1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Cybersecurity is now a central part of global digital transformation, supporting services such as online banking, e-commerce, education, and social communication. As more people and organizations move to digital platforms, cyber threats have grown in both scale and complexity. Studies show that human error is the main cause of many security breaches, with about 68% linked to user behavior such as weak passwords, falling for phishing attempts, and not installing security updates [

1,

2,

3].

Although technological protections like encryption, firewalls, and intrusion detection systems are important, the human factor remains the weakest link [

4]. For this reason, cybersecurity awareness and knowledge are considered the first line of defense. People who have prior knowledge are usually better able to spot suspicious activities, use stronger authentication methods, and practice safer online habits [

5]. However, knowledge alone is not always enough. Whether people follow security advice often depends on other factors, such as how risky they think an activity is, how convenient the security measure feels, and their own confidence in handling technology [

6,

7].

In Africa, the rapid growth of digital services especially mobile-based financial transactions has made user awareness even more important in reducing cyber risks. The World Bank (2024) reports that in several African countries, the number of mobile money accounts is now higher than traditional bank accounts, which also increases the risk of digital fraud [

8]. ENISA (2024) similarly stresses that awareness programs need to be adapted to local cultural and technological conditions, especially in developing regions where formal cybersecurity systems are still limited [

9].

Cybersecurity today is not only a technical issue but also a social one, where trust, privacy, and digital literacy play a major role in building safer digital environments. In countries with fewer resources, the lack of structured education and support makes people more vulnerable to cybercrime. For example, widespread use of mobile phones combined with low levels of cybersecurity knowledge creates easy opportunities for attackers to target financial services and personal data. This shows that improving awareness is not just a technical need but also an important part of development.

Global trends such as remote work, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are also expanding the ways attackers can cause harm. Users without training are more likely to fall victim to phishing, ransomware, and other cybercrimes. Therefore, awareness efforts must grow alongside new technologies, helping both individuals and organizations to protect themselves [

3,

4].

In summary, while technology provides strong protection, the human factor remains critical. This makes cybersecurity awareness essential at all levels through schools, workplaces, and national policies especially in developing regions where digital services are spreading quickly.

1.2. Problem Statement

Although studies in developed economies demonstrate a strong link between prior cybersecurity knowledge and secure online behaviors [

4,

6,

7], this relationship remains unexamined in Somaliland, where digital adoption is accelerating rapidly. The proliferation of mobile money services, online marketplaces, and digital communications has improved financial inclusion and connectivity, but it has also introduced significant cybersecurity risks. Unlike developed nations, which benefit from structured awareness programs and institutionalized cybersecurity policies, Somaliland lacks comprehensive user-focused strategies for cyber safety.

The absence of empirical research creates a critical knowledge gap:

Do users with prior cybersecurity knowledge in Somaliland engage in safer online practices such as enabling two-factor authentication, creating strong passwords, avoiding phishing scams, and updating software regularly? Understanding this relationship is essential, as cybercriminals increasingly target regions with weak regulatory enforcement and low user awareness [

10]. Without context-specific evidence, policymakers and service providers cannot design effective interventions to reduce human-related vulnerabilities. This study aims to address this gap by providing data-driven insights into the prevalence of prior cybersecurity knowledge among Somaliland’s internet users and its impact on their security behaviors.

1.3. Objectives of the Study

The primary objective of this study is to examine the role of prior cybersecurity knowledge in promoting safe online practices among internet users in Somaliland. Specifically, the study seeks to:

Assess the prevalence of prior cybersecurity knowledge among internet users in Somaliland.

Identify demographic and behavioral factors (age, gender, education level, occupation, and region) associated with prior cybersecurity knowledge.

Examine the relationship between prior cybersecurity knowledge and safe online practices, including two-factor authentication (2FA) usage, password hygiene, phishing response behavior, and awareness of software updates.

1.4. Research Questions

To achieve these objectives, the study addresses the following questions:

What is the prevalence of prior cybersecurity knowledge among internet users in Somaliland?

Which demographic and behavioral factors influence the likelihood of having prior cybersecurity knowledge?

How does prior cybersecurity knowledge impact the adoption of safe online practices such as 2FA usage, strong password habits, phishing avoidance, and regular software updates?

