

|

|

Particles show an acicular shape; Colour changes with increasing particle size; Colour from green-yellow to brown- yellow |

| Lepidocrocite γ-FeOOH |

|

|

|

Particles have a boehmite structure; Magnetic pigment Colour changes with increased particle size; Colour from yellow to orange |

| Hematite α-Fe2O3 |

|

|

|

Corundum structure; Shape can be spherical, acicular, or cubical; Colour changes with increasing particle size Colour from light red to dark violet |

| Maghemite γ-Fe2O3 |

|

|

|

Spinel superlattice structure; Ferromagnetic Colour brown |

| Magnetite Fe3O4 |

|

|

|

Inverse spinel structure; Ferromagnetic Colour Black |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).