Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introductionh

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. W-PINN

2.2. Stage 1 Modeling Method

2.3. Stage 2 Model Development Modeling Methods

2.4. Three Input Models

2.5. Forecast Structures

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cryer, P.E. Hypoglycemia, Functional Brain Failure, and Brain Death. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 868–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, C.M.; Skinner, A.; Bayles, J.; Chen, Y.S.; Daphna-Iken, D.; Fisher, S.J. Severe Hypoglycemia-Induced Sudden Death Is Mediated by Both Cardiac Arrhythmias and Seizures. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2018, 315, E240–E249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guemes, A.; Cappon, G.; Hernandez, B.; Reddy, M.; Oliver, N.; Georgiou, P.; Herrero, P. Predicting Quality of Overnight Glycaemic Control in Type 1 Diabetes Using Binary Classifiers. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2020, 24, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kosmas, P. Integrating Bayesian Approaches and Expert Knowledge for Forecasting Continuous Glucose Monitoring Values in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2025, 29, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, A.; Moreno-Fernández, J.; Fernández-García, D.; Solá, E. The Hybrid Closed-Loop System Tandem t:Slim X2TM with Control-IQ Technology: Expert Recommendations for Better Management and Optimization. Diabetes Ther 2024, 15, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devore, J. Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences, 9th edition; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-305-25180-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, S.L.; Frystyk, J.; Hejlesen, O.K.; Tarnow, L.; Fleischer, J. A Novel Algorithm for Prediction and Detection of Hypoglycemia Based on Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Heart Rate Variability in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014, 8, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalraj, R.; Neelakandan, S.; Ranjith Kumar, M.; Chandra Shekhar Rao, V.; Anand, R.; Singh, H. Interpretable Filter Based Convolutional Neural Network (IF-CNN) for Glucose Prediction and Classification Using PD-SS Algorithm. Measurement 2021, 183, 109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren-Oruklu, M.; Cinar, A.; Quinn, L. Hypoglycemia Prediction with Subject-Specific Recursive Time-Series Models. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren-Oruklu, M.; Cinar, A.; Quinn, L.; Smith, D. Estimation of Future Glucose Concentrations with Subject-Specific Recursive Linear Models. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 2009, 11, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turksoy, K.; Bayrak, E.S.; Quinn, L.; Littlejohn, E.; Cinar, A. Guaranteed Stability of Recursive Multi-Input-Single-Output Time Series Models. In Proceedings of the 2013 American Control Conference; June 2013; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bequette, B.W. Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Real-Time Algorithms for Calibration, Filtering, and Alarms. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkogianni, K.; Mitsis, K.; Arredondo, M.-T.; Fico, G.; Fioravanti, A.; Nikita, K.S. Neuro-Fuzzy Based Glucose Prediction Model for Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. In Proceedings of the IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI); June 2014; pp. 252–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, S.M.A.; Chandola, V.; Ibrahim, M.; Romanski, B.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Singh, T. Multi-Step Ahead Predictive Model for Blood Glucose Concentrations of Type-1 Diabetic Patients. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 24332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turksoy, K.; Quinn, L.T.; Littlejohn, E.; Cinar, A. Artificial Pancreas Systems: An Integrated Multivariable Adaptive Approach. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2014, 47, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren-Oruklu, M.; Cinar, A.; Colmekci, C.; Camurdan, M.C. Self-Tuning Controller for Regulation of Glucose Levels in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. In Proceedings of the 2008 American Control Conference; June 2008; pp. 819–824. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, F.; Wilson, D.M.; Buckingham, B.A.; Arzumanyan, H.; Clinton, P.; Chase, H.P.; Lum, J.; Maahs, D.M.; Calhoun, P.M.; Bequette, B.W. Inpatient Studies of a Kalman-Filter-Based Predictive Pump Shutoff Algorithm. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012, 6, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanthi, S.; Kumar, D.; Varatharaj, S.; Santhana, S. Prediction of Hypo/Hyperglycemia through System Identification, Modeling and Regularization of Ill-Posed Data. International Journal of Computer Science & Emerging Technologies.

- Eren-Oruklu, M.; Cinar, A.; Quinn, L.; Smith, D. Blood Glucose Regulation with An Adaptive Model-Based Control Algorithm. In Proceedings of the ResearchGate; November 2008.