1.5. Significance of the Study

This research provides the first empirical evidence on the relationship between prior cybersecurity knowledge and online safety practices in Somaliland. Findings will inform policy development, guiding stakeholders such as the Ministry of Communications, ICT regulators, and financial service providers in designing targeted awareness campaigns. Furthermore, the results will contribute to the academic discourse on human-centric cybersecurity in emerging economies, where digital adoption outpaces awareness and regulation. The study will also serve as a reference for future initiatives aimed at strengthening cyber resilience in regions with similar socio-economic contexts.

1.6. Scope and Limitations

The study focuses on internet users in Somaliland, using a sample of 388 respondents drawn from diverse demographic groups. Variables include prior cybersecurity knowledge, demographic factors (age, gender, education), and behavioral indicators such as 2FA use, password practices, and phishing response. The study does not cover institutional cybersecurity policies or technical infrastructure. Limitations include potential self-report bias in survey responses and the cross-sectional nature of the data, which restricts causal inference.

2. Literature Review

Human Factors and Awareness

Cybersecurity breaches are increasingly attributed to human error rather than purely technical flaws. Recent reports confirm that over two-thirds of data breaches involve user-related actions, such as poor password management, falling victim to phishing attacks, and neglecting software updates [

1,

2]. A 2024 systematic review emphasizes that well-structured awareness programs significantly improve compliance with security guidelines, yet the outcomes depend heavily on users’ baseline knowledge and demographic characteristics [

3]. ENISA (2024) further stresses that cybersecurity awareness must adopt a human-centric approach, where communication strategies focus on risk perception, usability, and personal relevance rather than technical jargon [

2].

Knowledge and Behavior Mechanisms

Possessing cybersecurity knowledge does not automatically guarantee secure practices. Studies have shown that knowledge influences behavior through psychological constructs such as self-efficacy, motivation, and perceived control [

6,

8]. Research grounded in behavioral theories like Protection Motivation Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior demonstrates that a combination of knowledge and motivation predicts adherence to cybersecurity measures more effectively than awareness alone [

6,

8].

Phishing Literacy and Training Effectiveness

Phishing remains one of the most prevalent cyber threats globally. Experimental studies in 2024 revealed that individuals with higher phishing knowledge and detection confidence are significantly less susceptible to phishing attacks [

4]. Longitudinal evidence also shows that practical training interventions, such as simulated phishing exercises, yield stronger behavioral outcomes compared to passive awareness campaigns [

3]. However, security fatigue and information overload can undermine the effectiveness of such programs, indicating a need for concise, targeted, and ongoing interventions [

9,

14,

15].

Passwords and Basic Cyber Hygiene

Despite years of awareness campaigns, weak password practices remain widespread. A global study in 2022 found that password reuse and poor complexity standards are still common, largely due to convenience and cognitive load [

9]. Research suggests that even when users understand the importance of strong passwords, behavioral habits and perceived effort often outweigh knowledge [

10]. This highlights a persistent gap between awareness and actual security practices.

Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) Adoption

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is widely acknowledged as a baseline measure for account protection. Nevertheless, adoption rates remain low, particularly in low-resource settings, due to barriers such as lack of awareness, usability challenges, and perceived complexity [

7,

11]. Recent systematic reviews confirm that prior familiarity with security tools strongly predicts the adoption of advanced authentication methods like 2FA and biometrics [

12]. This demonstrates that prior cybersecurity knowledge not only influences basic practices but also facilitates the uptake of more advanced security solutions.

Global evidence underscores the pivotal role of prior cybersecurity knowledge in shaping secure online practices, both directly (enabling behaviors like 2FA activation) and indirectly (enhancing self-efficacy and risk perception). However, no empirical research has examined this relationship in Somaliland, leaving a critical knowledge gap for context-specific interventions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

This research employed a cross-sectional quantitative design to investigate the relationship between prior cybersecurity knowledge and safe online practices among internet users in Somaliland. A survey-based approach was used to collect primary data from a sample of individuals who regularly use digital services, including mobile money, social media, and online platforms.

3.2. Study Area and Population

The study was conducted in Somaliland, a region experiencing rapid digital adoption primarily driven by mobile-based financial transactions and internet connectivity expansion. The target population consisted of adult internet users (aged 18 years and above) residing in major urban centers such as Hargeisa, Burco, Berbera, and Borama.

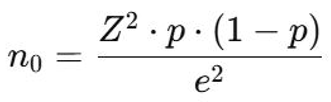

3.3. Sampling and Sample Size

A non-probability convenience sampling technique was adopted to recruit participants through online forms and physical outreach. A total of 388 valid responses were obtained and included in the analysis. The sample size was considered adequate based on Cochran’s formula for large populations and similar studies in cybersecurity awareness [

3,

4].

Figure 1.

Cochran’s Sample Size [

25].

Figure 1.

Cochran’s Sample Size [

25].

3.4. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire developed in English and Somali for clarity. The survey included sections on:

Demographics: Age, gender, education level, occupation, and region.

Cybersecurity Knowledge: A binary question (“Do you have prior cybersecurity knowledge?” Yes/No).

Behavioral Indicators: Use of two-factor authentication (2FA), password hygiene, phishing response behavior, and awareness of software updates.

Responses were gathered both online (Google Forms) and offline (paper-based forms) to maximize coverage.

3.5. Variables and Measurements

The primary independent variable in this study was Prior Cybersecurity Knowledge, operationalized as a dichotomous variable with two categories: Yes = 1 (participants who reported having prior cybersecurity knowledge) and No = 0 (participants with no prior knowledge).

The dependent variables were selected to measure various aspects of safe online practices. Each was operationalized as follows:

Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) Usage: Measured as a binary variable (Yes/No) based on whether participants reported enabling 2FA on at least one of their online accounts.

Password Hygiene: Categorized into Strong vs. Weak password practices. Strong password practices included the use of long, unique, and complex passwords, as well as the use of password managers. Weak practices included reusing passwords or using simple, easily guessable combinations.

Phishing Response Behavior: Assessed by participants’ self-reported ability to recognize and avoid clicking on suspicious or phishing links, measured as Correct Identification vs. Incorrect/No Identification.

Software Update Awareness: Measured based on the frequency of software updates (Regular Updates vs. Infrequent or Never), including operating systems, browsers, and antivirus tools.

3.6. Data Analysis Plan

Data were analyzed using SPSS v26. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, and mean values) were used to summarize demographic characteristics and prevalence of prior knowledge. Chi-square tests were applied to assess associations between prior knowledge and categorical variables (e.g., 2FA use, password strength). To further examine the predictive relationship between prior knowledge and safe practices, binary logistic regression was conducted, adjusting for demographic factors. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents. No personally identifiable information was collected. The study adhered to ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report in 1979 and complied with institutional review standards. Data were anonymized and stored securely to ensure confidentiality.

4. Results

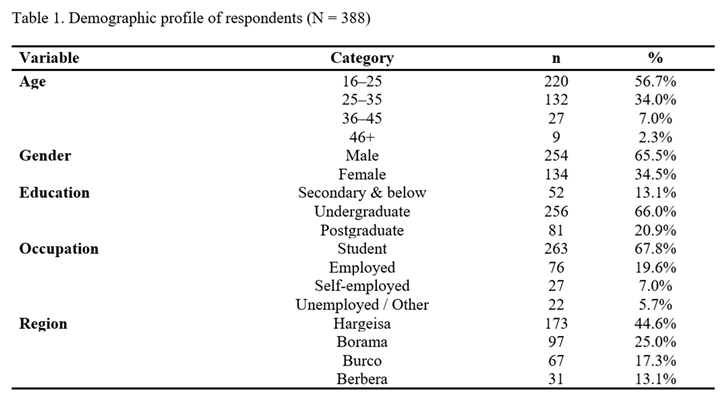

4.1. Sample Characteristics

Key observations:

The sample is youth-dominated, with 56.7% aged 16–25.

Males (65.5%) outnumber females (34.5%).

Two-thirds of respondents are university students.

Almost half of the sample came from Hargeisa (44.6%).