- Professors, Department of ECE, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India; Shanthi*, Dr.S.; Bharath, Dr.S.; Professors, Department of ECE, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India; Sujatha, Dr.M.; Professors, Department of ECE, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India Data Based Estimation of Near Future Values of Blood Glucose with K-Nearest Neighborhood Algorithm. IJITEE 2019, 8, 1438–1442. [CrossRef]

- Kafali, O.; Schaechtle, U.; Stathis, K. Hydra: A Hybrid Diagnosis and Monitoring Architecture for Diabetes. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 16th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom); IEEE: Natal, October, 2014; pp. 531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.S.; Patek, S.D.; Breton, M.D.; Kovatchev, B.P. Hypoglycemia Prevention via Pump Attenuation and Red-Yellow-Green “Traffic” Lights Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Insulin Pump Data. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassau, E.; Cameron, F.; Lee, H.; Bequette, B.W.; Zisser, H.; Jovanovič, L.; Chase, H.P.; Wilson, D.M.; Buckingham, B.A.; Doyle, F.J. Real-Time Hypoglycemia Prediction Suite Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, R.; Nagaraj, H.C. Multivariate Long-Term Forecasting of T1DM: A Hybrid Econometric Model-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the Emerging Research in Computing, Information, Communication and Applications; Shetty, N.R., Patnaik, L.M., Prasad, N.H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1013–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, F.; Johansson, R.; Olsson, M.L. Predicting Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Using a Non-Parametric Insulin Action Model. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 2015; 1583–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Del Favero, S.; Facchinetti, A.; Cobelli, C. A Glucose-Specific Metric to Assess Predictors and Identify Models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 59, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, B.S.; Alanis, A.Y.; Sanchez, E.N.; Ornelas-Tellez, F.; Ruiz-Velazquez, E. Inverse Optimal Neural Control of Blood Glucose Level for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Journal of the Franklin Institute 2012, 349, 1851–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, P.; Doyle, F.J.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. Multi-Objective Blood Glucose Control for Type 1 Diabetes. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing 2009, 47, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewings, S.M.; Sahu, S.K.; Valletta, J.J.; Byrne, C.D.; Chipperfield, A.J. A Bayesian Network for Modelling Blood Glucose Concentration and Exercise in Type 1 Diabetes. Stat Methods Med Res 2015, 24, 342–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, M.; Davari Benam, K.; Khoshamadi, H.; Fougner, A. Blood Glucose Level Prediction Using Subcutaneous Sensors for in Vivo Study: Compensation for Measurement Method Slow Dynamics Using Kalman Filter Approach.; December 6 2022; pp. 6034–6039.

- Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Molenaar, P.; Ulbrecht, J.S. Model Predictive Control for Type 1 Diabetes Based on Personalized Linear Time-Varying Subject Model Consisting of Both Insulin and Meal Inputs: An in Silico Evaluation. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015, 9, 941–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Min, X.; Zou, D.; Xu, K. Mathematical Modeling on Experimental Protocol of Glucose Adjustment for Non-Invasive Blood Glucose Sensing. In Proceedings of the Dynamics and Fluctuations in Biomedical Photonics IX, SPIE, February 9 2012; 8222, pp. 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wilinska, M.E.; Chassin, L.J.; Acerini, C.L.; Allen, J.M.; Dunger, D.B.; Hovorka, R. Simulation Environment to Evaluate Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery Systems in Type 1 Diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, J.; Prendin, F.; Meneghetti, L.; Cappon, G.; Sparacino, G.; Facchinetti, A.; Favero, S.D. Personalized Machine Learning Algorithm Based on Shallow Network and Error Imputation Module for an Improved Blood Glucose Prediction.; 2020.

- Palerm, C.C.; Willis, J.P.; Desemone, J.; Bequette, B.W. Hypoglycemia Prediction and Detection Using Optimal Estimation. Diabetes Technol Ther 2005, 7, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, F.; Nossai, Z.; Gomma, H.; Ibrahim, I.; Abdelsalam, M. A Recurrent Neural Network Approach for Predicting Glucose Concentration in Type-1 Diabetic Patients.; Springer, September 15 2011; Vol. AICT-363, p. 254.

- Allam, F.; Nossair, Z.; Gomma, H.; Ibrahim, I.; Abd-el Salam, M. Prediction of Subcutaneous Glucose Concentration for Type-1 Diabetic Patients Using a Feed Forward Neural Network. In Proceedings of the The 2011 International Conference on Computer Engineering & Systems, November 2011; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Elleri, D.; Allen, J.M.; Nodale, M.; Wilinska, M.E.; Acerini, C.L.; Dunger, D.B.; Hovorka, R. Suspended Insulin Infusion during Overnight Closed-Loop Glucose Control in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 2010, 27, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljil, K.S.; Qadah, G.; Pasquier, M. Predicting Hypoglycemia in Diabetic Patients Using Time-Sensitive Artificial Neural Networks. International Journal of Healthcare Information Systems and Informatics 2016, 11, NA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Turksoy, K.; Cinar, A. Performance Assessment of Model-Based Artificial Pancreas Control Systems. In Prediction Methods for Blood Glucose Concentration: Design, Use and Evaluation; Kirchsteiger, H., Jørgensen, J.B., Renard, E., del Re, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-25913-0. [Google Scholar]