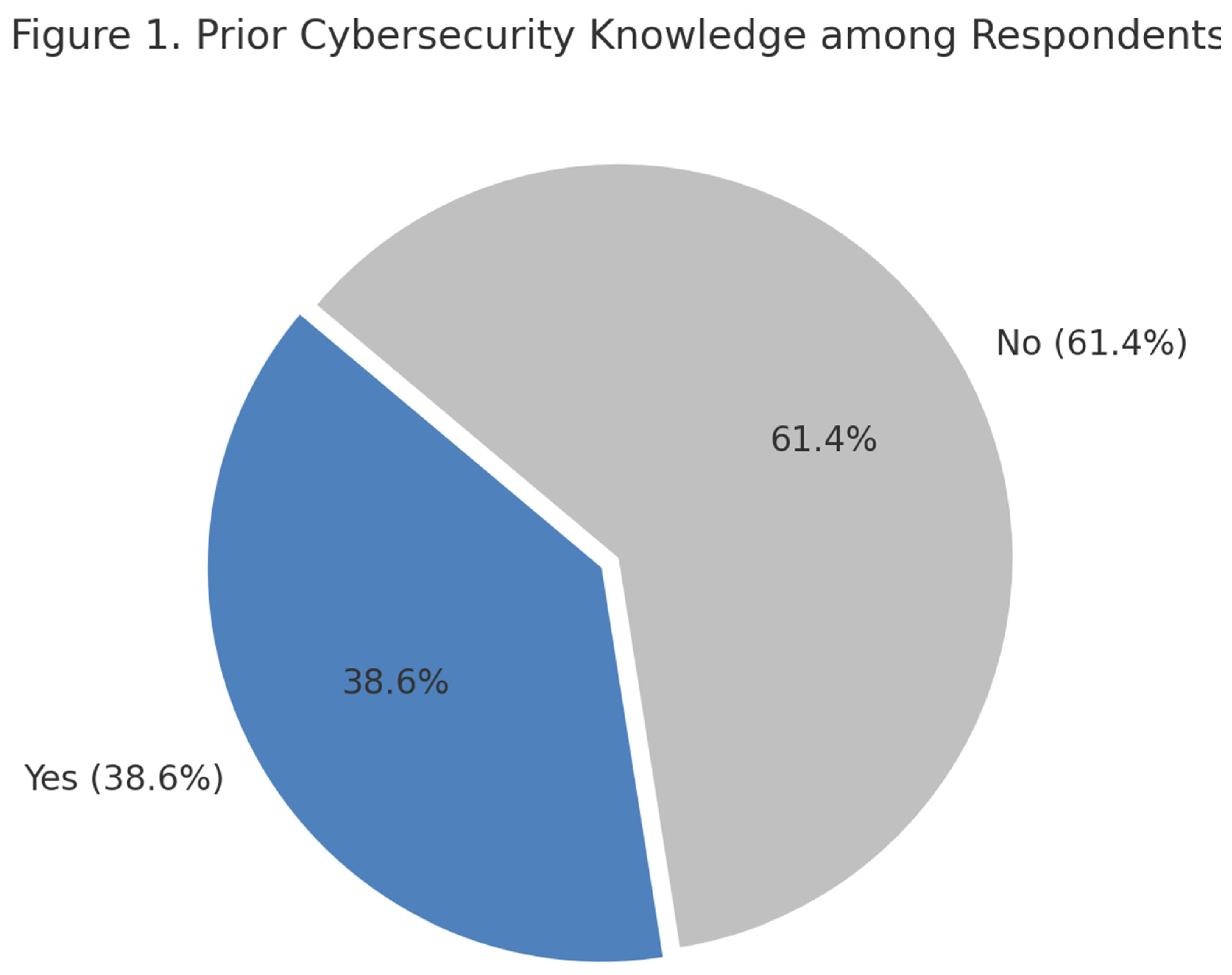

4.2. Prior Cybersecurity Knowledge

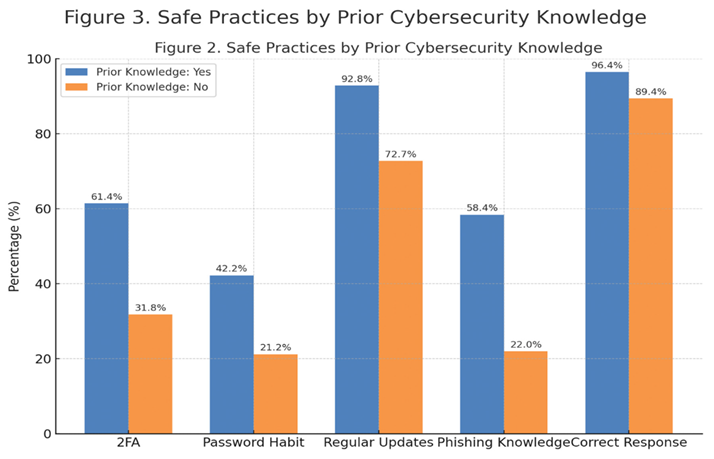

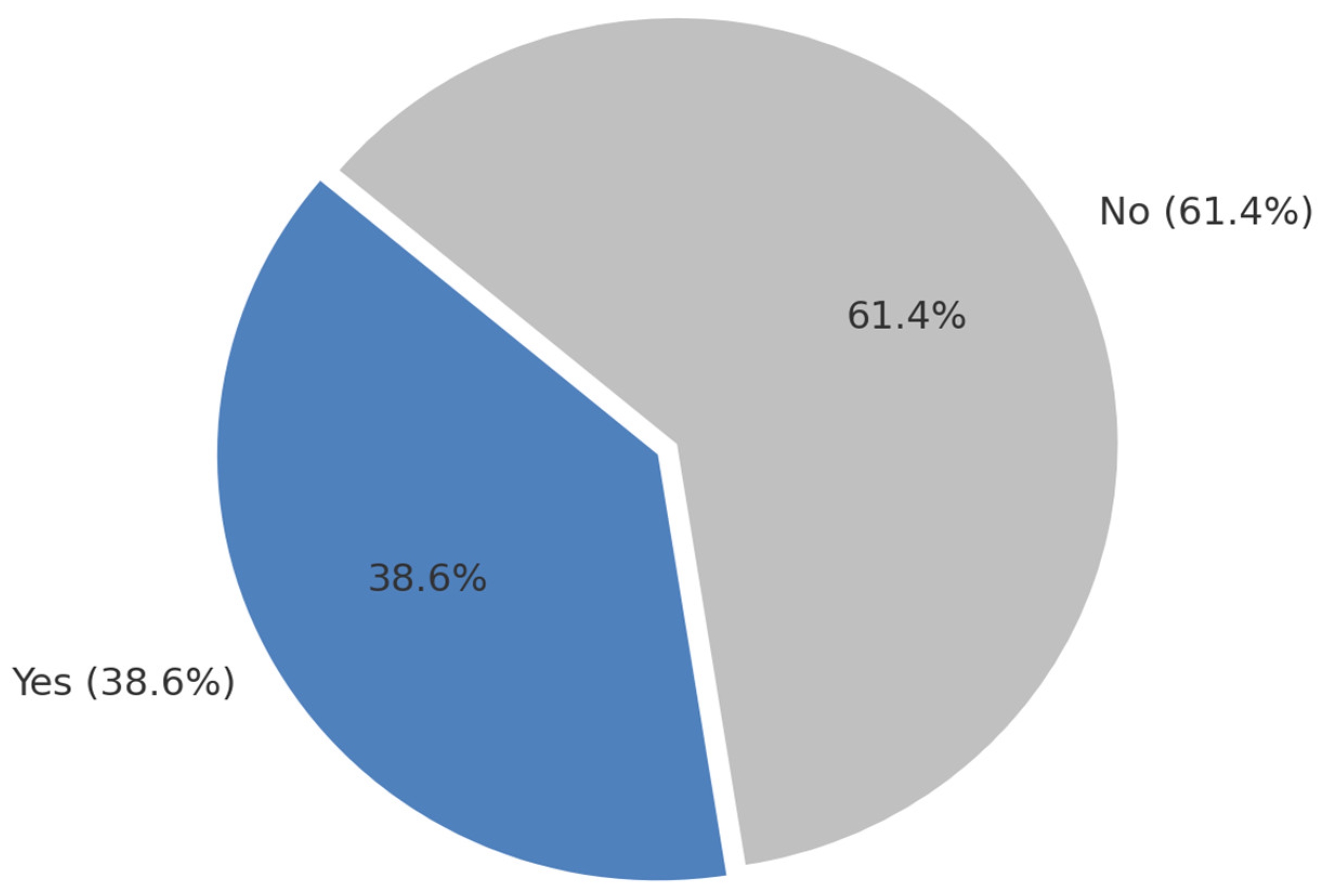

Figure 2.