- Georga, E.I.; Protopappas, V.C.; Polyzos, D.; Fotiadis, D.I. Predictive Modeling of Glucose Metabolism Using Free-Living Data of Type 1 Diabetic Patients. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology, August 2010; pp. 589–592. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M.E.; Hripcsak, G.; Mamykina, L.; Stuart, A.; Albers, D.J. Offline and Online Data Assimilation for Real-Time Blood Glucose Forecasting in Type 2 Diabetes. arXiv Quantitative Methods 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl, F.; Johansson, R. Diabetes Mellitus Modeling and Short-Term Prediction Based on Blood Glucose Measurements. Mathematical Biosciences 2009, 217, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percival, M.W.; Wang, Y.; Grosman, B.; Dassau, E.; Zisser, H.; Jovanovič, L.; Doyle, F.J. Development of a Multi-Parametric Model Predictive Control Algorithm for Insulin Delivery in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Clinical Parameters. Journal of Process Control 2011, 21, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, D.K.; Kotz, K.; Stiehl, C. Non-Invasive Glucose Monitoring from Measured Inputs. In Proceedings of the UKACC International Conference on Control 2010, September 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Beverlin, L.; Rollins, D.K.; Rollins, D.; Vyas, N.; Andre, D. An Algorithm for Optimally Fitting a Wiener Model. 2011.

- Rollins, D.K.; Bhandari, N.; Kleinedler, J.; Kotz, K.; Strohbehn, A.; Boland, L.; Murphy, M.; Andre, D.; Vyas, N.; Welk, G.; et al. Free-Living Inferential Modeling of Blood Glucose Level Using Only Noninvasive Inputs. Journal of Process Control 2010, 20, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaloli, M.; Cescon, M. Long-Term Prediction of Blood Glucose Levels in Type 1 Diabetes Using a CNN-LSTM-Based Deep Neural Network. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2023, 17, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annuzzi, G.; Apicella, A.; Arpaia, P.; Bozzetto, L.; Criscuolo, S.; De Benedetto, E.; Pesola, M.; Prevete, R. Exploring Nutritional Influence on Blood Glucose Forecasting for Type 1 Diabetes Using Explainable AI. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024, 28, 3123–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, G.P.P.; Batra, R.; Ramprasad, R.; Mishin, Y. Physically Informed Artificial Neural Networks for Atomistic Modeling of Materials. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Cao, X.; Liu, B.; Gao, M. Solving Partial Differential Equations Using Deep Learning and Physical Constraints. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.K.; Pottmann, M. Gray-Box Identification of Block-Oriented Nonlinear Models. Journal of Process Control 2000, 10, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, K.; Cinar, A.; Mei, Y.; Roggendorf, A.; Littlejohn, E.; Quinn, L.; Rollins, D.K.Sr. Multiple-Input Subject-Specific Modeling of Plasma Glucose Concentration for Feedforward Control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 18216–18225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, D.; Goeddel, C.E.; Matthews, S.L.; Mei, Y.; Roggendorf, A.; Littlejohn, E.; Quinn, L.; Cinar, A. An Extended Static and Dynamic Feedback–Feedforward Control Algorithm for Insulin Delivery in the Control of Blood Glucose Level. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 6734–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seborg, D.E.; Edgar, T.F.; Mellichamp, D.A. Process Dynamics and Control, 2nd edition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2003; ISBN 978-0-471-00077-8. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Corripio, A.B. Principles and Practices of Automatic Process Control, 3rd edition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2005; ISBN 978-0-471-43190-9. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, C.A.R.; Rodrigues, C.P. The Lag Length of a Dynamic Regression Model: A Comparative Study. AIP Conference Proceedings 2008, 1073, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasanayake, I.S.; Seborg, D.E.; Pinsker, J.E.; Doyle, F.J.; Dassau, E. Empirical Dynamic Model Identification for Blood-Glucose Dynamics in Response to Physical Activity. Proc IEEE Conf Decis Control 2015, 2015, 3834–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brange, J.; Vølund, A. Insulin Analogs with Improved Pharmacokinetic Profiles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1999, 35, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, M.; Zou, H.; Zhang, L. Predicting Blood Glucose Dynamics with Multi-Time-Series Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, November 6 2017; pp. 1–2.