Prior knowledge among respondents. This shows that a majority of respondents had no prior cybersecurity knowledge.

Figure 2.

Prior knowledge among respondents. This shows that a majority of respondents had no prior cybersecurity knowledge.

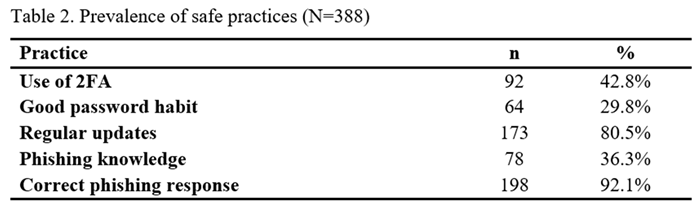

4.3. Safe Online Practices

Key findings:

A very high proportion regularly update their software/antivirus (80.5%).

Almost all respondents (92.1%) reported they would ignore a suspicious “$500 prize” email.

However, only 42.8% use two-factor authentication (2FA), and less than one-third (29.8%) practice good password hygiene.

4.4. Prior Knowledge vs. Safe Practices

This figure indicates that respondents with prior cybersecurity knowledge consistently show higher adoption of safe practices such as 2FA, good password habits, regular updates, and phishing awareness compared to those without knowledge, confirming a strong positive impact of awareness on secure behavior.

5. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between prior cybersecurity knowledge and safe online practices among internet users in Somaliland. The main findings indicate that respondents with prior knowledge were significantly more likely to adopt protective behaviors such as two-factor authentication (2FA), strong password habits, regular software updates, and appropriate phishing responses. In contrast, respondents without prior knowledge demonstrated lower security engagement across all behavioral indicators. These results confirm that cybersecurity awareness remains a critical factor shaping digital safety in emerging economies [

1,

2]. The positive association between prior knowledge and security behaviors suggests that awareness initiatives can meaningfully improve digital safety practices. For instance, 2FA adoption remained low (

42.8%) despite its proven effectiveness in preventing account breaches [

7,

11]. Our findings align with previous studies indicating that lack of awareness, usability barriers, and low perceived risk hinder 2FA uptake [

12,

13]. By contrast, password hygiene was adopted by only

29.8% of respondents, supporting earlier evidence that knowledge alone does not always translate into behavior unless combined with motivation and self-efficacy [

6,

14,

16]. The strong phishing response rate (

92.1%) contrasts with earlier studies in similar contexts, where susceptibility to phishing remained high due to low literacy levels and limited exposure to training [

3,

15]. The higher detection rate observed here may reflect informal awareness gained through social media, banking campaigns, or peer networks rather than structured training programs. Furthermore, the widespread practice of regular software updates (

80.5%) diverges from patterns reported in other developing regions, where update compliance is typically low [

8,

17]. Automated update processes in modern mobile devices may explain this difference [

18]. These findings carry several implications for policymakers, service providers, and educators in Somaliland. First, targeted awareness campaigns focusing on practical skills such as enabling

2FA,

creating strong passwords, and

recognizing phishing attempts could significantly reduce human related cybersecurity risks. Second, integrating behavioral theories like Protection Motivation Theory may enhance the effectiveness of such campaigns by addressing motivational and psychological factors influencing user compliance [

6].

Finally, the results highlight the importance of tailoring cybersecurity programs to local digital contexts rather than relying on generic global awareness materials [

2,

10]. Also, this study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias or inaccurate recall. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships between knowledge and behavior. The sample was also urban centered, potentially limiting the generalizability of results to rural populations with lower internet penetration. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to track behavioral changes over time following awareness interventions. Qualitative approaches, such as interviews or focus groups, could also explore cultural, psychological, and infrastructural factors influencing cybersecurity practices. Comparative studies across multiple African countries would further clarify whether the patterns observed here are unique to Somaliland or reflect broader regional trends.

This study shows that knowing about cybersecurity helps people in Somaliland stay safe online. It points out where people are doing well, like noticing phishing and updating software, and where they need improvement, like using two-factor authentication and keeping passwords strong. These results give useful ideas for policymakers, teachers, and service providers who want to make the internet safer in developing countries.

6. Conclusion

This study provides the first empirical examination of the role of prior cybersecurity knowledge in promoting safe online practices among internet users in Somaliland. The findings clearly demonstrate that prior knowledge significantly influences user behavior, with participants who possess such knowledge showing higher adoption of protective measures, including two-factor authentication, strong password practices, regular software updates, and appropriate responses to phishing attempts. These results confirm that awareness is not only a foundational component of cybersecurity but also a practical enabler of behavior that reduces exposure to online risks [

1,

2,

3].

The study further highlights the demographic and behavioral determinants of cybersecurity knowledge. Higher education levels and frequent internet use were strongly associated with greater awareness, suggesting that access to information and educational opportunities enhance digital literacy and readiness to adopt security measures. Conversely, gaps in password hygiene and 2FA adoption indicate that knowledge alone may not suffice; behavioral, motivational, and contextual factors play a critical role in translating awareness into effective security practices [

6,

14,

16].

The implications of these findings are multifaceted. From a policy perspective, targeted awareness programs focusing on practical skills such as enabling 2FA, recognizing phishing attempts, and maintaining strong password habits can substantially reduce human related vulnerabilities in Somaliland’s digital ecosystem. Educational institutions, financial service providers, and ICT regulators should collaborate to integrate cybersecurity modules into curricula and training initiatives, particularly for youth who constitute the majority of internet users. Moreover, interventions grounded in behavioral theories, such as Protection Motivation Theory or the Theory of Planned Behavior, can enhance the effectiveness of awareness campaigns by addressing motivational and psychological barriers to compliance [

6,

8].

Finally, this study emphasizes the importance of context-specific strategies in emerging digital economies. While automated update systems and informal social learning contributed to high compliance in certain areas, other behaviors lag behind, underscoring the need for locally tailored programs that reflect cultural norms, technological access, and user habits. By bridging the knowledge–behavior gap, Somaliland can strengthen its human-centric cybersecurity resilience, reduce susceptibility to cyber threats, and support safe and secure digital adoption for its population. Future research should expand to rural areas, employ longitudinal designs, and test the effectiveness of targeted interventions to ensure sustainable improvements in online safety [

19,

21].

In conclusion, prior cybersecurity knowledge is a critical determinant of safe online practices, with the potential to transform digital behavior when combined with targeted, context-aware interventions. Strengthening awareness, education, and practical skills among internet users will not only mitigate individual risk but also contribute to a more secure and resilient digital ecosystem in Somaliland and similar emerging economies.

7. Recommendation for Future Research

Practical Recommendations (User-Level)

Users should enable two-factor authentication, maintain strong and unique passwords, regularly update their devices and software, and exercise caution when encountering suspicious emails or links. Awareness campaigns should be strengthened to educate the general public on practical cybersecurity skills, helping individuals adopt safe online practices in their daily digital activities. Universities and educational institutions should integrate cybersecurity courses into their curricula, providing hands-on knowledge that prepares students to navigate online environments securely.

Policy and Implementation Recommendations

Policymakers and service providers should develop context specific guidance and initiatives tailored to local needs. Government-led awareness campaigns should emphasize practical skills, while banks, mobile money operators, and online platforms should embed security guidance and alerts into their services. Extending outreach programs to rural areas is essential to ensure equitable access to cybersecurity knowledge, reducing the urban rural digital divide. Monitoring and evaluation mechanisms should be implemented to assess program effectiveness and refine strategies over time.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine the long-term impact of awareness programs on user behavior. Qualitative approaches, such as interviews and focus groups, can provide deeper insights into cultural, psychological, and infrastructural factors that influence cybersecurity practices. Comparative studies across multiple regions or countries would help identify broader trends and context specific challenges. Experimental research testing targeted interventions such as simulated phishing exercises, password management training, or hands-on cybersecurity courses can provide evidence on the strategies most effective in promoting safe online behaviors.