- Rollins, D. Continuous-Time Hammerstein Nonlinear Modeling Applied to Distillation. AIChE Journal 2004. [Google Scholar]

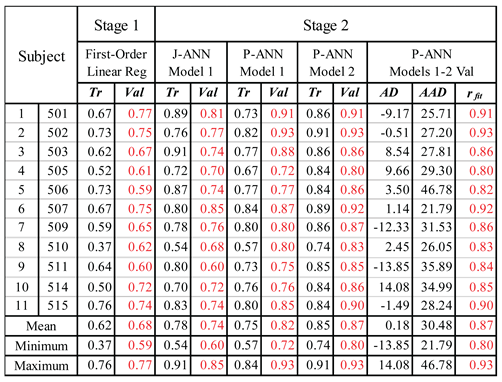

|

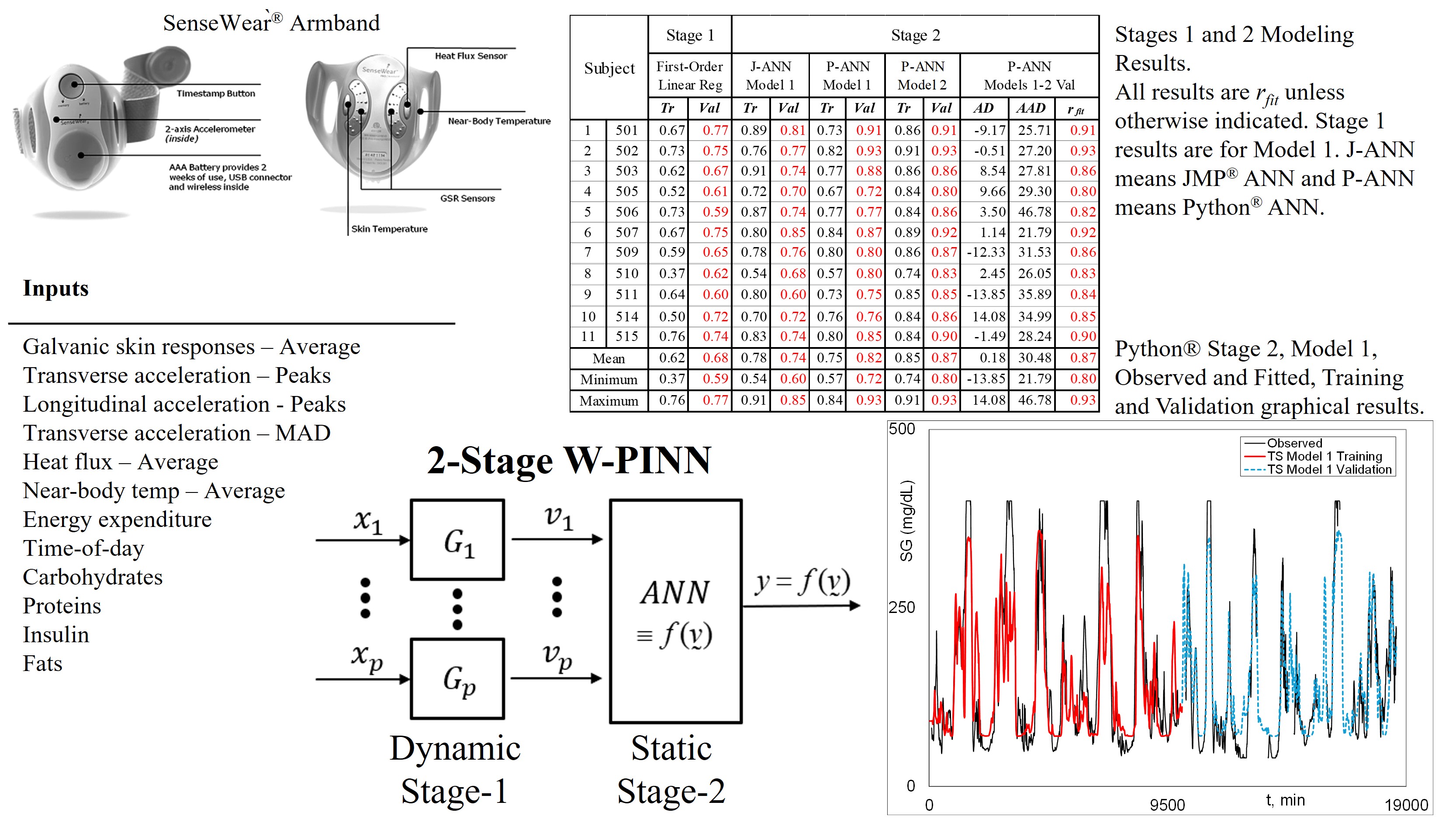

| 1 All results are rfit unless otherwise indicated. Stage 1 results are for Model 1. J-ANN means JMP® ANN and P-ANN means Python® ANN. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).