Author Contributions

Shuaib Jama Hassan conceptualized the study, designed the survey, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. The author has read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, and participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all participants for their time and contribution to this study. Appreciation is also extended to colleagues who provided feedback during the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Verizon, “2024 Data Breach Investigations Report,” May 2024. Available: https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/2024-data-breach-investigations-report.pdf.

- ENISA, “Reframing Cybersecurity Awareness Raising: Human-Centric Strategies,” Nov. 2024. Available: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/reframing-cybersecurity-awareness-raising.

- J. Prümmer, T. van Steen, and B. van den Berg, “A systematic review of current cybersecurity training methods,” Computers & Security, vol. 133, p. 103220, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Ribeiro et al., “Which factors predict susceptibility to phishing? An empirical study,” Computers & Security, vol. 132, p. 103201, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Riasat, M. Shah, and M. S. Gonul, “Strengthening cybersecurity resilience: Adoption of emerging security tools in mobile banking apps,” Computers, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 129, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Ifinedo and J. Beachboard, “Integrating Protection Motivation and Planned Behavior theories for cybersecurity compliance,” Computers & Security, vol. 120, p. 103021, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. U. Hasan et al., “A review on secure authentication mechanisms for mobile security,” Sensors, vol. 25, no. 3, p. 700, 2025. [CrossRef]

- World Bank, “Global Findex Insights: Digital Adoption in Low-Income Economies,” 2024. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex.

- African Union, “AU Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection (Malabo Convention),” AU, 2014. Available: https://au.int/en/treaties/african-union-convention-cyber-security-and-personal-data-protection.

- N. Kshetri, “Cybersecurity challenges in developing economies: A contemporary analysis,” Telecommunications Policy, vol. 47, no. 2, p. 102417, 2023.

- P. T. Tran-Truong et al., “A systematic review of multi-factor authentication in digital payment systems,” Information and Software Technology, vol. 161, p. 107184, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Akgün and R. Samet, “Behavioral factors influencing 2FA adoption,” Computers, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 312, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Parsons et al., “Predicting security behaviors: A meta-analysis of human factors in cybersecurity,” Computers & Security, vol. 118, p. 102734, 2022.

- L. Tam and M. Glassman, “Password behaviors and security fatigue: A global analysis,” Journal of Cybersecurity, vol. 8, no. 1, p. tyab017, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Baki, S. Shaikh, and S. Jøsang, “Sixteen years of phishing user studies: What have we learned?,” Computers & Security, vol. 100, p. 102082, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal et al., “Association between stress and information security policy non-compliance: A meta-analysis,” Computers & Security, vol. 122, p. 103081, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhana, J. Ophoff, and K. Johnston, “Security fatigue: A case study of data specialists,” Information & Computer Security, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 502–520, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Matthews et al., “Impacts of security fatigue, age, and individual differences on password tools,” Proceedings of HFES, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 160–170, 2024. [CrossRef]

- IMF, “Digital Finance and Security in Frontier Markets: Trends and Risks,” 2023. Available: https://www.imf.org.

- GSMA, “Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa 2024: Digital Inclusion and Cybersecurity,” 2024. Available: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/sub-saharan-africa.

- M. Tsohou, et al., “Cybersecurity awareness in developing countries: A review of challenges and strategies,” Information Systems Frontiers, vol. 25, pp. 1501–1518, 2023.

- Dinev and P. Hart, “Internet privacy concerns and beliefs about government surveillance: An empirical analysis,” Journal of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 29, pp. 101–118, 2020.

- Y. Alotaibi and F. Alqahtani, “Factors affecting cybersecurity behavior: An integrated model of knowledge, attitude, and perception,” Computers & Security, vol. 119, p. 102745, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Smith et al., “The role of human factors in information security compliance: Evidence from emerging economies,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 143, p. 107648, 2023.

- Dissertation Data Analysis Help, “Cochran’s Sample Size Calculator.” [Online]. Available: https://dissertationdataanalysishelp.com/cochrans-sample-size-calculator/. [Accessed: Aug. 31, 2025].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).